Renaissance humanist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of

Renaissance Humanism – World History Encyclopedia

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p003k9ct Paganism in the Renaissance BBC Radio 4 discussion with Tom Healy, Charles Hope & Evelyn Welch (''In Our Time'', June 16, 2005) {{Middle Ages Medieval philosophy Philosophical movements

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teachers and students of the humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

, known as the , which included grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structure, structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clause (linguistics), clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraint ...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

, history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

, poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings ...

, and moral philosophy

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ...

. It was not until the 19th century that this began to be called ''humanism'' instead of the original ''humanities'', and later by the retronym

A retronym is a newer name for an existing thing that helps differentiate the original form/version from a more recent one. It is thus a word or phrase created to avoid confusion between older and newer types, whereas previously (before there were ...

''Renaissance humanism'' to distinguish it from later humanist developments. During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

period most humanists were Christians, so their concern was to "purify and renew Christianity", not to do away with it. Their vision was to return ''ad fontes

''Ad fontes'' is a Latin expression which means " ackto the sources" (lit. "to the sources"). The phrase epitomizes the renewed study of Greek and Latin classics in Renaissance humanism. Similarly, the Protestant Reformation called for renewed a ...

'' ("to the sources") to the simplicity of the New Testament, bypassing the complexities of medieval theology.

Under the influence and inspiration of the classics, humanists developed a new rhetoric and new learning. Some scholars also argue that humanism articulated new moral and civic perspectives and values offering guidance in life.

Renaissance humanism was a response to what came to be depicted by later whig historians as the "narrow pedantry" associated with medieval scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translat ...

. Humanists sought to create a citizenry

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

able to speak and write with eloquence and clarity and thus capable of engaging in the civic life of their communities and persuading others to virtuous and prudent actions.

Humanism, while set up by a small elite who had access to books and education, was intended as a cultural mode to influence all of society. It was a program to revive the cultural legacy, literary legacy, and moral philosophy of classical antiquity.

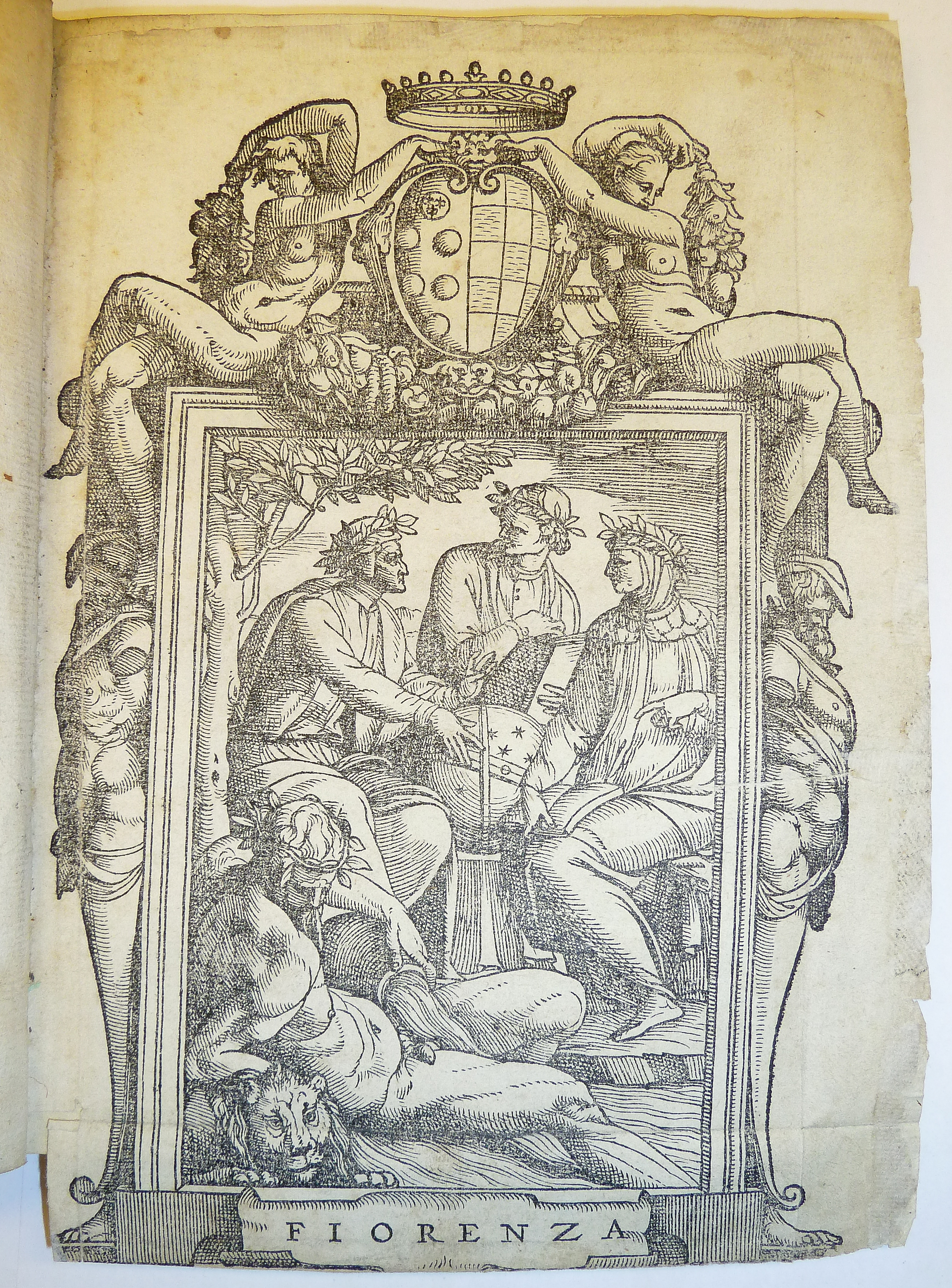

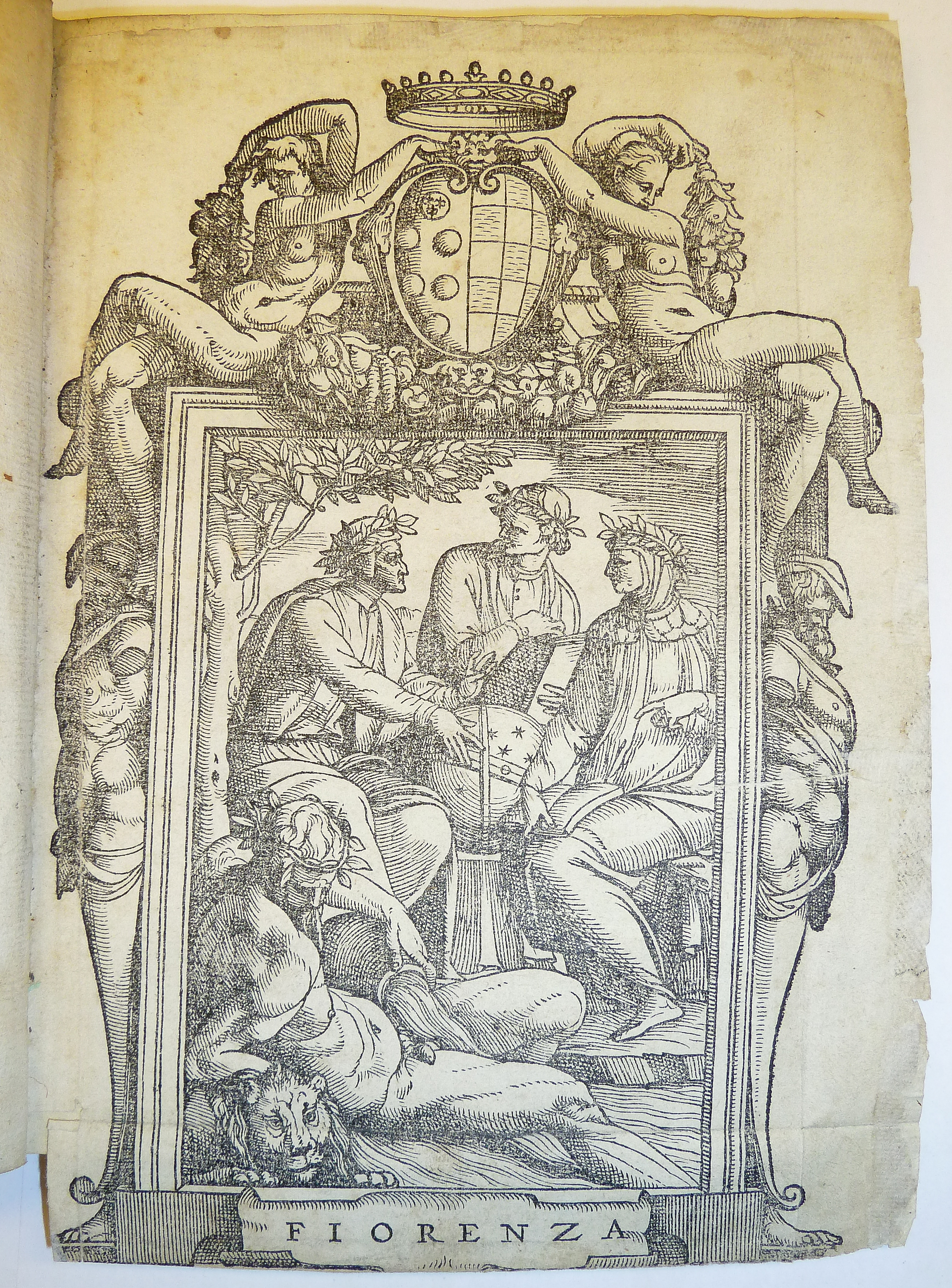

There were important centres of humanism in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of t ...

, Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

, Ferrara

Ferrara (, ; egl, Fràra ) is a city and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital of the Province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream ...

, and Urbino

Urbino ( ; ; Romagnol: ''Urbìn'') is a walled city in the Marche region of Italy, south-west of Pesaro, a World Heritage Site notable for a remarkable historical legacy of independent Renaissance culture, especially under the patronage of ...

.

Definition

Very broadly, the project of the Italian Renaissance humanists of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was the ''studia humanitatis'': the study of thehumanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

. This project sought to recover the culture of ancient Greece and Rome through its literature and philosophy and to use this classical revival to imbue the ruling classes with the moral attitudes of said ancients—a project James Hankins calls one of "virtue politics".Hankins, James (2019). ''Virtue Politics: Soulcraft and Statecraft in Renaissance Italy.'' The Belknap Press of Harvard University. But what this ''studia humanitatis'' actually constituted is a subject of much debate. According to one scholar of the movement,

Early Italian humanism, which in many respects continued the grammatical and rhetorical traditions of the Middle Ages, not merely provided the oldHowever, in investigating this definition in his article "The changing concept of the ''studia humanitatis'' in the early Renaissance," Benjamin G. Kohl provides an account of the various meanings the term took on over the course of the period. Around the middle of the fourteenth century, when the term first came into use among Italian ''Trivium The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric. The trivium is implicit in ''De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii'' ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but t ...with a new and more ambitious name (''Studia humanitatis''), but also increased its actual scope, content and significance in the curriculum of the schools and universities and in its own extensive literary production. The ''studia humanitatis'' excluded logic, but they added to the traditional grammar and rhetoric not only history,Greek Greek may refer to: Greece Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe: *Greeks, an ethnic group. *Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family. **Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ..., and moral philosophy, but also made poetry, once a sequel of grammar and rhetoric, the most important member of the whole group.

literati

Literati may refer to:

*Intellectuals or those who love, read, and comment on literature

*The scholar-official or ''literati'' of imperial/medieval China

**Literati painting, also known as the southern school of painting, developed by Chinese liter ...

'', it was used in reference to a very specific text: as praise of the cultural and moral attitudes expressed in Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

’s ''Pro Archia poeta'' (62 BCE). Tuscan humanist Coluccio Salutati popularized the term in the 1370s, using the phrase to refer to culture and learning as a guide to moral life, with a focus on rhetoric and oration. Over the years, he came to use it specifically in literary praise of his contemporaries, but later viewed the ''studia humanitatis'' as a means of editing and restoring ancient texts and even understanding scripture and other divine literature. But it was not until the beginning of the quattrocento

The cultural and artistic events of Italy during the period 1400 to 1499 are collectively referred to as the Quattrocento (, , ) from the Italian word for the number 400, in turn from , which is Italian for the year 1400. The Quattrocento encom ...

(fifteenth century) that the ''studia humanitatis'' began to be associated with particular academic disciplines, when Pier Paolo Vergerio, in his ''De ingenuis moribus'', stressed the importance of rhetoric, history, and moral philosophy as a means of moral improvement. By the middle of the century, the term was adopted more formally, as it started to be used in Bologna and Padua in reference to university courses that taught these disciplines as well as Latin poetry, before then spreading northward throughout Italy. But the first instance of it as encompassing grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy all together only came when Tommaso Parentucelli

Pope Nicholas V ( la, Nicholaus V; it, Niccolò V; 13 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene made ...

wrote to Cosimo de’ Medici

Cosimo di Giovanni de' Medici (27 September 1389 – 1 August 1464) was an Italian banker and politician who established the Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derived from his wealth ...

with recommendations regarding his library collection, saying, ''"de studiis autem humanitatis quantum ad grammaticam, rhetoricam, historicam et poeticam spectat ac moralem"'' ("one sees of the study of humanity he humanitiesthat it is so much in grammar, rhetoric, history and poetry, and also in ethics"). And so, the term ''studia humanitatis'' took on a variety of meanings over the centuries, being used differently by humanists across the various Italian city-states as one definition got adopted and spread across the country. Still, it has referred consistently to a mode of learning—formal or not—that results in one's moral edification.

Origin

In the last years of the 13th century and in the first decades of the 14th century, the cultural climate was changing in some European regions. The rediscovery, study, and renewed interest in authors who had been forgotten, and in the classical world that they represented, inspired a flourishing return to linguistic, stylistic and literary models of antiquity. There emerged a consciousness of the need for a cultural renewal, which sometimes also meant a detachment from contemporary culture. Manuscripts and inscriptions were in high demand and graphic models were also imitated. This “return to the ancients” was the main component of so-called “pre-humanism”, which developed particularly inTuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

, in the Veneto

it, Veneto (man) it, Veneta (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 = ...

region, and at the papal court of Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune ha ...

, through the activity of figures such as Lovato Lovati and Albertino Mussato in Padua, Landolfo Colonna in Avignon, Ferreto de' Ferreti in Vicenza, Convenevole from Prato in Tuscany and then in Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune ha ...

, and many others.

By the 14th century some of the first humanists were great collectors of antique manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced ...

s, including Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credite ...

, Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was som ...

, Coluccio Salutati, and Poggio Bracciolini

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini (11 February 1380 – 30 October 1459), usually referred to simply as Poggio Bracciolini, was an Italian scholar and an early Renaissance humanist. He was responsible for rediscovering and recovering many class ...

. Of the four, Petrarch was dubbed the "Father of Humanism," as he was the one who first encouraged the study of pagan civilizations and the teaching of classical virtues as a means of preserving Christianity. He also had a very impressive library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

, of which many manuscripts did not survive. Many worked for the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and were in holy orders, like Petrarch, while others were lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solici ...

s and chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

s of Italian cities, and thus had access to book copying workshops, such as Petrarch's disciple Salutati, the Chancellor of Florence

The Chancellor of Florence held the most important position in the bureaucracy of the Florentine Republic. Though the chancellor was not officially a member of the Republic's elected political government, unlike the gonfaloniere or the nine member ...

.

In Italy, the humanist educational program won rapid acceptance and, by the mid-15th century, many of the upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is ...

es had received humanist educations, possibly in addition to traditional scholastic

Scholastic may refer to:

* a philosopher or theologian in the tradition of scholasticism

* ''Scholastic'' (Notre Dame publication)

* Scholastic Corporation, an American publishing company of educational materials

* Scholastic Building, in New Y ...

ones. Some of the highest officials of the Catholic Church were humanists with the resources to amass important libraries. Such was Cardinal Basilios Bessarion

Bessarion ( el, Βησσαρίων; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the so-called great revival of letter ...

, a convert to the Catholic Church from Greek Orthodoxy

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

, who was considered for the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, and was one of the most learned scholars of his time. There were several 15th-century and early 16th-century humanist Popes one of whom, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II), was a prolific author and wrote a treatise on ''The Education of Boys''. These subjects came to be known as the humanities, and the movement which they inspired is shown as humanism.

The migration waves of Byzantine Greek scholars and émigrés in the period following the Crusader sacking of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

in 1453 was a very welcome addition to the Latin texts scholars like Petrarch had found in monastic libraries for the revival of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

literature and science via their greater familiarity with ancient Greek works. They included Gemistus Pletho

Georgios Gemistos Plethon ( el, Γεώργιος Γεμιστός Πλήθων; la, Georgius Gemistus Pletho /1360 – 1452/1454), commonly known as Gemistos Plethon, was a Greek scholar and one of the most renowned philosophers of the late Byz ...

, George of Trebizond

George of Trebizond ( el, Γεώργιος Τραπεζούντιος; 1395–1486) was a Byzantine Greek philosopher, scholar, and humanist. Life

He was born on the Greek island of Crete (then a Venetian colony known as the Kingdom of Candia), ...

, Theodorus Gaza

Theodorus Gaza ( el, Θεόδωρος Γαζῆς, ''Theodoros Gazis''; it, Teodoro Gaza; la, Theodorus Gazes), also called Theodore Gazis or by the epithet Thessalonicensis (in Latin) and Thessalonikeus (in Greek) (c. 1398 – c. 1475), wa ...

, and John Argyropoulos

John Argyropoulos (/ˈd͡ʒɑn ˌɑɹd͡ʒɪˈɹɑ.pə.ləs/ el, Ἰωάννης Ἀργυρόπουλος ''Ioannis Argyropoulos''; it, Giovanni Argiropulo; surname also spelt ''Argyropulus'', or ''Argyropulos'', or ''Argyropulo''; c. 1415 – 2 ...

.

The Italian humanism spread northward to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

, the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, Poland-Lithuania, Hungary and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

with the adoption of large-scale printing after 1500, and it became associated with the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

. In France, pre-eminent humanist Guillaume Budé (1467–1540) applied the philological

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

methods of Italian humanism to the study of antique coin

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in orde ...

age and to legal history

Legal history or the history of law is the study of how law has Sociocultural evolution, evolved and why it has changed. Legal history is closely connected to the development of civilisations and operates in the wider context of social history. C ...

, composing a detailed commentary on Justinian's Code

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

. Budé was a royal absolutist (and not a republican like the early Italian ''umanisti'') who was active in civic life, serving as a diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

for François I and helping to found the Collège des Lecteurs Royaux (later the Collège de France). Meanwhile, Marguerite de Navarre, the sister of François I, was a poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems ( oral or wr ...

, novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living wage, living writing novels and other fiction, while othe ...

, and religious mystic

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

who gathered around her and protected a circle of vernacular poets and writers, including Clément Marot

Clément Marot (23 November 1496 – 12 September 1544) was a French Renaissance poet.

Biography

Youth

Marot was born at Cahors, the capital of the province of Quercy, some time during the winter of 1496–1497. His father, Jean Marot (c ...

, Pierre de Ronsard

Pierre de Ronsard (; 11 September 1524 – 27 December 1585) was a French poet or, as his own generation in France called him, a " prince of poets".

Early life

Pierre de Ronsard was born at the Manoir de la Possonnière, in the village of ...

, and François Rabelais.

Paganism and Christianity in the Renaissance

Many humanists were churchmen, most notably Pope Pius II, Sixtus IV, andLeo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3& ...

, and there was often patronage of humanists by senior church figures. Much humanist effort went into improving the understanding and translations of Biblical and early Christian texts, both before and after the Reformation, which was greatly influenced by the work of non-Italian, Northern European figures such as Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

, Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples

Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples ( Latinized as Jacobus Faber Stapulensis; c. 1455 – c. 1536) was a French theologian and a leading figure in French humanism. He was a precursor of the Protestant movement in France. The "d'Étaples" was not part ...

, William Grocyn, and Swedish Catholic Archbishop in exile Olaus Magnus

Olaus Magnus (October 1490 – 1 August 1557) was a Swedish writer, cartographer, and Catholic ecclesiastic.

Biography

Olaus Magnus (a Latin translation of his birth name Olof Månsson) was born in Linköping in October 1490. Like his elder b ...

.

Description

''The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy'' describes therationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

of ancient writings as having tremendous impact on Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

scholars:

In 1417, for example, Poggio Bracciolini

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini (11 February 1380 – 30 October 1459), usually referred to simply as Poggio Bracciolini, was an Italian scholar and an early Renaissance humanist. He was responsible for rediscovering and recovering many class ...

discovered the manuscript of Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem '' De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated in ...

, '' De rerum natura'', which had been lost for centuries and which contained an explanation of Epicurean doctrine, though at the time this was not commented on much by Renaissance scholars, who confined themselves to remarks about Lucretius's grammar and syntax.

Only in 1564 did French commentator Denys Lambin (1519–72) announce in the preface to the work that "he regarded Lucretius's Epicurean ideas as 'fanciful, absurd, and opposed to Christianity'." Lambin's preface remained standard until the nineteenth century. Epicurus's unacceptable doctrine that pleasure was the highest good "ensured the unpopularity of his philosophy". Lorenzo Valla

Lorenzo Valla (; also Latinized as Laurentius; 14071 August 1457) was an Italian Renaissance humanist, rhetorician, educator, scholar, and Catholic priest. He is best known for his historical-critical textual analysis that proved that the '' ...

, however, puts a defense of epicureanism in the mouth of one of the interlocutors of one of his dialogues.

Epicureanism

Charles Trinkhaus regards Valla's "epicureanism" as a ploy, not seriously meant by Valla, but designed to refute Stoicism, which he regarded together with epicureanism as equally inferior to Christianity. Valla's defense, or adaptation, of Epicureanism was later taken up in ''The Epicurean'' byErasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

, the "Prince of humanists:"

This passage exemplifies the way in which the humanists saw pagan classical works, such as the philosophy of Epicurus, as being in harmony with their interpretation of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

.

Neo-Platonism

Renaissance Neo-Platonists such asMarsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver ...

(whose translations of Plato's works into Latin were still used into the 19th century) attempted to reconcile Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at ...

with Christianity, according to the suggestions of early Church Fathers Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son ...

and Saint Augustine. In this spirit, Pico della Mirandola attempted to construct a syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

of religions and philosophies with Christianity, but his work did not win favor with the church authorities, who rejected it because of his views on magic.

Evolution and reception

Widespread view

Historian Steven Kreis expresses a widespread view (derived from the 19th-century Swiss historianJacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. He is known as one of the major progenitors of cultural history. Sigfri ...

), when he writes that: The period from the fourteenth century to the seventeenth worked in favor of the general emancipation of the individual. The city-states of northern Italy had come into contact with the diverse customs of the East, and gradually permitted expression in matters of taste and dress. The writings of Dante, and particularly the doctrines of Petrarch and humanists like Machiavelli, emphasized the virtues of intellectual freedom and individual expression. In the essays of Montaigne the individualistic view of life received perhaps the most persuasive and eloquent statement in the history of literature and philosophy.Two noteworthy trends in Renaissance humanism were Renaissance Neo-Platonism and

Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

, which through the works of figures like Nicholas of Kues, Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno (; ; la, Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist. He is known for his cosmolo ...

, Cornelius Agrippa, Campanella and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (24 February 1463 – 17 November 1494) was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, he proposed to defend 900 theses on religion, philosophy, ...

sometimes came close to constituting a new religion itself. Of these two, Hermeticism has had great continuing influence in Western thought, while the former mostly dissipated as an intellectual trend, leading to movements in Western esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

such as Theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

and New Age

New Age is a range of spiritual or religious practices and beliefs which rapidly grew in Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise definition difficult. Although many scholars consi ...

thinking. The "Yates thesis" of Frances Yates

Dame Frances Amelia Yates (28 November 1899 – 29 September 1981) was an English historian of the Renaissance, who wrote books on esoteric history.

After attaining an MA in French at University College London, she began to publish her resear ...

holds that before falling out of favour, esoteric Renaissance thought introduced several concepts that were useful for the development of scientific method, though this remains a matter of controversy.

Sixteenth century and beyond

Though humanists continued to use their scholarship in the service of the church into the middle of the sixteenth century and beyond, the sharply confrontational religious atmosphere following the Reformation resulted in the Counter-Reformation that sought to silence challenges toCatholic theology

Catholic theology is the understanding of Catholic doctrine or teachings, and results from the studies of theologians. It is based on canonical scripture, and sacred tradition, as interpreted authoritatively by the magisterium of the Catholic ...

, with similar efforts among the Protestant denominations. However, a number of humanists joined the Reformation movement and took over leadership functions, for example, Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the L ...

, Ulrich Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

, Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Luther ...

, Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagr ...

, John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

, and William Tyndale

William Tyndale (; sometimes spelled ''Tynsdale'', ''Tindall'', ''Tindill'', ''Tyndall''; – ) was an English biblical scholar and linguist who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his executi ...

.

With the Counter-Reformation initiated by the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

(1545–1563), positions hardened and a strict Catholic orthodoxy based on scholastic philosophy was imposed. Some humanists, even moderate Catholics such as Erasmus, risked being declared heretics for their perceived criticism of the church. In 1514 he left for Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS) ...

and worked at the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis'', German: ''Universität Basel'') is a university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest surviving universitie ...

for several years.

The historian of the Renaissance Sir John Hale cautions against too direct a linkage between Renaissance humanism and modern uses of the term humanism: "Renaissance humanism must be kept free from any hint of either 'humanitarianism' or 'humanism' in its modern sense of rational, non-religious approach to life ... the word 'humanism' will mislead ... if it is seen in opposition to a Christianity its students in the main wished to supplement, not contradict, through their patient excavation of the sources of ancient God-inspired wisdom."

Historiography

The Baron Thesis

Hans Baron (1900-1988) was the inventor of the now ubiquitous term "civic humanism." First coined in the 1920s and based largely on his studies of Leonardo Bruni, Baron's "thesis" proposed the existence of a central strain of humanism, particularly in Florence and Venice, dedicated to republicanism. As argued in his '' chef-d'œuvre'', ''The Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance: Civic Humanism and Republican Liberty in an Age of Classicism and Tyranny'', the German historian thought that civic humanism originated in around 1402, after the great struggles between Florence and Visconti-led Milan in the 1390s. He considered Petrarch's humanism to be a rhetorical, superficial project, and viewed this new strand to be one that abandoned the feudal and supposedly "otherworldly" (i.e., divine) ideology of the Middle Ages in favour of putting the republican state and its freedom at the forefront of the "civic humanist" project. Already controversial at the time of ''The Crisis''Philip Jones Philip, Phillip, Phil or Phill Jones may refer to:

Sports

*Phil Jones (American football) (born 1946), American football coach

* Phil Jones (footballer, born 1961), English footballer who played for Sheffield United in the Football League

* Phil J ...

and Peter Herde found Baron's praise of "republican" humanists naive, arguing that republics were far less liberty-driven than Baron had believed, and were practically as undemocratic as monarchies. James Hankins adds that the disparity in political values between the humanists employed by oligarchies and those employed by princes was not particularly notable, as all of Baron's civic ideals were exemplified by humanists serving various types of government. In so arguing, he asserts that a "political reform program is central to the humanist movement founded by Petrarch. But it is not a 'republican' project in Baron's sense of republic; it is not an ideological product associated with a particular regime type."

Garin and Kristeller

Two renowned Renaissance scholars, Eugenio Garin and Paul Oskar Kristeller collaborated with one another throughout their careers. But while the two historians were on good terms, they fundamentally disagreed on the nature of Renaissance humanism. Kristeller affirmed that Renaissance humanism used to be viewed just as a project of Classical revival, one that led to great increase in Classical scholarship. But he argued that this theory "fails to explain the ideal of eloquence persistently set forth in the writings of the humanists," asserting that "their classical learning was incidental to" their being “professional rhetoricians." Similarly, he considered their influence on philosophy and particular figures' philosophical output to be incidental to their humanism, viewing grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and ethics to be the humanists' main concerns. Garin, on the other hand, viewed philosophy itself as being ever-evolving, each form of philosophy being inextricable from the practices of the thinkers of its period. He thus considered the Italian humanists' break from Scholasticism and newfound freedom to be perfectly in line with this broader sense of philosophy.Hankins, James. 2011. "Garin and Paul Oskar Kristeller: Existentialism, Neo-Kantianism, and the Post-war Interpretation of Renaissance Humanism." In ''Eugenio Garin: Dal Rinascimento all'Illuminismo'', ed. Michele Ciliberto, 481–505. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura. During the period in which they argued over these differing views, there was a broader cultural conversation happening regarding Humanism: one revolving aroundJean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialist, existentialism (and Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter ...

and Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centu ...

. In 1946, Sartre published a work called ''"L'existentialisme est un humanisme''," in which he outlined his conception of existentialism as revolving around the belief that "''existence'' comes before ''essence''"; that man "first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world – and defines himself afterwards," making himself and giving himself purpose. Heidegger, in a response to this work of Sartre's, declared: "For this is humanism: meditating and caring, that human beings be human and not inhumane, "inhuman", that is, outside their essence." He also discussed a decline in the concept of humanism, pronouncing that it had been dominated by metaphysics and essentially discounting it as philosophy. He also explicitly criticized Italian Renaissance humanism in the letter. While this discourse was taking place outside the realm of Renaissance Studies (for more on the evolution of the term “humanism,” see Humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

), this background debate was not irrelevant to Kristeller and Garin’s ongoing disagreement. Kristeller—who had at one point studied under Heidegger—also discounted (Renaissance) humanism as philosophy, and Garin’s ''Der italienische Humanismus'' was published alongside Heidegger's response to Sartre—a move that Rubini describes as an attempt "to stage a pre-emptive confrontation between historical humanism and philosophical neo-humanisms."Rubini, Rocco (2011). "The Last Italian Philosopher: Eugenio Garin (with an Appendix of Documents)." ''Intellectual History Review''. 21 (2): 209–230. DOI: 10.1080/17496977.2011.574348 Garin also conceived of the Renaissance humanists as occupying the same kind of "characteristic angst the existentialists attributed to men who had suddenly become conscious of their radical freedom," further weaving philosophy with Renaissance humanism.

Hankins summarizes the Kristeller v. Garin debate quite well, attesting to Kristeller's conception of professional philosophers as being very formal and method-focused. Renaissance humanists, on the other hand, he viewed to be professional rhetoricians who, using their classically-inspired ''paideia

''Paideia'' (also spelled ''paedeia'') ( /paɪˈdeɪə/; Greek: παιδεία, ''paideía'') referred to the rearing and education of the ideal member of the ancient Greek polis or state. These educational ideals later spread to the Greco-Rom ...

'' or ''institutio'', did improve fields such as philosophy, but without the practice of philosophy being their main goal or function. Garin, instead, wanted his “humanist-philosophers to be organic intellectuals,” not constituting a rigid school of thought, but having a shared outlook on life and education that broke with the medieval traditions that came before them.

Humanist

See also

*Renaissance humanism in Northern Europe

Renaissance humanism came much later to Germany and Northern Europe in general than to Italy, and when it did, it encountered some resistance from the scholastic theology which reigned at the universities.

Humanism may be dated from the inventi ...

* Christian humanism

* Greek scholars in the Renaissance

The migration waves of Byzantine Greek scholars and émigrés in the period following the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 is considered by many scholars key to the revival of Greek studies that led to the development of the Renaissance h ...

* Renaissance Latin

Renaissance Latin is a name given to the distinctive form of Literary Latin style developed during the European Renaissance of the fourteenth to fifteenth centuries, particularly by the Renaissance humanism movement.

Ad fontes

'' Ad fontes' ...

* Legal humanists

* New Learning

Notes

Further reading

* Bolgar, R. R. ''The Classical Heritage and Its Beneficiaries: from the Carolingian Age to the End of the Renaissance''. Cambridge, 1954. * Cassirer, Ernst. ''Individual and Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy''. Harper and Row, 1963. * Cassirer, Ernst (Editor), Paul Oskar Kristeller (Editor), John Herman Randall (Editor). ''The Renaissance Philosophy of Man''. University of Chicago Press, 1969. * Cassirer, Ernst. ''Platonic Renaissance in England''. Gordian, 1970. * Celenza, Christopher S. ''The Lost Italian Renaissance: Humanism, Historians, and Latin's Legacy''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2004 * Celenza, Christopher S. ''Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer''. London: Reaktion. 2017 * Celenza, Christopher S. ''The Intellectual World of the Italian Renaissance: Language, Philosophy, and the Search for Meaning''. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2018 * Erasmus, Desiderius. "The Epicurean". In ''Colloquies''. * Garin, Eugenio. ''Science and Civic Life in the Italian Renaissance''. New York: Doubleday, 1969. * Garin, Eugenio. ''Italian Humanism: Philosophy and Civic Life in the Renaissance.'' Basil Blackwell, 1965. * Garin, Eugenio. ''History of Italian Philosophy.'' (2 vols.) Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2008. *Grafton, Anthony

Anthony Thomas Grafton (born May 21, 1950) is an American historian of early modern Europe and the Henry Putnam University Professor of History at Princeton University, where he is also the Director the Program in European Cultural Studies. He i ...

. ''Bring Out Your Dead: The Past as Revelation''. Harvard University Press, 2004

* Grafton, Anthony. ''Worlds Made By Words: Scholarship and Community in the Modern West''. Harvard University Press, 2009

* Hale, John. ''A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance''. Oxford University Press, 1981, .

* Kallendorf, Craig W, editor. ''Humanist Educational Treatises''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The I Tatti Renaissance Library, 2002.

* Kraye, Jill (Editor). ''The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism''. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

* Kristeller, Paul Oskar. ''Renaissance Thought and Its Sources''. Columbia University Press, 1979

* Pico della Mirandola, Giovanni. ''Oration on the Dignity of Man''. In Cassirer, Kristeller, and Randall, eds. ''Renaissance Philosophy of Man''. University of Chicago Press, 1969.

* Skinner, Quentin. ''Renaissance Virtues: Visions of Politics: Volume II''. Cambridge University Press, 0022007.

* Makdisi, George. ''The Rise of Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West: With Special Reference to Scholasticism'', 1990: Edinburgh University Press

Edinburgh University Press is a scholarly publisher of academic books and journals, based in Edinburgh, Scotland.

History

Edinburgh University Press was founded in the 1940s and became a wholly owned subsidiary of the University of Edinburgh ...

* McGrath, Alister

Alister Edgar McGrath (; born 1953) is a Northern Irish theologian, Anglican priest, intellectual historian, scientist, Christian apologist, and public intellectual. He currently holds the Andreas Idreos Professorship in Science and Religion in ...

(2011). ''Christian Theology: An Introduction'', 5th edn. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

* McManus, Stuart M. "Byzantines in the Florentine Polis: Ideology, Statecraft and Ritual during the Council of Florence". '' Journal of the Oxford University History Society'', 6 (Michaelmas 2008/Hilary 2009).

*

* Nauert, Charles Garfield. ''Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe (New Approaches to European History).'' Cambridge University Press, 2006.

* Plumb, J. H. ed.: ''The Italian Renaissance'' 1961, American Heritage, New York, (page refs from 1978 UK Penguin edn).

* Rossellini, Roberto. ''The Age of the Medici'': Part 1, ''Cosimo de' Medici''; Part 2, ''Alberti'' 1973. (Film Series). Criterion Collection.

* Symonds, John Addington.''The Renaissance in Italy''. Seven Volumes. 1875–1886.

*

* Trinkaus, Charles. ''The Scope of Renaissance Humanism''. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1983.

* Wind, Edgar. ''Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance''. New York: W.W. Norton, 1969.

* Witt, Ronald. "In the footsteps of the ancients: the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni." Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2000

External links

Renaissance Humanism – World History Encyclopedia

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p003k9ct Paganism in the Renaissance BBC Radio 4 discussion with Tom Healy, Charles Hope & Evelyn Welch (''In Our Time'', June 16, 2005) {{Middle Ages Medieval philosophy Philosophical movements

Humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...