Regal Period on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Roman Kingdom, also known as the Roman monarchy and the regal period of ancient Rome, was the earliest period of

The site of the founding of the Roman Kingdom (and eventual

The site of the founding of the Roman Kingdom (and eventual

ImageSize = width:800 height:75

PlotArea = width:700 height:50 left:65 bottom:20

AlignBars = justify

Colors =

id:time value:rgb(0.7,0.7,1) #

id:period value:rgb(1,0.7,0.5) #

id:age value:rgb(0.95,0.85,0.5) #

id:era value:rgb(1,0.85,0.5) #

id:eon value:rgb(1,0.85,0.7) #

id:filler value:gray(0.8) # background bar

id:black value:black

Period = from:-753 till:-509

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:50 start:-753

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:5 start:-753

PlotData =

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:10 mark:(line,black) width:15 shift:(0,-5)

bar:Rulers color:era

from:-753 till:-716 text:

:::''Dates follow

Son of the

Son of the  Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as '' The Rape of the Sabine Women''. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighbouring tribes to a festival in Rome where the Romans committed a mass abduction of young women from among the attendees. The accounts vary from 30 to 683 women taken, a significant number for a population of 3,000 Latins (and presumably for the Sabines as well). War broke out when Romulus refused to return the captives. After the Sabines made three unsuccessful attempts to invade the hill settlements of Rome, the women themselves intervened during the Battle of the Lacus Curtius to end the war. The two peoples were united in a joint kingdom, with Romulus and the Sabine king

Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as '' The Rape of the Sabine Women''. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighbouring tribes to a festival in Rome where the Romans committed a mass abduction of young women from among the attendees. The accounts vary from 30 to 683 women taken, a significant number for a population of 3,000 Latins (and presumably for the Sabines as well). War broke out when Romulus refused to return the captives. After the Sabines made three unsuccessful attempts to invade the hill settlements of Rome, the women themselves intervened during the Battle of the Lacus Curtius to end the war. The two peoples were united in a joint kingdom, with Romulus and the Sabine king

After Romulus died, there was an

After Romulus died, there was an

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson,

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson,

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law

The seventh and final king of Rome was

The seventh and final king of Rome was

The legal status of Roman citizenship was limited and a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights, such as the right to trial and appeal, marry, vote, hold office, enter binding contracts, and to special tax exemptions. An adult male citizen with the full complement of legal and political rights was called (). Citizens who were elected their assemblies, whereupon the assemblies elected magistrates, enacted legislation, presided over trials in capital cases, declared war and peace, and forged or dissolved treaties. There were two types of legislative assemblies: the ('committees'), which were assemblies of all citizens , and the ("councils"), which were assemblies of specific groups of citizens .

Citizens were organized on the basis of centuries and

The legal status of Roman citizenship was limited and a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights, such as the right to trial and appeal, marry, vote, hold office, enter binding contracts, and to special tax exemptions. An adult male citizen with the full complement of legal and political rights was called (). Citizens who were elected their assemblies, whereupon the assemblies elected magistrates, enacted legislation, presided over trials in capital cases, declared war and peace, and forged or dissolved treaties. There were two types of legislative assemblies: the ('committees'), which were assemblies of all citizens , and the ("councils"), which were assemblies of specific groups of citizens .

Citizens were organized on the basis of centuries and

Roman history

The history of Rome includes the history of the Rome, city of Rome as well as the Ancient Rome, civilisation of ancient Rome. Roman history has been influential on the modern world, especially in the history of the Catholic Church, and Roman la ...

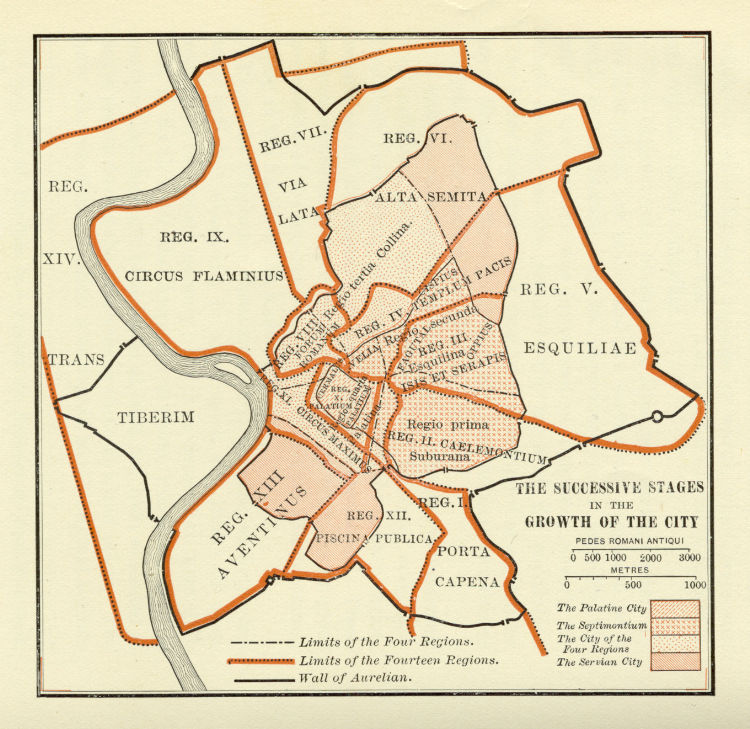

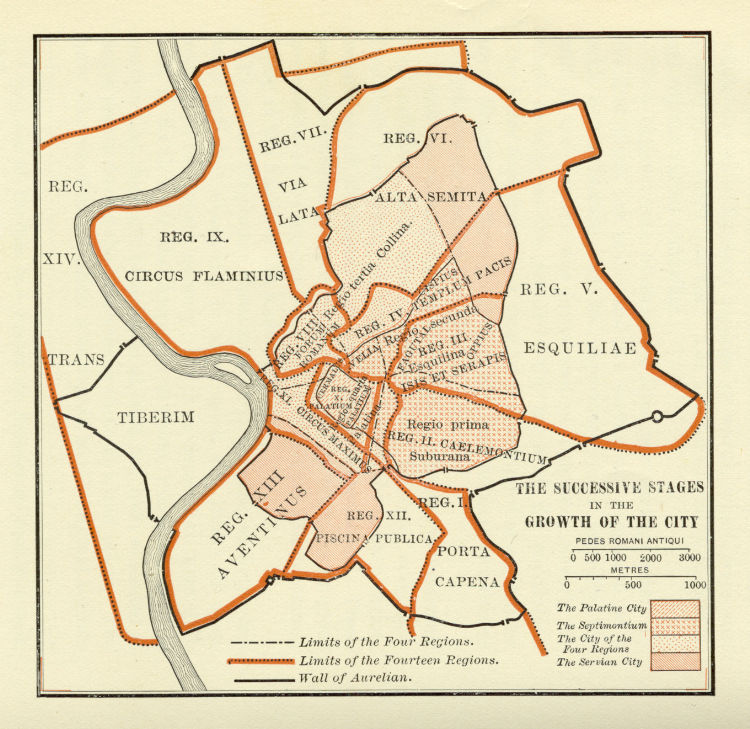

when the city and its territory were ruled by kings. According to tradition, the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding , with settlements around the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; Classical Latin: ''Palatium''; Neo-Latin: ''Collis/Mons Palatinus''; ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city; it has been called "the first nucleus of the ...

along the river Tiber

The Tiber ( ; ; ) is the List of rivers of Italy, third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the R ...

in central Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic .

Little is certain about the kingdom's history as no records and few inscriptions from the time of the kings have survived. The accounts of this period written during the Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

and the Empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

are thought largely to be based on oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

.

Origin

Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

and Empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

) included a ford where one could cross the river Tiber

The Tiber ( ; ; ) is the List of rivers of Italy, third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the R ...

in central Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. The Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; Classical Latin: ''Palatium''; Neo-Latin: ''Collis/Mons Palatinus''; ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city; it has been called "the first nucleus of the ...

and hills surrounding it provided easily defensible positions in the wide fertile plain surrounding them. Each of these features contributed to the success of the city.

The traditional version of Roman history, which has come down principally through Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

(64 or 59 BC – AD 12 or 17), Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

(46–120), and Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus (,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was ''atticistic'' – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

...

( 60 BC – after 7 BC), recounts that a series of seven kings ruled the settlement in Rome's first centuries. The traditional chronology, as codified by Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Virgil and Cicero). He is sometimes call ...

(116 BC – 27 BC) and Fabius Pictor ( 270 – 200 BC), allows 243 years for their combined reigns, an average of almost 35 years. Since the work of Barthold Georg Niebuhr

Barthold Georg Niebuhr (27 August 1776 – 2 January 1831) was a Danish–German statesman, banker, and historian who became Germany's leading historian of Ancient Rome and a founding father of modern scholarly historiography. By 1810 Niebuhr wa ...

, modern scholarship has generally discounted this schema. The Gauls

The Gauls (; , ''Galátai'') were a group of Celts, Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age Europe, Iron Age and the Roman Gaul, Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). Th ...

destroyed many of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia

The Battle of the Allia was fought between the Senones – a Gauls, Gallic tribe led by Brennus (leader of the Senones), Brennus, who had invaded Northern Italy – and the Roman Republic.

The battle was fought at the confluence of the Tibe ...

in 390 BC (according to Varro; according to Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

, the battle occurred in 387–6), and what remained eventually fell prey to time or to theft. With no contemporary records of the kingdom surviving, all accounts of the Roman kings must be carefully questioned.

Monarchy

The kings followingRomulus

Romulus (, ) was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of th ...

, the city's founder, were elected by the people of Rome to serve for life, and did not rely upon military force to gain or keep the throne. The only king to break fully with this tradition was Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, ''ab urbe condita libri'', wikisource:From_the_ ...

, the final king, who according to tradition seized power from his predecessor and ruled as a tyrant.

The insignia of the kings of Rome were twelve lictor

A lictor (possibly from Latin language, Latin ''ligare'', meaning 'to bind') was a Ancient Rome, Roman civil servant who was an attendant and bodyguard to a Roman magistrate, magistrate who held ''imperium''. Roman records describe lictors as hav ...

s (attendants or servants) wielding the symbolic fasces

A fasces ( ; ; a , from the Latin word , meaning 'bundle'; ) is a bound bundle of wooden rods, often but not always including an axe (occasionally two axes) with its blade emerging. The fasces is an Italian symbol that had its origin in the Etrus ...

bearing axes, the right to sit upon a curule seat

A curule seat is a design of a (usually) foldable and transportable chair noted for its uses in Ancient Rome and Europe through to the 20th century. Its status in early Rome as a symbol of political or military power carried over to other civiliza ...

, the purple ''toga picta'', red shoes, and a white diadem

A diadem is a Crown (headgear), crown, specifically an ornamental headband worn by monarchs and others as a badge of Monarch, royalty.

Overview

The word derives from the Ancient Greek, Greek διάδημα ''diádēma'', "band" or "fillet", fro ...

around the head. Of all these insignia, the most important was the purple ''toga picta''.

Chief Executive

The king was invested with supreme military, executive, and judicial authority through the use of ''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

'', formally granted to the king by the Curiate Assembly with the passing of the ''Lex curiata de imperio

In the constitution of ancient Rome, the ''lex curiata de imperio'' (plural ''leges curiatae'') was the law confirming the rights of higher magistrates to hold power, or ''imperium''. In theory, it was passed by the '' comitia curiata'', which w ...

'' at the beginning of each king's reign. The ''imperium'' of the king was held for life and protected him from ever being brought to trial for his actions. As the king was the sole owner of ''imperium'' in Rome at the time, he possessed ultimate executive power

The executive branch is the part of government which executes or enforces the law.

Function

The scope of executive power varies greatly depending on the political context in which it emerges, and it can change over time in a given country. In ...

and unchecked military authority as the commander-in-chief of all of the Roman legion

The Roman legion (, ) was the largest military List of military legions, unit of the Roman army, composed of Roman citizenship, Roman citizens serving as legionary, legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 i ...

s. Also, the laws that kept citizens safe from magistrates' misuse of ''imperium'' did not exist during the monarchical period.

The king had the power to either appoint or nominate all officials to offices. He would appoint a ''tribunus celerum'' to serve as both the tribune of the Ramnes tribe in Rome and as the commander of the king's personal bodyguard, the ''celeres

__NoToC__

The ''celeres'' (, ) were the bodyguard of the kings of Rome and the earliest cavalry unit in the Roman military.Livy, i. 15 (). Traditionally established by Romulus, the legendary founder and first King of Rome, the celeres comprised ...

''. The king was required to appoint the tribune upon entering office and the tribune left office upon the king's death. The tribune was second in rank to the king and also possessed the power to convene the Curiate Assembly and lay legislation before it.

Another officer appointed by the king was the ''praefectus urbi

The ''praefectus urbanus'', also called ''praefectus urbi'' or urban prefect in English, was prefect of the city of Rome, and later also of Constantinople. The office originated under the Roman kings, continued during the Republic and Empire, an ...

'', who acted as the warden of the city. When the king was absent from the city, the prefect held all of the king's powers and abilities, even to the point of being bestowed with ''imperium'' while inside the city.

The king also received the right to be the only person to appoint patricians

The patricians (from ) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after the Conflict of the Orders (494 BC to 287 B ...

to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

Chief Priest

What is known for certain is that the king alone possessed the right to theaugury

Augury was a Greco- Roman religious practice of observing the behavior of birds, to receive omens. When the individual, known as the augur, read these signs, it was referred to as "taking the auspices". "Auspices" () means "looking at birds". ...

on behalf of Rome as its chief augur

An augur was a priest and official in the ancient Rome, classical Roman world. His main role was the practice of augury, the interpretation of the will of the List of Roman deities, gods by studying events he observed within a predetermined s ...

, and no public business could be performed without the will of the gods made known through auspices. The people knew the king as a mediator between them and the gods (cf. Latin ''pontifex'', "bridge-builder", in this sense, between men and the gods) and thus viewed the king with religious awe. This made the king the head of the national religion and its chief executive. Having the power to control the Roman calendar

The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. Although the term is primarily used for Rome's pre-Julian calendars, it is often used inclusively of the Julian calendar established by Julius Caesar in 46&nbs ...

, he conducted all religious ceremonies and appointed lower religious offices and officers. It is said that Romulus himself instituted the augurs and was believed to have been the best augur of all. Likewise, King Numa Pompilius

Numa Pompilius (; 753–672 BC; reigned 715–672 BC) was the Roman mythology, legendary second king of Rome, succeeding Romulus after a one-year interregnum. He was of Sabine origin, and many of Rome's most important religious and political ins ...

instituted the pontiff

In Roman antiquity, a pontiff () was a member of the most illustrious of the colleges of priests of the Roman religion, the College of Pontiffs."Pontifex". "Oxford English Dictionary", March 2007 The term ''pontiff'' was later applied to any h ...

s and through them developed the foundations of the religious dogma of Rome.

Chief Legislator

Under the kings, the Senate and Curiate Assembly had very little power and authority. They were not independent since they lacked the right to meet together and discuss questions of state at their own will. They could be called together only by the king (and the tribune in the case of the Curiate Assembly) and could discuss only the matters that the king laid before them. While the Curiate Assembly had the power to pass laws that had been submitted by the king, the Senate was effectively an honorary council. It could advise the king on his action but by no means could prevent him from acting. The only thing that the king could not do without the approval of the Senate and the Curiate Assembly was to declare war against a foreign nation.Chief Judge

The king's ''imperium'' both granted him military powers and qualified him to pronounce legal judgement in all cases as the chief justice of Rome. Though he could assign pontiffs to act as minor judges in some cases, he had supreme authority in all cases brought before him, both civil and criminal. This made the king supreme in times of both war and peace. While some writers believed there was no appeal from the king's decisions, others believed that a proposal for appeal could be brought before the king by any patrician during a meeting of the Curiate Assembly. To assist the king, a council advised him during all trials, but this council had no power to control his decisions. Also, two criminal detectives (''quaestores parricidi'') were appointed by him as well as a two-man criminal court (''duumviri perduellionis''), which oversaw cases of treason. According toLivy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, ''ab urbe condita libri'', wikisource:From_the_ ...

, the seventh and final king of Rome, judged capital criminal cases without the advice of counsellors, thereby creating fear amongst those who might think to oppose him.

Election of the kings

Whenever a king died, Rome entered a period ofinterregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

. Supreme power of the state would devolve to the Senate, which was responsible for finding a new king. The Senate would assemble and appoint one of its own members—the interrex

The interrex (plural interreges) was an extraordinary magistrate during the Roman Kingdom and Republic. Initially, the interrex was appointed after the death of the king of Rome until the election of his successor, hence its name—a ruler "betwee ...

—to serve for a period of five days with the sole purpose of nominating the next king of Rome. If no king were nominated at the end of five days, with the Senate's consent the interrex would appoint another Senator to succeed him for another five-day term. This process would continue until a new king was elected. Once the interrex found a suitable nominee to the kingship, he would bring the nominee before the Senate and the Curiate would review him. If the Senate passed the nominee, the interrex would convene the Curiate Assembly and preside over it during the election of the king. Once the nominee was proposed to the Curiate Assembly, the citizens of Rome could either accept or reject him. If accepted, the king-elect did not immediately enter office. Two other acts still had to take place before he was invested with the full regal authority and power.

First, it was necessary to obtain the divine will of the gods respecting his appointment by means of the auspices, since the king would serve as high priest of Rome. This ceremony was performed by an augur, who conducted the king-elect to the citadel, where he was placed on a stone seat as the people waited below. If found worthy of the kingship, the augur announced that the gods had given favourable tokens, thus confirming the king's priestly character. The second act which had to be performed was the conferral of the ''imperium'' upon the king. The Curiate Assembly's previous vote only determined who was to be king, and had not by that act bestowed the necessary power of the king upon him. Accordingly, the king himself proposed to the Curiate Assembly a law granting him ''imperium'', and the Curiate Assembly by voting in favor of the law would grant it. In theory, the people of Rome elected their leader, but the Senate had most of the control over the process.

Senate

According to legend, Romulus established the Senate after he founded Rome by personally selecting the most noble men (wealthy men with legitimate wives and children) to serve as a council for the city. As such, the Senate was the King's advisory council as theCouncil of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

. The Senate was composed of 300 senators, with 100 senators representing each of the three ancient tribes of Rome: the Ramnes (Latins

The term Latins has been used throughout history to refer to various peoples, ethnicities and religious groups using Latin or the Latin-derived Romance languages, as part of the legacy of the Roman Empire. In the Ancient World, it referred to th ...

), Tities (Sabines

The Sabines (, , , ; ) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains (see Sabina) of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines divided int ...

), and Luceres (Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

). Within each tribe, a senator was selected from each of the tribe's ten curia

Curia (: curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally probably had wider powers, they came to meet ...

e. The king had the sole authority to appoint the senators, but this selection was done in accordance with ancient custom.

Under the monarchy, the Senate possessed very little power and authority as the king held most of the political power of the state and could exercise those powers without the Senate's consent. The chief function of the Senate was to serve as the king's council and be his legislative coordinator. Once legislation proposed by the king passed the Curiate Assembly, the Senate could either veto it or accept it as law. The king was, by custom, to seek the advice of the Senate on major issues. However, it was left to him to decide what issues, if any, were brought before them and he was free to accept or reject their advice as he saw fit. Only the king possessed the power to convene the Senate, except during the interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

, during which the Senate possessed the authority to convene itself.

Military

Kings of Rome

;''Years BC''Romulus

Romulus (, ) was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of th ...

from:-716 till:-673 text: Numa

from:-673 till:-642 text: Tullus

from:-642 till:-616 text: Ancus

from:-616 till:-579 text: Priscus

Priscus of Panium (; ; 410s/420s AD – after 472 AD) was an Eastern Roman diplomat and Greek historian and rhetorician (or sophist)...: "For information about Attila, his court and the organization of life generally in his realm we have the ...

from:-579 till:-535 text: Servius Servius may refer to:

* Servius (praenomen), a personal name during the Roman Republic

* Servius the Grammarian (fl. 4th/5th century), Roman Latin grammarian

* Servius Asinius Celer (died AD 46), Roman senator

* Servius Cornelius Cethegus, Roma ...

from:-535 till:-509 text: Superbus

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

's chronology of reign-lengths. Consult particular article for details of each king.''

Romulus

Son of the

Son of the Vestal Virgin

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals (, singular ) were priestesses of Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals were unlike any other public priesthood. They were chosen before puberty from several s ...

Rhea Silvia

Rhea (or Rea) Silvia (), also known as Ilia, (as well as other names) was the mythical mother of the twins Romulus and Remus, who founded the city of Rome.Livy I.4.2 This event was portrayed numerous times in Roman art. Her story is told in the ...

, ostensibly by the god Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

, the legendary Romulus

Romulus (, ) was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of th ...

was Rome's founder and first king. After he and his twin brother Remus had deposed King Amulius of Alba and reinstated the king's brother and their grandfather Numitor to the throne, they decided to build a city in the area where they had been abandoned as infants. After killing Remus in a dispute, Romulus began building the city on the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; Classical Latin: ''Palatium''; Neo-Latin: ''Collis/Mons Palatinus''; ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city; it has been called "the first nucleus of the ...

. His work began with fortifications. He permitted men of all classes to come to Rome as citizens, including slaves and freemen without distinction. He is credited with establishing the city's religious, legal and political institutions. The kingdom was established by unanimous acclaim with him at the helm when Romulus called the citizenry to a council for the purposes of determining their government.

Romulus established the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

as an advisory council with the appointment of 100 of the most noble men in the community. These men he called ''patres'' (from ''pater'', father, head), and their descendants became the patricians

The patricians (from ) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after the Conflict of the Orders (494 BC to 287 B ...

. To project command, he surrounded himself with attendants, in particular the twelve lictors. He created three divisions of horsemen (''equites''), called ''centuries'': ''Ramnes'' (Romans), ''Tities'' (after the Sabine king) and ''Luceres'' (Etruscans). He also divided the populace into 30 ''curia

Curia (: curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally probably had wider powers, they came to meet ...

e'', named after 30 of the Sabine women who had intervened to end the war between Romulus and Tatius. The ''curiae'' formed the voting units in the popular assemblies (''Comitia Curiata'').

Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as '' The Rape of the Sabine Women''. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighbouring tribes to a festival in Rome where the Romans committed a mass abduction of young women from among the attendees. The accounts vary from 30 to 683 women taken, a significant number for a population of 3,000 Latins (and presumably for the Sabines as well). War broke out when Romulus refused to return the captives. After the Sabines made three unsuccessful attempts to invade the hill settlements of Rome, the women themselves intervened during the Battle of the Lacus Curtius to end the war. The two peoples were united in a joint kingdom, with Romulus and the Sabine king

Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as '' The Rape of the Sabine Women''. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighbouring tribes to a festival in Rome where the Romans committed a mass abduction of young women from among the attendees. The accounts vary from 30 to 683 women taken, a significant number for a population of 3,000 Latins (and presumably for the Sabines as well). War broke out when Romulus refused to return the captives. After the Sabines made three unsuccessful attempts to invade the hill settlements of Rome, the women themselves intervened during the Battle of the Lacus Curtius to end the war. The two peoples were united in a joint kingdom, with Romulus and the Sabine king Titus Tatius

According to the Roman foundation myth, Titus Tatius, also called Tatius Sabinus, was king of the Sabines from Cures and joint-ruler of the Kingdom of Rome for several years.

During the reign of Romulus, the first king of Rome, Tatius dec ...

sharing the throne. In addition to the war with the Sabines, Romulus waged war with the Fidenates and Veientes and others.

He reigned for thirty-seven years.Plutarch ''Life of Romulus'' 29.7 According to the legend, Romulus vanished at age fifty-four while reviewing his troops on the Campus Martius. He was reported to have been taken up to Mt. Olympus in a whirlwind and made a god. After initial acceptance by the public, rumours and suspicions of foul play by the patricians began to grow. In particular, some thought that members of the nobility had murdered him, dismembered his body, and buried the pieces on their land. These were set aside after an esteemed nobleman testified that Romulus had come to him in a vision and told him that he was the god Quirinus

In Roman mythology and Roman religion, religion, Quirinus ( , ) is an early god of the Ancient Rome, Roman state. In Augustus, Augustan Rome, ''Quirinus'' was also an epithet of Janus, Mars (mythology), Mars, and Jupiter (god), Jupiter.

Name

...

. He became not only one of the three major gods of Rome, but the very likeness of the city itself.

A replica of Romulus's hut was maintained in the centre of Rome until the end of the Roman Empire.

Numa Pompilius

After Romulus died, there was an

After Romulus died, there was an interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

for one year, during which ten men chosen from the Senate governed Rome as successive '' interreges''. Under popular pressure, the Senate finally chose the Sabine Numa Pompilius

Numa Pompilius (; 753–672 BC; reigned 715–672 BC) was the Roman mythology, legendary second king of Rome, succeeding Romulus after a one-year interregnum. He was of Sabine origin, and many of Rome's most important religious and political ins ...

to succeed Romulus, on account of his reputation for justice and piety. The choice was accepted by the Curiate Assembly.

Numa's reign was marked by peace and religious reform. He constructed a new temple to Janus

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus ( ; ) is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces. The month of January is named for Janus (''Ianu ...

and, after establishing peace with Rome's neighbours, closed the doors of the temple to indicate a state of peace. They remained closed for the rest of his reign.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

, ''Ab urbe condita

''Ab urbe condita'' (; 'from the founding of Rome, founding of the City'), or (; 'in the year since the city's founding'), abbreviated as AUC or AVC, expresses a date in years since 753 BC, 753 BC, the traditional founding of Rome. It is ...

'', 1:19 He established the Vestal Virgins

In Religion in ancient Rome, ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals (, singular ) were Glossary of ancient Roman religion#sacerdos, priestesses of Vesta (mythology), Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals ...

at Rome, as well as the Salii, and the flamines for Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

and Quirinus

In Roman mythology and Roman religion, religion, Quirinus ( , ) is an early god of the Ancient Rome, Roman state. In Augustus, Augustan Rome, ''Quirinus'' was also an epithet of Janus, Mars (mythology), Mars, and Jupiter (god), Jupiter.

Name

...

. He also established the office and duties of '' pontifex maximus''. Numa reigned for 43 years. He reformed the Roman calendar

The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. Although the term is primarily used for Rome's pre-Julian calendars, it is often used inclusively of the Julian calendar established by Julius Caesar in 46&nbs ...

by adjusting it for the solar and lunar year, as well as by adding the months of January and February to bring the total number of months to twelve.

Tullus Hostilius

Tullus Hostilius

Tullus Hostilius (; r. 672–640 BC) was the legendary third king of Rome. He succeeded Numa Pompilius and was succeeded by Ancus Marcius. Unlike his predecessor, Tullus was known as a warlike king who, according to the Roman historian Livy, b ...

was as warlike as Romulus had been, completely unlike Numa as he lacked any respect for the gods. Tullus waged war against Alba Longa

Alba Longa (occasionally written Albalonga in Italian sources) was an ancient Latins (Italic tribe), Latin city in Central Italy in the vicinity of Lake Albano in the Alban Hills. The ancient Romans believed it to be the founder and head of the ...

, Fidenae and Veii and the Sabines

The Sabines (, , , ; ) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains (see Sabina) of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines divided int ...

. During Tullus's reign, the city of Alba Longa was completely destroyed and Tullus integrated its population into Rome. Tullus is attributed with constructing a new home for the Senate, the Curia Hostilia

The Curia Hostilia was one of the original senate houses or "curiae" of the Roman Republic. It was believed to have begun as a temple where the warring tribes laid down their arms during the reign of Romulus (r. c. 771–717 BC). During the early ...

, which survived for 562 years after his death.

According to Livy, Tullus neglected the worship of the gods until, towards the end of his reign, he fell ill and became superstitious. However, when Tullus called upon Jupiter and begged assistance, Jupiter responded with a bolt of lightning that burned the king and his house to ashes. His reign lasted for 32 years.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

, ''ab urbe condita libri

The ''History of Rome'', perhaps originally titled , and frequently referred to as (), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by the Roman historian Titus Livius, better known in English as "Livy". ...

'', I

Ancus Marcius

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson,

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson, Ancus Marcius

Ancus Marcius () was the Roman mythology, legendary fourth king of Rome, who traditionally reigned 24 years. Upon the death of the previous king, Tullus Hostilius, the Roman Senate appointed an interrex, who in turn called a session of the Roman a ...

. Much like his grandfather, Ancus did little to expand the borders of Rome and only fought wars to defend the territory. He also built Rome's first prison on the Capitoline Hill

The Capitolium or Capitoline Hill ( ; ; ), between the Roman Forum, Forum and the Campus Martius, is one of the Seven Hills of Rome.

The hill was earlier known as ''Mons Saturnius'', dedicated to the god Saturn (mythology), Saturn. The wo ...

.

Ancus further fortified the Janiculum

The Janiculum (; ), occasionally known as the Janiculan Hill, is a hill in western Rome, Italy. Although it is the second-tallest hill (the tallest being Monte Mario) in the contemporary city of Rome, the Janiculum does not figure among the pro ...

Hill on the western bank, and built the first bridge across the Tiber River

The Tiber ( ; ; ) is the List of rivers of Italy, third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the R ...

. He also founded the port of Ostia Antica

Ostia Antica () is an ancient Roman city and the port of Rome located at the mouth of the Tiber. It is near modern Ostia, southwest of Rome. Due to silting and the invasion of sand, the site now lies from the sea. The name ''Ostia'' (the pl ...

on the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (, ; or ) , , , , is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenians, Tyrrhenian people identified with the Etruscans of Italy.

Geography

The sea is bounded by the islands of C ...

and established Rome's first salt works, as well as the city's first aqueduct. Rome grew, as Ancus used diplomacy to peacefully unite smaller surrounding cities into alliance with Rome. Thus, he completed the conquest of the Latins and relocated them to the Aventine Hill

The Aventine Hill (; ; ) is one of the Seven Hills on which ancient Rome was built. It belongs to Ripa, the modern twelfth ''rione'', or ward, of Rome.

Location and boundaries

The Aventine Hill is the southernmost of Rome's seven hills. I ...

, thus forming the plebeian

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins of the gro ...

class of Romans.

He died a natural death, like his grandfather, after 25 years as king, marking the end of Rome's Latin–Sabine kings.

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (), or Tarquin the Elder, was the legendary fifth king of Rome and first of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned for thirty-eight years.Livy, '' ab urbe condita libri'', I Tarquinius expanded Roman power through military ...

was the fifth king of Rome and the first of Etruscan birth. After immigrating to Rome, he gained favor with Ancus, who later adopted him as son. Upon ascending the throne, he waged wars against the Sabines and Etruscans, doubling the size of Rome and bringing great treasures to the city. To accommodate the influx of population, the Aventine and Caelian hill

The Caelian Hill ( ; ; ) is one of the famous seven hills of Rome.

Geography

The Caelian Hill is a moderately long promontory about long, to wide, and tall in the park near the Temple of Claudius. The hill overlooks a plateau from wh ...

s were populated.

One of his first reforms was to add 100 new members to the Senate from the conquered Etruscan tribes, bringing the total number of senators to 200. He used the treasures Rome had acquired from the conquests to build great monuments for Rome. Among these were Rome's great sewer systems, the Cloaca Maxima, which he used to drain the swamp-like area between the Seven Hills of Rome. In its place, he began construction on the Roman Forum

A forum (Latin: ''forum'', "public place outdoors", : ''fora''; English : either ''fora'' or ''forums'') was a public square in a municipium, or any civitas, of Ancient Rome reserved primarily for the vending of goods; i.e., a marketplace, alon ...

. He also founded the Roman games.

Priscus initiated great building projects, including the city's first bridge, the Pons Sublicius. The most famous is the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian language, Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot racing, chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine Hill, Avent ...

, a giant stadium for chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

races. After that, he started the building of the temple-fortress to the god Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. However, before it was completed, he was killed by a son of Ancus Marcius, after 38 years as king. His reign is best remembered for introducing the Roman symbols of military and civil offices, and the Roman triumph

The Roman triumph (') was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or, in some historical t ...

, being the first Roman to celebrate one.

Servius Tullius

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law Servius Tullius

Servius Tullius was the legendary sixth king of Rome, and the second of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned from 578 to 535 BC. Roman and Greek sources describe his servile origins and later marriage to a daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Pri ...

, Rome's second king of Etruscan birth, and the son of a slave. Like his father-in-law, Servius fought successful wars against the Etruscans. He used the booty to build the first wall all around the Seven Hills of Rome, the ''pomerium

The ''pomerium'' or ''pomoerium'' was a religious boundary around the city of Rome and cities controlled by Rome. In legal terms, Rome existed only within its ''pomerium''; everything beyond it was simply territory ('' ager'') belonging to Rome ...

''. He also reorganized the army.

Servius Tullius instituted a new constitution, further developing the citizen classes. He instituted Rome's first census

A census (from Latin ''censere'', 'to assess') is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording, and calculating population information about the members of a given Statistical population, population, usually displayed in the form of stati ...

, which divided the population into five economic classes, and formed the Centuriate Assembly. He used the census to divide the population into four urban tribes based on location, thus establishing the Tribal Assembly. He also oversaw the construction of the Temple of Diana on the Aventine Hill

The Aventine Hill (; ; ) is one of the Seven Hills on which ancient Rome was built. It belongs to Ripa, the modern twelfth ''rione'', or ward, of Rome.

Location and boundaries

The Aventine Hill is the southernmost of Rome's seven hills. I ...

.

Servius' reforms made a big change in Roman life: voting rights based on socio-economic status, favouring elites. However, over time, Servius increasingly favoured the poor in order to gain support from plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not Patrician (ancient Rome), patricians, as determined by the Capite censi, census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Et ...

, often at the expense of patricians. After a 44-year reign, Servius was killed in a conspiracy by his daughter Tullia and her husband Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, ''ab urbe condita libri'', wikisource:From_the_ ...

.

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

The seventh and final king of Rome was

The seventh and final king of Rome was Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, ''ab urbe condita libri'', wikisource:From_the_ ...

. He was the son of Priscus and the son-in-law of Servius, whom he and his wife had killed.

Tarquinius waged a number of wars against Rome's neighbours, including against the Volsci

The Volsci (, , ) were an Italic tribe, well known in the history of the first century of the Roman Republic. At the time they inhabited the partly hilly, partly marshy district of the south of Latium, bounded by the Aurunci and Samnites on the ...

, Gabii

Gabii was an ancient city of Latium, located due east of Rome along the Via Praenestina, which was in early times known as the ''Via Gabina''.

It was on the south-eastern perimeter of an extinct volcanic crater lake, approximately circular i ...

and the Rutuli

The Rutuli or Rutulians were an ancient people in Italy. The Rutuli were located in a territory whose capital was the ancient town of Ardea, located about 35 km southeast of Rome.

Thought to have been descended from the Umbri and the P ...

. He also secured Rome's position as head of the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

cities. He also engaged in a series of public works, notably the completion of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus (; ; ), was the most important temple in Ancient Rome, located on the Capitoline Hill. It was surrounded by the ''Area Capitolina'', a precinct where numer ...

, and works on the Cloaca Maxima and the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian language, Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot racing, chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine Hill, Avent ...

. However, Tarquin's reign is remembered for his use of violence and intimidation to control Rome and his disrespect for Roman custom and the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

.

Tensions came to a head when the king's son, Sextus Tarquinius

Sextus Tarquinius was one of the sons of the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. In the original account of the Tarquin dynasty presented by Fabius Pictor, he is the second son, between Titus Tarquinius, Titus and Arruns Tarquinius ( ...

, raped Lucretia, wife and daughter to powerful Roman nobles. Lucretia told her relatives about the attack, and committed suicide to avoid the dishonour of the episode. Four men, led by Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus (died ) was the semi-legendary founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of its two first consuls. Depicted as responsible for the expulsion of his uncle, the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus after the suicide of L ...

, and including Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus

Lucius Tarquinius Ar. f. Ar. n. Collatinus was one of the first two consuls of the Roman Republic in 509 BC, together with Lucius Junius Brutus. The two men had led the revolution which overthrew the Roman monarchy. He was forced to resign his ...

, Publius Valerius Poplicola

Publius Valerius Poplicola or Publicola (died 503 BC) was one of four Roman aristocrats who led the overthrow of the monarchy, and became a Roman consul, the colleague of Lucius Junius Brutus in 509 BC, traditionally considered the first year o ...

, and Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus

Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus is a semi-legendary figure in early Roman history. He was the first Suffect Consul of Rome and was also the father of Lucretia, whose rape by Sextus Tarquinius, followed by her suicide, resulted in the dethroneme ...

incited a revolution that deposed and expelled Tarquinius and his family from Rome in 509 BC.

Tarquin was viewed so negatively that the word for king, '' rex'', held a negative connotation in the Latin language until the fall of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.

Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus (died ) was the semi-legendary founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of its two first consuls. Depicted as responsible for the expulsion of his uncle, the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus after the suicide of L ...

and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus

Lucius Tarquinius Ar. f. Ar. n. Collatinus was one of the first two consuls of the Roman Republic in 509 BC, together with Lucius Junius Brutus. The two men had led the revolution which overthrew the Roman monarchy. He was forced to resign his ...

became Rome's first consuls

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

, marking the beginning of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

. This new government would survive for the next 500 years until the rise of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

and Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

, and would cover a period during which Rome's authority and area of control extended to cover vast areas of Europe, North Africa, and West Asia. He ruled 25 years.

Public offices after the monarchy

The constitutional history of theRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

began with the revolution that overthrew the monarchy in 509 BC and ended with constitutional reforms that transformed the Republic into what would effectively be the Roman Empire, in 27 BC. The Roman Republic's constitution was a constantly evolving, unwritten set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent, by which the government and its politics operated.

Senate

The senate's authority derived from the senators' esteem and prestige. This esteem and prestige were based on both precedent and custom, as well as the senators' calibre and reputation. The senate passed decrees called . These were officially "advice" from the senate to a magistrate, but in practice, the magistrates usually followed them. Through the course of the middle republic and Rome's expansion, the senate became more dominant in the state: the only institution with the expertise to administer the empire effectively, it controlled state finances, assignment of magistrates, external affairs, and deployment of military forces. Also, a powerful religious body, it received reports of omens and directed Roman responses thereto. When its prerogatives started to be challenged in the 2nd century, the senate lost its customary preapproval for legislation. Moreover, after the precedent set in 121 BC with the killing of Gaius Gracchus, the senate claimed to assume the power to issue a : such decrees directed magistrates to take whatever actions were necessary to safeguard the state, irrespective of legality, and signalled the senate's willingness to support that magistrate if such actions were later challenged in the courts. Its members were usually appointed by censors, who ordinarily selected newly elected magistrates for membership in the senate, making the senate a partially elected body. Status was not hereditary and there were always some new men, though sons of former magistrates found it easier to be elected to the qualifying magistracies. During emergencies, a dictator could be appointed for the purpose of appointing senators (as was done after theBattle of Cannae

The Battle of Cannae (; ) was a key engagement of the Second Punic War between the Roman Republic and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, fought on 2 August 216 BC near the ancient village of Cannae in Apulia, southeast Italy. The Carthaginians and ...

). However, by the end of the republic men such as Caesar and the members of the Second Triumvirate usurped these powers for themselves.

Legislative assemblies

The legal status of Roman citizenship was limited and a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights, such as the right to trial and appeal, marry, vote, hold office, enter binding contracts, and to special tax exemptions. An adult male citizen with the full complement of legal and political rights was called (). Citizens who were elected their assemblies, whereupon the assemblies elected magistrates, enacted legislation, presided over trials in capital cases, declared war and peace, and forged or dissolved treaties. There were two types of legislative assemblies: the ('committees'), which were assemblies of all citizens , and the ("councils"), which were assemblies of specific groups of citizens .

Citizens were organized on the basis of centuries and

The legal status of Roman citizenship was limited and a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights, such as the right to trial and appeal, marry, vote, hold office, enter binding contracts, and to special tax exemptions. An adult male citizen with the full complement of legal and political rights was called (). Citizens who were elected their assemblies, whereupon the assemblies elected magistrates, enacted legislation, presided over trials in capital cases, declared war and peace, and forged or dissolved treaties. There were two types of legislative assemblies: the ('committees'), which were assemblies of all citizens , and the ("councils"), which were assemblies of specific groups of citizens .

Citizens were organized on the basis of centuries and tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

, which each gathered into their own assemblies. The ('Centuriate Assembly') was the assembly of the centuries (that is., soldiers). The Comitia Centuriata's president was usually a consul. The centuries voted, one at a time, until a measure received support from a majority. The Comitia Centuriata elected magistrates who had (consuls and praetors). It also elected censors. Only the Comitia Centuriata could declare war and ratify the results of a census. It served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases.

The assembly of the tribes, that is, the citizens of Rome, the Comitia Tributa, was presided over by a consul, and composed of 35 tribes. Once a measure received support from a majority of the tribes, voting ended. While it did not pass many laws, the Comitia Tributa did elect quaestors, curule aedile

Aedile ( , , from , "temple edifice") was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings () and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public orde ...

s, and military tribunes. The Plebeian Council was identical to the assembly of the tribes but excluded the patricians

The patricians (from ) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after the Conflict of the Orders (494 BC to 287 B ...

. They elected their own officers, plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles. Usually, a plebeian tribune would preside over the assembly. This assembly passed most laws and could act as a court of appeal.

Magistrates

Each republican magistrate held certain constitutional powers. Each was assigned a by the Senate. This was the scope of that particular office holder's authority. It could apply to a geographic area or to a particular responsibility or task. The powers of a magistrate came from the people of Rome (both plebeians and patricians). was held by both consuls and praetors. Strictly speaking, it was the authority to command a military force, but in reality, it carried broad authority in other public spheres, such as diplomacy and the justice system. In extreme cases, those with the imperium power could sentence Roman Citizens to death. All magistrates also had the power of (coercion). Magistrates used this to maintain public order by imposing punishment for crimes. Magistrates also had both the power and the duty to look for omens. This power could also be used to obstruct political opponents. One check on a magistrate's power was ('collegiality'). Each magisterial office was held concurrently by at least two people. Another such check was . While in Rome, all citizens were protected from coercion, by , an early form ofdue process

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual p ...

. It was a precursor to . If any magistrate tried to use the powers of the state against a citizen, that citizen could appeal the magistrate's decision to a tribune. In addition, once a magistrate's one-year term of office expired, he would have to wait ten years before serving in that office again. This created problems for some consuls and praetors, and these magistrates occasionally had their extended. In effect, they retained the powers of the office (as a promagistrate

In ancient Rome, a promagistrate () was a person who was granted the power via ''prorogation'' to act in place of an ordinary magistrate in the field. This was normally ''pro consule'' or ''pro praetore'', that is, in place of a consul or praeto ...

) without officially holding that office.

In times of military emergency, a dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute Power (social and political), power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a polity. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to r ...

was appointed for a term of six months. Constitutional government was dissolved, and the dictator was the absolute master of the state. When the dictator's term ended, constitutional government was restored.

The censor was a magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judi ...

in ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

who was responsible for maintaining the census

A census (from Latin ''censere'', 'to assess') is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording, and calculating population information about the members of a given Statistical population, population, usually displayed in the form of stati ...

, supervising public morality

Public morality refers to moral and ethical standards enforced in a society, by law or police work or social pressure, and applied to public life, to the content of the media, and to conduct in public places.

Public morality often means reg ...

, and overseeing certain aspects of the government's finances. The power of the censor was absolute: no magistrate could oppose his decisions, and only another censor who succeeded him could cancel those decisions. The censor's regulation of public morality is the origin of the modern meaning of the words ''censor'' and ''censorship''. During the census, they could enroll citizens in the senate or purge them from the senate.

The consuls

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

of the Roman Republic were the highest-ranking ordinary magistrates. Each served for one year. Consular powers included the kings' former and appointment of new senators. Consuls had supreme power in both civil and military matters. While in the city of Rome, the consuls were the head of the Roman government. They presided over the senate and the assemblies. While abroad, each consul commanded an army. His authority abroad was nearly absolute.

Since the tribunes were considered the embodiment of the plebeians, they were sacrosanct

Sacrosanctity () or inviolability is the declaration of physical inviolability of a place (particularly temples and city walls), a sacred object, or a person. Under Roman law, this was established through sacred law (), which had religious connot ...

. Their sacrosanctity was enforced by a pledge the plebeians took to kill anyone who harmed or interfered with a tribune during his term of office. It was a capital offense to harm a tribune, disregard his veto, or otherwise interfere with him.

Praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

s administered civil law and commanded provincial armies. Aediles

Aedile ( , , from , "temple edifice") was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings () and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public orde ...

were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome, such as managing public games and shows. The quaestor

A quaestor ( , ; ; "investigator") was a public official in ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officia ...

s usually assisted the consuls in Rome, and the governors in the provinces. Their duties were often financial.

Notes and references

Sources

* * * * * ** * *Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

, ''Ab Urbe Condita

''Ab urbe condita'' (; 'from the founding of Rome, founding of the City'), or (; 'in the year since the city's founding'), abbreviated as AUC or AVC, expresses a date in years since 753 BC, 753 BC, the traditional founding of Rome. It is ...

''.

*

*

*

Further reading

* * * {{Authority control 1st-millennium BC disestablishments in Italy 509 BC 750s BC 6th-century BC disestablishments 8th-century BC establishments in Italy Ancient Italian history Former countries Former monarchies of Europe Latial culture Rome Kings Kings States and territories established in the 8th century BC States and territories disestablished in the 6th century BC