Red Scare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Red Scare is a form of

The second Red Scare occurred after

The second Red Scare occurred after

After the Soviet Union signed the non-aggression

After the Soviet Union signed the non-aggression

In 1954, after accusing the army, including war heroes, Senator Joseph McCarthy lost credibility in the eyes of the American public and the Army-McCarthy Hearings were held in the summer of 1954. He was formally censured by his colleagues in Congress and the hearings led by McCarthy came to a close. After the Senate formally censured McCarthy, his political standing and power were significantly diminished, and much of the tension surrounding the idea of a possible communist takeover died down.

From 1955 through 1959, the Supreme Court made several decisions which restricted the ways in which the government could enforce its anti-communist policies, some of which included limiting the federal loyalty program to only those who had access to sensitive information, allowing defendants to face their accusers, reducing the strength of congressional investigation committees, and weakening the Smith Act. In the 1957 case '' Yates v. United States'' and the 1961 case '' Scales v. United States'', the Supreme Court limited Congress's ability to circumvent the First Amendment, and in 1967 during the Supreme Court case '' United States v. Robel'', the Supreme Court ruled that a ban on communists in the defense industry was unconstitutional.

In 1995, the American government declassified details of the Venona Project following the Moynihan Commission, which when combined with the opening of the USSR

In 1954, after accusing the army, including war heroes, Senator Joseph McCarthy lost credibility in the eyes of the American public and the Army-McCarthy Hearings were held in the summer of 1954. He was formally censured by his colleagues in Congress and the hearings led by McCarthy came to a close. After the Senate formally censured McCarthy, his political standing and power were significantly diminished, and much of the tension surrounding the idea of a possible communist takeover died down.

From 1955 through 1959, the Supreme Court made several decisions which restricted the ways in which the government could enforce its anti-communist policies, some of which included limiting the federal loyalty program to only those who had access to sensitive information, allowing defendants to face their accusers, reducing the strength of congressional investigation committees, and weakening the Smith Act. In the 1957 case '' Yates v. United States'' and the 1961 case '' Scales v. United States'', the Supreme Court limited Congress's ability to circumvent the First Amendment, and in 1967 during the Supreme Court case '' United States v. Robel'', the Supreme Court ruled that a ban on communists in the defense industry was unconstitutional.

In 1995, the American government declassified details of the Venona Project following the Moynihan Commission, which when combined with the opening of the USSR

"Political Tests for Professors: Academic Freedom during the McCarthy Years"

by Ellen Schrecker, The University Loyalty Oath, October 7, 1999. {{DEFAULTSORT:Red Scare Aftermath of World War II in the United States Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States Anti-communism in Australia Anti-communism in Canada Anti-communism in the Philippines Anti-communism in the United Kingdom Anti-communism in the United States Anti-Russian sentiment China–United States relations Communism in the United States Conspiracy theories involving communism Far-left politics in the United States History of the Communist Party USA History of the Industrial Workers of the World History of the Socialist Party of America Political and cultural purges Political history of the United States Political repression in the Philippines Political repression in the United Kingdom Political repression in the United States Russia–United States relations Scares Socialism in the United States Soviet Union–United States relations Counter-revolution

moral panic

A moral panic is a widespread feeling of fear that some evil person or thing threatens the values, interests, or well-being of a community or society. It is "the process of arousing social concern over an issue", usually perpetuated by moral e ...

provoked by fear of the rise of left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

ideologies in a society, especially communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

. Historically, red scares have led to mass political persecution, scapegoating

Scapegoating is the practice of singling out a person or group for unmerited blame and consequent negative treatment. Scapegoating may be conducted by individuals against individuals (e.g., "he did it, not me!"), individuals against groups (e.g ...

, and the ousting of those in government positions who have had connections with left-wing movements. The name is derived from the red flag, a common symbol of communism and socialism.

The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which are referred to by this name. The First Red Scare

The first Red Scare was a period during History of the United States (1918–1945), the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of Far-left politics, far-left movements, including Bolsheviks, Bolshevism a ...

, which occurred immediately after World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, revolved around a perceived threat from the American labor movement, anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

revolution, and political radicalism

Radical politics denotes the intent to transform or replace the principles of a society or political system, often through social change, structural change, revolution or radical reform. The process of adopting radical views is termed radica ...

that followed revolutionary socialist

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolu ...

movements in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Second Red Scare, which occurred immediately after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, was preoccupied with the perception that national or foreign communists were infiltrating or subverting American society and the federal government

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

.

Following the end of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, unearthed documents revealed substantial Soviet spy activity in the United States, although many of the agents were never properly identified by Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

.

First Red Scare (1917–1920)

The first Red Scare in the United States accompanied theRussian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

(specifically the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

) and the Revolutions of 1917–1923

The revolutions of 1917–1923 were a revolutionary wave that included political unrest and armed revolts around the world inspired by the success of the Russian Revolution and the disorder created by the aftermath of World War I. The uprisings ...

. Citizens of the United States in the years of World War I (1914–1918) were intensely patriotic; anarchist and left-wing social agitation aggravated national, social, and political tensions. Political scientist and former Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

member Murray Levin wrote that the Red Scare was "a nationwide anti-radical hysteria provoked by a mounting fear and anxiety that a Bolshevik revolution in America was imminent—a revolution that would change Church, home, marriage, civility, and the American way of Life". News media exacerbated such fears, channeling them into anti-foreign sentiment due to the lively debate among recent immigrants from Europe regarding various forms of anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

as possible solutions to widespread poverty. The Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

(IWW), also known as the Wobblies, backed several labor strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became co ...

s in 1916 and 1917. These strikes covered a wide range of industries including steel working, shipbuilding, coal mining, copper mining, and others necessary for wartime activities.

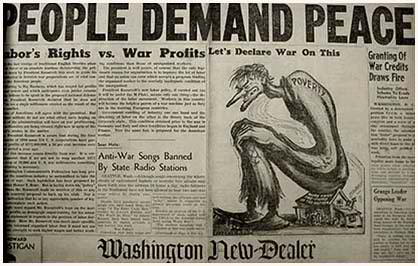

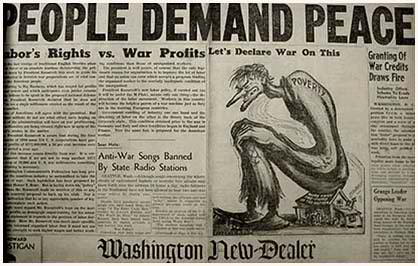

After World War I ended (November 1918), the number of strikes increased to record levels in 1919, with more than 3,600 separate strikes by a wide range of workers, e.g. steel workers, railroad shop workers, and the Boston police department. The press portrayed these worker strikes as "radical threats to American society" inspired by "left-wing, foreign ''agents provocateurs''". The IWW and those sympathetic to workers claimed that the press "misrepresented legitimate labor strikes" as "crimes against society", "conspiracies against the government", and "plots to establish communism". Opponents of labor viewed strikes as an extension of the radical, anarchist foundations of the IWW, which contends that all workers should be united as a social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

and that capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and the wage system should be abolished.

In June 1917, as a response to World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act to prevent any information relating to national defense from being used to harm the United States or to aid her enemies. The Wilson administration

Woodrow Wilson served as the 28th president of the United States from March 4, 1913, to March 4, 1921. A History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat and former governor of New Jersey, Wilson took office after winning the 1912 Uni ...

used this act to make anything "urging treason" a "nonmailable matter". Due to the Espionage Act and the then Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson, 74 separate newspapers were not being mailed.

In April 1919, authorities discovered a plot for mailing 36 bombs to prominent members of the U.S. political and economic establishment: J. P. Morgan Jr., John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

, Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, U.S. Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer, and immigration officials. On June 2, 1919, in eight cities, eight bombs exploded simultaneously. One target was the Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, house of U.S. Attorney General Palmer, where the explosion killed the bomber, who (evidence indicated) was an Italian-American

Italian Americans () are Americans who have full or partial Italians, Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeastern United States, Northeast and industrial Midwestern United States, Midwestern ...

radical from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Afterwards, Palmer ordered the U.S. Justice Department to launch the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchist ...

(1919–21). He deported 249 Russian immigrants on the " Soviet Ark", formed the General Intelligence Unit – a precursor to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) – within the Department of Justice, and used federal agents to jail more than 5,000 citizens and to search homes without respecting their constitutional rights.

In 1918, before the bombings, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

had pressured Congress to legislate the anti-anarchist Sedition Act of 1918 to protect wartime morale by deporting putatively undesirable political people. Law professor David D. Cole reports that President Wilson's "federal government consistently targeted alien radicals, deporting them... for their speech or associations, making little effort to distinguish terrorists from ideological dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 2 ...

s". President Wilson used the Sedition Act of 1918 to limit the exercise of free speech by criminalizing language deemed disloyal to the United States government.

Initially, the press praised the raids; ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' stated: "There is no time to waste on hairsplitting over heinfringement of liberty", and ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' wrote that the injuries inflicted upon the arrested were "souvenirs of the new attitude of aggressiveness which had been assumed by the Federal agents against Reds and suspected-Reds". In the event, twelve publicly prominent lawyers characterized the Palmer Raids as unconstitutional. The critics included future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

, who published ''Report Upon the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice'', documenting systematic violations of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution via Palmer-authorized "illegal acts" and "wanton violence". Defensively, Palmer then warned that a government-deposing left-wing revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

would begin on 1 May 1920—May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

, the International Workers' Day. When it failed to happen, he was ridiculed and lost much credibility. Strengthening the legal criticism of Palmer was that fewer than 600 deportations were substantiated with evidence, out of the thousands of resident aliens arrested and deported. In July 1920, Palmer's once-promising Democratic Party bid for the U.S. presidency failed. Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

was bombed on September 16, 1920, near Federal Hall National Memorial

Federal Hall was the first capitol building of the United States under the Constitution. Serving as the meeting place of the First United States Congress and the site of George Washington's first presidential inauguration, the building existe ...

and the JP Morgan Bank. Although both anarchists and communists were suspected as being responsible for the bombing, ultimately no individuals were indicted for the bombing, in which 38 died and 141 were injured.

In 1919–20, several states enacted " criminal syndicalism" laws outlawing advocacy of violence in effecting and securing social change

Social change is the alteration of the social order of a society which may include changes in social institutions, social behaviours or social relations. Sustained at a larger scale, it may lead to social transformation or societal transformat ...

. The restrictions included limitations on free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recognise ...

. Passage of these laws, in turn, provoked aggressive police investigation of the accused persons, their jailing, and deportation for being ''suspected'' of being either communist or left-wing. Regardless of ideological gradation, the Red Scare did not distinguish between communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, or social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

. This aggressive crackdown on certain ideologies resulted in many Supreme Court cases over free speech. In the 1919 case of '' Schenk v. United States'', the Supreme Court, introducing the clear-and-present-danger test, effectively deemed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 constitutional.

Second Red Scare (1947–1957)

The second Red Scare occurred after

The second Red Scare occurred after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(1939–1945), and is known as "McCarthyism

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a Fear mongering, campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage i ...

" after its best-known advocate, Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

. McCarthyism coincided with an increased and widespread fear of communist espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

that was consequent of the increasing tension in the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

through the Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

occupation of Eastern Europe, the Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

(1948–49), the end of the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led Nationalist government, government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the forces of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Armed conflict continued intermitt ...

, the confessions of spying for the Soviet Union that were made by several high-ranking U.S. government officials, and the outbreak of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

.

Internal causes of the anti-communist fear

The events of the late 1940s, the early 1950s—the trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg (1953), thetrial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, w ...

of Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official who was accused of espionage in 1948 for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjur ...

, the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

(1945–1991) around Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, and the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test in 1949 (RDS-1

The RDS-1 (), also known as Izdeliye 501 (device 501) and First Lightning (), was the nuclear bomb used in the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test. The United States assigned it the code-name Joe-1, in reference to Joseph Stalin. It was de ...

)—surprised the American public, influencing popular opinion about U.S. national security

National security, or national defence (national defense in American English), is the security and Defence (military), defence of a sovereign state, including its Citizenship, citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of ...

, which, in turn, was connected to the fear that the Soviet Union would drop nuclear bombs on the United States, and fear of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA).

In Canada, the 1946 Kellock–Taschereau Commission investigated espionage after top-secret documents concerning RDX

RDX (Research Department Explosive or Royal Demolition Explosive) or hexogen, among other names, is an organic compound with the formula (CH2N2O2)3. It is white, odorless, and tasteless, widely used as an explosive. Chemically, it is classified ...

, radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

and other weapons were handed over to the Soviets by a domestic spy-ring.

At the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 19 ...

, former CPUSA members and NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

spies, Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers, testified that Soviet spies and communist sympathizers had penetrated the U.S. government before, during and after World War II. Other U.S. citizen spies confessed to their acts of espionage in situations where the statute of limitations on prosecuting them had run out. In 1949, anti-communist fear, and fear of American traitors, was aggravated by the Chinese Communists winning the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led Nationalist government, government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the forces of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Armed conflict continued intermitt ...

against the Western-sponsored Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

, their founding of the Communist China, and later Chinese intervention (October–December 1950) in the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

(1950–1953) against U.S. ally South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

.

A few of the events during the Red Scare were also due to a power struggle between director of FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

and the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

. Hoover had instigated and aided some of the investigations of members of the CIA with "leftist" history, like Cord Meyer. This conflict could also be traced back to the conflict between Hoover and William J. Donovan

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat. He is best known for serving as the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to ...

, going back to the first Red Scare, but especially during World War II. Donovan ran the OSS (CIA's predecessor). They had differing opinions on the nature of the alliance with the Soviet Union, conflicts over jurisdiction, conflicts of personality, the OSS hiring of communists and criminals as agents, etc.

Historian Richard Powers distinguishes two main forms of anti-communism during the period, liberal anti-communism and countersubversive anti-communism. The countersubversives, he argues, derived from a pre-WWII isolationist tradition on the right. Liberal anti-communists believed that political debate was enough to show Communists as disloyal and irrelevant, while countersubversive anticommunists believed that Communists had to be exposed and punished. At times, countersubversive anticommunists accused liberals of being "equally destructive" as Communists due to an alleged lack of religious values or supposed "red web" infiltration into the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

.

Much evidence for Soviet espionage

The First Main Directorate () of the Committee for State Security under the USSR council of ministers (PGU KGB) was the organization responsible for foreign operations and intelligence activities by providing for the training and management of cove ...

existed, according to Democratic Senator and historian Daniel Moynihan, with the Venona project consisting of "overwhelming proof of the activities of Soviet spy networks in America, complete with names, dates, places, and deeds." However, Moynihan argued that because sources like the Venona project were kept secret for so long, "ignorant armies clashed by night". With McCarthy advocating an extremist view, the discussion of communist subversion was made into a civil rights issue instead of a counterintelligence one. This historiographical

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

perspective is shared by historians John Earl Haynes and Robert Louis Benson. While President Truman formulated the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

against Soviet expansion, it is possible he was not fully informed of the Venona intercepts, leaving him unaware of the domestic extent of espionage, according to Moynihan and Benson.

History

Early years

By the 1930s, communism had become an attractiveeconomic ideology

An economic ideology is a set of views forming the basis of an ideology on how the economy should run. It differentiates itself from economic theory in being Normative economics, normative rather than just explanatory in its approach, whereas the ...

, particularly among labor leaders and intellectuals. By 1939, the CPUSA had about 50,000 members. In 1940, soon after World War II began in Europe, the U.S. Congress legislated the Alien Registration Act (also known as the Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3rd session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of ...

, 18 USC § 2385) making it a crime to "knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the duty, necessity, desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association"—and required Federal registration of all foreign nationals. Although principally deployed against communists, the Smith Act was also used against right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

political threats such as the German-American Bund, and the perceived racial disloyalty of the Japanese-American population (''cf.'' hyphenated-Americans).

World War II

After the Soviet Union signed the non-aggression

After the Soviet Union signed the non-aggression Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

on August 23, 1939, negative attitudes towards communists in the United States were on the rise. While the American communist party at first attacked Germany for its September 1, 1939 invasion of western Poland, on September 11 it received a blunt directive from Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

denouncing the Polish government. On September 17, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland and occupied the Polish territory assigned to it by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland. The CPUSA turned the focus of its public activities from anti-fascism

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

to advocating peace, not only opposing military preparations, but also condemning those opposed to Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. The party did not at first attack President Roosevelt, reasoning that this could devastate American Communism, blaming instead Roosevelt's advisors.

On November 30, when Soviet Union attacked Finland and after forced mutual assistance pacts from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, the Communist Party considered Russian security sufficient justification to support the actions. Secret short wave radio broadcasts in October from Comintern leader Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; ) also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian communist politician who served as General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party from 1933 t ...

ordered CPUSA leader Earl Browder to change the party's support for Roosevelt. On October 23, the party began attacking Roosevelt. The party was active in the isolationist America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was an American isolationist pressure group against the United States' entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supporte ...

. The CPUSA also dropped its boycott of Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

goods, spread the slogans " The Yanks Are Not Coming" and "Hands Off", set up a "perpetual peace vigil" across the street from the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

and announced that Roosevelt was the head of the "war party of the American bourgeoisie". By April 1940, the party '' Daily Workers line seemed not so much antiwar as simply pro-German. A pamphlet stated the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

had just as much to fear from Britain and France as they did Germany. In August 1940, after NKVD agent Ramón Mercader killed Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

with an ice axe

An ice axe is a multi-purpose hiking and climbing tool used by mountaineers in both the ascent and descent of routes that involve snow or ice covered (e.g. ice climbing or mixed climbing) conditions. Its use depends on the terrain: in its si ...

, Browder perpetuated Moscow's fiction that the killer, who had been dating one of Trotsky's secretaries, was a disillusioned follower.

In allegiance to the Soviet Union, the party changed this policy again after Hitler broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact by attacking the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. The CPUSA opposed labor strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became co ...

s in the weapons industry and supporting the U.S. war effort against the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

. With the slogan "Communism is Twentieth-Century Americanism", the chairman, Earl Browder, advertised the CPUSA's integration to the political mainstream. In contrast, the Trotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

Socialist Workers Party opposed U.S. participation in the war and supported labor strikes, even in the war-effort industry. For this reason, James P. Cannon and other SWP leaders were convicted per the Smith Act.

Increasing tension

In March 1947, PresidentHarry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

signed Executive Order 9835

President Harry S. Truman signed United States Executive Order 9835, sometimes known as the "Loyalty Order", on March 21, 1947. The order established the first general loyalty program in the United States, designed to root out communist influence ...

, creating the " Federal Employees Loyalty Program" establishing political-loyalty review boards who determined the "Americanism" of Federal Government employees, and requiring that all federal employees to take an oath of loyalty to the United States government. It then recommended termination of those who had confessed to spying for the Soviet Union, as well as some suspected of being "Un-American". This led to more than 2,700 dismissals and 12,000 resignations from the years 1947 to 1956. It also was the template for several state legislatures' loyalty acts, such as California's Levering Act. The House Committee on Un-American Activities was created during the Truman administration as a response to allegations by Republicans of disloyalty in Truman's administration. The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and the committees of Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

( R., Wisc.) conducted character investigations of "American communists" (actual and alleged), and their roles in (real and imaginary) espionage, propaganda, and subversion favoring the Soviet Union—in the process revealing the extraordinary breadth of the Soviet spy network in infiltrating the federal government. The process also launched the successful political careers of Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

and Robert F. Kennedy, as well as that of Joseph McCarthy. The HUAC held a large interest in investigating those in the entertainment industry in Hollywood. They interrogated actors, writers, and producers. The people who cooperated in the investigations got to continue working as they had been, but people who refused to cooperate were blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list; if people are on a blacklist, then they are considere ...

ed. Critics of the HUAC claim their tactics were an abuse of government power and resulted in a witch hunt that disregarded citizens’ rights and ruined their careers and reputations. Critics claim the internal witch hunt was a use for personal gain to spread influence for government officials by intensifying the fear of Communists infiltrating the country. Supporters, however, believe the actions of the HUAC were justified given the level of threat Communism posed to democracy in the United States.

Senator McCarthy stirred up further fear in the United States of communists infiltrating the country by saying that communist spies were omnipresent, and he was America's only salvation, using this fear to increase his own influence. In 1950 Joseph McCarthy addressed the senate, citing 81 separate cases, and made accusations against suspected communists. Although he provided little or no evidence, this prompted the Senate to call for a full investigation.

Senator Pat McCarran ( D., Nev.) introduced the McCarran Internal Security Act

The Internal Security Act of 1950, (Public Law 81-831), also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, the McCarran Act after its principal sponsor Sen. Pat McCarran (D-Nevada), or the Concentration Camp Law, is a United States f ...

of 1950 that was passed by the U.S. Congress and which modified a great deal of law to restrict civil liberties in the name of security. President Truman declared the act a "mockery of the Bill of Rights" and a "long step toward totalitarianism" because it represented a government restriction on the freedom of opinion. He vetoed the act but his veto was overridden by Congress. Much of the bill eventually was repealed.

The formal establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 and the beginning of the Korean War in 1950 meant that Asian Americans

Asian Americans are Americans with Asian diaspora, ancestry from the continent of Asia (including naturalized Americans who are Immigration to the United States, immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of those immigrants).

A ...

, especially those of Chinese or Korean descent, came under increasing suspicion by both American civilians and government officials of being Communist sympathizers. Simultaneously, some American politicians saw the prospect of American-educated Chinese students bringing their knowledge back to "Red China" as an unacceptable threat to American national security, and laws such as the China Aid Act of 1950 and the Refugee Relief Act of 1953 gave significant assistance to Chinese students who wished to settle in the United States. Despite being naturalized, however, Chinese immigrants continued to face suspicion of their allegiance. The general effect, according to University of Wisconsin-Madison

A university () is an institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars". Uni ...

scholar Qing Liu, was to simultaneously demand that Chinese (and other Asian) students politically support the American government yet avoid engaging directly in politics.

The Second Red Scare profoundly altered the temper of American society. Its later characterizations may be seen as contributory to works of feared communist espionage, such as the film '' My Son John'' (1952), about parents' suspicions their son is a spy. Abundant accounts in narrative forms contained themes of the infiltration, subversion, invasion, and destruction of American society by un–American ''thought''. Even a baseball team, the Cincinnati Reds

The Cincinnati Reds are an American professional baseball team based in Cincinnati. The Reds compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (baseball), National League (NL) National League Central, Central Divisi ...

, temporarily renamed themselves the "Cincinnati Redlegs" to avoid the money-losing and career-ruining connotations inherent in being ball-playing "Reds" (communists). In 1954, Congress passed the Communist Control Act of 1954, which prevented members of the communist party in America from holding office in labor unions and other labor organizations.

Wind down

Examining the political controversies of the 1940s and 1950s, historian John Earl Haynes, who studied the Venona decryptions extensively, argued that Joseph McCarthy's attempts to "make anti-communism a partisan weapon" actually "threatened he post-Waranti-Communist consensus", thereby ultimately harming anti-communist efforts more than helping them. Meanwhile, the "shockingly high level" of infiltration by Soviet agents during WWII had largely dissipated by 1950. Liberal anti-communists likeEdward Shils

Edward Albert Shils (1 July 1910 – 23 January 1995) was a Distinguished Service Professor in the Committee on Social Thought and in Sociology at the University of Chicago and an influential sociologist. He was known for his research on the r ...

and Daniel Moynihan had contempt for McCarthyism, and Moynihan argued that McCarthy's overreaction distracted from the "real (but limited) extent of Soviet espionage in America." In 1950, President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

called Joseph McCarthy "the greatest asset the Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin (fortification), Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Mosco ...

has."

In 1954, after accusing the army, including war heroes, Senator Joseph McCarthy lost credibility in the eyes of the American public and the Army-McCarthy Hearings were held in the summer of 1954. He was formally censured by his colleagues in Congress and the hearings led by McCarthy came to a close. After the Senate formally censured McCarthy, his political standing and power were significantly diminished, and much of the tension surrounding the idea of a possible communist takeover died down.

From 1955 through 1959, the Supreme Court made several decisions which restricted the ways in which the government could enforce its anti-communist policies, some of which included limiting the federal loyalty program to only those who had access to sensitive information, allowing defendants to face their accusers, reducing the strength of congressional investigation committees, and weakening the Smith Act. In the 1957 case '' Yates v. United States'' and the 1961 case '' Scales v. United States'', the Supreme Court limited Congress's ability to circumvent the First Amendment, and in 1967 during the Supreme Court case '' United States v. Robel'', the Supreme Court ruled that a ban on communists in the defense industry was unconstitutional.

In 1995, the American government declassified details of the Venona Project following the Moynihan Commission, which when combined with the opening of the USSR

In 1954, after accusing the army, including war heroes, Senator Joseph McCarthy lost credibility in the eyes of the American public and the Army-McCarthy Hearings were held in the summer of 1954. He was formally censured by his colleagues in Congress and the hearings led by McCarthy came to a close. After the Senate formally censured McCarthy, his political standing and power were significantly diminished, and much of the tension surrounding the idea of a possible communist takeover died down.

From 1955 through 1959, the Supreme Court made several decisions which restricted the ways in which the government could enforce its anti-communist policies, some of which included limiting the federal loyalty program to only those who had access to sensitive information, allowing defendants to face their accusers, reducing the strength of congressional investigation committees, and weakening the Smith Act. In the 1957 case '' Yates v. United States'' and the 1961 case '' Scales v. United States'', the Supreme Court limited Congress's ability to circumvent the First Amendment, and in 1967 during the Supreme Court case '' United States v. Robel'', the Supreme Court ruled that a ban on communists in the defense industry was unconstitutional.

In 1995, the American government declassified details of the Venona Project following the Moynihan Commission, which when combined with the opening of the USSR Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

archives, provided substantial validation of intelligence gathering, outright spying, and policy influencing, by Americans on behalf of the Soviet Union, from 1940 through 1980. Over 300 American communists, whether they knew it or not, including government officials and technicians that helped in developing the atom bomb, were found to have engaged in espionage. This allegedly included some pro-Soviet capitalists, such as economist Harry Dexter White

Harry Dexter White (October 29, 1892 – August 16, 1948) was an American government official in the United States Department of the Treasury. Working closely with the secretary of the treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., he helped set American financia ...

, and communist businessman David Karr

David Harold Karr, born David Katz (1918, Brooklyn, New York – 7 July 1979, Paris) was a controversial American journalist, businessman, Communist and NKVD agent.

Early life

He was born into a Jewish family. Enthralled with the radical left ...

.

New Red Scare

According to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

's growing military and economic power has resulted in a "New Red Scare" in the United States. Both Democrats and Republicans have expressed anti-China sentiment. According to ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'', the New Red Scare has caused the American and Chinese governments to "increasingly view Chinese students with suspicion" on American college campuses.

The fourth iteration of the Committee on the Present Danger, a United States foreign policy interest group, was established on March 25, 2019, branding itself Committee on the Present Danger: China (CPDC). The CPDC has been criticized as promoting a revival of Red Scare politics in the United States, and for its ties to conspiracy theorist Frank Gaffney and conservative activist Steve Bannon

Stephen Kevin Bannon (born November 27, 1953) is an American media executive, political strategist, and former investment banker. He served as the White House's chief strategist for the first seven months of president Donald Trump's first ...

. David Skidmore, writing for '' The Diplomat'', saw it as another instance of "adolescent hysteria" in American diplomacy, as another of the "fevered crusades hich

Ij () is a village in Golabar Rural District of the Central District in Ijrud County, Zanjan province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq ...

have produced some of the costliest mistakes in American foreign policy". Between 2000 and 2023, there were 224 reported instances of Chinese espionage directed at the United States.

Outside the United States

The American Red Scares, combined with the general atmosphere of the Cold War, had a marked influence on other Anglophone countries. Anticommunist paranoia occurred in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. In other parts of the world, such asIndonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, fear and loathing of communism has escalated to the level of political violence

Political violence is violence which is perpetrated in order to achieve political goals. It can include violence which is used by a State (polity), state against other states (war), violence which is used by a state against civilians and non-st ...

.

See also

* American social policy during the Second Red Scare * China threat theory *Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

* Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

* ''The Crucible

''The Crucible'' is a 1953 play by the American playwright Arthur Miller. It is a dramatized and partially fictionalized story of the Salem witch trials that took place in the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1692 to 1693. Miller wrote ...

''

* Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code ( ...

* Eugene Debs and '' Debs v. United States''

* Fear mongering

Fearmongering, or scaremongering, is the act of exploiting feelings of fear by using exaggerated rumors of impending danger, usually for personal gain.

Theory

According to evolutionary anthropology and evolutionary biology, humans have a strong ...

* Foley Square trial

* History of Soviet espionage in the United States

* Hollywood blacklist

The Hollywood blacklist was the mid-20th century banning of suspected Communists from working in the United States entertainment industry. The blacklisting, blacklist began at the onset of the Cold War and Red Scare#Second Red Scare (1947–1957 ...

* Jencks Act

In the United States, the Jencks Act () requires the prosecutor to produce a verbatim statement or report made by a government witness or prospective government witness (other than the defendant), but only before cross or adverse examination.

Jen ...

* '' Jencks v. United States''

* Kellock–Taschereau Commission

* Lavender scare

*McCarthyism

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a Fear mongering, campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage i ...

* Moral panic

A moral panic is a widespread feeling of fear that some evil person or thing threatens the values, interests, or well-being of a community or society. It is "the process of arousing social concern over an issue", usually perpetuated by moral e ...

* Pentagon military analyst program

* Propaganda in the United States

* Psychological operations (United States)

* The Reagan Doctrine

* The Red Decade

* Red-tagging in the Philippines

In the Philippines, red-tagging is the labeling of individuals or organizations as Communism in the Philippines, communists, subversives, or Terrorism in the Philippines, terrorists, regardless of their actual political beliefs or affiliations. It ...

* '' Rooi gevaar'' ("red danger" in Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

)

* Subversive Activities Control Board

* Tankie

* '' Terruqueo''

* US intervention in Latin America

* White Terror (Taiwan)

* Witch-hunt

A witch hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or Incantation, incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the ...

* Yellow Peril

References

Further reading

* K. A. Cuordileone, "The Torment of Secrecy: Reckoning with Communism and Anti-Communism After Venona", '' Diplomatic History'', vol. 35, no. 4 (Sept. 2011), pp. 615–642. * Albert Fried, ''McCarthyism, the Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997 * Joy Hakim, ''War, Peace, and All That Jazz''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. * John Earl Haynes, ''Red Scare or Red Menace?: American Communism and Anti Communism in the Cold War Era''. Ivan R. Dee, 2000. * John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, ''Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America''. Cambridge, MA: Yale University Press, 2000. * Murray B. Levin, ''Political Hysteria in America: The Democratic Capacity for Repression''. New York: Basic Books, 1972. * Rodger McDaniel, ''Dying for Joe McCarthy's Sins''. Cody, Wyo.: WordsWorth, 2013. * Ted Morgan, ''Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-Century America''. New York: Random House, 2004. * * Richard Gid Powers, ''Not Without Honor: A History of American Anti-Communism''. New York: Free Press, 1997. * * Ellen Schrecker, ''Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998. * Landon R. Y. Storrs, ''The Second Red Scare and the Unmaking of the New Deal Left''. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012. * William M. Wiecek, "The Legal Foundations of Domestic Anticommunism: The Background of ''Dennis v. United States'', ''Supreme Court Review'', vol. 2001 (2001), pp. 375–434. .External links

"Political Tests for Professors: Academic Freedom during the McCarthy Years"

by Ellen Schrecker, The University Loyalty Oath, October 7, 1999. {{DEFAULTSORT:Red Scare Aftermath of World War II in the United States Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States Anti-communism in Australia Anti-communism in Canada Anti-communism in the Philippines Anti-communism in the United Kingdom Anti-communism in the United States Anti-Russian sentiment China–United States relations Communism in the United States Conspiracy theories involving communism Far-left politics in the United States History of the Communist Party USA History of the Industrial Workers of the World History of the Socialist Party of America Political and cultural purges Political history of the United States Political repression in the Philippines Political repression in the United Kingdom Political repression in the United States Russia–United States relations Scares Socialism in the United States Soviet Union–United States relations Counter-revolution