Ray Strachey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ray Strachey (born Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe; 4 June 188716 July 1940) was a British feminist politician, artist and writer.

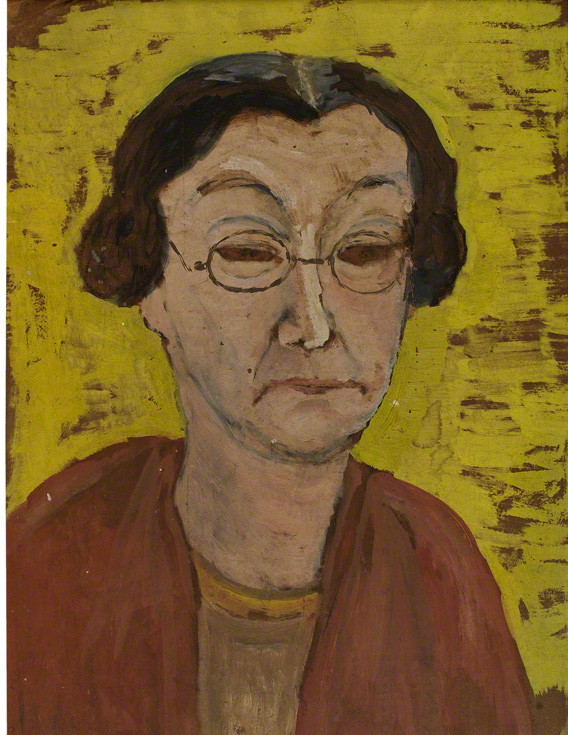

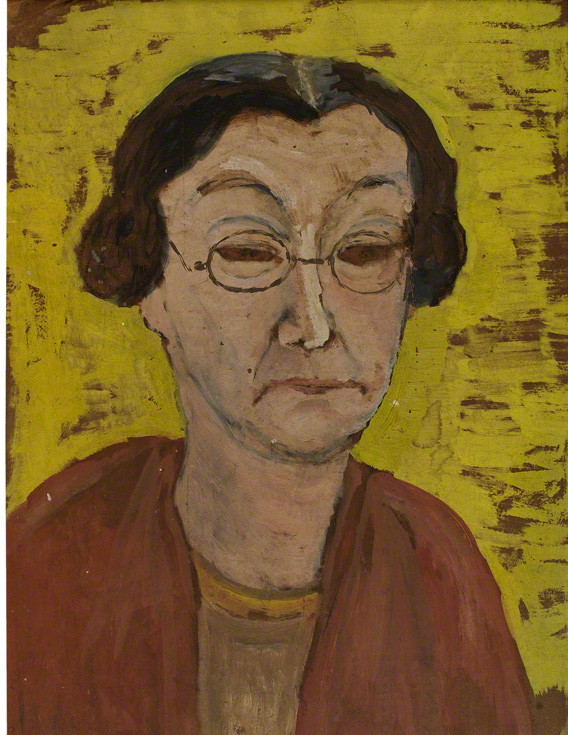

Strachey painted her sister-in-law, Pernel Strachey, around the year 1930, and the young Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, Dadie Rylands at about the same time. Both paintings are in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Strachey painted her sister-in-law, Pernel Strachey, around the year 1930, and the young Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, Dadie Rylands at about the same time. Both paintings are in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Ray Strachey, The Women's Library at London Metropolitan University

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Strachey, Ray 1887 births 1940 deaths 20th-century British novelists 20th-century British women writers Alumni of Newnham College, Cambridge British feminist writers British suffragists British women novelists Independent British political candidates Strachey family Writers from London

Early life

Her father was Irish barrister Benjamin "Frank" Conn Costelloe, and her mother was art historian Mary Berenson. She was the elder of the two girls in her family. Her younger sister was the psychologist Karin Stephen, née Costelloe, who married Adrian Stephen,Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer and one of the most influential 20th-century modernist authors. She helped to pioneer the use of stream of consciousness narration as a literary device.

Vir ...

's younger brother, in 1914. Ray was educated at Kensington high school and at Newnham College, Cambridge

Newnham College is a women's constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college was founded in 1871 by a group organising Lectures for Ladies, members of which included philosopher Henry Sidgwick and suffragist campaigner Millicen ...

, where she achieved third class in part one of the mathematical tripos

The Mathematical Tripos is the mathematics course that is taught in the Faculty of Mathematics, University of Cambridge, Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge.

Origin

In its classical nineteenth-century form, the tripos was a di ...

(1908).

Like some other female Mathematics graduates of the time, such as Margaret Dorothea Rowbotham

Margaret Dorothea Rowbotham (19 June 1883 – 23 February 1978) was an engineer, a campaigner for women's employment rights and a founder member of the Women's Engineering Society.

Early life and education

Born on 19 June 1883 at 6 Park Villas, ...

and Margaret Partridge, Strachey developed an interest in engineering. She was discouraged by her mother Mary Berensen but nevertheless she took an electrical engineering class at Oxford University in 1910 and planned to study electrical engineering at the Technical College of the City and Guilds of London Institute

The City and Guilds of London Institute is an educational organisation in the United Kingdom. Founded on 11 November 1878 by the City of London and 16 livery companies to develop a national system of technical education, the institute has be ...

in October 1910. She wrote to her aunt "I have decided to go to London next winter for my engineering" and that she had been encouraged and helped by Hertha Ayrton. She abandoned her plan due to marriage, but maintained her involvement with the Society of Women Welders which she had helped to found.

Career

For most of her life, Strachey worked forwomen's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

organisations, starting when she was studying at Cambridge, when she joined what became known as the Mud March in February 1907 and addressing meetings in summer 1907. She took part in the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) Caravan tour in July 1908. The caravan tour was organised by Newnham College students that began in Scotland. The caravan was pulled by a horse and driven by a man. The caravan travelled from place to place and the caravan would by redirected to good places to stay by outriders on bicycles. The caravan had campbeds and a tent that allowed five or six to sleep. They toured into Keswick and the north of England and they would give talks about women's suffrage. The caravan visited Oxford, Stratford and Warwick. They argued the case for women to get the vote, but they avoided talking about their ambitions of getting women to be members of parliament as this was too radical. The women on the caravan included Strachey and EM Gardner. The tour finished in the East Midlands at Derby where they attracted a crowd on 1,000 people.

Most of Strachey's publications are non-fiction and deal with suffrage issues. She is most often remembered for her book ''The Cause'' (1928). Her papers are held at The Women's Library

The Women's Library is England's main library and museum resource on women and the women's movement, concentrating on Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries. It has an institutional history as a coherent collection dating back to the mid-1920s, ...

at the London School of Economics.

Strachey worked closely with Millicent Fawcett, sharing her Liberal feminist values and opposing any attempt to integrate the suffrage movement with the Labour Party. In 1915 she became parliamentary secretary of the NUWSS, serving in this role until 1920.

Strachey took great interest in the employment of women in engineering occupations. In 1919 women found themselves excluded by law from most jobs in the engineering industry under the Restoration of Pre-War Practices Act 1919. Strachey campaigned on behalf of the Society of Women Welders in 1920 for women to remain in the trade. In 1922 Strachey also created a company to build small mud houses to help the housing shortage, based on a 1922 prototype known as "Copse Cottage" (but referred to as "Mud House". Women were employed to assemble them but there were problems with sourcing the correct clay and the chimney builders refused to co-operate. The Mavat company did exhibit a bungalow in 1925 at the Women's Arts & Crafts Exhibition at Central Hall in London. Strachey was defeated but she found work for all the women involved.

In her book Women's Suffrage and Women's Service she described the setting up by the London Society for Women's Service of a school for Oxy-Acetylene Welding. In 1937 she wrote about women's employment in professional and trade roles in Careers and Openings for Women.

After the Great War, when some women were granted the vote, and women could stand for parliament, she stood as an Independent parliamentary candidate at Brentford and Chiswick on the general elections in 1918, 1922 and 1923, without success. She rejected the attempt by Eleanor Rathbone to establish a broad-based feminist programme in the 1920s. In 1931 she became parliamentary secretary to Britain's first woman MP to take her seat, Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor

Nancy Witcher Astor, Viscountess Astor (19 May 1879 – 2 May 1964) was an American-born British politician who was the first woman seated as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP), serving from 1919 to 1945. Astor w ...

, and in 1935 Strachey became the head of the Women's Employment Federation. She also made regular radio broadcasts for the BBC.

Family

She married at Cambridge on 31 May 1911 the civil servantOliver Strachey

Oliver Strachey CBE (3 November 1874 – 14 May 1960), a British civil servant in the Foreign Office, was a cryptographer from World War I to World War II.

Life and work

Strachey was a son of Sir Richard Strachey, colonial administrator and J ...

, with whom she had two children, Barbara (born 1912, later a writer) and Christopher

Christopher is the English language, English version of a Europe-wide name derived from the Greek language, Greek name Χριστόφορος (''Christophoros'' or ''Christoforos''). The constituent parts are Χριστός (''Christós''), "Jesus ...

(born 1916, later a pioneer computer scientist). Oliver Strachey was the elder brother of the biographer Lytton Strachey

Giles Lytton Strachey (; 1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was an English writer and critic. A founding member of the Bloomsbury Group and author of ''Eminent Victorians'', he established a new form of biography in which psychology, psychologic ...

of the Bloomsbury group

The Bloomsbury Group was a group of associated British writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the early 20th century. Among the people involved in the group were Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Vanessa Bell, a ...

; other siblings in the Strachey family included psychoanalyst James Strachey

James Beaumont Strachey (; 26 September 1887, London25 April 1967, High Wycombe) of the Strachey family was a British psychoanalyst, and, with his wife Alix, translator of Sigmund Freud into English. He is perhaps best known as the general ed ...

, novelist Dorothy Bussy

Dorothy Bussy ( Strachey; 24 July 1865 – 1 May 1960) was an English novelist and translator, close to the Bloomsbury Group.

Family background and childhood

Dorothy Bussy was a member of the Strachey family. Her mother was suffragist J ...

, and educationist Pernel Strachey. Ray's mother-in-law was Jane Maria Strachey, a well-known author and supporter of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

who co-led the suffragist Mud March of 1907 in London. Her sister-in-law was the British suffragist, Pippa Strachey.

Strachey's daughter, Barbara, was interviewed about her mother and the wider Strachey family by the historian, Brian Harrison, as part of his Suffrage Interviews project, titled ''Oral evidence on the suffragette and suffragist movements: the Brian Harrison interviews.'' There is a 3 part interview from January 1977 and a single interview from August 1979. The interviews include reflections on their home, Mud House, and on Ray's relationships with her husband, mother and sister-in-law, Pippa.

Ray and Oliver's niece, Ursula Margaret Wentzel, née Strachey (Ursula's Father, Ralph, was Oliver's brother) was interviewed about Ray (and Pippa) in March 1977 and talks about Ray's Marsham Street home and her practical skills.

Art

Strachey painted her sister-in-law, Pernel Strachey, around the year 1930, and the young Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, Dadie Rylands at about the same time. Both paintings are in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Strachey painted her sister-in-law, Pernel Strachey, around the year 1930, and the young Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, Dadie Rylands at about the same time. Both paintings are in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Death

She died in the Royal Free Hospital in London in her early fifties ofheart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome caused by an impairment in the heart's ability to Cardiac cycle, fill with and pump blood.

Although symptoms vary based on which side of the heart is affected, HF ...

, following an operation to remove a fibroid tumor.

Posthumous recognition

Her name and picture (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are on theplinth

A pedestal or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In civil engineering, it is also called ''basement''. The minimum height o ...

of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in April 2018.

Publications

*''The World at Eighteen'' *''Marching On'' *''Shaken By The Wind''Biographies

*'' Frances Willard: Her Life and Work'' (1913) *''A Quaker Grandmother: Hannah Whitall Smith'' (1914) *'' Millicent Garrett Fawcett'' (1931)Non-fiction about women's roles

*''Women's suffrage and women's service: The history of the London and National Society for Women's Service'' (1927) *''The Cause: a Short History of Women's Movement in Great Britain'' *''Careers and Openings for Women'' *''Our Freedom and Its Results''References

External links

* *Ray Strachey, The Women's Library at London Metropolitan University

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Strachey, Ray 1887 births 1940 deaths 20th-century British novelists 20th-century British women writers Alumni of Newnham College, Cambridge British feminist writers British suffragists British women novelists Independent British political candidates Strachey family Writers from London