Provveditore generale di Candia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Realm or Kingdom of Candia ( Venetian: ''Regno de Cû ndia'') or Duchy of Candia (

Following the reconquest of Constantinople in 1261, and the restoration of the

Following the reconquest of Constantinople in 1261, and the restoration of the

Venice tried to negotiate with the rebels, but after this effort failed, it began assembling a large expeditionary force to recover the island by force. The army was headed by the Veronese mercenary captain Lucino dal Verme and the fleet by Domenico Michiele. Once news of this arrived in Crete, many of the rebels began wavering. When the Venetian fleet arrived on 7 May 1364, resistance collapsed quickly. Candia surrendered on 9 May, and most of the other cities followed. Nevertheless, on strict orders from the Venetian government, the Venetian commanders launched a purge of the rebel leadership, including the execution and proscription of the ringleaders, and the disbandment of the Gradenigo and Venier families, who were banished from all Venetian territories. The feudal charter of 1211 was revoked, and all noble families obliged to swear an oath of allegiance to Venice. 10 May was declared a local holiday in Candia, and celebrated with extravagant festivals.

Venice tried to negotiate with the rebels, but after this effort failed, it began assembling a large expeditionary force to recover the island by force. The army was headed by the Veronese mercenary captain Lucino dal Verme and the fleet by Domenico Michiele. Once news of this arrived in Crete, many of the rebels began wavering. When the Venetian fleet arrived on 7 May 1364, resistance collapsed quickly. Candia surrendered on 9 May, and most of the other cities followed. Nevertheless, on strict orders from the Venetian government, the Venetian commanders launched a purge of the rebel leadership, including the execution and proscription of the ringleaders, and the disbandment of the Gradenigo and Venier families, who were banished from all Venetian territories. The feudal charter of 1211 was revoked, and all noble families obliged to swear an oath of allegiance to Venice. 10 May was declared a local holiday in Candia, and celebrated with extravagant festivals.

Crete had always been of particular importance among Venice's colonies, but its importance increased as the Ottomans started wresting away Venice's overseas possessions in a series of conflicts that began after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. By the middle of the 16th century, Crete was the only major Venetian possession left in the Aegean, and following the loss of Cyprus in 1570ã1571, in the entire Eastern Mediterranean. The emergence of the Ottoman threat coincided with a period of economic decline for the Venetian Republic, which hampered its ability to effectively strengthen Crete. In addition, internal strife on the island, and the local aristocracy's resistance to reforms, compounded the problem.

The Fall of Constantinople caused a deep impression among the Cretans, and in its aftermath, a series of anti-Venetian conspiracies took place. The first was the

Crete had always been of particular importance among Venice's colonies, but its importance increased as the Ottomans started wresting away Venice's overseas possessions in a series of conflicts that began after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. By the middle of the 16th century, Crete was the only major Venetian possession left in the Aegean, and following the loss of Cyprus in 1570ã1571, in the entire Eastern Mediterranean. The emergence of the Ottoman threat coincided with a period of economic decline for the Venetian Republic, which hampered its ability to effectively strengthen Crete. In addition, internal strife on the island, and the local aristocracy's resistance to reforms, compounded the problem.

The Fall of Constantinople caused a deep impression among the Cretans, and in its aftermath, a series of anti-Venetian conspiracies took place. The first was the

The conquest of Crete brought Venice its first major colony; indeed, the island would remain the largest possession of the Republic until its expansion into the northern Italian mainland (the '' Terraferma'') in the early 15th century. In addition to the unfamiliar challenges of governing a territory of such size and eminence, the distance of Crete from the metropolisãabout a month's journey by galleyãraised dangers and complications. As a result, unlike other colonies, where the Venetian government was content to allow governance by the local Venetian colonists, in Crete the Republic employed salaried officials dispatched from the metropolis. This "made subjects of both the Venetian colonizers and the colonized Greek people of the island", and despite the privileges accorded to the former, their common position of subservience to the metropolis made it more likely for the Venetians and Greeks of Crete to rally together in support of common interests against the metropolitan authorities.

The conquest of Crete brought Venice its first major colony; indeed, the island would remain the largest possession of the Republic until its expansion into the northern Italian mainland (the '' Terraferma'') in the early 15th century. In addition to the unfamiliar challenges of governing a territory of such size and eminence, the distance of Crete from the metropolisãabout a month's journey by galleyãraised dangers and complications. As a result, unlike other colonies, where the Venetian government was content to allow governance by the local Venetian colonists, in Crete the Republic employed salaried officials dispatched from the metropolis. This "made subjects of both the Venetian colonizers and the colonized Greek people of the island", and despite the privileges accorded to the former, their common position of subservience to the metropolis made it more likely for the Venetians and Greeks of Crete to rally together in support of common interests against the metropolitan authorities.

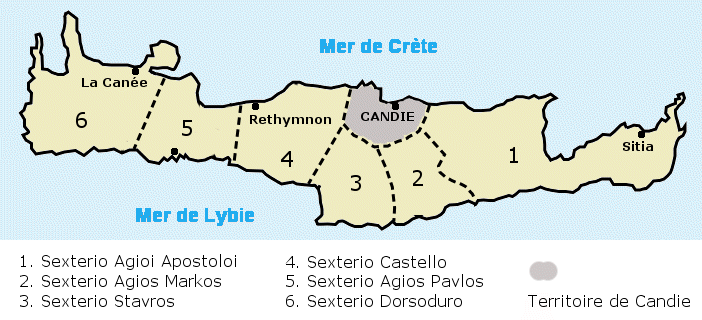

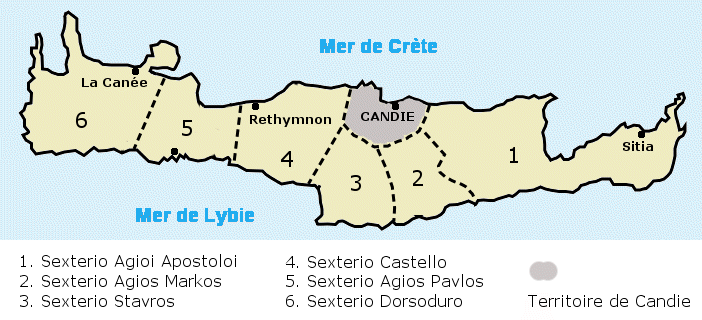

From the early 14th century on, the island was divided into four larger provinces (''territoria''):

* ''Territorio'' of ''Candia'', by far the largest in area, roughly equivalent to the modern Heraklion Prefecture along with the Lasithi plateau and Mirabello Province

* ''Territorio'' of Rethymno (Ven. Rettimo), roughly coterminous with the modern Rethymno Prefecture

* ''Territorio'' of Chania (Ven. Canea), roughly coterminous with the modern provinces of

From the early 14th century on, the island was divided into four larger provinces (''territoria''):

* ''Territorio'' of ''Candia'', by far the largest in area, roughly equivalent to the modern Heraklion Prefecture along with the Lasithi plateau and Mirabello Province

* ''Territorio'' of Rethymno (Ven. Rettimo), roughly coterminous with the modern Rethymno Prefecture

* ''Territorio'' of Chania (Ven. Canea), roughly coterminous with the modern provinces of

Regno di Candia

map by Marco Boschini

Byzantine & Christian Museum.gr: "Society and art in Venetian Crete"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kingdom of Candia History of Crete Stato da Mû r 1205 establishments in Europe 13th-century establishments in the Republic of Venice 1669 disestablishments in the Republic of Venice States and territories established in 1205 States and territories disestablished in the 1660s

Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697ã1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

: ''Dogado de Cû ndia'' ) was the official name of Crete

Crete ( el, öüöÛüöñ, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

during the island's period as an overseas colony of the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repû¿blega de Venû´sia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repû¿blega Vû´neta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenû˜sima Repû¿blega de Venû´sia ...

, from the initial Venetian conquest in 1205ã1212 to its fall to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Åö¡üö¥öÝö§ö¿ö¤öÛ öü

üö¢ö¤üöÝüö¢üö₤öÝ, Othémaniká Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

during the Cretan War (1645ã1669)

The Cretan War ( el, öüöñüö¿ö¤üü ö üö£öçö¥ö¢ü, tr, Girit'in Fethi), also known as the War of Candia ( it, Guerra di Candia) or the Fifth OttomanãVenetian War, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies (chief among ...

. The island was at the time and up to the early modern era commonly known as Candia after its capital, Candia or Chandax (modern Heraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, öüö˜ö¤ö£öçö¿ö¢, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital city, capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion (regional unit), Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Gree ...

). In modern Greek historiography, the period is known as the Venetocracy ( el, ööçö§öçüö¢ö¤üöÝüö₤öÝ, ''Venetokratia'' or öö§öçüö¢ö¤üöÝüö₤öÝ, ''Enetokratia'').

The island of Crete had formed part of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

until 1204, when the Fourth Crusade dissolved the empire and divided its territories amongst the crusader leaders (see Frankokratia). Crete was initially allotted to Boniface of Montferrat, but, unable to enforce his control over the island, he soon sold his rights to Venice. Venetian troops first occupied the island in 1205, but it took until 1212 for it to be secured, especially against the opposition of Venice's rival Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zûˆna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

. Thereafter, the new colony took shape: the island was divided into six provinces ('' sestieri'') named after the divisions of the city of Venice itself, while the capital Candia was directly subjected to the '' Commune Veneciarum''. The islands of Tinos and Cythera, also under Venetian control, came under the kingdom's purview. In the early 14th century, this division was replaced by four provinces, almost identical to the four modern prefectures.

During the first two centuries of Venetian rule, revolts by the native Orthodox Greek population against the Roman Catholic Venetians were frequent, often supported by the Empire of Nicaea. Fourteen revolts are counted between 1207 and the last major uprising, the Revolt of St. Titus in the 1360s, which united the Greeks and the Venetian ''coloni'' against the financial exactions of the metropolis. Thereafter, and despite occasional revolts and Turkish raids, the island largely prospered, and Venetian rule opened up a window into the ongoing Italian Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

. As a consequence, an artistic and literary revival unparalleled elsewhere in the Greek world took place: the Cretan School of painting, which culminated in the works of El Greco, united Italian and Byzantine forms, and a widespread literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

using the local idiom emerged, culminating with the early 17th-century romances '' Erotokritos'' and '' Erophile''.

After the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus in 1571, Crete was Venice's last major overseas possession. The Republic's relative military weakness, coupled with the island's wealth and its strategic location controlling the waterways of the Eastern Mediterranean attracted the attention of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Åö¡üö¥öÝö§ö¿ö¤öÛ öü

üö¢ö¤üöÝüö¢üö₤öÝ, Othémaniká Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. In the long and devastating Cretan War (1645ã1669)

The Cretan War ( el, öüöñüö¿ö¤üü ö üö£öçö¥ö¢ü, tr, Girit'in Fethi), also known as the War of Candia ( it, Guerra di Candia) or the Fifth OttomanãVenetian War, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies (chief among ...

, the two states fought over the possession of Crete: the Ottomans quickly overran most of the island, but failed to take Candia, which held out, aided by Venetian naval superiority and Ottoman distractions elsewhere, until 1669. Only the three island fortresses of Souda, Gramvousa and Spinalonga remained in Venetian hands. Attempts to recover Candia during the Morean War

The Morean War ( it, Guerra di Morea), also known as the Sixth OttomanãVenetian War, was fought between 1684ã1699 as part of the wider conflict known as the " Great Turkish War", between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Militar ...

failed, and these last Venetian outposts were finally taken by the Turks in 1715, during the last OttomanãVenetian War.

History

Establishment

Venetian conquest of Crete

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

had a long history of trade contact with Crete

Crete ( el, öüöÛüöñ, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

; the island was one of the numerous cities and islands throughout Greece where the Venetians had enjoyed tax-exempted trade by virtue of repeated imperial chrysobull

A golden bull or chrysobull was a decree issued by Byzantine Emperors and later by monarchs in Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, most notably by the Holy Roman Emperors. The term was originally coined for the golden seal (a '' bul ...

s, beginning in 1147 (and in turn codifying a practice dating to ) and confirmed as late as 1198 in a treaty with Alexios III Angelos

Alexios III Angelos ( gkm, Ã¥ö£öÙöƒö¿ö¢ü öö¢ö¥ö§öñö§üü Ã¥ö°ö°öçö£ö¢ü, Alexios Komnános Angelos; 1211), Latinized as Alexius III Angelus, was Byzantine Emperor from March 1195 to 17/18 July 1203. He reigned under the name Alexios Komnen ...

. These same locations were largely allocated to the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repû¿blega de Venû´sia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repû¿blega Vû´neta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenû˜sima Repû¿blega de Venû´sia ...

in the partition of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

that followed the capture of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

by the Fourth Crusade, in April 1204: in addition to the Ionian Islands, the Saronic Gulf

The Saronic Gulf ( Greek: öÈöÝüüö§ö¿ö¤üü ö¤üö£üö¢ü, ''Saronikû°s kû°lpos'') or Gulf of Aegina in Greece is formed between the peninsulas of Attica and Argolis and forms part of the Aegean Sea. It defines the eastern side of the isthmus of ...

islands and the Cyclades, she obtained several coastal outposts on the Greek mainland of interest as bases for her maritime commerce. Finally, on 12 August 1204, the Venetians preempted their traditional rivals, the Genoese, to acquire Crete from Boniface of Montferrat. Boniface had allegedly been promised the island by Alexios IV Angelos, but as he had little use for it, he sold it in exchange for 1,000 silver marks, an annual portion of the island's revenues totalling 10,000 ''hyperpyra

The ''hyperpyron'' ( ''nû°misma hypûˋrpyron'') was a Byzantine coin in use during the late Middle Ages, replacing the ''solidus'' as the Byzantine Empire's gold coinage.

History

The traditional gold currency of the Byzantine Empire had been the '' ...

'', and the promise of Venetian support for his acquisition of the Kingdom of Thessalonica. Venice's gains were formalized in the '' Partitio Romaniae'' a few weeks later.

To enforce their claim, the Venetians landed a small force on the offshore island of Spinalonga. The Genoese however, who already had a colony on Crete, moved more quickly: under the command of Enrico Pescatore, Count of Malta, and enjoying the support of the local populace, they soon became masters over the eastern and central portions of the island. A first Venetian attack in summer 1207 under Ranieri Dandolo and Ruggiero Premarino was driven off, and for the next two years, Pescatore ruled the entire island with the exception of a few isolated Venetian garrisons. Pescatore even appealed to the Pope, and attempted to have himself confirmed as the island's king. However, while Venice was determined to capture the island, Pescatore was largely left unsupported by Genoa. In 1209, the Venetians managed to capture Palaiokastro near Candia (Greek Chandax, öÏö˜ö§öÇöÝöƒ; modern Heraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, öüö˜ö¤ö£öçö¿ö¢, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital city, capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion (regional unit), Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Gree ...

, öüö˜ö¤ö£öçö¿ö¢ö§), but it took them until 1212 to evict Pescatore from the island, and the latter's lieutenant, Alamanno da Costa Alamanno da Costa (active 1193ã1224, died before 1229) was a Genoese admiral. He became the count of Syracuse in the Kingdom of Sicily, and led naval expeditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. He was an important figure in Genoa's longstan ...

, held out even longer. Only on 11 May 1217 did the war with Genoa end in a treaty that left Crete securely in Venetian hands.

Organization of the Venetian colony

Giacomo Tiepolo became the first governor of the new province, with the title of "duke of Crete" (), based in Candia. To strengthen Venetian control over Crete, Tiepolo suggested the dispatch of colonists from the metropolis; the Venetian colonists would receive land, and in exchange provide military service. The suggestion was approved, and the relevant charter, the , proclaimed on 10 September 1211 at Venice. 132 nobles, who were to serve as knights (''milites'' or ''cavaleri'') and 45 burghers (''pedites'', ''sergentes'') participated in the first colonization wave that left Venice on 20 March 1212. Three more waves of colonists were sent, in 1222, 1233, and 1252, and immigration continued in a more irregular fashion in later years as well. In total, about 10,000 Venetians are estimated to have moved to Crete during the first century of Venetian ruleãby comparison, Venice itself had a population of at this period. The colonization wave of 1252 also resulted in the establishment of Canea (modern Chania), on the site of the long abandoned ancient city of Kydonia. Venetians used Crete as a center for their profitable eastern trade. Furthermore, they established a feudal state and administered a strict capitalist system for exploiting the island's agricultural produce. Exported products consisted primarily of wheat and sweet wine (malmsey

Malvasia (, also known as Malvazia) is a group of wine grape varieties grown historically in the Mediterranean region, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands and the island of Madeira, but now grown in many of the winemaking regions of the world. I ...

), and to a lesser extent of timber and cheese.

Age of the Cretan rebellions, 13thã14th centuries

Venetian rule over Crete proved troubled from the beginning, as it encountered the hostility of the local populace. In the words of the medievalist Kenneth Setton, it required "an unceasing vigilance and a large investment in men and money to hold on to the island". No fewer than 27 large and small uprisings or conspiracies are documented during Venetian rule. Although the local Greeks, both the noble families and the wider populace, were allowed to keep their own law and property, they resented Latin rule and the strict discrimination between them and the Latin Venetian elite, which monopolized the higher administrative and military posts of the island and reaped most of the benefits of the commerce passing through it. During the early period of Venetian rule, the Venetian colonists consciously maintained themselves apart; until the end of the 13th century, even mixed marriages between native Cretans and Venetians were prohibited.First uprisings

Already in 1212, the Hagiostephanites brothers rose in revolt in theLasithi Plateau

The Lasithi Plateau ( el, öüö¢üöÙöÇö¿ö¢ ööÝüö¿ö¡ö₤ö¢ü

, ''Oropedio Lasithiou''), sometimes spelt Lassithi Plateau, is a high endorheic plateau, located in the Lasithi regional unit in eastern Crete, Greece. Since the 1997 Kapodistrias ref ...

, possibly caused by the arrival of the first Venetian colonists, and the expropriation of the Cretan nobles and the Orthodox Church on the island. The rebellion soon spread throughout the eastern part of Crete, capturing the forts of Sitia and Spinalonga, and was only suppressed through the intervention of Marco I Sanudo

Marco Sanudo (c. 1153 ã between 1220 and 1230, most probably 1227) was the creator and first Duke of the Duchy of the Archipelago, after the Fourth Crusade.

Maternal nephew of Venetian doge Enrico Dandolo, he was a participant in the Fourth Cru ...

, the Duke of Naxos

The Duchy of the Archipelago ( el, öö¢ü

ö¤ö˜üö¢ üö¢ü

öüüö¿üöçö£ö˜ö°ö¢ü

ü, it, Ducato dell'arcipelago), also known as Duchy of Naxos or Duchy of the Aegean, was a maritime state created by Venetian interests in the Cyclades archipelago i ...

. Sanudo and Tiepolo then fell out, and Sanudo attempted to conquer the island for himself. Sanudo enjoyed considerable local support, including the powerful archon Sebastos Skordiles. He even seized Candia, while Tiepolo escaped to the nearby fortress of Temenos disguised as a woman. The arrival of a Venetian fleet allowed Tiepolo to recover the capital, and Sanudo agreed to evacuate the island in exchange for money and provisions; twenty Greek lords who had collaborated with him accompanied him to Naxos.

The failure of this first revolt did not reduce Cretan restiveness, however. In 1217, the theft of some horses and pasture land belonging to the Skordiles family by the Venetian rector of Monopari (Venetian Bonrepare), and the failure of the Duke of Crete, Paolo Querini, to provide redress, resulted in the outbreak of a major rebellion, led by the Greek nobles Constantine Skordiles and Michael Melissenos. Based in the two mountainous provinces of Upper Syvritos and Lower Syvritos, the rebels inflicted successive defeats on the Venetian troops, and the uprising soon spread across the entire western part of the island. As force proved unable to quell the rebellion, the Venetians resorted to negotiations. On 13 September 1219, the Duke of Crete, Domenico Delfino, and the rebel leaders concluded a treaty that gave the latter knightly fiefs and various privileges. 75 serfs were set free, the privileges of the metochi of the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian on Patmos

Patmos ( el, ö ö˜üö¥ö¢ü, ) is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. It is famous as the location where John of Patmos received the visions found in the Book of Revelation of the New Testament, and where the book was written.

One of the norther ...

were confirmed, and Venetian citizens became liable for punishment for crimes against the Cretan commoners (''villani''). In exchange, the Cretan nobles swore allegiance to the Republic of Venice. This treaty had major repercussions, as it began the formation of a native Cretan noble class, set on equal footing with the Venetian colonial aristocracy. However, the arrival of the second wave of Venetian colonists in 1222 again led to uprisings, under Theodore and Michael Melissenos. Once again, the Venetian authorities concluded a treaty with the rebel leaders, conceding them two knightly fiefs.

A new rebellion broke out in 1228, involving not only the Skordilides and Melissenoi, but also the Arkoleos and Drakontopoulos families. Both sides requested external aid: the Duke of Crete, Giovanni Storlando, asked for the help of Angelo Sanudo

Angelo Sanudo (died 1262) was the second Duke of the Archipelago from 1227, when his father, Marco I, died, until his own death.

Family

Angelo was a son of Marco I Sanudo. According to "The Latins in the Levant. A History of Frankish Greece (120 ...

, son and successor of Marco, while the Cretans looked to the Greek Empire of Nicaea for aid. A Nicaean fleet of 33 ships arrived on the island, and in the 1230s the Nicaeans were able to challenge Venetian control over much of Crete and maintain troops there. A series of treaties in 1233, 1234, and 1236, ended the uprising, with the concession of new privileges to the local nobility. Only the Drakontopouloi, along with the remnants of the Nicaean troops (the so-called "''Anatolikoi''") continued the fight, based on the fortress of Mirabello (modern Agios Nikolaos). It was only with the aid of the autonomous Greek lord of Rhodes, Leo Gabalas

Leo Gabalas ( el, ) was a Byzantine Greek magnate and independent ruler of a domain, centered on the island of Rhodes and including nearby Aegean islands, which was established in the aftermath of the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire by the ...

, that the Venetians were able to force their withdrawal to Asia Minor in 1236. The fate of the Drakontopouloi is unknown, and they are no longer attested thereafter.

Uprisings of the Chortatzes brothers

Following the reconquest of Constantinople in 1261, and the restoration of the

Following the reconquest of Constantinople in 1261, and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Palaiologos dynasty in the period between 1261 and 1453, from the restoration of Byzantine rule to Constantinople by the usurper Michael VIII Palaiologos following its recapture from the Latin Empire, founde ...

, Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, öö¿üöÝçÇö£ öö¢üö¤öÝü Ã¥ö°ö°öçö£ö¢ü öö¢ö¥ö§öñö§Ã§¡ü ö öÝö£öÝö¿ö¢ö£üö°ö¢ü, Mikhaál Doukas Angelos Komnános Palaiologos; 1224 ã 11 December 1282) reigned as the co-emperor of the Empire ...

endeavoured to recover Crete as well. A certain Sergios was sent to the island, and made contact with the Greek nobles Georgios Chortatzes and Michael Skordiles Psaromelingos. This led to the outbreak of another uprising in 1262, again led by the Skordilides, the Melissenoi, and the Chortatzes family, and supported by the Orthodox clergy. The rebellion raged for four years, but its prospects were never good; not only was Michael VIII unable to send any substantial aid, but the influential Greek noble Alexios Kallergis refused to support it, fearing the loss of his privileges. Finally, in 1265 another treaty ended the uprising, reconfirming the privileges of the Cretan nobles, awarding two more knightly fiefs to their leaders, and allowing the safe departure of Sergios from Crete. On the very next year, however, rumours spread that the Cretan nobles, including the Chortatzes brothers George and Theodore, but also Alexios Kallergis, were plotting another uprising. The dynamic intervention of the Duke Giovanni Velenio Giovanni may refer to:

* Giovanni (name), an Italian male given name and surname

* Giovanni (meteorology), a Web interface for users to analyze NASA's gridded data

* ''Don Giovanni'', a 1787 opera by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, based on the legend of ...

, and Kallergis' own misgivings, led to the failure of these plans. Michael VIII eventually recognised Venetian control of the island in treaties concluded in 1268 and 1277.

In 1272 or 1273, however, George and Theodore Chortatzes launched another uprising in eastern Crete, centred on the Lasithi Plateau. In 1276, the rebels scored a major victory in an open battle in the Messara Plain, in which the Duke of Crete, a ducal councillor, and the "flower of the Venetian colony of Candia" fell. The rebels laid siege to Candia, but on the verge of success, the rebellion began to fall apart due to dissensions among the Cretan nobles: the Psaromelingoi fell out with the Chortatzes clan after one of their own killed a Chortatzes over the division of the spoils, while at the same time Alexios Kallergis openly collaborated with the Venetians. With the arrival of substantial reinforcements from Venice, the uprising was finally defeated in 1278. Unlike with previous rebellions, the Venetians refused a negotiated settlement, and suppressed the revolt with a campaign of terror involving mass reprisals. The Chortatzes family and many of their supporters fled to Asia Minor, where several entered Byzantine service, but the brutal repression of the Venetians created an unbridgeable gulf with the local population.

Rebellion of Alexios Kallergis

Despite his double-dealing and shifting allegiance between Venice and his own compatriots, the defeat of the Chortatzes brothers left Alexios Kallergis as the most prominent and respected of the Cretan nobles. His enormous wealth, as well as his strategically situated fief at Mylopotamos, also gave him great power. This led the Venetians to distrust him; their efforts to curb his power backfired, however, and provoked the start of the largest and most violent of all Cretan rebellions up to that point, in 1282. It is also likely that this uprising too was secretly encouraged by Michael VIII Palaiologos as a distraction for the Venetians, who were allied with his arch-enemy Charles of Anjou. Kallergis was joined by all the prominent families of the Cretan nobility: the Gabalades, Barouches, Vlastoi, and even by Michael Chortatzes, nephew of Theodore and George. The uprising quickly spread across the entire island. The Venetians tried to suppress it through reprisals: Orthodox monasteries, which were often used as bases and refuges by the rebels, were torched, and torture was applied to prisoners. In 1284, entry and settlement in the Lasithi Plateau, which in previous rebellions had served as a base for rebels, was declared completely prohibited, even for herding sheep. Despite the constant stream of reinforcements from the metropolis, the uprising could not be quelled. The Venetian authorities also tried to capture Kallergis and the other leaders, but without success. The situation became dire for Venice in 1296, following the outbreak of war with Genoa. The Genoese admiral Lamba Doria captured and torched Chania, and sent envoys to Kallergis offering an alliance, along with recognition as hereditary ruler of the island. Kallergis, however, refused. This act, together with the general war-weariness and the internal dissensions of the Cretan leaders, opened the path to ending the revolt and coming to terms with Venice.Peace treaty and aftermath

The uprising was terminated with the "Peace of Alexios Kallergis" ( la, Pax Alexii Callergi), signed on 28 April 1299 between Duke Michel Vitali and the rebel leaders. In 33 articles, the treaty proclaimed ageneral amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek Ã¥ö¥ö§öñüüö₤öÝ, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offic ...

and the return of all confiscated possessions and the privileges formerly enjoyed by the rebel leaders, who were also granted a two-year tax exemption for the repayment of any debts accrued. The decisions of the tribunals that the rebels had established during the uprising were recognized, and the ban on mixed marriages between Cretans and Venetians was lifted. Kallergis himself was given extensive new privileges: an additional four knightly fiefs, the right of granting titles and fiefs himself, the right of keeping war horses, the right of leasing the properties of various monasteries, and the right of appointing an Orthodox bishop in the diocese of Arios (renamed as Kallergiopolis), and of renting the neighbouring bishoprics of Mylopotamos and Kalamonas.

The treaty left Kallergis as the virtual ruler of the Orthodox population of Crete; the contemporary chronicler Michael Louloudes, who fled to Crete when Ephesus fell to the Turks, calls him "Lord of Crete", and mentions him right after the Byzantine emperor, Andronikos II Palaiologos. Kallergis steadfastly honoured the terms of the treaty, and remained conspicuously loyal to Venice thereafter. His intervention prevented another revolt from breaking out in 1303, following the destructive earthquake of that year, that had left the Venetian authorities in disarray. Later, in 1311, a letter by the Duke of Crete requests of him to gather information about insurrectionist agitation in Sfakia. When another revolt broke out in Sfakia in 1319, Kallergis interceded with the rebels and Duke Giustiniani to put an end to it. On the same year, minor uprisings by the Vlastoi and Barouches were also ended after Kallergis' intervention. The Venetians rewarded him by inscribing his family into the '' Libro d'Oro'' of the Venetian nobility, but Kallergis' loyalty to Venice provoked the enmity of the other great Cretan families, who tried to assassinate him at Mylopotamos. Alexios Kallergis therefore spent his last years, until his death in 1321, in Candia. His enemies continued to try to assassinate him, but only managed to kill his son, Andreas, with many of his entourage.

Uprisings of 1333ã1334 and 1341ã1347

The peace established by Kallergis lasted until 1333, when Duke Viago Zeno ordered additional taxes to finance the construction of additional galleys, to combat the ever-increasing threat of piracy and raiding along the Cretan coasts. The uprising began as a protest in Mylopotamos, but soon spread to the western provinces in September 1333, under the leadership of Vardas Kallergis, Nikolaos Prikosirides from Kissamos and the three Syropoulos brothers. Despite the participation of one of their relatives, the sons of Alexios Kallergis sided openly with the Venetians, as did other Cretans. The uprising was suppressed in 1334, and its leaders arrested and executed, with the crucial collaboration of Cretan commoners. The families of the rebels were exiled, but the brothers and children of Vardas Kallergis were condemned to life imprisonment as an example; and the entry of non-Cretan Orthodox clergy in the island was prohibited. In 1341, another uprising was launched, by yet another member of the Kallergis family,Leon

Leon, Lûˋon (French) or Leû°n (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* Leû°n, Spain, capital city of the Province of Leû°n

* Province of Leû°n, Spain

* Kingdom of Leû°n, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again f ...

. A grandson or nephew of Alexios, Leon was publicly loyal to Venice, but conspired with other Cretan nobles, the Smyrilios family of Apokoronas. The revolt broke out there, and soon spread to other areas, as other noble families joined it, including the Skordilides (Konstantinos Skordiles was Leon Kallergis' father-in-law), Melissenoi, Psaromelingoi, and others. Alexios Kallergis' namesake grandson, however, again provided crucial assistance to the Venetians: he captured the Smyrilioi, who in turn betrayed Leon Kallergis, whom the Duke Andrea Cornaro threw alive into the sea, tied into a sack. Despite his loss, the revolt continued under the Skordilides and the Psaromelingoi, who had seized control of the mountains of Sfakia and Syvritos. The rebels even besieged the younger Alexios Kallergis at Kastelli. The rebels suffered a major defeat, however, when the Duke managed to ambush the Psaromelingoi and their forces and destroy them at the Messara Plain. The loss of the Psaromelingoi was the prelude to the suppression of the rebellion in 1347, which was again characterized by great brutality and the exile of the rebels' families to Venice.

Revolt of Saint Titus, 1363ã1364

Apart from the Greek nobles, dissatisfaction with the Republic was also growing among the Venetian feudal nobility in Crete, who resented both the heavy taxation and their relegation to a second rank against the nobility of the metropolis. This resentment came to the fore in 1363, when new taxes for repairs in the harbour of Candia were announced. In response, the Venetian feudal lords, led by the Gradenigo and Venier families, rose in rebellion on 9 August 1363. This " Revolt of Saint Titus", as it became known, abolished the Venetian authorities in Candia and declared the island an independent state, the "Republic of Saint Titus", after the island'spatron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

. The rebels sought the assistance of the Greek population, promising equality between Catholics and Orthodox. Several Greek nobles joined them, including the Kallergis clan, and the revolt spread quickly to the rest of the island: in all major cities, the Venetian authorities were overthrown.

Venice tried to negotiate with the rebels, but after this effort failed, it began assembling a large expeditionary force to recover the island by force. The army was headed by the Veronese mercenary captain Lucino dal Verme and the fleet by Domenico Michiele. Once news of this arrived in Crete, many of the rebels began wavering. When the Venetian fleet arrived on 7 May 1364, resistance collapsed quickly. Candia surrendered on 9 May, and most of the other cities followed. Nevertheless, on strict orders from the Venetian government, the Venetian commanders launched a purge of the rebel leadership, including the execution and proscription of the ringleaders, and the disbandment of the Gradenigo and Venier families, who were banished from all Venetian territories. The feudal charter of 1211 was revoked, and all noble families obliged to swear an oath of allegiance to Venice. 10 May was declared a local holiday in Candia, and celebrated with extravagant festivals.

Venice tried to negotiate with the rebels, but after this effort failed, it began assembling a large expeditionary force to recover the island by force. The army was headed by the Veronese mercenary captain Lucino dal Verme and the fleet by Domenico Michiele. Once news of this arrived in Crete, many of the rebels began wavering. When the Venetian fleet arrived on 7 May 1364, resistance collapsed quickly. Candia surrendered on 9 May, and most of the other cities followed. Nevertheless, on strict orders from the Venetian government, the Venetian commanders launched a purge of the rebel leadership, including the execution and proscription of the ringleaders, and the disbandment of the Gradenigo and Venier families, who were banished from all Venetian territories. The feudal charter of 1211 was revoked, and all noble families obliged to swear an oath of allegiance to Venice. 10 May was declared a local holiday in Candia, and celebrated with extravagant festivals.

Rebellion of the Kallergis brothers, 1364ã1367

The quick restoration of Venetian control over the cities did not mean the end of violence on the island, as several proscribed members of the rebel leadership continued to oppose the Venetian authorities. Prominent among them were the three Kallergis brothers, John, George, and Alexios, as well as the brothers Tito and Teodorello Venier, Antonio and Francesco Gradenigo, Giovanni Molino, and Marco Vonale. These launched another uprising in August at Mylopotamos, which quickly spread throughout the western half of Crete. The aims of the rebels had now shifted towards liberating the island and seeking unification with the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine emperor John V Palaiologos also appears to have supported this uprising, sending theMetropolitan of Athens

The Archbishopric of Athens ( el, ööçüö˜ öüüö¿öçüö¿üö¤ö¢üöÛ öö¡öñö§üö§) is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. I ...

Anthimos to the island as '' proedros'' (ecclesiastical ''locum tenens'') of Crete.

Venice reacted by securing a declaration from the Pope granting absolution to any soldier fighting against the rebels, and engaging in extensive recruitment of mercenaries, including Turks. Nevertheless, the rebels managed to extend their reach into eastern Crete, with the Lasithi plateau once again becoming a base of operations for the rebels in their guerrilla warfare against the Venetian authorities. However, the famine of 1365 severely weakened the rebellion. The Venetian rebel leaders were captured through treason and tortured to death, with only Tito Venier escaping this fate by leaving the island. Hunger and fear forced the eastern part of the island to submit to Venice, but the rebellion continued in the west under the Kallergis brothers, based in the inaccessible mountains of Sfakia, until April 1367, when the Venetian ''provveditore'' Giustiniani managed to enter Sfakia and capture the Kallergis by treason. Venetian reprisals were extensive, leading to the virtual destruction of the native nobility. To further ensure that no other uprisings could take place, the mountainous areas of Mylopotamos, Lasithi, and Sfakia were evacuated and entrance into them prohibited for any purpose whatsoever. The Kallergis uprising was indeed to prove the last of the great Cretan rebellions against Venice: deprived of their natural leadership and naturally secure strongholds, and faced with the ever-increasing threat of Ottoman conquest, the Cretans, apart from some small-scale incidents, accommodated themselves to Venetian rule.

Under the shadow of Ottoman invasion: Crete in the 15thã17th centuries

The internal tranquility that followed the end of the large-scale uprisings led to considerable prosperity for the island, particularly during what the historianFreddy Thiriet Freddy or Freddie may refer to:

Entertainment

*Freddy (comic strip), a newspaper comic strip which ran from 1955 to 1980

* Freddie (Cromartie), a character from the Japanese manga series''Cromartie High School''

* Freddie (dance), a short-lived 19 ...

labelled the "half-century of prosperity", 1400ã1450.

Crete had always been of particular importance among Venice's colonies, but its importance increased as the Ottomans started wresting away Venice's overseas possessions in a series of conflicts that began after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. By the middle of the 16th century, Crete was the only major Venetian possession left in the Aegean, and following the loss of Cyprus in 1570ã1571, in the entire Eastern Mediterranean. The emergence of the Ottoman threat coincided with a period of economic decline for the Venetian Republic, which hampered its ability to effectively strengthen Crete. In addition, internal strife on the island, and the local aristocracy's resistance to reforms, compounded the problem.

The Fall of Constantinople caused a deep impression among the Cretans, and in its aftermath, a series of anti-Venetian conspiracies took place. The first was the

Crete had always been of particular importance among Venice's colonies, but its importance increased as the Ottomans started wresting away Venice's overseas possessions in a series of conflicts that began after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. By the middle of the 16th century, Crete was the only major Venetian possession left in the Aegean, and following the loss of Cyprus in 1570ã1571, in the entire Eastern Mediterranean. The emergence of the Ottoman threat coincided with a period of economic decline for the Venetian Republic, which hampered its ability to effectively strengthen Crete. In addition, internal strife on the island, and the local aristocracy's resistance to reforms, compounded the problem.

The Fall of Constantinople caused a deep impression among the Cretans, and in its aftermath, a series of anti-Venetian conspiracies took place. The first was the conspiracy of Sifis Vlastos The Conspiracy of Sifis Vlastos ( el, öÈü

ö§ö¢ö¥üüö₤öÝ üö¢ü

öÈöÛüöñ öö£öÝüüö¢ü) was a fifteenth-century planned rebellion against the Republic of Venice in the overseas colony of Crete, named after its chief instigator. Vlastos and his col ...

in Rethymno, which even included a fake letter by the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos. The conspiracy was betrayed to the Venetian authorities by the priest Ioannis Limas and Andrea Nigro, in exchange for money and privileges. 39 individuals were charged with participation, among them many priests. In November 1454, as a retaliation, the authorities banned the ordination of Orthodox priests for five years. Another conspiracy was betrayed in 1460, causing the Venetians to launch a persecution of many locals, as well as Greek refugees from mainland Greece. The '' protopapas'' of Rethymno, Petros Tzangaropoulos, was among the leaders of the conspiracy. Although the revolutionary agitation subsided, the authorities remained nervous; in 1463, the settlement of the Lasithi plateau was allowed to produce grain in order to counter the famine, but as soon as the immediate danger had passed, it was banned again in 1471, and remained so until the early 16th century. In 1471, during the First OttomanãVenetian War

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

, the Ottoman fleet plundered the eastern parts of the island around Siteia.

It was not until 1523 that the first moves towards another Cretan revolt, under the leadership of Georgios Kantanoleos, started taking place. Exasperated by the heavy tax burden and the arbitrariness of Venetian government, about 600 men rose up in revolt around Kerameia. The Venetian authorities initially hesitated to move against the rebels, for fear of causing a wider uprising. In October 1527, however, Geronimo Corner with 1,500 troops marched against the rebels. The uprising was suppressed with great violence, and all the villages in the rebel area were destroyed. Three of the leaders, the brothers Georgios and Andronikos Chortatsis, and Leon Theotokopoulos, were betrayed in 1528 and hanged, while Kantanoleos himself was proscribed for 1,000 ''hyperpyra

The ''hyperpyron'' ( ''nû°misma hypûˋrpyron'') was a Byzantine coin in use during the late Middle Ages, replacing the ''solidus'' as the Byzantine Empire's gold coinage.

History

The traditional gold currency of the Byzantine Empire had been the '' ...

'', and also betrayed. Altogether some 700 people were killed; many families were exiled to Cyprus, in the area of Paphos

Paphos ( el, ö ö˜üö¢ü ; tr, Baf) is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and New Paphos.

The current city of P ...

, but after about a decade many were allowed to return and even reclaim their possessions on Crete.

During the Third OttomanãVenetian War, the Ottomans demanded the recognition of the Sultan's overlordship over Crete and the payment of an annual tribute. In June 1538, the Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa captured Mylopotamos, Apokoronas

Apokoronas ( el, öüö¢ö¤üüüö§öÝü) is a municipality and a former province (öçüöÝüüö₤öÝ) in the Chania regional unit, north-west Crete, Greece. It is situated on the north coast of Crete, to the east of Chania itself. The seat of the muni ...

, and Kerameia, besieged Chania without success, and then marched to Rethymno and Candia. It was only the appeal of the Venetian authorities to the local population, offering amnesty and tax exemptions, that preserved the city, especially when the Kallergis brothers Antonios and Mathios used their fortune to recruit men and strengthen the island's fortifications. Nevertheless, the Turks ravaged the area around Fodele, and destroyed the forts of Mirabello, Siteia, and Palaiokastro. The Ottoman attacks resumed in 1539, when Selino was surrendered by its inhabitants and its Venetian garrison captured. The fortress of Ierapetra

Ierapetra ( el, ööçüö˜üöçüüöÝ, lit=sacred stone; ancient name: ) is a Greek town and municipality located on the southeast coast of Crete.

History

The town of Ierapetra (in the local dialect: ööçüö˜üöçüüö¢ ''Gerapetro'') is located on ...

also fell, but Kissamos resisted successfully.

In 1571, during the war for Cyprus, UluûÏ Ali briefly captured Rethymno and raided Crete, resulting in widespread famine on the island. Some local inhabitants, resentful at Venetian misgovernment, even made contact with the Turks, but the intervention of the Cretan nobleman Matthaios Kallergis managed to calm down spirits, and restore order. Two years later, in 1573, the area around Chania was raided.

Another conflict broke out in November 1571, when the Venetian governor, Marino Cavalli, moved to subdue the area of Sfakia. The isolated and mountainous area had always remained free of effective Venetian control, and their raids in the lowlands and the constant feuds between the leading Sfakian clans caused great insecurity in the wider area. After blockading all passes to Sfakia, Cavalli began laying waste to the region and killing large part of the population. The Sfakians were finally forced to submit, and delegations from the entire region appeared before Cavalli to swear allegiance to Venice. Cavalli's successor, Jacopo Foscarini, took measures to pacify the area, allowing its inhabitants to return to their homes, but soon Sfakia again became a hotbed of disorder, so that in 1608, the governor Nicolas Sagredo prepared to invade the area again, only for the plan to be dismissed by his successor, who restored order by personally touring the region.

Administration

The conquest of Crete brought Venice its first major colony; indeed, the island would remain the largest possession of the Republic until its expansion into the northern Italian mainland (the '' Terraferma'') in the early 15th century. In addition to the unfamiliar challenges of governing a territory of such size and eminence, the distance of Crete from the metropolisãabout a month's journey by galleyãraised dangers and complications. As a result, unlike other colonies, where the Venetian government was content to allow governance by the local Venetian colonists, in Crete the Republic employed salaried officials dispatched from the metropolis. This "made subjects of both the Venetian colonizers and the colonized Greek people of the island", and despite the privileges accorded to the former, their common position of subservience to the metropolis made it more likely for the Venetians and Greeks of Crete to rally together in support of common interests against the metropolitan authorities.

The conquest of Crete brought Venice its first major colony; indeed, the island would remain the largest possession of the Republic until its expansion into the northern Italian mainland (the '' Terraferma'') in the early 15th century. In addition to the unfamiliar challenges of governing a territory of such size and eminence, the distance of Crete from the metropolisãabout a month's journey by galleyãraised dangers and complications. As a result, unlike other colonies, where the Venetian government was content to allow governance by the local Venetian colonists, in Crete the Republic employed salaried officials dispatched from the metropolis. This "made subjects of both the Venetian colonizers and the colonized Greek people of the island", and despite the privileges accorded to the former, their common position of subservience to the metropolis made it more likely for the Venetians and Greeks of Crete to rally together in support of common interests against the metropolitan authorities.

Central government and military command

The regime established by Venice in Crete was modelled after that of the metropolis itself. It was headed by a Duke (''duca di Candia''), and included a Great Council, a Senate, a Council of Ten, the Avogadoria de Comû¿n, and other institutions that existed in the metropolis. The Duke of Crete was elected from among the Venetian patriciate for two-year terms, and was assisted by four, and later only two councillors (''consiglieri''), likewise appointed for two-year terms; of the original four, two were rectors of cities on the island. Together, the Duke and his councillors comprised the '' Signoria'' of Crete. There were also two, and later three, chamberlains (''camerlenghi''), charged with fiscal affairs, and each province had its own treasury (''camera''). The lower strata of the hierarchy were complemented by judges and police officials (the ''giudici'' and the ''Signori di notte''), castellans (''castellani'') and the grand chancellor (''cancelliere grande''). As in most greater territories with a special military importance, military command was vested in a Captain (''capitano''). In times of crisis or war, a '' provveditore generale'' (the ''provveditore generale el regnodi Candia'') was appointed, with supreme power over both civil and military officials on the island. After 1569, as the Ottoman danger increased, the appointment of a ''provveditore generale'' became regular for two-year tenures, and the post came to be held by some of the most eminent statesmen of Venice. A further ''provveditore generale'' was appointed from 1578 to command the island's cavalry, and an admiral, the "Captain of the Guardleet

Leet (or "1337"), also known as eleet or leetspeak, is a system of modified spellings used primarily on the Internet. It often uses character replacements in ways that play on the similarity of their glyphs via reflection or other resemblance ...

of Crete" (''Capitano alla guardia di Candia'') commanded the local naval forces.

Provincial and local administration

Just like the city of Venice itself, the "Venice of the East" was initially divided into six provinces, or '' sestieri''. From east to west these were: * ''Santi Apostoli'' (Holy Apostles) or ''Cannaregio'', comprising the districts of Siteia, Ierapetra, Mirabello, and Lasithi; it was essentially coterminous with the modern Lasithi Prefecture. * ''San Marco'' (St. Mark), comprising the districts of Rizokastro (Ven. Belvedere) andPediada

Pediada ( el, ö öçöÇö¿ö˜öÇöÝ, "plain") is a region and former Provinces of Greece, province of Heraklion Prefecture, Crete, Greece. Its territory corresponded with that of the current municipality Chersonisos, the municipal units Kastelli, Herakli ...

.

* ''Santa Croce'' (Holy Cross), comprising the districts of Monofatsio (Ven. Bonifacio), Kainourgio (Castelnuovo), and Pyrgiotissa.

* ''Castello'', comprising the districts of Mylopotamos, Arios, and Apano Syvritos

* ''San Polo'' (St. Paul), comprising the districts of Kalamonas (i.e., Rethymno), Kato Syvritos or St. Basil's, and Psychros or Apokoronas

Apokoronas ( el, öüö¢ö¤üüüö§öÝü) is a municipality and a former province (öçüöÝüüö₤öÝ) in the Chania regional unit, north-west Crete, Greece. It is situated on the north coast of Crete, to the east of Chania itself. The seat of the muni ...

(Ven. Bicorono).

* ''Dorsoduro'', comprising the districts of Chania, Kissamos, and Selino

From the early 14th century on, the island was divided into four larger provinces (''territoria''):

* ''Territorio'' of ''Candia'', by far the largest in area, roughly equivalent to the modern Heraklion Prefecture along with the Lasithi plateau and Mirabello Province

* ''Territorio'' of Rethymno (Ven. Rettimo), roughly coterminous with the modern Rethymno Prefecture

* ''Territorio'' of Chania (Ven. Canea), roughly coterminous with the modern provinces of

From the early 14th century on, the island was divided into four larger provinces (''territoria''):

* ''Territorio'' of ''Candia'', by far the largest in area, roughly equivalent to the modern Heraklion Prefecture along with the Lasithi plateau and Mirabello Province

* ''Territorio'' of Rethymno (Ven. Rettimo), roughly coterminous with the modern Rethymno Prefecture

* ''Territorio'' of Chania (Ven. Canea), roughly coterminous with the modern provinces of Apokoronas

Apokoronas ( el, öüö¢ö¤üüüö§öÝü) is a municipality and a former province (öçüöÝüüö₤öÝ) in the Chania regional unit, north-west Crete, Greece. It is situated on the north coast of Crete, to the east of Chania itself. The seat of the muni ...

, Kissamos, Kydonia, and Selino

* ''Territorio'' of Siteia, roughly coterminous with the modern Siteia and Ierapetra provinces

With the creation of the ''territoria'', rectors (''rettori'') began to be appointed in their capitals, with civil and held limited military authority in their province: from 1307 in Chania and Rethymno, and from 1314 in Siteia. The ''rettore'' of Chania originally was one of the four councillors of the Duke of Crete. The rectors of Chania and Rethymno were also assisted by a ''provveditore The Italian title ''prov ditore'' (plural ''provveditori''; also known in gr, üüö¢ö§ö¢öñüöÛü, üüö¢öýö£öçüüöÛü; sh, providur), "he who sees to things" (overseer), was the style of various (but not all) local district governors in the exten ...

'' and two councillors each. In addition, there was a special ''provveditore'' appointed over Sfakia, a region which in practice was mostly outside Venetian control. He was subordinate to Candia (but also sometimes to Chania). ''Provveditori'' were also appointed to the important island fortresses of Souda (since 1573), Spinalonga (since 1580), and Grambousa (since 1584). The island was further divided into castellanies and feudal domains held by the local aristocracy.

Society

During Venetian rule, the Greek population of Crete was exposed toRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

culture. A thriving literature in the Cretan dialect of Greek developed on the island. The best-known work from this period is the poem '' Erotokritos'' by Vitsentzos Kornaros (öö¿üüöÙö§öÑö¢ü öö¢üö§ö˜üö¢ü). Another major Cretan literary figures were Marcus Musurus (1470ã1517), Nicholas Kalliakis

Nicholas Kalliakis ( el, öö¿ö¤üö£öÝö¢ü ööÝö£ö£ö¿ö˜ö¤öñü, ''Nikolaos Kalliakis''; la, Nicolaus Calliachius; it, Niccolûý Calliachi; c. 1645 - 8 May 1707) was a Cretan Greek scholar and philosopher who flourished in Italy in the 17th century ...

(1645ã1707), Andreas Musalus

Andreas Musalus ( la, Andreas Musalus, it, Andrea Musalo, gr, öö§öÇüöÙöÝü öö¢ü

üö˜ö£ö¢ü; ca. 1665/6 ã ca. 1721) was a Greek professor of mathematics, philosopher and architectural theorist who was largely active in Venice during the 17 ...

(1665ã1721), and other Greek scholars and philosophers who flourished in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

in the 15-17th Centuries.

Georgios Hortatzis was author of the dramatic work '' Erophile''. The painter Domenicos Theotocopoulos, better known as El Greco, was born in Crete in this period and was trained in Byzantine iconography before moving to Italy and later, Spain.

References

Sources

* Abulafia, David: Enrico conte di Malta e la sua Vita nel Mediterraneo: 1203ã1230, in In Italia, Sicilia e nel Mediterraneo: 1100ã1400, 1987. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Regno di Candia

map by Marco Boschini

Byzantine & Christian Museum.gr: "Society and art in Venetian Crete"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kingdom of Candia History of Crete Stato da Mû r 1205 establishments in Europe 13th-century establishments in the Republic of Venice 1669 disestablishments in the Republic of Venice States and territories established in 1205 States and territories disestablished in the 1660s