The Province of Pomerania (german: Provinz Pommern; pl, Prowincja Pomorze) was a

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

of

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

from 1815 to 1945. Pomerania was established as a province of the

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

in 1815, an expansion of the older

Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohe ...

province of

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, and then became part of the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in 1871. From 1918, Pomerania was a province of the

Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domina ...

until it was dissolved in 1945 following

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and its territory divided between Poland and

Allied-occupied Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

. The city of

Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

(present-day

Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, Poland) was the provincial capital.

Etymology

The name ''Pomerania'' comes from

Slavic , which means "Land at the Sea".

Overview

The province was created from the

former Prussian Province of Pomerania, which consisted of

Farther Pomerania and the southern

Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

, and former

Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

. It resembled the territory of the former

Duchy of Pomerania

The Duchy of Pomerania (german: Herzogtum Pommern; pl, Księstwo Pomorskie; Latin: ''Ducatus Pomeraniae'') was a duchy in Pomerania on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, ruled by dukes of the House of Pomerania (''Griffins''). The country ha ...

, which after the

Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

in 1648 had been split between

Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohe ...

and Sweden. Also, the districts of

Schivelbein and

Dramburg

Drawsko Pomorskie (until 1948 pl, Drawsko; formerly german: Dramburg) is a town in Drawsko County in West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland, the administrative seat of Drawsko County and the urban-rural commune of Gmina Drawsko Po ...

, formerly belonging to the

Neumark

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Call ...

, were merged into the new province.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 366, ]

While in the Kingdom of Prussia, the province was heavily influenced by the reforms of

Karl August von Hardenberg

Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg (31 May 1750, in Essenrode- Lehre – 26 November 1822, in Genoa) was a Prussian statesman and Prime Minister of Prussia. While during his late career he acquiesced to reactionary policies, earlier in his career ...

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 393ff, ] and

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 420ff, ] The

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

primarily affected the

Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

area and the infrastructure, while most of the province retained a rural and agricultural character.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 412, 413, 464ff, ] From 1850, the

net migration rate

Net or net may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Net (mathematics), a filter-like topological generalization of a sequence

* Net, a linear system of divisors of dimension 2

* Net (polyhedron), an arrangement of polygons that can be folded up ...

was negative;

Pomeranians emigrated primarily to Berlin, the West German industrial regions and overseas.

After World War I, democracy and the

women's right to vote

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

were introduced to the province. After

Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

's abdication, it was part of the

Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domina ...

.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 472ff, ] The economic situation worsened due to the consequences of World War I and worldwide

recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 443ff, 481ff, ] As in the previous Kingdom of Prussia, Pomerania was a stronghold of the

national conservatives[''Adolf Hitler: a biographical companion'' David Nicholls page 178 ;(November 1, 2000 ''The main nationalist party the German National People's Party DNVP was divided between reactionary conservative monarchists, who wished to turn the clock back to the pre-1918 Kaisereich, and more radical ''volkisch'' and anti-Semitic elements. It also inherited the support of the old Pan-German League, whose nationalists rested on the belief in the inherent superiority of the German people''] who continued in the Weimar Republic.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 377ff, 439ff, 491ff, ]

In 1933, the

Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

established a

totalitarian regime, concentrating the province's administration in the hands of their , and implementing . The German

invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

in 1939 was launched in part from Pomeranian soil. Jewish and Polish populations (whose minorities lived in the region) were classified as "

subhuman" by the German state during the war and subjected to repressions, slave work and executions. Opponents were arrested and executed; Jews who by 1940 had not emigrated were all deported to the

Lublin reservation

The Nisko Plan was an operation to deport Jews to the Lublin District of the General Governorate of occupied Poland in 1939. Organized by Nazi Germany, the plan was cancelled in early 1940.

The idea for the expulsion and resettlement of the Jews ...

.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 500ff, 509ff ]

Besides the air raids conducted since 1943, World War II reached the province in early 1945 with the

East Pomeranian Offensive and the

Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula– ...

, both launched and won by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

. Insufficient evacuation left the population subject to murder,

war rape

Wartime sexual violence is rape or other forms of sexual violence committed by combatants during armed conflict, war, or military occupation often as spoils of war, but sometimes, particularly in ethnic conflict, the phenomenon has broader so ...

, and plunder by the successors.

When the war was over, the

Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers a ...

cut the province in two unequal parts. The smaller western part became part of the East German State of

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV; ; nds, Mäkelborg-Vörpommern), also known by its anglicized name Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, is a state in the north-east of Germany. Of the country's sixteen states, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern ranks 14th in po ...

. The larger eastern part was attached to post-war Poland as

Szczecin Voivodeship. After the war,

ethnic Germans were expelled from Poland and the area was re-settled with Poles.

[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 515, ] Currently, most of the territory of the province lies within the

West Pomeranian Voivodeship

The West Pomeranian Voivodeship, also known as the West Pomerania Province, is a voivodeship (province) in northwestern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Szczecin. Its area equals 22 892.48 km² (8,838.84 sq mi), and in 2021, it was ...

, which share the same city—now

Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

—as its capital.

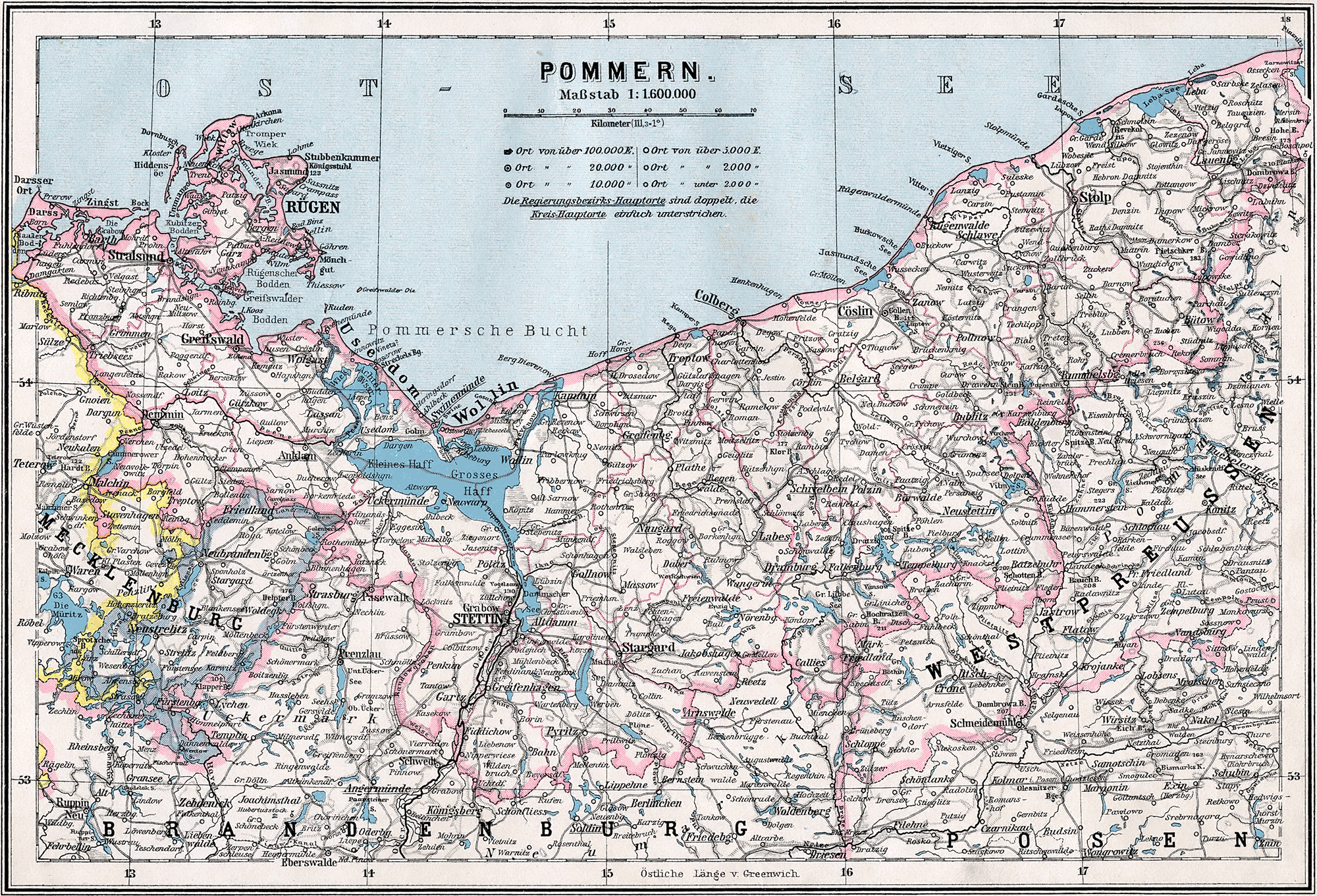

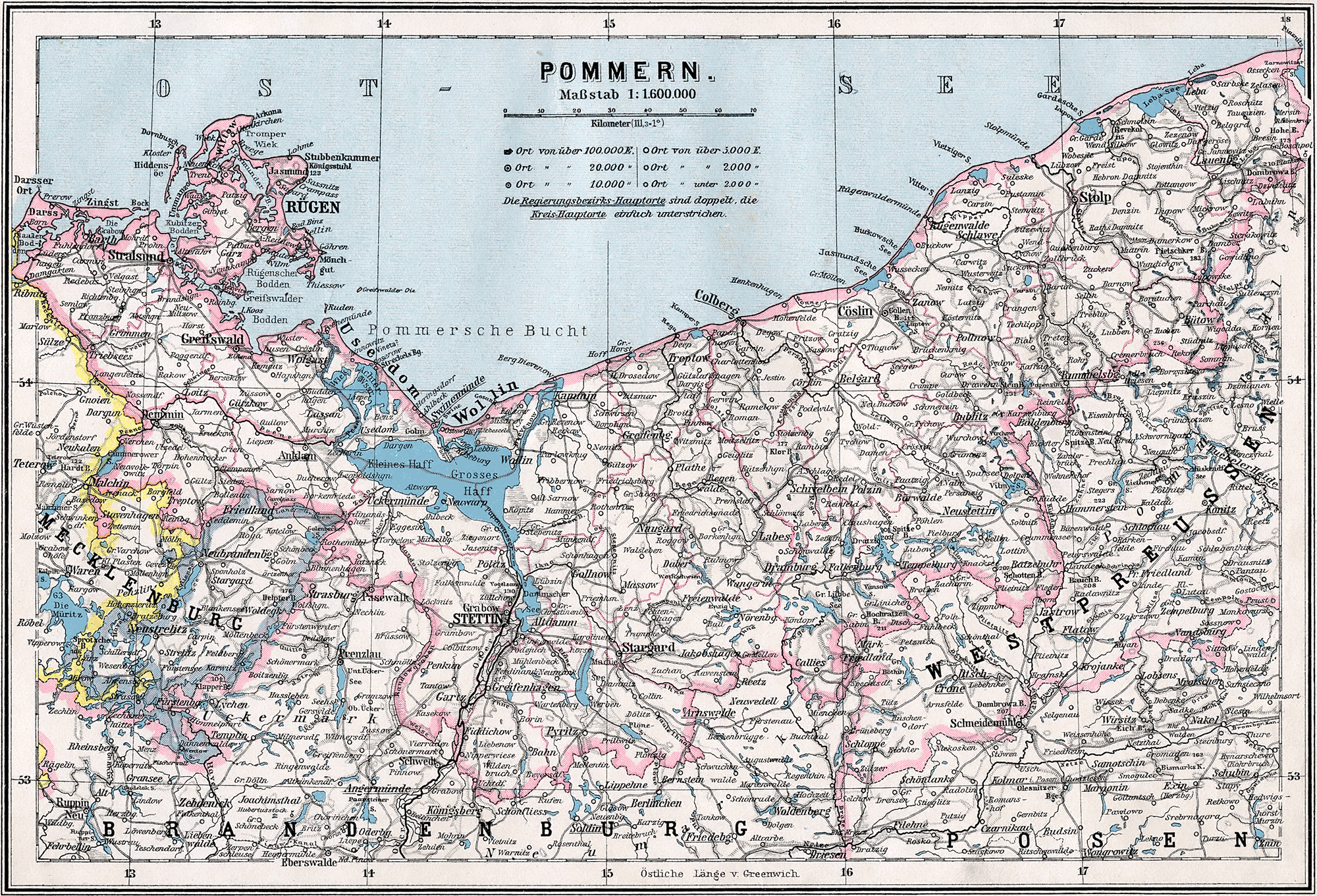

Until 1932, the province was subdivided into the government regions (

Regierungsbezirk Köslin (eastern part,

Farther Pomerania),

Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

(southwestern part, Old Western Pomerania), and

Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

(northwestern part, ).

[Peter Oliver Loew, ''Staatsarchiv Stettin: Wegweiser durch die Bestände bis zum Jahr 1945'', a translation of Radosław Gaziński, Paweł Gut, Maciej Szukała, ''Archiwum Państwowe w Szczecinie, Poland. Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych'', Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2004, pp. 91–92, ] The Stralsund region was merged into the Stettin region in 1932. In 1938, the

Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia region (southeastern part, created from the former

Prussian Province Posen-West Prussia

The Frontier March of Posen-West Prussia (german: Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen, pl, Marchia Graniczna Poznańsko-Zachodniopruska) was a province of Prussia from 1922 to 1938. Posen-West Prussia was established in 1922 as a province of the Fre ...

) was merged into the province.

[ The provincial capital was ]Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

(now Szczecin), the capitals were Köslin (now Koszalin), Stettin, Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

and Schneidemühl (now Piła), respectively.[

In 1905 the Province of Pomerania had 1,684,326 inhabitants, among them 1,616,550 Protestants, 50,206 Catholics, and 9,660 Jews. In 1900 Polish was the native language of 14,162 of the inhabitants (at the border to ]West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a Provinces of Prussia, province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kin ...

), and there were 310 (at the Lake Leba and at the Lake Garde) whose native language was Kashubian. The area of the province amounted to . In 1925, the province had an area of , with a population of 1,878,780 inhabitants.

Creation and administration of the province within the Kingdom of Prussia

Although there had been a Prussian Province of Pomerania before, the Province of Pomerania was newly constituted in 1815, based on the "decree concerning improved establishment of provincial offices" (german: link=no, Verordnung wegen verbesserter Einrichtung der Provinzialbehörden), issued by

Although there had been a Prussian Province of Pomerania before, the Province of Pomerania was newly constituted in 1815, based on the "decree concerning improved establishment of provincial offices" (german: link=no, Verordnung wegen verbesserter Einrichtung der Provinzialbehörden), issued by Karl August von Hardenberg

Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg (31 May 1750, in Essenrode- Lehre – 26 November 1822, in Genoa) was a Prussian statesman and Prime Minister of Prussia. While during his late career he acquiesced to reactionary policies, earlier in his career ...

on 30 April, and the integration of Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

, handed over to Prussia on 23 October.Dramburg

Drawsko Pomorskie (until 1948 pl, Drawsko; formerly german: Dramburg) is a town in Drawsko County in West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland, the administrative seat of Drawsko County and the urban-rural commune of Gmina Drawsko Po ...

and Schivelbein counties.Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

, and Regierungsbezirk Köslin, comprising Farther Pomerania). Hardenberg however, who as the Prussian chief diplomat had settled the terms of session of Swedish Pomerania with Sweden at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon ...

, had assured to leave the local constitution in place when the treaty was signed on 7 June 1815. This circumstance led to a creation of a third government region, Regierungsbezirk Stralsund, for the former Swedish Pomerania at the expense of the Stettin region.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 366–369, ]

In early 1818, Governor Johann August Sack had reformed the county () shapes, yet adopted the former shape in most cases. Köslin government region comprised nine counties, Stettin government region thirteen, and Stralsund government region four (identical with the former Swedish (districts)).Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

north of the Peene

The Peene () is a river in Germany.

Geography

The Westpeene, with the Ostpeene as its longer tributary, and the Kleine Peene/Teterower Peene (with a ''Peene '' without specification (or ''Nordpeene'') as its smaller and shorter affluent) flo ...

River) and one for the former Prussian part.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 377, ]

The counties each assembled a , where the knights of the county had one vote each and towns also just one vote.

Infrastructure

In the 19th century, the first overland routes () and railways were introduced in Pomerania. In 1848, 126.8 Prussian miles of new streets had been built. On October 12, 1840, construction of the Berlin-

In the 19th century, the first overland routes () and railways were introduced in Pomerania. In 1848, 126.8 Prussian miles of new streets had been built. On October 12, 1840, construction of the Berlin-Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

railway began, which was finished on 15 August 1843. Other railways followed: Stettin– Köslin (1859), Angermünde–Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

and Züssow–Wolgast

Wolgast (; csb, Wòłogòszcz) is a town in the district of Vorpommern-Greifswald, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is situated on the bank of the river (or strait) Peenestrom, vis-a-vis the island of Usedom on the Baltic coast that can b ...

(1863), Stettin– Stolp (1869), and a connection with Danzig (1870).narrow-gauge railways

A narrow-gauge railway (narrow-gauge railroad in the US) is a railway with a track gauge narrower than standard . Most narrow-gauge railways are between and .

Since narrow-gauge railways are usually built with tighter curves, smaller structur ...

were built for faster transport of crops. The first gas, water, and power plants were built. Streets and canalisation of the towns were modernized.

The construction of narrow-gauge railways was enhanced by a special decree of July 28, 1892, implementing Prussian financial aid programs. In 1900, the total of narrow-gauge railways had passed the threshold.

From 1910 to 1912, most of the province was supplied with electricity as the main lines were built. Plants were built since 1898.

The Świna and lower Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

rivers, the major water route to Stettin, were deepened to five meters and shortened by a canal ( kaiserfahrt) in 1862. In Stettin, heavy industry was settled, making it the only industrial center of the province.

Stettin was connected to Berlin by the Berlin-Stettin waterway in 1914 after eight years of construction. The other traditional waterways and ports of the province, however, declined. Exceptions were only the port of Swinemünde, which was used by the navy, and the port of Stolpmünde, from which parts of the Farther Pomeranian exports were shipped, and the port of Sassnitz, which was built in 1895 for railway ferries to Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

.

With the infrastructural improvements, mass tourism to the Baltic Coast started. The tourist resort () Binz had 80 visitors in 1870, 10,000 in 1900, and 22,000 in 1910. The same phenomenon occurred in other tourist resorts.

Agricultural reform

Already in 1807, Prussia issued a decree () abolishing

Already in 1807, Prussia issued a decree () abolishing serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. Hardenberg issued a decree on September 14, 1811, defining the terms by which serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

were to be released (). This could either be done by monetary payment or by releasing title to the land to the former lord. These reforms were applied during the early years of the province's existence. The so-called "regulation" was applied to 10,744 peasants until 1838, who paid their former lords 724,954 taler and handed over of farmland to bail themselves out.Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

and Köslin due to food shortages, as a result, prices for some foods were fixed.

On March 2, 1850, a law was passed settling the conditions on which peasants and farmers could capitalize their property rights and feudal service duties, and thus get a long-term credit (41 to 56 years to pay back). This law made way for the establishment of ''Rentenbank'' credit houses and farms. Subsequently, the previous rural structure changed dramatically as farmers, who used this credit to bail out their feudal duties, were now able to self determine how to use their land (so-called "regulated" peasants and farmers, ''regulierte Bauern''). This was not possible before, when the jurisdiction had sanctioned the use of farmland and feudal services according not to property rights, but to social status within rural communities and estates.

From 1891 to 1910, 4,731 farms were set up, most (2,690) with a size of .

Bismarck era administrative reforms

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

inherited from his father the Farther Pomeranian estates Külz, Jarchlin and Kniephof. Aiming at a farming career, he studied agriculture at the academy in Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

-Eldena. From 1867 to 1874, he bought and expanded the Varzin estates.burgher

Burgher may refer to:

* Burgher (social class), a medieval, early modern European title of a citizen of a town, and a social class from which city officials could be drawn

** Burgess (title), a resident of a burgh in northern Britain

** Grand Bu ...

s.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 420ff, 450–453, ]

In 1891, a county reform was passed, allowing more communal self-government. Municipalities hence elected a (head) and a (communal parliament). Gutsbezirk districts, i.e. estates not included in counties, could be merged or dissolved.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 453, ]

World War I

During the First World War, no battles took place in the province.Mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories an ...

resulted in work force shortage affecting all non-war-related industry, construction, and agriculture. Women, minors and POWs partially replaced the drafted men. Import and fishing declined when the ports were blocked. With the war going on, food shortages occurred, especially in the winter of 1916/17. Also coal, gas, and electricity were at times unavailable.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp.468,469, ]

When the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

entered into force on January 10, 1920, the province's eastern frontier became the border to the newly created Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

, comprising most of Pomerelia in the so-called Polish Corridor. Minor border adjustments followed, where 9,5 km2 of the province became Polish and 74 km2 of former West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a Provinces of Prussia, province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kin ...

(parts of the former counties of Neustadt in Westpreußen and Karthaus)[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p.469, ] were merged into the province.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp.443ff, ]

Province of the Free State of Prussia

After the Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

was forced to abdicate, the province became part of the Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domina ...

within the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

.

German Revolution of 1918–19

During the German Revolution of 1918–19

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

, revolutionary councils of soldiers and workers took over the Pomeranian towns (Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

on November 9, Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

, Pasewalk

Pasewalk () is a town in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district, in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in Germany. Located on the Uecker river, it is the capital of the former Uecker-Randow district, and the seat of the Uecker-Randow-Tal '' Amt'' ...

, Stargard

Stargard (; 1945: ''Starogród'', 1950–2016: ''Stargard Szczeciński''; formerly German language, German: ''Stargard in Pommern'', or ''Stargard an der Ihna''; csb, Stôrgard) is a city in northwestern Poland, located in the West Pomeranian V ...

, and Swinemünde on November 10, Barth, Bütow, Neustettin

Szczecinek ( ; German until 1945: ''Neustettin'') is a historic city in Middle Pomerania, northwestern Poland, with a population of more than 40,000 (2011). Formerly in the Koszalin Voivodeship (1950–1998), it has been the capital of Szczecin ...

, Köslin, and Stolp on November 11). On January 5, 1919, "Workers' and Soldiers' Councils" () were in charge of most of the province (231 towns and rural municipalities). The revolution was peaceful, no riots are reported. The councils were led by Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

, who cooperated with the provincial administration. Of the 21 Landrat officials, only five were replaced, while of the three heads of the government regions ("Regierungspräsident") two were replaced (in Stralsund and Köslin) in 1919.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 471, ]

On November 12, 1918, a decree was issued allowing farmworkers' unions to negotiate with farmers ( Junkers). The decree further regulated work time and wages for farmworkers.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 472, ]

On May 15, 1919, street fights and plunder occurred following Communist assemblies in Stettin. The revolt was put down by the military. In late August, strikes of farmworkers occurred in the counties of Neustettin

Szczecinek ( ; German until 1945: ''Neustettin'') is a historic city in Middle Pomerania, northwestern Poland, with a population of more than 40,000 (2011). Formerly in the Koszalin Voivodeship (1950–1998), it has been the capital of Szczecin ...

and Belgard. The power of the councils however declined, only a few were left in the larger towns in 1920.

Counter-revolution

Conservative and right-wing groups evolved in opposition to the revolutions' achievements. Landowners formed the Pommerscher Landbund in February 1919, which by 1921 had 120,000 members and from the beginning was supplied with arms by the 2nd army corps in Stettin. Paramilitias ("Einwohnerwehr") formed throughout the spring of 1919.Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

in Berlin, 1920.Freikorps in the Baltic

After 1918, the term Freikorps was used for the anti-communist paramilitary organizations that sprang up around the German Empire and the Baltics, as soldiers returned in defeat from World War I. It was one of the many Weimar paramilitary groups ...

, reorganized in Pomerania, where the Junkers hosted them on their estates as a private army.Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

participating in fights in the Ruhr area

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

.

Constitution of 1920

In 1920 (changed in 1921 and 1924), the Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domina ...

adopted a democratic constitution for her provinces. The constitution granted a number of civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

to the Prussian population and enhanced the self-government of the provinces.

Economy

The border changes however caused a severe decline in the province's economy. Farther Pomerania was cut off from Danzig by the corridor. Former markets and supplies in the now Polish territories became unavailable.Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

. Due to high transport costs, the markets in the West were unavailable too. The farmers reacted by modernizing their equipment, improving the quality of their products, and applying new technical methods. As a consequence, more than half of the farmers were severely indebted in 1927. The government reacted with the Osthilfe Eastern Aid (''Osthilfe'') was a policy of the German Government of the Weimar Republic (1919–33) to give financial support from Government funds to bankrupt estates in East Prussia.

The policy was implemented beginning in 1929–1930, in spite ...

program, and granted credits to favourable conditions.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 481, ]

Stettin particularly suffered from a post-war change in trade routes. Before the territorial changes, it had been on the export route from the Katowice

Katowice ( , , ; szl, Katowicy; german: Kattowitz, yi, קאַטעוויץ, Kattevitz) is the capital city of the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland and the central city of the Upper Silesian metropolitan area. It is the 11th most popu ...

(Kattowitz) industrial region in now Polish Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

. Poland changed this export route to a new inner-Polish railway connecting Katowice with the new-build port of Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

within the corridor.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 443ff., ]

As a counter-measure, Prussia invested in the Stettin port since 1923. While initially successful, a new economical recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

led to the closure of one of Stettin's major shipyard, AG Vulcan Stettin

Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin (short AG Vulcan Stettin) was a German shipbuilding and locomotive building company. Founded in 1851, it was located near the former eastern German city of Stettin, today Polish Szczecin. Because of the limited ...

, in 1927.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 485, ]

The province also reacted to the availability of new traffic vehicles. Roads were developed due to the upcoming cars and buses, four towns got electric street cars, and an international airport was built in Altdamm near Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

.Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a ...

, and Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and lar ...

, also refugees from the former Province of Posen

The Province of Posen (german: Provinz Posen, pl, Prowincja Poznańska) was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1848 to 1920. Posen was established in 1848 following the Greater Poland Uprising as a successor to the Grand Duchy of Posen, ...

settled in the province. On the other hand, people left the rural communities ''en masse'' and turned to Pomeranian and other urban centers ( Landflucht). In 1925, 50.7% of the Pomeranians worked in agricultural professions, this percentage dropped to 38.2% in 1933.

With the economic recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

, unemployment rates reached 12% in 1933, compared to an overall 19% in the empire.

Nazi era

Pomeranian Nazi movement before 1933

Throughout the existence of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, politics in the province was dominated by the nationalist conservative DNVP (, German National People's Party

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...

); an entity composed of nationalists, monarchists, radical volkisch and anti-semitic elements, and supported by Pan-German League

The Pan-German League (german: Alldeutscher Verband) was a Pan-German nationalist organization which was officially founded in 1891, a year after the Zanzibar Treaty was signed.

Primarily dedicated to the German Question of the time, it held p ...

an old organisation believing in superiority of German people over others.NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

) did not have any significant success at elections, nor did it have a substantial number of members. The Pomeranian Nazi party was founded by students of the University of Greifswald

The University of Greifswald (; german: Universität Greifswald), formerly also known as “Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University of Greifswald“, is a public research university located in Greifswald, Germany, in the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pom ...

in 1922, when the NSDAP was officially forbidden. The university's rector Theodor Vahlen became Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a '' Gau'' or '' Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest rank in the Nazi political leadership, subordinate only to '' Reichsleiter'' and to ...

(head of the provincial party) in 1924. Soon afterwards, he was fired by the university and went bankrupt. In 1924, the party had 330 members, and in December 1925, 297 members. The party was not present in all of the province. The members were concentrated mainly in Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

and internally divided. Vahlen retired from the Gauleiter position in 1927 and was replaced by Walther von Corswandt, a Pomeranian knight estate holder.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 491ff, ]

Corswandt led the party from his estate in Kuntzow. In the 1928 Reichstag elections, the Nazis got 1.5% of the votes in Pomerania. Party property was partially pawned. In 1929, the party gained 4.1% of the votes. Corswandt was fired after conflicts with the party's leadership and replaced with Wilhelm Karpenstein, one of the former students who formed the Pomeranian Nazi party in 1922 and since 1929 lawyer in Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

. He moved the headquarters to Stettin and replaced many of the party officials predominantly with young radicals. In the Reichstag elections of September 14, 1930, the party gained a significant 24.3% of the Pomeranian votes and thus became the second strongest party, the strongest still being the DNVP, which however was internally divided in the early 1930s.

Nazi government since 1933

Immediately after their gain of power, the Nazis began arresting their opponents. In March 1933, 200 people[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 509, ] were arrested, this number rose to 600[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 500, ] during the following months. In Stettin-Bredow, at the site of the bankrupt Vulcan shipyards, the Nazis set up a short-lived "wild" concentration camp from October 1933 to March 1934, where SA maltreated their victims. The Pomeranian SA in 1933 had grown to 100,000 members.Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

due to his friendship to Röhm. Gauleiter Karpenstein was arrested for two years and banned from Pomerania due to conflicts with the NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

headquarters. His substitute, Franz Schwede-Coburg, replaced most of Karpenstein's staff with Corswant's earlier staff, friends of him from Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

, and SS. From the 27 Kreisleiter

''Kreisleiter'' (; "District Leader") was a Nazi Party political rank and title which existed as a political rank between 1930 and 1945 and as a Nazi Party title from as early as 1928. The position of ''Kreisleiter'' was first formed to provide ...

officials, 23 were forced out of office by Schwede-Coburg, who became Gauleiter on July 21, and Oberpräsident on July 28, 1934.Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, the Nazis established totalitarian control over the province by Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

.

Deportation of the Pomeranian Jews

In 1933, about 7,800 Jews lived in Pomerania, of which a third lived in Stettin. The other two thirds were living all over the province, Jewish communities numbering more than 200 people were in Stettin, Kolberg, Lauenburg in Pomerania, and Stolp.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p.506 ]

When the Nazis started to terrorize Jews, many emigrated. Twenty weeks after the Nazis seized power, the number of Jewish Pomeranians had already dropped by eight percent.Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, including the destruction of the Pomeranian synagogues on November 9, 1938 (Reichskristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from ...

), all male Stettin Jews were deported to Oranienburg concentration camp

Oranienburg was an early Nazi concentration camp, one of the first detention facilities established by the Nazis in the state of Prussia when they gained power in 1933. It held the political opponents of Nazi Party from the Berlin region, mos ...

after this event and kept there for several weeks.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 510, ]

On February 12 and 13, 1940, 1,000 to 1,300 Pomeranian Jews, regardless of sex, age and health, were deported from Stettin and Schneidemühl to the Lublin-Lipowa Reservation, that had been set up following the Nisko Plan

The Nisko Plan was an operation to deport Jews to the Lublin District of the General Governorate of occupied Poland in 1939. Organized by Nazi Germany, the plan was cancelled in early 1940.

The idea for the expulsion and resettlement of the Je ...

in occupied Poland. Among the deported were intermarried non-Jewish women. The deportation was carried out in an inhumane manner. Despite low temperatures, the carriages were not heated. No food had been allowed to be taken along. The property left behind was liquidated. Up to 300 people perished from the deportation itself. In the Lublin area under Kurt Engel's regime, the people were subjected to inhumane treatment, starvation and outright murder. Only a few survived the war.

Peter Simonstein Cullman in "History of the Jewish Community of Schneidemühl: 1641 to the Holocaust" and jewishgen.org say that the Jews of Schneidemühl were not "deported together with the more than 1,000 Jews of Stettin egion(who were subsequently sent to Piaski, near Lublin in Poland)", based on lack of evidence in the archives of Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland

The Reich Association of Jews in Germany (german: Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland), also called the ''new one'' for clear differentiation, was a Jewish umbrella organisation formed in Nazi Germany in February 1939. The Association branc ...

(cf. file 75 C Re1, No. 483, Bundesarchiv Berlin, and USHMM Archives: RG-14.003M; Acc. 1993.A.059). He concludes that "while the deportations of the Jews of Schneidemühl had indeed been planned by the Gestapo to coincide with the terrible events that occurred in Stettin – those actions were not carried out together. The deportations of all Jews from the Gau were primarily planned on orders of Franz Schwede-Coburg, the notorious Gauleiter of Pomerania, in cahoots with several Nazi authorities of Schneidemühl. The Gauleiter’s personal goal was to be the first in the Reich to declare his Gau Judenrein – cleansed of Jews". He based his statement on doc. 795 of the Trial of Adolf Eichmann.

According to Cullmann, the following events took place in Schneidemühl: "On February 15, 1940, an order had been issued by the Gestapo in Schneidemühl that the Jews of that town should get ready to be deported within a week, ostensibly to the Generalgouvernement in Eastern Poland. When Dr. Hildegard Böhme of the Reichsvereinigung had become aware of Gauleiter Schwede-Coburg's plan – and fearing a repetition of the events on the scale of the Stettin deportations – her timely and tireless intervention on behalf of the Reichsvereinigung with the RSHA in Berlin resulted in a modification of the planned deportations of Schneidemühl's Jews. The Stapo, the State police in Schneidemühl, however, played its own part in the planned round-up of the city's Jews by giving in to the local Nazi Party cadre and to the orders of the city's fanatic Mayor Friedrich Rogausch, in concert with the Gauleiter. The latter two are known to have planned a Schneidemühl-Aktion as a revenge for the earlier interference by the Reichsvereinigung in the Stettin deportations. Thus on Wednesday, February 21, 1940 – merely one week after the Stettin deportations – one hundred and sixty Jews were arrested in Schneidemühl, while mass arrests of Jews took place concurrently within an radius of Schneidemühl, in the surrounding administrative districts of Köslin, Stettin and the former Grenzmark Posen-Westpreussen, whereby three hundred and eighty-four Jews were seized by the Gestapo. In total 544 Jews were arrested during the entire Aktion in and around Schneidemühl. Those rounded up ranged from two-year-old children to ninety-year-old men. Surviving documents give a grim account of the subsequent Odyssey of those arrested. By then it had been decreed in Berlin that the victims of the round-up should not be sent to Poland but be kept within the so-called Altreich, i.e. within Germany's borders of 1937. Over the following eighteen months most of the arrested became ensnared in the Nazi's maw – on a journey of terminal despair. Only one young woman from Schneidemühl survived the hell of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the death marches of mid-January 1945."

Repressions against Polish minority

Grzęda (1994) says that in 1910, according to German data, 10,500 Poles lived in the Stettin (Szczecin) area, and that in his view the number was most likely reduced. Fenske (1993) and Buchholz et al. (1999) say that in 1910, 7,921 Poles lived steadily in the province;[ Skóra (2001) says that in 1925, according to German data, 5,914 Poles lived in the province (1,104 in the Stettin and 4,226 in the Köslin government regions), while the Polish consul "boldly assumed" that over 9000 Poles lived in the province. Wynot (1996) says that during the interwar era, between 22,500 and 27,000 Poles lived "along the border of the Poznan/Pomorze region", the majority of whom were peasants, with a small number of shopkeepers and craftsmen.][The Poles in Germany, 1919–1939 East European Quarterly, Summer, 1996 by Edward D. Wynot, J]

quote: "This paper attempts to fill that apparent gap in scholarship by providing an overview of the Polish minority in inter-war Germany. ..Whatever its actual size, the German Polish population was internally differentiated in terms of both geographical dispersal and socio-economic profile. By far most lived in areas that adjoined the Polish Republic. ..The final group in this category lived along the border of the Poznan/Pomorze region (22,500–27,000), where, for the most part, they formed Polish islands surrounded by a German sea. The majority were peasants, with a smattering of small shopkeepers and craftsmen sprinkled among their midst and a colony of about 2,000 workers living in the port of Stettin/Szczecin." In addition, "a colony of about 2,000 workers" existed in Stettin.[

A number of the Poles in ]Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

(Stettin) were members of the Union of Poles in Germany

Union of Poles in Germany ( pl, Związek Polaków w Niemczech, german: Bund der Polen in Deutschland e.V.) is an organisation of the Polish minority in Germany, founded in 1922. In 1924, the union initiated collaboration between other minorities, ...

, a Polish scouts team was established there as well,[Tadeusz Białecki, "Historia Szczecina" Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1992 Wrocław.] in addition to a Polish school where the Polish language

Polish (Polish: ''język polski'', , ''polszczyzna'' or simply ''polski'', ) is a West Slavic language of the Lechitic group written in the Latin script. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles. In ad ...

was taught.

Repressions intensified after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

came to power and led to closing of the school.Oranienburg

Oranienburg () is a town in Brandenburg, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Oberhavel.

Geography

Oranienburg is a town located on the banks of the Havel river, 35 km north of the centre of Berlin.

Division of the town

Oranienburg ...

.

Resistance

Resistance groups formed in the economical centers, especially in Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, from where most arrests were reported.DNVP

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...

were tried for founding a monarchist organization.

Other DNVP members, who had addressed their opposition already before 1933, were arrested multiple times after the Nazis had taken over. Ewald Kleist-Schmenzin, Karl Magnus von Knebel-Doberitz, and Karl von Zitzewitz were active resistants.

Within the Pomeranian provincial subsection of the

Within the Pomeranian provincial subsection of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union

The Prussian Union of Churches (known under multiple other names) was a major Protestant church body which emerged in 1817 from a series of decrees by Frederick William III of Prussia that united both Lutheran and Reformed denominations in ...

, resistance was organized within the Pfarrernotbund

The ''Pfarrernotbund'' ( en, Emergency Covenant of Pastors) was an organisation founded on 21 September 1933 to unite German evangelical theologians, pastors and church office-holders against the introduction of the Aryan paragraph into the 28 Pro ...

(150 members in late 1933) and Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German ...

(), the successor organization, headed by Reinold von Thadden-Trieglaff. In March 1935, 55 priests were arrested. The Confessing Church maintained a preachers' seminar headed by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have ...

in Zingst, which moved to Finkenwalde in 1935 and to Köslin and Groß Schlönwitz in 1940. Within the Catholic Church, the most prominent resistance member was Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

priest Alfons Wachsmann, who was executed in 1944.

After the failed assassination attempt of Hitler on July 20, 1944, Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

arrested thirteen Pomeranian nobles and one burgher, all knight estate owners. Of those, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin had contacted Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

in 1938 to inform about the work of the German opposition to the Nazis, and was executed in April 1945. Karl von Zitzewitz had connections to the Kreisauer Kreis group. Among the other arrested were Malte von Veltheim Fürst zu Putbus, who died in a concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

, as well as Alexander von Kameke and Oscar Caminecci-Zettuhn, who both were executed.

World War II and aftermath

First war years

The invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

by the Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

on September 1, 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II, was in part mounted from the province's soil. General Guderian's 19th army corps attacked from the Schlochau and Preußisch Friedland areas, which since 1938 belonged to the province (" Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen").Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

) was a success and the battle front moved far more east (Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air ...

), the province was not the site of battles in the first years of the war.

Since 1943, the province became a target of allied air raids. The first attack was launched against Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

on April 21, 1943, and left 400 dead. On August 17/18, the British RAF launched an attack on Peenemünde

Peenemünde (, en, " Peene iverMouth") is a municipality on the Baltic Sea island of Usedom in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is part of the ''Amt'' (collective municipality) of Usedom-Nord. The commu ...

, where Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

and his staff had developed and tested the world's first ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within t ...

s. In October, Anklam

Anklam [], formerly known as Tanglim and Wendenburg, is a town in the Western Pomerania region of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is situated on the banks of the Peene river, just 8 km from its mouth in the ''Kleines Haff'', the western ...

was a target. Throughout 1944 and early 1945, Stettin's industrial and residential areas were targets of air raids. Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

was a target in October 1944.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 512, ]

Despite these raids, the province was regarded "safe" compared to other areas of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, and thus became a shelter for evacuees primarily from hard-hit Berlin and the West German industrial centers.Volkssturm

The (; "people's storm") was a levée en masse national militia established by Nazi Germany during the last months of World War II. It was not set up by the German Army, the ground component of the combined German ''Wehrmacht'' armed forces, ...

units.Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

's East Pomeranian Offensive Soviet tanks entered the province near Schneidemühl, which surrendered on February 13.

East Pomeranian Offensive

On February 14, the remnants of German

On February 14, the remnants of German Army Group Vistula

Army Group Vistula () was an Army Group of the '' Wehrmacht'', formed on 24 January 1945. It lasted for 105 days, having been put together from elements of Army Group A (shattered in the Soviet Vistula-Oder Offensive), Army Group Centre (similarl ...

() had managed to set up a frontline roughly at the province's southern frontier, and launched a counterattack (Operation Solstice

Operation Solstice (german: Unternehmen Sonnenwende), also known as ''Unternehmen Husarenritt'' or the Stargard tank battle, was one of the last German armoured offensive operations on the Eastern Front in World War II.

It was originally pla ...

, "Sonnenwende") on February 15, that however stalled already on February 18. On February 24, the Second Belorussian Front

The 2nd Belorussian Front (Russian: Второй Белорусский фронт, alternative spellings are 2nd Byelorussian Front) was a military formation, of Army group size, of the Soviet Army during the Second World War. Soviet army gr ...

launched the East Pomeranian Offensive and despite heavy resistance primarily in the Rummelsburg

Rummelsburg () is a subdivision or neighborhood (''Ortsteil'') of the borough (''Bezirk'') of Lichtenberg of the German capital, Berlin.

History

Rummelsburg was founded in 1669. On 30 January 1889 it became a rural municipality, with the name of ...

area took eastern Farther Pomerania until March 10. On March 1, the First Belorussian Front had launched an offensive from the Stargard

Stargard (; 1945: ''Starogród'', 1950–2016: ''Stargard Szczeciński''; formerly German language, German: ''Stargard in Pommern'', or ''Stargard an der Ihna''; csb, Stôrgard) is a city in northwestern Poland, located in the West Pomeranian V ...

and Märkisch Friedland area and succeeded in taking northwestern Farther Pomerania within five days. Cut off corps group Tettau retreated to Dievenow as a moving pocket until March 11. Thus, German-held central Farther Pomerania was cut off, and taken after the Battle of Kolberg (March 4 to 18).[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, pp. 512–515, ]

The fast advances of the Red Army during the East Pomeranian Offensive caught the civilian Farther Pomeranian population by surprise. The land route to the west was blocked since early March. Evacuation orders were issued not at all or much too late. The only way out of Farther Pomerania was via the ports of Stolpmünde, from which 18,300 were evacuated, Rügenwalde, from which 4,300 were evacuated, and Kolberg, which had been declared fortress and from which before the end of the Battle of Kolberg some 70,000 were evacuated. Those left behind became victims of murder, war rape

Wartime sexual violence is rape or other forms of sexual violence committed by combatants during armed conflict, war, or military occupation often as spoils of war, but sometimes, particularly in ethnic conflict, the phenomenon has broader so ...

, and plunder. On March 6, the USAF

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

shelled Swinemünde, where thousands of refugees were stranded, killing an estimated 25,000.[Werner Buchholz, ''Pommern'', Siedler, 1999, p. 514, ]

Battle of Berlin

On March 20, the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

abandoned the last bridgehead on the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

rivers eastern bank, the Altdamm area. The frontline then ran along Dievenow and lower Oder, and was held by the 3rd Panzer Army

The 3rd Panzer Army (german: 3. Panzerarmee) was a German armoured formation during World War II, formed from the 3rd Panzer Group on 1 January 1942.

3rd Panzer Group

The 3rd Panzer Group (german: Panzergruppe 3) was formed on 16 November ...

commanded by general Hasso von Manteuffel

Freiherr Hasso Eccard von Manteuffel (14 January 1897 – 24 September 1978) was a German baron born to the Prussian noble von Manteuffel family and was a general during World War II who commanded the 5th Panzer Army. He was a recipient of th ...

. After another four days of fighting, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

managed to break through and cross the Oder between Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

and Gartz (Oder)

Gartz is a town in the Uckermark district in Brandenburg, Germany. It is located on the West bank of the Oder River, on the border with Poland, about 20 km south of Szczecin, Poland. It is located within the historic region of Western Pomera ...

, thus starting the northern theater of the Battle of Berlin on March 24. Stettin was abandoned the next day.Second Belorussian Front

The 2nd Belorussian Front (Russian: Второй Белорусский фронт, alternative spellings are 2nd Byelorussian Front) was a military formation, of Army group size, of the Soviet Army during the Second World War. Soviet army gr ...

led by general Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Konstantinovich (Xaverevich) Rokossovsky ( Russian: Константин Константинович Рокоссовский; pl, Konstanty Rokossowski; 21 December 1896 – 3 August 1968) was a Soviet and Polish officer who bec ...

advanced through Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

. Demmin

Demmin () is a town in the Mecklenburgische Seenplatte district, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany. It was the capital of the former district of Demmin.

Geography

Demmin lies on the West Pomeranian plain at the confluence of the rivers ...

and Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

surrendered on April 30.Tollense

The Tollense (, from Slavic ''dolenica'' "lowland, (flat) valley") is a river in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in northeastern Germany, right tributary of the Peene.

It has a total length of 95.8 km.

The upper course begins near a small lake ...

and River Peene

The Peene () is a river in Germany.

Geography

The Westpeene, with the Ostpeene as its longer tributary, and the Kleine Peene/Teterower Peene (with a ''Peene '' without specification (or ''Nordpeene'') as its smaller and shorter affluent) flo ...

, while others poisoned themselves. This was fueled by atrocities – rapes, pillage and executions – committed by Red Army soldiers after the Peene-bridge had been destroyed by retreating German troops. 80 percent of the town was destroyed in the first 3 days after its conquest.

In the first days of May, Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

abandoned Usedom

Usedom (german: Usedom , pl, Uznam ) is a Baltic Sea island in Pomerania, divided between Germany and Poland. It is the second largest Pomeranian island after Rügen, and the most populous island in the Baltic Sea.

It is north of the Szczeci ...

and Wollin

Wolin (; formerly german: Wollin ) is the name both of a Polish island in the Baltic Sea, just off the Polish coast, and a town on that island. Administratively, the island belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. Wolin is separated from the ...

islands, and on May 5, the last German troops departed from Sassnitz on the island of Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

. Two days later, Wehrmacht surrendered unconditionally to the Red Army.

Dissolution of the province

File:Western part of the former Province of Pomerania (Vorpommern, red) in modern Germany.png, Western part of the former province (Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

, ''Vorpommern'', red) in modern Germany (grey)

File:Pomerania in rt.GIF, Pomeranian part as of 1937 (orange) of the former eastern territories of Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany (german: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany i.e. Oder–Neisse line which historically had been considered Ger ...

(dark green) now in post-war Poland

File:gmpwp in rt.GIF, Posen-West Prussia

The Frontier March of Posen-West Prussia (german: Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen, pl, Marchia Graniczna Poznańsko-Zachodniopruska) was a province of Prussia from 1922 to 1938. Posen-West Prussia was established in 1922 as a province of the Fre ...

(former ''Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen'') as of 1937 (orange, bulk in Pomerania since 1938) within the former German territories

By the terms of the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

, Western Pomerania east of the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers a ...

became part of Poland. This line left the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

river north of Gartz (Oder)