Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the

reconstructed proto-language of the

Germanic branch of the

Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from

pre-Proto-Germanic into three Germanic branches during the fifth century BC to fifth century AD:

West Germanic

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages). The West Germanic branch is classically subdivided into ...

,

East Germanic

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the ...

and

North Germanic

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also r ...

, which however remained in

contact over a considerable time, especially the

Ingvaeonic languages (including

English), which arose from West Germanic dialects and remained in continued contact with North Germanic.

A defining feature of Proto-Germanic is the completion of the process described by

Grimm's law

Grimm's law (also known as the First Germanic Sound Shift) is a set of sound laws describing the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stop consonants as they developed in Proto-Germanic in the 1st millennium BC. First systematically put forward by Jacob Gr ...

, a set of sound changes that occurred between its status as a dialect of

Proto-Indo-European and its gradual divergence into a separate language. As it is probable that the development of this sound shift spanned a considerable time (several centuries), Proto-Germanic cannot adequately be reconstructed as a simple node in a

tree model

In historical linguistics, the tree model (also Stammbaum, genetic, or cladistic model) is a model of the evolution of languages analogous to the concept of a family tree, particularly a phylogenetic tree in the biological evolution of species. ...

but rather represents a phase of development that may span close to a thousand years. The end of the Common Germanic period is reached with the beginning of the

Migration Period in the fourth century.

The alternative term "

Germanic parent language

In historical linguistics, the Germanic parent language (GPL) includes the reconstructed languages in the Germanic group referred to as Pre-Germanic Indo-European (PreGmc), Early Proto-Germanic (EPGmc), and Late Proto-Germanic (LPGmc), spoken in t ...

" may be used to include a larger scope of linguistic developments, spanning the

Nordic Bronze Age

The Nordic Bronze Age (also Northern Bronze Age, or Scandinavian Bronze Age) is a period of Scandinavian prehistory from c. 2000/1750–500 BC.

The Nordic Bronze Age culture emerged about 1750 BC as a continuation of the Battle Axe culture (th ...

and

Pre-Roman Iron Age in Northern Europe (second to first millennia BC) to include "Pre-Germanic" (PreGmc), "Early Proto Germanic" (EPGmc) and "Late Proto-Germanic" (LPGmc). While Proto-Germanic refers only to the reconstruction of the most recent common ancestor of Germanic languages, the Germanic parent language refers to the entire journey that the dialect of Proto-Indo-European that would become Proto-Germanic underwent through the millennia.

The Proto-Germanic language is not directly attested by any coherent surviving texts; it has been

reconstructed using the

comparative method

In linguistics, the comparative method is a technique for studying the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor and then extrapolating backwards t ...

. However, there is fragmentary direct attestation of (late) Proto-Germanic in early

runic inscriptions (specifically the second-century AD

Vimose inscriptions and the second-century BC

Negau helmet inscription),

and in

Roman Empire era transcriptions of individual words (notably in

Tacitus' ''

Germania'', AD 90).

Archaeology and early historiography

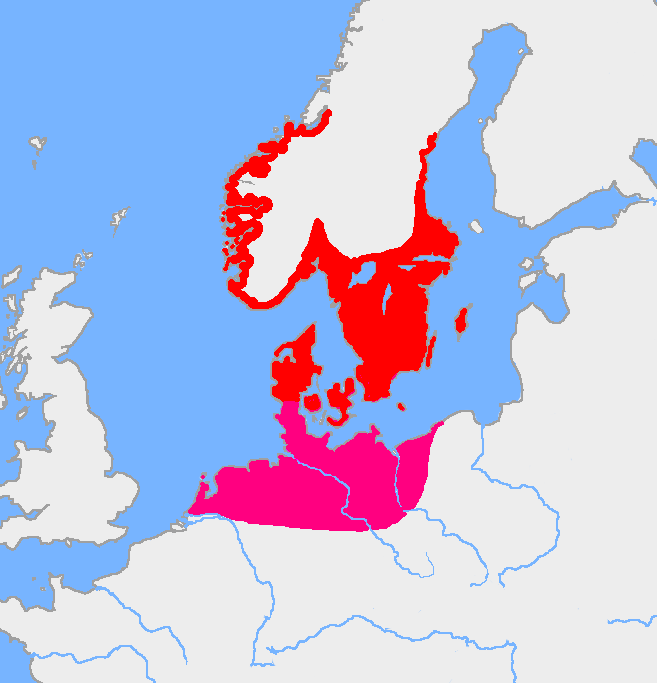

Some sources also give a date of 750 BC for the earliest expansion out of southern Scandinavia along the North Sea coast towards the mouth of the Rhine.

Proto-Germanic developed out of

pre-Proto-Germanic during the

Pre-Roman Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, northern Germany, Poland and the Netherlands.

The regio ...

of Northern Europe. According to the

Germanic substrate hypothesis, it may have been influenced by non-Indo-European cultures, such as the

Funnelbeaker culture

The Funnel(-neck-)beaker culture, in short TRB or TBK (german: Trichter(-rand-)becherkultur, nl, Trechterbekercultuur; da, Tragtbægerkultur; ) was an archaeological culture in north-central Europe.

It developed as a technological merger of lo ...

, but the sound change in the Germanic languages known as

Grimm's law

Grimm's law (also known as the First Germanic Sound Shift) is a set of sound laws describing the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stop consonants as they developed in Proto-Germanic in the 1st millennium BC. First systematically put forward by Jacob Gr ...

points to a non-substratic development away from other branches of Indo-European. Proto-Germanic itself was likely spoken after 500 BC, and

Proto-Norse from the second century AD and later is still quite close to reconstructed Proto-Germanic, but other common innovations separating Germanic from

Proto-Indo-European suggest a common history of pre-Proto-Germanic speakers throughout the

Nordic Bronze Age

The Nordic Bronze Age (also Northern Bronze Age, or Scandinavian Bronze Age) is a period of Scandinavian prehistory from c. 2000/1750–500 BC.

The Nordic Bronze Age culture emerged about 1750 BC as a continuation of the Battle Axe culture (th ...

.

According to Musset (1965), the Proto-Germanic language developed in southern Scandinavia (Denmark, south Sweden and southern Norway), the ''Urheimat'' (original home) of the Germanic tribes. It is possible that Indo-European speakers first arrived in southern Scandinavia with the

Corded Ware culture

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between ca. 3000 BC – 2350 BC, thus from the late Neolithic, through the Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age. Corded Ware culture encompassed a v ...

in the mid-3rd millennium BC, developing into the

Nordic Bronze Age

The Nordic Bronze Age (also Northern Bronze Age, or Scandinavian Bronze Age) is a period of Scandinavian prehistory from c. 2000/1750–500 BC.

The Nordic Bronze Age culture emerged about 1750 BC as a continuation of the Battle Axe culture (th ...

cultures by the early second millennium BC. According to Mallory, Germanicists "generally agree" that the ''

Urheimat

In historical linguistics, the homeland or ''Urheimat'' (, from German '' ur-'' "original" and ''Heimat'', home) of a proto-language is the region in which it was spoken before splitting into different daughter languages. A proto-language is the r ...

'' ('original homeland') of the Proto-Germanic language, the ancestral idiom of all attested Germanic dialects, was primarily situated in an area corresponding to the extent of the

Jastorf culture

The Jastorf culture was an Iron Age material culture in what is now northern Germany and southern Scandinavia spanning the 6th to 1st centuries BC, forming part of the Pre-Roman Iron Age and associating with Germanic peoples. The culture evo ...

.

Early Germanic expansion in the

Pre-Roman Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, northern Germany, Poland and the Netherlands.

The regio ...

(fifth to first centuries BC) placed Proto-Germanic speakers in contact with the

Continental Celtic La Tène horizon. A number of Celtic loanwords in Proto-Germanic have been identified. By the first century AD, Germanic expansion reached the

Danube and the

Upper Rhine in the south and the

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

first entered the

historical record

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world his ...

. At about the same time, extending east of the

Vistula (

Oksywie culture,

Przeworsk culture), Germanic speakers came into contact with early

Slavic cultures, as reflected in early Germanic

loans in Proto-Slavic.

By the third century, Late Proto-Germanic speakers had expanded over significant distance, from the

Rhine to the

Dniepr

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

spanning about . The period marks the breakup of Late Proto-Germanic and the beginning of the (historiographically recorded)

Germanic migrations. The first coherent text recorded in a Germanic language is the

Gothic Bible

The Gothic Bible or Wulfila Bible is the Christian Bible in the Gothic language spoken by the Eastern Germanic (Gothic) tribes in the early Middle Ages.

The translation was allegedly made by the Arian bishop and missionary Wulfila in the f ...

, written in the later fourth century in the language of the

Thervingi

The Thervingi, Tervingi, or Teruingi (sometimes pluralised Tervings or Thervings) were a Gothic people of the plains north of the Lower Danube and west of the Dniester River in the 3rd and the 4th centuries.

They had close contacts with the G ...

Gothic Christians, who had escaped

persecution by moving from Scythia to

Moesia in 348.

The earliest available coherent texts (conveying complete sentences, including verbs) in

Proto-Norse are variably dated to the 2nd century AD, around 300 AD or the first century AD in

runic inscriptions (such as the

Tune Runestone

The Tune stone is an important runestone from about 200–450 AD. It bears runes of the Elder Futhark, and the language is Proto-Norse. It was discovered in 1627 in the church yard wall of the church in Tune, Østfold, Norway. Today it is house ...

). The delineation of Late Common Germanic from Proto-Norse at about that time is largely a matter of convention. Early West Germanic text is available from the fifth century, beginning with the

Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

Bergakker inscription

The Bergakker inscription is an Elder Futhark inscription discovered on the scabbard of a 5th-century sword. It was found in 1996 in the Dutch town of Bergakker, in the Betuwe, a region once inhabited by the Batavi. There is consensus that the f ...

.

Evolution

The evolution of Proto-Germanic from its ancestral forms, beginning with its ancestor

Proto-Indo-European, began with the development of a separate common way of speech among some geographically nearby speakers of a prior language and ended with the dispersion of the proto-language speakers into distinct populations with mostly independent speech habits. Between the two points, many sound changes occurred.

Theories of phylogeny

Solutions

Phylogeny as applied to

historical linguistics involves the evolutionary descent of languages. The phylogeny problem is the question of what specific tree, in the

tree model

In historical linguistics, the tree model (also Stammbaum, genetic, or cladistic model) is a model of the evolution of languages analogous to the concept of a family tree, particularly a phylogenetic tree in the biological evolution of species. ...

of language evolution, best explains the paths of descent of all the members of a language family from a common language, or proto-language (at the root of the tree) to the attested languages (at the leaves of the tree). The

Germanic languages form a tree with Proto-Germanic at its root that is a branch of the Indo-European tree, which in turn has

Proto-Indo-European at its root. Borrowing of lexical items from contact languages makes the relative position of the Germanic branch within Indo-European less clear than the positions of the other branches of Indo-European. In the course of the development of historical linguistics, various solutions have been proposed, none certain and all debatable.

In the evolutionary history of a language family, philologists consider a genetic "tree model" appropriate only if communities do not remain in effective contact as their languages diverge. Early Indo-European had limited contact between distinct lineages, and, uniquely, the Germanic subfamily exhibited a less treelike behaviour, as some of its characteristics were acquired from neighbours early in its evolution rather than from its direct ancestors. The internal diversification of West Germanic developed in an especially non-treelike manner.

Proto-Germanic is generally agreed to have begun about 500 BC. Its hypothetical ancestor between the end of Proto-Indo-European and 500 BC is termed

Pre-Proto-Germanic. Whether it is to be included under a wider meaning of Proto-Germanic is a matter of usage.

Winfred P. Lehmann regarded

Jacob Grimm's "First Germanic Sound Shift", or Grimm's law, and

Verner's law

Verner's law describes a historical sound change in the Proto-Germanic language whereby consonants that would usually have been the voiceless fricatives , , , , , following an unstressed syllable, became the voiced fricatives , , , , . The law w ...

, (which pertained mainly to consonants and were considered for many decades to have generated Proto-Germanic) as pre-Proto-Germanic and held that the "upper boundary" (that is, the earlier boundary) was the fixing of the accent, or stress, on the root syllable of a word, typically on the first syllable. Proto-Indo-European had featured a moveable

pitch-accent consisting of "an alternation of high and low tones" as well as stress of position determined by a set of rules based on the lengths of a word's syllables.

The fixation of the stress led to sound changes in unstressed syllables. For Lehmann, the "lower boundary" was the dropping of final -a or -e in unstressed syllables; for example, post-PIE ''*wóyd-e'' > Gothic ', "knows".

Elmer H. Antonsen agreed with Lehmann about the upper boundary but later found

runic evidence that the -a was not dropped: ''ékwakraz … wraita'', "I, Wakraz, … wrote (this)". He says: "We must therefore search for a new lower boundary for Proto-Germanic."

Antonsen's own scheme divides Proto-Germanic into an early stage and a late stage. The early stage includes the stress fixation and resulting "spontaneous vowel-shifts" while the late stage is defined by ten complex rules governing changes of both vowels and consonants.

By 250 BC Proto-Germanic had branched into five groups of Germanic: two each in the West and the North and one in the East.

[

]

Phonological stages from Proto-Indo-European to end of Proto-Germanic

The following changes are known or presumed to have occurred in the history of Proto-Germanic in the wider sense from the end of Proto-Indo-European up to the point that Proto-Germanic began to break into mutually unintelligible dialects. The changes are listed roughly in chronological order, with changes that operate on the outcome of earlier ones appearing later in the list. The stages distinguished and the changes associated with each stage rely heavily on . Ringe in turn summarizes standard concepts and terminology.

Pre-Proto-Germanic (Pre-PGmc)

This stage began with the separation of a distinct speech, perhaps while it was still forming part of the Proto-Indo-European dialect continuum. It contained many innovations that were shared with other Indo-European branches to various degrees, probably through areal contacts, and mutual intelligibility with other dialects would have remained for some time. It was nevertheless on its own path, whether dialect or language.

Early Proto-Germanic

This stage began its evolution as a dialect of Proto-Indo-European that had lost its laryngeals and had five long and six short vowels as well as one or two overlong vowels. The consonant system was still that of PIE minus palatovelars and laryngeals, but the loss of syllabic resonants already made the language markedly different from PIE proper. Mutual intelligibility might have still existed with other descendants of PIE, but it would have been strained, and the period marked the definitive break of Germanic from the other Indo-European languages and the beginning of Germanic proper, containing most of the sound changes that are now held to define this branch distinctively. This stage contained various consonant and vowel shifts, the loss of the contrastive accent inherited from PIE for a uniform accent on the first syllable of the word root, and the beginnings of the reduction of the resulting unstressed syllables.

Late Proto-Germanic

By this stage, Germanic had emerged as a distinctive branch and had undergone many of the sound changes that would make its later descendants recognisable as Germanic languages. It had shifted its consonant inventory from a system that was rich in plosives to one containing primarily fricatives, had lost the PIE mobile pitch accent for a predictable stress accent, and had merged two of its vowels. The stress accent had already begun to cause the erosion of unstressed syllables, which would continue in its descendants. The final stage of the language included the remaining development until the breakup into dialects and, most notably, featured the development of nasal vowels and the start of umlaut, another characteristic Germanic feature.

Lexical evidence in other language varieties

Loans into Proto-Germanic from other (known) languages or from Proto-Germanic into other languages can be dated relative to each other by which Germanic sound laws have acted on them. Since the dates of borrowings and sound laws are not precisely known, it is not possible to use loans to establish absolute or calendar chronology.

Loans from adjoining Indo-European groups

Most loans from Celtic appear to have been made before or during the Germanic Sound Shift. For instance, one specimen *''rīks'' 'ruler' was borrowed from Celtic *''rīxs'' 'king' (stem *''rīg-''), with ''g'' → ''k''. It is clearly not native because PIE *''ē'' → ''ī'' is typical not of Germanic but Celtic languages. Another is *''walhaz'' "foreigner; Celt" from the Celtic tribal name ''Volcae'' with ''k'' → ''h'' and ''o'' → ''a''. Other likely Celtic loans include *''ambahtaz'' 'servant', *''brunjǭ'' 'mailshirt', *''gīslaz'' 'hostage', *''īsarną'' 'iron', *''lēkijaz'' 'healer', *''laudą'' 'lead', *''Rīnaz'' 'Rhine', and *''tūnaz, tūną'' 'fortified enclosure'. These loans would likely have been borrowed during the Celtic Hallstatt and early La Tène cultures when the Celts dominated central Europe, although the period spanned several centuries.

From East Iranian came *''hanapiz'' 'hemp' (compare Khotanese ''kaṃhā'', Ossetian ''gæn(æ)'' 'flax'), *''humalaz'', ''humalǭ'' 'hops' (compare Osset ''xumællæg''), *''keppǭ'' ~ ''skēpą'' 'sheep' (compare Pers ''čapiš'' 'yearling kid'), *''kurtilaz'' 'tunic' (cf. Osset ''kwəræt'' 'shirt'), *''kutą'' 'cottage' (compare Pers ''kad'' 'house'), *''paidō'' 'cloak', *''paþaz'' 'path' (compare Avestan ''pantā'', gen. ''pathō''), and *''wurstwa'' 'work' (compare Av ''vərəštuua''). The words could have been transmitted directly by the Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

s from the Ukraine plain, groups of whom entered Central Europe via the Danube and created the Vekerzug Culture in the Carpathian Basin (sixth to fifth centuries BC), or by later contact with Sarmatians, who followed the same route. Unsure is *''marhaz'' 'horse', which was either borrowed directly from Scytho-Sarmatian or through Celtic mediation.

Loans into non-Germanic languages

Numerous loanwords believed to have been borrowed from Proto-Germanic are known in the non-Germanic languages spoken in areas adjacent to the Germanic languages.

The heaviest influence has been on the Finnic languages, which have received hundreds of Proto-Germanic or pre-Proto-Germanic loanwords. Well-known examples include PGmc *''druhtinaz'' 'warlord' (compare Finnish '), *''hrengaz'' (later *''hringaz'') 'ring' (compare Finnish ', Estonian '), *''kuningaz'' 'king' (Finnish '),Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic, spoken during the ...

are also known.

Non-Indo-European substrate elements

The term substrate with reference to Proto-Germanic refers to lexical items and phonological elements that do not appear to be descended from Proto-Indo-European. The substrate theory postulates that the elements came from an earlier population that stayed amongst the Indo-Europeans and was influential enough to bring over some elements of its own language. The theory of a non-Indo-European substrate was first proposed by Sigmund Feist, who estimated that about a third of all Proto-Germanic lexical items came from the substrate.

Theo Vennemann has hypothesized a Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

substrate and a Semitic superstrate in Germanic; however, his speculations, too, are generally rejected by specialists in the relevant fields.

Phonology

Transcription

The following conventions are used in this article for transcribing Proto-Germanic reconstructed forms:

* Voiced obstruents appear as ''b'', ''d'', ''g''; this does not imply any particular analysis of the underlying phonemes as plosives , , or fricatives , , . In other literature, they may be written as graphemes with a bar to produce '' ƀ'', '' đ'', '' ǥ''.

* Unvoiced fricatives appear as ''f'', ''þ'', ''h'' (perhaps , , ). may have become in certain positions at a later stage of Proto-Germanic itself. Similarly for , which later became or in some environments.

* Labiovelars appear as ''kw'', ''hw'', ''gw''; this does not imply any particular analysis as single sounds (e.g. , , ) or clusters (e.g. , , ).

* The yod sound appears as ''j'' . Note that the normal convention for representing this sound in Proto-Indo-European is ''y''; the use of ''j'' does not imply any actual change in the pronunciation of the sound.

* Long vowels are denoted with a macron over the letter, e.g. ''ō''. When a distinction is necessary, and are transcribed as ''ē¹'' and ''ē²'' respectively. ''ē¹'' is sometimes transcribed as ''æ'' or ''ǣ'' instead, but this is not followed here.

* Overlong vowels appear with circumflexes, e.g. ''ô''. In other literature they are often denoted by a doubled macron, e.g. ''ō̄''.

* Nasal vowels are written here with an ogonek, following Don Ringe's usage, e.g. ''ǫ̂'' . Most commonly in literature, they are denoted simply by a following n. However, this can cause confusion between a word-final nasal vowel and a word-final regular vowel followed by , a distinction which was phonemic. Tildes (''ã'', ''ĩ'', ''ũ''...) are also used in some sources.

* Diphthongs appear as ''ai'', ''au'', ''eu'', ''iu'', ''ōi'', ''ōu'' and perhaps ''ēi'', ''ēu''. However, when immediately followed by the corresponding semivowel, they appear as ''ajj, aww, eww, iww''. ''u'' is written as ''w'' when between a vowel and ''j''. This convention is based on the usage in .

* Long vowels followed by a non-high vowel were separate syllables and are written as such here, except for ''ī'', which is written ''ij'' in that case.

Consonants

The table below[ lists the consonantal phonemes of Proto-Germanic, ordered and classified by their reconstructed pronunciation. The slashes around the phonemes are omitted for clarity. When two phonemes appear in the same box, the first of each pair is voiceless, the second is voiced. Phones written in parentheses represent allophones and are not themselves independent phonemes. For descriptions of the sounds and definitions of the terms, follow the links on the column and row headings.

Notes:

# was an allophone of before velar obstruents.

# was an allophone of before labiovelar obstruents.

# , and were allophones of , and in certain positions (see below).

# The phoneme written as ''f'' was probably still realised as a bilabial fricative () in Proto-Germanic. Evidence for this is the fact that in Gothic, word-final ''b'' (which medially represents a voiced fricative) devoices to ''f'' and also Old Norse spellings such as ''aptr'' , where the letter ''p'' rather than the more usual ''f'' was used to denote the bilabial realisation before .

]

Grimm's and Verner's law

Grimm's law as applied to pre-proto-Germanic is a chain shift

In historical linguistics, a chain shift is a set of sound changes in which the change in pronunciation of one speech sound (typically, a phoneme) is linked to, and presumably causes, a change in pronunciation of other sounds as well. The soun ...

of the original Indo-European plosives. Verner's Law explains a category of exceptions to Grimm's Law, where a voiced fricative appears where Grimm's Law predicts a voiceless fricative. The discrepancy is conditioned by the placement of the original Indo-European word accent.

''p'', ''t'', and ''k'' did not undergo Grimm's law after a fricative (such as ''s'') or after other plosives (which were shifted to fricatives by the Germanic spirant law); for example, where Latin (with the original ''t'') has ''stella'' "star" and ''octō'' "eight", Middle Dutch has ''ster'' and ''acht'' (with unshifted ''t''). This original ''t'' merged with the shifted ''t'' from the voiced consonant; that is, most of the instances of came from either the original or the shifted .

(A similar shift on the consonant inventory of Proto-Germanic later generated High German

The High German dialects (german: hochdeutsche Mundarten), or simply High German (); not to be confused with Standard High German which is commonly also called ''High German'', comprise the varieties of German spoken south of the Benrath and ...

. McMahon says:"Grimm's and Verner's Laws ... together form the First Germanic Consonant Shift. A second, and chronologically later Second Germanic Consonant Shift ... affected only Proto-Germanic voiceless stops ... and split Germanic into two sets of dialects, Low German in the north ... and High German

The High German dialects (german: hochdeutsche Mundarten), or simply High German (); not to be confused with Standard High German which is commonly also called ''High German'', comprise the varieties of German spoken south of the Benrath and ...

further south ...")

Verner's law is usually reconstructed as following Grimm's law in time, and states that unvoiced fricatives: , , , are voiced when preceded by an unaccented syllable. The accent at the time of the change was the one inherited from Proto-Indo-European, which was free and could occur on any syllable. For example, PIE > PGmc. *''brōþēr'' "brother" but PIE > PGmc. *''mōdēr'' "mother". The voicing of some according to Verner's Law produced , a new phoneme.[ Sometime after Grimm's and Verner's law, Proto-Germanic lost its inherited contrastive accent, and all words became stressed on their root syllable. This was generally the first syllable unless a prefix was attached.

The loss of the Proto-Indo-European contrastive accent got rid of the conditioning environment for the consonant alternations created by Verner's law. Without this conditioning environment, the cause of the alternation was no longer obvious to native speakers. The alternations that had started as mere phonetic variants of sounds became increasingly grammatical in nature, leading to the grammatical alternations of sounds known as grammatischer Wechsel. For a single word, the grammatical stem could display different consonants depending on its grammatical case or its tense. As a result of the complexity of this system, significant levelling of these sounds occurred throughout the Germanic period as well as in the later daughter languages. Already in Proto-Germanic, most alternations in nouns were leveled to have only one sound or the other consistently throughout all forms of a word, although some alternations were preserved, only to be levelled later in the daughters (but differently in each one). Alternations in noun and verb endings were also levelled, usually in favour of the voiced alternants in nouns, but a split remained in verbs where unsuffixed (strong) verbs received the voiced alternants while suffixed (weak) verbs had the voiceless alternants. Alternation between the present and past of strong verbs remained common and was not levelled in Proto-Germanic, and survives up to the present day in some Germanic languages.

]

Allophones

Some of the consonants that developed from the sound shifts are thought to have been pronounced in different ways ( allophones) depending on the sounds around them. With regard to original or Trask says:"The resulting or were reduced to and in word-initial position."

Many of the consonants listed in the table could appear lengthened or prolonged under some circumstances, which is inferred from their appearing in some daughter languages as doubled letters. This phenomenon is termed gemination. Kraehenmann says:"Then, Proto-Germanic already had long consonants … but they contrasted with short ones only word-medially. Moreover, they were not very frequent and occurred only intervocally almost exclusively after short vowels."

The voiced phonemes , , and are reconstructed with the pronunciation of stops in some environments and fricatives in others. The pattern of allophony is not completely clear, but generally is similar to the patterns of voiced obstruent allophones in languages such as Spanish. The voiced fricatives of Verner's Law (see above), which only occurred in non-word-initial positions, merged with the fricative allophones of , , and . Older accounts tended to suggest that the sounds were originally fricatives and later "hardened" into stops in some circumstances. However, Ringe notes that this belief was largely due to theory-internal considerations of older phonological theories, and in modern theories it is equally possible that the allophony was present from the beginning.

Each of the three voiced phonemes , , and had a slightly different pattern of allophony from the others, but in general stops occurred in "strong" positions (word-initial and in clusters) while fricatives occurred in "weak" positions (post-vocalic). More specifically:

* Word-initial and were stops and .

* A good deal of evidence, however, indicates that word-initial was , subsequently developing to in a number of languages. This is clearest from developments in Anglo-Frisian

The Anglo-Frisian languages are the Anglic (English, Scots, and Yola) and Frisian varieties of the West Germanic languages.

The Anglo-Frisian languages are distinct from other West Germanic languages due to several sound changes: besides th ...

and other Ingvaeonic languages. Modern Dutch still preserves the sound of in this position.

* Plosives appeared after homorganic nasal consonants: , , , . This was the only place where a voiced labiovelar could still occur.

* When geminate, they were pronounced as stops , , . This rule continued to apply at least into the early West Germanic languages, since the West Germanic gemination produced geminated plosives from earlier voiced fricatives.

* was after or . Evidence for after is conflicting: it appears as a plosive in Gothic ' "word" (not *''waurþ'', with devoicing), but as a fricative in Old Norse '. hardened to in all positions in the West Germanic languages.

* In other positions, fricatives occurred singly after vowels and diphthongs, and after non-nasal consonants in the case of and .

Labiovelars

Numerous additional changes affected the labiovelar consonants.

# Even before the operation of Grimm's law

Grimm's law (also known as the First Germanic Sound Shift) is a set of sound laws describing the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stop consonants as they developed in Proto-Germanic in the 1st millennium BC. First systematically put forward by Jacob Gr ...

, they were reduced to plain velars next to due to the boukólos rule of PIE. This rule continued to operate as a surface filter, i.e. if a sound change generated a new environment in which a labiovelar occurred near a , it was immediately converted to a plain velar. This caused certain alternations in verb paradigms, such as *''singwaną'' 'to sing' versus *''sungun'' 'they sang'. Apparently, this delabialization also occurred with labiovelars following , showing that the language possessed a labial allophone as well. In this case the entire clusters , and are delabialized to , and .

# After the operation of Verner's law

Verner's law describes a historical sound change in the Proto-Germanic language whereby consonants that would usually have been the voiceless fricatives , , , , , following an unstressed syllable, became the voiced fricatives , , , , . The law w ...

, various changes conspired to almost eliminate voiced labiovelars. Initially, became , e.g. PIE * > PGmc. *''bidiþi'' 'asks for'. The fricative variant (which occurred in most non-initial environments) usually became , but sometimes instead turned into . The only environment in which a voiced labiovelar remained was after a nasal, e.g. in *''singwaną'' 'to sing'.

These various changes often led to complex alternations, e.g. *''sehwaną'' 'to see', *''sēgun'' 'they saw' (indicative), *''sēwīn'' 'they saw' (subjunctive), which were reanalysed and regularised differently in the various daughter languages.

Consonant gradation

posits a process of consonant mutation

Consonant mutation is change in a consonant in a word according to its morphological or syntactic environment.

Mutation occurs in languages around the world. A prototypical example of consonant mutation is the initial consonant mutation of all ...

for Proto-Germanic, under the name ''consonant gradation''. (This is distinct from the consonant mutation processes occurring in the neighboring Samic and Finnic languages, also known as consonant gradation

Consonant gradation is a type of consonant mutation (mostly lenition but also assimilation) found in some Uralic languages, more specifically in the Finnic, Samic and Samoyedic branches. It originally arose as an allophonic alternation betw ...

since the 19th century.) The Proto-Germanic consonant gradation is not directly attested in any of the Germanic dialects, but may nevertheless be reconstructed on the basis of certain dialectal discrepancies in root of the ''n''-stems and the ''ōn''-verbs.

Diachronically, the rise of consonant gradation in Germanic can be explained by Kluge's law, by which geminates arose from stops followed by a nasal in a stressed syllable. Since this sound law only operated in part of the paradigms of the ''n''-stems and ''ōn''-verbs, it gave rise to an alternation of geminated and non-geminated consonants. However, there has been controversy about the validity of this law, with some linguists preferring to explain the development of geminate consonants with the idea of "expressive gemination". The origin of the Germanic geminate consonants is currently a disputed part of historical linguistics with no clear consensus at present.

The reconstruction of ''grading'' paradigms in Proto-Germanic explains root alternations such as Old English ' 'star' < *''sterran-'' vs. Old Frisian ' 'id.' < *''steran-'' and Norwegian (dial.) ' 'to swing' < *''gubōn-'' vs. Middle High German ' 'id.' < *''guppōn-'' as generalizations of the original allomorphy. In the cases concerned, this would imply reconstructing an ''n''-stem nom. *''sterō'', gen. *''sterraz'' < PIE *''h₂stér-ōn'', *''h₂ster-n-ós'' and an ''ōn''-verb 3sg. *''guppōþi'', 3pl. *''gubunanþi'' < *''gʱubʱ-néh₂-ti'', *''gʱubʱ-nh₂-énti''.

Vowels

Proto-Germanic had four short vowels, five or six long vowels, and at least one "overlong" or "trimoric" vowel. The exact phonetic quality of the vowels is uncertain.

Notes:

# could not occur in unstressed syllables except before , where it may have been lowered to already in late Proto-Germanic times.

# All nasal vowels except and occurred word-finally. The long nasal vowels , and occurred before , and derived from earlier short vowels followed by .

PIE ''ə'', ''a'', ''o'' merged into PGmc ''a''; PIE ''ā'', ''ō'' merged into PGmc ''ō''. At the time of the merger, the vowels probably were and , or perhaps and . Their timbres then differentiated by raising (and perhaps rounding) the long vowel to . It is known that the raising of ''ā'' to ''ō'' can not have occurred earlier than the earliest contact between Proto-Germanic speakers and the Romans. This can be verified by the fact that Latin ' later emerges in Gothic as ' (that is, ''Rūmōnīs''). It is explained by Ringe that at the time of borrowing, the vowel matching closest in sound to Latin ''ā'' was a Proto-Germanic ''ā''-like vowel (which later became ''ō''). And since Proto-Germanic therefore lacked a mid(-high) back vowel, the closest equivalent of Latin ''ō'' was Proto-Germanic ''ū'': ''Rōmānī'' > *''Rūmānīz'' > *''Rūmōnīz'' > Gothic '.

A new ''ā'' was formed following the shift from ''ā'' to ''ō'' when intervocalic was lost in ''-aja-'' sequences. It was a rare phoneme, and occurred only in a handful of words, the most notable being the verbs of the third weak class. The agent noun suffix *''-ārijaz'' (Modern English ''-er'' in words such as ''baker'' or ''teacher'') was likely borrowed from Latin around or shortly after this time.

Diphthongs

The following diphthongs are known to have existed in Proto-Germanic:

* Short: , , ,

* Long: , , (possibly , )

Note the change > before or in the same or following syllable. This removed (which became ) but created from earlier .

Diphthongs in Proto-Germanic can also be analysed as sequences of a vowel plus an approximant, as was the case in Proto-Indo-European. This explains why was not lost in *''niwjaz'' ("new"); the second element of the diphthong ''iu'' was still underlyingly a consonant and therefore the conditioning environment for the loss was not met. This is also confirmed by the fact that later in the West Germanic gemination, -''wj''- is geminated to -''wwj''- in parallel with the other consonants (except ).

Overlong vowels

Proto-Germanic had two overlong or trimoraic long vowels ''ô'' and ''ê'' , the latter mainly in adverbs (cf. *''hwadrê'' 'whereto, whither').comparative method

In linguistics, the comparative method is a technique for studying the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor and then extrapolating backwards t ...

, particularly as a way of explaining an otherwise unpredictable two-way split of reconstructed long ''ō'' in final syllables, which unexpectedly remained long in some morphemes but shows normal shortening in others.

Trimoraic vowels generally occurred at morpheme boundaries where a bimoraic long vowel and a short vowel in hiatus contracted, especially after the loss of an intervening laryngeal (-''VHV''-). One example, without a laryngeal, includes the class II weak verbs (''ō''-stems) where a -''j''- was lost between vowels, so that -''ōja'' → ''ōa'' → ''ô'' (cf. *''salbōjaną'' → *''salbôną'' → Gothic ' 'to anoint'). However, the majority occurred in word-final syllables (inflectional endings) probably because in this position the vowel could not be resyllabified. Additionally, Germanic, like Balto-Slavic, lengthened bimoraic long vowels in absolute final position, perhaps to better conform to a word's prosodic template; e.g., PGmc *''arô'' 'eagle' ← PIE *' just as Lith ''akmuõ'' 'stone', OSl ''kamy'' ← *''aḱmō̃'' ← PIE *'. Contrast:

* contraction after loss of laryngeal: gen.pl. *''wulfǫ̂'' "wolves'" ← *''wulfôn'' ← pre-Gmc *''wúlpōom'' ← PIE *'; ō-stem nom.pl. *''-ôz'' ← pre-Gmc *''-āas'' ← PIE *'.

* contraction of short vowels: a-stem nom.pl. *''wulfôz'' "wolves" ← PIE *''wĺ̥kʷoes''.

But vowels that were lengthened by laryngeals did not become overlong. Compare:

* ō-stem nom.sg. *''-ō'' ← *''-ā'' ← PIE *';

* ō-stem acc.sg. *''-ǭ'' ← *''-ān'' ← *''-ām'' (by Stang's law) ← PIE *';

* ō-stem acc.pl. *''-ōz'' ← *''-āz'' ← *''-ās'' (by Stang's law) ← PIE *';

Trimoraic vowels are distinguished from bimoraic vowels by their outcomes in attested Germanic languages: word-final trimoraic vowels remained long vowels while bimoraic vowels developed into short vowels. Older theories about the phenomenon claimed that long and overlong vowels were both long but differed in tone, i.e., ''ô'' and ''ê'' had a "circumflex" (rise-fall-rise) tone while ''ō'' and ''ē'' had an "acute" (rising) tone, much like the tones of modern Scandinavian languages, Baltic, and Ancient Greek, and asserted that this distinction was inherited from PIE. However, this view was abandoned since languages in general do not combine distinctive intonations on unstressed syllables with contrastive stress and vowel length. Modern theories have reinterpreted overlong vowels as having superheavy syllable weight (three moras) and therefore greater length than ordinary long vowels.

By the end of the Proto-Germanic period, word-final long vowels were shortened to short vowels. Following that, overlong vowels were shortened to regular long vowels in all positions, merging with originally long vowels except word-finally (because of the earlier shortening), so that they remained distinct in that position. This was a late dialectal development, because the result was not the same in all Germanic languages: word-final ''ē'' shortened to ''a'' in East and West Germanic but to ''i'' in Old Norse, and word-final ''ō'' shortened to ''a'' in Gothic but to ''o'' (probably ) in early North and West Germanic, with a later raising to ''u'' (the sixth century Salic law still has ''maltho'' in late Frankish).

The shortened overlong vowels in final position developed as regular long vowels from that point on, including the lowering of ''ē'' to ''ā'' in North and West Germanic. The monophthongization of unstressed ''au'' in Northwest Germanic produced a phoneme which merged with this new word-final long ''ō'', while the monophthongization of unstressed ''ai'' produced a new ''ē'' which did not merge with original ''ē'', but rather with ''ē₂'', as it was not lowered to ''ā''. This split, combined with the asymmetric development in West Germanic, with ''ē'' lowering but ''ō'' raising, points to an early difference in the articulation height of the two vowels that was not present in North Germanic. It could be seen as evidence that the lowering of ''ē'' to ''ā'' began in West Germanic at a time when final vowels were still long, and spread to North Germanic through the late Germanic dialect continuum, but only reaching the latter after the vowels had already been shortened.

''ē₁'' and ''ē₂''

''ē₂'' is uncertain as a phoneme and only reconstructed from a small number of words; it is posited by the comparative method because whereas all provable instances of inherited (PIE) *''ē'' (PGmc. *''ē₁'') are distributed in Gothic as ''ē'' and the other Germanic languages as *''ā'', all the Germanic languages agree on some occasions of ''ē'' (e.g., Goth/OE/ON ''hēr'' 'here' ← late PGmc. *''hē₂r''). Gothic makes no orthographic and therefore presumably no phonetic distinction between ''ē₁'' and ''ē₂'', but the existence of two Proto-Germanic long ''e''-like phonemes is supported by the existence of two ''e''-like Elder Futhark runes, Ehwaz

is the reconstructed Proto-Germanic name of the Elder Futhark ''e'' rune , meaning "horse" (cognate to Latin , Gaulish , Tocharian B , Sanskrit , Avestan and Old Irish ). In the Anglo-Saxon futhorc, it is continued as (properly , but spelled ...

and Eihwaz

Eiwaz or Eihaz is the reconstructed Proto-Germanic name of the rune , coming from a word for "yew". Two variants of the word are reconstructed for Proto-Germanic, ''*īhaz'' (''*ē2haz'', from Proto-Indo-European '), continued in Old English as ...

.

Krahe treats ''ē₂'' (secondary ''ē'') as identical with ''ī''. It probably continues PIE ''ēi'', and it may have been in the process of transition from a diphthong to a long simple vowel in the Proto-Germanic period. Lehmann lists the following origins for ''ē₂'':

* ''ēi'': Old High German ', ' 'ham', Goth ' 'side, flank' ← PGmc *''fē₂rō'' ← *''pēi-s-eh₂'' ← PIE *'-.

* ''ea'': The preterite of class 7 strong verbs with ''ai'', ''al'' or ''an'' plus a consonant, or ''ē₁''; e.g. OHG ' 'to plow' ← *''arjanan'' vs. preterite ''iar'', ''ier'' ← *''e-ar-''

* ''iz'', after loss of -''z'': OEng ', OHG ' "reward" (vs. OEng ', Goth ') ← PGmc *''mē₂dō'' ← *''mizdō'' ← PIE *'.

* Certain pronominal forms, e.g. OEng ', OHG ' 'here' ← PGmc *''hiar'', derivative of *''hi''- 'this' ← PIE *' 'this'

* Words borrowed from Latin ''ē'' or ''e'' in the root syllable after a certain period (older loans also show ''ī'').

Nasal vowels

Proto-Germanic developed nasal vowels from two sources. The earlier and much more frequent source was word-final ''-n'' (from PIE ''-n'' or ''-m'') in unstressed syllables, which at first gave rise to short ''-ą'', ''-į'', ''-ų'', long ''-į̄'', ''-ę̄'', ''-ą̄'', and overlong ''-ę̂'', ''-ą̂''. ''-ę̄'' and ''-ę̂'' then merged into ''-ą̄'' and ''-ą̂'', which later developed into ''-ǭ'' and ''-ǫ̂''. Another source, developing only in late Proto-Germanic times, was in the sequences ''-inh-'', ''-anh-'', ''-unh-'', in which the nasal consonant lost its occlusion and was converted into lengthening and nasalisation of the preceding vowel, becoming ''-ą̄h-'', ''-į̄h-'', ''-ų̄h-'' (still written as ''-anh-'', ''-inh-'', ''-unh-'' in this article).

In many cases, the nasality was not contrastive and was merely present as an additional surface articulation. No Germanic language that preserves the word-final vowels has their nasality preserved. Word-final short nasal vowels do not show different reflexes compared to non-nasal vowels. However, the comparative method does require a three-way phonemic distinction between word-final ''*-ō'', ''*-ǭ'' and ''*-ōn'', which each has a distinct pattern of reflexes in the later Germanic languages:

The distinct reflexes of nasal ''-ǭ'' versus non-nasal ''-ō'' are caused by the Northwest Germanic raising of final ''-ō'' to , which did not affect ''-ǭ''. When the vowels were shortened and denasalised, these two vowels no longer had the same place of articulation, and did not merge: ''-ō'' became (later ) while ''-ǭ'' became (later ). This allowed their reflexes to stay distinct.

The nasality of word-internal vowels (from ''-nh-'') was more stable, and survived into the early dialects intact.

Phonemic nasal vowels definitely occurred in Proto-Norse and Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

. They were preserved in Old Icelandic down to at least 1125, the earliest possible time for the creation of the ''First Grammatical Treatise

The First Grammatical Treatise ( is, Fyrsta málfræðiritgerðin ) is a 12th-century work on the phonology of the Old Norse or Old Icelandic language. It was given this name because it is the first of four grammatical works bound in the Icelandic ...

'', which documents nasal vowels. The PG nasal vowels from ''-nh-'' sequences were preserved in Old Icelandic as shown by examples given in the ''First Grammatical Treatise''. For example:

* ''há̇r'' "shark" < ''*hą̄haz'' < PG ''*hanhaz''

* ''ǿ̇ra'' "younger" < ''*jų̄hizô'' < PG ''*junhizô'' (cf. Gothic ')

The phonemicity is evident from minimal pairs like ''ǿ̇ra'' "younger" vs. ''ǿra'' "vex" < ''*wor-'', cognate with English ''weary''.[Einar Haugen, "First Grammatical Treatise. The Earliest Germanic Phonology", ''Language'', 26:4 (Oct–Dec, 1950), pp. 4–64 (p. 33).] The inherited Proto-Germanic nasal vowels were joined in Old Norse by nasal vowels from other sources, e.g. loss of ''*n'' before ''s''. Modern Elfdalian still includes nasal vowels that directly derive from Old Norse, e.g. ' "goose" < Old Norse ' (presumably nasalized, although not so written); cf. German ', showing the original consonant.

Similar surface (possibly phonemic) nasal/non-nasal contrasts occurred in the West Germanic languages down through Proto-Anglo-Frisian of 400 or so. Proto-Germanic medial nasal vowels were inherited, but were joined by new nasal vowels resulting from the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law, which extended the loss of nasal consonants (only before ''-h-'' in Proto-Germanic) to all environments before a fricative (thus including ''-mf-'', ''-nþ-'' and ''-ns-'' as well). The contrast between nasal and non-nasal long vowels is reflected in the differing output of nasalized long ''*ą̄'', which was raised to ''ō'' in Old English and Old Frisian whereas non-nasal ''*ā'' appeared as fronted ''ǣ''. Hence:

* English ''goose'', West Frisian ', North Frisian ' < Old English/Frisian ' < Anglo-Frisian ''*gą̄s'' < Proto-Germanic

* En ''tooth'' < Old English ', Old Frisian ' < Anglo-Frisian ''*tą̄þ'' < Proto-Germanic

* En ''brought'', WFris ' < Old English ', Old Frisian ' < Anglo-Frisian ''*brą̄htæ'' < Proto-Germanic ''*branhtaz'' (the past participle of ).

Phonotactics

Proto-Germanic allowed any single consonant to occur in one of three positions: initial, medial and final. However, clusters could only consist of two consonants unless followed by a suffix, and only certain clusters were possible in certain positions.

It allowed the following clusters in initial and medial position:

* Non-dental obstruent + ''l'': ''pl'', ''kl'', ''fl'', ''hl'', ''sl'', ''bl'', ''gl'', ''wl''

* Non-alveolar obstruent + ''r'': ''pr'', ''tr'', ''kr'', ''fr'', ''þr'', ''hr'', ''br'', ''dr'', ''gr'', ''wr''

* Non-labial obstruent + ''w'': ''tw'', ''dw'', ''kw'', ''þw'', ''hw'', ''sw''

* Voiceless velar + ''n'', ''s'' + nasal: ''kn'', ''hn'', ''sm'', ''sn''

It allowed the following clusters in medial position only:

* ''tl''

* Liquid + ''w'': ''lw'', ''rw''

* Geminates: ''pp'', ''tt'', ''kk'', ''ss'', ''bb'', ''dd'', ''gg'', ''mm'', ''nn'', ''ll'', ''rr'', ''jj'', ''ww''

* Consonant + ''j'': ''pj'', ''tj'', ''kj'', ''fj'', ''þj'', ''hj'', ''zj'', ''bj'', ''dj'', ''gj'', ''mj'', ''nj'', ''lj'', ''rj'', ''wj''

It allowed continuant + obstruent clusters in medial and final position only:

* Fricative + obstruent: ''ft'', ''ht'', ''fs'', ''hs'', ''zd''

* Nasal + obstruent: ''mp'', ''mf'', ''ms'', ''mb'', ''nt'', ''nk'', ''nþ'', ''nh'', ''ns'', ''nd'', ''ng'' (however ''nh'' was simplified to ''h'', with nasalisation and lengthening of the previous vowel, in late Proto-Germanic)

* Liquid + obstruent: ''lp'', ''lt'', ''lk'', ''lf'', ''lþ'', ''lh'', ''ls'', ''lb'', ''ld'', ''lg'', ''lm'', ''rp'', ''rt'', ''rk'', ''rf'', ''rþ'', ''rh'', ''rs'', ''rb'', ''rd'', ''rg'', ''rm'', ''rn''

The ''s'' + voiceless plosive clusters, ''sp'', ''st'', ''sk'', could appear in any position in a word.

Later developments

Due to the emergence of a word-initial stress accent, vowels in unstressed syllables were gradually reduced over time, beginning at the very end of the Proto-Germanic period and continuing into the history of the various dialects. Already in Proto-Germanic, word-final and had been lost, and had merged with in unstressed syllables. Vowels in third syllables were also generally lost before dialect diversification began, such as final ''-i'' of some present tense verb endings, and in ''-maz'' and ''-miz'' of the dative plural ending and first person plural present of verbs.

Word-final short nasal vowels were however preserved longer, as is reflected Proto-Norse which still preserved word-final ''-ą'' (''horna'' on the Gallehus horns), while the dative plural appears as ''-mz'' (''gestumz'' on the Stentoften Runestone

The Stentoften Runestone, listed in the Rundata catalog as DR 357, is a runestone which contains a curse in Proto-Norse that was discovered in Stentoften, Blekinge, Sweden.

Inscription

Transliteration

:AP niuhAborumz ¶ niuhagestumz ¶ hAþuwol ...

). Somewhat greater reduction is found in Gothic, which lost all final-syllable short vowels except ''u''. Old High German and Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

initially preserved unstressed ''i'' and ''u'', but later lost them in long-stemmed words and then Old High German lost them in many short-stemmed ones as well, by analogy.

Old English shows indirect evidence that word-final ''-ą'' was preserved into the separate history of the language. This can be seen in the infinitive ending ''-an'' (< *''aną'') and the strong past participle ending ''-en'' (< *''-anaz''). Since the early Old English fronting of to did not occur in nasalized vowels or before back vowels, this created a vowel alternation because the nasality of the back vowel ''ą'' in the infinitive ending prevented the fronting of the preceding vowel: *''-aną'' > *''-an'', but *''-anaz'' > *''-ænæ'' > *''-en''. Therefore, the Anglo-Frisian brightening

The phonological system of the Old English language underwent many changes during the period of its existence. These included a number of vowel shifts, and the palatalisation of velar consonants in many positions.

For historical development ...

must necessarily have occurred very early in the history of the Anglo-Frisian languages, before the loss of final ''-ą''.

The outcome of final vowels and combinations in the various daughters is shown in the table below:

Note that some Proto-Germanic endings have merged in all of the literary languages but are still distinct in runic Proto-Norse, e.g. ''*-īz'' vs. ''*-ijaz'' (''þrijōz dohtrīz'' "three daughters" in the Tune stone vs. the name ''Holtijaz'' in the Gallehus horns).

Morphology

Reconstructions are tentative and multiple versions with varying degrees of difference exist. All reconstructed forms are marked with an asterisk (*).

It is often asserted that the Germanic languages have a highly reduced system of inflections as compared with Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, or Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

. Although this is true to some extent, it is probably due more to the late time of attestation of Germanic than to any inherent "simplicity" of the Germanic languages. As an example, there are less than 500 years between the Gothic Gospels of 360 and the Old High German Tatian of 830, yet Old High German, despite being the most archaic of the West Germanic languages, is missing a large number of archaic features present in Gothic, including dual and passive markings on verbs, reduplication in Class VII strong verb past tenses, the vocative case, and second-position ( Wackernagel's Law) clitics. Many more archaic features may have been lost between the Proto-Germanic of 200 BC or so and the attested Gothic language. Furthermore, Proto-Romance

Proto-Romance is the comparatively reconstructed ancestor of all Romance languages. It reflects a late variety of spoken Latin prior to regional fragmentation.

Phonology

Vowels

Monophthongs

Diphthong

The only phonemic diphthong was ...

and Middle Indic of the fourth century AD—contemporaneous with Gothic—were significantly simpler than Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

, respectively, and overall probably no more archaic than Gothic. In addition, some parts of the inflectional systems of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

were innovations that were not present in Proto-Indo-European.

General morphological features

Proto-Germanic had six cases, three genders, three numbers, three moods (indicative, subjunctive (PIE optative), imperative), and two voices (active and passive (PIE middle)). This is quite similar to the state of Latin, Greek, and Middle Indic of AD 200.

Nouns and adjectives were declined in (at least) six cases: vocative, nominative, accusative, dative, instrumental, genitive. The locative case had merged into the dative case, and the ablative may have merged with either the genitive, dative or instrumental cases. However, sparse remnants of the earlier locative and ablative cases are visible in a few pronominal and adverbial forms. Pronouns were declined similarly, although without a separate vocative form. The instrumental and vocative can be reconstructed only in the singular; the instrumental survives only in the West Germanic languages, and the vocative only in Gothic.

Verbs and pronouns had three numbers: singular, dual, and plural

The plural (sometimes abbreviated pl., pl, or ), in many languages, is one of the values of the grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than the default quantity represented by that noun. This de ...

. Although the pronominal dual survived into all the oldest languages, the verbal dual survived only into Gothic, and the (presumed) nominal and adjectival dual forms were lost before the oldest records. As in the Italic languages, it may have been lost before Proto-Germanic became a different branch at all.

Consonant and vowel alternations

Several sound changes occurred in the history of Proto-Germanic that were triggered only in some environments but not in others. Some of these were grammaticalised while others were still triggered by phonetic rules and were partially allophonic or surface filters.

Probably the most far-reaching alternation was between f, *þ, *s, *h, *hwand b, *d, *z, *g, *gw the voiceless and voiced fricatives, known as Grammatischer Wechsel and triggered by the earlier operation of Verner's law. It was found in various environments:

* In the person-and-number endings of verbs, which were voiceless in weak verbs and voiced in strong verbs.

* Between different grades of strong verbs. The voiceless alternants appeared in the present and past singular indicative, the voiced alternants in the remaining past tense forms.

* Between strong verbs (voiceless) and causative verbs derived from them (voiced).

* Between verbs and derived nouns.

* Between the singular and plural forms of some nouns.

Another form of alternation was triggered by the Germanic spirant law, which continued to operate into the separate history of the individual daughter languages. It is found in environments with suffixal -t, including:

* The second-person singular past ending *-t of strong verbs.

* The past tense of weak verbs with no vowel infix in the past tense.

* Nouns derived from verbs by means of the suffixes *-tiz, *-tuz, *-taz, which also possessed variants in -þ- and -d- when not following an obstruent.

An alternation not triggered by sound change was Sievers' law, which caused alternation of suffixal -j- and -ij- depending on the length of the preceding part of the morpheme. If preceded within the same morpheme by only short vowel followed by a single consonant, -j- appeared. In all other cases, such as when preceded by a long vowel or diphthong, by two or more consonants, or by more than one syllable, -ij- appeared. The distinction between morphemes and words is important here, as the alternant -j- appeared also in words that contained a distinct suffix that in turn contained -j- in its second syllable. A notable example was the verb suffix *-atjaną, which retained -j- despite being preceded by two syllables in a fully formed word.

Related to the above was the alternation between -j- and -i-, and likewise between -ij- and -ī-. This was caused by the earlier loss of -j- before -i-, and appeared whenever an ending was attached to a verb or noun with an -(i)j- suffix (which were numerous). Similar, but much more rare, was an alternation between -aV- and -aiC- from the loss of -j- between two vowels, which appeared in the present subjunctive of verbs: *-aų < *-ajų in the first person, *-ai- in the others. A combination of these two effects created an alternation between -ā- and -ai- found in class 3 weak verbs, with -ā- < -aja- < -əja- and -ai- < -əi- < -əji-.

I-mutation was the most important source of vowel alternation, and continued well into the history of the individual daughter languages (although it was either absent or not apparent in Gothic). In Proto-Germanic, only -e- was affected, which was raised by -i- or -j- in the following syllable. Examples are numerous:

* Verb endings beginning with -i-: present second and third person singular, third person plural.

* Noun endings beginning with -i- in u-stem nouns: dative singular, nominative and genitive plural.

* Causatives derived from strong verbs with a -j- suffix.

* Verbs derived from nouns with a -j- suffix.

* Nouns derived from verbs with a -j- suffix.

* Nouns and adjectives derived with a variety of suffixes including -il-, -iþō, -į̄, -iskaz, -ingaz.

Nouns

The system of nominal declensions was largely inherited from PIE. Primary nominal declensions were the stems in /a/, /ō/, /n/, /i/, and /u/. The first three were particularly important and served as the basis of adjectival declension; there was a tendency for nouns of all other classes to be drawn into them. The first two had variants in /ja/ and /wa/, and /jō/ and /wō/, respectively; originally, these were declined exactly like other nouns of the respective class, but later sound changes tended to distinguish these variants as their own subclasses. The /n/ nouns had various subclasses, including /ōn/ (masculine and feminine), /an/ (neuter), and /īn/ (feminine, mostly abstract nouns). There was also a smaller class of root nouns (ending in various consonants), nouns of relationship (ending in /er/), and neuter nouns in /z/ (this class was greatly expanded in German). Present participles, and a few nouns, ended in /nd/. The neuter nouns of all classes differed from the masculines and feminines in their nominative and accusative endings, which were alike.

Adjectives

Adjectives agree with the noun they qualify in case, number, and gender. Adjectives evolved into strong and weak declensions, originally with indefinite and definite meaning, respectively. As a result of its definite meaning, the weak form came to be used in the daughter languages in conjunction with demonstratives and definite articles. The terms "strong" and "weak" are based on the later development of these declensions in languages such as German and Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

, where the strong declensions have more distinct endings. In the proto-language, as in Gothic, such terms have no relevance. The strong declension was based on a combination of the nominal /a/ and /ō/ stems with the PIE pronominal endings; the weak declension was based on the nominal /n/ declension.

Determiners

Proto-Germanic originally had two demonstratives (proximal *''hi-''/''hei-''/''he-'' 'this', distal *''sa''/''sō''/''þat'' 'that') which could serve as both adjectives and pronouns. The proximal was already obsolescent in Gothic (e.g. Goth acc. ', dat. ', neut. ') and appears entirely absent in North Germanic. In the West Germanic languages, it evolved into a third-person pronoun, displacing the inherited ''*iz'' in the northern languages while being ousted itself in the southern languages (i.e. Old High German). This is the basis of the distinction between English ''him''/''her'' (with ''h-'' from the original proximal demonstrative) and German '/' (lacking ''h-'').

Ultimately, only the distal survived in the function of demonstrative. In most languages, it developed a second role as definite article

An article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" and "a(n)" a ...

, and underlies both the English determiners ''the'' and ''that''. In the North-West Germanic languages (but not in Gothic), a new proximal demonstrative ('this' as opposed to 'that') evolved by appending ''-si'' to the distal demonstrative (e.g. Runic Norse nom.sg. ''sa-si'', gen. ''þes-si'', dat. ''þeim-si''), with complex subsequent developments in the various daughter languages. The new demonstrative underlies the English determiners ''this'', ''these'' and ''those''. (Originally, ''these'', ''those'' were dialectal variants of the masculine plural of ''this''.)

Verbs

Proto-Germanic had only two tenses (past and present), compared to 5–7 in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, Proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium B.C. through the 6th ...

and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

. Some of this difference is due to deflexion, featured by a loss of tenses present in Proto-Indo-European. For example, Donald Ringe assumes for Proto-Germanic an early loss of the PIE imperfect aspect (something that also occurred in most other branches), followed by merging of the aspectual categories present-aorist and the mood categories indicative-subjunctive. (This assumption allows him to account for cases where Proto-Germanic has present indicative verb forms that look like PIE aorist subjunctives.)

However, many of the tenses of the other languages (e.g. future, future perfect, pluperfect, Latin imperfect) are not cognate with each other and represent separate innovations in each language. For example, the Greek future uses a ''-s-'' ending, apparently derived from a desiderative

In linguistics, a desiderative (abbreviated or ) form is one that has the meaning of "wanting to X". Desiderative forms are often verbs, derived from a more basic verb through a process of morphological derivation. Desiderative mood is a kind of ...

construction that in PIE was part of the system of derivational morphology (not the inflectional system); the Sanskrit future uses a ''-sy-'' ending, from a different desiderative verb construction and often with a different ablaut grade from Greek; while the Latin future uses endings derived either from the PIE subjunctive or from the PIE verb * "to be". Similarly, the Latin imperfect and pluperfect stem from Italic innovations and are not cognate with the corresponding Greek or Sanskrit forms; and while the Greek and Sanskrit pluperfect tenses appear cognate, there are no parallels in any other Indo-European languages, leading to the conclusion that this tense is either a shared Greek-Sanskrit innovation or separate, coincidental developments in the two languages. In this respect, Proto-Germanic can be said to be characterized by the failure to innovate new synthetic tenses as much as the loss of existing tenses. Later Germanic languages did innovate new tenses, derived through periphrastic

In linguistics, periphrasis () is the use of one or more function words to express meaning that otherwise may be expressed by attaching an affix or clitic to a word. The resulting phrase includes two or more collocated words instead of one in ...

constructions, with Modern English likely possessing the most elaborated tense system ("Yes, the house will still be being built a month from now"). On the other hand, even the past tense was later lost (or widely lost) in most High German dialects as well as in Afrikaans.

Verbs in Proto-Germanic were divided into two main groups, called " strong" and " weak", according to the way the past tense is formed. Strong verbs use ablaut

In linguistics, the Indo-European ablaut (, from German '' Ablaut'' ) is a system of apophony (regular vowel variations) in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

An example of ablaut in English is the strong verb ''sing, sang, sung'' and its ...

(i.e. a different vowel in the stem) and/or reduplication (derived primarily from the Proto-Indo-European perfect), while weak verbs use a dental suffix (now generally held to be a reflex of the reduplicated imperfect of PIE *''dʰeH1-'' originally "put", in Germanic "do"). Strong verbs were divided into seven main classes while weak verbs were divided into five main classes (although no attested language has more than four classes of weak verbs). Strong verbs generally have no suffix in the present tense, although some have a ''-j-'' suffix that is a direct continuation of the PIE ''-y-'' suffix, and a few have an ''-n-'' suffix or infix that continues the ''-n-'' infix of PIE. Almost all weak verbs have a present-tense suffix, which varies from class to class. An additional small, but very important, group of verbs formed their present tense from the PIE perfect (and their past tense like weak verbs); for this reason, they are known as preterite-present verbs. All three of the previously mentioned groups of verbs—strong, weak and preterite-present—are derived from PIE thematic verbs; an additional very small group derives from PIE athematic verbs, and one verb ''*wiljaną'' "to want" forms its present indicative from the PIE optative mood.

Proto-Germanic verbs have three moods: indicative, subjunctive and imperative. The subjunctive mood derives from the PIE optative mood. Indicative and subjunctive moods are fully conjugated throughout the present and past, while the imperative mood existed only in the present tense and lacked first-person forms. Proto-Germanic verbs have two voices, active and passive, the latter deriving from the PIE mediopassive

The mediopassive voice is a grammatical voice that subsumes the meanings of both the middle voice and the passive voice.

Description

Languages of the Indo-European family (and many others) typically have two or three of the following voices: acti ...

voice. The Proto-Germanic passive existed only in the present tense (an inherited feature, as the PIE perfect had no mediopassive). On the evidence of Gothic—the only Germanic language with a reflex of the Proto-Germanic passive—the passive voice had a significantly reduced inflectional system, with a single form used for all persons of the dual and plural. Note that although Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

(like modern Faroese and Icelandic) has an inflected mediopassive, it is not inherited from Proto-Germanic, but is an innovation formed by attaching the reflexive pronoun to the active voice.

Although most Proto-Germanic strong verbs are formed directly from a verbal root, weak verbs are generally derived from an existing noun, verb or adjective (so-called denominal, deverbal and deadjectival verbs). For example, a significant subclass of Class I weak verbs are (deverbal) causative verbs. These are formed in a way that reflects a direct inheritance from the PIE causative class of verbs. PIE causatives were formed by adding an accented suffix ''-éi̯e/éi̯o'' to the ''o''-grade of a non-derived verb. In Proto-Germanic, causatives are formed by adding a suffix ''-j/ij-'' (the reflex of PIE ''-éi̯e/éi̯o'') to the past-tense ablaut (mostly with the reflex of PIE ''o''-grade) of a strong verb (the reflex of PIE non-derived verbs), with Verner's Law

Verner's law describes a historical sound change in the Proto-Germanic language whereby consonants that would usually have been the voiceless fricatives , , , , , following an unstressed syllable, became the voiced fricatives , , , , . The law w ...

voicing applied (the reflex of the PIE accent on the ''-éi̯e/éi̯o'' suffix). Examples:

* ''*bītaną'' (class 1) "to bite" → ''*baitijaną'' "to bridle, yoke, restrain", i.e. "to make bite down"

* ''*rīsaną'' (class 1) "to rise" → ''*raizijaną'' "to raise", i.e. "to cause to rise"

* ''*beuganą'' (class 2) "to bend" → ''*baugijaną'' "to bend (transitive)"

* ''*brinnaną'' (class 3) "to burn" → ''*brannijaną'' "to burn (transitive)"

* ''*frawerþaną'' (class 3) "to perish" → ''*frawardijaną'' "to destroy", i.e. "to cause to perish"

* ''*nesaną'' (class 5) "to survive" → ''*nazjaną'' "to save", i.e. "to cause to survive"

* ''*ligjaną'' (class 5) "to lie down" → ''*lagjaną'' "to lay", i.e. "to cause to lie down"

* ''*faraną'' (class 6) "to travel, go" → ''*fōrijaną'' "to lead, bring", i.e. "to cause to go", ''*farjaną'' "to carry across", i.e. "to cause to travel" (an archaic instance of the ''o''-grade ablaut used despite the differing past-tense ablaut)

* ''*grētaną'' (class 7) "to weep" → ''*grōtijaną'' "to cause to weep"

* ''*lais'' (class 1, preterite-present) "(s)he knows" → ''*laizijaną'' "to teach", i.e. "to cause to know"

As in other Indo-European languages, a verb in Proto-Germanic could have a preverb