The presidency of Theodore Roosevelt started on September 14, 1901, when

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

became the

26th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

upon the

assassination of President William McKinley, and ended on March 4, 1909. Roosevelt had been the

vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

for only days when he succeeded to the presidency. A

Republican, he ran for and won by a landslide a four-year term in

1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library syst ...

. He was succeeded by his protégé and chosen successor,

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

.

A

Progressive reformer, Roosevelt earned a reputation as a "trust buster" through his regulatory reforms and

antitrust prosecutions. His presidency saw the passage of the

Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws which was enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administratio ...

, which established the

Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

to regulate food safety, and the

Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that expanded the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and gave it the power to set maximum railroad rates. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. ...

, which increased the regulatory power of the

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to elimina ...

. Roosevelt took care, however, to show that he did not disagree with

trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the "sett ...

and

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

in principle, but was only against

monopolistic practices. His "

Square Deal

The Square Deal was Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program, which reflected his three major goals: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection.

These three demands are often referred to as the "three Cs" ...

" included regulation of railroad rates and pure foods and drugs; he saw it as a fair deal for both the average citizen and the businessmen. Sympathetic to both business and labor, Roosevelt avoided labor strike, most notably negotiating a settlement to the great

Coal Strike of 1902. He vigorously promoted the

conservation movement

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the ...

, emphasizing efficient use of natural resources. He dramatically expanded the system of

national park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

s and

national forests. After 1906, he moved to the

left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album '' Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* ...

, denouncing the rich, attacking trusts, proposing a welfare state, and supporting labor unions.

In foreign affairs, Roosevelt sought to uphold the

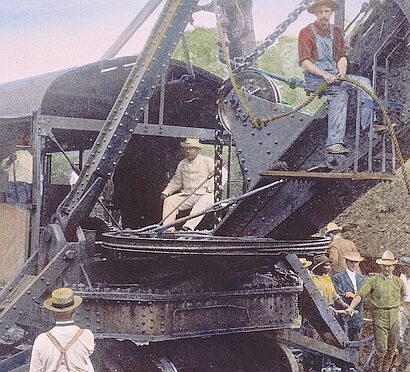

Monroe Doctrine and to establish the United States as a strong naval power, he took charge of building the

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

, which greatly increased access to the Pacific and increased American security interests and trade opportunities. He inherited the

colonial empire

A colonial empire is a collective of territories (often called colonies), either contiguous with the imperial center or located overseas, settled by the population of a certain state and governed by that state.

Before the expansion of early mode ...

acquired in the

Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

(1898). He ended the

United States Military Government in Cuba and committed to a long-term occupation of

the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. Much of his foreign policy focused on the threats posed by Japan in the Pacific and Germany in the

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexic ...

. Seeking to minimize European power in Latin America, he mediated the

Venezuela Crisis and declared the

Roosevelt Corollary. Roosevelt mediated the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

(1904–1905), for which he won the

1906 Nobel Peace Prize. He pursued closer relations with Great Britain. Biographer William Harbaugh argues:

:In foreign affairs, Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy is judicious support of the national interest and promotion of world stability through the maintenance of a balance of power; creation or strengthening of international agencies, and resort to their use when practicable; and implicit resolve to use military force, if feasible, to foster legitimate American interests. In domestic affairs, it is the use of government to advance the public interest. "If on this new continent," he said, "we merely build another country of great but unjustly divided material prosperity, we shall have done nothing."

Historian

Thomas Bailey Thomas or Tom Bailey may refer to:

Sports

* Tom Bailey (footballer) (1888–?), English footballer

* Thomas Bailey (footballer, born 1904) (1904–1983), Welsh footballer

* Tom Bailey (American football) (1949–2005), American football player

* T ...

, who generally disagreed with Roosevelt's policies, nevertheless concluded, "Roosevelt was a great personality, a great activist, a great preacher of the moralities, a great controversialist, a great showman. He dominated his era as he dominated conversations...the masses loved him; he proved to be a great popular idol and a great vote-getter." His image stands alongside George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln on

Mount Rushmore. Although Roosevelt has been criticized by some for his imperialism stance,

he is often ranked by historians among the top-five greatest U.S. presidents of all time.

Accession

Roosevelt served as

assistant secretary of the navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depa ...

and

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

before winning election as

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

's running mate in the

1900 presidential election. Roosevelt became president following the

assassination of McKinley by anarchist

Leon Czolgosz in

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

; Czolgosz shot McKinley on September 6, 1901, and McKinley died on September 14. Roosevelt was sworn into office on the day of McKinley's death at the

Ansley Wilcox House

Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site preserves the Ansley Wilcox House, at 641 Delaware Avenue in Buffalo, New York. Here, after the assassination of William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office as President of the ...

in Buffalo.

John R. Hazel, U.S. District Judge for the

Western District of

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, administered the

oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Suc ...

. At age 41, Roosevelt became the

youngest president in U.S. history, a distinction he still retains.

Roosevelt announced:

Roosevelt would later state that he came into office without any particular domestic policy goals. He broadly adhered to most Republican positions on economic issues, with the partial exception of the

protective tariff. Roosevelt had stronger views on the particulars of his foreign policy, as he wanted the United States to assert itself as a

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power i ...

in international relations.

Administration

Cabinet

Anxious to ensure a smooth transition, Roosevelt convinced the members of McKinley's cabinet, most notably Secretary of State

John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was U ...

and Secretary of the Treasury

Lyman J. Gage, to remain in office. Another holdover, Secretary of War

Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from ...

, had been a Roosevelt confidante for years, and he continued to serve as President Roosevelt's close ally. Attorney General

Philander C. Knox, who McKinley had appointed in early 1901, also emerged as a powerful force within the Roosevelt administration. McKinley's personal secretary,

George B. Cortelyou

George Bruce Cortelyou (July 26, 1862October 23, 1940) was an American Cabinet secretary of the early twentieth century. He held various positions in the presidential administrations of Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt.

...

, remained in place. Once Congress began its session in December 1901, Roosevelt replaced Gage with

L. M. Shaw

Leslie Mortier Shaw (November 2, 1848March 28, 1932) was an American businessman, lawyer, and politician. He served as the 17th Governor of Iowa and was a Republican candidate in the 1908 United States presidential election.

Biography

Shaw was b ...

and appointed

Henry C. Payne as Postmaster General, earning the approval of powerful Senators

William B. Allison and

John Coit Spooner

John Coit Spooner (January 6, 1843June 11, 1919) was a politician and lawyer from Wisconsin. He served in the United States Senate from 1885 to 1891 and from 1897 to 1907. A Republican, by the 1890s, he was one of the "Big Four" key Republicans ...

. He replaced Secretary of the Navy

John D. Long, with Congressman

William H. Moody

William Henry Moody (December 23, 1853 – July 2, 1917) was an American politician and jurist who held positions in all three branches of the Government of the United States. He represented parts of Essex County, Massachusetts in the ...

. In 1903, Roosevelt named Cortelyou as the first head of the Department of Commerce and Labor, and

William Loeb Jr. became Roosevelt's secretary.

Root returned to the private sector in 1904 and was replaced by

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, who had previously served as the

governor-general

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

of the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. Knox accepted appointment to the Senate in 1904 and was replaced by William Moody, who in turn was succeeded as attorney general by

Charles Joseph Bonaparte

Charles Joseph Bonaparte (; June 9, 1851June 28, 1921) was an American lawyer and political activist for progressive and liberal causes. Originally from Baltimore, Maryland, he served in the cabinet of the 26th U.S. president, Theodore Roosevel ...

in 1906. After Hay's death in 1905, Roosevelt convinced Root to return to the Cabinet as secretary of state, and Root remained in office until the final days of Roosevelt's tenure. In 1907, Roosevelt replaced Shaw with Cortelyou, while

James R. Garfield became the new secretary of the interior.

Press Corps

Building on McKinley's innovative and effective use of the press, Roosevelt made the White House the center of national news every day, providing interviews and photo opportunities. Noticing the reporters huddled outside in the rain one day, he gave them their own room inside, effectively inventing the presidential press briefing.

The grateful press, with unprecedented access to the White House, rewarded Roosevelt with ample coverage, rendered the more possible by Roosevelt's practice of screening out reporters he did not like.

Judicial appointments

Roosevelt appointed three

associate justices of the

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

. Roosevelt's first appointment,

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. had served as chief justice of the

Massachusetts Supreme Court since 1899. Confirmed in December 1902, Holmes served on the Supreme Court until 1932. Some of Holmes's antitrust decisions angered Roosevelt and they stopped being friends. Roosevelt's second appointment, former Secretary of State

William R. Day

William Rufus Day (April 17, 1849 – July 9, 1923) was an American diplomat and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1903 to 1922. Prior to his service on the Supreme Court, Day served as Unit ...

, became a reliable vote for Roosevelt's antitrust prosecutions and remained on the court from 1903 to 1922. In 1906, after considering Democratic appellate judge

Horace Harmon Lurton

Horace Harmon Lurton (February 26, 1844 – July 12, 1914) was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and previously was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and of th ...

for a Supreme Court vacancy, Roosevelt instead appointed Attorney General William Moody. Moody served until health problems forced his retirement in 1910.

Roosevelt also appointed 71 other federal judges: 18 to the

United States Courts of Appeals

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. The courts of appeals are divided into 11 numbered circuits that cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals f ...

, and 53 to the

United States district courts. These nominations were prepared by the Justice Department, in consultation with Republican leaders, especially senators from the home state. The average age of the appointees was 50.7 years, with 22 percent younger than 45.

Domestic policy

Progressivism

Roosevelt was deeply immersed in the ethos of the

Progressive era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

and was determined to create what he called a "

Square Deal

The Square Deal was Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program, which reflected his three major goals: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection.

These three demands are often referred to as the "three Cs" ...

" of efficiency and opportunity for every citizen. Roosevelt pushed several pieces of progressive legislation through Congress. Progressivism was the dominant force of the day, and Roosevelt was its most articulate spokesperson. Progressivism had dual aspects. First, progressivism promoted use of science, engineering, technology, and social sciences to address the nation's problems, and identify ways to eliminate waste and inefficiency and promote modernization. Those promoting progressivism also campaigned against corruption among political machines, labor unions, and trusts of new, large corporations, which emerged at the turn of the century. In describing Roosevelt's priorities and characteristics as president, historian G. Warren Chessman noted Roosevelt's

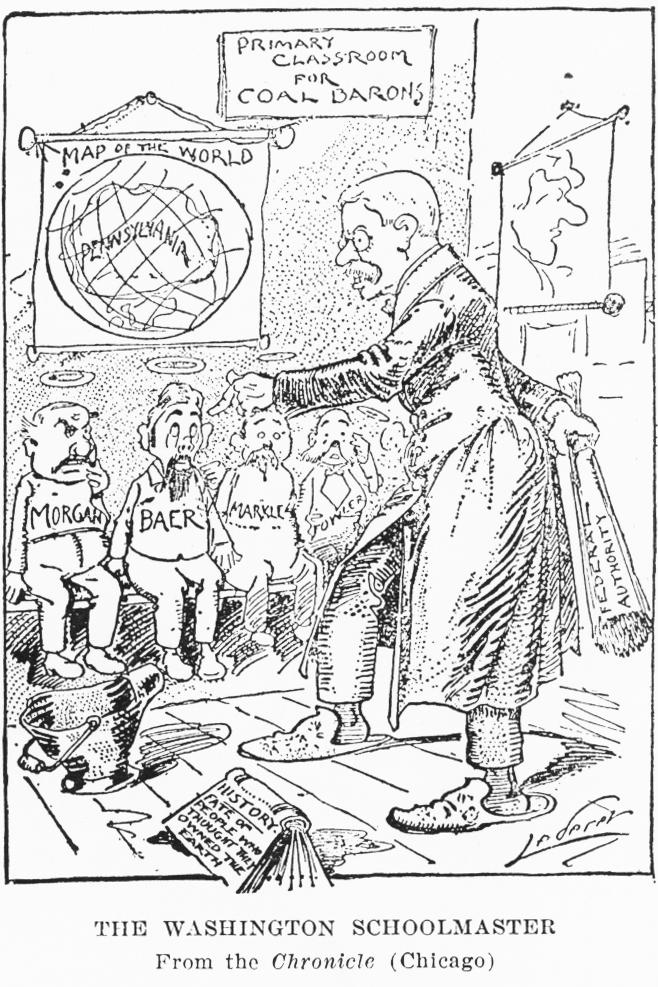

Trust busting and regulation

Public attention focused on the trusts--economic monopolies--typically blamed for raising inflation. Roosevelt seized the issue and became identified as the "trusty buster," although he typically wanted to regulate the trusts rather than break them up. In the 1890s many large businesses, most notoriously

Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co- ...

, had bought out their rivals or had established business arrangements that effectively stifled competition. Many companies followed the model of Standard Oil, which organized itself as a

trust in which several component corporations were controlled by one

board of directors. While Congress had passed the 1890

Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

...

to make illegal some moves toward monopoly, the Supreme Court had limited the power of the act in the case of ''

United States v. E. C. Knight Co.

''United States v. E. C. Knight Co.'', 156 U.S. 1 (1895), also known as the "Sugar Trust Case," was a United States Supreme Court antitrust case that severely limited the federal government's power to pursue antitrust actions under the Sherman Ant ...

''. By 1902, the 100 largest corporations held control of 40 percent of industrial capital in the United States. Roosevelt did not oppose all trusts, but sought to regulate trusts that he believed harmed the public, which he labeled as "bad trusts." According to Leroy Dorsey, Roosevelt told voters that corporations were needed in modern America (and Muckrakers should cool their angry exaggerations). Roosevelt then took the role of moral guardian and advised corporate executives they must adhere to ethical standards. He told them business could be effectively conducted only in terms of a sense of morality and a spirit of public service.

First term

Upon taking office, Roosevelt proposed new federal regulation of trusts. As the states had not prevented the growth of what he viewed as harmful trusts, Roosevelt advocated the creation of Cabinet department designed to regulate corporations engaged in

interstate commerce

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amo ...

. He also favored amending the

Interstate Commerce Act of 1887

The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 is a United States federal law that was designed to regulate the railroad industry, particularly its monopolistic practices. The Act required that railroad rates be "reasonable and just," but did not empower ...

, which had failed to prevent the consolidation of railroads. In February 1902, the Justice Department announced that it would file an antitrust suit against the

Northern Securities Company, a railroad

holding company

A holding company is a company whose primary business is holding a controlling interest in the securities of other companies. A holding company usually does not produce goods or services itself. Its purpose is to own shares of other companies ...

that had been formed in 1901 by

J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known ...

,

James J. Hill, and

E. H. Harriman. As the Justice Department lacked an antitrust division, Attorney General Knox, a former corporate lawyer, personally led the suit. While the case was working its way through court, Knox filed another case against the "Beef Trust," which had become unpopular due to rising meat prices. Combined with his earlier rhetoric, the suits signaled Roosevelt's resolve to strengthen the federal regulation of trusts.

After the 1902 elections, Roosevelt called for a ban on railroad rebates to large industrial concerns, as well as for the creation of a

Bureau of Corporations to study and report on monopolistic practices. To pass his antitrust package through Congress, Roosevelt appealed directly to the people, casting the legislation as a blow against the malevolent power of Standard Oil. Roosevelt's campaign proved successful, and he won congressional approval of the creation of the

Department of Commerce and Labor, which included the

Bureau of Corporations. The Bureau of Corporations was designed to monitor and report on anti-competitive practices; Roosevelt believed that large companies would be less likely to engage in anti-competitive practices if such practices were publicized. At Knox's request, Congress also authorized the creation of the

Antitrust Division

The United States Department of Justice Antitrust Division is a division of the U.S. Department of Justice that enforces U.S. antitrust law. It has exclusive jurisdiction over U.S. federal criminal antitrust prosecutions. It also has jurisdict ...

of the Department of Justice. Roosevelt also won passage of the

Elkins Act, which restricted the granting of railroad rebates.

In March 1904, the Supreme Court ruled for the government in the case of ''

Northern Securities Co. v. United States

''Northern Securities Co. v. United States'', 193 U.S. 197 (1904), was a case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1903. The Court ruled 5-4 against the stockholders of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroad companies, which had essential ...

''. According to historian

Michael McGerr, the case represented the federal government's first victorious prosecution of a "single, tightly integrated interstate corporation." The following year, the administration won another major victory in

Swift and Company v. United States

''Swift & Co. v. United States'', 196 U.S. 375 (1905), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Commerce Clause allowed the federal government to regulate monopolies if it has a direct effect on commerce. It marked the s ...

, which broke up the Beef Trust. The evidence at trial demonstrated that, prior to 1902, the "Big Six" leading meatpackers had engaged in a conspiracy to fix prices and divide the market for livestock and meat in their quest for higher prices and higher profits. They blacklisted competitors who failed to go along, used false bids, and accepted rebates from the railroads. After they were hit with federal injunctions in 1902, the Big Six had merged into one company, allowing them to continue to control the trade internally. Speaking for the unanimous court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. held that interstate commerce included actions that were part of the chain where the chain was clearly interstate in character. In this case, the chain ran from farm to retail store and crossed many state lines.

Second term

Following his re-election, Roosevelt sought to quickly enact a bold legislative agenda, focusing especially on legislation that would build upon the regulatory accomplishments of his first term. Events during his first term had convinced Roosevelt that legislation enacting additional federal regulation of interstate commerce was necessary, as the states were incapable of regulating large trusts that operated across state lines and the overworked Department of Justice was unable to provide an adequate check on monopolistic practices through antitrust cases alone. Roused by reports in

McClure's Magazine, many Americans joined Roosevelt in calling for an enhancement to the Elkins Act, which had done relatively little to restrict the granting of railroad rebates. Roosevelt also sought to strengthen the powers of the

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to elimina ...

(ICC), which had been created in 1887 to regulate railroads. Roosevelt's call for regulatory legislation, published in his 1905 message to Congress, encountered strong opposition from business interests and conservative congressmen.

When Congress reconvened in late 1905, Roosevelt asked Senator

Jonathan P. Dolliver

Jonathan Prentiss Dolliver (February 6, 1858October 15, 1910) was a Republican orator, U.S. Representative, then U.S. Senator from Iowa at the turn of the 20th century.Thomas Richard Ross, ''Jonathan Prentiss Dolliver: A Study in Political Int ...

of Iowa to introduce a bill that would incorporate Roosevelt's railroad regulatory proposals, and set about mobilizing public and congressional support for the bill. The bill was also taken up in the House, where it became known as the Hepburn Bill, named after Congressman

William Peters Hepburn

William Peters Hepburn (November 4, 1833 – February 7, 1916) was an American Civil War officer and an eleven-term Republican congressman from Iowa's now-obsolete 8th congressional district, serving from 1881 to 1887, and from 1893 to 1909. ...

. While the bill passed the House with relative ease, the Senate, dominated by conservative Republicans like

Nelson Aldrich

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich (/ ˈɑldɹɪt͡ʃ/; November 6, 1841 – April 16, 1915) was a prominent American politician and a leader of the Republican Party in the United States Senate, where he represented Rhode Island from 1881 to 1911. By the ...

, posed a greater challenge. Seeking to defeat reform efforts, Aldrich arranged it so that Democrat

Benjamin Tillman

Benjamin Ryan Tillman (August 11, 1847 – July 3, 1918) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who served as governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and as a United States Senator from 1895 until his death in 1918. A whi ...

, a Southern senator who Roosevelt despised, was left in charge of the bill. Because railroad regulation was widely popular, opponents of the Hepburn Bill focused on the role of courts in reviewing the ICC's rate-setting. Roosevelt and progressives wanted to limit judicial review to issues of procedural fairness, while conservatives favored

"broad review" that would allow judges to determine whether the rates themselves were fair.

After Roosevelt and Tillman were unable to assemble a bipartisan majority behind a bill that restricted judicial review, Roosevelt accepted an amendment written by Senator Allison that contained vague language allowing for court review of the ICC's rate-setting power. With the inclusion of the Allison amendment, the Senate passed the Hepburn Bill in a 71-to-3 vote. After both houses of Congress passed a uniform law, Roosevelt signed the

Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that expanded the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and gave it the power to set maximum railroad rates. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. ...

into law on June 29, 1906. In addition to rate-setting, the Hepburn Act also granted the ICC regulatory power over pipeline fees, storage contracts, and several other aspects of railroad operations. Though some conservatives believed that the Allison amendment had granted broad review powers to the courts, a subsequent Supreme Court case limited judicial power to review the ICC's rate-setting powers.

In response to public clamor largely arising from the popularity of

Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

's novel, ''

The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'', Roosevelt also pushed Congress to enact food safety regulations. Opposition to a meat inspection bill was strongest in the House, due to the presence of conservative Speaker of the House

Joseph Gurney Cannon and allies of the meatpacking industry. Roosevelt and Cannon agreed to a compromise bill that became the

Meat Inspection Act of 1906. Congress simultaneously passed the

Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws which was enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administratio ...

, which received strong support in both the House and the Senate. Collectively, the laws provided for the labeling of foods and drugs and the inspection of livestock, and mandated sanitary conditions at meatpacking plants.

Seeking to bolster antitrust regulations, Roosevelt and his allies introduced a bill to enhance the Sherman Act in 1908, but it was defeated in Congress. In the aftermath of a series of scandals involving major

insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

companies, Roosevelt sought to establish a National Bureau of Insurance to provide federal regulation, but this proposal was also defeated. Roosevelt continued to launch antitrust suits in his second term, and a suit against Standard Oil in 1906 would lead to that company's break-up in 1911. In addition to the antitrust suits and major regulatory reform efforts, the Roosevelt administration also won the cooperation of many large trusts, who consented to regulation by the Bureau of Corporations. Among the companies that voluntarily agreed to regulation was

U.S. Steel, which avoided an antitrust suit by allowing the Bureau of Corporations to investigate its operations.

Conservation

Roosevelt was a prominent

conservationist, putting the issue high on the national agenda. Roosevelt's conservation efforts were aimed not just at environment protection, but also at ensuring that society as a whole, rather than just select individuals or companies, benefited from the country's natural resources. His key adviser and subordinate on environmental matters was

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

, the head of the Bureau of Forestry. Roosevelt increased Pinchot's power over environmental issues by transferring control over

national forests from the Department of the Interior to the Bureau of Forestry, which was part of the Agriculture Department. Pinchot's agency was renamed to the

United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 154 United States National Forest, national forests and 20 United States Nationa ...

, and Pinchot presided over the implementation of assertive conservationist policies in national forests.

Roosevelt encouraged the

Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902, which promoted federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed 230 million acres (360,000 mi

2 or 930,000 km

2) under federal protection. In 1906, Congress passed the

Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act of 1906 (, , ), is an act that was passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt on June 8, 1906. This law gives the President of the United States the authority to, by presidential pro ...

, granting the president the power to create

national monuments in federal lands. Roosevelt set aside more federal land,

national park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

s, and

nature preserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

s than all of his predecessors combined.

[W. Todd Benson, ''President Theodore Roosevelt's Conservations Legacy'' (2003)] Roosevelt established the

Inland Waterways Commission

The Inland Waterways Commission was created by Congress in March 1907, at the request of President Theodore Roosevelt, to investigate the transportation crisis that recently had affected nation's ability to move its produce and industrial producti ...

to coordinate construction of water projects for both conservation and transportation purposes, and in 1908 he hosted the

Conference of Governors

The Conference of Governors was held in the White House May 13–15, 1908 under the sponsorship of President Theodore Roosevelt. Gifford Pinchot, at that time Chief Forester of the U.S., was the primary mover of the conference, and a progressive c ...

. This was the first time governors had ever met together and the goal was to boost and coordinate support for conservation. Roosevelt then established the

National Conservation Commission

The National Conservation Commission was appointed on June 8, 1908 by Theodore Roosevelt, President Theodore Roosevelt and consisted of representatives of the United States Congress and relevant executive agency technocrats; Gifford Pinchot served ...

to take an inventory of the nation's natural resources.

Roosevelt's policies faced opposition from both environmental activists like

John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologis ...

and opponents of conservation like Senator

Henry M. Teller of Colorado. While Muir, the founder of the

Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an environmental organization with chapters in all 50 United States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by Scottish-American preservationist John Muir, who b ...

, wanted nature preserved for the sake of pure beauty, Roosevelt subscribed to Pinchot's formulation, "to make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees." Teller and other opponents of conservation, meanwhile, believed that conservation would prevent the economic development of the West and feared the centralization of power in Washington. The backlash to Roosevelt's ambitious policies prevented further conservation efforts in the final years of Roosevelt's presidency and would later contribute to the

Pinchot–Ballinger controversy

The Pinchot–Ballinger controversy, also known as the "Ballinger Affair", was a dispute between U.S. Forest Service Chief Gifford Pinchot and U.S. Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger that contributed to the split of the Republican Part ...

during the Taft administration.

Labor relations

Roosevelt was generally reluctant to involve himself in labor-management disputes, but he believed that presidential intervention was justified when such disputes threatened the public interest. Labor union membership had doubled in the five years preceding Roosevelt's inauguration, and at the time of his accession, Roosevelt saw labor unrest as the greatest potential threat facing the nation. Yet he also sympathized with many laborers due to the harsh conditions that many faced. Resisting the more extensive reforms proposed by labor leaders such as

Samuel Gompers of the

American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

(AFL), Roosevelt established the

open shop

An open shop is a place of employment at which one is not required to join or financially support a union ( closed shop) as a condition of hiring or continued employment.

Open shop vs closed shop

The major difference between an open and closed ...

as the official policy for civil service employees.

In 1899, the

United Mine Workers

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unite ...

(UMW) had expanded its influence from

bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the seams. It ...

mines to

anthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the hig ...

coal mines. The UMW organized an

anthracite coal strike in May 1902, seeking an

eight-hour day and pay increases. Hoping to reach a negotiated solution with the help of

Mark Hanna's

National Civic Federation, UMW president

John Mitchell prevented bituminous coal miners from launching a

sympathy strike

Solidarity action (also known as secondary action, a secondary boycott, a solidarity strike, or a sympathy strike) is industrial action by a trade union in support of a strike initiated by workers in a separate corporation, but often the same en ...

. The mine owners, who wanted to crush the UMW, refused to negotiate, and the strike continued. In the ensuing months, the price of coal increased from five dollars per ton to above fifteen dollars per ton. Seeking to help the two parties arrive at a solution, Roosevelt hosted the UMW leaders and mine operators at the White House in October 1902, but the mine owners refused to negotiate. Through the efforts of Roosevelt, Root, and J.P. Morgan, the mine operators agreed to the establishment of a presidential commission to propose a solution to the strike. In March 1903, the commission mandated pay increases and a reduction in the workday from ten hours to nine hours. At the insistence of the mine owners, the UMW was not granted official recognition as the representative of the miners.

Roosevelt refrained from major interventions in labor disputes after 1902, but state and federal courts increasingly became involved, issuing

injunction

An injunction is a legal and equitable remedy in the form of a special court order that compels a party to do or refrain from specific acts. ("The court of appeals ... has exclusive jurisdiction to enjoin, set aside, suspend (in whole or in p ...

s to prevent labor actions. Tensions were particularly high in Colorado, where the

Western Federation of Miners led a series of strikes that became part of a struggle known as the

Colorado Labor Wars. Roosevelt did not intervene in the Colorado Labor Wars, but Governor

James Hamilton Peabody dispatched the Colorado National Guard to crush the strikes. In 1905, radical union leaders like

Mary Harris Jones and

Eugene V. Debs established the

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW), which criticized the conciliatory policies of the AFL.

Civil rights

Although Roosevelt did some work improving race relations, he, like most leaders of the

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

, lacked initiative on most racial issues.

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

, the most important black leader of the day, was the first African American to be invited to

dinner at the White House, dining there on October 16, 1901.

Washington, who had emerged as an important adviser to Republican politicians in the 1890s, favored accommodation with the

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

that instituted

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

. News of the dinner reached the press two days later, and public outcry from whites was so strong, especially from the Southern states, that Roosevelt never repeated the experiment.

[Brands, ''TR'' (1999) pp 421–426] Nonetheless, Roosevelt continued to consult Washington regarding appointments and shunned the "

lily-white" Southern Republicans who favored excluding blacks from office.

After the highly controversial dinner with Washington, Roosevelt continued to speak out against

lynchings

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

, but did little to advance the cause of African-American civil rights. He reduced the number of blacks holding federal patronage. In 1906, he approved the dishonorable discharges of three companies of black soldiers who all refused his direct order to testify regarding their actions during a violent episode in

Brownsville, Texas

Brownsville () is a city in Cameron County in the U.S. state of Texas. It is on the western Gulf Coast in South Texas, adjacent to the border with Matamoros, Mexico. The city covers , and has a population of 186,738 as of the 2020 census. I ...

, known as the

Brownsville affair Roosevelt was widely criticized by Northern newspapers for the discharges, and Republican Senator

Joseph B. Foraker

Joseph Benson Foraker (July 5, 1846 – May 10, 1917) was an American politician of the Republican Party who served as the 37th governor of Ohio from 1886 to 1890 and as a United States senator from Ohio from 1897 until 1909.

Foraker was ...

won passage of a congressional resolution directing the administration to turn over all documents related to the case. The controversy hung over the remainder of his presidency, although the Senate eventually concluded that the dismissals had been justified.

Panic of 1907

In 1907, Roosevelt faced the greatest domestic economic crisis since the

Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

. The U.S.

stock market

A stock market, equity market, or share market is the aggregation of buyers and sellers of stocks (also called shares), which represent ownership claims on businesses; these may include ''securities'' listed on a public stock exchange, ...

entered a slump in early 1907, and many in the financial markets blamed Roosevelt's regulatory policies for the decline in stock prices. Lacking a strong

central banking system, the government was unable to coordinate a response to the economic downturn. The slump reached a full-blown panic in October 1907, when two investors failed to take over

United Copper. Working with Secretary of the Treasury Cortelyou, financier J.P. Morgan organized a group of businessmen to avert a crash by pledging their own money. Roosevelt aided Morgan's intervention by allowing U.S. Steel to acquire the

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (1852–1952), also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based entirely with ...

despite antitrust concerns, and by authorizing Cortelyou to raise bonds and commit federal funds to the banks. Roosevelt's reputation in

Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for ...

fell to new lows following the panic, but the president remained broadly popular. In the aftermath of the panic, most congressional leaders agreed on the need to reform the nation's financial system. With the support of Roosevelt, Senator Aldrich introduced a bill to allow

National Banks to issue emergency currency, but his proposal was defeated by Democrats and progressive Republicans who believed that it was overly favorable to Wall Street. Congress instead passed the

Aldrich–Vreeland Act, which created the

National Monetary Commission to study the nation's banking system; the commission's recommendations would later form the basis of the

Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after ...

.

Roosevelt exploded in anger at the super-rich for the economic malfeasance, calling them "malefactors of great wealth." In a major speech in August entitled, "The Puritan Spirit and the Regulation of Corporations." Trying to restore confidence, he blamed the crisis primarily on Europe, but then, after saluting the unbending rectitude of the Puritans, he went on:

It may well be that the determination of the government...to punish certain malefactors of great wealth, has been responsible for something of the trouble; at least to the extent of having caused these men to combine to bring about as much financial stress as possible, in order to discredit the policy of the government and thereby secure a reversal of that policy, so that they may enjoy unmolested the fruits of their own evil-doing.

Regarding the very wealthy, Roosevelt privately scorned, "their entire unfitness to govern the country, and...the lasting damage they do by much of what they think are the legitimate big business operations of the day."

Tariffs

High tariffs had always been Republican Party orthodoxy. However, the western elements wanted lower tariffs on industrial products while keeping rates high on farm products. Democrats had a powerful campaign issue to the effect that high tariffs enriched big business and hurt consumers; they wanted to sharply lower rates and impose an income tax on the rich. Roosevelt realized the political dilemma and avoided or postponed the tariff issue for his entire presidency; it exploded under his successor and hurt Taft badly. The tariff protected domestic manufacturing against foreign competition, and kept wages high in American factories, thus attracting immigrants. Its taxes on imports produced over one-third of federal revenue in 1901. McKinley had been a committed protectionist, and the

Dingley Tariff

The Dingley Act of 1897 (ch. 11, , July 24, 1897), introduced by U.S. Representative Nelson Dingley Jr., of Maine, raised tariffs in United States to counteract the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894, which had lowered rates. The bill came into ...

of 1897 represented a major increase in tariff rates. McKinley also negotiated bilateral reciprocity treaties with France, Argentina, and other countries in an attempt to expand foreign trade while still keeping overall tariff rates high. Unlike all other previous Republican presidents, Roosevelt had never been a strong advocate of the protective tariff, nor did he place a high emphasis on tariffs in general. When Roosevelt took office, McKinley's reciprocity treaties were pending before the Senate, and many assumed that they would be ratified despite the opposition of Aldrich and other conservatives. After conferring with Aldrich, Roosevelt decided not to push Senate ratification of the treaties in order to avoid an intra-party conflict. He did, however, achieve some minor changes, such as reciprocal tariff treaties with the Philippines and, after overcoming domestic sugar interests, with Cuba.

The issue of the tariff lay dormant throughout Roosevelt's first term, but it continued to be an important campaign topic for both parties. Proponents of tariff reduction asked Roosevelt to call a special session of Congress to address the issue in early 1905, but Roosevelt was only willing to issue a cautious endorsement of a cut in tariff rates, and no further action was taken on the tariff during Roosevelt's tenure. In the first decade of the 20th century, the country experienced a period of sustained

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

for the first time since the early 1870s, and Democrats and other free trade advocates blamed rising prices on high tariff rates. Tariff reduction became an increasingly important national issue, and Congress would pass a major tariff law in 1909, shortly after Roosevelt left office.

Move to Left Center, 1907–1909

By 1907, Roosevelt identified himself with the "left center" of the Republican Party. He explained his balancing act:

:Again and again in my public career I have had to make head against mob spirit, against the tendency of poor, ignorant and turbulent people who feel a rancorous jealousy and hatred of those who are better off. But during the last few years it has been the wealthy corruptionists of enormous fortune, and of enormous influence through their agents of the press, pulpit, colleges and public life, with whom I've had to wage bitter war."

Growing popular outrage at corporate scandals, along with reporting of muckraking journalists like

Lincoln Steffens and

Ida Tarbell, contributed to a split in the Republican Party between conservatives like Aldrich and progressives like

Albert B. Cummins and

Robert M. La Follette. Roosevelt did not fully embrace the left wing of his party, but he adopted many of their proposals.

In his last two years in office, Roosevelt abandoned his cautious approach toward big business, lambasting his conservative critics and calling on Congress to enact a series of radical new laws. Roosevelt sought to replace the

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

economic environment with a new economic model which included a larger regulatory role for the federal government. He believed that 19th-century entrepreneurs had risked their fortunes on innovations and new businesses, and that these capitalists had been rightly rewarded. By contrast, he believed that 20th-century capitalists risked little but nonetheless reaped huge and unjust, economic rewards. Without a redistribution of wealth away from the upper class, Roosevelt feared that the country would turn to radicalism or fall to revolution.

In January 1908, Roosevelt sent a special message to Congress, calling for the restoration of an

employer's liability law, which had recently been struck down by the Supreme Court due to its application to intrastate corporations. He also called for a national

incorporation law (all corporations had state charters, which varied greatly state by state), a

federal income tax and

inheritance tax

An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and property) of a person who has died.

International tax law distinguishes between an e ...

(both targeted at the rich), limits on the use of court

injunction

An injunction is a legal and equitable remedy in the form of a special court order that compels a party to do or refrain from specific acts. ("The court of appeals ... has exclusive jurisdiction to enjoin, set aside, suspend (in whole or in p ...

s against labor unions during strikes (injunctions were a powerful weapon that mostly helped business), an

eight-hour work day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 1 ...

for federal employees, a

postal savings system (to provide competition for local banks), and legislation barring corporations from contributing to political campaigns.

Roosevelt's increasingly radical stance proved popular in the Midwest and Pacific Coast, and among farmers, teachers, clergymen, clerical workers and some proprietors, but appeared as divisive and unnecessary to eastern Republicans, corporate executives, lawyers, party workers, and many members of Congress.

[Mowry (1954)] Populist Democrats such as William Jennings Bryan expressed admiration for Roosevelt's message, and one Southern newspaper called for Roosevelt to run as a Democrat in 1908, with Bryan as his running mate. Despite the public support offered by Democratic congressional leaders like

John Sharp Williams

John Sharp Williams (July 30, 1854September 27, 1932) was a prominent American politician in the Democratic Party from the 1890s through the 1920s, and served as the Minority Leader of the United States House of Representatives from 1903 to 1908 ...

, Roosevelt never seriously considered leaving the Republican Party during his presidency. Roosevelt's move to the left was supported by some congressional Republicans and many in the public, but conservative Republicans such as Senator Nelson Aldrich and Speaker

Joseph Gurney Cannon remained in control of Congress.

[Morris (2001) pp. 510–511] These Republican leaders blocked the more ambitious aspects of Roosevelt's agenda, though Roosevelt won passage of a new

Federal Employers Liability Act and other laws, such as a restriction of child labor in Washington, D.C.

States admitted

One new state,

Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New ...

, was

admitted to the Union while Roosevelt was in office. Oklahoma, which was formed out of

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

and

Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as t ...

, became the 46th state on November 16, 1907. The

Oklahoma Enabling Act also contained provisions encouraging

New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomin ...

and

Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state o ...

to begin the process of gaining admission as states.

Foreign policy

Foreign-policy became a tug-of-war between Roosevelt and Secretary of State

John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was U ...

, one of the most prestigious Republicans of the older generation. Roosevelt garnered most of the publicity, but in practice Hay handled both routine and ceremonial affairs and had a strong voice shaping policy. he was in very bad health starting in 1903. After Hay died in 1905, Roosevelt named

Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from ...

, who had been serving as Secretary of War.

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

became Secretary of War. Roosevelt personally handled all the major issues. Apart from his close friend Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, Roosevelt seldom dealt with senators on matters of foreign policy.

Big Stick diplomacy

Roosevelt was adept at coining clever phrases to concisely summarize his policies. "Big stick" was his catch phrase for his hard pushing foreign policy: "Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far." Roosevelt described his style as "the exercise of intelligent forethought and of decisive action sufficiently far in advance of any likely crisis." As practiced by Roosevelt, big stick diplomacy had five components. First it was essential to possess serious military capabilities that force the adversary to pay close attention. At the time that meant a world-class navy. Roosevelt never had a large army at his disposal. The other qualities were to act justly toward other nations, never to bluff, to strike only if prepared to strike hard, and the willingness to allow the adversary to save face in defeat.

Great power politics

Victory over Spain had made the United States a power in both the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. It was already the largest economic power. Roosevelt was determined to continue the expansion of American influence, stating in his 1905 Inaugural Address:

We have become a great nation, forced by the fact of its greatness into relations with the other nations of the earth, and we must behave as beseems a people with such responsibilities. Toward all other nations, large and small, our attitude must be one of cordial and sincere friendship. We must show not only in our words, but in our deeds, that we are earnestly desirous of securing their good will by acting toward them in a spirit of just and generous recognition of all their rights....No weak nation that acts manfully and justly should ever have cause to fear us, and no strong power should ever be able to single us out as a subject for insolent aggression.

Roosevelt saw a duty to uphold a

balance of power in international relations and seek to reduce tensions. He was also adamant in upholding the

Monroe Doctrine, the American policy of opposing

European colonialism

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense began ...

in the Western Hemisphere. Roosevelt viewed the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

as the biggest potential threat, and strongly opposed any German base in the

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexic ...

. He responded skeptically to German Kaiser

Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

's efforts to curry favor with the United States. Roosevelt also attempted to expand U.S. influence in

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

and the Pacific, where the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

and the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

were rivals trying to expand their role in Korea and China. He kept an important aspect of McKinley's rhetoric in East Asia: the

Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

calling for keeping the Chinese economy open to trade from all countries.

To gain visibility in European affairs Roosevelt helped organize that

Algeciras Conference

The Algeciras Conference of 1906 took place in Algeciras, Spain, and lasted from 16 January to 7 April. The purpose of the conference was to find a solution to the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905 between France and Germany, which arose as German ...

that temporarily resolved the Moroccan crisis of 1905–1906. France and Britain had agreed that France would dominate Morocco, but Germany suddenly protested aggressively. Berlin asked Roosevelt to help and he facilitated an agreement among the powers in April, 1906. Germany gained nothing of importance but was mollified for a while until it instigated the even worse

Agadir Crisis of 1912.

Aftermath of the Spanish–American War

Philippines

Americans heatedly debated the status of the new territories. Roosevelt believed that Cuba should be quickly granted independence and that

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

should remain a semi-autonomous possession under the terms of the

Foraker Act

The Foraker Act, , officially known as the Organic Act of 1900, is a United States federal law that established civilian (albeit limited popular) government on the island of Puerto Rico, which had recently become a possession of the United State ...

. He wanted U.S. forces to remain in the Philippines to establish a stable, democratic government, even in the face of an

insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

led by

Emilio Aguinaldo

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (: March 22, 1869February 6, 1964) was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who is the youngest president of the Philippines (1899–1901) and is recognized as the first president of the Philippine ...

. Roosevelt feared that a quick U.S. withdrawal would lead to instability in the Philippines or a takeover by Germany.

The Filipino insurrection largely

in 1902 and the insurgents accepted American rule. However trouble continued in the remote southern areas, where the Muslim

Moros

In Greek mythology, Moros /ˈmɔːrɒs/ or Morus /ˈmɔːrəs/ (Ancient Greek: Μόρος means 'doom, fate') is the 'hateful' personified spirit of impending doom, who drives mortals to their deadly fate. It was also said that Moros gave peop ...

resisted American rule as they had resisted the Spanish. This was the

Moro Rebellion

The Moro Rebellion (1899–1913) was an armed conflict between the Moro people and the United States military during the Philippine–American War.

The word "Moro" – the Spanish word for "Moor" – is a term for Muslim people who l ...

. To resolve religious tensions, and eliminate the last Spanish presence, Roosevelt continued the McKinley policies of buying out the Catholic friars and returning them to Spain (with compensation to the

Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

).

Modernizing the Philippines was a high priority. He invested heavily in upgrading the infrastructure, introducing public health programs, and launching economic and social modernization. His enthusiasm shown in 1898-99 for colonies cooled off, and Roosevelt saw the islands as "our heel of Achilles." He told Taft in 1907, "I should be glad to see the islands made independent, with perhaps some kind of international guarantee for the preservation of order, or with some warning on our part that if they did not keep order we would have to interfere again." By then the president and his foreign policy advisers turned away from Asian issues to concentrate on Latin America, and Roosevelt redirected Philippine policy to prepare the islands to become the first Western colony in Asia to achieve self-government. Though most Filipino leaders favored independence, some minority groups, especially the Chinese who controlled much of local business, wanted to stay under American rule indefinitely.

The Philippines was a major target for the progressive reformers. A report to Secretary of War Taft provided a summary of what the American civil administration had achieved. It included, in addition to the rapid building of a public school system based on English language teaching:

:steel and concrete wharves at the newly renovated

Port of Manila; dredging the

River Pasig

The Pasig River ( fil, Ilog Pasig) is a water body in the Philippines that connects Laguna de Bay to Manila Bay. Stretching for , it bisects the Philippine capital of Manila and its surrounding urban area into northern and southern halves. It ...

,; streamlining of the Insular Government; accurate, intelligible accounting; the construction of a telegraph and cable communications network; the establishment of a postal savings bank; large-scale road-and bridge-building; impartial and incorrupt policing; well-financed civil engineering; the conservation of old Spanish architecture; large public parks; a bidding process for the right to build railways; Corporation law; and a coastal and geological survey.

Cuba

While the Philippines remained under U.S. control until 1946, Cuba gained independence in 1902. The

Platt Amendment, passed during the final year of McKinley's tenure, made Cuba a de facto

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

of the United States. Roosevelt won congressional approval for a reciprocity agreement with Cuba in December 1902, thereby lowering tariffs on trade between the two countries. In 1906, an insurrection erupted against Cuban President

Tomás Estrada Palma

Tomás Estrada Palma (c. July 6, 1832 – November 4, 1908) was a Cuban politician, the president of the Cuban Republican in Arms during the Ten Years' War, and the first President of Cuba, between May 20, 1902, and September 28, 1906.

His coll ...

due to his electoral frauds. Both Estrada Palma and his liberal opponents called for an intervention by the U.S., but Roosevelt was reluctant to intervene. When Estrada Palma and his Cabinet resigned, Secretary of War Taft declared that the U.S. would intervene under the terms of the Platt Amendment, beginning the

Second Occupation of Cuba. U.S. forces restored peace to the island, and the occupation ceased shortly before the end of Roosevelt's presidency.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico had been something of an afterthought during the Spanish–American War, but it assumed importance due to its strategic position in the Caribbean Sea. The island provided an ideal naval base for defense of the Panama Canal, and it also served as an economic and political link to the rest of Latin America. Prevailing racist attitudes made Puerto Rican statehood unlikely, so the U.S. carved out a new political status for the island. The Foraker Act and

subsequent Supreme Court cases established Puerto Rico as the first

unincorporated territory

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sove ...

, meaning that the United States Constitution would not fully apply to Puerto Rico. Though the U.S. imposed tariffs on most Puerto Rican imports, it also invested in the island's infrastructure and education system. Nationalist sentiment remained strong on the island and Puerto Ricans continued to primarily speak Spanish rather than English.

Military reforms

Roosevelt placed an emphasis on expanding and reforming the United States military. The

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...