Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

's tenure as the

36th president of the United States began on November 22, 1963, upon the

assassination of President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. Kennedy was in the vehicle with his wife Jacqueline Kennedy Onas ...

, and ended on January 20, 1969. He had been

vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

for days when he succeeded to the presidency. Johnson, a

Democrat from

Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, ran for and won a full four-year term in the

1964 presidential election, in which he defeated

Republican nominee

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

in a landslide. Johnson

withdrew his bid for a second full term in the

1968 presidential election because of his low popularity. Johnson was succeeded by Republican

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, who won the election against Johnson's preferred successor,

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

. His presidency marked the high point of

modern liberalism in the 20th century United States.

Johnson expanded upon the

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

with the

Great Society

The Great Society was a series of domestic programs enacted by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the United States between 1964 and 1968, aimed at eliminating poverty, reducing racial injustice, and expanding social welfare in the country. Johnso ...

, a series of domestic legislative programs to help the poor and downtrodden. After taking office, he won passage of a

major tax cut, the

Clean Air Act, and the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. After the 1964 election, Johnson passed even more sweeping reforms. The

Social Security Amendments of 1965 created two government-run healthcare programs,

Medicare and

Medicaid

Medicaid is a government program in the United States that provides health insurance for adults and children with limited income and resources. The program is partially funded and primarily managed by U.S. state, state governments, which also h ...

. The

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

prohibits racial discrimination in voting, and its passage enfranchised millions of Southern African-Americans. Johnson declared a "

War on Poverty" and established several programs designed to aid the impoverished. He also presided over major increases in federal funding to education and the end of a period of restrictive

immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

laws.

In foreign affairs, Johnson's presidency was dominated by the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

and the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. He pursued conciliatory policies with the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, setting the stage for the

détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

of the 1970s. He was nonetheless committed to a policy of

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

, and he escalated the U.S. presence in Vietnam in order to stop the spread of

Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

in

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

during the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. The number of American military personnel in Vietnam increased dramatically, from 16,000 soldiers in 1963 to over 500,000 in 1968. The Johnson administration did this while they were not entirely confident in a US victory. Behind the decision to escalate the Vietnam War was the pressure of masculinity. He believed that increasing US troops may not guarantee a victory, but that the public would forgive him as he was not "weak" on Communism. Growing anger with the war stimulated a large

antiwar movement based especially on university campuses in the U.S. and abroad. Johnson faced further troubles when summer riots broke out in most major cities after 1965. While he began his presidency with widespread approval, public support for Johnson declined as the war dragged on and domestic unrest across the nation increased. At the same time, the

New Deal coalition

The New Deal coalition was an American political coalition that supported the Democratic Party beginning in 1932. The coalition is named after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, and the follow-up Democratic presidents. It was ...

that had unified the Democratic Party dissolved, and Johnson's support base eroded with it. Though eligible for another term, Johnson announced in March 1968 that he would not seek

renomination. His preferred successor, Vice President

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

, won the

Democratic nomination but was narrowly defeated by Nixon in the 1968 presidential election.

Though he left office with low approval ratings,

polls of historians and political scientists tend to have Johnson ranked as an above-average president. His domestic programs transformed the United States and the role of the federal government, and many of his programs remain in effect today. Johnson's handling of the Vietnam War remains broadly unpopular, but his civil rights initiatives are nearly-universally praised for their role in removing barriers to racial equality.

Accession

Johnson represented

Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

in the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

from 1949 to 1961, and served as the Democratic leader in the Senate beginning in 1953. He sought the

1960 Democratic presidential nomination, but was defeated by

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

. Hoping to shore up support in the South and West, Kennedy asked Johnson to serve as his running mate, and Johnson agreed to join the ticket. In the

1960 presidential election, the Kennedy-Johnson ticket narrowly defeated the

Republican ticket led by Vice President

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. Johnson played a frustrating role as a powerless vice president, rarely consulted except specific issues such as the space program.

Kennedy was

assassinated

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

on November 22, 1963, while riding in a presidential motorcade through

Dallas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

.

Later that day, Johnson took the

presidential oath of office aboard

Air Force One

Air Force One is the official air traffic control-designated Aviation call signs, call sign for a United States Air Force aircraft carrying the president of the United States. The term is commonly used to denote U.S. Air Force aircraft modifie ...

. Johnson was convinced of the need to make an immediate show of transition of power after the assassination to provide stability to a grieving nation. He and the

Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For i ...

, not knowing whether the assassin

acted alone or as part of a

broader conspiracy, felt compelled to return rapidly to

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

Johnson's rush to return to Washington was greeted by some with assertions that he was in too much haste to assume power.

[Dallek (1998), pp. 49–51.]

Taking up Kennedy's legacy, Johnson declared that "no memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the

Civil Rights Bill for which he fought so long." The wave of national grief following the assassination gave enormous momentum to Johnson's legislative agenda. On November 29, 1963, Johnson issued an executive order renaming NASA's Launch Operations Center at

Merritt Island, Florida

Merritt Island is a peninsula, commonly referred to as an island, in Brevard County, Florida, United States, located on the eastern Florida coast, along the Atlantic Ocean. It is also the name of an unincorporated town in the central and south ...

, as the

Kennedy Space Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the NASA, National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten NASA facilities#List of field c ...

, and the nearby launch facility at

Cape Canaveral Air Force Station

Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (CCSFS) is an installation of the United States Space Force's Space Launch Delta 45, located on Cape Canaveral in Brevard County, Florida.

Headquartered at the nearby Patrick Space Force Base, the sta ...

as Cape Kennedy.

In response to the public demand for answers and the growing number of

conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

, Johnson established a commission headed by Chief Justice

Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presid ...

, known as the

Warren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President of the United States, President Lyndon B. Johnson through on November 29, 1963, to investigate the A ...

, to investigate Kennedy's assassination. The commission conducted extensive research and hearings and unanimously concluded that

Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at age 12 for truan ...

acted alone in the assassination. Since the commission's official report was released in September 1964, other federal and municipal investigations have been conducted, most of which support the conclusions reached in the Warren Commission report. Nonetheless, a significant percentage of Americans polled still indicate a belief in some sort of conspiracy.

Administration

When Johnson assumed office following President Kennedy's death, he asked the existing Cabinet to remain in office. Despite his notoriously poor relationship with the new president, Attorney General

Robert F. Kennedy stayed on as Attorney General until September 1964, when he resigned to

run for the U.S. Senate. Four of the Kennedy cabinet members Johnson inherited—Secretary of State

Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States secretary of state from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving secretary of state after Cordell Hull from the ...

, Secretary of the Interior

Stewart Udall

Stewart Lee Udall (January 31, 1920 – March 20, 2010) was an American politician and later, a federal government official who belonged to the Democratic Party. After serving three terms as a congressman from Arizona, he served as Secretary ...

, Secretary of Agriculture

Orville L. Freeman, and Secretary of Labor

W. Willard Wirtz—served until the end of Johnson's presidency. Other Kennedy holdovers, including Secretary of Defense

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ...

, left office during Johnson's tenure. After the creation of the

Department of Housing and Urban Development

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government. It administers federal housing and urban development laws. It is headed by the secretary of housing and u ...

in 1965, Johnson appointed

Robert C. Weaver as the head of that department, making Weaver the

first African-American cabinet secretary in U.S. history.

Johnson concentrated decision-making in his greatly expanded

White House staff. Many of the most prominent Kennedy staff appointees, including

Ted Sorensen

Theodore Chaikin Sorensen (May 8, 1928 – October 31, 2010) was an American lawyer, writer, and presidential adviser. He was a speechwriter for President John F. Kennedy, as well as one of his closest advisers. President Kennedy once called hi ...

and

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. ( ; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a ...

, left soon after Kennedy's death. Other Kennedy staffers, including

National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy

McGeorge "Mac" Bundy (March 30, 1919 – September 16, 1996) was an American academic who served as the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 through 1966. He was president of the Ford Fou ...

and

Larry O'Brien

Lawrence Francis O'Brien Jr. (July 7, 1917September 28, 1990) was an American politician and commissioner of the National Basketball Association (NBA) from 1975 to 1984. He was one of the United States Democratic Party's leading electoral strat ...

, played important roles in the Johnson administration. Johnson did not have an official

White House Chief of Staff

The White House chief of staff is the head of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, a position in the federal government of the United States.

The chief of staff is a Political appointments in the United States, politi ...

. Initially, his long-time administrative assistant

Walter Jenkins presided over the day-to-day operations at the White House.

Bill Moyers

Bill Moyers (born Billy Don Moyers; June 5, 1934) is an American journalist and political commentator. Under the Johnson administration he served from 1965 to 1967 as the eleventh White House Press Secretary. He was a director of the Council ...

, the youngest member of Johnson's staff, was hired at the outset of Johnson's presidency. Moyers quickly rose into the front ranks of the president's aides and acted informally as the president's chief of staff after the departure of Jenkins.

George Reedy, another long-serving aide, assumed the post of

White House Press Secretary

The White House press secretary is a senior White House official whose primary responsibility is to act as spokesperson for the executive branch of the United States federal government, especially with regard to the president, senior aides and ...

,

[Dallek (1998), p. 67.] while

Horace Busby, a valued aide to Johnson at various points in his political career, served primarily as a speech writer and political analyst. Other notable Johnson staffers include

Jack Valenti

Jack Joseph Valenti (September 5, 1921 – April 26, 2007) was an American political advisor and lobbyist who served as a Special Assistant to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. He was also the longtime president of the Motion Picture Association ...

,

George Christian,

Joseph A. Califano Jr.,

Richard N. Goodwin, and

W. Marvin Watson.

Ramsey Clark

William Ramsey Clark (December 18, 1927 – April 9, 2021) was an American lawyer, activist, and United States Federal Government, federal government official. A progressive, New Frontier liberal, he occupied senior positions in the United States ...

who was the last surviving member of the cabinet died in April 2021, Johnson himself having died in January 1973.

Vice presidency

The office of vice president remained vacant during Johnson's first (-day partial) term, as at the time there was no way to fill a vacancy in the vice presidency. Johnson

selected Senator

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

of Minnesota, a leading liberal, as his running mate in the 1964 election, and Humphrey served as vice president throughout Johnson's second term.

Led by Senator

Birch Bayh

Birch Evans Bayh Jr. (; January 22, 1928 – March 14, 2019) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as a member of United States Senate from 1963 to 1981. He was first elected t ...

and Representative

Emanuel Celler, Congress, on July 5, 1965, approved an amendment to the Constitution addressing succession to the presidency and establishing procedures both for filling a vacancy in the office of the vice president, and for responding to presidential disabilities. It was ratified by the requisite number of states on February 10, 1967, becoming the

Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Twenty-fifth Amendment (Amendment XXV) to the United States Constitution addresses issues related to presidential succession and disability.

It clarifies that the Vice President of the United States, vice president becomes President of th ...

.

Judicial appointments

Johnson made two appointments to the

Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

while in office. Anticipating court challenges to his legislative agenda, Johnson thought it would be advantageous to have a close confidant on the Supreme Court who could provide him with inside information, and chose prominent attorney and close friend

Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from Rho ...

to fill that role. He created an opening on the court by convincing Justice Goldberg to become

United States Ambassador to the United Nations

The United States ambassador to the United Nations is the leader of the U.S. delegation, the United States Mission to the United Nations, U.S. Mission to the United Nations. The position is formally known as the Permanent representative to the U ...

. When a second vacancy arose in 1967,

Johnson appointed Solicitor General

Thurgood Marshall

Thoroughgood "Thurgood" Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme C ...

to the Court, and Marshall became the first African American Supreme Court justice in U.S. history. In 1968, Johnson nominated Fortas to succeed retiring Chief Justice

Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presid ...

and nominated

Homer Thornberry to succeed Fortas as an associate justice. Fortas's nomination was blocked by senators opposed to his liberal views and particularly, his close association with the president. Marshall would be a consistent liberal voice on the Court until his retirement in 1991, but Fortas stepped down from the Supreme Court in 1969.

In addition to his Supreme Court appointments, Johnson appointed 40 judges to the

United States Courts of Appeals, and 126 judges to the

United States district courts

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the United States federal judiciary, U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each United States federal judicial district, federal judicial district. Each district cov ...

. Here too he had a number of

judicial appointment controversies, with one appellate and three district court nominees not being confirmed by the U.S. Senate before his presidency ended.

Domestic affairs

Great Society domestic program

Despite his political prowess and previous service as

Senate Majority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and people of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as chief spokespersons for their respective political parties, holding the ...

, Johnson had largely been sidelined in the Kennedy administration. He took office determined to secure the passage of Kennedy's unfinished domestic agenda, which, for the most part, had remained bottled-up in various congressional committees. Many of the liberal initiatives favored by Kennedy and Johnson had been blocked for decades by a

conservative coalition

The conservative coalition, founded in 1937, was an unofficial alliance of members of the United States Congress which brought together the conservative wings of the Republican and Democratic parties to oppose President Franklin Delano Rooseve ...

of Republicans and Southern Democrats; on the night Johnson became president, he asked an aide, "do you realize that every issue that is on my desk tonight was on my desk when I came to Congress in 1937?" By early 1964, Johnson had begun to use the name "

Great Society

The Great Society was a series of domestic programs enacted by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the United States between 1964 and 1968, aimed at eliminating poverty, reducing racial injustice, and expanding social welfare in the country. Johnso ...

" to describe his domestic program; the term was coined by

Richard Goodwin, and drawn from

Eric Goldman's observation that the title of

Walter Lippman

Walter may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Walter (name), including a list of people and fictional and mythical characters with the given name or surname

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–19 ...

's book ''The Good Society'' best captured the totality of president's agenda. Johnson's Great Society program encompassed movements of urban renewal, modern transportation, clean environment, anti-poverty, healthcare reform, crime control, and educational reform. To ensure the passage of his programs, Johnson placed an unprecedented emphasis on relations with Congress.

Taxation and budget

Influenced by the

Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

school of economics by his chief economic advisor

Seymour E. Harris, Kennedy had proposed a tax cut designed to stimulate consumer demand and lower unemployment. Kennedy's bill was passed by the House, but faced opposition from

Harry Byrd, the chairman of the

Senate Finance Committee.

After Johnson took office and agreed to decrease the total federal budget to under $100 billion, Byrd dropped his opposition, clearing the way for the passage of the

Revenue Act of 1964. Signed into law on February 26, 1964, the act cut individual income tax rates across the board by approximately 20 percent, cut the top marginal tax rate from 91 to 70 percent, and slightly reduced corporate tax rates. Passage of the long-stalled tax cut facilitated efforts to move ahead on civil rights legislation.

Despite a period of strong economic growth,

heavy spending on the Vietnam War and on domestic programs contributed to a rising budget deficit, as well as a period of

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

that would continue into the 1970s. Between fiscal years 1966 and 1967, the budget deficit more than doubled to $8.6 billion, and it continued to grow in fiscal year 1968. To counter this growing budget deficit, Johnson reluctantly signed a second tax bill, the

Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968, which included a mix of tax increases and spending cuts, producing a budget surplus for fiscal year 1969.

Civil rights

Johnson's success in passing major civil rights legislation was a stunning surprise.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Though a product of the South and a protege of segregationist Senator

Richard Russell Jr., Johnson had long been personally sympathetic to the

Civil Rights Movement. By the time he took office as president, he had come to favor passage of the first major civil rights bill since the

Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

. Kennedy had submitted a major civil rights bill that would ban

segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

in public institutions, but it remained stalled in Congress when Johnson assumed the presidency. Johnson sought not only to win passage of the bill, but also to prevent Congress from stripping the most important provisions of the bill and passing another watered-down civil rights bill, as it had done in the 1950s. He opened his January 8, 1964,

State of the Union address with a public challenge to Congress, stating, "let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined."

Biographer

Randall B. Woods writes that Johnson effectively used appeals to

Judeo-Christian ethics to garner support for the civil rights law, stating that "LBJ wrapped white America in a moral straight jacket. How could individuals who fervently, continuously, and overwhelmingly identified themselves with a merciful and just God continue to condone racial discrimination, police brutality, and segregation?"

In order for Johnson's civil rights bill to reach the House floor for a vote, the president needed to find a way to circumvent Representative

Howard W. Smith, the chairman of the

House Rules Committee. Johnson and his allies convinced uncommitted Republicans and Democrats to support a

discharge petition

In United States parliamentary procedure, a discharge petition is a means of bringing a bill out of committee and to the floor for consideration without a report from the committee by "discharging" the committee from further consideration of a bi ...

, which would force the bill onto the House floor.

Facing the possibility of being bypassed by a discharge petition, the House Rules Committee approved the civil rights bill and moved it to the floor of the full House. Possibly in an attempt to derail the bill, Smith added an amendment to the bill that would ban gender discrimination in employment. Despite the inclusion of the gender discrimination provision, the House passed the civil rights bill by a vote of 290–110 on February 10, 1964. 152 Democrats and 136 Republicans voted in favor of the bill, while the majority of the opposition came from 88 Democrats representing states that had seceded during the Civil War.

[Zelizer (2015), pp. 100–101.]

Johnson convinced Senate Majority Leader

Mike Mansfield

Michael Joseph Mansfield (March 16, 1903 – October 5, 2001) was an American Democratic Party politician and diplomat who represented Montana in the United States House of Representatives from 1943 to 1953 and United States Senate from 1953 t ...

to put the House bill directly into consideration by the full Senate, bypassing the

Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

and its segregationist chairman

James Eastland. Since bottling up the civil rights bill in a committee was no longer an option, the anti-civil rights senators were left with the

filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

as their only remaining tool. Overcoming the filibuster required the support of at least 20 Republicans, who were growing less supportive of the bill due to the fact that the party's leading presidential contender, Senator

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

, opposed the bill. Johnson and the conservative Dirksen reached a compromise in which Dirksen agreed to support the bill, but the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is a federal agency that was established via the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to administer and enforce civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination ...

's enforcement powers were weakened. After months of debate, the Senate voted for closure in a 71–29 vote, narrowly clearing the 67-vote threshold then required to break filibusters.

[Zelizer (2015), pp. 126–127.] Though most of the opposition came from Southern Democrats, Senator Goldwater and five other Republicans also voted against ending the filibuster.

[ On June 19, the Senate voted to 73–27 in favor of the bill, sending it to the president.

Johnson signed the ]Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

into law on July 2. "We believe that all men are created equal," Johnson said in an address to the country. "Yet many are denied equal treatment."discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

based on race, color

Color (or colour in English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though co ...

, national origin, religion, or sex.public accommodations

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichk ...

and employment discrimination

Employment discrimination is a form of illegal discrimination in the workplace based on legally protected characteristics. In the U.S., federal anti-discrimination law prohibits discrimination by employers against employees based on age, race, ...

, and strengthened the federal government's power to investigate racial and gender employment discrimination. Legend has it that, while signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Johnson told an aide, "We have lost the South for a generation," as he anticipated coming backlash from Southern whites against the Democratic Party. The Civil Rights Act was later upheld by the Supreme Court in cases such as '' Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States''.

Voting Rights Act

After the end of Reconstruction, most Southern states enacted laws designed to disenfranchise and marginalize black citizens from politics so far as practicable without violating the Fifteenth Amendment. Even with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the January 1964 ratification of the 24th Amendment, which banned poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

es, many states continued to effectively disenfranchise African-Americans through mechanisms such as " white primaries" and literacy test

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write. Literacy tests have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants.

Between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were used as an effecti ...

s.[May (2013), 47–52] He did not, however, publicly push for the legislation at that time; his advisers warned him of political costs for vigorously pursuing a voting rights bill so soon after Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act, and Johnson was concerned that championing voting rights would endanger his other Great Society reforms by angering Southern Democrats in Congress.[

Soon after the 1964 election, civil rights organizations such as the ]Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., ...

(SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

(SNCC) began a push for federal action to protect the voting rights of racial minorities.[ On March 7, 1965, these organizations began the ]Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized by Nonviolence, nonvi ...

in which Selma residents proceeded to march to Alabama's capital, Montgomery, to highlight voting rights issues and present Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

with their grievances. On the first march, demonstrators were stopped by state and county police, who shot tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymatory agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the Mace (spray), early commercial self-defense spray, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the ey ...

into the crowd and trampled protesters. Televised footage of the scene, which became known as "Bloody Sunday", generated outrage across the country.Joint session of Congress

A joint session of the United States Congress is a gathering of members of the two chambers of the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Joint sessions can be held on ...

. He began:

Johnson and Dirksen established a strong bipartisan alliance in favor of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

, precluding the possibility of a Senate filibuster defeating the bill. In August 1965, the House approved the bill by a vote of 333 to 85, and Senate passed the bill by a vote of 79 to 18. The landmark legislation, which Johnson signed into law on August 6, 1965, outlawed discrimination in voting, thus allowing millions of Southern blacks to vote for the first time. In accordance with the act, Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Virginia were subjected to the procedure of preclearance in 1965. The results were significant; between the years of 1968 and 1980, the number of Southern black elected state and federal officeholders nearly doubled.

Civil Rights Act of 1968

In April 1966, Johnson submitted a bill to Congress that barred house owners from refusing to enter into agreements on the basis of race; the bill immediately garnered opposition from many of the Northerners who had supported the last two major civil rights bills. Though a version of the bill passed the House, it failed to win Senate approval, marking Johnson's first major legislative defeat. The law gained new impetus after the April 4, 1968, assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an American civil rights activist, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:05& ...

, and the civil unrest

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, civil strife, or turmoil, are situations when law enforcement and security forces struggle to maintain public order or tranquility.

Causes

Any number of things may cause civil di ...

across the country following King's death.Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

John William McCormack

John William McCormack (December 21, 1891 – November 22, 1980) was an American politician from Boston, Massachusetts. McCormack served in the United States Army during World War I, and afterwards in the Massachusetts State Senate before winnin ...

, the bill passed Congress on April 10 and was quickly signed into law by Johnson.[ The ]Fair Housing Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a Lists of landmark court decisions, landmark law in the United States signed into law by President of the United States, United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles ...

, a component of the bill, outlawed several forms of housing discrimination

Housing discrimination refers to patterns of discrimination that affect a person's ability to rent or buy housing. This disparate treatment of a person on the housing market can be based on group characteristics or on the place where a person liv ...

and effectively allowed many African Americans to move to the suburbs.

"War on Poverty"

The 1962 publication of '' The Other America'' had helped to raise the profile of

The 1962 publication of '' The Other America'' had helped to raise the profile of poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

as a public issue, and the Kennedy administration had begun formulating an anti-poverty initiative. Johnson built on this initiative, and in his 1964 State of the Union Address stated, "this administration today, here and now, declares an unconditional war on poverty in America. Our aim is not only to relieve the symptoms of poverty but to cure it–and above all, to prevent it."

In April 1964, Johnson proposed the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964

The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 () authorized the formation of local Community Action Agencies as part of the War on Poverty. These agencies are directly regulated by the federal government. "It is the purpose of The Economic Opportunity A ...

, which would create the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) to oversee local Community Action Agencies

In the United States and its territories, Community Action Agencies (CAA) are local private and public non-profit organizations that carry out the Community Action Program (CAP), which was founded by the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act to fight p ...

(CAA) charged with dispensing aid to those in poverty. "Through a new Community Action program, we intend to strike at poverty at its source – in the streets of our cities and on the farms of our countryside among the very young and the impoverished old. This program asks men and women throughout the country to prepare long-range plans for the attack on poverty in their own local communities," Johnson told Congress on March 16, 1964. Each CAA was required to have "maximum feasible participation" from local residents, who would design and operate antipoverty programs unique to their communities' needs. This was threatening to local political regimes who saw CAAs as alternative power structure

In political science, power is the ability to influence or direct the actions, beliefs, or conduct of actors. Power does not exclusively refer to the threat or use of force ( coercion) by one actor against another, but may also be exerted thr ...

s in their own communities, funded and encouraged by the OEO.[ p. 103.] Many political leaders (i.e., Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley) publicly or privately expressed displeasure with the power-sharing that CAAs brought to poor and minority neighborhoods.[LBJ and Senator Richard Russell on the Community Action Program]

," audio recording Jun 02, 1966: conversation excerpt (President Johnson and Georgia Sen. Richard Russell express dislike and distrust of Community Action Program), Conversation Number: WH6606.01 #10205, The Miller Center In 1967, the Green Amendment gave city governments the right to decide which entity would be the official CAA for their community. The net result was a halt to the citizen participation reform movement.

The Economic Opportunity Act would also create the Job Corps and AmeriCorps VISTA, a domestic version of the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an Independent agency of the U.S. government, independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to communities in partner countries around the world. It was established in Marc ...

. Modeled after the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was ...

(CCC), Job Corps was a residential education and job-training program that provided academic and vocational skills

Skill is a measure of the amount of worker's expertise, specialization, wages, and supervisory capacity. Skilled workers are generally more trained, higher paid, and have more responsibilities than unskilled workers.

Skilled workers have long had ...

to low-income at-risk young people (ages 16 to 24), helping them gain meaningful employment.illiteracy

Literacy is the ability to read and write, while illiteracy refers to an inability to read and write. Some researchers suggest that the study of "literacy" as a concept can be divided into two periods: the period before 1950, when literacy was ...

, inadequate housing, and poor health. They worked on community projects with various organizations, communities, and individuals.Sargent Shriver

Robert Sargent Shriver Jr. (November 9, 1915 – January 18, 2011) was an American diplomat, politician, and activist. He was a member of the Shriver family by birth, and a member of the Kennedy family through his marriage to Eunice Kennedy. ...

, the OEO developed programs like Neighborhood Legal Services, a program that provided free legal assistance to the poor in such matters as contracts and disputes with landlords. In August 1965, Johnson signed the

In August 1965, Johnson signed the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965

The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965 (, ) is a major revision to federal housing policy in the United States which instituted several major expansions in federal housing programs.

The United States Congress passed and President Lyndon B. ...

into law. The legislation, which he called "the single most important breakthrough" in federal housing policy since the 1920s, greatly expanded funding for existing federal housing programs, and added new programs to provide rent subsidies for the elderly and disabled; housing rehabilitation grants to poor homeowners; provisions for veterans to make very low down-payments to obtain mortgages; new authority for families qualifying for public housing to be placed in empty private housing (along with subsidies to landlords); and matching grants to localities for the construction of water and sewer facilities, construction of community centers in low-income areas, and urban beautification. Four weeks later, on September 9, the president signed legislation establishing the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Johnson took an additional step in the War on Poverty with an urban renewal

Urban renewal (sometimes called urban regeneration in the United Kingdom and urban redevelopment in the United States) is a program of land redevelopment often used to address real or perceived urban decay. Urban renewal involves the clearing ...

effort, presenting to Congress in January 1966 the "Demonstration Cities Program." To be eligible a city would need to demonstrate its readiness to "arrest blight and decay and make substantial impact on the development of its entire city." Johnson requested an investment of $400 million per year totaling $2.4 billion. In late 1966, Congress passed a substantially reduced program costing $900 million, which Johnson later called the Model Cities Program. The program's initial goals emphasized comprehensive planning, involving not just rebuilding but also rehabilitation, social service delivery, and citizen participation. Biographer Jeff Shesol wrote that Model Cities did not last long enough to be considered a breakthrough. Poor individuals who secured government jobs utilized their paychecks to escape deteriorating neighborhoods. In some cities the chief beneficiaries were urban political machines. The program ended in 1974.

In August 1968, Johnson passed an even larger funding package, designed for expanding aid to cities, the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968. The program extended upon the 1965 legislation, but created two new housing finance programs designed for moderate-income families, Section 235 and 236, and vastly expanded support for public housing and urban renewal.

As a result of Johnson's war on poverty, as well as a strong economy, the nationwide poverty rate fell from 20 percent in 1964 to 12 percent in 1974.

Education

Johnson, whose own ticket out of poverty was a public education in Texas, fervently believed that education was a cure for ignorance and poverty. Education funding in the 1960s was especially tight due to the demographic challenges posed by the large

Johnson, whose own ticket out of poverty was a public education in Texas, fervently believed that education was a cure for ignorance and poverty. Education funding in the 1960s was especially tight due to the demographic challenges posed by the large Baby Boomer

Baby boomers, often shortened to boomers, are the demographic cohort preceded by the Silent Generation and followed by Generation X. The generation is often defined as people born from 1946 to 1964 during the mid-20th century baby boom that ...

generation, but Congress had repeatedly rejected increased federal financing for public schools. Buoyed by his landslide victory in the 1964 election, in early 1965 Johnson proposed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on April 11, 1965. Part of Johnson's "War on Poverty", the act has been one of the most far-rea ...

(ESEA), which would double federal spending on education from $4 billion to $8 billion. The bill quickly passed both houses of Congress by wide margins. ESEA increased funding to all school districts, but directed more money going to districts that had large proportions of students from poor families. The bill offered funding to parochial school

A parochial school is a private school, private Primary school, primary or secondary school affiliated with a religious organization, and whose curriculum includes general religious education in addition to secular subjects, such as science, mathem ...

s indirectly, but prevented school districts that practiced segregation from receiving federal funding. The federal share of education spending rose from 3 percent in 1958 to 10 percent in 1965, and continued to grow after 1965. The act also contributed to a major increase in the pace of desegregation, as the share of Southern African-American students attending integrated schools rose from two percent in 1964 to 32 percent in 1968.

Johnson's second major education program was the Higher Education Act of 1965

The Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) () was legislation signed into Law of the United States, United States law on November 8, 1965, as part of President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society domestic agenda. Johnson chose Texas State University (t ...

, intended "to strengthen the educational resources of our colleges and universities and to provide financial assistance for students in postsecondary and higher education." The legislation increased federal money given to universities, created scholarships, gave low-interest loans to students, and established a Teacher Corps. College graduation rates boomed after the passage of the act, with the percentage of college graduates tripling from 1964 to 2013.cognitive development

Cognitive development is a field of study in neuroscience and psychology focusing on a child's development in terms of information processing, conceptual resources, perceptual skill, language learning, and other aspects of the developed adult bra ...

during their early years. As a solution, Head Start provided medical, dental, social service, nutritional, and psychological care for disadvantaged preschool children.Upward Bound

Upward Bound is a federally funded educational program within the United States. The program is one of a cluster of programs now referred to as Federal TRIO Programs, TRiO, all of which owe their existence to the federal Economic Opportunity Act ...

, a program designed to provide college preparation for poor teenagers.

In order to cater to the growing number of Spanish-speaking children from Mexico, California and Texas set up public schools that were segregated. These schools primarily focused on teaching English, but they received less funding than schools for non-Latino white children. This resulted in a shortage of resources and underqualified teachers in these schools. The Bilingual Education Act

The Bilingual Education Act (BEA), also known as the Title VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Amendments of 1967, was the first United States federal legislation that recognized the needs of limited English speaking ability (LESA) s ...

of 1968 provided federal grants to school districts for the purpose of establishing educational programs for children with limited English-speaking ability until it expired in 2002.

Medicare and Medicaid

Since 1957, many Democrats had advocated for the government to cover the cost of hospital visits for seniors, but the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is an American professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. This medical association was founded in 1847 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was 271,660 ...

(AMA) and fiscal conservatives opposed a government role in health insurance

Health insurance or medical insurance (also known as medical aid in South Africa) is a type of insurance that covers the whole or a part of the risk of a person incurring medical expenses. As with other types of insurance, risk is shared among ma ...

. By 1965, half of Americans over the age of 65 did not have health insurance. Johnson supported the passage of the King-Anderson Bill, which would establish a Medicare program for elderly patients administered by the Social Security Administration

The United States Social Security Administration (SSA) is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government that administers Social Security (United ...

and financed by payroll taxes. Wilbur Mills

Wilbur Daigh Mills (May 24, 1909 – May 2, 1992) was an American Democratic politician and lawyer who represented in the United States House of Representatives from 1939 until his retirement in 1977. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Co ...

, chairman of the key House Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

, had long opposed such reforms, but the election of 1964 had defeated many allies of the AMA and shown that the public supported some version of public medical care.

Mills and Johnson administration official Wilbur J. Cohen crafted a three-part healthcare bill consisting of Medicare Part A, Medicare Part B, and Medicaid

Medicaid is a government program in the United States that provides health insurance for adults and children with limited income and resources. The program is partially funded and primarily managed by U.S. state, state governments, which also h ...

. Medicare Part A covered up to ninety days of hospitalization (minus a deductible) for all Social Security recipients, Medicare Part B provided voluntary medical insurance to seniors for physician visits, and Medicaid established a program of state-provided health insurance for indigents. The bill quickly won the approval of both houses of Congress, and Johnson signed the Social Security Amendments of 1965 into law on July 30, 1965. Johnson gave the first two Medicare cards to former President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

and his wife Bess after signing the Medicare bill at the Truman Library

The Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum is the presidential library and resting place of Harry S Truman, the 33rd president of the United States (1945–1953), his wife Bess and daughter Margaret, and is located on U.S. Highw ...

. Although some doctors attempted to prevent the implementation of Medicare by boycotting it, it eventually became a widely accepted program. In 1966, Medicare enrolled approximately 19 million elderly people.

Environment

The 1962 publication of ''

The 1962 publication of ''Silent Spring

''Silent Spring'' is an environmental science book by Rachel Carson. Published on September 27, 1962, the book documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of DDT, a pesticide used by soldiers during World War II. Carson acc ...

'' by Rachel Carson

Rachel Louise Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964) was an American marine biologist, writer, and conservation movement, conservationist whose sea trilogy (1941–1955) and book ''Silent Spring'' (1962) are credited with advancing mari ...

brought new attention to environmentalism and the danger that pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause harm. Pollution can take the form of any substance (solid, liquid, or gas) or energy (such as radioactivity, heat, sound, or light). Pollutants, the component ...

and pesticide poisoning

A pesticide poisoning occurs when pesticides, chemicals intended to control a pest, affect non-target organisms such as humans, wildlife, plants, or bees. There are three types of pesticide poisoning. The first of the three is a single and sho ...

(i.e., DDT) posed to public health. Johnson retained Kennedy's staunchly pro-environment Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall

Stewart Lee Udall (January 31, 1920 – March 20, 2010) was an American politician and later, a federal government official who belonged to the Democratic Party. After serving three terms as a congressman from Arizona, he served as Secretary ...

, and signed into law numerous bills designed to protect the environment. He signed into law the Clean Air Act of 1963

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is the United States' primary federal air quality law, intended to reduce and control Air pollution in the United States, air pollution nationwide. Initially enacted in 1963 and amended many times since, it is one of th ...

, which had been proposed by Kennedy. The Clean Air Act set emission standards

Emission standards are the legal requirements governing air pollutants released into the atmosphere. Emission standards set quantitative limits on the permissible amount of specific air pollutants that may be released from specific sources ov ...

for stationary emitters of air pollutants and directed federal funding to air quality research. In 1965, the act was amended by the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act, which directed the federal government to establish and enforce national standards for controlling the emission of pollutants from new motor vehicles and engines. In 1967, Johnson and Senator Edmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1980 to 1981, a United States Senator from Maine from 1 ...

led passage of the Air Quality Act of 1967, which increased federal subsidies for state and local pollution control programs.

During his time as President, Johnson signed over 300 conservation measures into law, forming the legal basis of the modern environmental movement. In September 1964, he signed a law establishing the Land and Water Conservation Fund

The United States' Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) is a federal program that was established by Act of Congress in 1965 to provide funds and matching grants to federal, state and local governments for the acquisition of land and water, an ...

, which aids the purchase of land used for federal and state parks. That same month, Johnson signed the Wilderness Act

The Wilderness Act of 1964 () is a federal land management statute meant to protect U.S. Wilderness Area, federal wilderness and to create a formal mechanism for designating wilderness. It was written by Howard Zahniser of The Wilderness Socie ...

, which established the National Wilderness Preservation System

The National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) of the United States protects federal government of the United States, federally managed Wilderness, wilderness areas designated for preservation in their natural condition. Activity on formally ...

; saving 9.1 million acres of forestland from industrial development. The Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, the first piece of comprehensive endangered species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching, inv ...

legislation, authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to list native species of fish and wildlife as endangered and to acquire endangered species habitat for inclusion in the National Wildlife Refuge System

The National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) is a system of protected areas of the United States managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the United States Department of the Interior, Department of the Interi ...

. The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 established the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. The system includes more than 220 rivers

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of its course if it ru ...

, and covers more than 13,400 miles of rivers and streams. The National Trails System Act of 1968 created a nationwide system of scenic and recreational trails

A trail, also known as a path or track, is an unpaved lane or a small paved road (though it can also be a route along a navigable waterways) generally not intended for usage by motorized vehicles, usually passing through a natural area. Ho ...

.Lady Bird Johnson

Claudia Alta "Lady Bird" Johnson (; December 22, 1912 – July 11, 2007) was First Lady of the United States from 1963 to 1969 as the wife of President Lyndon B. Johnson. She had previously been Second Lady of the United States from 1961 to 196 ...

took the lead in calling for passage of the Highway Beautification Act. The act called for control of outdoor advertising

Outdoor advertising or out-of-home (OOH) advertising includes public billboards, wallscapes, and posters seen while "on the go". OOH advertising formats fall into four main categories: billboards, street furniture, Transit media, transit, and a ...

, including removal of certain types of signs, along the nation's growing Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, or the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Hi ...

and the existing federal-aid primary highway system. It also required certain junkyards along Interstate or primary highways to be removed or screened and encouraged scenic enhancement and roadside development. That same year, Muskie led passage of the Water Quality Act of 1965, though conservatives stripped a provision of the act that would have given the federal government the authority to set clean water standards.

Immigration

Johnson himself did not rank immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

as a high priority, but congressional Democrats, led by Emanuel Celler, passed the sweeping Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, was a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The ...

. The act repealed the National Origins Formula, which had restricted emigration from countries outside of Western Europe and the Western Hemisphere. The law did not greatly increase the number of immigrants who would be allowed into the country each year (approximately 300,000), but it did provide for a family reunification

Family reunification is a recognized reason for immigration in many countries because of the presence of one or more family members in a certain country, therefore, enables the rest of the divided family or only specific members of the family to ...

provision that allowed for some immigrants to enter the country regardless of the overall number of immigrants. Largely because of the family reunification provision, the overall level of immigration increased far above what had been expected. Those who wrote the law expected that it would lead to more immigration from Southern Europe and Eastern Europe, as well as relatively minor upticks in immigration from Asia and Africa. Contrary to these expectations, the main source of immigrants shifted away from Europe; by 1976, more than half of legal immigrants came from Mexico, the Philippines, Korea, Cuba, Taiwan, India, or the Dominican Republic. The percentage of foreign-born in the United States increased from 5 percent in 1965 to 14 percent in 2016. Johnson also signed the Cuban Adjustment Act, which granted Cuban refugees an easier path to permanent residency and citizenship.

Transportation

During the mid-1960s, various consumer protection

Consumer protection is the practice of safeguarding buyers of goods and services, and the public, against unfair practices in the marketplace. Consumer protection measures are often established by law. Such laws are intended to prevent business ...

activists and safety experts began making the case to Congress and the American people that more needed to be done to make roads less dangerous and vehicles more safe.Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American lawyer and political activist involved in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes. He is a Perennial candidate, perennial presidential candidate. His 1965 book '' ...

. Early in the following year, Congress held a series of highly publicized hearings regarding highway safety, and ultimately approved two bills—the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act

The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act was enacted in the United States in 1966 to empower the federal government to set and administer new safety standards for motor vehicles and road traffic safety. The Act was the first mandatory fed ...

(NTMVSA) and the Highway Safety Act (HSA)—which the president signed into law on September 9, thus making the federal government responsible for setting and enforcing auto and road safety standards.[ The HSA required each state to implement a safety program supporting driver education and improved licensing and auto inspection; it also strengthened the existing National Driver Register operated by the ]Bureau of Public Roads

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is a division of the United States Department of Transportation that specializes in highway transportation. The agency's major activities are grouped into two programs, the Federal-aid Highway Program a ...

.[ These new rules contributed to a decades-long decline in U.S. motor vehicle fatalities, which fell from 50,894 in 1966 to 32,479 in 2011.]Federal Aviation Agency

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is a Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of Transportation, U.S. Department of Transportation that regulates civil aviation in t ...

, the Coast Guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a Maritime Security Regimes, maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with cust ...

, the Maritime Administration, the Civil Aeronautics Board, and the Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later Trucking industry in the United States, truc ...

. The bill passed both houses of Congress after some negotiation over navigation projects and maritime interests, and Johnson signed the Department of Transportation Act into law on October 15, 1966. Altogether, 31 previously scattered agencies were brought under the Department of Transportation, in what was the biggest reorganization of the federal government since the National Security Act of 1947

The National Security Act of 1947 (Act of Congress, Pub.L.]80-253 61 United States Statutes at Large, Stat.]495 enacted July 26, 1947) was a law enacting major restructuring of the Federal government of the United States, United States governmen ...

.[

]

Domestic unrest

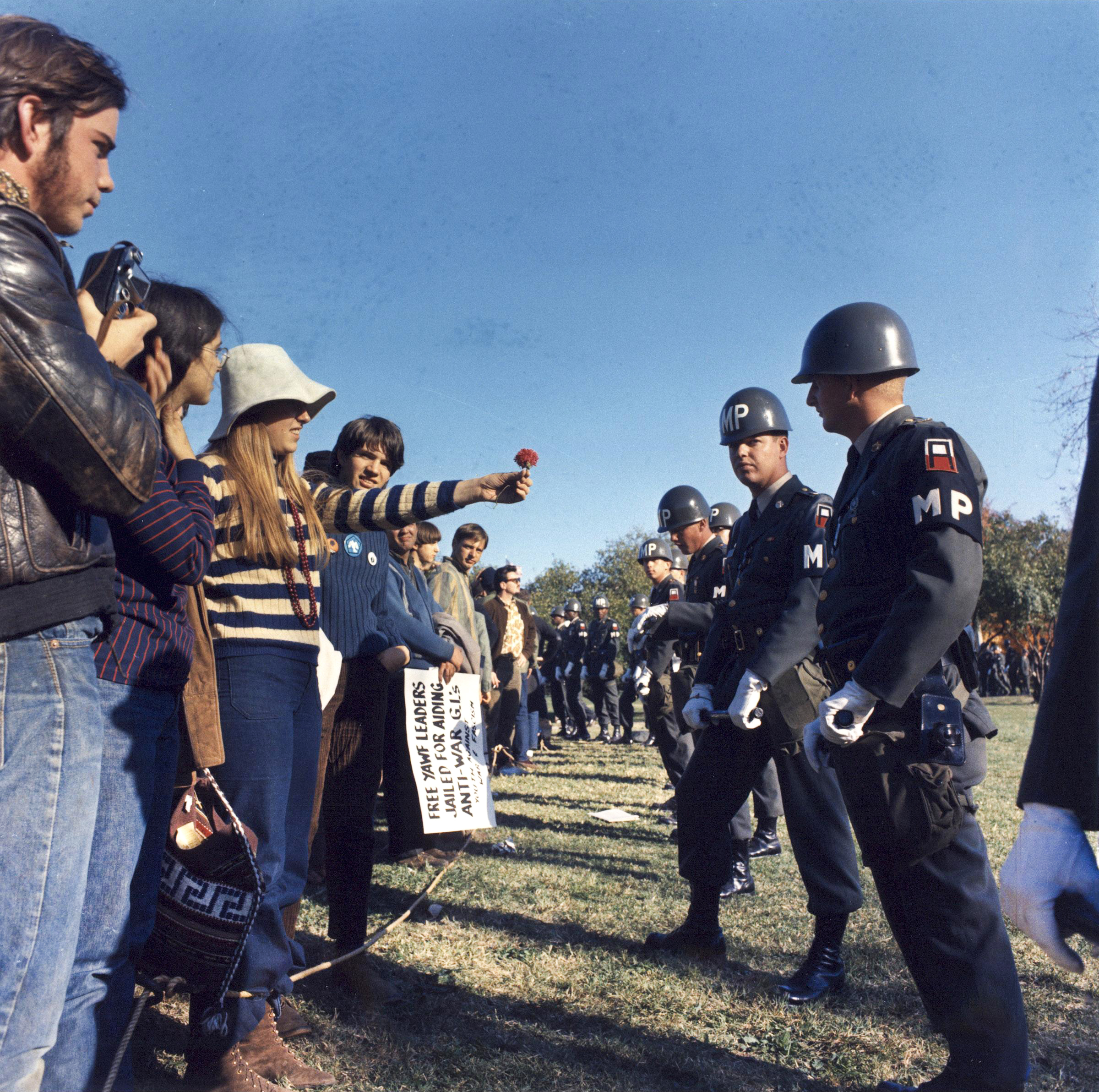

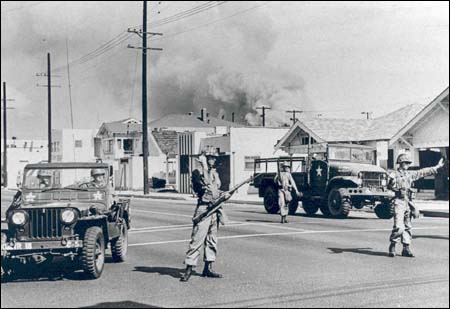

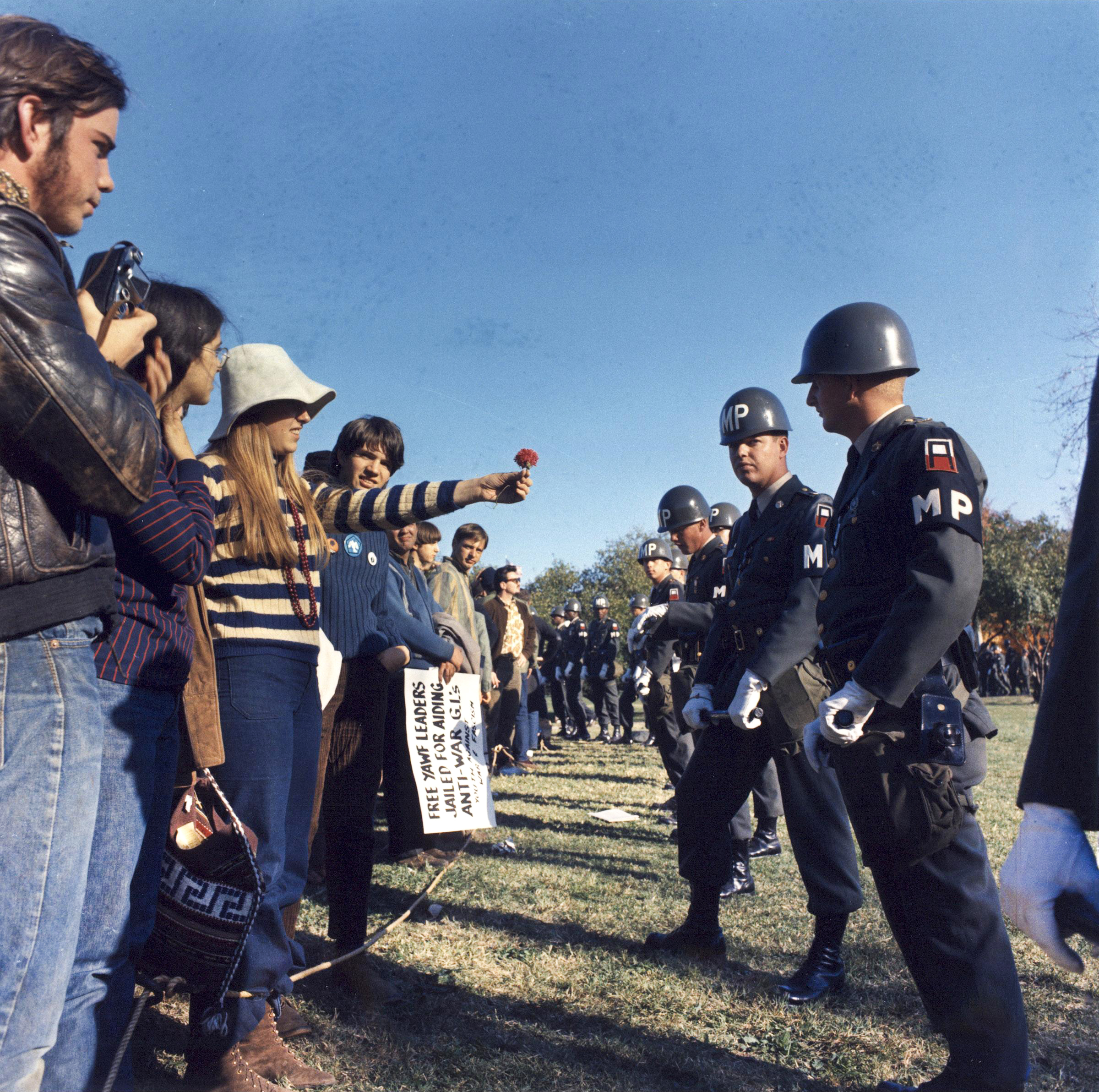

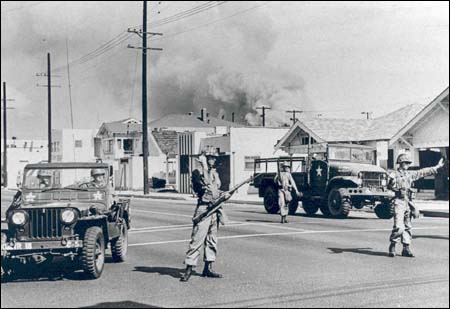

Anti-Vietnam War movement

The American public was generally supportive of the Johnson administration's rapid escalation of U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam in late 1964.

The American public was generally supportive of the Johnson administration's rapid escalation of U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam in late 1964.[Dallek (1998), p. 157.] Johnson closely watched the public opinion polls,[Patterson (1996), p. 683.] which after 1964 generally showed that the public was consistently 40–50 percent War hawk, hawkish (in favor of stronger military measures) and 10–25 percent dovish (in favor of negotiation and disengagement). Johnson quickly found himself pressed between hawks and doves; as his aides told him, "both hawks and doves re frustrated with the war... and take it out on you."[ Lawrence R. Jacobs and Robert Y. Shapiro. "Lyndon Johnson, Vietnam, and Public Opinion: Rethinking Realist Theory of Leadership." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 29#3 (1999), p. 592.] Many anti-war activists identified as members of the "New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

," a broad political movement that distrusted both contemporary mainstream liberalism and Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

. Although other groups and individuals attacked the Vietnam War for various reasons, student activists emerged as the most vocal component of the anti-war movement. Membership of Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships a ...

, a major New Left student group opposed to Johnson's foreign policy, tripled during 1965.

Despite campus protests, the war remained generally popular throughout 1965 and 1966. Following the January 1967 publication of a photo-essay

A photographic essay or photo-essay for short is a form of visual storytelling, a way to present a narrative through a series of images. A photo essay delivers a story using a series of photographs and brings the viewer along a narrative journey.

...

by William F. Pepper depicting some of the injuries inflicted on Vietnamese children by the U.S. bombing campaign, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke out against the war publicly for the first time. King and New Left activist Benjamin Spock