Prehistoric religion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Prehistoric religion is the

Prehistoric religion is the

The question of when religion emerged in the evolving human psyche has sparked the curiosity of paleontologists for decades. On the whole, neither the archaeological record nor the current understanding of how human intelligence evolved suggests early

The question of when religion emerged in the evolving human psyche has sparked the curiosity of paleontologists for decades. On the whole, neither the archaeological record nor the current understanding of how human intelligence evolved suggests early  The lineage leading to

The lineage leading to  The study of Neanderthal ritual, as proxy and preface for religion, revolves around death and burial rites. The first undisputed burials, approximately 150,000 years ago, were performed by Neanderthals. The limits of the archaeological record stymie extrapolation from burial to funeral rites, though evidence of

The study of Neanderthal ritual, as proxy and preface for religion, revolves around death and burial rites. The first undisputed burials, approximately 150,000 years ago, were performed by Neanderthals. The limits of the archaeological record stymie extrapolation from burial to funeral rites, though evidence of

The

The

''Australopithecus'', the first hominins, were a pre-religious people. Though twentieth-century historian of religion

''Australopithecus'', the first hominins, were a pre-religious people. Though twentieth-century historian of religion  In the Upper Paleolithic, religion is associated with symbolism and sculpture. One Upper Paleolithic remnant that draws cultural attention are the

In the Upper Paleolithic, religion is associated with symbolism and sculpture. One Upper Paleolithic remnant that draws cultural attention are the

The Middle Paleolithic was the era of coterminous Neanderthal and ''H. s. sapiens'' (

The Middle Paleolithic was the era of coterminous Neanderthal and ''H. s. sapiens'' (

Neanderthals were the earliest hominins to bury their dead, although not the chronologically first burials, as earlier burials (such as those of the

Neanderthals were the earliest hominins to bury their dead, although not the chronologically first burials, as earlier burials (such as those of the

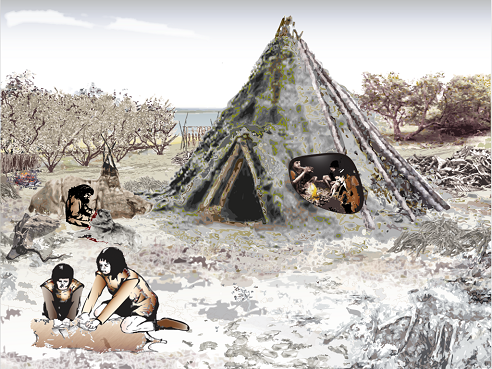

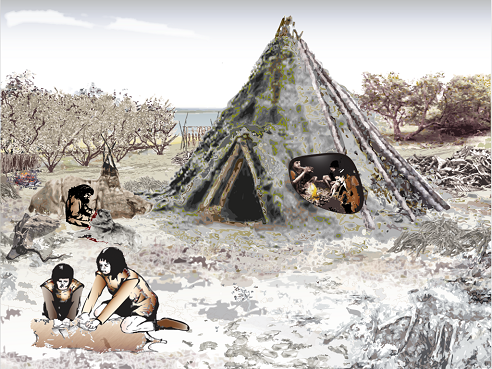

''H. s. sapiens'' emerged in Africa as early as 300,000 years ago. In the Middle Paleolithic, particularly its first couple hundred thousand years, the archaeological record of ''H. s. sapiens'' is barely distinguishable from their Neanderthal and ''H. heidelbergensis'' contemporaries. Though these first ''H. s. sapiens'' demonstrated some ability to construct shelter, use pigments, and collect artifacts, they yet lacked the behavioural sophistication associated with humans today. The process through which ''H. s. sapiens'' became cognitively and culturally sophisticated is known as

''H. s. sapiens'' emerged in Africa as early as 300,000 years ago. In the Middle Paleolithic, particularly its first couple hundred thousand years, the archaeological record of ''H. s. sapiens'' is barely distinguishable from their Neanderthal and ''H. heidelbergensis'' contemporaries. Though these first ''H. s. sapiens'' demonstrated some ability to construct shelter, use pigments, and collect artifacts, they yet lacked the behavioural sophistication associated with humans today. The process through which ''H. s. sapiens'' became cognitively and culturally sophisticated is known as

Another art form of probable religious significance are the

Another art form of probable religious significance are the

The Upper Paleolithic saw the advent of complex burials with lavish

The Upper Paleolithic saw the advent of complex burials with lavish

Upper Paleolithic religions were presumably

Upper Paleolithic religions were presumably  A popular myth about prehistoric religion is

A popular myth about prehistoric religion is

The Mesolithic was the transitional period between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. In European archaeology, it traditionally refers to hunter-gatherers living after the end of the

The Mesolithic was the transitional period between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. In European archaeology, it traditionally refers to hunter-gatherers living after the end of the

The Neolithic was the dawn of agriculture. Originating around 10,000 BC in the

The Neolithic was the dawn of agriculture. Originating around 10,000 BC in the

Particularly in its heartland of the

Particularly in its heartland of the  One of the most famous forms of Neolithic art and architecture were the megalithic

One of the most famous forms of Neolithic art and architecture were the megalithic  Neolithic statues are another area of interest. The

Neolithic statues are another area of interest. The

Burial appears more widespread in the Neolithic than the Upper Paleolithic. In a wide area from the Levant through central Europe, Neolithic burials are frequently found in the houses their denizens lived in; in particular, women and children dominate amongst those buried inside the home. For children in particular, this may have represented the continued inclusion of these children in the family unit and a

Burial appears more widespread in the Neolithic than the Upper Paleolithic. In a wide area from the Levant through central Europe, Neolithic burials are frequently found in the houses their denizens lived in; in particular, women and children dominate amongst those buried inside the home. For children in particular, this may have represented the continued inclusion of these children in the family unit and a

Much of what is understood about Neolithic life comes from individual settlements with particularly preserved archaeological records, such as

Much of what is understood about Neolithic life comes from individual settlements with particularly preserved archaeological records, such as

People in the Neolithic possibly engaged in

People in the Neolithic possibly engaged in  One idea associated with Neolithic religion in popular culture is that of goddess worship. At Çatalhöyük, traditionally considered a centre of goddess worship on account of figurines found in the area, followers of

One idea associated with Neolithic religion in popular culture is that of goddess worship. At Çatalhöyük, traditionally considered a centre of goddess worship on account of figurines found in the area, followers of

The

The

In the

In the  The protohistoric cultures of

The protohistoric cultures of  In Europe, Bronze Age religion is well-studied and has well-understood recurring characteristics. Traits of European Bronze Age religion include a dichotomy between the sun and the underworld, a belief in animals as significant mediators between the physical and spiritual realms, and a focus on "travel, transformation, and fertility" as cornerstones of religious practice. Wet places were focal points for rites, with ritual objects found thrown into rivers, lakes, and

In Europe, Bronze Age religion is well-studied and has well-understood recurring characteristics. Traits of European Bronze Age religion include a dichotomy between the sun and the underworld, a belief in animals as significant mediators between the physical and spiritual realms, and a focus on "travel, transformation, and fertility" as cornerstones of religious practice. Wet places were focal points for rites, with ritual objects found thrown into rivers, lakes, and  Iron Age European religion is known in part through literary sources, as the ancient Romans described the practices of the non-writing societies they encountered. From Roman description, it appears that the people of

Iron Age European religion is known in part through literary sources, as the ancient Romans described the practices of the non-writing societies they encountered. From Roman description, it appears that the people of

The degree to which reconstructionism focuses on European "ancestral" religions is a matter of some controversy. The pagan author Marisol Charbonneau argues European pagan reconstructionism "carries notions of implicit ethnic and cultural allegiance" regardless of the practitioner's thoughts and intent; she in part ascribes the lack of communication between mostly-white neopagan practitioners and mostly-nonwhite followers of recent immigrant spiritual practices to this implication. Not all prehistoric reconstructionism is centred on European tradition; for instance, neo-shamanism is generally interpreted as having a specifically non-Western background. Heathenry poses particular problems for this issue. One of the fastest-growing religious movements in Northern Europe and elsewhere, practitioners fear it being co-opted by

The degree to which reconstructionism focuses on European "ancestral" religions is a matter of some controversy. The pagan author Marisol Charbonneau argues European pagan reconstructionism "carries notions of implicit ethnic and cultural allegiance" regardless of the practitioner's thoughts and intent; she in part ascribes the lack of communication between mostly-white neopagan practitioners and mostly-nonwhite followers of recent immigrant spiritual practices to this implication. Not all prehistoric reconstructionism is centred on European tradition; for instance, neo-shamanism is generally interpreted as having a specifically non-Western background. Heathenry poses particular problems for this issue. One of the fastest-growing religious movements in Northern Europe and elsewhere, practitioners fear it being co-opted by

Prehistoric religion is the

Prehistoric religion is the religious

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

practice of prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The us ...

cultures. Prehistory, the period before written records, makes up the bulk of human experience; over 99% of human history occurred during the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

alone. Prehistoric cultures spanned the globe and existed for over two and a half million years; their religious practices were many and varied, and the study of them is difficult due to the lack of written records describing the details of their faiths.

The cognitive capacity for religion likely first emerged in ''Homo sapiens sapiens'', or anatomically modern humans

Early modern human (EMH) or anatomically modern human (AMH) are terms used to distinguish '' Homo sapiens'' (the only extant Hominina species) that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from exti ...

, although some scholars posit the existence of Neanderthal religion and sparse evidence exists for earlier ritual practice. Excluding sparse and controversial evidence in the Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleol ...

(300,00050,000 years ago), religion emerged with certainty in the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

around 50,000 years ago. Upper Paleolithic religion was possibly shaman

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spir ...

ic, oriented around the phenomenon of special spiritual leaders entering trance states to receive esoteric spiritual knowledge. These practices are extrapolated based on the rich and complex body of art left behind by Paleolithic artists, particularly the elaborate cave art

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 ye ...

and enigmatic Venus figurine

A Venus figurine is any Upper Palaeolithic statuette portraying a woman, usually carved in the round.Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", ''The Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', 1996, Oxford University Press, pp. 740–741 Most ...

s they produced.

The Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an inc ...

, which established agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

as the dominant lifestyle, occurred around 12,000 BC and ushered in the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

. Neolithic society grew hierarchical and inegalitarian compared to its Paleolithic forebears, and their religious practices likely changed to suit. Neolithic religion may have become more structural and centralised than in the Paleolithic, and possibly engaged in ancestor worship both of one's individual ancestors and of the ancestors of entire groups, tribes, and settlements. One famous feature of Neolithic religion were the stone circles of the British Isles, of which the best known today is Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connec ...

. A particularly well-known area of late Neolithic through Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "Rock (geology), stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''wikt:aeneus, aeneus'' "of copper"), is an list of archaeologi ...

religion is Proto-Indo-European mythology

Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the hypothetical speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language. Although the mythological motifs are not directly attested � ...

, the religion of the people who first spoke the Proto-Indo-European language

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-E ...

, which has been partially reconstructed through shared religious elements between early Indo-European language speakers.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

religions are understood in part through archaeological records, but also, more so than Paleolithic and Neolithic, through written records; some societies had writing in these ages, and were able to describe those which did not. These eras of prehistoric religion see particular cultural focus today by modern reconstructionists, with many pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

faiths today based on the pre-Christian practices of protohistoric

Protohistory is a period between prehistory and history during which a culture or civilization has not yet developed writing, but other cultures have already noted the existence of those pre-literate groups in their own writings. For example, ...

Bronze and Iron Age societies.

Background

Prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The us ...

is the period in human history before written records. The lack of written evidence demands the use of archaeological evidence, which makes it difficult to extrapolate conclusive statements about religious belief. Much of the study of prehistoric religion is based on inferences from historic (textual) and ethnographic

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject ...

evidence, for example analogies between the religion of Palaeolithic and modern hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

societies. The usefulness of analogy in archaeological reasoning is theoretically complex and contested, but in the context of prehistoric religion can be strengthened by circumstantial evidence; for instance, it has been observed that red ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

was significant to many prehistoric societies and to modern hunter-gatherers.

Religion exists in all human cultures, but the study of prehistoric religion was only popularised around the end of the nineteenth century. A founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, us ...

in prehistoric archaeology, a field pioneered by nineteenth-century secular humanists who found religion a threat to their evolution-based field of study, may have impeded the early attribution of a religious motive to prehistoric humans.

Prehistoric religion differs from the religious format known to most twenty-first century commentators, based around orthodox belief and scriptural

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

study. Rather, prehistoric religion, like later hunter-gatherer religion, possibly drew from shamanism

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiri ...

and ecstatic experience, as well as animism

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning ' breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things— animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather syst ...

, though analyses indicate animism may have emerged earlier. Though the nature of prehistoric religion is so speculative, the evidence left in the archaeological record is strongly suggestive of a visionary framework where faith is practised through entering trances, personal experience with deities, and other hallmarks of shamanismto the point of some authors suggesting, in the words of archaeologist of shamanism Neil Price, that these tendencies and techniques are in some way hard-wired into the human mind.

Human evolution

The question of when religion emerged in the evolving human psyche has sparked the curiosity of paleontologists for decades. On the whole, neither the archaeological record nor the current understanding of how human intelligence evolved suggests early

The question of when religion emerged in the evolving human psyche has sparked the curiosity of paleontologists for decades. On the whole, neither the archaeological record nor the current understanding of how human intelligence evolved suggests early hominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The ...

s had the cognitive capacity for spiritual belief. Religion was certainly present during the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

period, dating to about 50,000 through 12,000 years ago, while religion in the Lower and Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleol ...

"belongs to the realm of legend".

In early research, ''Australopithecus

''Australopithecus'' (, ; ) is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genus ''Homo'' (which includes modern humans) emerged within ''Australopithecus'', as sister to e.g. ''Australo ...

'', the first hominins to emerge in the fossil record, were thought to have sophisticated hunting patterns. These hunting patterns were extrapolated from those of modern hunter-gatherers, and in turn anthropologists and archaeologists pattern-matched ''Australopithecus'' and peers to the complex ritual surrounding such hunts. These assumptions were later disproved, and evidence suggesting ''Australopithecus'' and peers were capable of using tools such as fire deemed coincidental; for several decades, prehistoricist consensus has opposed the idea of an ''Australopithecus'' faith. The first evidence of ritual emerges in the hominin genus ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus '' Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely rela ...

,'' which emerged between 23 million years ago and includes modern humans, their ancestors and closest relatives.

The exact question of when ritual shaded into religious faith evades simple answer. The Lower and Middle Paleolithic periods, dominated by early ''Homo'' hominins, were an extraordinarily long period (from the emergence of ''Homo'' until 50,000 years before the present) of apparent cultural stability. No serious evidence for religious practice exists amongst ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly ...

'', the first hominin to use tools. The picture complicates as ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor ...

'' emerges. ''H. erectus'' was the point where hominins seem to have developed an appreciation for ritual, the intellectual ability to stem aggression of the kind seen in modern chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative t ...

s, and a sense of moral responsibility. Though the emergence of ritual in ''H. erectus'' "should not be understood as the full flowering of religious capacity", it marked a qualitative and quantitative change to its forebears. An area of particular scholarly interest is the evidence base for cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

and ritual mutilation amongst ''H. erectus''. Skulls found in Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

and at the Chinese Zhoukoudian

Zhoukoudian Area () is a town and an area located on the east Fangshan District, Beijing, China. It borders Nanjiao and Fozizhuang Townships to its north, Xiangyang, Chengguan and Yingfeng Subdistricts to its east, Shilou and Hangcunhe Towns t ...

archaeological site bear evidence of tampering with the brain case of the skull in ways thought to correspond to removing the brain for cannibalistic purposes, as observed in hunter-gatherers. Perhaps more tellingly, in those sites and others a number of ''H. erectus'' skulls show signs suggesting that the skin and flesh was cut away from the skull in predetermined patterns. These patterns, unlikely to occur by coincidence, are associated in turn with ritual.

The lineage leading to

The lineage leading to anatomically modern human

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

s originated around 500,000 years before the present day. Modern humans are classified taxonomically as ''Homo sapiens sapiens

Human taxonomy is the classification of the human species (systematic name ''Homo sapiens'', Latin: "wise man") within zoological taxonomy. The systematic genus, '' Homo'', is designed to include both anatomically modern humans and extinct ...

''. This classification is controversial, as it goes against traditional subspecies classifications; no other hominins have been treated as uncontroversial members of ''H. sapiens''. The 2003 description of ''Homo sapiens idaltu

Herto Man refers to the 154,000 - 160,000-year-old human remains (''Homo sapiens'') discovered in 1997 from the Upper Herto member of the Bouri Formation in the Afar Triangle, Ethiopia. The discovery of Herto Man was especially significant at t ...

'' drew attention as a relatively clear case of a ''H. sapiens'' subspecies, but was disputed by authors such as Chris Stringer

Christopher Brian Stringer (born 1947) is a British physical anthropologist noted for his work on human evolution.

Biography

Growing up in a working-class family in the East End of London, Stringer's interest in anthropology began in primar ...

. Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an Extinction, extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ag ...

s in particular pose a taxonomic problem. The classification of Neanderthals, a close relative of anatomically modern humans, as ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis'' is a decades-long matter of dispute. Neanderthals and ''H. s. sapiens'' were able to interbreed, a trait associated with membership in the same species, and around 2% of the modern human genome is composed of Neanderthal DNA. However, strong negative selection existed against the direct offspring of Neanderthals and ''H. s. sapiens'', consistent with the reduced fertility seen in hybrid species such as mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two po ...

s; this has been used as recent argument against the classification of Neanderthals as a ''H. sapiens'' subspecies.

The study of Neanderthal ritual, as proxy and preface for religion, revolves around death and burial rites. The first undisputed burials, approximately 150,000 years ago, were performed by Neanderthals. The limits of the archaeological record stymie extrapolation from burial to funeral rites, though evidence of

The study of Neanderthal ritual, as proxy and preface for religion, revolves around death and burial rites. The first undisputed burials, approximately 150,000 years ago, were performed by Neanderthals. The limits of the archaeological record stymie extrapolation from burial to funeral rites, though evidence of grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods may be classed as a ...

and unusual markings on bones suggest funerary practices. In addition to funerals, a growing evidence base suggests Neanderthals made use of bodily ornamentation through pigments, feathers, and even claws. As such ornamentation is not preserved in the archaeological record, it is understood only by comparison to modern hunter-gatherers, where it often corresponds to rituals of spiritual significance. Unlike ''H. s. sapiens'' over equivalent periods, Neanderthal society as preserved in the archaeological record is one of remarkable stability, with little change in tool design over hundreds of thousands of years; Neanderthal cognition, as backfilled from genetic and skeletal evidence, is thought rigid and simplistic compared to that of contemporary, let alone modern, ''H. s. sapiens''. By extension, Neanderthal ritual is speculated to have been a teaching mechanism that resulted in an unchanging culture, by embedding a learning style where orthopraxy

In the study of religion, orthopraxy is correct conduct, both ethical and liturgical, as opposed to faith or grace. Orthopraxy is in contrast with orthodoxy, which emphasizes correct belief. The word is a neoclassical compound— () meaning 'r ...

dominated in thought, life, and culture. This is contrasted with prehistoric ''H. s. sapiens'' religious ritual, which is understood as an extension of art, culture, and intellectual curiosity.

Archaeologists such as Brian Hayden interpret Neanderthal burial as suggestive of both belief in an afterlife and of ancestor worship

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of t ...

. Hayden also interprets Neanderthals as engaging in bear worship

Bear worship (also known as the bear cult or arctolatry) is the religious practice of the worshipping of bears found in many North Eurasian ethnic religions such as among the Sami, Nivkh, Ainu, Basques, Germanic peoples, Slavs and Finns. Ther ...

, a hypothesis driven by the common finding of cave bear remains around Neanderthal habitats and by the frequency of such worship amongst cold-dwelling hunter-gatherer societies. Cave excavations throughout the twentieth century found copious bear remains in and around Neanderthal habitats, including stacked skulls, bear bones around human graves, and patterns of skeletal remains consistent with animal skin displays. Other archaeologists, such as , find the evidence for the "bear cult" unconvincing. Wunn interprets Neanderthals as a pre-religious people, and the presence of bear remains around Neanderthal habitats as a coincidental association; as cave bears by their nature dwell in caves, their bones should be expected to be found there. The broader archaeological evidence overall suggests that bear worship was not a major factor of Paleolithic religion.

In recent years, genetic and neurological research has expanded the study of the emergence of religion. In 2018, the cultural anthropologist Margaret Boone Rappaport published her analysis of the sensory, neurological, and genetic differences between the great ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

s, Neanderthals, ''H. s. sapiens'', and ''H. s. idaltu''. She interprets the ''H. s. sapiens'' brain and genome as having a unique capacity for religion through characteristics such as expanded parietal lobe

The parietal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The parietal lobe is positioned above the temporal lobe and behind the frontal lobe and central sulcus.

The parietal lobe integrates sensory informa ...

s, greater cognitive flexibility, and an unusually broad capacity for both altruism and aggression. In Rappaport's framework, only ''H. s. sapiens'' of the hominins is capable of religion for much the same reason as the tools and artworks of prehistoric ''H. s. sapiens'' are finer and more detailed than those of their Neanderthal contemporaries; all are products of a unique cognition.

Paleolithic

The

The Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

, sometimes called the Old Stone Age, makes up over 99% of humanity's history. Lasting from approximately 2.5 million years ago through to 10,000 BC, the Paleolithic comprises the emergence of the ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus '' Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely rela ...

'' genus, the evolution of mankind, and the emergence of art, technology, and culture. The Paleolithic is broadly divided into Lower, Middle, and Upper periods. The Lower Paleolithic

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears i ...

(2.5 mya300,000 BC) sees the emergence of stone tools, the evolution of ''Australopithecus

''Australopithecus'' (, ; ) is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genus ''Homo'' (which includes modern humans) emerged within ''Australopithecus'', as sister to e.g. ''Australo ...

'', ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly ...

'', and ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor ...

'', and the first dispersal of humanity from Africa; the Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleol ...

(300,000 BC50,000 BC) the apparent beginnings of culture and art alongside the emergence of Neanderthals and anatomically modern human

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

s; the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

(50,000 BC10,000 BC) a sharp flourishing of culture, the emergence of sophisticated and elaborate art, jewellery, and clothing, and the worldwide dispersal of ''Homo sapiens sapiens''.

Lower Paleolithic

Religion prior to the Upper Paleolithic is speculative, and the Lower Paleolithic in particular has no clear evidence of religious practice. Not even the loosest evidence for ritual exists prior to 500,000 years before the present, though archaeologist Gregory J. Wightman notes the limits of the archaeological record means their practice cannot be thoroughly ruled out. The early hominins of the Lower Paleolithican era well before the emergence of ''H. s. sapiens''slowly gained, as they began to collaborate and work in groups, the ability to control and mediate their emotional responses. Their rudimentary sense of collaborative identity laid the groundwork for the later social aspects of religion. ''Australopithecus'', the first hominins, were a pre-religious people. Though twentieth-century historian of religion

''Australopithecus'', the first hominins, were a pre-religious people. Though twentieth-century historian of religion Mircea Eliade

Mircea Eliade (; – April 22, 1986) was a Romanian historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the University of Chicago. He was a leading interpreter of religious experience, who established paradigms in religiou ...

felt that even this earliest branch on the human evolutionary line "had a certain spiritual awareness", the twenty-first century's understanding of Australopithecene cognition does not permit the level of abstraction necessary for spiritual experience. For all that the hominins of the Lower Paleolithic are read as incapable of spirituality, some writers read the traces of their behaviour such as to permit an understanding of ritual, even as early as ''Australopithecus''. Durham University

, mottoeng = Her foundations are upon the holy hills ( Psalm 87:1)

, established = (university status)

, type = Public

, academic_staff = 1,830 (2020)

, administrative_staff = 2,640 (2018/19)

, chancellor = Sir Thomas Allen

, vice_cha ...

professor of archaeology Paul Pettitt reads the AL 333 fossils, a group of ''Australopithecus afarensis

''Australopithecus afarensis'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene of East Africa. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would no ...

'' found together near Hadar, Ethiopia, as perhaps deliberately moved to the area as a mortuary practice. Later Lower Paleolithic remains have also been interpreted as bearing associations of funerary rites, particularly cannibalism. Though archaeologist Kit W. Wesler states "there is no evidence in the Lower Paleolithic of the kind of cultural elaboration that would imply a rich imagination or the level of intelligence of modern humans", he discusses the findings of ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' (also ''H. sapiens heidelbergensis''), sometimes called Heidelbergs, is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human which existed during the Middle Pleistocene. It was subsumed as a subspecies of '' H. erectus'' i ...

'' bones at Sima de los Huesos and the evidence stretching from Germany to China for cannibal practices amongst Lower Paleolithic humans.

A number of skulls found in archaeological excavations of Lower Paleolithic sites across diverse regions have had significant proportions of the brain cases broken away. Writers such as Hayden speculate that this marks cannibalistic tendencies of religious significance; Hayden, deeming cannibalism "the most parsimonious explanation", compares the behaviour to hunter-gatherer tribes described in written records to whom brain-eating bore spiritual significance. By extension, he reads the skull's damage as evidence of Lower Paleolithic ritual practice. For the opposite position, Wunn finds the cannibalism hypothesis bereft of factual backing; she interprets the patterns of skull damage as a matter of what skeletal parts are more or less preserved over the course of thousands or millions of years. Even within the cannibalism framework, she argues that the practice would be more comparable to brain-eating in chimpanzees than in hunter-gatherers. In the 2010s, the study of Paleolithic cannibalism grew more complex due to new methods of archaeological interpretation, which led to the conclusion much Paleolithic cannibalism was for nutritional rather than ritual reasons.

In the Upper Paleolithic, religion is associated with symbolism and sculpture. One Upper Paleolithic remnant that draws cultural attention are the

In the Upper Paleolithic, religion is associated with symbolism and sculpture. One Upper Paleolithic remnant that draws cultural attention are the Venus figurine

A Venus figurine is any Upper Palaeolithic statuette portraying a woman, usually carved in the round.Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", ''The Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', 1996, Oxford University Press, pp. 740–741 Most ...

s, carved statues of nude women speculated to represent deities, fertility symbols, or ritual fetish objects. Archaeologists have proposed the existence of Lower Paleolithic Venus figurines. The Venus of Berekhat Ram is one such highly speculative figure, a scoria

Scoria is a pyroclastic, highly vesicular, dark-colored volcanic rock that was ejected from a volcano as a molten blob and cooled in the air to form discrete grains or clasts.Neuendorf, K.K.E., J.P. Mehl, Jr., and J.A. Jackson, eds. (2005) '' ...

dated 300350 kya with several grooves interpreted as resembling a woman's torso and head. Scanning electron microscopy found the Venus of Berekhat Ram's grooves consistent with those that would be produced by contemporary flint tools. Pettitt argues that though the figurine "can hardly be described as artistically achieved", it and other speculative Venuses of the Lower Paleolithic, such as the Venus of Tan-Tan

The Venus of Tan-Tan (supposedly, 500,000-300,000 BP) is an alleged artifact found in Morocco. It and its contemporary, the Venus of Berekhat Ram, have been claimed as the earliest representations of the human form.

Description

The Venus of T ...

, demand further scrutiny for their implications for contemporary theology. These figurines were possibly produced by ''H. heidelbergensis'', whose brain sizes were not far behind those of Neanderthals and ''H. s. sapiens'', and have been analysed for their implications for the artistic understanding of such early hominins.

The tail end of the Lower Paleolithic saw a cognitive and cultural shift. The emergence of revolutionary technologies such as fire, coupled with the course of human evolution extending development to include a true childhood and improved bonding between mother and infant, perhaps broke new ground in cultural terms. It is in the last few hundred thousand years of the period that the archaeological record begins to demonstrate hominins as creatures that influence their environment as much as they are influenced by it. Later Lower Paleolithic hominins built wind shelters to protect themselves from the elements; they collected unusual natural objects; they began the use of pigments such as red ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

. These shifts do not coincide with species-level evolutionary leaps, being observed in both ''H. heidelbergensis'' and ''H. erectus''. Different authors interpret these shifts with different levels of skepticism, some seeing them as a spiritual revolution and others as simply the beginning of the beginning. While the full significance of these changes is difficult to discern, they clearly map to an advance in cognitive capacity in the directions that would eventually lead to religion.

Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic was the era of coterminous Neanderthal and ''H. s. sapiens'' (

The Middle Paleolithic was the era of coterminous Neanderthal and ''H. s. sapiens'' (anatomically modern human

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

) habitation. ''H. s. sapiens'' originated in Africa and Neanderthals in Eurasia; over the course of the period, ''H. s. sapiens'' range expanded to areas formerly dominated by Neanderthals, eventually supplanting them and ushering in the Upper Paleolithic. Much is unknown about Neanderthal cognition, particularly the capacities that would give rise to religion. Religious interpretations of Neanderthals have discussed their possibly-ritual use of caves, their burial practices, and religious practices amongst ''H. s. sapiens'' hunter-gatherer tribes in recorded history considered to have similar lifestyles to Neanderthals. Pre-religious interpretations of Neanderthals argue their archaeological record suggests a lack of creativity or supernatural comprehension, that Neanderthal-associated archaeological findings are too quickly ascribed religious motive, and that the genetic and neurological remnants of Neanderthal skeletons do not permit the cognitive complexity required for religion.

While the Neanderthals dominated Europe, Middle Paleolithic ''H. s. sapiens'' ruled Africa. Middle Paleolithic ''H. s. sapiens'', like its Neanderthal contemporaries, bears little obvious trace of religious practice. The art, tools, and stylistic practice of the era's ''H. s. sapiens'' are not suggestive of the complexity necessary for spiritual belief and practice. However, the Middle Paleolithic is long, and the ''H. s. sapiens'' who lived in it heterogeneous. Models of behavioural modernity

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current ''Homo sapiens'' from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by ...

disagree on how humanity became behaviourally and cognitively sophisticated, whether as a sudden emergence in the Upper Paleolithic or a slow process over the last hundred thousand years of the Middle Paleolithic; supporters of the second hypothesis point to evidence of increasing cultural, ritual, and spiritual sophistication 150,00050,000 years ago.

Neanderthals

Neanderthals were the earliest hominins to bury their dead, although not the chronologically first burials, as earlier burials (such as those of the

Neanderthals were the earliest hominins to bury their dead, although not the chronologically first burials, as earlier burials (such as those of the Skhul and Qafzeh hominins

The Skhul/Qafzeh hominins or Qafzeh–Skhul early modern humans are hominin fossils discovered in Es-Skhul and Qafzeh caves in Israel. They are today classified as ''Homo sapiens'', among the earliest of their species in Eurasia. Skhul Cave ...

) are recorded amongst early ''H. s. sapiens''. Though relatively few Neanderthal burials are known, spaced thousands of years apart over broad geographical ranges, Hayden argues them undeniable hallmarks of spiritual recognition and "clear indications of concepts of the afterlife". Though Pettitt is more cautious about the significance of Neanderthal burial, he deems it a sophisticated and "more than prosaic" practice. Pettitt deems the Neanderthals of at least southwest France, Germany, and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

possessive of clear mortuary rites he presumes linked to an underlying belief system. He calls particular attention to potential grave markers found around Neanderthal burials, particularly those of children, at La Ferrassie in Dordogne

Dordogne ( , or ; ; oc, Dordonha ) is a large rural department in Southwestern France, with its prefecture in Périgueux. Located in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region roughly half-way between the Loire Valley and the Pyrenees, it is named ...

.

One matter discussed in the context of Neanderthal burial is grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods may be classed as a ...

, objects placed in graves that are frequently seen in early religious cultures. Outside of the controversial Shanidar IV "flower burial", now considered coincidence, Neanderthals are not seen to bury their dead with grave goods. However, a burial of an adult and child of the Kizil-Koba culture Kizil-Koba is a Middle Paleolithic culture belonging to a people who lived in the 9th–8th millennia BC in the Eastern Crimean territory and ancestral to Tauri. It is known as the first Eastern European settlement, where Neanderthal remains were fo ...

was accompanied by a flint stone with markings. In 2018, a team at the French National Centre for Scientific Research

The French National Centre for Scientific Research (french: link=no, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, CNRS) is the French state research organisation and is the largest fundamental science agency in Europe.

In 2016, it employed 31,63 ...

published their analysis that the markings were intentionally made and possibly held symbolic significance.

The archaeological record preserves Neanderthal associations with red pigments and quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical f ...

crystals. Hayden states "it is inconceivable to me that early hunting and gathering groups would have been painting images or decorating their bodies without some kind of symbolic or religious framework for such activities"; he draws comparison to the use of red ochre amongst those modern hunter-gatherers to whom it represents a sacred colour. He similarly connects quartz collection to religious use of crystals in later shamanic practice. Not all writers are as convinced that this represents underlying spiritual experience. To Mark Nielsen, evidence of ritual practice amongst Neanderthals does not represent religion; he interprets their cultural remnants, such as the rare cave art they produced, as insufficiently sophisticated for such comprehension. Rather, Neanderthal orthopraxy

In the study of religion, orthopraxy is correct conduct, both ethical and liturgical, as opposed to faith or grace. Orthopraxy is in contrast with orthodoxy, which emphasizes correct belief. The word is a neoclassical compound— () meaning 'r ...

is a cultural teaching mechanism that permitted their unusually stable culture, existing at the same technological level for hundreds of thousands of years during rapid ''H. s. sapiens'' change. To Nielsen, Neanderthal ritual is how they preserved an intractable culture via teachings passed down through generations.

Ultimately, Neanderthal religion is speculative, and hard evidence for religious practice exists only amongst Upper Paleolithic ''H. s. sapiens''. Though Hayden and to some degree Pettitt take a spiritualised interpretation of Neanderthal culture, these interpretations are unclear at best; as Pettitt says, "the very real possibility exists that religion ''sensu stricto'' is a unique characteristic of symbolically and linguistically empowered ''Homo sapiens''". Other writers, such as Wunn, find the concept of Neanderthal religion "mere speculation" that at best is an optimistic interpretation of the archaeological record. What ritual Neanderthals had, rather than supernatural, is oft interpreted as a mechanism of teaching and social bonding. Matt J. Rossano, defining Neanderthal practice as "proto-religion", compares it to "purely mimetic community activities" such as marching, sports, and concerts. He understands it not as a veneration of spirits or deities, but rather a bonding and social ritual that would later evolve into supernatural faith.

In 2019 Gibraltarian palaeoanthropologists Stewart, Geraldine and Clive Finlayson and Spanish archaeologist Francisco Guzmán speculated that the golden eagle had iconic value to Neanderthals, as exemplified in some modern human societies because they reported that golden eagle bones had a conspicuously high rate of evidence of modification compared to the bones of other birds. They then proposed some "Cult of the Sun Bird" where the golden eagle was a symbol of power.

''Homo sapiens sapiens''

''H. s. sapiens'' emerged in Africa as early as 300,000 years ago. In the Middle Paleolithic, particularly its first couple hundred thousand years, the archaeological record of ''H. s. sapiens'' is barely distinguishable from their Neanderthal and ''H. heidelbergensis'' contemporaries. Though these first ''H. s. sapiens'' demonstrated some ability to construct shelter, use pigments, and collect artifacts, they yet lacked the behavioural sophistication associated with humans today. The process through which ''H. s. sapiens'' became cognitively and culturally sophisticated is known as

''H. s. sapiens'' emerged in Africa as early as 300,000 years ago. In the Middle Paleolithic, particularly its first couple hundred thousand years, the archaeological record of ''H. s. sapiens'' is barely distinguishable from their Neanderthal and ''H. heidelbergensis'' contemporaries. Though these first ''H. s. sapiens'' demonstrated some ability to construct shelter, use pigments, and collect artifacts, they yet lacked the behavioural sophistication associated with humans today. The process through which ''H. s. sapiens'' became cognitively and culturally sophisticated is known as behavioural modernity

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current ''Homo sapiens'' from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by ...

. The emergence of behavioural modernity is unclear; traditionally conceptualised as a sudden shock around the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic, modern accounts more often understand it as a slow process throughout the late Middle.

Where behavioural modernity is conceptualised as originating in the Middle Paleolithic, some authors also push back the traditional framework of religion's origin to account for it. Wightman discusses Wonderwerk Cave

Wonderwerk Cave is an archaeological site, formed originally as an ancient solution cavity in dolomite rocks of the Kuruman Hills, situated between Danielskuil and Kuruman in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa. It is a National Heritage ...

in South Africa, inhabited 180,000 years ago by early ''H. s. sapiens'' and filled with unusual objects such as quartz crystals and inscribed stones. He argues these may have been ritual artifacts that served as foci for rites performed by these early humans. Wightman is even more enraptured by the Botswanan Tsodilo

The Tsodilo Hills are a UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS), consisting of rock art, rock shelters, depressions, and caves in southern Africa. It gained its WHS listing in 2001 because of its unique religious and spiritual significance to local peo ...

sacred to modern hunter-gathererswhich primarily houses Upper Paleolithic paintings and artifacts, but has objects stretching back far earlier. Middle Paleolithic spearheads have been found in Tsodilo's Rhino Cave, many of which were distinctly painted and some of which had apparently travelled long distances with nomadic hunter-gatherers. Rhino Cave presents unusual rock formations that modern hunter-gatherers understand as spiritually significant, and Wightman hypothesises this sense may have been shared by their earliest forebears. He is also curious about the emergence of cave art towards the very end of the Middle Paleolithic, where drawings and traces of red ochre finally emerge 50,000 years ago; this art, the first remnants of true human creativity, would usher in the Upper Paleolithic and the birth of complex religion.

Upper Paleolithic

The emergence of the Upper Paleolithic 40,00050,000 years ago was a time of explosive development. The Upper Paleolithic saw the worldwide emergence of ''H. s. sapiens'' as the sole species of humanity, displacing their Neanderthal contemporaries across Eurasia and travelling to previously human-uninhabited territories such as Australia. The complexity of stone tools grew, and the production of complex art, sculpture, and decoration began. Long-distance trade networks emerged to connect communities that had complex house-like habitations and food storage networks. True religion made its clear emergence during this period of flourishing. Rossano, following in the footsteps of other authors, ascribes this toshamanism

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiri ...

. He draws a line between pre-Upper Paleolithic social bonding rituals and faith healing

Faith healing is the practice of prayer and gestures (such as laying on of hands) that are believed by some to elicit divine intervention in spiritual and physical healing, especially the Christian practice. Believers assert that the healin ...

, where the latter is an evolution of the former. Gesturing at the universality of faith healing concepts in hunter-gatherer societies throughout recorded history, as well as their tendencies to involve the altered states of consciousness

An altered state of consciousness (ASC), also called altered state of mind or mind alteration, is any condition which is significantly different from a normal waking state. By 1892, the expression was in use in relation to hypnosis, though there ...

ascribed to shamanism and their placebo effect

A placebo ( ) is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value. Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like Saline (medicine), saline), sham surgery, and other procedures.

In general ...

on psychologically inspired pain, he conjectures that these rituals were the first truly supernatural tendency to reveal itself to the human psyche. Price refers to an extension of this as the "neuropsychological model", where shamanism is conceptualised as hard-wired in the human mind. Though some authors are unsympathetic to the neuropsychological model, Price finds a strong basis for some psychological underpinning to shamanism.

Art

Upper Paleolithic humans produced complex paintings, sculptures, and other artforms, much of which held apparent ritual significance. Religious interpretations of such objects, especially "portable art" such as figurines, varies. Some writers understand virtually all such art as spiritual, while others read only a minority as such, preferring more mundane functions for the majority. The study of religious art in the Upper Paleolithic focuses in particular oncave art

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 ye ...

referred to alternatively by some writers (such as David S. Whitley) as "rock art", as not all of it was produced on cave walls rather than rock formations elsewhere. Cave art is frequently conceptualised as a tool of shamanism. This model, the "mind in the cave" conjecture, sees much cave art as produced in altered states of consciousness as a tool to connect the artist with the spirit realm. Visionary cave art, as shamanic art is referred to, is characterised by unnatural imagery such as animal-human hybrids, and by recurring themes such as sex, death, flight, and physical transformation.

Not all religious cave art depicts shamanic experience. Cave art is also connected, by analogy with modern hunter-gatherers, to initiation rituals; a painting that depicts an animal to most members of a tribe may have a deeper symbolic meaning to those involved in smaller secret societies

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ...

. Comparative evidence for this form of cave art is difficult to gather, as secret societies by definition do not share their nature with outsider anthropologists. In some cases, the lifestyles of modern hunter-gatherers have been rendered so peripheral as to lose that knowledge entirely. Nonetheless, these arts are still studied, and general ideas can still be concluded; concepts associated with secret society cave art include ancestor figures, animals as metaphors, and long-distance travel.

Another art form of probable religious significance are the

Another art form of probable religious significance are the Venus figurine

A Venus figurine is any Upper Palaeolithic statuette portraying a woman, usually carved in the round.Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", ''The Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', 1996, Oxford University Press, pp. 740–741 Most ...

s. These are hand-held statuettes of nude women found in Upper Paleolithic sites across Eurasia, speculated to hold significance to fertility rites. Though separated by thousands of years and kilometres, Venus figurines across the Upper Paleolithic share consistent features. They focus on the midsections of their subjects; the faces are blank or abstract, and the hands and feet small. Despite the near-nonexistence of obesity

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it may negatively affect health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's ...

amongst hunter-gatherers, many depict realistically rendered obese subjects. The figures are universally women, often nude, and frequently pregnant.

Interpretations of Venus figurines range from self-portraits to anti-climate-change charms to matriarchal representations of a mother goddess

A mother goddess is a goddess who represents a personified deification of motherhood, fertility goddess, fertility, creation, destruction, or the earth goddess who embodies the bounty of the earth or nature. When equated with the earth or t ...

. Hayden argues the fertility charm interpretation is most parsimonious; Venus figurines are oft found alongside other apparent fertility objects, such as phallic

A phallus is a penis (especially when Erection, erect), an object that resembles a penis, or a mimesis, mimetic image of an erect penis. In art history a figure with an erect penis is described as ithyphallic.

Any object that symbolically— ...

representations, and that secular interpretations in particular are implausible for such widespread objects. He similarly disagrees with the goddess symbolism, as seen in feminist anthropology, on the basis that contemporary hunter-gatherers that venerate female fertility often lack actual matriarchal structures. Indeed, in more recent hunter-gatherer societies, secret societies venerating female fertility are occasionally restricted to men. Contra the traditional fertility interpretation, Patricia C. Rice argues nonetheless that the Venuses are symbols of women throughout their lifetime, not just throughout reproduction, and that they represent a veneration of femaleness and femininity as a whole.

Sculpture more broadly is a significant part of Upper Paleolithic art and often analysed for its spiritual implications. Upper Paleolithic sculpture is frequently seen through the lenses of sympathetic magic and ritual healing. Sculptures found in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

have been analysed through such an understanding by comparison to more recent Siberian hunter-gatherers, who made figurines while ill to represent and ward off those illnesses. Venus figurines are not alone in terms of sexually explicit Paleolithic sculpture; around a hundred phallic representations are known, of which a significant proportion are circumcised

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topic ...

, dating the origin of that practice to the era. Sculptures of animals are also recorded, as are sculptures that appear to be part-human and part-animal. The latter especially are deemed spiritually significant and possibly shamanistic in intent, representing the transformation of their subjects in the spirit realm. Other interpretations of therianthropic

Therianthropy is the mythological ability of human beings to metamorphose into animals or hybrids by means of shapeshifting. It is possible that cave drawings found at Les Trois Frères, in France, depict ancient beliefs in the concept.

The b ...

sculpture include ancestor figures, totems, and gods. Though fully human sculptures in the Upper Paleolithic are generally female, those with mixed human and animal traits are near-universally male, across broad geographic and chronological ranges.

Burial

The Upper Paleolithic saw the advent of complex burials with lavish

The Upper Paleolithic saw the advent of complex burials with lavish grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods may be classed as a ...

. Burials seem to have been relatively uncommon in these societies, perhaps reserved for people of high social or religious status. Many of these burials seem to have been accompanied by large quantities of red ochre, but the matter of decomposition makes it difficult to discern whether such pigments were applied to flesh or bone. One remarkable case of a pigmented burial is that of Lake Mungo 3 in inland New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Australia; the ochre in which the body was found covered must have been transported for hundreds of kilometres, considering the distance between the burial and the nearest sources.

One of the most elaborate Upper Paleolithic burials known is that of Sungir 1, a middle-aged man buried at the Russian Sungir site. In good physical health at the time of his death, Sungir 1 seems to have been killed by human weaponry, an incision on his remains matching that which would be produced by contemporary stone blades. The body was doused in ochre, particularly around the head and neck, and adorned with ivory bead jewellery of around 3,000 beads. Twelve fox canine teeth surrounded his forehead, while twenty-five arm bands made of mammoth ivory were worn on his arms, and a single pendant made of stone laid on his chest. Two children or young teenagers were additionally interred near him; their bodies were similarly decorated, with thousands of mammoth ivory beads, antlers, mammoth-shaped ivory carvings, and ochre-covered bones of other humans. The children had abnormal skeletons, with one having short bowed legs and the other an unusual facial structure. Burials so elaborate clearly suggest some concept of an afterlife and are similar to shaman burials in cultures described in written records.

Burial is one of the major ways archaeologists understand past societies; in the words of Timothy Taylor, "there can be no clearer ''a priori'' demonstration of ritual in past societies than the archaeological uncovery of a formal human burial". Upper Paleolithic burials do not appear to represent an ordinary cross-section of the population. Rather, their subjects are unusual and extravagant. Three-quarters of Upper Paleolithic burials were of men, a significant proportion young or disabled, and many buried in shared tombs. They are frequently posed in unusual positions and buried with rich grave goods. Taylor supposes many of these dead were human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

s, excluded from the ordinary means of body disposal (he presumes cannibalism) and warded by talismans. Hayden rather speculates these were shamans or otherwise people whose religious prominence was in life, rather than death; he notes especially the frequency of physical disability, comparing it to the many shamans in recorded societies who were singled out for physical or psychological differences.

Beliefs and practices

Upper Paleolithic religions were presumably

Upper Paleolithic religions were presumably polytheist

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

, venerating multiple deities, as this form of religion predates monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfo ...

in recorded history. As well as polytheism, religions of the ancient worldthat is, those in recorded history closest chronologically to prehistoric religionfocused on orthopraxy

In the study of religion, orthopraxy is correct conduct, both ethical and liturgical, as opposed to faith or grace. Orthopraxy is in contrast with orthodoxy, which emphasizes correct belief. The word is a neoclassical compound— () meaning 'r ...

, or a focus on correct practice and ritual, rather than orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Church ...

, or a focus on correct faith and belief. This is in contrast to many mainstream modern faiths, such as Christianity, that move the focus to orthodoxy.

Shamanism

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiri ...

may have been a major part of Upper Paleolithic religion. Shamanism is a broad term referring to a range of spiritual experiences, practised at many times in many places. Broadly speaking, it refers to spiritual practice involving altered states of consciousness

An altered state of consciousness (ASC), also called altered state of mind or mind alteration, is any condition which is significantly different from a normal waking state. By 1892, the expression was in use in relation to hypnosis, though there ...

, where practitioners render themselves in ecstatic or extreme psychological states in order to commune with spirits or deities. The study of prehistoric shamanism is controversialso controversial that people debating each side of the argument have dubbed their interlocutors "shamaniacs" and "shamanophobes". The shamanistic interpretation of prehistoric religion is based in the "neuropsychological model", where shamanic experience is deemed an inherent function of the human brain. The symbols associated with shamanic art, such as animal-human hybrid figures, are suggested to originate from certain levels of trance. The neuropsychological model has been criticised; opponents refer to the relative rarity of some forms of art associated with it, to tendencies in modern shamanic cultures they find incompatible with it, and to the work of pre-model archaeologists who cautioned against shamanic interpretations.

A popular myth about prehistoric religion is

A popular myth about prehistoric religion is bear worship

Bear worship (also known as the bear cult or arctolatry) is the religious practice of the worshipping of bears found in many North Eurasian ethnic religions such as among the Sami, Nivkh, Ainu, Basques, Germanic peoples, Slavs and Finns. Ther ...

. Early scholars of prehistory, finding skeletons of the extinct cave bear

The cave bear (''Ursus spelaeus'') is a prehistoric species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene and became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Both the word "cave" and the scientific name ...

around Paleolithic habitats, drew the conclusion humans of the era worshipped or otherwise venerated the bears. The concept was pioneered by excavations in the late 1910s in Switzerland, where apparent deposits of cave bear bones from which paleontologists could not draw obvious function were interpreted ritualistically. The idea was debunked as early as the 1970s as a simple artefact of sedimentary deposits changing over thousands of years.

Another controversial hypothesis in Paleolithic faith is that it was oriented around goddess worship. Feminist analyses of prehistoricism interpret findings such as the Venus figurines as suggestive of fully realised goddesses. Marija Gimbutas

Marija Gimbutas ( lt, Marija Gimbutienė, ; January 23, 1921 – February 2, 1994) was a Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist known for her research into the Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures of " Old Europe" and for her Kurgan hypothesis ...

argued that, as evinced by Eurasian Venus figurines, the predominant deity in Paleolithic and Neolithic religion throughout Europe was a goddess with later subservient male deities. She supposed this religion was wiped out by steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate gras ...

invaders later in the Neolithic, prior to the beginning of the historical period. The broad geographic range of Venuses has also seen their goddess interpretation in other regions; for instance, Bret Hinsch proposes a line of descent from Venuses to historical Chinese goddess worship. The goddess hypothesis has been criticised for basis in a limited geographical range, and for not mapping onto similar observations seen in modern hunter-gatherers.

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic was the transitional period between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. In European archaeology, it traditionally refers to hunter-gatherers living after the end of the

The Mesolithic was the transitional period between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. In European archaeology, it traditionally refers to hunter-gatherers living after the end of the Pleistocene