Plato ( ; grc-gre,

Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a

Greek philosopher born in

Athens during the

Classical period in

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

. He founded the

Platonist school of thought and the

Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

, the first institution of higher learning on the European continent.

Along with his teacher,

Socrates, and his student,

Aristotle, Plato is a central figure in the

history of

Ancient Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

and the

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and

Middle Eastern philosophies descended from it. He has also shaped

religion and

spirituality

The meaning of ''spirituality'' has developed and expanded over time, and various meanings can be found alongside each other. Traditionally, spirituality referred to a religious process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape o ...

. The so-called

neoplatonism of his interpreter

Plotinus

Plotinus (; grc-gre, Πλωτῖνος, ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a philosopher in the Hellenistic tradition, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher wa ...

greatly influenced both

Christianity (through

Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical p ...

such as

Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

) and

Islamic philosophy (through e.g.

Al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Is ...

). In modern times,

Friedrich Nietzsche diagnosed Western culture as growing in the shadow of Plato (famously calling Christianity "Platonism for the masses"), while

Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He is best known as the defining figure of the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which today has found applicat ...

famously said: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of

footnotes to Plato."

Plato was an innovator of the written

dialogue and

dialectic forms in philosophy. He raised problems for what later became all the major areas of both

theoretical philosophy

The modern division of philosophy into theoretical philosophy and practical philosophyImmanuel Kant, ''Lectures on Ethics'', Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 41 ("On Universal Practical Philosophy"). Original text: Immanuel Kant, ''Kant’s G ...

and

practical philosophy The modern division of philosophy into theoretical philosophy and practical philosophyImmanuel Kant, ''Lectures on Ethics'', Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 41 ("On Universal Practical Philosophy"). Original text: Immanuel Kant, ''Kant’s Ges ...

. His most famous contribution is the

theory of Forms known by

pure reason

Speculative reason, sometimes called theoretical reason or pure reason, is theoretical (or logical, deductive) thought, as opposed to practical (active, willing) thought. The distinction between the two goes at least as far back as the ancient Gr ...

, in which Plato presents a solution to the

problem of universals

The problem of universals is an ancient question from metaphysics that has inspired a range of philosophical topics and disputes: Should the properties an object has in common with other objects, such as color and shape, be considered to exist be ...

, known as

Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at le ...

(also ambiguously called either

Platonic realism or

Platonic idealism

Platonic realism is the philosophical position that universals or abstract objects exist objectively and outside of human minds. It is named after the Greek philosopher Plato who applied realism to such universals, which he considered ideal ...

). He is also the namesake of

Platonic love and the

Platonic solids.

His own most decisive philosophical influences are usually thought to have been, along with Socrates, the

pre-Socratics Pythagoras,

Heraclitus and

Parmenides, although few of his predecessors' works remain extant and much of what we know about these figures today derives from Plato himself. Unlike the work of nearly all of his contemporaries, Plato's entire body of work is believed to have survived intact for over 2,400 years. Although their popularity has fluctuated, Plato's works have consistently been read and studied.

Biography

Early life

Birth and family

Little is known about Plato's early life and education. He belonged to an

aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

and influential family. According to a disputed tradition, reported by

doxographer Doxography ( el, δόξα – "an opinion", "a point of view" + – "to write", "to describe") is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term w ...

Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

, Plato's father

Ariston traced his descent from the

king of Athens

Before the Athenian democracy, the tyrants, and the Archons, the city-state of Athens was ruled by kings. Most of these are probably mythical or only semi-historical. The following lists contain the chronological order of the title King of Athens ...

,

Codrus

Codrus (; ; Greek: , ''Kódros'') was the last of the semi-mythical Kings of Athens (r. ca 1089– 1068 BC). He was an ancient exemplar of patriotism and self-sacrifice. He was succeeded by his son Medon, who it is claimed ruled not as king but ...

, and the king of

Messenia,

Melanthus In Greek mythology, Melanthus ( grc, Μέλανθος) was a king of Messenia and son of Andropompus and Henioche.

Mythology

Melanthus was among the descendants of Neleus (the Neleidae) expelled from Messenia, by the descendants of Heracles, ...

.

[Diogenes Laërtius, ''Life of Plato'', III]

•

• According to the ancient Hellenic tradition, Codrus was said to have been descended from the mythological deity

Poseidon.

Plato's mother was

Perictione Perictione ( grc-gre, Περικτιόνη ''Periktiónē''; fl. 5th century BC) was the mother of the Greek philosopher Plato.

She was a descendant of Solon, the Athenian lawgiver. Her illustrious family goes back to Dropides, archon of the year ...

, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian

lawmaker and

lyric poet

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

Solon, one of the

seven sages, who repealed the laws of

Draco

Draco is the Latin word for serpent or dragon.

Draco or Drako may also refer to:

People

* Draco (lawgiver) (from Greek: Δράκων; 7th century BC), the first lawgiver of ancient Athens, Greece, from whom the term ''draconian'' is derived

* ...

(except for the death penalty for

homicide).

[Diogenes Laërtius, ''Life of Plato'', I] Perictione was sister of

Charmides

Charmides (; grc-gre, Χαρμίδης), son of Glaucon, was an Athenian statesman who flourished during the 5th century BC.Debra Nails, ''The People of Plato'' (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), 90–94. An uncle of Plato, Charmides appears i ...

and niece of

Critias

Critias (; grc-gre, Κριτίας, ''Kritias''; c. 460 – 403 BC) was an ancient Athenian political figure and author. Born in Athens, Critias was the son of Callaeschrus and a first cousin of Plato's mother Perictione. He became a leading ...

, both prominent figures of the

Thirty Tyrants, known as the Thirty, the brief

oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

(404–403 BC), which followed on the collapse of Athens at the end of the

Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC).

•

• According to some accounts, Ariston tried to force his attentions on Perictione, but failed in his purpose; then the

god

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

appeared to him in a vision, and as a result, Ariston left Perictione unmolested.

[Apuleius, ''De Dogmate Platonis'', 1]

• Diogenes Laërtius, ''Life of Plato'', I

•

The exact time and place of Plato's birth are unknown. Based on ancient sources, most modern scholars believe that he was born in Athens or

Aegina between 429 and 423 BC, not long after the start of the Peloponnesian War. The traditional date of Plato's birth during the 87th or 88th

Olympiad, 428 or 427 BC, is based on a dubious interpretation of Diogenes Laërtius, who says, "When

ocrateswas gone,

lato

Lato ( grc, Λατώ, Latṓ) was an ancient city of Crete, the ruins of which are located approximately 3 km from the village of Kritsa.

History

The Dorian city-state was built in a defensible position overlooking Mirabello Bay betwee ...

joined

Cratylus

Cratylus ( ; grc, Κρατύλος, ''Kratylos'') was an ancient Athenian philosopher from the mid-late 5th century BCE, known mostly through his portrayal in Plato's dialogue '' Cratylus''. He was a radical proponent of Heraclitean philosophy ...

the Heracleitean and Hermogenes, who philosophized in the manner of Parmenides. Then, at twenty-eight, Hermodorus says,

lato

Lato ( grc, Λατώ, Latṓ) was an ancient city of Crete, the ruins of which are located approximately 3 km from the village of Kritsa.

History

The Dorian city-state was built in a defensible position overlooking Mirabello Bay betwee ...

went to

Euclides in Megara." However, as

Debra Nails argues, the text does not state that Plato left for Megara immediately after joining Cratylus and Hermogenes. In his ''

Seventh Letter'', Plato notes that his coming of age coincided with the taking of power by the Thirty, remarking, "But a youth under the age of twenty made himself a laughingstock if he attempted to enter the political arena." Thus, Nails dates Plato's birth to 424/423.

According to

Neanthes, Plato was six years younger than

Isocrates, and therefore was born the same year the prominent Athenian statesman

Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelop ...

died (429 BC).

Jonathan Barnes regards 428 BC as the year of Plato's birth.

The

grammarian

Grammarian may refer to:

* Alexandrine grammarians, philologists and textual scholars in Hellenistic Alexandria in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE

* Biblical grammarians, scholars who study the Bible and the Hebrew language

* Grammarian (Greco-Roman ...

Apollodorus of Athens

Apollodorus of Athens ( el, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος, ''Apollodoros ho Athenaios''; c. 180 BC – after 120 BC) son of Asclepiades, was a Greek scholar, historian, and grammarian. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon, Pan ...

in his ''Chronicles'' argues that Plato was born in the 88th Olympiad.

Both the ''

Suda'' and

Sir Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne (; 19 October 1605 – 19 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a ...

also claimed he was born during the 88th Olympiad.

Another legend related that, when Plato was an infant, bees settled on his lips while he was sleeping: an augury of the sweetness of style in which he would discourse about philosophy.

Besides Plato himself, Ariston and Perictione had three other children; two sons,

Adeimantus and

Glaucon

Glaucon (; el, Γλαύκων; c. 445 BC – 4th century BC), son of Ariston, was an ancient Athenian and Plato's older brother. He is primarily known as a major conversant with Socrates in the '' Republic''. He is also referenced briefly i ...

, and a daughter

Potone, the mother of

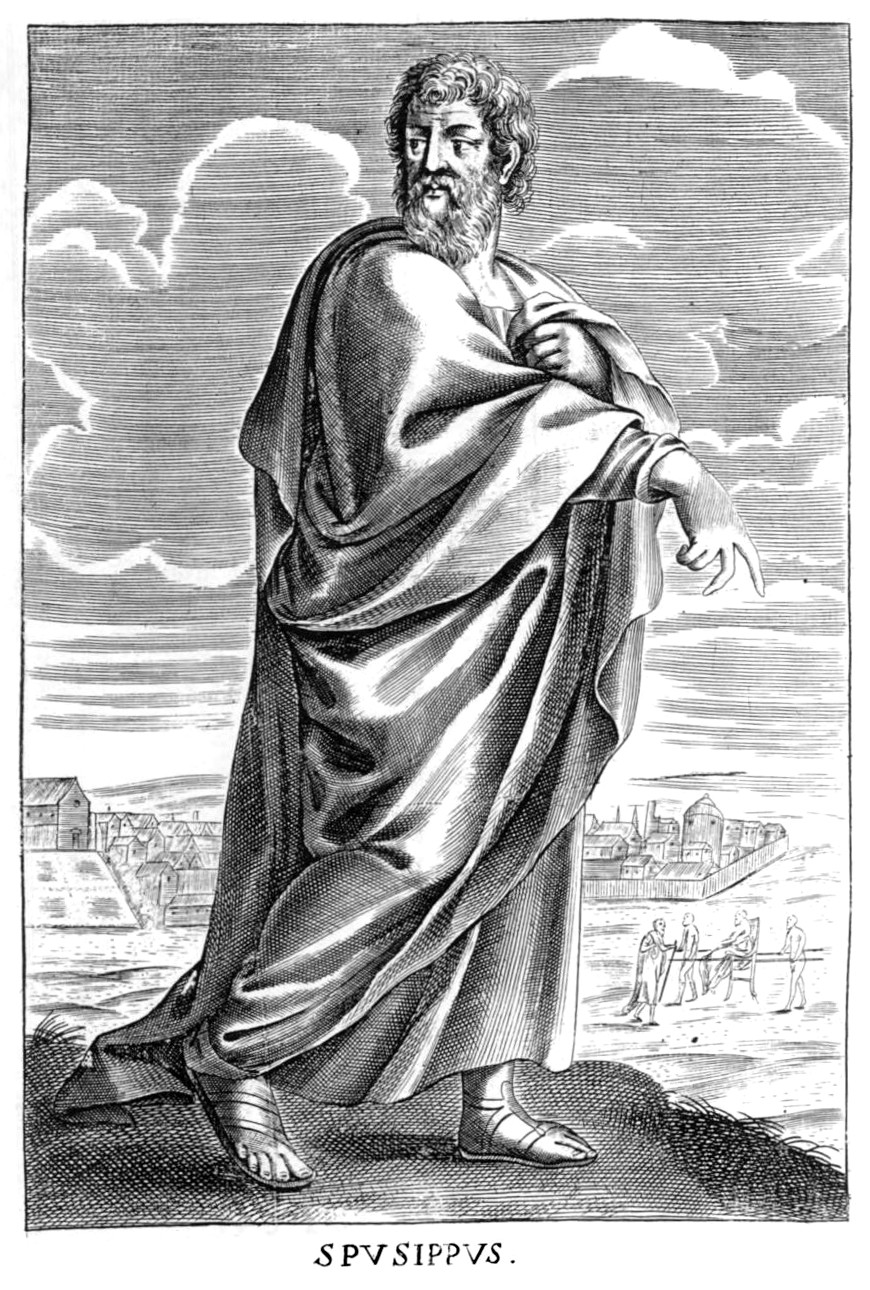

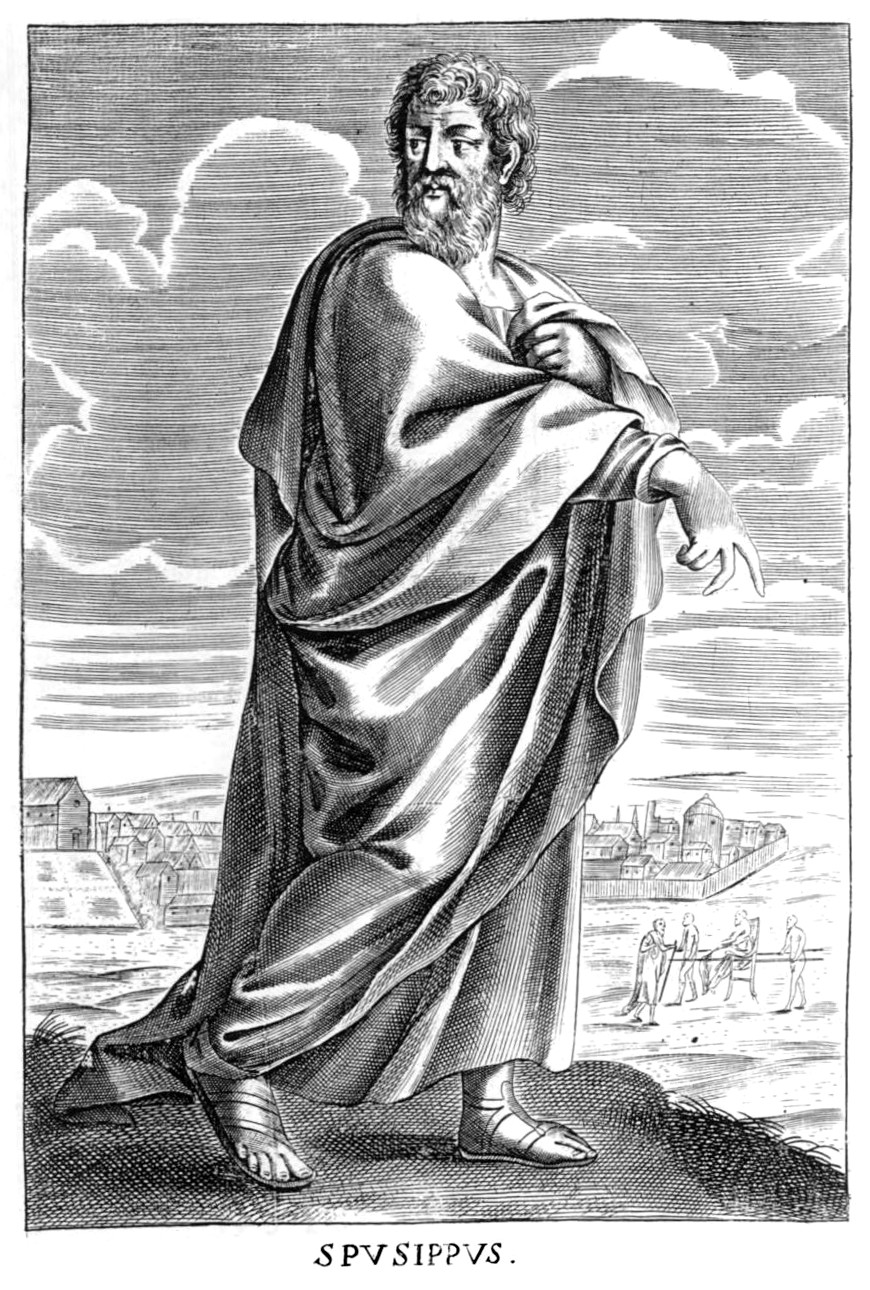

Speusippus (the nephew and successor of Plato as head of the ).

The brothers Adeimantus and Glaucon are mentioned in the ''

Republic'' as sons of Ariston,

[Plato, ''Republic']

368a

br />• and presumably brothers of Plato, though some have argued they were uncles. In a scenario in the ''

Memorabilia

A souvenir (), memento, keepsake, or token of remembrance is an object a person acquires for the memories the owner associates with it. A souvenir can be any object that can be collected or purchased and transported home by the traveler as a ...

'',

Xenophon confused the issue by presenting a Glaucon much younger than Plato.

Ariston appears to have died in Plato's childhood, although the precise dating of his death is difficult.

• Perictione then married

Pyrilampes Pyrilampes ( grc-gre, Πυριλάμπης) was an ancient Athenian politician and stepfather of the philosopher Plato. His dates of birth and death are unknown, but Debra Nails estimates he must have been born after 480 BC and died before 413 BC. ...

, her mother's brother,

[Plato, ''Charmides']

158a

br />• who had served many times as an ambassador to the

Persian court and was a friend of

Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelop ...

, the leader of the democratic faction in Athens.

[Plato, ''Charmides']

158a

br />• Plutarch, ''Pericles'', IV Pyrilampes had a son from a previous marriage, Demus, who was famous for his beauty. Perictione gave birth to Pyrilampes' second son, Antiphon, the half-brother of Plato, who appears in ''

Parmenides''.

[Plato, ''Parmenides']

126c

/ref>

In contrast to his reticence about himself, Plato often introduced his distinguished relatives into his dialogues or referred to them with some precision. In addition to Adeimantus and Glaucon in the ''Republic'', Charmides has a dialogue named after him; and Critias speaks in both ''Charmides

Charmides (; grc-gre, Χαρμίδης), son of Glaucon, was an Athenian statesman who flourished during the 5th century BC.Debra Nails, ''The People of Plato'' (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), 90–94. An uncle of Plato, Charmides appears i ...

'' and '' Protagoras''. These and other references suggest a considerable amount of family pride and enable us to reconstruct Plato's family tree

A family tree, also called a genealogy or a pedigree chart, is a chart representing family relationships in a conventional tree structure. More detailed family trees, used in medicine and social work, are known as genograms.

Representations o ...

. According to Burnet, "the opening scene of the ''Charmides'' is a glorification of the whole amilyconnection ... Plato's dialogues are not only a memorial to Socrates but also the happier days of his own family."

Name

The fact that the philosopher in his maturity called himself ''Platon'' is indisputable, but the origin of this name remains mysterious. ''Platon'' is a nickname from the adjective ''platýs'' () 'broad'. Although ''Platon'' was a fairly common name (31 instances are known from Athens alone), the name does not occur in Plato's known family line.[ Sedley, David, ''Plato's Cratylus'', Cambridge University Press 2003]

pp. 21–22

. The sources of Diogenes Laërtius account for this by claiming that his wrestling coach, Ariston of Argos, dubbed him "broad" on account of his chest and shoulders, or that Plato derived his name from the breadth of his eloquence, or his wide forehead.[Diogenes Laërtius, ''Life of Plato'', IV] While recalling a moral lesson about frugal living Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extra ...

mentions the meaning of Plato's name: "His very name was given him because of his broad chest."

His true name was supposedly Aristocles (), meaning 'best reputation'. According to Diogenes Laërtius, he was named after his grandfather, as was common in Athenian society. But there is only one inscription of an Aristocles, an early archon of Athens in 605/4 BC. There is no record of a line from Aristocles to Plato's father, Ariston. Recently a scholar has argued that even the name Aristocles for Plato was a much later invention.

His true name was supposedly Aristocles (), meaning 'best reputation'. According to Diogenes Laërtius, he was named after his grandfather, as was common in Athenian society. But there is only one inscription of an Aristocles, an early archon of Athens in 605/4 BC. There is no record of a line from Aristocles to Plato's father, Ariston. Recently a scholar has argued that even the name Aristocles for Plato was a much later invention.he idea that Aristocles was Plato's given name

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

as a mere invention of his biographers", noting how prevalent that account is in our sources.

Education

Ancient sources describe him as a bright though modest boy who excelled in his studies. Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern-day ...

informs us that Speusippus praised Plato's quickness of mind and modesty as a boy, and the "first fruits of his youth infused with hard work and love of study".[Apuleius, ''De Dogmate Platonis'', 2] His father contributed all which was necessary to give to his son a good education, and, therefore, Plato must have been instructed in grammar, music, and gymnastics by the most distinguished teachers of his time.[Diogenes Laërtius, ''Life of Plato'', IV]

• Plato invokes Damon many times in the ''Republic''. Plato was a wrestler, and Dicaearchus

Dicaearchus of Messana (; grc-gre, Δικαίαρχος ''Dikaiarkhos''; ), also written Dikaiarchos (), was a Greek philosopher, geographer and author. Dicaearchus was a student of Aristotle in the Lyceum. Very little of his work remains extan ...

went so far as to say that Plato wrestled at the Isthmian games.[Diogenes Laërtius, ''Life of Plato'', V] Plato had also attended courses of philosophy; before meeting Socrates, he first became acquainted with Cratylus and the Heraclitean doctrines.[Aristotle, ''Metaphysics'', ]

987a

Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promot ...

believed that Plato met Jeremiah in Egypt and was influenced by his ideas. Augustine initially accepted this claim, but later rejected it, arguing in ''The City of God

''On the City of God Against the Pagans'' ( la, De civitate Dei contra paganos), often called ''The City of God'', is a book of Christian philosophy written in Latin by Augustine of Hippo in the early 5th century AD. The book was in response ...

'' that "Plato was born a hundred years after Jeremiah prophesied."

Later life and death

Plato may have travelled in Italy, Sicily, Egypt, and Cyrene. Plato's own statement was that he visited Italy and Sicily at the age of forty and was disgusted by the sensuality of life there. Said to have returned to Athens at the age of forty, Plato founded one of the earliest known organized schools in Western Civilization on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus. This land was named after

Plato may have travelled in Italy, Sicily, Egypt, and Cyrene. Plato's own statement was that he visited Italy and Sicily at the age of forty and was disgusted by the sensuality of life there. Said to have returned to Athens at the age of forty, Plato founded one of the earliest known organized schools in Western Civilization on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus. This land was named after Academus

Academus or Akademos (; Ancient Greek: Ἀκάδημος), also Hekademos or Hecademus (Ἑκάδημος) was an Attic hero in Greek mythology. Academus, the place lies on the Cephissus, six stadia from Athens.

Place origins

Academus, the si ...

, an Attic

An attic (sometimes referred to as a ''loft'') is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building; an attic may also be called a ''sky parlor'' or a garret. Because attics fill the space between the ceiling of the ...

hero in Greek mythology. In historic Greek times it was adorned with oriental plane

''Platanus orientalis'', the Old World sycamore or Oriental plane, is a large, deciduous tree of the Platanaceae family, growing to or more, and known for its longevity and spreading crown. In autumn its deep green leaves may change to blood red ...

and olive plantations

The Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

was a large enclosure of ground about six stadia

Stadia may refer to:

* One of the plurals of stadium, along with "stadiums"

* The plural of stadion, an ancient Greek unit of distance, which equals to 600 Greek feet (''podes'').

* Stadia (Caria), a town of ancient Caria, now in Turkey

* Stadia ...

(a total of between a kilometer and a half mile) outside of Athens proper. One story is that the name of the comes from the ancient hero, Academus

Academus or Akademos (; Ancient Greek: Ἀκάδημος), also Hekademos or Hecademus (Ἑκάδημος) was an Attic hero in Greek mythology. Academus, the place lies on the Cephissus, six stadia from Athens.

Place origins

Academus, the si ...

; still another story is that the name came from a supposed former owner of the plot of land, an Athenian citizen whose name was (also) Academus; while yet another account is that it was named after a member of the army of Castor and Pollux

Castor; grc, Κάστωρ, Kástōr, beaver. and Pollux. (or Polydeukes). are twin half-brothers in Greek and Roman mythology, known together as the Dioscuri.; grc, Διόσκουροι, Dióskouroi, sons of Zeus, links=no, from ''Dîos'' ('Z ...

, an Arcadian named Echedemus. The operated until it was destroyed by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 84 BC. Many intellectuals were schooled in the , the most prominent one being Aristotle.

Throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

*Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

*Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

**North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

* Syracuse, Kansas

* Syracuse, Mi ...

. According to Diogenes Laërtius, Plato initially visited Syracuse while it was under the rule of Dionysius

The name Dionysius (; el, Διονύσιος ''Dionysios'', "of Dionysus"; la, Dionysius) was common in classical and post-classical times. Etymologically it is a nominalized adjective formed with a -ios suffix from the stem Dionys- of the name ...

. During this first trip Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse

Dion (; el, Δίων ὁ Συρακόσιος; 408–354 BC), tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily, was the son of Hipparinus, and brother-in-law of Dionysius I of Syracuse. A disciple of Plato, he became Dionysius I's most trusted minister and advis ...

, became one of Plato's disciples, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato almost faced death, but he was sold into slavery. Anniceris

Anniceris ( grc-gre, Ἀννίκερις; fl. 300 BC) was a Cyrenaic philosopher. He argued that pleasure is achieved through individual acts of gratification which are sought for the pleasure that they produce, but he also laid great emphasis on ...

, a Cyrenaic

The Cyrenaics or Kyrenaics ( grc, Κυρηναϊκοί, Kyrēnaïkoí), were a sensual hedonist Greek school of philosophy founded in the 4th century BCE, supposedly by Aristippus of Cyrene, although many of the principles of the school are bel ...

philosopher, subsequently bought Plato's freedom for twenty minas, and sent him home. After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's ''Seventh Letter'', Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, his uncle. Dionysius expelled Dion and kept Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse. Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and ruled Syracuse for a short time before being usurped by Calippus, a fellow disciple of Plato.

According to Seneca, Plato died at the age of 81 on the same day he was born. The Suda indicates that he lived to 82 years,Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

girl played the flute to him. Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account is based on Diogenes Laërtius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a third-century Alexandrian. According to Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of La ...

, Plato simply died in his sleep.

Plato owned an estate at Iphistiadae Iphistiadae ( grc, Ἰφιστιάδαι, Iphistiadai) or Hephaestiadae ( grc, Ἡφαιστιάδαι, Hephaistiadai) was one of the demes, or townships of Acamantis, one of the ten '' phylae'' of Attica established by Cleisthenes at the end of the ...

, which by will he left to a certain youth named Adeimantus, presumably a younger relative, as Plato had an elder brother or uncle by this name.

Influences

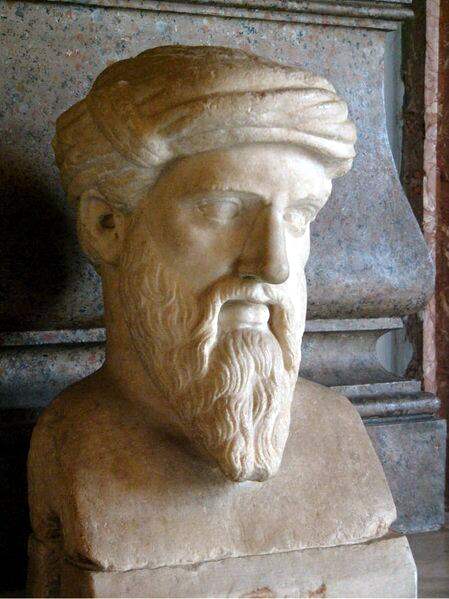

Pythagoras

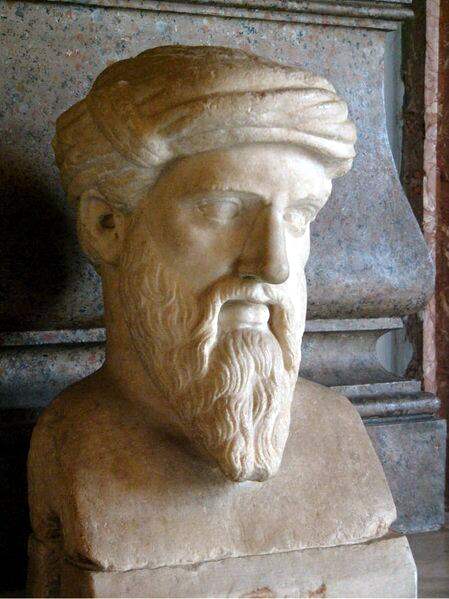

Although Socrates influenced Plato directly as related in the dialogues, the influence of Pythagoras upon Plato, or in a broader sense, the Pythagoreans, such as

Although Socrates influenced Plato directly as related in the dialogues, the influence of Pythagoras upon Plato, or in a broader sense, the Pythagoreans, such as Archytas

Archytas (; el, Ἀρχύτας; 435/410–360/350 BC) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, music theorist, astronomer, wikt:statesman, statesman, and military strategy, strategist. He was a scientist of the Pythagor ...

also appears to have been significant. Aristotle claimed that the philosophy of Plato closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans, and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

repeats this claim: "They say Plato learned all things Pythagorean." It is probable that both were influenced by Orphism, and both believed in metempsychosis, transmigration of the soul.

Pythagoras held that all things are number, and the cosmos comes from numerical principles. He introduced the concept of form as distinct from matter, and that the physical world is an imitation of an eternal mathematical world. These ideas were very influential on Heraclitus, Parmenides and Plato. Numenius accepted both Pythagoras and Plato as the two authorities one should follow in philosophy, but he regarded Plato's authority as subordinate to that of Pythagoras, whom he considered to be the source of all true philosophy—including Plato's own. For Numenius it is just that Plato wrote so many philosophical works, whereas Pythagoras' views were originally passed on only orally.

According to R. M. Hare

Richard Mervyn Hare (21 March 1919 – 29 January 2002), usually cited as R. M. Hare, was a British moral philosopher who held the post of White's Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford from 1966 until 1983. He subseque ...

, this influence consists of three points:

#The platonic Republic might be related to the idea of "a tightly organized community of like-minded thinkers", like the one established by Pythagoras in Croton.

#The idea that mathematics and, generally speaking, abstract thinking is a secure basis for philosophical thinking as well as "for substantial theses in science and morals

Morality () is the differentiation of intentions, decisions and actions between those that are distinguished as proper (right) and those that are improper (wrong). Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of cond ...

".

#They shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world".

Plato and mathematics

Plato may have studied under the mathematician Theodorus of Cyrene

Theodorus of Cyrene ( el, Θεόδωρος ὁ Κυρηναῖος) was an ancient Greek mathematician who lived during the 5th century BC. The only first-hand accounts of him that survive are in three of Plato's dialogues: the '' Theaetetus'', th ...

, and has a dialogue named for and whose central character is the mathematician Theaetetus. While not a mathematician, Plato was considered an accomplished teacher of mathematics. Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus (; grc, Εὔδοξος ὁ Κνίδιος, ''Eúdoxos ho Knídios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar, and student of Archytas and Plato. All of his original works are lost, though some fragments are ...

, the greatest mathematician in Classical Greece, who contributed much of what is found in Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ge ...

's '' Elements'', was taught by Archytas and Plato. Plato helped to distinguish between pure and applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a combination of mathematical ...

by widening the gap between "arithmetic", now called number theory and "logistic", now called arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th c ...

.

In the dialogue ''

In the dialogue ''Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

* Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Gree ...

'' Plato associated each of the four classical element

Classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had simila ...

s ( earth, air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing for ...

, water, and fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition ...

) with a regular solid ( cube, octahedron, icosahedron, and tetrahedron respectively) due to their shape, the so-called Platonic solids. The fifth regular solid, the dodecahedron, was supposed to be the element which made up the heavens.

Heraclitus and Parmenides

The two philosophers Heraclitus and Parmenides, following the way initiated by pre-Socratic Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras, depart from mythology and begin the metaphysical tradition that strongly influenced Plato and continues today.Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

, Plato received these ideas through Heraclitus' disciple Cratylus

Cratylus ( ; grc, Κρατύλος, ''Kratylos'') was an ancient Athenian philosopher from the mid-late 5th century BCE, known mostly through his portrayal in Plato's dialogue '' Cratylus''. He was a radical proponent of Heraclitean philosophy ...

, who held the more radical view that continuous change warrants scepticism

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the pe ...

because we cannot define a thing that does not have a permanent nature.Being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exi ...

and the view that change is an illusion.ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities ex ...

as a domain of inquiry distinct from theology."Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

, who, following Parmenides' denial of change, argued forcefully through his paradoxes to deny the existence of motion.

Plato's ''Sophist

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ...

'' dialogue includes an Eleatic stranger, a follower of Parmenides, as a foil for his arguments against Parmenides. In the dialogue, Plato distinguishes nouns and verbs, providing some of the earliest treatment of subject and predicate

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, o ...

. He also argues that motion and rest

Rest or REST may refer to:

Relief from activity

* Sleep

** Bed rest

* Kneeling

* Lying (position)

* Sitting

* Squatting position

Structural support

* Structural support

** Rest (cue sports)

** Armrest

** Headrest

** Footrest

Arts and entert ...

both "are", against followers of Parmenides who say rest is but motion is not.

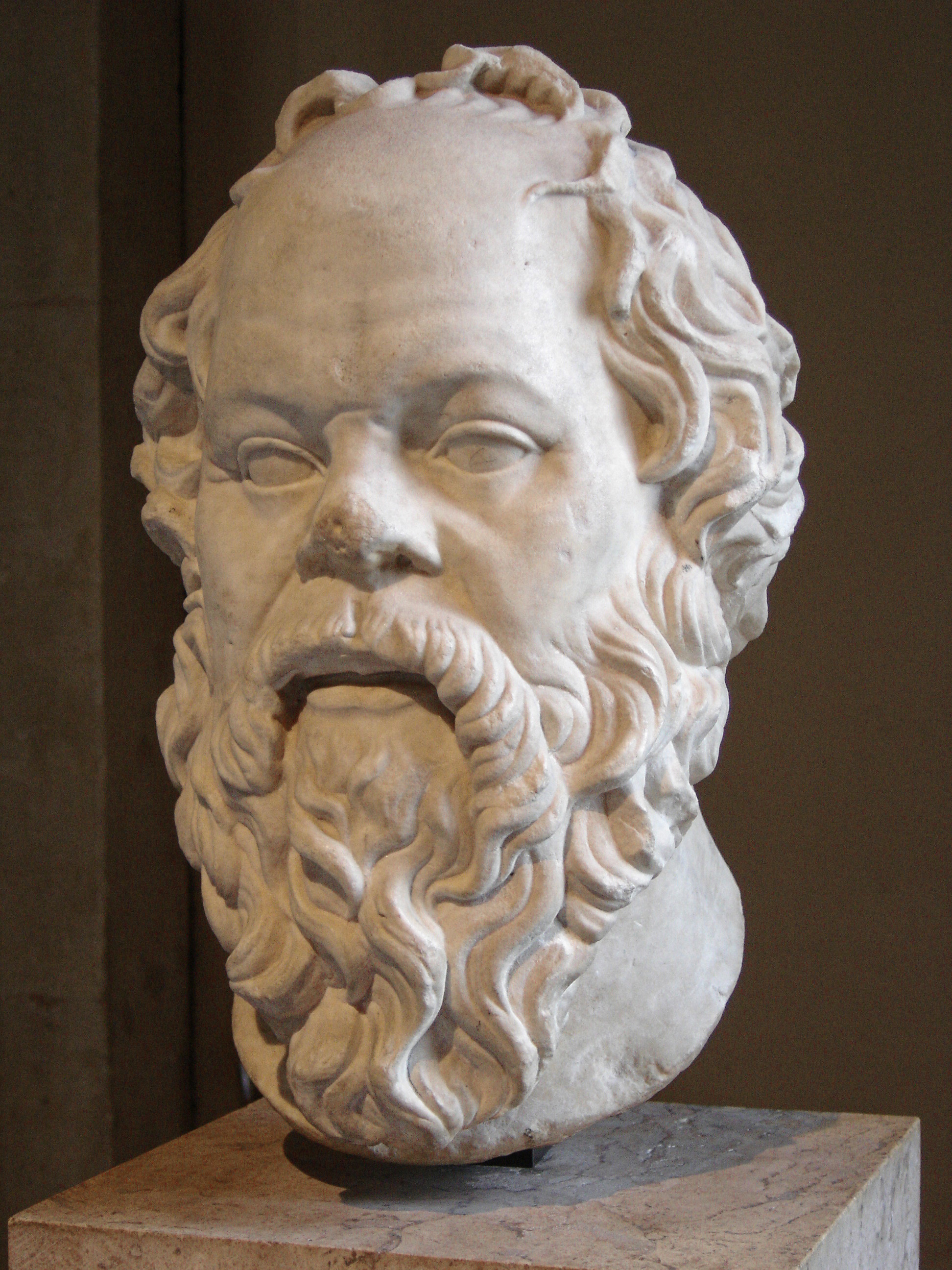

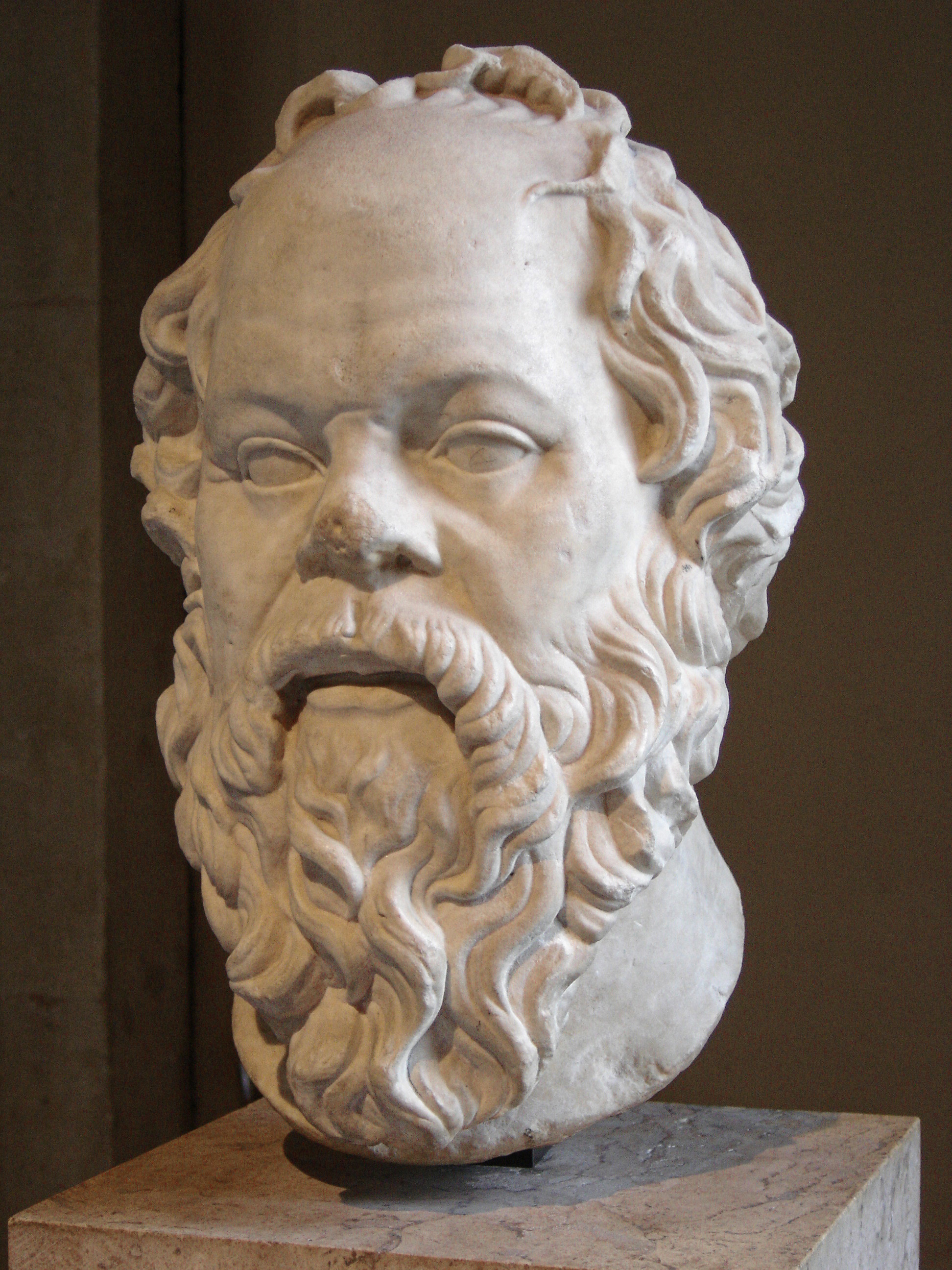

Socrates

Plato was one of the devoted young followers of Socrates. The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of contention among scholars.

Plato never speaks in his own voice in his dialogues; every dialogue except the ''

Plato was one of the devoted young followers of Socrates. The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of contention among scholars.

Plato never speaks in his own voice in his dialogues; every dialogue except the ''Laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. ...

'' features Socrates, although many dialogues, including the ''Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

* Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Gree ...

'' and '' Statesman'', feature him speaking only rarely. In the ''Second Letter'', it says, "no writing of Plato exists or ever will exist, but those now said to be his are those of a Socrates become beautiful and new"; if the letter is Plato's, the final qualification seems to call into question the dialogues' historical fidelity. In any case, Xenophon's ''Memorabilia

A souvenir (), memento, keepsake, or token of remembrance is an object a person acquires for the memories the owner associates with it. A souvenir can be any object that can be collected or purchased and transported home by the traveler as a ...

'' and Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his ...

's '' The Clouds'' seem to present a somewhat different portrait of Socrates from the one Plato paints. The Socratic problem

In historical scholarship, the Socratic problem (or Socratic question) concerns attempts at reconstructing a historical and philosophical image of Socrates based on the variable, and sometimes contradictory, nature of the existing sources on his l ...

concerns how to reconcile these various accounts. Leo Strauss

Leo Strauss (, ; September 20, 1899 – October 18, 1973) was a German-American political philosopher who specialized in classical political philosophy. Born in Germany to Jewish parents, Strauss later emigrated from Germany to the United States. ...

notes that Socrates' reputation for irony casts doubt on whether Plato's Socrates is expressing sincere beliefs.

Aristotle attributes a different doctrine with respect to Forms to Plato and Socrates. Aristotle suggests that Socrates' idea of forms can be discovered through investigation of the natural world, unlike Plato's Forms that exist beyond and outside the ordinary range of human understanding. In the dialogues of Plato though, Socrates sometimes seems to support a mystical side, discussing reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

and the mystery religions

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates ''(mystai)''. The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy as ...

, this is generally attributed to Plato. Regardless, this view of Socrates cannot be dismissed out of hand, as we cannot be sure of the differences between the views of Plato and Socrates. In the '' Meno,'' Plato refers to the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries ( el, Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια, Eleusínia Mystḗria) were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece. They are the "m ...

, telling Meno he would understand Socrates's answers better if he could stay for the initiations next week. It is possible that Plato and Socrates took part in the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Philosophy

Metaphysics

In Plato's dialogues, Socrates and his company of disputants had something to say on many subjects, including several aspects of metaphysics. These include religion and science, human nature, love, and sexuality. More than one dialogue contrasts perception and reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within a system, as opposed to that which is only imaginary. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence. In physical terms, rea ...

, nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

and custom, and body and soul. Francis Cornford

Francis Macdonald Cornford (27 February 1874 – 3 January 1943) was an English classical scholar and translator known for work on ancient philosophy, notably Plato, Parmenides, Thucydides, and ancient Greek religion. Frances Cornford, his wi ...

identified the "twin pillars of Platonism" as the theory of Forms, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the doctrine of immortality of the soul.

The Forms

"Platonism" and its theory of Forms (also known as 'theory of Ideas;) denies the reality of the material world, considering it only an image or copy of the real world. The theory of Forms is first introduced in the '' Phaedo'' dialogue (also known as ''On the Soul''), wherein Socrates refutes the pluralism of the likes of

"Platonism" and its theory of Forms (also known as 'theory of Ideas;) denies the reality of the material world, considering it only an image or copy of the real world. The theory of Forms is first introduced in the '' Phaedo'' dialogue (also known as ''On the Soul''), wherein Socrates refutes the pluralism of the likes of Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

, then the most popular response to Heraclitus and Parmenides, while giving the "Opposites Argument" in support of the Forms.

According to this theory of Forms, there are these two kinds of things: the apparent world of concrete objects, grasped by the senses, which constantly changes, and an unchanging and unseen world of Forms or abstract objects

In metaphysics, the distinction between abstract and concrete refers to a divide between two types of entities. Many philosophers hold that this difference has fundamental metaphysical significance. Examples of concrete objects include plants, hum ...

, grasped by pure reason

Speculative reason, sometimes called theoretical reason or pure reason, is theoretical (or logical, deductive) thought, as opposed to practical (active, willing) thought. The distinction between the two goes at least as far back as the ancient Gr ...

(), which ground what is apparent.

It can also be said there are three worlds, with the apparent world consisting of both the world of material objects and of mental images, with the "third realm" consisting of the Forms. Thus, though there is the term "Platonic idealism", this refers to Platonic Ideas or the Forms, and not to some platonic kind of idealism, an 18th-century view which sees matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic parti ...

as unreal in favour of mind. For Plato, though grasped by the mind, only the Forms are truly real.

Plato's Forms thus represent types of things, as well as properties

Property is the ownership of land, resources, improvements or other tangible objects, or intellectual property.

Property may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Property (mathematics)

Philosophy and science

* Property (philosophy), in philosophy and ...

, patterns, and relations, to which we refer as objects. Just as individual tables, chairs, and cars refer to objects in this world, 'tableness', 'chairness', and 'carness', as well as e. g. justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

, truth, and beauty

Beauty is commonly described as a feature of objects that makes these objects pleasurable to perceive. Such objects include landscapes, sunsets, humans and works of art. Beauty, together with art and taste, is the main subject of aesthetics, o ...

refer to objects in another world. One of Plato's most cited examples for the Forms were the truths of geometry, such as the Pythagorean theorem

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a fundamental relation in Euclidean geometry between the three sides of a right triangle. It states that the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite ...

.

In other words, the Forms are universals

In metaphysics, a universal is what particular things have in common, namely characteristics or qualities. In other words, universals are repeatable or recurrent entities that can be instantiated or exemplified by many particular things. For exa ...

given as a solution to the problem of universals, or the problem of "the One and the Many", e. g. how one predicate "red" can apply to many red objects. For Plato, this is because there is one abstract object or Form of red, redness itself, in which the several red things "participate". As Plato's solution is that universals are Forms and that Forms are real if anything is, Plato's philosophy is unambiguously called Platonic realism. According to Aristotle, Plato's best-known argument in support of the Forms was the "one over many" argument.

Aside from being immutable, timeless, changeless, and one over many, the Forms also provide definitions and the standard against which all instances are measured. In the dialogues Socrates regularly asks for the meaning – in the sense of intensional

Aside from being immutable, timeless, changeless, and one over many, the Forms also provide definitions and the standard against which all instances are measured. In the dialogues Socrates regularly asks for the meaning – in the sense of intensional definition

A definition is a statement of the meaning of a term (a word, phrase, or other set of symbols). Definitions can be classified into two large categories: intensional definitions (which try to give the sense of a term), and extensional definiti ...

s – of a general term (e. g. justice, truth, beauty), and criticizes those who instead give him particular, extensional In any of several fields of study that treat the use of signs — for example, in linguistics, logic, mathematics, semantics, semiotics, and philosophy of language — an extensional context (or transparent context) is a syntactic environment in wh ...

examples, rather than the quality shared by all examples.

There is thus a world of perfect, eternal, and changeless meanings of predicates, the Forms, existing in the realm of Being outside of space and time Space and Time or Time and Space, or ''variation'', may refer to:

* '' Space and time'' or ''time and space'' or ''spacetime'', any mathematical model that combines space and time into a single interwoven continuum

* Philosophy of space and time

S ...

; and the imperfect sensible world of becoming, subjects somehow in a state between being and nothing, that partakes of the qualities of the Forms, and is its instantiation.

The soul

For Plato, as was characteristic of ancient Greek philosophy, the soul was that which gave life. See this brief exchange from the ''Phaedo'': "What is it that, when present in a body, makes it living? — A soul."

Another hallmark of Plato's view of the soul is that it is what rules and controls a person's body. Plato uses this observation in the ''Alcibiades'' as evidence that people are their souls.

Plato advocates a belief in the immortality of the soul, and several dialogues end with long speeches imagining the afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving e ...

. In the ''Timaeus'', Socrates locates the parts of the soul within the human body: Reason is located in the head, spirit in the top third of the torso, and the appetite in the middle third of the torso, down to the navel.

Furthermore, Plato evinces in multiple dialogues (such as the ''Phaedo'' and ''Timaeus'') a belief in the theory of reincarnation. Scholars debate whether he intends the theory to be literally true, however.

Epistemology

Plato also discusses several aspects of epistemology. More than one dialogue contrasts knowledge (''episteme

In philosophy, episteme (; french: épistémè) is a term that refers to a principle system of understanding (i.e., knowledge), such as scientific knowledge or practical knowledge. The term comes from the Ancient Greek verb grc, ἐπῐ́σ� ...

'') and opinion ('' doxa''). Plato's epistemology involves Socrates (and other characters, such as Timaeus) arguing that knowledge is not empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

, and that it comes from divine insight. The Forms are also responsible for both knowledge or certainty, and are grasped by pure reason.

In several dialogues, Socrates inverts the common man's intuition about what is knowable and what is real. Reality is unavailable to those who use their senses. Socrates says that he who sees with his eyes is blind. While most people take the objects of their senses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who think that something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In the ''Theaetetus'', he says such people are ''eu amousoi'' (εὖ ἄμουσοι), an expression that means literally, "happily without the muses". In other words, such people are willingly ignorant, living without divine inspiration and access to higher insights about reality.

In Plato's dialogues, Socrates always insists on his ignorance and humility, that he knows nothing, so-called " Socratic irony." Several dialogues refute a series of viewpoints, but offer no positive position, thus ending in ''aporia

In philosophy, an aporia ( grc, ᾰ̓πορῐ́ᾱ, aporíā, literally: "lacking passage", also: "impasse", "difficulty in passage", "puzzlement") is a conundrum or state of puzzlement. In rhetoric, it is a declaration of doubt, made for rh ...

''.

Recollection

In several of Plato's dialogues, Socrates promulgates the idea that knowledge is a matter of recollection

Recall in memory refers to the mental process of retrieval of information from the past. Along with encoding and storage, it is one of the three core processes of memory. There are three main types of recall: free recall, cued recall and serial ...

of things acquainted with before one is born, and not of observation or study. Keeping with the theme of admitting his own ignorance, Socrates regularly complains of his forgetfulness. In the ''Meno'', Socrates uses a geometrical example to expound Plato's view that knowledge in this latter sense is acquired by recollection. Socrates elicits a fact concerning a geometrical construction from a slave boy, who could not have otherwise known the fact (due to the slave boy's lack of education). The knowledge must be of, Socrates concludes, an eternal, non-perceptible Form.

In other dialogues, the ''Sophist'', '' Statesman'', ''Republic'', ''Timaeus'', and the ''Parmenides'', Plato associates knowledge with the apprehension of unchanging Forms and their relationships to one another (which he calls "expertise" in dialectic), including through the processes of ''collection'' and ''division''. More explicitly, Plato himself argues in the ''Timaeus'' that knowledge is always proportionate to the realm from which it is gained. In other words, if one derives one's account of something experientially, because the world of sense is in flux, the views therein attained will be mere opinions. Meanwhile, opinions are characterized by a lack of necessity and stability. On the other hand, if one derives one's account of something by way of the non-sensible Forms, because these Forms are unchanging, so too is the account derived from them. That apprehension of Forms is required for knowledge may be taken to cohere with Plato's theory in the ''Theaetetus'' and ''Meno''. Indeed, the apprehension of Forms may be at the base of the account required for justification, in that it offers foundational knowledge which itself needs no account, thereby avoiding an infinite regression

An infinite regress is an infinite series of entities governed by a recursive principle that determines how each entity in the series depends on or is produced by its predecessor. In the epistemic regress, for example, a belief is justified bec ...

.

Justified true belief

Many have interpreted Plato as stating — even having been the first to write — that knowledge is justified true belief, an influential view that informed future developments in epistemology. This interpretation is partly based on a reading of the ''Theaetetus'' wherein Plato argues that knowledge is distinguished from mere true belief by the knower having an "account" of the object of their true belief. And this theory may again be seen in the ''Meno'', where it is suggested that true belief can be raised to the level of knowledge if it is bound with an account as to the question of "why" the object of the true belief is so.

Many years later,

Many have interpreted Plato as stating — even having been the first to write — that knowledge is justified true belief, an influential view that informed future developments in epistemology. This interpretation is partly based on a reading of the ''Theaetetus'' wherein Plato argues that knowledge is distinguished from mere true belief by the knower having an "account" of the object of their true belief. And this theory may again be seen in the ''Meno'', where it is suggested that true belief can be raised to the level of knowledge if it is bound with an account as to the question of "why" the object of the true belief is so.

Many years later, Edmund Gettier

Edmund Lee Gettier III (; October 31, 1927 – March 23, 2021) was an American philosopher at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is best known for his short 1963 article "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?", which has generated an exte ...

famously demonstrated the problems

A problem is a difficulty which may be resolved by problem solving.

Problem(s) or The Problem may also refer to:

People

* Problem (rapper), (born 1985) American rapper Books

* ''Problems'' (Aristotle), an Aristotelian (or pseudo-Aristotelian) c ...

of the justified true belief account of knowledge. That the modern theory of justified true belief as knowledge, which Gettier addresses, is equivalent to Plato's is accepted by some scholars but rejected by others. Plato himself also identified problems with the ''justified true belief'' definition in the ''Theaetetus'', concluding that justification (or an "account") would require knowledge of ''difference'', meaning that the definition of knowledge is circular

Circular may refer to:

* The shape of a circle

* ''Circular'' (album), a 2006 album by Spanish singer Vega

* Circular letter (disambiguation)

** Flyer (pamphlet), a form of advertisement

* Circular reasoning, a type of logical fallacy

* Circular ...

.

Ethics

Several dialogues discuss ethics including virtue and vice, pleasure and pain, crime and punishment, and justice and medicine. Plato views "The Good" as the supreme Form, somehow existing even "beyond being".

Socrates propounded a moral intellectualism which claimed nobody does bad on purpose, and to know what is good results in doing what is good; that knowledge is virtue. In the ''Protagoras'' dialogue it is argued that virtue is innate and cannot be learned.

Socrates presents the famous Euthyphro dilemma in the dialogue of the same name: "Is the pious ( τὸ ὅσιον) loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" ( 10a)

Justice

As above, in the ''Republic'', Plato asks the question, “What is justice?” By means of the Greek term ''dikaiosune'' – a term for “justice” that captures both individual justice and the justice that informs societies, Plato is able not only to inform metaphysics, but also ethics and politics with the question: “What is the basis of moral and social obligation?” Plato's well-known answer rests upon the fundamental responsibility to seek wisdom, wisdom which leads to an understanding of the Form of the Good. Plato further argues that such understanding of Forms produces and ensures the good communal life when ideally structured under a philosopher king in a society with three classes (philosopher kings, guardians, and workers) that neatly mirror his triadic view of the individual soul (reason, spirit, and appetite). In this manner, justice is obtained when knowledge of how to fulfill one's moral and political function in society is put into practice.

Politics

The dialogues also discuss politics. Some of Plato's most famous doctrines are contained in the ''Republic'' as well as in the ''

The dialogues also discuss politics. Some of Plato's most famous doctrines are contained in the ''Republic'' as well as in the ''Laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. ...

'' and the ''Statesman''. Because these opinions are not spoken directly by Plato and vary between dialogues, they cannot be straightforwardly assumed as representing Plato's own views.

Socrates asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul. The appetite/spirit/reason are analogous to the castes of society.

* ''Productive'' (Workers) – the labourers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

* ''Protective'' (Warriors or Guardians) – those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the "spirit" part of the soul.

* ''Governing'' (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) – those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the "reason" part of the soul and are very few.

According to this model, the principles of Athenian democracy (as it existed in his day) are rejected as only a few are fit to rule. Instead of rhetoric and persuasion, Socrates says reason and wisdom should govern. As Socrates puts it:

: "Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils,... nor, I think, will the human race."

Socrates describes these "philosopher kings" as "those who love the sight of truth" and supports the idea with the analogy of a captain and his ship or a doctor and his medicine. According to him, sailing and health are not things that everyone is qualified to practice by nature. A large part of the ''Republic'' then addresses how the educational system should be set up to produce these philosopher kings.

In addition, the ideal city is used as an image to illuminate the state of one's soul, or the will, reason, and desires combined in the human body. Socrates is attempting to make an image of a rightly ordered human, and then later goes on to describe the different kinds of humans that can be observed, from tyrants to lovers of money in various kinds of cities. The ideal city is not promoted, but only used to magnify the different kinds of individual humans and the state of their soul. However, the philosopher king image was used by many after Plato to justify their personal political beliefs. The philosophic soul according to Socrates has reason, will, and desires united in virtuous harmony. A philosopher has the moderate love for wisdom and the courage

Courage (also called bravery or valor) is the choice and willingness to confront agony, pain, danger, uncertainty, or intimidation. Valor is courage or bravery, especially in battle.

Physical courage is bravery in the face of physical pain, ...

to act according to wisdom. Wisdom is knowledge about the Good

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil and is of interest in the study of ethics, morality, ph ...

or the right relations between all that exists.

Wherein it concerns states and rulers, Socrates asks which is better—a bad democracy or a country reigned by a tyrant. He argues that it is better to be ruled by a bad tyrant, than by a bad democracy (since here all the people are now responsible for such actions, rather than one individual committing many bad deeds.) This is emphasised within the ''Republic'' as Socrates describes the event of mutiny on board a ship. Socrates suggests the ship's crew to be in line with the democratic rule of many and the captain, although inhibited through ailments, the tyrant. Socrates' description of this event is parallel to that of democracy within the state and the inherent problems that arise.

According to Socrates, a state made up of different kinds of souls will, overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy (rule by the honourable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to r ...

(rule by one person, rule by a tyrant). Aristocracy in the sense of government (politeia) is advocated in Plato's Republic. This regime is ruled by a philosopher king

The philosopher king is a hypothetical ruler in whom political skill is combined with philosophical knowledge. The concept of a city-state ruled by philosophers is first explored in Plato's ''Republic'', written around 375 BC. Plato argued that ...

, and thus is grounded on wisdom and reason.

The aristocratic state, and the man whose nature corresponds to it, are the objects of Plato's analyses throughout much of the ''Republic'', as opposed to the other four types of states/men, who are discussed later in his work. In Book VIII, Socrates states in order the other four imperfect societies with a description of the state's structure and individual character. In timocracy, the ruling class is made up primarily of those with a warrior-like character. Oligarchy is made up of a society in which wealth is the criterion of merit and the wealthy are in control. In democracy, the state bears resemblance to ancient Athens

Athens is one of the oldest named cities in the world, having been continuously inhabited for perhaps 5,000 years. Situated in southern Europe, Athens became the leading city of Ancient Greece in the first millennium BC, and its cultural achiev ...

with traits such as equality of political opportunity and freedom for the individual to do as he likes. Democracy then degenerates into tyranny from the conflict of rich and poor

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of we ...

. It is characterized by an undisciplined society existing in chaos, where the tyrant rises as a popular champion leading to the formation of his private army and the growth of oppression.

Art and poetry

Several dialogues tackle questions about art, including rhetoric and rhapsody. Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the ''Phaedrus'', and yet in the ''Republic'' wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well. In ''Ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conv ...

'', Socrates gives no hint of the disapproval of Homer that he expresses in the ''Republic''. The dialogue ''Ion'' suggests that Homer's '' Iliad'' functioned in the ancient Greek world as the Bible does today in the modern Christian world: as divinely inspired literature that can provide moral guidance, if only it can be properly interpreted.

Rhetoric

Scholars often view Plato's philosophy as at odds with rhetoric due to his criticisms of rhetoric in the '' Gorgias'' and his ambivalence toward rhetoric expressed in the '' Phaedrus''. But other contemporary researchers contest the idea that Plato despised rhetoric and instead view his dialogues as a dramatization of complex rhetorical principles.

Unwritten doctrines

For a long time,

For a long time, Plato's unwritten doctrines

Plato's so-called unwritten doctrines are metaphysical theories ascribed to him by his students and other ancient philosophers but not clearly formulated in his writings. In recent research, they are sometimes known as Plato's 'principle theory' ( ...

had been controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem to diminish its importance; nevertheless, the first important witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his '' Physics'' writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there .e. in ''Timaeus''of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called ''unwritten teachings'' ()." The term "" literally means ''unwritten doctrines'' or ''unwritten dogmas'' and it stands for the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have been seriously questioned before the 19th century.

A reason for not revealing it to everyone is partially discussed in ''Phaedrus'' where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as faulty, favouring instead the spoken ''logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Arist ...

'': "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful ... will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually." The same argument is repeated in Plato's ''Seventh Letter'': "every serious man in dealing with really serious subjects carefully avoids writing." In the same letter he writes: "I can certainly declare concerning all these writers who claim to know the subjects that I seriously study ... there does not exist, nor will there ever exist, any treatise of mine dealing therewith." Such secrecy is necessary in order not "to expose them to unseemly and degrading treatment".

It is, however, said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture ''On the Good'' (), in which the Good () is identified with the One (the Unity, ), the fundamental ontological principle. The content of this lecture has been transmitted by several witnesses. Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have bee ...

describes the event in the following words: "Each came expecting to learn something about the things that are generally considered good for men, such as wealth, good health, physical strength, and altogether a kind of wonderful happiness. But when the mathematical demonstrations came, including numbers, geometrical figures and astronomy, and finally the statement Good is One seemed to them, I imagine, utterly unexpected and strange; hence some belittled the matter, while others rejected it." Simplicius quotes Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Ἀφροδισιεύς, translit=Alexandros ho Aphrodisieus; AD) was a Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek commentators on the writings of Aristotl ...

, who states that "according to Plato, the first principles of everything, including the Forms themselves are One and Indefinite Duality (), which he called Large and Small ()", and Simplicius reports as well that "one might also learn this from Speusippus and Xenocrates and the others who were present at Plato's lecture on the Good".[see .]

Their account is in full agreement with Aristotle's description of Plato's metaphysical doctrine. In '' Metaphysics'' he writes: "Now since the Forms are the causes of everything else, he .e. Platosupposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Accordingly, the material principle is the Great and Small .e. the Dyad and the essence is the One (), since the numbers are derived from the Great and Small by participation in the One".[''Metaphysics'' 987b] "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence, and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in everything else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also tells us what the material substrate is of which the Forms are predicated in the case of sensible things, and the One in that of the Forms—that it is this the duality (the Dyad, ), the Great and Small (). Further, he assigned to these two elements respectively the causation of good and of evil".Plotinus

Plotinus (; grc-gre, Πλωτῖνος, ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a philosopher in the Hellenistic tradition, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher wa ...

or Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver o ...

which has been considered erroneous by many but may in fact have been directly influenced by oral transmission of Plato's doctrine. A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy

The World Congress of Philosophy (originally known as the International Congress of Philosophy) is a global meeting of philosophers held every five years under the auspices of the International Federation of Philosophical Societies (FISP). First or ...

in 1930. All the sources related to the have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as ''Testimonia Platonica''. These sources have subsequently been interpreted by scholars from the German ''Tübingen School of interpretation'' such as Hans Joachim Krämer or Thomas A. Szlezák.

Themes of Plato's dialogues

Trial of Socrates

The trial of Socrates and his death sentence is the central, unifying event of Plato's dialogues. It is relayed in the dialogues ''Apology'', ''

The trial of Socrates and his death sentence is the central, unifying event of Plato's dialogues. It is relayed in the dialogues ''Apology'', ''Crito

''Crito'' ( or ; grc, Κρίτων ) is a dialogue that was written by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It depicts a conversation between Socrates and his wealthy friend Crito of Alopece regarding justice (''δικαιοσύνη''), ...

'', and '' Phaedo''. ''Apology'' is Socrates' defence speech, and ''Crito'' and ''Phaedo'' take place in prison after the conviction.

''Apology'' is among the most frequently read of Plato's works. In the ''Apology'', Socrates tries to dismiss rumours that he is a sophist

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ...

and defends himself against charges of disbelief in the gods and corruption of the young. Socrates insists that long-standing slander will be the real cause of his demise, and says the legal charges are essentially false. Socrates famously denies being wise, and explains how his life as a philosopher was launched by the Oracle at Delphi

Pythia (; grc, Πυθία ) was the name of the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She specifically served as its oracle and was known as the Oracle of Delphi. Her title was also historically glossed in English as the Pythoness ...

. He says that his quest to resolve the riddle of the oracle put him at odds with his fellow man, and that this is the reason he has been mistaken for a menace to the city-state of Athens.