Piracy in the Caribbean on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

]The Piracy of the Caribbean refers to the historical period of widespread piracy that occurred in the

Pirates were often former sailors experienced in

Pirates were often former sailors experienced in  To combat this constant danger, in the 1560s the Spanish adopted a convoy system. A treasure fleet or ''flota'' would sail annually from Seville (and later from

To combat this constant danger, in the 1560s the Spanish adopted a convoy system. A treasure fleet or ''flota'' would sail annually from Seville (and later from

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

. Primarily between the 1650s and 1730s, where pirates frequently attacked and robbed merchant ships sailing through the region, often using bases or islands like Port Royal. The era of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

in the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

began in the 1500s and phased out in the 1830s after the navies of the nations of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

with colonies in the Caribbean began hunting and prosecuting pirates. The period during which pirates were most successful was from the 1650s to the 1730s. Piracy flourished in the Caribbean because of the existence of pirate seaports such as Fort Saint Louis in Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, KariĘĽn ...

, Port Royal

Port Royal () was a town located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest and most prosperous city in the Caribbean, functioning as the cen ...

in Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

,Campo-Flores/ Arian, "Yar, Mate! Swashbuckler Tours!," Newsweek 180, no. 6 (2002): 58. Castillo de la Real Fuerza in Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, Tortuga in Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

, and Nassau in the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of its population. ...

.Smith, Simon. "Piracy in early British America." ''History Today'' 46, no. 5 (May 1996): 29. Piracy in the Caribbean was part of a larger historical phenomenon of piracy, as it existed close to major trade and exploration routes in almost all the five oceans

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Antarctic/Southern, and ...

.

Causes

Pirates were often former sailors experienced in

Pirates were often former sailors experienced in naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river.

The Military, armed forces branch designated for naval warfare is a navy. Naval operations can be ...

. In the 16th century, pirate captains recruited seamen to loot European merchant ships

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

, especially the Spanish treasure fleets sailing from the Caribbean to Europe.

The following quote by an 18th-century Welsh captain shows the motivations for piracy:

—Pirate Captain Bartholomew Roberts

Piracy was sometimes given legal status by the colonial powers, especially France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

under King Francis I (r. 1515–1547), in the hope of weakening Spain and Portugal's ''mare clausum

''Mare clausum'' (legal Latin meaning "closed sea") is a term used in international law to mention a sea, ocean or other navigable body of water under the jurisdiction of a state that is closed or not accessible to other states. ''Mare clausum ...

'' trade monopolies in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. This officially sanctioned piracy was known as privateering

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since Piracy, robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sover ...

. From 1520 to 1560, French privateers were alone in their fight against the Crown of Spain and the vast commerce of the Spanish Empire in the New World. The French privateers were not considered pirates in France as they were in the service of the king of France, they were considered combatants and granted a lettre de marque or lettre de course which legitimized any actions they took under the French justice system. They were later joined by the English and Dutch. The English were dubbed " sea dogs".

The Caribbean had become an important center of European trade and colonization after Columbus' discovery of the New World for Spain in 1492. In the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494, and ratified in SetĂşbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian (geography) ...

the non-European world had been divided between the Spanish and the Portuguese along a north–south line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

. This gave Spain control of the Americas, a position the Spaniards later reiterated with an equally unenforceable papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

(The Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other orks) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, Queen Isabella I of ...

). On the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Spanish Main was the collective term used by English speakers for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of ...

, the key early settlements were Cartagena in present-day Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, Porto Bello and Panama City

Panama City, also known as Panama, is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has a total population of 1,086,990, with over 2,100,000 in its metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific Ocean, Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal, i ...

on the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

, Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile (), is the capital and largest city of Chile and one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is located in the country's central valley and is the center of the Santiago Metropolitan Regi ...

on the southeastern coast of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and Santo Domingo

Santo Domingo, formerly known as Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is the capital and largest city of the Dominican Republic and the List of metropolitan areas in the Caribbean, largest metropolitan area in the Caribbean by population. the Distrito Na ...

on the island of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

. In the 16th century, the Spanish were mining extremely large quantities of silver from the mines of Zacatecas

Zacatecas, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Zacatecas, is one of the Political divisions of Mexico, 31 states of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Zacatecas, 58 municipalities and its capital city is Zacatecas City, Zacatec ...

in New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

(Mexico) and PotosĂ

PotosĂ, known as Villa Imperial de PotosĂ in the colonial period, is the capital city and a municipality of the PotosĂ Department, Department of PotosĂ in Bolivia. It is one of the list of highest cities in the world, highest cities in the wo ...

in Bolivia (formerly known as Upper Peru). The huge Spanish silver shipments from the New World to the Old attracted pirates and French privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s like François Leclerc or Jean Fleury, both in the Caribbean and across the Atlantic, all along the route from the Caribbean to Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

.

To combat this constant danger, in the 1560s the Spanish adopted a convoy system. A treasure fleet or ''flota'' would sail annually from Seville (and later from

To combat this constant danger, in the 1560s the Spanish adopted a convoy system. A treasure fleet or ''flota'' would sail annually from Seville (and later from Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

) in Spain, carrying passengers, troops, and European manufactured goods to the Spanish colonies of the New World. This cargo, though profitable, was really just a form of ballast for the fleet as its true purpose was to transport the year's worth of silver to Europe. The first stage in the journey was the transport of all that silver from the mines in Bolivia and New Spain in a mule convoy called the Silver Train to a major Spanish port, usually on the Isthmus of Panama or Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

in New Spain. The ''flota'' would meet up with the Silver Train, offload its cargo of manufactured goods to waiting colonial merchants and then load its holds with the precious cargo of gold and silver, in bullion or coin form. This made the returning Spanish treasure fleet a tempting target, although pirates were more likely to shadow the fleet to attack stragglers than to engage the well-armed main vessels. The classic route for the treasure fleet in the Caribbean was through the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles is a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea, forming part of the West Indies in Caribbean, Caribbean region of the Americas. They are distinguished from the larger islands of the Greater Antilles to the west. They form an arc w ...

to the ports along the Spanish Main on the coast of Central America and New Spain, then northwards into the Yucatán Channel to catch the westerly winds back to Europe.

By the 1560s, the Dutch United Provinces of the Netherlands and England, both Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

states, were defiantly opposed to Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

Spain, the greatest power of Christendom

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

in the 16th century; while the French government was seeking to expand its colonial holdings in the New World now that Spain had proven they could be extremely profitable. It was the French who had established the first non-Spanish settlement in the Caribbean when they had founded Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June 1564, follow ...

near what is now Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

in 1564, although the settlement was soon wiped out by a Spanish attack from the larger colony of Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman province), Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced th ...

. As the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494, and ratified in SetĂşbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian (geography) ...

had proven unenforceable, a new concept of " lines of amity", with the northern bound being the Tropic of Cancer and the eastern bound the Prime Meridian passing through the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

, is said to have been verbally agreed upon by French and Spanish negotiators of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis. South and west of these lines, respectively, no protection could be offered to non-Spanish ships, "no peace beyond the line." English, Dutch and French pirates and settlers moved into this region even in times of nominal peace with the Spanish.

The Spanish, despite being the most powerful state in Christendom at the time, could not afford a sufficient military presence to control such a vast area of ocean or enforce their exclusionary, mercantilist trading laws. These laws allowed only Spanish merchants to trade with the colonists of the Spanish Empire in the Americas. This arrangement provoked constant smuggling against the Spanish trading laws and new attempts at Caribbean colonization in peacetime by England, France and the Netherlands. Whenever a war was declared in Europe between the Great Powers the result was always widespread piracy and privateering throughout the Caribbean.

The Anglo-Spanish War in 1585–1604 was partly due to trade disputes in the New World. A focus on extracting mineral and agricultural wealth from the New World rather than building productive, self-sustaining settlements in its colonies; inflation fueled in part by the massive shipments of silver and gold to Western Europe; endless rounds of expensive wars in Europe; an aristocracy that disdained commercial opportunities; and an inefficient system of tolls and tariffs that hampered industry all contributed to Spain's decline during the 17th century. However, very profitable trade continued between Spain's colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

, which continued to expand until the early 19th century.

Meanwhile, in the Caribbean, the arrival of European diseases with Columbus had reduced the local Native American populations; the native population of New Spain fell as much as 90% from its original numbers in the 16th century. This loss of native population led Spain to increasingly rely on African slave labor to run Spanish America's colonies, plantations and mines and the trans-Atlantic slave trade offered new sources of profit for the many English, Dutch and French traders who could violate the Spanish mercantilist laws with impunity. But the relative emptiness of the Caribbean also made it an inviting place for England, France and the Netherlands to set up colonies of their own, especially as gold and silver became less important as commodities to be seized and were replaced by tobacco and sugar as cash crops that could make men very rich.

As Spain's military might in Europe weakened, the Spanish trading laws in the New World were violated with greater frequency by the merchants of other nations. The Spanish port on the island of Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger, more populous island of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the country. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is the southernmost island in ...

off the northern coast of South America, permanently settled only in 1592, became a major point of contact between all the nations with a presence in the Caribbean.

History

Early seventeenth century, 1600–1660

Changes in demography

In the early 17th century, expensive fortifications and the size of the colonial garrisons at the major Spanish ports increased to deal with the enlarged presence of Spain's competitors in the Caribbean, but the treasure fleet's silver shipments and the number of Spanish-owned merchant ships operating in the region declined. Additional problems came from shortage of food supplies because of the lack of people to work farms. The number of European-born Spaniards in the New World or Spaniards of pure blood who had been born in New Spain, known as peninsulares and creoles, respectively, in the Spanishcaste system

A caste is a fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (endogamy), foll ...

, totaled no more than 250,000 people in 1600.

At the same time, England and France were powers on the rise in 17th-century Europe as they mastered their own internal religious schisms between Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

and Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and the resulting societal peace allowed their economies to rapidly expand. England especially began to turn its people's maritime skills into the basis of commercial prosperity. English and French kings of the early 17th century— James I (r. 1603–1625) and Henry IV (r. 1598–1610), respectively, each sought more peaceful relations with Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

in an attempt to decrease the financial costs of the ongoing wars. Although the onset of peace in 1604 reduced the opportunities for both piracy and privateering against Spain's colonies, neither monarch discouraged his nation from trying to plant new colonies in the New World and break the Spanish monopoly on the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

. The reputed riches, pleasant climate and the general emptiness of the Americas all beckoned to those eager to make their fortunes and a large assortment of Frenchmen and Englishmen began new colonial ventures during the early 17th century, both in North America, which lay basically empty of European settlement north of Mexico, and in the Caribbean, where Spain remained the dominant power until late in the century.

As for the Dutch Netherlands, after decades of rebellion against Spain fueled by both Dutch nationalism and their staunch Protestantism, independence had been gained in all but name (and that too would eventually come with the Treaty of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two Peace treaty, peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy R ...

in 1648). The Netherlands had become Europe's economic powerhouse. With new, innovative ship designs like the fluyt

A fluyt (archaic Dutch language, Dutch: ''fluijt'' "flute"; ) is a Dutch type of sailing ship, sailing vessel originally designed by the shipwrights of Hoorn as a dedicated ship transport, cargo vessel. Originating in the Dutch Republic in the 16 ...

(a cargo vessel able to be operated with a small crew and enter relatively inaccessible ports) rolling out of the ship yards in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

and Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , ; ; ) is the second-largest List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city in the Netherlands after the national capital of Amsterdam. It is in the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of South Holland, part of the North S ...

, new capitalist economic arrangements like the joint-stock company taking root and the military reprieve provided by the Twelve Year Truce with the Spanish (1609–1621), Dutch commercial interests were expanding explosively across the globe, but particularly in the New World and East Asia. However, in the early 17th century, the most powerful Dutch companies, like the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

, were most interested in developing operations in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

(Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

) and Japan, and left the West Indies to smaller, more independent Dutch operators.

=Spanish ports

= In the early 17th century, the Spanish colonies of Cartagena,Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Panamá Viejo, Porto Bello,

Many of the cities on the Spanish Main in the first third of the 17th century were self-sustaining but few had yet achieved any prosperity. The more backward settlements in Jamaica and Hispaniola were primarily places for ships to take on food and fresh water. Spanish Trinidad remained a popular smuggling port where European goods were plentiful and fairly cheap, and good prices were paid by its European merchants for tobacco.

The English colonies on Saint Kitts and Nevis, founded in 1623, would prove to become wealthy sugar-growing settlements in time. Another new English venture, the Providence Island colony on what is now Providencia Island in the

Many of the cities on the Spanish Main in the first third of the 17th century were self-sustaining but few had yet achieved any prosperity. The more backward settlements in Jamaica and Hispaniola were primarily places for ships to take on food and fresh water. Spanish Trinidad remained a popular smuggling port where European goods were plentiful and fairly cheap, and good prices were paid by its European merchants for tobacco.

The English colonies on Saint Kitts and Nevis, founded in 1623, would prove to become wealthy sugar-growing settlements in time. Another new English venture, the Providence Island colony on what is now Providencia Island in the

In the Caribbean, this political environment created many new threats for colonial governors. The sugar island of

In the Caribbean, this political environment created many new threats for colonial governors. The sugar island of

He was born about 1680 in England as Edward Thatch, Teach, or Drummond, and operated off the east coast of North America, particularly pirating in the Bahamas and had a base in North Carolina in the period of 1714–1718. Noted as much for his outlandish appearance as for his piratical success, in combat Blackbeard placed burning slow-match (a type of slow-burning fuse used to set off cannon) under his hat; with his face wreathed in fire and smoke, his victims claimed he resembled a fiendish apparition from

He was born about 1680 in England as Edward Thatch, Teach, or Drummond, and operated off the east coast of North America, particularly pirating in the Bahamas and had a base in North Carolina in the period of 1714–1718. Noted as much for his outlandish appearance as for his piratical success, in combat Blackbeard placed burning slow-match (a type of slow-burning fuse used to set off cannon) under his hat; with his face wreathed in fire and smoke, his victims claimed he resembled a fiendish apparition from

Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains t ...

, Santo Domingo

Santo Domingo, formerly known as Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is the capital and largest city of the Dominican Republic and the List of metropolitan areas in the Caribbean, largest metropolitan area in the Caribbean by population. the Distrito Na ...

, and San Juan San Juan, Spanish for Saint John (disambiguation), Saint John, most commonly refers to:

* San Juan, Puerto Rico

* San Juan, Argentina

* San Juan, Metro Manila, a highly urbanized city in the Philippines

San Juan may also refer to:

Places Arge ...

were among the most important settlements of the Spanish West Indies

The Spanish West Indies, Spanish Caribbean or the Spanish Antilles (also known as "Las Antillas Occidentales" or simply "Las Antillas Españolas" in Spanish) were Spanish territories in the Caribbean. In terms of governance of the Spanish Empir ...

. Each possessed a large population and a self-sustaining economy, and was well-protected by Spanish defenders. These Spanish settlements were generally unwilling to deal with traders from the other European states because of the strict enforcement of Spain's mercantilist laws pursued by the large Spanish garrisons. In these cities European manufactured goods could command premium prices for sale to the colonists, while the trade goods of the New World—tobacco, cocoa and other raw materials

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials/Intermediate goods that are feedstock for future finished ...

, were shipped back to Europe.

By 1600, Porto Bello had replaced Nombre de Dios (where Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

had first attacked a Spanish settlement) as the Isthmus of Panama's Caribbean port for the Spanish Silver Train and the annual treasure fleet. Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

, the only port city open to trans-Atlantic trade in New Spain, continued to serve the vast interior of New Spain as its window on the Caribbean. By the 17th century, the majority of the towns along the Spanish Main and in Central America had become self-sustaining. The smaller towns of the Main grew tobacco and also welcomed foreign smugglers who avoided the Spanish mercantilist laws. The underpopulated inland regions of Hispaniola and Venezuela were another area where tobacco smugglers in particular were welcome to ply their trade.

The Spanish-ruled island of Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger, more populous island of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the country. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is the southernmost island in ...

was already a wide-open port open to the ships and seamen of every nation in the region at the start of the 17th century, and was a particular favorite for smugglers who dealt in tobacco and European manufactured goods. Local Caribbean smugglers sold their tobacco or sugar for decent prices and then bought manufactured goods from the trans-Atlantic traders in large quantities to be dispersed among the colonists of the West Indies and the Spanish Main who were eager for a little touch of home. The Spanish governor of Trinidad, who both lacked strong harbor fortifications and possessed only a laughably small garrison of Spanish troops, could do little but take lucrative bribes from English, French and Dutch smugglers and look the other way—or risk being overthrown and replaced by his own people with a more pliable administrator.

=Other ports

= The English had established an early colony known asVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

in 1607 and one on the island of Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

in the West Indies in 1625, although this small settlement's people faced considerable dangers from the local Carib Indians (believed to be cannibals) for some time after its founding. The two early colonies needed regular imports from England, sometimes of food but primarily of woollen textiles. The main early exports back to England included sugar, tobacco, and tropical food. No large tobacco plantations or even truly organized defenses were established by the English on its Caribbean settlements at first and it would take time for England to realize just how valuable its possessions in the Caribbean could prove to be. Eventually, African slaves would be purchased through the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

. The first permanent French colony in the Caribbean was Saint-Pierre, established in 1635 on the island of Martinica by Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc after it was ceded from the Spanish. They would work the colonies and fuel Europe's tobacco, rice and sugar supply; by 1698 England had the largest slave exports with the most efficiency in their labor in relation to any other European imperial power. Barbados, the first truly successful English colony in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

, grew fast as the 17th century wore on and by 1698 Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

would be England's biggest colony to employ slave labor. The Spanish has ceded the western part of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

to France which named the colony of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

(present-day Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

). Increasingly, English ships chose to use it as their primary home port in the Caribbean. Like Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger, more populous island of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the country. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is the southernmost island in ...

, merchants in the trans-Atlantic trade who based themselves on Barbados always paid good money for tobacco and sugar. Both of these commodities remained the key cash crops of this period and fueled the growth of the American Southern Colonies as well as their counterparts in the Caribbean.

After the destruction of Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June 1564, follow ...

by the Spanish, the French made no further colonization attempts in the Caribbean for several decades as France was convulsed by its own Catholic-Protestant religious divide during the late 16th century Wars of Religion. However, old French privateering anchorages with small "tent camp" towns could be found during the early 17th century in the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of its population. ...

. These settlements provided little more than a place for ships and their crews to take on some fresh water and food and perhaps have a dalliance with the local camp followers, all of which would have been quite expensive.

From 1630 to 1654, Dutch merchants had a port in Brazil known as Recife

Recife ( , ) is the Federative units of Brazil, state capital of Pernambuco, Brazil, on the northeastern Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of South America. It is the largest urban area within both the North Region, Brazil, North and the Northeast R ...

. It was initially founded by the Portuguese in 1548. The Dutch had decided in 1630 to invade several sugar producing cities in Portuguese-controlled Brazil, including Salvador and Natal. From 1630 to 1654, they took control of Recife and Olinda

Olinda () is a historic city in Pernambuco, Brazil, in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region. It is located on the country's northeastern Atlantic Ocean coast, in the Recife metropolitan area, Metropolitan Region of Recife, the state ca ...

, making Recife the new capital of the territory of Dutch Brazil

Dutch Brazil (; ), also known as New Holland (), was a colony of the Dutch Republic in the northeastern portion of modern-day Brazil, controlled from 1630 to 1654 during Dutch colonization of the Americas. The main cities of the colony were the c ...

, renaming the city Mauritsstad. During this period, Mauritsstad became one of the most cosmopolitan cities of the world. Unlike the Portuguese, the Dutch did not prohibit Judaism. The first Jewish community and the first synagogue in the Americas—Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue

The Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue (; ; ) was a former Judaism, Jewish synagogue, located at 197 Rua do Bom Jesus (Rua dos Judeus), in the Recife Antigo, old city of Recife, in the state of Pernambuco, in northeastern Brazil.

The synagogue was esta ...

—was founded with the help of Moses Cohen Henriques in the city.

The Portuguese inhabitants fought on their own to expel the Dutch in 1654, being helped by the involvement of the Dutch in the First Anglo-Dutch War

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or First Dutch War, was a naval conflict between the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic. Largely caused by disputes over trade, it began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast ...

. The Dutch fought for nine years, only surrendering when safe passage for the Jews was guaranteed by the Portuguese. This was known as the Insurreição Pernambucana ( Pernambucan Insurrection). Most of the Jews fled to Amsterdam; others fled to North America, starting the first Jewish community of New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

(now known as New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

). The Dutch spent most of their time trading in smuggled goods with the smaller Spanish colonies. Trinidad was the unofficial home port for Dutch traders and privateers in the New World early in the 17th century before they established their own colonies in the region in the 1620s and 1630s. As usual, Trinidad's ineffective Spanish governor was helpless to stop the Dutch from using his port and instead he usually accepted their lucrative bribes.

European struggle

The first third of the 17th century in the Caribbean was defined by the outbreak of the savage and destructiveThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

in Europe (1618–1648), which represented both the culmination of the Protestant-Catholic conflict of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

and the final showdown between Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

Spain and Bourbon France. The war was mostly fought in Germany, where one-third to one-half of the population would eventually be lost to the strains of the conflict, but it had some effect in the New World as well. The Spanish presence in the Caribbean began to decline at a faster rate, becoming more dependent on African slave labor. The Spanish military presence in the New World also declined as Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

shifted more of its resources to the Old World in the Habsburgs' apocalyptic fight with almost every Protestant state in Europe. This need for Spanish resources in Europe accelerated the decay of the Spanish Empire in the Americas. The settlements of the Spanish Main and the Spanish West Indies became financially weaker and were garrisoned with a much smaller number of troops as their home countries were more consumed with happenings back in Europe. The Spanish Empire's economy remained stagnant and the Spanish colonies' plantations, ranches and mines became totally dependent upon slave labor imported from West Africa. With Spain no longer able to maintain its military control effectively over the Caribbean, the other Western European states finally began to move in and set up permanent settlements of their own, ending the Spanish monopoly over the control of the New World.

Even as the Dutch Netherlands was forced to renew its struggle against Spain for independence as part of the Thirty Years' War (the entire rebellion against the Spanish Habsburgs was called the Eighty Years War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exce ...

in the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

), the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

had become the world's leader in mercantile shipping and commercial capitalism, and Dutch companies finally turned their attention to the West Indies in the 17th century. The renewed war with Spain with the end of the truce offered many opportunities for the successful Dutch joint-stock companies to finance military expeditions against the Spanish Empire. The old English and French privateering anchorages from the 16th century in the Caribbean now swarmed anew with Dutch warships.

In England, a new round of colonial ventures in the New World was fueled by declining economic opportunities at home and growing religious intolerance for more radical Protestants (like the Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

) who rejected the compromise Protestant theology of the established Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. After the demise of the Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. Part of the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, it is located north/northeast of the island of Saint Vincent (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), Saint Vincent ...

and Grenada

Grenada is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The southernmost of the Windward Islands, Grenada is directly south of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and about north of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and the So ...

colonies soon after their establishment, and the near-extinction of the English settlement of Jamestown in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, new and stronger colonies were established by the English in the first half of the 17th century, at Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

, the West Indian islands of Saint Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially Saint Christopher, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis constitute one ...

and Nevis

Nevis ( ) is an island in the Caribbean Sea that forms part of the inner arc of the Leeward Islands chain of the West Indies. Nevis and the neighbouring island of Saint Kitts constitute the Saint Kitts and Nevis, Federation of Saint Kitts ...

and Providence Island. These colonies would all persevere to become centers of English civilization in the New World.

For France, now ruled by the Bourbon King Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

(r. 1610–1642) and his able minister Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu (9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), commonly known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic prelate and statesman who had an outsized influence in civil and religi ...

, religious civil war had been reignited between French Catholics and Protestants (called Huguenots). Throughout the 1620s, Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

fled France and founded colonies in the New World much like their English counterparts. Then, in 1636, to decrease the power of the Habsburg dynasty who ruled Spain and the Holy Roman Empire on France's eastern border, France entered the cataclysm in Germany—on the Protestants' side. The Franco-Spanish War continued until the 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees(; ; ) was signed on 7 November 1659 and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were conducted and the treaty was signed on Pheasant Island, situated in the middle of the Bidasoa River on ...

.

=Colonial disputes

= Many of the cities on the Spanish Main in the first third of the 17th century were self-sustaining but few had yet achieved any prosperity. The more backward settlements in Jamaica and Hispaniola were primarily places for ships to take on food and fresh water. Spanish Trinidad remained a popular smuggling port where European goods were plentiful and fairly cheap, and good prices were paid by its European merchants for tobacco.

The English colonies on Saint Kitts and Nevis, founded in 1623, would prove to become wealthy sugar-growing settlements in time. Another new English venture, the Providence Island colony on what is now Providencia Island in the

Many of the cities on the Spanish Main in the first third of the 17th century were self-sustaining but few had yet achieved any prosperity. The more backward settlements in Jamaica and Hispaniola were primarily places for ships to take on food and fresh water. Spanish Trinidad remained a popular smuggling port where European goods were plentiful and fairly cheap, and good prices were paid by its European merchants for tobacco.

The English colonies on Saint Kitts and Nevis, founded in 1623, would prove to become wealthy sugar-growing settlements in time. Another new English venture, the Providence Island colony on what is now Providencia Island in the Mosquito Coast

The Mosquito Coast, also known as Mosquitia, is a historical and Cultural area, geo-cultural region along the western shore of the Caribbean Sea in Central America, traditionally described as extending from Cabo CamarĂłn, Cape CamarĂłn to the C ...

of Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

, deep in the heart of the Spanish Empire, had become the premier base for English privateers and other pirates raiding the Spanish Main.

On the shared Anglo-French island of Saint Christophe (called "Saint Kitts" by the English) the French had the upper hand. The French settlers on Saint Christophe were mostly Catholics, while the unsanctioned but growing French colonial presence in northwest Hispaniola (the future nation of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

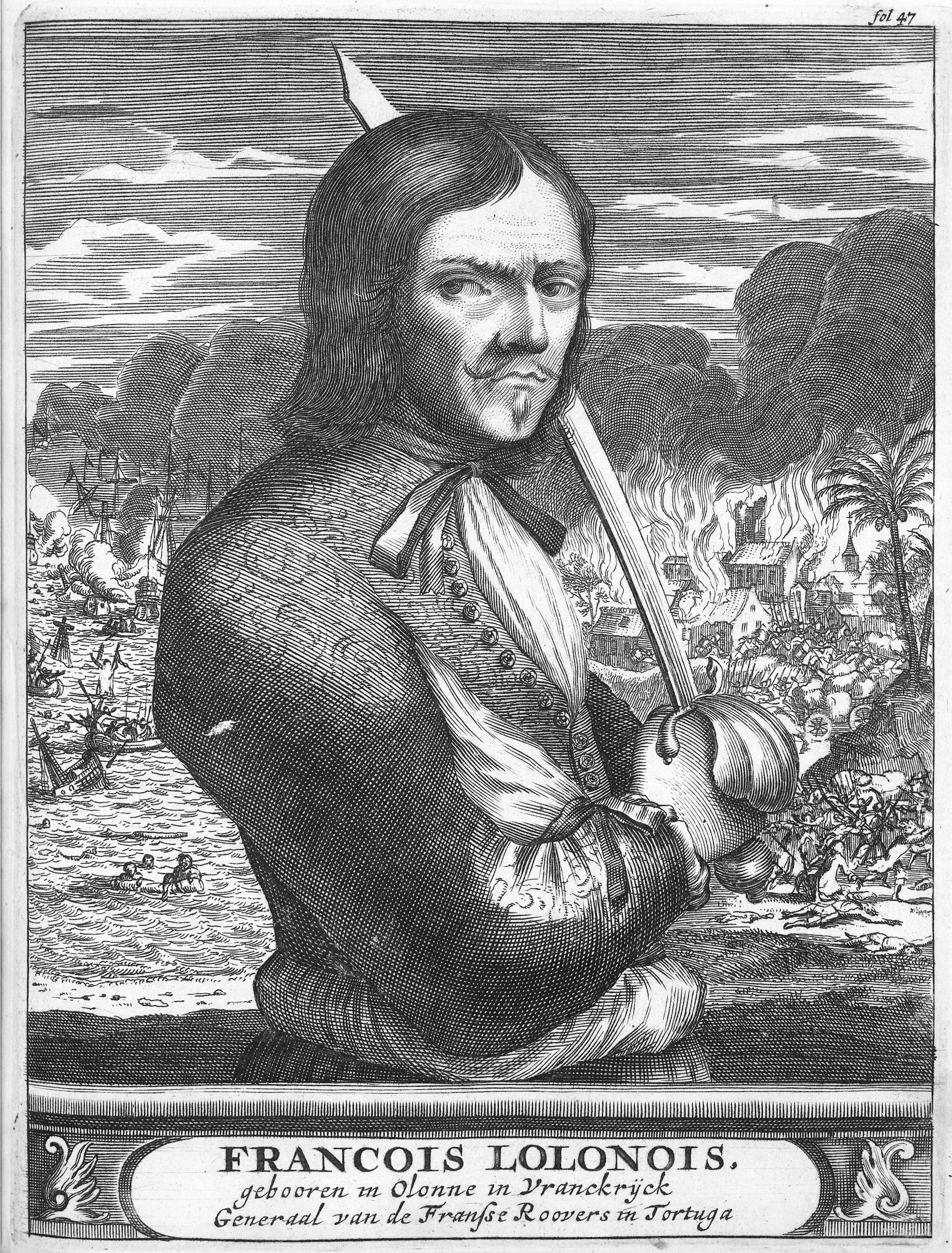

) was largely made up of French Protestants who had settled there without Spain's permission to escape Catholic persecution back home. France cared little what happened to the troublesome Huguenots, but the colonization of western Hispaniola allowed the French to both rid themselves of their religious minority and strike a blow against Spain—an excellent bargain, from the French Crown's point of view. The ambitious Huguenots had also claimed the island of Tortuga off the northwest coast of Hispaniola and had established the settlement of Petit-Goâve on the island itself. Tortuga in particular was to become a pirate and privateer haven and was beloved of smugglers of all nationalities—after all, even the creation of the settlement had been illegal.

Dutch colonies in the Caribbean remained rare until the second third of the 17th century. Along with the traditional privateering anchorages in the Bahamas and Florida, the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company () was a Dutch chartered company that was founded in 1621 and went defunct in 1792. Among its founders were Reynier Pauw, Willem Usselincx (1567–1647), and Jessé de Forest (1576–1624). On 3 June 1621, it was gra ...

settled a "factory" (commercial town) at New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

on the North American mainland in 1626 and at Curaçao

Curaçao, officially the Country of Curaçao, is a constituent island country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located in the southern Caribbean Sea (specifically the Dutch Caribbean region), about north of Venezuela.

Curaçao includ ...

in 1634, an island positioned right in the center of the Caribbean off the northern coast of Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

that was perfectly positioned to become a major maritime crossroads.

Seventeenth century crisis and colonial repercussions

The mid-17th century in the Caribbean was again shaped by events in far-off Europe. For the Dutch Netherlands, France, Spain and theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

being fought in Germany, the last great religious war in Europe, had degenerated into an outbreak of famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

, plague and starvation that managed to kill off one-third to one-half of the population of Germany. England, having avoided any entanglement in the European mainland's wars, had fallen victim to its own ruinous civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

that resulted in the short but brutal Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

military dictatorship (1649–1660) of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

and his Roundhead

Roundheads were the supporters of the Parliament of England during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I of England and his supporters, known as the Cavaliers or Royalists, who ...

armies. Of all the European Great Powers, Spain was in the worst shape economically and militarily as the Thirty Years' War concluded in 1648. Economic conditions had become so poor for the Spanish by the middle of the 17th century that a major rebellion began against the bankrupt and ineffective Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

government of King Philip IV (r. 1625–1665) that was eventually put down only with bloody reprisals by the Spanish Crown. This did not make Philip IV more popular.

But disasters in the Old World bred opportunities in the New World. The Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

's colonies were badly neglected from the middle of the 17th century because of Spain's many woes. Freebooters and privateers, experienced after decades of European warfare, pillaged and plundered the almost defenseless Spanish settlements with ease and with little interference from the European governments back home who were too worried about their own problems to turn much attention to their New World colonies. The non-Spanish colonies were growing and expanding across the Caribbean, fueled by a great increase in immigration as people fled from the chaos and lack of economic opportunity in Europe. While most of these new immigrants settled into the West Indies' expanding plantation economy, others took to the life of the buccaneer. Meanwhile, the Dutch, at last independent of Spain when the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia ended their own Eighty Years War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exce ...

(1568–1648) with the Habsburgs, made a fortune carrying the European trade goods needed by these new colonies. Peaceful trading was not as profitable as privateering, but it was a safer business.

By the later half of the 17th century, Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

had become the unofficial capital of the English West Indies before this position was claimed by Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

later in the century. Barbados was a merchant's dream port in this period. European goods were freely available, the island's sugar crop sold for premium prices, and the island's English governor rarely sought to enforce any type of mercantilist regulations. The English colonies at Saint Kitts and Nevis were economically strong and now well-populated as the demand for sugar in Europe increasingly drove their plantation-based economies. The English had also expanded their dominion in the Caribbean and settled several new islands, including Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

in 1612, Antigua

Antigua ( ; ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the local population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the most populous island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua ...

and Montserrat

Montserrat ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, wit ...

in 1632, and Eleuthera

Eleuthera () refers both to a single island in the archipelagic state of the The Bahamas, Commonwealth of the Bahamas and to its associated group of smaller islands. Eleuthera forms a part of the Great Bahama Bank. The island of Eleuthera incor ...

in the Bahamas in 1648, though these settlements began like all the others as relatively tiny communities that were not economically self-sufficient.

The French also founded major new colonies on the sugar-growing islands of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre Island, Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galant ...

in 1634 and Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, KariĘĽn ...

in 1635 in the Lesser Antilles. However, the heart of French activity in the Caribbean in the 17th century remained Tortuga, the fortified island haven off the coast of Hispaniola for privateers, buccaneers and outright pirates. The main French colony on the rest of Hispaniola remained the settlement of Petit-Goâve, which was the French toehold that would develop into the modern state of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

. French privateers still used the tent city anchorages in the Florida Keys to plunder the Spaniards' shipping in the Straits of Florida

The Straits of Florida, Florida Straits, or Florida Strait () is a strait located south-southeast of the North American mainland, generally accepted to be between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, and between the Florida Keys (U.S.) an ...

, as well as to raid the shipping that plied the sealanes off the northern coast of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

.

For the Dutch in the 17th century, the Caribbean island of Curaçao

Curaçao, officially the Country of Curaçao, is a constituent island country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located in the southern Caribbean Sea (specifically the Dutch Caribbean region), about north of Venezuela.

Curaçao includ ...

was the equivalent of England's port at Barbados. This large, rich, well-defended free port, open to the ships of all the European states, offered good prices for tobacco, sugar and cocoa that were re-exported to Europe and also sold large quantities of manufactured goods in return to the colonists of every nation in the New World. A second Dutch-controlled free port had also developed on the island of Sint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius, known locally as Statia, is an island in the Caribbean. It is a Caribbean Netherlands, special municipality (officially "Public body (Netherlands), public body") of the Netherlands.

The island is in the northern Leeward Islands ...

which was settled in 1636. The constant back-and-forth warfare between the Dutch and the English for possession of it in the 1660s later damaged the island's economy and desirability as a port. The Dutch also had set up a settlement on the island of Saint Martin which became another haven for Dutch sugar planters and their African slave labor. In 1648, the Dutch agreed to divide the prosperous island in half with the French.

Golden Age of Piracy, 1660–1726

The late 17th and early 18th centuries (particularly between the years 1706 to 1726) are often considered the "Golden Age of Piracy" in the Caribbean, and pirate ports experienced rapid growth in the areas in and surrounding the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Furthermore, during this time period there were approximately 2400 men that were currently active pirates. The military power of the Spanish Empire in the New World started to decline when KingPhilip IV of Spain

Philip IV (, ; 8 April 160517 September 1665), also called the Planet King (Spanish: ''Rey Planeta''), was King of Spain from 1621 to his death and (as Philip III) King of Portugal from 1621 to 1640. Philip is remembered for his patronage of the ...

was succeeded by King Charles II (r. 1665–1700), who in 1665 became the last Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

king of Spain at the age of four. While Spanish America in the late 17th century had little military protection as Spain entered a phase of decline as a great power, it also suffered less from the Spanish Crown's mercantilist policies with its economy. This lack of interference, combined with a surge in output from the silver mines due to increased availability of slave labor (the demand for sugar increased the number of slaves brought to the Caribbean) began a resurgence in the fortunes of Spanish America.

England, France and the Dutch Netherlands had all become New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

colonial powerhouses in their own right by 1660. Worried by the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

's intense commercial success since the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two Peace treaty, peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy R ...

, England launched a trade war with the Dutch. The English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised th ...

passed the first of its own mercantilist Navigation Acts

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce with other countries and with its own colonies. The laws al ...

(1651) and the Staple Act (1663) that required that English colonial goods be carried only in English ships and legislated limits on trade between the English colonies and foreigners. These laws were aimed at ruining the Dutch merchants whose livelihoods depended on free trade. This trade war would lead to three outright Anglo-Dutch Wars over the course of the next twenty-five years. Meanwhile, King Louis XIV of France (r. 1642–1715) had finally assumed his majority with the death of his regent mother Queen Anne of Austria's chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, in 1661. The "Sun King's" aggressive foreign policy was aimed at expanding France's eastern border with the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

and led to constant warfare (Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, 1672 to 1678, was primarily fought by Kingdom of France, France and the Dutch Republic, with both sides backed at different times by a variety of allies. Related conflicts include the 1672 to 1674 Third Anglo-Dutch War and ...

and Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

) against shifting alliances that included England, the Dutch Republic, the various German states and Spain. In short, Europe was consumed in the final decades of the 17th century by nearly constant dynastic intrigue and warfare—an opportune time for pirates and privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s to engage in their bloody trade.

Sint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius, known locally as Statia, is an island in the Caribbean. It is a Caribbean Netherlands, special municipality (officially "Public body (Netherlands), public body") of the Netherlands.

The island is in the northern Leeward Islands ...

changed ownership ten times between 1664 and 1674 as the English and Dutch dueled for supremacy there. Consumed with the various wars in Europe, the mother countries provided few military reinforcements to their colonies, so the governors of the Caribbean increasingly made use of buccaneer

Buccaneers were a kind of privateer or free sailors, and pirates particular to the Caribbean Sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. First established on northern Hispaniola as early as 1625, their heyday was from the Restoration in 1660 u ...

s as mercenaries and privateers to protect their territories or carry the fight to their country's enemies. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these undisciplined and greedy dogs of war often proved difficult for their sponsors to control.

By the late 17th century, the great Spanish towns of the Caribbean had begun to prosper and Spain also began to make a slow, fitful recovery, but remained poorly defended militarily because of Spain's problems and so were sometimes easy prey for pirates and privateers. The English presence continued to expand in the Caribbean as England itself was rising toward great power status in Europe. Captured from Spain in 1655, the island of Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

had been taken over by England and its chief settlement of Port Royal

Port Royal () was a town located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest and most prosperous city in the Caribbean, functioning as the cen ...

had become a new English buccaneer haven in the midst of the Spanish Empire. Jamaica was slowly transformed, along with Saint Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially Saint Christopher, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis constitute one ...

, into the heart of the English presence in the Caribbean. At the same time the French Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles is a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea, forming part of the West Indies in Caribbean, Caribbean region of the Americas. They are distinguished from the larger islands of the Greater Antilles to the west. They form an arc w ...

colonies of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre Island, Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galant ...

and Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, KariĘĽn ...

remained the main centers of French power in the Caribbean, as well as among the richest French possessions because of their increasingly profitable sugar plantations. The French also maintained privateering strongholds around western Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

, at their traditional pirate port of Tortuga, and their Hispaniolan capital of Petit-Goâve. The French further expanded their settlements on the western half of Hispaniola and founded Léogâne

Léogâne (; ) is one of the coastal communes in Haiti. It is located in the eponymous Léogâne Arrondissement, which is part of the Ouest Department. The port town is located about west of the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. Léogâne has ...

and Port-de-Paix

Port-de-Paix (; or ; meaning "Port of Peace") is a List of communes of Haiti, commune and the capital of the Nord-Ouest (department), Nord-Ouest Departments of Haiti, department of Haiti on the Atlantic coast. It has a population of 462,000 (201 ...

, even as sugar plantations became the primary industry for the French colonies of the Caribbean.

At the start of the 18th century, Europe remained riven by warfare and constant diplomatic intrigue. France was still the dominant power but now had to contend with a new rival, England (Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

after 1707) which emerged as a great power at sea and land during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

. But the depredations of the pirates and buccaneers in the Americas in the latter half of the 17th century and of similar mercenaries in Germany during the Thirty Years' War