Philip Melanchthon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German

Opposed as a reformer at Tübingen, he accepted a call to the University of Wittenberg from

Opposed as a reformer at Tübingen, he accepted a call to the University of Wittenberg from

In the beginning of 1521, Melanchthon defended Luther in his ''Didymi Faventini versus Thomam Placentinum pro M. Luthero oratio'' (Wittenberg, n.d.). He argued that Luther rejected only papal and ecclesiastical practises which were at variance with Scripture. But while Luther was absent at

In the beginning of 1521, Melanchthon defended Luther in his ''Didymi Faventini versus Thomam Placentinum pro M. Luthero oratio'' (Wittenberg, n.d.). He argued that Luther rejected only papal and ecclesiastical practises which were at variance with Scripture. But while Luther was absent at

The composition now known as the '' Augsburg Confession'' was laid before the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, and would come to be considered perhaps the most significant document of the

The composition now known as the '' Augsburg Confession'' was laid before the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, and would come to be considered perhaps the most significant document of the

In his controversy on justification with

In his controversy on justification with

On the other hand, Luther wrote of Melanchthon, in the preface to Melanchthon's '' Kolosserkommentar'' (1529), "I had to fight with rabble and devils, for which reason my books are very warlike. I am the rough pioneer who must break the road; but Master Philip comes along softly and gently, sows and waters heartily, since God has richly endowed him with gifts." Luther also did justice to Melanchthon's teachings, praising one year before his death in the preface to his own writings Melanchthon's revised ''Loci'' above them and calling Melanchthon "a divine instrument which has achieved the very best in the department of theology to the great rage of the devil and his scabby tribe." It is remarkable that Luther, who vehemently attacked men like Erasmus and Bucer, when he thought that truth was at stake, never spoke directly against Melanchthon, and even during his melancholy last years conquered his temper.

The strained relation between these two men never came from external things, such as human rank and fame, much less from other advantages, but always from matters of church and doctrine, and chiefly from the fundamental difference of their individualities; they repelled and attracted each other "because nature had not formed out of them one man." It cannot be denied, however, that Luther was the more magnanimous, for however much he was at times dissatisfied with Melanchthon's actions, he never uttered a word against his private character; however Melanchthon sometimes evinced a lack of confidence in Luther. In a letter to Carlowitz, before the Diet of Augsburg, he protested that Luther on account of his hot-headed nature exercised a personally humiliating pressure upon him.

On the other hand, Luther wrote of Melanchthon, in the preface to Melanchthon's '' Kolosserkommentar'' (1529), "I had to fight with rabble and devils, for which reason my books are very warlike. I am the rough pioneer who must break the road; but Master Philip comes along softly and gently, sows and waters heartily, since God has richly endowed him with gifts." Luther also did justice to Melanchthon's teachings, praising one year before his death in the preface to his own writings Melanchthon's revised ''Loci'' above them and calling Melanchthon "a divine instrument which has achieved the very best in the department of theology to the great rage of the devil and his scabby tribe." It is remarkable that Luther, who vehemently attacked men like Erasmus and Bucer, when he thought that truth was at stake, never spoke directly against Melanchthon, and even during his melancholy last years conquered his temper.

The strained relation between these two men never came from external things, such as human rank and fame, much less from other advantages, but always from matters of church and doctrine, and chiefly from the fundamental difference of their individualities; they repelled and attracted each other "because nature had not formed out of them one man." It cannot be denied, however, that Luther was the more magnanimous, for however much he was at times dissatisfied with Melanchthon's actions, he never uttered a word against his private character; however Melanchthon sometimes evinced a lack of confidence in Luther. In a letter to Carlowitz, before the Diet of Augsburg, he protested that Luther on account of his hot-headed nature exercised a personally humiliating pressure upon him.

Another trait of his character was his love of peace. He had an innate aversion to quarrels and discord; yet, often he was very irritable. His irenical character often led him to adapt himself to the views of others, as may be seen from his correspondence with Erasmus and from his public attitude from the Diet of Augsburg to the Interim. It was said not to be merely a personal desire for peace, but his conservative religious nature that guided him in his acts of conciliation. He never could forget that his father on his death-bed had besought his family "never to leave the church." He stood toward the history of the church in an attitude of piety and reverence that made it much more difficult for him than for Luther to be content with the thought of the impossibility of a reconciliation with the Catholic Church. He laid stress upon the authority of the Fathers, not only of

Another trait of his character was his love of peace. He had an innate aversion to quarrels and discord; yet, often he was very irritable. His irenical character often led him to adapt himself to the views of others, as may be seen from his correspondence with Erasmus and from his public attitude from the Diet of Augsburg to the Interim. It was said not to be merely a personal desire for peace, but his conservative religious nature that guided him in his acts of conciliation. He never could forget that his father on his death-bed had besought his family "never to leave the church." He stood toward the history of the church in an attitude of piety and reverence that made it much more difficult for him than for Luther to be content with the thought of the impossibility of a reconciliation with the Catholic Church. He laid stress upon the authority of the Fathers, not only of

As a scholar Melanchthon embodied the entire spiritual culture of his age. At the same time he found the simplest, clearest, and most suitable form for his knowledge; therefore his manuals, even if they were not always original, were quickly introduced into schools and kept their place for more than a century. Knowledge had for him no purpose of its own; it existed only for the service of moral and religious education, and so the teacher of Germany prepared the way for the religious thoughts of the Reformation. He was, alongside other luminaries such as Erasmus, an important figure in the movement sometimes called

As a scholar Melanchthon embodied the entire spiritual culture of his age. At the same time he found the simplest, clearest, and most suitable form for his knowledge; therefore his manuals, even if they were not always original, were quickly introduced into schools and kept their place for more than a century. Knowledge had for him no purpose of its own; it existed only for the service of moral and religious education, and so the teacher of Germany prepared the way for the religious thoughts of the Reformation. He was, alongside other luminaries such as Erasmus, an important figure in the movement sometimes called

In the sphere of historical theology the influence of Melanchthon may be traced until the seventeenth century, especially in the method of treating

In the sphere of historical theology the influence of Melanchthon may be traced until the seventeenth century, especially in the method of treating

As a philologist and pedagogue Melanchthon was the spiritual heir of the South German Humanists, of men like

As a philologist and pedagogue Melanchthon was the spiritual heir of the South German Humanists, of men like

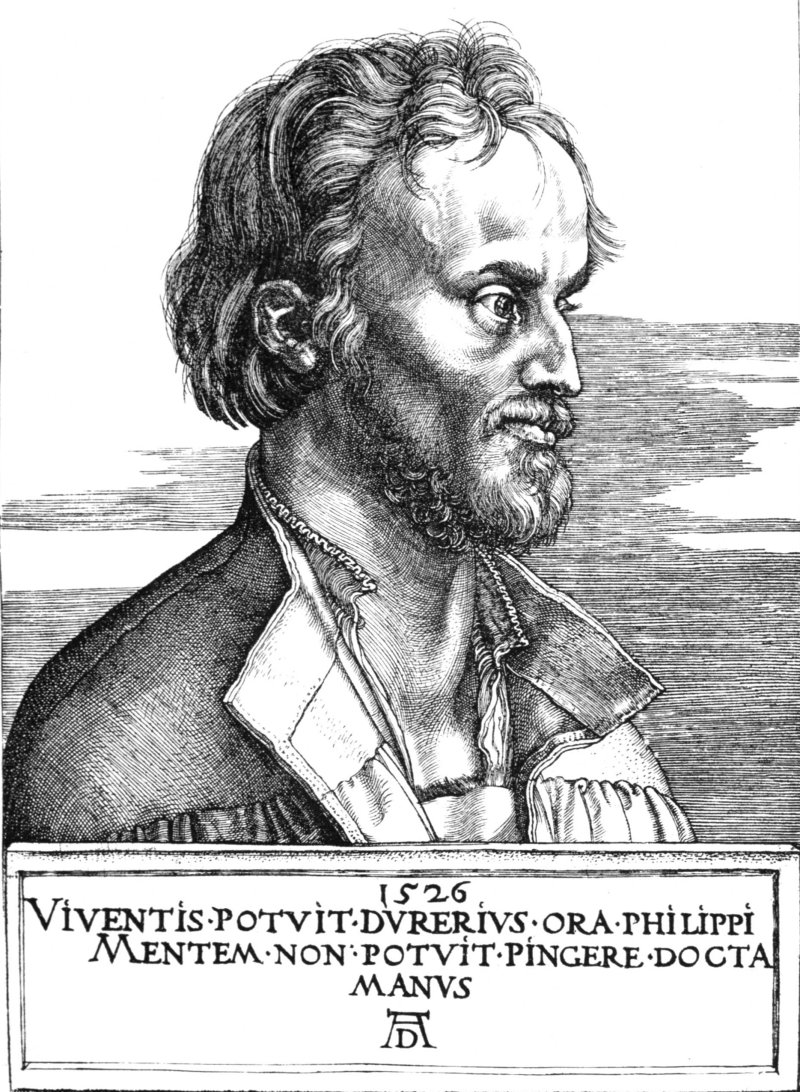

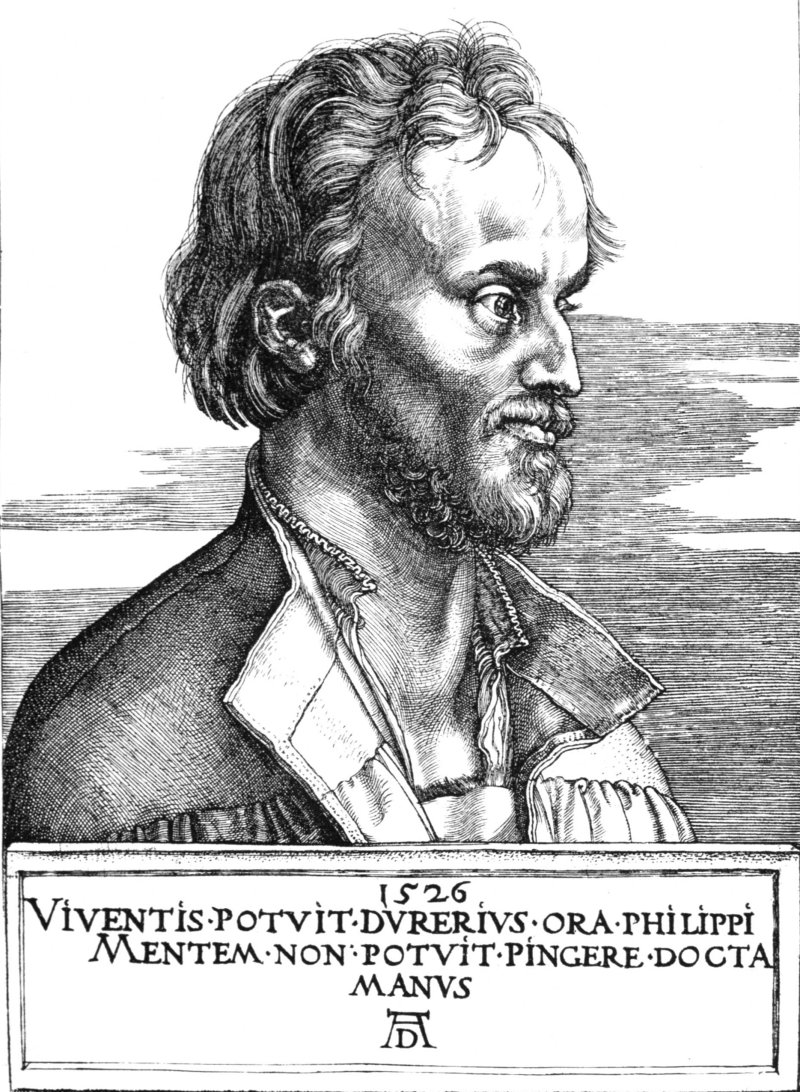

There have been preserved original portraits of Melanchthon by three famous painters of his time – by Hans Holbein the Younger one of them in the Royal Gallery of

There have been preserved original portraits of Melanchthon by three famous painters of his time – by Hans Holbein the Younger one of them in the Royal Gallery of

This article incorporates material from this public-domain publication. * * * * * * * * * * *

This article incorporates material from this public-domain publication.

Works

a

Open Library

* *

Examen eorum, qui oudiuntur ante ritum publicae ordinotionis, qua commendatur eis ministerium Evangelli: Traditum Vuitebergae, Anno 1554

at Opolska Biblioteka Cyfrowa {{DEFAULTSORT:Melanchthon, Philipp 1497 births 1560 deaths 16th-century German Protestant theologians 16th-century male writers 16th-century Latin-language writers Burials at All Saints' Church, Wittenberg Critics of the Catholic Church German astrologers 16th-century astrologers 16th-century German astronomers 16th-century German Lutheran clergy German Lutheran theologians German male non-fiction writers German Protestant Reformers German Renaissance humanists German evangelicals Heidelberg University alumni Lay theologians Lutheran biblical scholars Lutheran sermon writers People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar People from Bretten People from the Margraviate of Baden Systematic theologians Translators of the Bible into German University of Wittenberg faculty 16th-century Lutheran theologians Lutheran saints

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, the first systematic theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems. He stands next to Luther and John Calvin as a reformer, theologian, and shaper of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

.

Melanchthon and Luther denounced what they believed was the exaggerated cult of the saints, asserted justification by faith

''Justificatio sola fide'' (or simply ''sola fide''), meaning justification by faith alone, is a soteriological doctrine in Christian theology commonly held to distinguish the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, among others, fr ...

, and denounced what they considered to be the coercion of the conscience in the sacrament of penance (confession and absolution), which they believed could not offer certainty of salvation. Both rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation, i.e. that the bread and wine of the eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

are converted by the Holy Spirit into the flesh and blood of Christ; however, they affirmed that Christ's body and blood are present with the elements of bread and wine in the sacrament of the Lord's Supper. This Lutheran view of sacramental union contrasts with the understanding of the Catholic Church that the bread and wine cease to be bread and wine at their consecration (while retaining the appearances of both). Melanchthon made his distinction between law and gospel the central formula for Lutheran evangelical insight. By the "law", he meant God's requirements both in Old and New Testament; the "gospel" meant the free gift of grace through faith in Jesus Christ.

Early life and education

He was born Philipp Schwartzerdt on 16 February 1497, at Bretten, where his father Georg Schwarzerdt (1459–1508) was armorer to Philip, Count Palatine of the Rhine. His mother was Barbara Reuter (1476/77–1529). His birthplace, along with almost the whole city of Bretten, was burned in 1689 by French troops during the War of the Palatinate Succession. The town's Melanchthonhaus was built on its site in 1897. In 1507 he was sent to the Latin school atPforzheim

Pforzheim () is a city of over 125,000 inhabitants in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, in the southwest of Germany.

It is known for its jewelry and watch-making industry, and as such has gained the nickname "Goldstadt" ("Golden City") ...

, where the rector, Georg Simler of Wimpfen, introduced him to the Latin and Greek poets and to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

. He was influenced by his great-uncle Johann Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin (; sometimes called Johannes; 29 January 1455 – 30 June 1522) was a German Catholic humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew, whose work also took him to modern-day Austria, Switzerland, and Italy and France. Most of Reuchlin' ...

, a Renaissance humanist

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

; it was Reuchlin who suggested Philipp follow a custom common among humanists of the time and change his surname from "Schwartzerdt" (literally 'black earth'), into the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

equivalent "Melanchthon" (Μελάγχθων).

Philipp was only eleven when in 1508 both his grandfather (17 October) and father (27 October) died within eleven days. He and a brother were brought to Pforzheim

Pforzheim () is a city of over 125,000 inhabitants in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, in the southwest of Germany.

It is known for its jewelry and watch-making industry, and as such has gained the nickname "Goldstadt" ("Golden City") ...

to live with his maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Reuter, sister of Reuchlin.

The next year he entered the University of Heidelberg, where he studied philosophy, rhetoric, and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

/astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

, and became known as a scholar of Greek. Denied the master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

in 1512 on the grounds of his youth, he went to Tübingen

Tübingen (, , Swabian: ''Dibenga'') is a traditional university city in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, and developed on both sides of the Neckar and Ammer rivers. about one in three ...

, where he continued humanistic studies but also worked on jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, mathematics, and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

. While there he was also taught the technical aspects of astrology by Johannes Stöffler.

After gaining a master's degree in 1516, he began to study theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

. Under the influence of Reuchlin, Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

, and others, he became convinced that true Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

was something different from the scholastic theology as taught at the university. He became a ''conventor'' (repentant) in the ''contubernium

A ''contubernium'' was a quasi-marital relationship in ancient Rome between a free citizen and a slave or between two slaves. A slave involved in such relationship was called ''contubernalis''.

The term describes a wide range of situations, from ...

'' and instructed younger scholars. He also lectured on oratory, on Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

and on Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

.

His first publications were a number of poems in a collection edited by Jakob Wimpfeling (), the preface to Reuchlin's ''Epistolae clarorum virorum'' (1514), an edition of Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

(1516), and a Greek grammar (1518).

Professor at Wittenberg

Opposed as a reformer at Tübingen, he accepted a call to the University of Wittenberg from

Opposed as a reformer at Tübingen, he accepted a call to the University of Wittenberg from Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

on the recommendation of his great-uncle, and became professor of Greek there at the age of 21. He studied the Scriptures

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

, especially of Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

, and Evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

doctrine. Attending the disputation of Leipzig (1519) as a spectator, he nonetheless participated with his comments. After his views were attacked by Johann Eck, Melanchthon replied based on the authority of Scripture in his ''Defensio contra Johannem Eckium'' (Wittenberg, 1519).

Following lectures on the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and form ...

and the Epistle to the Romans, together with his investigations into Pauline doctrine, he was granted the degree of bachelor of theology

The Bachelor of Theology degree (BTh, ThB, or BTheol) is a three- to five-year undergraduate degree in theological disciplines and is typically pursued by those seeking ordination for ministry in a church, denomination, or parachurch organization. ...

, and transferred to the theological faculty. He married Katharina Krapp ( Katharina article from the German Wikipedia), (1497–1557) daughter of Wittenberg's mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

, on 25 November 1520. They had four children: Anna ( Anna article from the German Wikipedia), Philipp, Georg, and Magdalen.

Theological disputes

In the beginning of 1521, Melanchthon defended Luther in his ''Didymi Faventini versus Thomam Placentinum pro M. Luthero oratio'' (Wittenberg, n.d.). He argued that Luther rejected only papal and ecclesiastical practises which were at variance with Scripture. But while Luther was absent at

In the beginning of 1521, Melanchthon defended Luther in his ''Didymi Faventini versus Thomam Placentinum pro M. Luthero oratio'' (Wittenberg, n.d.). He argued that Luther rejected only papal and ecclesiastical practises which were at variance with Scripture. But while Luther was absent at Wartburg Castle

The Wartburg () is a castle originally built in the Middle Ages. It is situated on a precipice of to the southwest of and overlooking the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It was the home of St. Elisabeth of Hungary, the ...

, during the disturbances caused by the Zwickau prophets, Melanchthon wavered.

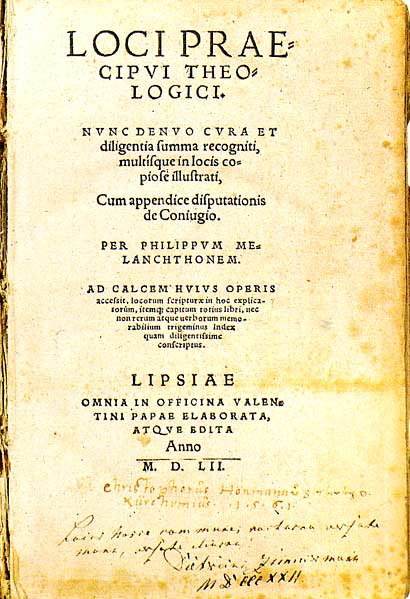

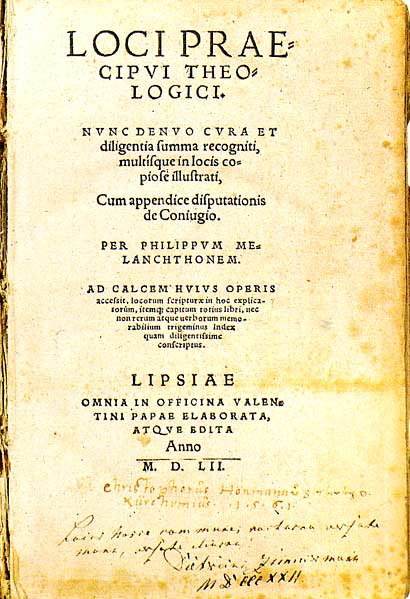

The appearance of Melanchthon's '' Loci communes rerum theologicarum seu hypotyposes theologicae'' (Wittenberg and Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, 1521) was of subsequent importance to the Reformation. Melanchthon presented a new doctrine of Christianity under the form of a discussion of the "leading thoughts" of the Epistle to the Romans. ''Loci communes'' contributed to the gradual rise of the Lutheran scholastic tradition, and the later theologians Martin Chemnitz, Mathias Haffenreffer

Matthias Hafenreffer (24 June 1561 22 October 1619) was a German orthodox Lutheran theologian in the Lutheran scholastic tradition.

Born at Lorch (Württemberg), Hafenreffer was professor at Tübingen from 1592 until his death in 1617. He was ...

, and Leonhard Hutter

Leonhard Hutter (also ''Hütter'', Latinized as Hutterus; 19 January 1563 – 23 October 1616) was a German Lutheran theologian.

Life

He was born at Nellingen near Ulm. From 1581 he studied at the universities of Strasbourg, Leipzig, Heidelberg ...

expanded upon it. Melanchthon continued to lecture on the classics.

On a journey in 1524 to his native town, he encountered the papal legate, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Lorenzo Campeggio (7 November 1474 – 19 July 1539) was an Italian cardinal and politician. He was the last cardinal protector of England.

Life

Campeggio was born in Milan, the eldest of five sons. In 1500, he took his doctorate in can ...

, who tried to draw him from Luther's cause. In his ''Unterricht der Visitatorn an die Pfarherrn im Kurfürstentum zu Sachssen'' (1528) Melanchthon presented the evangelical doctrine of salvation as well as regulations for churches and schools.

In 1529, Melanchthon accompanied the elector

Elector may refer to:

* Prince-elector or elector, a member of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Holy Roman Emperors

* Elector, a member of an electoral college

** Confederate elector, a member of ...

to the Diet of Speyer. His hopes of persuading the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

to recognize the Reformation were not fulfilled. A friendly attitude towards the Swiss at the Diet was something he later changed, calling Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

's doctrine of the Lord's Supper "an impious dogma".

Augsburg Confession

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

. While the confession was based on Luther's Marburg and Schwabach

Schwabach () is a German city of about 40,000 inhabitants near Nuremberg in the centre of the region of Franconia in the north of Bavaria. The city is an autonomous administrative district (''kreisfreie Stadt''). Schwabach is also the name of th ...

articles, it was mainly the work of Melanchthon; although it was commonly thought of as a unified statement of doctrine by the two reformers, Luther did not conceal his dissatisfaction with its irenic tone. Indeed, some would criticize Melanchthon's conduct at the Diet as unbecoming of the principle he promoted, implying that faith in the truth of his cause should logically have inspired Melanchthon to a firmer and more dignified posture. Others point out that he had not sought the part of a political leader, suggesting that he seemed to lack the requisite energy and decision for such a role and may simply have been a lackluster judge of human nature.

Melanchthon then settled into the comparative quiet of his academic and literary labours. His most important theological work of this period was the ''Commentarii in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos'' (Wittenberg, 1532), noteworthy for introducing the idea that "to be justified" means "to be accounted just", whereas the Apology had placed side by side the meanings of "to be made just" and "to be accounted just". Melanchthon's increasing fame gave occasion for prestigious invitations to Tübingen (September 1534), France, and England but consideration of the elector caused him to refuse them.

Discussions on Lord's Supper and justification

Melanchthon played an important role in discussions concerning the Lord's Supper which began in 1531. He approved fully of theWittenberg Concord Wittenberg Concord, is a religious concordat signed by Reformed and Lutheran theologians and churchmen on 29 May 1536 as an attempted resolution of their differences with respect to the Real Presence of Christ's body and blood in the Eucharist. It ...

sent by Bucer to Wittenberg, and at the instigation of the Landgrave of Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Dar ...

discussed the question with Bucer in Kassel, at the end of 1534. He eagerly laboured for an agreement on this question, for his patristic studies and the Dialogue (1530) of Johannes Oecolampadius had made him doubt the correctness of Luther's doctrine. Moreover, after the death of Zwingli and the change of the political situation his earlier scruples in regard to a union lost their weight. Bucer did not go so far as to believe with Luther that the true body of Christ in the Lord's Supper is bitten by the teeth, but admitted the offering of the body and blood in the symbols of bread and wine. Melanchthon discussed Bucer's views with the most prominent adherents of Luther; but Luther himself would not agree to a mere veiling of the dispute. Melanchthon's relation to Luther was not disturbed by his work as a mediator, although Luther for a time suspected that Melanchthon was "almost of the opinion of Zwingli" nevertheless he desired to "share his heart with him".

During his sojourn in Tübingen in 1536 Melanchthon was heavily criticised by Cordatus, preacher

A preacher is a person who delivers sermons or homilies on religious topics to an assembly of people. Less common are preachers who preach on the street, or those whose message is not necessarily religious, but who preach components such as ...

in Niemeck, because he had taught that works are necessary for salvation. In the second edition of his ''Loci'' (1535), he abandoned his earlier strict doctrine of determinism which went even beyond that of Augustine of Hippo and in its place taught more clearly his so-called Synergism. He repudiated the criticism of Cordatus in a letter to Luther and his other colleagues stating that he had never departed from their common teachings on this subject and in the Antinomian Controversy of 1537 Melanchthon was in harmony with Luther.

Controversies with Flacius

The final period of Melanchthon's life began with controversies over the Interims and theAdiaphora

Adiaphoron (; plural: adiaphora; from the Greek (pl. ), meaning "not different or differentiable") is the negation of ''diaphora'', "difference".

In Cynicism, adiaphora represents indifference to the s of life. In Pyrrhonism, it indicates thin ...

(1547). He rejected the Augsburg Interim

The Augsburg Interim (full formal title: ''Declaration of His Roman Imperial Majesty on the Observance of Religion Within the Holy Empire Until the Decision of the General Council'') was an imperial decree ordered on 15 May 1548 at the 1548 Diet ...

, which the emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

sought to force upon the defeated Protestants. During negotiations concerning the Leipzig Interim

The Leipzig Interim was one of several temporary settlements between the Emperor Charles V and German Lutherans following the Schmalkaldic War. It was presented to an assembly of Saxon political estates in December 1548. Though not adopted by the a ...

he made controversial concessions. In agreeing to various Catholic usages, Melanchthon held the opinion that they are adiaphora

Adiaphoron (; plural: adiaphora; from the Greek (pl. ), meaning "not different or differentiable") is the negation of ''diaphora'', "difference".

In Cynicism, adiaphora represents indifference to the s of life. In Pyrrhonism, it indicates thin ...

, if nothing is changed in the pure doctrine and the sacraments which Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

instituted. However he disregarded the position that concessions made under such circumstances have to be regarded as a denial of Evangelical convictions.

Melanchthon himself regretted his actions.

After Luther's death he became seen by many as the "theological leader of the German Reformation" although the Gnesio-Lutherans with Matthias Flacius

Matthias Flacius Illyricus (Latin; hr, Matija Vlačić Ilirik) or Francovich ( hr, Franković) (3 March 1520 – 11 March 1575) was a Lutheran reformer from Istria, present-day Croatia. He was notable as a theologian, sometimes dissenting strong ...

at their head accused him and his followers of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

and apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

. Melanchthon bore all accusations with patience, dignity, and self-control.

Disputes with Osiander and Stancaro

In his controversy on justification with

In his controversy on justification with Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander (; 19 December 1498 – 17 October 1552) was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

Career

Born at Gunzenhausen, Ansbach, in the region of Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before ...

Melanchthon satisfied all parties. He took part also in a controversy with Stancaro, who held that Christ was our justification only according to his human nature.

He was also still a strong opponent of the Catholics, for it was by his advice that the Elector of Saxony declared himself ready to send deputies to a council to be convened at Trent, but only under the condition that the Protestants should have a share in the discussions, and that the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

should not be considered as the presiding officer and judge. As it was agreed upon to send a confession to Trent, Melanchthon drew up the ''Confessio Saxonica'' which is a repetition of the Augsburg Confession, discussing, however, in greater detail, but with moderation, the points of controversy with Rome. He on his way to Trent at Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

saw the military preparations of Maurice of Saxony, and after proceeding as far as Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, returned to Wittenberg in March 1552, for Maurice had turned against the emperor. Owing to his act, the condition of the Protestants became more favourable and were still more so at the Peace of Augsburg (1555), but Melanchthon's labours and sufferings increased from that time.

The last years of his life were embittered by the disputes over the Interim and the freshly started controversy on the Lord's Supper. As the statement "good works are necessary for salvation" appeared in the Leipzig Interim, its Lutheran opponents attacked in 1551 Georg Major

Georg Major (April 25, 1502 – November 28, 1574) was a Lutheran theologian of the Protestant Reformation.

Life

Major was born in Nuremberg in 1502. At the age of nine he was sent to Wittenberg, and in 1521 he entered the university there.Robe ...

, the friend and disciple of Melanchthon, so Melanchthon dropped the formula altogether, seeing how easily it could be misunderstood.

But all his caution and reservation did not hinder his opponents from continually working against him, accusing him of synergism and Zwinglianism

The theology of Ulrich Zwingli was based on an interpretation of the Bible, taking scripture as the inspired word of God and placing its authority higher than what he saw as human sources such as the ecumenical councils and the church fathers. He ...

. At the Colloquy of Worms in 1557 which he attended only reluctantly, the adherents of Flacius and the Saxon theologians tried to avenge themselves by thoroughly humiliating Melanchthon, in agreement with the malicious desire of the Catholics to condemn all heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, especially those who had departed from the Augsburg Confession, before the beginning of the conference. As this was directed against Melanchthon himself, he protested, so that his opponents left, greatly to the satisfaction of the Catholics who now broke off the colloquy, throwing all blame upon the Protestants. The Reformation in the sixteenth century did not experience a greater insult, as Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

says. Nevertheless, Melanchthon persevered in his efforts for the peace of the church, suggesting a synod of the Evangelical party and drawing up for the same purpose the Frankfurt Recess, which he defended later against the attacks of his enemies.

More than anything else the controversies on the Lord's Supper embittered the last years of his life. The renewal of this dispute was due to the victory in the Reformed Church of the Calvinistic doctrine and its influence upon Germany. To its tenets Melanchthon never gave his assent, nor did he use its characteristic formulas. The personal presence and self-impartation of Christ in the Lord's Supper were especially important for Melanchthon; but he did not definitely state how body and blood are related to this. Although rejecting the physical act of mastication, he nevertheless assumed the real presence of the body of Christ and therefore also a real self-impartation. Melanchthon differed from John Calvin also in emphasizing the relation of the Lord's Supper to justification.

Marian views

Melanchthon viewed any veneration of saints rather critically but developed positive commentaries about Mary. In his ''Annotations in Evangelia'' commenting on Luke 2:52, he discusses the faith of Mary, "she kept all things in her heart" which to Melanchthon is a call to the church to follow her example. During themarriage at Cana

The transformation of water into wine at the wedding at Cana (also called the marriage at Cana, wedding feast at Cana or marriage feast at Cana) is the first miracle attributed to Jesus in the Gospel of John.

In the Gospel account, Jesus Chris ...

, Melanchthon points out that Mary went too far, asking for more wine, misusing her position. But she was not upset, when Jesus gently scolded her. Mary was negligent, when she lost her son in the temple, but she did not sin. Mary was conceived with original sin like every other human being, but she was spared the consequences of it. Consequently, Melanchthon opposed the feast of the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception.

It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, meaning that it is held to be a divinely revealed truth w ...

, which in his days, although not dogma, was celebrated in several cities and had been approved at the Council of Basel

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

in 1439. He declared that the Immaculate Conception was an invention of monks. Mary is a representation (Typus) of the church and in the Magnificat

The Magnificat (Latin for " y soulmagnifies he Lord) is a canticle, also known as the Song of Mary, the Canticle of Mary and, in the Byzantine tradition, the Ode of the Theotokos (). It is traditionally incorporated into the liturgical servic ...

, Mary spoke for the whole church. Standing under the cross, Mary suffered like no other human being. Consequently, Christians have to unite with her under the cross, in order to become Christ-like.

Views on natural philosophy

In lecturing on the ''Librorum de judiciis astrologicis'' ofPtolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

in 1535–1536, Melanchthon expressed to students his interest in Greek mathematics, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

. He considered that a purposeful God had reasons to exhibit comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ...

s and eclipses. He was the first to print a paraphrased edition of Ptolemy's '' Tetrabiblos'' in Basel, 1554. Natural philosophy, in his view, was directly linked to Providence, a point of view that was influential in curriculum change after the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

in Germany. In the period 1536–1539 he was involved in three academic innovations: the refoundation of Wittenberg along Protestant lines, the reorganization at Tübingen, and the foundation of the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

.

Death

Before these theological dissensions were settled, Melanchthon died. Only a few days before his death, he had written a note which gave his reasons for not fearing death. On the left of the note were the words, "You will be delivered from sins, and be freed from the acrimony and fury of theologians"; on the right, "You will go to the light, see God, look upon his Son, learn those wonderful mysteries which you have not been able to understand in this life." The immediate cause of death was a severe cold which he had contracted on a journey toLeipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

in March 1560, followed by a fever that consumed his strength. His body had already been weakened by many sufferings. He was pronounced dead on 19 April 1560.

In Melanchthon's last moments, he continued to worry over the desolate condition of the church. He strengthened himself in almost uninterrupted praying and in listening to passages of Scripture. The words of John 1:11-12 were especially significant to him. "His own received him not; but as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God." When Caspar Peucer, his son-in-law, asked him if he wanted anything, he replied, "Nothing but heaven." His body was buried beside Luther's in the Schloßkirche in Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the River Elbe, north o ...

.

He is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context d ...

of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod on 16 February, his birthday, and in the calendar of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on 25 June, the date of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession.

Estimation of his works and character

Melanchthon's importance for the Reformation lay essentially in the fact that he systematized Luther's ideas, defended them in public, and made them the basis of a religious education. These two figures, by complementing each other, could be said to have harmoniously achieved the results of the Reformation. Melanchthon was impelled by Luther to work for the Reformation; his own inclinations would have kept him a student. Without Luther's influence Melanchthon would have been "a second Erasmus", although his heart was filled with a deep religious interest in the Reformation. While Luther scattered the sparks among the people, Melanchthon by his humanistic studies won the sympathy of educated people and scholars for the Reformation. Besides Luther's strength of faith, Melanchthon's many-sidedness and calmness, as well as his temperance and love of peace, had a share in the success of the movement. Both were aware of their mutual position and they thought of it as a divine necessity of their common calling. Melanchthon wrote in 1520, "I would rather die than be separated from Luther", whom he afterward compared toElijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My El (deity), God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic language, Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) w ...

, and called "the man full of the Holy Ghost

For the majority of Christian denominations, the Holy Spirit, or Holy Ghost, is believed to be the third person of the Trinity, a Triune God manifested as God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, each entity itself being God.Gru ...

". In spite of the strained relations between them in the last years of Luther's life, Melanchthon exclaimed at Luther's death, "Dead is the horseman and chariot of Israel who ruled the church in this last age of the world!"

On the other hand, Luther wrote of Melanchthon, in the preface to Melanchthon's '' Kolosserkommentar'' (1529), "I had to fight with rabble and devils, for which reason my books are very warlike. I am the rough pioneer who must break the road; but Master Philip comes along softly and gently, sows and waters heartily, since God has richly endowed him with gifts." Luther also did justice to Melanchthon's teachings, praising one year before his death in the preface to his own writings Melanchthon's revised ''Loci'' above them and calling Melanchthon "a divine instrument which has achieved the very best in the department of theology to the great rage of the devil and his scabby tribe." It is remarkable that Luther, who vehemently attacked men like Erasmus and Bucer, when he thought that truth was at stake, never spoke directly against Melanchthon, and even during his melancholy last years conquered his temper.

The strained relation between these two men never came from external things, such as human rank and fame, much less from other advantages, but always from matters of church and doctrine, and chiefly from the fundamental difference of their individualities; they repelled and attracted each other "because nature had not formed out of them one man." It cannot be denied, however, that Luther was the more magnanimous, for however much he was at times dissatisfied with Melanchthon's actions, he never uttered a word against his private character; however Melanchthon sometimes evinced a lack of confidence in Luther. In a letter to Carlowitz, before the Diet of Augsburg, he protested that Luther on account of his hot-headed nature exercised a personally humiliating pressure upon him.

On the other hand, Luther wrote of Melanchthon, in the preface to Melanchthon's '' Kolosserkommentar'' (1529), "I had to fight with rabble and devils, for which reason my books are very warlike. I am the rough pioneer who must break the road; but Master Philip comes along softly and gently, sows and waters heartily, since God has richly endowed him with gifts." Luther also did justice to Melanchthon's teachings, praising one year before his death in the preface to his own writings Melanchthon's revised ''Loci'' above them and calling Melanchthon "a divine instrument which has achieved the very best in the department of theology to the great rage of the devil and his scabby tribe." It is remarkable that Luther, who vehemently attacked men like Erasmus and Bucer, when he thought that truth was at stake, never spoke directly against Melanchthon, and even during his melancholy last years conquered his temper.

The strained relation between these two men never came from external things, such as human rank and fame, much less from other advantages, but always from matters of church and doctrine, and chiefly from the fundamental difference of their individualities; they repelled and attracted each other "because nature had not formed out of them one man." It cannot be denied, however, that Luther was the more magnanimous, for however much he was at times dissatisfied with Melanchthon's actions, he never uttered a word against his private character; however Melanchthon sometimes evinced a lack of confidence in Luther. In a letter to Carlowitz, before the Diet of Augsburg, he protested that Luther on account of his hot-headed nature exercised a personally humiliating pressure upon him.

His work as reformer

As a reformer, Melanchthon was characterized by moderation, conscientiousness, caution, and love of peace; but these qualities were sometimes said to only be lack of decision, consistence, and courage. Often, however, his actions are shown stemming not from anxiety for his own safety, but from regard for the welfare of the community and for the quiet development of the church. Melanchthon was not said to lack personal courage, but rather he was said to be less of an aggressive than of a passive nature. When he was reminded how much power and strength Luther drew from his trust inGod

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

, he answered, "If I myself do not do my part, I can not expect anything from God in prayer." His nature was seen to be inclined to suffer with faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people ofte ...

in God that he would be released from every evil

Evil, in a general sense, is defined as the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is general ...

rather than to act valiantly with his aid. The distinction between Luther and Melanchthon is well brought out in Luther's letters to the latter (June 1530):

Another trait of his character was his love of peace. He had an innate aversion to quarrels and discord; yet, often he was very irritable. His irenical character often led him to adapt himself to the views of others, as may be seen from his correspondence with Erasmus and from his public attitude from the Diet of Augsburg to the Interim. It was said not to be merely a personal desire for peace, but his conservative religious nature that guided him in his acts of conciliation. He never could forget that his father on his death-bed had besought his family "never to leave the church." He stood toward the history of the church in an attitude of piety and reverence that made it much more difficult for him than for Luther to be content with the thought of the impossibility of a reconciliation with the Catholic Church. He laid stress upon the authority of the Fathers, not only of

Another trait of his character was his love of peace. He had an innate aversion to quarrels and discord; yet, often he was very irritable. His irenical character often led him to adapt himself to the views of others, as may be seen from his correspondence with Erasmus and from his public attitude from the Diet of Augsburg to the Interim. It was said not to be merely a personal desire for peace, but his conservative religious nature that guided him in his acts of conciliation. He never could forget that his father on his death-bed had besought his family "never to leave the church." He stood toward the history of the church in an attitude of piety and reverence that made it much more difficult for him than for Luther to be content with the thought of the impossibility of a reconciliation with the Catholic Church. He laid stress upon the authority of the Fathers, not only of Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

, but also of the Greek Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

.

His attitude in matters of worship was conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, and in the Leipsic Interim he was said by Cordatus and Schenk even to be Crypto-Catholic. He never strove for a reconciliation with Catholicism at the price of pure doctrine. He attributed more value to the external appearance and organization of the Church than Luther did, as can be seen from his whole treatment of the "doctrine of the church". The ideal conception of the church, which the reformers opposed to the organization of the Roman Church, which was expressed in his ''Loci'' of 1535, lost for him after 1537 its former prominence, when he began to emphasize the conception of the true visible church as it may be found among the Protestants.

He believed that the relation of the church to God was that the church held the divine office of the ministry of the Gospel. The universal priesthood was for Melanchthon as for Luther no principle of an ecclesiastical constitution, but a purely religious principle. In accordance with this idea Melanchthon tried to keep the traditional church constitution and government, including the bishops. He did not want, however, a church altogether independent of the state, but rather, in agreement with Luther, he believed it the duty of the secular authorities to protect religion and the church. He looked upon the consistories as ecclesiastical courts which therefore should be composed of spiritual and secular judges, for to him the official authority of the church did not lie in a special class of priests, but rather in the whole congregation, to be represented therefore not only by ecclesiastics, but also by laymen. Melanchthon in advocating church union did not overlook differences in doctrine for the sake of common practical tasks.

The older he grew, the less he distinguished between the Gospel as the announcement of the will of God, and right doctrine as the human knowledge of it. Therefore, he took pains to safeguard unity in doctrine by theological formulas of union, but these were made as broad as possible and were restricted to the needs of practical religion.

As scholar

As a scholar Melanchthon embodied the entire spiritual culture of his age. At the same time he found the simplest, clearest, and most suitable form for his knowledge; therefore his manuals, even if they were not always original, were quickly introduced into schools and kept their place for more than a century. Knowledge had for him no purpose of its own; it existed only for the service of moral and religious education, and so the teacher of Germany prepared the way for the religious thoughts of the Reformation. He was, alongside other luminaries such as Erasmus, an important figure in the movement sometimes called

As a scholar Melanchthon embodied the entire spiritual culture of his age. At the same time he found the simplest, clearest, and most suitable form for his knowledge; therefore his manuals, even if they were not always original, were quickly introduced into schools and kept their place for more than a century. Knowledge had for him no purpose of its own; it existed only for the service of moral and religious education, and so the teacher of Germany prepared the way for the religious thoughts of the Reformation. He was, alongside other luminaries such as Erasmus, an important figure in the movement sometimes called Christian humanism

Christian humanism regards humanist principles like universal human dignity, individual freedom, and the importance of happiness as essential and principal or even exclusive components of the teachings of Jesus. Proponents of the term trace the c ...

, which has exerted a lasting influence upon scientific life in Germany. His works were not always new and original, but they were clear, intelligible, and answered their purpose. His style is natural and plain, better, however, in Latin and Greek than in German. He was not without natural eloquence, although his voice was weak.

Melanchthon wrote numerous treatises dealing with education and learning that present some of his key thoughts on learning, including his views on the basis, method, and goal of reformed education. In his "Book of Visitation", Melanchthon outlines a school plan that recommends schools to teach Latin only. Here he suggests children should be broken up into three distinct groups: children who are learning to read, children who know how to read and are ready to learn grammar, and children who are well-trained in grammar and syntax. Melanchthon also believed that the disciplinary system of the classical "seven liberal arts", and the sciences studied in the higher faculties could not encompass the new revolutionary discoveries of the age in terms of either content or method. He expanded the traditional categorization of science in several directions, incorporating not only history, geography and poetry but also the new natural sciences in his system of scholarly disciplines.

As theologian

As a theologian, Melanchthon did not show so much creative ability, but rather a genius for collecting and systematizing the ideas of others, especially of Luther, for the purpose of instruction. He kept to the practical, and cared little for connection of the parts, so his ''Loci'' were in the form of isolated paragraphs. The fundamental difference between Luther and Melanchthon lies not so much in the latter's ethical conception, as in his humanistic mode of thought which formed the basis of his theology and made him ready not only to acknowledge moral and religious truths outside of Christianity, but also to bring Christian truth into closer contact with them, and thus to mediate between Christian revelation and ancient philosophy. Melanchthon's views differed from Luther's only in some modifications of ideas. Melanchthon looked upon the law as not only the correlate of the Gospel, by which its effect of salvation is prepared, but as the unchangeable order of the spiritual world which has its basis in God himself. He furthermore reduced Luther's much richer view of redemption to that of legal satisfaction. He did not draw from the vein of mysticism running through Luther's theology, but emphasized the ethical and intellectual elements. After giving up determinism and absolute predestination and ascribing to man a certain moral freedom, he tried to ascertain the share offree will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to ac ...

in conversion, naming three causes as concurring in the work of conversion, the Word, the Spirit, and the human will, not passive, but resisting its own weakness. Since 1548 he used the definition of freedom formulated by Erasmus, "the capability of applying oneself to grace."

His definition of faith lacks the mystical depth of Luther. In dividing faith into knowledge, assent, and trust, he made the participation of the heart subsequent to that of the intellect, and so gave rise to the view of the later orthodoxy that the establishment and acceptation of pure doctrine should precede the personal attitude of faith. To his intellectual conception of faith corresponded also his view that the Church also is only the communion of those who adhere to the true belief and that her visible existence depends upon the consent of her unregenerated members to her teachings.

Finally, Melanchthon's doctrine of the Lord's Supper, lacking the profound mysticism of faith by which Luther united the sensual elements and supersensual realities, demanded at least their formal distinction.

The development of Melanchthon's beliefs may be seen from the history of the ''Loci''. In the beginning Melanchthon intended only a development of the leading ideas representing the Evangelical conception of salvation, while the later editions approach more and more the plan of a text-book of dogma. At first he uncompromisingly insisted on the necessity of every event, energetically rejected the philosophy of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

, and had not fully developed his doctrine of the sacraments. In 1535 he treated for the first time the doctrine of God and that of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

; rejected the doctrine of the necessity of every event and named free will as a concurring cause in conversion. The doctrine of justification received its forensic form and the necessity of good works was emphasized in the interest of moral discipline. The last editions are distinguished from the earlier ones by the prominence given to the theoretical and rational element.

As moralist

In ethics Melanchthon preserved and renewed the tradition of ancient morality and represented the Protestant conception of life. His books bearing directly on morals were chiefly drawn from the classics, and were influenced not so much by Aristotle as byCicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

. His principal works in this line were ''Prolegomena'' to Cicero's '' De officiis'' (1525); ''Enarrationes librorum Ethicorum Aristotelis'' (1529); ''Epitome philosophiae moralis'' (1538); and ''Ethicae doctrinae elementa'' (1550).

In his ''Epitome philosophiae moralis'' Melanchthon first considers the relation of philosophy to the law of God and the Gospel. Moral principles are knowable in the light of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

. Melanchthon calls these the law of God, and being endowed

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to the will of its founders and donors. Endowments are of ...

in human nature by God, so also the law of nature. The virtuous pagans had not yet developed the ideas of Original Sin and the Fall, or the fallen aspect of human nature itself, and so could not articulate or explain why humans did not always act virtuously. If virtue was the true law of human nature (having been put there by God himself) than the light of reason could only by darkened by sin. The revealed law, necessitated because of sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

, is distinguished from natural law only by its greater completeness and clearness. The fundamental order of moral life can be grasped also by reason; therefore the development of moral philosophy from natural principles must not be neglected. Melanchthon therefore made no sharp distinction between natural and revealed morals.

His contribution to Christian ethics in the proper sense must be sought in the Augsburg Confession and its Apology as well as in his ''Loci'', where he followed Luther in depicting the Protestant ideal of life, the free realization of the divine law by a personality blessed in faith and filled with the spirit of God.

As exegete

Melanchthon's formulation of the authority of Scripture became the norm for the following time. The principle of his hermeneutics is expressed in his words: "Every theologian and faithful interpreter of the heavenly doctrine must necessarily be first a grammarian, then a dialectician, and finally a witness." By "grammarian" he meant thephilologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

in the modern sense who is master of history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

, archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

, and ancient geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

. As to the method of interpretation, he insisted with great emphasis upon the unity of the sense, upon the literal sense in contrast to the four senses of the scholastics. He further stated that whatever is looked for in the words of Scripture, outside of the literal sense, is only dogmatic or practical application.

His commentaries, however, are not grammatical, but are full of theological and practical matter, confirming the doctrines of the Reformation, and edifying believers. The most important of them are those on Genesis, Proverbs

A proverb (from la, proverbium) is a simple and insightful, traditional saying that expresses a perceived truth based on common sense or experience. Proverbs are often metaphorical and use formulaic language. A proverbial phrase or a proverbia ...

, Daniel, the Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

, and especially those on the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

, on Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

(edited in 1522 against his will by Luther), Colossians

The Epistle to the Colossians is the twelfth book of the New Testament. It was written, according to the text, by Paul the Apostle and Timothy, and addressed to the church in Colossae, a small Phrygian city near Laodicea and approximately f ...

(1527), and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

(1523). Melanchthon was the constant assistant of Luther in his translation of the Bible, and both the books of the Maccabees in Luther's Bible are ascribed to him. A Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

Bible published in 1529 at Wittenberg is designated as a common work of Melanchthon and Luther.

As historian and preacher

In the sphere of historical theology the influence of Melanchthon may be traced until the seventeenth century, especially in the method of treating

In the sphere of historical theology the influence of Melanchthon may be traced until the seventeenth century, especially in the method of treating church history

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritua ...

in connection with political history

Political history is the narrative and survey of political events, ideas, movements, organs of government, voters, parties and leaders. It is closely related to other fields of history, including diplomatic history, constitutional history, socia ...

. His was the first Protestant attempt at a history of dogma, ''Sententiae veterum aliquot patrum de caena domini'' (1530) and especially ''De ecclesia et auctoritate verbi Dei'' (1539).

Melanchthon exerted a wide influence in the department of homiletics, and has been regarded as the author, in the Protestant church, of the methodical style of preaching. He himself keeps entirely aloof from all mere dogmatizing or rhetoric in the ''Annotationes in Evangelia'' (1544), the ''Conciones in Evangelium Matthaei'' (1558), and in his German sermons prepared for George of Anhalt. He never preached from the pulpit; and his Latin sermons ''(Postilla)'' were prepared for the Hungarian students at Wittenberg who did not understand German. In this connection may be mentioned also his ''Catechesis puerilis'' (1532), a religious manual for younger students, and a German catechism (1549), following closely Luther's arrangement.

From Melanchthon came also the first Protestant work on the method of theological study, so that it may safely be said that by his influence every department of theology was advanced even if he was not always a pioneer.

As professor and philosopher

Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin (; sometimes called Johannes; 29 January 1455 – 30 June 1522) was a German Catholic humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew, whose work also took him to modern-day Austria, Switzerland, and Italy and France. Most of Reuchlin's ...

, Jakob Wimpfeling, and Rodolphus Agricola, who represented an ethic

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

al conception of the humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at the t ...

. The liberal arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term '' art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically th ...

and a classical education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

were for him paths, not only towards natural and ethical philosophy, but also towards divine philosophy. The ancient classics were for him in the first place the sources of a purer knowledge, but they were also the best means of educating the youth both by their beauty of form and by their ethical content. By his organizing activity in the sphere of educational institutions and by his compilations of Latin and Greek grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domain ...

s and commentaries, Melanchthon became the founder of the learned schools of Evangelical Germany, a combination of humanistic and Christian ideals. In philosophy also Melanchthon was the teacher of the whole German Protestant world. The influence of his philosophical compendia ended only with the rule of the Leibniz-Wolff school.

He started from scholasticism; but with the contempt of an enthusiastic Humanist he turned away from it and came to Wittenberg with the plan of editing the complete works of Aristotle. Under the dominating religious influence of Luther his interest abated for a time, but in 1519 he edited the '' Rhetoric'' and in 1520 the ''Dialectic''.

The relation of philosophy to theology is characterized, according to him, by the distinction between Law and Gospel. The former, as a light of nature, is innate; it also contains the elements of the natural knowledge of God which, however, have been obscured and weakened by sin. Therefore, renewed promulgation of the Law by revelation became necessary and was furnished in the Decalogue; and all law, including that in the form of natural philosophy, contains only demands, shadowings; its fulfillment is given only in the Gospel, the object of certainty in theology, by which also the philosophical elements of knowledge – experience, principles of reason, and syllogism – receive only their final confirmation. As the law is a divinely ordered pedagogue that leads to Christ, philosophy, its interpreter, is subject to revealed truth as the principal standard of opinions and life.

Besides Aristotle's ''Rhetoric'' and ''Dialectic'' he published ''De dialecta libri iv'' (1528), ''Erotemata dialectices'' (1547), ''Liber de anima'' (1540), ''Initia doctrinae physicae'' (1549), and ''Ethicae doctrinae elementa'' (1550).

Personal appearance and character