Philibert Tsiranana (18 October 1912 – 16 April 1978) was a

Malagasy politician and leader, who served as the first

President of Madagascar from 1959 to 1972.

During the twelve years of his administration, the Republic of Madagascar experienced institutional stability that stood in contrast to the political turmoil many mainland African countries experienced in this period. This stability contributed to Tsiranana's popularity and his reputation as a remarkable statesman. Madagascar experienced moderate economic growth under his

social democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

policies and came to be known as "the Happy Island." However, the electoral process was fraught with issues and his term ultimately terminated in

a series of farmer and student protests that brought about the end of the First Republic and the establishment of the officially socialist

Second Republic.

The "benevolent schoolmaster" public image that Tsiranana cultivated went alongside a firmness of convictions and actions that some believe tended toward

authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

. Nonetheless, he remains an esteemed Malagasy political figure remembered throughout the country as its "Father of Independence".

Early life (1910–1955)

From cattle herder to teacher

According to his official biography, Tsiranana was born on 18 October 1912 in

Ambarikorano,

Sofia Region

Sofia is a region in northern Madagascar. It is named for the Sofia River. The region covers 50,100 km² and had a population of 1,500,227 in 2018. The administrative capital is Antsohihy.

Administrative divisions

Sofia Region is divided in ...

, in northeastern Madagascar.

[Charles Cadoux. Philibert Tsiranana. In Encyclopédie Universalis. Universalia 1979 – Les évènements, les hommes, les problèmes en 1978. p.629][André Saura. ''Philibert Tsiranana, 1910-1978 premier président de la République de Madagascar''. Tome I. Éditions L’Harmattan. 2006. p.13] Born to Madiomanana and Fisadoha Tsiranana,

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

cattle rancher

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

s from the

Tsimihety

The Tsimihety are a Malagasy ethnic group who are found in the north-central region of Madagascar.[Tsimihety]

E ...

ethnic group,

[ Philibert was destined to become a cattle rancher himself.][Biographies des députés de la IVe République : Philibert Tsiranana]

/ref>[Charles Cadoux. Philibert Tsiranana. In ''Encyclopédie Universalis''. 2002 Edition.] However, following the death of his father in 1923, Tsiranana's brother, Zamanisambo, suggested that he attend a primary school

A primary school (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and South Africa), junior school (in Australia), elementary school or grade school (in North America and the Philippines) is a school for primary e ...

in Anjiamangirana.

A brilliant student, Tsiranana was admitted into the Analalava

Analalava is a coastal town and commune ( mg, kaominina) in north-western Madagascar over the Mozambique Channel. It is approximately 150 kilometres north of Mahajanga and some 430 kilometres north of the capital Antananarivo. It belongs to the ...

regional school in 1926, where he graduated with a brevet des collèges

The National Diploma (French: ''Le Diplôme National du Brevet des Collèges'') is a diploma given to French pupils at the end of 3e (year 10 / ninth grade), This diploma is awarded to students who are or were within French cultural influence, ...

.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.15] In 1930, he enrolled in the Le Myre de Vilers normal school

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high school level, turni ...

in Tananarive

Antananarivo ( French: ''Tananarive'', ), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana, is the capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra ("Antananarivo-Mother Hill" or "An ...

, named after former resident-general of Madagascar Charles Le Myre de Vilers

Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (17 February 1833 – 9 March 1918) was French naval officer, then departmental administrator.

He was governor of the colony of Cochinchina (1879–1882) and resident-general of Madagascar (1886–1888).

He was a ...

, where he entered the "Section Normale" program, preparing him for a career teaching in primary schools.[ After completing his studies, he started a teaching career in his hometown. In 1942, he began receiving instruction in ]Tananarive

Antananarivo ( French: ''Tananarive'', ), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana, is the capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra ("Antananarivo-Mother Hill" or "An ...

for middle school

A middle school (also known as intermediate school, junior high school, junior secondary school, or lower secondary school) is an educational stage which exists in some countries, providing education between primary school and secondary school. ...

teaching and in 1945, he succeeded in the teacher assistant competitive examinations, allowing him to serve as a professor in a regional school.[ In 1946, he obtained a scholarship to the École normale d'instituteurs in ]Montpellier

Montpellier (, , ; oc, Montpelhièr ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the department of Hérault. In 2018, 290,053 people l ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where he worked as a teacher assistant. He left Madagascar on 6 November.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.17]

From communism to PADESM

In 1943, Philibert Tsiranana joined the professional teachers' union and in 1944 entered the General Confederation of Labor (CGT).[ With the end of World War II and the creation of the ]French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was the formal end of the "indigenous" () status of French subj ...

by the Fourth Republic, the colonial society of Madagascar experienced a liberalization. The colonized peoples now had the right to be politically organized. Tsiranana joined the Group of Student Communists (GEC) of Madagascar in January 1946, on the advice of his mentor Paul Ralaivoavy.[ He assumed the role of treasurer.][ The GEC enabled him to meet future leaders of the PADESM (Party of the Disinherited of Madagascar), which he became a founding member of in June 1946.][

The PADESM was a political organization composed mainly of and from the coastal region. The PADESM came about as a result of the holding of the French constituent elections of 1945 and 1946. For the first time, the people of Madagascar were allowed to participate in French elections, with electing settlers and indigenous people to the ]French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are kn ...

.[ To ensure that they won one of the two seats allotted to native people of Madagascar, the inhabitants of the coastal region made an agreement with the Mouvement démocratique de la rénovation malgache (MDRM) which was controlled by the ]Merina

The Merina people (also known as the Imerina, Antimerina, or Hova) are the largest ethnic group in Madagascar.[Merina ...]

of the uplands.[In the precolonial period, the Malagasy aristocracy had been almost entirely composed of the Merina.] The coastal people agreed to seek the election of Paul Ralaivoavy in the west,[ while leaving the east to the Merina candidate, Joseph Ravoahangy. This agreement was not honoured and the Merina won the second seat in October 1945 and June 1946.][ Concerned about the possible return of "Merina control," the coastal people founded PADESM in order to counter the nationalist goals of the MDRM and oppose Malagasy independence - a position justified by Tsiranana in 1968:

In July 1946, Tsiranana refused the post of secretary general of PADESM on account of his impending departure for the École normale de ]Montpellier

Montpellier (, , ; oc, Montpelhièr ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the department of Hérault. In 2018, 290,053 people l ...

.[ Tsiranana had become known for his contributions to PADESM's journal ''Voromahery'',][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.16] authored under the pseudonym "Tsimihety" (derived from his birthplace).

Period in France

As a result of his journey to France,[ Tsiranana escaped the ]Malagasy Uprising

The Malagasy Uprising (french: Insurrection malgache; mg, Tolom-bahoaka tamin' ny 1947) was a Malagasy nationalist rebellion against French colonial rule in Madagascar, lasting from March 1947 to February 1949. Starting in late 1945, Madagasca ...

of 1947 and its bloody suppression.[ Moved by the events, Tsiranana participated in an anti-colonial protest in Montpellier on 21 February 1949, although not a supporter of independence.][

During his time in France, Tsiranana became conscious of the bias towards the Malagasy elite in education. He found that only 17 of the 198 Malagasy students in France were coastal people.][ In his view, there could never be a free union between all Malagasy while a cultural gap remained between the coastal people and the people of the highlands.][ To remedy this gap, he established two organisations in Madagascar: the Association of Coastal Malagasy Students (AEMC) in August 1949, and then the Cultural Association of Coastal Malagasy Intellectuals (ACIMCO) in September 1951. These organisations were resented by the Merina and were held against him.][

On his return to Madagascar in 1950, Tsiranana was appointed professor of technical education at the École industrielle in Tananarive in the highlands. There he taught French and mathematics. But he was uncomfortable at this school and transferred to the École « Le Myre de Vilers », where his abilities were more appreciated.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.18]

Progressivist ambitions

Renewing his activities with PADESM, Tsiranana campaigned to reform the left wing of the party.

Renewing his activities with PADESM, Tsiranana campaigned to reform the left wing of the party.[ He considered the directorial committee very disloyal to the administration.][ In article published on 24 April 1951 in ''Varomahery'', entitled "Mba Hiraisantsika" (To unite us), he called for reconciliation between the coastal people and the Merina in advance of the forthcoming legislative elections.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.20] In October he launched an appeal in the bimonthly ''Ny Antsika'' ("Our thing") which he had founded, an appeal to the Malagasy elites to "form a single tribe".[ This appeal to unity concealed a political plan: Tsiranana aspired to take part in the 1951 legislative elections as a candidate for the west coast.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.21] The tactic failed because far from creating agreement, it led to suspicion among the coastal political class that he was a communist,[ and he was forced to renounce his candidature in favour of the "moderate" Raveloson-Mahasampo.][

On 30 March 1952, Tsiranana was elected provincial counsellor for the 3rd district of ]Majunga

Mahajanga (French: Majunga) is a city and an administrative district on the northwest coast of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: Rép ...

on the "Social Progress" list.[ He combined this role with that of Counsellor on the Representative Assembly of Madagascar.][ Seeking a position in the French government, he offered himself as a candidate in the elections organised by the Territorial Assembly of Madagascar in May 1952 for the five senators of the Council of the Republic.][ Since two of these seats were reserved for French citizens,][The participation of the French colonies in the French parliament was introduced in 1945. In order to ensure the representation of natives and colonists, elections were conducted by a "double electoral college." In this system, each of the colleges woted for its own candidates. The native college was the college of the "Citizens of the French Union", also called the "College of the natives" or the "second college". Initially, citizenship of the French Union was granted to natives on the basis of their status as chiefs, veterans, officials, etc. Citizens of France were also granted citizenship of the French Union and could vote either in the college reserved for them or in the second college.] Tsiranana was only allowed to stand for one of the three seats reserved for native people. He was beaten by Pierre Ramampy, Norbert Zafimahova, and Ralijaona Laingo.[ Effected by this defeat, Tsiranana accused the administration of "racial discrimination."][ Along with other native counsellors, he proposed the establishment of a single electoral college to ]French Prime Minister

The prime minister of France (french: link=no, Premier ministre français), officially the prime minister of the French Republic, is the head of government of the French Republic and the leader of the Council of Ministers.

The prime minister i ...

Pierre Mendès France

Pierre Isaac Isidore Mendès France (; 11 January 190718 October 1982) was a French politician who served as prime minister of France for eight months from 1954 to 1955. As a member of the Radical Party, he headed a government supported by a co ...

.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.22]

In the same year, Tsiranana joined the new Malagasy Action, a "third party between radical nationalists and supporters of the status quo,"[ which sought to establish social harmony through equality and justice. Tsiranana hoped to establish a national profile for himself and transcend the coastal and regional character of PADESM, especially since he no longer supported Madagascar simply being a free state of the ]French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was the formal end of the "indigenous" () status of French subj ...

, but sought full independence from France.[

]

Rise to Power (1956–1958)

Malagasy Deputy in the French National Assembly

In 1955, while visiting France on administrative live, Tsiranana joined the

In 1955, while visiting France on administrative live, Tsiranana joined the French Section of the Workers' International

The French Section of the Workers' International (french: Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO) was a political party in France that was founded in 1905 and succeeded in 1969 by the modern-day Socialist Party. The SFIO was foun ...

(SFIO), in advance of the January 1956 elections for seats in the French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are kn ...

.[ During his electoral campaign, Tsiranana was able to count on the support of the Malagasy National Front (FNM), led by Merina who had left Malagasy Action, and especially on the support of the High Commissioner André Soucadaux, who saw Tsiranana as the most reasonable of the nationalists seeking election.][ Thanks to this support and the following which he had built up over the previous five years, Tsiranana was elected as deputy for the western region, with 253,094 of the 330,915 votes.][

In the ]Palais Bourbon

The Palais Bourbon () is the meeting place of the National Assembly, the lower legislative chamber of the French Parliament. It is located in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, on the '' Rive Gauche'' of the Seine, across from the Place de la Con ...

, Tsiranana joined the socialist group.[ He rapidly gained a reputation as a frank talker; in March 1956, he affirmed the dissatisfaction of the Malagasy with the ]French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was the formal end of the "indigenous" () status of French subj ...

which he characterised as simply a continuation of savage colonialism: "All this is just a facade - the foundation remains the same."[ On arrival, he demanded the repeal of the annexation law of August 1896.][ Finally, in July 1956, he called for reconciliation, demanding the release of all prisoners from the 1947 insurrection.][ By combining calls for friendship with France, political independence and national unity, Tsiranana acquired a national profile.][

His position as deputy also gave him the opportunity to demonstrate his local political interests. Through his stress on equality, he obtained a majority in the Malagasy Territorial Assembly for his personal bastion in the north and northwest.][ In addition, he worked energetically in favour of decentralisation - ostensibly in order to improve economic and social services. As a result, he received harsh criticism from some members of the ]French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European ...

(PCF) who were allied to ardent nationalists in Tananarive and accused him of seeking to " Balkanise" Madagascar.[ Tsiranana developed a firm anti-communist attitude as a result.][ This support for private property led him to submit his only bill of law on 20 February 1957, proposing "increased penalties for cattle thieves," which the French penal code did not take into account.][

]

Creation of PSD and the Loi Cadre Defferre

Tsiranana increasingly made himself the leader of the coastal people.[ On 28 December 1956, he founded the Social Democratic Party (PSD) at ]Majunga

Mahajanga (French: Majunga) is a city and an administrative district on the northwest coast of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: Rép ...

with people from the left wing of PADESM, including André Resampa.[ The new party was affiliated to the SFIO.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.31] The PSD was more or less the heir of PADESM, but rapidly exceeded PADESM's limits,[ since it simultaneously appealed to rural nobles on the coast, officials, and anti-communists in favour of independence.][ From the beginning, his party benefitted from the support of the colonial administration, which was in the process of transferring executive power in accordance with the Loi Cadre Defferre.

The entry into force of the Loi Cadre was expected to take place after the 1957 territorial elections. On 31 March, Tsiranana was re-elected as a provincial counsellor on the "Union and Social Progress" list with 79,991 votes out of 82,121.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.32] Since he was head of the list, he was named president of the Majunga Provincial Assembly on 10 April 1957.[ On 27 March, this assembly selected an executive council. Tsiranana's PSD had only nine seats in the representative assembly.][ A coalition government was formed with Tsiranana at its head as vice-president and the High Commissioner André Soucadaux as president ''de jure''.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.33] Tsiranana succeeded in getting his closest supporter, André Resampa, appointed as minister of education.[

Once in power, Tsiranana slowly consolidated his authority. On 12 June 1957, a second section of PSD was founded in ]Toliara

Toliara (also known as ''Toliary'', ; formerly ''Tuléar'') is a city in Madagascar.

It is the capital of the Atsimo-Andrefana region, located 936 km southwest of national capital Antananarivo.

The current spelling of the name was adopted ...

province.[ Sixteen counsellors of the provincial assembly joined it and the PSD thus took control of Toliara.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.34] Like most African politicians in power in the French Union, Tsiranana publicly complained about the limitations on his power as vice-president of the council.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.36] In April 1958, during the 3rd PSD party congress, Tsiranana attacked the Loi Cadre and the bicephalous character which it imposed on the council and the fact that the presidency of the Malagasy government was held by the high commissioner.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.37] The assumption of power by Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

in June 1958 changed the situation. By a national government ordinance, the hierarchy of the colonial territories was modified in favour of local politicians.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.44] Thus, on 22 August 1958, Tsiranana officially became the President of the Executive Council of Madagascar.[

]

Malagasy Republic within the French Community (1958–1960)

Promotion of the Franco-African Community

Despite this activity, Tsiranana was more a supporter of strong autonomy rather than independence.

Despite this activity, Tsiranana was more a supporter of strong autonomy rather than independence.[ He advocated a very moderate nationalism:

:

On his return to power in 1958, Charles de Gaulle decided to accelerate the process of decolonisation. The ]French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was the formal end of the "indigenous" () status of French subj ...

was to be replaced by a new organisation.[Jean-Marcel Champion, « Communauté française » in ''Encyclopédie Universalis'', 2002 edition.] De Gaulle appointed a consultative committee, including many African and Malagasy politicians, on 23 July 1958.[ Its discussion concentrated essentially on the nature of the links between France and her former colonies.][ The Ivoirien ]Félix Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny (; 18 October 1905 – 7 December 1993), affectionately called Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux ("The Old One"), was the first president of Ivory Coast, serving from 1960 until his death in 1993. A tribal chief, he wo ...

proposed the establishment of a Franco-African "Federation," while Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor (; ; 9 October 1906 – 20 December 2001) was a Senegalese poet, politician and cultural theorist who was the first president of Senegal (1960–80).

Ideologically an African socialist, he was the major theoretician o ...

of Senegal pushed for a "confederation."[ In the end the concept of "community", suggested to Tsiranana by ]Raymond Janot

Raymond Janot (March 9, 1917, Paris – November 25, 2000, Paris) was a French politician who played a significant role in the writing of the 1958 Constitution of France.

World War II

Janot was with the French forces in World War II in 1939 and ...

, one of the editors of the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, which was chosen.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.64]

Naturally, Tsiranana actively campaigned, along with the Union of Social Democrats of Madagascar (UDSM) led by senator Norbert Zafimahova, for the "yes" vote in the referendum on whether Madagascar should join the French Community

The French Community (1958–1960; french: Communauté française) was the constitutional organization set up in 1958 between France and its remaining African colonies, then in the process of decolonization. It replaced the French Union, which ...

, which was held on 28 September 1958.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.48] The "no" campaign was led by the Union of Malagasy Peoples (UPM).[ The "yes" vote won with 1,361,801 votes, compared to 391,166 votes for "no".][ On the basis of this vote, Tsiranana secured the repeal of the annexation law of 1896.][ On 14 October 1958, during a meeting of the provincial counsellors, Tsiranana proclaimed the autonomous ]Malagasy Republic

The Malagasy Republic ( mg, Repoblika Malagasy, french: République malgache) was a state situated in Southeast Africa. It was established in 1958 as an autonomous republic within the newly created French Community, became fully independent i ...

, of which he became the provisional prime minister.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.50] The next day, the annexation law of 1896 was repealed.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.51]

Political manoeuvres against the opposition

On 16 October 1958, the congress elected a national assembly of 90 members for drafting a constitution, by means of a majority general ballot for each province.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.52] This method of election ensured that PSD and UDSM would not face any opposition in the assembly from the parties which campaigned for a "no" vote in the referendum.[ Norbert Zafimahova was chosen as president of the assembly.

In reaction to the creation of this assembly, the UPM, FNM and the Association of Peasants' Friends merged to form a single party, the Congress Party for the Independence of Madagascar (AKFM), led by the priest Richard Andriamanjato, on 19 October.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.54] This party was Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

and became the principal opposition to the government.[

Tsiranana rapidly instituted state infrastructure in the provinces which enabled him to contain AKFM.][ In particular, he appointed secretaries of state in all the provinces.][ Then, on 27 January, he dissolved the municipal council of Diego Suarez, which was controlled by the Marxists.][ Finally, on 27 February 1959, he passed a law introducing the "offense of contempt for national and communal institutions" and used this to sanction certain publications.][

]

Election as President of the Malagasy Republic

On 29 April 1959, the constitutional assembly accepted the constitution proposed by the government.[Patrick Rajoelina. ''Quarante années de la vie politique de Madagascar 1947-1987''. Éditions L’Harmattan. 1988. p.25] It was largely modelled on the Constitution of France

The current Constitution of France was adopted on 4 October 1958. It is typically called the Constitution of the Fifth Republic , and it replaced the Constitution of the Fourth Republic of 1946 with the exception of the preamble per a Consti ...

, but with some unique characteristics.[Charles Cadoux. Madagascar. In ''Encyclopédie Universalis''. 2002 Edition.] The Head of State

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

was the Head of Government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a ...

and held all executive power;[ the vice-president had only a very minor role.][ The legislature was to be ]bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single gr ...

, unusually for Francophone African countries of that time.[ The provinces, with their own provincial councils, had a degree of autonomy.][ On the whole the government structure was that of a moderate presidential system, rather than a parliamentary one.][

On 1 May, the parliament elected a college consisting of provincial counsellors and an equal number of delegates from communities, which was to select the first President of the Republic.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.57] Four candidates were nominated: Philibert Tsiranana, Basile Razafindrakoto, Prosper Rajoelson and Maurice Curmer.[ In the end, Tsiranana was unanimously elected as the first president of the Malagasy Republic with 113 votes (and one abstention).][

] On 24 July 1959, Charles de Gaulle appointed four responsible African politicians, of whom Tsiranana was one, to the position of "Minister-Counsellor" of the French government for the affairs of the French Community.

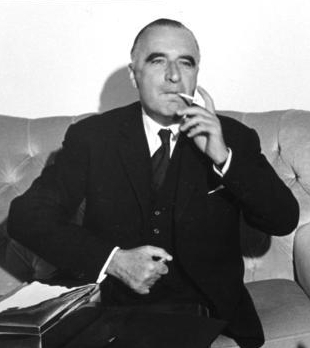

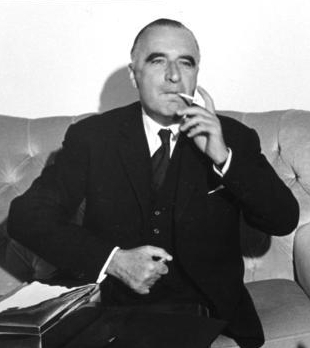

On 24 July 1959, Charles de Gaulle appointed four responsible African politicians, of whom Tsiranana was one, to the position of "Minister-Counsellor" of the French government for the affairs of the French Community.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.63] Tsiranana used his new powers to call for national sovereignty for Madagascar; de Gaulle accepted this.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.67] In February 1960, a Malagasy delegation led by André Resampa[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.84] was sent to Paris to negotiate the transfer of power.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.74] Tsiranana insisted that all Malagasy organisations should be represented in this delegation, except for AKFM (which he deplored).[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.75] On 2 April 1960, the Franco-Malagasy accords were signed by Prime Minister Michel Debré

Michel Jean-Pierre Debré (; 15 January 1912 – 2 August 1996) was the first Prime Minister of the French Fifth Republic. He is considered the "father" of the current Constitution of France. He served under President Charles de Gaulle from 195 ...

and President Tsiranana at the Hôtel Matignon

The Hôtel Matignon or Hôtel de Matignon () is the official residence of the Prime Minister of France. It is located in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, at 57 Rue de Varenne. "Matignon" is often used as a metonym for the governmental action o ...

.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.88] On 14 June, the Malagasy parliament unanimously accepted the accords.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.101] On 26 June, Madagascar became independent.

The "state of grace" (1960–1967)

Tsiranana sought to establish national unity through a policy of stability and moderation.[

In order to legitimise his image as the "father of independence", on 20 July 1960, Tsiranana recalled to the island the three old deputies, "exiled" to France after the 1947 rebellion: Joseph Ravoahangy, and ]Jacques Rabemananjara

Jacques Rabemananjara (23 June 1913 – 1 April 2005) was a Malagasy politician, playwright and poet. He served as a government minister, rising to Vice President of Madagascar. Rabemananjara was said to be the most prolific writer of his negr ...

.[Patrick Rajoelina. ''op. cit.'' p.31] The popular and political impact was significant.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.106] The President invited these "Heroes of 1947" to enter his second government on 10 October 1960; Joseph Ravoahangy became Minister of Health and Jacques Rabemananjara became Minister of the Economy.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.116] Joseph Raseta, by contrast, refused the offer and joined AFKM instead.[Biographies des députés de la IVe République : Joseph Raseta]

/ref>

Tsiranana frequently affirmed his membership of the western bloc:

Tsiranana's administration thus aspired to respect human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

and the press was relatively free - as was the justice system.[Ferdinand Deleris. ''Ratsiraka : socialisme et misère à Madagascar''. Éditions L’Harmattan. 1986. p.36] The Constitution of 1959 guaranteed political pluralism.[ The extreme left was allowed the right to political organisation. A fairly radical opposition existed in the form of the National Movement for the Independence of Madagascar (MONIMA), led by nationalist ]Monja Jaona

Monja Jaona (1910–1994) was a Malagasy politician and early nationalist who significantly drove political events on the island during his lifetime. He was a member of Jiny, a militant nationalist group formed in southern Madagascar in the 1940s ...

who campaigned vigorously on behalf of the very poor Malagasy of the south, while AKFM extolled "scientific socialism" and close friendship with the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

.[ Tsiranana presented himself as the protector of these parties and refused to join the "fashion" for single party states:

Many institutions also existed as potential centres of opposition on the island. The Protestant and ]Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

churches had great influence on the population. The various central unions were politically active in the urban centres. Associations, particularly of students and women, expressed themselves very freely.[

Nevertheless, Tsiranana's "democracy" had its limits. Outside the main centres, elections were rarely held in a fair and free manner.][

]

Neutralisation of opposition fiefs

In October 1959, at the municipal elections, AKFM won control of only the capital Tananarive (under Richard Andriamanjato) and Diego Suarez (under Francis Sautron).[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.66] MONIMA won the mayoralty of Toliara

Toliara (also known as ''Toliary'', ; formerly ''Tuléar'') is a city in Madagascar.

It is the capital of the Atsimo-Andrefana region, located 936 km southwest of national capital Antananarivo.

The current spelling of the name was adopted ...

(with Monja Jaona)[Patrick Rajoelina. ''op. cit.'' p.108] and the mayoralty of Antsirabe

Antsirabe () is the third largest city in Madagascar and the capital of the Vakinankaratra region, with a population of 265,018 in 2014.

In Madagascar, Antsirabe is known for its relatively cool climate (like the rest of the central region), it ...

(with Emile Rasakaiza).

By skilful political manoeuvres, Tsiranana's government took control of these mayoralties, one by one. By decree n°60.085 of 24 August 1960 it was established that "the administration of the city of Tananarive is henceforth entrusted to an official chosen by the Minister of the Interior and entitled General Delegate." This official took on practically all the prerogatives of mayor Andriamanjato.

Then, on 1 March 1961, Tsiranana "resigned" Monja Joana from his position as mayor of Toliara.[ A law of 15 July 1963, which stipulated that "the functions of the mayor and the 1st adjunct shall not be exercised by French citizens," prevented Francis Sautron from standing for re-election as mayor of Diego Suarez in the municipal elections of December 1964.

In those municipal elections, the PSD won 14 of the 36 seats on the Antsirabe municipal council; AKFM won 14 and MONIMA 8.][Gérard Roy et J.Fr. Régis Rakotontrina « La démocratie des années 1960 à Madagascar. Analyse du discours politique de l’AKFM et du PSD lors des élections municipales à Antsirabe en 1969 », Le fonds documentaire IRD]

/ref> A coalition of the two parties allowed the local leader of AKFM, Blaise Rakotomavo, to become mayor.[ A few months later, André Resampa, Minister of the Interior, declared the town ungovernable and dissolved the municipal council.][ New elections were held in 1965, which the PSD won.][

]

Toleration of parliamentary opposition

On 4 September 1960, the Malagasy held a parliamentary election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.111] The government chose a majority general ticket ballot system, in order to enable PSD's success in all regions (especially Majunga and Toliara).[ However, in the district of Tananarive city, where there was solid support for AKFM,][ the vote was proportional.][ Thus, in the capital, the PSD won two seats (with 27,911 votes) under the leadership of Joseph Ravoahangy, while AKFM, led by Joseph Raseta, won three seats with 36,271.][ At the end of the election, the PSD held 75 seats in the Assembly,][Patrick Rajoelina. ''op. cit.'' p.33] its allies held 29, and AKFM only had 3. The "3rd Force," an alliance of thirteen local parties, received some 30% of the national vote (468,000 votes), but did not obtain a single seat.[

In October 1961, the "Antsirabe meeting" took place. There, Tsiranana pledged to reduce the number of political parties on the island, which then numbered 33.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.308] The PSD then absorbed its allies and was henceforth represented in the Assembly by 104 deputies. The Malagasy political scene was split between two very unequal factions: on the one side, the PSD, which was almost a one party state; on the other, AKFM, the sole opposition party tolerated by Tsiranana in parliament. This opposition was entrenched at the legislative elections of 8 August 1965. The PSD retained 104 deputies, with 94% of the national vote (2,304,000 votes), while the AKFM picked off 3 seats with 3.4% of the vote (145,000 votes).[Patrick Rajoelina. ''op. cit.'' p.34] According to Tsiranana, the weakness of the opposition was due to the fact that its members "talk a lot but never act," unlike those of the PSD, who were he claimed supported by the majority of Malagasy because they were organised, disciplined, and in permanent contact with the working class.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.307]

Presidential election (1965)

On 16 June 1962, an institutional law established the rules for the election of the president of the Republic by universal direct suffrage.[ In February 1965, Tsiranana decided to end his seven-year term a year early and called a presidential election for 30 March 1965.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.260] Joseph Raseta, who had quit AKFM in 1963 in order to found his own party, the National Malagasy Union (FIPIMA), stood as a presidential candidate.[ An independent, Alfred Razafiarisoa, also stood.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.262] The leader of MONIMA, Monja Jaona, expressed a momentary desire to run,[ but AKFM made much of the economy of running only one opposition candidate against Tsiranana.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.261] It then discretely supported Tsiranana.[

Tsiranana's campaign ranged across the whole island, while those of his opponents were limited to local contexts by lack of money.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.279] On 30 March 1965, 2,521,216 votes were cast (the total number of people enrolled to vote was 2,583,051).[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.294] Tsiranana was re-elected as president with 2,451,441 votes, 97% of the total.[ Joseph Raseta received 54,814 votes and Alfred Razafiarisoa got 812.][

On 15 August 1965, in the legislative elections, the PSD obtained 2,475,469 votes out of 2,605,371 votes cast, in the seven districts of the country, some 95% of the vote.][ The opposition achieved 143,090 votes, principally in ]Tananarive

Antananarivo ( French: ''Tananarive'', ), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana, is the capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra ("Antananarivo-Mother Hill" or "An ...

, Diego Suarez, Tamatave

Toamasina (), meaning "like salt" or "salty", unofficially and in French Tamatave, is the capital of the Atsinanana region on the east coast of Madagascar on the Indian Ocean. The city is the chief seaport of the country, situated northeast of it ...

, Fianarantsoa

Fianarantsoa is a city (commune urbaine) in south central Madagascar, and is the capital of Haute Matsiatra Region.

History

It was built in the early 19th century by the Merina as the administrative capital for the newly conquered Betsileo kin ...

and Toliara

Toliara (also known as ''Toliary'', ; formerly ''Tuléar'') is a city in Madagascar.

It is the capital of the Atsimo-Andrefana region, located 936 km southwest of national capital Antananarivo.

The current spelling of the name was adopted ...

.[

]

"Malagasy Socialism"

With independence and the consolidation of the new institutions, the government dedicated itself to the realisation of

With independence and the consolidation of the new institutions, the government dedicated itself to the realisation of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

. The "Malagasy Socialism" which President Tsiranana concocted was intended to resolve the problems of development by providing economic and social solutions adapted to the country; he considered it pragmatic and humanitarian.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.263]

In order to analyse the country's economic situation, he held the "Malagasy Development Days" in Tananarive on the 25th and 27 April 1962.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.152] Through these national audits, it became clear that Madagascar's communication network was entirely insufficient and that there were problems surrounding access to water and electricity.[ With 5.5 million inhabitants in 1960, 89% of whom lived in the countryside, the country was underpopulated,][Pays du monde : Madagascar. In Encyclopédie Bordas, Mémoires du XXe siècle. édition 1995. Tome 17 « 1960-1969 »] but it was potentially rich in agricultural resources.[ Like most of the ]Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

, it was experiencing a demographic explosion which closely followed the 3.7% annual average increase in agricultural production.[

The Minister of economy, Jacques Rabemananjara, was therefore entrusted with three goals: the diversification of the Malagasy economy in order to make it less dependent on imports,][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.156] which exceeded US$20 million in 1969;[ reduce the deficit of the ]trade balance

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance ...

(which was US$6 million),[ in order to consolidate Madagascar's independence;][ and increase the population's ]purchasing power

Purchasing power is the amount of goods and services that can be purchased with a unit of currency. For example, if one had taken one unit of currency to a store in the 1950s, it would have been possible to buy a greater number of items than would ...

and quality of life (the GNP per capita was less than $US 101 per year in 1960).[

The economic policy instituted by Tsiranana's administration incorporated a neo-liberal ethos, combining encouragement of (national and foreign) private initiative and state intervention.][ In 1964, a five year plan was adopted, setting out the major government investment plans.][ These focused on the development of agriculture and support for farmers.][Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.19] For the realisation of this plan, it was envisaged that the private sector would contribute 55 billion Malagasy franc

The franc (ISO 4217 code ''MGF'') was the currency of Madagascar until January 1, 2005. It was subdivided into 100 centimes. In Malagasy the corresponding term for the franc is '' iraimbilanja'', and five Malagasy francs is called '' ariary''. ...

s.[Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.23] To encourage this investment, the government set out to create a regime favourable to lenders using four institutions: the Institut d'Émission Malgache, the state treasury, the Malagasy National Bank, and above all the National Investment Society,[ which participated in some of the larger Malagasy and foreign commercial and industrial enterprises.][Patrick Rajoelina. ''op. cit.'' p.32] To ensure the confidence of foreign capitalists, Tsiranana condemned the principle of nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

:

This did not prevent the government from instituting a 50% tax on commercial profits not reinvested in Madagascar.[Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.21]

Cooperatives and state intervention

If Tsiranana was entirely hostile to the idea of socialising the means of production, he was nevertheless a socialist. His government encouraged the development of cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-contro ...

s and other means of voluntary participation.[ The Israeli ]kibbutz

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming h ...

was investigated as the key to agricultural development.[ In 1962, a General Commissariat for Cooperation was created, charged with instituting cooperatives in production and commercial activity.][Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.20] In 1970, the cooperative sector held a monopoly on the harvesting of vanilla

Vanilla is a spice derived from orchids of the genus '' Vanilla'', primarily obtained from pods of the Mexican species, flat-leaved vanilla ('' V. planifolia'').

Pollination is required to make the plants produce the fruit from whic ...

.[ It completely controlled the harvesting, processing, and export of ]banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", disting ...

s.[ It played a major role in the cultivation of coffee, ]clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands (or Moluccas) in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring or fragrance in consumer products, ...

s and rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species '' Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima'' (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera '' Zizania'' and '' Porteresia'', both wild and domesticat ...

.[ In addition, large irrigation schemes were carried out by ]mixed economy

A mixed economy is variously defined as an economic system blending elements of a market economy with elements of a planned economy, markets with state interventionism, or private enterprise with public enterprise. Common to all mixed economie ...

societies,[ like SOMALAC (Society for the Management of Lake Alaotra) which supported more than 5,000 rice farmers.][

The main obstacle to development lay largely in the development of land. In order to remedy this, the state entrusted small scale work "at ground level" to the (the lowest level Malagasy administrative division equivalent to a French ]commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

).[ The fokon'olona were entitled to create rural infrastructure and small dams, within the framework of the regional development plan. In these works, they were assisted by the ]gendarmerie

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (literally, ...

, which was actively involved in national reforestation

Reforestation (occasionally, reafforestation) is the natural or intentional restocking of existing forests and woodlands ( forestation) that have been depleted, usually through deforestation, but also after clearcutting.

Management

A de ...

schemes, and by the civic service.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.320] Instituted in 1960 to combat idleness,[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.125] the civic service enabled Malagasy youth to acquire a general education and professional training.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.202]

Education as a motor for development

In the area of education, an effort to increase the literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in Writing, written form in some specific context of use. In other wo ...

of the rural population was undertaken, with the civic service's young conscripts playing a notable role.[ Primary education was available in most cities and villages.][ The expenditure on education exceeded 8 billion Malagasy francs in 1960 and was more than 20 billion by 1970 - a rise from 5.8% to 9.0% of ]GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is ofte ...

. This enabled the primary school workforce to be doubled from 450,000 to nearly a million, the secondary school workforce to be quadrupled from 26,000 to 108,000 and the higher education workforce to be sextupled from 1,100 to 7,000. Lycées

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children betwee ...

were opened in all provinces,[ as well as the transformation of the Centre of Higher Studies of Tananarive into the ]University of Madagascar

The University of Madagascar was the former name of the centralized public university system in Madagascar, although the original branch in Antananarivo is still sometimes called by that name.

The system traces its history to 16 December 1955, an ...

in October 1961.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.62] As a result of this increased education, Tsiranana planned to establish a number of Malagasy technical and administrative groups.[

]

Economic results (1960–1972)

In the end, of the 55 billion Malagasy Francs expected from the private sector in the first five-year plan, only 27.2 were invested between 1964 and 1968.[ The objective had however been exceeded in the ]secondary sector

In macroeconomics, the secondary sector of the economy is an economic sector in the three-sector theory that describes the role of manufacturing. It encompasses industries that produce a finished, usable product or are involved in construc ...

, with 12.44 billion Malagasy francs rather than the projected 10.7 billion.[ Industry remained embryonic,][Gérald Donque. Madagascar. In Encyclopédie Universalis. Tome 10. Édition 1973. p.277] despite an increase in its value from 6.3 billion Malagasy francs in 1960 to 33.6 billion in 1971, an average annual increase of 15%.[Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.26] It was the processing sector which grew the most:

*In the agricultural area, rice mills, starch manufacturers, oil mills, sugar refineries and canning plants were developed.[

*In the uplands, the cotton factory of ]Antsirabe

Antsirabe () is the third largest city in Madagascar and the capital of the Vakinankaratra region, with a population of 265,018 in 2014.

In Madagascar, Antsirabe is known for its relatively cool climate (like the rest of the central region), it ...

increased its production from 2,100 tonnes to 18,700 tonnes,[Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.25] and the Madagascar paper mill

A paper mill is a factory devoted to making paper from vegetable fibres such as wood pulp, old rags, and other ingredients. Prior to the invention and adoption of the Fourdrinier machine and other types of paper machine that use an endless belt ...

(PAPMAD) was created in Tananarive.[

*A petrol refinery was built in the port city of ]Tamatave

Toamasina (), meaning "like salt" or "salty", unofficially and in French Tamatave, is the capital of the Atsinanana region on the east coast of Madagascar on the Indian Ocean. The city is the chief seaport of the country, situated northeast of it ...

.[

These developments lead to the creation of 300,000 new jobs in industry, increasing the total from 200,000 in 1960 to 500,000 in 1971.][

On the other hand, in the ]primary sector

The primary sector of the economy includes any industry involved in the extraction and production of raw materials, such as farming, logging, fishing, forestry and mining.

The primary sector tends to make up a larger portion of the economy ...

, private sector initiatives were less numerous.[ There were several reasons for this: issues with the soil and climate, as well as transport and commercialisation problems.][Charles Cadoux. Madagascar. In ''Encyclopédie Universalis''. Tome 10. 1973 Edition. p.277] The communication network remained inadequate. Under Tsiranana there were only three railway routes: Tananarive-Tamatave (with a branch leading to Lake Alaotra

Lake Alaotra ( mg, farihin' Alaotra, ; french: Lac Alaotra) is the largest lake in Madagascar, located in Alaotra-Mangoro Region and on the island's northern central plateau. Its basin is composed of shallow freshwater lakes and marshes surrounded ...

), Tananarive-Antsirabe, and Fianarantsoa

Fianarantsoa is a city (commune urbaine) in south central Madagascar, and is the capital of Haute Matsiatra Region.

History

It was built in the early 19th century by the Merina as the administrative capital for the newly conquered Betsileo kin ...

-Manakara

Manakara is a city in Madagascar.

It is the capital Fitovinany Region and of the district of Manakara Atsimo.

The city is located at the east coast near the mouth of the Manakara River and has a small port.

The bridge over the Manakara River ...

.[ The 3,800 km of roads (2,560 km of which were ]asphalt

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term ...

ed) mostly served to link Tananarive to the port cities. Vast regions remained isolated.[ The ports, although poorly equipped, enabled some degree of ]cabotage

Cabotage () is the transport of goods or passengers between two places in the same country. It originally applied to shipping along coastal routes, port to port, but now applies to aviation, railways, and road transport as well.

Cabotage rights ar ...

.[

Malagasy agriculture thus remained essentially subsistence based under Tsiranana, except in certain sectors,][ like the production of unshelled rice which grew from 1,200,000 tonnes in 1960 to 1,870,000 tonnes in 1971, an increase of 50%.][ Self-sufficiency in terms of food was nearly achieved.][Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.24] Each year, between 15,000 and 20,000 tonnes of de luxe rice was exported.[ Madagascar also increased its export of coffee from 56,000 tonnes in 1962 to 73,000 tonnes in 1971 ad its export of bananas from 15,000 to 20,000 tonnes per year.][ Finally, under Tsiranana, the island was the world's primary producer of vanilla.][

Yet dramatic economic growth did not occur. The GNP per capita only increased by US$30 in the nine years after 1960, reaching only US$131 in 1969.][ Imports increased, reaching US$28 million in 1969, increasing the trade deficit to US$11 million.][ A couple of power plants provided electricity to only Tananarive, Tamatave and Fianarantsoa.][ The annual energy consumption per person only increased a little from 38 kg (carbon equivalent) to 61 kg between 1960 and 1969.][

This situation was not catastrophic.][ ]Inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

increased annually by 4.1% between 1965 and 1973.[ The ]external debt

A country's gross external debt (or foreign debt) is the liabilities that are owed to nonresidents by residents. The debtors can be governments, corporations or citizens. External debt may be denominated in domestic or foreign currency. It inclu ...

was small. The service of the debt in 1970 represented only 0.8% of GNP.[ The ]currency reserves

Foreign exchange reserves (also called forex reserves or FX reserves) are cash and other reserve assets such as gold held by a central bank or other monetary authority that are primarily available to balance payments of the country, influence ...

were not negligible - in 1970 they contained 270 million franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

s.[ The ]budget deficit

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit; the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budget ...

was kept within very strict limits.[ The low population freed the island from the danger of famine and the bovine population (very important for subsistence farmers) was estimated at 9 million.][ The leader of the opposition, Marxist pastor Andriamanjato declared that he was "80% in agreement" with the economic policy pursued by Tsiranana.][

]

Privileged partnership with France

During Tsiranana's presidency, the links between Madagascar and France remained extremely strong in all areas. Tsiranana assured those French people

The French people (french: Français) are an ethnic group and nation primarily located in Western Europe that share a common French culture, history, and language, identified with the country of France.

The French people, especially the na ...

living on the island that they formed Madagascar's 19th tribe.[Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.22]

Tsiranana was surrounded by an entourage of French technical advisors, the "vazahas",[Philibert Tsiranana 2e partie (1er juin 2007), Émission de RFI « Archives d'Afrique »] of whom the most important were:

* Paul Roulleau, who headed the cabinet and was involved in all economic affairs.[

* General Bocchino, ]Chief of defence

The chief of defence (or head of defence) is the highest ranked commissioned officer of a nation's armed forces. The acronym CHOD is in common use within NATO and the European Union as a generic term for the highest national military position wit ...

, who in practice performed the functions of Minister of Defence.[

] French officials in Madagascar continued to ensure the operation of the administrative machinery until 1963/1964.

French officials in Madagascar continued to ensure the operation of the administrative machinery until 1963/1964.[Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.31] After that, they were reduced to an advisory role and, with rare exceptions, they lost all influence.[ In their concern for the renewal of their contracts, some of these adopted an irresponsible and complaisant attitude towards their ministers, directors, or department heads.][

The security of the state was placed under the responsibility of French troops, who continued to occupy various strategic bases on the island. French parachutists were based at the Ivato-Tananarive international airport, while the Commander in Chief of the French military forces in the Indian Ocean was based at Diego Suarex harbour at the north end of the country.][Patrick Rajoelina. ''op. cit.'' p.35] When the French government decided to withdraw nearly 1,200 troops from Madagascar in January 1964,[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.208] Tsiranana took offence:

From independence, Madagascar was in the franc-zone.[ Membership of this zone allowed Madagascar to assure foreign currency cover for recognised priority imports, to provide a guaranteed market for certain agricultural products (bananas, meat, sugar, de luxe rice, pepper etc.) at above average prices, to secure private investment, and to maintain a certain rigour in the state budget.][Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.29] In 1960, 73% of exports went to the franc-zone, with France among the main trade partners, supplying 10 billion CFA francs to the Malagasy economy.[

France provided a particularly important source of aid to the sum of 400 million dollars, for twelve years.][Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.30] This aid, in all its forms, was equal to two thirds of the Malagasy national budget until 1964.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.206] Further, thanks to the conventions of association with the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lis ...

(EEC), the advantages arising from the market organisations of the franc-zone, the Aid Fund, and the French Cooperation (FAC), were transferred to the community's level.[ Madagascar was also able to benefit from appreciable favoured tariff status and received around 160 million dollars in aid from the EEC between 1965 and 1971.][

Beyond this strong financial dependency, Tsiranana's Madagascar seemed to preserve the preponderant French role in the economy.][Ferdinand Deleris. ''op. cit.'' p.27] Banks, insurance agencies, high scale commerce, industry and some agricultural production (sugar, sisal

Sisal (, ) (''Agave sisalana'') is a species of flowering plant native to southern Mexico, but widely cultivated and naturalized in many other countries. It yields a stiff fibre used in making rope and various other products. The term sisal may ...

, tobacco, cotton, etc.) remained under the control of the foreign minority.[

]

Foreign Policy

This partnership with France gave the impression that Madagascar was completely committed to the old metropole and voluntarily accepted an invasive

This partnership with France gave the impression that Madagascar was completely committed to the old metropole and voluntarily accepted an invasive neo-colonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, g ...

.[ In fact, by this French policy, Tsiranana simply tried to extract the maximum amount of profit for his country in the face of the insurmountable constraints against seeking other ways.][ In order to free himself from French economic oversight, Tsiranana made diplomatic and commercial links with other states sharing his ideology:][

* ]West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

, which imported around 585 million CFA francs of Malagasy products in 1960.[ West Germany signed an economic collaboration treaty with Madagascar on 21 September 1962, which granted Madagascar 1.5 billion CFA francs of credit.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.167] Further, the Philibert Tsiranana Foundation, instituted in 1965 and charged with forming political and administrative recruits for the PSD, was funded by the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been ...

.[

* The ]United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, which imported around 2 billion CFA francs of Malagasy products in 1960,[ granted 850 million CFAfrancs between 1961 and 1964.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.221]

* Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

, which sought to continue relations after his visit to the island in April 1962.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.147]

An attempt at a commercial overture towards the Communist bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

and southern Africa including Malawi

Malawi (; or aláwi Tumbuka: ''Malaŵi''), officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northe ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

.[ But this eclecticism provoked some controversy, particularly when the results were not visible.][

] Tsiranana advocated moderation and realism in international organs like the

Tsiranana advocated moderation and realism in international organs like the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

, the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

(OAU), and the African and Malagasy Union

, native_name_lang=fr

, image = File:Flag_of_African_and_Malagasy_Union.svg

, image_border =

, size =

, caption = Flag

, map = AfricanMalagasyUnionMembers.png

, msize =

, mcaption =

, abbreviation =

, m ...

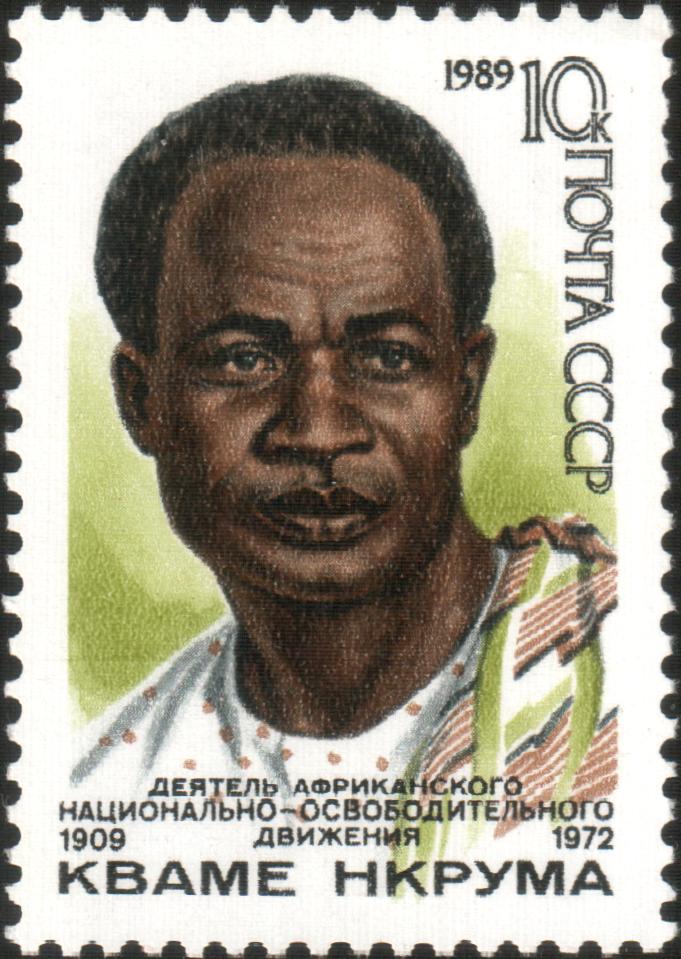

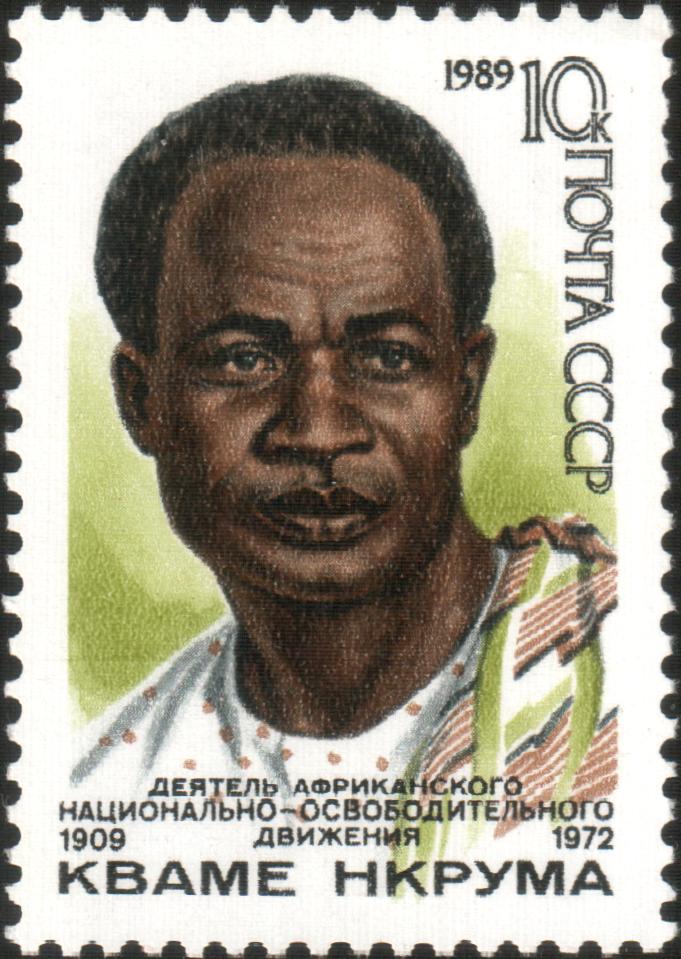

(AMU).[ He was opposed to the Panafricanist ideas proposed by ]Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An ...

. For his part, he undertook to cooperate with Africa in the economic sphere, but not in the political arena.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.122] During the second summit of the OAU in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

on 19 July 1964, he declared that the organisation was weakened by three illnesses:

He served as mediator from 6–13 March 1961, during a round-table organised by him in Tananarive to permit the various belligerents in the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

to work out a solution to the conflict.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.136] It was decided to transform the Republic of Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

into a confederation, led by Joseph Kasavubu

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, ( – 24 March 1969) was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic of the Congo) from 1960 until 1965.

A member of the Kon ...

.[ But this mediation was in vain, since the conflict soon resumed.][

If Tsiranana seemed moderate, he was nevertheless deeply anti-communist. He did not hesitate to boycott the third conference of the OAU held at ]Accra

Accra (; tw, Nkran; dag, Ankara; gaa, Ga or ''Gaga'') is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , ...

in October 1965 by the radical President of Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

, Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An ...

.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.328] On 5 November 1965, he attacked the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and affirmed that "coups d'etat always bear the traces of Communist China."[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.331] A little later, on 5 January 1966, after the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état

The Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état was a coup d'état staged by Jean-Bédel Bokassa, commander-in-chief of the Central African Republic (CAR) army, and his officers against the government of President David Dacko on 31 December 1965 and 1 Jan ...

in the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

, he went so far as to praise those who carried out the coup:

The decline and fall of the regime (1967-1972)

From 1967, Tsiranana faced mounting criticism. In the first place, it was clear that the structures put in place by "Malagasy Socialism" to develop the country were not having a major macro-economic effect.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome II. p.21] Further, some measures were unpopular, like the ban on the mini-skirt

A miniskirt (sometimes hyphenated as mini-skirt, separated as mini skirt, or sometimes shortened to simply mini) is a skirt with its hemline well above the knees, generally at mid-thigh level, normally no longer than below the buttocks; and a ...

, which was an obstacle to tourism.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome II. p.32]

In November 1968, a document entitled ''Dix années de République'' (Ten Years of the Republic) was published, which had been drafted by a French technical assistant and a Malagasy and which harshly criticised the leaders of PSD, denouncing some financial scandals which the authors attributed to members of the government.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome II. p.55] An investigation was initiated which culminated in the imprisonment of one of the authors.[ Intellectuals were provoked by this affair.][ Finally, the inevitable wear of the regime over time created a subdued but clear undercurrent of opposition.

]

Challenges to the Francophile policy

Between 1960 and 1972, both Merina and coastal Malagasy were largely convinced that although political independence had been realised, economic independence had not been.[ The French controlled the economy and held almost all the technical posts of the Malagasy senior civil service.][ The revision of the Franco-Malagasy accords and significant nationalisation were seen by many Malagasy as offering a way to free up between five and ten thousand jobs, then held by Europeans, which could be replaced by locals.][

Another centre of opposition was Madagascar's membership of the franc-zone. Contemporary opinion had it that as long as Madagascar remained in this zone, only subsidiaries and branches of French banks would do business in Madagascar.][ These banks were unwilling to take any risk to support the establishment of Malagasy enterprises, using insufficient guarantees as their excuse.][ In addition, the Malagasy had only limited access to credit, compared to the French, who received priority.][ Finally, membership of the franc-zone involved regular restrictions on the free movement of goods.][

In 1963 at the 8th PSD congress, some leaders of the governing party raised the possibility of revising the Franco-Malagasy accords.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.203] At the 11th congress in 1967, their revision was practically demanded.[ André Resampa, the strongman of the regime, was the proponent of this.][André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome II. p.22]

Tsiranana's illness

Tsiranana suffered from cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, hea ...

. In June 1966, his health degraded sharply; he was forced to spend two and half months convalescing,[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.353] and to spend three weeks in France receiving treatment.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.357] Officially, Tsiranana's sickness was simply one brought on by fatigue.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome I. p.358] Subsequently, Tsiranana frequently visited Paris for examinations and the French Riviera

The French Riviera (known in French as the ; oc, Còsta d'Azur ; literal translation " Azure Coast") is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France. There is no official boundary, but it is usually considered to extend from ...

for rest.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome II. p.47] Despite this, his health did not improve.[André Saura. ''op. cit.'' Tome II. p.64]