Peter Cooper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791April 4, 1883) was an American

Having been convinced that the proposed

Having been convinced that the proposed

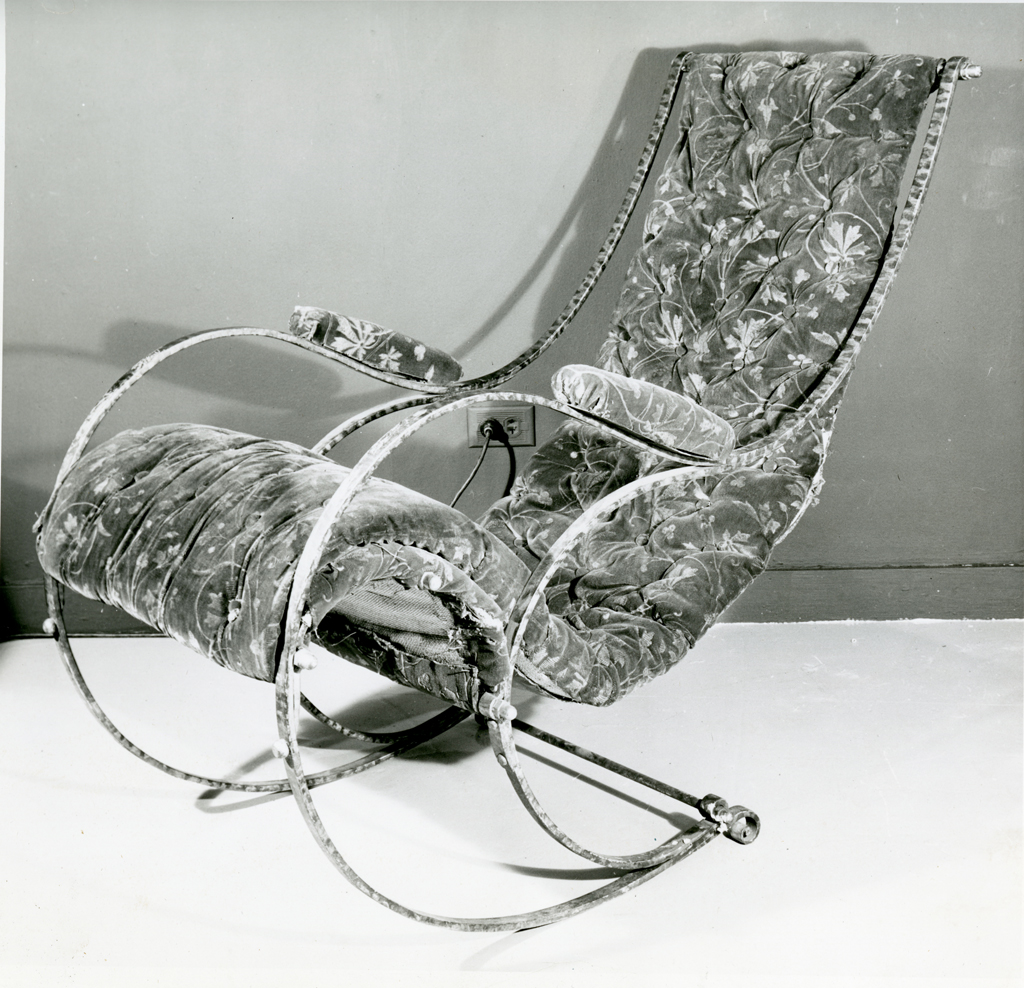

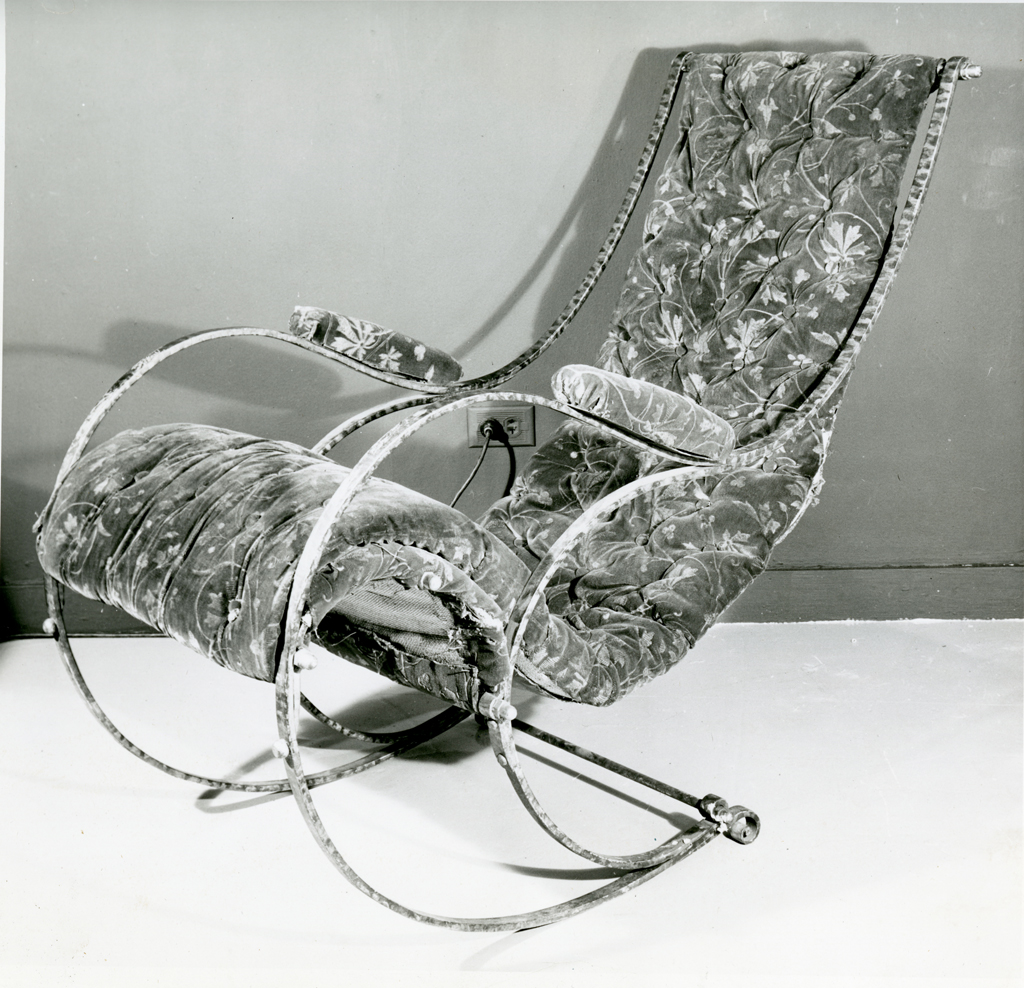

During the 1830's Cooper designed the first steel chair in America, which was a rocking chair. Cooper produced a functional, minimalist design radically different from the Victorian heavily decorated, ostentatious style of the time. Most rocking chairs had separate rockers fixed to regular chair legs, but Cooper's chair used the curve of its frame to ensure the rocking motion. Cooper's chair was made of steel or wrought iron with upholstery slung across the frame. The model was manufactured at R.W. Winfield & Co. in Britain. The firm exhibited examples of the chair at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations (Crystal Palace Exhibition) in 1851 and the Great London Exposition of 1862.

During the 1830's Cooper designed the first steel chair in America, which was a rocking chair. Cooper produced a functional, minimalist design radically different from the Victorian heavily decorated, ostentatious style of the time. Most rocking chairs had separate rockers fixed to regular chair legs, but Cooper's chair used the curve of its frame to ensure the rocking motion. Cooper's chair was made of steel or wrought iron with upholstery slung across the frame. The model was manufactured at R.W. Winfield & Co. in Britain. The firm exhibited examples of the chair at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations (Crystal Palace Exhibition) in 1851 and the Great London Exposition of 1862.

In 1813, Cooper married Sarah Bedell (1793–1869). Of their six children, only two survived past the age of four years: a son,

In 1813, Cooper married Sarah Bedell (1793–1869). Of their six children, only two survived past the age of four years: a son,

online

*

online

*

Mechanic to Millionaire: The Peter Cooper Story, as seen on PBS Jan. 2, 2011

by Nathan C. Walker in the ''Dictionary of Unitarian Universalist Biography''

Facts About Peter Cooper and The Cooper Union

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20030708024526/http://www.ringwoodmanor.com/peo/ch/pc/pc.htm Brief biography*

Extensive Information about Peter CooperImages of Peter Cooper's Autobiography Peter Cooper's Dictated Autobiography''The death of slavery'' by Peter Cooper at archive.org

The Hero of Our Day!

to Peter Cooper, "America's Great Philanthropist". {{DEFAULTSORT:Cooper, Peter 1791 births 1883 deaths 19th-century American businesspeople 19th-century American politicians 19th-century Christian universalists American abolitionists American Christian universalists 19th-century American inventors American people of Dutch descent American people of English descent American people of French descent American railroad pioneers Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery Greenback Party presidential nominees Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Locomotive builders and designers Native Americans' rights activists New York (state) Greenbacks New York City Council members People from Hempstead (village), New York Candidates in the 1876 United States presidential election University and college founders People from Gramercy Park Presidents of Cooper Union

industrialist

A business magnate, also known as a tycoon, is a person who has achieved immense wealth through the ownership of multiple lines of enterprise. The term characteristically refers to a powerful entrepreneur or investor who controls, through per ...

, inventor, philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

, and politician. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, oil or, rarely, wood) to heat water in the loco ...

, the '' Tom Thumb'', founded the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, served as its first president, and stood for election as the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

's candidate in the 1876 presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. It was one of the most contentious ...

. Cooper was 85 years old at the time, making him the oldest person to ever be nominated for president.

Cooper began tinkering at a young age while working in various positions in New York City. He purchased a glue factory in 1821 and used that factory's profits to found the Canton Iron Works, where he earned even larger profits by assembling the ''Tom Thumb''. Cooper's success as a businessman and inventor continued over the ensuing decades, and he became the first mill operator to successfully use anthracite coal

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the hig ...

to puddle iron. He also developed numerous patents for products such as gelatin

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

and participated in the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is now an obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and data a ...

.

During the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

, Cooper became an ardent critic of the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

and the debt-based monetary system of bank currency, advocating instead for government-issued banknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

s. Cooper was nominated for president at the 1876 Greenback National Convention, and the Greenback ticket of Cooper and Samuel Fenton Cary

Samuel Fenton Cary (February 18, 1814 – September 29, 1900) was an American politician who was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio and significant temperance movement leader in the 19th century. Cary became well known natio ...

won just under one percent of the popular vote in the 1876 general election. His son Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

and his son-in-law Abram Hewitt

Abram Stevens Hewitt (July 31, 1822January 18, 1903) was an American politician, educator, ironmaking industrialist, and lawyer who was mayor of New York City for two years from 1887–1888. He also twice served as a U.S. Congressman from a ...

, both served as Mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

.

Early years

Peter Cooper was born inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

and Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

descent,Burrows & Wallace p.563 the fifth child of John Cooper, a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

hatmaker from Newburgh, New York

Newburgh is a city in the U.S. state of New York, within Orange County. With a population of 28,856 as of the 2020 census, it is a principal city of the Poughkeepsie–Newburgh–Middletown metropolitan area. Located north of New York City, a ...

He worked as a coachmaker's apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

, cabinet maker

A cabinet is a case or cupboard with shelves and/or drawers for storing or displaying items. Some cabinets are stand alone while others are built in to a wall or are attached to it like a medicine cabinet. Cabinets are typically made of wood (so ...

, hatmaker, brewer and grocer, and was throughout a tinkerer: he developed a cloth-shearing machine which he attempted to sell, as well as an endless chain he intended to be used to pull barges and boats on the newly completed Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing ...

(which was routed west to east across upper New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. sta ...

from Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also ha ...

to the upper Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

) which its chief supporter, the Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor h ...

, De Witt Clinton

DeWitt Clinton (March 2, 1769February 11, 1828) was an American politician and naturalist. He served as a United States senator, as the mayor of New York City, and as the seventh governor of New York. In this last capacity, he was largely resp ...

approved of, but which Cooper was unable to sell.

In 1821, Cooper purchased a glue factory on Sunfish Pond on east side Manhattan Island

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the List of co ...

for $2,000 at Kips Bay, where he had access to raw materials from the nearby slaughterhouse

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is no ...

s, and ran it as a successful business for many years, producing a profit of $10,000 (equivalent to roughly $200,000 in 21st century value today) within 2 years, developing new ways to produce glues and cements, gelatin

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

, isinglass

Isinglass () is a substance obtained from the dried swim bladders of fish. It is a form of collagen used mainly for the clarification or fining of some beer and wine. It can also be cooked into a paste for specialised gluing purposes.

...

and other products, and becoming the city's premier provider to tanners (leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and hog ...

), manufacturers of paint

Paint is any pigmented liquid, liquefiable, or solid mastic composition that, after application to a substrate in a thin layer, converts to a solid film. It is most commonly used to protect, color, or provide texture. Paint can be made in many ...

s, and dry-goods

Dry goods is a historic term describing the type of product line a store carries, which differs by region. The term comes from the textile trade, and the shops appear to have spread with the mercantile trade across the British Empire (and forme ...

merchants.Burrows & Wallace p.564 The effluent from his successful factory eventually polluted the pond so much that in 1839 it had to be drained and backfilled for eventual building construction.

Business career

Having been convinced that the proposed

Having been convinced that the proposed Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

would drive up prices for land in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

, Cooper used his profits to buy of land there in 1828 and began to develop them, draining swampland and flattening hills, during which he discovered iron ore on his property. Seeing the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as a natural market for iron rails to be made from his ore, he founded the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, and when the railroad developed technical problems, he put together the '' Tom Thumb'' steam locomotive for them in 1829 from various old parts, including musket barrels, and some small-scale steam engines he had fiddled with back in New York. The engine was a rousing success, prompting investors to buy stock in B&O, which enabled the company to buy Cooper's iron rails, making him what would be his first fortune.

Cooper began operating an iron rolling mill

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

in New York beginning in 1836, where he was the first to successfully use anthracite coal

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the hig ...

to puddle iron. Cooper later moved the mill to Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. It was the capital of the United States from November 1 to December 24, 1784.Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, before ...

to be closer to the sources of the raw materials the works needed. His son and son-in-law, Edward Cooper and Abram S. Hewitt, later expanded the Trenton facility into a giant complex employing 2,000 people, in which iron was taken from raw material to finished product.

Cooper also operated a successful glue factory in Gowanda, New York

Gowanda is a village in western New York, United States. It lies partly in Erie County and partly in Cattaraugus County. The population was 2,512 at the 2020 census. The name is derived from a local Seneca language term meaning "almost surrou ...

that produced glue for decades.Kirby, C.D. (1976). ''The Early History of Gowanda and The Beautiful Land of the Cattaraugus''. Gowanda, NY: Niagara Frontier Publishing Company, Inc./Gowanda Area Bi-Centennial Committee, Inc. A glue factory was originally started in association with the Gaensslen Tannery, there, in 1874, though the first construction of the glue factory's plant, originally owned by Richard Wilhelm and known as the Eastern Tanners Glue Company, began on May 5, 1904. Gowanda, therefore, was known as America's glue capital.

Cooper owned a number of patents for his inventions, including some for the manufacture of gelatin

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

, and he developed standards for its production. The patents were later sold to a cough syrup manufacturer who developed a pre-packaged form which his wife named "Jell-O

Jell-O is an American brand offering a variety of powdered gelatin dessert (fruit-flavored gels/jellies), pudding, and no-bake cream pie mixes. The original gelatin dessert ( genericized as jello) is the signature of the brand. "Jell-O" is ...

".

Cooper later invested in real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

and insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

, and became one of the richest men in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.Burrows & Wallace p.725 Despite this, he lived relatively simply in an age when the rich were indulging in more and more luxury. He dressed in simple, plain clothes, and limited his household to only two servants; when his wife bought an expensive and elaborate carriage, he returned it for a more sedate and cheaper one. Cooper remained in his home at Fourth Avenue and 28th Street even after the New York and Harlem Railroad

The New York and Harlem Railroad (now the Metro-North Railroad's Harlem Line) was one of the first railroads in the United States, and was the world's first street railway. Designed by John Stephenson, it was opened in stages between 1832 and ...

established freight yards where cattle cars were parked practically outside his front door, although he did move to the more genteel Gramercy Park

Gramercy ParkSometimes misspelled as Grammercy () is the name of both a small, fenced-in private park and the surrounding neighborhood that is referred to also as Gramercy, in the New York City borough of Manhattan in New York, United States.

...

development in 1850.

In 1854, Cooper was one of five men who met at the house of Cyrus West Field

Cyrus West Field (November 30, 1819July 12, 1892) was an American businessman and financier who, along with other entrepreneurs, created the Atlantic Telegraph Company and laid the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1858.

Early ...

in Gramercy Park to form the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company

The New York, Newfoundland & London Telegraph Company was a company in a series of conglomerations of several companies that eventually laid the first Trans-Atlantic cable.

In 1854 British engineer Charles Bright met an American, Cyrus Field, ...

, and, in 1855, the American Telegraph Company

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

, which bought up competitors and established extensive control over the expanding American network on the Atlantic Coast and in some Gulf coast states. He was among those supervising the laying of the first Transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is now an obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and data a ...

in 1858.

Invention of first steel rocking chair (1830's)

During the 1830's Cooper designed the first steel chair in America, which was a rocking chair. Cooper produced a functional, minimalist design radically different from the Victorian heavily decorated, ostentatious style of the time. Most rocking chairs had separate rockers fixed to regular chair legs, but Cooper's chair used the curve of its frame to ensure the rocking motion. Cooper's chair was made of steel or wrought iron with upholstery slung across the frame. The model was manufactured at R.W. Winfield & Co. in Britain. The firm exhibited examples of the chair at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations (Crystal Palace Exhibition) in 1851 and the Great London Exposition of 1862.

During the 1830's Cooper designed the first steel chair in America, which was a rocking chair. Cooper produced a functional, minimalist design radically different from the Victorian heavily decorated, ostentatious style of the time. Most rocking chairs had separate rockers fixed to regular chair legs, but Cooper's chair used the curve of its frame to ensure the rocking motion. Cooper's chair was made of steel or wrought iron with upholstery slung across the frame. The model was manufactured at R.W. Winfield & Co. in Britain. The firm exhibited examples of the chair at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations (Crystal Palace Exhibition) in 1851 and the Great London Exposition of 1862.

Political views and career

In 1840, Cooper became analderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members ...

of New York City.

Prior to the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, Cooper was active in the anti-slavery movement and promoted the application of Christian concepts to solve social injustice. He was a strong supporter of the Union cause during the war and an advocate of the government issue of paper money.

Influenced by the writings of Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child ( Francis; February 11, 1802October 20, 1880) was an American abolitionist, women's rights activist, Native American rights activist, novelist, journalist, and opponent of American expansionism.

Her journals, both fiction an ...

, Cooper became involved in the Indian reform movement, organizing the privately funded United States Indian Commission. This organization, whose members included William E. Dodge

William Earl Dodge Sr. (September 4, 1805 – February 9, 1883) was an American businessman, politician, and activist. He was referred to as one of the "Merchant Princes" of Wall Street in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Dodg ...

and Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery trial. His r ...

, was dedicated to the protection and elevation of Native Americans in the United States and the elimination of warfare in the western territories.

Cooper's efforts led to the formation of the Board of Indian Commissioners The Board of Indian Commissioners was a committee that advised the federal government of the United States on Native American policy and inspected supplies delivered to Indian agencies to ensure the fulfillment of government treaty obligations.

...

, which oversaw Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

's Peace Policy. Between 1870 and 1875, Cooper sponsored Indian delegations to Washington, D.C., New York City, and other Eastern cities. These delegations met with Indian rights advocates and addressed the public on United States Indian policy. Speakers included: Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

, Little Raven, and Alfred B. Meacham and a delegation of Modoc and Klamath Indians.

Cooper was an ardent critic of the gold standard and the debt-based monetary system of bank currency. Throughout the depression from 1873 to 1878, he said that usury was the foremost political problem of the day. He strongly advocated a credit-based, Government-issued currency of United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the U.S. Having been current for 109 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper money. They were k ...

s. In 1883 his addresses, letters and articles on public affairs were compiled into a book, ''Ideas for a Science of Good Government.''

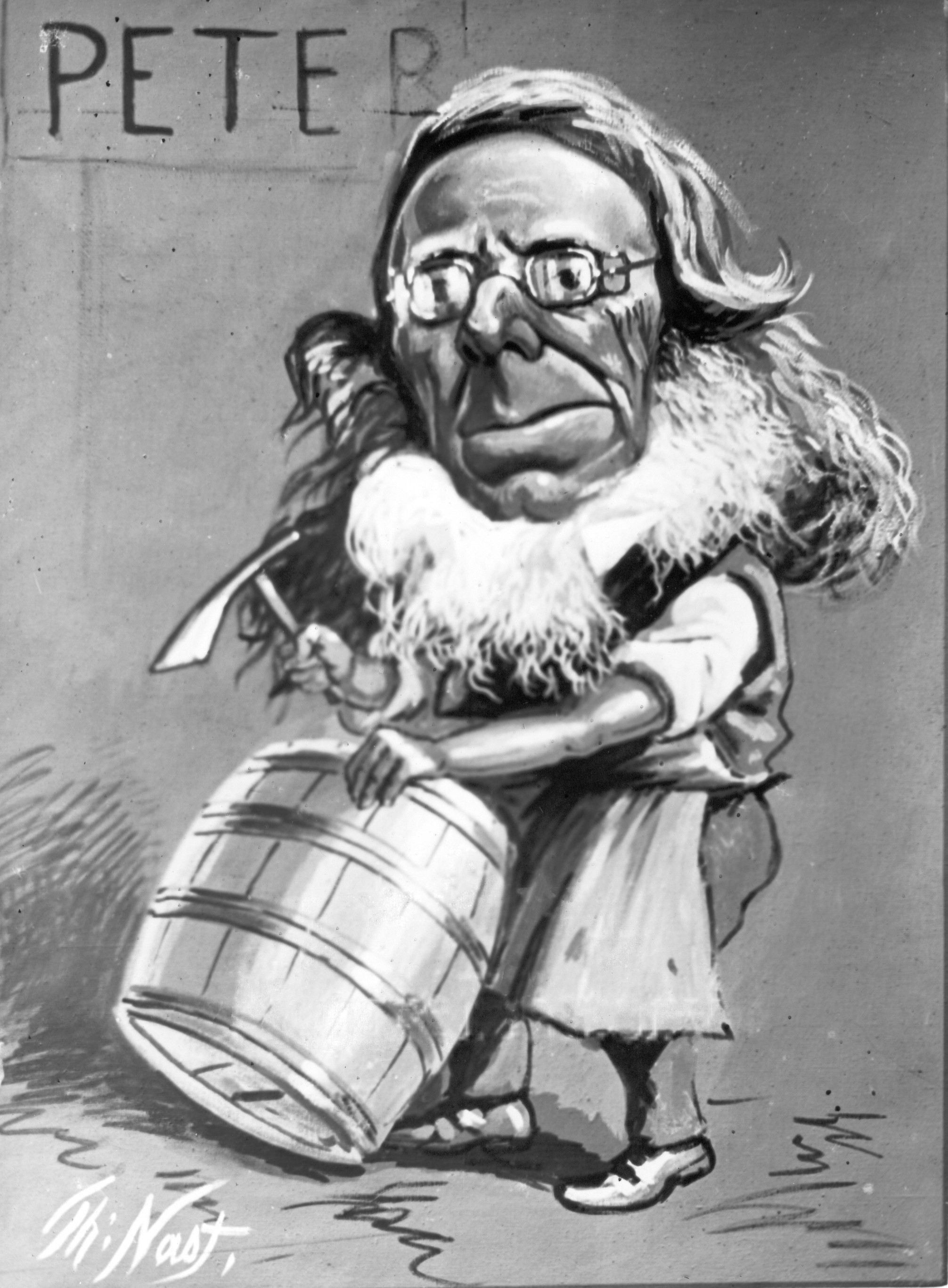

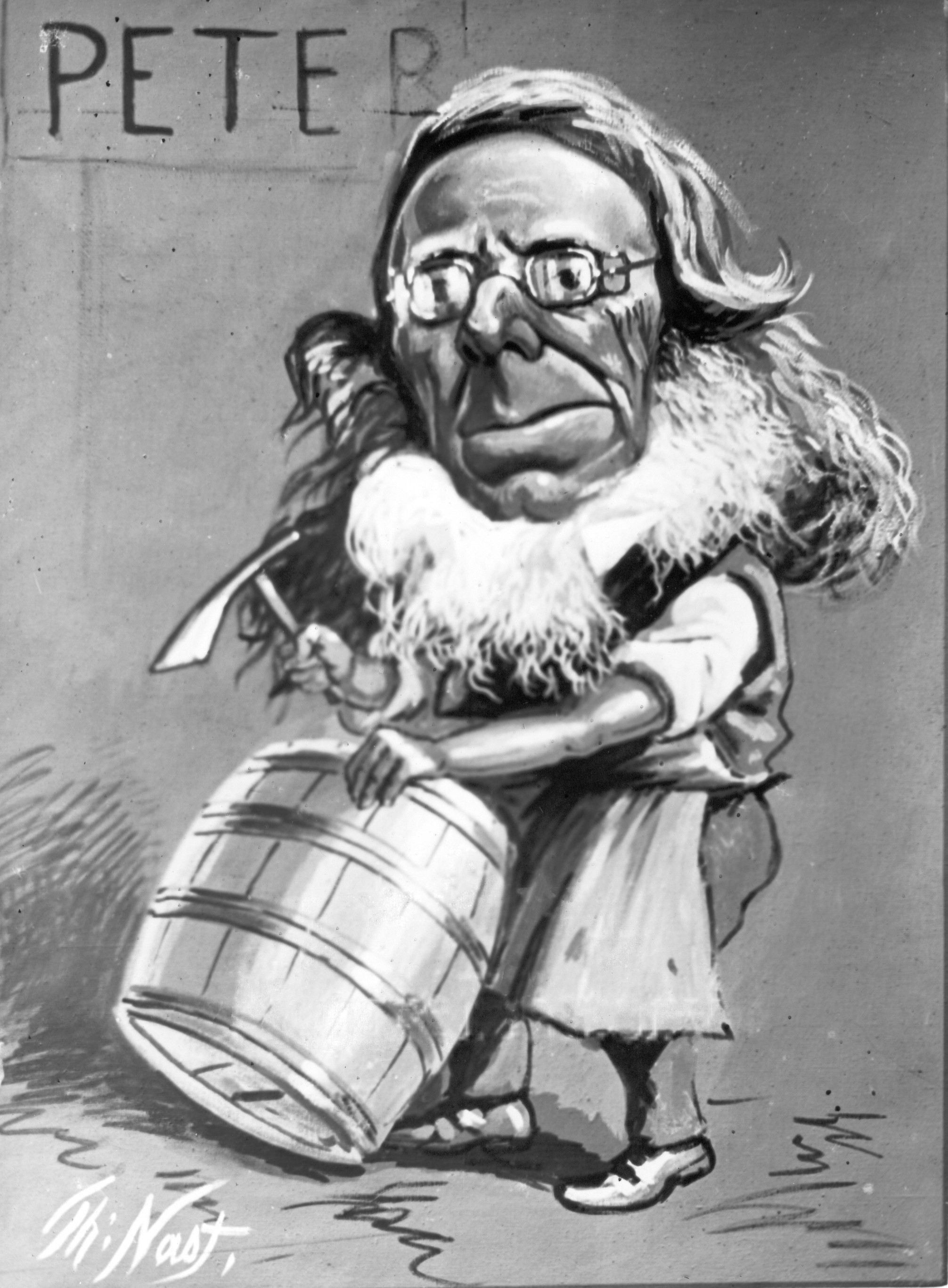

Presidential candidacy

Cooper was encouraged to run in the1876 presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. It was one of the most contentious ...

for the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

without any hope of being elected. His running mate was Samuel Fenton Cary

Samuel Fenton Cary (February 18, 1814 – September 29, 1900) was an American politician who was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio and significant temperance movement leader in the 19th century. Cary became well known natio ...

. The campaign cost more than $25,000. At the age of 85 years, Cooper is the oldest person ever nominated by any political party for President of the United States. The election was won by Rutherford Birchard Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

of the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

. Cooper was surpassed by another unsuccessful candidate, Samuel J. Tilden of the Democratic Party.

A political family

In 1813, Cooper married Sarah Bedell (1793–1869). Of their six children, only two survived past the age of four years: a son,

In 1813, Cooper married Sarah Bedell (1793–1869). Of their six children, only two survived past the age of four years: a son, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

and a daughter, Sarah Amelia. Edward served as Mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

, as would the husband of Sarah Amelia, Abram S. Hewitt, a man also heavily involved in inventions and industrialization.

Peter Cooper's granddaughters, Sarah Cooper Hewitt, Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Amy Hewitt Green founded the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum is a design museum housed within the Andrew Carnegie Mansion in Manhattan, New York City, along the Upper East Side's Museum Mile. It is one of 19 museums that fall under the wing of the Smithsonian Inst ...

, then named the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, in 1895. It was originally part of Cooper Union, but since 1967 has been a unit of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

.

Religious views

Cooper was a Unitarian who regularly attended the services of Henry Whitney Bellows at the Church of All Souls (New York), and his views were Universalistic andnon-sectarian

Nonsectarian institutions are secular institutions or other organizations not affiliated with or restricted to a particular religious group.

Academic sphere

Examples of US universities that identify themselves as being nonsectarian include Adelp ...

. In 1873 he wrote:

I look to see the day when the teachers of Christianity will rise above all the cramping powers and conflicting creeds and systems of human device, when they will beseech mankind by all the mercies of God to be reconciled to the government of love, the only government that can ever bring the kingdom of heaven into the hearts of mankind either here or hereafter.Cooke, George Willis

''Unitarianism in America: A History of Its Origin and Development, v.4''"> ''Unitarianism in America: A History of Its Origin and Development, v.4''

Boston: American Unitarian Association, 1902. pp.408-09

Cooper Union

Cooper had for many years held an interest in adult education: he had served as head of the Public School Society, a private organization which ran New York City's free schools using city money, when it began evening classes in 1848.Burrows & Wallace p.782 Cooper conceived of the idea of having a free institute in New York, similar to theÉcole Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

(Polytechnical School) in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, which would offer free practical education to adults in the mechanical arts and science, to help prepare young men and women of the working classes for success in business.

In 1853, he broke ground for the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a private college in New York, completing the building in 1859 at the cost of $600,000. Cooper Union offered open-admission night classes available to men and women alike, and attracted 2,000 responses to its initial offering, although 600 later dropped out. The classes were non-sectarian, and women were treated equally with men, although 95% of the students were male. Cooper started a Women's School of Design, which offered daytime courses in engraving, lithography, painting on china and drawing.

The new institution soon became an important part of the community. The Great Hall

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, castle or a large manor house or hall house in the Middle Ages, and continued to be built in the country houses of the 16th and early 17th centuries, although by then the family used the gr ...

was a place where the pressing civic controversies of the day could be debated, and, unusually, radical views were not excluded. In addition, the Union's library, unlike the nearby Astor

Astor may refer to:

People

* Astor (surname)

* Astor family, a wealthy 18th-century American family who became prominent in 20th-century British politics

* Astor Bennett, a character in the Showtime television series ''Dexter''

* Ástor Piazzo ...

, Mercantile

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

and New York Society Libraries, was open until 10:00 at night, so that working people could make use of them after work hours.

Today Cooper Union is recognized as one of the leading American colleges in the fields of architecture, engineering, and art. Carrying on Peter Cooper's belief that college education should be free, the Cooper Union awarded all its students with a full scholarship until fall 2014. The college is currently implementing a plan to restore full-tuition scholarships for all its undergraduate students by 2029.

Philanthropy

In 1851, Cooper was one of the founders ofChildren's Village

The Children's Village, formerly the New York Juvenile Asylum, is a private, non-profit residential treatment facility and school for troubled children. It was founded in 1851 by 24 citizens of New York (state), New York who were concerned about ...

, originally an orphanage called "New York Juvenile Asylum", one of the oldest non-profit organizations in the United States.

Death and legacy

Cooper died on April 4, 1883 at the age of 92 and is buried inGreen-Wood Cemetery

Green-Wood Cemetery is a cemetery in the western portion of Brooklyn, New York City. The cemetery is located between South Slope/ Greenwood Heights, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Borough Park, Kensington, and Sunset Park, and lies several blo ...

in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

Aside from Cooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique ...

, the Peter Cooper Village

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

apartment complex in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

; the Peter Cooper Elementary School in Ringwood, New Jersey

Ringwood is a borough in Passaic County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the borough's population was 11,735, a decline of 493 (−4.0%) from the 2010 census count of 12,228,Peter Cooper Station

The United States Post Office Cooper Station, located at 93 Fourth Avenue, on the corner of East 11th Street in Manhattan, New York City, was built in 1937, and was designed by consulting architect William Dewey Foster in the Art Moderne style ...

post office; Cooper Park

Cooper Park is an urban park in Brooklyn, New York City, between Maspeth Avenue, Sharon Street, Olive Street, and Morgan Avenue in East Williamsburg. It was established in 1895 and covers .

Cooper Park was once the site of an old glue factory ...

in Brooklyn, Cooper Square

__NOTOC__

Cooper Square is a junction of streets in Lower Manhattan in New York City located at the confluence of the neighborhoods of Bowery to the south, NoHo to the west and southwest, Greenwich Village to the west and northwest, the East V ...

in Manhattan, and Cooper Square in Hempstead, New York

The Town of Hempstead (also known historically as South Hempstead) is the largest of the three towns in Nassau County (alongside North Hempstead and Oyster Bay) in the U.S. state of New York. It occupies the southwestern part of the county, o ...

are named in his honor.

References

Notes Bibliography * Mack, Edward C. ''Peter Cooper, citizen of New York'' (1949online

*

online

*

External links

Mechanic to Millionaire: The Peter Cooper Story, as seen on PBS Jan. 2, 2011

by Nathan C. Walker in the ''Dictionary of Unitarian Universalist Biography''

Facts About Peter Cooper and The Cooper Union

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20030708024526/http://www.ringwoodmanor.com/peo/ch/pc/pc.htm Brief biography*

Extensive Information about Peter Cooper

Popular Culture

*John M. Loretz, Jr. dedicated his songThe Hero of Our Day!

to Peter Cooper, "America's Great Philanthropist". {{DEFAULTSORT:Cooper, Peter 1791 births 1883 deaths 19th-century American businesspeople 19th-century American politicians 19th-century Christian universalists American abolitionists American Christian universalists 19th-century American inventors American people of Dutch descent American people of English descent American people of French descent American railroad pioneers Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery Greenback Party presidential nominees Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Locomotive builders and designers Native Americans' rights activists New York (state) Greenbacks New York City Council members People from Hempstead (village), New York Candidates in the 1876 United States presidential election University and college founders People from Gramercy Park Presidents of Cooper Union