People of Ireland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Irish ( or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an

During the past 33,000 years, Ireland has witnessed different peoples arrive on its shores.

During the past 33,000 years, Ireland has witnessed different peoples arrive on its shores.

One Roman historian records that the Irish people were divided into "sixteen different nations" or tribes.MacManus, p 86 Traditional histories assert that the Romans never attempted to conquer Ireland, although it may have been considered. The Irish were not, however, cut off from Europe; they frequently raided the Roman territories, and also maintained trade links.

Among the most famous people of ancient Irish history are the

One Roman historian records that the Irish people were divided into "sixteen different nations" or tribes.MacManus, p 86 Traditional histories assert that the Romans never attempted to conquer Ireland, although it may have been considered. The Irish were not, however, cut off from Europe; they frequently raided the Roman territories, and also maintained trade links.

Among the most famous people of ancient Irish history are the

The 'traditional' view is that, in the 4th or 5th century, Goidelic language and Gaelic culture was brought to Scotland by settlers from Ireland, who founded the Gaelic kingdom of

The 'traditional' view is that, in the 4th or 5th century, Goidelic language and Gaelic culture was brought to Scotland by settlers from Ireland, who founded the Gaelic kingdom of

Were the Scots Irish?

" in ''Antiquity'' #75 (2001). Dál Riata and the territory of the neighbouring The arrival of the

The arrival of the

A son has the same surname as his father. A female's surname replaces Ó with Ní (reduced from Iníon Uí – "daughter of the grandson of") and Mac with Nic (reduced from Iníon Mhic – "daughter of the son of"); in both cases the following name undergoes lenition. However, if the second part of the surname begins with the letter C or G, it is not lenited after Nic. Thus the daughter of a man named Ó Maolagáin has the surname ''Ní Mhaolagáin'' and the daughter of a man named Mac Gearailt has the surname ''Nic Gearailt''. When anglicised, the name can remain O' or Mac, regardless of gender.

There are a number of Irish surnames derived from Norse personal names, including

A son has the same surname as his father. A female's surname replaces Ó with Ní (reduced from Iníon Uí – "daughter of the grandson of") and Mac with Nic (reduced from Iníon Mhic – "daughter of the son of"); in both cases the following name undergoes lenition. However, if the second part of the surname begins with the letter C or G, it is not lenited after Nic. Thus the daughter of a man named Ó Maolagáin has the surname ''Ní Mhaolagáin'' and the daughter of a man named Mac Gearailt has the surname ''Nic Gearailt''. When anglicised, the name can remain O' or Mac, regardless of gender.

There are a number of Irish surnames derived from Norse personal names, including

The 16th century

The 16th century

The Irish bardic system, along with the

The Irish bardic system, along with the

The Irish diaspora consists of Irish

The Irish diaspora consists of Irish

, discoverireland.com There are also large Irish communities in some mainland European countries, notably in Spain, France and Germany. Between 1585 and 1818, over half a million Irish departed Ireland to serve in the wars on the Continent, in a constant emigration romantically styled the"

There are also large Irish communities in some mainland European countries, notably in Spain, France and Germany. Between 1585 and 1818, over half a million Irish departed Ireland to serve in the wars on the Continent, in a constant emigration romantically styled the"

People of Irish descent are the second largest self-reported ethnic group in the United States, after

People of Irish descent are the second largest self-reported ethnic group in the United States, after  In the mid-19th century, large numbers of Irish immigrants were conscripted into

In the mid-19th century, large numbers of Irish immigrants were conscripted into

Irish Names - origins and meanings

at Library Ireland * * * * * * *

ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

and nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

native to the island of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, who share a common ancestry, history and culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has been continually inhabited for more than 10,000 years (see Prehistoric Ireland

The prehistory of Ireland has been pieced together from Archaeology, archaeological evidence, which has grown at an increasing rate over recent decades. It begins with the first evidence of permanent human residence in Ireland around 10,500 BC ...

). For most of Ireland's recorded history

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world h ...

, the Irish have been primarily a Gaelic people

The Gaels ( ; ; ; ) are an Insular Celtic ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising Irish, Manx, and Scottish Gaelic ...

(see Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

). From the 9th century, small numbers of Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

settled in Ireland, becoming the Norse-Gaels. Anglo-Normans

The Anglo-Normans (, ) were the medieval ruling class in the Kingdom of England following the Norman Conquest. They were primarily a combination of Normans, Bretons, Flemings, French people, Frenchmen, Anglo-Saxons and Celtic Britons.

Afte ...

also conquered parts of Ireland in the 12th century, while England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

's 16th/17th century conquest

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or Coercion (international relations), coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or ...

and colonisation of Ireland brought many English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

and Lowland

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of a ...

Scots to parts of the island, especially the north. Today, Ireland is made up of the Republic of Ireland (officially called Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

) and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

(a part

Part, parts or PART may refer to:

People

*Part (surname)

*Parts (surname)

Arts, entertainment, and media

*Part (music), a single strand or melody or harmony of music within a larger ensemble or a polyphonic musical composition

*Part (bibliograph ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

). The people of Northern Ireland

The people of Northern Ireland are all people born in Northern Ireland and having, at the time of their birth, at least one parent who is a British citizen, an Irish citizen or is otherwise entitled to reside in Northern Ireland without ...

hold various national identities including Irish, British or some combination thereof.

The Irish have their own unique customs, language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

, music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, dance

Dance is an The arts, art form, consisting of sequences of body movements with aesthetic and often Symbol, symbolic value, either improvised or purposefully selected. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoir ...

, sports

Sport is a physical activity or game, often competitive and organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators. The number of participants in ...

, cuisine

A cuisine is a style of cooking characterized by distinctive ingredients, List of cooking techniques, techniques and Dish (food), dishes, and usually associated with a specific culture or geographic region. Regional food preparation techniques, ...

and mythology

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

. Although Irish (Gaeilge) was their main language in the past, today most Irish people speak English as their first language. Historically, the Irish nation was made up of kin groups or clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

, and the Irish also had their own religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

, law code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the co ...

, alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letter (alphabet), letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from a ...

and style of dress

Clothing (also known as clothes, garments, dress, apparel, or attire) is any item worn on a human human body, body. Typically, clothing is made of fabrics or textiles, but over time it has included garments made from animal skin and other thin s ...

.

There have been many notable Irish people throughout history. After Ireland's conversion to Christianity, Irish missionaries and scholars exerted great influence on Western Europe, and the Irish came to be seen as a nation of "saints and scholars". The 6th-century Irish monk and missionary Columbanus

Saint Columbanus (; 543 – 23 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in presen ...

is regarded as one of the "fathers of Europe", followed by saints Cillian and Fergal

Fergal or Feargal are Irish male given names. They are anglicised forms of the name Fearghal.Mairéad Byrne, Irish Baby Names – 25 Apr 2005

The arts

*Fergal Keane, OBE (born 1961), Irish writer and broadcaster

*Feargal Sharkey (born 1958), form ...

. The scientist Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

is considered the "father of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

", and Robert Mallet

Robert Mallet (3 June 1810 – 5 November 1881) was an Irish geophysicist, civil engineer, and inventor who distinguished himself by research concerning earthquakes (and is sometimes known as the father of seismology). His son, Frederick Ri ...

one of the "fathers of seismology

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes (or generally, quakes) and the generation and propagation of elastic ...

". Irish literature

Irish literature is literature written in the Irish, Latin, English and Scots ( Ulster Scots) languages on the island of Ireland. The earliest recorded Irish writing dates from back in the 7th century and was produced by monks writing in ...

has produced famous writers in both Irish- and English-language traditions, such as Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin

Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin (174829 June 1784), anglicized as Owen Roe O'Sullivan ("Red Owen"), was an Irish poet. He is known as one of the last great Gaelic poets. A recent anthology of Irish-language poetry speaks of his "extremely musical" p ...

, Dáibhí Ó Bruadair

Dáibhí Ó Bruadair (1625 – January 1698) was a 17th-century Irish language Irish poetry, poet who was probably received his training in a Bard, Bardic school . He lived through a period of change in Irish history, and his work reflects the de ...

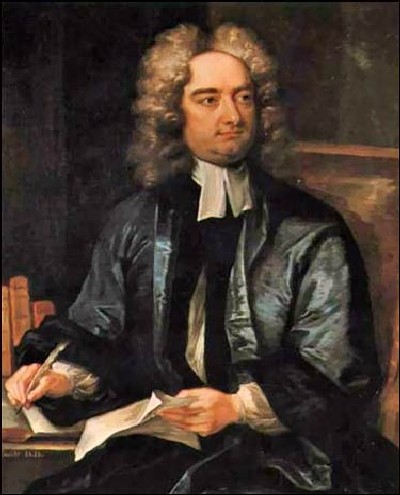

, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

, Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

, W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (, 13 June 186528 January 1939), popularly known as W. B. Yeats, was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer, and literary critic who was one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the ...

, Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish writer of novels, plays, short stories, and poems. Writing in both English and French, his literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal, and Tragicomedy, tra ...

, James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

, Máirtín Ó Cadhain

Máirtín Ó Cadhain (; 20 January 1906 – 18 October 1970) was one of the most prominent Irish language writers of the twentieth century. Perhaps best known for his 1949 novel , ÓCadhain played a key role in reintroducing modernist literatur ...

, Eavan Boland

Eavan Aisling Boland ( ; 24 September 1944 – 27 April 2020) was an Irish poet, author, and professor. She was a professor at Stanford University, where she had taught from 1996. Her work deals with the Irish national identity, and the role o ...

, and Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish Irish poetry, poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is ''Death of a Naturalist'' (1966), his first m ...

. Notable Irish explorers include Brendan the Navigator

Brendan of Clonfert (c. AD 484 – c. 577) is one of the early Celtic Christianity, Irish monastic saints and one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. He is also referred to as Brendan the Navigator, Brendan the Voyager, Brendan the Anchorite, ...

, Sir Robert McClure, Sir Alexander Armstrong, Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarc ...

and Tom Crean Tom or Thomas Crean may refer to:

*Thomas Crean (1873–1923), Irish rugby union player, British Army soldier and doctor

*Tom Crean (explorer) (1877–1938), Irish seaman and Antarctic explorer

*Tom Crean (basketball)

Thomas Aaron Crean (born Ma ...

. By some accounts, the first European child born in North America had Irish descent on both sides.Smiley, p. 630 Many presidents of the United States

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. Under the U.S. Constitution, the officeholder leads the executive bra ...

have had some Irish ancestry.

The population of Ireland is about 6.9 million, but it is estimated that 50 to 80 million people around the world have varying degrees of Irish ancestry. Historically, emigration from Ireland has been the result of conflict, famine and economic issues. People of Irish descent are found mainly in English-speaking countries, especially Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. There are also significant numbers in Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, and The United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE), or simply the Emirates, is a country in West Asia, in the Middle East, at the eastern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a Federal monarchy, federal elective monarchy made up of Emirates of the United Arab E ...

. The United States has the most people of Irish descent, while in Australia those of Irish descent are a higher percentage of the population than in any other country outside Ireland. Many Icelanders

Icelanders () are an ethnic group and nation who are native to the island country of Iceland. They speak Icelandic, a North Germanic language.

Icelanders established the country of Iceland in mid 930 CE when the (parliament) met for th ...

have Irish and Scottish Gaelic ancestors due to transportation there as slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

by the Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

during their settlement of Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

.

Origins and antecedents

Prehistoric and legendary ancestors

During the past 33,000 years, Ireland has witnessed different peoples arrive on its shores.

During the past 33,000 years, Ireland has witnessed different peoples arrive on its shores.

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia (; Ancient Greek: Πυθέας ὁ Μασσαλιώτης ''Pythéās ho Massaliōtēs''; Latin: ''Pytheas Massiliensis''; born 350 BC, 320–306 BC) was a Greeks, Greek List of Graeco-Roman geographers, geographer, explo ...

made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe in about 325 BC, but his account of it, known widely in Antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, has not survived and is now known only through the writings of others. On this voyage, he circumnavigated and visited a considerable part of modern-day Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. He was the first known scientific visitor to see and describe the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

and Germanic tribes.

The terms ''Irish'' and ''Ireland'' are probably derived from the goddess Ériu

In Irish mythology, Ériu (; ), daughter of Delbáeth and Ernmas of the Tuatha Dé Danann, was the eponymous matron goddess of Ireland.

The English name for Ireland comes from the name Ériu and the Germanic languages, Germanic (Old Norse or ...

. A variety of tribal groups and dynasties have inhabited the island, including the Airgialla, Fir Ol nEchmacht

was the name of a group of people living in pre-historic Ireland. The name may be translated as 'men' () of the 'people' (', possibly from ) 'of ' (), the last being the given name of the people or their territory, perhaps from ('horse') and (' ...

, Delbhna

The Delbna or Delbhna were a Gaelic Irish tribe in Ireland, claiming kinship with the Dál gCais, through descent from Dealbhna son of Cas. Originally one large population, they had a number of branches in Connacht, Meath, and Munster in Ireland. ...

, the mythical Fir Bolg

In medieval Irish myth, the Fir Bolg (also spelt Firbolg and Fir Bholg) are the fourth group of people to settle in Ireland. They are descended from the Muintir Nemid, an earlier group who abandoned Ireland and went to different parts of Europe. ...

, Érainn

The Iverni (, ') were a people of early Ireland first mentioned in Ptolemy's 2nd century ''Geography'' as living in the extreme south-west of the island. He also locates a "city" called Ivernis (, ') in their territory, and observes that this se ...

, Eóganachta

The Eóganachta (Modern , ) were an Irish dynasty centred on Rock of Cashel, Cashel which dominated southern Ireland (namely the Kingdom of Munster) from the 6/7th to the 10th centuries, and following that, in a restricted form, the Kingdom of De ...

, Mairtine

The Mairtine (Martini, Marthene, Muirtine, Maidirdine, Mhairtine) were an important people of late prehistoric Munster, Ireland who by early historical times appear to have completely vanished from the Irish political landscape. They are notable f ...

, Conmaicne

The Conmaicne (; ) were a people of early Ireland, perhaps related to the Laigin, who dispersed to various parts of Ireland. They settled in Connacht and Longford, giving their name to several Conmaicne territories. T. F. O'Rahilly's assertion ...

, Soghain

The Soghain were a people of ancient Ireland. The 17th-century scholar Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh identified them as part of a larger group called the Cruithin. Mac Fhirbhisigh stated that the Cruithin included "the Dál Araidhi ál nAraidi ...

, and Ulaid

(Old Irish, ) or (Irish language, Modern Irish, ) was a Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic Provinces of Ireland, over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups. Alternative names include , which ...

. In the cases of the Conmaicne, Delbhna, and perhaps Érainn, it can be demonstrated that the tribe took their name from their chief deity, or in the case of the Ciannachta, Eóganachta, and possibly the Soghain, a deified ancestor. This practice is paralleled by the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

dynasties.

One legend states that the Irish were descended from the Milesians, who supposedly conquered Ireland around 1000 BC or later.

Genetics

HaplogroupR1b

Haplogroup R1b (R-M343), previously known as Hg1 and Eu18, is a human Y-chromosome haplogroup.

It is the most frequently occurring paternal lineage in Western Europe, as well as some parts of Russia (e.g. the Bashkirs) and across the Sahel in ...

is the dominant haplogroup among Irish males, reaching a frequency of almost 80%. R-L21 is the dominant subclade within Ireland, reaching a frequency of 65%. This subclade is also dominant in Scotland, Wales and Brittany and descends from a common ancestor who lived in about 2,500 BC.

According to 2009 studies by Bramanti et al. and Malmström et al. on mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the DNA contained in ...

, related western European populations appear to be largely from the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

and not Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

era, as previously thought. There was discontinuity between Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

central Europe and modern European populations mainly due to an extremely high frequency of haplogroup U (particularly U5) types in Mesolithic central European sites.

The existence of an especially strong genetic association between the Irish and the Basques

The Basques ( or ; ; ; ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a Basque culture, common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Basques are indigenous peoples, ...

was first challenged in 2005, and in 2007 scientists began looking at the possibility of a more recent Mesolithic- or even Neolithic-era entrance of R1b into Europe. A new study published in 2010 by Balaresque et al. implies either a Mesolithic- or Neolithic- (not Paleolithic-) era entrance of R1b into Europe. Unlike previous studies, large sections of autosomal DNA

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosomes i ...

were analyzed in addition to paternal Y-DNA

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes in therian mammals and other organisms. Along with the X chromosome, it is part of the XY sex-determination system, in which the Y is the sex-determining chromosome because the presence of the Y ...

markers. They detected an autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosome ...

component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic or Mesolithic Europeans, and which would have been introduced into Europe with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as the Indo-European languages. This genetic component, labelled as "Yamnaya

The Yamnaya ( ) or Yamna culture ( ), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–C ...

" in the studies, then mixed to varying degrees with earlier Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

hunter-gatherer and Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

farmer populations already existing in western Europe.

A more recent whole genome analysis of Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

and Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

skeletal remains from Ireland suggested that the original Neolithic farming population was most similar to present-day Sardinians

Sardinians or Sards are an Italians, Italian ethno-linguistic group and a nation indigenous to Sardinia, an island in the western Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean which is administratively an Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special st ...

, while the three Bronze Age remains had a large genetic component from the Pontic-Caspian steppe. Modern Irish are the population most genetically similar to the Bronze Age remains, followed by Scottish and Welsh, and share more DNA with the three Bronze Age men from Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island (, ; Local Irish dialect: ''Reachraidh'', ; Scots: ''Racherie'') is an island and civil parish off the coast of County Antrim (of which it is part) in Northern Ireland. It is Northern Ireland's northernmost point. As of the 2021 ...

than with the earlier Ballynahatty Neolithic woman.

A 2017 genetic study done on the Irish shows that there is fine-scale population structure between different regional populations of the island, with the largest difference between native 'Gaelic' Irish populations and those of Ulster Protestants known to have recent, partial British ancestry. They were also found to have most similarity to two main ancestral sources: a 'French' component (mostly northwestern French) which reached highest levels in the Irish and other Celtic populations (Welsh, Highland Scots and Cornish) and showing a possible link to the Bretons

The Bretons (; or , ) are an ethnic group native to Brittany, north-western France. Originally, the demonym designated groups of Common Brittonic, Brittonic speakers who emigrated from Dumnonia, southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwal ...

; and a 'West Norwegian' component related to the Viking era.

As of 2016, 10,100 Irish nationals of African descent referred to themselves as "Black Irish" in the national census. The term "Black Irish" is sometimes used outside Ireland to refer to Irish people with black hair and dark eyes. One theory is that they are descendants of Spanish traders or of the few sailors of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

who were shipwrecked on Ireland's west coast, but there is little evidence for this.

Irish Travellers

Irish Travellers

Irish Travellers (, meaning ''the walking people''), also known as Mincéirs ( Shelta: ''Mincéirí'') or Pavees, are a traditionally peripatetic indigenous ethno-cultural group originating in Ireland.''Questioning Gypsy identity: ethnic na ...

are an ethnic

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

people of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. A DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

study found they originally descended from the general Irish population, however, they are now very distinct from it. The emergence of Travellers as a distinct group occurred long before the Great Famine, a genetic analysis shows. The research suggests that Traveller origins may in fact date as far back as 420 years to 1597. The Plantation of Ulster began around that time, with native Irish displaced from the land, perhaps to form a nomadic population.

History

Early expansion and the coming of Christianity

One Roman historian records that the Irish people were divided into "sixteen different nations" or tribes.MacManus, p 86 Traditional histories assert that the Romans never attempted to conquer Ireland, although it may have been considered. The Irish were not, however, cut off from Europe; they frequently raided the Roman territories, and also maintained trade links.

Among the most famous people of ancient Irish history are the

One Roman historian records that the Irish people were divided into "sixteen different nations" or tribes.MacManus, p 86 Traditional histories assert that the Romans never attempted to conquer Ireland, although it may have been considered. The Irish were not, however, cut off from Europe; they frequently raided the Roman territories, and also maintained trade links.

Among the most famous people of ancient Irish history are the High Kings of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and was later sometimes assigned anachronously or to leg ...

, such as Cormac mac Airt

Cormac mac Airt, also known as Cormac ua Cuinn (grandson of Conn) or Cormac Ulfada (long beard), was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. He is probably the most famous of the ancient High Kings ...

and Niall of the Nine Hostages

Niall Noígíallach (; Old Irish "having nine hostages"), or Niall of the Nine Hostages, was a legendary, semi-historical Irish king who was the ancestor of the Uí Néill dynasties that dominated Ireland from the 6th to the 10th centuries. ...

, and the semi-legendary Fianna

''Fianna'' ( , ; singular ''Fian''; ) were small warrior-hunter bands in Gaelic Ireland during the Iron Age and early Middle Ages. A ''fian'' was made up of freeborn young men, often from the Gaelic nobility of Ireland, "who had left fosterage ...

. The 20th-century writer Seumas MacManus

Seumas MacManus (31 December 1868 – 23 October 1960) was an Irish author, dramatist, and poet known for his ability to reinterpret Irish folktales for modern audiences.

Biography

Born James McManus on 31 December 1868 in Mountcharles, Count ...

wrote that even if the Fianna and the Fenian Cycle

The Fenian Cycle (), Fianna Cycle or Finn Cycle () is a body of early Irish literature focusing on the exploits of the mythical hero Fionn mac Cumhaill, Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill and his Kóryos, warrior band the Fianna. Sometimes called the ...

were purely fictional, they would still be representative of the character of the Irish people:

The introduction of Christianity to the Irish people during the 5th century brought a radical change to the Irish people's foreign relations.MacManus, p 89 The only military raid abroad recorded after that century is a presumed invasion of Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, which according to a Welsh manuscript may have taken place around the 7th century. In the words of Seumas MacManus:

Following the conversion of the Irish to Christianity, Irish secular laws and social institutions remained in place.

Migration and invasion in the Middle Ages

The 'traditional' view is that, in the 4th or 5th century, Goidelic language and Gaelic culture was brought to Scotland by settlers from Ireland, who founded the Gaelic kingdom of

The 'traditional' view is that, in the 4th or 5th century, Goidelic language and Gaelic culture was brought to Scotland by settlers from Ireland, who founded the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

on Scotland's west coast. This is based mostly on medieval writings from the 9th and 10th centuries. The archaeologist Ewan Campbell

Ewan Campbell is a Scottish archaeologist and author, who serves as the senior lecturer of archaeology at the University of Glasgow. An author of a number of books, he is perhaps best known as the originator of the historical revisionist thesis ...

argues against this view, saying that there is no archaeological or placename evidence for a migration or a takeover by a small group of elites. He states that "the Irish migration hypothesis seems to be a classic case of long-held historical beliefs influencing not only the interpretation of documentary sources themselves but the subsequent invasion paradigm being accepted uncritically in the related disciplines of archaeology and linguistics."Campbell, Ewan.Were the Scots Irish?

" in ''Antiquity'' #75 (2001). Dál Riata and the territory of the neighbouring

Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

merged to form the Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba (; ) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the First War of Scotti ...

, and Goidelic language and Gaelic culture became dominant there. The country came to be called ''Scotland'', after the Roman name for the Gaels: ''Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. It originally referred to all Gaels, first those in Ireland and then those ...

''. The Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

and the Manx people

The Manx ( ; ) are an ethnic group originating on the Isle of Man, in the Irish Sea in Northern Europe. They belong to the diaspora of the Gaels, Gaelic ethnolinguistic group, which now populate the parts of the British Isles which once were ...

also came under massive Gaelic influence in their history.

Irish missionaries such as Saint Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Gaelic Ireland, Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the ...

brought Christianity to Pictish Scotland. The Irishmen of this time were also "aware of the cultural unity of Europe", and it was the 6th-century Irish monk Columbanus

Saint Columbanus (; 543 – 23 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in presen ...

who is regarded as "one of the fathers of Europe". Another Irish saint, Aidan of Lindisfarne

Aidan of Lindisfarne (; died 31 August 651) was an Irish monk and missionary credited with converting the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity in Northumbria. He founded a ministry cathedral on the island of Lindisfarne, known as Lindisfarne Priory, ser ...

, has been proposed as a possible patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of the United Kingdom, while Saints Kilian and Vergilius

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: the ''Eclogues'' ( ...

became the patron saints of Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is, after Nuremberg and Fürth, the Franconia#Towns and cities, third-largest city in Franconia located in the north of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Lower Franconia. It sp ...

in Germany and Salzburg

Salzburg is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020 its population was 156,852. The city lies on the Salzach, Salzach River, near the border with Germany and at the foot of the Austrian Alps, Alps moun ...

in Austria, respectively.

Irish missionaries founded monasteries outside Ireland, such as Iona Abbey

Iona Abbey is an abbey located on the island of Iona, just off the Isle of Mull on the West Coast of Scotland.

It is one of the oldest History of early Christianity, Christian religious centres in Western Europe. The abbey was a focal point ...

, the Abbey of St Gall

The Abbey of Saint Gall () is a dissolved abbey (747–1805) in a Catholic religious complex in the city of St. Gallen in Switzerland. The Carolingian Renaissance, Carolingian-era monastery existed from 719, founded by Saint Othmar on the spot wh ...

in Switzerland, and Bobbio Abbey

Bobbio Abbey (Italian: ''Abbazia di San Colombano'') is a monastery founded by Irish Saint Columbanus in 614, around which later grew up the town of Bobbio, in the province of Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. It is dedicated to Saint Columbanus. ...

in Italy.

Common to both the monastic and the secular bardic schools were Irish and Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. With Latin, the early Irish scholars "show almost a like familiarity that they do with their own Gaelic". There is evidence also that Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

were studied, the latter probably being taught at Iona.

Since the time of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

, Irish scholars had a considerable presence in the Frankish court, where they were renowned for their learning. The most significant Irish intellectual of the early monastic period was the 9th century Johannes Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena, also known as Johannes Scotus Erigena, John the Scot or John the Irish-born ( – c. 877), was an Irish Neoplatonist philosopher, theologian and poet of the Early Middle Ages. Bertrand Russell dubbed him "the most ...

, an outstanding philosopher in terms of originality. He was the earliest of the founders of scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

, the dominant school of medieval philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, ...

.Toman, p 10: "Abelard

Peter Abelard (12 February 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, teacher, musician, composer, and poet. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

In philo ...

himself was... together with John Scotus Erigena (9th century), and Lanfranc

Lanfranc, OSB (1005 1010 – 24 May 1089) was an Italian-born English churchman, monk and scholar. Born in Italy, he moved to Normandy to become a Benedictine monk at Bec. He served successively as prior of Bec Abbey and abbot of St Ste ...

and Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also known as (, ) after his birthplace and () after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher, and theologian of the Catholic Church, who served as Archbishop of Canterb ...

(both 11th century), one of the founders of scholasticism." He had considerable familiarity with the Greek language, and translated many works into Latin, affording access to the Cappadocian Fathers

The Cappadocian Fathers, also traditionally known as the Three Cappadocians, were a trio of Byzantine Christian prelates, theologians and monks who helped shape both early Christianity and the monastic tradition. Basil the Great (330–379) wa ...

and the Greek theological tradition, previously almost unknown in the Latin West.

The influx of Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

raiders and traders in the 9th and 10th centuries resulted in the founding of many of Ireland's most important towns, including Cork

"Cork" or "CORK" may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Stopper (plug), or "cork", a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

*** Wine cork an item to seal or reseal wine

Places Ireland

* ...

, Dublin, Limerick

Limerick ( ; ) is a city in western Ireland, in County Limerick. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is in the Mid-West Region, Ireland, Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. W ...

, and Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

(earlier Gaelic settlements on these sites did not approach the urban nature of the subsequent Norse trading ports). The Vikings left little impact on Ireland other than towns and certain words added to the Irish language, but many Irish taken as slaves inter-married with the Scandinavians, hence forming a close link with the Icelandic people

Icelanders () are an ethnic group and nation who are native to the island country of Iceland. They speak Icelandic, a North Germanic language.

Icelanders established the country of Iceland in mid 930 CE when the (parliament) met for ...

. In the Icelandic '' Laxdœla saga'', for example, "even slaves are highborn, descended from the kings of Ireland." The first name of Njáll Þorgeirsson

Njáll Þorgeirsson (Old Norse: ; Modern Icelandic: ) was a 10th and early-11th-century Icelandic lawyer who lived at Bergþórshvoll in Landeyjar, Iceland. He was one of the main protagonists of ''Njáls saga'', a medieval Icelandic saga which ...

, the chief protagonist of ''Njáls saga

''Njáls saga'' ( ), also ''Njála'' ( ), or ''Brennu-Njáls saga'' ( ) (Which can be translated as ''The Story of Burnt Njáll'', or ''The Saga of Njáll the Burner''), is a thirteenth-century Icelandic saga that describes events between 960 a ...

'', is a variation of the Irish name Neil

Neil is a masculine name of Irish origin. The name is an anglicisation of the Irish ''Niall'' which is of disputed derivation. The Irish name may be derived from words meaning "cloud", "passionate", "victory", "honour" or "champion".. As a surname ...

. According to '' Eirik the Red's Saga'', the first European couple to have a child born in North America was descended from the Viking Queen of Dublin, Aud the Deep-minded, and a Gaelic slave brought to Iceland.

The arrival of the

The arrival of the Anglo-Normans

The Anglo-Normans (, ) were the medieval ruling class in the Kingdom of England following the Norman Conquest. They were primarily a combination of Normans, Bretons, Flemings, French people, Frenchmen, Anglo-Saxons and Celtic Britons.

Afte ...

brought also the Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

, Flemish

Flemish may refer to:

* Flemish, adjective for Flanders, Belgium

* Flemish region, one of the three regions of Belgium

*Flemish Community, one of the three constitutionally defined language communities of Belgium

* Flemish dialects, a Dutch dialec ...

, Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

, and Bretons

The Bretons (; or , ) are an ethnic group native to Brittany, north-western France. Originally, the demonym designated groups of Common Brittonic, Brittonic speakers who emigrated from Dumnonia, southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwal ...

. Most of these were assimilated into Irish culture

The culture of Ireland includes the Irish art, art, Music of Ireland, music, Irish dance, dance, Irish mythology, folklore, Irish clothing, traditional clothing, Irish language, language, Irish literature, literature, Irish cuisine, cuisine ...

and polity by the 15th century, with the exception of some of the walled towns and the Pale

The Pale ( Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast s ...

areas. The Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

also saw the settlement of Scottish gallowglass

The Gallowglass (also spelled galloglass, gallowglas or galloglas; from meaning "foreign warriors") were a class of elite mercenary warriors who were principally members of the Norse-Gaelic clans of Ireland and Scotland between the mid 13th ...

families of mixed Gaelic-Norse and Pict

PICT is a graphics file format introduced on the original Apple Macintosh computer as its standard metafile format. It allows the interchange of graphics (both bitmapped and vector), and some limited text support, between Mac applications, an ...

descent, mainly in the north; due to similarities of language and culture they too were assimilated.

Surnames

The Irish were among the first people in Europe to use surnames as we know them today. It is very common for people ofGaelic

Gaelic (pronounced for Irish Gaelic and for Scots Gaelic) is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". It may refer to:

Languages

* Gaelic languages or Goidelic languages, a linguistic group that is one of the two branches of the Insul ...

origin to have the English versions of their surnames beginning with 'Ó' or 'Mac' (Over time however many have been shortened to 'O' or Mc). 'O' comes from the Irish Ó which in turn came from Ua, which means "grandson

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

", or " descendant" of a named person. Mac is the Irish for son.

Names that begin with "O'" include: Ó Bánion (O'Banion O'Banion is a surname. Notable people with the surname

In many societies, a surname, family name, or last name is the mostly hereditary portion of one's personal name that indicates one's family. It is typically combined with a given name t ...

), Ó Briain ( O'Brien), Ó Ceallaigh (O'Kelly

O'Kelly or Kelly is an Irish surname. It derives from the Kings of Uí Maine.

Notable people with the surname include:

* Aloysius O'Kelly (1853–1936), Irish painter, brother of James Joseph O'Kelly

* Auguste O'Kelly (1829–1900), music publ ...

), Ó Conchobhair ( O'Connor, O'Conor), Ó Chonaill (O'Connell O'Connell may refer to:

People

*O'Connell (name), people with O'Connell as a last name or given name

Schools

* Bishop Denis J. O'Connell High School, a high school in Arlington, Virginia

Places

* Mount O'Connell National Park in Queensland ...

), O'Coiligh (Cox

Cox or COX may refer to:

Companies

* Cox Enterprises, a media and communications company

** Cox Communications, cable provider

** Cox Media Group, a company that owns television and radio stations

** Cox Automotive, an Atlanta-based busines ...

), Ó Cuilinn ( Cullen), Ó Domhnaill (O'Donnell

The O'Donnell dynasty ( or ''Ó Domhnaill,'' ''Ó Doṁnaill'' ''or Ua Domaill;'' meaning "descendant of Dónal") were the dominant Irish clan of the kingdom of Tyrconnell in Ulster in the north of medieval and early modern Ireland.

Naming ...

), Ó Drisceoil (O'Driscoll

O'Driscoll (and its derivative Driscoll) is an Irish surname. It is derived from the Gaelic ''Ó hEidirsceoil''. The O'Driscolls were rulers of the Dáirine sept of the Corcu Loígde until the early modern period; their ancestors were Kings ...

), Ó hAnnracháin, ( Hanrahan), Ó Máille ( O'Malley), Ó Mathghamhna (O'Mahony

O'Mahony (Old Irish: ''Ó Mathghamhna''; Modern Irish: ''Ó Mathúna'') is the original name of the clan, with breakaway clans also spelled O'Mahoney, or simply Mahony, Mahaney and Mahoney, without the prefix. Brodceann O'Mahony was the eldest of t ...

), Ó Néill (O'Neill

The O'Neill dynasty ( Irish: ''Ó Néill'') are a lineage of Irish Gaelic origin that held prominent positions and titles in Ireland and elsewhere. As kings of Cenél nEógain, they were historically one of the most prominent family of the Nor ...

), Ó Sé (O'Shea

O'Shea is a surname and, less often, a given name. It is an anglicized form of the Irish patronymic name Ó Séaghdha or Ó Sé, originating in the Kingdom of Corcu Duibne in County Kerry. Historian C. Thomas Cairney states that the O'Sheas were ...

), Ó Súilleabháin (O'Sullivan O'Sullivan may refer to:

People

* O'Sullivan family, a gaelic Irish clan

* O'Sullivan (surname), a family name

* Sullivan (surname), a variation of the O'Sullivan family name

Places

* O'Sullivan Dam, Washington, United States

* O'Sullivan Army He ...

), Ó Caiside/Ó Casaide ( Cassidy), Ó Brádaigh/Mac Bradaigh (Brady

Brady may refer to:

People

* Brady (surname)

* Brady (given name)

* Brady (nickname)

* Brady Boone, a ring name of American professional wrestler Dean Peters (1958–1998)

Places in the United States

* Brady, Montana, a census-designated plac ...

) and Ó Tuathail ( O'Toole).

Names that begin with Mac or Mc include: Mac Cárthaigh (McCarthy McCarthy (also spelled MacCarthy or McCarty) may refer to:

* MacCarthy dynasty, a Gaelic Irish clan

* McCarthy, Alaska, United States

* McCarty, Missouri, United States

* McCarthy Road, a road in Alaska

* McCarthy (band), an indie pop band

* Châte ...

), Mac Diarmada (McDermott

McDermott or MacDermott is an Irish surname and the anglicised version of Mac Diarmada (also spelled Mac Diarmata), the surname of the ruling dynasty of Moylurg, a kingdom that existed in Connacht from the 10th to 16th centuries.

The last ruling ...

), Mac Domhnaill (McDonnell

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer based in St. Louis, Missouri. The company was founded on July 6, 1939, by James Smith McDonnell, and was best known for its military fighters, including the F-4 Phantom II ...

), and Mac Mathghamhna (McMahon McMahon or MacMahon ( or ) may refer to:

Places

* Division of McMahon, an electorate for the Australian House of Representatives

* McMahon, Saskatchewan, a hamlet in Canada

* McMahon Line, a boundary between India and China

* McMahons Point, a ...

) Mac(g) Uidhir (Maguire

The Maguire ( ) family is an Irish clans, Irish clan based in County Fermanagh. The name derives from the Goidelic languages, Gaelic , which is "son of Odhar" meaning 'Wikt:sallow, sallow' or 'pale-faced'.

According to legend, this relates to the ...

), Mac Dhonnchadha (McDonagh

The surname McDonagh, also spelled MacDonagh is from the Irish language Mac Dhonnchadha, and is now one of the rarer surnames of Ireland.

Mac Dhonnchadha, Mac Donnchadha, Mac Donnacha or Mac Donnchaidh or Mac Donnacha is the original form of ...

), Mac Conmara (MacNamara

MacNamara or McNamara ( Irish: ''Mac Con Mara'') is an Irish surname of a family of County Clare in Ireland. According to historian C. Thomas Cairney, the MacNamaras were one of the chiefly families of the Dal gCais or Dalcassians who were a tri ...

), Mac Craith (McGrath

McGrath or MacGrath derives from the Irish surname Mac Craith and is occasionally noted with a space: e.g. Izzy Mc Grath. In Ireland, it is pronounced "Mack Grah" "Mick Grah" or "Ma Grah". In Australia and New Zealand it is pronounced ''MuhGrah''.

...

), Mac Aodha (McGee

McGee or McGees may refer to:

People

* McGee (surname), a surname of Irish origin, including a list of people with this surname

Places United States

*McGee, Missouri

*McGees, Washington

*McGee, West Virginia

Infrastructure

*McGees Bridge

Mc ...

), Mac Aonghuis (McGuinness

McGuinness (also MacGuinness, McGinnis, Guinness) is an Irish surname. It derives from and is an anglicized form of the Gaelic ''Mac Aonghuis'', literally meaning "son of Angus" (Angus meaning "one, choice"). It may also denote the name Mac Nao ...

), Mac Cana (McCann McCann may refer to:

* McCann (surname)

* McCann (company), advertising agency

* McCann Worldgroup, network of marketing and advertising agencies

* Marist College athletic facilities

** McCann Arena

** James J. McCann Baseball Field

* McCann Res ...

), Mac Lochlainn ( McLaughlin) and Mac Conallaidh ( McNally). Mac is commonly anglicised Mc. However, "Mac" and "Mc" are not mutually exclusive, so, for example, both "MacCarthy" and "McCarthy" are used. Both "Mac" and "Ó'" prefixes are both Irish in origin, Anglicized Prefix Mc is far more common in Ireland than Scotland with 2/3 of all Mc Surnames being Irish in origin However, "Mac" is more common in Scotland and Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

than in the rest of Ireland; furthermore, "Ó" surnames are less common in Scotland having been brought to Scotland from Ireland. The proper surname for a woman in Irish uses the feminine prefix nic (meaning daughter) in place of mac. Thus a boy may be called Mac Domhnaill whereas his sister would be called Nic Dhomhnaill or Ní Dhomhnaill – the insertion of 'h' follows the female prefix in the case of most consonants (bar H, L, N, R, & T).

A son has the same surname as his father. A female's surname replaces Ó with Ní (reduced from Iníon Uí – "daughter of the grandson of") and Mac with Nic (reduced from Iníon Mhic – "daughter of the son of"); in both cases the following name undergoes lenition. However, if the second part of the surname begins with the letter C or G, it is not lenited after Nic. Thus the daughter of a man named Ó Maolagáin has the surname ''Ní Mhaolagáin'' and the daughter of a man named Mac Gearailt has the surname ''Nic Gearailt''. When anglicised, the name can remain O' or Mac, regardless of gender.

There are a number of Irish surnames derived from Norse personal names, including

A son has the same surname as his father. A female's surname replaces Ó with Ní (reduced from Iníon Uí – "daughter of the grandson of") and Mac with Nic (reduced from Iníon Mhic – "daughter of the son of"); in both cases the following name undergoes lenition. However, if the second part of the surname begins with the letter C or G, it is not lenited after Nic. Thus the daughter of a man named Ó Maolagáin has the surname ''Ní Mhaolagáin'' and the daughter of a man named Mac Gearailt has the surname ''Nic Gearailt''. When anglicised, the name can remain O' or Mac, regardless of gender.

There are a number of Irish surnames derived from Norse personal names, including Mac Suibhne

The Gaelic surname Mac Suibhne is a patronymic form of '' Suibhne'' and means "son of ''Suibhne''". The personal name ''Suibhne'' means "pleasant". Hanks; Coates; McClure (2016a) p. 1804; Hanks; Coates; McClure (2016b) p. 2604.

Anglicised forms o ...

(Sweeney) from Swein and McAuliffe from "Olaf". The name Cotter, local to County Cork

County Cork () is the largest and the southernmost Counties of Ireland, county of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, named after the city of Cork (city), Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster ...

, derives from the Norse personal name Ottir. The name Reynolds is an Anglicization of the Irish Mac Raghnaill, itself originating from the Norse names Randal or Reginald. Though these names were of Viking derivation some of the families who bear them appear to have had Gaelic origins.

"Fitz" is an old Norman French variant of the Old French word (variant spellings , , , etc.), used by the Normans, meaning ''son''. The Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

themselves were descendants of Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

, who had settled in Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

and thoroughly adopted the French language and culture. With the exception of the Gaelic-Irish Fitzpatrick (Mac Giolla Phádraig

Mac or MAC may refer to:

Common meanings

* Mac (computer), a line of personal computers made by Apple Inc.

* Mackintosh, a raincoat made of rubberized cloth

* Mac, a prefix to surnames derived from Gaelic languages

* McIntosh (apple), a Canadian ...

) surname, all names that begin with Fitz – including FitzGerald Fitzgerald may refer to:

People

* Fitzgerald (surname), a surname

* Fitzgerald Hinds, Trinidadian politician

* Fitzgerald Toussaint (born 1990), former American football running back

Place Australia

* Fitzgerald River National Park, a nati ...

(Mac Gearailt), Fitzsimons (Mac Síomóin/Mac an Ridire) and FitzHenry (Mac Anraí) – are descended from the initial Norman settlers. A small number of Irish families of Goidelic

The Goidelic ( ) or Gaelic languages (; ; ) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle o ...

origin came to use a Norman form of their original surname—so that Mac Giolla Phádraig became Fitzpatrick—while some assimilated so well that the Irish name was dropped in favour of a new, Hiberno-Norman form. Another common Irish surname of Norman Irish

Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans (; ) is a modern term for the descendants of Norman settlers who arrived during the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. Most came from England and Wales. They are distinguished from the native ...

origin is the 'de' habitational prefix, meaning 'of' and originally signifying prestige and land ownership. Examples include de Búrca (Burke), de Brún, de Barra (Barry), de Stac (Stack), de Tiúit, de Faoite (White), de Londras (Landers), de Paor (Power). The Irish surname "Walsh" (in Irish ) was routinely given to settlers of Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

origin, who had come during and after the Norman invasion. The Joyce and Griffin/Griffith (Gruffydd) families are also of Welsh origin.

The Mac Lochlainn, Ó Maol Seachlainn, Ó Maol Seachnaill, Ó Conchobhair, Mac Loughlin and Mac Diarmada families, all distinct, are now all subsumed together as MacLoughlin. The full surname usually indicated which family was in question, something that has been diminished with the loss of prefixes such as Ó and Mac. Different branches of a family with the same surname sometimes used distinguishing epithets, which sometimes became surnames in their own right. Hence the chief of the clan Ó Cearnaigh (Kearney) was referred to as An Sionnach (Fox), which his descendants use to this day. Similar surnames are often found in Scotland for many reasons, such as the use of a common language and mass Irish migration to Scotland in the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries.

Late Medieval and Tudor Ireland

The Irish people of the Late Middle Ages were active as traders on the European continent.MacManus, p 343 They were distinguished from the English (who only used their own language or French) in that they only usedLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

abroad—a language "spoken by all educated people throughout Gaeldom". According to the writer Seumas MacManus

Seumas MacManus (31 December 1868 – 23 October 1960) was an Irish author, dramatist, and poet known for his ability to reinterpret Irish folktales for modern audiences.

Biography

Born James McManus on 31 December 1868 in Mountcharles, Count ...

, the explorer Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

visited Ireland to gather information about the lands to the west,MacManus, p 343–344 a number of Irish names are recorded on Columbus' crew roster preserved in the archives of Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

and it was an Irishman named Patrick Maguire who was the first to set foot in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

in 1492; however, according to Morison Morison is a surname found in the English-speaking world. It is a variant form of Morrison. It was one of the original ways of spelling the name of the Clan Morrison, before Morrison with two r's became popular.

People with this surname

* Alexan ...

and Miss Gould, who made a detailed study of the crew list of 1492, no Irish or English sailors were involved in the voyage.

An English report of 1515 states that the Irish people were divided into over sixty Gaelic lordships and thirty Anglo-Irish lordships.Nicholls The English term for these lordships was "nation" or "country". The Irish term "''oireacht''" referred to both the territory and the people ruled by the lord. Literally, it meant an "assembly", where the Brehon

Brehon (, ) is a term for a historical arbitration, mediative, and judicial role in Gaelic culture. Brehons were part of the system of Early Irish law, which was also simply called " Brehon law". Brehons were judges, close in importance to the ...

s would hold their courts upon hills to arbitrate the matters of the lordship. Indeed, the Tudor lawyer John Davies described the Irish people with respect to their laws:

Another English commentator records that the assemblies were attended by "all the scum of the country"—the labouring population as well as the landowners. While the distinction between "free" and "unfree" elements of the Irish people was unreal in legal terms, it was a social and economic reality. Social mobility was usually downwards, due to social and economic pressures. The ruling clan's "expansion from the top downwards" was constantly displacing commoners and forcing them into the margins of society.

As a clan-based society, genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

was all important. Ireland 'was justly styled a "Nation of Annalists"'. The various branches of Irish learning—including law, poetry, history and genealogy, and medicine—were associated with hereditary learned families. The poetic families included the Uí Dhálaigh (Daly) and the MacGrath. Irish physicians, such as the O'Briens in Munster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

or the MacCailim Mor in the Western Isles