Paris meridian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the

In the year 1634, France, then ruled by

In the year 1634, France, then ruled by

Cesar-François Cassini de Thury completed the

Cesar-François Cassini de Thury completed the

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrarily chosen meridian (geography), meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. On a spheroid, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian ...

of the world. The "Paris meridian arc" or "French meridian arc" (French: ''la Méridienne de France'') is the name of the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

measured along the Paris meridian.

The French meridian arc was important for French cartography, since the triangulations of France began with the measurement of the French meridian arc. Moreover, the French meridian arc was important for geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

as it was one of the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

s which were measured to determine the figure of the Earth

In geodesy, the figure of the Earth is the size and shape used to model planet Earth. The kind of figure depends on application, including the precision needed for the model. A spherical Earth is a well-known historical approximation that is ...

via the arc measurement method. The determination of the figure of the Earth was a problem of the highest importance in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, as the diameter of the Earth was the unit to which all celestial distances had to be referred.

History

French cartography and the figure of the Earth

In the year 1634, France, then ruled by

In the year 1634, France, then ruled by Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

and Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu (9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), commonly known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic prelate and statesman who had an outsized influence in civil and religi ...

, decided that the Ferro Meridian through the westernmost of the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

should be used as the reference on maps, since El Hierro (Ferro) was the most western position of the Ptolemy's world map. It was also thought to be exactly 20 degrees west of Paris. The astronomers of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

, founded in 1666, managed to clarify the position of El Hierro relative to the meridian of Paris, which gradually supplanted the Ferro meridian. In 1666, Louis XIV of France

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

had authorized the building of the Paris Observatory. On Midsummer's Day 1667, members of the Academy of Sciences traced the future building's outline on a plot outside town near the Port Royal abbey, with Paris meridian exactly bisecting the site north–south. French cartographers would use it as their prime meridian for more than 200 years. Old maps from continental Europe often have a common grid with Paris degrees at the top and Ferro degrees offset by 20 at the bottom.

A French astronomer, Abbé Jean Picard, measured the length of a degree of latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

along the Paris meridian ( arc measurement) and computed from it the size of the Earth during 1668–1670. The application of the telescope to angular instruments was an important step. He was the first who in 1669, with the telescope, using such precautions as the nature of the operation requires, measured a precise arc of meridian ( Picard's arc measurement). He measured with wooden rods a baseline of 5,663 toises, and a second or base of verification of 3,902 toises; his triangulation network extended from Malvoisine, near Paris, to Sourdon, near Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; , or ) is a city and Communes of France, commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme (department), Somme Departments of France, department in the region ...

. The angles of the triangles were measured with a quadrant furnished with a telescope having cross-wires. The difference of latitude of the terminal stations was determined by observations made with a sector on a star in Cassiopeia

Cassiopeia or Cassiopea may refer to:

Greek mythology

* Cassiopeia (mother of Andromeda), queen of Aethiopia and mother of Andromeda

* Cassiopeia (wife of Phoenix), wife of Phoenix, king of Phoenicia

* Cassiopeia, wife of Epaphus, king of Egy ...

, giving 1° 22′ 55″ for the amplitude. The terrestrial degree measurement gave the length of 57,060 toises, whence he inferred 6,538,594 toises for the Earth's diameter.

Four generations of the Cassini family headed the Paris Observatory. They directed the surveys of France for over 100 years. Hitherto geodetic observations had been confined to the determination of the magnitude of the Earth considered as a sphere, but a discovery made by Jean Richer

Jean Richer (1630–1696) was a French astronomer and assistant (''élève astronome'') at the French Academy of Sciences, under the direction of Giovanni Domenico Cassini.

Between 1671 and 1673 he performed experiments and carried out celestial ...

turned the attention of mathematicians to its deviation from a spherical form. This astronomer, having been sent by the Academy of Sciences of Paris to the island of Cayenne

Cayenne (; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and capital city of French Guiana, an overseas region and Overseas department, department of France located in South America. The city stands on a former island at the mouth of the Caye ...

(now in French Guiana

French Guiana, or Guyane in French, is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas and the West Indies. Bordered by Suriname to the west ...

) in South America, for the purpose of investigating the amount of astronomical refraction and other astronomical objects, observed that his clock, which had been regulated at Paris to beat seconds, lost about two minutes and a half daily at Cayenne, and that to bring it to measure mean solar time it was necessary to shorten the pendulum by more than a line (about 1⁄12th of an in.). This fact, which was scarcely credited till it had been confirmed by the subsequent observations of Varin and Deshayes on the coasts of Africa and America, was first explained in the third book of Newton’s '' Principia'', who showed that it could only be referred to a diminution of gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

arising either from a protuberance of the equatorial parts of the Earth and consequent increase of the distance from the centre, or from the counteracting effect of the centrifugal force. About the same time (1673) appeared Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

’ ''De Horologio Oscillatorio'', in which for the first time were found correct notions on the subject of centrifugal force

Centrifugal force is a fictitious force in Newtonian mechanics (also called an "inertial" or "pseudo" force) that appears to act on all objects when viewed in a rotating frame of reference. It appears to be directed radially away from the axi ...

. It does not, however, appear that they were applied to the theoretical investigation of the figure of the Earth before the publication of Newton's ''Principia''. In 1690 Huygens published his ''De Causa Gravitatis'', which contains an investigation of the figure of the Earth on the supposition that the attraction of every particle is towards the centre.

Between 1684 and 1718 Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian-French mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the County of Nice, part of the Savoyard sta ...

and Jacques Cassini

Jacques Cassini (18 February 1677 – 16 April 1756) was a French astronomer, son of the famous Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini. He was known as Cassini II.

Biography

Cassini was born at the Paris Observatory. He was first admitted ...

, along with Philippe de La Hire

Philippe de La Hire (or Lahire, La Hyre or Phillipe de La Hire) (18 March 1640 – 21 April 1718)

, carried a triangulation, starting from Picard's base in Paris and extending it northwards to Dunkirk and southwards to Collioure. They measured a base of 7,246 toises near Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

, and a somewhat shorter base near Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

; and from the northern portion of the arc, which had an amplitude of 2° 12′ 9″, obtained 56,960 toises for the length of a degree; while from the southern portion, of which the amplitude was 6° 18′ 57″, they obtained 57,097 toises. The immediate inference from this was that, with the degree diminishing with increasing latitude, the Earth must be a prolate spheroid

A spheroid, also known as an ellipsoid of revolution or rotational ellipsoid, is a quadric surface (mathematics), surface obtained by Surface of revolution, rotating an ellipse about one of its principal axes; in other words, an ellipsoid with t ...

. This conclusion was totally opposed to the theoretical investigations of Newton and Huygens, and accordingly the Academy of Sciences of Paris determined to apply a decisive test by the measurement of arcs at a great distance from each other – one in the neighbourhood of the equator, the other in a high latitude. Thus arose the celebrated , to the Equator and to Lapland, the latter directed by Pierre Louis Maupertuis

Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (; ; 1698 – 27 July 1759) was a French mathematician, philosopher and man of letters. He became the director of the Académie des Sciences and the first president of the Prussian Academy of Science, at the ...

.

In 1740 an account was published in the Paris ''Mémoires'', by Cassini de Thury, of a remeasurement by himself and Nicolas Louis de Lacaille

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (; 15 March 171321 March 1762), formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Goo ...

of the meridian of Paris. With a view to determine more accurately the variation of the degree along the meridian, they divided the distance from Dunkirk to Collioure into four partial arcs of about two degrees each, by observing the latitude at five stations. The results previously obtained by Giovanni Domenico and Jacques Cassini were not confirmed, but, on the contrary, the length of the degree derived from these partial arcs showed on the whole an increase with increasing latitude.

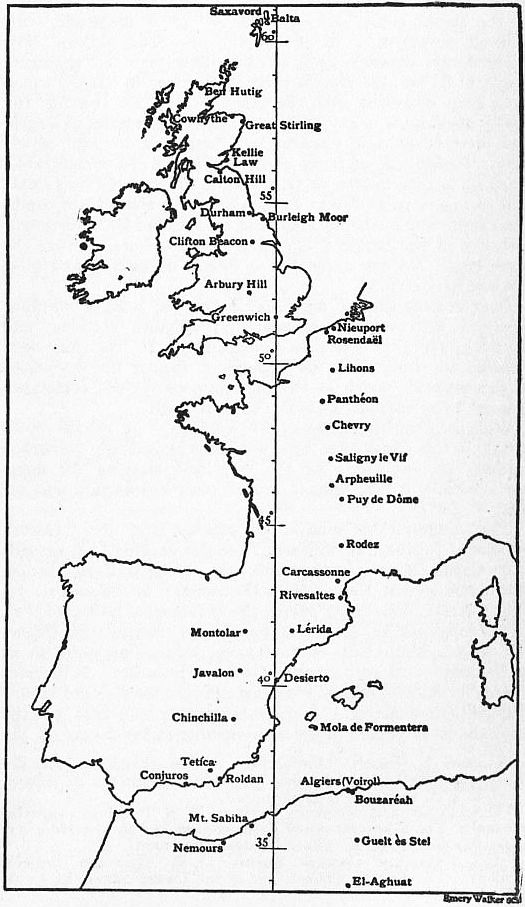

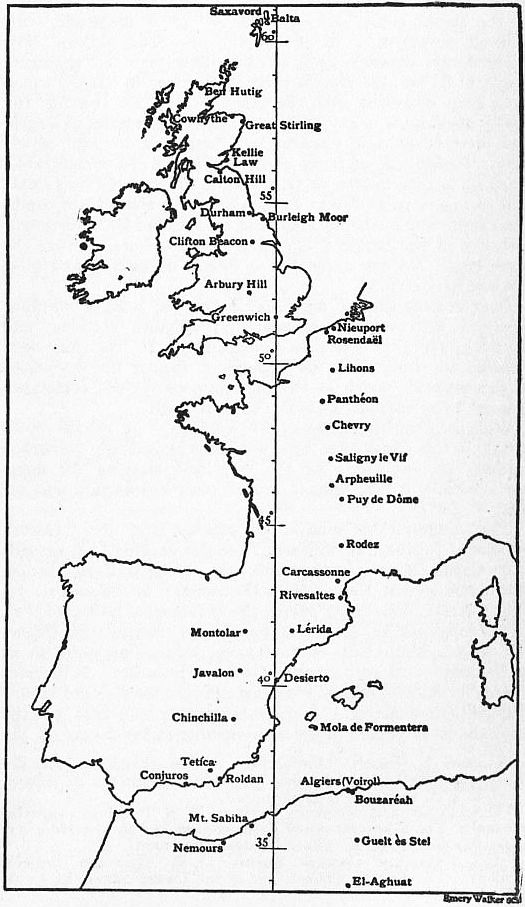

The West Europe-Africa Meridian-arc

Cesar-François Cassini de Thury completed the

Cesar-François Cassini de Thury completed the Cassini map

The Cassini Map or Academy's Map is the first topographic and geometric map made of the Kingdom of France as a whole. It was compiled by the Cassini family, mainly César-François Cassini (Cassini III) and his son Jean-Dominique Cassini (Cas ...

, which was published by his son Cassini IV in 1790. Moreover, the Paris meridian was linked with international collaboration in geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

and metrology

Metrology is the scientific study of measurement. It establishes a common understanding of Unit of measurement, units, crucial in linking human activities. Modern metrology has its roots in the French Revolution's political motivation to stan ...

. Cesar-François Cassini de Thury (1714–1784) expressed the project to extend the French geodetic network all around the world and to connect the Paris and Greenwich observatories. In 1783 the French Academy of Science presented his proposal to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

. This connection and a proposal from General William Roy led to the first triangulation of Great Britain. France and Great Britain surveys' connection was repeated by French astronomers and geodesists in 1787 by Cassini IV, in 1823–1825 by François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries and politician.

Early l ...

and in 1861–1862 by François Perrier.

Between 1792 and 1798 Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

and Jean-Baptiste Delambre surveyed the Paris meridian arc between Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

and Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

(see meridian arc of Delambre and Méchain). They extrapolated from this measurement the distance from the North Pole to the Equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

which was 5,130,740 toises. As the metre had to be equal to one ten-millionth of this distance, it was defined as 0,513074 toises or 443,296 lignes of the Toise of Peru (see below) and of the double-toise N° 1 of the apparatus which had been devised by Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

Borda for this survey at specified temperatures.

In the early 19th century, the Paris meridian's arc was recalculated with greater precision between  In the second half of the 19th century,

In the second half of the 19th century,

In 1994 the Arago Association and the city of Paris commissioned a Dutch conceptual artist, Jan Dibbets, to create a memorial to Arago. Dibbets came up with the idea of setting 135 bronze medallions (although only 121 are documented in the official guide to the medallions) into the ground along the Paris meridian between the northern and southern limits of Paris: a total distance of 9.2 kilometres/5.7 miles. Each medallion is 12 cm in diameter and marked with the name ARAGO plus N and S pointers.

Another project, the Green Meridian (''An 2000 – La Méridienne Verte''), aimed to establish a plantation of trees along the entire length of the

In 1994 the Arago Association and the city of Paris commissioned a Dutch conceptual artist, Jan Dibbets, to create a memorial to Arago. Dibbets came up with the idea of setting 135 bronze medallions (although only 121 are documented in the official guide to the medallions) into the ground along the Paris meridian between the northern and southern limits of Paris: a total distance of 9.2 kilometres/5.7 miles. Each medallion is 12 cm in diameter and marked with the name ARAGO plus N and S pointers.

Another project, the Green Meridian (''An 2000 – La Méridienne Verte''), aimed to establish a plantation of trees along the entire length of the

The Arago medallions on Google Earth

Full Meridian of Glory: Perilous Adventures in the Competition to Measure the Earth

history of science book by Prof. Paul Murdin

The Greenwich Meridian, by Graham Dolan

Named meridians Geography of Paris Geography of France History of Paris Prime meridians Geodesy Metrology Geography of England Geography of Spain Geography of Algeria Paris Observatory

Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

and the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

by the astronomer François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries and politician.

Early l ...

, whose name now appears on the plaques or medallions tracing the route of the meridian through Paris (see below). Biot and Arago published their work as a fourth volume following the three volumes of by Delambre and Méchain's "''Bases du système métrique décimal ou mesure de l'arc méridien compris entre les parallèles de Dunkerque et Barcelone''" (Basis for the decimal metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that standardization, standardizes a set of base units and a nomenclature for describing relatively large and small quantities via decimal-based multiplicative unit prefixes. Though the rules gover ...

or measurement of the meridian arc comprised between Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

and Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

).

In the second half of the 19th century,

In the second half of the 19th century, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, 1st Marquis of Mulhacén, (14 April 1825 – 28 or 29 January 1891) was a Spanish divisional general and geodesist. He represented Spain at the 1875 Conference of the Metre Convention and was the first presid ...

directed the survey of Spain. From 1870 to 1894 the Paris meridan's arc was remeasured by Perrier and Bassot in France and Algeria. In 1879, Ibáñez de Ibero for Spain and François Perrier for France directed the junction of the Spanish geodetic network with Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

. This connection was a remarkable enterprise where triangles with a maximum length of 270 km were observed from mountain stations over the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. The triangulation of France was then connected to those of Great Britain, Spain and Algeria and thus the Paris meridian's arc measurement extended from Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

to the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

.

The fundamental co-ordinates of the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, ), is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, Paris, Latin Quarter (Quartier latin), atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 ...

were also obtained anew, by connecting the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, ), is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, Paris, Latin Quarter (Quartier latin), atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 ...

and the Paris Observatory with the five stations of Bry-sur-Marne, Morlu, Mont Valérien, Chatillon and Montsouris, where the observations of latitude and azimuth were effected.

Geodesy and metrology

In 1860, the Russian Government at the instance ofOtto Wilhelm von Struve

Otto Wilhelm von Struve (May 7, 1819 (Julian calendar: April 25) – April 14, 1905) was a Russian astronomer of Baltic German origins. In Russian, his name is normally given as Otto Vasil'evich Struve (Отто Васильевич Струве). ...

invited the Governments of Belgium, France, Prussia and Britain to connect their triangulations to measure the length of an arc of parallel in latitude 52° and to test the accuracy of the figure and dimensions of the Earth, as derived from the measurements of arc of meridian. To combine the measurements it was necessary to compare the geodetic standards of length used in the different countries. The British Government invited those of France, Belgium, Prussia, Russia, India, Australia, Austria, Spain, United States and Cape of Good Hope to send their standards to the Ordnance Survey

The Ordnance Survey (OS) is the national mapping agency for Great Britain. The agency's name indicates its original military purpose (see Artillery, ordnance and surveying), which was to map Scotland in the wake of the Jacobite rising of ...

office in Southampton. Notably the geodetic standards of France, Spain and United States were based on the metric system, whereas those of Prussia, Belgium and Russia where calibrated against the toise, of which the oldest physical representative was the Toise of Peru. The Toise of Peru had been constructed in 1735 for Bouguer and De La Condamine as their standard of reference in the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator, conducted in what is now Ecuador from 1735 to 1744 in collaboration with the Spanish officers Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre-Guiral (12 January 1716 – 3 July 1795) was a Spanish Navy officer. He spent much of his career in the Spanish America, Americas, where he carried out important scientific work. As a scientist, Ulloa is re ...

.

Alexander Ross Clarke

Alexander Ross Clarke Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (1828–1914) was a British geodesist, primarily remembered for his calculation of the Principal Triangulation of Britain (1858), the calculation of the Figure of the Earth (1858, 1860, ...

and Henry James published the first results of the standards' comparisons in 1867. The same year Russia, Spain and Portugal joined the ''Europäische Gradmessung'' and the General Conference of the association proposed the metre as a uniform length standard for the Arc measurement and recommended the establishment of an International Metre Commission.

The ''Europäische Gradmessung'' decided the creation of an international geodetic standard at the General Conference held in Paris in 1875. The Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

was signed in 1875 in Paris and the International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

was created under the supervision of the International Committee for Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

. The first president of the International Committee for Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

was the Spanish geodesist Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, 1st Marquis of Mulhacén, (14 April 1825 – 28 or 29 January 1891) was a Spanish divisional general and geodesist. He represented Spain at the 1875 Conference of the Metre Convention and was the first presid ...

. He also was the president of the Permanent Commission of the ''Europäische Gradmessung'' from 1874 to 1886. In 1886 the association changed name for the International Geodetic Association (German: ''Internationale Erdmessung'') and Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, 1st Marquis of Mulhacén, (14 April 1825 – 28 or 29 January 1891) was a Spanish divisional general and geodesist. He represented Spain at the 1875 Conference of the Metre Convention and was the first presid ...

was reelected as president. He remained in this position until his death in 1891. During this period the International Geodetic Association gained worldwide importance with the joining of United States, Mexico, Chile, Argentina and Japan. In 1883 the General Conference of the ''Europäische Gradmessung'' proposed to select the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian in the hope that Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

would accede to the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

.

From the Paris meridian to the Greenwich meridian

The United States passed an Act of Congress on 3 August 1882, authorizing PresidentChester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, serving from 1881 to 1885. He was a Republican from New York who previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A. ...

to call an international conference to fix on a common prime meridian for time and longitude throughout the world. Before the invitations were sent out on 1 December, the joint efforts of Abbe, Fleming and William Frederick Allen, Secretary of the US railways' ''General Time Convention'' and Managing Editor of the ''Travellers' Official Guide to the Railways'', had brought the US railway companies to an agreement which led to standard railway time being introduced at noon on 18 November 1883 across the nation. Although this was not legally established until 1918, there was thus a strong sense of ''fait accompli'' that preceded the International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of President of the United State ...

, although setting local times was not part of the remit of the conference.

In 1884, at the International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of President of the United State ...

in Washington DC, the Greenwich meridian was adopted as the prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrarily chosen meridian (geography), meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. On a spheroid, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian ...

of the world. San Domingo, now the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. It shares a Maritime boundary, maritime border with Puerto Rico to the east and ...

, voted against. France and Brazil abstained. The United Kingdom acceded to the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

in 1884 and to the International Geodetic Association in 1898. In 1911, Alexander Ross Clarke

Alexander Ross Clarke Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (1828–1914) was a British geodesist, primarily remembered for his calculation of the Principal Triangulation of Britain (1858), the calculation of the Figure of the Earth (1858, 1860, ...

and Friedrich Robert Helmert

Friedrich Robert Helmert (31 July 1843 – 15 June 1917) was a German geodesist and statistician with important contributions to the theory of errors.

Career

Helmert was born in Freiberg, Kingdom of Saxony. After schooling in Freiberg and ...

stated in the Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

:

In 1891, timetabling for its growing railways led to standardised time in France

Metropolitan France uses Central European Time (''heure d'Europe centrale'', UTC+01:00) as its standard time, and observes Central European Summer Time (''heure d'été d'Europe centrale'', UTC+02:00) from the last Sunday in March to the last ...

changing from mean solar time

Solar time is a calculation of the passage of time based on the position of the Sun in the sky. The fundamental unit of solar time is the day, based on the synodic rotation period. Traditionally, there are three types of time reckoning based ...

of the local centre to that of the Paris meridian: 9 minutes 20.921 seconds ahead of Greenwich Mean Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the local mean time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, counted from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being ...

(GMT). In 1911 the country switched to GMT for timekeeping; in 1914 it switched to the Greenwich meridian for navigation. To this day, French cartographers continue to indicate the Paris meridian on some maps.

From wireless telegraphy to Coordinated Universal Time

With the arrival of wireless telegraphy, France established a transmitter on theEiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower from 1887 to 1889.

Locally nicknamed "''La dame de fe ...

to broadcast a time signal. The creation of the International Time Bureau

The International Time Bureau (, abbreviated BIH), seated at the Paris Observatory, was the international bureau responsible for combining different measurements of Universal Time.

The bureau also played an important role in the research of tim ...

, seated at the Paris Observatory, was decided upon during the 1912 ''Conférence internationale de l'heure radiotélégraphique''. The following year an attempt was made to regulate the international status of the bureau through the creation of an international convention

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of rules, norms, legal customs and standards that states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generally do, obey in their mutual relations. In in ...

. However, the convention wasn't ratified by its member countries due to the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In 1919, after the war, it was decided upon to make the bureau the executive body of the ''International Commission of Time'', one of the commissions of the then newly founded International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; , UAI) is an international non-governmental organization (INGO) with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach, education, and developmen ...

(IAU).

From 1956 until 1987 the International Time Bureau

The International Time Bureau (, abbreviated BIH), seated at the Paris Observatory, was the international bureau responsible for combining different measurements of Universal Time.

The bureau also played an important role in the research of tim ...

was part of the Federation of Astronomical and Geophysical Data Analysis Services (FAGS). In 1987 the bureau's tasks of combining different measurements of Atomic Time

International Atomic Time (abbreviated TAI, from its French name ) is a high-precision atomic coordinate time standard based on the notional passage of proper time on Earth's geoid. TAI is a weighted average of the time kept by over 450 a ...

were taken over by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

(BIPM). Its tasks related to the correction of time with respect to the celestial reference frame

In physics and astronomy, a frame of reference (or reference frame) is an abstract coordinate system, whose origin, orientation, and scale have been specified in physical space. It is based on a set of reference points, defined as geometric ...

and the Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

to realize the Coordinated Universal Time

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) is the primary time standard globally used to regulate clocks and time. It establishes a reference for the current time, forming the basis for civil time and time zones. UTC facilitates international communicat ...

(UTC) were taken over by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service

The International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), formerly the International Earth Rotation Service, is the body responsible for maintaining global time and reference frame standards, notably through its Earth Orientation P ...

(IERS) which was established in its present form in 1987 by the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; , UAI) is an international non-governmental organization (INGO) with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach, education, and developmen ...

and the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics

The International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG; , UGGI) is an international non-governmental organization dedicated to the scientific study of Earth and its space environment using geophysical and geodetic techniques.

The IUGG is a me ...

(IUGG).

The Arago medallions

In 1994 the Arago Association and the city of Paris commissioned a Dutch conceptual artist, Jan Dibbets, to create a memorial to Arago. Dibbets came up with the idea of setting 135 bronze medallions (although only 121 are documented in the official guide to the medallions) into the ground along the Paris meridian between the northern and southern limits of Paris: a total distance of 9.2 kilometres/5.7 miles. Each medallion is 12 cm in diameter and marked with the name ARAGO plus N and S pointers.

Another project, the Green Meridian (''An 2000 – La Méridienne Verte''), aimed to establish a plantation of trees along the entire length of the

In 1994 the Arago Association and the city of Paris commissioned a Dutch conceptual artist, Jan Dibbets, to create a memorial to Arago. Dibbets came up with the idea of setting 135 bronze medallions (although only 121 are documented in the official guide to the medallions) into the ground along the Paris meridian between the northern and southern limits of Paris: a total distance of 9.2 kilometres/5.7 miles. Each medallion is 12 cm in diameter and marked with the name ARAGO plus N and S pointers.

Another project, the Green Meridian (''An 2000 – La Méridienne Verte''), aimed to establish a plantation of trees along the entire length of the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

in France. Several missing Arago medallions appear to have been replaced with the newer 'An 2000 – La Méridienne Verte' markers.

Unfounded speculation

In certain circles, some kind ofoccult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

or esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

significance is ascribed to the Paris meridian; sometimes it is even perceived as a sinister axis. Dominique Stezepfandts, a French conspiracy theorist, attacks the Arago medallions that supposedly trace the route of "an occult geographical line". To him the Paris meridian is a "Masonic axis" or even "the heart of the Devil."

Henry Lincoln, in his book ''The Holy Place'', argued that various ancient structures are aligned according to the Paris meridian. They even include medieval churches, built long before the meridian was established according to conventional history, and Lincoln found it obvious that the meridian "was based upon the 'cromlech

A cromlech (sometimes also spelled "cromleh" or "cromlêh"; cf Welsh ''crom'', "bent"; ''llech'', "slate") is a megalithic construction made of large stone blocks. The word applies to two different megalithic forms in English, the first being a ...

intersect division line'." David Wood, in his book ''Genesis'', likewise ascribes a deeper significance to the Paris meridian and takes it into account when trying to decipher the geometry of the myth-encrusted village of Rennes-le-Château: The meridian passes about 350 metres (1,150 ft) west of the site of the so-called " Poussin tomb," an important location in the legends and esoteric theories relating to that place. A sceptical discussion of these theories, including the supposed alignments, can be found in Bill Putnam and Edwin Wood's book ''The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château – A mystery solved''.

In fiction

The confusion between the Greenwich and the Paris meridians is one of the plot elements of ''Tintin

Tintin usually refers to:

* ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé

** Tintin (character), the protagonist and titular character of the series

Tintin or Tin Tin may also refer to:

Material related to ''The A ...

'' book '' Red Rackham's Treasure''.

The meridian line, dubbed the "Rose Line" by author Dan Brown

Daniel Gerhard Brown (born June 22, 1964) is an American author best known for his Thriller (genre), thriller novels, including the Robert Langdon (book series), Robert Langdon novels ''Angels & Demons'' (2000), ''The Da Vinci Code'' (2003), '' ...

, appeared in the novel ''The Da Vinci Code

''The Da Vinci Code'' is a 2003 mystery thriller novel by Dan Brown. It is “the best-selling American novel of all time.”

Brown's second novel to include the character Robert Langdon—the first was his 2000 novel '' Angels & Demons''� ...

''.

See also

* Cartography of France *Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790)

The Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790) was the geodetic survey to measure the relative position of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Royal Greenwich Observatory and the Paris Observatory via triangulation (surveying), triangulation. The English ...

* Principal Triangulation of Great Britain

The Principal Triangulation of Britain was the first high-precision triangulation survey of the whole of Great Britain and Ireland, carried out between 1791 and 1853 under the auspices of the Board of Ordnance. The aim of the survey was to estab ...

* Meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

* History of geodesy

*History of the metre

During the French Revolution, the traditional units of measure were to be replaced by consistent measures based on natural phenomena. As a base unit of length, scientists had favoured the seconds pendulum (a pendulum with a half-period of ...

*Seconds pendulum

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Principles

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so tha ...

* Struve Geodetic Arc

The Struve Geodetic Arc is a chain of survey triangulations stretching from Hammerfest in Norway to the Black Sea, through ten countries and over , which yielded the first accurate measurement of a meridian arc.

The chain was established ...

References

External links

* {{cite EB1911, wstitle=Earth, Figure of the , last1= Clarke , first1 = Alexander Ross , last2 = Helmert , first2 = Friedrich Robert , volume= 08 , pages = 801–814 Better formatted mathematics atWikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

.

The Arago medallions on Google Earth

Full Meridian of Glory: Perilous Adventures in the Competition to Measure the Earth

history of science book by Prof. Paul Murdin

The Greenwich Meridian, by Graham Dolan

Named meridians Geography of Paris Geography of France History of Paris Prime meridians Geodesy Metrology Geography of England Geography of Spain Geography of Algeria Paris Observatory