Panchatantra on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Panchatantra'' (

The ''Panchatantra'' (

Encyclopaedia Britannica The surviving work is dated to about 200 BCE, but the fables are likely much more ancient. The text's author is unknown, but it has been attributed to

A Javanese version of the Pancatantra

Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 47, No. 1/4 (1966), pp. 59–100 In Laos, a version is called ''Nandaka-prakarana'', while in Thailand it has been referred to as ''Nang Tantrai''.

The Panchatantra

Columbia University archives, Book 1 It is the longest of the five books, making up roughly 45% of the work's length.

The Panchatantra

University of Chicago Press, pages 341-343 The young woman detests his appearance so much that she refuses to even look at him let alone consummate their marriage. One night, while she sleeps in the same bed with her back facing the old man, a thief enters their house. She is scared, turns over, and for security embraces the man. This thrills every limb of the old man. He feels grateful to the thief for making his young wife hold him at last. The aged man rises and profusely thanks the thief, requesting the intruder to take whatever he desires. The third book contains eighteen fables in Ryder translation: Crows and Owls, How the Birds Picked a King, How the Rabbit Fooled the Elephant, The Cat's Judgment, The Brahmin's Goat, The Snake and the Ants, The Snake Who Paid Cash, The Unsocial Swans, The Self-sacrificing Dove, The Old Man with the Young Wife, The Brahmin, the Thief and the Ghost, The Snake in the Prince's Belly, The Gullible Carpenter, Mouse-Maid Made Mouse, The Bird with Golden Dung, The Cave That Talked, The Frog That Rode Snakeback, The Butter-blinded Brahmin. This is about 26% of the total length.

Book five of the text is, like book four, a simpler compilation of moral-filled fables. These also present negative examples with consequences, offering examples and actions for the reader to ponder, avoid, and watch out for. The lessons in this last book include "get facts, be patient, don't act in haste then regret later", "don't build castles in the air". The book five is also unusual in that almost all its characters are humans, unlike the first four where the characters are predominantly anthropomorphized animals. According to Olivelle, it may be that the text's ancient author sought to bring the reader out of the fantasy world of talking and pondering animals into the realities of the human world.

The fifth book contains twelve fables about hasty actions or jumping to conclusions without establishing facts and proper due diligence. In Ryder translation, they are: Ill-considered Action, The Loyal Mongoose, The Four Treasure-Seekers, The Lion-Makers, Hundred-Wit Thousand-Wit and Single-Wit, The Musical Donkey, Slow the Weaver, The Brahman's Dream, The Unforgiving Monkey, The Credulous Fiend, The Three-Breasted Princess, The Fiend Who Washed His Feet.

One of the fables in this book is the story of a woman and a mongoose. She leaves her child with a mongoose friend. When she returns, she sees blood on the mongoose's mouth, and kills the friend, believing the animal killed her child. The woman discovers her child alive, and learns that the blood on the mongoose mouth came from it biting the snake while defending her child from the snake's attack. She regrets having killed the friend because of her hasty action.

Book five of the text is, like book four, a simpler compilation of moral-filled fables. These also present negative examples with consequences, offering examples and actions for the reader to ponder, avoid, and watch out for. The lessons in this last book include "get facts, be patient, don't act in haste then regret later", "don't build castles in the air". The book five is also unusual in that almost all its characters are humans, unlike the first four where the characters are predominantly anthropomorphized animals. According to Olivelle, it may be that the text's ancient author sought to bring the reader out of the fantasy world of talking and pondering animals into the realities of the human world.

The fifth book contains twelve fables about hasty actions or jumping to conclusions without establishing facts and proper due diligence. In Ryder translation, they are: Ill-considered Action, The Loyal Mongoose, The Four Treasure-Seekers, The Lion-Makers, Hundred-Wit Thousand-Wit and Single-Wit, The Musical Donkey, Slow the Weaver, The Brahman's Dream, The Unforgiving Monkey, The Credulous Fiend, The Three-Breasted Princess, The Fiend Who Washed His Feet.

One of the fables in this book is the story of a woman and a mongoose. She leaves her child with a mongoose friend. When she returns, she sees blood on the mongoose's mouth, and kills the friend, believing the animal killed her child. The woman discovers her child alive, and learns that the blood on the mongoose mouth came from it biting the snake while defending her child from the snake's attack. She regrets having killed the friend because of her hasty action.

In the Indian tradition, ''The Panchatantra'' is a . ''Nīti'' can be roughly translated as "the wise conduct of life" and a ''

In the Indian tradition, ''The Panchatantra'' is a . ''Nīti'' can be roughly translated as "the wise conduct of life" and a '' An early Western scholar who studied ''The Panchatantra'' was Dr. Johannes Hertel, who thought the book had a Machiavellian character. Similarly, Edgerton noted that "the so-called 'morals' of the stories have no bearing on morality; they are unmoral, and often immoral. They glorify shrewdness and practical wisdom, in the affairs of life, and especially of politics, of government." Other scholars dismiss this assessment as one-sided, and view the stories as teaching , or proper moral conduct. Also:

According to Olivelle, "Indeed, the current scholarly debate regarding the intent and purpose of the 'Pañcatantra' — whether it supports unscrupulous Machiavellian politics or demands ethical conduct from those holding high office — underscores the rich ambiguity of the text". Konrad Meisig states that the ''Panchatantra'' has been incorrectly represented by some as "an entertaining textbook for the education of princes in the Machiavellian rules of '' Arthasastra''", but instead it is a book for the "Little Man" to develop "Niti" (social ethics, prudent behavior, shrewdness) in their pursuit of ''Artha'', and a work on social satire. According to Joseph Jacobs, "... if one thinks of it, the very ''raison d'être'' of the Fable is to imply its moral without mentioning it."

The Panchatantra, states

An early Western scholar who studied ''The Panchatantra'' was Dr. Johannes Hertel, who thought the book had a Machiavellian character. Similarly, Edgerton noted that "the so-called 'morals' of the stories have no bearing on morality; they are unmoral, and often immoral. They glorify shrewdness and practical wisdom, in the affairs of life, and especially of politics, of government." Other scholars dismiss this assessment as one-sided, and view the stories as teaching , or proper moral conduct. Also:

According to Olivelle, "Indeed, the current scholarly debate regarding the intent and purpose of the 'Pañcatantra' — whether it supports unscrupulous Machiavellian politics or demands ethical conduct from those holding high office — underscores the rich ambiguity of the text". Konrad Meisig states that the ''Panchatantra'' has been incorrectly represented by some as "an entertaining textbook for the education of princes in the Machiavellian rules of '' Arthasastra''", but instead it is a book for the "Little Man" to develop "Niti" (social ethics, prudent behavior, shrewdness) in their pursuit of ''Artha'', and a work on social satire. According to Joseph Jacobs, "... if one thinks of it, the very ''raison d'être'' of the Fable is to imply its moral without mentioning it."

The Panchatantra, states

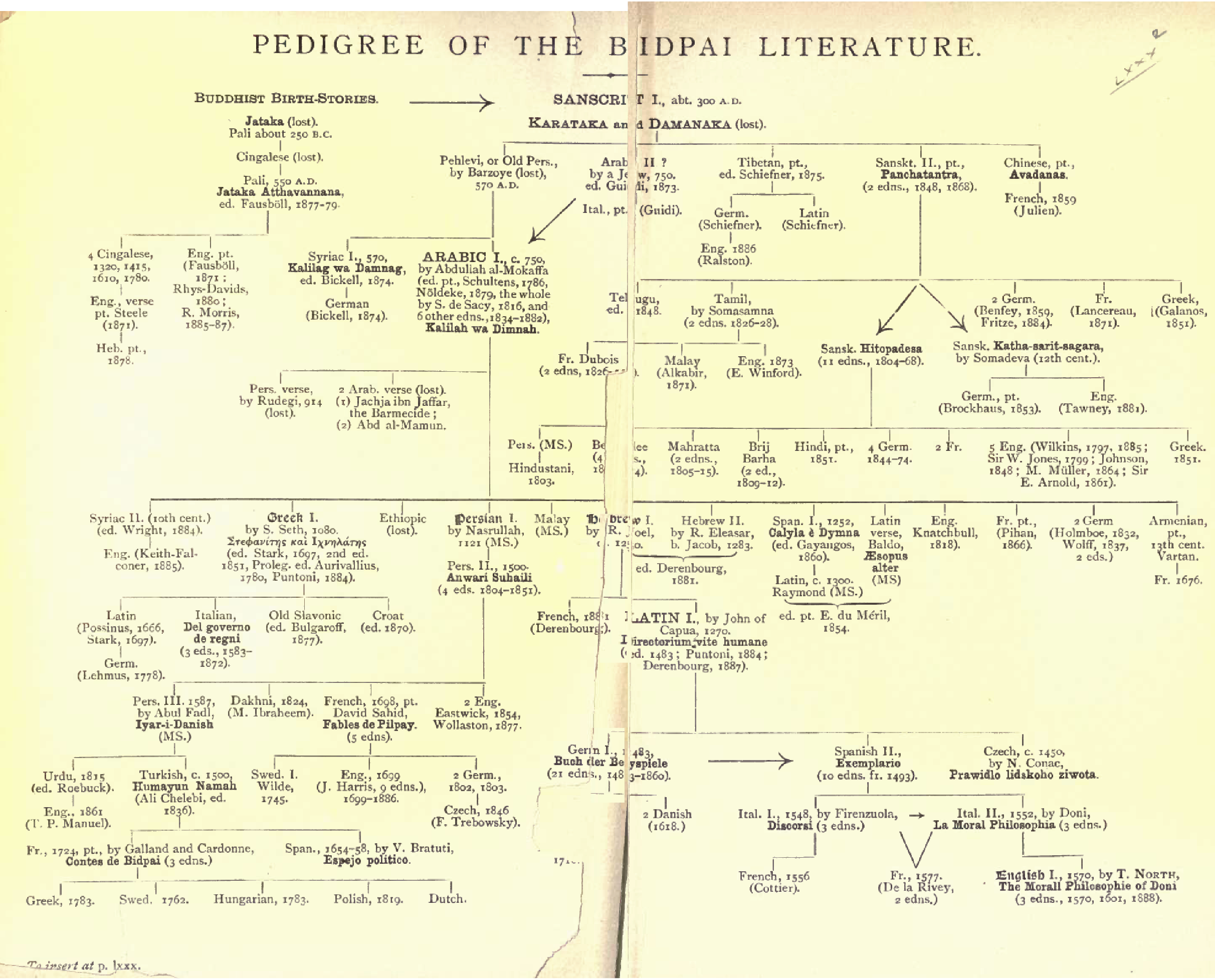

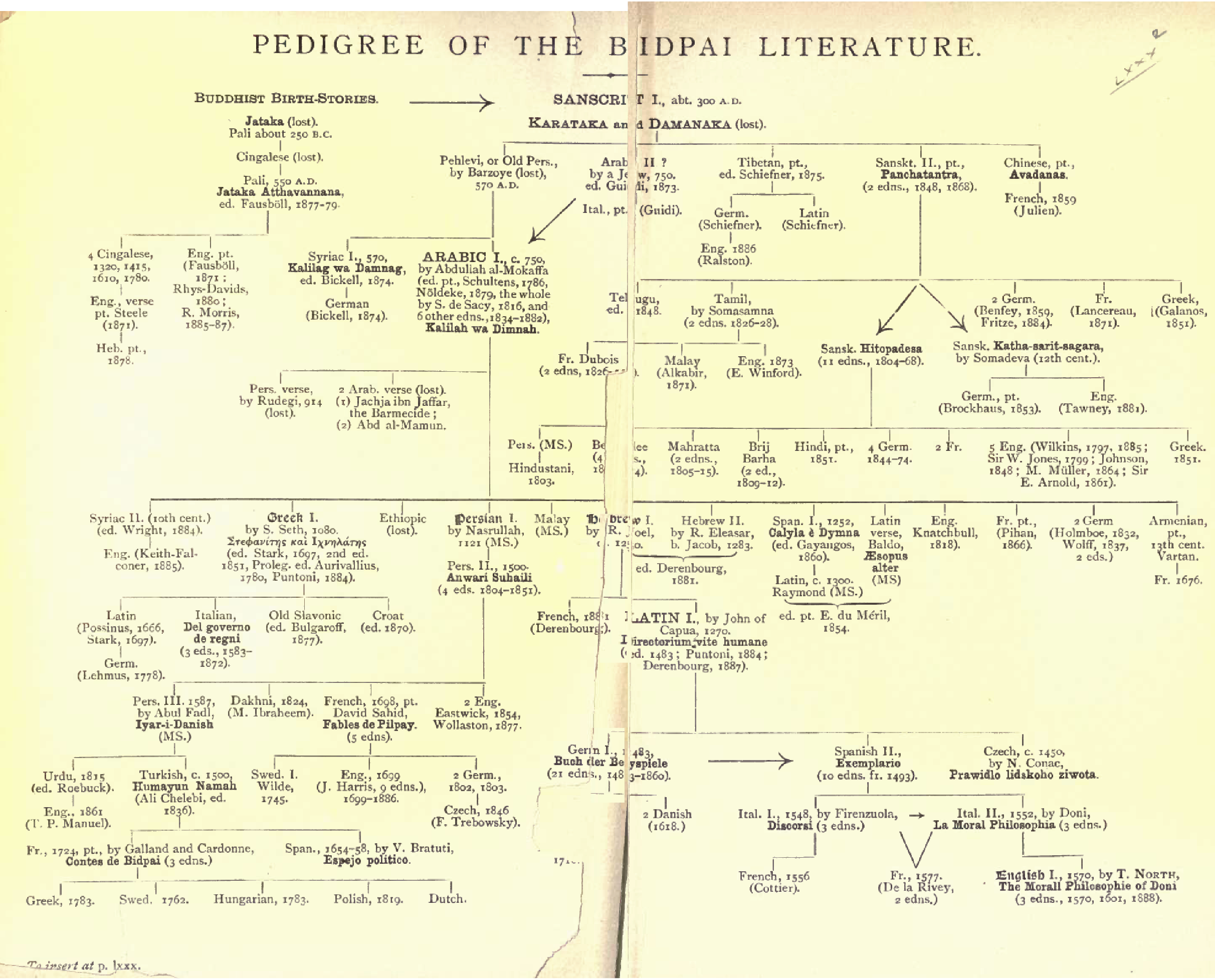

The work has gone through many different versions and translations from the sixth century to the present day. The original Indian version was first translated into a foreign language ( Pahlavi) by Borzūya in 570CE, then into Arabic in 750. This Arabic version was translated into several languages, including Syriac, Greek, Persian, Hebrew and Spanish, and thus became the source of versions in European languages, until the English translation by Charles Wilkins of the

The work has gone through many different versions and translations from the sixth century to the present day. The original Indian version was first translated into a foreign language ( Pahlavi) by Borzūya in 570CE, then into Arabic in 750. This Arabic version was translated into several languages, including Syriac, Greek, Persian, Hebrew and Spanish, and thus became the source of versions in European languages, until the English translation by Charles Wilkins of the

The ''Panchatantra'' also migrated into the Middle East, through

The ''Panchatantra'' also migrated into the Middle East, through

KALILA WA DEMNA i. Redactions and circulation

Encyclopaedia Iranica Around 550 CE his notable physician Borzuy (Burzuwaih) translated the work from Sanskrit into the Pahlavi (

Borzuy's translation of the Sanskrit version into Pahlavi arrived in Persia by the 6th century, but this Middle Persian version is now lost. The book had become popular in Sassanid, and was translated into Syriac and Arabic whose copies survive. According to Riedel, "the three preserved New Persian translations originated between the 10th and 12th century", and are based on the 8th-century Arabic translation by Ibn al-Muqaffa of Borzuy's work on ''Panchatantra''. It is the 8th-century ''Kalila wa Demna'' text, states Riedel, that has been the most influential of the known Arabic versions, not only in the Middle East, but also through its translations into Greek, Hebrew and Old Spanish.

The Persian

Borzuy's translation of the Sanskrit version into Pahlavi arrived in Persia by the 6th century, but this Middle Persian version is now lost. The book had become popular in Sassanid, and was translated into Syriac and Arabic whose copies survive. According to Riedel, "the three preserved New Persian translations originated between the 10th and 12th century", and are based on the 8th-century Arabic translation by Ibn al-Muqaffa of Borzuy's work on ''Panchatantra''. It is the 8th-century ''Kalila wa Demna'' text, states Riedel, that has been the most influential of the known Arabic versions, not only in the Middle East, but also through its translations into Greek, Hebrew and Old Spanish.

The Persian  The introduction of the first book of ''Kalila wa Demna'' is different from ''Panchatantra'', in being more elaborate and instead of king and his three sons studying in the Indian version, the Persian version speaks of a merchant and his three sons who had squandered away their father's wealth. The Persian version also makes an abrupt switch from the story of the three sons to an injured ox, and thereafter parallels the ''Panchatantra''.

The two jackals' names transmogrified into Kalila and Dimna in the Persian version. Perhaps because the first section constituted most of the work, or because translators could find no simple equivalent in Zoroastrian Pahlavi for the concept expressed by the Sanskrit word 'Panchatantra', the jackals' names, ''Kalila and Dimna,'' became the generic name for the entire work in classical times.

After the first chapter, Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ inserted a new one, telling of Dimna's trial. The jackal is suspected of instigating the death of the bull "Shanzabeh", a key character in the first chapter. The trial lasts for two days without conclusion, until a tiger and leopard appear to bear witness against Dimna. He is found guilty and put to death.

Ibn al-Muqaffa' inserted other additions and interpretations into his 750CE "re-telling" (see Francois de Blois' Burzōy's voyage to India and the origin of the book ''Kalīlah wa Dimnah''). The political theorist Jennifer London suggests that he was expressing risky political views in a metaphorical way. (Al-Muqaffa' was murdered within a few years of completing his manuscript). London has analysed how Ibn al-Muqaffa' could have used his version to make "frank political expression" at the 'Abbasid court (see J. London's "How To Do Things With Fables: Ibn al-Muqaffa''s Frank Speech in Stories from Kalila wa Dimna," ''History of Political Thought'' XXIX: 2 (2008)).

The introduction of the first book of ''Kalila wa Demna'' is different from ''Panchatantra'', in being more elaborate and instead of king and his three sons studying in the Indian version, the Persian version speaks of a merchant and his three sons who had squandered away their father's wealth. The Persian version also makes an abrupt switch from the story of the three sons to an injured ox, and thereafter parallels the ''Panchatantra''.

The two jackals' names transmogrified into Kalila and Dimna in the Persian version. Perhaps because the first section constituted most of the work, or because translators could find no simple equivalent in Zoroastrian Pahlavi for the concept expressed by the Sanskrit word 'Panchatantra', the jackals' names, ''Kalila and Dimna,'' became the generic name for the entire work in classical times.

After the first chapter, Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ inserted a new one, telling of Dimna's trial. The jackal is suspected of instigating the death of the bull "Shanzabeh", a key character in the first chapter. The trial lasts for two days without conclusion, until a tiger and leopard appear to bear witness against Dimna. He is found guilty and put to death.

Ibn al-Muqaffa' inserted other additions and interpretations into his 750CE "re-telling" (see Francois de Blois' Burzōy's voyage to India and the origin of the book ''Kalīlah wa Dimnah''). The political theorist Jennifer London suggests that he was expressing risky political views in a metaphorical way. (Al-Muqaffa' was murdered within a few years of completing his manuscript). London has analysed how Ibn al-Muqaffa' could have used his version to make "frank political expression" at the 'Abbasid court (see J. London's "How To Do Things With Fables: Ibn al-Muqaffa''s Frank Speech in Stories from Kalila wa Dimna," ''History of Political Thought'' XXIX: 2 (2008)).

Borzuy's 570 CE Pahlavi translation (''Kalile va Demne'', now lost) was translated into Syriac. Nearly two centuries later, it was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa around 750 CE under the Arabic title, ''Kalīla wa Dimna''. After the Arab invasion of Persia (Iran), Ibn al-Muqaffa's version (two languages removed from the pre-Islamic Sanskrit original) emerged as the pivotal surviving text that enriched world literature. Ibn al-Muqaffa's work is considered a model of the finest Arabic prose style, and "is considered the first masterpiece of Arabic literary prose."

Some scholars believe that Ibn al-Muqaffa's translation of the second section, illustrating the Sanskrit principle of ''Mitra Laabha'' (Gaining Friends), became the unifying basis for the

Borzuy's 570 CE Pahlavi translation (''Kalile va Demne'', now lost) was translated into Syriac. Nearly two centuries later, it was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa around 750 CE under the Arabic title, ''Kalīla wa Dimna''. After the Arab invasion of Persia (Iran), Ibn al-Muqaffa's version (two languages removed from the pre-Islamic Sanskrit original) emerged as the pivotal surviving text that enriched world literature. Ibn al-Muqaffa's work is considered a model of the finest Arabic prose style, and "is considered the first masterpiece of Arabic literary prose."

Some scholars believe that Ibn al-Muqaffa's translation of the second section, illustrating the Sanskrit principle of ''Mitra Laabha'' (Gaining Friends), became the unifying basis for the

History of the Migration of ''Panchatantra''

, Institute for Oriental Study, Thane The Latin version was translated into Italian by Antonfrancesco Doni in 1552. This translation became the basis for the first English translation, in 1570: Sir Thomas North translated it into Elizabethan English as ''The Fables of Bidpai: The Morall Philosophie of Doni'' (reprinted by Joseph Jacobs, 1888). La Fontaine published ''The Fables of Bidpai'' in 1679, based on "the Indian sage Pilpay".

II and IIIIV and V

* * * * * * (reprinting in Devanagari only the text from his 1924 work) ;Others *

Google Books

* (Text with Sanskrit commentary) * (Complete Sanskrit text with Hindi translation)

Columbia University archives; (Translation based on Hertel's text of Purnabhadra's Recension of 1199 CE.) * (reprint: 1995) (Translation based on Hertel manuscript.) * (Translation based on Edgerton manuscript.) * (Accessible popular compilation derived from a Sanskrit text with reference to the aforementioned translations by Chandra Rajan and Patrick Olivelle.) * ;Kalila and Dimna, Fables of Bidpai and other texts *

Google Books

https://books.google.com/books?id=aGIUAAAAQAAJ Google Books] (translated from Silvestre de Stacy's 1816 collation of different Arabic manuscripts) * Also online a

Persian Literature in Translation

* * , reprinted by Philo Press, Amsterdam 1970 *

Google Books

(edited and induced from ''The Morall Philosophie of Doni'' by Sir Thomas North, 1570) *''Tales Within Tales'' – adapted from the fables of Pilpai, Sir Arthur N Wollaston, John Murray, London 1909 * * * *

Appendix I: pp. 207–242

als

*Ferial Ghazoul (1983)

Poetic Logic in The Panchatantra and The Arabian Nights

Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Winter 1983), pp. 13–21 *''Burzoy's Voyage to India and the Origin of the Book of Kalilah wa Dimnah'

Google Books

Francois de Blois, Royal Asiatic Society, London, 1990 *''On Kalila wa Dimna and Persian National Fairy Tales'

Transoxiana.com

Dr. Pavel Basharin oscow Tansoxiana 12, 2007 *''The Past We Share — The Near Eastern Ancestry of Western Folk Literature'', E. L. Ranelagh, Quartet Books, Horizon Press, New York, 1979 *''In Arabian Nights — A Search of Morocco through its Stories and Storytellers'' by Tahir Shah, Doubleday, 2008. *Ibn al-Muqaffa, Abdallah. ''Kalilah et Dimnah''. Ed. P. Louis Cheiko. 3 ed. Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1947. *Ibn al-Muqaffa, Abd'. ''Calila e Dimna''. Edited by Juan Manuel Cacho Blecua and María Jesus Lacarra. Madrid: Editorial Castalia, 1984. *Keller, John Esten, and Robert White Linker. ''El libro de Calila e Digna''. Madrid Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1967. *Latham, J.D. "Ibn al-Muqaffa' and Early 'Abbasid Prose." Abbasid Belles-Lettres''. Eds. Julia Ashtiany, et al. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989. 48–77. *Parker, Margaret. ''The Didactic Structure and Content of El libro de Calila e Digna''. Miami, FL: Ediciones Universal, 1978. *Penzol, Pedro. Las traducciones del "Calila e Dimna". Madrid,: Impr. de Ramona Velasco, viuda de P. Perez,, 1931. *Shaw, Sandra. ''The Jatakas — Birth Stories of the Bodhisatta'', Penguin Classics, Penguin Books India, New Delhi, 2006 *Wacks, David A. "The Performativity of Ibn al-Muqaffa''s ''Kalîla wa-Dimna'' and ''Al-Maqamat al-Luzumiyya'' of al-Saraqusti," ''Journal of Arabic Literature'' 34.1–2 (2003): 178–89.

The ''Panchatantra'' (

The ''Panchatantra'' (IAST

The International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST) is a transliteration scheme that allows the lossless romanisation of Indic scripts as employed by Sanskrit and related Indic languages. It is based on a scheme that emerged during ...

: Pañcatantra, ISO: Pañcatantra, sa, पञ्चतन्त्र, "Five Treatises") is an ancient Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

collection of interrelated animal fables in Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

verse and prose, arranged within a frame story.Panchatantra: Indian LiteratureEncyclopaedia Britannica The surviving work is dated to about 200 BCE, but the fables are likely much more ancient. The text's author is unknown, but it has been attributed to

Vishnu Sharma

Sharma ( Sanskrit: विष्णुशर्मन् / विष्णुशर्मा) was an Indian scholar and author who wrote the '' Panchatantra'', a collection of fables.

Works

Panchatantra is one of the most widely translated non- ...

in some recensions and Vasubhaga in others, both of which may be fictitious pen names. It is likely a Hindu text, and based on older oral traditions with "animal fables that are as old as we are able to imagine".

It is "certainly the most frequently translated literary product of India", and these stories are among the most widely known in the world. It goes by many names in many cultures. There is a version of ''Panchatantra'' in nearly every major language of India, and in addition there are 200 versions of the text in more than 50 languages around the world. One version reached Europe in the 11th century. To quote :

The earliest known translation into a non-Indian language is in Middle Persian

Middle Persian or Pahlavi, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg () in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle P ...

(Pahlavi, 550 CE) by Burzoe. This became the basis for a Syriac translation as ''Kalilag and Damnag'' and a translation into Arabic in 750 CE by Persian scholar Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa as '' Kalīlah wa Dimnah''. A New Persian

New Persian ( fa, فارسی نو), also known as Modern Persian () and Dari (), is the current stage of the Persian language spoken since the 8th to 9th centuries until now in Greater Iran and surroundings. It is conventionally divided into thr ...

version by Rudaki

Rudaki (also spelled Rodaki; fa, رودکی; 858 – 940/41) was a Persian poet, singer and musician, who served as a court poet under the Samanids. He is regarded as the first major poet to write in New Persian. Said to have composed more tha ...

, from the 3rd century Hijri, became known as ''Kalīleh o Demneh''. Rendered in prose by Abu'l-Ma'ali Nasrallah Monshi in 1143 CE, this was the basis of Kashefi's 15th-century ''Anvār-i Suhaylī'' (The Lights of Canopus), which in turn was translated into ''Humayun-namah'' in Turkish. The book is also known as ''The Fables of Bidpai'' (or Pilpai in various European languages, Vidyapati in Sanskrit) or ''The Morall Philosophie of Doni'' (English, 1570). Most European versions of the text are derivative works of the 12th-century Hebrew version of ''Panchatantra'' by Rabbi Joel. In Germany, its translation in 1480 by has been widely read. Several versions of the text are also found in Indonesia, where it is titled as ''Tantri Kamandaka'', ''Tantravakya'' or ''Candapingala'' and consists of 360 fables.A. Venkatasubbiah (1966)A Javanese version of the Pancatantra

Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 47, No. 1/4 (1966), pp. 59–100 In Laos, a version is called ''Nandaka-prakarana'', while in Thailand it has been referred to as ''Nang Tantrai''.

Author and chronology

The prelude section of the ''Panchatantra'' identifies an octogenarianBrahmin

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests ( purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers ( ...

named Vishnusharma (IAST

The International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST) is a transliteration scheme that allows the lossless romanisation of Indic scripts as employed by Sanskrit and related Indic languages. It is based on a scheme that emerged during ...

: Viṣṇuśarman) as its author. He is stated to be teaching the principles of good government to three princes of Amarasakti. It is unclear, states Patrick Olivelle

Patrick Olivelle is an Indologist. A philologist and scholar of Sanskrit Literature whose work has focused on asceticism, renunciation and the dharma, Olivelle has been Professor of Sanskrit and Indian Religions in the Department of Asian Stu ...

, a professor of Sanskrit and Indian religions, if Vishnusharma was a real person or himself a literary invention. Some South Indian recensions of the text, as well as Southeast Asian versions of ''Panchatantra'' attribute the text to Vasubhaga, states Olivelle. Based on the content and mention of the same name in other texts dated to ancient and medieval era centuries, most scholars agree that Vishnusharma is a fictitious name. Olivelle and other scholars state that regardless of who the author was, it is likely "the author was a Hindu, and not a Buddhist, nor Jain", but it is unlikely that the author was a devotee of Hindu god Vishnu

Vishnu ( ; , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Vishnu is known as "The Preserver" withi ...

because the text neither expresses any sentiments against other Hindu deities such as Shiva

Shiva (; sa, शिव, lit=The Auspicious One, Śiva ), also known as Mahadeva (; Help:IPA/Sanskrit, ɐɦaːd̪eːʋɐ, or Hara, is one of the Hindu deities, principal deities of Hinduism. He is the Supreme Being in Shaivism, one o ...

, Indra

Indra (; Sanskrit: इन्द्र) is the king of the devas (god-like deities) and Svarga (heaven) in Hindu mythology. He is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war. volumes/ref> I ...

and others, nor does it avoid invoking them with reverence.

Various locations where the text was composed have been proposed but this has been controversial. Some of the proposed locations include Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, Southwestern or South India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, as well as the union terr ...

. The text's original language was likely Sanskrit. Though the text is now known as ''Panchatantra'', the title found in old manuscript versions varies regionally, and includes names such as ''Tantrakhyayika'', ''Panchakhyanaka'', ''Panchakhyana'' and ''Tantropakhyana''. The suffix ''akhyayika'' and ''akhyanaka'' mean "little story" or "little story book" in Sanskrit.

The text was translated into Pahlavi in 550 CE, which forms the latest limit of the text's existence. The earliest limit is uncertain. It quotes identical verses from ''Arthasastra'', which is broadly accepted to have been completed by the early centuries of the common era. According to Olivelle, "the current scholarly consensus places the ''Panchatantra'' around 300 CE, although we should remind ourselves that this is only an educated guess". The text quotes from older genre of Indian literature, and legends with anthropomorphic animals are found in more ancient texts dated to the early centuries of the 1st millennium BCE such as the chapter 4.1 of the ''Chandogya Upanishad

The ''Chandogya Upanishad'' (Sanskrit: , IAST: ''Chāndogyopaniṣad'') is a Sanskrit text embedded in the Chandogya Brahmana of the Sama Veda of Hinduism.Patrick Olivelle (2014), ''The Early Upanishads'', Oxford University Press; , pp. 166- ...

''. According to Gillian Adams, Panchatantra may be a product of the Vedic period

The Vedic period, or the Vedic age (), is the period in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of the history of India when the Vedic literature, including the Vedas (ca. 1300–900 BCE), was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent, betwe ...

, but its age cannot be ascertained with confidence because "the original Sanskrit version has been lost".

Content

The ''Panchatantra'' is a series of inter-woven fables, many of which deploy metaphors ofanthropomorphized

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. It is considered to be an innate tendency of human psychology.

Personification is the related attribution of human form and characteristics t ...

animals with human virtues and vices. Its narrative illustrates, for the benefit of three ignorant princes, the central Hindu principles of ''nīti''. While ''nīti'' is hard to translate, it roughly means prudent worldly conduct, or "the wise conduct of life"., Translator's introduction: "The ''Panchatantra'' is a ''niti-shastra'', or textbook of ''niti''. The word ''niti'' means roughly "the wise conduct of life." No precise equivalent of the term is found in English, French, Latin, or Greek. Many words are therefore necessary to explain what ''niti'' is, though the idea, once grasped, is clear, important, and satisfying."

Apart from a short introduction, it consists of five parts. Each part contains a main story, called the frame story, which in turn contains several embedded stories, as one character narrates a story to another. Often these stories contain further embedded stories. The stories operate like a succession of Russian dolls, one narrative opening within another, sometimes three or four deep. Besides the stories, the characters also quote various epigrammatic verses to make their point.

The five books have their own subtitles.

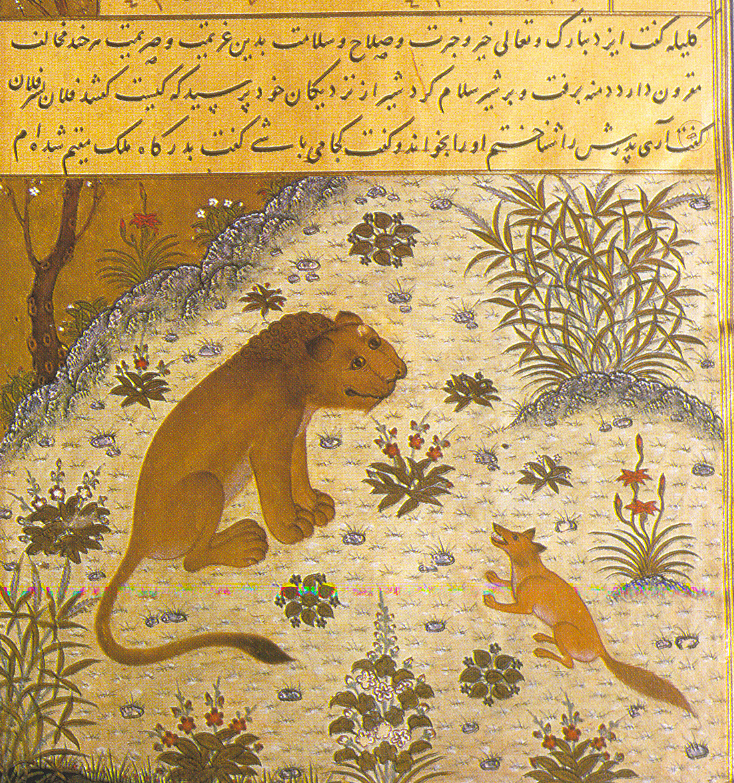

Book 1: ''Mitra-bheda''

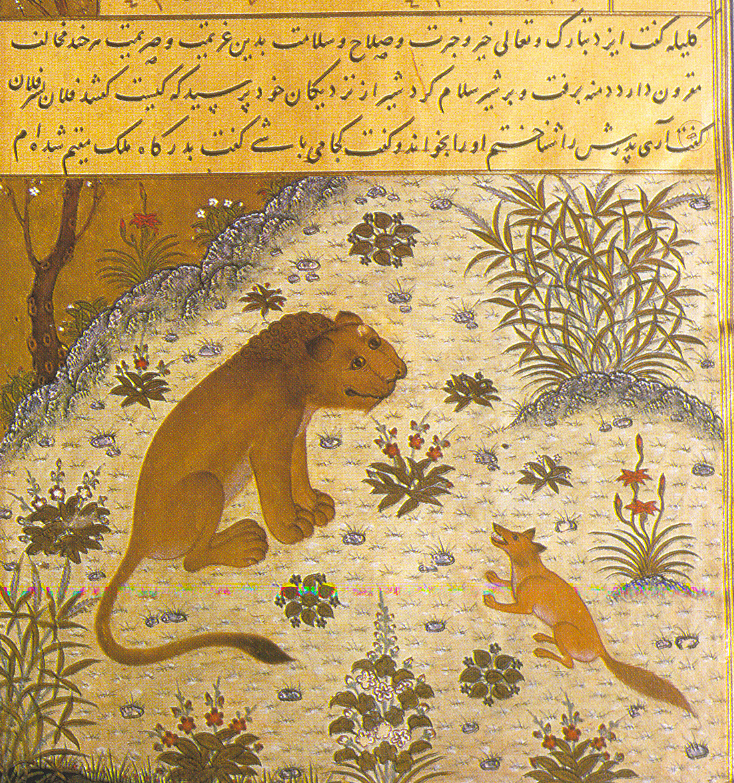

The first treatise features a jackal named Damanaka, as the unemployed minister in a kingdom ruled by a lion. He, along with his moralizing sidekick named Karataka, conspire to break up alliances and friendships of the lion king. A series of fables describe the conspiracies and causes that lead to close and inseparable friends breaking up. The Book 1 contains over thirty fables, with the version Arthur Ryder translated containing 34: The Loss of Friends, The Wedge-Pulling Monkey, The Jackal and the War-Drum, Merchant Strong-Tooth, Godly and June, The Jackal at the Ram-Fight, The Weaver's Wife, How the Crow-Hen Killed the Black Snake, The Heron that Liked Crab-Meat, Numskull and the Rabbit, The Weaver Who Loved a Princess, The Ungrateful Man, Leap and Creep, The Blue Jackal, Passion and the Owl, Ugly's Trust Abused, The Lion and the Carpenter, The Plover Who Fought the Ocean, Shell-Neck Slim and Grim, Forethought Readywit and Fatalist, The Duel Between Elephant and Sparrow, The Shrewd Old Gander, The Lion and the Ram, Smart the Jackal, The Monk Who Left His Body Behind, The Girl Who Married a Snake, Poor Blossom, The Unteachable Monkey, Right-Mind and Wrong-Mind, A Remedy Worse than the Disease, The Mice That Ate Iron, The Results of Education, The Sensible Enemy, The Foolish Friend.Arthur Ryder (1925)The Panchatantra

Columbia University archives, Book 1 It is the longest of the five books, making up roughly 45% of the work's length.

Book 2: ''Mitra-samprāpti''

The second treatise is quite different in structure than the remaining books, states Olivelle, as it does not truly embed fables. It is a collection of adventures of four characters: a crow (scavenger, not a predator, airborne habits), a mouse (tiny, underground habits), a turtle (slow, water habits) and a deer (a grazing animal viewed by other animals as prey, land habits). The overall focus of the book is the reverse of the first book. Its theme is to emphasize the importance of friendships, team work, and alliances. It teaches, "weak animals with very different skills, working together can accomplish what they cannot when they work alone", according to Olivelle. United through their cooperation and in their mutual support, the fables describe how they are able to outwit all external threats and prosper. The second book contains ten fables: The Winning of Friends, The Bharunda Birds, Gold's Gloom, Mother Shandilee's Bargain, Self-defeating Forethought, Mister Duly, Soft, the Weaver, Hang-Ball and Greedy, The Mice That Set Elephant Free, Spot's Captivity. Book 2 makes up about 22% of the total length.Book 3: ''Kākolūkīyam''

The third treatise discusses war and peace, presenting through animal characters a moral about the battle of wits being a strategic means to neutralize a vastly superior opponent's army. The thesis in this treatise is that a battle of wits is a more potent force than a battle of swords. The choice of animals embeds a metaphor of a war between good versus evil, and light versus darkness. Crows are good, weaker and smaller in number and are creatures of the day (light), while owls are presented as evil, numerous and stronger creatures of the night (darkness). The crow king listens to the witty and wise counsel of Ciramjivin, while the owl king ignores the counsel of Raktaksa. The good crows win. The fables in the third book, as well as others, do not strictly limit to matters of war and peace. Some present fables that demonstrate how different characters have different needs and motives, which is subjectively rational from each character's viewpoint, and that addressing these needs can empower peaceful relationships even if they start off in a different way. For example, in the fable ''The Old Man the Young Wife'', the text relates a story wherein an old man marries a young woman from a penniless family.Arthur William Ryder (1925)The Panchatantra

University of Chicago Press, pages 341-343 The young woman detests his appearance so much that she refuses to even look at him let alone consummate their marriage. One night, while she sleeps in the same bed with her back facing the old man, a thief enters their house. She is scared, turns over, and for security embraces the man. This thrills every limb of the old man. He feels grateful to the thief for making his young wife hold him at last. The aged man rises and profusely thanks the thief, requesting the intruder to take whatever he desires. The third book contains eighteen fables in Ryder translation: Crows and Owls, How the Birds Picked a King, How the Rabbit Fooled the Elephant, The Cat's Judgment, The Brahmin's Goat, The Snake and the Ants, The Snake Who Paid Cash, The Unsocial Swans, The Self-sacrificing Dove, The Old Man with the Young Wife, The Brahmin, the Thief and the Ghost, The Snake in the Prince's Belly, The Gullible Carpenter, Mouse-Maid Made Mouse, The Bird with Golden Dung, The Cave That Talked, The Frog That Rode Snakeback, The Butter-blinded Brahmin. This is about 26% of the total length.

Book 4: ''Labdh''

The book four of the ''Panchatantra'' is a simpler compilation of ancient moral-filled fables. These, states Olivelle, teach messages such as "a bird in hand is worth two in the bush". They caution the reader to avoid succumbing to peer pressure and cunning intent wrapped in soothing words. The book is different from the first three, in that the earlier books give positive examples of ethical behavior offering examples and actions "to do". In contrast, book four presents negative examples with consequences, offering examples and actions "to avoid, to watch out for". The fourth book contains thirteen fables in Ryder translation: Loss of Gains, The Monkey and the Crocodile, Handsome and Theodore, Flop-Ear and Dusty, The Potter Militant, The Jackal Who Killed No Elephants, The Ungrateful Wife, King Joy and Secretary Splendor, The Ass in the Tiger-Skin, The Farmer's Wife, The Pert Hen-Sparrow, How Supersmart Ate the Elephant, The Dog Who Went Abroad. Book 4, along with Book 5, is very short. Together the last two books constitute about 7% of the total text.Book 5: ''Aparīkṣitakārakaṃ''

Book five of the text is, like book four, a simpler compilation of moral-filled fables. These also present negative examples with consequences, offering examples and actions for the reader to ponder, avoid, and watch out for. The lessons in this last book include "get facts, be patient, don't act in haste then regret later", "don't build castles in the air". The book five is also unusual in that almost all its characters are humans, unlike the first four where the characters are predominantly anthropomorphized animals. According to Olivelle, it may be that the text's ancient author sought to bring the reader out of the fantasy world of talking and pondering animals into the realities of the human world.

The fifth book contains twelve fables about hasty actions or jumping to conclusions without establishing facts and proper due diligence. In Ryder translation, they are: Ill-considered Action, The Loyal Mongoose, The Four Treasure-Seekers, The Lion-Makers, Hundred-Wit Thousand-Wit and Single-Wit, The Musical Donkey, Slow the Weaver, The Brahman's Dream, The Unforgiving Monkey, The Credulous Fiend, The Three-Breasted Princess, The Fiend Who Washed His Feet.

One of the fables in this book is the story of a woman and a mongoose. She leaves her child with a mongoose friend. When she returns, she sees blood on the mongoose's mouth, and kills the friend, believing the animal killed her child. The woman discovers her child alive, and learns that the blood on the mongoose mouth came from it biting the snake while defending her child from the snake's attack. She regrets having killed the friend because of her hasty action.

Book five of the text is, like book four, a simpler compilation of moral-filled fables. These also present negative examples with consequences, offering examples and actions for the reader to ponder, avoid, and watch out for. The lessons in this last book include "get facts, be patient, don't act in haste then regret later", "don't build castles in the air". The book five is also unusual in that almost all its characters are humans, unlike the first four where the characters are predominantly anthropomorphized animals. According to Olivelle, it may be that the text's ancient author sought to bring the reader out of the fantasy world of talking and pondering animals into the realities of the human world.

The fifth book contains twelve fables about hasty actions or jumping to conclusions without establishing facts and proper due diligence. In Ryder translation, they are: Ill-considered Action, The Loyal Mongoose, The Four Treasure-Seekers, The Lion-Makers, Hundred-Wit Thousand-Wit and Single-Wit, The Musical Donkey, Slow the Weaver, The Brahman's Dream, The Unforgiving Monkey, The Credulous Fiend, The Three-Breasted Princess, The Fiend Who Washed His Feet.

One of the fables in this book is the story of a woman and a mongoose. She leaves her child with a mongoose friend. When she returns, she sees blood on the mongoose's mouth, and kills the friend, believing the animal killed her child. The woman discovers her child alive, and learns that the blood on the mongoose mouth came from it biting the snake while defending her child from the snake's attack. She regrets having killed the friend because of her hasty action.

Links with other fables

The fables of ''Panchatantra'' are found in numerous world languages. It is also considered partly the origin of European secondary works, such as folk tale motifs found in Boccaccio, La Fontaine and the works ofGrimm Brothers

The Brothers Grimm ( or ), Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), were a brother duo of German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers, and authors who together collected and published folklore. They are among t ...

. For a while, this had led to the hypothesis that popular worldwide animal-based fables had origins in India and the Middle East. According to Max Muller,

This monocausal hypothesis has now been generally discarded in favor of polygenetic hypothesis which states that fable motifs had independent origins in many ancient human cultures, some of which have common roots and some influenced by co-sharing of fables. The shared fables implied morals that appealed to communities separated by large distances and these fables were therefore retained, transmitted over human generations with local variations. However, many post-medieval era authors explicitly credit their inspirations to texts such as "Bidpai" and "Pilpay, the Indian sage" that are known to be based on the ''Panchatantra''.

According to Niklas Bengtsson, even though India being the exclusive original source of fables is no longer taken seriously, the ancient classic ''Panchatantra'', "which new folklore research continues to illuminate, was certainly the first work ever written down for children, and this in itself means that the Indian influence has been enormous n world literature not only on the genres of fables and fairy tales, but on those genres as taken up in children's literature". According to Adams and Bottigheimer, the fables of ''Panchatantra'' are known in at least 38 languages around the world in 112 versions by Jacob's old estimate, and its relationship with Mesopotamian and Greek fables is hotly debated in part because the original manuscripts of all three ancient texts have not survived. Olivelle states that there are 200 versions of the text in more than 50 languages around the world, in addition to a version in nearly every major language of India.

Scholars have noted the strong similarity between a few of the stories in ''The Panchatantra'' and '' Aesop's Fables''. Examples are '' The Ass in the Panther's Skin'' and '' The Ass without Heart and Ears''.''The Panchatantra'' translated in 1924 from the Sanskrit by Franklin Edgerton, George Allen and Unwin, London 1965 ("Edition for the General Reader"), page 13 ''The Broken Pot'' is similar to Aesop's '' The Milkmaid and Her Pail'', ''The Gold-Giving Snake'' is similar to Aesop's ''The Man and the Serpent'' and ''Le Paysan et Dame serpent'' by Marie de France (''Fables'') Other well-known stories include '' The Tortoise and The Geese'' and '' The Tiger, the Brahmin and the Jackal''. Similar animal fables are found in most cultures of the world, although some folklorists view India as the prime source. The ''Panchatantra'' has been a source of the world's fable literature.

The French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine acknowledged his indebtedness to the work in the introduction to his Second Fables:

:"This is a second book of fables that I present to the public... I have to acknowledge that the greatest part is inspired from Pilpay, an Indian Sage".

''The Panchatantra'' is the origin also of several stories in ''Arabian Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'', '' Sindbad'', and of many Western nursery rhymes and ballads.

Origins and function

In the Indian tradition, ''The Panchatantra'' is a . ''Nīti'' can be roughly translated as "the wise conduct of life" and a ''

In the Indian tradition, ''The Panchatantra'' is a . ''Nīti'' can be roughly translated as "the wise conduct of life" and a ''śāstra

''Shastra'' (, IAST: , ) is a Sanskrit word that means "precept, rules, manual, compendium, book or treatise" in a general sense.Monier Williams, Monier Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Article on 'zAstra'' The wo ...

'' is a technical or scientific treatise; thus it is considered a treatise on political science and human conduct. Its literary sources are "the expert tradition of political science and the folk and literary traditions of storytelling". It draws from the Dharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

and

or AND may refer to:

Logic, grammar, and computing

* Conjunction (grammar), connecting two words, phrases, or clauses

* Logical conjunction in mathematical logic, notated as "∧", "⋅", "&", or simple juxtaposition

* Bitwise AND, a boolea ...

Artha

''Artha'' (; sa, अर्थ; Tamil: ''poruḷ'' / ''பொருள்'') is one of the four aims of human life in Indian philosophy.James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Rosen Publishing, New York, , pp 55–56 ...

''śāstra''s, quoting them extensively. It is also explained that ''nīti'' "represents an admirable attempt to answer the insistent question how to win the utmost possible joy from life in the world of men" and that ''nīti'' is "the harmonious development of the powers of man, a life in which security, prosperity, resolute action, friendship, and good learning are so combined to produce joy".

''The Panchatantra'' shares many stories in common with the Buddhist Jataka tales, purportedly told by the historical Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

before his death around 400 BCE. As the scholar Patrick Olivelle writes, "It is clear that the Buddhists did not invent the stories. ..It is quite uncertain whether the author of he Panchatantraborrowed his stories from the ''Jātaka''s or the ''Mahābhārata'', or whether he was tapping into a common treasury of tales, both oral and literary, of ancient India." Many scholars believe the tales were based on earlier oral folk traditions, which were finally written down, although there is no conclusive evidence. In the early 20th century, W. Norman Brown found that many folk tales in India appeared to be borrowed from literary sources and not vice versa.

An early Western scholar who studied ''The Panchatantra'' was Dr. Johannes Hertel, who thought the book had a Machiavellian character. Similarly, Edgerton noted that "the so-called 'morals' of the stories have no bearing on morality; they are unmoral, and often immoral. They glorify shrewdness and practical wisdom, in the affairs of life, and especially of politics, of government." Other scholars dismiss this assessment as one-sided, and view the stories as teaching , or proper moral conduct. Also:

According to Olivelle, "Indeed, the current scholarly debate regarding the intent and purpose of the 'Pañcatantra' — whether it supports unscrupulous Machiavellian politics or demands ethical conduct from those holding high office — underscores the rich ambiguity of the text". Konrad Meisig states that the ''Panchatantra'' has been incorrectly represented by some as "an entertaining textbook for the education of princes in the Machiavellian rules of '' Arthasastra''", but instead it is a book for the "Little Man" to develop "Niti" (social ethics, prudent behavior, shrewdness) in their pursuit of ''Artha'', and a work on social satire. According to Joseph Jacobs, "... if one thinks of it, the very ''raison d'être'' of the Fable is to imply its moral without mentioning it."

The Panchatantra, states

An early Western scholar who studied ''The Panchatantra'' was Dr. Johannes Hertel, who thought the book had a Machiavellian character. Similarly, Edgerton noted that "the so-called 'morals' of the stories have no bearing on morality; they are unmoral, and often immoral. They glorify shrewdness and practical wisdom, in the affairs of life, and especially of politics, of government." Other scholars dismiss this assessment as one-sided, and view the stories as teaching , or proper moral conduct. Also:

According to Olivelle, "Indeed, the current scholarly debate regarding the intent and purpose of the 'Pañcatantra' — whether it supports unscrupulous Machiavellian politics or demands ethical conduct from those holding high office — underscores the rich ambiguity of the text". Konrad Meisig states that the ''Panchatantra'' has been incorrectly represented by some as "an entertaining textbook for the education of princes in the Machiavellian rules of '' Arthasastra''", but instead it is a book for the "Little Man" to develop "Niti" (social ethics, prudent behavior, shrewdness) in their pursuit of ''Artha'', and a work on social satire. According to Joseph Jacobs, "... if one thinks of it, the very ''raison d'être'' of the Fable is to imply its moral without mentioning it."

The Panchatantra, states Patrick Olivelle

Patrick Olivelle is an Indologist. A philologist and scholar of Sanskrit Literature whose work has focused on asceticism, renunciation and the dharma, Olivelle has been Professor of Sanskrit and Indian Religions in the Department of Asian Stu ...

, tells wonderfully a collection of delightful stories with pithy proverbs, ageless and practical wisdom; one of its appeal and success is that it is a complex book that "does not reduce the complexities of human life, government policy, political strategies, and ethical dilemmas into simple solutions; it can and does speak to different readers at different levels." In the Indian tradition, the work is a Shastra genre of literature, more specifically a ''Nitishastra'' text.

The text has been a source of studies on political thought in Hinduism, as well as the management of Artha

''Artha'' (; sa, अर्थ; Tamil: ''poruḷ'' / ''பொருள்'') is one of the four aims of human life in Indian philosophy.James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Rosen Publishing, New York, , pp 55–56 ...

with a debate on virtues and vices.

Metaphors and layered meanings

The Sanskrit version of the ''Panchatantra'' text gives names to the animal characters, but these names are creative with double meanings. The names connote the character observable in nature but also map a human personality that a reader can readily identify. For example, the deer characters are presented as a metaphor for the charming, innocent, peaceful and tranquil personality who is a target for those who seek a prey to exploit, while the crocodile is presented to symbolize dangerous intent hidden beneath a welcoming ambiance (waters of a lotus flower-laden pond). Dozens of different types of wildlife found in India are thus named, and they constitute an array of symbolic characters in the ''Panchatantra''. Thus, the names of the animals evoke layered meaning that resonates with the reader, and the same story can be read at different levels.Cross-cultural migrations

The work has gone through many different versions and translations from the sixth century to the present day. The original Indian version was first translated into a foreign language ( Pahlavi) by Borzūya in 570CE, then into Arabic in 750. This Arabic version was translated into several languages, including Syriac, Greek, Persian, Hebrew and Spanish, and thus became the source of versions in European languages, until the English translation by Charles Wilkins of the

The work has gone through many different versions and translations from the sixth century to the present day. The original Indian version was first translated into a foreign language ( Pahlavi) by Borzūya in 570CE, then into Arabic in 750. This Arabic version was translated into several languages, including Syriac, Greek, Persian, Hebrew and Spanish, and thus became the source of versions in European languages, until the English translation by Charles Wilkins of the Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

'' Hitopadesha'' in 1787.

Early cross-cultural migrations

The ''Panchatantra'' approximated its current literary form within the 4th–6th centuries CE, though originally written around 200 BCE. No Sanskrit texts before 1000 CE have survived. Buddhist monks on pilgrimage to India took the influential Sanskrit text (probably both in oral and literary formats) north to Tibet and China and east to South East Asia. These led to versions in all Southeast Asian countries, including Tibetan, Chinese, Mongolian, Javanese and Lao derivatives.How Borzuy brought the work from India

The ''Panchatantra'' also migrated into the Middle East, through

The ''Panchatantra'' also migrated into the Middle East, through Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, during the Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

reign of Anoushiravan.Dagmar Riedel (2010)KALILA WA DEMNA i. Redactions and circulation

Encyclopaedia Iranica Around 550 CE his notable physician Borzuy (Burzuwaih) translated the work from Sanskrit into the Pahlavi (

Middle Persian

Middle Persian or Pahlavi, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg () in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle P ...

language). He transliterated the main characters as ''Karirak ud Damanak''.

According to the story told in the '' Shāh Nāma'' (''The Book of the Kings'', Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

's late 10th-century national epic by Ferdowsi

, image = Statue of Ferdowsi in Tus, Iran 3 (cropped).jpg

, image_size =

, caption = Statue of Ferdowsi in Tus by Abolhassan Sadighi

, birth_date = 940

, birth_place = Tus, Samanid Empire

, death_date = 1019 or 1025 (87 years old)

, d ...

), Borzuy sought his king's permission to make a trip to Hindustan in search of a mountain herb he had read about that is "mingled into a compound and, when sprinkled over a corpse, it is immediately restored to life."The Shāh Nãma, The Epic of the Kings, translated by Reuben Levy, revised by Amin Banani, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1985, Chapter XXXI (iii) How Borzuy brought the Kalila of Demna from Hindustan, pages 330 – 334 He did not find the herb, but was told by a wise sage of "a different interpretation. The herb is the scientist; science is the mountain, everlastingly out of reach of the multitude. The corpse is the man without knowledge, for the uninstructed man is everywhere lifeless. Through knowledge man becomes revivified."The sage pointed to the book, and the visiting physician Borzuy translated the work with the help of some Pandits (

Brahmin

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests ( purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers ( ...

s). According to Hans Bakker, Borzuy visited the kingdom of Kannauj in north India during the 6th century in an era of intense exchange between Persian and Indian royal courts, and he secretly translated a copy of the text then sent it to the court of Anoushiravan in Persia, along with other cultural and technical knowledge.

Kalila wa Demna: Mid. Persian and Arabic versions

Borzuy's translation of the Sanskrit version into Pahlavi arrived in Persia by the 6th century, but this Middle Persian version is now lost. The book had become popular in Sassanid, and was translated into Syriac and Arabic whose copies survive. According to Riedel, "the three preserved New Persian translations originated between the 10th and 12th century", and are based on the 8th-century Arabic translation by Ibn al-Muqaffa of Borzuy's work on ''Panchatantra''. It is the 8th-century ''Kalila wa Demna'' text, states Riedel, that has been the most influential of the known Arabic versions, not only in the Middle East, but also through its translations into Greek, Hebrew and Old Spanish.

The Persian

Borzuy's translation of the Sanskrit version into Pahlavi arrived in Persia by the 6th century, but this Middle Persian version is now lost. The book had become popular in Sassanid, and was translated into Syriac and Arabic whose copies survive. According to Riedel, "the three preserved New Persian translations originated between the 10th and 12th century", and are based on the 8th-century Arabic translation by Ibn al-Muqaffa of Borzuy's work on ''Panchatantra''. It is the 8th-century ''Kalila wa Demna'' text, states Riedel, that has been the most influential of the known Arabic versions, not only in the Middle East, but also through its translations into Greek, Hebrew and Old Spanish.

The Persian Ibn al-Muqaffa'

Abū Muhammad ʿAbd Allāh Rūzbih ibn Dādūya ( ar, ابو محمد عبدالله روزبه ابن دادويه), born Rōzbih pūr-i Dādōē ( fa, روزبه پور دادویه), more commonly known as Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ ( ar, ابن الم� ...

translated the ''Panchatantra'' (in pal, Kalilag-o Demnag, script=Latn) from Middle Persian

Middle Persian or Pahlavi, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg () in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle P ...

to Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

as ''Kalīla wa Dimna''. This is considered the first masterpiece of "Arabic literary prose."

The introduction of the first book of ''Kalila wa Demna'' is different from ''Panchatantra'', in being more elaborate and instead of king and his three sons studying in the Indian version, the Persian version speaks of a merchant and his three sons who had squandered away their father's wealth. The Persian version also makes an abrupt switch from the story of the three sons to an injured ox, and thereafter parallels the ''Panchatantra''.

The two jackals' names transmogrified into Kalila and Dimna in the Persian version. Perhaps because the first section constituted most of the work, or because translators could find no simple equivalent in Zoroastrian Pahlavi for the concept expressed by the Sanskrit word 'Panchatantra', the jackals' names, ''Kalila and Dimna,'' became the generic name for the entire work in classical times.

After the first chapter, Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ inserted a new one, telling of Dimna's trial. The jackal is suspected of instigating the death of the bull "Shanzabeh", a key character in the first chapter. The trial lasts for two days without conclusion, until a tiger and leopard appear to bear witness against Dimna. He is found guilty and put to death.

Ibn al-Muqaffa' inserted other additions and interpretations into his 750CE "re-telling" (see Francois de Blois' Burzōy's voyage to India and the origin of the book ''Kalīlah wa Dimnah''). The political theorist Jennifer London suggests that he was expressing risky political views in a metaphorical way. (Al-Muqaffa' was murdered within a few years of completing his manuscript). London has analysed how Ibn al-Muqaffa' could have used his version to make "frank political expression" at the 'Abbasid court (see J. London's "How To Do Things With Fables: Ibn al-Muqaffa''s Frank Speech in Stories from Kalila wa Dimna," ''History of Political Thought'' XXIX: 2 (2008)).

The introduction of the first book of ''Kalila wa Demna'' is different from ''Panchatantra'', in being more elaborate and instead of king and his three sons studying in the Indian version, the Persian version speaks of a merchant and his three sons who had squandered away their father's wealth. The Persian version also makes an abrupt switch from the story of the three sons to an injured ox, and thereafter parallels the ''Panchatantra''.

The two jackals' names transmogrified into Kalila and Dimna in the Persian version. Perhaps because the first section constituted most of the work, or because translators could find no simple equivalent in Zoroastrian Pahlavi for the concept expressed by the Sanskrit word 'Panchatantra', the jackals' names, ''Kalila and Dimna,'' became the generic name for the entire work in classical times.

After the first chapter, Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ inserted a new one, telling of Dimna's trial. The jackal is suspected of instigating the death of the bull "Shanzabeh", a key character in the first chapter. The trial lasts for two days without conclusion, until a tiger and leopard appear to bear witness against Dimna. He is found guilty and put to death.

Ibn al-Muqaffa' inserted other additions and interpretations into his 750CE "re-telling" (see Francois de Blois' Burzōy's voyage to India and the origin of the book ''Kalīlah wa Dimnah''). The political theorist Jennifer London suggests that he was expressing risky political views in a metaphorical way. (Al-Muqaffa' was murdered within a few years of completing his manuscript). London has analysed how Ibn al-Muqaffa' could have used his version to make "frank political expression" at the 'Abbasid court (see J. London's "How To Do Things With Fables: Ibn al-Muqaffa''s Frank Speech in Stories from Kalila wa Dimna," ''History of Political Thought'' XXIX: 2 (2008)).

The Arabic classic by Ibn al-Muqaffa

Borzuy's 570 CE Pahlavi translation (''Kalile va Demne'', now lost) was translated into Syriac. Nearly two centuries later, it was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa around 750 CE under the Arabic title, ''Kalīla wa Dimna''. After the Arab invasion of Persia (Iran), Ibn al-Muqaffa's version (two languages removed from the pre-Islamic Sanskrit original) emerged as the pivotal surviving text that enriched world literature. Ibn al-Muqaffa's work is considered a model of the finest Arabic prose style, and "is considered the first masterpiece of Arabic literary prose."

Some scholars believe that Ibn al-Muqaffa's translation of the second section, illustrating the Sanskrit principle of ''Mitra Laabha'' (Gaining Friends), became the unifying basis for the

Borzuy's 570 CE Pahlavi translation (''Kalile va Demne'', now lost) was translated into Syriac. Nearly two centuries later, it was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa around 750 CE under the Arabic title, ''Kalīla wa Dimna''. After the Arab invasion of Persia (Iran), Ibn al-Muqaffa's version (two languages removed from the pre-Islamic Sanskrit original) emerged as the pivotal surviving text that enriched world literature. Ibn al-Muqaffa's work is considered a model of the finest Arabic prose style, and "is considered the first masterpiece of Arabic literary prose."

Some scholars believe that Ibn al-Muqaffa's translation of the second section, illustrating the Sanskrit principle of ''Mitra Laabha'' (Gaining Friends), became the unifying basis for the Brethren of Purity

The Brethren of Purity ( ar, إخوان الصفا, Ikhwān Al-Ṣafā; also The Brethren of Sincerity) were a secret society of Muslim philosophers in Basra, Iraq, in the 9th or 10th century CE.

The structure of the organization and the id ...

(''Ikwhan al-Safa'') — the anonymous 9th-century CE encyclopedists whose prodigious literary effort, '' Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Sincerity'', codified Indian, Persian and Greek knowledge. A suggestion made by Goldziher, and later written on by Philip K. Hitti in his '' History of the Arabs'', proposes that "The appellation is presumably taken from the story of the ringdove in ''Kalilah wa-Dimnah'' in which it is related that a group of animals by acting as faithful friends (''ikhwan al-safa'') to one another escaped the snares of the hunter." This story is mentioned as an exemplum when the Brethren speak of mutual aid in one ''risaala'' (treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions." Tre ...

), a crucial part of their system of ethics.

Spread to the rest of Europe

Almost all pre-modern European translations of the Panchatantra arise from this Arabic version. From Arabic it was re-translated into Syriac in the 10th or 11th century, into Greek (as ''Stephanites and Ichnelates'') in 1080 by the Jewish Byzantine doctorSimeon Seth

Symeon Seth, "Symeōn Magister of Antioch onof Sēth". His first name may also be spelled Simeon or Simeo. (c. 1035 – c. 1110)Antonie Pietrobelli (2016)Qui est Syméon Seth ?Le Projet Syméon Seth. was a Byzantine scientist, translator and offi ...

, into 'modern' Persian by Abu'l-Ma'ali Nasrallah Munshi in 1121, and in 1252 into Spanish (old Castilian, '' Calila e Dimna'').

Perhaps most importantly, it was translated into Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

by Rabbi Joel in the 12th century. This Hebrew version was translated into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

by John of Capua as ''Directorium Humanae Vitae'', or "Directory of Human Life", and printed in 1480, and became the source of most European versions.

A German translation, ''Das Buch der Beispiele'', of the Panchatantra was printed in 1483, making this one of the earliest books to be printed by Gutenberg's press after the Bible.Vijay BedekarHistory of the Migration of ''Panchatantra''

, Institute for Oriental Study, Thane The Latin version was translated into Italian by Antonfrancesco Doni in 1552. This translation became the basis for the first English translation, in 1570: Sir Thomas North translated it into Elizabethan English as ''The Fables of Bidpai: The Morall Philosophie of Doni'' (reprinted by Joseph Jacobs, 1888). La Fontaine published ''The Fables of Bidpai'' in 1679, based on "the Indian sage Pilpay".

Modern era

It was the Panchatantra that served as the basis for the studies ofTheodor Benfey :''This is about the German philologist. For Theodor Benfey (born 1925) who developed a spiral periodic table of the elements in 1964, see Otto Theodor Benfey.''

Theodor Benfey (; 28 January 1809, in Nörten near Göttingen26 June 1881, in Göttin ...

, the pioneer in the field of comparative literature. His efforts began to clear up some confusion surrounding the history of the Panchatantra, culminating in the work of Hertel (, , , ) and . Hertel discovered several recensions in India, in particular the oldest available Sanskrit recension, the ''Tantrakhyayika'' in Kashmir, and the so-called North Western Family Sanskrit text by the Jain monk Purnabhadra in 1199 CE that blends and rearranges at least three earlier versions. Edgerton undertook a minute study of all texts which seemed "to provide useful evidence on the lost Sanskrit text to which, it must be assumed, they all go back", and believed he had reconstructed the original Sanskrit Panchatantra; this version is known as the Southern Family text.

Among modern translations, Arthur W. Ryder's translation (), translating prose for prose and verse for rhyming verse, remains popular. In the 1990s two English versions of the ''Panchatantra'' were published, Chandra Rajan's translation (like Ryder's, based on Purnabhadra's recension) by Penguin (1993), and Patrick Olivelle's translation (based on Edgerton's reconstruction of the ur-text) by Oxford University Press (1997). Olivelle's translation was republished in 2006 by the Clay Sanskrit Library.

Recently Ibn al-Muqaffa's historical milieu itself, when composing his masterpiece in Baghdad during the bloody Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

overthrow of the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

dynasty, has become the subject (and rather confusingly, also the title) of a gritty Shakespearean drama by the multicultural Kuwaiti playwright Sulayman Al-Bassam. Ibn al-Muqqafa's biographical background serves as an illustrative metaphor for today's escalating bloodthirstiness in Iraq — once again a historical vortex for clashing civilisations on a multiplicity of levels, including the obvious tribal, religious and political parallels.

The novelist Doris Lessing

Doris May Lessing (; 22 October 1919 – 17 November 2013) was a British-Zimbabwean novelist. She was born to British parents in Iran, where she lived until 1925. Her family then moved to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where she remain ...

notes in her introduction to Ramsay Wood's 1980 "retelling" of the first two of the five Panchatantra books,''Kalila and Dimna, Selected fables of Bidpai'', retold by Ramsay Wood (with an Introduction by Doris Lessing), Illustrated by Margaret Kilrenny, A Paladin Book, Granada, London, 1982 that

See also

* Arthashastra * Calila e Dimna * Hitopadesha * Jataka tales * Katha (storytelling format) * Kathasaritsagara * Mirrors for princes *Wisdom literature

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. Although this genre uses techniques of traditional oral storytelling, it ...

* One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

Notes

Editions and translations

(Ordered chronologically.)Sanskrit texts

;Critical editions *II and III

* * * * * * (reprinting in Devanagari only the text from his 1924 work) ;Others *

Google Books

* (Text with Sanskrit commentary) * (Complete Sanskrit text with Hindi translation)

Translations in English

;The Panchatantra * (also republished in 1956, reprint 1964, and by Jaico Publishing House, Bombay, 1949)Columbia University archives; (Translation based on Hertel's text of Purnabhadra's Recension of 1199 CE.) * (reprint: 1995) (Translation based on Hertel manuscript.) * (Translation based on Edgerton manuscript.) * (Accessible popular compilation derived from a Sanskrit text with reference to the aforementioned translations by Chandra Rajan and Patrick Olivelle.) * ;Kalila and Dimna, Fables of Bidpai and other texts *

Google Books

https://books.google.com/books?id=aGIUAAAAQAAJ Google Books] (translated from Silvestre de Stacy's 1816 collation of different Arabic manuscripts) * Also online a

Persian Literature in Translation

* * , reprinted by Philo Press, Amsterdam 1970 *

Google Books

(edited and induced from ''The Morall Philosophie of Doni'' by Sir Thomas North, 1570) *''Tales Within Tales'' – adapted from the fables of Pilpai, Sir Arthur N Wollaston, John Murray, London 1909 * * * *

Further reading

* *N. M. Penzer (1924), ''The Ocean of Story, Being C.H. Tawney's Translation of Somadeva's Katha Sarit Sagara (or Ocean of Streams of Story)'': Volume V (of X)Appendix I: pp. 207–242

als

*Ferial Ghazoul (1983)

Poetic Logic in The Panchatantra and The Arabian Nights

Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Winter 1983), pp. 13–21 *''Burzoy's Voyage to India and the Origin of the Book of Kalilah wa Dimnah'

Google Books

Francois de Blois, Royal Asiatic Society, London, 1990 *''On Kalila wa Dimna and Persian National Fairy Tales'

Transoxiana.com

Dr. Pavel Basharin oscow Tansoxiana 12, 2007 *''The Past We Share — The Near Eastern Ancestry of Western Folk Literature'', E. L. Ranelagh, Quartet Books, Horizon Press, New York, 1979 *''In Arabian Nights — A Search of Morocco through its Stories and Storytellers'' by Tahir Shah, Doubleday, 2008. *Ibn al-Muqaffa, Abdallah. ''Kalilah et Dimnah''. Ed. P. Louis Cheiko. 3 ed. Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1947. *Ibn al-Muqaffa, Abd'. ''Calila e Dimna''. Edited by Juan Manuel Cacho Blecua and María Jesus Lacarra. Madrid: Editorial Castalia, 1984. *Keller, John Esten, and Robert White Linker. ''El libro de Calila e Digna''. Madrid Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1967. *Latham, J.D. "Ibn al-Muqaffa' and Early 'Abbasid Prose." Abbasid Belles-Lettres''. Eds. Julia Ashtiany, et al. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989. 48–77. *Parker, Margaret. ''The Didactic Structure and Content of El libro de Calila e Digna''. Miami, FL: Ediciones Universal, 1978. *Penzol, Pedro. Las traducciones del "Calila e Dimna". Madrid,: Impr. de Ramona Velasco, viuda de P. Perez,, 1931. *Shaw, Sandra. ''The Jatakas — Birth Stories of the Bodhisatta'', Penguin Classics, Penguin Books India, New Delhi, 2006 *Wacks, David A. "The Performativity of Ibn al-Muqaffa''s ''Kalîla wa-Dimna'' and ''Al-Maqamat al-Luzumiyya'' of al-Saraqusti," ''Journal of Arabic Literature'' 34.1–2 (2003): 178–89.

External links

* * * * * {{Authority control 3rd-century BC books Ancient Indian literature Fables History of literature Indian folklore Islamic mirrors for princes Medieval Arabic literature Oral tradition Persian literature Sanskrit texts Storytelling Treatises