Paleocene Mammals on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological

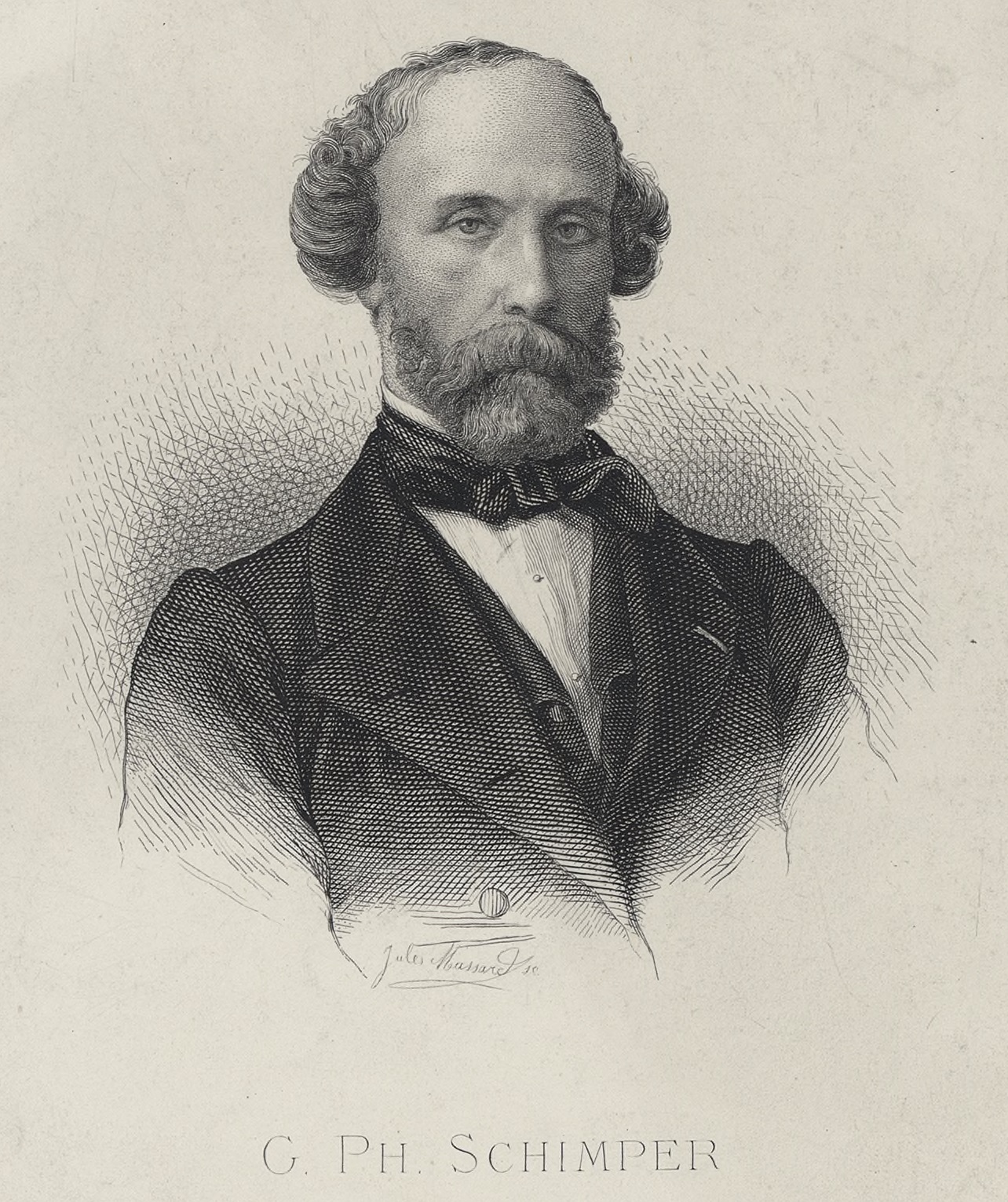

The word "Paleocene" was first used by French

The word "Paleocene" was first used by French

The Paleocene Epoch is the 10 million year time interval directly after the K–Pg extinction event, which ended the

The Paleocene Epoch is the 10 million year time interval directly after the K–Pg extinction event, which ended the

The Selandian and Thanetian are both defined in Itzurun beach by the Basque town of Zumaia, , as the area is a continuous early Santonian to

The Selandian and Thanetian are both defined in Itzurun beach by the Basque town of Zumaia, , as the area is a continuous early Santonian to

Several economically important coal deposits formed during the Paleocene, such as the sub-bituminous Fort Union Formation in the

Several economically important coal deposits formed during the Paleocene, such as the sub-bituminous Fort Union Formation in the

During the Paleocene, the continents continued to drift toward their present positions. In the Northern Hemisphere, the former components of

During the Paleocene, the continents continued to drift toward their present positions. In the Northern Hemisphere, the former components of  The components of the former southern supercontinent

The components of the former southern supercontinent

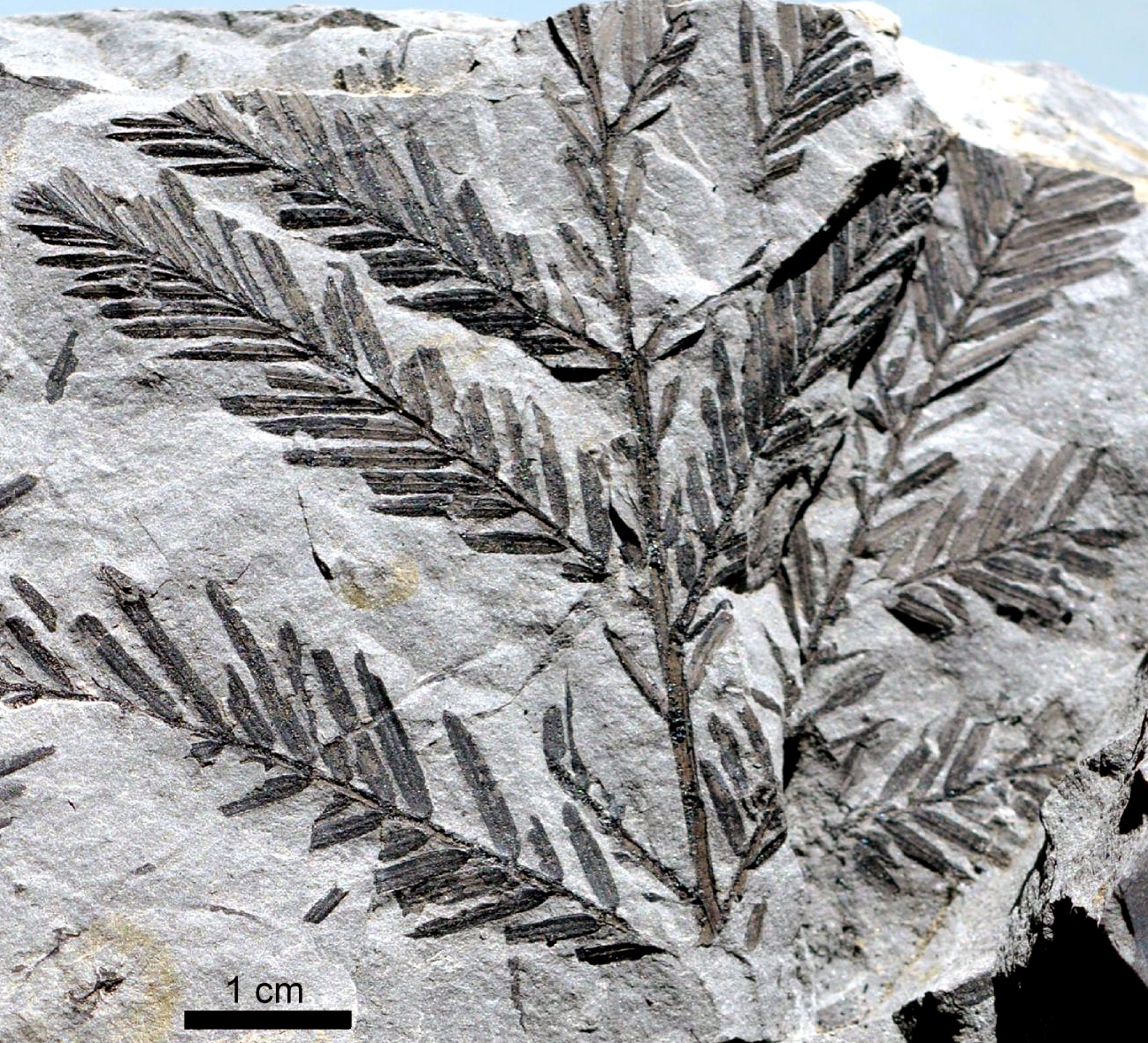

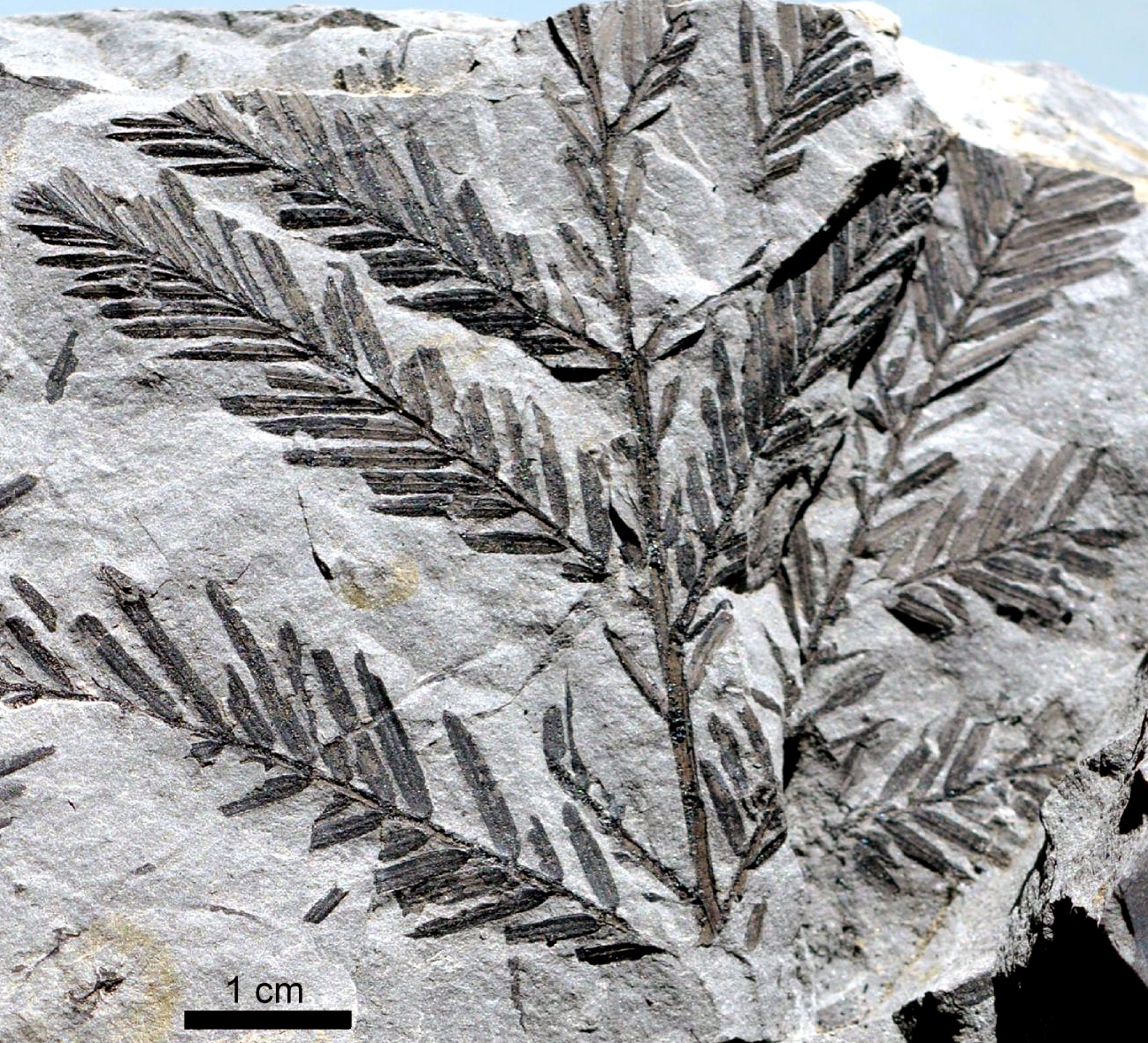

The warm, wet climate supported tropical and subtropical forests worldwide, mainly populated by

The warm, wet climate supported tropical and subtropical forests worldwide, mainly populated by  The extinction of large herbivorous dinosaurs may have allowed the forests to grow quite dense, and there is little evidence of wide open plains. Plants evolved several techniques to cope with high plant density, such as buttressing to better absorb nutrients and compete with other plants, increased height to reach sunlight, larger

The extinction of large herbivorous dinosaurs may have allowed the forests to grow quite dense, and there is little evidence of wide open plains. Plants evolved several techniques to cope with high plant density, such as buttressing to better absorb nutrients and compete with other plants, increased height to reach sunlight, larger

The

The

Flowering plants (

Flowering plants (

The warm Paleocene climate, much like that of the Cretaceous, allowed for diverse polar forests. Whereas precipitation is a major factor in plant diversity nearer the equator, polar plants had to adapt to varying light availability (

The warm Paleocene climate, much like that of the Cretaceous, allowed for diverse polar forests. Whereas precipitation is a major factor in plant diversity nearer the equator, polar plants had to adapt to varying light availability (

Mammals had first appeared in the

Mammals had first appeared in the  Nonetheless, following the K–Pg extinction event, mammals very quickly diversified and filled the empty niches. Modern mammals are subdivided into therians (modern members are

Nonetheless, following the K–Pg extinction event, mammals very quickly diversified and filled the empty niches. Modern mammals are subdivided into therians (modern members are

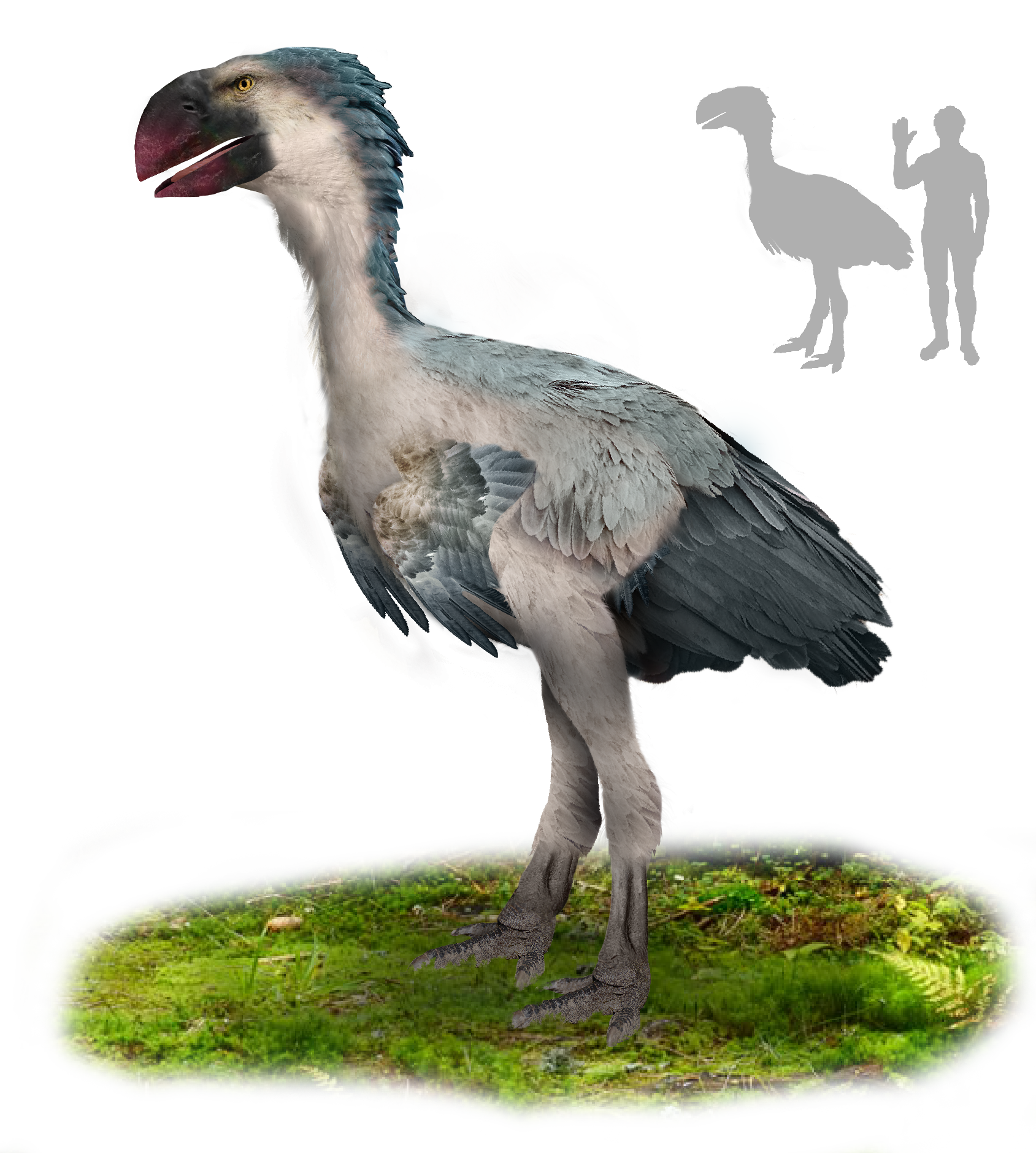

According to DNA studies, modern birds (Neornithes) rapidly diversified following the extinction of the other dinosaurs in the Paleocene, and nearly all modern bird lineages can trace their origins to this epoch with the exception of fowl and the paleognaths. This was one of the fastest diversifications of any group, probably fueled by the diversification of fruit-bearing trees and associated insects, and the modern bird groups had likely already diverged within 4 million years of the K–Pg extinction event. However, the fossil record of birds in the Paleocene is rather poor compared to other groups, limited globally to mainly waterbirds such as the early penguin ''Waimanu''. The earliest arboreal crown group bird known is ''Tsidiiyazhi'', a mousebird dating to around 62 mya. The fossil record also includes early owls such as the large ''Berruornis'' from France, and the smaller ''Ogygoptynx'' from the United States.

Almost all archaic birds (any bird outside Neornithes) went extinct during the K–Pg extinction event, although the archaic ''Qinornis'' is recorded in the Paleocene. Their extinction may have led to the proliferation of neornithine birds in the Paleocene, and the only known Cretaceous neornithine bird is the waterbird ''Vegavis'', and possibly also the waterbird ''Teviornis''.

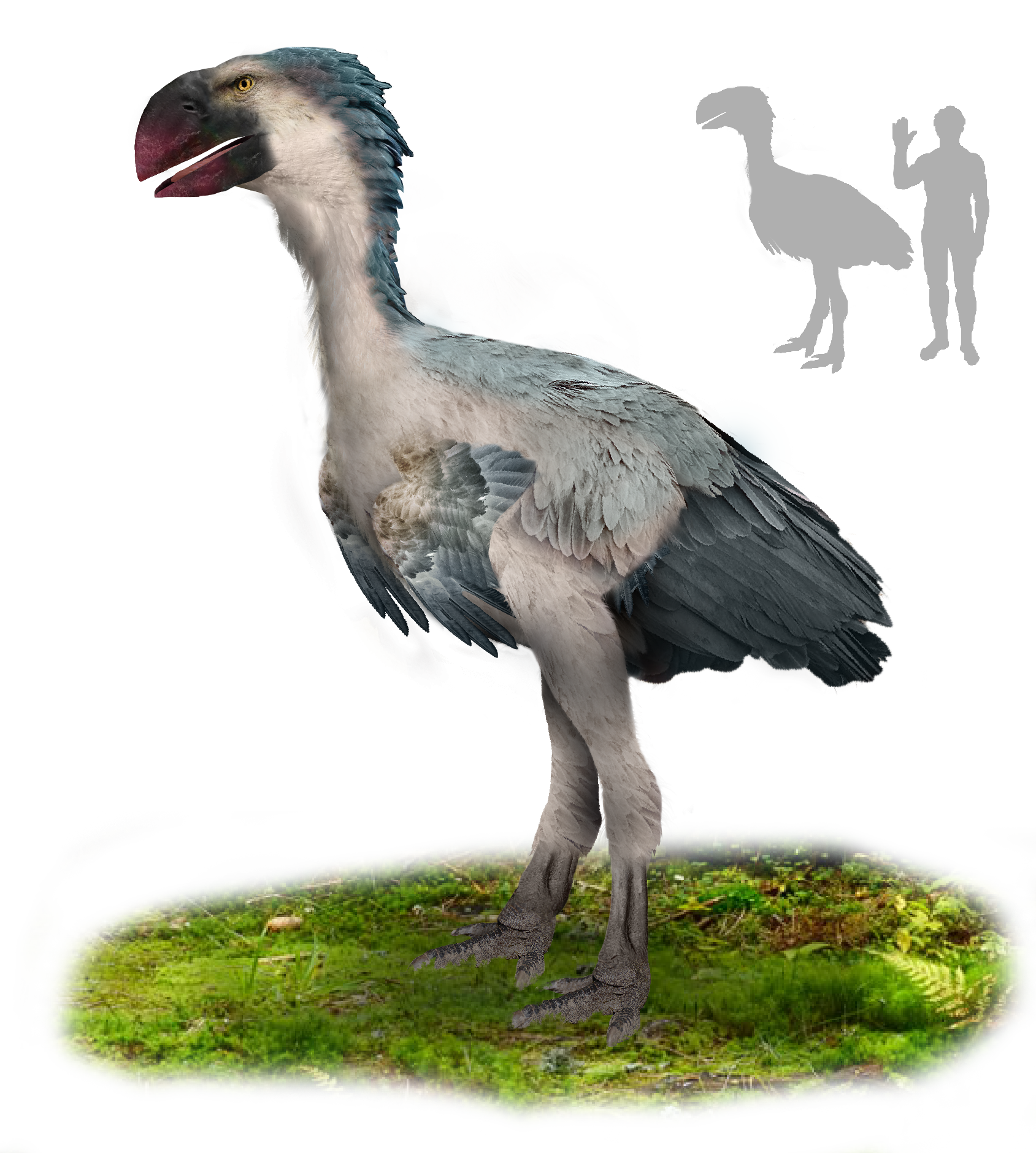

In the Mesozoic, birds and pterosaurs exhibited size-related niche partitioning—no known Late Cretaceous flying bird had a wingspan greater than nor exceeded a weight of , whereas contemporary pterosaurs ranged from , probably to avoid competition. Their extinction allowed flying birds to attain greater size, such as pelagornithids and pelecaniformes. The Paleocene pelagornithid ''Protodontopteryx'' was quite small compared to later members, with a wingspan of about , comparable to a gull. On the archipelago-continent of Europe, the flightless bird ''Gastornis'' was the largest herbivore at tall for the largest species, possibly due to lack of competition from newly emerging large mammalian herbivores which were prevalent on the other continents. The carnivorous Phorusrhacidae, terror birds in South America have a contentious appearance in the Paleocene with ''Paleopsilopterus'', though the first definitive appearance is in the Eocene.

According to DNA studies, modern birds (Neornithes) rapidly diversified following the extinction of the other dinosaurs in the Paleocene, and nearly all modern bird lineages can trace their origins to this epoch with the exception of fowl and the paleognaths. This was one of the fastest diversifications of any group, probably fueled by the diversification of fruit-bearing trees and associated insects, and the modern bird groups had likely already diverged within 4 million years of the K–Pg extinction event. However, the fossil record of birds in the Paleocene is rather poor compared to other groups, limited globally to mainly waterbirds such as the early penguin ''Waimanu''. The earliest arboreal crown group bird known is ''Tsidiiyazhi'', a mousebird dating to around 62 mya. The fossil record also includes early owls such as the large ''Berruornis'' from France, and the smaller ''Ogygoptynx'' from the United States.

Almost all archaic birds (any bird outside Neornithes) went extinct during the K–Pg extinction event, although the archaic ''Qinornis'' is recorded in the Paleocene. Their extinction may have led to the proliferation of neornithine birds in the Paleocene, and the only known Cretaceous neornithine bird is the waterbird ''Vegavis'', and possibly also the waterbird ''Teviornis''.

In the Mesozoic, birds and pterosaurs exhibited size-related niche partitioning—no known Late Cretaceous flying bird had a wingspan greater than nor exceeded a weight of , whereas contemporary pterosaurs ranged from , probably to avoid competition. Their extinction allowed flying birds to attain greater size, such as pelagornithids and pelecaniformes. The Paleocene pelagornithid ''Protodontopteryx'' was quite small compared to later members, with a wingspan of about , comparable to a gull. On the archipelago-continent of Europe, the flightless bird ''Gastornis'' was the largest herbivore at tall for the largest species, possibly due to lack of competition from newly emerging large mammalian herbivores which were prevalent on the other continents. The carnivorous Phorusrhacidae, terror birds in South America have a contentious appearance in the Paleocene with ''Paleopsilopterus'', though the first definitive appearance is in the Eocene.

It is generally believed all non-avian dinosaurs went extinct at the K–Pg extinction event 66 mya, though there are a couple of controversial claims of Paleocene dinosaurs which would indicate a gradual decline of dinosaurs. Contentious dates include remains from the Hell Creek Formation dated 40,000 years after the boundary, and a hadrosaur femur from the San Juan Basin dated to 64.5 mya, but such stray late forms may be zombie taxa that were washed out and moved to younger sediments.

In the wake of the K–Pg extinction event, 83% of lizard and snake (squamate) species went extinct, and the diversity did not fully recover until the end of the Paleocene. However, since the only major squamate lineages to disappear in the event were the mosasaurs and polyglyphanodontians (the latter making up 40% of Maastrichtian lizard diversity), and most major squamate groups had evolved by the Cretaceous, the event probably did not greatly affect squamate evolution, and newly evolving squamates did not seemingly branch out into new niches as mammals. That is, Cretaceous and Paleogene squamates filled the same niches. Nonetheless, there was a faunal turnover of squamates, and groups that were dominant by the Eocene were not as abundant in the Cretaceous, namely the anguids, Iguanidae, iguanas, night lizards, Pythonoidea, pythons, Caenophidia, colubrids, Booidea, boas, and worm lizards. Only small squamates are known from the early Paleocene—the largest snake ''Helagras'' was in length—but the late Paleocene snake ''Titanoboa'' grew to over long, the longest snake ever recorded. Kawasphenodon, ''Kawasphenodon peligrensis'' from the early Paleocene of South America represents the youngest record of Rhynchocephalia outside of New Zealand, where the only extant representative of the order, the tuatara, resides.

Freshwater crocodilians and choristoderans were among the aquatic reptiles to have survived the K–Pg extinction event, probably because freshwater environments were not as impacted as marine ones. One example of a Paleocene crocodile is ''Borealosuchus'', which averaged in length at the Wannagan Creek site. Among crocodyliformes, the aquatic and terrestrial Dyrosauridae, dyrosaurs and the fully terrestrial Sebecidae, sebecids would also survive the K-Pg extinction event, and a late surviving member of Pholidosauridae is also known from the Danian of Morocco. Three choristoderans are known from the Paleocene: The gharial-like Neochoristodera, neochoristoderans ''Champsosaurus''—the largest is the Paleocene ''C. gigas'' at '', Simoedosaurus''—the largest specimen measuring , and an indeterminate species of the lizard like non-neochoristoderan ''Lazarussuchus'' around 44 centimetres in length. The last known choristoderes, belonging to the genus ''Lazarussuchus,'' are known from the Miocene.

Turtles experienced a decline in the Campanian (Late Cretaceous) during a cooling event, and recovered during the PETM at the end of the Paleocene. Turtles were not greatly affected by the K–Pg extinction event, and around 80% of species survived. In Colombia, a 60 million year old turtle with a carapace, ''Carbonemys'', was discovered.

It is generally believed all non-avian dinosaurs went extinct at the K–Pg extinction event 66 mya, though there are a couple of controversial claims of Paleocene dinosaurs which would indicate a gradual decline of dinosaurs. Contentious dates include remains from the Hell Creek Formation dated 40,000 years after the boundary, and a hadrosaur femur from the San Juan Basin dated to 64.5 mya, but such stray late forms may be zombie taxa that were washed out and moved to younger sediments.

In the wake of the K–Pg extinction event, 83% of lizard and snake (squamate) species went extinct, and the diversity did not fully recover until the end of the Paleocene. However, since the only major squamate lineages to disappear in the event were the mosasaurs and polyglyphanodontians (the latter making up 40% of Maastrichtian lizard diversity), and most major squamate groups had evolved by the Cretaceous, the event probably did not greatly affect squamate evolution, and newly evolving squamates did not seemingly branch out into new niches as mammals. That is, Cretaceous and Paleogene squamates filled the same niches. Nonetheless, there was a faunal turnover of squamates, and groups that were dominant by the Eocene were not as abundant in the Cretaceous, namely the anguids, Iguanidae, iguanas, night lizards, Pythonoidea, pythons, Caenophidia, colubrids, Booidea, boas, and worm lizards. Only small squamates are known from the early Paleocene—the largest snake ''Helagras'' was in length—but the late Paleocene snake ''Titanoboa'' grew to over long, the longest snake ever recorded. Kawasphenodon, ''Kawasphenodon peligrensis'' from the early Paleocene of South America represents the youngest record of Rhynchocephalia outside of New Zealand, where the only extant representative of the order, the tuatara, resides.

Freshwater crocodilians and choristoderans were among the aquatic reptiles to have survived the K–Pg extinction event, probably because freshwater environments were not as impacted as marine ones. One example of a Paleocene crocodile is ''Borealosuchus'', which averaged in length at the Wannagan Creek site. Among crocodyliformes, the aquatic and terrestrial Dyrosauridae, dyrosaurs and the fully terrestrial Sebecidae, sebecids would also survive the K-Pg extinction event, and a late surviving member of Pholidosauridae is also known from the Danian of Morocco. Three choristoderans are known from the Paleocene: The gharial-like Neochoristodera, neochoristoderans ''Champsosaurus''—the largest is the Paleocene ''C. gigas'' at '', Simoedosaurus''—the largest specimen measuring , and an indeterminate species of the lizard like non-neochoristoderan ''Lazarussuchus'' around 44 centimetres in length. The last known choristoderes, belonging to the genus ''Lazarussuchus,'' are known from the Miocene.

Turtles experienced a decline in the Campanian (Late Cretaceous) during a cooling event, and recovered during the PETM at the end of the Paleocene. Turtles were not greatly affected by the K–Pg extinction event, and around 80% of species survived. In Colombia, a 60 million year old turtle with a carapace, ''Carbonemys'', was discovered.

The small pelagic fish population recovered rather quickly, and there was a low extinction rate for sharks and rays. Overall, only 12% of fish species went extinct. During the Cretaceous, fishes were not very abundant, probably due to heightened predation by or competition with ammonites and squid, although large predatory fish did exist, including ichthyodectids, pachycormids, and Pachyrhizodus, pachyrhizodontids. Almost immediately following the K–Pg extinction event,

The small pelagic fish population recovered rather quickly, and there was a low extinction rate for sharks and rays. Overall, only 12% of fish species went extinct. During the Cretaceous, fishes were not very abundant, probably due to heightened predation by or competition with ammonites and squid, although large predatory fish did exist, including ichthyodectids, pachycormids, and Pachyrhizodus, pachyrhizodontids. Almost immediately following the K–Pg extinction event,  Conversely, sharks and rays appear to have been unable to exploit the vacant niches, and recovered the same pre-extinction abundance. There was a faunal turnover of sharks from mackerel sharks to ground sharks, as ground sharks are more suited to hunting the rapidly diversifying ray-finned fish whereas mackerel sharks target larger prey. The first megatoothed shark, ''Otodus obliquus''—the ancestor of the giant megalodon—is recorded from the Paleocene.

Several Paleocene freshwater fish are recorded from North America, including Amiidae, bowfins, gars, arowanas, Gonorynchidae, Ictaluridae, common catfish, smelt (fish), smelts, and Esox, pike.

Conversely, sharks and rays appear to have been unable to exploit the vacant niches, and recovered the same pre-extinction abundance. There was a faunal turnover of sharks from mackerel sharks to ground sharks, as ground sharks are more suited to hunting the rapidly diversifying ray-finned fish whereas mackerel sharks target larger prey. The first megatoothed shark, ''Otodus obliquus''—the ancestor of the giant megalodon—is recorded from the Paleocene.

Several Paleocene freshwater fish are recorded from North America, including Amiidae, bowfins, gars, arowanas, Gonorynchidae, Ictaluridae, common catfish, smelt (fish), smelts, and Esox, pike.

Insect recovery varied from place to place. For example, it may have taken until the PETM for insect diversity to recover in the western interior of North America, whereas Patagonian insect diversity had recovered by 4 million years after the K–Pg extinction event. In some areas, such as the Bighorn Basin in Wyoming, there is a dramatic increase in plant predation during the PETM, although this is probably not indicative of a diversification event in insects due to rising temperatures because plant predation decreases following the PETM. More likely, insects followed their host plant or plants which were expanding into mid-latitude regions during the PETM, and then retreated afterward.

The middle-to-late Paleocene French Menat Formation shows an abundance of beetles (making up 77.5% of the insect diversity)—especially weevils (50% of diversity), jewel beetles, leaf beetles, and reticulated beetles—as well as other true bugs—such as pond skaters—and cockroaches. To a lesser degree, there are also orthopterans, hymenopterans, Lepidoptera, butterflies, and flies, though planthoppers were more common than flies. Representing less than 1% of fossil remains Odonata, dragonflies, caddisflies, mayflies, earwigs, mantises, net-winged insects, and possibly termites.

The Wyoming Hanna Formation is the only known Paleocene formation to produce sizable pieces of amber, as opposed to only small droplets. The amber was formed by a single or a closely related group of either taxodiaceaen or Pinaceae, pine tree(s) which produced conifer cone, cones similar to those of dammaras. Only one insect, a thrips, has been identified.

Insect recovery varied from place to place. For example, it may have taken until the PETM for insect diversity to recover in the western interior of North America, whereas Patagonian insect diversity had recovered by 4 million years after the K–Pg extinction event. In some areas, such as the Bighorn Basin in Wyoming, there is a dramatic increase in plant predation during the PETM, although this is probably not indicative of a diversification event in insects due to rising temperatures because plant predation decreases following the PETM. More likely, insects followed their host plant or plants which were expanding into mid-latitude regions during the PETM, and then retreated afterward.

The middle-to-late Paleocene French Menat Formation shows an abundance of beetles (making up 77.5% of the insect diversity)—especially weevils (50% of diversity), jewel beetles, leaf beetles, and reticulated beetles—as well as other true bugs—such as pond skaters—and cockroaches. To a lesser degree, there are also orthopterans, hymenopterans, Lepidoptera, butterflies, and flies, though planthoppers were more common than flies. Representing less than 1% of fossil remains Odonata, dragonflies, caddisflies, mayflies, earwigs, mantises, net-winged insects, and possibly termites.

The Wyoming Hanna Formation is the only known Paleocene formation to produce sizable pieces of amber, as opposed to only small droplets. The amber was formed by a single or a closely related group of either taxodiaceaen or Pinaceae, pine tree(s) which produced conifer cone, cones similar to those of dammaras. Only one insect, a thrips, has been identified.

There is a gap in the ant fossil record from 78 to 55 mya, except for the Aneuretinae, aneuretine ''Napakimyrma paskapooensis'' from the 62–56 million year old Canadian Paskapoo Formation. Given high abundance in the Eocene, two of the modern dominant ant subfamilies—Ponerinae and Myrmicinae—likely originated and greatly diversified in the Paleocene, acting as major hunters of arthropods, and probably competed with each other for food and nesting grounds in the dense angiosperm leaf litter. Myrmicines expanded their diets to seeds and formed trophobiotic symbiosis, symbiotic relationships with aphids, mealybugs, treehoppers, and other honeydew (secretion), honeydew secreting insects which were also successful in angiosperm forests, allowing them to invade other biomes, such as the canopy or temperate environments, and achieve a worldwide distribution by the middle Eocene.

About 80% of the butterfly and moth (lepidopteran) fossil record occurs in the early Paleogene, specifically the late Paleocene and the middle-to-late Eocene. Most Paleocene lepidopteran compression fossils come from the Danish

There is a gap in the ant fossil record from 78 to 55 mya, except for the Aneuretinae, aneuretine ''Napakimyrma paskapooensis'' from the 62–56 million year old Canadian Paskapoo Formation. Given high abundance in the Eocene, two of the modern dominant ant subfamilies—Ponerinae and Myrmicinae—likely originated and greatly diversified in the Paleocene, acting as major hunters of arthropods, and probably competed with each other for food and nesting grounds in the dense angiosperm leaf litter. Myrmicines expanded their diets to seeds and formed trophobiotic symbiosis, symbiotic relationships with aphids, mealybugs, treehoppers, and other honeydew (secretion), honeydew secreting insects which were also successful in angiosperm forests, allowing them to invade other biomes, such as the canopy or temperate environments, and achieve a worldwide distribution by the middle Eocene.

About 80% of the butterfly and moth (lepidopteran) fossil record occurs in the early Paleogene, specifically the late Paleocene and the middle-to-late Eocene. Most Paleocene lepidopteran compression fossils come from the Danish

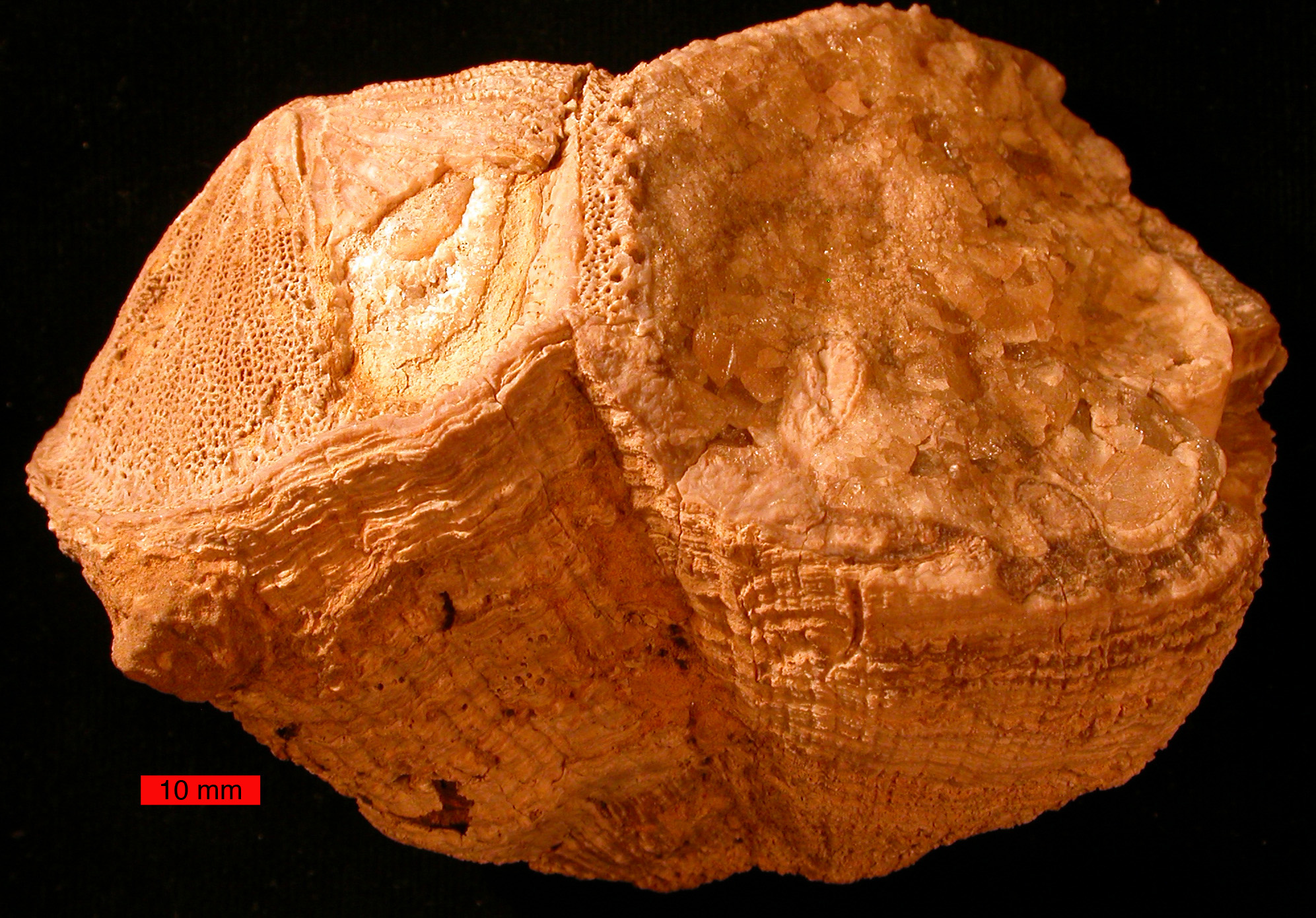

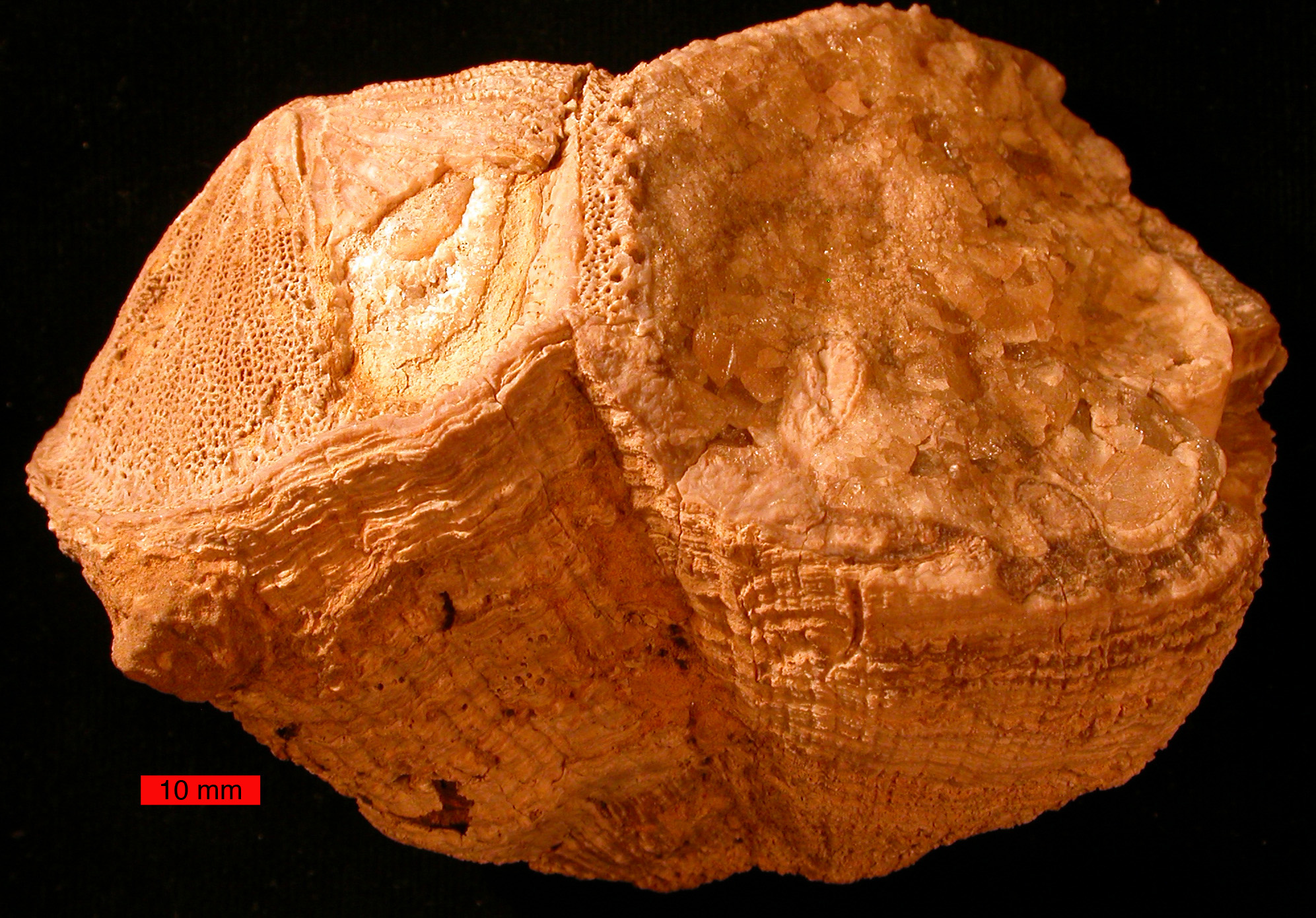

In the Cretaceous, the main reef-building creatures were the box-like bivalve rudists instead of coral—though a diverse Cretaceous coral assemblage did exist—and rudists had collapsed by the time of the K–Pg extinction event. Some corals are known to have survived in higher latitudes in the Late Cretaceous and into the Paleogene, and hard coral-dominated reefs may have recovered by 8 million years after the K–Pg extinction event, though the coral fossil record of this time is rather sparse. Though there was a lack of extensive coral reefs in the Paleocene, there were some colonies—mainly dominated by Zooxanthellae#Symbiosis with coral, zooxanthellate corals—in shallow coastal (neritic) areas. Starting in the latest Cretaceous and continuing until the early Eocene, calcareous corals rapidly diversified. Corals probably competed mainly with red algae, red and coralline algae, coralline algae for space on the seafloor. Calcified Dasycladales, dasycladalean green algae experienced the greatest diversity in their evolutionary history in the Paleocene. Though coral reef ecosystems do not become particularly abundant in the fossil record until the Miocene (possibly due to preservation bias), strong Paleocene coral reefs have been identified in what are now the Pyrenees (emerging as early as 63 mya), with some smaller Paleocene coral reefs identified across the Mediterranean region.

In the Cretaceous, the main reef-building creatures were the box-like bivalve rudists instead of coral—though a diverse Cretaceous coral assemblage did exist—and rudists had collapsed by the time of the K–Pg extinction event. Some corals are known to have survived in higher latitudes in the Late Cretaceous and into the Paleogene, and hard coral-dominated reefs may have recovered by 8 million years after the K–Pg extinction event, though the coral fossil record of this time is rather sparse. Though there was a lack of extensive coral reefs in the Paleocene, there were some colonies—mainly dominated by Zooxanthellae#Symbiosis with coral, zooxanthellate corals—in shallow coastal (neritic) areas. Starting in the latest Cretaceous and continuing until the early Eocene, calcareous corals rapidly diversified. Corals probably competed mainly with red algae, red and coralline algae, coralline algae for space on the seafloor. Calcified Dasycladales, dasycladalean green algae experienced the greatest diversity in their evolutionary history in the Paleocene. Though coral reef ecosystems do not become particularly abundant in the fossil record until the Miocene (possibly due to preservation bias), strong Paleocene coral reefs have been identified in what are now the Pyrenees (emerging as early as 63 mya), with some smaller Paleocene coral reefs identified across the Mediterranean region.

Paleocene Mammals

BBC Changing Worlds: Paleocene

Paleocene Microfossils: 35+ images of Foraminifera

{{featured article Paleocene, Geological epochs Paleogene geochronology

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago). ...

(mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

Period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (or rhetorical period), a concept ...

in the modern Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

Era

An era is a span of time defined for the purposes of chronology or historiography, as in the regnal eras in the history of a given monarchy, a calendar era used for a given calendar, or the geological eras defined for the history of Earth.

Comp ...

. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

''palaiós'' meaning "old" and the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', "da ...

Epoch (which succeeds the Paleocene), translating to "the old part of the Eocene".

The epoch is bracketed by two major events in Earth's history. The K–Pg extinction event, brought on by an asteroid impact and possibly volcanism, marked the beginning of the Paleocene and killed off 75% of living species, most famously the non-avian dinosaurs. The end of the epoch was marked by the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum

The Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM), alternatively (ETM1), and formerly known as the "Initial Eocene" or "", was a time period with a more than 5–8 °C global average temperature rise across the event. This climate event o ...

(PETM), which was a major climatic event wherein about 2,500–4,500 gigatons of carbon were released into the atmosphere and ocean systems, causing a spike in global temperatures and ocean acidification

Ocean acidification is the reduction in the pH value of the Earth’s ocean. Between 1751 and 2021, the average pH value of the ocean surface has decreased from approximately 8.25 to 8.14. The root cause of ocean acidification is carbon dioxi ...

.

In the Paleocene, the continents of the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's N ...

were still connected via some land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea l ...

s; and South America, Antarctica, and Australia had not completely separated yet. The Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

were being uplifted, the Americas had not yet joined, the Indian Plate

The Indian Plate (or India Plate) is a minor tectonic plate straddling the equator in the Eastern Hemisphere. Originally a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, the Indian Plate broke away from the other fragments of Gondwana , began mo ...

had begun its collision with Asia, and the North Atlantic Igneous Province

The North Atlantic Igneous Province (NAIP) is a large igneous province in the North Atlantic, centered on Iceland. In the Paleogene, the province formed the Thulean Plateau, a large basaltic lava plain, which extended over at least in area and i ...

was forming in the third-largest magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural s ...

tic event of the last 150 million years. In the oceans, the thermohaline circulation

Thermohaline circulation (THC) is a part of the large-scale ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes. The adjective ''thermohaline'' derives from '' thermo-'' referring to temp ...

probably was much different from what it is today, with downwellings occurring in the North Pacific rather than the North Atlantic, and water density mainly being controlled by salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal t ...

rather than temperature.

The K–Pg extinction event caused a floral and faunal turnover of species, with previously abundant species being replaced by previously uncommon ones. In the Paleocene, with a global average temperature of about , compared to in more recent times, the Earth had a greenhouse climate without permanent ice sheets at the poles, like the preceding Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

. As such, there were forests worldwide—including at the poles—but they had low species richness

Species richness is the number of different species represented in an ecological community, landscape or region. Species richness is simply a count of species, and it does not take into account the abundances of the species or their relative a ...

in regards to plant life, and were populated by mainly small creatures that were rapidly evolving to take advantage of the recently emptied Earth. Though some animals attained great size, most remained rather small. The forests grew quite dense in the general absence of large herbivores. Mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

s proliferated in the Paleocene, and the earliest placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

and marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a p ...

mammals are recorded from this time, but most Paleocene taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

have ambiguous affinities. In the seas, ray-finned fish

Actinopterygii (; ), members of which are known as ray-finned fishes, is a class of bony fish. They comprise over 50% of living vertebrate species.

The ray-finned fishes are so called because their fins are webs of skin supported by bony or h ...

rose to dominate open ocean and reef ecosystems.

Etymology

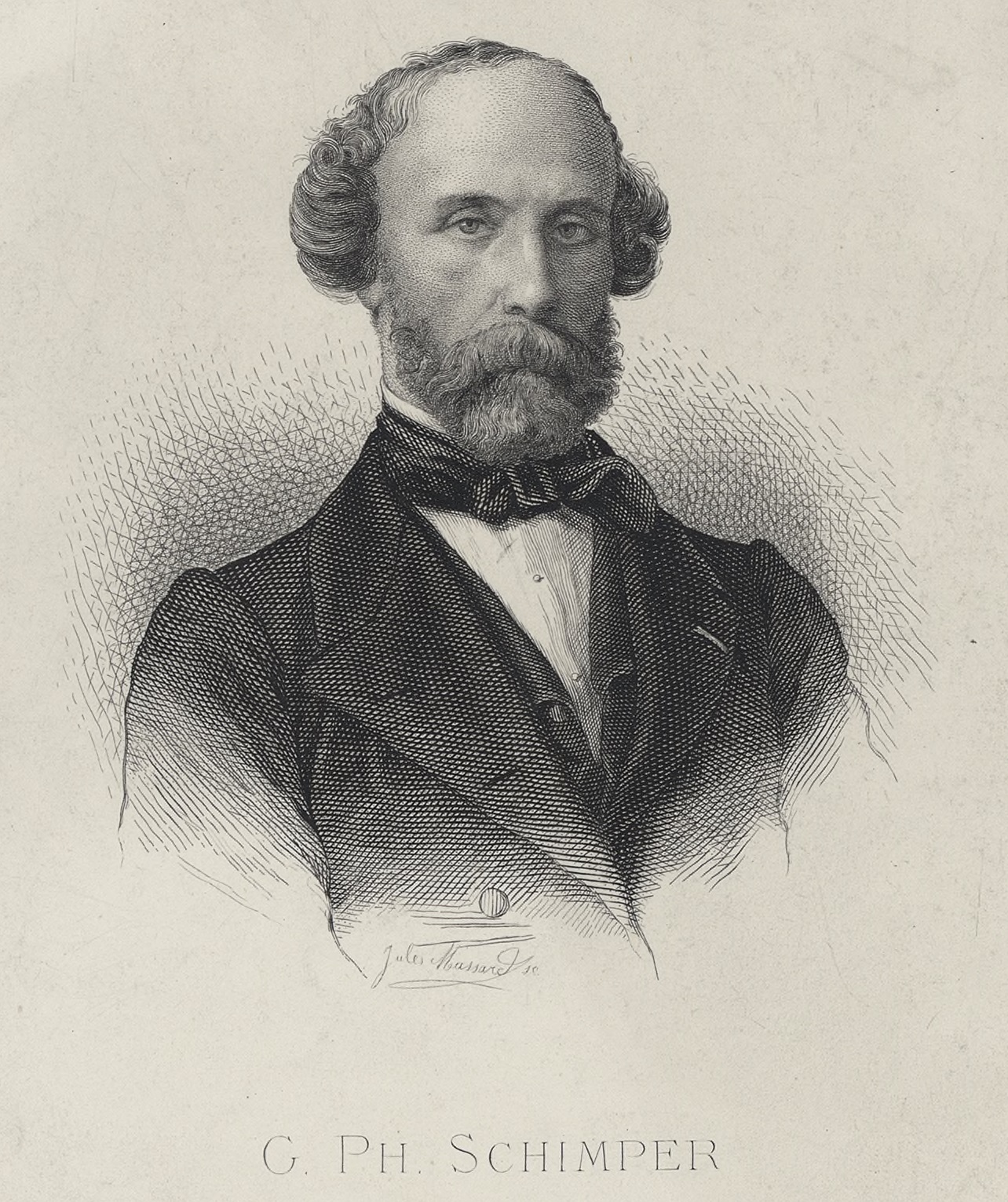

The word "Paleocene" was first used by French

The word "Paleocene" was first used by French paleobotanist

Paleobotany, which is also spelled as palaeobotany, is the branch of botany dealing with the recovery and identification of plant remains from geological contexts, and their use for the biological reconstruction of past environments (paleogeog ...

and geologist Wilhelm Philipp Schimper in 1874 while describing deposits near Paris (spelled in his treatise). By this time, Italian geologist Giovanni Arduino had divided the history of life on Earth into the Primary (Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

), Secondary (Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

), and Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non- avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

in 1759; French geologist Jules Desnoyers had proposed splitting off the Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million yea ...

from the Tertiary in 1829; and Scottish geologist Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

(ignoring the Quaternary) had divided the Tertiary Epoch into the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', "da ...

, Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recent ...

, Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

) Periods in 1833. British geologist John Phillips had proposed the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

in 1840 in place of the Tertiary, and Austrian paleontologist Moritz Hörnes had introduced the Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

for the Eocene and Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

for the Miocene and Pliocene in 1853. After decades of inconsistent usage, the newly formed International Commission on Stratigraphy

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), sometimes referred to unofficially as the "International Stratigraphic Commission", is a daughter or major subcommittee grade scientific daughter organization that concerns itself with stratig ...

(ICS), in 1969, standardized stratigraphy based on the prevailing opinions in Europe: the Cenozoic Era subdivided into the Tertiary and Quaternary sub-eras, and the Tertiary subdivided into the Paleogene and Neogene Periods. In 1978, the Paleogene was officially defined as the Paleocene, Eocene, and Oligocene Epochs; and the Neogene as the Miocene and Pliocene Epochs. In 1989, Tertiary and Quaternary were removed from the time scale due to the arbitrary nature of their boundary, but Quaternary was reinstated in 2009, which may lead to the reinstatement of the Tertiary in the future.

The term "Paleocene" is a portmanteau

A portmanteau word, or portmanteau (, ) is a blend of wordsAncient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

eo—''eos'' meaning "dawn", and—cene ''kainos'' meaning "new" or "recent", as the epoch saw the dawn of recent, or modern, life. Paleocene did not come into broad usage until around 1920. In North America and mainland Europe, the standard spelling is "Paleocene", whereas it is "Palaeocene" in the UK. Geologist T. C. R. Pulvertaft has argued that the latter spelling is incorrect because this would imply either a translation of "old recent" or a derivation from "pala" and "Eocene", which would be incorrect because the prefix palæo- uses the ligature æ instead of "a" and "e" individually, so only both characters or neither should be dropped, not just one.

Geology

Boundaries

Cretaceous Period

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

and the Mesozoic Era

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

, and initiated the Cenozoic Era and the Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

Period. It is divided into three ages: the Danian

The Danian is the oldest age or lowest stage of the Paleocene Epoch or Series, of the Paleogene Period or System, and of the Cenozoic Era or Erathem. The beginning of the Danian (and the end of the preceding Maastrichtian) is at the Cretaceou ...

spanning 66 to 61.6 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago). ...

(mya), the Selandian

The Selandian is a stage in the Paleocene. It spans the time between . It is preceded by the Danian and followed by the Thanetian. Sometimes the Paleocene is subdivided in subepochs, in which the Selandian forms the "middle Paleocene".

Stratig ...

spanning 61.6 to 59.2 mya, and the Thanetian

The Thanetian is, in the ICS Geologic timescale, the latest age or uppermost stratigraphic stage of the Paleocene Epoch or Series. It spans the time between . The Thanetian is preceded by the Selandian Age and followed by the Ypresian Age ...

spanning 59.2 to 56 mya. It is succeeded by the Eocene.

The K–Pg boundary is clearly defined in the fossil record in numerous places around the world by a high-iridium

Iridium is a chemical element with the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. A very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, it is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density of ...

band, as well as discontinuities with fossil flora and fauna. It is generally thought that a wide asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere ...

impact, forming the Chicxulub Crater

The Chicxulub crater () is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore near the community of Chicxulub, after which it is named. It was formed slightly over 66 million years ago when a large ...

in the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the nor ...

in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United St ...

, and Deccan Trap volcanism caused a cataclysmic event at the boundary resulting in the extinction of 75% of all species.

The Paleocene ended with the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum

The Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM), alternatively (ETM1), and formerly known as the "Initial Eocene" or "", was a time period with a more than 5–8 °C global average temperature rise across the event. This climate event o ...

, a short period of intense warming and ocean acidification

Ocean acidification is the reduction in the pH value of the Earth’s ocean. Between 1751 and 2021, the average pH value of the ocean surface has decreased from approximately 8.25 to 8.14. The root cause of ocean acidification is carbon dioxi ...

brought about by the release of carbon en masse into the atmosphere and ocean systems, which led to a mass extinction of 30–50% of benthic foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly a ...

–planktonic species which are used as bioindicator

A bioindicator is any species (an indicator species) or group of species whose function, population, or status can reveal the qualitative status of the environment. The most common indicator species are animals. For example, copepods and other sma ...

s of the health of a marine ecosystem—one of the largest in the Cenozoic. This event happened around 55.8 mya, and was one of the most significant periods of global change during the Cenozoic.

Stratigraphy

Geologists divide the rocks of the Paleocene into astratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

set of smaller rock units called stages, each formed during corresponding time intervals called ages. Stages can be defined globally or regionally. For ''global'' stratigraphic correlation, the ICS ratify global stages based on a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point

A Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) is an internationally agreed upon reference point on a stratigraphic section which defines the lower boundary of a stage on the geologic time scale. The effort to define GSSPs is conducted b ...

(GSSP) from a single formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

(a stratotype A stratotype or type section in geology is the physical location or outcrop of a particular reference exposure of a stratigraphic sequence or stratigraphic boundary. If the stratigraphic unit is layered, it is called a stratotype, whereas the sta ...

) identifying the lower boundary of the stage. In 1989, the ICS decided to split the Paleocene into three stages: the Danian, Selandian, and Thanetian.

The Danian was first defined in 1847 by German-Swiss geologist Pierre Jean Édouard Desor based on the Danish chalks at Stevns Klint and Faxse, and was part of the Cretaceous, succeeded by the Tertiary Montian Stage. In 1982, after it was shown that the Danian and the Montian are the same, the ICS decided to define the Danian as starting with the K–Pg boundary, thus ending the practice of including the Danian in the Cretaceous. In 1991, the GSSP was defined as a well-preserved section in the El Haria Formation near El Kef

El Kef ( ar, الكاف '), also known as ''Le Kef'', is a city in northwestern Tunisia. It serves as the capital of the Kef Governorate.

El Kef is situated to the west of Tunis and some east of the border between Algeria and Tunisia. It has ...

, Tunisia, , and the proposal was officially published in 2006.

early Eocene

In the geologic timescale the Ypresian is the oldest age or lowest stratigraphic stage of the Eocene. It spans the time between , is preceded by the Thanetian Age (part of the Paleocene) and is followed by the Eocene Lutetian Age. The Ypresia ...

sea cliff outcrop

An outcrop or rocky outcrop is a visible exposure of bedrock or ancient superficial deposits on the surface of the Earth.

Features

Outcrops do not cover the majority of the Earth's land surface because in most places the bedrock or superficial ...

. The Paleocene section is an essentially complete, exposed record thick, mainly composed of alternating hemipelagic sediments deposited at a depth of about . The Danian deposits are sequestered into the Aitzgorri Limestone Formation, and the Selandian and early Thanetian into the Itzurun Formation. The Itzurun Formation is divided into groups A and B corresponding to the two stages respectively. The two stages were ratified in 2008, and this area was chosen because of its completion, low risk of erosion, proximity to the original areas the stages were defined, accessibility, and the protected status of the area due to its geological significance.

The Selandian was first proposed by Danish geologist Alfred Rosenkrantz in 1924 based on a section of fossil-rich glauconitic marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part ...

s overlain by gray clay which unconformably overlies Danian chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Cha ...

and limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

. The area is now subdivided into the Æbelø Formation, Holmehus Formation, and the Østerrende Clay. The beginning of this stage was defined by the end of carbonate rock

Carbonate rocks are a class of sedimentary rocks composed primarily of carbonate minerals. The two major types are limestone, which is composed of calcite or aragonite (different crystal forms of CaCO3), and dolomite rock (also known as doloston ...

deposition from an open ocean

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

environment in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

region (which had been going on for the previous 40 million years). The Selandian deposits in this area are directly overlain by the Eocene Fur Formation

The Fur Formation is a marine geological formation of Ypresian ( Lower Eocene Epoch, c. 56.0-54.5 Ma) age which crops out in the Limfjord region of Denmark from Silstrup via Mors and Fur to Ertebølle, and can be seen in many cliffs and quarries ...

—the Thanetian was not represented here—and this discontinuity in the deposition record is why the GSSP was moved to Zumaia. Today, the beginning of the Selandian is marked by the appearances of the nannofossils '' Fasciculithus tympaniformis'', '' Neochiastozygus perfectus'', and '' Chiasmolithus edentulus'', though some foraminifera are used by various authors.

The Thanetian was first proposed by Swiss geologist Eugène Renevier, in 1873; he included the south England Thanet Thanet may refer to:

*Isle of Thanet, a former island, now a peninsula, at the most easterly point of Kent, England

*Thanet District, a local government district containing the island

*Thanet College, former name of East Kent College

* Thanet Cana ...

, Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained thro ...

, and Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spellin ...

formations. In 1880, French geologist Gustave Frédéric Dollfus narrowed the definition to just the Thanet Formation. The Thanetian begins a little after the mid-Paleocene biotic event—a short-lived climatic event caused by an increase in methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on ...

—recorded at Itzurun as a dark interval from a reduction of calcium carbonate. At Itzurun, it begins about above the base of the Selandian, and is marked by the first appearance of the algae '' Discoaster'' and a diversification of '' Heliolithus'', though the best correlation is in terms of paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetism (or palaeomagnetismsee ), is the study of magnetic fields recorded in rocks, sediment, or archeological materials. Geophysicists who specialize in paleomagnetism are called ''paleomagnetists.''

Certain magnetic minerals in rock ...

. A chron

Chron may refer to:

Science

* Chronozone or chron, a term used for a time interval in chronostratigraphy

* Polarity chron or chron, in magnetostratigraphy, the time interval between polarity reversals of the Earth's magnetic field

Other

...

is the occurrence of a geomagnetic reversal

A geomagnetic reversal is a change in a planet's magnetic field such that the positions of magnetic north and magnetic south are interchanged (not to be confused with geographic north and geographic south). The Earth's field has alternated b ...

—when the North and South poles switch polarities. Chron 1 (C1n) is defined as modern day to about 780,000 years ago, and the n denotes "normal" as in the polarity of today, and an r "reverse" for the opposite polarity. The beginning of the Thanetian is best correlated with the C26r/C26n reversal.

Mineral and hydrocarbon deposits

Several economically important coal deposits formed during the Paleocene, such as the sub-bituminous Fort Union Formation in the

Several economically important coal deposits formed during the Paleocene, such as the sub-bituminous Fort Union Formation in the Powder River Basin

The Powder River Basin is a geologic structural basin in southeast Montana and northeast Wyoming, about east to west and north to south, known for its extensive coal reserves. The former hunting grounds of the Oglala Lakota, the area is very s ...

of Wyoming and Montana, which produces 43% of American coal; the Wilcox Group in Texas, the richest deposits of the Gulf Coastal Plain

The Gulf Coastal Plain extends around the Gulf of Mexico in the Southern United States and eastern Mexico.

This coastal plain reaches from the Florida Panhandle, southwest Georgia, the southern two-thirds of Alabama, over most of Mississippi, ...

; and the Cerrejón mine in Colombia, the largest open-pit mine in the world. Paleocene coal has been mined extensively in Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group rang ...

, Norway, since near the beginning of the 20th century, and late Paleocene and early Eocene coal is widely distributed across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of Denmark).

Situated in the northern extremity of No ...

and northern Siberia. In the North Sea, Paleocene-derived natural gas reserves, when they were discovered, totaled approximately 2.23 trillion m3 (7.89 trillion ft3), and oil in place

Oil in place (OIP) (not to be confused with original oil-in-place (OOIP)) is a specialist term in petroleum geology that refers to the total oil content of an oil reservoir. As this quantity cannot be measured directly, it has to be estimated fro ...

13.54 billion barrels. Important phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from pho ...

deposits—predominantly of francolite—near Métlaoui, Tunisia were formed from the late Paleocene to the early Eocene.

Impact craters

Impact crater

An impact crater is a circular depression in the surface of a solid astronomical object formed by the hypervelocity impact of a smaller object. In contrast to volcanic craters, which result from explosion or internal collapse, impact crater ...

s formed in the Paleocene include: the Connolly Basin crater in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

less than 60 mya, the Texan Marquez crater 58 mya, and possibly the Jordan Jabel Waqf as Suwwan crater which dates to between 56 and 37 mya. Vanadium

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( pa ...

-rich osbornite from the Isle of Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye (; gd, An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or ; sco, Isle o Skye), is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated b ...

, Scotland, dating to 60 mya may be impact ejecta. Craters were also formed near the K–Pg boundary, the largest the Mexican Chicxulub crater

The Chicxulub crater () is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore near the community of Chicxulub, after which it is named. It was formed slightly over 66 million years ago when a large ...

whose impact was a major precipitator of the K–Pg extinction, and also the Ukrainian Boltysh crater

The Boltysh crater or Bovtyshka crater is a buried impact crater in the Kirovohrad Oblast of Ukraine, near the village of Bovtyshka. The crater is in diameter and its age of 65.39 ± 0.14/0.16 million years, based on argon-argon dating techniqu ...

, dated to 65.4 mya the Canadian Eagle Butte crater (though it may be younger), the Vista Alegre crater (though this may date to about 115 mya). Silicate glass spherules along the Atlantic coast of the U.S. indicate a meteor impact in the region at the PETM. The buried Hiawatha Glacier crater in Greenland has been dated to the late Paleocene, around 58 mya.

Paleogeography

Paleotectonics

During the Paleocene, the continents continued to drift toward their present positions. In the Northern Hemisphere, the former components of

During the Paleocene, the continents continued to drift toward their present positions. In the Northern Hemisphere, the former components of Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

(North America and Eurasia) were, at times, connected via land bridges: Beringia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip o ...

(at 65.5 and 58 mya) between North America and East Asia, the De Geer route (from 71 to 63 mya) between Greenland and Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swed ...

, the Thulean route (at 57 and 55.8 mya) between North America and Western Europe via Greenland, and the Turgai route connecting Europe with Asia (which were otherwise separated by the Turgai Strait at this time).

The Laramide orogeny

The Laramide orogeny was a time period of mountain building in western North America, which started in the Late Cretaceous, 70 to 80 million years ago, and ended 35 to 55 million years ago. The exact duration and ages of beginning and end of the ...

, which began in the Late Cretaceous, continued to uplift the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

; it ended at the end of the Paleocene. Because of this and a drop in sea levels resulting from tectonic activity, the Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, and the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea that split the continent of North America into two landmasses. The ancient sea ...

, which had divided the continent of North America for much of the Cretaceous, had receded.

Between about 60.5 and 54.5 mya, there was heightened volcanic activity in the North Atlantic region—the third largest magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural s ...

tic event in the last 150 million years—creating the North Atlantic Igneous Province

The North Atlantic Igneous Province (NAIP) is a large igneous province in the North Atlantic, centered on Iceland. In the Paleogene, the province formed the Thulean Plateau, a large basaltic lava plain, which extended over at least in area and i ...

. The proto- Iceland hotspot is sometimes cited as being responsible for the initial volcanism, though rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben w ...

ing and resulting volcanism have also contributed. This volcanism may have contributed to the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean and seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

, the divergence of the Greenland Plate from the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

, and, climatically, the PETM by dissociating methane clathrate

Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) or (8CH4·46H2O), also called methane hydrate, hydromethane, methane ice, fire ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate, is a solid clathrate compound (more specifically, a clathrate hydrate) in which a large amou ...

crystals on the seafloor resulting in the mass release of carbon.

North and South America remained separated by the Central American Seaway

The Central American Seaway (also known as the Panamanic Seaway, Inter-American Seaway and Proto-Caribbean Seaway) was a body of water that once separated North America from South America. It formed during the Jurassic (200–154 Ma) during the b ...

, though an island arc (the South Central American Arc) had already formed about 73 mya. The Caribbean Large Igneous Province (now the Caribbean Plate

The Caribbean Plate is a mostly oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America and the Caribbean Sea off the north coast of South America.

Roughly 3.2 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles) in area, the Caribbean Plate borde ...

), which had formed from the Galápagos hotspot

The Galápagos hotspot is a volcanic hotspot in the East Pacific Ocean responsible for the creation of the Galápagos Islands as well as three major aseismic ridge systems, Carnegie, Cocos and Malpelo which are on two tectonic plates. The hots ...

in the Pacific in the latest Cretaceous, was moving eastward as the North American and South American plates were getting pushed in the opposite direction due to the opening of the Atlantic ( strike-slip tectonics). This motion would eventually uplift the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the count ...

by 2.6 mya. The Caribbean Plate continued moving until about 50 mya when it reached its current position.

The components of the former southern supercontinent

The components of the former southern supercontinent Gondwanaland

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final sta ...

in the Southern Hemisphere continued to drift apart, but Antarctica was still connected to South America and Australia. Africa was heading north towards Europe, and the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, Ind ...

towards Asia, which would eventually close the Tethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( el, Τηθύς ''Tēthús''), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean that covered most of the Earth during much of the Mesozoic Era and early Cenozoic Era, located between the ancient continents ...

. The Indian and Eurasian

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

Plates began colliding sometime in the Paleocene or Eocene with uplift (and a land connection) beginning in the Miocene about 24–17 mya. There is evidence that some plants and animals could migrate between India and Asia during the Paleocene, possibly via intermediary island arcs.

Paleoceanography

In the modernthermohaline circulation

Thermohaline circulation (THC) is a part of the large-scale ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes. The adjective ''thermohaline'' derives from '' thermo-'' referring to temp ...

, warm tropical water becomes colder and saltier at the poles and sinks (downwelling

Downwelling is the process of accumulation and sinking of higher density material beneath lower density material, such as cold or saline water beneath warmer or fresher water or cold air beneath warm air. It is the ''sinking'' limb of a convecti ...

or deep water formation) that occurs at the North Atlantic near the North Pole and the Southern Ocean near the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctic ...

. In the Paleocene, the waterways between the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic were somewhat restricted, so North Atlantic Deep Water

North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is a deep water mass formed in the North Atlantic Ocean. Thermohaline circulation (properly described as meridional overturning circulation) of the world's oceans involves the flow of warm surface waters from th ...

(NADW) and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is part of a global thermohaline circulation in the oceans and is the zonally integrated component of surface and deep currents in the Atlantic Ocean. It is characterized by a northward f ...

(AMOC)—which circulates cold water from the Arctic towards the equator—had not yet formed, and so deep water formation probably did not occur in the North Atlantic. The Arctic and Atlantic would not be connected by sufficiently deep waters until the early to middle Eocene.

There is evidence of deep water formation in the North Pacific to at least a depth of about . The elevated global deep water temperatures in the Paleocene may have been too warm for thermohaline circulation to be predominately heat driven. It is possible that the greenhouse climate shifted precipitation patterns, such that the Southern Hemisphere was wetter than the Northern, or the Southern experienced less evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when h ...

than the Northern. In either case, this would have made the Northern more saline than the Southern, creating a density difference and a downwelling in the North Pacific traveling southward. Deep water formation may have also occurred in the South Atlantic.

It is largely unknown how global currents could have affected global temperature. The formation of the Northern Component Waters by Greenland in the Eocene—the predecessor of the AMOC—may have caused an intense warming in the North Hemisphere and cooling in the Southern, as well as an increase in deep water temperatures. In the PETM, it is possible deep water formation occurred in saltier tropical waters and moved polewards, which would increase global surface temperatures by warming the poles. Also, Antarctica was still connected to South America and Australia, and, because of this, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is an ocean current that flows clockwise (as seen from the South Pole) from west to east around Antarctica. An alternative name for the ACC is the West Wind Drift. The ACC is the dominant circulation feat ...

—which traps cold water around the continent and prevents warm equatorial water from entering—had not yet formed. Its formation may have been related in the freezing of the continent. Warm coastal upwelling

Upwelling is an oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted surface water. The n ...

s at the poles would have inhibited permanent ice cover. Conversely, it is possible deep water circulation was not a major contributor to the greenhouse climate, and deep water temperatures more likely change as a response to global temperature change rather than affecting it.

In the Arctic, coastal upwelling may have been largely temperature and wind-driven. In summer, the land surface temperature was probably higher than oceanic temperature, and the opposite was true in the winter, which is consistent with monsoon seasons in Asia. Open-ocean upwelling may have also been possible.

Climate

Average climate

The Paleocene climate was, much like in the Cretaceous, tropical orsubtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Köppen climate classification, climate zones to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Geographical z ...

, and the poles were temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

and ice free with an average global temperature of roughly . For comparison, the average global temperature for the period between 1951 and 1980 was . A 2019 study identified changes in orbital eccentricity

In astrodynamics, the orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a dimensionless parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values be ...

as the dominant drivers of climate between the late Cretaceous and the early Eocene.

Global deep water temperatures in the Paleocene likely ranged from , compared to in modern day. Based on the upper limit, average sea surface temperatures at 60° N and S would have been the same as deep sea temperatures, at 30° N and S about , and at the equator about . The Paleocene foraminifera assemblage globally indicates a defined deep-water thermocline

A thermocline (also known as the thermal layer or the metalimnion in lakes) is a thin but distinct layer in a large body of fluid (e.g. water, as in an ocean or lake; or air, e.g. an atmosphere) in which temperature changes more drastically wit ...

(a warmer mass of water closer to the surface sitting on top of a colder mass nearer the bottom) persisting throughout the epoch. The Atlantic foraminifera indicate a general warming of sea surface temperature–with tropical taxa present in higher latitude areas–until the Late Paleocene when the thermocline became steeper and tropical foraminifera retreated back to lower latitudes.

Early Paleocene atmospheric CO2 levels at what is now Castle Rock, Colorado, were calculated to be between 352 and 1,110 parts per million

In science and engineering, the parts-per notation is a set of pseudo-units to describe small values of miscellaneous dimensionless quantities, e.g. mole fraction or mass fraction. Since these fractions are quantity-per-quantity measures, they ...

(ppm), with a median

In statistics and probability theory, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample, a population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as "the middle" value. The basic f ...

of 616 ppm. Based on this and estimated plant-gas exchange rates and global surface temperatures, the climate sensitivity

Climate sensitivity is a measure of how much Earth's surface will cool or warm after a specified factor causes a change in its climate system, such as how much it will warm for a doubling in the atmospheric carbon dioxide () concentration. In te ...

was calculated to be +3 °C when CO2 levels doubled, compared to 7° following the formation of ice at the poles. CO2 levels alone may have been insufficient in maintaining the greenhouse climate, and some positive feedback

Positive feedback (exacerbating feedback, self-reinforcing feedback) is a process that occurs in a feedback loop which exacerbates the effects of a small disturbance. That is, the effects of a perturbation on a system include an increase in th ...

s must have been active, such as some combination of cloud, aerosol, or vegetation related processes.

The poles probably had a cool temperate climate; northern Antarctica, Australia, the southern tip of South America, what is now the US and Canada, eastern Siberia, and Europe warm temperate; middle South America, southern and northern Africa, South India, Middle America, and China arid; and northern South America, central Africa, North India, middle Siberia, and what is now the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

tropical.

Climatic events

The effects of the meteor impact and volcanism 66 mya and the climate across the K–Pg boundary were likely fleeting, and climate reverted to normal in a short time frame. The freezing temperatures probably reversed after 3 years and returned to normal within decades,sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular fo ...

aerosol

An aerosol is a suspension (chemistry), suspension of fine solid particles or liquid Drop (liquid), droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be natural or Human impact on the environment, anthropogenic. Examples of natural aerosols are fog o ...

s causing acid rain

Acid rain is rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it has elevated levels of hydrogen ions (low pH). Most water, including drinking water, has a neutral pH that exists between 6.5 and 8.5, but ...

probably dissipated after 10 years, and dust from the impact blocking out sunlight and inhibiting photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

would have lasted up to a year though potential global wildfire

A wildfire, forest fire, bushfire, wildland fire or rural fire is an unplanned, uncontrolled and unpredictable fire in an area of combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically ident ...

s raging for several years would have released more particulates