Pablo Neruda on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto (12 July 1904 – 23 September 1973), better known by his

Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto was born on 12 July 1904, in Parral, Chile, a city in Linares Province, now part of the greater Maule Region, some 350 km south of

Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto was born on 12 July 1904, in Parral, Chile, a city in Linares Province, now part of the greater Maule Region, some 350 km south of

As Spain became engulfed in

As Spain became engulfed in

A few weeks after his "Yo acuso" speech in 1948, finding himself threatened with arrest, Neruda went into hiding and he and his wife were smuggled from house to house hidden by supporters and admirers for the next 13 months. While in hiding, Senator Neruda was removed from office and, in September 1948, the Communist Party was banned altogether under the ''Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia'', called by critics the ''Ley Maldita'' (Accursed Law), which eliminated over 26,000 people from the electoral registers, thus stripping them of their right to vote. Neruda later moved to

A few weeks after his "Yo acuso" speech in 1948, finding himself threatened with arrest, Neruda went into hiding and he and his wife were smuggled from house to house hidden by supporters and admirers for the next 13 months. While in hiding, Senator Neruda was removed from office and, in September 1948, the Communist Party was banned altogether under the ''Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia'', called by critics the ''Ley Maldita'' (Accursed Law), which eliminated over 26,000 people from the electoral registers, thus stripping them of their right to vote. Neruda later moved to

By 1952, the González Videla government was on its last legs, weakened by corruption scandals. The Chilean Socialist Party was in the process of nominating Salvador Allende as its candidate for the September 1952 presidential elections and was keen to have the presence of Neruda, by now Chile's most prominent left-wing literary figure, to support the campaign. Neruda returned to Chile in August of that year and rejoined Delia del Carril, who had traveled ahead of him some months earlier, but the marriage was crumbling. Del Carril eventually learned of his affair with Matilde Urrutia and he sent her back to Chile in 1955. She convinced the Chilean officials to lift his arrest, allowing Urrutia and Neruda to go to Capri, Italy. Now united with Urrutia, Neruda would, aside from many foreign trips and a stint as Allende's ambassador to France from 1970 to 1973, spend the rest of his life in Chile.

By this time, Neruda enjoyed worldwide fame as a poet, and his books were being translated into virtually all the major languages of the world. He vigorously denounced the United States during the

By 1952, the González Videla government was on its last legs, weakened by corruption scandals. The Chilean Socialist Party was in the process of nominating Salvador Allende as its candidate for the September 1952 presidential elections and was keen to have the presence of Neruda, by now Chile's most prominent left-wing literary figure, to support the campaign. Neruda returned to Chile in August of that year and rejoined Delia del Carril, who had traveled ahead of him some months earlier, but the marriage was crumbling. Del Carril eventually learned of his affair with Matilde Urrutia and he sent her back to Chile in 1955. She convinced the Chilean officials to lift his arrest, allowing Urrutia and Neruda to go to Capri, Italy. Now united with Urrutia, Neruda would, aside from many foreign trips and a stint as Allende's ambassador to France from 1970 to 1973, spend the rest of his life in Chile.

By this time, Neruda enjoyed worldwide fame as a poet, and his books were being translated into virtually all the major languages of the world. He vigorously denounced the United States during the  In 1966, Neruda was invited to attend an

In 1966, Neruda was invited to attend an

In 1970, Neruda was nominated as a candidate for the Chilean presidency, but ended up giving his support to Salvador Allende, who later won the

In 1970, Neruda was nominated as a candidate for the Chilean presidency, but ended up giving his support to Salvador Allende, who later won the  In 1971, Neruda was awarded the

In 1971, Neruda was awarded the  It was originally reported that, on the evening of 23 September 1973, at Santiago's Santa María Clinic, Neruda had died of heart failure;

However, "(t)hat day, he was alone in the hospital where he had already spent five days. His health was declining and he called his wife, Matilde Urrutia, so she could come immediately because they were giving him something and he wasn’t feeling good." On 12 May 2011, the Mexican magazine ''Proceso'' published an interview with his former driver Manuel Araya Osorio in which he states that he was present when Neruda called his wife and warned that he believed Pinochet had ordered a doctor to kill him, and that he had just been given an injection in his stomach. He would die six-and-a-half hours later. Even reports from the pro-Pinochet El Mercurio newspaper the day after Neruda's death refer to an injection given immediately before Neruda's death. According to an official Chilean Interior Ministry report prepared in March 2015 for the court investigation into Neruda's death, "he was either given an injection or something orally" at the Santa María Clinic "which caused his death six-and-a-half hours later. The 1971 Nobel laureate was scheduled to fly to Mexico where he may have been planning to lead a government in exile that would denounce General Augusto Pinochet, who led the coup against Allende on September 11, according to his friends, researchers, and other political observers". The funeral took place amidst a massive

It was originally reported that, on the evening of 23 September 1973, at Santiago's Santa María Clinic, Neruda had died of heart failure;

However, "(t)hat day, he was alone in the hospital where he had already spent five days. His health was declining and he called his wife, Matilde Urrutia, so she could come immediately because they were giving him something and he wasn’t feeling good." On 12 May 2011, the Mexican magazine ''Proceso'' published an interview with his former driver Manuel Araya Osorio in which he states that he was present when Neruda called his wife and warned that he believed Pinochet had ordered a doctor to kill him, and that he had just been given an injection in his stomach. He would die six-and-a-half hours later. Even reports from the pro-Pinochet El Mercurio newspaper the day after Neruda's death refer to an injection given immediately before Neruda's death. According to an official Chilean Interior Ministry report prepared in March 2015 for the court investigation into Neruda's death, "he was either given an injection or something orally" at the Santa María Clinic "which caused his death six-and-a-half hours later. The 1971 Nobel laureate was scheduled to fly to Mexico where he may have been planning to lead a government in exile that would denounce General Augusto Pinochet, who led the coup against Allende on September 11, according to his friends, researchers, and other political observers". The funeral took place amidst a massive

"Ode To Age" ("Odă Bătrâneţii")

* Name dropped in the song La Vie Boheme from the 1996 musical ''

Mark Eisner

* ''Book of Twilight'' (

''Pablo Neruda: The Poet's Calling [The Biography of a Poet],''

b

Mark Eisner

New York, Ecco/HarperCollins 2018 * ''Translating Neruda: The Way to Macchu Picchu'' John Felstiner 1980 * ''The poetry of Pablo Neruda''. Costa, René de., 1979 * ''Pablo Neruda: Memoirs'' (''Confieso que he vivido: Memorias'') / tr. St. Martin, Hardie, 1977

Profile at the Poetry Foundation

Profile at Poets.org with poems and articles

* including the Nobel Lecture, 13 December 1971 ''Towards the Splendid City'' *

NPR Morning Edition on Neruda's Centennial

12 July 2004 (audio 4 mins)

"Pablo Neruda's 'Poems of the Sea'"

5 April 2004 (Audio, 8 mins)

"The ecstasist: Pablo Neruda and his passions"

''

Documentary-in-progress on Neruda, funded by Latino Public Broadcasting

site features interviews from Isabel Allende and others, bilingual poems

Poems of Pablo Neruda

"What We Can Learn From Neruda's Poetry of Resistance"

''

Pablo Neruda recorded at the Library of Congress for the Hispanic Division’s audio literary archive on June 20, 1966

{{DEFAULTSORT:Neruda, Pablo 1904 births 1973 deaths People from Linares Province Chilean atheists Chilean male poets Deaths from cancer in Chile Ambassadors of Chile to France Chilean diplomats Chilean Nobel laureates Communist poets Deaths from prostate cancer Nobel laureates in Literature People of the Spanish Civil War Stalin Peace Prize recipients Surrealist poets Chilean surrealist writers Communist Party of Chile politicians Members of the Senate of Chile National Prize for Literature (Chile) winners Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath laureates People from Santiago Sonneteers 20th-century Chilean poets 20th-century Chilean male writers Chilean communists Death conspiracy theories Chilean expatriates in Argentina Chilean expatriates in Spain Chilean expatriates in Mexico Chilean Marxists Poet-diplomats 20th-century pseudonymous writers

pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

and, later, legal name Pablo Neruda (; ), was a Chilean poet-diplomat

Poet-diplomats are poets who have also served their countries as diplomats. The best known poet-diplomats are perhaps Geoffrey Chaucer and Thomas Wyatt; the category also includes recipients of the Nobel Prize in Literature: Ivo Andrić, Gabrie ...

and politician who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature. Neruda became known as a poet when he was 13 years old, and wrote in a variety of styles, including surrealist poems, historical epic

Epic films are a style of filmmaking with large-scale, sweeping scope, and spectacle. The usage of the term has shifted over time, sometimes designating a film genre and at other times simply synonymous with big-budget filmmaking. Like epics in ...

s, overtly political manifestos, a prose autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

, and passionate love poems such as the ones in his collection '' Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair'' (1924).

Neruda occupied many diplomatic positions in various countries during his lifetime and served a term as a Senator for the Chilean Communist Party. When President Gabriel González Videla outlawed communism in Chile in 1948, a warrant was issued for Neruda's arrest. Friends hid him for months in the basement of a house in the port city of Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, and in 1949 he escaped through a mountain pass near Maihue Lake

The Maihue Lake ( es, Lago Maihue, , Mapudungun for ''Wooden glass'') is a lake located east of Ranco Lake in the Andean mountains of southern Chile. The lake is of glacial

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval o ...

into Argentina; he would not return to Chile for more than three years. He was a close advisor to Chile's socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

President Salvador Allende, and, when he got back to Chile after accepting his Nobel Prize in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

, Allende invited him to read at the Estadio Nacional before 70,000 people.

Neruda was hospitalized with cancer in September 1973, at the time of the coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

led by Augusto Pinochet and the United States that overthrew Allende's government, but returned home after a few days when he suspected a doctor of injecting him with an unknown substance for the purpose of murdering him on Pinochet's orders. Neruda died in his house in Isla Negra on 23 September 1973, just hours after leaving the hospital. Although it was long reported that he died of heart failure, the Interior Ministry of the Chilean government issued a statement in 2015 acknowledging a Ministry document indicating the government's official position that "it was clearly possible and highly likely" that Neruda was killed as a result of "the intervention of third parties". However, an international forensic test conducted in 2013 rejected allegations that he was poisoned. It was concluded that he was suffering from prostate cancer. Pinochet, backed by elements of the armed forces, denied permission for Neruda's funeral to be made a public event, but thousands of grieving Chileans disobeyed the curfew and crowded the streets.

Neruda is often considered the national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbo ...

of Chile, and his works have been popular and influential worldwide. The Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez once called him "the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language", and the critic Harold Bloom included Neruda as one of the writers central to the Western tradition in his book '' The Western Canon''.

Early life

Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto was born on 12 July 1904, in Parral, Chile, a city in Linares Province, now part of the greater Maule Region, some 350 km south of

Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto was born on 12 July 1904, in Parral, Chile, a city in Linares Province, now part of the greater Maule Region, some 350 km south of Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

. His father, José del Carmen Reyes Morales, was a railway employee, and his mother Rosa Neftalí Basoalto Opazo was a school teacher who died two months after he was born on 14 September. On 26 September, he was baptized in the parish of San Jose de Parral. Neruda grew up in Temuco with Rodolfo and a half-sister, Laura Herminia "Laurita", from one of his father's extramarital affairs (her mother was Aurelia Tolrà, a Catalan woman). He composed his first poems in the winter of 1914. Neruda was an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

.

Literary career

Neruda's father opposed his son's interest in writing and literature, but he received encouragement from others, including the future Nobel Prize winner Gabriela Mistral, who headed the local school. On 18 July 1917, at the age of 13, he published his first work, an essay titled "Entusiasmo y perseverancia" ("Enthusiasm and Perseverance") in the local daily newspaper ''La Mañana'', and signed it Neftalí Reyes. From 1918 to mid-1920, he published numerous poems, such as "Mis ojos" ("My eyes"), and essays in local magazines as Neftalí Reyes. In 1919, he participated in the literary contest Juegos Florales del Maule and won third place for his poem "Comunión ideal" or "Nocturno ideal". By mid-1920, when he adopted the pseudonym Pablo Neruda, he was a published author of poems, prose, and journalism. He is thought to have derived his pen name from the Czech poet Jan Neruda, though other sources say the true inspiration was Moravian violinistWilma Neruda

Wilhelmine Maria Franziska Neruda (1838–1911), also known as Wilma Norman-Neruda and Lady Hallé, was a Moravian virtuoso violinist, chamber musician, and teacher.

Life and career

Born in Brno, Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire, ...

, whose name appears in Arthur Conan Doyle's novel '' A Study in Scarlet''.

In 1921, at the age of 16, Neruda moved to Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

to study French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

at the Universidad de Chile with the intention of becoming a teacher. However, he was soon devoting all his time to writing poems and with the help of well-known writer Eduardo Barrios, he managed to meet and impress Don Carlos George Nascimento, the most important publisher in Chile at the time. In 1923, his first volume of verse, '' Crepusculario'' (''Book of Twilights''), was published by Editorial Nascimento, followed the next year by '' Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada'' (''Twenty Love Poems and A Desperate Song''), a collection of love poems that was controversial for its eroticism, especially considering its author's young age. Both works were critically acclaimed and have been translated into many languages. A second edition of ''Veinte poemas'' appeared in 1932. In the years since its publication, millions of copies have been sold and it became Neruda's best-known work. Almost 100 years later, Veinte Poemas is still the best-selling poetry book in the Spanish language. By the age of 20, Neruda had established an international reputation as a poet but faced poverty.

In 1926, he published the collection ''Tentativa del hombre infinito'' (''The Attempt of the Infinite Man'') and the novel ''El habitante y su esperanza'' (''The Inhabitant and His Hope'').Tarn (1975) p. 15 In 1927, out of financial desperation, he took an honorary consulship in Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

, the capital of the British colony of Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

, then administered from New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament Hous ...

as a province of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. Later, mired in isolation and loneliness, he worked in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

(Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

), Batavia (Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

), and Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

. In Batavia the following year, he met and married (6 December 1930) his first wife, a Dutch bank employee named Marijke Antonieta Hagenaar Vogelzang (born as Marietje Antonia Hagenaar), known as Maruca. While he was in the diplomatic service, Neruda read large amounts of verse, experimented with many different poetic forms, and wrote the first two volumes of ''Residencia en la Tierra'', which includes many surrealist poems.

Diplomatic and political career

Spanish Civil War

After returning to Chile, Neruda was given diplomatic posts inBuenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

and then Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Spain.Tarn (1975) p. 16 He later succeeded Gabriela Mistral as consul in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, where he became the center of a lively literary circle, befriending such writers as Rafael Alberti

Rafael Alberti Merello (16 December 1902 – 28 October 1999) was a Spanish poet, a member of the Generation of '27. He is considered one of the greatest literary figures of the so-called ''Silver Age'' of Spanish Literature, and he won numero ...

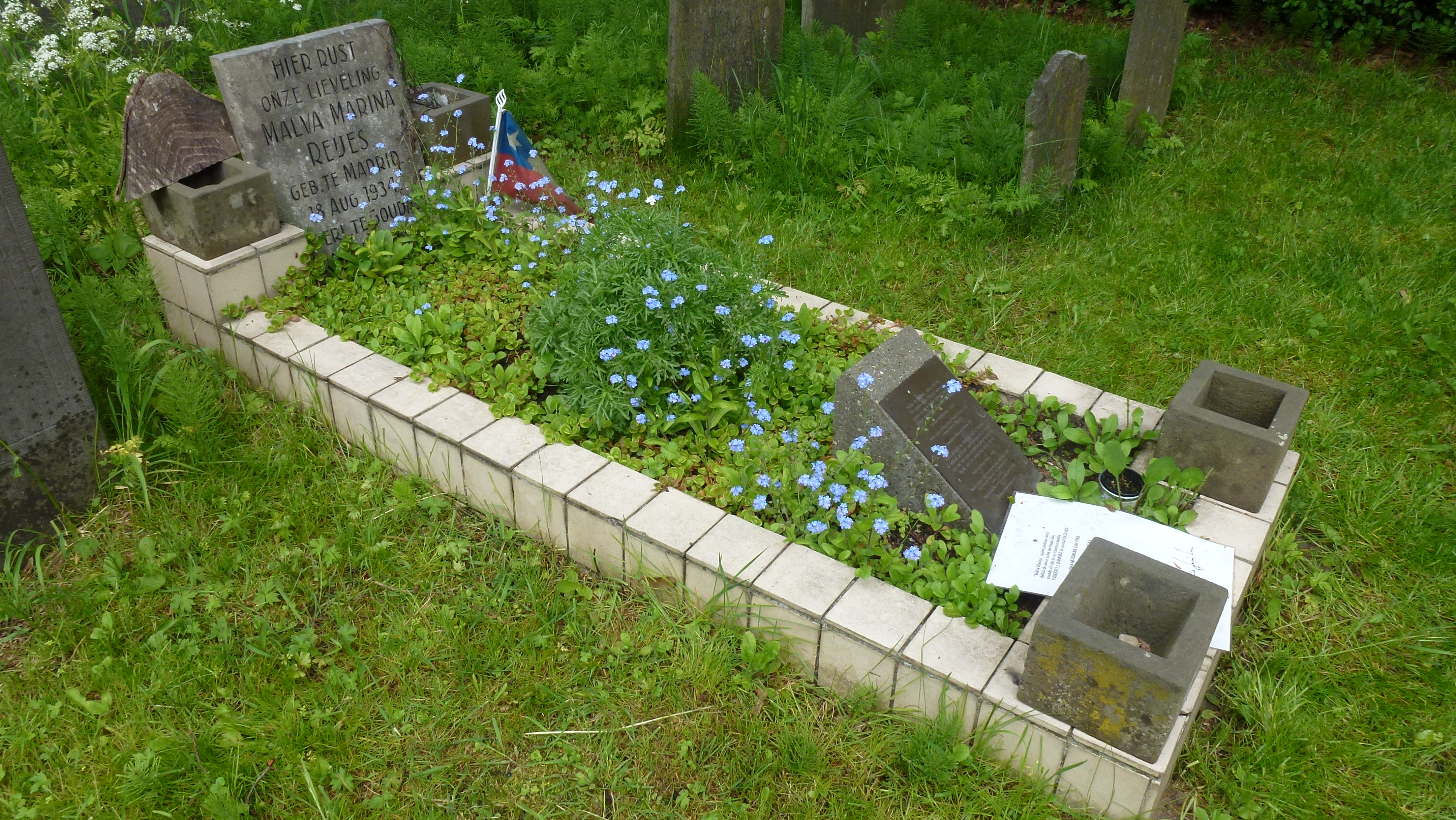

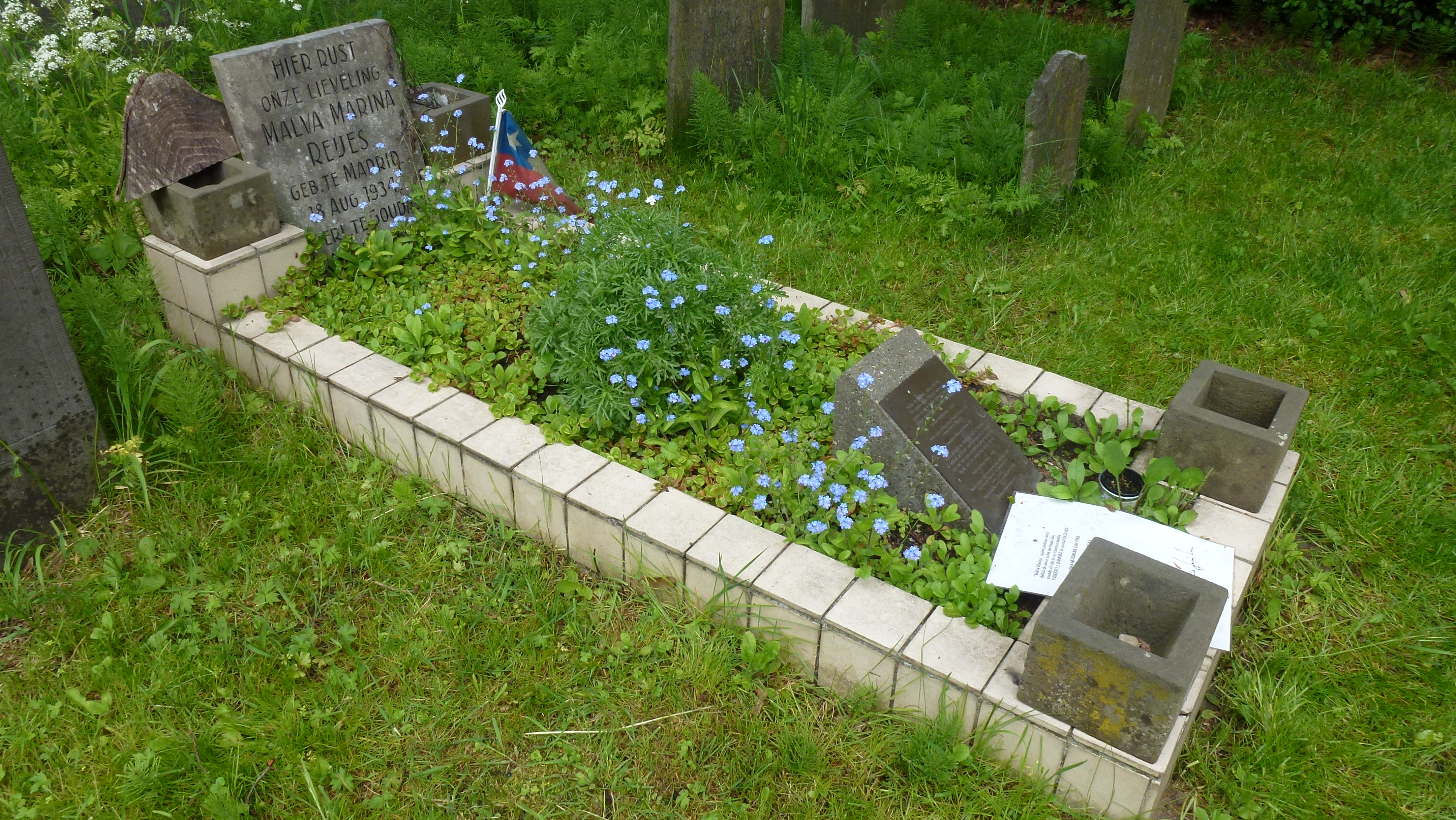

, Federico García Lorca, and the Peruvian poet César Vallejo. His only offspring, his daughter Malva Marina (Trinidad) Reyes, was born in Madrid in 1934. She was plagued with severe health problems, especially suffering from hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is a condition in which an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) occurs within the brain. This typically causes increased pressure inside the skull. Older people may have headaches, double vision, poor balance, urinary i ...

. She died in 1943 (nine years old), having spent most of her short life with a foster family in the Netherlands after Neruda ignored and abandoned her, forcing her mother to take what jobs she could. Half that time was during the Nazi occupation of Holland, when the Nazi mentality on birth defects denoted genetic inferiority at best. During this period, Neruda became estranged from his wife and instead began a relationship with , an aristocratic Argentine artist who was 20 years his senior.

As Spain became engulfed in

As Spain became engulfed in civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, Neruda became intensely politicized for the first time. His experiences during the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath moved him away from privately focused work in the direction of collective obligation. Neruda became an ardent Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

for the rest of his life. The radical leftist politics of his literary friends, as well as that of del Carril, were contributing factors, but the most important catalyst was the execution of García Lorca by forces loyal to the dictator Francisco Franco. By means of his speeches and writings, Neruda threw his support behind the Spanish Republic, publishing the collection ''España en el corazón'' (''Spain in Our Hearts'', 1938). He lost his post as consul due to his political militancy. In July 1937, he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the war in Spain, held in Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

and Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

and attended by many writers including André Malraux, Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century f ...

and Stephen Spender.

Neruda's marriage to Vogelzang broke down and he eventually obtained a divorce in Mexico in 1943. His estranged wife moved to Monte Carlo

Monte Carlo (; ; french: Monte-Carlo , or colloquially ''Monte-Carl'' ; lij, Munte Carlu ; ) is officially an administrative area of the Principality of Monaco, specifically the ward of Monte Carlo/Spélugues, where the Monte Carlo Casino is ...

to escape the hostilities in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and then to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

with their very ill only child, and he never saw either of them again. After leaving his wife, Neruda lived with Delia del Carril in France, eventually marrying her (shortly after his divorce) in Tetecala in 1943; however, his new marriage was not recognized by Chilean authorities as his divorce from Vogelzang was deemed illegal.

Following the election of Pedro Aguirre Cerda (whom Neruda supported) as President of Chile in 1938, Neruda was appointed special Consul for Spanish emigrants in Paris. There he was responsible for what he called "the noblest mission I have ever undertaken": transporting 2,000 Spanish refugees who had been housed by the French in squalid camps to Chile on an old ship called the ''Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

''. Neruda is sometimes charged with having selected only fellow Communists for emigration, to the exclusion of others who had fought on the side of the Republic. Many Republicans and Anarchists were killed during the German invasion and occupation. Others deny these accusations, pointing out that Neruda chose only a few hundred of the 2,000 refugees personally; the rest were selected by the Service for the Evacuation of Spanish Refugees set up by Juan Negrín

Juan Negrín López (; 3 February 1892 – 12 November 1956) was a Spanish politician and physician. He was a leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and served as finance minister and ...

, President of the Spanish Republican Government in Exile.

Mexican appointment

Neruda's next diplomatic post was as Consul General inMexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

from 1940 to 1943.Tarn (1975) p. 17 While he was there, he married del Carril, and learned that his daughter Malva had died, aged eight, in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands.

In 1940, after the failure of an assassination attempt against Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, Neruda arranged a Chilean visa for the Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Alfaro Siqueiros (born José de Jesús Alfaro Siqueiros; December 29, 1896 – January 6, 1974) was a Mexican social realist painter, best known for his large public murals using the latest in equipment, materials and technique. Along with ...

, who was accused of having been one of the conspirators in the assassination. Neruda later said that he did it at the request of the Mexican President, Manuel Ávila Camacho. This enabled Siqueiros, then jailed, to leave Mexico for Chile, where he stayed in Neruda's private residence. In exchange for Neruda's assistance, Siqueiros spent over a year painting a mural in a school in Chillán

Chillán () is the capital city of the Ñuble Region in the Diguillín Province of Chile located about south of the country's capital, Santiago, near the geographical center of the country. It is the capital of the new Ñuble Region since 6 S ...

. Neruda's relationship with Siqueiros attracted criticism, but Neruda dismissed the allegation that his intent had been to help an assassin as "sensationalist politico-literary harassment".

Return to Chile

In 1943, after his return to Chile, Neruda made a tour ofPeru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

, where he visited Machu Picchu, an experience that later inspired ''Alturas de Macchu Picchu'', a book-length poem in 12 parts that he completed in 1945 and which expressed his growing awareness of, and interest in, the ancient civilizations of the Americas. He explored this theme further in '' Canto General'' (1950). In ''Alturas'', Neruda celebrated the achievement of Machu Picchu, but also condemned the slavery that had made it possible. In ''Canto XII'', he called upon the dead of many centuries to be born again and to speak through him. Martín Espada, poet and professor of creative writing at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst, UMass) is a public research university in Amherst, Massachusetts and the sole public land-grant university in Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Founded in 1863 as an agricultural college, ...

, has hailed the work as a masterpiece, declaring that "there is no greater political poem".

Communism

Bolstered by his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, Neruda, like many left-leaning intellectuals of his generation, came to admire theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, partly for the role it played in defeating Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and partly because of an idealist interpretation of Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

doctrine. This is echoed in poems such as "Canto a Stalingrado" (1942) and "Nuevo canto de amor a Stalingrado" (1943). In 1953, Neruda was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize. Upon Stalin's death that same year, Neruda wrote an ode to him, as he also wrote poems in praise of Fulgencio Batista, "Saludo a Batista" ("Salute to Batista"), and later to Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

. His fervent Stalinism eventually drove a wedge between Neruda and his long-time friend Octavio Paz, who commented that "Neruda became more and more Stalinist, while I became less and less enchanted with Stalin." Their differences came to a head after the Nazi-Soviet Ribbentrop–Molotov Pact of 1939, when they almost came to blows in an argument over Stalin. Although Paz still considered Neruda "The greatest poet of his generation", in an essay on Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repr ...

he wrote that when he thinks of "Neruda and other famous Stalinist writers and poets, I feel the gooseflesh that I get from reading certain passages of the '' Inferno''. No doubt they began in good faith ..but insensibly, commitment by commitment, they saw themselves becoming entangled in a mesh of lies, falsehoods, deceits and perjuries, until they lost their souls." On 15 July 1945, at Pacaembu Stadium

Estádio Municipal Paulo Machado de Carvalho, colloquially known as Estádio do Pacaembu (), is an Art Deco stadium in São Paulo, located in the Pacaembu neighborhood. The stadium is owned by the Municipal Prefecture of São Paulo. The stadium w ...

in São Paulo

São Paulo (, ; Portuguese for ' Saint Paul') is the most populous city in Brazil, and is the capital of the state of São Paulo, the most populous and wealthiest Brazilian state, located in the country's Southeast Region. Listed by the GaW ...

, Brazil, Neruda read to 100,000 people in honor of the Communist revolutionary leader Luís Carlos Prestes

Luís Carlos Prestes (January 3, 1898 – March 7, 1990) was a Brazilian revolutionary and politician who served as the general-secretary of the Brazilian Communist Party from 1943 to 1980 and a senator for the Federal District from 1946 to 1948 ...

.

Neruda also called Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

the "great genius of this century", and in a speech he gave on 5 June 1946, he paid tribute to the late Soviet leader Mikhail Kalinin, who for Neruda was "man of noble life", "the great constructor of the future", and "a comrade in arms of Lenin and Stalin".

Neruda later came to regret his fondness for the Soviet Union, explaining that "in those days, Stalin seemed to us the conqueror who had crushed Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's armies."Feinstein (2005) pp. 312–313 Of a subsequent visit to China in 1957, Neruda wrote: "What has estranged me from the Chinese revolutionary process has not been Mao Tse-tung

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC ...

but Mao Tse-tungism." He dubbed this Mao Tse-Stalinism: "the repetition of a cult of a Socialist deity." Despite his disillusionment with Stalin, Neruda never lost his essential faith in Communist theory and remained loyal to "the Party". Anxious not to give ammunition to his ideological enemies, he would later refuse publicly to condemn the Soviet repression of dissident writers like Boris Pasternak and Joseph Brodsky

Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky (; russian: link=no, Иосиф Александрович Бродский ; 24 May 1940 – 28 January 1996) was a Russian and American poet and essayist.

Born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), USSR in 1940, ...

, an attitude with which even some of his staunchest admirers disagreed.

On 4 March 1945, Neruda was elected a Communist Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

for the northern provinces of Antofagasta and Tarapacá in the Atacama Desert. He officially joined the Communist Party of Chile four months later. In 1946, the Radical Party's presidential candidate, Gabriel González Videla, asked Neruda to act as his campaign manager. González Videla was supported by a coalition of left-wing parties and Neruda fervently campaigned on his behalf. Once in office, however, González Videla turned against the Communist Party and issued the '' Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia'' (Law of Permanent Defense of the Democracy). The breaking point for Senator Neruda was the violent repression of a Communist-led miners' strike in Lota Lota may refer to:

Places

* Lota (crater), a crater on Mars

* Lota, Chile, a city and commune in Chile

* Lota, Punjab, village in Pakistan

*Lota, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Australia

**Lota railway station, a station on the Cleveland line

* ...

in October 1947, when striking workers were herded into island military prisons and a concentration camp in the town of Pisagua. Neruda's criticism of González Videla culminated in a dramatic speech in the Chilean senate on 6 January 1948, which became known as "Yo acuso" ("I accuse"), in the course of which he read out the names of the miners and their families who were imprisoned at the concentration camp.

In 1959, Neruda was present as Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

was honored at a welcoming ceremony offered by the Central University of Venezuela

The Central University of Venezuela (Spanish: ''Universidad Central de Venezuela''; UCV) is a public university of Venezuela located in Caracas. It is widely held to be the highest ranking institution in the country, and it also ranks 18th in ...

where he spoke to a massive gathering of students and read his Canto a Bolivar. Luis Báez summarized what Neruda said: "In this painful and victorious hour that the peoples of America live, my poem with changes of place, can be understood directed to Fidel Castro, because in the struggles for freedom the fate of a Man to give confidence to the spirit of greatness in the history of our peoples".

During the late 1960s, Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo (; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator, as well as a key figure in Spanish-language and international literature. His best-known b ...

was asked for his opinion of Pablo Neruda. Borges stated, "I think of him as a very fine poet, a very fine poet. I don't admire him as a man, I think of him as a very mean man." He said that Neruda had not spoken out against Argentine President Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine Army general and politician. After serving in several government positions, including Minister of Labour and Vice President of a military dictatorship, he was elected ...

because he was afraid to risk his reputation, noting "I was an Argentine poet, he was a Chilean poet, he's on the side of the Communists; I'm against them. So I felt he was behaving very wisely in avoiding a meeting that would have been quite uncomfortable for both of us."

Hiding and exile, 1948–1952

A few weeks after his "Yo acuso" speech in 1948, finding himself threatened with arrest, Neruda went into hiding and he and his wife were smuggled from house to house hidden by supporters and admirers for the next 13 months. While in hiding, Senator Neruda was removed from office and, in September 1948, the Communist Party was banned altogether under the ''Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia'', called by critics the ''Ley Maldita'' (Accursed Law), which eliminated over 26,000 people from the electoral registers, thus stripping them of their right to vote. Neruda later moved to

A few weeks after his "Yo acuso" speech in 1948, finding himself threatened with arrest, Neruda went into hiding and he and his wife were smuggled from house to house hidden by supporters and admirers for the next 13 months. While in hiding, Senator Neruda was removed from office and, in September 1948, the Communist Party was banned altogether under the ''Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia'', called by critics the ''Ley Maldita'' (Accursed Law), which eliminated over 26,000 people from the electoral registers, thus stripping them of their right to vote. Neruda later moved to Valdivia

Valdivia (; Mapuche: Ainil) is a city and commune in southern Chile, administered by the Municipality of Valdivia. The city is named after its founder Pedro de Valdivia and is located at the confluence of the Calle-Calle, Valdivia, and Cau-Ca ...

in southern Chile. From Valdivia he moved to ''Fundo Huishue'', a forestry estate in the vicinity of Huishue Lake

Huishue Lake ( es, Lago Huishue, ), Mapudungun for bad place to live, is located in the Andes of the Lago Ranco commune in southern Chile. More precisely the lake is located 10 km south of Maihue Lake (the drainage basin to which it belongs), ...

. Neruda's life underground ended in March 1949 when he fled over the Lilpela Pass Ipela or Lilpela ( es, Paso Lilpela) is a mountain pass through the Andes along the border between Chile and Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half ...

in the Andes Mountains

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

to Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

on horseback. He would dramatically recount his escape from Chile in his Nobel Prize lecture.

Once out of Chile, he spent the next three years in exile. In Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, Neruda took advantage of the slight resemblance between him and his friend, the future Nobel Prize-winning novelist and cultural attaché to the Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by Hon ...

n embassy Miguel Ángel Asturias, to travel to Europe using Asturias' passport.Feinstein (2005) pp. 236–7 Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

arranged his entrance into Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

and Neruda made a surprise appearance there to a stunned World Congress of Peace Forces, while the Chilean government denied that the poet could have escaped the country. Neruda spent those three years traveling extensively throughout Europe as well as taking trips to India, China, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, and the Soviet Union. His trip to Mexico in late 1949 was lengthened due to a serious bout of phlebitis.Feinstein (2005) p. 290 A Chilean singer named Matilde Urrutia was hired to care for him and they began an affair that would, years later, culminate in marriage. During his exile, Urrutia would travel from country to country shadowing him and they would arrange meetings whenever they could. Matilde Urrutia was the muse for '' Los versos del capitán'', a book of poetry which Neruda later published anonymously in 1952.

While in Mexico, Neruda also published his lengthy epic poem '' Canto General'', a Whitmanesque catalog of the history, geography, and flora and fauna of South America, accompanied by Neruda's observations and experiences. Many of them dealt with his time underground in Chile, which is when he composed much of the poem. In fact, he had carried the manuscript with him during his escape on horseback. A month later, a different edition of 5,000 copies was boldly published in Chile by the outlawed Communist Party based on a manuscript Neruda had left behind. In Mexico, he was granted honorary Mexican citizenship.Tarn (1975) p. 22 Neruda's 1952 stay in a villa owned by Italian historian Edwin Cerio on the island of Capri was fictionalized in Antonio Skarmeta

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular ...

's 1985 novel ''Ardiente Paciencia'' (''Ardent Patience'', later known as ''El cartero de Neruda'', or ''Neruda's Postman''), which inspired the popular film ''Il Postino

''Il Postino: The Postman'' ( it, Il postino, lit, 'The Postman'; the title used for the original US release) is a 1994 comedy-drama film co-written by and starring Massimo Troisi and directed by English filmmaker Michael Radford. Based on th ...

'' (1994).Feinstein (2005) p. 278

Second return to Chile

By 1952, the González Videla government was on its last legs, weakened by corruption scandals. The Chilean Socialist Party was in the process of nominating Salvador Allende as its candidate for the September 1952 presidential elections and was keen to have the presence of Neruda, by now Chile's most prominent left-wing literary figure, to support the campaign. Neruda returned to Chile in August of that year and rejoined Delia del Carril, who had traveled ahead of him some months earlier, but the marriage was crumbling. Del Carril eventually learned of his affair with Matilde Urrutia and he sent her back to Chile in 1955. She convinced the Chilean officials to lift his arrest, allowing Urrutia and Neruda to go to Capri, Italy. Now united with Urrutia, Neruda would, aside from many foreign trips and a stint as Allende's ambassador to France from 1970 to 1973, spend the rest of his life in Chile.

By this time, Neruda enjoyed worldwide fame as a poet, and his books were being translated into virtually all the major languages of the world. He vigorously denounced the United States during the

By 1952, the González Videla government was on its last legs, weakened by corruption scandals. The Chilean Socialist Party was in the process of nominating Salvador Allende as its candidate for the September 1952 presidential elections and was keen to have the presence of Neruda, by now Chile's most prominent left-wing literary figure, to support the campaign. Neruda returned to Chile in August of that year and rejoined Delia del Carril, who had traveled ahead of him some months earlier, but the marriage was crumbling. Del Carril eventually learned of his affair with Matilde Urrutia and he sent her back to Chile in 1955. She convinced the Chilean officials to lift his arrest, allowing Urrutia and Neruda to go to Capri, Italy. Now united with Urrutia, Neruda would, aside from many foreign trips and a stint as Allende's ambassador to France from 1970 to 1973, spend the rest of his life in Chile.

By this time, Neruda enjoyed worldwide fame as a poet, and his books were being translated into virtually all the major languages of the world. He vigorously denounced the United States during the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

and later in the decade he likewise repeatedly condemned the U.S. for its involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. But being one of the most prestigious and outspoken left-wing intellectuals alive, he also attracted opposition from ideological opponents. The Congress for Cultural Freedom

The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was an anti-communist advocacy group founded in 1950. At its height, the CCF was active in thirty-five countries. In 1966 it was revealed that the CIA was instrumental in the establishment and funding of the ...

, an anti-communist organization covertly established and funded by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

, adopted Neruda as one of its primary targets and launched a campaign to undermine his reputation, reviving the old claim that he had been an accomplice in the attack on Leon Trotsky in Mexico City in 1940.Feinstein (2005) p. 487 The campaign became more intense when it became known that Neruda was a candidate for the 1964 Nobel Prize, which was eventually awarded to Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and lite ...

Feinstein (2005) pp. 334–5 (who rejected it).

In 1966, Neruda was invited to attend an

In 1966, Neruda was invited to attend an International PEN

PEN International (known as International PEN until 2010) is a worldwide association of writers, founded in London in 1921 to promote friendship and intellectual co-operation among writers everywhere. The association has autonomous Internatio ...

conference in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.Feinstein (2005) pp. 341–5 Officially, he was barred from entering the U.S. because he was a communist, but the conference organizer, playwright Arthur Miller, eventually prevailed upon the Johnson

Johnson is a surname of Anglo-Norman origin meaning "Son of John". It is the second most common in the United States and 154th most common in the world. As a common family name in Scotland, Johnson is occasionally a variation of ''Johnston'', a ...

Administration to grant Neruda a visa. Neruda gave readings to packed halls, and even recorded some poems for the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

. Miller later opined that Neruda's adherence to his communist ideals of the 1930s was a result of his protracted exclusion from "bourgeois society". Due to the presence of many Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

writers, Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes later wrote that the PEN conference marked a "beginning of the end" of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

.

Upon Neruda's return to Chile, he stopped in Peru, where he gave readings to enthusiastic crowds in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

and Arequipa

Arequipa (; Aymara and qu, Ariqipa) is a city and capital of province and the eponymous department of Peru. It is the seat of the Constitutional Court of Peru and often dubbed the "legal capital of Peru". It is the second most populated city ...

and was received by President Fernando Belaúnde Terry. However, this visit also prompted an unpleasant backlash; because the Peruvian government had come out against the government of Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, July 1966 saw more than 100 Cuban intellectuals retaliate against the poet by signing a letter that charged Neruda with colluding with the enemy, calling him an example of the "tepid, pro-Yankee revisionism" then prevalent in Latin America. The affair was particularly painful for Neruda because of his previous outspoken support for the Cuban revolution, and he never visited the island again, even after receiving an invitation in 1968.

After the death of Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

in Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

in 1967, Neruda wrote several articles regretting the loss of a "great hero".Feinstein (2005) p. 326 At the same time, he told his friend Aida Figueroa not to cry for Che, but for Luis Emilio Recabarren

Luis Emilio Recabarren Serrano (; July 6, 1876 – December 19, 1924) was a Chilean political figure. He was elected several times as deputy, and was the driving force behind the worker's movement in Chile.

Early life

Recabarren was born in ...

, the father of the Chilean communist movement who preached a pacifist revolution over Che's violent ways.

Last years and death

In 1970, Neruda was nominated as a candidate for the Chilean presidency, but ended up giving his support to Salvador Allende, who later won the

In 1970, Neruda was nominated as a candidate for the Chilean presidency, but ended up giving his support to Salvador Allende, who later won the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operat ...

and was inaugurated in 1970 as Chile's first democratically elected socialist head of state.Feinstein (2005) p. 367 Shortly thereafter, Allende appointed Neruda the Chilean ambassador to France, lasting from 1970 to 1972; his final diplomatic posting. During his stint in Paris, Neruda helped to renegotiate the external debt of Chile, billions owed to European and American banks, but within months of his arrival in Paris his health began to deteriorate. Neruda returned to Chile two-and-a-half years later due to his failing health.

In 1971, Neruda was awarded the

In 1971, Neruda was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

, a decision that did not come easily because some of the committee members had not forgotten Neruda's past praise of Stalinist dictatorship. But his Swedish translator, Artur Lundkvist

Nils Artur Lundkvist (3 March 1906 – 11 December 1991) was a Swedish writer, poet and literary critic. He was a member of the Swedish Academy from 1968.

Artur Lundkvist published around 80 books, including poetry, prose poems, essays, short ...

, did his best to ensure the Chilean received the prize.Feinstein (2005) p. 333 "A poet," Neruda stated in his Stockholm speech of acceptance of the Nobel Prize, "is at the same time a force for solidarity and for solitude." The following year Neruda was awarded the prestigious Golden Wreath Award at the Struga Poetry Evenings.

As the coup d'état of 1973 unfolded, Neruda was diagnosed with prostate cancer. The military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet saw Neruda's hopes for Chile destroyed. Shortly thereafter, during a search of the house and grounds at Isla Negra by Chilean armed forces at which Neruda was reportedly present, the poet famously remarked: "Look around – there's only one thing of danger for you here – poetry."Feinstein (2005) p. 413

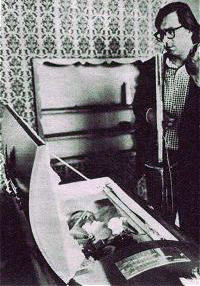

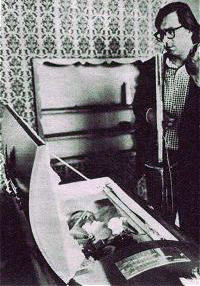

It was originally reported that, on the evening of 23 September 1973, at Santiago's Santa María Clinic, Neruda had died of heart failure;

However, "(t)hat day, he was alone in the hospital where he had already spent five days. His health was declining and he called his wife, Matilde Urrutia, so she could come immediately because they were giving him something and he wasn’t feeling good." On 12 May 2011, the Mexican magazine ''Proceso'' published an interview with his former driver Manuel Araya Osorio in which he states that he was present when Neruda called his wife and warned that he believed Pinochet had ordered a doctor to kill him, and that he had just been given an injection in his stomach. He would die six-and-a-half hours later. Even reports from the pro-Pinochet El Mercurio newspaper the day after Neruda's death refer to an injection given immediately before Neruda's death. According to an official Chilean Interior Ministry report prepared in March 2015 for the court investigation into Neruda's death, "he was either given an injection or something orally" at the Santa María Clinic "which caused his death six-and-a-half hours later. The 1971 Nobel laureate was scheduled to fly to Mexico where he may have been planning to lead a government in exile that would denounce General Augusto Pinochet, who led the coup against Allende on September 11, according to his friends, researchers, and other political observers". The funeral took place amidst a massive

It was originally reported that, on the evening of 23 September 1973, at Santiago's Santa María Clinic, Neruda had died of heart failure;

However, "(t)hat day, he was alone in the hospital where he had already spent five days. His health was declining and he called his wife, Matilde Urrutia, so she could come immediately because they were giving him something and he wasn’t feeling good." On 12 May 2011, the Mexican magazine ''Proceso'' published an interview with his former driver Manuel Araya Osorio in which he states that he was present when Neruda called his wife and warned that he believed Pinochet had ordered a doctor to kill him, and that he had just been given an injection in his stomach. He would die six-and-a-half hours later. Even reports from the pro-Pinochet El Mercurio newspaper the day after Neruda's death refer to an injection given immediately before Neruda's death. According to an official Chilean Interior Ministry report prepared in March 2015 for the court investigation into Neruda's death, "he was either given an injection or something orally" at the Santa María Clinic "which caused his death six-and-a-half hours later. The 1971 Nobel laureate was scheduled to fly to Mexico where he may have been planning to lead a government in exile that would denounce General Augusto Pinochet, who led the coup against Allende on September 11, according to his friends, researchers, and other political observers". The funeral took place amidst a massive police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

presence, and mourners took advantage of the occasion to protest against the new regime, established just a couple of weeks before. Neruda's house was broken into and his papers and books taken or destroyed.

In 1974, his ''Memoirs'' appeared under the title ''I Confess I Have Lived'', updated to the last days of the poet's life, and including a final segment describing the death of Salvador Allende during the storming of the Moneda Palace by General Pinochet and other generals – occurring only 12 days before Neruda died. Matilde Urrutia subsequently compiled and edited for publication the memoirs and possibly his final poem "Right Comrade, It's the Hour of the Garden". These and other activities brought her into conflict with Pinochet's government, which continually sought to curtail Neruda's influence on the Chilean collective consciousness. Urrutia's own memoir, ''My Life with Pablo Neruda'', was published posthumously in 1986. Manuel Araya, his Communist Party-appointed chauffeur, published a book about Neruda's final days in 2012.

Controversy

Rumored murder and exhumation

In June 2013, a Chilean judge ordered that an investigation be launched, following suggestions that Neruda had been killed by the Pinochet regime for his pro- Allende stance and political views. Neruda's driver, Manuel Araya, stated that doctors had administered poison as the poet was preparing to go into exile. In December 2011, Chile's Communist Party asked Chilean Judge Mario Carroza to order the exhumation of the remains of the poet. Carroza had been conducting probes into hundreds of deaths allegedly connected to abuses of Pinochet's regime from 1973 to 1990. Carroza's inquiry during 2011–12 uncovered enough evidence to order the exhumation in April 2013. Eduardo Contreras, a Chilean lawyer who was leading the push for a full investigation, commented: "We have world-class labs from India, Switzerland, Germany, the US, Sweden, they have all offered to do the lab work for free." The Pablo Neruda Foundation fought the exhumation under the grounds that the Araya's claims were unbelievable. In June 2013, a court order was issued to find the man who allegedly poisoned Neruda. Police were investigatingMichael Townley

Michael Vernon Townley (born December 5, 1942, in Waterloo, Iowa) is an American-born former agent of the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA), the secret police of Chile during the regime of Augusto Pinochet. In 1978, Townley pled guilty t ...

, who was facing trial for the killings of General Carlos Prats (Buenos Aires, 1974), and ex-Chancellor Orlando Letelier (Washington, 1976). The Chilean government suggested that the 2015 test showed it was "highly probable that a third party" was responsible for his death.

Test results were released on 8 November 2013 of the seven-month investigation by a 15-member forensic team. Patricio Bustos, the head of Chile's medical legal service, stated "No relevant chemical substances have been found that could be linked to Mr. Neruda's death" at the time. However, Carroza said that he was waiting for the results of the last scientific tests conducted in May (2015), which found that Neruda was infected with the ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posit ...

'' bacterium, which can be highly toxic and result in death if modified.

A team of 16 international experts led by Spanish forensic specialist Aurelio Luna from the University of Murcia announced on 20 October 2017 that "from analysis of the data we cannot accept that the poet had been in an imminent situation of death at the moment of entering the hospital" and that death from prostate cancer was not likely at the moment when he died. The team also discovered something in Neruda's remains that could possibly be a laboratory-cultivated bacteria. The results of their continuing analysis were expected in 2018. His cause of death was in fact listed as a heart attack. Scientists who exhumed Neruda's body in 2013 also backed claims that he was also suffering from prostate cancer when he died.

Feminist protests

In November 2018, the Cultural Committee of Chile's lower house voted in favour of renaming Santiago's main airport after Neruda. The decision sparked protests from feminist groups, who highlighted a passage in Neruda's memoirs describing a sexual assault of a young house maid in 1929 while stationed in Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Several feminist groups, bolstered by a growing #MeToo and anti-femicide movement stated that Neruda should not be honoured by his country, describing the passage as evidence of rape. Neruda remains a controversial figure for Chileans, and especially for Chilean feminists.Legacy

Neruda owned three houses in Chile; today they are all open to the public as museums:La Chascona

La Chascona is a house in the Barrio Bellavista of Santiago, Chile, which was owned by Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. La Chascona reflects Neruda's quirky style, in particular his love of the sea, and is now a popular destination for tourists. Nerud ...

in Santiago, La Sebastiana in Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, and Casa de Isla Negra

Casa de Isla Negra was one of Pablo Neruda's three houses in Chile. It is located at Isla Negra, a coastal area of El Quisco commune, located about 45 km south of Valparaíso and 96 km west of Santiago. It was his favourite house and ...

in Isla Negra, where he and Matilde Urrutia are buried.

A bust of Neruda stands on the grounds of the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 Apri ...

building in Washington, D.C.

In popular culture

Music

* American composer Tobias Picker set to music ''Tres Sonetos de Amor'' for baritone and orchestra * American composer Tobias Picker set to music ''Cuatro Sonetos de Amor'' for voice and piano * American singer/songwriterTaylor Swift

Taylor Alison Swift (born December 13, 1989) is an American singer-songwriter. Her discography spans multiple genres, and her vivid songwriting—often inspired by her personal life—has received critical praise and wide media coverage. Bo ...

referenced Neruda's line "love is so short, forgetting is so long" in the prologue for her 2012 album, Red.

* Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis set to music the ''Canto general''.

* Greek composer and singer Nikos Xilouris composed ''Οι Νεκρoί της Πλατείας (The dead of the Square)'' based on ''Los muertos de la plaza''.

* American composer Samuel Barber

Samuel Osmond Barber II (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981) was an American composer, pianist, conductor, baritone, and music educator, and one of the most celebrated composers of the 20th century. The music critic Donal Henahan said, "Probab ...

used Neruda's poems for his cantata ''The Lovers'' in 1971.

* Alternative rock musician Lynda Thomas

Lynda Aguirre Thomas (born 21 December 1981), known professionally as Lynda, is a Mexican musician, singer, songwriter and activist. She achieved recognition in her native Mexico during the 1990s and early 2000s. She was signed to EMI Capitol ...

released as a single the flamenco song " Ay, Ay, Ay" (2001), which is based on the book '' Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair''.

* Austrian avant-garde composer Michael Gielen set to music ''Un día sobresale'' (Ein Tag Tritt Hervor. Pentaphonie für obligates Klavier, fünf Soloinstrumente und fünf Gruppen zu je fünf Musikern mit Worten von Pablo Neruda. 1960–63).

* Native American composer Ron Warren set to music ''Quatro Sonetos de Amor'' for coloratura soprano, flute, and piano (1999), 1 from each group of sonnets in ''Cien Sonetos de Amor''. Recorded on ''Circle All Around Me'' Blue Heron Music BHM101''.''

*Puerto Rican composer Awilda Villarini used Neruda's text for her composition "Two Love Songs."

* Mexican composer Daniel Catán

Daniel Catán Porteny (April 3, 1949 – April 9, 2011) was a Mexican composer, writer and professor known particularly for his operas and his contribution of the Spanish language to the international repertory.

With a compositional style ...

wrote an opera ''Il Postino'' (2010), whose premiere production featured Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo

José Plácido Domingo Embil (born 21 January 1941) is a Spanish opera singer, conductor, and arts administrator. He has recorded over a hundred complete operas and is well known for his versatility, regularly performing in Italian, French ...

portraying Pablo Neruda.

* The Dutch composer Peter Schat used twelve poems from the Canto General for his cantata ''Canto General'' for mezzo-soprano, violin, and piano (1974), which he dedicated to the memory of the late president Salvador Allende.

* The Dutch composer Annette Kruisbrink set to music ''La Canción Desesperada'' (2000), the last poem of ''Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada''. Instrumentation: guitar and mixed choir (+ 4 soloists S/A/T/B).

* Folk rock / progressive rock group Los Jaivas, famous in Chile, used '' Las alturas de Macchu Picchu'' as the text for their album of the same name.

* Chilean composer Sergio Ortega worked closely with the poet in the musical play ''Fulgor y muerte de Joaquín Murieta'' (1967). Three decades later, Ortega expanded the piece into an opera, leaving Neruda's text intact.

*Argentine composer Julia Stilman-Lasansky

Ada Julia Stilman-Lasansky (February 3, 1935 - March 29, 2007) was an Argentinian composer who moved to the United States in 1964.

Stilman-Lasansky was born in Buenos Aires, where she studied piano with Roberto Castro and composition with Gilardo ...

(1935-2007) based her Cantata No. 3 on text by Neruda.

* Peter Lieberson

Peter Goddard Lieberson (25 October 1946 – 23 April 2011) was an American composer of contemporary classical music. His song cycles include two finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for Music: '' Rilke Songs'' and '' Neruda Songs''; the latter won t ...

composed ''Neruda Songs'' (2005) and ''Songs of Love and Sorrow'' (2010) based on ''Cien Sonetos de Amor

' ("100 Love Sonnets") is a collection of sonnets written by the Chilean poet and Nobel Laureate Pablo Neruda originally published in Argentina in 1959. Dedicated to Matilde Urrutia, later his third wife, it is divided into the four stages of ...

''.

* Jazz vocalist Luciana Souza released an album called "Neruda" (2004) featuring 10 of Neruda's poems set to the music of Federico Mompou.

* The South African musician Johnny Clegg drew heavily on Neruda in his early work with the band Juluka

Juluka was a South African music band formed in 1969 by Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu. means "sweat" in Zulu, and was the name of a bull owned by Mchunu. The band was closely associated with the mass movement against apartheid.

History

At th ...

.

* On the back of Jackson Browne's album '' The Pretender'', there is a poem by Neruda.

* Canadian rock group Red Rider named their 1983 LP/CD release ''Neruda''.

* Chilean composer Leon Schidlowsky has composed a good number of pieces using poems by Neruda. Among them, ''Carrera'', ''Caupolicán'', and ''Lautaro''.

* Pop band Sixpence None the Richer set his poem "Puedo escribir" to music on their platinum-selling self-titled album (1997).

* The group Brazilian Girls turned "Poema 15" ("Poem 15") from ''Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada (20 love poems and a song of despair'') into their song "Me gusta cuando callas" from their self-titled album.

* With permission from the Fundación Neruda, Marco Katz composed a song cycle based on the volume ''Piedras del cielo'' for voice and piano. Centaur Records CRC 3232, 2012.

* The Occitan singer Joanda composed the song ''Pablo Neruda''

* American contemporary composer Morten Lauridsen set Neruda's poem "Soneto de la noche" to music as part of his cycle "Nocturnes" from 2005.

* The opening lines for the song "Bachata Rosa" by Juan Luis Guerra was inspired by Neruda's ''The Book of Questions''.

* Ezequiel Vinao

Ezequiel is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

People

*Ezequiel Adamovsky (born 1971), Argentine historian and political activist

*Ezequiel Alejo Carboni (born 1979), is an Argentine midfielder

* Ezequiel Andreoli (born 1978), A ...

composed "Sonetos de amor" (2011) a song cycle based on Neruda's love poems.

* Ute Lemper

Ute Gertrud Lemper (; born 4 July 1963) is a German singer and actress. Her roles in musicals include playing Sally Bowles in the original Paris production of ''Cabaret'', for which she won the 1987 Molière Award for Best Newcomer, and Velm ...

co-composed the songs of "Forever

Forever or 4ever may refer to:

Film and television Films

* ''Forever'' (1921 film), an American silent film by George Fitzmaurice

* ''Forever'' (1978 film), an American made-for-television romantic drama

* ''Forever'' (1992 film), an American ...

" (2013) an album of the Love poems of Pablo Neruda

* American composer Daniel Welcher composed ''Abeja Blanca, for Mezzo-Soprano, English Horn, and Piano'' using the ''Abeja'' ''Blanca'' text from Neruda's ''Twenty Love Songs and a Song of Despair''

* Canadian rock band The Tragically Hip

The Tragically Hip, often referred to simply as the Hip, were a Canadian rock band formed in Kingston, Ontario in 1984, consisting of vocalist Gord Downie, guitarist Paul Langlois, guitarist Rob Baker (known as Bobby Baker until 1994), bassi ...