Pythagoras Of Samos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher,

Another belief attributed to Pythagoras was that of the " harmony of the spheres", which maintained that the planets and stars move according to mathematical equations, which correspond to musical notes and thus produce an inaudible symphony. According to Porphyry, Pythagoras taught that the seven

Another belief attributed to Pythagoras was that of the " harmony of the spheres", which maintained that the planets and stars move according to mathematical equations, which correspond to musical notes and thus produce an inaudible symphony. According to Porphyry, Pythagoras taught that the seven

Both

Both

Pythagorean teachings were known as "symbols" (''symbola'') and members took a vow of silence that they would not reveal these symbols to non-members. Those who did not obey the laws of the community were expelled and the remaining members would erect tombstones for them as though they had died. A number of "oral sayings" (''akoúsmata'') attributed to Pythagoras have survived, dealing with how members of the Pythagorean community should perform sacrifices, how they should honor the gods, how they should "move from here", and how they should be buried. Many of these sayings emphasize the importance of ritual purity and avoiding defilement. Other extant oral sayings forbid Pythagoreans from breaking bread, poking fires with swords, or picking up crumbs and teach that a person should always put the right sandal on before the left. The exact meanings of these sayings, however, are frequently obscure. Iamblichus preserves Aristotle's descriptions of the original, ritualistic intentions behind a few of these sayings, but these apparently later fell out of fashion, because Porphyry provides markedly different ethical-philosophical interpretations of them:

New initiates were allegedly not permitted to meet Pythagoras until after they had completed a five-year initiation period, during which they were required to remain silent. Sources indicate that Pythagoras himself was unusually progressive in his attitudes towards women and female members of Pythagoras's school appear to have played an active role in its operations. Iamblichus provides a list of 235 famous Pythagoreans, seventeen of whom are women. In later times, many prominent female philosophers contributed to the development of Neopythagoreanism.

Pythagoreanism also entailed a number of dietary prohibitions. It is more or less agreed that Pythagoras issued a prohibition against the consumption of fava beans and the meat of non-sacrificial animals such as fish and poultry. Both of these assumptions, however, have been contradicted. Pythagorean dietary restrictions may have been motivated by belief in the doctrine of metempsychosis; alternatively, they may be based on the genetic prevalence of favism, a type of enzyme deficiency anemia, in the Mediterranean. Some ancient writers present Pythagoras as enforcing a strictly

Pythagorean teachings were known as "symbols" (''symbola'') and members took a vow of silence that they would not reveal these symbols to non-members. Those who did not obey the laws of the community were expelled and the remaining members would erect tombstones for them as though they had died. A number of "oral sayings" (''akoúsmata'') attributed to Pythagoras have survived, dealing with how members of the Pythagorean community should perform sacrifices, how they should honor the gods, how they should "move from here", and how they should be buried. Many of these sayings emphasize the importance of ritual purity and avoiding defilement. Other extant oral sayings forbid Pythagoreans from breaking bread, poking fires with swords, or picking up crumbs and teach that a person should always put the right sandal on before the left. The exact meanings of these sayings, however, are frequently obscure. Iamblichus preserves Aristotle's descriptions of the original, ritualistic intentions behind a few of these sayings, but these apparently later fell out of fashion, because Porphyry provides markedly different ethical-philosophical interpretations of them:

New initiates were allegedly not permitted to meet Pythagoras until after they had completed a five-year initiation period, during which they were required to remain silent. Sources indicate that Pythagoras himself was unusually progressive in his attitudes towards women and female members of Pythagoras's school appear to have played an active role in its operations. Iamblichus provides a list of 235 famous Pythagoreans, seventeen of whom are women. In later times, many prominent female philosophers contributed to the development of Neopythagoreanism.

Pythagoreanism also entailed a number of dietary prohibitions. It is more or less agreed that Pythagoras issued a prohibition against the consumption of fava beans and the meat of non-sacrificial animals such as fish and poultry. Both of these assumptions, however, have been contradicted. Pythagorean dietary restrictions may have been motivated by belief in the doctrine of metempsychosis; alternatively, they may be based on the genetic prevalence of favism, a type of enzyme deficiency anemia, in the Mediterranean. Some ancient writers present Pythagoras as enforcing a strictly

Although Pythagoras is most famous today for his alleged mathematical discoveries, classical historians dispute whether he himself ever actually made any significant contributions to the field. Many mathematical and scientific discoveries were attributed to Pythagoras, including his famous theorem, as well as discoveries in the fields of

Although Pythagoras is most famous today for his alleged mathematical discoveries, classical historians dispute whether he himself ever actually made any significant contributions to the field. Many mathematical and scientific discoveries were attributed to Pythagoras, including his famous theorem, as well as discoveries in the fields of

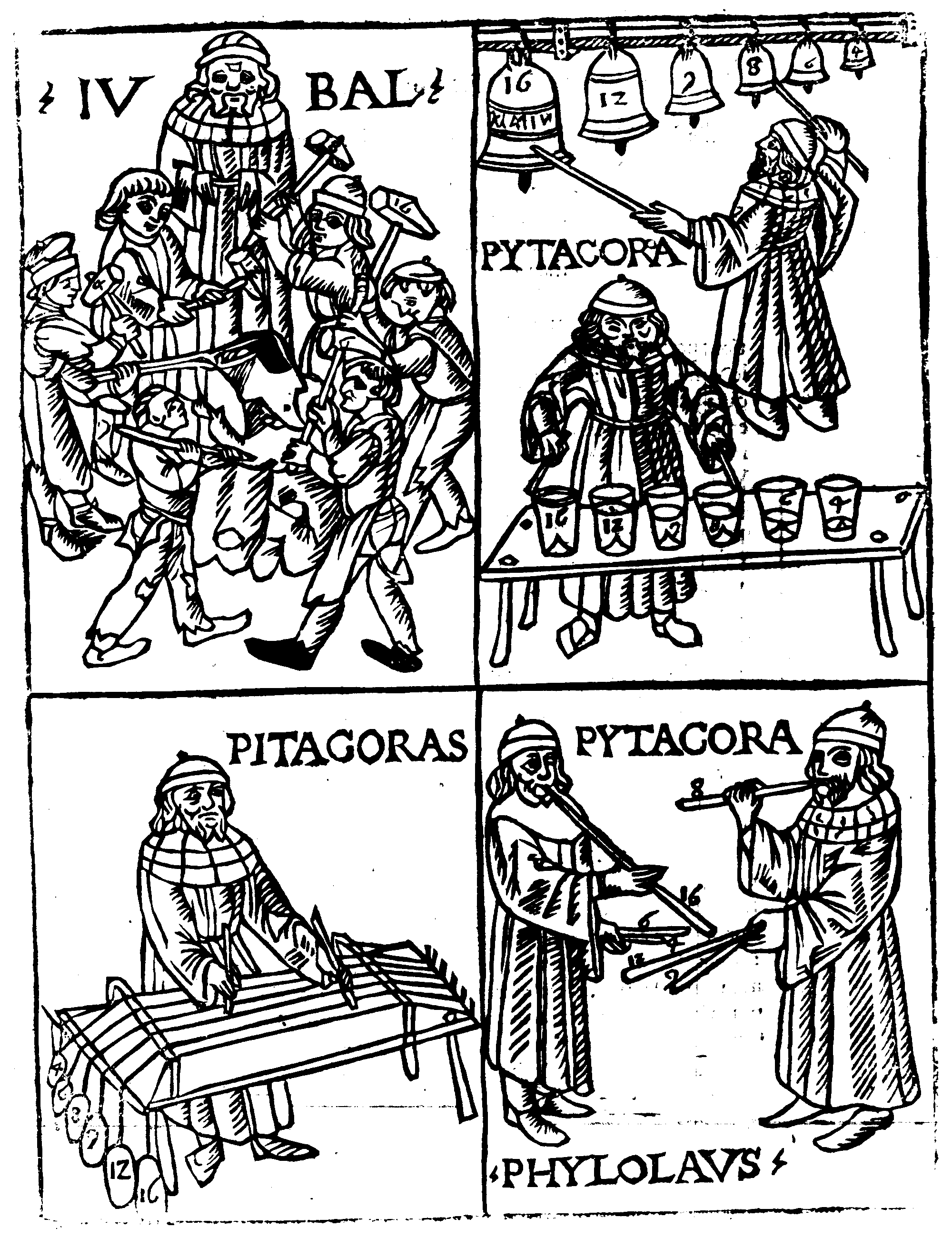

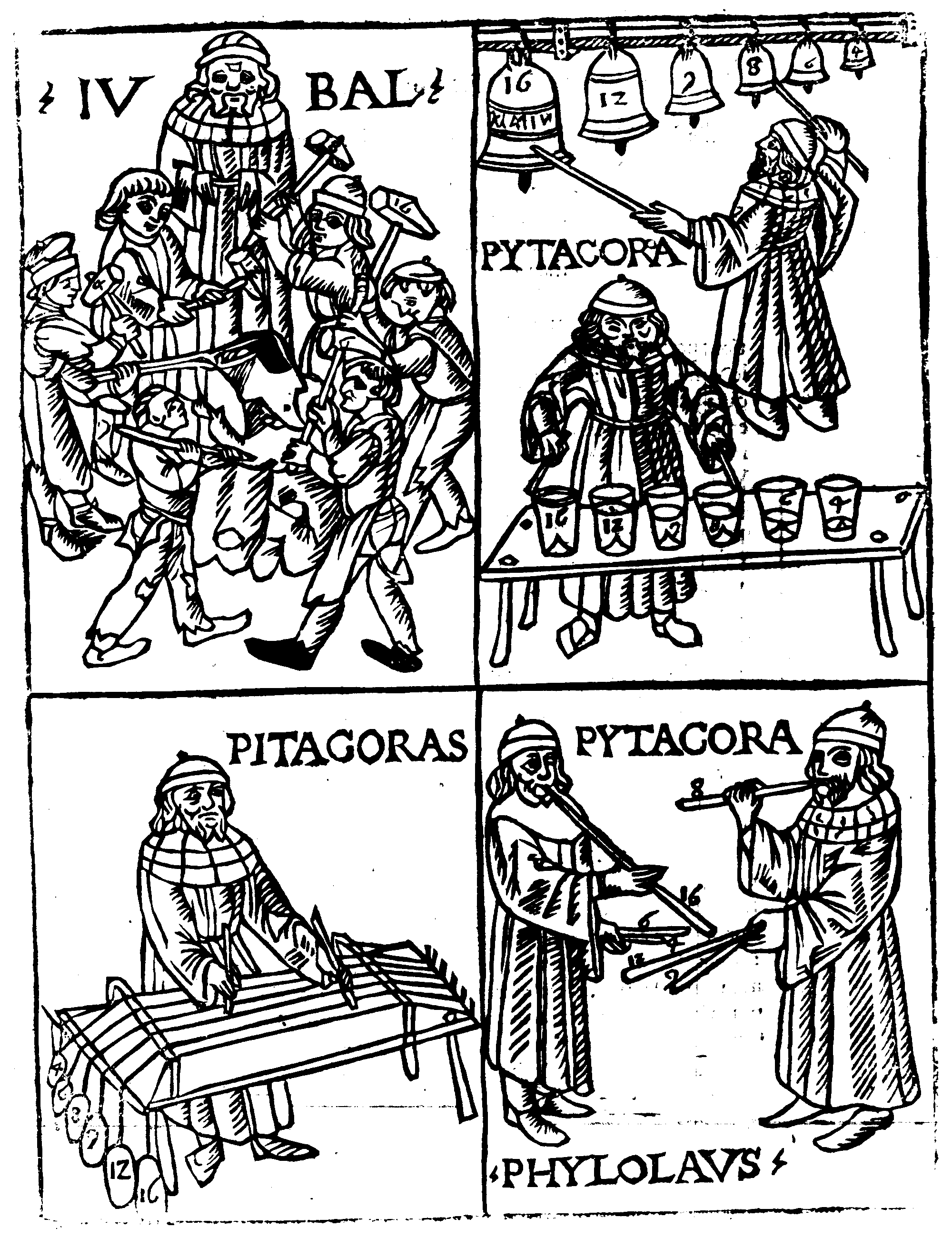

According to legend, Pythagoras discovered that musical notes could be translated into mathematical equations when he passed blacksmiths at work one day and heard the sound of their

According to legend, Pythagoras discovered that musical notes could be translated into mathematical equations when he passed blacksmiths at work one day and heard the sound of their

During the

During the

"Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, Fragments and Commentary"

Arthur Fairbanks Hanover Historical Texts Project, Hanover College Department of History

"Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans"

, Department of Mathematics,

"Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism"

''

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

and influenced the philosophies of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, and, through them, Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

. Modern scholars disagree regarding Pythagoras's education and influences, but most agree that he travelled to Croton in southern Italy around 530 BC, where he founded a school in which initiates were allegedly sworn to secrecy and lived a communal, ascetic lifestyle.

In antiquity, Pythagoras was credited with mathematical

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and scientific discoveries, such as the Pythagorean theorem, Pythagorean tuning, the five regular solids, the theory of proportions, the sphericity of the Earth, the identity of the morning

Morning is either the period from sunrise to noon, or the period from midnight to noon. In the first definition it is preceded by the twilight period of dawn, and there are no exact times for when morning begins (also true of evening and nigh ...

and evening stars as the planet Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

, and the division of the globe into five climatic zones. He was reputedly the first man to call himself a philosopher ("lover of wisdom"). Historians debate whether Pythagoras made these discoveries and pronouncements, as some of the accomplishments credited to him likely originated earlier or were made by his colleagues or successors, such as Hippasus and Philolaus.

The teaching most securely identified with Pythagoras is the "transmigration of souls" or '' metempsychosis'', which holds that every soul is immortal and, upon death, enters into a new body. He may have also devised the doctrine of '' musica universalis'', which holds that the planets

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets by the most restrictive definition of the te ...

move according to mathematical

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

ratios and thus resonate to produce an inaudible symphony of music. Following Croton's decisive victory over Sybaris in around 510 BC, Pythagoras's followers came into conflict with supporters of democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

, and their meeting houses were burned. Pythagoras may have been killed during this persecution, or he may have escaped to Metapontum and died there.

Pythagoras influenced Plato whose dialogues (especially '' Timaeus'') exhibit Pythagorean ideas. A major revival of his teachings occurred in the first century BC among Middle Platonists, coinciding with the rise of Neopythagoreanism. Pythagoras continued to be regarded as a great philosopher throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and Pythagoreanism had an influence on scientists such as Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

, and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

. Pythagorean symbolism was also used throughout early modern European esotericism, and his teachings as portrayed in Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

's '' Metamorphoses'' would later influence the modern vegetarian movement.

Life

No authentic writings of Pythagoras have survived, and almost nothing is known for certain about his life. The earliest sources on Pythagoras's life, from Xenophanes, Heraclitus, Empedocles, Ion of Chios, andHerodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

are brief, ambiguous, and often satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual arts, visual, literature, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently Nonfiction, non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ...

. The major sources on Pythagoras's life are three biographies from late antiquity written by Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

, Porphyry, and Iamblichus, all of which are filled primarily with myths and legends and which become longer and more fantastic in their descriptions of Pythagoras's achievements the more removed they are from Pythagoras's times. However, Porphyry and Iamblichus also used some material taken from earlier writings in the 4th century BC by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's students Dicaearchus, Aristoxenus, and Heraclides Ponticus, which, when it can be identified, is generally considered to be the most reliable.

Early life

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

and Isocrates

Isocrates (; ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and writte ...

agree that Pythagoras was the son of Mnesarchus, and that he was born on the Greek island of Samos in the eastern Aegean. Mnesarchus is said to have been a gem-engraver or a wealthy merchant but his ancestry is disputed and unclear. Apollonius of Tyana writes that Pythagoras's mother was Pythaïs, who was said to be a descendant of Ancaeus, the mythical founder of Samos. Iamblichus tells the story that the Pythia prophesied to her while she was pregnant with him that she would give birth to a man supremely beautiful, wise, and beneficial to humankind. As to the date of his birth, Aristoxenus stated that Pythagoras left Samos in the reign of Polycrates, at the age of 40, which would give a date of birth around 570 BC. Pythagoras's name led him to be associated with Pythia

Pythia (; ) was the title of the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She specifically served as its oracle and was known as the Oracle of Delphi. Her title was also historically glossed in English as th ...

n Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

(); Aristippus of Cyrene in the 4th century BC explained his name by saying, "He spoke the truth no less than did the Pythian .

During Pythagoras's formative years, Samos was a thriving cultural hub known for its feats of advanced architectural engineering, including the building of the Tunnel of Eupalinos, and for its riotous festival culture. It was a major center of trade in the Aegean where traders brought goods from the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

. According to Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier, these traders almost certainly brought with them Near Eastern ideas and traditions. Pythagoras's early life also coincided with the flowering of early Ionian natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

. He was a contemporary of the philosophers Anaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

, Anaximenes, and the historian Hecataeus, all of whom lived in Miletus

Miletus (Ancient Greek: Μίλητος, Mílētos) was an influential ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in present day Turkey. Renowned in antiquity for its wealth, maritime power, and ex ...

, across the sea from Samos.

Reputed travels

Modern scholarship has shown that the culture ofArchaic Greece

Archaic Greece was the period in History of Greece, Greek history lasting from to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical Greece, Classical period. In the archaic period, the ...

was heavily influenced by those of Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

ine and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

n cultures, which appears to have been recognized by authors later in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, who attributed many of Pythagoras' unusual and unconventional beliefs to invented travels to far off lands, where he learned from those people himself. The doctrine of metempsychosis, or reincarnation of the soul after death, which Herodotus had mistakenly attributed to the Egyptians, led to an elaborate tale where Pythagoras learned the Egyptian language

The Egyptian language, or Ancient Egyptian (; ), is an extinct branch of the Afro-Asiatic languages that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts, which were made accessible to the modern world ...

from the Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

Amasis II himself, and then traveled to study with the Egyptian priests at Diospolis (Thebes), where he was the only foreigner ever to be granted the privilege of taking part in their worship. Other ancient writers, however, claimed that Pythagoras had learned these teachings from the Magi

Magi (), or magus (), is the term for priests in Zoroastrianism and earlier Iranian religions. The earliest known use of the word ''magi'' is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius the Great, known as the Behistun Inscription. Old Per ...

in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

or even from Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

himself. The Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns are also reputed to have taught Pythagoras arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

and the Chaldeans to have taught him astronomy. By the third century BC, Pythagoras was already reported to have studied under the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

as well. By the third century AD, Pythagoras was also reported by Philostratus to have studied under sages or gymnosophists in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, and, according to Iamblichus, also with the Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

and Iberians.

Alleged Greek teachers

Ancient sources also record Pythagoras having studied under a variety of native Greek thinkers. Diogenes Laërtius asserts that Pythagoras later visitedCrete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, where he went to the Cave of Ida with Epimenides. Some identify Hermodamas of Samos as a possible tutor. Hermodamas represented the indigenous Samian rhapsodic tradition and his father Creophylos was said to have been the host of his rival poet Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

. Others credit Bias of Priene, Thales, or Anaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

(a pupil of Thales). Other traditions claim the mythic bard Orpheus as Pythagoras's teacher, thus representing the Orphic Mysteries. The Neoplatonists wrote of a "sacred discourse" Pythagoras had written on the gods in the Doric Greek

Doric or Dorian (), also known as West Greek, was a group of Ancient Greek dialects; its Variety (linguistics), varieties are divided into the Doric proper and Northwest Doric subgroups. Doric was spoken in a vast area, including northern Greec ...

dialect, which they believed had been dictated to Pythagoras by the Orphic priest Aglaophamus upon his initiation to the orphic Mysteries at Leibethra. Iamblichus credited Orpheus with having been the model for Pythagoras's manner of speech, his spiritual attitude, and his manner of worship. Iamblichus describes Pythagoreanism as a synthesis of everything Pythagoras had learned from Orpheus, from the Egyptian priests, from the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries () were initiations held every year for the Cult (religious practice), cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Eleusis in ancient Greece. They are considered the "most famous of the secret rel ...

, and from other religious and philosophical traditions. Contradicting all these reports, the novelist Antonius Diogenes, writing in the second century BC, reports that Pythagoras discovered all his doctrines himself by interpreting dreams. Riedweg states that, although these stories are fanciful, Pythagoras's teachings were definitely influenced by Orphism to a noteworthy extent.

Of the various Greek sages claimed to have taught Pythagoras, Pherecydes of Syros is mentioned most often. Similar miracle stories were told about both Pythagoras and Pherecydes, including one in which the hero predicts a shipwreck, one in which he predicts the conquest of Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

, and one in which he drinks from a well and predicts an earthquake. Apollonius Paradoxographus, a paradoxographer who may have lived in the second century BC, identified Pythagoras's thaumaturgic ideas as a result of Pherecydes's influence. Another story, which may be traced to the Neopythagorean philosopher Nicomachus, tells that, when Pherecydes was old and dying on the island of Delos, Pythagoras returned to care for him and pay his respects. Duris, the historian and tyrant of Samos, is reported to have patriotically boasted of an epitaph supposedly penned by Pherecydes which declared that Pythagoras's wisdom exceeded his own. On the grounds of all these references connecting Pythagoras with Pherecydes, Riedweg concludes that there may well be some historical foundation to the tradition that Pherecydes was Pythagoras's teacher. Pythagoras and Pherecydes also appear to have shared similar views on the soul and the teaching of metempsychosis.

In Croton

Porphyry repeats an account from Antiphon, who reported that, while he was still on Samos, Pythagoras founded a school known as the "semicircle". Here, Samians debated matters of public concern. Supposedly, the school became so renowned that the brightest minds in all of Greece came to Samos to hear Pythagoras teach. Pythagoras himself dwelled in a secret cave, where he studied in private and occasionally held discourses with a few of his close friends. Christoph Riedweg, a German scholar of early Pythagoreanism, states that it is entirely possible Pythagoras may have taught on Samos, but cautions that Antiphon's account, which makes reference to a specific building that was still in use during his own time, appears to be motivated by Samian patriotic interest. Around 530 BC, when Pythagoras was about forty years old, he left Samos. His later admirers claimed that he left because he disagreed with the tyranny of Polycrates in Samos; Riedweg notes that this explanation closely aligns with Nicomachus's emphasis on Pythagoras's purported love of freedom, but that Pythagoras's enemies portrayed him as having a proclivity towards tyranny. Other accounts claim that Pythagoras left Samos because he was so overburdened with public duties in Samos, because of the high estimation in which he was held by his fellow-citizens. He arrived in the Greek colony of Croton (today's Crotone, inCalabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

) in what was then Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

. All sources agree that Pythagoras was charismatic and quickly acquired great political influence in his new environment. He served as an advisor to the elites in Croton and gave them frequent advice. Later biographers tell fantastical stories of the effects of his eloquent speeches in leading the people of Croton to abandon their luxurious and corrupt way of life and devote themselves to the purer system which he came to introduce.

Family and friends

Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; ; ) is a large 10th-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine encyclopedia of the History of the Mediterranean region, ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas () or Souidas (). It is an ...

writes that Pythagoras had 4 children (Telauges, Mnesarchus, Myia and Arignote). The wrestler Milo of Croton

Milo or Milon of Croton () was a famous Ancient Greece, ancient Greek athlete from Crotone, Croton, which is today in the Magna Graecia region of southern Italy.

Milo was a six-time winner at the Ancient Olympic Games, Olympics, once for boys' w ...

was said to have been a close associate of Pythagoras and was credited with having saved the philosopher's life when a roof was about to collapse. This association may have been the result of confusion with a different man named Pythagoras, who was an athletics trainer.

Death

Pythagoras's emphasis on dedication and asceticism are credited with aiding in Croton's decisive victory over the neighboring colony of Sybaris in 510 BC. After the victory, some prominent citizens of Croton proposed a democratic constitution, which the Pythagoreans rejected. The supporters of democracy, headed by Cylon and Ninon, the former of whom is said to have been irritated by his exclusion from Pythagoras's brotherhood, roused the populace against them. Followers of Cylon and Ninon attacked the Pythagoreans during one of their meetings, either in the house of Milo or in some other meeting-place. Accounts of the attack are often contradictory and many probably confused it with the later anti-Pythagorean rebellions, such as the one in Metapontum in 454 BC. The building was apparently set on fire, and many of the assembled members perished; only the younger and more active members managed to escape. Sources disagree regarding whether Pythagoras was present when the attack occurred and, if he was, whether or not he managed to escape. In some accounts, Pythagoras was not at the meeting when the Pythagoreans were attacked because he was on Delos tending to the dying Pherecydes. According to another account from Dicaearchus, Pythagoras was at the meeting and managed to escape, leading a small group of followers to the nearby city of Locris, where they pleaded for sanctuary, but were denied. They reached the city of Metapontum, where they took shelter in the temple of theMuses

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, the Muses (, ) were the Artistic inspiration, inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the poetry, lyric p ...

and died there of starvation after forty days without food. Another tale recorded by Porphyry claims that, as Pythagoras's enemies were burning the house, his devoted students laid down on the ground to make a path for him to escape by walking over their bodies across the flames like a bridge. Pythagoras managed to escape, but was so despondent at the deaths of his beloved students that he committed suicide. A different legend reported by both Diogenes Laërtius and Iamblichus states that Pythagoras almost managed to escape, but that he came to a fava bean field and refused to run through it, since doing so would violate his teachings, so he stopped instead and was killed. This story seems to have originated from the writer Neanthes, who told it about later Pythagoreans, not about Pythagoras himself.

Teachings

Metempsychosis

Although the exact details of Pythagoras's teachings are uncertain, it is possible to reconstruct a general outline of his main ideas. Aristotle writes at length about the teachings of the Pythagoreans, but without mentioning Pythagoras directly. One of Pythagoras's main doctrines appears to have been '' metempsychosis'', the belief that all souls are immortal and that, after death, a soul is transferred into a new body. This teaching is referenced by Xenophanes, Ion of Chios, and Herodotus. The earliest source on Pythagoras's metempsychosis is a satirical poem probably written after his death by the Greek philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon ( BC), who had been one of his contemporaries, in which Xenophanes describes Pythagoras interceding on behalf of a dog that is being beaten, professing to recognize in its cries the voice of a departed friend. Nothing whatsoever, however, is known about the nature or mechanism by which Pythagoras believed metempsychosis to occur. Empedocles alludes in one of his poems that Pythagoras may have claimed to possess the ability to recall his former incarnations. Diogenes Laërtius reports an account from Heraclides Ponticus that Pythagoras told people that he had lived four previous lives that he could remember in detail. The first of these lives was as Aethalides the son of Hermes, who granted him the ability to remember all his past incarnations. Next, he was incarnated as Euphorbus, a minor hero from theTrojan War

The Trojan War was a legendary conflict in Greek mythology that took place around the twelfth or thirteenth century BC. The war was waged by the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans (Ancient Greece, Greeks) against the city of Troy after Paris (mytho ...

briefly mentioned in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

''. He then became the philosopher Hermotimus, who recognized the shield of Euphorbus in the temple of Apollo. His final incarnation was as Pyrrhus, a fisherman from Delos. One of his past lives, as reported by Dicaearchus, was as a beautiful courtesan.

Numerology

Muse

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, the Muses (, ) were the Artistic inspiration, inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the poetry, lyric p ...

s were actually the seven planets singing together.

Modern scholars typically ascribe these discoveries to the later Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus of Croton ( BC), whose extant fragments are the earliest texts to describe the numerological and musical theories that were later ascribed to Pythagoras. In his landmark study ''Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism'', Walter Burkert argues that Pythagoras was a charismatic political and religious teacher, but that the number philosophy attributed to him was really an innovation by Philolaus. According to Burkert, Pythagoras never dealt with numbers at all, let alone made any noteworthy contribution to mathematics. Burkert argues that the only mathematics the Pythagoreans ever actually engaged in was simple, proofless arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

, but that these arithmetic discoveries did contribute significantly to the beginnings of mathematics. For the later Pythagoreans, Pythagoras was credited with devising the tetractys, the triangular figure of four rows which add up to the "perfect" number, ten. The Pythagoreans regarded the tetractys as a symbol of utmost mystical importance. Iamblichus, in his ''Life of Pythagoras'', states that the tetractys was "so admirable, and so divinised by those who understood t" that Pythagoras's students would swear oaths by it.

This shouldn't be confused with a simplified version known today as " Pythagorean numerology", involving a variant of an isopsephic technique known – among other names – as or , by means of which the base values of letters in a word were mathematically reduced by addition or division, in order to obtain a single value from one to nine for the whole name or word.

Pythagoreanism

Communal lifestyle

Both

Both Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and Isocrates

Isocrates (; ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and writte ...

state that, above all else, Pythagoras was known as the founder of a new way of life. The organization Pythagoras founded at Croton was called a "school", but, in many ways, resembled a monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

. The adherents were bound by a vow

A vow ( Lat. ''votum'', vow, promise; see vote) is a promise or oath. A vow is used as a promise that is solemn rather than casual.

Marriage vows

Marriage vows are binding promises each partner in a couple makes to the other during a weddin ...

to Pythagoras and each other, for the purpose of pursuing the religious

Religion is a range of social- cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural ...

and ascetic observances, and of studying his religious and philosophical theories. The members of the sect shared all their possessions in common and were devoted to each other to the exclusion of outsiders. Ancient sources record that the Pythagoreans ate meals in common after the manner of the Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

ns. One Pythagorean maxim

Maxim or Maksim may refer to:

Entertainment

*Maxim (magazine), ''Maxim'' (magazine), an international men's magazine

** Maxim (Australia), ''Maxim'' (Australia), the Australian edition

** Maxim (India), ''Maxim'' (India), the Indian edition

*Maxim ...

was "''koinà tà phílōn''" ("All things in common among friends"). Both Iamblichus and Porphyry provide detailed accounts of the organization of the school, although the primary interest of both writers is not historical accuracy, but rather to present Pythagoras as a divine figure, sent by the gods

A deity or god is a supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to having authority over some aspect of the universe and/or life. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines ''deity'' as a God (male deity), god or god ...

to benefit mankind. Iamblichus, in particular, presents the "Pythagorean Way of Life" as a pagan alternative to the Christian monastic communities of his own time. For Pythagoreans, the highest reward humans could attain was for their soul to join in the life of the gods and thus escape the cycle of reincarnation. Two groups existed within early Pythagoreanism: the ''mathematikoi'' ("learners") and the ''akousmatikoi'' ("listeners"). The ''akousmatikoi'' are traditionally identified by scholars as "old believers" in mysticism, numerology, and religious teachings; whereas the ''mathematikoi'' are traditionally identified as a more intellectual, modernist faction who were more rationalist and scientific. Gregory cautions that there was probably not a sharp distinction between them and that many Pythagoreans probably believed the two approaches were compatible. The study of mathematics and music may have been connected to the worship of Apollo. The Pythagoreans believed that music was a purification for the soul, just as medicine was a purification for the body. One anecdote of Pythagoras reports that when he encountered some drunken youths trying to break into the home of a virtuous woman, he sang a solemn tune with long spondees and the boys' "raging willfulness" was quelled. The Pythagoreans also placed particular emphasis on the importance of physical exercise

Exercise or workout is physical activity that enhances or maintains fitness and overall health. It is performed for various reasons, including weight loss or maintenance, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardio ...

; therapeutic dancing, daily morning walks along scenic routes, and athletics were major components of the Pythagorean lifestyle. Moments of contemplation at the beginning and end of each day were also advised.

Prohibitions and regulations

Pythagorean teachings were known as "symbols" (''symbola'') and members took a vow of silence that they would not reveal these symbols to non-members. Those who did not obey the laws of the community were expelled and the remaining members would erect tombstones for them as though they had died. A number of "oral sayings" (''akoúsmata'') attributed to Pythagoras have survived, dealing with how members of the Pythagorean community should perform sacrifices, how they should honor the gods, how they should "move from here", and how they should be buried. Many of these sayings emphasize the importance of ritual purity and avoiding defilement. Other extant oral sayings forbid Pythagoreans from breaking bread, poking fires with swords, or picking up crumbs and teach that a person should always put the right sandal on before the left. The exact meanings of these sayings, however, are frequently obscure. Iamblichus preserves Aristotle's descriptions of the original, ritualistic intentions behind a few of these sayings, but these apparently later fell out of fashion, because Porphyry provides markedly different ethical-philosophical interpretations of them:

New initiates were allegedly not permitted to meet Pythagoras until after they had completed a five-year initiation period, during which they were required to remain silent. Sources indicate that Pythagoras himself was unusually progressive in his attitudes towards women and female members of Pythagoras's school appear to have played an active role in its operations. Iamblichus provides a list of 235 famous Pythagoreans, seventeen of whom are women. In later times, many prominent female philosophers contributed to the development of Neopythagoreanism.

Pythagoreanism also entailed a number of dietary prohibitions. It is more or less agreed that Pythagoras issued a prohibition against the consumption of fava beans and the meat of non-sacrificial animals such as fish and poultry. Both of these assumptions, however, have been contradicted. Pythagorean dietary restrictions may have been motivated by belief in the doctrine of metempsychosis; alternatively, they may be based on the genetic prevalence of favism, a type of enzyme deficiency anemia, in the Mediterranean. Some ancient writers present Pythagoras as enforcing a strictly

Pythagorean teachings were known as "symbols" (''symbola'') and members took a vow of silence that they would not reveal these symbols to non-members. Those who did not obey the laws of the community were expelled and the remaining members would erect tombstones for them as though they had died. A number of "oral sayings" (''akoúsmata'') attributed to Pythagoras have survived, dealing with how members of the Pythagorean community should perform sacrifices, how they should honor the gods, how they should "move from here", and how they should be buried. Many of these sayings emphasize the importance of ritual purity and avoiding defilement. Other extant oral sayings forbid Pythagoreans from breaking bread, poking fires with swords, or picking up crumbs and teach that a person should always put the right sandal on before the left. The exact meanings of these sayings, however, are frequently obscure. Iamblichus preserves Aristotle's descriptions of the original, ritualistic intentions behind a few of these sayings, but these apparently later fell out of fashion, because Porphyry provides markedly different ethical-philosophical interpretations of them:

New initiates were allegedly not permitted to meet Pythagoras until after they had completed a five-year initiation period, during which they were required to remain silent. Sources indicate that Pythagoras himself was unusually progressive in his attitudes towards women and female members of Pythagoras's school appear to have played an active role in its operations. Iamblichus provides a list of 235 famous Pythagoreans, seventeen of whom are women. In later times, many prominent female philosophers contributed to the development of Neopythagoreanism.

Pythagoreanism also entailed a number of dietary prohibitions. It is more or less agreed that Pythagoras issued a prohibition against the consumption of fava beans and the meat of non-sacrificial animals such as fish and poultry. Both of these assumptions, however, have been contradicted. Pythagorean dietary restrictions may have been motivated by belief in the doctrine of metempsychosis; alternatively, they may be based on the genetic prevalence of favism, a type of enzyme deficiency anemia, in the Mediterranean. Some ancient writers present Pythagoras as enforcing a strictly vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the Eating, consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects as food, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slau ...

diet. Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus (; , ''Eúdoxos ho Knídios''; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek Ancient Greek astronomy, astronomer, Greek mathematics, mathematician, doctor, and lawmaker. He was a student of Archytas and Plato. All of his original work ...

, a student of Archytas, writes, "Pythagoras was distinguished by such purity and so avoided killing and killers that he not only abstained from animal foods, but even kept his distance from cooks and hunters." Other authorities contradict this statement. According to Aristoxenus, Pythagoras allowed the use of all kinds of animal food except the flesh of oxen used for plough

A plough or ( US) plow (both pronounced ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses but modern ploughs are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden ...

ing, and rams. According to Heraclides Ponticus, Pythagoras ate the meat from sacrifices and established a diet for athletes dependent on meat.

Legends

Within his own lifetime, Pythagoras was already the subject of elaboratehagiographic

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an wiktionary:adulatory, adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religi ...

legends. Aristotle described Pythagoras as a wonder-worker and somewhat of a supernatural figure. In a fragment, Aristotle writes that Pythagoras had a golden thigh, which he publicly exhibited at the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

and showed to Abaris the Hyperborean as proof of his identity as the "Hyperborean Apollo". Supposedly, the priest of Apollo gave Pythagoras a magic arrow, which he used to fly over long distances and perform ritual purifications. He was supposedly once seen at both Metapontum and Croton at the same time. When Pythagoras crossed the river Kosas (the modern-day Basento), "several witnesses" reported that they heard it greet him by name. In Roman times, a legend claimed that Pythagoras was the son of Apollo.

Pythagoras was said to have dressed all in white. He is also said to have borne a golden wreath atop his head and to have worn trousers after the fashion of the Thracians

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared betwee ...

. Pythagoras was said to have had extraordinary success in dealing with animals. A fragment from Aristotle records that, when a deadly snake bit Pythagoras, he bit it back and killed it. Both Porphyry and Iamblichus report that Pythagoras once persuaded a bull not to eat fava beans and that he once convinced a notoriously destructive bear to swear that it would never harm a living thing again, and that the bear kept its word. Riedweg suggests that Pythagoras may have personally encouraged these legends, but Gregory states that there is no direct evidence of this.

Attributed discoveries

In mathematics

music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, and medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

. Since at least the first century BC, Pythagoras has commonly been given credit for discovering the Pythagorean theorem, a theorem in geometry that states that "in a right-angled triangle the square of the hypotenuse is equal o the sum ofthe squares of the two other sides"—that is, . According to a popular legend, after he discovered this theorem, Pythagoras sacrificed an ox, or possibly even a whole '' hecatomb'', to the gods. Cicero rejected this story as spurious because of the much more widely held belief that Pythagoras forbade blood sacrifices. Porphyry attempted to explain the story by asserting that the ox was actually made of dough

Dough is a malleable, sometimes elastic paste made from flour (which itself is made from grains or from leguminous or chestnut crops). Dough is typically made by mixing flour with a small amount of water or other liquid and sometimes includes ...

.

The Pythagorean theorem was known and used by the Babylonians and Indians centuries before Pythagoras, and Burkert rejects the suggestion that Pythagoras had anything to do with it, noting that Pythagoras was never credited with having proved any theorem in antiquity. Furthermore, the manner in which the Babylonians employed Pythagorean numbers implies that they knew that the principle was generally applicable, and knew some kind of proof, which has not yet been found in the (still largely unpublished) cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

sources.

In music

According to legend, Pythagoras discovered that musical notes could be translated into mathematical equations when he passed blacksmiths at work one day and heard the sound of their

According to legend, Pythagoras discovered that musical notes could be translated into mathematical equations when he passed blacksmiths at work one day and heard the sound of their hammers

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nail (fastener), nails into wood, to sh ...

clanging against the anvils. Thinking that the sounds of the hammers were beautiful and harmonious, except for one, he rushed into the blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

shop and began testing the hammers. He then realized that the tune played when the hammer struck was directly proportional to the size of the hammer and therefore concluded that music was mathematical.

In astronomy

In ancient times, Pythagoras and his contemporary Parmenides of Elea were both credited with having been the first to teach that the Earth was spherical, the first to divide the globe into five climatic zones, and the first to identify the morning star and the evening star as the same celestial object (now known asVenus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

). Of the two philosophers, Parmenides has a much stronger claim to having been the first and the attribution of these discoveries to Pythagoras seems to have possibly originated from a pseudepigrapha

A pseudepigraph (also :wikt:anglicized, anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a false attribution, falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. Th ...

l poem. Empedocles, who lived in Magna Graecia shortly after Pythagoras and Parmenides, knew that the earth was spherical. By the end of the fifth century BC, this fact was universally accepted among Greek intellectuals.

Later influence in antiquity

On Greek philosophy

Sizeable Pythagorean communities existed in Magna Graecia,Phlius

Phlius (; ) or Phleius () was an independent polis (city-state) in the northeastern part of Peloponnesus. Phlius' territory, called Phliasia (), was bounded on the north by Sicyonia, on the west by Arcadia, on the east by Cleonae, and on the ...

, and Thebes during the early fourth century BC. Around the same time, the Pythagorean philosopher Archytas was highly influential on the politics of the city of Tarentum in Magna Graecia. According to later tradition, Archytas was elected as ''strategos

''Strategos'' (), also known by its Linguistic Latinisation, Latinized form ''strategus'', is a Greek language, Greek term to mean 'military General officer, general'. In the Hellenistic world and in the Byzantine Empire, the term was also use ...

'' ("general") seven times, even though others were prohibited from serving more than a year. Archytas was also a renowned mathematician and musician. He was a close friend of Plato and he is quoted in Plato's ''Republic''. Aristotle states that the philosophy of Plato was heavily dependent on the teachings of the Pythagoreans. Cicero repeats this statement, remarking that ''Platonem ferunt didicisse Pythagorea omnia'' ("They say Plato learned all things Pythagorean").Tusc. Disput. 1.17.39. According to Charles H. Kahn, Plato's middle dialogues, including '' Meno'', '' Phaedo'', and '' The Republic'', have a strong "Pythagorean coloring", and his last few dialogues (particularly '' Philebus'' and '' Timaeus'') are extremely Pythagorean in character.

The poet Heraclitus of Ephesus ( BC), who was born a few miles across the sea from Samos and may have lived within Pythagoras's lifetime, mocked Pythagoras as a clever charlatan, remarking that "Pythagoras, son of Mnesarchus, practiced inquiry more than any other man, and selecting from these writings he manufactured a wisdom for himself—much learning, artful knavery." Alcmaeon of Croton ( BC), a doctor who lived in Croton at around the same time Pythagoras lived there, incorporates many Pythagorean teachings into his writings and alludes to having possibly known Pythagoras personally. The Greek poets Ion of Chios ( BC) and Empedocles of Acragas ( BC) both express admiration for Pythagoras in their poems.

According to R. M. Hare, Plato's ''Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

'' may be partially based on the "tightly organised community of like-minded thinkers" established by Pythagoras at Croton. Additionally, Plato may have borrowed from Pythagoras the idea that mathematics and abstract thought are a secure basis for philosophy, science, and morality. Plato and Pythagoras shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world" and both were probably influenced by Orphism. The historian of philosophy Frederick Copleston states that Plato probably borrowed his tripartite theory of the soul from the Pythagoreans.

A revival of Pythagorean teachings occurred in the first century BC when Middle Platonist philosophers such as Eudorus and Philo of Alexandria hailed the rise of a "new" Pythagoreanism in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

. At around the same time, Neopythagoreanism became prominent. The first-century AD philosopher Apollonius of Tyana sought to emulate Pythagoras and live by Pythagorean teachings. The later first-century Neopythagorean philosopher Moderatus of Gades expanded on Pythagorean number philosophy and probably understood the soul as a "kind of mathematical harmony". The Neopythagorean mathematician and musicologist Nicomachus likewise expanded on Pythagorean numerology and music theory. Numenius of Apamea interpreted Plato's teachings in light of Pythagorean doctrines.

On art and architecture

The oldest known building designed according to Pythagorean teachings is the Porta Maggiore Basilica, a subterranean basilica which was built during the reign of the Roman emperorNero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

as a secret place of worship for Pythagoreans. The basilica was built underground because of the Pythagorean emphasis on secrecy and also because of the legend that Pythagoras had sequestered himself in a cave on Samos. The basilica's apse is in the east and its atrium in the west out of respect for the rising sun. It has a narrow entrance leading to a small pool where the initiates could purify themselves. The building is also designed according to Pythagorean numerology, with each table in the sanctuary providing seats for seven people. Three aisles lead to a single altar, symbolizing the three parts of the soul approaching the unity of Apollo. The apse depicts a scene of the poet Sappho leaping off the Leucadian cliffs, clutching her lyre to her breast, while Apollo stands beneath her, extending his right hand in a gesture of protection, symbolizing Pythagorean teachings about the immortality of the soul. The interior of the sanctuary is almost entirely white because the color white was regarded by Pythagoreans as sacred.

The emperor Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

's Pantheon in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

was also built based on Pythagorean numerology. The temple's circular plan, central axis, hemispherical dome, and alignment with the four cardinal directions symbolize Pythagorean views on the order of the universe. The single oculus at the top of the dome symbolizes the monad and the sun-god Apollo. The twenty-eight ribs extending from the oculus symbolize the moon, because twenty-eight was the same number of months on the Pythagorean lunar calendar. The five coffered rings beneath the ribs represent the marriage of the sun and moon.

In early Christianity

Many early Christians had a deep respect for Pythagoras. Eusebius ( AD), bishop of Caesarea, praises Pythagoras in his ''Against Hierokles'' for his rule of silence, his frugality, his "extraordinary" morality, and his wise teachings. In another work, Eusebius compares Pythagoras toMoses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

. In one of his letters, the Church Father Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

( AD) praises Pythagoras for his wisdom and, in another letter, he credits Pythagoras for his belief in the immortality of the soul, which he suggests Christians inherited from him. Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

(354–430 AD) rejected Pythagoras's teaching of metempsychosis without explicitly naming him, but otherwise expressed admiration for him. In '' On the Trinity'', Augustine lauds the fact that Pythagoras was humble enough to call himself a ''philosophos'' or "lover of wisdom" rather than a "sage". In another passage, Augustine defends Pythagoras's reputation, arguing that Pythagoras certainly never taught the doctrine of metempsychosis.

Influence after antiquity

In the Middle Ages

During the

During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, Pythagoras was revered as the founder of mathematics and music, two of the Seven Liberal Arts. He appears in numerous medieval depictions, in illuminated manuscripts and in the relief sculptures on the portal of the Cathedral of Chartres. The ''Timaeus'' was the only dialogue of Plato to survive in Latin translation in western Europe, which led William of Conches (c. 1080–1160) to declare that Plato was Pythagorean. A large-scale translation movement emerged during the Abbasid Caliphate, translating many Greek texts into Arabic. Works ascribed to Pythagoras included the "Golden Verses" and snippets of his scientific and mathematical theories. By translating and disseminating Pythagorean texts, Islamic scholars ensured their survival and wider accessibility. This preserved knowledge that might have otherwise been lost through the decline of the Roman Empire and the neglect of classical learning in Europe. In the 1430s, the Camaldolese friar Ambrose Traversari translated Diogenes Laërtius's ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' from Greek into Latin and, in the 1460s, the philosopher Marsilio Ficino translated Porphyry and Iamblichus's ''Lives of Pythagoras'' into Latin as well, thereby allowing them to be read and studied by western scholars. In 1494, the Greek Neopythagorean scholar Constantine Lascaris published '' The Golden Verses of Pythagoras'', translated into Latin, with a printed edition of his ''Grammatica'', thereby bringing them to a widespread audience. In 1499, he published the first Renaissance biography of Pythagoras in his work ''Vitae illustrium philosophorum siculorum et calabrorum'', issued in Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

.

On modern science

In his preface to his book '' On the Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres'' (1543),Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

cites various Pythagoreans as the most important influences on the development of his heliocentric model of the universe, deliberately omitting mention of Aristarchus of Samos, a non-Pythagorean astronomer who had developed a fully heliocentric model in the fourth century BC, in effort to portray his model as fundamentally Pythagorean. Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

considered himself to be a Pythagorean. He believed in the Pythagorean doctrine of ''musica universalis'' and it was his search for the mathematical equations behind this doctrine that led to his discovery of the laws of planetary motion. Kepler titled his book on the subject '' Harmonices Mundi'' (''Harmonics of the World''), after the Pythagorean teaching that had inspired him. He also called Pythagoras the "grandfather" of all Copernicans.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

believed that a scientist may also be "a Platonist or a Pythagorean insofar as he considers the viewpoint of logical simplicity as an indispensable and effective tool of his research." The English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, inclu ...

argued that "In a sense, Plato and Pythagoras stand nearer to modern physical science than does Aristotle. The two former were mathematicians, whereas Aristotle was the son of a doctor". By this measure, Whitehead declared that Einstein and other modern scientists like him are "following the pure Pythagorean tradition."

On vegetarianism

A fictionalized portrayal of Pythagoras appears in Book XV ofOvid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

's '' Metamorphoses'', in which he delivers a speech imploring his followers to adhere to a strictly vegetarian diet. It was through Arthur Golding's 1567 English translation of Ovid's ''Metamorphoses'' that Pythagoras was best known to English-speakers throughout the early modern period. John Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

's ''Progress of the Soul'' discusses the implications of the doctrines expounded in the speech, and Michel de Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne ( ; ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), commonly known as Michel de Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularising the the essay ...

quoted the speech no less than three times in his treatise "Of Cruelty" to voice his moral objections against the mistreatment of animals. John Dryden

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration (En ...

included a translation of the scene with Pythagoras in his 1700 work '' Fables, Ancient and Modern'', and John Gay's 1726 fable "Pythagoras and the Countryman" reiterates its major themes, linking carnivorism with tyranny. Lord Chesterfield records that his conversion to vegetarianism had been motivated by reading Pythagoras's speech in Ovid's ''Metamorphoses''. Until the word ''vegetarianism'' was coined in the 1840s, vegetarians were referred to in English as "Pythagoreans".

On Western esotericism

Early modern European esotericism drew heavily on the teachings of Pythagoras. The Germanhumanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

scholar Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522) synthesized Pythagoreanism with Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

and Jewish Kabbalah

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

, arguing that Kabbalah and Pythagoreanism were both inspired by Mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

tradition and that Pythagoras was therefore a kabbalist. In his dialogue ''De verbo mirifico'' (1494), Reuchlin compared the Pythagorean tetractys to the ineffable divine name YHWH, ascribing each of the four letters of the tetragrammaton a symbolic meaning according to Pythagorean mystical teachings.

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa's popular and influential three-volume treatise '' De Occulta Philosophia'' cites Pythagoras as a "religious magi" and advances the idea that Pythagoras's mystical numerology operates on a supercelestial level, a religious term used to describe a high heavenly realm used during his time. The freemasons deliberately modeled their society on the community founded by Pythagoras at Croton. Rosicrucianism used Pythagorean symbolism, as did Robert Fludd (1574–1637), who believed his own musical writings to have been inspired by Pythagoras. John Dee was heavily influenced by Pythagorean ideology, particularly the teaching that all things are made of numbers.

On literature

The Transcendentalists read the ancient ''Lives of Pythagoras'' as guides on how to live a model life. Henry David Thoreau was impacted by Thomas Taylor's translations of Iamblichus's ''Life of Pythagoras'' and Stobaeus's ''Pythagoric Sayings'' and his views on nature may have been influenced by the Pythagorean idea of images corresponding to archetypes. The Pythagorean teaching of ''musica universalis'' is a recurring theme throughout Thoreau's '' magnum opus'', ''Walden

''Walden'' (; first published as ''Walden; or, Life in the Woods'') is an 1854 book by American transcendentalism, transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon the author's simple living in natural surroundings. T ...

''.

See also

* List of things named after Pythagoras * '' Ex pede Herculem'', "from his foot, e can measureHercules" – a maxim based on the apocryphal story that Pythagoras estimated Hercules's stature based on the length of a racecourse at Pisae * Pythagorean cup – a prank cup with a hidden siphon built in, attributed to Pythagoras * Pythagorean means – the arithmetic mean, the geometric mean, and the harmonic mean, claimed to have been studied by PythagorasNotes

Citations

References

Classical sources

* . he original Greek fragments of Xenophanes are provided, which are primarily preserved through the work of Diogenes (). For English translation see .* . n English translation of .* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . hich claims Zoroaster taught Pythagoras, also found in .* * * * * *Modern secondary sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * Scharinger, Stephan (2017). ''Die Wunder des Pythagoras: Überlieferungen im Vergleich'' he miracles of Pythagoras: A comparison of traditions Philippika, vol. 107. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. . *External links

* *"Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, Fragments and Commentary"

Arthur Fairbanks Hanover Historical Texts Project, Hanover College Department of History

"Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans"

, Department of Mathematics,

Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, TA&M, or TAMU) is a public university, public, Land-grant university, land-grant, research university in College Station, Texas, United States. It was founded in 1876 and became the flagship institution of ...

"Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism"

''

The Catholic Encyclopedia

''The'' ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'', also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedi ...

''

*

*

{{Authority control

570s BC births

490s BC deaths

6th-century BC mathematicians

6th-century BC Greek philosophers

5th-century BC Greek mathematicians

5th-century BC Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek geometers

Ancient Greek metaphysicians

Ancient Greek music theorists

Ancient Greek philosophers of mind

Ancient Greek political refugees

Ancient Greek shamans

Ancient occultists

Ancient Samians

Pythagoreans

Founders of religions

Numerologists

Pythagoreans of Magna Graecia

6th-century BC religious leaders

5th-century BC religious leaders