The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) was a period in the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

characterized by multiple social and political

reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

efforts. Reformers during this era, known as

Progressives, sought to address issues they associated with rapid

industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

,

urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from Rural area, rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. ...

,

immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

, and

political corruption

Political corruption is the use of powers by government officials or their network contacts for illegitimate private gain. Forms of corruption vary but can include bribery, lobbying, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, influen ...

, as well as the concentration of industrial ownership in

monopolies. Reformers expressed concern about slums,

poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

, and labor conditions. Multiple overlapping movements pursued social, political, and economic reforms by advocating changes in governance,

scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

s, and professionalism; regulating business;

protecting the

natural environment

The natural environment or natural world encompasses all life, biotic and abiotic component, abiotic things occurring nature, naturally, meaning in this case not artificiality, artificial. The term is most often applied to Earth or some parts ...

; and seeking to improve urban living and working conditions.

Corrupt and undemocratic

political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

s and their bosses were a major target of progressive reformers. To revitalize democracy, progressives established direct

primary elections,

direct election of senators (rather than by state legislatures),

initiatives and referendums,

and

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

which was promoted to advance democracy and bring the presumed moral influence of women into politics. For many progressives,

prohibition of alcoholic beverages was key to eliminating corruption in politics as well as improving social conditions.

Another target were

monopolies, which progressives worked to regulate through

trustbusting and

antitrust laws with the goal of promoting fair competition. Progressives also advocated new government agencies focused on regulation of industry. An additional goal of progressives was bringing to bear scientific, medical, and engineering solutions to reform government and education and foster improvements in various fields including medicine, finance, insurance, industry, railroads, and churches. They aimed to professionalize the social sciences, especially history,

economics,

and political science

and improve efficiency with

scientific management or Taylorism.

Initially, the movement operated chiefly at the local level, but later it expanded to the state and national levels. Progressive leaders were often from the educated middle class, and various progressive reform efforts drew support from lawyers, teachers, physicians, ministers, business people, and the working class.

Originators of progressive ideals and efforts

Certain key groups of thinkers, writers, and activists played key roles in creating or building the movements and ideas that came to define the shape of the Progressive Era.

Popular democracy: Initiative and referendum

Inspiration for the initiative movement was based on the Swiss experience. New Jersey labor activist James W. Sullivan visited Switzerland in 1888 and wrote a detailed book that became a template for reformers pushing the idea: ''Direct Legislation by the Citizenship Through the Initiative and Referendum'' (1893). He suggested that using the initiative would give political power to the working class and reduce the need for strikes. Sullivan's book was first widely read on the left, as by labor activists, socialists and populists. William U'Ren was an early convert who used it to build the Oregon reform crusade. By 1900, middle-class "progressive" reformers everywhere were studying it.

Muckraking: exposing corruption

Magazines experienced a boost in popularity in 1900, with some attaining circulations in the hundreds of thousands of subscribers. In the beginning of the age of mass media, the rapid expansion of national advertising led the cover price of popular magazines to fall sharply to about 10 cents, lessening the financial barrier to consume them. Another factor contributing to the dramatic upswing in magazine circulation was the prominent coverage of corruption in politics, local government, and big business, particularly by journalists and writers who became known as

muckraker

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

s''.'' They wrote for popular magazines to expose social and political sins and shortcomings. Relying on their own

investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, racial injustice, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend m ...

, muckrakers often worked to expose social ills and corporate and

political corruption

Political corruption is the use of powers by government officials or their network contacts for illegitimate private gain. Forms of corruption vary but can include bribery, lobbying, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, influen ...

. Muckraking magazines, notably ''

McClure's'', took on corporate monopolies and

political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

s while raising public awareness of chronic urban poverty, unsafe working conditions, and

social issues like

child labor

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation w ...

. Most of the muckrakers wrote nonfiction, but fictional exposés often had a major impact as well, such as those by

Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American author, muckraker journalist, and political activist, and the 1934 California gubernatorial election, 1934 Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. In his 1906 novel ''

The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a novel by American author and muckraking-journalist Upton Sinclair, known for his efforts to expose corruption in government and business in the early 20th century.

In 1904, Sinclair spent seven weeks gathering information ...

'', Sinclair exposed the unsanitary and unsafe working conditions of the meatpacking industry in graphic detail hoping to arouse working class solidarity. He quipped, "I aimed at the public's heart and by accident, I hit it in the stomach," as readers demanded and got the

Meat Inspection Act and the

Pure Food and Drug Act

The s:Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as the Wiley Act and Harvey Washington Wiley, Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws enacted by the United States Con ...

.

The journalists who specialized in exposing waste, corruption, and scandal operated at the state and local level, like

Ray Stannard Baker,

George Creel, and

Brand Whitlock. Others such as

Lincoln Steffens exposed political corruption in many large cities;

Ida Tarbell is famed for her criticisms of

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

's

Standard Oil Company

Standard Oil Company was a corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founded in 1870 by John D. Rockefeller. The ...

. In 1906,

David Graham Phillips unleashed a blistering indictment of corruption in the US Senate. Roosevelt gave these journalists their nickname when he complained they were not being helpful by raking up too much muck.

Modernization

The progressives were avid modernizers, with a belief in science and technology as the grand solution to society's flaws. They looked to education as the key to bridging the gap between their present wasteful society and technologically enlightened future society. Characteristics of progressivism included a favorable attitude toward urban–industrial society, belief in mankind's ability to improve the environment and conditions of life, belief in an obligation to intervene in economic and social affairs, a belief in the ability of experts and in the efficiency of government intervention. Scientific management, as promulgated by

Frederick Winslow Taylor

Frederick Winslow Taylor (March 20, 1856 – March 21, 1915) was an American mechanical engineer. He was widely known for his methods to improve industrial efficiency. He was one of the first management consulting, management consultants. In 190 ...

, became a watchword for industrial efficiency and elimination of waste, with the stopwatch as its symbol.

Philanthropy

The number of rich families climbed exponentially, from 100 or so millionaires in the 1870s to 4,000 in 1892 and 16,000 in 1916. Many subscribed to

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

's credo outlined in ''

The Gospel of Wealth'' that said they owed a duty to society that called for philanthropic giving to colleges, hospitals, medical research, libraries, museums, religion, and social betterment.

In the early 20th century, American philanthropy matured, with the development of very large, highly visible private foundations created by

Rockefeller and Carnegie. The largest foundations fostered modern, efficient, business-oriented operations (as opposed to "charity") designed to better society rather than merely enhance the status of the giver. Close ties were built with the local business community, as in the "community chest" movement. The

American Red Cross

The American National Red Cross is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit Humanitarianism, humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. Clara Barton founded ...

was reorganized and professionalized. Several major foundations aided the blacks in the South and were typically advised by

Booker T. Washington. By contrast, Europe and Asia had few foundations. This allowed both Carnegie and Rockefeller to operate internationally with a powerful effect.

Middle-class values

A hallmark group of the Progressive Era, the middle class became the driving force behind much of the thought and reform that took place in this time. The middle class was characterized by their rejection of the individualistic philosophy of the

Upper ten thousand. They had a rapidly growing interest in the communication and role between classes, those of which are generally referred to as the upper class, working class, farmers, and themselves. Along these lines, the founder of

Hull-House,

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

, coined the term "association" as a counter to

Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, with association referring to the search for a relationship between the classes. Additionally, the middle class (most notably women) began to move away from prior

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

domestic values. Divorce rates increased as women preferred to seek education and freedom from the home. Victorianism was pushed aside by the rise of progressivism.

Leaders and activists

Politicians

Congressman

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

was the Democratic nominee for president in 1896, 1900, and 1908. Bryan selected Woodrow Wilson as the party candidate in 1912 and became secretary of State. The anti-Bryan conservative Democrats did nominate their candidate in 1904, but otherwise Bryan and Bryan's supporters largely dominated the party from 1896 to 1914. Historian

David Sarasohn evaluated the Democratic party in the Bryan era:

Democrats erean issue-oriented party (tariff and child labor reform, trust regulation, federal income tax, direct election of senators) and an emerging national coalition (southerners, western Progressives, blue-collar ethnic voters, and liberal intellectuals), most of whom shared a grudging but genuine admiration for their titular leader, William Jennings Bryan. Indeed, it is the Commoner ryanwhose spirit, vision, and yes, political sagacity, pervades the narrative.

Jim Hogg

James Stephen Hogg (March 24, 1851March 3, 1906) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the List of Governors of Texas, 20th governor of Texas from 1891 to 1895. He was born near Rusk, Texas. Hogg was a follower of the conservativi ...

, who served as governor of Texas from 1891 to 1895, championed the causes of individuals and presided over a series of progressive reform measures during his tenure. According to Democrat

Edward M House, Texas was "the pioneer of successful progressive legislation," citing Hogg's tenure as the catalyst.

Robert M. La Follette and

his family were the dominant forces of progressivism in Wisconsin from the late 1890s to the early 1940s. Starting as a loyal organizational Republican, he broke with the bosses in the late 1890s, built up a network of local organizers loyal to him, and fought for control of the state Republican Party, with mixed success. He failed to win the nomination for governor in 1896 and 1898 before winning the

1900 gubernatorial election. As governor of Wisconsin, La Follette compiled a progressive record, implementing primary elections and tax reform. La Follette won re-election in 1902 and 1904. In 1905 the legislature elected him to the United States Senate, where he emerged as a national progressive leader, often clashing with conservatives like Senator

Nelson Aldrich

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich (/Help:IPA/English, ˈɑldɹɪt͡ʃ/; November 6, 1841 – April 16, 1915) was a prominent American politician and a leader of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party in the United States Senate, where he r ...

. He initially supported President Taft, but broke with Taft after the latter failed to push a reduction in

tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

rates. He challenged Taft for the Republican presidential nomination in the

1912 presidential election, but his candidacy was overshadowed by Theodore Roosevelt. La Follette's refusal to support Roosevelt, and especially his suicidal ranting speech before media leaders in February 1912, alienated many progressives. La Follette forfeited his stature as a national leader of progressive Republicans, while remaining a power in Wisconsin.

[Nancy C. Unger, "The 'Political Suicide' of Robert M. La Follette: Public Disaster, Private Catharsis" ''Psychohistory Review'' 21#2 (1993) pp. 187–22]

online

. La Follette supported some of President Wilson's policies, but he broke with the president over foreign policy, thereby gaining support from Wisconsin's large German and Scandinavian elements. During World War I, La Follette was the most outspoken opponent of the administration's domestic and international policies.

With the major parties each nominating conservative candidates in the

1924 presidential election, left-wing groups coalesced behind La Follette's

third-party candidacy. With the support of the

Socialist Party, farmer's groups, labor unions, and others, La Follette was strong in Wisconsin, and to a much lesser extent in the West. He called for government ownership of railroads and electric utilities, cheap credit for farmers, stronger laws to help labor unions, and protections for civil liberties. La Follette won 17% of the popular vote and carried only his home state in the face of a Republican landslide. After his death in 1925 his sons,

Robert M. La Follette Jr. and

Philip La Follette

Philip Fox La Follette (May 8, 1897August 18, 1965) was an American politician who served during the 1930s as the 27th and 29th governor of Wisconsin. La Follette first served as a Republican from 1931 until 1933, where he lost renomination in ...

, succeeded him as progressive leaders in Wisconsin.

President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

was a leader of the Progressive movement, and he championed his "

Square Deal" domestic policies, promising the average citizen fairness, breaking of trusts, regulation of railroads, and pure food and drugs. He made conservation a top priority and established many new

national parks

A national park is a nature park designated for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes because of unparalleled national natural, historic, or cultural significance. It is an area of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that is protecte ...

,

forests

A forest is an ecosystem characterized by a dense community of trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological functio ...

, and

monuments

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, historical ...

intended to preserve the nation's natural resources. In foreign policy, he

focused on Central America where he began construction of the

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

. He expanded the army and sent the

Great White Fleet on a world tour to project the United States naval power around the globe. His successful efforts to broker the end of the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

won him the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. He avoided controversial tariff and money issues. He was elected to a full term in 1904 and continued to promote progressive policies, some of which were passed in Congress. By 1906 he was moving to the left, advocating some social welfare programs, and criticizing various business practices such as trusts. The leadership of the GOP in Congress moved to the right, as did his protégé President William Howard Taft. Roosevelt broke bitterly with Taft in 1910, and also with Wisconsin's progressive leader

Robert M. La Follette. Taft defeated Roosevelt for the 1912 Republican nomination and Roosevelt set up an entirely new Progressive Party. It called for a "New Nationalism" with active supervision of corporations, higher taxes, and unemployment and old-age insurance. He supported voting rights for women but was silent on civil rights for blacks, who remained in the regular Republican fold. He lost and his new party collapsed, as conservatism dominated the GOP for decades to come. Biographer William Harbaugh argues:

:: In foreign affairs, Theodore Roosevelt's legacy is judicious support of the national interest and promotion of world stability through the maintenance of a balance of power; creation or strengthening of international agencies, and resort to their use when practicable; and implicit resolve to use military force, if feasible, to foster legitimate American interests. In domestic affairs, it is the use of government to advance the public interest. "If on this new continent", he said, "we merely build another country of great but unjustly divided material prosperity, we shall have done nothing".

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

gained a national reputation as governor of New Jersey by defeating the bosses and pushing through a progressive agenda. For a time Wilson identified himself with conservatism, but by the time he became governor of New Jersey Wilson identified himself as a radical. As president he introduced a comprehensive program of domestic legislation. He had four major domestic priorities: the

conservation of natural resources, banking reform,

tariff reduction, and opening access to raw materials by breaking up Western mining trusts. Though foreign affairs would unexpectedly dominate his presidency, Wilson's first two years in office largely focused on the implementation of his New Freedom domestic agenda. Wilson presided over the passage of his progressive

New Freedom domestic agenda. His first major priority was the passage of the

Revenue Act of 1913, which lowered

tariffs and implemented a federal

income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

. Later tax acts implemented a federal

estate tax

International tax law distinguishes between an estate tax and an inheritance tax. An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and pr ...

and raised the top income tax rate to 77 percent. Wilson also presided over the passage of the

Federal Reserve Act

The Federal Reserve Act was passed by the 63rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913. The law created the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States.

After Dem ...

, which created a central banking system in the form of the

Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

. Two major laws, the

Federal Trade Commission Act and the

Clayton Antitrust Act

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 (, codified at , ), is a part of United States antitrust law with the goal of adding further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime; the Clayton Act seeks to prevent anticompetitive practices in their inci ...

, were passed to regulate business and prevent monopolies. Wilson did not support civil rights and did not object to accelerating

segregate of federal employees. In World War I, he made internationalism a key element of the progressive outlook, as expressed in his

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

and the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

—an ideal called

Wilsonianism.

In New York Republican Governor

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

was known for exposing the insurance industry. During his time in office he promoted a range of reforms. As presidential candidate in 1916 he lost after alienating progressive California voters. As Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, he often sided with

Oliver Wendell Holmes in upholding popular reforms such as the minimum wage, workmen's compensation, and maximum work hours for women and children. He also wrote several opinions upholding the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce under the

Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amon ...

. His majority opinion in the ''Baltimore and Ohio Railroad v. Interstate Commerce Commission'' upheld the right of the federal government to regulate the hours of railroad workers.

His majority opinion in the 1914

Shreveport Rate Case upheld a decision by the

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later Trucking industry in the United States, truc ...

to void discriminatory railroad rates imposed by the

Railroad Commission of Texas

The Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC; also sometimes called the Texas Railroad Commission, TRC) is the state agency that regulates the oil and gas industry, gas utilities, pipeline safety, safety in the liquefied petroleum gas industry, and su ...

. The decision established that the federal government could regulate intrastate commerce when it affected interstate commerce, though Hughes avoided directly overruling the 1895 case of ''

United States v. E. C. Knight Co.'' As Chief Justice of the Supreme Court he took a moderate middle position and upheld key New Deal laws.

Activists and Muckrakers

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsyl ...

was an American forester and political activist who served as the first Chief of the

United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency within the United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture. It administers the nation's 154 United States National Forest, national forests and 20 United States Natio ...

from 1905 until 1910 and was the

28th Governor of Pennsylvania, serving from 1923 to 1927, and again from 1931 to 1935. He was a member of the

Republican Party for most of his life, though he also joined the

Progressive Party for a brief period. Pinchot is known for reforming the management and development of forests in the United States and for advocating the conservation of the nation's reserves by planned use and renewal. Pinchot coined the term

conservation ethic

Nature conservation is the ethic/moral philosophy and conservation movement focused on protecting species from extinction, maintaining and restoring habitats, enhancing ecosystem services, and protecting biological diversity. A range of valu ...

as applied to natural resources. Pinchot's main contribution was his leadership in promoting scientific forestry and emphasizing the controlled, profitable use of forests and other natural resources so they would be of maximum benefit to mankind.

He was the first to demonstrate the practicality and profitability of managing forests for continuous cropping. His leadership put the conservation of forests high on America's priority list.

Herbert Croly was an intellectual leader of the movement as an editor, political philosopher and a co-founder of the magazine ''

The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

''. His political philosophy influenced many leading progressives including Theodore Roosevelt,

Adolph Berle, as well as his close friends Judge

Learned Hand

Billings Learned Hand ( ; January 27, 1872 – August 18, 1961) was an American jurist, lawyer, and judicial philosopher. He served as a federal trial judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York from 1909 to 1924 a ...

and Supreme Court Justice

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

.

Croly's 1909 book ''

The Promise of American Life'' looked to the constitutional liberalism as espoused by

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

, combined with the radical

democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

of

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

. The book influenced contemporaneous progressive thought, shaping the ideas of many intellectuals and political leaders, including then ex-President Theodore Roosevelt. Calling themselves "The New Nationalists", Croly and

Walter Weyl sought to remedy the relatively weak national institutions with a strong federal government. He promoted a strong army and navy and attacked

pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

who thought democracy at home and peace abroad was best served by keeping America weak.

Croly was one of the founders of

modern liberalism in the United States

Modern liberalism, often referred to simply as liberalism, is the dominant version of liberalism in the United States. It combines ideas of civil liberty and Social equality, equality with support for social justice and a mixed economy. Modern l ...

, especially through his books, essays and a highly influential magazine founded in 1914, ''The New Republic''. In his 1914 book ''Progressive Democracy'', Croly rejected the thesis that the liberal tradition in the United States was inhospitable to

anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists seek to combat the worst effects of capitalism and to eventually replace capitalism ...

alternatives. He drew from the American past a history of resistance to

capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

wage relations that was fundamentally liberal, and he reclaimed an idea that progressives had allowed to lapse—that working for wages was a lesser form of liberty. Increasingly skeptical of the capacity of

social welfare

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance p ...

legislation to remedy social ills, Croly argued that America's liberal promise could be redeemed only by

syndicalist

Syndicalism is a labour movement within society that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes and other forms of direct action, with the eventual goal of gainin ...

reforms involving

workplace democracy

Workplace democracy is the application of democracy in various forms to the workplace, such as voting systems, consensus, debates, democratic structuring, due process, adversarial process, and systems of appeal. It can be implemented in a ...

. His liberal goals were part of his commitment to

American republicanism.

Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American author, muckraker journalist, and political activist, and the 1934 California gubernatorial election, 1934 Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

was an American writer. Sinclair's work was well known and popular in the first half of the 20th century, and he won the

Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during ...

in 1943. In 1906, Sinclair acquired particular fame for his classic

muck-raking novel ''

The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a novel by American author and muckraking-journalist Upton Sinclair, known for his efforts to expose corruption in government and business in the early 20th century.

In 1904, Sinclair spent seven weeks gathering information ...

'', which exposed labor and sanitary conditions in the U.S.

meatpacking industry, causing a public uproar that contributed in part to the passage a few months later of the 1906

Pure Food and Drug Act

The s:Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as the Wiley Act and Harvey Washington Wiley, Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws enacted by the United States Con ...

and the

Meat Inspection Act

The Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906 (FMIA) is an American law that makes it illegal to adulterate or misbrand meat and meat products being sold as food, and ensures that meat and meat products are slaughtered and processed under strictly ...

. In 1919, he published ''

The Brass Check

''The Brass Check'' is a muckraking exposé of American journalism by Upton Sinclair published in 1919. It focuses mainly on newspapers and the Associated Press wire service, along with a few magazines. Other critiques of the press had appeared ...

'', a muck-raking

exposé of American journalism that publicized the issue of

yellow journalism

In journalism, yellow journalism and the yellow press are American newspapers that use eye-catching headlines and sensationalized exaggerations for increased sales. This term is chiefly used in American English, whereas in the United Kingdom, ...

and the limitations of the "free press" in the United States. Four years after publication of ''The Brass Check'', the first

code of ethics

Ethical codes are adopted by organizations to assist members in understanding the difference between right and wrong and in applying that understanding to their decisions. An ethical code generally implies documents at three levels: codes of b ...

for journalists was created.

Ida Tarbell, a writer and lecturer, was one of the leading

muckraker

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

s and pioneered

investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, racial injustice, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend m ...

. Tarbell is best known for her 1904 book, ''

The History of the Standard Oil Company

''The History of the Standard Oil Company'' is a 1904 book by journalist Ida Tarbell. It is an exposé about the Standard Oil Company, run at the time by oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, the richest figure in American history. Originally serializ ...

.'' The work helped turn elite public opinion against the

Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

monopoly.

Lincoln Steffens was another investigative journalist and one of the leading

muckraker

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

s. He launched a series of articles in ''

McClure's'', called ''Tweed Days in St. Louis'', that would later be published together in a book titled ''

The Shame of the Cities''. He is remembered for investigating corruption in

municipal government

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the go ...

in American cities and leftist values.

Federal activity

On a federal level, progressives in Congress also influenced a number of progressive reforms, with various reform measures introduced that affected areas such as agriculture, public health and working conditions. As reflected by

William Allen White:

IN THE ELECTION of 1910 Kansas went overwhelmingly progressive Republican. The conservative faction was decisively divided. The same thing happened generally over the country north of the Mason and Dixon line. The progressive Republicans did not have a majority in either house of Congress. But they had a balance of power; amalgamation with a similar but smaller group of progressive Democrats under Bryan’s leadership gave the progressives a working majority upon most measures. They had seen the conservative Democrats and the conservative Republicans united openly, proudly, victoriously to save Speaker Cannon from the ultimate humiliation when his power was taken from him by his progressive partisans. So in the legislatures and the Congress that met in 1911 a strange new thing was revealed in American politics. Party lines were breaking down. A bipartisan party was appearing in legislatures and in the Congress. It was an undeclared third party. But when the new party appeared on the left, the conservative Democrats and the conservative Republicans generally coalesced in legislative bodies on the right. For the most part the right wing coalescents were in the minority. In Congress, on most measures, the leftwing liberals were able to command a majority. They united upon a railroad regulation bill. They united in promoting the income tax constitutional amendment. They united in submitting another amendment providing for the direct election of United States Senators, which was indeed revolutionary. But they were unable to unite in the passage of a tariff bill. Local interests in regional commodity industries like cotton, lumber, copper, wool, and textiles were able to form a conservative alliance which, under the leadership of President Taft in the White House, put through a tariff bill that was an offense to the nation. But otherwise the new party of reform which had grown up in ten years dominated politics in Washington and in the state legislatures north of the Ohio from New England to California.

State and local activity

According to James Wright, the typical progressive agenda at the state level included:

A reduction of corporate influence, open processes of government and politics, equity entrance in taxation, efficiency in government mental operation, and an expanded, albeit limited, state responsibility to the citizens who are most vulnerable and deprived.

In the South, prohibition was high on the agenda but controversial. Jim Crow and disenfranchisement of Black voters was even higher on the agenda. In the Western states,

woman suffrage was a success story, but racist anti-Asian sentiment also prevailed. In the East, every state had a progressive movement, but the conservative forces were usually more powerful. As an organized grassroots insurgency force the progressive movement was weak in New England. For example, "Massachusetts never caught the spirit of change which dominated the era, and consequently it appeared, at best, merely conservative." When Theodore Roosevelt became governor of New York in 1898, his progressivism annoyed party leaders. They ended his reelection plans in 1900 by getting him placed on the national ticket as McKinley's running mate for vice president. Belatedly progressivism emerged around 1905 under Governor

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

.

Western states

Oregon

The Oregon

Direct Legislation League was an organization of political activists founded by

William S. U'Ren in 1898. Oregon was one of the few states where former

Populists like U'Ren became progressive leaders. U'Ren had been inspired by reading the influential 1893 book ''Direct Legislation Through the Initiative and Referendum'',

and the group's founding followed in the wake of the 1896 founding of the National Direct Legislation League, which itself had its roots in the Direct Legislation League of

New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

and its short-lived predecessor, the People's Power League.

The group led efforts in Oregon to establish an

initiative

Popular initiative

A popular initiative (also citizens' initiative) is a form of direct democracy by which a petition meeting certain hurdles can force a legal procedure on a proposition.

In direct initiative, the proposition is put direct ...

and

referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

system, allowing direct legislation by the state's citizens. In 1902, the

Oregon Legislative Assembly approved such a system, which was known at the time as the "

Oregon System".

The group's further efforts led to successful ballot initiatives implementing a

direct primary system in 1904, and allowing citizens to

directly recall public officials in 1908.

Democrats who promoted progressive policies included

George Earle Chamberlain (governor 1903–1909 and senator 1909–1921);

Oswald West

Oswald West (May 20, 1873 – August 22, 1960) was an American politician, a Democrat, who served most notably as the 14th Governor of Oregon.

Early life

West was born in Guelph, Ontario, Canada but moved to Salem, Oregon with his family at t ...

(governor 1911–1915); and

Harry Lane (senator 1913–1917). The most important Republican was

Jonathan Bourne Jr. (senator 1907–1913 and national leader of progressive causes 1911–1912).

California

California built the most successful grass roots progressive movement in the country by mobilizing independent organizations and largely ignoring the conservative state parties. The system continues strong into the 21st century. Following the Oregon model,

John Randolph Haynes organized the

Direct Legislation League of California in 1902 to launch the campaign for inclusion of the initiative and referendum in the state's constitution.

The League sent questionnaires to prospective candidates to the state legislature to obtain their stance on direct legislation and to make those positions public. It then flooded the state with letters seeking new members, money, and endorsements from organizations like the State Federation of Labor. As membership grew it worked with other private organizations to petition the state legislature, which was not responsive. In 1902 the League won a state constitutional amendment establishing direct democracy at the local level, and in 1904, it successfully engineered the recall of the first public official.

South

Progressivism was strongest in the cities, but the South was rural with few large cities. Nevertheless, statewide progressive movements were organized by Democrats in every Southern state. Furthermore, Southern Democrats in Congress gave strong support to President Wilson's reforms.

African American role

African Americans developed their own version of the Progressive Movement, with two different approaches led in the South by

Booker T. Washington and the Black business community, versus

W.E.B. DuBois and the

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

in the North.

The South was a main target of Northern philanthropy designed to fight poverty and disease, and help the black community.

Booker T. Washington of the

National Negro Business League mobilized small black-owned business and secured access to Northern philanthropy. Across the South the

General Education Board (funded by the

Rockefeller family

The Rockefeller family ( ) is an American Industrial sector, industrial, political, and List of banking families, banking family that owns one of the world's largest fortunes. The fortune was made in the History of the petroleum industry in th ...

) provided large-scale subsidies for black schools, which otherwise continued to be underfunded. The South was targeted in the 1920s and 1930s by the

Julius Rosenwald Fund, which contributed matching funds to local communities for the construction of thousands of schools for African Americans in rural areas throughout the South. Black parents donated land and labor to build improved schools for their children.

North Carolina

North Carolina took a leadership role in modernizing the south, notably in expansion of public education and the state university system and improvements in transportation, which earned it the nickname "The Good Roads State." State leaders included Governor

Charles B. Aycock, who led both the educational and the white supremacy crusades; diplomat

Walter Hines Page; and educator

Charles Duncan McIver. Women were especially active through the

WCTU, the Baptist church, overseas missions, local public schools, and in the cause of prohibition, leading North Carolina to become the first southern state to implement statewid

prohibition Progressives worked to limit child labor in textile mills and supported public health campaigns to eradicate

hookworm

Hookworms are Gastrointestinal tract, intestinal, Hematophagy, blood-feeding, parasitic Nematode, roundworms that cause types of infection known as helminthiases. Hookworm infection is found in many parts of the world, and is common in areas with ...

and other debilitating diseases. While the majority of North Carolininans continued to support traditional gender roles, and state legislators did not ratify the

Nineteenth Amendment until 1971, Progressive reformers like

Gertrude Weil and Dr.

Elizabeth Delia Dixon Carroll lobbied for

woman suffrage.

Following the

Wilmington massacre, North Carolina imposed strict legal segregation and rewrote its constitution in order to

disfranchise Black men through poll taxes and literacy tests. In the Black community,

Charlotte Hawkins Brown built the

Palmer Memorial Institute to provide a liberal arts education to Black children and promote excellence and leadership. Brown worked with

Booker T. Washington (in his role with the

National Negro Business League), who provided ideas and access to Northern philanthropy.

Midwest

Apart from Wisconsin, the Midwestern states were about average in supporting Progressive reforms. Ohio took the lead in municipal reform.

The negative effects of industrialization triggered the political movement of progressivism, which aimed to address its negative consequences through social reform and government regulation.

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

and

Ellen Gates Starr pioneered the settlement house outreach to newly arrived immigrants by establishing

Hull House in Chicago in 1889. Settlement houses provided social services and played an active role in civic life, helping immigrants prepare for naturalization and campaigning for regulation and services from city government. Midwestern mayors—especially

Hazen S. Pingree and

Tom L. Johnson, led early reforms against boss-dominated municipal politics, while

Samuel M. Jones advocated public ownership of local utilities.

Robert M. La Follette, the most famous leader of Midwestern progressivism, began his career by winning election against his state's Republican party in 1900. The machine was temporarily defeated, allowing reformers to launch the "

Wisconsin idea" of expanded democracy. This idea included major reforms such as direct primaries, campaign finance, civil service, anti-lobbying laws, state income and inheritance taxes, child labor restrictions, pure food, and workmen's compensation laws. La Follette promoted government regulation of railroads, public utilities, factories, and banks. Although La Follette lost influence in the national party in 1912, the Wisconsin reforms became a model for national progressivism.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin from 1900 to the late 1930s was a regional and national model for innovation and organization in the progressive movement. The direct primary made it possible to mobilize voters against the previously dominant political machines. The first factors involved the

La Follette family going back and forth between trying to control of the Republican Party and if frustrated trying third-party activity especially in 1924 and the 1930s. Secondly the

Wisconsin idea, of intellectuals and planners based at the University of Wisconsin shaping government policy. LaFollette started as a traditional Republican in the 1890s, where he fought against populism and other radical movements. He broke decisively with the state Republican leadership, and took control of the party by 1900, all the time quarreling endlessly with ex-allies.

The Democrats were a minor conservative factor in Wisconsin. The Socialists, with a strong German and union base in Milwaukee, joined the progressives in statewide politics. Senator

Robert M. La Follette tried to use his national reputation to challenge President Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912. However, as soon as Roosevelt declared his candidacy, most of La Follette's supporters switched away. La Follette supported many of his Wilson's domestic programs in Congress. However he strongly opposed Wilson's foreign policy, and mobilized the large German and Scandinavian elements which demanded neutrality in the World War I. He finally ran

an independent campaign for president in 1924 that appealed to the German Americans, labor unions, socialists, and more radical reformers. He won 1/6 of the national vote, but carried only his home state. After his death in 1925 his two sons took over the party. They serve terms as governor and senator and set up a third party in the state. The third party fell apart in the 1930s, and totally collapsed by 1946.

The

Wisconsin Idea was the commitment of the

University of Wisconsin

A university () is an institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars". Uni ...

under President

Charles R. Van Hise, with LaFollette support, to use the university's powerful intellectual resources to develop practical progressive reforms for the state and indeed for the nation.

Between 1901 and 1911, Progressive Republicans in Wisconsin created the nation's first comprehensive statewide

primary election system, the first effective

workplace injury compensation law, and the first state

income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

, making taxation proportional to actual earnings. The key leaders were

Robert M. La Follette and (in 1910) Governor

Francis E. McGovern. However, in 1912 McGovern supported Roosevelt for president and LaFollette was outraged. He made sure the next legislature defeated the governor's programs, and that McGovern was defeated in his bid for the Senate in 1914. The Progressive movement split into hostile factions. Some was based on personalities—especially La Follette's style of violent personal attacks against other Progressives, and some was based on who should pay, with the division between farmers (who paid property taxes) and the urban element (which paid income taxes). This disarray enabled the conservatives (called "Stalwarts") to elect

Emanuel Philipp as governor in 1914. The Stalwart counterattack said the Progressives were too haughty, too beholden to experts, too eager to regulate, and too expensive. Economy and budget cutting was their formula.

The progressive

Wisconsin Idea promoted the use of the University of Wisconsin faculty as intellectual resources for state government, and as guides for local government. It promoted expansion of the university through the

UW-Extension system to reach all the state's farming communities. University economics professors

John R. Commons and Harold Groves enabled Wisconsin to create the first

unemployment compensation program in the United States in 1932. Other

Wisconsin Idea scholars at the university generated the plan that became the New Deal's

Social Security Act

The Social Security Act of 1935 is a law enacted by the 74th United States Congress and signed into law by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on August 14, 1935. The law created the Social Security (United States), Social Security program as ...

of 1935, with Wisconsin expert

Arthur J. Altmeyer playing the key role. The Stalwarts counterattacked by arguing if the university became embedded in the state, then its internal affairs became fair game, especially the faculty preference for advanced research over undergraduate teaching. The Stalwarts controlled the Regents, and their interference in academic freedom outraged the faculty. Historian

Frederick Jackson Turner, the most famous professor, quit and went to Harvard.

Illinois

Chicago was a hotbed for reform, led by the

Hull House circle. Philosopher

John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and Education reform, educational reformer. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the first half of the twentieth century.

The overridi ...

and

Ella Flagg Young at the University of Chicago's Laboratory School influenced educational philosophy and practice nationwide. The collaboration between Dewey and Hull House residents shaped progressive education reforms that were adopted in other parts of the country.

Florence Kelley

Florence Molthrop Kelley (September 12, 1859 – February 17, 1932) was an American social and political reformer who coined the term wage abolitionism. Her work against sweatshops and for the minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, and children's ...

worked at Hull House from 1891 to 1899 and was appointed Illinois's first chief factory inspector in 1893. She used this position to expose abusive working conditions, especially for children, and successfully lobbied for the creation of the federal

Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is a unit of the United States Department of Labor. It is the principal fact-finding agency for the government of the United States, U.S. government in the broad field of labor economics, labor economics and ...

.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett moved to Chicago in 1895 and became a leading civil rights journalist and anti-lynching activist. She founded the Illinois Negro Women's Club and the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, worked as a probation officer, and helped establish the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

(NAACP) in 1910.

=Jane Addams

=

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

was an American

settlement activist, reformer, social worker,

sociologist,

public administrator and author. She was a notable figure in the history of social work and

women's suffrage in the United States

Women's suffrage, or the right of women to vote, was established in the United States over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, first in various U.S. states, states and localities, then nationally in 1920 with the ratification ...

and an advocate of

world peace

World peace is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would come about.

Various relig ...

. She co-founded Chicago's

Hull House, one of America's most famous settlement houses. In 1920, she was a co-founder for the

American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an American nonprofit civil rights organization founded in 1920. ACLU affiliates are active in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The budget of the ACLU in 2024 was $383 million.

T ...

(ACLU). In 1931, she became the first American woman to be awarded the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

, and is recognized as the founder of the social work profession in the United States. Maurice Hamington considered her a radical

pragmatist and the first woman "public philosopher" in the United States. In the 1930s, she was the best-known female public figure in the United States.

Kansas

State leaders in reform included editor

William Allen White, who reached a national audience, and Governor

Walter R. Stubbs. According to Gene Clanton's study of Kansas, populism and progressivism have a few similarities but different bases of support. Both opposed corruption and trusts. Populism emerged earlier and came out of the farm community. It was radically egalitarian in favor of the disadvantaged classes. It was weak in the towns and cities except in labor unions. Progressivism, on the other hand, was a later movement. It emerged after the 1890s from the urban business and professional communities. Most of its activists had opposed populism. It was elitist, and emphasized education and expertise. Its goals were to enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and enlarge the opportunities for upward social mobility. However, some former Populists changed their emphasis after 1900 and supported progressive reforms.

Ohio

Ohio was distinctive for municipal reform in the major cities, especially Toledo, Cleveland, Columbus, and Dayton. The middle class lived in leafy neighborhoods in the city and took the trolley to work in downtown offices. The working class saved money by walking to their factory jobs; municipal reformers appealed to the middle-class vote, by attacking the high fares and mediocre service of privately owned transit companies. They often proposed city ownership of the transit lines, but the homeowners were reluctant to save a penny on fares by paying more dollars in property taxes

Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is a city in Montgomery County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of cities in Ohio, sixth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 137,644 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Dayton metro ...

, was under the reform leadership of

John Patterson, the hard-charging chief executive of

National Cash Register company. He appealed to the businessman with the gospel of efficiency in municipal affairs, run by non-partisan experts like himself. He wanted a city manager form of government in which outside experts would bring efficiency while elected officials would have little direct power, and bribery would not prevail. When the city council balked at his proposals, he threatened to move the National Cash Register factories to another city, and they fell in line. A massive flood in Dayton in 1913 killed 400 people and caused $100 million in property damage. Patterson took charge of the relief work and demonstrated in person the sort of business leaders he proposed. Dayton adopted his policies; by 1920, 177 American cities had followed suit and adopted city manager governments.

Iowa

Iowa had a mixed record. The spirit of progressivism emerged in the 1890s, peaked in the 1900s, and decayed after 1917. Under the guidance of Governor (1902–1908) and Senator (1908–1926)

Albert Baird Cummins the "Iowa Idea" played a role in state and national reform. A leading Republican, Cummins fought to break up monopolies. His Iowa successes included establishing the direct primary to allow voters to select candidates instead of bosses; outlawing free railroad passes for politicians; imposing a two-cents-per-mile railway maximum passenger fare; imposing pure food and drug laws; and abolishing corporate campaign contributions. He tried, without success, to lower the high protective tariff in Washington.

Women put

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

on the state agenda. It was led by local chapters of the

Woman's Christian Temperance Union, whose main goal was to impose prohibition. In keeping with the general reform mood of the latter 1860s and 1870s, the issue first received serious consideration when both houses of the General Assembly passed a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution in 1870. Two years later, however, when the legislature had to consider the amendment again before it could be submitted to the general electorate. It was defeated because interest had waned, and strong opposition had developed especially in the

German-American

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

community, which feared women would impose prohibition. Finally, in 1920, Iowa got woman suffrage with the rest of the country by the 19th amendment to the federal Constitution.

Key ideas and issues

According to historian Nancy Cohen:

During the Progressive Era . . . the minimal state of an earlier liberalism was abandoned in favor of one with the power to intervene in the market and to promote social welfare. The progressives’ new liberalism, most historians conclude, was fundamentally reformist; it sought to use state power to regulate the capitalist economy and to improve the living conditions and ‘‘security’’ of the citizenry, without abolishing private property or revolutionizing liberal democratic political institutions.

Antitrust

Standard Oil, with its near monopoly on refining oil, was widely hated. Many newspapers reprinted attacks from a flagship Democratic newspaper, ''The New York World'', which made this trust a special target. There were legal efforts to curtail the oil monopoly in the Midwest and South. Tennessee, Illinois, Kentucky and Kansas took the lead in 1904–1905, followed by Arkansas, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, and West Virginia. The results were mixed. Federal action finally won out in 1911, splitting Standard Oil into 33 companies. The 33 seldom competed with each other. The federal decision together with the

Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 (, codified at , ), is a part of United States antitrust law with the goal of adding further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime; the Clayton Act seeks to prevent anticompetitive practices in their incip ...

and the creation that year of the

Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) United States antitrust law, antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. It ...

largely de-escalated the antitrust rhetoric among progressives. The new framework after 1914 had little or no impact on the direction and magnitude of merger activity.

Primaries

By 1890, the secret ballot was widely adopted by the states for elections, which was non-controversial and resulted in the elimination of purchased votes since the purchaser couldn't determine how the voter cast their vote. Despite this change, the candidates were still selected by party conventions. In the 1890s, the South witnessed a decrease in the possibility of Republican or Populist or coalition victories in most elections, with the Democratic Party gaining full control over all statewide Southern elections. To prevent factionalism within the Democratic Party, Southern states began implementing primaries. However, candidates who competed in the primaries and lost were prohibited from running as independents in the fall election. Louisiana was the first state to introduce primaries in 1892, and by 1907, eleven Southern and border states had implemented statewide primaries.

In the North, Robert LaFollette introduced the primary in Wisconsin in 1904. Most Northern states followed suit, with reformers proclaiming grass roots democracy. The party leaders and bosses also wanted direct primaries to minimize the risk of sore losers running as independents.

When candidates for office were selected by the party caucus (meetings open to the public) or by statewide party conventions of elected delegates, the public lost a major opportunity to shape policy. The progressive solution was the "open" primary by which any citizen could vote, or the "closed" primary limited to party members. In the early 20th century most states adopted the system for local and state races—but only 14 used it for delegates to the national presidential nominating conventions. The biggest battles came in New York state, where the conservatives fought hard for years against several governors until the primary was finally adopted in 1913.

Government reform

Disturbed by the waste, inefficiency, stubbornness, corruption, and injustices of the

Gilded Age

In History of the United States, United States history, the Gilded Age is the period from about the late 1870s to the late 1890s, which occurred between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was named by 1920s historians after Mar ...

, the Progressives were committed to changing and reforming every aspect of the state, society and economy. Significant changes enacted at the national levels included the imposition of an

income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

with the

Sixteenth Amendment, direct election of

Senators with the

Seventeenth Amendment,

prohibition of alcohol

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

with the

Eighteenth Amendment, election reforms to stop corruption and fraud, and

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

through the

Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

A main objective of the Progressive Era movement was to eliminate corruption within the government. They also made it a point to focus on family, education, and many other important aspects that still are enforced today. The most important political leaders during this time were Theodore Roosevelt and Robert M. La Follette. Key Democratic leaders were

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

,

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, and

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was the 42nd governor of New York, serving from 1919 to 1920 and again from 1923 to 1928. He was the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party's presidential nominee in the 1 ...

.

This movement targeted the regulations of huge monopolies and corporations. This was done through antitrust laws to promote equal competition among every business. This was done through the

Sherman Act of 1890, the

Clayton Act of 1914, and the

Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914

The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 is a United States federal law which established the Federal Trade Commission. The Act was signed into law by US President Woodrow Wilson in 1914 and Trade regulation, outlaws unfair methods of Competitio ...

.

City manager

At the local level the new

city manager

A city manager is an official appointed as the administrative manager of a city in the council–manager form of city government. Local officials serving in this position are referred to as the chief executive officer (CEO) or chief administ ...

system was designed by progressives to increase efficiency and reduce partisanship and avoid the bribery of elected local officials. Kansas was a leader, where it was promoted in the press, led by Henry J. Allen of the ''Wichita Beacon'', and pushed through by Governor

Arthur Capper. Eventually 52 Kansas cities used the system.

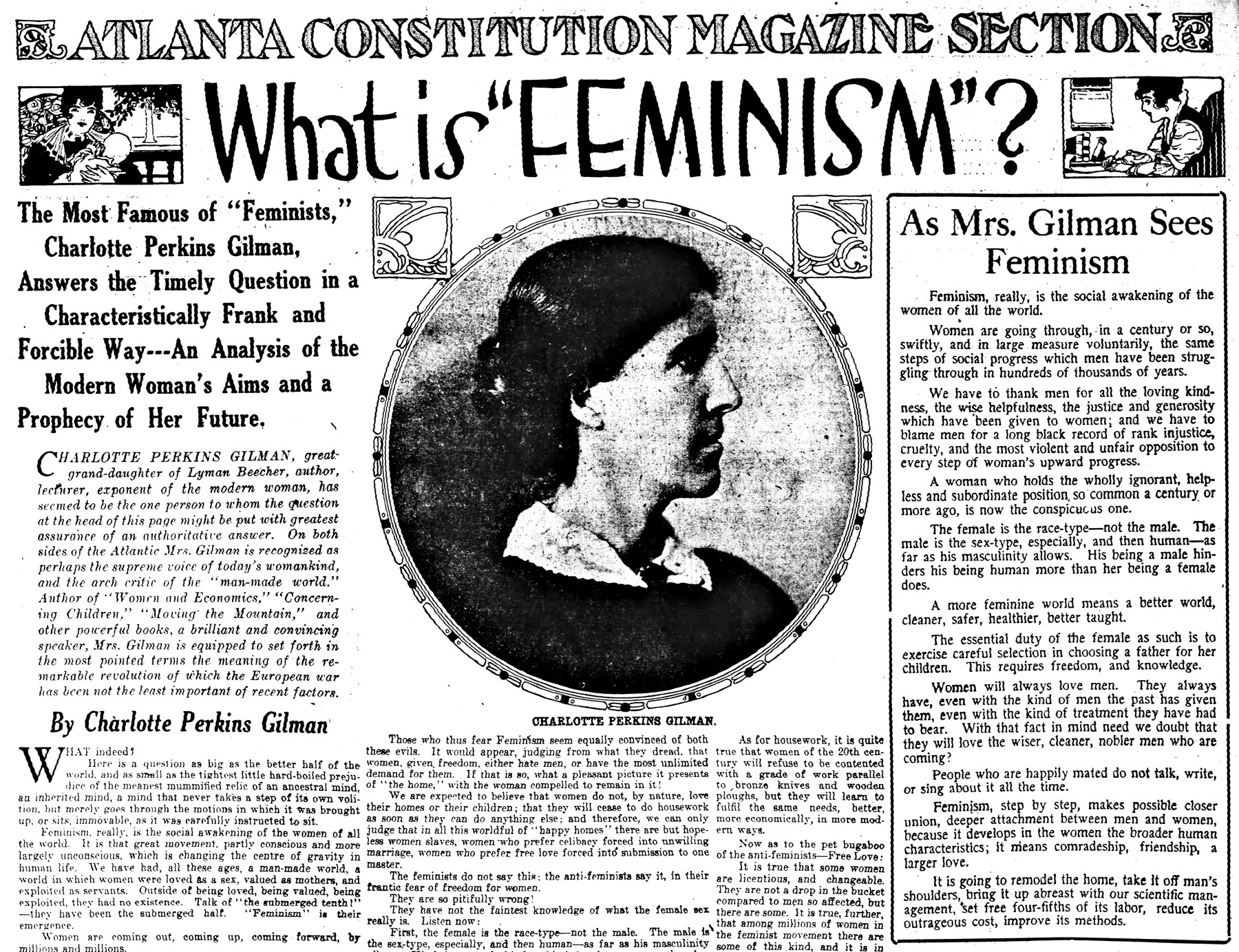

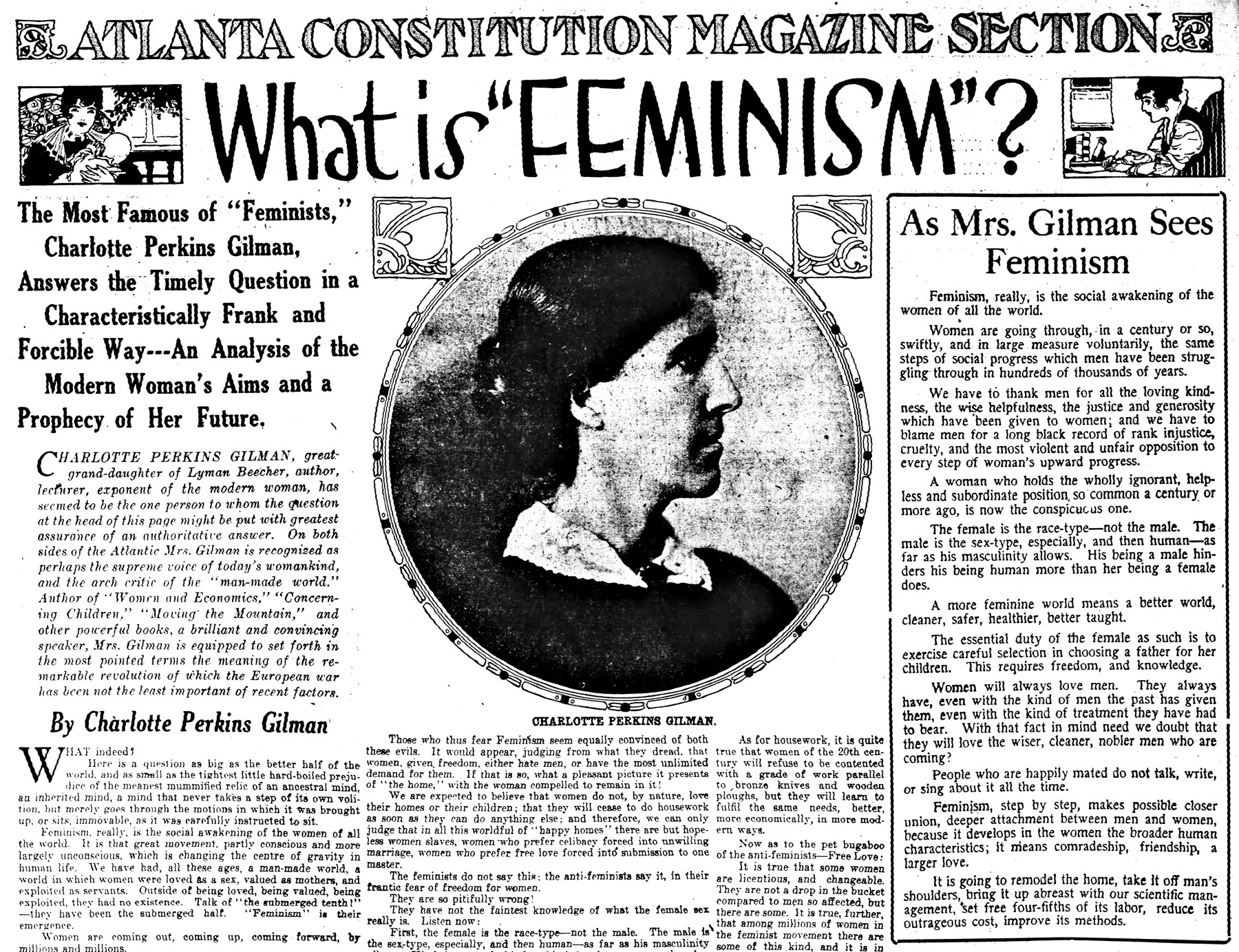

Family roles

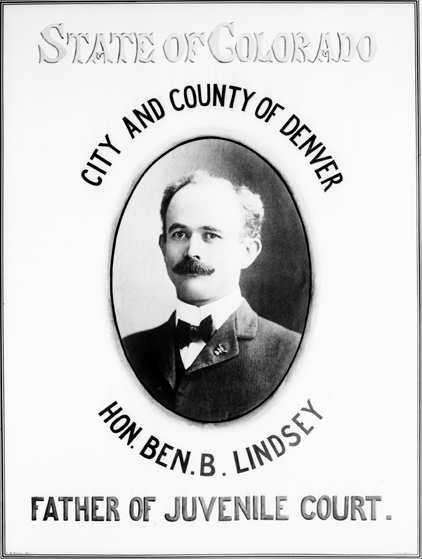

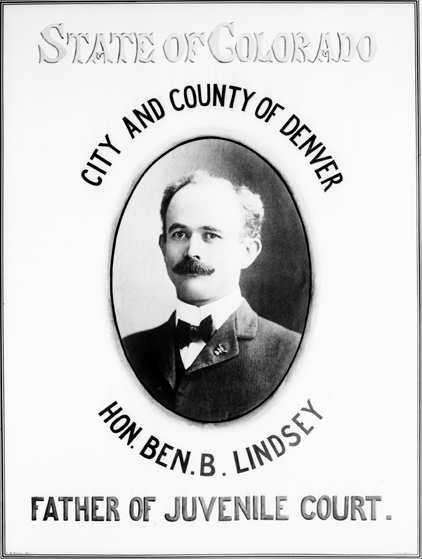

By the late 19th century, urban and rural governments had systems in place for welfare to the poor and incapacitated. Progressives argued these needs deserved a higher priority. Local

public assistance programs were reformed to try to keep families together. Inspired by crusading Judge

Ben Lindsey of Denver, cities established juvenile courts to deal with disruptive teenagers without sending them to adult prisons.

Pure food, drugs, and water

The purity of food, milk, and drinking water became a high priority in the cities. At the state and national levels new food and drug laws strengthened urban efforts to guarantee the safety of the

food system. The 1906 federal

Pure Food and Drug Act