Pre-experimental Science on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Science in classical antiquity encompasses inquiries into the workings of the world or universe aimed at both practical goals (e.g., establishing a reliable calendar or determining how to cure a variety of illnesses) as well as more abstract investigations belonging to

The earliest

The earliest

A good example of the level of achievement in astronomical knowledge and engineering during the Hellenistic age can be seen in the

A good example of the level of achievement in astronomical knowledge and engineering during the Hellenistic age can be seen in the

Science during the

Science during the

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 AD), living in or around

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 AD), living in or around

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

. Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

is traditionally defined as the period between the 8th century BC (beginning of Archaic Greece

Archaic Greece was the period in History of Greece, Greek history lasting from to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical Greece, Classical period. In the archaic period, the ...

) and the 6th century AD (after which there was medieval science). It is typically limited geographically to the Greco-Roman West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

, Mediterranean basin, and Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

, thus excluding traditions of science in the ancient world in regions such as China and the Indian subcontinent.

Ideas regarding nature that were theorized during classical antiquity were not limited to science but included myths as well as religion. Those who are now considered as the first scientists

A scientist is a person who researches to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosophical study of nature ...

may have thought of themselves as natural philosophers

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

, as practitioners of a skilled profession (e.g., physicians), or as followers of a religious tradition (e.g., temple healers). Some of the more widely known figures active in this period include Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

, Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

, Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; , ; BC) was a Ancient Greek astronomy, Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. Hippar ...

, Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

, and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

. Their contributions and commentaries spread throughout the Eastern, Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, and Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

worlds and contributed to the birth of modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as al ...

. Their works covered many different categories including mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, and physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

.

Classical Greece

Knowledge of causes

This subject inquires into the nature of things first began out of practical concerns among theancient Greeks

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically re ...

. For instance, an attempt to establish a calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A calendar date, date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is ...

is first exemplified by the ''Works and Days'' of the Greek poet Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

, who lived around 700 BC. Hesiod's calendar was meant to regulate seasonal activities by the seasonal appearances and disappearances of the stars, as well as by the phases of the Moon, which were held to be propitious or ominous. Around 450 BC we begin to see compilations of the seasonal appearances and disappearances of the stars in texts known as ''parapegmata'', which were used to regulate the civil calendars of the Greek city-states on the basis of astronomical observations.

Medicine is another area where practically oriented investigations of nature took place during this period. Greek medicine was not the province of a single trained profession and there was no accepted method of qualification of licensing. Physicians in the Hippocratic

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referred to as the "Fat ...

tradition, temple healers associated with the cult of Asclepius

Asclepius (; ''Asklēpiós'' ; ) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of Apollo), Coronis, or Arsinoe (Greek myth), Ars ...

, herb collectors, drug sellers, midwives, and gymnastic trainers all claimed to be qualified as healers in specific contexts and competed actively for patients. This rivalry among these competing traditions contributed to an active public debate about the causes and proper treatment of disease, and about the general methodological approaches of their rivals.

An example of the search for causal explanations is found in the Hippocratic text '' On the Sacred Disease'', which deals with the nature of epilepsy. In it, the author attacks his rivals (temple healers) for their ignorance in attributing epilepsy to divine wrath, and for their love of gain. Although the author insists that epilepsy has a natural cause, when it comes to explain what that cause is and what the proper treatment would be, the explanation is as short on specific evidence and the treatment as vague as that of his rivals. Nonetheless, observations of natural phenomena continued to be compiled in an effort to determine their causes, as for instance in the works of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, who wrote extensively on animals and plants. Theophrastus also produced the first systematic attempt to classify mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

s and rocks, a summary of which is found in Pliny's ''Natural History

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

.''

The legacy of Greek science in this era included substantial advances in factual knowledge due to empirical research (e.g., in zoology, botany, mineralogy, and astronomy), an awareness of the importance of certain scientific problems (e.g., the problem of change and its causes), and a recognition of the methodological significance of establishing criteria for truth (e.g., applying mathematics to natural phenomena), despite the lack of universal consensus in any of these areas.

Pre-Socratic philosophy

Materialist philosophers

Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics ...

, known as the pre-Socratics

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

, were materialists who provided alternative answers to the same question found in the myths of their neighbors: "How did the ordered cosmos

The cosmos (, ; ) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos is studied in cosmologya broad discipline covering ...

in which we live come to be?" Although the question is much the same, their answers and their attitude towards the answers is markedly different. As reported by such later writers as Aristotle, their explanations tended to center on the material source of things.

Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; ; ) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Philosophy, philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. Thales was one of the Seven Sages of Greece, Seven Sages, founding figure ...

of Miletus (624–546 BC) considered that all things came to be from and find their sustenance in water. Anaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

(610–546 BC) then suggested that things could not come from a specific substance like water, but rather from something he called the "boundless". Exactly what he meant is uncertain but it has been suggested that it was boundless in its quantity, so that creation would not fail; in its qualities, so that it would not be overpowered by its contrary; in time, as it has no beginning or end; and in space, as it encompasses all things. Anaximenes (585–525 BC) returned to a concrete material substance, air, which could be altered by rarefaction and condensation. He adduced common observations (the wine stealer) to demonstrate that air was a substance and a simple experiment (breathing on one's hand) to show that it could be altered by rarefaction and condensation.

Heraclitus

Heraclitus (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Empire. He exerts a wide influence on Western philosophy, ...

of Ephesus (about 535–475 BC), then maintained that change, rather than any substance was fundamental, although the element fire seemed to play a central role in this process. Finally, Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

of Acragas (490–430 BC), seems to have combined the views of his predecessors, asserting that there are four elements (Earth, Water, Air and Fire) which produce change by mixing and separating under the influence of two opposing "forces" that he called Love and Strife.

All these theories imply that matter is a continuous substance. Two Greek philosophers, Leucippus

Leucippus (; , ''Leúkippos''; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. He is traditionally credited as the founder of atomism, which he developed with his student Democritus. Leucippus divided the world into two entities: atoms, indivisible ...

(first half of the 5th century BC) and Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

came up with the notion that there were two real entities: atoms

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished from each other ...

, which were small indivisible particles of matter, and the void, which was the empty space in which matter was located. Although all the explanations from Thales to Democritus involve matter, what is more important is the fact that these rival explanations suggest an ongoing process of debate in which alternate theories were put forth and criticized.

Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon ( ; ; – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer. He was born in Ionia and travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early classical antiquity.

As a poet, Xenophanes was known f ...

of Colophon prefigured paleontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure ge ...

and geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

as he thought that periodically the earth and sea mix and turn all to mud, citing several fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s of sea creatures that he had seen.

Pythagorean philosophy

The materialist explanations of the origins of the cosmos were attempts at answering the question of how an organized universe came to be; however, the idea of a random assemblage of elements (e.g., fire or water) producing an ordered universe without the existence of some ordering principle remained problematic to some. One answer to this problem was advanced by the followers ofPythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

(c. 582–507 BC), who saw number as the fundamental unchanging entity underlying all the structure of the universe. Although it is difficult to separate fact from legend, it appears that some Pythagoreans believed matter to be made up of ordered arrangements of points according to geometrical principles: triangles, squares, rectangles, or other figures. Other Pythagoreans saw the universe arranged on the basis of numbers, ratios, and proportions, much like musical scales. Philolaus, for instance, held that there were ten heavenly bodies because the sum of 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 gives the perfect number 10. Thus, the Pythagoreans were some of the first to apply mathematical principles to explain the rational basis of an orderly universe—an idea that was to have immense consequences in the development of scientific thought.

Hippocrates and the Hippocratic Corpus

According to tradition, the physician Hippocrates of Kos (460–370 BC) is considered the "father of medicine" because he was the first to make use ofprognosis

Prognosis ( Greek: πρόγνωσις "fore-knowing, foreseeing"; : prognoses) is a medical term for predicting the likelihood or expected development of a disease, including whether the signs and symptoms will improve or worsen (and how quickly) ...

and clinical observation, to categorize diseases, and to formulate the ideas behind humoral theory

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 17th ce ...

. However, most of the Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: ''Corpus Hippocraticum''), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus cov ...

—a collection of medical theories, practices, and diagnoses—was often attributed to Hippocrates with very little justification, thus making it difficult to know what Hippocrates actually thought, wrote, and did.

Despite their wide variability in terms of style and method, the writings of the Hippocratic Corpus had a significant influence on the medical practice of Islamic and Western medicine for more than a thousand years.

Schools of philosophy

The Academy

The first institution of higher learning in Ancient Greece was founded byPlato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

(c. 427 – c. 347 BC), an Athenian who —Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

(384–322 BC) studied at the Academy and nonetheless disagreed with Plato in several important respects. While he agreed that truth must be eternal and unchanging, Aristotle maintained that the world is knowable through experience and that we come to know the truth by what we perceive with our senses. For him, directly observable things are real; ideas (or as he called them, forms) only exist as they express themselves in matter, such as in living things, or in the mind of an observer or artisan.

Aristotle's theory of reality led to a different approach to science. Unlike Plato, Aristotle emphasized observation of the material entities which embody the forms. He also played down (but did not negate) the importance of mathematics in the study of nature. The process of change took precedence over Plato's focus on eternal unchanging ideas in Aristotle's philosophy. Finally, he reduced the importance of Plato's forms to one of four causal factors.

Aristotle thus distinguished between four causes

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelianism, Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: #Material, material cause, the #Formal, f ...

:

* the matter of which a thing was made (the material cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, a ...

).

* the form into which it was made (the formal cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

; similar to Plato's ideas).

* the agent who made the thing (the moving or efficient cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

).

* the purpose for which the thing was made (the final cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

).

Aristotle insisted that scientific knowledge (Ancient Greek: ἐπιστήμη, Latin: ) is knowledge of necessary causes. He and his followers would not accept mere description or prediction as science. Most characteristic of Aristotle's causes is his final cause, the purpose for which a thing is made. He came to this insight through his biological researches, such as those of marine animals at Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

, in which he noted that the organs of animals serve a particular function:

:The absence of chance and the serving of ends are found in the works of nature especially. And the end for the sake of which a thing has been constructed or has come to be belongs to what is beautiful.

The Lyceum

After Plato's death, Aristotle left the Academy and traveled widely before returning to Athens to found a school adjacent to the Lyceum. As one of the most prolific natural philosophers of Antiquity, Aristotle wrote and lecture on many topics of scientific interest, includingbiology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, and physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

. He developed a comprehensive physical theory

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain, and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experi ...

that was a variation of the classical theory of the elements (earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

, fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

, air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

, and aether). In his theory, the light elements (fire and air) have a natural tendency to move away from the center of the universe while the heavy elements (earth and water) have a natural tendency to move toward the center of the universe, thereby forming a spherical Earth. Since the celestial bodies (i.e., the planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

s and star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

s) were seen to move in circles, he concluded that they must be made of a fifth element, which he called aether.

Aristotle used intuitive ideas to justify his reasoning and could point to the falling stone, rising flames, or pouring water to illustrate his theory. His laws of motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

emphasized the common observation that friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal -- an incomplete list. The study of t ...

was an omnipresent phenomenon: that any body in motion would, unless acted upon, ''come to rest''. He also proposed that heavier objects fall faster, and that voids

Void may refer to:

Science, engineering, and technology

* Void (astronomy), the spaces between galaxy filaments that contain no galaxies

* Void (composites), a pore that remains unoccupied in a composite material

* Void, synonym for vacuum, ...

were impossible.

Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum was Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, who wrote valuable books describing plant and animal life. His works are regarded as the first to put botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

and zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

on a systematic footing. Theophrastus' work on mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

provided descriptions of ores and minerals known to the world at that time, making some shrewd observations of their properties. For example, he made the first known reference to the phenomenon that the mineral tourmaline

Tourmaline ( ) is a crystalline silicate mineral, silicate mineral group in which boron is chemical compound, compounded with chemical element, elements such as aluminium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lithium, or potassium. This gemstone comes in a ...

attracts straws and bits of wood when heated, now known to be caused by pyroelectricity. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

makes clear references to his use of the work in his ''Natural History

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

'', while updating and making much new information available on minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): M ...

himself. From both these early texts was to emerge the science of mineralogy, and ultimately geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

. Both authors describe the sources of the minerals they discuss in the various mines exploited in their time, so their works should be regarded not just as early scientific texts, but also important for the history of engineering and the history of technology

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques by humans. Technology includes methods ranging from simple stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and information technology that has emerged since the 19 ...

.Lloyd (1970), pp. 144–6.

Other notable peripatetics include Strato, who was a tutor in the court of the Ptolemies and who devoted time to physical research, Eudemus, who edited Aristotle's works and wrote the first books on the history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient history, ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural science, natural, social science, social, and formal science, formal. Pr ...

, and Demetrius of Phalerum

Demetrius of Phalerum (also Demetrius of Phaleron or Demetrius Phalereus; ; c. 350 – c. 280 BC) was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophrastus, and perhaps of Aristotle, he was one of the ...

, who governed Athens for a time and later may have helped establish the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, ...

.

Hellenistic age

The military campaigns ofAlexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

spread Greek thought to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, up to the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayas, Himalayan river of South Asia, South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northw ...

. The resulting migration of many Greek speaking populations across these territories provided the impetus for the foundation of several seats of learning, such as those in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, and Pergamum.

Hellenistic science differed from Greek science in at least two respects: first, it benefited from the cross-fertilization of Greek ideas with those that had developed in other non-Hellenic civilizations; secondly, to some extent, it was supported by royal patrons in the kingdoms founded by Alexander's successors. The city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, in particular, became a major center of scientific research in the 3rd century BC. Two institutions established there during the reigns of Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

(367–282 BC) and Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 BC) were the Library

A library is a collection of Book, books, and possibly other Document, materials and Media (communication), media, that is accessible for use by its members and members of allied institutions. Libraries provide physical (hard copies) or electron ...

and the Museum

A museum is an institution dedicated to displaying or Preservation (library and archive), preserving culturally or scientifically significant objects. Many museums have exhibitions of these objects on public display, and some have private colle ...

. Unlike Plato's Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

and Aristotle's Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

, these institutions were officially supported by the Ptolemies, although the extent of patronage could be precarious depending on the policies of the current ruler.

Hellenistic scholars often employed the principles developed in earlier Greek thought in their scientific investigations, such as the application of mathematics to phenomena or the deliberate collection of empirical data. The assessment of Hellenistic science, however, varies widely. At one extreme is the view of English classical scholar Cornford, who believed that "all the most important and original work was done in the three centuries from 600 to 300 BC". At the other end is the view of Italian physicist and mathematician Lucio Russo, who claims that the scientific method was actually born in the 3rd century BC, only to be largely forgotten during the Roman period and not revived again until the Renaissance.

Technology

Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism ( , ) is an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek hand-powered orrery (model of the Solar System). It is the oldest known example of an Analog computer, analogue computer. It could be used to predict astronomy, astronomical ...

(150–100 BC). It is a 37-gear mechanical computer which calculated the motions of the Sun, Moon, and possibly the other five planets known to the ancients. The Antikythera mechanism included lunar and solar eclipses predicted on the basis of astronomical periods believed to have been learned from the Babylonians.; ; The device may have been part of an ancient Greek tradition of complex mechanical technology that was later, at least in part, transmitted to the Byzantine and Islamic worlds, where mechanical devices which were complex, albeit simpler than the Antikythera mechanism, were built during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. Fragments of a geared calendar attached to a sundial, from the fifth or sixth century Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

, have been found; the calendar may have been used to assist in telling time. A geared calendar similar to the Byzantine device was described by the scientist al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (; ; 973after 1050), known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of modern ...

around 1000, and a surviving 13th-century astrolabe also contains a similar clockwork device...

Medicine

An important school of medicine was formed inAlexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

from the late 4th century to the 2nd century BC. Beginning with Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

, medical officials were allowed to cut open and examine cadaver

A cadaver, often known as a corpse, is a Death, dead human body. Cadavers are used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue (biology), tissue to ...

s for the purposes of learning how human bodies operated. The first use of human bodies for anatomical research occurred in the work of Herophilos (335–280 BC) and Erasistratus

Erasistratus (; ; c. 304 – c. 250 BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow physician Herophilus, he founded a school of anatomy in Alexandria, where they carried out anatomical research ...

(c. 304 – c. 250 BC), who gained permission to perform live dissections, or vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal test ...

s, on condemned criminals in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

under the auspices of the Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

.

Herophilos developed a body of anatomical knowledge much more informed by the actual structure of the human body than previous works had been. He also reversed the longstanding notion made by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

that the heart was the "seat of intelligence", arguing for the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

instead. Herophilos also wrote on the distinction between vein

Veins () are blood vessels in the circulatory system of humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are those of the pulmonary and feta ...

s and arteries

An artery () is a blood vessel in humans and most other animals that takes oxygenated blood away from the heart in the systemic circulation to one or more parts of the body. Exceptions that carry deoxygenated blood are the pulmonary arteries in ...

, and made many other accurate observations about the structure of the human body, especially the nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

. Erasistratus differentiated between the function of the sensory and motor nerve

A motor nerve, or efferent nerve, is a nerve that contains exclusively efferent nerve fibers and transmits motor signals from the central nervous system (CNS) to the effector organs (muscles and glands), as opposed to sensory nerves, which transf ...

s, and linked them to the brain. He is credited with one of the first in-depth descriptions of the cerebrum

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfac ...

and cerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

. For their contributions, Herophilos is often called the "father of anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

", while Erasistratus is regarded by some as the "founder of physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

".

Mathematics

Greek mathematics in the Hellenistic period reached a level of sophistication not matched for several centuries afterward, as much of the work represented by scholars active at this time was of a very advanced level. There is also evidence of combining mathematical knowledge with high levels of technical expertise, as found for instance in the construction of massive building projects (e.g., the Syracusia), or inEratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; ; – ) was an Ancient Greek polymath: a Greek mathematics, mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theory, music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of A ...

' (276–195 BC) measurement of the distance between the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

and the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

and the size of the Earth.

Although few in number, Hellenistic mathematicians actively communicated with each other; publication consisted of passing and copying someone's work among colleagues. Among the most recognizable is the work of Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

(325–265 BC), who presumably authored a series of books known as the '' Elements'', a canon of geometry and elementary number theory for many centuries. Euclid's ''Elements'' served as the main textbook for the teaching of theoretical mathematics until the early 20th century.

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

(287–212 BC), a Sicilian Greek, wrote about a dozen treatises where he communicated many remarkable results, such as the sum of an infinite geometric series in ''Quadrature of the Parabola

''Quadrature of the Parabola'' () is a treatise on geometry, written by Archimedes in the 3rd century BC and addressed to his Alexandrian acquaintance Dositheus. It contains 24 propositions regarding parabolas, culminating in two proofs showing t ...

'', an approximation to the value π in '' Measurement of the Circle'', and a nomenclature to express very large numbers in the '' Sand Reckoner''.

The most characteristic product of Greek mathematics may be the theory of conic section

A conic section, conic or a quadratic curve is a curve obtained from a cone's surface intersecting a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a special case of the ellipse, tho ...

s, which was largely developed in the Hellenistic period, primarily by Apollonius

Apollonius () is a masculine given name which may refer to:

People Ancient world Artists

* Apollonius of Athens (sculptor) (fl. 1st century BC)

* Apollonius of Tralles (fl. 2nd century BC), sculptor

* Apollonius (satyr sculptor)

* Apo ...

(262–190 BC). The methods used made no explicit use of algebra, nor trigonometry, the latter appearing around the time of Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; , ; BC) was a Ancient Greek astronomy, Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. Hippar ...

(190–120 BC).

Astronomy

Advances in mathematical astronomy also took place during the Hellenistic age.Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; , ; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the universe, with the Earth revolving around the Sun once a year and rotati ...

(310–230 BC) was an ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

and mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

at the center of the known universe, with the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

revolving around the Sun once a year and rotating about its axis once a day. Aristarchus also estimated the sizes of the Sun and Moon as compared to Earth's size, and the distances to the Sun and Moon. His heliocentric model did not find many adherents in antiquity but did influence some early modern astronomers, such as Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, who was aware of the heliocentric theory of Aristarchus.

In the 2nd century BC, Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; , ; BC) was a Ancient Greek astronomy, Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. Hippar ...

discovered precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In o ...

, calculated the size and distance of the Moon and invented the earliest known astronomical devices such as the astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

. Hipparchus also created a comprehensive catalog of 1020 stars, and most of the constellation

A constellation is an area on the celestial sphere in which a group of visible stars forms Asterism (astronomy), a perceived pattern or outline, typically representing an animal, mythological subject, or inanimate object.

The first constellati ...

s of the northern hemisphere derive from Greek astronomy

Ancient Greek astronomy is the astronomy written in the Greek language during classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek, Hellenistic period, Hellenistic, Roman Empire, Greco-Roman, and Late an ...

. It has recently been claimed that a celestial globe based on Hipparchus's star catalog sits atop the broad shoulders of a large 2nd-century Roman statue known as the Farnese Atlas

The Farnese Atlas is a 2nd-century CE Ancient Rome, Roman marble sculpture of Atlas (mythology), Atlas holding up a celestial globe. Probably a copy of an earlier work of the Hellenistic period, it is the oldest extant statue of Atlas (mythology) ...

.

Roman era

Science during the

Science during the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

was concerned with systematizing knowledge gained in the preceding Hellenistic age and the knowledge from the vast areas the Romans had conquered. It was largely the work of authors active in this period that would be passed on uninterrupted to later civilizations.

Even though science continued under Roman rule, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

texts were mainly compilations drawing on earlier Greek work. Advanced scientific research and teaching continued to be carried on in Greek. Such Greek and Hellenistic works as survived were preserved and developed later in the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

and then in the Islamic world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

. Late Roman attempts to translate Greek writings into Latin had limited success (e.g., Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480–524 AD), was a Roman Roman Senate, senator, Roman consul, consul, ''magister officiorum'', polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middl ...

), and direct knowledge of most ancient Greek texts only reached western Europe from the 12th century onwards.

Pliny

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

published the ''Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' () is a Latin work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. Despite the work' ...

'' in 77 AD, one of the most extensive compilations of the natural world which survived into the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. Pliny did not simply list materials and objects but also recorded explanations of phenomena. Thus he is the first to correctly describe the origin of amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

as being the fossilized resin of pine trees. He makes the inference from the observation of trapped insects within some amber samples.

Pliny's work is divided neatly into the organic world of plants and animals, and the realm of inorganic matter, although there are frequent digressions in each section. He is especially interested in not just describing the occurrence of plants, animals and insects, but also their exploitation (or abuse) by man. The description of metals

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. These properties are all associated with having electrons available at the Fermi level, as against no ...

and minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): M ...

is particularly detailed, and valuable as being the most extensive compilation still available from the ancient world. Although much of the work was compiled by judicious use of written sources, Pliny gives an eyewitness account of gold mining in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, where he was stationed as an officer. Pliny is especially significant because he provides full bibliographic details of the earlier authors and their works he uses and consults. Because his encyclopaedia survived the Dark Ages, we know of these lost works, even if the texts themselves have disappeared. The book was one of the first to be printed in 1489, and became a standard reference work for Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

scholars, as well as an inspiration for the development of a scientific and rational approach to the world.

Hero

Hero of Alexandria

Hero of Alexandria (; , , also known as Heron of Alexandria ; probably 1st or 2nd century AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who was active in Alexandria in Egypt during the Roman era. He has been described as the greatest experimental ...

was a Greco-Egyptian mathematician and engineer who is often considered to be the greatest experimenter of antiquity. Among his most famous inventions was a windwheel, constituting the earliest instance of wind harnessing on land, and a well-recognized description of a steam-powered device called an aeolipile, which was the first-recorded steam engine.

Galen

The greatest medical practitioner and philosopher of this era wasGalen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

, active in the 2nd century AD. Around 100 of his works survive—the most for any ancient Greek author—and fill 22 volumes of modern text. Galen was born in the ancient Greek city of Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; ), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Aeolis. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north s ...

(now in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

), the son of a successful architect who gave him a liberal education. Galen was instructed in all major philosophical schools (Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism and Epicureanism) until his father, moved by a dream of Asclepius

Asclepius (; ''Asklēpiós'' ; ) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of Apollo), Coronis, or Arsinoe (Greek myth), Ars ...

, decided he should study medicine. After his father's death, Galen traveled widely searching for the best doctors in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

, Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, and finally Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

.

Galen compiled much of the knowledge obtained by his predecessors, and furthered the inquiry into the function of organs by performing dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of ...

s and vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal test ...

s on Barbary apes, oxen, pigs, and other animals. In 158 AD, Galen served as chief physician to the gladiators in his native Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; ), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Aeolis. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north s ...

, and was able to study all kinds of wounds without performing any actual human dissection. It was through his experiments, however, that Galen was able to overturn many long-held beliefs, such as the theory that the arteries contained air which carried it to all parts of the body from the heart and the lungs. This belief was based originally on the arteries of dead animals, which appeared to be empty. Galen was able to demonstrate that living arteries contain blood, but his error, which became the established medical orthodoxy for centuries, was to assume that the blood goes back and forth from the heart in an ebb-and-flow motion.

Anatomy was a prominent part of Galen's medical education and was a major source of interest throughout his life. He wrote two great anatomical works, ''On anatomical procedure'' and ''On the uses of the parts of the body of man''. The information in these tracts became the foundation of authority for all medical writers and physicians for the next 1300 years until they were challenged by Vesalius

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), Latinization of names, latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an anatomist and physician who wrote ''De humani corporis fabrica, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric ...

and Harvey in the 16th century.

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 AD), living in or around

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 AD), living in or around Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, carried out a scientific program centered on the writing of about a dozen books on astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

, harmonics

In physics, acoustics, and telecommunications, a harmonic is a sinusoidal wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'' of a periodic signal. The fundamental frequency is also called the ''1st harm ...

, and optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

. Despite their severe style and high technicality, a great deal of them have survived, in some cases the sole remnants of their kind of writing from antiquity. Two major themes that run through Ptolemy's works are mathematical model

A mathematical model is an abstract and concrete, abstract description of a concrete system using mathematics, mathematical concepts and language of mathematics, language. The process of developing a mathematical model is termed ''mathematical m ...

ling of physical phenomena and methods of visual representation of physical reality.

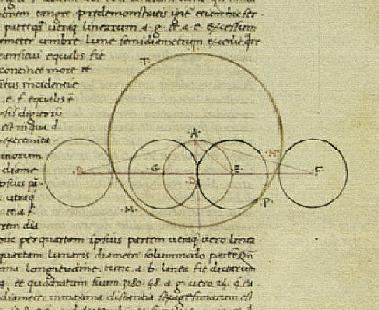

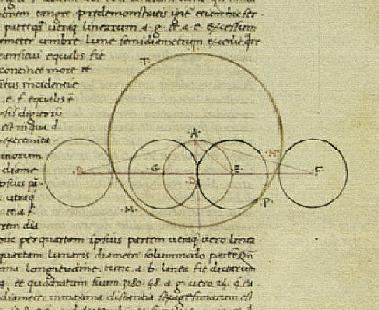

Ptolemy's research program

A research program (British English: research programme) is a professional network of scientists conducting basic research. The term was used by philosopher of science Imre Lakatos to blend and revise the normative model of science offered by K ...

involved a combination of theoretical analysis with empirical considerations seen, for instance, in his systematized study of astronomy. Ptolemy's ''Mathēmatikē Syntaxis'' (), better known as the '' Almagest'', sought to improve on the work of his predecessors by building astronomy not only upon a secure mathematical basis but also by demonstrating the relationship between astronomical observations and the resulting astronomical theory. In his ''Planetary Hypotheses'', Ptolemy describes in detail physical representations of his mathematical models found in the ''Almagest'', presumably for didactic purposes. Likewise, the ''Geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

'' was concerned with the drawing of accurate map

A map is a symbolic depiction of interrelationships, commonly spatial, between things within a space. A map may be annotated with text and graphics. Like any graphic, a map may be fixed to paper or other durable media, or may be displayed on ...

s using astronomical information, at least in principle. Apart from astronomy, both the ''Harmonics'' and the ''Optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

'' contain (in addition to mathematical analyses of sound and sight, respectively) instructions on how to construct and use experimental instruments to corroborate theory.

In retrospect, it is apparent that Ptolemy adjusted some reported measurements to fit his (incorrect) assumption that the angle of refraction

Snell's law (also known as the Snell–Descartes law, the ibn-Sahl law, and the law of refraction) is a formula used to describe the relationship between the angles of incidence and refraction, when referring to light or other waves passing th ...

is proportional to the angle of incidence.

Ptolemy's thoroughness and his preoccupation with ease of data presentation (for example, in his widespread use of tables) virtually guaranteed that earlier work on these subjects be neglected or considered obsolete, to the extent that almost nothing remains of the works Ptolemy often refers. His astronomical work in particular defined the method and subject matter of future research for centuries, and the Ptolemaic system became the dominant model for the motions of the heavens until the seventeenth century.

See also

* Forensics in antiquity *Protoscience

In the philosophy of science, protoscience is a research field that has the characteristics of an undeveloped science that may ultimately develop into an established science. Philosophers use protoscience to understand the history of science and d ...

* Roman technology

Ancient Roman technology is the collection of techniques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the Roman economy, economy and Military of ancient Rome, milit ...

* Obsolete scientific theories

Notes

References

* Alioto, Anthony M. ''A History of Western Science''. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1987. . * Barnes, Jonathan. ''Early Greek Philosophy''. Published by Penguin Classics * Clagett, Marshall. ''Greek Science in Antiquity''. New York: Collier Books, 1955. * Cornford, F. M. Principium Sapientiæ: ''The Origins of Greek Philosophical Thought''. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr, 1952; Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1971. * Lindberg, David C. ''The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450''. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr, 1992. . * Lloyd, G. E. R. ''Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought''. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr, 1968. . * Lloyd, G. E. R. ''Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle''. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1970. . * Lloyd, G. E. R. ''Greek Science after Aristotle''. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1973. . * Lloyd, G. E. R. ''Magic Reason and Experience: Studies in the Origin and Development of Greek Science''. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr, 1979. * Pedersen, Olaf. ''Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction''. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. . * Stahl, William H. ''Roman Science: Origins, Development, and Influence to the Later Middle Ages''. Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr, 1962. * * Thurston, Hugh. ''Early Astronomy''. New York: Springer, 1994. . {{History of scienceClassical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

Ancient Greek science

Ancient Roman science

Classical antiquity