Political Decoy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of status or

The history of politics spans

The history of politics spans

The

The

The study of politics is called political science, It comprises numerous subfields, namely three:

The study of politics is called political science, It comprises numerous subfields, namely three:

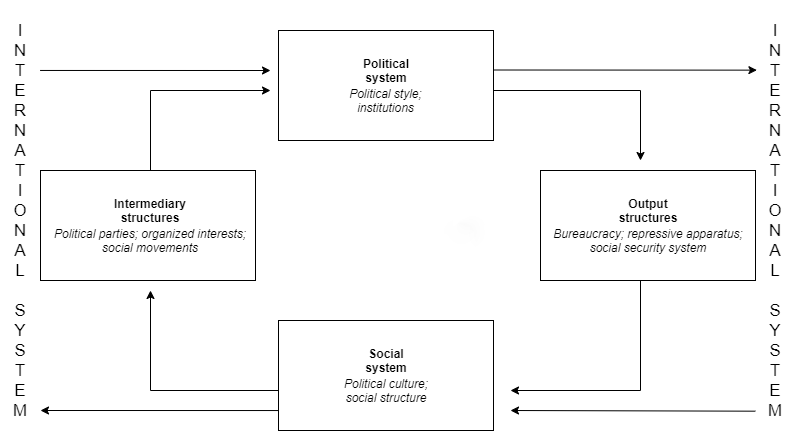

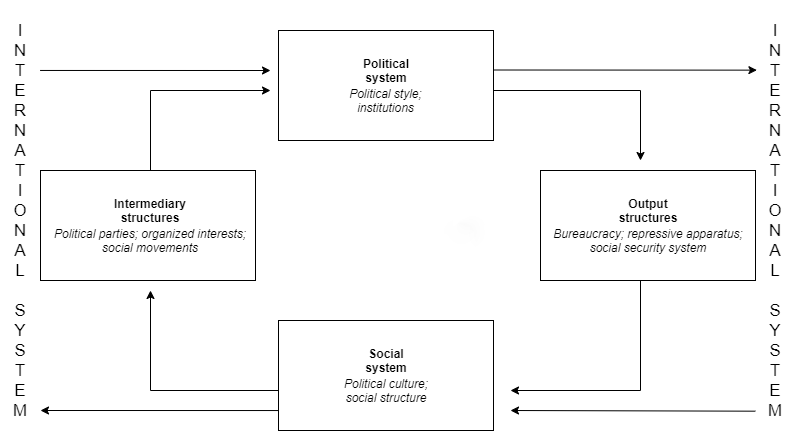

The political system defines the process for making official

The political system defines the process for making official

Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and

Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and

All the above forms of government are variations of the same basic

All the above forms of government are variations of the same basic

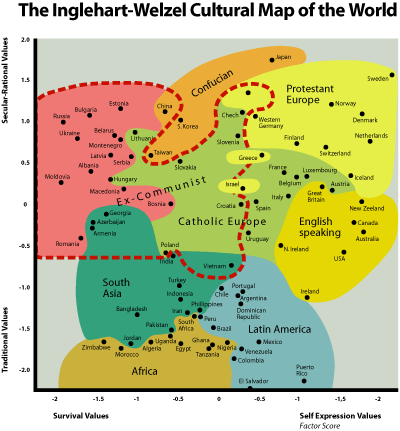

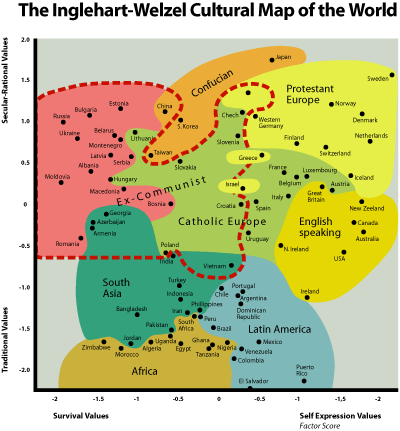

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every

Macropolitics can either describe political issues that affect an entire political system (e.g. the nation state), or refer to interactions between political systems (e.g.

Macropolitics can either describe political issues that affect an entire political system (e.g. the nation state), or refer to interactions between political systems (e.g.

Mesopolitics describes the politics of intermediary structures within a political system, such as Political party, national political parties or Political movement, movements.

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to attain and maintain political power within

Mesopolitics describes the politics of intermediary structures within a political system, such as Political party, national political parties or Political movement, movements.

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to attain and maintain political power within

Equality is a state of affairs in which all people within a specific

Equality is a state of affairs in which all people within a specific

What Is Libertarian?

" ''Institute for Humane Studies''. George Mason University. For anarchist political philosopher L. Susan Brown (1993), "liberalism and

resource

''Resource'' refers to all the materials available in our environment which are Technology, technologically accessible, Economics, economically feasible and Culture, culturally Sustainability, sustainable and help us to satisfy our needs and want ...

s.

The branch of social science

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the ...

that studies politics and government is referred to as political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and Power (social and political), power, and the analysis of political activities, political philosophy, political thought, polit ...

.

Politics may be used positively in the context of a "political solution" which is compromising and non-violent, or descriptively as "the art or science of government", but the word often also carries a negative connotation.. The concept has been defined in various ways, and different approaches have fundamentally differing views on whether it should be used extensively or in a limited way, empirically or normatively, and on whether conflict or co-operation is more essential to it.

A variety of methods are deployed in politics, which include promoting one's own political views among people, negotiation

Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more parties to resolve points of difference, gain an advantage for an individual or Collective bargaining, collective, or craft outcomes to satisfy various interests. The parties aspire to agree on m ...

with other political subjects, making law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

s, and exercising internal and external force

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an Physical object, object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the Magnitu ...

, including warfare

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of State (polity), states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or betwe ...

against adversaries..... Politics is exercised on a wide range of social levels, from clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

and tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

of traditional societies, through modern local government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of governance or public administration within a particular sovereign state.

Local governments typically constitute a subdivision of a higher-level political or administrative unit, such a ...

s, companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether natural, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specifi ...

and institutions up to sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

s, to the international level.

In modern states, people often form political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

to represent their ideas. Members of a party often agree to take the same position on many issues and agree to support the same changes to law and the same leaders. An election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

is usually a competition between different parties.

A political system

In political science, a political system means the form of Political organisation, political organization that can be observed, recognised or otherwise declared by a society or state (polity), state.

It defines the process for making official gov ...

is a framework which defines acceptable political methods within a society. The history of political thought

The history of political thought encompasses the chronology and the substantive and methodological changes of human political thought. The study of the history of political thought represents an intersection of various academic disciplines, su ...

can be traced back to early antiquity, with seminal works such as Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's ''Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

'', Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's ''Politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

'', Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

's political manuscripts and Chanakya

Chanakya (ISO 15919, ISO: ', चाणक्य, ), according to legendary narratives preserved in various traditions dating from the 4th to 11th century CE, was a Brahmin who assisted the first Mauryan emperor Chandragupta Maurya, Chandragup ...

's ''Arthashastra

''Kautilya's Arthashastra'' (, ; ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, politics, economic policy and military strategy. The text is likely the work of several authors over centuries, starting as a compilation of ''Arthashas ...

''.

Etymology

The English word ''politics'' has its roots in the name ofAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's classic work, '' Politiká'', which introduced the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

term ()''.'' In the mid-15th century, Aristotle's composition was rendered in Early Modern English

Early Modern English (sometimes abbreviated EModEFor example, or EMnE) or Early New English (ENE) is the stage of the English language from the beginning of the Tudor period to the English Interregnum and Restoration, or from the transit ...

as ,"The book of " (Bhuler 1961/1941:154). which became ''Politics'' in Modern English

Modern English, sometimes called New English (NE) or present-day English (PDE) as opposed to Middle and Old English, is the form of the English language that has been spoken since the Great Vowel Shift in England

England is a Count ...

.

The singular ''politic'' first attested in English in 1430, coming from Middle French

Middle French () is a historical division of the French language that covers the period from the mid-14th to the early 17th centuries. It is a period of transition during which:

* the French language became clearly distinguished from the other co ...

—itself taking from , a Latinization of the Greek () from () and ().

Definitions

* Harold Lasswell: "who gets what, when, how" * David Easton: "the authoritative allocation of values for a society". *Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

: "the most concentrated expression of economics"

* Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

: "the capacity of always choosing at each instant, in constantly changing situations, the least harmful, the most useful"

* Bernard Crick: "a distinctive form of rule whereby people act together through institutionalized procedures to resolve differences"

* Adrian Leftwich: "comprises all the activities of co-operation, negotiation and conflict within and between societies"

Approaches

There are several ways in which approaching politics has been conceptualized.Extensive and limited

Adrian Leftwich has differentiated views of politics based on how extensive or limited their perception of what accounts as 'political' is. The extensive view sees politics as present across the sphere of human social relations, while the limited view restricts it to certain contexts. For example, in a more restrictive way, politics may be viewed as primarily aboutgovernance

Governance is the overall complex system or framework of Process, processes, functions, structures, Social norm, rules, Law, laws and Norms (sociology), norms born out of the Interpersonal relationship, relationships, Social interaction, intera ...

, while a feminist perspective could argue that sites which have been viewed traditionally as non-political, should indeed be viewed as political as well. This latter position is encapsulated in the slogan "'' the personal is political''", which disputes the distinction between private and public issues. Politics may also be defined by the use of power, as has been argued by Robert A. Dahl.

Moralism and realism

Some perspectives on politics view it empirically as an exercise of power, while others see it as a social function with anormative

Normativity is the phenomenon in human societies of designating some actions or outcomes as good, desirable, or permissible, and others as bad, undesirable, or impermissible. A Norm (philosophy), norm in this sense means a standard for evaluatin ...

basis. This distinction has been called the difference between political ''moralism'' and political ''realism''''.''. For moralists, politics is closely linked to ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, and is at its extreme in utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

n thinking. For example, according to Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (born Johanna Arendt; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a German and American historian and philosopher. She was one of the most influential political theory, political theorists of the twentieth century.

Her work ...

, the view of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

was that, "to be political…meant that everything was decided through words and persuasion and not through violence"; while according to Bernard Crick, "politics is the way in which free societies are governed. Politics is politics, and other forms of rule are something else." In contrast, for realists, represented by those such as Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

, Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

, and Harold Lasswell, politics is based on the use of power, irrespective of the ends being pursued.

Conflict and co-operation

Agonism

Agonism (from Greek 'struggle') is a political and social theory that emphasizes the potentially positive aspects of certain forms of conflict. It accepts a permanent place for such conflict in the political sphere, but seeks to show how indivi ...

argues that politics essentially comes down to conflict between conflicting interests. Political scientist Elmer Schattschneider argued that "at the root of all politics is the universal language of conflict", while for Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, author, and political theorist.

Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. An authoritarian conservative theorist, he was noted as a critic of ...

the essence of politics is the distinction of 'friend' from 'foe'. This is in direct contrast to the more co-operative views of politics by Aristotle and Crick. However, a more mixed view between these extremes is provided by Irish political scientist Michael Laver, who noted that:Politics is about the characteristic blend of conflict and co-operation that can be found so often in human interactions. Pure conflict is war. Pure co-operation is true love. Politics is a mixture of both.

History

The history of politics spans

The history of politics spans human history

Human history or world history is the record of humankind from prehistory to the present. Early modern human, Modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago and initially lived as hunter-gatherers. They Early expansions of hominin ...

and is not limited to modern institutions of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

.

Prehistoric

Frans de Waal argued thatchimpanzee

The chimpanzee (; ''Pan troglodytes''), also simply known as the chimp, is a species of Hominidae, great ape native to the forests and savannahs of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed one. When its close rel ...

s engage in politics through "social manipulation to secure and maintain influential positions". Early human forms of social organization—bands and tribes—lacked centralized political structures. These are sometimes referred to as stateless societies

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority. Most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power, and they are generally not perman ...

.

Early states

In ancient history, civilizations did not have definite boundaries asstate

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

s have today, and their borders could be more accurately described as frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

s. Early dynastic Sumer, and early dynastic Egypt were the first civilizations to define their border

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

s. Moreover, up to the 12th century, many people lived in non-state societies. These range from relatively egalitarian bands and tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

s to complex and highly stratified chiefdom

A chiefdom is a political organization of people representation (politics), represented or government, governed by a tribal chief, chief. Chiefdoms have been discussed, depending on their scope, as a stateless society, stateless, state (polity) ...

s.

State formation

There are a number of different theories and hypotheses regarding early state formation that seek generalizations to explain why the state developed in some places but not others. Other scholars believe that generalizations are unhelpful and that each case of early state formation should be treated on its own. Voluntary theories contend that diverse groups of people came together to form states as a result of some shared rational interest.. The theories largely focus on the development of agriculture, and the population and organizational pressure that followed and resulted in state formation. One of the most prominent theories of early and primary state formation is the ''hydraulic hypothesis'', which contends that the state was a result of the need to build and maintain large-scale irrigation projects. Conflict theories of state formation regard conflict and dominance of some population over another population as key to the formation of states. In contrast with voluntary theories, these arguments believe that people do not voluntarily agree to create a state to maximize benefits, but that states form due to some form of oppression by one group over others. Some theories in turn argue that warfare was critical for state formation.Ancient history

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from theUruk period

The Uruk period (; also known as Protoliterate period) existed from the protohistory, protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named after the S ...

and Predynastic Egypt respectively around approximately 3000 BC.. Early dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

in the north-east of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases existed. Early dynastic Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

was located in southern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, with its borders extending from the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

to parts of the Euphrates

The Euphrates ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of West Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia (). Originati ...

and Tigris

The Tigris ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the eastern of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian Desert, Syrian and Arabia ...

rivers.

Egyptians, Romans, and the Greeks were the first people known to have explicitly formulated a political philosophy of the state, and to have rationally analyzed political institutions. Prior to this, states were described and justified in terms of religious myths.

Several important political innovations of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

came from the Greek city-states (''polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

'') and the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

. The Greek city-states before the 4th century granted citizenship

Citizenship is a membership and allegiance to a sovereign state.

Though citizenship is often conflated with nationality in today's English-speaking world, international law does not usually use the term ''citizenship'' to refer to nationalit ...

rights to their free population; in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

these rights were combined with a directly democratic form of government that was to have a long afterlife in political thought and history.

Modern states

The

The Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy Roman Empire ...

(1648) is considered by political scientists

The following is a list of notable political scientists. Political science is the scientific study of politics, a social science dealing with systems of governance and power.

A

* Robert Abelson – Yale University psychologist and political ...

to be the beginning of the modern international system,.. in which external powers should avoid interfering in another country's domestic affairs.. The principle of non-interference in other countries' domestic affairs was laid out in the mid-18th century by Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel

Emmerich de Vattel ( 25 April 171428 December 1767) was a philosopher, diplomat, and jurist.

Vattel's work profoundly influenced the development of international law. He is most famous for his 1758 work ''The Law of Nations''. This work was his ...

. States became the primary institutional agents in an interstate system of relations. The Peace of Westphalia is said to have ended attempts to impose supranational authority on European states. The "Westphalian" doctrine of states as independent agents was bolstered by the rise in 19th century thought of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

, under which legitimate states were assumed to correspond to ''nations

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, territory, or societ ...

''—groups of people united by language and culture.

In Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, during the 18th century, the classic non-national states were the multinational empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

s: the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

, Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, and the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. Such empires also existed in Asia, Africa, and the Americas; in the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

, immediately after the death of Muhammad in 632, Caliphate

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

s were established, which developed into multi-ethnic transnational empires. The multinational empire was an absolute monarchy ruled by a king, emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

or sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

. The population belonged to many ethnic groups, and they spoke many languages. The empire was dominated by one ethnic group, and their language was usually the language of public administration. The ruling dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchy, monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

H ...

was usually, but not always, from that group. Some of the smaller European states were not so ethnically diverse, but were also dynastic states, ruled by a royal house

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchy, monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

H ...

. A few of the smaller states survived, such as the independent principalities of Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (, ; ; ), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein ( ), is a Landlocked country#Doubly landlocked, doubly landlocked Swiss Standard German, German-speaking microstate in the Central European Alps, between Austria in the east ...

, Andorra

Andorra, officially the Principality of Andorra, is a Sovereignty, sovereign landlocked country on the Iberian Peninsula, in the eastern Pyrenees in Southwestern Europe, Andorra–France border, bordered by France to the north and Spain to A ...

, Monaco

Monaco, officially the Principality of Monaco, is a Sovereign state, sovereign city-state and European microstates, microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria, in Western Europe, ...

, and the republic of San Marino

San Marino, officially the Republic of San Marino, is a landlocked country in Southern Europe, completely surrounded by Italy. Located on the northeastern slopes of the Apennine Mountains, it is the larger of two European microstates, microsta ...

.

Most theories see the nation state as a 19th-century European phenomenon, facilitated by developments such as state-mandated education, mass literacy

Literacy is the ability to read and write, while illiteracy refers to an inability to read and write. Some researchers suggest that the study of "literacy" as a concept can be divided into two periods: the period before 1950, when literacy was ...

, and mass media

Mass media include the diverse arrays of media that reach a large audience via mass communication.

Broadcast media transmit information electronically via media such as films, radio, recorded music, or television. Digital media comprises b ...

. However, historians also note the early emergence of a relatively unified state and identity in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

. Scholars such as Steven Weber, David Woodward, Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault ( , ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French History of ideas, historian of ideas and Philosophy, philosopher who was also an author, Literary criticism, literary critic, Activism, political activist, and teacher. Fo ...

, and Jeremy Black have advanced the hypothesis that the nation state did not arise out of political ingenuity or an unknown undetermined source, nor was it an accident of history or political invention. Rather, the nation state is an inadvertent byproduct of 15th-century intellectual discoveries in political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

, capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

, mercantilism

Mercantilism is a economic nationalism, nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources ...

, political geography, and geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

combined with cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

and advances in map-making technologies.

Some nation states, such as Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, came into existence at least partly as a result of political campaigns by nationalists, during the 19th century. In both cases, the territory was previously divided among other states, some of them very small. Liberal ideas of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

played a role in German unification, which was preceded by a customs union, the Zollverein. National self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

was a key aspect of United States President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

, leading to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

after the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, while the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

became the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

after the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. Decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

lead to the creation of new nation states in place of multinational empires in the Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

.

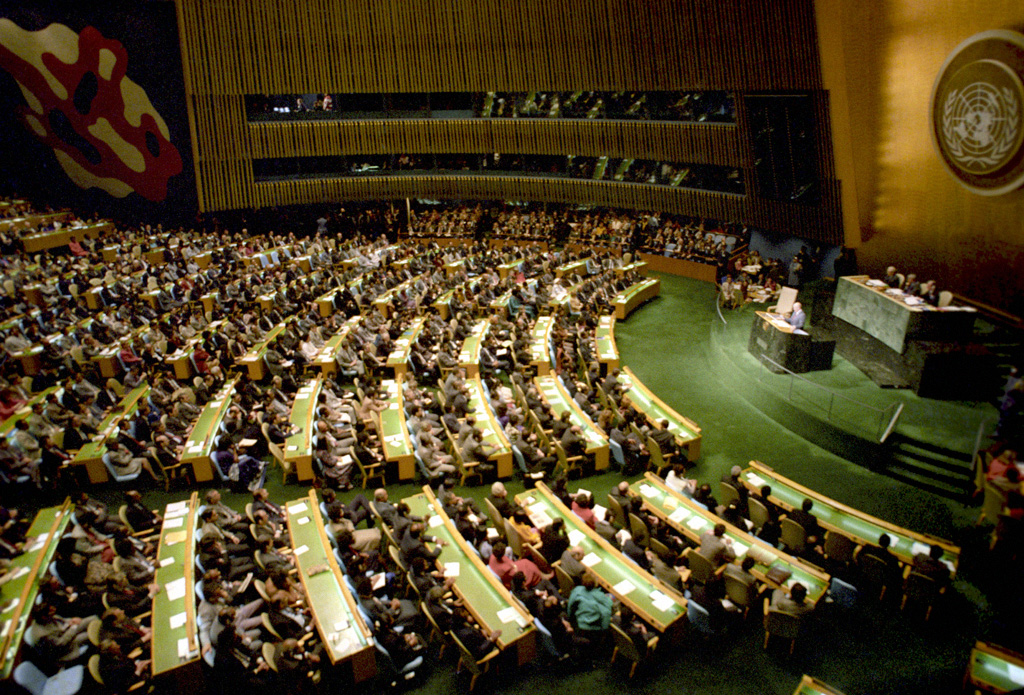

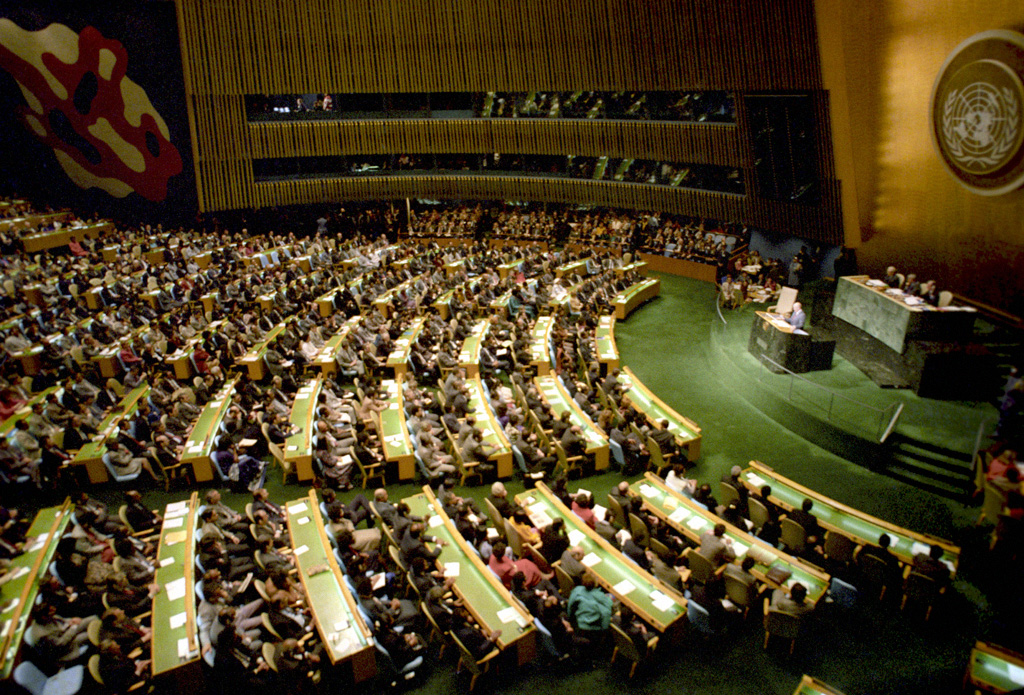

Globalization

Political globalization began in the 20th century throughintergovernmental organization

Globalization is social change associated with increased connectivity among societies and their elements and the explosive evolution of transportation and telecommunication technologies to facilitate international cultural and economic exchange. ...

s and supranational union

A supranational union is a type of international organization and political union that is empowered to directly exercise some of the powers and functions otherwise reserved to State (polity), states. A supranational organization involves a g ...

s. The League of Nations was founded after World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

it was replaced by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

. Various international treaties have been signed through it. Regional integration has been pursued by the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

, ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations,

commonly abbreviated as ASEAN, is a regional grouping of 10 states in Southeast Asia "that aims to promote economic and security cooperation among its ten members." Together, its member states r ...

, the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

, and Mercosur. International political institutions on the international level include the International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an intergovernmental organization and International court, international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute ...

, the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

, and the World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland that regulates and facilitates international trade. Governments use the organization to establish, revise, and enforce the rules that g ...

.

Political science

The study of politics is called political science, It comprises numerous subfields, namely three:

The study of politics is called political science, It comprises numerous subfields, namely three: Comparative politics

Comparative politics is a field in political science characterized either by the use of the '' comparative method'' or other empirical methods to explore politics both within and between countries. Substantively, this can include questions relat ...

, international relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

and political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

. Political science is related to, and draws upon, the fields of economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

, sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

, history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, psychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of deleterious mental disorder, mental conditions. These include matters related to cognition, perceptions, Mood (psychology), mood, emotion, and behavior.

...

, anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, and neurosciences.

Comparative politics

Comparative politics is a field in political science characterized either by the use of the '' comparative method'' or other empirical methods to explore politics both within and between countries. Substantively, this can include questions relat ...

is the science of comparison and teaching of different types of constitutions, political actors, legislature and associated fields. International relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

deals with the interaction between nation-state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) con ...

s as well as intergovernmental and transnational organizations. Political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

is more concerned with contributions of various classical and contemporary thinkers and philosophers.

Political science is methodologically diverse and appropriates many methods originating in psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, social research

Social research is research conducted by social scientists following a systematic plan. Social research methodologies can be classified as quantitative and qualitative.

* Quantitative designs approach social phenomena through quantifiable ...

, and cognitive neuroscience

Cognitive neuroscience is the scientific field that is concerned with the study of the Biology, biological processes and aspects that underlie cognition, with a specific focus on the neural connections in the brain which are involved in mental ...

. Approaches include positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

, interpretivism, rational choice theory

Rational choice modeling refers to the use of decision theory (the theory of rational choice) as a set of guidelines to help understand economic and social behavior. The theory tries to approximate, predict, or mathematically model human behav ...

, behavioralism, structuralism

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns t ...

, post-structuralism

Post-structuralism is a philosophical movement that questions the objectivity or stability of the various interpretive structures that are posited by structuralism and considers them to be constituted by broader systems of Power (social and poli ...

, realism, institutionalism, and pluralism. Political science, as one of the social science

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the ...

s, uses methods and techniques that relate to the kinds of inquiries sought: primary sources such as historical documents and official records, secondary sources such as scholarly journal articles, survey research, statistical analysis

Statistical inference is the process of using data analysis to infer properties of an underlying probability distribution.Upton, G., Cook, I. (2008) ''Oxford Dictionary of Statistics'', OUP. . Inferential statistical analysis infers properties of ...

, case studies

A case study is an in-depth, detailed examination of a particular case (or cases) within a real-world context. For example, case studies in medicine may focus on an individual patient or ailment; case studies in business might cover a particular fi ...

, experimental research, and model building.

Political system

The political system defines the process for making official

The political system defines the process for making official government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

decisions. It is usually compared to the legal system

A legal system is a set of legal norms and institutions and processes by which those norms are applied, often within a particular jurisdiction or community. It may also be referred to as a legal order. The comparative study of legal systems is th ...

, economic system

An economic system, or economic order, is a system of production, resource allocation and distribution of goods and services within an economy. It includes the combination of the various institutions, agencies, entities, decision-making proces ...

, cultural system, and other social system

In sociology, a social system is the patterned network of relationships constituting a coherent whole that exist between individuals, groups, and institutions. It is the formal Social structure, structure of role and status that can form in a smal ...

s. According to David Easton, "A political system can be designated as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated for a society." Each political system is embedded in a society with its own political culture, and they in turn shape their societies through public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a Group decision-making, decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to Problem solving, solve or address relevant and problematic social issues, guided by a conceptio ...

. The interactions between different political systems are the basis for global politics

Global politics, also known as world politics, names both the discipline that studies the political and economic patterns of the world and the field that is being studied. At the centre of that field are the different processes of political global ...

.

Forms of government

Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and

Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

s (usually presidential, semi-presidential

A semi-presidential republic, or dual executive republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamen ...

, or parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

).

The separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

describes the degree of horizontal integration between the legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

, the executive, the judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, and other independent institutions.

Source of power

The source of power determines the difference betweendemocracies

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

, oligarchies

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or thr ...

, and autocracies

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with democracy and feudalism. ...

.

In a democracy, political legitimacy is based on popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

. Forms of democracy include representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies func ...

, direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate directly decides on policy initiatives, without legislator, elected representatives as proxies, as opposed to the representative democracy m ...

, and demarchy

In governance, sortition is the selection of public officer, officials or jurors at random, i.e. by Lottery (probability), lottery, in order to obtain a representative sample.

In ancient Athenian democracy, sortition was the traditional and pr ...

. These are separated by the way decisions are made, whether by elected representatives, referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

s, or by citizen juries. Democracies can be either republics or constitutional monarchies.

Oligarchy is a power structure where a minority rules. These may be in the form of anocracy

Anocracy, or semi-democracy, is a form of government that is loosely defined as part democracy and part dictatorship, or as a "regime that mixes democratic with autocratic features". Another definition classifies anocracy as "a regime that permi ...

, aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

, ergatocracy, geniocracy, gerontocracy, kakistocracy, kleptocracy

Kleptocracy (from Greek , "thief", or , "I steal", and from , "power, rule"), also referred to as thievocracy, is a government whose corrupt leaders (kleptocrats) use political power to expropriate the wealth of the people and land the ...

, meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods or political power are vested in individual people based on ability and talent, rather than ...

, noocracy, particracy, plutocracy

A plutocracy () or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. The first known use of the term in English dates from 1631. Unlike most political systems, plutocracy is not rooted in any established ...

, stratocracy, technocracy

Technocracy is a form of government in which decision-makers appoint knowledge experts in specific domains to provide them with advice and guidance in various areas of their policy-making responsibilities. Technocracy follows largely in the tra ...

, theocracy

Theocracy is a form of autocracy or oligarchy in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries, with executive and legislative power, who manage the government's ...

, or timocracy.

Autocracies are either dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no Limited government, limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, ...

s (including military dictatorship

A military dictatorship, or a military regime, is a type of dictatorship in which Power (social and political), power is held by one or more military officers. Military dictatorships are led by either a single military dictator, known as a Polit ...

s) or absolute monarchies.

Vertical integration

In terms of level of vertical integration, political systems can be divided into (from least to most integrated)confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

s, federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

s, and unitary state

A unitary state is a (Sovereign state, sovereign) State (polity), state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create or abolish administrative divisions (sub-national or ...

s.

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

(federalism

Federalism is a mode of government that combines a general level of government (a central or federal government) with a regional level of sub-unit governments (e.g., provinces, State (sub-national), states, Canton (administrative division), ca ...

). In a federation, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, is typically constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party, the states or the federal political body. Federations were formed first in Switzerland, then in the United States in 1776, in Canada in 1867 and in Germany in 1871 and in 1901, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. Compared to a federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

, a confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

has less centralized power.

State

polity

A polity is a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of political Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources.

A polity can be any group of people org ...

, the sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

. The state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

has been defined by Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

as a political entity that has monopoly on violence

In political philosophy, a monopoly on violence or monopoly on the legal use of force is the property of a polity that is the only entity in its jurisdiction to legitimately use force, and thus the supreme authority of that area.

While the mon ...

within its territory, while the Montevideo Convention

The Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States is a treaty signed at Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 26, 1933, during the Seventh International Conference of American States. At the conference, United States President Franklin D. R ...

holds that states need to have a defined territory; a permanent population; a government; and a capacity to enter into international relations.

A stateless society is a society

A society () is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. ...

that is not governed by a state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

.. In stateless societies, there is little concentration

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', '' molar concentration'', '' number concentration'', ...

of authority

Authority is commonly understood as the legitimate power of a person or group of other people.

In a civil state, ''authority'' may be practiced by legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government,''The New Fontana Dictionary of M ...

; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through predefined rules tend to be small. Stateless societies are highly variable in economic organization and cultural practices.

While stateless societies were the norm in human prehistory, few stateless societies exist today; almost the entire global population resides within the jurisdiction of a sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

. In some regions nominal state authorities may be very weak and wield little or no actual power. Over the course of history most stateless peoples have been integrated into the state-based societies around them.

Some political philosophies consider the state undesirable, and thus consider the formation of a stateless society a goal to be achieved. A central tenet of anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

is the advocacy of society without states. The type of society sought for varies significantly between anarchist schools of thought

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state ...

, ranging from extreme individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

to complete collectivism. In Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, Marx's theory of the state considers that in a post-capitalist society the state, an undesirable institution, would be unnecessary and Withering away of the state, wither away. A related concept is that of stateless communism, a phrase sometimes used to describe Marx's anticipated post-capitalist society.

Constitutions

Constitutions are written documents that specify and limit the powers of the different branches of government. Although a constitution is a written document, there is also an unwritten constitution. The unwritten constitution is continually being written by the legislative and judiciary branch of government; this is just one of those cases in which the nature of the circumstances determines the form of government that is most appropriate. England did set the fashion of written constitutions during the English Civil War, Civil War but after the Restoration (England), Restoration abandoned them to be taken up later by the Thirteen Colonies, American Colonies after their American Revolution, emancipation and then France after the French Revolution, Revolution and the rest of Europe including the European colonies. Constitutions often set outseparation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

, dividing the government into the executive, the legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

, and the judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

(together referred to as the trias politica), in order to achieve checks and balances within the state. Additional independent branches may also be created, including civil service commissions, election commissions, and supreme audit institutions.

Political culture

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every political system

In political science, a political system means the form of Political organisation, political organization that can be observed, recognised or otherwise declared by a society or state (polity), state.

It defines the process for making official gov ...

is embedded in a particular political culture. Lucian Pye's definition is that, "Political culture is the set of attitudes, beliefs, and sentiments, which give order and meaning to a political process and which provide the underlying assumptions and rules that govern behavior in the political system."

Trust (social science), Trust is a major factor in political culture, as its level determines the capacity of the state to function.. Postmaterialism is the degree to which a political culture is concerned with issues which are not of immediate physical or material concern, such as human rights and environmentalism. Religion has also an impact on political culture.

Political dysfunction

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of powers for illegitimate private gain, conducted by government officials or their network contacts. Forms of political corruption include bribery, cronyism, nepotism, and Patronage, political patronage. Forms of political patronage, in turn, includes clientelism, Earmark (politics), earmarking, pork barreling, slush funds, and spoils systems; as well as political machines, which is a political system that operates for corrupt ends. When corruption is embedded in political culture, this may be referred to as patrimonialism or neopatrimonialism. A form of government that is built on corruption is called a ''kleptocracy

Kleptocracy (from Greek , "thief", or , "I steal", and from , "power, rule"), also referred to as thievocracy, is a government whose corrupt leaders (kleptocrats) use political power to expropriate the wealth of the people and land the ...

'' ('rule of thieves').

Insincere politics

The words "politics" and "political" are sometimes used as pejoratives to mean political action that is deemed to be overzealous, performative, or insincere.Levels of politics

Macropolitics

Macropolitics can either describe political issues that affect an entire political system (e.g. the nation state), or refer to interactions between political systems (e.g.

Macropolitics can either describe political issues that affect an entire political system (e.g. the nation state), or refer to interactions between political systems (e.g. international relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

).

Global politics (or world politics) covers all aspects of politics that affect multiple political systems, in practice meaning any political phenomenon crossing national borders. This can include City, cities, nation-states, multinational corporations, non-governmental organizations or international organizations. An important element is international relations: the relations between nation-states may be peaceful when they are conducted through diplomacy, or they may be violent, which is described as war. States that are able to exert strong international influence are referred to as superpowers, whereas less-powerful ones may be called Regional power, regional or middle powers. The international system of Power (international relations), power is called the ''world order'', which is affected by the Balance of power (international relations), balance of power that defines the degree of Polarity (international relations), polarity in the system. Emerging powers are potentially destabilizing to it, especially if they display revanchism or irredentism.

Politics inside the limits of political systems, which in contemporary context correspond to national border

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

s, are referred to as domestic politics. This includes most forms of public policy