Point Barrow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Point Barrow or Nuvuk is a headland on the Arctic coast in the

Archaeological evidence indicates that Point Barrow was occupied by the ancestors of the

Archaeological evidence indicates that Point Barrow was occupied by the ancestors of the  On August 15, 1935, an airplane crash killed aviator

On August 15, 1935, an airplane crash killed aviator

Rocket launches at Point Barrow

The papers of Henry W. Greist on Point Barrow

at Dartmouth College Library {{Authority control Barrow, Point Landforms of North Slope Borough, Alaska

U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, northeast of Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow). It is the northernmost point of all the territory of the United States, at , south of the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

. (The northernmost point on the North American mainland, Murchison Promontory in Canada, is farther north.)

Geography

Point Barrow is an important geographical landmark, marking the limit between two marginal seas of theArctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

, the Chukchi Sea

The Chukchi Sea (, ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Long Strait, off Wrangel Island, and in the east by Point Barrow, Alaska, ...

to the west and the Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea ( ; ) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Alaska, and west of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The sea is named after Sir Francis Beaufort, a Hydrography, hydrographer. T ...

to the east.

History

Archaeological evidence indicates that Point Barrow was occupied by the ancestors of the

Archaeological evidence indicates that Point Barrow was occupied by the ancestors of the Iñupiat

The Inupiat (singular: Iñupiaq), also known as Alaskan Inuit, are a group of Alaska Natives whose traditional territory roughly spans northeast from Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the northernmost part of the Canada–United States borde ...

for almost 1,000 years prior to the arrival of the first Europeans. Occupation continued into the 1940s. The headland is an important archaeological site, yielding burials and artifacts associated with the Thule culture, including uluit and bola. The waters off Point Barrow are on the bowhead whale

The bowhead whale (''Balaena mysticetus''), sometimes called the Greenland right whale, Arctic whale, and polar whale, is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and is the only living representative of the genus '' Balaena' ...

migration route and it is surmised, that the site was chosen to make hunting easier. There are also burial mounds

A tumulus (: tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, mounds, howes, or in Siberia and Central Asia as ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. ...

in the area, at the nearby Birnirk site, associated with the earlier Birnirk culture, a pre-Thule culture first identified in 1912 by Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was an Arctic explorer and ethnologist. He was born in Manitoba, Canada.

Early life and education

Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Arnes, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. ...

while excavating in the area. The settlement was called Nuvuk, and it was near the "migration path of bowhead whales which would become the cultural and nutritional centre of Nuvuk life."

Point Barrow was named in 1826 by English explorer Frederick William Beechey

Rear-Admiral Frederick William Beechey (17 February 1796 – 29 November 1856) was an English naval officer, artist, explorer, hydrographer and writer.

Life and career

He was the son of two painters, Sir William Beechey, RA and his sec ...

for Sir John Barrow

Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1764 – 23 November 1848) was an English geographer, linguist, writer and civil servant best known for serving as the Second Secretary to the Admiralty from 1804 until 1845.

Early life

Barrow was b ...

, a statesman and geographer of the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of the Government of the United Kingdom that was responsible for the command of the Royal Navy.

Historically, its titular head was the Lord High Admiral of the ...

. The water around it is normally ice-free for two or three months a year, but this was not the experience of the early explorers. Beechey could not reach it by ship and had to send a ship's boat ahead.

In 1826, John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer and colonial administrator. After serving in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, he led two expeditions into the Northern Canada, Canadia ...

tried to reach it from the east, but was blocked by ice.

In 1837, Thomas Simpson walked 50 miles west to Point Barrow after his boats were stopped by ice.

In 1849, William Pullen rounded it in two whale boats after sending two larger boats back west because of the ice.

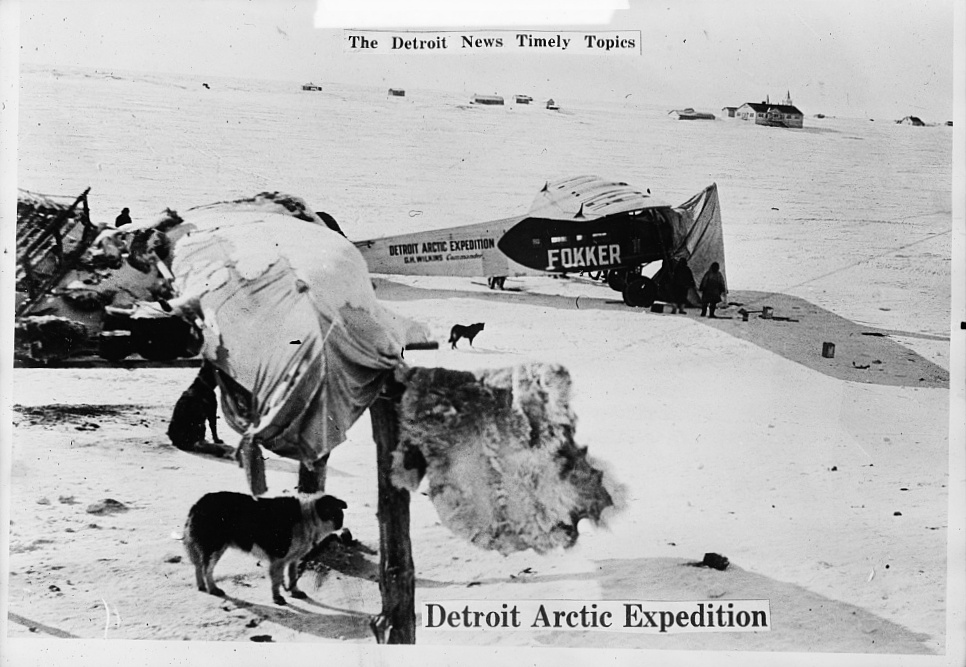

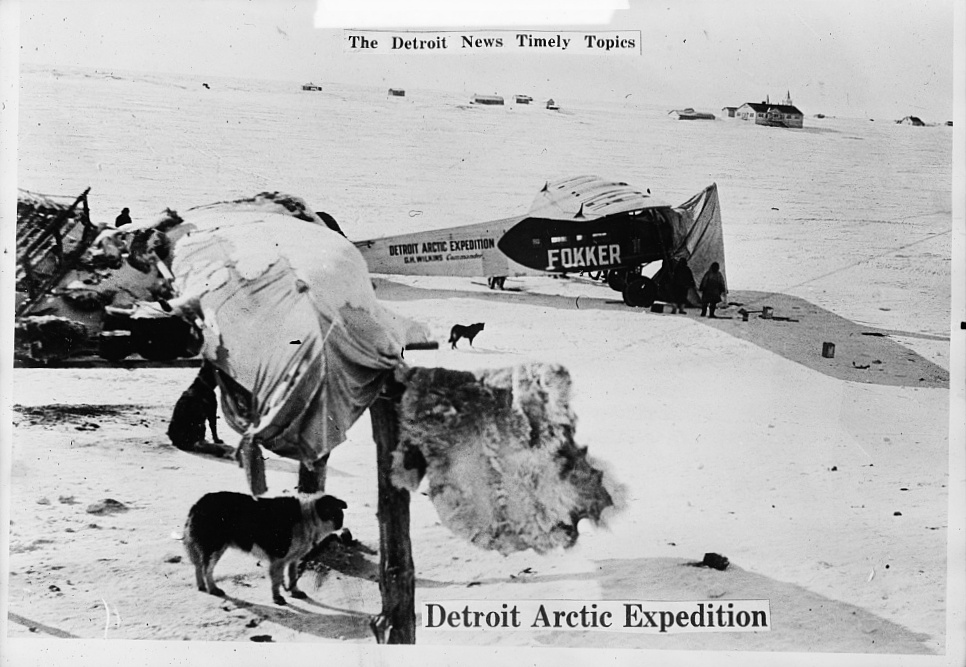

Point Barrow has been a jumping-off point for many Arctic expeditions

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway (Nordland, Troms, Finnmar ...

, including the 1926 Wilkins Detroit Arctic Expedition and the April 15, 1928, Eielson– Wilkins flight across the Arctic Ocean to Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

.

On August 15, 1935, an airplane crash killed aviator

On August 15, 1935, an airplane crash killed aviator Wiley Post

Wiley Hardeman Post (November 22, 1898 – August 15, 1935) was an American aviator during the Aviation between the World Wars, interwar period and the first aviator, pilot to fly solo around the world. Known for his work in high-altitude flyi ...

and his passenger, the entertainer Will Rogers

William Penn Adair Rogers (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) was an American vaudeville performer, actor, and humorous social commentator. He was born as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, in the Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma ...

, at the Rogers–Post Site, 33 km (20.5 mi) southwest of Point Barrow.

In 1946, William C. Trimble of the State Department discussed an alternate offer of land in Point Barrow, as part of a $100 million in gold bullion offer to Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

to purchase Greenland. Had the Alaska trade occurred, from 1967 Denmark would have benefited from Prudhoe Bay Oil Field

Prudhoe Bay Oil Field is a large oil field on Alaska's North Slope. It is the largest oil field in North America, covering and originally contained approximately of oil.

, the richest petroleum discovery in American history.

In 1988, gray whale

The gray whale (''Eschrichtius robustus''), also known as the grey whale,Britannica Micro.: v. IV, p. 693. is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and breeding grounds yearly. It reaches a length of , a weight of up to and lives between ...

s were trapped in the ice at Point Barrow, which attracted attention from the public worldwide. The Iñupiat do not hunt gray whales and joined in rescue operation '' Operation Breakthrough'', which also involved Soviet icebreakers.

Demographics

Point Barrow first appeared in the 1880 U.S. census as the unincorporated Inuit village of "Kokmullit" (AKA Nuwuk). All 200 residents were Inuit. In 1890, it returned as Point Barrow, which also included the Refuge & Whaling Station and native settlements of Nuwuk, Ongovehenok and winter village on "Kugaru" (Inaru) River. It reported 152 residents, of which 143 were Native American, eight were "other race" and one was white. It did not report in 1900, but appeared again from 1910-1940. It has not reported separately since. Barrow, a city of 5,000, changed its name to Utqiagvik, its Inupiaq name, on December 1, 2016.See also

*Alaska North Slope

The Alaska North Slope is the region of the U.S. state of Alaska located on the northern slope of the Brooks Range along the coast of two marginal seas of the Arctic Ocean, the Chukchi Sea being on the western side of Point Barrow, and the Beau ...

* Iḷisaġvik College

* Umiak

The umiak, umialak, umiaq, umiac, oomiac, oomiak, ongiuk, or anyak is a type of open skin boat, used by the Yupik peoples, Yupik and Inuit, and was originally found in all coastal areas from Siberia to Greenland. First used in Thule people, Thule ...

References

External links

Rocket launches at Point Barrow

The papers of Henry W. Greist on Point Barrow

at Dartmouth College Library {{Authority control Barrow, Point Landforms of North Slope Borough, Alaska