Pharsalia Pulchroides on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''De Bello Civili'' (; ''On the Civil War''), more commonly referred to as the ''Pharsalia'' (, neuter plural), is a

Lucan breaks from epic tradition by minimizing, and in certain cases, completely ignoring (and some argue, denying) the existence of the traditional Roman deities. This is in marked contrast to his predecessors, Virgil and Ovid, who used anthropomorphized gods and goddesses as major players in their works. According to Susanna Braund, by choosing to not focus on the gods, Lucan emphasizes and underscores the human role in the atrocities of the Roman civil war.Braund (2009), pp. xxiiixxiv. James Duff, on the other hand, argues that " ucanwas dealing with Roman history and with fairly recent events; and the introduction of the gods as actors must have been grotesque".

This, however, is not to say that the ''Pharsalia'' is devoid of any supernatural phenomenon; in fact, quite the opposite is true, and Braund argues that "the supernatural in all its manifestations played a highly significant part in the structuring of the epic". Braund sees the supernatural as falling into two categories: "dreams and visions" and "portents, prophecies, and consultations of supernatural powers".Braund (1992), p. xxv. In regards to the first category, the poem features four explicit and important dream and vision sequences: Caesar's vision of Roma as he is about to cross the Rubicon, the ghost of Julia appearing to Pompey, Pompey's dream of his happy past, and Caesar and his troops' dream of battle and destruction. All four of these dream-visions are placed strategically throughout the poem, "to provide balance and contrast". In regards to the second category, Lucan describes a number of portents, two oracular episodes, and Erichtho's necromantic rite.Braund (1992), p. xxviii. This manifestation of the supernatural is more public, and serves many purposes, including to reflect "Rome's turmoil on the supernatural plane", as well as simply to "contribute to the atmosphere of sinster foreboding" by describing disturbing rituals.

Lucan breaks from epic tradition by minimizing, and in certain cases, completely ignoring (and some argue, denying) the existence of the traditional Roman deities. This is in marked contrast to his predecessors, Virgil and Ovid, who used anthropomorphized gods and goddesses as major players in their works. According to Susanna Braund, by choosing to not focus on the gods, Lucan emphasizes and underscores the human role in the atrocities of the Roman civil war.Braund (2009), pp. xxiiixxiv. James Duff, on the other hand, argues that " ucanwas dealing with Roman history and with fairly recent events; and the introduction of the gods as actors must have been grotesque".

This, however, is not to say that the ''Pharsalia'' is devoid of any supernatural phenomenon; in fact, quite the opposite is true, and Braund argues that "the supernatural in all its manifestations played a highly significant part in the structuring of the epic". Braund sees the supernatural as falling into two categories: "dreams and visions" and "portents, prophecies, and consultations of supernatural powers".Braund (1992), p. xxv. In regards to the first category, the poem features four explicit and important dream and vision sequences: Caesar's vision of Roma as he is about to cross the Rubicon, the ghost of Julia appearing to Pompey, Pompey's dream of his happy past, and Caesar and his troops' dream of battle and destruction. All four of these dream-visions are placed strategically throughout the poem, "to provide balance and contrast". In regards to the second category, Lucan describes a number of portents, two oracular episodes, and Erichtho's necromantic rite.Braund (1992), p. xxviii. This manifestation of the supernatural is more public, and serves many purposes, including to reflect "Rome's turmoil on the supernatural plane", as well as simply to "contribute to the atmosphere of sinster foreboding" by describing disturbing rituals.

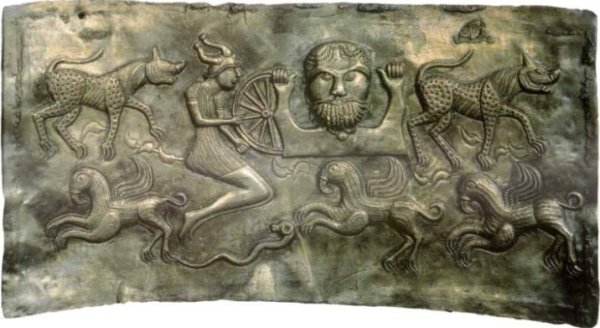

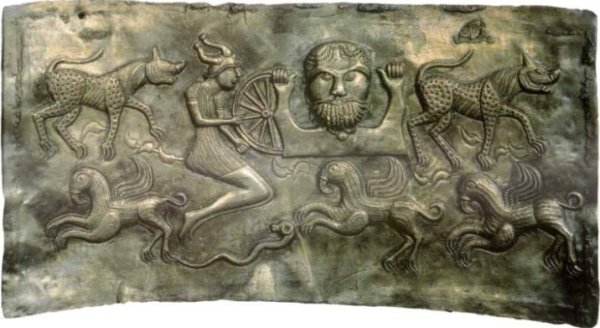

Interior plate C – The bust of a bearded man, holding a wheel, is possibly Taranis, god of the wheel.

The feminine figure beside him is possibly "Diana, goddess of the north".

Interior plate C – The bust of a bearded man, holding a wheel, is possibly Taranis, god of the wheel.

The feminine figure beside him is possibly "Diana, goddess of the north".

Lucan's work was popular in his own day and remained a school text in late antiquity and during the Middle Ages. Over 400 manuscripts survive; its interest to the court of

Lucan's work was popular in his own day and remained a school text in late antiquity and during the Middle Ages. Over 400 manuscripts survive; its interest to the court of

Full text of the ''Pharsalia''

via

Full text

of the ''Pharsalia'' in English vi

The Medieval and Classical Literature LibraryHousman's edition of the ''Pharsalia''

via

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

epic poem

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard to ...

written by the poet Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November AD 39 – 30 April AD 65), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba, Hispania Baetica (present-day Córdoba, Spain). He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imper ...

, detailing the civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

between Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

and the forces of the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

led by Pompey the Great

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

. The poem's title is a reference to the Battle of Pharsalus

The Battle of Pharsalus was the decisive battle of Caesar's Civil War fought on 9 August 48 BC near Pharsalus in Central Greece. Julius Caesar and his allies formed up opposite the army of the Roman Republic under the command of Pompey. ...

, which occurred in 48 BC near Pharsalus Pharsalus may refer to:

* ''Pharsalus'' (planthopper), a genus of insects in the family Ricaniidae

* Farsala

Farsala (), known in Antiquity as Pharsalos (, ), is a town in southern Thessaly, in Greece. Farsala is located in the southern part ...

, Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

, in Northern Greece

Northern Greece () is used to refer to the northern parts of Greece, and can have various definitions.

Administrative term

The term "Northern Greece" is widely used to refer mainly to the two northern regions of Macedonia and (Western) Thra ...

. Caesar decisively defeated Pompey in this battle, which occupies all of the epic's seventh book. In the early twentieth century, translator J. D. Duff

James Duff Duff (20 November 1860 – 25 April 1940), known as J. D. Duff, was a Scottish translator and classical scholar best known for his edition of Juvenal. He was a Cambridge Apostle.

Biography

Duff was the son of Colonel James Duff, a ret ...

, while arguing that "no reasonable judgment can rank Lucan among the world's great epic poets", notes that the work is notable for Lucan's decision to eschew divine intervention and downplay supernatural occurrences in the events of the story. Scholarly estimation of Lucan's poem and poetry has since changed, as explained by commentator Philip Hardie

Philip Russell Hardie, FBA (born 13 July 1952) is a specialist in Latin literature at the University of Cambridge. He has written especially on Virgil, Ovid, and Lucretius, and on the influence of these writers on the literature, art, and ideolo ...

in 2013: "In recent decades, it has undergone a thorough critical re-evaluation, to re-emerge as a major expression of Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

nian politics and aesthetics, a poem whose studied artifice enacts a complex relationship between poetic fantasy and historical reality."Hardie (2013), p. 225

Origins

The poem was begun around AD 61 and several books were in circulation before the EmperorNero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

and Lucan had a bitter falling out. Lucan continued to work on the epic – despite Nero's prohibition against any publication of Lucan's poetry – and it was left unfinished when Lucan was compelled to suicide as part of the Pisonian conspiracy

The conspiracy of Gaius Calpurnius Piso in 65 CE was a major turning point in the reign of the Roman emperor Nero (reign 54–68). The plot reflected the growing discontent among the ruling class of the Roman state with Nero's increasingly d ...

in AD 65. In total, ten books were written and all survive; the tenth book breaks off abruptly with Caesar in Egypt.

Contents

Overview

Book 1: After a brief introduction lamenting the idea of Romans fighting Romans and an ostensibly flattering dedication toNero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

, the narrative summarizes background material leading up to the present war and introduces Caesar in northern Italy. Despite an urgent plea from the Spirit of Rome to lay down his arms, Caesar crosses the Rubicon

The Rubicon (; ; ) is a shallow river in northeastern Italy, just south of Cesena and north of Rimini. It was known as ''Fiumicino'' until 1933, when it was identified with the ancient river Rubicon, crossed by Julius Caesar in 49 BC.

The ri ...

, rallies his troops and marches south to Rome, joined by Curio

Curio may refer to:

Objects

*Bric-à-brac, lesser objets d'art for display

*Cabinet of curiosities, a room-sized collection or exhibit of curios or curiosities

*Collectables

*Curio cabinet, a cabinet constructed for the display of curios

People

* ...

along the way. The book closes with panic in the city, terrible portents and visions of the disaster to come.

Book 2: In a city overcome by despair, an old veteran presents a lengthy interlude regarding the previous civil war that pitted Marius against Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

. Cato the Younger is introduced as a heroic man of principle; as abhorrent as civil war is, he argues to Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC) was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, which was reta ...

that it is better to fight than do nothing. After siding with Pompey—the lesser of two evils—he remarries his ex-wife, Marcia, and heads to the field. Caesar continues south through Italy and is delayed by Domitius' brave resistance. He attempts a blockade of Pompey at Brundisium

Brindisi ( ; ) is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the city has played an essential role in trade and culture due to its strategic positio ...

, but the general makes a narrow escape to Greece.

Book 3: As his ships sail, Pompey is visited in a dream by Julia

Julia may refer to:

People

*Julia (given name), including a list of people with the name

*Julia (surname), including a list of people with the name

*Julia gens, a patrician family of Ancient Rome

*Julia (clairvoyant) (fl. 1689), lady's maid of Qu ...

, his dead wife and Caesar's daughter. Caesar returns to Rome and plunders the city, while Pompey reviews potential foreign allies. Caesar then heads for Spain, but his troops are detained at the lengthy siege of Massilia (Marseille). The city ultimately falls in a bloody naval battle.

Book 4: The first half of this book is occupied with Caesar's victorious campaign in Spain against Afranius and Petreius. Switching scenes to Pompey, his forces intercept a raft carrying Caesarians, who prefer to kill each other rather than be taken prisoner. The book concludes with Curio launching an African campaign on Caesar's behalf, where he is defeated and slain by the African King Juba.

Book 5: The Senate in exile confirms Pompey the true leader of Rome. Appius consults the Delphic Oracle

Pythia (; ) was the title of the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She specifically served as its oracle and was known as the Oracle of Delphi. Her title was also historically glossed in English as the Pythoness.

The Pythia w ...

to learn of his fate in the war, and leaves with a misleading prophecy. In Italy, after defusing a mutiny, Caesar marches to Brundisium and sails across the Adriatic to meet Pompey's army. Only a portion of Caesar's troops complete the crossing when a storm prevents further transit; he tries to personally send a message back but is himself nearly drowned. Finally, the storm subsides, and the armies face each other at full strength. With battle at hand, Pompey sends his wife to the island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

.

Book 6: Pompey's troops force Caesar's armies – featuring the heroic centurion Scaeva – to fall back to Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

. Lucan describes the wild Thessalian terrain as the armies wait for battle the next day. The remainder of the book follows Pompey's son Sextus, who wishes to know the future. He finds the most powerful witch in Thessaly, Erichtho

In Roman literature, Erichtho (from ) is a legendary Thessalian witch who appears in several literary works. She is noted for her horrifying appearance and her impious ways. Her first major role was in the Roman poet Lucan's epic ''Pharsalia'' ...

, and she reanimates the corpse of a dead soldier in a terrifying ceremony. The soldier predicts Pompey's defeat and Caesar's eventual assassination.

Book 7: The soldiers are pressing for battle, but Pompey is reluctant until Cicero convinces him to attack. The Caesarians are victorious, and Lucan laments the loss of liberty. Caesar is especially cruel as he mocks the dying Domitius and forbids cremation of the dead Pompeians. The scene is punctuated by a description of wild animals gnawing at the corpses, and a lament from Lucan for ''Thessalia, infelix'' – ill-fated Thessaly.

Book 8: Pompey himself escapes to Lesbos, reunites with his wife, then goes to Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

to consider his options. He decides to enlist aid from Egypt, but King Ptolemy is fearful of retribution from Caesar and plots to murder Pompey when he lands. Pompey suspects treachery; he consoles his wife and rows alone to the shore, meeting his fate with Stoic poise. His headless body is flung into the ocean, but washes up on shore and receives a humble burial from Cordus.

Book 9: Pompey's wife mourns her husband as Cato takes up leadership of the Senate's cause. He plans to regroup and heroically marches the army across Africa to join forces with King Juba, a trek that occupies most of the middle section of the book. On the way, he passes an oracle but refuses to consult it, citing Stoic principles. Caesar visits Troy and pays respects to his ancestral gods. A short time later he arrives in Egypt; when Ptolemy's messenger presents him with the head of Pompey, Caesar feigns grief to hide his joy at Pompey's death.

Book 10: Caesar arrives in Egypt, where he is beguiled by Ptolemy's sister, Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

. A banquet is held; Pothinus, Ptolemy's cynical and bloodthirsty chief minister, plots an assassination of Caesar, but is killed in his surprise attack on the palace. A second attack comes from Ganymede, an Egyptian noble, and the poem breaks off abruptly as Caesar is fighting for his life.

Completeness

Almost all scholars agree that the ''Pharsalia'' as we now have it is unfinished. Some debate exists, however, as to whether the poem was unfinished at the time of Lucan's death, or if the final few books of the work were lost at some point.Susanna Braund

Susanna H. Morton Braund (born 6 February 1957) is a professor of Latin poetry and its reception at the University of British Columbia. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

Education

Braund received her BA in Classics from the University of Cambridg ...

notes that little evidence has been found one way or the other, and that this question must "remain a matter of speculation".Braund (1992), p. xxxvii. Some argue that Lucan intended to end his poem with the Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Liberators' civil war between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius, in 42 BC, at Philippi in ...

(42 BC) or the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

(31 BC). Both these hypotheses seem unlikely, as they would have required Lucan to pen a work many times larger than what is extant: for instance, the ten-book poem we have today covers a total time of twenty months; were the poet to have continued this pace, his work would cover a time span of six to seventeen years, which scholars consider unlikely. An alternative considered "more attractive" by Braund is that Lucan intended for his poem to be sixteen books long and to end with the assassination of Caesar. This theory, too, has its problems, namely that Lucan would have been required to introduce and rapidly develop characters to replace Pompey and Cato. It also might have given the work a "happy ending", which seems inconsistent, tonally, with the poem as a whole. Ultimately, Braund argues that the best hypothesis is that Lucan's original intent was a twelve-book poem, mirroring the length of the ''Aeneid''. The best internal argument for this is that in his sixth book Lucan features a necromantic ritual that parallels and inverts many of the motifs found in Virgil's sixth book (which details Aeneas' consultation with the Sibyl

The sibyls were prophetesses or oracles in Ancient Greece.

The sibyls prophet, prophesied at holy sites.

A sibyl at Delphi has been dated to as early as the eleventh century BC by Pausanias (geographer), PausaniasPausanias 10.12.1 when he desc ...

and his subsequent descent into the underworld). Had the book been extended to twelve books, Braund contends that it would have ended with the death of Cato, and his subsequent apotheosis

Apotheosis (, ), also called divinization or deification (), is the glorification of a subject to divine levels and, commonly, the treatment of a human being, any other living thing, or an abstract idea in the likeness of a deity.

The origina ...

as a Stoic hero.Braund (1992), p. xxxviii.

Conversely, the Latinist Jamie Masters argues the opposite, that the finale of Book 10 is indeed the ending to the work as Lucan intended. Masters devotes an entire chapter to this hypothesis in his book ''Poetry and Civil War in Lucan's'' Bellum Civile (1992), arguing that by being open-ended and ambiguous, the poem's conclusion avoids "any kind of resolution, but till

image:Geschiebemergel.JPG, Closeup of glacial till. Note that the larger grains (pebbles and gravel) in the till are completely surrounded by the matrix of finer material (silt and sand), and this characteristic, known as ''matrix support'', is d ...

preserves the unconventional premises of its subject-matter: evil without alternative, contradiction without compromise, civil war without end".

Title

The poem is popularly known as the ''Pharsalia'', largely due to lines 985986 in Book 9, which read, ''Pharsalia nostra'' / ''Vivet'' ("Our Pharsalia shall live on").Duff (1928), p. xii. However, many scholars, such asJ. D. Duff

James Duff Duff (20 November 1860 – 25 April 1940), known as J. D. Duff, was a Scottish translator and classical scholar best known for his edition of Juvenal. He was a Cambridge Apostle.

Biography

Duff was the son of Colonel James Duff, a ret ...

and Braund, note that this is a recent name given to the work, and that the earliest manuscripts of the poem refer to it as ''De Bello Civili'' (''Concerning the Civil War''). Braund further argues that calling the poem ''Pharsalia'' "excessively ... privilege ... an episode which occupies only one book and occurs in the centre of the poem, rather than at its climax."

Style

Lucan is heavily influenced by Latin poetic tradition, most notablyOvid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

's ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' (, , ) is a Latin Narrative poetry, narrative poem from 8 Common Era, CE by the Ancient Rome, Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''Masterpiece, magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the world from its Cre ...

'' and of course Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'', the work to which the ''Pharsalia'' is most naturally compared. Lucan frequently appropriates ideas from Virgil's epic and "inverts" them to undermine their original, heroic purpose. Sextus' visit to the Thracian witch Erichtho

In Roman literature, Erichtho (from ) is a legendary Thessalian witch who appears in several literary works. She is noted for her horrifying appearance and her impious ways. Her first major role was in the Roman poet Lucan's epic ''Pharsalia'' ...

provides an example; the scene and language clearly reference Aeneas' descent into the underworld (also in Book VI), but while Virgil's description highlights optimism toward the future glories of Rome under Augustan rule, Lucan uses the scene to present a bitter and gory pessimism concerning the loss of liberty under the coming empire.

Like all Silver Age

The Ages of Man are the historical stages of human existence according to Greek mythology and its subsequent interpretatio romana, Roman interpretation.

Both Hesiod and Ovid offered accounts of the successive ages of humanity, which tend to pr ...

poets, Lucan received the rhetorical training common to upper-class young men of the period. The ''suasoria'' – a school exercise where students wrote speeches advising an historical figure on a course of action – no doubt inspired Lucan to compose some of the speeches found in the text. Lucan also follows the Silver Age custom of punctuating his verse with short, pithy lines or slogans known as ''sententiae'', a rhetorical tactic used to grab the attention of a crowd interested in oratory as a form of public entertainment. Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quin ...

singles out Lucan as a writer ''clarissimus sententiis'' – "most famous for his ''sententiae''", and for this reason ''magis oratoribus quam poetis imitandus'' – "(he is) to be imitated more by orators than poets". His style makes him unusually difficult to read.

Finally, in another break with Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

literary techniques, Lucan is fond of discontinuity. He presents his narrative as a series of discrete episodes often without any transitional or scene-changing lines, much like the sketches of myth strung together in Ovid's ''Metamorphoses''. The poem is more naturally organized on principles such as aesthetic balance or correspondence of scenes between books rather than the need to follow a story from a single narrative point of view. Lucan was considered among the ranks of Homer and Virgil.

Themes

Horrors of civil war

Lucan emphasizes the despair of his topic in the poem's first seven lines (the same length as the opening to Virgil's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

''):

Events throughout the poem are described in terms of insanity and sacrilege. Far from glorious, the battle scenes are portraits of bloody horror, where nature is ravaged to build terrible siege engines and wild animals tear mercilessly at the flesh of the dead.

Flawed characters

Most of the main characters featured in the ''Pharsalia'' are terribly flawed and unattractive. Caesar, for instance, is presented as a successful military leader, but he strikes fear into the hearts of people and is extremely destructive.Braund (1992), p. xxi. Lucan conveys this by using a simile (Book 1, lines 1517) that compares Caesar to athunderbolt

A thunderbolt or lightning bolt is a symbolic representation of lightning when accompanied by a loud thunderclap. In Indo-European mythology, the thunderbolt was identified with the 'Sky Father'; this association is also found in later Hel ...

:

Throughout the ''Pharsalia'', this simile holds, and Caesar is continuously depicted as an active force, who strikes with great power.

Pompey, on the other hand, is old and past his prime, and years of peacetime have turned him soft. Susanna Braund argues that Lucan "has taken the weaker, essentially ''human'', elements of Aeneas' characterAeneas doubting his mission, Aeneas as husband and loverand bestowed them upon Pompey." And while this portrays the leader as indecisive, slow to action, and ultimately ineffective, it does make him the only main character shown to have any sort of "emotional life."Braund (1992), p. xxii. What is more, Lucan at times explicitly roots for Pompey. But nevertheless, the leader is doomed in the end. Lucan compares Pompey to a large oak-tree (Book 1, lines 13643), which is still quite magnificent due to its size but on the verge of tipping over:

By comparing Caesar to a bolt of lightning, and Pompey to a large tree on the verge of death, Lucan poetically implies early on in the ''Pharsalia'' that Caesar will strike and fell Pompey.

The grand exception to this generally bleak depiction of characters is Cato, who stands as a Stoic ideal in the face of a world gone mad (he alone, for example, refuses to consult oracles to know the future). Pompey also seems transformed after Pharsalus, becoming a kind of stoic martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

; calm in the face of certain death upon arrival in Egypt, he receives virtual canonization from Lucan at the start of book IX. This elevation of Stoic and Republican principles is in sharp contrast to the ambitious and imperial Caesar, who becomes an even greater monster after the decisive battle. Even though Caesar wins in the end, Lucan makes his sentiments known in the famous line ''Victrix causa deis placuit sed Victa Catoni'' – "The victorious cause pleased the gods, but the vanquished ause

Australian English (AusE, AusEng, AuE, AuEng, en-AU) is the set of varieties of the English language native to Australia. It is the country's common language and ''de facto'' national language. While Australia has no official language, Engl ...

pleased Cato."

Anti-imperialism

Given Lucan's clear anti-imperialism, the flattering Book I dedication to Nero – which includes lines like ''multum Roma tamen debet ciuilibus armis , quod tibi res acta est'' – "But Rome is greater by these civil wars, because it resulted in you" – is somewhat puzzling. Some scholars have tried to read these lines ironically, but most see it as a traditional dedication written at a time before the (supposed) true depravity of Lucan's patron was revealed. The extant "Lives" of the poet support this interpretation, stating that a portion of the ''Pharsalia'' was in circulation before Lucan and Nero had their falling out. Furthermore, according to Braund, Lucan's negative portrayal of Caesar in the early portion of the poem was not likely meant as criticism of Nero, and it may have been Lucan's way of warning the new emperor about the issues of the past.Treatment of the supernatural

Lucan breaks from epic tradition by minimizing, and in certain cases, completely ignoring (and some argue, denying) the existence of the traditional Roman deities. This is in marked contrast to his predecessors, Virgil and Ovid, who used anthropomorphized gods and goddesses as major players in their works. According to Susanna Braund, by choosing to not focus on the gods, Lucan emphasizes and underscores the human role in the atrocities of the Roman civil war.Braund (2009), pp. xxiiixxiv. James Duff, on the other hand, argues that " ucanwas dealing with Roman history and with fairly recent events; and the introduction of the gods as actors must have been grotesque".

This, however, is not to say that the ''Pharsalia'' is devoid of any supernatural phenomenon; in fact, quite the opposite is true, and Braund argues that "the supernatural in all its manifestations played a highly significant part in the structuring of the epic". Braund sees the supernatural as falling into two categories: "dreams and visions" and "portents, prophecies, and consultations of supernatural powers".Braund (1992), p. xxv. In regards to the first category, the poem features four explicit and important dream and vision sequences: Caesar's vision of Roma as he is about to cross the Rubicon, the ghost of Julia appearing to Pompey, Pompey's dream of his happy past, and Caesar and his troops' dream of battle and destruction. All four of these dream-visions are placed strategically throughout the poem, "to provide balance and contrast". In regards to the second category, Lucan describes a number of portents, two oracular episodes, and Erichtho's necromantic rite.Braund (1992), p. xxviii. This manifestation of the supernatural is more public, and serves many purposes, including to reflect "Rome's turmoil on the supernatural plane", as well as simply to "contribute to the atmosphere of sinster foreboding" by describing disturbing rituals.

Lucan breaks from epic tradition by minimizing, and in certain cases, completely ignoring (and some argue, denying) the existence of the traditional Roman deities. This is in marked contrast to his predecessors, Virgil and Ovid, who used anthropomorphized gods and goddesses as major players in their works. According to Susanna Braund, by choosing to not focus on the gods, Lucan emphasizes and underscores the human role in the atrocities of the Roman civil war.Braund (2009), pp. xxiiixxiv. James Duff, on the other hand, argues that " ucanwas dealing with Roman history and with fairly recent events; and the introduction of the gods as actors must have been grotesque".

This, however, is not to say that the ''Pharsalia'' is devoid of any supernatural phenomenon; in fact, quite the opposite is true, and Braund argues that "the supernatural in all its manifestations played a highly significant part in the structuring of the epic". Braund sees the supernatural as falling into two categories: "dreams and visions" and "portents, prophecies, and consultations of supernatural powers".Braund (1992), p. xxv. In regards to the first category, the poem features four explicit and important dream and vision sequences: Caesar's vision of Roma as he is about to cross the Rubicon, the ghost of Julia appearing to Pompey, Pompey's dream of his happy past, and Caesar and his troops' dream of battle and destruction. All four of these dream-visions are placed strategically throughout the poem, "to provide balance and contrast". In regards to the second category, Lucan describes a number of portents, two oracular episodes, and Erichtho's necromantic rite.Braund (1992), p. xxviii. This manifestation of the supernatural is more public, and serves many purposes, including to reflect "Rome's turmoil on the supernatural plane", as well as simply to "contribute to the atmosphere of sinster foreboding" by describing disturbing rituals.

The poem as civil war

According to Jamie Masters, Lucan's ''Pharsalia'' is not just a poem about a civil war, but rather in a metaphorical way ''is'' a civil war. In other words, he argues that Lucan embraces the metaphor of internal discord and allows it to determine the way the story is told by weaving it into the fabric of the poem itself. Masters proposes that Lucan's work is both "Pompeian" (in the sense that it celebrates the memory of Pompey, revels in delay, and decries the horrors of civil war) and "Caesarian" (in the sense that it still recounts Pompey's death, eventually overcomes delay, and describes the horrors of war in careful detail).Masters (1992), pp. 810. Because Lucan is on both of the characters' sides whilst also supporting neither, the poem is inherently at war with itself.Masters (1992), p. 10. Furthermore, because Lucan seems to place numerous obstacles before Caesar, he can be seen as opposing Caesar's actions. However, since Lucan still chooses to record them in song, hebeing the poet and thus the one who has the final say on what goes into his workis in some ways waging the war himself. Ultimately, Masters refers to the binary opposition that he sees throughout the entire poem as Lucan's "schizophrenic poetic persona".Poetic representation of history

Though the ''Pharsalia'' is an historical epic, it would be wrong to think Lucan is only interested in the details of history itself. As one commentator has pointed out, Lucan is more concerned "with the significance of events rather than the events themselves".Barbaric nature of the Celts

Triad of Gaulish deities

Lucan alludes to the barbaric nature of theCelts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

, while describing the call-out of troops from Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

, at the beginning of Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

.

..."Et quibus immitis placatur sanguine diroThe Celts were accused of the

Teutates, horrensque feris altaribus Hesus,

Et Taranis Scythicae non mitior ara Dianae.

–Lucan Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November AD 39 – 30 April AD 65), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba, Hispania Baetica (present-day Córdoba, Spain). He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imper ..., ''Pharsalia'', book 1, lines 444–446.

propitiation

Propitiation is the act of appeasing or making well-disposed a deity, thus incurring divine favor or avoiding divine retribution. It is related to the idea of atonement and sometime mistakenly conflated with expiation. The discussion here encompa ...

of their gods by acts of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

:

# Teutates

Teutates (spelled variously Toutatis, Totatis, Totates) is a Celtic god attested in literary and epigraphic sources. His name, which is derived from a proto-Celtic word meaning "tribe", suggests he was a tribal deity.

The Roman poet Lucan's ...

favoured death by drowning.

# Hesus

Esus is a Celtic god known from iconographic, epigraphic, and literary sources.

The 1st-century CE Roman poet Lucan's epic ''Pharsalia'' mentions Esus, Taranis, and Teutates as gods to whom the Gauls sacrificed humans. This rare mention of Cel ...

favoured death by hanging.

# Taranis

Taranis (sometimes Taranus or Tanarus) is a Celtic thunder god attested in literary and epigraphic sources.

The Roman poet Lucan's epic ''Pharsalia'' mentions Taranis, Esus, and Teutates as gods to whom the Gauls sacrificed humans. This rare ...

favoured death by burning

Death by burning is an execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment for and warning agai ...

.

=List of deities

= List of deities mentioned in book 1:=Lucan's sources

= The source of Lucan's information is not known – ''Pharsalia'' was written about 100 years after theBattle of Pharsalus

The Battle of Pharsalus was the decisive battle of Caesar's Civil War fought on 9 August 48 BC near Pharsalus in Central Greece. Julius Caesar and his allies formed up opposite the army of the Roman Republic under the command of Pompey. ...

(9 August 48 BC). It is possible that oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

s about the pagan practices of the Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

were well known in Roman society before Lucan wrote ''Pharsalia'', and that variants arose that were a mix of fact and fiction, designed to entertain and thrill an audience.

Some historians consider the possibility that Roman commentators exaggerated the barbaric nature of the Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

, perhaps in order to justify the Roman annexation of their lands, and attempts to subjugate

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and Romanise them.

=Votive offerings

= Although it is true that theCelts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

did practice human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

, it is unlikely that it was as barbaric as Lucan suggested; it is more likely to have taken the form of a votive offering

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally ...

to the Celtic gods – possibly in response to a natural or man-made disaster, such as a famine or war. During the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

, votive offerings became increasingly more precious and labour-intensive, for example the Battersea Shield

The Battersea Shield is one of the most significant pieces of ancient Celtic art found in Britain. It is a sheet bronze covering of a (now vanished) wooden shield decorated in La Tène style. The shield is on display in the British Museum, a ...

found at an ancient crossing point of the Thames,

or the Gundestrup cauldron

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD, or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early Roman Iron Age. The cauldron is t ...

, found in Denmark.

The druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. The druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no wr ...

s had extraordinary power and influence, and were able to arrange the most ultimate votive offering – the sacrifice of a person of importance –, for example, a tribal leader.

=Gundestrup cauldron

= TheGundestrup cauldron

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD, or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early Roman Iron Age. The cauldron is t ...

, found in Denmark, is an outstanding example of Iron Age art and craftsmanship. Experts consider the possibility that the cauldron was made in the lower Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

basin, due to its Thracian style of metalworking.

The internal plates C and E possibly depict the Gaulish deities Taranis

Taranis (sometimes Taranus or Tanarus) is a Celtic thunder god attested in literary and epigraphic sources.

The Roman poet Lucan's epic ''Pharsalia'' mentions Taranis, Esus, and Teutates as gods to whom the Gauls sacrificed humans. This rare ...

and Teutates

Teutates (spelled variously Toutatis, Totatis, Totates) is a Celtic god attested in literary and epigraphic sources. His name, which is derived from a proto-Celtic word meaning "tribe", suggests he was a tribal deity.

The Roman poet Lucan's ...

:

Interior plate A – The horned god Cernunnos

Cernunnos is a Celtic god whose name is only clearly attested once, on the 1st-century CE Pillar of the Boatmen from Paris, where it is associated with an image of an aged, antlered figure with torcs around his horns.

Through the Pillar of the ...

is known primarily from Pillar of the Boatmen

The Pillar of the Boatmen () is a monumental Roman column erected in Lutetia (modern Paris) in honour of Jupiter (god), Jupiter by the guild of boatmen in the 1st century AD. It is the oldest monument in Paris and is one of the earliest pieces of r ...

, which also includes a dedication to the Gaulish deity Esus, god of the river.

Interior plate C – The bust of a bearded man, holding a wheel, is possibly Taranis, god of the wheel.

The feminine figure beside him is possibly "Diana, goddess of the north".

Interior plate C – The bust of a bearded man, holding a wheel, is possibly Taranis, god of the wheel.

The feminine figure beside him is possibly "Diana, goddess of the north".

..."Et Taranis Scythicae non mitior ara Dianae.Interior plate E – It has been ''conjectured'' that the giant figure on the left might be the Gaulish deity

–Lucan Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November AD 39 – 30 April AD 65), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba, Hispania Baetica (present-day Córdoba, Spain). He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imper ..., ''Pharsalia'', book 1, line 446.

A more literal translation might be:

..."And Taranis'Scythian The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people who had migrated during the 9th to 8th centuries BC fr ...non- placid altar Diana.

Teutates

Teutates (spelled variously Toutatis, Totatis, Totates) is a Celtic god attested in literary and epigraphic sources. His name, which is derived from a proto-Celtic word meaning "tribe", suggests he was a tribal deity.

The Roman poet Lucan's ...

. The iconography was possibly influenced by the same sources that Lucan used for ''Pharsalia''.

Influence

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

is evidenced by the existence of five complete manuscripts from the 9th century. Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

includes Lucan among other classical poets in the first circle of the ''Inferno

Inferno may refer to:

* Hell, an afterlife place of suffering

* Conflagration, a large uncontrolled fire

Film

* ''L'Inferno'', a 1911 Italian film

* ''Inferno'' (1953 film), a film noir by Roy Ward Baker

* ''Inferno'' (1980 film), an Italian ...

'', and draws on the ''Pharsalia'' in the scene with Antaeus

Antaeus (; , derived from ), known to the Berbers as Anti, was a figure in Traditional Berber religion, Berber and Greek mythology. He was famed for his defeat by Heracles as part of the Labours of Hercules.

Family

In Greek sources, he was ...

(a giant depicted in a story from Lucan's book IV).

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe ( ; Baptism, baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), also known as Kit Marlowe, was an English playwright, poet, and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the English Renaissance theatre, Eli ...

published a translation of Book I, while Thomas May

Thomas May (1594/95 – 13 November 1650) was an English poet, dramatist and historian of the Renaissance era.

Early life and career until 1630

May was born in Mayfield, Sussex, the son of Sir Thomas May, a minor courtier. He matriculated a ...

followed with a complete translation into heroic couplet

A heroic couplet is a traditional form for English poetry, commonly used in epic and narrative poetry, and consisting of a rhyming pair of lines in iambic pentameter. Use of the heroic couplet was pioneered by Geoffrey Chaucer in the '' Legen ...

s in 1626.Watt (1824), p. 620. May later translated the remaining books and wrote a continuation of Lucan's incomplete poem. The seven books of May's effort take the story through to Caesar's assassination.

It probably inspired at least two of the best known lines – "Musick has Charms to soothe a savage Breast, / To soften Rocks, or bend a knotted Oak" – from William Congreve

William Congreve (24 January 1670 – 19 January 1729) was an English playwright, satirist, poet, and Whig politician. He spent most of his career between London and Dublin, and was noted for his highly polished style of writing, being regard ...

's 1697 play ''The Mourning Bride

''The Mourning Bride'' is a tragedy written by English playwright William Congreve. It premiered in 1697 at Betterton's Co., Lincoln's Inn Fields. The play centers on Zara, a queen held captive by Manuel, King of Granada, and a web of love and ...

''.

The line ''Victrix causa deis placuit sed victa Catoni'' has been a favorite for supporters of "lost" causes over the centuries; it can be translated as "the winning cause pleased the gods, but the lost cause pleased Cato". One American example comes from the Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

, which has these words in Latin inscribed on its base. An English example is found in the speech of Viscount Radcliffe in the House of Lords adjudicating on a tax appeal.

The English poet and classicist A. E. Housman

Alfred Edward Housman (; 26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936) was an English classics, classical scholar and poet. He showed early promise as a student at the University of Oxford, but he failed his final examination in ''literae humaniores'' and t ...

published a landmark critical edition of the poem in 1926.Hirst (1927), pp. 546.

Footnotes

References

Citations

Notes for citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

Translations

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

;Latin copies *Full text of the ''Pharsalia''

via

The Latin Library

The Latin Library is a website that collects public domain Latin texts. It is run by William L. Carey, adjunct professor of Latin and Roman Law at George Mason University. The texts have been drawn from different sources, are not intended for rese ...

Full text

of the ''Pharsalia'' in English vi

The Medieval and Classical Literature Library

via

HathiTrust

HathiTrust Digital Library is a large-scale collaborative repository of digital content from research libraries. Its holdings include content digitized via Google Books and the Internet Archive digitization initiatives, as well as content digit ...

*

{{Authority control

1st-century books in Latin

Epic poems in Latin

Classical Latin poems

Historical poems

Unfinished poems

Unfinished literature completed by others

Lucan

Ancient Thessaly

Macedonia (Roman province)

Caesar's civil war

Fictional depictions of Julius Caesar in literature

Fictional depictions of Cleopatra in literature

Cultural depictions of Pompey

Cultural depictions of Cato the Younger