Peace Pledge Union on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

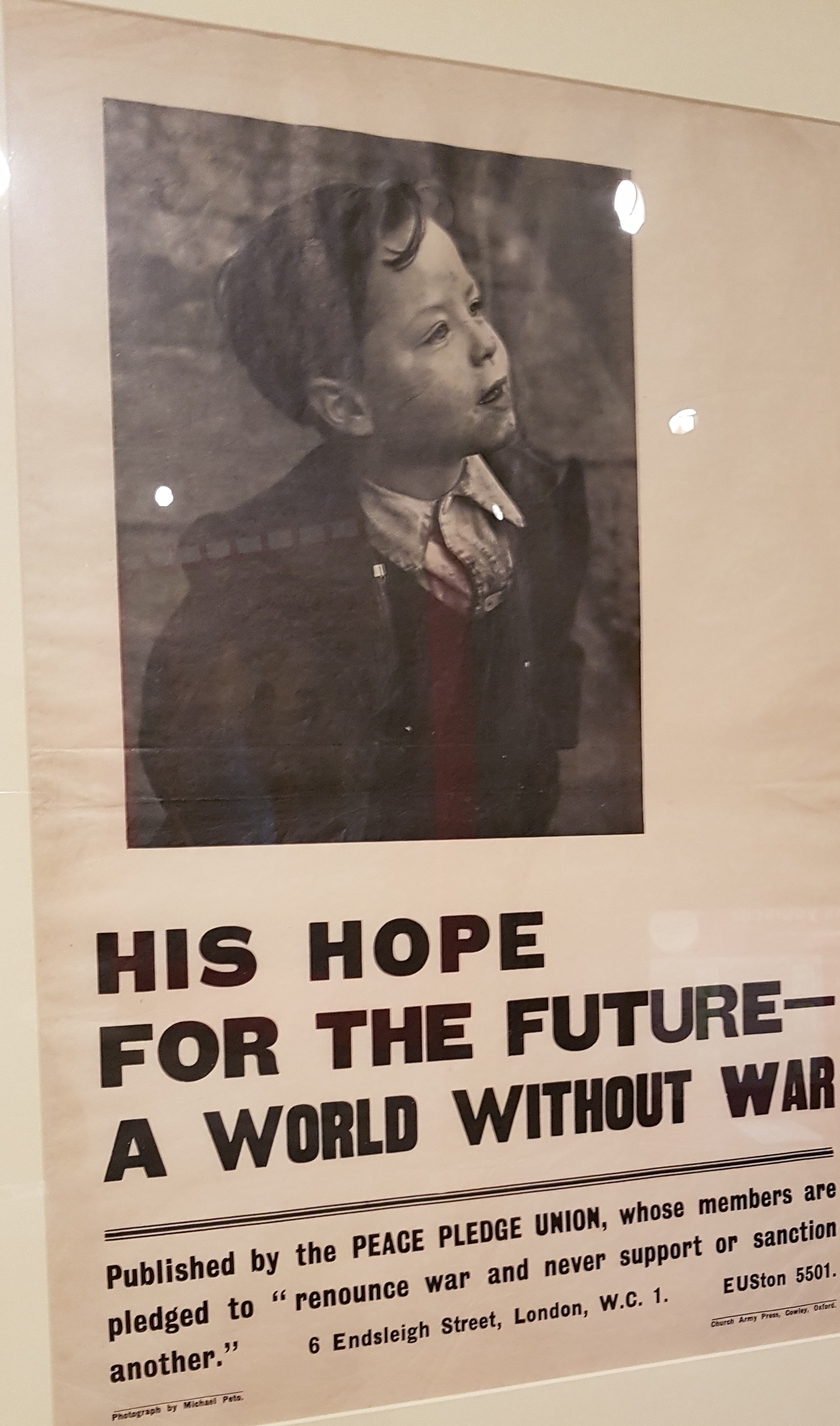

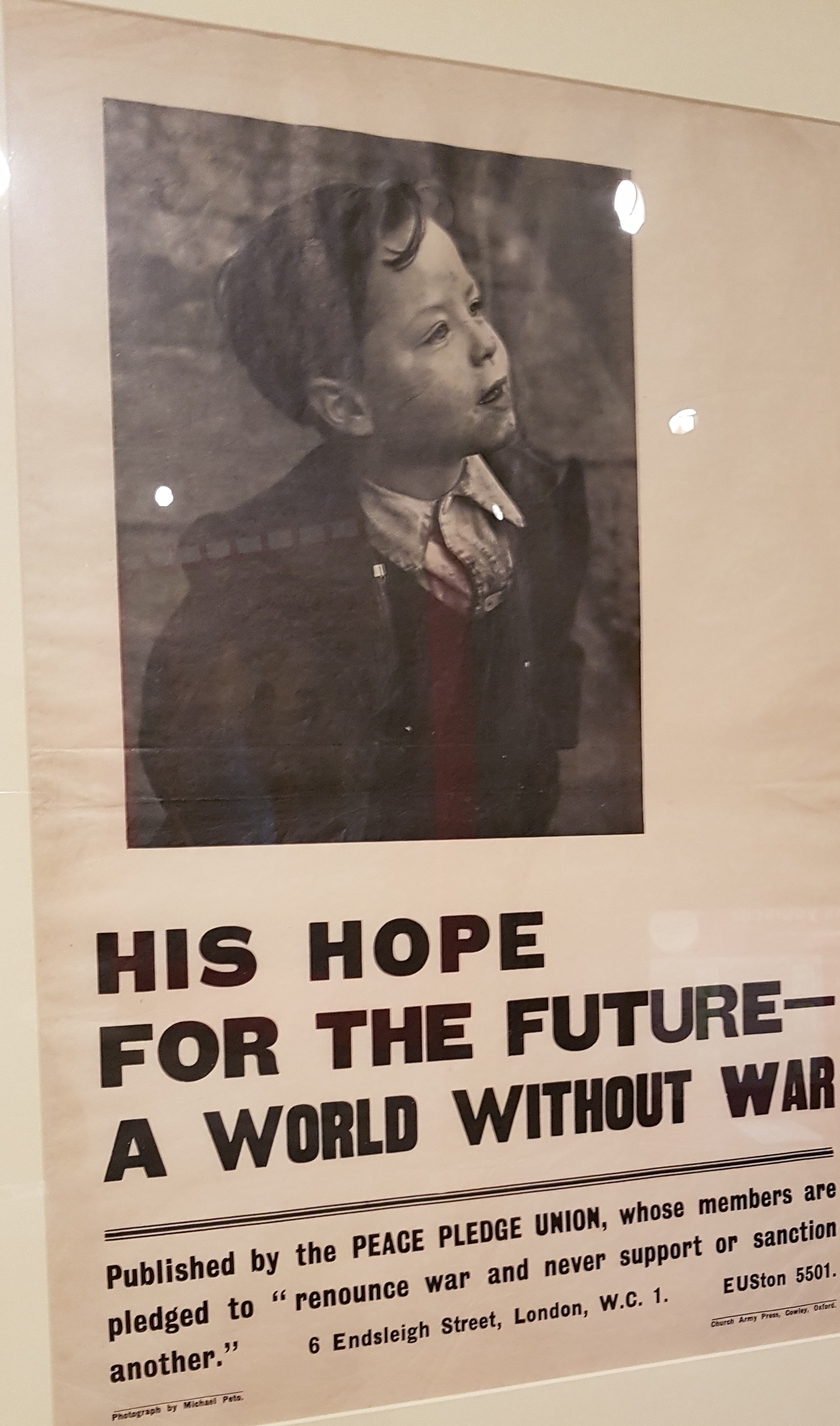

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a

The PPU emerged from an initiative by Hugh Richard Lawrie 'Dick' Sheppard, canon of

The PPU emerged from an initiative by Hugh Richard Lawrie 'Dick' Sheppard, canon of

The PPU's most visible contemporary activity is the White Poppy appeal, started in 1933 by the Women's Co-operative Guild alongside the Royal British Legion's red poppy appeal. The white poppy commemorated not only British soldiers killed in war, but also civilian victims on all sides, standing as "a pledge to peace that war must not happen again". In 1986,

The PPU's most visible contemporary activity is the White Poppy appeal, started in 1933 by the Women's Co-operative Guild alongside the Royal British Legion's red poppy appeal. The white poppy commemorated not only British soldiers killed in war, but also civilian victims on all sides, standing as "a pledge to peace that war must not happen again". In 1986,

About Dick Sheppard

on the PPU website {{Authority control 1934 establishments in the United Kingdom Organizations established in 1934 Organisations based in the London Borough of Camden Peace organisations based in the United Kingdom Conscientious objection organizations

non-governmental organisation

A non-governmental organization (NGO) is an independent, typically nonprofit organization that operates outside government control, though it may get a significant percentage of its funding from government or corporate sources. NGOs often focus ...

that promotes pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

, based in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determined not to support any kind of war. I am also determined to work for the removal of all causes of war", and campaign to promote peaceful and nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

solutions to conflict. The PPU forms the British section of War Resisters' International

War Resisters' International (WRI), headquartered in London, is an international anti-war organisation with members and affiliates in over 40 countries.

History

''War Resisters' International'' was founded in Bilthoven, Netherlands in 1921 un ...

.

History

Formation

The PPU emerged from an initiative by Hugh Richard Lawrie 'Dick' Sheppard, canon of

The PPU emerged from an initiative by Hugh Richard Lawrie 'Dick' Sheppard, canon of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

, in 1934, after he had published a letter in the ''Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' and other newspapers, inviting men (but not women) to send him postcards pledging never to support war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

. Andrew Rigby, "The Peace Pledge Union: From Peace to War, 1936–1945" in Peter Brock

Peter Geoffrey Brock (26 February 1945 – 8 September 2006), known as "Peter Perfect", "The King of the Mountain", or simply "Brocky", was an Australian motor racing driver. Brock was most often associated with Holden for almost 40 years, al ...

, Thomas Paul Socknat ''Challenge to Mars:Pacifism from 1918 to 1945''. University of Toronto Press, 1999. (pp. 169–185) 135,000 men responded and, with co-ordination by Sheppard, the Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

Reverend John C. B. Myer, and others, formally became members. The initial male-only aspect of the pledge was aimed at countering the idea that only women were involved in the peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world pe ...

. In 1936 membership was opened to women, and the newly founded '' Peace News'' was adopted as the PPU's weekly newspaper. The PPU assembled several noted public figures as sponsors, including Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley ( ; 26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. His bibliography spans nearly 50 books, including non-fiction novel, non-fiction works, as well as essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the ...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, Storm Jameson

Margaret Ethel Storm Jameson (8 January 1891 – 30 September 1986) was an English journalist and author, known for her novels and reviews and for her work as President of English PEN between 1938 and 1944.

Life and career

Jameson was born in ...

, Rose Macaulay

Dame Emilie Rose Macaulay, (1 August 1881 – 30 October 1958) was an English writer, most noted for her award-winning novel ''The Towers of Trebizond'', about a small Anglo-Catholic group crossing Turkey by camel.

The story is seen as a spiri ...

, Donald Soper, Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World ...

, Reginald Sorensen, J. D. Beresford, Ursula Roberts (who wrote under the pseudonym "Susan Miles") and Brigadier-General F. P. Crozier (a former army officer turned pacifist).

The PPU attracted members across the political spectrum, including Christian pacifists, socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

, anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

and in the words of member Derek Savage, "an amorphous mass of ordinary well-meaning but fluffy peace-lovers". The suffragist, Sybil Morrison, spoke to the historian, Brian Harrison, about her involvement with the Peace Pledge Union as part of the Suffrage Interviews project, titled ''Oral evidence on the suffragette and suffragist movements: the Brian Harrison interviews.'' In 1937 the No More War Movement formally merged with the PPU. George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1 ...

, previously chair of the No More War Movement, became president of the PPU, holding the post until his death in 1940. In 1937 a group of clergy and laity led by Sheppard formed the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship The Anglican Pacifist Fellowship (APF) is a body of people within the Anglican Communion who reject war as a means of solving international disputes, and believe that peace and justice should be sought through nonviolence, nonviolent means.

Belief ...

as an Anglican complement to the non-sectarian PPU. The Union was associated with the Welsh group, ''Heddwchwyr Cymru'', founded by Gwynfor Evans

Gwynfor Richard Evans (1 September 1912 – 21 April 2005) was a Welsh politician, lawyer and author. He was President of the Welsh political party Plaid Cymru for thirty-six years and was the first member of Parliament to represent it at West ...

. In March 1938, PPU George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1 ...

launched the PPU's first manifesto and peace campaign. The campaign argued that the idea of a war to defend democracy was a contradiction in terms and that "in a period of total war, democracy would be submerged under

totalitarianism".

A large part of the PPU's work involved providing for the victims of war. Its members sponsored a house where 64 Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

children, refugees from the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, were cared for. PPU archivist William Hetherington writes that "The PPU also encouraged members and groups to sponsor individual Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

refugees from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

and Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

to enable them to be received into the United Kingdom".William Hetherington, "Peace Pledge Union" in ''The World Encyclopedia of Peace''. Edited by Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

, Ervin Laszlo Ervin may refer to:

* Ervin (given name)

* Ervin (surname)

*Ervin Township, Howard County, Indiana, one of eleven townships in Howard County, Indiana, USA

See also

* Justice Ervin (disambiguation)

* Earvin

* Ervine

* Erving (disambiguation)

* Erw ...

, and Jong Youl Yoo. Oxford : Pergamon, 1986. (p.243-7).

In 1938 the PPU opposed legislation for air-raid precautions and in 1939 campaigned against military conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

.

Attitudes towards Nazi Germany

Like many in the 1930s, the PPU supported aspects ofappeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

, with some members suggesting that Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

would cease its aggression if the territorial provisions of the Versailles Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace of Versailles, exactl ...

were undone.David C. Lukowitz, "British Pacifists and Appeasement: The Peace Pledge Union", ''Journal of Contemporary History'', Vol. 9, No. 1, January 1974, pp. 115–127 It backed Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

's policy at Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

in 1938, regarding Hitler's claims on the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

as legitimate. At the time of the Munich crisis, several PPU sponsors tried to send "five thousand pacifists to the Sudetenland as a non-violent presence", however this attempt came to nothing.

''Peace News'' editor and PPU sponsor John Middleton Murry

John Middleton Murry (6 August 1889 – 12 March 1957) was an English writer. He was a prolific author, producing more than 60 books and thousands of essays and reviews on literature, social issues, politics, and religion during his lifetime. ...

and his supporters in the group caused considerable controversy by arguing Germany should be given control of parts of mainland Europe. In a PPU publication, ''Warmongers'', Clive Bell

Arthur Clive Heward Bell (16 September 1881 – 17 September 1964) was an English art critic, associated with formalism and the Bloomsbury Group. He developed the art theory known as significant form.

Biography Early life and education

Bell ...

said that Germany should be permitted to "absorb" France, Poland, the Low Countries and the Balkans. However, this was never the official policy of the PPU and the position quickly drew criticism from other PPU activists such as Vera Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain (29 December 1893 – 29 March 1970) was an English Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse, writer, feminist, socialist and pacifist. Her best-selling 1933 memoir '' Testament of Youth'' recounted her experiences during the Fir ...

and Andrew Stewart. Clive Bell left the PPU shortly afterwards and by 1940 he was supporting the war.

Some PPU supporters were so sympathetic to German grievances that PPU supporter Rose Macaulay claimed she found it difficult to distinguish between the PPU newspaper ''Peace News'' and that of the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

(BUF), saying, "occasionally when reading ''Peace News'', I (and others) half think we have got hold of the ''Blackshirt'' UF journalby mistake". There was Fascist infiltration of the PPU and MI5

MI5 ( Military Intelligence, Section 5), officially the Security Service, is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), Gov ...

kept an eye on the PPU's "small Fascist connections". After Dick Sheppard's death in October 1937, George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

, always hostile to pacifism, accused the PPU of "moral collapse" on the grounds that some members even joined the BUF. However, several historians note that the situation may have been the other way around; that is, BUF members attempted to infiltrate the PPU. On 11 August 1939, the Deputy Editor of ''Peace News'', Andrew Stewart, criticised those "who think that membership of British Union, Sir Oswald Moseley's Fascist organization, is compatible with membership of the PPU". In November 1939, an MI5 officer reported that members of the far-right Nordic League were attempting "to join the PPU en masse".

Historians have differed in their interpretation of the PPU's attitude to Nazi Germany. The historian Mark Gilbert said, "it is hard to think of a British newspaper that was so consistent an apologist for Nazi Germany as ''Peace News''," which "assiduously echoed the Nazi press's claims that far worse offences than the Kristallnacht

( ) or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from the Hitler Youth and German civilia ...

events were a regular feature of British colonial rule". But David C. Lukowitz argues that, "it is nonsense to charge the PPU with pro-Nazi sentiments. From the outset it emphasised that its primary dedication was to world peace, to economic justice and racial equality," but it had "too much sympathy for the German position, often the product of ignorance and superficial thinking". Research by the historian Richard Griffiths, published in 2017, suggests considerable division and controversy at the top of the PPU, with the editors of ''Peace News'' being generally more willing to play down the dangers of Nazi Germany than were many members of the PPU Executive.

Controversy over the PPU's attitude towards Nazi Germany has continued ever since the war. In 1950, Rebecca West

Dame Cecily Isabel Fairfield (21 December 1892 – 15 March 1983), known as Rebecca West, or Dame Rebecca West, was a British author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. An author who wrote in many genres, West reviewed books ...

, in her book ''The Meaning of Treason'', described the PPU as "that ambiguous organisation which in the name of peace was performing many actions certain to benefit Hitler". The publishers removed the phrase from subsequent editions of the book following representations by the PPU, but West refused to apologise. As recently as 2017, the right-wing commentator and retired colonel Richard Kemp alleged on ''Good Morning Britain'' that the PPU were "arch-appeasers" who had supported the absorption of the Low Countries into Germany's sphere of influence. This was denied by the PPU representative on the programme, who stated that the PPU had campaigned against arms sales to Fascist regimes when the UK government was selling weapons to Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his overthrow in 194 ...

.

Second World War

Initially, the Peace Pledge Union opposed theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and continued to argue for a negotiated peace with Germany. On 9 March 1940, 2,000 people attended a PPU public meeting calling for a negotiated peace. PPU membership reached a peak of 140,000 in 1940.

For some members of the PPU, the focus was less on a negotiated peace and more on "nonviolent revolution" in both Britain and Germany. In 1940, the PPU published a booklet called ''Plan of Campaign'', reprinting an article by the Dutch Christian anarcho-pacifist Bart de Ligt

Bartholomeus de Ligt (17 July 1883 – 3 September 1938) was a Dutch anarcho-pacifist and antimilitarist. He is chiefly known for his support of conscientious objectors.

Life and work

Born on 17 July 1883 in Schalkwijk, Utrecht, his father wa ...

. He called for war to be made impossible by direct action, including "the most effective non-co-operation, boycott and sabotage". Not all PPU members were happy with this approach and the booklet was withdrawn from sale in London.

In February 1940, the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

'' newspaper called for the PPU to be banned. While the government decided not to ban the PPU, a number of PPU members faced arrest and prosecution for campaigning against war. In May 1940, six leading PPU activists—Alex Wood, Stuart Morris, Maurice Rowntree, John Barclay, Ronald Smith and Sidney Todd—were charged over the publication of a pacifist poster that was aimed at encouraging people of all nationalities to refuse to fight. The charge read out in court was that they "did endeavour to cause among persons in His Majesty's Service disaffection likely to lead to breaches of their duty". They were prosecuted by the Attorney-General, Donald Somervell KC. They were defended by John Platts-Mills

John Faithful Fortescue Platts-Mills, (4 October 1906 – 26 October 2001) was a British barrister and left-wing politician. He was the Labour Party Member of Parliament for Finsbury from 1945 to 1948, when he was expelled from the party effec ...

and were convicted but not imprisoned. The PPU Council voted by a majority to withdraw the poster in question, although this seems to have been a controversial decision within the PPU. Other PPU members were also arrested, for holding open-air meetings during the war and selling ''Peace News'' in the street. In 1942, PPU General Secretary Stuart Morris was sentenced to nine months in prison for dealing with secret government documents relating to British rule in India, which he was alleged to have been planning to pass to Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British ...

or others in the nonviolent wing of the Indian independence movement. The trial was held in secret. The PPU Council disassociated itself from Morris' actions.

The critical attitude towards the PPU in this period was summarised by George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

, writing in the October 1941 issue of '' Adelphi'' magazine: "Since pacifists have more freedom of action in countries where traces of democracy survive, pacifism can act more effectively against democracy than for it. Objectively, the pacifist is pro-Nazi".

Following the fall of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Net ...

, support for the PPU dropped considerably and some former members even volunteered for the armed forces. The PPU abandoned the focus on peace negotiations. PPU members instead concentrated on activities such as supporting British conscientious objectors

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or freedom of religion, religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for ...

and supporting the Food Relief Campaign. A few members of the PPU joined the Bruderhof in the Cotswolds, which was seen as a radical peace experiment. This latter campaign attempted to supply food, under Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

supervision, to civilians in occupied Europe. From 1941, the PPU campaigned against the bombing of German civilians and was one of several groups to back the Bombing Restriction Committee (most of whose members were not pacifists or even opposed to the war as a whole). The Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

branch of the PPU declared, "We pacifists, while determined to resist the Nazi system, believe that nothing can justify the continuation of this slaughter and the moral degradation that it involves". Throughout the war, Vera Brittain published a newsletter, ''Letters to Peace Lovers'', criticizing the conduct of the war, including the bombing of civilian areas of Germany. This had 2,000 subscribers.

By 1945, membership of the PPU had fallen by more than a quarter, standing at 98,414 when the war ended (compared to around 140,000 in 1940).

After the Second World War

Since 1945, the PPU has consistently "condemned the violence, oppression and weapons of all belligerents". Immediately after the war, there was a focus on support for famine relief in Europe and elsewhere. The PPU condemned the use of nuclear weapons against Japan in August 1945 and in October 1945, prominent PPU members were among the signatories to an open letter asking what the moral difference was between mass killing by Nazis in concentration camps and mass killings by atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This was followed by the publication of the PPU leaflet ''Atom War''. In 1947, the PPU voted to make a priority of campaigning for the abolition of conscription (known in law as National Service). Conscription in the UK was phased out from 1960 and ended completely in 1963. In the 1950s, the PPU paid more attention to ideas of nonviolent civil disobedience, as developed by Mohandas Gandhi and others. This was not without controversy even within the PPU, with some members resigning as they objected to the use, or what they saw as the too frequent use, of methods of civil disobedience. However, members of PPU were well represented in the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (DAC) founded in 1957, which organised the first of the Aldermaston marches in 1958. In practice, however, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the PPU lost some members to theCampaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucl ...

, even though CND was not a pacifist-only organisation and, at least in its early days, was less focused on direct action.

Some recovery in the PPU's fortunes took place after 1965, when Myrtle Solomon was general secretary. The PPU organised protests against the US war in Vietnam and handed out leaflets to US tourists in Britain stating "not only are Vietnamese being killed, but American men are dying for a cause war cannot achieve". The PPU also opposed the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

and condemned both the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands and the British response. It has also promoted the ideas of pacifist thinkers such as Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

, Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

, and Richard B. Gregg.

The group had a branch in Northern Ireland, the Peace Pledge Union in Northern Ireland; in the 1970s this group campaigned for the withdrawal of the British army, as well as the disbandment of both Republican and Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

paramilitary groups.

The Peace Pledge Union's 21st-century activity has included taking part in British protests against the 2003 Iraq War. In 2005, the PPU released an educational CD-ROM

A CD-ROM (, compact disc read-only memory) is a type of read-only memory consisting of a pre-pressed optical compact disc that contains computer data storage, data computers can read, but not write or erase. Some CDs, called enhanced CDs, hold b ...

on Martin Luther King's life and work that was adopted by several British schools. In recent years, the PPU has focused on issues including Remembrance Day, peace education, the commemoration of World War One and what they describe as the "militarisation" of British society.

White poppy campaign

The PPU's most visible contemporary activity is the White Poppy appeal, started in 1933 by the Women's Co-operative Guild alongside the Royal British Legion's red poppy appeal. The white poppy commemorated not only British soldiers killed in war, but also civilian victims on all sides, standing as "a pledge to peace that war must not happen again". In 1986,

The PPU's most visible contemporary activity is the White Poppy appeal, started in 1933 by the Women's Co-operative Guild alongside the Royal British Legion's red poppy appeal. The white poppy commemorated not only British soldiers killed in war, but also civilian victims on all sides, standing as "a pledge to peace that war must not happen again". In 1986, Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

expressed her "deep distaste" for the white poppies, on allegations that they potentially diverted donations from service men, yet this stance gave them increased publicity. In the 2010s, sales of white poppies rose. The PPU reported that around 110,000 white poppies had been bought in 2015, the highest number on record.

Notable members

Members of the PPU have included:Vera Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain (29 December 1893 – 29 March 1970) was an English Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse, writer, feminist, socialist and pacifist. Her best-selling 1933 memoir '' Testament of Youth'' recounted her experiences during the Fir ...

, Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

, Clifford Curzon

Sir Clifford Michael Curzon CBE (né Siegenberg; 18 May 19071 September 1982) was an English classical pianist.

Curzon studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London, and subsequently with Artur Schnabel in Berlin and Wanda Landowska and ...

, Alex Comfort

Alexander Comfort (10 February 1920 – 26 March 2000) was a British scientist and physician, writer and activist, known best for his nonfiction sex manual, '' The Joy of Sex'' (1972). He was a poet and author of both fiction and nonficti ...

, Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as "the greatest artist-craftsma ...

, Ben Greene, Laurence Housman

Laurence Housman (; 18 July 1865 – 20 February 1959) was an English playwright, writer and illustrator whose career stretched from the 1890s to the 1950s. He studied art in London and worked largely as an illustrator during the first years o ...

, Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley ( ; 26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. His bibliography spans nearly 50 books, including non-fiction novel, non-fiction works, as well as essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the ...

, George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1 ...

, Kathleen Lonsdale, Reginald Sorensen, George MacLeod, Sybil Morrison, John Middleton Murry

John Middleton Murry (6 August 1889 – 12 March 1957) was an English writer. He was a prolific author, producing more than 60 books and thousands of essays and reviews on literature, social issues, politics, and religion during his lifetime. ...

, Peter Pears

Sir Peter Neville Luard Pears ( ; 22 June 19103 April 1986) was an English tenor. His career was closely associated with the composer Benjamin Britten, his personal and professional partner for nearly forty years.

Pears' musical career started ...

, Max Plowman, Arthur Ponsonby, Hugh S. Roberton, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World ...

, Myrtle Solomon, Donald Soper

Donald Oliver Soper, Baron Soper (31 January 1903 – 22 December 1998) was a British Methodist minister, socialist and pacifist. He served as President of the Methodist Conference in 1953–54. After May 1965 he was a peer in the House of Lo ...

, Sybil Thorndike

Dame Agnes Sybil Thorndike, Lady Casson (24 October 18829 June 1976) was an English actress whose stage career lasted from 1904 to 1969.

Trained in her youth as a concert pianist, Thorndike turned to the stage when a medical problem with her h ...

, Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (2 January 1905 – 8 January 1998) was an English composer who rose to prominence during and immediately after the Second World War. In his lifetime he was sometimes ranked with his contemporary Benjamin Britten as o ...

and Wilfred Wellock.

See also

* Conscience: Taxes for Peace not War * List of anti-war organisations *List of peace activists

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated Diplomacy, diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usua ...

* Parliament Square Peace Campaign

* Peace News

*Peace symbols

A number of peace symbols have been used many ways in various cultures and contexts. The dove and olive branch was used symbolically by early Christians and then eventually became a secular peace symbol, popularized by a ''Dove'' lithograph ...

References

Further reading

*External links

*About Dick Sheppard

on the PPU website {{Authority control 1934 establishments in the United Kingdom Organizations established in 1934 Organisations based in the London Borough of Camden Peace organisations based in the United Kingdom Conscientious objection organizations