Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American

bass-baritone

A bass-baritone is a high-lying bass or low-lying "classical" baritone voice type which shares certain qualities with the true baritone voice. The term arose in the late 19th century to describe the particular type of voice required to sing three ...

concert artist, actor, professional

football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for his political stances.

In 1915, Robeson won an academic scholarship to

Rutgers College

Rutgers University ( ), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of three campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College and was aff ...

in

New Brunswick, New Jersey

New Brunswick is a city (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Middlesex County, New Jersey, Middlesex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[All-American

The All-America designation is an annual honor bestowed on outstanding athletes in the United States who are considered to be among the best athletes in their respective sport. Individuals receiving this distinction are typically added to an Al ...]

in football and was elected class valedictorian. He earned his LL.B. from

Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (CLS) is the Law school in the United States, law school of Columbia University, a Private university, private Ivy League university in New York City.

The school was founded in 1858 as the Columbia College Law School. The un ...

, while playing in the

National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a Professional gridiron football, professional American football league in the United States. Composed of 32 teams, it is divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National ...

(NFL). After graduation, he became a figure in the

Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the ti ...

, with performances in

Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of Realism (theatre), realism, earlier associated with ...

's ''

The Emperor Jones'' and ''

All God's Chillun Got Wings''.

Robeson performed in Britain in a touring melodrama, ''Voodoo'', in 1922, and in ''Emperor Jones'' in 1925. In 1928, he scored a major success in the London premiere of ''

Show Boat

''Show Boat'' is a musical theatre, musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 Show Boat (novel), novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the per ...

''. Living in London for several years with his wife

Eslanda, Robeson continued to establish himself as a concert artist and starred in a London production of ''

Othello

''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'', often shortened to ''Othello'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare around 1603. Set in Venice and Cyprus, the play depicts the Moorish military commander Othello as he is manipulat ...

'', the first of three productions of the play over the course of his career. He also gained attention in ''

Sanders of the River'' (1935) and in the film production of ''

Show Boat

''Show Boat'' is a musical theatre, musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 Show Boat (novel), novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the per ...

'' (1936). Robeson's political activities began with his involvement with unemployed workers and anti-imperialist students in Britain, and it continued with his support for the

Republican cause during the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

and his involvement in the

Council on African Affairs.

After returning to the United States in 1939, Robeson supported the American and Allied war efforts during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. His history of supporting civil rights causes and Soviet policies, however, brought scrutiny from the

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

(FBI). After the war ended, the Council on African Affairs was placed on the

Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations The United States Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO) was a list drawn up on April 3, 1947 at the request of the United States Attorney General (and later Supreme Court justice) Tom C. Clark. The list was intended to be a co ...

. Robeson was investigated during the

McCarthy era. When he refused to recant his public advocacy of his political beliefs, the

U.S. State Department withdrew his passport and his income plummeted. He moved to

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

and published a periodical called

''Freedom'', which was critical of United States policies, from 1950 to 1955. Robeson's right to travel was eventually restored as a result of the 1958

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

decision ''

Kent v. Dulles''.

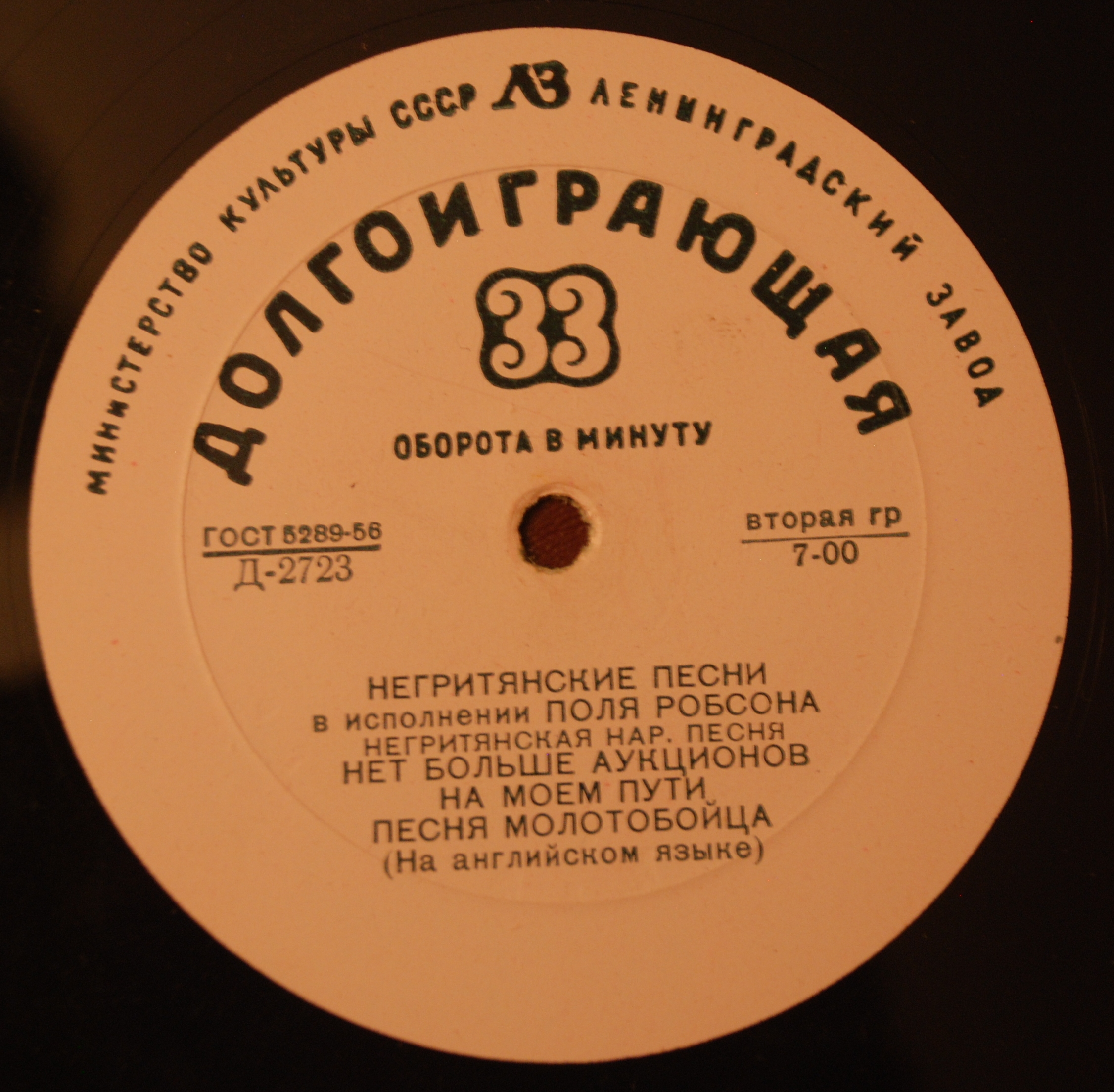

Between 1925 and 1961, Robeson released recordings of some 276 songs. The first of these was the

spiritual "

Steal Away", backed with "

Were You There", in 1925. Robeson's recorded repertoire spanned many styles, including Americana, popular standards, classical music, European folk songs, political songs, poetry and spoken excerpts from plays.

Early life

1898–1915: Childhood

Robeson was born in

Princeton, New Jersey

The Municipality of Princeton is a Borough (New Jersey), borough in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton, New Jersey, Borough of Princeton and Pri ...

, in 1898, to Reverend

William Drew Robeson and

Maria Louisa Bustill

Maria Louisa Bustill Robeson (November 8, 1853 – January 20, 1904) was a Quaker schoolteacher; the wife of the Reverend William Drew Robeson of Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in Princeton, New Jersey and the mother of Paul Robeson ...

.

[; cf. , ] His mother, Maria, was a member of the

Bustills, a prominent

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

family of mixed ancestry. His father, William, was of

Igbo origin and was born into slavery.

William escaped from a

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

in his teens and eventually became the minister of Princeton's Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in 1881. Robeson had three brothers: William Drew Jr. (born 1881), Reeve (born ), and Ben (born ); and one sister, Marian (born ).

In 1900, a disagreement between William and white financial supporters of the Witherspoon church arose with apparent racial undertones, which were prevalent in Princeton. William, who had the support of his entirely black congregation, resigned in 1901. The loss of his position forced him to work menial jobs. Three years later when Robeson was six, his mother, who was nearly blind, died in a house fire. Eventually, William became financially incapable of providing a house for himself and his children still living at home, Ben and Paul, so they moved into the attic of a store in Westfield, New Jersey.

William found a stable parsonage at the St. Thomas

A.M.E. Zion in 1910, where Robeson filled in for his father during sermons when he was called away. In 1912, Robeson began attending

Somerville High School in New Jersey, where he performed in ''

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

'' and ''

Othello

''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'', often shortened to ''Othello'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare around 1603. Set in Venice and Cyprus, the play depicts the Moorish military commander Othello as he is manipulat ...

'', sang in the chorus, and excelled in football, basketball, baseball and track. His athletic dominance elicited racial taunts which he ignored. Prior to his graduation, he won a statewide academic contest for a scholarship to Rutgers and was named class valedictorian. He took a summer job as a waiter in

Narragansett Pier, Rhode Island, where he befriended

Fritz Pollard

Frederick Douglass "Fritz" Pollard (January 27, 1894 – May 11, 1986) was an American professional football player and coach. In 1921, he became the first African-American head coach in the National Football League (NFL). Pollard and Bobby Mar ...

, later to be the first African-American coach in the National Football League.

1915–1919: Rutgers College

In late 1915, Robeson became the third African-American student ever enrolled at Rutgers, and the only one at the time. He tried out for the

Rutgers Scarlet Knights football

The Rutgers Scarlet Knights football program represents Rutgers University in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) of the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA). Rutgers competes as a member of the Big Ten Conference. Prior to joining t ...

team, and his resolve to make the squad was tested as his teammates engaged in excessive play, during which his nose was broken and his shoulder dislocated. The coach,

Foster Sanford, decided he had overcome the provocation and announced that he had made the team.

[; cf. , , ]

Robeson joined the debating team and he sang off-campus for spending money, and on-campus with the

Glee Club

A glee club is a musical group or choir group, historically of male voices but also of female or mixed voices, which traditionally specializes in the singing of short songs by trios or quartets. In the late 19th century it was very popular in ...

informally, as membership required attending all-white mixers. He also joined the other collegiate athletic teams. As a sophomore, amidst Rutgers' sesquicentennial celebration, he was benched when a Southern football team,

Washington and Lee University

Washington and Lee University (Washington and Lee or W&L) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lexington, Virginia, United States. Established in 1749 as Augusta Academy, it is among ...

, refused to take the field because the Scarlet Knights had fielded a Negro, Robeson.

After a standout junior year of football, he was recognized in ''

The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly M ...

'' for his athletic, academic, and singing talents.

[; cf. ] At this time his father fell grievously ill. Robeson took the sole responsibility in caring for him, shuttling between Rutgers and Somerville. His father, who was the "glory of his boyhood years" soon died, and at Rutgers, Robeson expounded on the incongruity of African Americans fighting to protect America in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

but not having the same opportunities in the United States as whites.

He finished university with four annual oratorical triumphs and

varsity letter

A varsity letter (or monogram) is an award earned in the United States for excellence in school activities. A varsity letter signifies that its recipient was a qualified varsity team member, awarded after a certain standard was met. A person who ...

s in multiple sports. His football playing as

end

End, END, Ending, or ENDS may refer to:

End Mathematics

*End (category theory)

* End (topology)

* End (graph theory)

* End (group theory) (a subcase of the previous)

* End (endomorphism) Sports and games

*End (gridiron football)

*End, a division ...

won him first-team All-American selection, in both his junior and senior years.

Walter Camp

Walter Chauncey Camp (April 7, 1859 – March 14, 1925) was an American college football player and coach, and sports writer known as the "Father of American Football". Among a long list of inventions, he created the sport's line of scrimmage a ...

considered him the greatest end ever. Academically, he was accepted into

Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

and

Cap and Skull. His classmates recognized him by electing him class valedictorian. ''

The Daily Targum

''The Daily Targum'' is the official student newspaper of Rutgers University. Founded in 1867, it is the second-oldest collegiate newspaper in the United States. The ''Daily Targum'' is student written and managed, and boasts a circulation of ...

'' published a poem featuring his achievements. In his valedictory speech, he exhorted his classmates to work for equality for all Americans. At Rutgers, Robeson also gained a reputation for his singing, having a deep rich voice which some saw as bass with a high range, others as baritone with low notes. Throughout his career, Robeson was classified as a bass-baritone.

1919–1923: Columbia Law School and marriage

Robeson entered New York University School of Law in fall 1919. To support himself, he became an assistant football coach at

Lincoln University, where he joined the

Alpha Phi Alpha

Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. () is the oldest intercollegiate List of African-American fraternities, historically African American Fraternities and sororities, fraternity. It was initially a literary and social studies club organized in the ...

fraternity. However, Robeson felt uncomfortable at NYU and moved to

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

and transferred to Columbia Law School in February 1920. Already known in the black community for his singing, he was selected to perform at the dedication of the

Harlem YWCA.

Robeson began dating

Eslanda "Essie" Goode and after her coaxing, he made his theatrical debut as Simon in

Ridgely Torrence's ''

Simon the Cyrenian''. After a year of courtship, they were married in August 1921.

Robeson was recruited by Fritz Pollard to play for the NFL's

Akron Pros

The Akron Pros were a professional American football, football team that played in Akron, Ohio, Akron, Ohio from 1908 to 1926. The team originated in 1908 as a semi-professional, semi-pro team named the Akron Indians, but later became Akron Pros ...

while he continued his law studies. In the spring of 1922, Robeson postponed school to portray Jim in

Mary Hoyt Wiborg's play ''

Taboo

A taboo is a social group's ban, prohibition or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, offensive, sacred or allowed only for certain people.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

''. He then sang in the chorus of an

Off-Broadway

An off-Broadway theatre is any professional theatre venue in New York City with a seating capacity between 100 and 499, inclusive. These theatres are smaller than Broadway theatres, but larger than off-off-Broadway theatres, which seat fewer tha ...

production of ''

Shuffle Along'' before he joined ''Taboo'' in Britain. The play was adapted by

Mrs Patrick Campbell

Beatrice Rose Stella Tanner (9 February 1865 – 9 April 1940), better known by her stage name Mrs Patrick Campbell or Mrs Pat, was an English stage actress, best known for appearing in plays by Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Shaw and J. M. ...

to highlight his singing. After the play's run ended, he befriended

Lawrence Benjamin Brown, a classically trained musician, before returning to Columbia while playing for the NFL's

Milwaukee Badgers

The Milwaukee Badgers were a professional American football team, based in Milwaukee, that played in the National Football League from 1922 to 1926. The team played its home games at Athletic Park, later known as Borchert Field, on Milwaukee ...

. He ended his football career after the 1922 season, and graduated from Columbia Law School in 1923.

Theatrical success and ideological transformation

1923–1927: Harlem Renaissance

Robeson briefly worked as a lawyer, but he renounced a career in law because of

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

. His wife supported them financially. She was the head

histological chemist in Surgical Pathology at

New York-Presbyterian Hospital

The NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital (abbreviated as NYP) is a nonprofit academic medical center in New York City. It is the primary teaching hospital for Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. The hospit ...

. She continued to work there until 1925 when his career took off.

They frequented the social functions at the future

Schomburg Center

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is a research library of the New York Public Library (NYPL) and an archive repository for information on people of African descent worldwide. Located at 515 Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) be ...

. In December 1924 he landed the lead role of Jim in

Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of Realism (theatre), realism, earlier associated with ...

's ''

All God's Chillun Got Wings'', which culminated with Jim metaphorically consummating his marriage with his white wife by symbolically emasculating himself. ''Chillun's'' opening was postponed due to nationwide controversy over its plot.

''Chillun's'' delay led to a revival of ''

The Emperor Jones'' with Robeson as Brutus, a role pioneered by

Charles Sidney Gilpin. The role terrified and galvanized Robeson, as it was practically a 90-minute soliloquy. Reviews declared him an unequivocal success. Though arguably clouded by its controversial subject, his Jim in ''Chillun'' was less well received. He answered criticism of its plot by writing that fate had drawn him to the "untrodden path" of drama, that the true measure of a culture is in its artistic contributions, and that the only true American culture was African-American.

The success of his acting placed him in elite social circles and his rise to fame, which was forcefully aided by Essie, had happened very rapidly. Essie's ambition for Robeson was a startling dichotomy to his indifference. She quit her job, became his agent, and negotiated his first movie role in a silent

race film

The race film or race movie was a genre of film produced in the United States between about 1915 and the early 1950s, consisting of films produced for African American, black audiences, and featuring black casts. Approximately five hundred race ...

directed by

Oscar Micheaux

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux (; January 2, 1884 – March 25, 1951) was an American author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and c ...

, ''

Body and Soul'' (1925). To support a charity for single mothers, Robeson headlined a concert singing

spirituals

Spirituals (also known as Negro spirituals, African American spirituals, Black spirituals, or spiritual music) is a genre of Christian music that is associated with African Americans, which merged varied African cultural influences with the exp ...

. He performed his repertoire of spirituals on the radio.

Lawrence Benjamin Brown, who had become renowned while touring as a pianist with gospel singer

Roland Hayes, chanced upon Robeson in Harlem. The two ad-libbed a set of spirituals, with Robeson as lead and Brown as accompanist. This so enthralled them that they booked

Provincetown Playhouse

The Provincetown Playhouse is a historic theatre at 133 MacDougal Street between West 3rd and 4th streets in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It is named for the Provincetown Players, who converted the forme ...

for a concert. The pair's rendition of African-American folk songs and spirituals was captivating, and

Victor Records

The Victor Talking Machine Company was an American recording company and phonograph manufacturer, incorporated in 1901. Victor was an independent enterprise until 1929 when it was purchased by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and became ...

signed Robeson to a contract in September 1925.

The Robesons went to London for a revival of ''The Emperor Jones'', before spending the rest of the fall on holiday on the French Riviera, socializing with

Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris in 1903, and ...

and

Claude McKay

Festus Claudius "Claude" McKay OJ (September 15, 1890See Wayne F. Cooper, ''Claude McKay, Rebel Sojourner In The Harlem Renaissance'' (New York, Schocken, 1987) p. 377 n. 19. As Cooper's authoritative biography explains, McKay's family predate ...

. Robeson and Brown performed a series of concert tours in America from January 1926 until May 1927.

During a hiatus in New York, Robeson learned that Essie was several months pregnant.

Paul Robeson Jr. was born in November 1927 in New York, while Robeson and Brown toured Europe. Essie experienced complications from the birth, and by mid-December, her health had deteriorated dramatically. Ignoring Essie's objections, her mother wired Robeson and he immediately returned to her bedside. Essie completely recovered after a few months.

1928–1932: ''Show Boat'', ''Othello'', and marriage difficulties

In 1928, Robeson played "Joe" in the London production of the American musical ''

Show Boat

''Show Boat'' is a musical theatre, musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 Show Boat (novel), novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the per ...

'', at the

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and listed building, Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) an ...

. His rendition of "

Ol' Man River

"Ol' Man River" is a show tune from the 1927 musical '' Show Boat'' with music by Jerome Kern and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, who wrote the song in 1925. The song contrasts the struggles and hardships of African Americans with the endless, ...

" became the benchmark for all future performers of the song. Some black critics objected to the play due to its usage of the then-common racial epithet "

nigger

In the English language, ''nigger'' is a racial slur directed at black people. Starting in the 1990s, references to ''nigger'' have been increasingly replaced by the euphemistic contraction , notably in cases where ''nigger'' is Use–menti ...

". It was, nonetheless, immensely popular with white audiences. He was summoned for a

Royal Command Performance

A Royal Command Performance is any performance by actors or musicians that occurs at the direction or request of a reigning monarch of the United Kingdom.

Although English monarchs have long sponsored their own theatrical companies and commis ...

at

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

and Robeson was befriended by

Members of Parliament from the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. ''Show Boat'' continued for 350 performances and, as of 2001, it remained the Royal's most profitable venture. The Robesons bought a home in

Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, England, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, located mainly in the London Borough of Camden, with a small part in the London Borough of Barnet. It borders Highgate and Golders Green to the north, Belsiz ...

. He reflected on his life in his diary and wrote that it was all part of a "higher plan" and "God watches over me and guides me. He's with me and lets me fight my own battles and hopes I'll win." However, an incident at the

Savoy Grill, in which he was refused seating, caused him to issue a press release describing the insult which subsequently became a matter of public debate.

Essie had learned early in their marriage that Robeson had extramarital affairs, but she tolerated them. However, when she discovered that he was having another affair, she unfavorably altered the characterization of him in his biography, and defamed him by describing him with "negative racial stereotypes". Despite her uncovering of this tryst, there was no public evidence that their relationship had soured.

The couple appeared in the experimental Swiss film ''

Borderline'' (1930). He then returned to the

Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy ...

, in London's

West End to play ''Othello'', opposite

Peggy Ashcroft

Dame Edith Margaret Emily "Peggy" Ashcroft (22 December 1907 – 14 June 1991) was an English actress whose career spanned more than 60 years.

Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Ashcroft was determined from an early age to become ...

as

Desdemona

Desdemona () is a character in William Shakespeare's play ''Othello'' (c. 1601–1604). Shakespeare's Desdemona is a Venice, Italy, Venetian beauty who enrages and disappoints her father, a Venetian senator, when she elopes with Othello (char ...

. He cited the lack of a "racial problem" in London as significant in his decision to move to London. Robeson was the first black actor to play

Othello

''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'', often shortened to ''Othello'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare around 1603. Set in Venice and Cyprus, the play depicts the Moorish military commander Othello as he is manipulat ...

in Britain since

Ira Aldridge

Ira Frederick Aldridge (July 24, 1807 – August 7, 1867) was an American-born British actor, playwright, and theatre manager, known for his portrayal of William Shakespeare, Shakespearean characters. James Hewlett (actor), James Hewlett and Ald ...

. The production received mixed reviews which noted Robeson's "highly civilized quality

ut lacking thegrand style". Robeson stated the best way to diminish the oppression African Americans faced was for his artistic work to be an example of what "men of my colour" could accomplish rather than to "be a propagandist and make speeches and write articles about what they call the Colour Question."

After Essie discovered Robeson had been having an affair with Ashcroft, she decided to seek a divorce and they split up. While working in London, Robeson became one of the first artists to record at the new EMI Recording Studios (later known as

Abbey Road Studios

Abbey Road Studios (formerly EMI Recording Studios) is a music recording studio at 3 Abbey Road, London, Abbey Road, St John's Wood, City of Westminster, London. It was established in November 1931 by the Gramophone Company, a predecessor of ...

), recording four songs in September 1931, almost two months before the studio was officially opened. Robeson returned to Broadway as Joe in the 1932 revival of ''Show Boat'', with

Maude Simmons and others, to critical and popular acclaim. He received, with immense pride, an honorary master's degree from Rutgers. It is said that Foster Sanford, his college football coach advised him that divorcing Essie and marrying Ashcroft would do irreparable damage to his reputation. In any case, Ashcroft and Robeson's relationship ended in 1932, and Robeson and Essie reconciled, leaving their relationship scarred permanently.

1933–1937: Ideological awakening

In 1933, Robeson played the role of Jim in the London production of ''Chillun'', virtually gratis, then returned to the United States to star as Brutus in the film

''The Emperor Jones''the first film to feature an African American in a starring role, "a feat not repeated for more than two decades in the U.S."

[; cf. ; ] His acting in ''The Emperor Jones'' was well received.

On the film set he rejected any slight to his dignity, despite the widespread

Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

atmosphere in the United States. Upon returning to England, he publicly criticized

African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

' rejection of

their own culture. Despite negative reactions from the press, such as a ''

New York Amsterdam News'' retort that Robeson had made a "jolly well

ss of himself, he also announced that he would reject any offers to perform central European (though not Russian, which he considered "Asiatic") opera because the music had no connection to his heritage.

In early 1934, Robeson enrolled in the

School of Oriental and African Studies

The School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS University of London; ) is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the federal University of London. Founded in 1916, SOAS is located in the Bloomsbury area ...

, a constituent college of the

University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

, where he studied

phonetics

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds or, in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians ...

and

Swahili. His "sudden interest" in

African history and its influence on culture coincided with his essay "I Want to be African", wherein he wrote of his desire to embrace his ancestry.

His friends in the

anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influenc ...

movement and his association with

British socialists

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and cultur ...

led him to visit the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Robeson, Essie, and

Marie Seton traveled to the Soviet Union on an invitation from

Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein; (11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, screenwriter, film editor and film theorist. Considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, he was a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is no ...

in December 1934. A stopover in Berlin enlightened Robeson to the

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

in

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and, on his arrival in

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, in the Soviet Union, Robeson said, "Here I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life ... I walk in full human dignity."

He undertook the role of Bosambo in the movie ''

Sanders of the River'' (1935), which he felt would render a realistic view of

colonial African culture. ''Sanders of the River'' made Robeson an international movie star; but the stereotypical portrayal of a colonial African was seen as embarrassing to his stature as an artist and damaging to his reputation. The Commissioner of Nigeria to London protested the film as slanderous to his country, and Robeson thereafter became more politically conscious in his choice of roles. He appeared in the play ''Stevedore'' at the

Embassy Theatre in London in May 1935, which was favorably reviewed in ''

The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly M ...

'' by

Nancy Cunard

Nancy Clara Cunard (10 March 1896 – 17 March 1965) was a British writer, heiress and political activist. She was born into the British upper class, and devoted much of her life to fighting racism and fascism. She became a muse to some of the ...

, who concluded: "''Stevedore'' is extremely valuable in the racialsocial questionit is straight from the shoulder". In early 1936, he decided to send his son to school in the Soviet Union to shield him from racist attitudes. He then played the role of

Toussaint Louverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (, ) also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda (20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803), was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louvertu ...

in the

eponymous play by

C. L. R. James at the

Westminster Theatre, and appeared in the films ''

Song of Freedom'', and ''

Show Boat

''Show Boat'' is a musical theatre, musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 Show Boat (novel), novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the per ...

'' in 1936, and ''My Song Goes Forth'', ''

King Solomon's Mines

''King Solomon's Mines'' is an 1885 popular fiction, popular novel by the English Victorian literature, Victorian adventure writer and fable, fabulist Sir H. Rider Haggard. Published by Cassell and Company, it tells of an expedition through an ...

''. and ''

Big Fella'', all in 1937. In 1938, he was named by American ''

Motion Picture Herald

The ''Motion Picture Herald'' (MPH) was an American film industry trade paper first published as the ''Exhibitors Herald'' in 1915, and MPH from 1931 to December 1972.Anthony Slide, ed. (1985)''International Film, Radio, and Television Journals ...

'' as the 10th most popular star in British cinema.

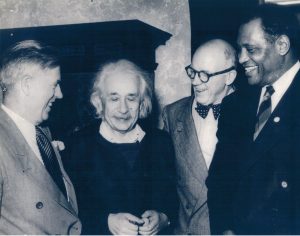

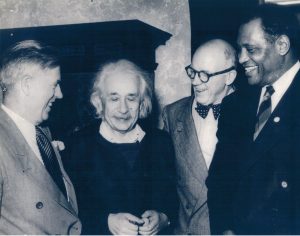

In 1935, Robeson met

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

when Einstein came backstage after Robeson's concert at the

McCarter Theatre. The two discovered that, as well as a mutual passion for music, they shared a hatred for

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

. The friendship between Robeson and Einstein lasted nearly twenty years, but was not well known or publicized.

1937–1939: Spanish Civil War and political activism

Robeson believed that the struggle against fascism during the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

was a turning point in his life and transformed him into a political activist. In 1937, he used his concert performances to advocate the

Republican cause and the war's refugees. He permanently modified his renditions of "Ol' Man River" – initially, by singing the word "darkies" instead of "niggers"; later, by changing some of the stereotypical dialect in the lyrics to standard English and replacing the fatalistic last verse ("Ah gits weary / An' sick of tryin' / Ah'm tired of livin' / An skeered of dyin) with an uplifting verse of his own ("But I keep laffin' / Instead of cryin' / I must keep fightin' / Until I'm dyin) – transforming it from a tragic "song of resignation with a hint of protest implied" into a battle hymn of unwavering defiance. His business agent expressed concern about his political involvement, but Robeson overruled him and decided that contemporary events trumped commercialism. In

Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, he commemorated the Welsh people killed while fighting for the Republicans, where he recorded a message that became his epitaph: "The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative."

After an invitation from

J. B. S. Haldane, he traveled to Spain in 1938 because he believed in the

International Brigades

The International Brigades () were soldiers recruited and organized by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front (Spain), Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The International Bri ...

's cause, visited the hospital of

Benicàssim, singing to the wounded soldiers. Robeson also visited the battlefront and provided a morale boost to the Republicans at a time when their victory was unlikely. Back in England, he hosted

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

to support

Indian independence, whereat Nehru expounded on imperialism's affiliation with Fascism. Robeson reevaluated the direction of his career and decided to focus on the ordeals of "common people". He appeared in the pro-labor play ''Plant in the Sun'', in which he played an Irishman, his first "white" role. With

Max Yergan, and the

International Committee on African Affairs (later known as the

Council on African Affairs), Robeson became an advocate for African nationalism and political independence.

Paul Robeson was living in Britain until the start of the Second World War in 1939. His name was included in the ''

Sonderfahndungsliste G.B.'' as a target for arrest if Germany had occupied Britain.

World War II, the Broadway ''Othello'', political activism, and McCarthyism

1939–1945: World War II, and the Broadway ''Othello''

Robeson's last British film was ''

The Proud Valley'' (1940), set in a Welsh coal-mining town. The film was still being shot when Hitler's invasion of Poland led to England's declaration of war at the beginning of September 1939; several weeks later, just after the completion of filming, Robeson and his family returned to the United States, arriving in New York in October 1939. They lived at first in the

Sugar Hill neighborhood of Harlem, and in 1941 settled in

Enfield, Connecticut

Enfield is a New England town, town in Hartford County, Connecticut, United States, first settled by John and Robert Pease of Salem, Massachusetts Bay Colony. The town is part of the Capitol Planning Region, Connecticut, Capitol Planning Region. ...

.

After his well-received performance of ''

Ballad for Americans'' on a live CBS radio broadcast on November 5, with a repeat performance on New Year's Day 1940, the song became a popular seller. In 1940, the magazine ''

Collier's

}

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter F. Collier, Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened i ...

'' named Robeson America's "no. 1 entertainer". Nevertheless, during a tour in 1940, the Beverly Wilshire Hotel was the only major Los Angeles hotel willing to accommodate him due to his race, at an exorbitant rate and registered under an assumed name, and he therefore dedicated two hours every afternoon to sitting in the lobby, where he was widely recognised, "to ensure that the next time Black come through, they'll have a place to stay." Los Angeles hotels lifted their restrictions on black guests soon afterwards.

Robeson narrated the 1942 documentary ''

Native Land'' which was labeled by the FBI as communist propaganda. After an appearance in ''

Tales of Manhattan'' (1942), a production which he felt was "very offensive to my people" due to the

way the segment was handled in stereotypes, he announced that he would no longer act in films because of the demeaning roles available to blacks.

According to

democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing economic and political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-mana ...

writer Barry Finger's critical appraisal of Robeson, while the

Hitler-Stalin pact was still in effect, Robeson counseled American blacks that they had no stake in the rivalry of

European powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

. Once Russia was attacked, he urged blacks to support the war effort, now warning that an Allied defeat would "make slaves of us all."

[Barry Finger]

"Paul Robeson: A Flawed Martyr"

, in: '' New Politics'', vol. 7, no. 1 (Summer 1998). Robeson participated in benefit concerts on behalf of the war effort and at a concert at the

Polo Grounds

The Polo Grounds was the name of three stadiums in Upper Manhattan, New York City, used mainly for professional baseball and American football from 1880 to 1963. The original Polo Grounds, opened in 1876 and demolished in 1889, was built for the ...

, he met two emissaries from the

Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, abbreviated as JAC, was an organization that was created in the Soviet Union during World War II to influence international public opinion and organize political and material support for the Soviet fight against ...

,

Solomon Mikhoels

Solomon (Shloyme) Mikhoels ( lso spelled שלוימע מיכאעלס during the Soviet era , – 13 January 1948) was a Soviet actor and the artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater. Mikhoels served as the chairman of the Jewish ...

and

Itzik Feffer. Subsequently, Robeson reprised the role of Othello at the

Shubert Theatre in 1943, and became the first African American to play the role with a white supporting cast on

Broadway. The production was a success, running for 296 performances on Broadway (a record for a Shakespeare production on Broadway that still stands), and winning for Robeson the first

Donaldson Award for Best Actor in a Play. During the same period, he addressed a meeting with

Commissioner

A commissioner (commonly abbreviated as Comm'r) is, in principle, a member of a commission or an individual who has been given a commission (official charge or authority to do something).

In practice, the title of commissioner has evolved to incl ...

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (; November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a United States federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of Baseball, commissioner of baseball from 1920 until his death. ...

and team owners in a failed attempt to convince them to admit black players to

Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball league composed of 30 teams, divided equally between the National League (baseball), National League (NL) and the American League (AL), with 29 in the United States and 1 in Canada. MLB i ...

. He toured North America with ''Othello'' until 1945, and subsequently, his political efforts with the Council on African Affairs to get colonial powers to discontinue their exploitation of Africa were short-circuited by the United Nations.

During this period, Robeson also developed a sympathy for the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

's side in the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

. In 1940, the Chinese progressive activist,

Liu Liangmo taught Robeson the patriotic song "''Chee Lai!"'' ("Arise!"), known as the

March of the Volunteers

The "March of the Volunteers", originally titled the "March of the Anti-Manchukuo Counter-Japan Volunteers", is the official national anthem of the People's Republic of China since 1978. Unlike historical Chinese anthems, previous Chinese stat ...

.

Robeson premiered the song at a concert in New York City's

Lewisohn Stadium

Lewisohn Stadium was an amphitheater and athletic facility built on the campus of the City College of New York (CCNY). It opened in 1915 and was demolished in 1973.

History

The Doric-colonnaded amphitheater was built between Amsterdam and Conv ...

[ and recorded it in both English and Chinese for Keynote Records in early 1941.][ Robeson gave further performances at benefit concerts for the China Aid Council and United China Relief at Washington's Uline Arena on April 24, 1941.]Daughters of the American Revolution

The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (often abbreviated as DAR or NSDAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a patriot of the American Revolutionary War.

A non-p ...

owing to Robeson's race.Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

and Hu Shih

Hu Shih ( zh, t=胡適; 17 December 189124 February 1962) was a Chinese academic, writer, and politician. Hu contributed to Chinese liberalism and language reform, and was a leading advocate for the use of written vernacular Chinese. He part ...

, the Chinese ambassador, became sponsors. However, when the organizers offered tickets on generous terms to the National Negro Congress

In African-American history, the National Negro Congress (NNC; 1936–ca. 1946) was an African-American organization formed in 1936 at Howard University as a broadly based coalition organization with the goal of fighting for Black liberation; it ...

to help fill the larger venue, both sponsors withdrew, objecting to the NNC's Communist ties.

Robeson opposed the U.S. support for Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

in China, and denounced U.S. support for Chiang at political events over the course of 1945–1946, including the World Peace Conference and the National Peace Commission.anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

focus and blockade of the Communist guerrilla army meant that China was fighting Japan "with one hand tied behind its back".People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

's National Anthem after 1949. Its Chinese lyricist, Tian Han

Tian Han ( zh, 田汉; 12 March 1898 – 10 December 1968), formerly romanized as T'ien Han, was a Chinese drama activist, playwright, a leader of revolutionary music and films, as well as a translator and poet. He emerged at the time of the ...

, died in a Beijing prison in 1968, but Robeson continued to send royalties to his family.[Liang Luo]

"International Avant-garde and the Chinese National Anthem: Tian Han, Joris Ivens, and Paul Robeson" in ''The Ivens Magazine'', No. 16

. European Foundation Joris Ivens (Nijmegen), October 2010. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

1946–1949: Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations

After the Moore's Ford lynchings of four African Americans in Georgia on July 25, 1946, Robeson met with President Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th Vice president of the United States, vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Frank ...

and admonished Truman by stating that if he did not enact legislation to end lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of i ...

, "the Negroes will defend themselves". Truman immediately terminated the meeting and declared that the time was not right to propose anti-lynching legislation. Subsequently, Robeson publicly called upon all Americans to demand that Congress pass civil rights legislation. Robeson founded the American Crusade Against Lynching organization in 1946. This organization was thought to be a threat to the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

antiviolence movement. Robeson received support from W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

on this matter and launched the organization on the anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

, September 23.

About this time, Robeson's belief that trade unionism

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

was crucial to civil rights became a mainstay of his political beliefs as he became a proponent of the union activist and Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

member Revels Cayton. Robeson was later called before the Tenney Committee where he responded to questions about his affiliation with the Communist Party USA by testifying that he was not a member of the party. Nevertheless, two organizations with which Robeson was intimately involved, the Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional L ...

and the Council on African Affairs, were placed on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations The United States Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO) was a list drawn up on April 3, 1947 at the request of the United States Attorney General (and later Supreme Court justice) Tom C. Clark. The list was intended to be a co ...

. Subsequently, he was summoned before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

, and when questioned about his affiliation with the Communist Party, he refused to answer, stating: "Some of the most brilliant and distinguished Americans are about to go to jail for the failure to answer that question, and I am going to join them, if necessary."[Bay Area Paul Robeson Centennial Committee, ]

Paul Robeson Chronology (Part 5)

''.

In 1948, Robeson was prominent in Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was the 33rd vice president of the United States, serving from 1941 to 1945, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He served as the 11th U.S. secretary of agriculture and the 10th U.S ...

's bid for the Presidency of the United States, during which Robeson traveled to the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, at risk to his own life, to campaign for him. In the ensuing year, Robeson was forced to go overseas to work because his concert performances were canceled at the FBI's behest. While on tour, he spoke at the World Peace Council

The World Peace Council (WPC) is an international organization created in 1949 by the Cominform and propped up by the Soviet Union. Throughout the Cold War, WPC engaged in propaganda efforts on behalf of the Soviet Union, whereby it criticize ...

. The Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

published a false transcript of his speech which gave the impression that Robeson had equated America with a Fascist state. In an interview, Robeson said the "danger of Fascism n the US

N, or n, is the fourteenth Letter (alphabet), letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages, and others worldwide. Its name in English is English alphab ...

has averted". Nevertheless, the speech publicly attributed to him was a catalyst for his being seen as an enemy of mainstream America. Robeson refused to bow to public criticism when he advocated in favor of twelve defendants, including his long-time friend, Benjamin J. Davis Jr., charged during the Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders

The Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders in New York City from 1949 to 1958 were the result of Federal government of the United States, US federal government prosecutions in the postwar period and during the Cold War between the Soviet Un ...

. Robeson traveled to Moscow in June 1949, and tried to find Itzik Feffer whom he had met during World War II. He let Soviet authorities know that he wanted to see him. Reluctant to lose Robeson as a propagandist for the Soviet Union, the Soviets brought Feffer from prison to him. Feffer told him that Mikhoels had been murdered, and predicted that he would be executed. To protect the Soviet Union's reputation, and to keep the right wing of the United States from gaining the moral high ground, Robeson denied that any persecution existed in the Soviet Union, and kept the meeting secret for the rest of his life, except from his son. On June 20, 1949, Robeson spoke at the saying that "We in America do not forget that it was on the backs of the white workers from Europe and on the backs of millions of Blacks that the wealth of America was built. And we are resolved to share it equally. We reject any hysterical raving that urges us to make war on anyone. Our will to fight for peace is strong. We shall not make war on anyone. We shall not make war on the Soviet Union. We oppose those who wish to build up imperialist Germany and to establish fascism in Greece. We wish peace with Franco's Spain despite her fascism. We shall support peace and friendship among all nations, with Soviet Russia and the people's Republics." He was blacklisted for saying this in the mainstream press within the United States, including in many periodicals of the Negro press such as ''The Crisis''.

In order to isolate Robeson politically,

Robeson traveled to Moscow in June 1949, and tried to find Itzik Feffer whom he had met during World War II. He let Soviet authorities know that he wanted to see him. Reluctant to lose Robeson as a propagandist for the Soviet Union, the Soviets brought Feffer from prison to him. Feffer told him that Mikhoels had been murdered, and predicted that he would be executed. To protect the Soviet Union's reputation, and to keep the right wing of the United States from gaining the moral high ground, Robeson denied that any persecution existed in the Soviet Union, and kept the meeting secret for the rest of his life, except from his son. On June 20, 1949, Robeson spoke at the saying that "We in America do not forget that it was on the backs of the white workers from Europe and on the backs of millions of Blacks that the wealth of America was built. And we are resolved to share it equally. We reject any hysterical raving that urges us to make war on anyone. Our will to fight for peace is strong. We shall not make war on anyone. We shall not make war on the Soviet Union. We oppose those who wish to build up imperialist Germany and to establish fascism in Greece. We wish peace with Franco's Spain despite her fascism. We shall support peace and friendship among all nations, with Soviet Russia and the people's Republics." He was blacklisted for saying this in the mainstream press within the United States, including in many periodicals of the Negro press such as ''The Crisis''.

In order to isolate Robeson politically,House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 19 ...

subpoenaed Jackie Robinson

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first Black American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the Baseball color line, ...

[; cf. ] to comment on Robeson's Paris speech.[; cf. ] Former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

noted, "Mr. Robeson does his people great harm in trying to line them up on the Communist side of hepolitical picture. Jackie Robinson helps them greatly by his forthright statements."

1950–1955: Blacklisted

In its review of Christy Walsh's massive 1949 reference, ''College Football and All America Review'', the ''Los Angeles Times'' praised it as "the most complete source of past gridiron scores, players, coaches, etc., yet published", but it failed to list Robeson as ever having played on the Rutgers team or ever having been an All-American. Months later, NBC canceled Robeson's appearance on Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

's television program, which furthered his erasure from public view.

Robeson opposed U.S. involvement in the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

and condemned America's nuclear threats against China.imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

purposes, and China's intervention in the Korean War was necessary to defend the security of millions of people in Asia.Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

.Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs ...

demanded that he return his passport.[ When Robeson met with State Department officials and asked why he was denied a passport, he was told that "his frequent criticism of the treatment of blacks in the United States should not be aired in foreign countries".

In 1950, Robeson co-founded, with ]W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

, a monthly newspaper, ''Freedom'', showcasing his views and those of his circle. Most issues had a column by Robeson, on the front page. In the final issue, July–August 1955, an unsigned column on the front page of the newspaper described the struggle for the restoration of his passport. It called for support from the leading African-American organizations, and asserted that "Negroes, ndall Americans who have breathed a sigh of relief at the easing of international tensions... have a stake in the Paul Robeson passport case". An article by Robeson appeared on the second page continuing the passport issue under the headline: "If Enough People Write Washington I'll Get My Passport in a Hurry."

In 1951, an article titled "Paul Robeson – the Lost Shepherd" was published in ''The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly M ...

'' and attributed to Robert Alan, although Paul Jr. suspected it was written by '' Amsterdam News'' columnist Earl Brown. J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

and the U.S. State Department arranged for the article to be printed and distributed in Africa in order to damage Robeson's reputation and reduce his popularity, and Communism's popularity, in colonial countries. Another article by Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was an American civil rights leader from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), ...

(now thought to have been the real author of "Paul Robeson – the Lost Shepherd") denounced Robeson as well as the CPUSA in terms consistent with the FBI's anti-Communist propaganda of the era.

In December 1951, Robeson, in New York City, and William L. Patterson, in Paris, presented the United Nations with a Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional L ...

petition titled We Charge Genocide. The document asserted that the United States federal government, by its failure to act against lynching in the United States

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' Antebellum South, pre–Civil War South in the 1830s, slowed during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and continued until L ...

, was guilty of genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

under Article II of the UN Genocide Convention. The petition was not officially acknowledged by the UN, and, though receiving some favorable reception in Europe and in America's Black press

Black Press Group Ltd. (BPG) is a Canadian commercial printer and newspaper publisher founded in 1975 by David Holmes Black. Based in Surrey, British Columbia, it was previously owned by the publisher of ''Toronto Star'' ( Torstar, 19.35%) and B ...

, was largely either ignored or criticized for its association with Communism in America's mainstream press.Peace Arch

The Peace Arch () is a monument situated near the westernmost point of the Canada–United States border in the contiguous United States, between the communities of Blaine, Washington and Surrey, British Columbia, Surrey, British Columbia. Cons ...

on the border between Washington state and the Canadian province of British Columbia. Robeson returned to perform a second concert at the Peace Arch in 1953, and over the next two years, two further concerts took place. In this period, with the encouragement of his friend the Welsh politician Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, noted for spearheading the creation of the British National Health Service during his t ...

, Robeson recorded a number of radio concerts for supporters in Wales.

1956–1957: End of McCarthyism

On June 12, 1956, Robeson was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee after he refused to sign an affidavit affirming he was not a Communist. He attempted to read his prepared statement into the Congressional Record

The ''Congressional Record'' is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress, published by the United States Government Publishing Office and issued when Congress is in session. The Congressional Record Ind ...

, but the Committee denied him that opportunity. During questioning, he invoked the Fifth Amendment and declined to reveal his political affiliations. When asked why he had not remained in the Soviet Union, given his affinity with its political ideology, he replied, "because my father was a slave and my people died to build he United States and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you and no fascist-minded people will drive me from it!"Topic Records

Topic Records is a British folk music label, which played a major role in the second British folk revival. It began as an offshoot of the Workers' Music Association in 1939, making it the oldest independent record label in the world.M. Brocken ...

, at that time part of the Workers Music Association, released a single of Robeson singing the labor anthem " Joe Hill", written by Alfred Hayes and Earl Robinson

Earl Hawley Robinson (July 2, 1910 – July 20, 1991) was an American composer, arranger and folk music singer-songwriter from Seattle, Washington. Robinson is remembered for his music, including the cantata " Ballad for Americans" and songs s ...

, backed with " John Brown's Body". In 1956, after public pressure brought a one-time exemption to the travel ban, Robeson performed two concerts in Canada in February, one in Toronto and the other at a union convention in Sudbury, Ontario.

Still unable to perform abroad in person, on May 26, 1957, Robeson sang for a London audience at St. Pancras Town Hall (where the 1,000 available concert tickets for "Let Robeson Sing" sold out within an hour) via the recently completed transatlantic telephone cable TAT-1

TAT-1 (Transatlantic No. 1) was the first submarine transatlantic telephone cable system. It was laid between Kerrera, Oban, Scotland and Clarenville, Newfoundland. Two cables were laid between 1955 and 1956 with one cable for each direction. I ...

. In October of that year, using the same technology, Robeson sang to an audience of "perhaps 5,000" at Porthcawl's Grand Pavilion in Wales.

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

's denunciation of Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

at the 1956 Party Congress silenced Robeson on Stalin, although Robeson continued to praise the Soviet Union. That year Robeson, along with close friend W.E.B. Du Bois, compared the anti-Soviet uprising in Hungary to the "same sort of people who overthrew the Spanish Republican Government" and supported the Soviet invasion and suppression of the revolt.due process

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual p ...

amounted to a violation of constitutionally protected liberty under the 5th Amendment.

Later years

''Here I Stand''

While still confined in the U.S., Robeson finished his defiant "manifesto-autobiography" '' Here I Stand'', published on February 14, 1958. John Vernon noted in ''Negro History Bulletin'' that "few publications dared or cared to review it—as if he had no longer existed". In a preface to the 1971 edition, Robeson's friend and collaborator Lloyd L. Brown wrote that "no white commercial newspaper or magazine in the entire country so much as mentioned Robeson's book. Leading papers in the field of literary coverage, like ''The New York Times'' and the ''Herald-Tribune'', not only did not review it; they refused even to include its name in their lists of 'books out today'." Brown added that the boycott was not in effect in foreign countries, for example, ''Here I Stand'' was favorably reviewed in England, Japan, and India. The book also received prompt attention from the African-American press. The ''Baltimore Afro-American

The ''Baltimore Afro-American'', commonly known as ''The Afro'' or ''Afro News'', is a weekly African-American newspaper published in Baltimore, Maryland. It is the flagship newspaper of the ''AFRO-American'' chain and the longest-running Africa ...

'' was the first to champion the merits of Robeson's autobiography. The ''Pittsburgh Courier

The ''Pittsburgh Courier'' was an African American weekly newspaper published in Pittsburgh from 1907 until October 22, 1966. By the 1930s, the ''Courier'' was one of the leading black newspapers in the United States.

It was acquired in 1965 by ...

'', '' Chicago Crusader'', and the Los Angeles ''Herald-Dispatch'' soon followed suit. The NAACP