Passenger pigeon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The passenger pigeon or wild pigeon (''Ectopistes migratorius'') is an extinct species of

Swedish naturalist

Swedish naturalist

The passenger pigeon was a member of the pigeon and dove family,

The passenger pigeon was a member of the pigeon and dove family,

pigeon

Columbidae is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with small heads, relatively short necks and slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. ...

that was endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. Its common name is derived from the French word ''passager'', meaning "passing by", due to the migratory habits of the species. The scientific name also refers to its migratory characteristics. The morphologically similar mourning dove

The mourning dove (''Zenaida macroura'') is a member of the dove Family (biology), family, Columbidae. The bird is also known as the American mourning dove, the rain dove, the chueybird, colloquially as the turtle dove, and it was once known a ...

(''Zenaida macroura'') was long thought to be its closest relative, and the two were at times confused, but genetic analysis has shown that the genus '' Patagioenas'' is more closely related to it than the ''Zenaida'' doves.

The passenger pigeon was sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

in size and coloration. The male was in length, mainly gray on the upperparts, lighter on the underparts, with iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstruc ...

bronze feathers on the neck, and black spots on the wings. The female was , and was duller and browner than the male overall. The juvenile was similar to the female, but without iridescence. It mainly inhabited the deciduous forests

In the fields of horticulture and botany, the term deciduous () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, after flo ...

of eastern North America and was also recorded elsewhere, but bred primarily around the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

. The pigeon migrated in enormous flocks, constantly searching for food, shelter, and breeding grounds, and was once the most abundant bird in North America, numbering around 3 billion, and possibly up to 5 billion. A very fast flyer, the passenger pigeon could reach a speed of . The bird fed mainly on mast, and also fruits and invertebrates. It practiced communal roosting and communal breeding, and its extreme gregariousness may have been linked with searching for food and predator satiation.

Passenger pigeons were hunted by Native Americans, but hunting intensified after the arrival of Europeans, particularly in the 19th century. Pigeon meat was commercialized as cheap food, resulting in hunting

Hunting is the Human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products (fur/hide (sk ...

on a massive scale for many decades. There were several other factors contributing to the decline and subsequent extinction of the species, including shrinking of the large breeding populations necessary for preservation of the species and widespread deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

, which destroyed its habitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

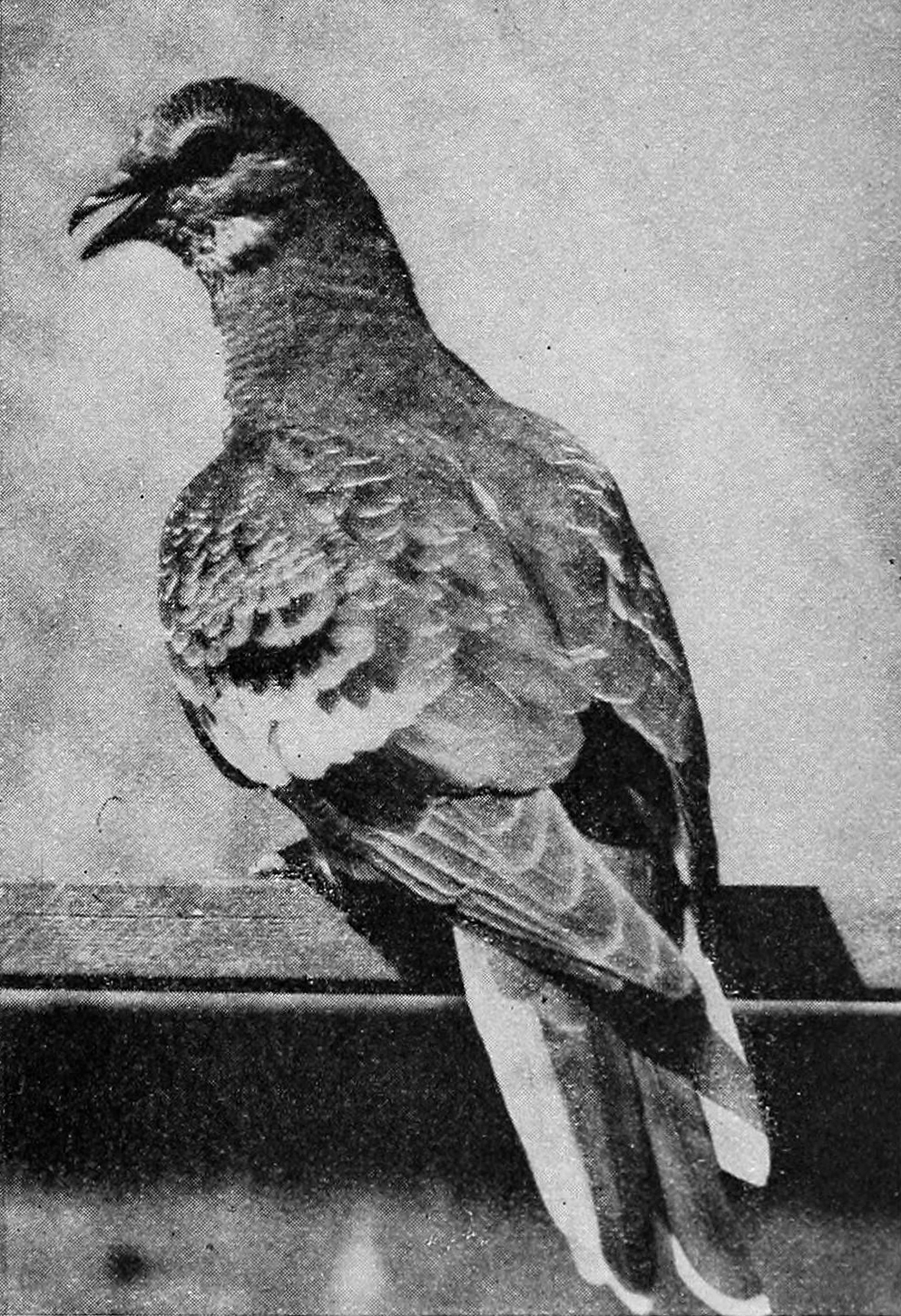

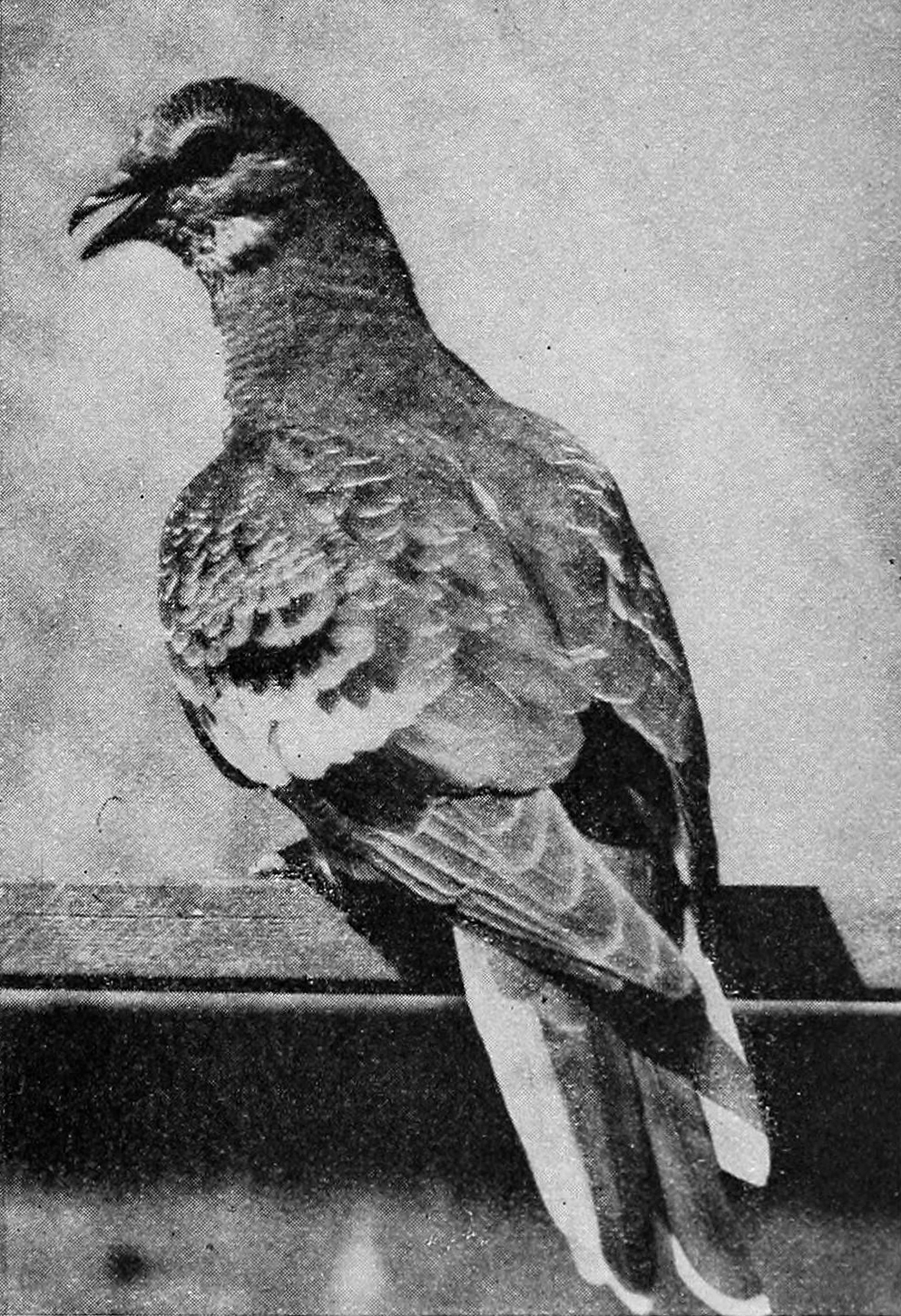

. A slow decline between about 1800 and 1870 was followed by a rapid decline between 1870 and 1890. In 1900, the last confirmed wild bird was shot in southern Ohio. The last captive birds were divided in three groups around the turn of the 20th century, some of which were photographed alive. Martha

Martha (Aramaic language, Aramaic: מָרְתָא) is a Bible, biblical figure described in the Gospels of Gospel of Luke, Luke and Gospel of John, John. Together with her siblings Lazarus of Bethany, Lazarus and Mary of Bethany, she is descr ...

, thought to be the last passenger pigeon, died on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoo. The eradication of the species is a notable example of anthropogenic extinction.

Taxonomy

Swedish naturalist

Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

coined the binomial name ''Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the important abbey ...

macroura'' for both the mourning dove

The mourning dove (''Zenaida macroura'') is a member of the dove Family (biology), family, Columbidae. The bird is also known as the American mourning dove, the rain dove, the chueybird, colloquially as the turtle dove, and it was once known a ...

and the passenger pigeon in the 1758 edition of his work ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the Orthographic ligature, ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Sweden, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the syste ...

'' (the starting point of biological nomenclature

Nomenclature codes or codes of nomenclature are the various rulebooks that govern the naming of living organisms. Standardizing the Binomial nomenclature, scientific names of biological organisms allows researchers to discuss findings (including ...

), wherein he appears to have considered the two identical. This composite description cited accounts of these birds in two pre-Linnean books. One of these was Mark Catesby

Mark Catesby (24 March 1683 – 23 December 1749) was an English natural history, naturalist who studied the flora and fauna of the New World. Between 1729 and 1747, Catesby published his ''Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama ...

's description of the passenger pigeon, which was published in his 1731 to 1743 work ''Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands'', which referred to this bird as ''Palumbus migratorius'', and was accompanied by the earliest published illustration of the species. Catesby's description was combined with the 1743 description of the mourning dove by George Edwards, who used the name ''C. macroura'' for that bird. There is nothing to suggest Linnaeus ever saw specimens of these birds himself, and his description is thought to be fully derivative of these earlier accounts and their illustrations. In his 1766 edition of ''Systema Naturae'', Linnaeus dropped the name ''C. macroura'', and instead used the name ''C. migratoria'' for the passenger pigeon, and ''C. carolinensis'' for the mourning dove. In the same edition, Linnaeus also named ''C. canadensis'', based on ''Turtur canadensis'', as used by Mathurin Jacques Brisson

Mathurin Jacques Brisson (; 30 April 1723 – 23 June 1806) was a French zoologist and natural philosophy, natural philosopher.

Brisson was born on 30 April 1723 at Fontenay-le-Comte in the Vendée department of western France. Note that page 14 ...

in 1760. Brisson's description was later shown to have been based on a female passenger pigeon.

In 1827, William Swainson

William Swainson Fellow of the Linnean Society, FLS, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (8 October 1789 – 6 December 1855), was an English ornithologist, Malacology, malacologist, Conchology, conchologist, entomologist and artist.

Life

Swains ...

moved the passenger pigeon from the genus ''Columba'' to the new monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unisp ...

genus ''Ectopistes'', due in part to the length of the wings and the wedge shape of the tail. In 1906 Outram Bangs

Outram Bangs (January 12, 1863 – September 22, 1932) was an American zoologist.

Biography

Bangs was born in Watertown, Massachusetts, as the second son of Edward and Annie Outram (Hodgkinson) Bangs. He studied at Harvard from 1880 to 1884, a ...

suggested that because Linnaeus had wholly copied Catesby's text when coining ''C. macroura'', this name should apply to the passenger pigeon, as ''E. macroura''. In 1918 Harry C. Oberholser suggested that ''C. canadensis'' should take precedence over ''C. migratoria'' (as ''E. canadensis''), as it appeared on an earlier page in Linnaeus' book. In 1952 Francis Hemming proposed that the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

(ICZN) secure the specific name ''macroura'' for the mourning dove, and the name ''migratorius'' for the passenger pigeon, since this was the intended use by the authors on whose work Linnaeus had based his description. This was accepted by the ICZN, which used its plenary powers to designate the species for the respective names in 1955.

Evolution

The passenger pigeon was a member of the pigeon and dove family,

The passenger pigeon was a member of the pigeon and dove family, Columbidae

Columbidae is a bird Family (biology), family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the Order (biology), order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with small heads, relatively short necks and slender bills that in ...

. The oldest known fossil of the genus is an isolated humerus (USNM 430960) known from the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina in sediments belonging to the Yorktown Formation, dating to the Zanclean

The Zanclean is the lowest stage or earliest age on the geologic time scale of the Pliocene. It spans the time between 5.332 ± 0.005 Ma (million years ago) and 3.6 ± 0.005 Ma. It is preceded by the Messinian Age of the Miocene Epoch, and f ...

stage of the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58''Zenaida'' doves, based on morphological grounds, particularly the physically similar mourning dove (now ''Z. macroura''). It was even suggested that the mourning dove belonged to the genus ''Ectopistes'' and was listed as ''E. carolinensis'' by some authors, including Thomas Mayo Brewer. The passenger pigeon was supposedly descended from ''Zenaida'' pigeons that had adapted to the woodlands on the plains of central North America.

The passenger pigeon differed from the species in the genus ''Zenaida'' in being larger, lacking a facial stripe, being

The passenger pigeon was physically adapted for speed, endurance, and maneuverability in flight, and has been described as having a streamlined version of the typical pigeon shape, such as that of the generalized

The passenger pigeon was physically adapted for speed, endurance, and maneuverability in flight, and has been described as having a streamlined version of the typical pigeon shape, such as that of the generalized

The noise produced by flocks of passenger pigeons was described as deafening, audible for miles away, and the bird's voice as loud, harsh, and unmusical. It was also described by some as clucks, twittering, and cooing, and as a series of low notes, instead of an actual song. The birds apparently made croaking noises when building nests, and bell-like sounds when mating. During feeding, some individuals would give

The noise produced by flocks of passenger pigeons was described as deafening, audible for miles away, and the bird's voice as loud, harsh, and unmusical. It was also described by some as clucks, twittering, and cooing, and as a series of low notes, instead of an actual song. The birds apparently made croaking noises when building nests, and bell-like sounds when mating. During feeding, some individuals would give

The passenger pigeon was found across most of North America east of the

The passenger pigeon was found across most of North America east of the

The passenger pigeon was one of the most social of all land birds. Estimated to have numbered three to five billion at the height of its population, it may have been the most numerous bird on Earth; researcher Arlie W. Schorger believed that it accounted for between 25 and 40 percent of the total land bird population in the United States. The passenger pigeon's historic population is roughly the equivalent of the number of birds that overwinter in the United States every year in the early 21st century. Even within their range, the size of individual flocks could vary greatly. In November 1859,

The passenger pigeon was one of the most social of all land birds. Estimated to have numbered three to five billion at the height of its population, it may have been the most numerous bird on Earth; researcher Arlie W. Schorger believed that it accounted for between 25 and 40 percent of the total land bird population in the United States. The passenger pigeon's historic population is roughly the equivalent of the number of birds that overwinter in the United States every year in the early 21st century. Even within their range, the size of individual flocks could vary greatly. In November 1859,  A communally roosting species, the passenger pigeon chose roosting sites that could provide shelter and enough food to sustain their large numbers for an indefinite period. The time spent at one roosting site may have depended on the extent of human persecution, weather conditions, or other, unknown factors. Roosts ranged in size and extent, from a few acres to or greater. Some roosting areas would be reused for subsequent years, others would only be used once. The passenger pigeon roosted in such numbers that even thick tree branches would break under the strain. The birds frequently piled on top of each other's backs to roost. They rested in a slumped position that hid their feet. They slept with their bills concealed by the feathers in the middle of the breast while holding their tail at a 45-degree angle. Dung could accumulate under a roosting site to a depth of over .

If the pigeon became alert, it would often stretch out its head and neck in line with its body and tail, then nod its head in a circular pattern. When aggravated by another pigeon, it raised its wings threateningly, but passenger pigeons almost never actually fought. The pigeon bathed in shallow water, and afterwards lay on each side in turn and raised the opposite wing to dry it.

The passenger pigeon drank at least once a day, typically at dawn, by fully inserting its bill into lakes, small ponds, and streams. Pigeons were seen perching on top of each other to access water, and if necessary, the species could alight on open water to drink. One of the primary causes of natural mortality was the weather, and every spring many individuals froze to death after migrating north too early. In captivity, a passenger pigeon was capable of living at least 15 years;

A communally roosting species, the passenger pigeon chose roosting sites that could provide shelter and enough food to sustain their large numbers for an indefinite period. The time spent at one roosting site may have depended on the extent of human persecution, weather conditions, or other, unknown factors. Roosts ranged in size and extent, from a few acres to or greater. Some roosting areas would be reused for subsequent years, others would only be used once. The passenger pigeon roosted in such numbers that even thick tree branches would break under the strain. The birds frequently piled on top of each other's backs to roost. They rested in a slumped position that hid their feet. They slept with their bills concealed by the feathers in the middle of the breast while holding their tail at a 45-degree angle. Dung could accumulate under a roosting site to a depth of over .

If the pigeon became alert, it would often stretch out its head and neck in line with its body and tail, then nod its head in a circular pattern. When aggravated by another pigeon, it raised its wings threateningly, but passenger pigeons almost never actually fought. The pigeon bathed in shallow water, and afterwards lay on each side in turn and raised the opposite wing to dry it.

The passenger pigeon drank at least once a day, typically at dawn, by fully inserting its bill into lakes, small ponds, and streams. Pigeons were seen perching on top of each other to access water, and if necessary, the species could alight on open water to drink. One of the primary causes of natural mortality was the weather, and every spring many individuals froze to death after migrating north too early. In captivity, a passenger pigeon was capable of living at least 15 years;

The passenger pigeon foraged in flocks of tens or hundreds of thousands of individuals that overturned leaves, dirt, and snow with their bills in search of food. One observer described the motion of such a flock in search of mast as having a rolling appearance, as birds in the back of the flock flew overhead to the front of the flock, dropping leaves and grass in flight. The flocks had wide leading edges to better scan the landscape for food sources.

When nuts on a tree loosened from their caps, a pigeon would land on a branch and, while flapping vigorously to stay balanced, grab the nut, pull it loose from its cap, and swallow it whole. Collectively, a foraging flock was capable of removing nearly all fruits and nuts from their path. Birds in the back of the flock flew to the front in order to pick over unsearched ground; however, birds never ventured far from the flock and hurried back if they became isolated. It is believed that the pigeons used social cues to identify abundant sources of food, and a flock of pigeons that saw others feeding on the ground often joined them. During the day, the birds left the roosting forest to forage on more open land. They regularly flew away from their roost daily in search of food, and some pigeons reportedly traveled as far as , leaving the roosting area early and returning at night.

The passenger pigeon's very elastic mouth and throat and a joint in the lower bill enabled it to swallow acorns whole. It could store large quantities of food in its

The passenger pigeon foraged in flocks of tens or hundreds of thousands of individuals that overturned leaves, dirt, and snow with their bills in search of food. One observer described the motion of such a flock in search of mast as having a rolling appearance, as birds in the back of the flock flew overhead to the front of the flock, dropping leaves and grass in flight. The flocks had wide leading edges to better scan the landscape for food sources.

When nuts on a tree loosened from their caps, a pigeon would land on a branch and, while flapping vigorously to stay balanced, grab the nut, pull it loose from its cap, and swallow it whole. Collectively, a foraging flock was capable of removing nearly all fruits and nuts from their path. Birds in the back of the flock flew to the front in order to pick over unsearched ground; however, birds never ventured far from the flock and hurried back if they became isolated. It is believed that the pigeons used social cues to identify abundant sources of food, and a flock of pigeons that saw others feeding on the ground often joined them. During the day, the birds left the roosting forest to forage on more open land. They regularly flew away from their roost daily in search of food, and some pigeons reportedly traveled as far as , leaving the roosting area early and returning at night.

The passenger pigeon's very elastic mouth and throat and a joint in the lower bill enabled it to swallow acorns whole. It could store large quantities of food in its

Other than finding roosting sites, the migrations of the passenger pigeon were connected with finding places appropriate for this

Other than finding roosting sites, the migrations of the passenger pigeon were connected with finding places appropriate for this  After observing captive birds, Wallace Craig found that this species did less charging and strutting than other pigeons (as it was awkward on the ground), and thought it probable that no food was transferred during their brief billing (unlike in other pigeons), and he therefore considered Audubon's description partially based on analogy with other pigeons as well as imagination.

After observing captive birds, Wallace Craig found that this species did less charging and strutting than other pigeons (as it was awkward on the ground), and thought it probable that no food was transferred during their brief billing (unlike in other pigeons), and he therefore considered Audubon's description partially based on analogy with other pigeons as well as imagination.

Nests were built immediately after pair formation and took two to four days to construct; this process was highly synchronized within a colony. The female chose the nesting site by sitting on it and flicking her wings. The male then carefully selected nesting materials, typically twigs, and handed them to the female over her back. The male then went in search of more nesting material while the female constructed the nest beneath herself. Nests were built between above the ground, though typically above , and were made of 70 to 110 twigs woven together to create a loose, shallow bowl through which the egg could easily be seen. This bowl was then typically lined with finer twigs. The nests were about wide, high, and deep. Though the nest has been described as crude and flimsy compared to those of many other birds, remains of nests could be found at sites where nesting had taken place several years prior. Nearly every tree capable of supporting nests had them, often more than 50 per tree; one hemlock was recorded as holding 317 nests. The nests were placed on strong branches close to the tree trunks. Some accounts state that ground under the nesting area looked as if it had been swept clean, due to all the twigs being collected at the same time, yet this area would also have been covered in dung. As both sexes took care of the nest, the pairs were

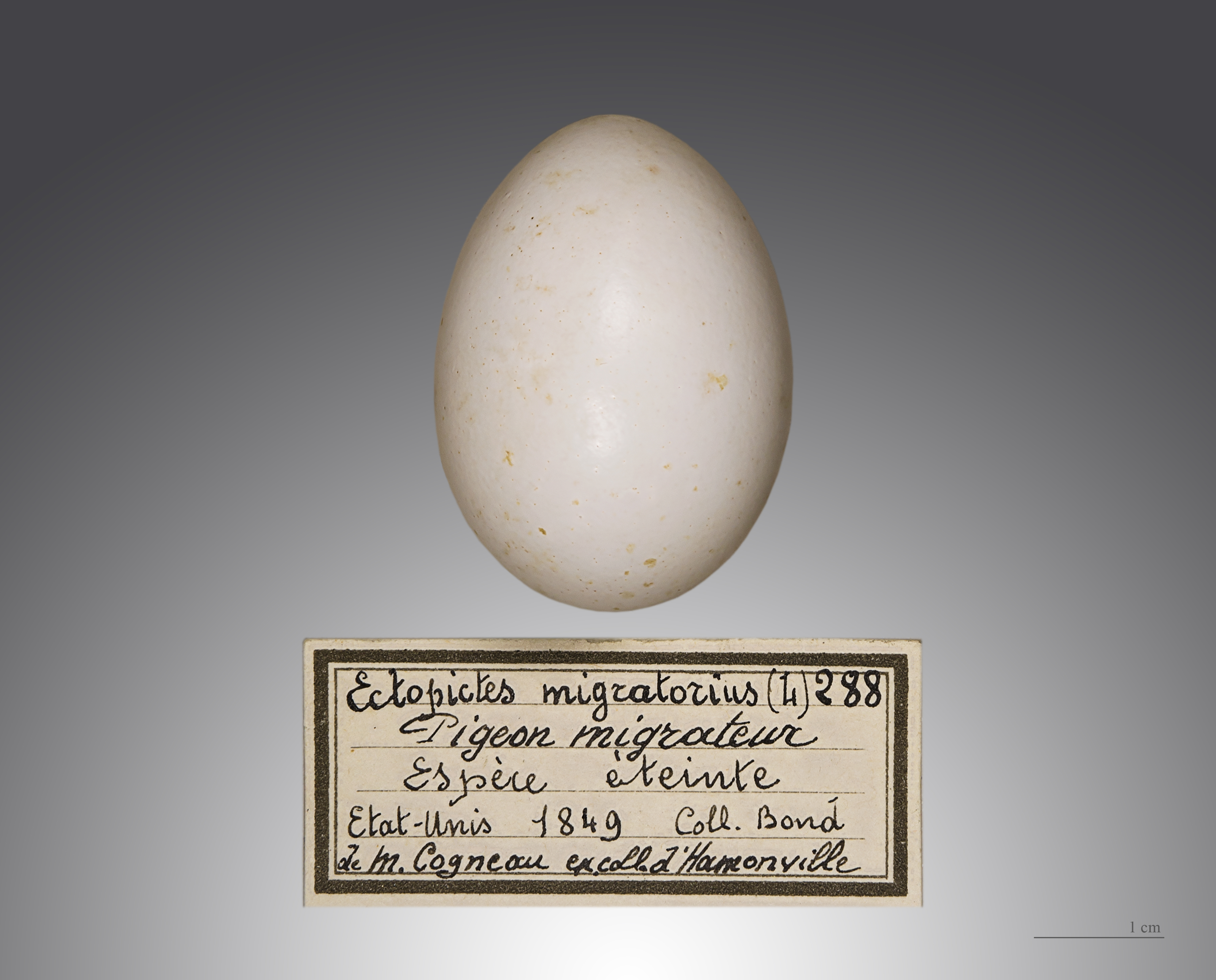

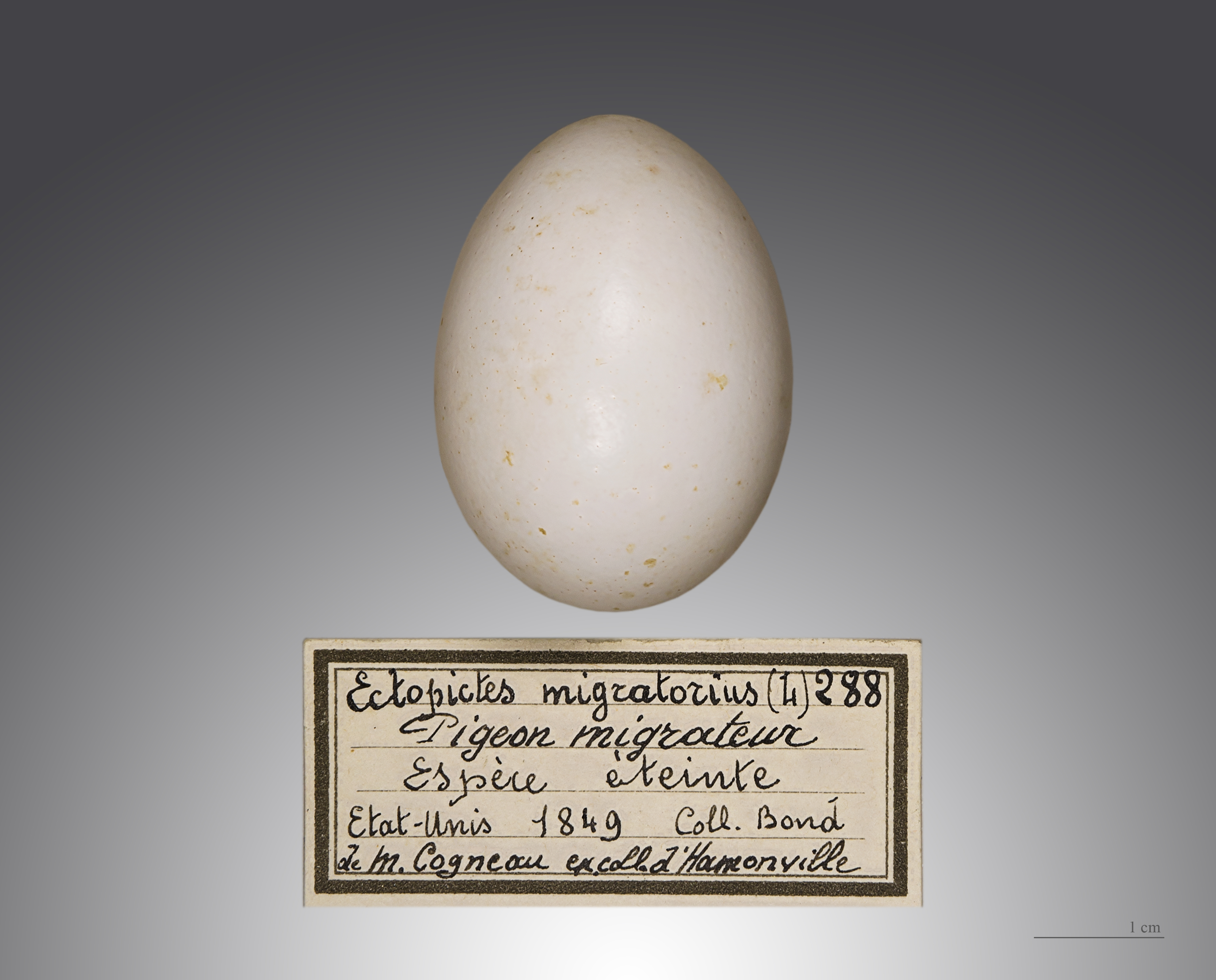

Nests were built immediately after pair formation and took two to four days to construct; this process was highly synchronized within a colony. The female chose the nesting site by sitting on it and flicking her wings. The male then carefully selected nesting materials, typically twigs, and handed them to the female over her back. The male then went in search of more nesting material while the female constructed the nest beneath herself. Nests were built between above the ground, though typically above , and were made of 70 to 110 twigs woven together to create a loose, shallow bowl through which the egg could easily be seen. This bowl was then typically lined with finer twigs. The nests were about wide, high, and deep. Though the nest has been described as crude and flimsy compared to those of many other birds, remains of nests could be found at sites where nesting had taken place several years prior. Nearly every tree capable of supporting nests had them, often more than 50 per tree; one hemlock was recorded as holding 317 nests. The nests were placed on strong branches close to the tree trunks. Some accounts state that ground under the nesting area looked as if it had been swept clean, due to all the twigs being collected at the same time, yet this area would also have been covered in dung. As both sexes took care of the nest, the pairs were  Generally, the eggs were laid during the first two weeks of April across the pigeon's range. Each female laid its egg immediately or almost immediately after the nest was completed; sometimes the pigeon was forced to lay it on the ground if the nest was not complete. The normal clutch size appears to have been a single egg, but there is some uncertainty about this, as two have also been reported from the same nests. Occasionally, a second female laid its egg in another female's nest, resulting in two eggs being present. The egg was white and oval shaped and averaged in size. If the egg was lost, it was possible for the pigeon to lay a replacement egg within a week. A whole colony was known to re-nest after a snowstorm forced them to abandon their original colony. Both parents incubated The egg for 12 to 14 days, with the male incubating it from midmorning to midafternoon and the female incubating it the rest of the time.

Upon hatching, the nestling (or squab) was blind and sparsely covered with yellow, hairlike down. The nestling developed quickly and within 14 days weighed as much as its parents. During this brooding period both parents took care of the nestling, with the male attending in the middle of the day and the female at other times. The nestlings were fed crop milk (a substance similar to

Generally, the eggs were laid during the first two weeks of April across the pigeon's range. Each female laid its egg immediately or almost immediately after the nest was completed; sometimes the pigeon was forced to lay it on the ground if the nest was not complete. The normal clutch size appears to have been a single egg, but there is some uncertainty about this, as two have also been reported from the same nests. Occasionally, a second female laid its egg in another female's nest, resulting in two eggs being present. The egg was white and oval shaped and averaged in size. If the egg was lost, it was possible for the pigeon to lay a replacement egg within a week. A whole colony was known to re-nest after a snowstorm forced them to abandon their original colony. Both parents incubated The egg for 12 to 14 days, with the male incubating it from midmorning to midafternoon and the female incubating it the rest of the time.

Upon hatching, the nestling (or squab) was blind and sparsely covered with yellow, hairlike down. The nestling developed quickly and within 14 days weighed as much as its parents. During this brooding period both parents took care of the nestling, with the male attending in the middle of the day and the female at other times. The nestlings were fed crop milk (a substance similar to

Nesting colonies attracted large numbers of predators, including

Nesting colonies attracted large numbers of predators, including

The passenger pigeon was featured in the writings of many significant early naturalists, as well as accompanying illustrations. Mark Catesby's 1731 illustration, the first published depiction of this bird, is somewhat crude, according to some later commentators. The original watercolor that the engraving is based on was bought by the British royal family in 1768, along with the rest of Catesby's watercolors. The naturalists Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon both witnessed large pigeon migrations first hand, and published detailed accounts wherein both attempted to deduce the total number of birds involved. The most famous and often reproduced depiction of the passenger pigeon is Audubon's illustration (handcolored

The passenger pigeon was featured in the writings of many significant early naturalists, as well as accompanying illustrations. Mark Catesby's 1731 illustration, the first published depiction of this bird, is somewhat crude, according to some later commentators. The original watercolor that the engraving is based on was bought by the British royal family in 1768, along with the rest of Catesby's watercolors. The naturalists Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon both witnessed large pigeon migrations first hand, and published detailed accounts wherein both attempted to deduce the total number of birds involved. The most famous and often reproduced depiction of the passenger pigeon is Audubon's illustration (handcolored

The passenger pigeon was an important source of food for the people of North America. Native Americans ate pigeons, and tribes near nesting colonies would sometimes move to live closer to them and eat the juveniles, killing them at night with long poles. Many Native Americans were careful not to disturb the adult pigeons, and instead ate only the juveniles as they were afraid that the adults might desert their nesting grounds; in some tribes, disturbing the adult pigeons was considered a crime. Away from the nests, large nets were used to capture adult pigeons, sometimes up to 800 at a time. Low-flying pigeons could be killed by throwing sticks or stones. At one site in

The passenger pigeon was an important source of food for the people of North America. Native Americans ate pigeons, and tribes near nesting colonies would sometimes move to live closer to them and eat the juveniles, killing them at night with long poles. Many Native Americans were careful not to disturb the adult pigeons, and instead ate only the juveniles as they were afraid that the adults might desert their nesting grounds; in some tribes, disturbing the adult pigeons was considered a crime. Away from the nests, large nets were used to capture adult pigeons, sometimes up to 800 at a time. Low-flying pigeons could be killed by throwing sticks or stones. At one site in  What may be the earliest account of Europeans hunting passenger pigeons dates to January 1565, when the French explorer René Laudonnière wrote of killing close to 10,000 of them around

What may be the earliest account of Europeans hunting passenger pigeons dates to January 1565, when the French explorer René Laudonnière wrote of killing close to 10,000 of them around  Humans used a wide variety of other methods to capture and kill passenger pigeons. Nets were propped up to allow passenger pigeons entry, and then closed by knocking loose the stick that supported the opening, trapping twenty or more pigeons inside. Tunnel nets were also used to great effect, and one particularly large net was capable of catching 3,500 pigeons at a time. These nets were used by many farmers on their own property as well as by professional trappers. Food would be placed on the ground near the nets to attract the pigeons.

Humans used a wide variety of other methods to capture and kill passenger pigeons. Nets were propped up to allow passenger pigeons entry, and then closed by knocking loose the stick that supported the opening, trapping twenty or more pigeons inside. Tunnel nets were also used to great effect, and one particularly large net was capable of catching 3,500 pigeons at a time. These nets were used by many farmers on their own property as well as by professional trappers. Food would be placed on the ground near the nets to attract the pigeons.  By the mid-19th century,

By the mid-19th century,

Most captive passenger pigeons were kept for exploitative purposes, but some were housed in zoos and aviaries. Audubon alone claimed to have brought 350 birds to England in 1830, distributing them among various noblemen, and the species is also known to have been kept at

Most captive passenger pigeons were kept for exploitative purposes, but some were housed in zoos and aviaries. Audubon alone claimed to have brought 350 birds to England in 1830, distributing them among various noblemen, and the species is also known to have been kept at  The Cincinnati Zoo, one of the oldest zoos in the United States, kept passenger pigeons from its beginning in 1875. The zoo kept more than twenty individuals in a cage. Passenger pigeons do not appear to have been kept at the zoo due to their rarity, but to enable guests to have a closer look at a native species. Recognizing the decline of the wild populations, Whitman and the Cincinnati Zoo consistently strove to breed the surviving birds, including attempts at making a rock dove foster passenger pigeon eggs. In 1902, Whitman gave a female passenger pigeon to the zoo; this was possibly the individual later known as Martha, which would become the last living member of the species. Other sources argue that Martha was hatched at the Cincinnati Zoo, lived there for 25 years, and was the descendant of three pairs of passenger pigeons purchased by the zoo in 1877. It is thought this individual was named Martha because her last cage mate was named George, thereby honoring

The Cincinnati Zoo, one of the oldest zoos in the United States, kept passenger pigeons from its beginning in 1875. The zoo kept more than twenty individuals in a cage. Passenger pigeons do not appear to have been kept at the zoo due to their rarity, but to enable guests to have a closer look at a native species. Recognizing the decline of the wild populations, Whitman and the Cincinnati Zoo consistently strove to breed the surviving birds, including attempts at making a rock dove foster passenger pigeon eggs. In 1902, Whitman gave a female passenger pigeon to the zoo; this was possibly the individual later known as Martha, which would become the last living member of the species. Other sources argue that Martha was hatched at the Cincinnati Zoo, lived there for 25 years, and was the descendant of three pairs of passenger pigeons purchased by the zoo in 1877. It is thought this individual was named Martha because her last cage mate was named George, thereby honoring

The 2014 genetic study that found natural fluctuations in population numbers prior to human arrival also concluded that the species routinely recovered from lows in the population, and suggested that one of these lows may have coincided with the intensified hunting by humans in the 1800s, a combination which would have led to the rapid extinction of the species. A similar scenario may also explain the rapid extinction of the Rocky Mountain locust (''Melanoplus spretus'') during the same period. It has also been suggested that after the population was thinned out, it would be harder for few or solitary birds to locate suitable feeding areas. In addition to the birds killed or driven away by hunting during breeding seasons, many nestlings were also orphaned before being able to fend for themselves. Other, less convincing contributing factors have been suggested at times, including mass drownings,

The 2014 genetic study that found natural fluctuations in population numbers prior to human arrival also concluded that the species routinely recovered from lows in the population, and suggested that one of these lows may have coincided with the intensified hunting by humans in the 1800s, a combination which would have led to the rapid extinction of the species. A similar scenario may also explain the rapid extinction of the Rocky Mountain locust (''Melanoplus spretus'') during the same period. It has also been suggested that after the population was thinned out, it would be harder for few or solitary birds to locate suitable feeding areas. In addition to the birds killed or driven away by hunting during breeding seasons, many nestlings were also orphaned before being able to fend for themselves. Other, less convincing contributing factors have been suggested at times, including mass drownings,

Today, at least 1,532 passenger pigeon skins (along with 16 skeletons) still exist, spread across many institutions all over the world. It has been suggested that the passenger pigeon should be revived when available technology allows it (a concept which has been termed "

Today, at least 1,532 passenger pigeon skins (along with 16 skeletons) still exist, spread across many institutions all over the world. It has been suggested that the passenger pigeon should be revived when available technology allows it (a concept which has been termed "

Project Passenger Pigeon: Lessons from the Past for a Sustainable Future

The Demise of the Passenger Pigeon

(as broadcast on

360-degree view of Martha, the last passenger pigeon

(

sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, and having iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstruc ...

neck feathers and a smaller clutch

A clutch is a mechanical device that allows an output shaft to be disconnected from a rotating input shaft. The clutch's input shaft is typically attached to a motor, while the clutch's output shaft is connected to the mechanism that does th ...

. In a 2002 study by American geneticist Beth Shapiro et al., museum specimens of the passenger pigeon were included in an ancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient sources (typically Biological specimen, specimens, but also environmental DNA). Due to degradation processes (including Crosslinking of DNA, cross-linking, deamination and DNA fragmentation, fragme ...

analysis for the first time (in a paper focusing mainly on the dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinction, extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest relative was the also-extinct and flightles ...

), and it was found to be the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

of the cuckoo-dove genus '' Macropygia''. The ''Zenaida'' doves were instead shown to be related to the quail-doves of the genus '' Geotrygon'' and the '' Leptotila'' doves.

A more extensive 2010 study instead showed that the passenger pigeon was most closely related to the New World '' Patagioenas'' pigeons, including the band-tailed pigeon (''P. fasciata'') of western North America, which are related to the Southeast Asian species in the genera '' Turacoena'', ''Macropygia'', and '' Reinwardtoena''. This clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

is also related to the ''Columba'' and ''Streptopelia

''Streptopelia'' (collared doves and turtle doves) is a genus of 15 species of birds in the pigeon and dove family Columbidae native to the Old World in Africa, Europe, and Asia. These are mainly slim, small to medium-sized species. The upperpar ...

'' doves of the Old World (collectively termed the "typical pigeons and doves"). The authors of the study suggested that the ancestors of the passenger pigeon may have colonized the New World from South East Asia by flying across the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

, or perhaps across Beringia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 70th parallel north, 72° north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south ...

in the north.

In a 2012 study, the nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. ...

of the passenger pigeon was analyzed for the first time, and its relationship with the ''Patagioenas'' pigeon was confirmed. In contrast to the 2010 study, these authors suggested that their results could indicate that the ancestors of the passenger pigeon and its Old World relatives may have originated in the Neotropical region of the New World.

The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

below follows the 2012 DNA study showing the position of the passenger pigeon among its closest relatives:

DNA in old museum specimens is often degraded and fragmentary, and passenger pigeon specimens have been used in various studies to discover improved methods of analyzing and assembling genomes from such material. DNA samples are often taken from the toe pads of bird skins in museums, as this can be done without causing significant damage to valuable specimens. The passenger pigeon had no known subspecies. Hybridization occurred between the passenger pigeon and the Barbary dove (''Streptopelia risoria'') in the aviary of Charles Otis Whitman (who owned many of the last captive birds around the turn of the 20th century, and kept them with other pigeon species) but the offspring were infertile.

Etymology

The genus name, ''Ectopistes'', translates as "moving about" or "wandering", while the specific name, ''migratorius'', indicates its migratory habits. The full binomial can thus be translated as "migratory wanderer". The English common name "passenger pigeon" derives from the French word ', which means "to pass by" in a fleeting manner. While the pigeon was extant, the name "passenger pigeon" was used interchangeably with "wild pigeon". p. 251. The bird also gained some less-frequently used names, including blue pigeon, merne rouck pigeon, wandering long-tailed dove, and wood pigeon. In the 18th century, the passenger pigeon was known as ''tourte'' inNew France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

(in modern Canada), but to the French in Europe it was known as ''tourtre''. In modern French, the bird is known as ''tourte voyageuse'' or ''pigeon migrateur'', among other names.

In the Native American Algonquian languages

The Algonquian languages ( ; also Algonkian) are a family of Indigenous languages of the Americas and most of the languages in the Algic language family are included in the group. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from ...

, the pigeon was called ''amimi'' by the Lenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historica ...

, ' by the Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

, and ' by the Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were a historical Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

. Other names in indigenous American languages include ' in Mohawk, and ', or "lost dove", in Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

. The Seneca people

The Seneca ( ; ) are a group of Indigenous Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes in North America. Their nation was the farthest to the west within the Six Nations or Iroquois Leag ...

called the pigeon ', meaning "big bread", as it was a source of food for their tribes. Chief Simon Pokagon of the Potawatomi

The Potawatomi (), also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains, upper Mississippi River, and western Great Lakes region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, ...

stated that his people called the pigeon ', and that the Europeans did not adopt native names for the bird, as it reminded them of their domesticated pigeons, instead calling them "wild" pigeons, as they called the native peoples "wild" men.

Description

The passenger pigeon wassexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

in size and coloration. It weighed between . The adult male was about in length. It had a bluish-gray head, nape, and hindneck. On the sides of the neck and the upper mantle were iridescent display feathers that have variously been described as being a bright bronze, violet, or golden-green, depending on the angle of the light. The upper back and wings were a pale or slate gray tinged with olive brown, that turned into grayish-brown on the lower wings. The lower back and rump were a dark blue-gray that became grayish-brown on the upper tail- covert feathers. The greater and median wing-covert feathers were pale gray, with a small number of irregular black spots near the end. The primary and secondary feathers of the wing were a blackish-brown with a narrow white edge on the outer side of the secondaries. The two central tail feathers were brownish gray, and the rest were white.

The tail pattern was distinctive as it had white outer edges with blackish spots that were prominently displayed in flight. The lower throat and breast were richly pinkish-rufous

Rufous () is a color that may be described as reddish-brown or brownish- red, as of rust or oxidised iron. The first recorded use of ''rufous'' as a color name in English was in 1782. However, the color is also recorded earlier in 1527 as a d ...

, grading into a paler pink further down, and into white on the abdomen and undertail covert feathers. The undertail coverts also had a few black spots. The bill was black, while the feet and legs were a bright coral red. It had a carmine

Carmine ()also called cochineal (when it is extracted from the Cochineal, cochineal insect), cochineal extract, crimson Lake pigment, lake, or carmine lake is a pigment of a bright-red color obtained from the aluminium coordination complex, compl ...

-red iris surrounded by a narrow purplish-red eye-ring. The wing of the male measured , the tail , the bill , and the tarsus was .

The adult female passenger pigeon was slightly smaller than the male at in length. It was duller than the male overall, and was a grayish-brown on the forehead, crown, and nape down to the scapular

A scapular () is a Western Christian garment suspended from the shoulders. There are two types of scapulars, the monastic and devotional scapular; both forms may simply be referred to as "scapular". As an object of popular piety, a scapular ...

s, and the feathers on the sides of the neck had less iridescence

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstru ...

than those of the male. The lower throat and breast were a buff-gray that developed into white on the belly and undertail-coverts. It was browner on the upperparts and paler buff brown and less rufous on the underparts than the male. The wings, back, and tail were similar in appearance to those of the male except that the outer edges of the primary feathers were edged in buff or rufous buff. The wings had more spotting than those of the male. The tail was shorter than that of the male, and the legs and feet were a paler red. The iris was orange red, with a grayish blue, naked orbital ring. The wing of the female was , the tail , the bill , and the tarsus was .

The juvenile passenger pigeon was similar in plumage

Plumage () is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, there can b ...

to the adult female, but lacked the spotting on the wings, and was a darker brownish-gray on the head, neck, and breast. The feathers on the wings had pale gray fringes (also described as white tips), giving it a scaled look. The secondaries were brownish-black with pale edges, and the tertial feathers had a rufous wash. The primaries were also edged with a rufous-brown color. The neck feathers had no iridescence. The legs and feet were dull red, and the iris was brownish, and surrounded by a narrow carmine ring. The plumage of the sexes was similar during their first year.

Of the hundreds of surviving skins, only one appears to be aberrant in coloran adult female from the collection of Walter Rothschild, Natural History Museum at Tring

The Natural History Museum at Tring was the private museum of Lionel Walter, 2nd Baron Rothschild; today it is under the control of the Natural History Museum, London. It houses one of the finest collections of stuffed mammals, birds, reptil ...

. It is a washed brown on the upper parts, wing covert, secondary feathers, and tail (where it would otherwise have been gray), and white on the primary feathers and underparts. The normally black spots are brown, and it is pale gray on the head, lower back, and upper-tail covert feathers, yet the iridescence is unaffected. The brown mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

is a result of a reduction in eumelanin

Melanin (; ) is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are ...

, due to incomplete synthesis (oxidation

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

) of this pigment

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

. This sex-linked mutation is common in female wild birds, but it is thought the white feathers of this specimen are instead the result of bleaching due to exposure to sunlight.

The passenger pigeon was physically adapted for speed, endurance, and maneuverability in flight, and has been described as having a streamlined version of the typical pigeon shape, such as that of the generalized

The passenger pigeon was physically adapted for speed, endurance, and maneuverability in flight, and has been described as having a streamlined version of the typical pigeon shape, such as that of the generalized rock dove

The rock dove (''Columba livia''), also sometimes known as "rock pigeon" or "common pigeon", is a member of the bird family Columbidae (doves and pigeons). In common usage, it is often simply referred to as the "pigeon", although the rock dov ...

(''Columba livia''). The wings were very long and pointed, and measured from the wing-chord to the primary feathers, and to the secondaries. The tail, which accounted for much of its overall length, was long and wedge-shaped (or graduated), with two central feathers longer than the rest. The body was slender and narrow, and the head and neck were small.

The internal anatomy of the passenger pigeon has rarely been described. Robert W. Shufeldt found little to differentiate the bird's osteology from that of other pigeons when examining a male skeleton in 1914, but Julian P. Hume noted several distinct features in a more detailed 2015 description. The pigeon's particularly large breast muscles indicated a powerful flight ( musculus pectoralis major for downstroke and the smaller musculus supracoracoideus for upstroke). The coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

bone (which connects the scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

, furcula, and sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

) was large relative to the size of the bird, , with straighter shafts and more robust articular ends than in other pigeons. The furcula had a sharper V-shape and was more robust, with expanded articular ends. The scapula was long, straight, and robust, and its distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position provi ...

end was enlarged. The sternum was very large and robust compared to that of other pigeons; its keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

was deep. The overlapping uncinate processes, which stiffen the ribcage, were very well developed. The wing bones (humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

, radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

, ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

, and carpometacarpus

The carpometacarpus is a bone found in the hands of birds. It results from the fusion of the carpal and metacarpal bone, and is essentially a single fused bone between the wrist and the knuckles. It is a smallish bone in most birds, generally fla ...

) were short but robust compared to other pigeons. The leg bones were similar to those of other pigeons.

Vocalizations

The noise produced by flocks of passenger pigeons was described as deafening, audible for miles away, and the bird's voice as loud, harsh, and unmusical. It was also described by some as clucks, twittering, and cooing, and as a series of low notes, instead of an actual song. The birds apparently made croaking noises when building nests, and bell-like sounds when mating. During feeding, some individuals would give

The noise produced by flocks of passenger pigeons was described as deafening, audible for miles away, and the bird's voice as loud, harsh, and unmusical. It was also described by some as clucks, twittering, and cooing, and as a series of low notes, instead of an actual song. The birds apparently made croaking noises when building nests, and bell-like sounds when mating. During feeding, some individuals would give alarm calls

In animal communication, an alarm signal is an antipredator adaptation in the form of signals emitted by social animals in response to danger. Many primates and birds have elaborate alarm calls for warning conspecifics of approaching predators ...

when facing a threat, and the rest of the flock would join the sound while taking off. pp. 30–47.

In 1911, American behavioral scientist Wallace Craig

Wallace Craig (1876–1954) was an American experimental psychologist and behavior scientist. He provided a conceptual framework for the study of behavior organization and is regarded as one of the founders of ethology. Craig experimentally stu ...

published an account of the gestures and sounds of this species as a series of descriptions and musical notation

Musical notation is any system used to visually represent music. Systems of notation generally represent the elements of a piece of music that are considered important for its performance in the context of a given musical tradition. The proce ...

s, based on observation of C. O. Whitman's captive passenger pigeons in 1903. Craig compiled these records to assist in identifying potential survivors in the wild (as the physically similar mourning doves could otherwise be mistaken for passenger pigeons), while noting this "meager information" was likely all that would be left on the subject. According to Craig, one call was a simple harsh "keck" that could be given twice in succession with a pause in between. This was said to be used to attract the attention of another pigeon. Another call was a more frequent and variable scolding. This sound was described as "kee-kee-kee-kee" or "tete! tete! tete!", and was used to call either to its mate or towards other creatures it considered to be enemies. One variant of this call, described as a long, drawn-out "tweet", could be used to call down a flock of passenger pigeons passing overhead, which would then land in a nearby tree. "Keeho" was a soft cooing that, while followed by louder "keck" notes or scolding, was directed at the bird's mate. A nesting passenger pigeon would also give off a stream of at least eight mixed notes that were both high and low in tone and ended with "keeho". Overall, female passenger pigeons were quieter and called infrequently. Craig suggested that the loud, strident voice and "degenerated" musicality was the result of living in populous colonies where only the loudest sounds could be heard.

Distribution and habitat

The passenger pigeon was found across most of North America east of the

The passenger pigeon was found across most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

, from the Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

to the Atlantic coast in the east, to the south of Canada in the north, and the north of Mississippi in the southern United States, coinciding with its primary habitat, the eastern deciduous forests

In the fields of horticulture and botany, the term deciduous () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, after flo ...

. Within this range, it constantly migrated in search of food and shelter. It is unclear if the birds favored particular trees and terrain, but they were possibly not restricted to one type, as long as their numbers could be supported. It originally bred from the southern parts of eastern and central Canada south to eastern Kansas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Georgia in the United States, but the primary breeding range was in southern Ontario and the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

states south through states north of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

. Though the western forests were ecologically similar to those in the east, these were occupied by band-tailed pigeons, which may have kept out the passenger pigeons through competitive exclusion.

The passenger pigeon wintered from Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina south to Texas, the Gulf Coast, and northern Florida, though flocks occasionally wintered as far north as southern Pennsylvania and Connecticut. It preferred to winter in large swamps, particularly those with alder

Alders are trees of the genus ''Alnus'' in the birch family Betulaceae. The genus includes about 35 species of monoecious trees and shrubs, a few reaching a large size, distributed throughout the north temperate zone with a few species ex ...

trees; if swamps were not available, forested areas, particularly with pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

trees, were favored roosting sites. There were also sightings of passenger pigeons outside of its normal range, including in several Western states, Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, particularly during severe winters. It has been suggested that some of these extralimital records may have been due to the paucity of observers rather than the actual extent of passenger pigeons; North America was then unsettled country, and the bird may have appeared anywhere on the continent except for the far west. There were also records of stragglers in Scotland, Ireland, and France, although these birds may have been escaped captives, or the records incorrect.

More than 130 passenger pigeon fossils have been found scattered across 25 US states, including in the La Brea Tar Pits

La Brea Tar Pits comprise an active Paleontological site, paleontological research site in urban Los Angeles. Hancock Park was formed around a group of tar pits where natural Bitumen, asphalt (also called asphaltum, bitumen, or pitch; ''brea'' ...

of California. These records date as far back as 100,000 years ago in the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

era, during which the pigeon's range extended to several western states that were not a part of its modern range. The abundance of the species in these regions and during this time is unknown.

Ecology and behavior

The passenger pigeon wasnomad

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the population of nomadic pa ...

ic, constantly migrating in search of food, shelter, or nesting grounds. In his 1831 ''Ornithological Biography'', American naturalist and artist John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin, April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was a French-American Autodidacticism, self-trained artist, natural history, naturalist, and ornithology, ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornitho ...

described a migration he observed in 1813 as follows:

These flocks were frequently described as being so dense that they blackened the sky and as having no sign of subdivisions. The flocks ranged from only above the ground in windy conditions to as high as . These migrating flocks were typically in narrow columns that twisted and undulated, and they were reported as being in nearly every conceivable shape. A skilled flyer, the passenger pigeon is estimated to have averaged during migration. It flew with quick, repeated flaps that increased the bird's velocity the closer the wings got to the body. It was equally adept and quick flying through a forest as through open space. A flock was also adept at following the lead of the pigeon in front of it, and flocks swerved together to avoid a predator. When landing, the pigeon flapped its wings repeatedly before raising them at the moment of landing. The pigeon was awkward when on the ground, and moved around with jerky, alert steps.

The passenger pigeon was one of the most social of all land birds. Estimated to have numbered three to five billion at the height of its population, it may have been the most numerous bird on Earth; researcher Arlie W. Schorger believed that it accounted for between 25 and 40 percent of the total land bird population in the United States. The passenger pigeon's historic population is roughly the equivalent of the number of birds that overwinter in the United States every year in the early 21st century. Even within their range, the size of individual flocks could vary greatly. In November 1859,

The passenger pigeon was one of the most social of all land birds. Estimated to have numbered three to five billion at the height of its population, it may have been the most numerous bird on Earth; researcher Arlie W. Schorger believed that it accounted for between 25 and 40 percent of the total land bird population in the United States. The passenger pigeon's historic population is roughly the equivalent of the number of birds that overwinter in the United States every year in the early 21st century. Even within their range, the size of individual flocks could vary greatly. In November 1859, Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

, writing in Concord, Massachusetts

Concord () is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. In the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the town population was 18,491. The United States Census Bureau considers Concord part of Greater Boston. The town center is n ...

, noted that "quite a little flock of assengerpigeons bred here last summer," while only seven years later, in 1866, one flock in southern Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

was described as being wide and long, took 14 hours to pass, and held in excess of 3.5 billion birds. Such a number would likely represent a large fraction of the entire population at the time, or perhaps all of it. Most estimations of numbers were based on single migrating colonies, and it is unknown how many of these existed at a given time. American writer Christopher Cokinos has suggested that if the birds flew single file, they would have stretched around the Earth 22 times.

A 2014 genetic study (based on coalescent theory

Coalescent theory is a Scientific modelling, model of how alleles sampled from a population may have originated from a most recent common ancestor, common ancestor. In the simplest case, coalescent theory assumes no genetic recombination, recombina ...

and on "sequences from most of the genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

" of three individual passenger pigeons) suggested that the passenger pigeon population experienced dramatic fluctuations across the last million years, due to their dependence on availability of mast (which itself fluctuates). The study suggested the bird was not always abundant, mainly persisting at around 1/10,000 the amount of the several billions estimated in the 1800s, with vastly larger numbers present during outbreak phases. Some early accounts also suggest that the appearance of flocks in great numbers was an irregular occurrence. These large fluctuations in population may have been the result of a disrupted ecosystem and have consisted of outbreak populations much larger than those common in pre-European times. The authors of the 2014 genetic study note that a similar analysis of the human population size arrives at an "effective population size

The effective population size (''N'e'') is the size of an idealised population that would experience the same rate of genetic drift as the real population. Idealised populations are those following simple one- locus models that comply with ass ...

" of between 9,000 and 17,000 individuals (or approximately 1/550,000th of the peak total human population size of 7 billion cited in the study).

For a 2017 genetic study, the authors sequenced the genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

s of two additional passenger pigeons, as well as analyzing the mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

of 41 individuals. This study found evidence that the passenger-pigeon population had been stable for at least the previous 20,000 years. The study also found that the size of the passenger pigeon population over that time period was larger than the found in the 2014 genetic study. However, the 2017 study's "conservative" estimate of an "effective population size

The effective population size (''N'e'') is the size of an idealised population that would experience the same rate of genetic drift as the real population. Idealised populations are those following simple one- locus models that comply with ass ...

" of 13 million birds is still only about 1/300th of the bird's estimated historic population of approximately 3–5 billion before their "19th century decline and eventual extinction." A similar study inferring human population size from genetics (published in 2008, and using human mitochondrial DNA and Bayesian coalescent

''Coalescent'' is a science-fiction novel by Stephen Baxter. It is part one of the '' Destiny's Children'' series. The story is set in two main time periods: modern Britain, when George Poole finds that he has a previously unknown sister and ...

inference methods) showed considerable accuracy in reflecting overall patterns of human population growth as compared to data deduced by other means—though the study arrived at a human effective population size

The effective population size (''N'e'') is the size of an idealised population that would experience the same rate of genetic drift as the real population. Idealised populations are those following simple one- locus models that comply with ass ...

(as of 1600 AD, for Africa, Eurasia, and the Americas combined) that was roughly 1/1000 of the census population estimate for the same time and area based on anthropological and historical evidence.

The 2017 passenger-pigeon genetic study also found that, in spite of its large population size, the genetic diversity was very low in the species. The authors suggested that this was a side-effect of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, which theory and previous empirical studies suggested could have a particularly great impact on species with very large and cohesive populations. Natural selection can reduce genetic diversity over extended regions of a genome through 'selective sweep

In genetics, a selective sweep is the process through which a new beneficial mutation that increases its frequency and becomes fixed (i.e., reaches a frequency of 1) in the population leads to the reduction or elimination of genetic variation amon ...

s' or ' background selection'. The authors found evidence of a faster rate of adaptive evolution and faster removal of harmful mutations in passenger pigeons compared to band-tailed pigeons, which are some of passenger pigeons' closest living relatives. They also found evidence of lower genetic diversity in regions of the passenger pigeon genome that have lower rates of genetic recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryot ...

. This is expected if natural selection, via selective sweep

In genetics, a selective sweep is the process through which a new beneficial mutation that increases its frequency and becomes fixed (i.e., reaches a frequency of 1) in the population leads to the reduction or elimination of genetic variation amon ...

s or background selection, reduced their genetic diversity, but not if population instability did. The study concluded that earlier suggestion that population instability contributed to the extinction of the species was invalid. Evolutionary biologist A. Townsend Peterson said of the two passenger-pigeon genetic studies (published in 2014 and 2017) that, though the idea of extreme fluctuations in the passenger-pigeon population was "deeply entrenched," he was persuaded by the 2017 study's argument, due to its "in-depth analysis" and "massive data resources."