Nabokov Award on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

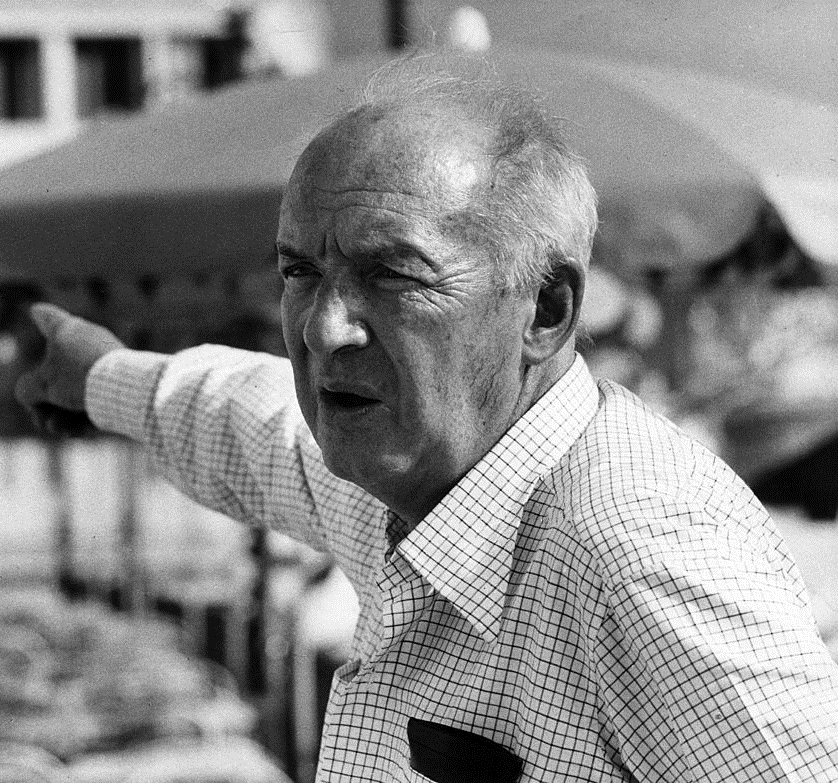

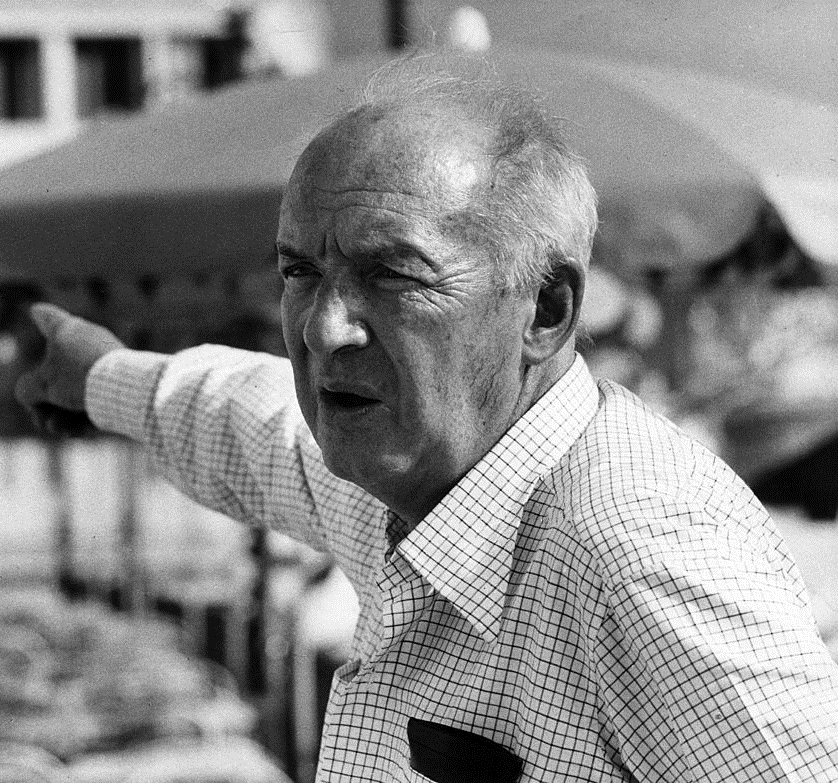

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov ( ; 2 July 1977), also known by the

Nabokov was born on 22 April 1899 (10 April 1899

Nabokov was born on 22 April 1899 (10 April 1899

Nabokov is known as one of the leading prose stylists of the 20th century; his first writings were in Russian, but he achieved his greatest fame with the novels he wrote in English. As a trilingual (also writing in French, see '' Mademoiselle O'') master, he has been compared to

Nabokov is known as one of the leading prose stylists of the 20th century; his first writings were in Russian, but he achieved his greatest fame with the novels he wrote in English. As a trilingual (also writing in French, see '' Mademoiselle O'') master, he has been compared to

Nabokov's lectures at

Nabokov's lectures at

The Russian literary critic Yuly Aykhenvald was an early admirer of Nabokov, citing in particular his ability to imbue objects with life: "he saturates trivial things with life, sense and psychology and gives a mind to objects; his refined senses notice colorations and nuances, smells and sounds, and everything acquires an unexpected meaning and truth under his gaze and through his words." The critic James Wood argues that Nabokov's use of descriptive detail proved an "overpowering, and not always very fruitful, influence on two or three generations after him", including authors such as

The Russian literary critic Yuly Aykhenvald was an early admirer of Nabokov, citing in particular his ability to imbue objects with life: "he saturates trivial things with life, sense and psychology and gives a mind to objects; his refined senses notice colorations and nuances, smells and sounds, and everything acquires an unexpected meaning and truth under his gaze and through his words." The critic James Wood argues that Nabokov's use of descriptive detail proved an "overpowering, and not always very fruitful, influence on two or three generations after him", including authors such as

;Main works written in Russian

* (1926) ''

;Main works written in Russian

* (1926) ''

«Nabokov le Nietzschéen»

, HERMANN, Paris, 2010

СПб.: Алетейя, 2011 312 с. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

"Vladimir Nabokov: More Chess Problems and the Novel"

''Yale French Studies'', No. 58, In Memory of Jacques Ehrmann: Inside Play Outside Game (1979), pp. 102–115, Yale University Press.

Vladimir-Nabokov.org

– Site of the Vladimir Nabokov French Society, Enchanted Researchers (Société française Vladimir Nabokov : Les Chercheurs Enchantés).

"Nabokov under Glass"

– New York Public Library exhibit. *

– Review of ''Nabokov's Butterflies''

The

Vladimir Nabokov poetry

*

Nabokov Online Journal

"The problem with Nabokov"

By

"Talking about Nabokov"

George Feifer,

"The Gay Nabokov"

''Salon'' Magazine 17 May 2000

BBC interviews 4 October 1969

Nabokov Bibliography: All About Vladimir Nabokov in Print

*

Vladmir Nabokov chess compositions

a

YACPDB

The Nabokovian (International Vladimir Nabokovian Society)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nabokov, Vladimir 1899 births 1977 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American poets 20th-century Russian novelists 20th-century Russian poets Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge American agnostics American alternate history writers American chess players American entomologists American literary critics American male dramatists and playwrights American male non-fiction writers American male novelists American male poets American male short story writers American translators American writers of Russian descent Chess composers Cornell University faculty English–Russian translators Exophonic writers French emigrants to the United States Fyodor Dostoyevsky scholars Emigrants from Nazi Germany to France Harvard University staff Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Germany Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Switzerland Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States Russian lepidopterists Literary translators Naturalized citizens of the United States Novelists from Massachusetts Novelists from New York (state) Novelists from Oregon People associated with the American Museum of Natural History People from Montreux Postmodern writers Russian people of Tatar descent Baltic-German people from the Russian Empire Russian agnostics Russian alternate history writers Russian anti-communists Russian chess players Russian literary critics Russian male dramatists and playwrights Russian male novelists Russian male poets Russian male short story writers Russian refugees Translators from English Translators from French Translators from Old East Slavic Translators from Russian Translators of Alexander Pushkin Translators of The Tale of Igor's Campaign Wellesley College faculty Writers from Ashland, Oregon Writers from Saint Petersburg 20th-century Russian memoirists 20th-century Russian translators 20th-century American zoologists 20th-century American male writers 20th-century pseudonymous writers Nobility from the Russian Empire 20th-century American memoirists 20th-century chess players

pen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian and American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

. Born in Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

in 1899, Nabokov wrote his first nine novels in Russian (1926–1938) while living in Berlin, where he met his wife, Véra Nabokov

Véra Yevseyevna Nabokova (née Slonim, ; 5 January 1902 – 7 April 1991) was the wife, editor, and translator of Russian writer Vladimir Nabokov, and a source of inspiration for many of his works.

Early life and immigration

Born Vera Yevs ...

. He achieved international acclaim and prominence after moving to the United States, where he began writing in English. Trilingual in Russian, English, and French, Nabokov became a U.S. citizen in 1945 and lived mostly on the East Coast before returning to Europe in 1961, where he settled in Montreux

Montreux (, ; ; ) is a Municipalities of Switzerland, Swiss municipality and List of towns in Switzerland, town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Swiss Alps, Alps. It belongs to the Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut (district), Riviera-Pays ...

, Switzerland.

From 1948 to 1959, Nabokov was a professor of Russian literature at Cornell University. His 1955 novel ''Lolita

''Lolita'' is a 1955 novel written by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov. The protagonist and narrator is a French literature professor who moves to New England and writes under the pseudonym Humbert Humbert. He details his obsession ...

'' ranked fourth on Modern Library

The Modern Library is an American book publishing Imprint (trade name), imprint and formerly the parent company of Random House. Founded in 1917 by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright as an imprint of their publishing company Boni & Liveright, Moder ...

's list of the 100 best 20th-century novels in 1998 and is considered one of the greatest works of 20th-century literature. Nabokov's ''Pale Fire

''Pale Fire'' is a 1962 novel by Vladimir Nabokov. The novel is presented as a 999-line poem titled "Pale Fire", written by the fictional poet John Shade, with a foreword, lengthy commentary and index written by Shade's neighbor and academic co ...

'', published in 1962, ranked 53rd on the same list. His memoir, ''Speak, Memory

''Speak, Memory'' is a memoir by writer Vladimir Nabokov. The book includes individual essays published between 1936 and 1951 to create the first edition in 1951. Nabokov's revised and extended edition appeared in 1966.

Scope

The book is dedi ...

'', published in 1951, is considered among the greatest nonfiction works of the 20th century, placing eighth on Random House

Random House is an imprint and publishing group of Penguin Random House. Founded in 1927 by businessmen Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer as an imprint of Modern Library, it quickly overtook Modern Library as the parent imprint. Over the foll ...

's ranking of 20th-century works. Nabokov was a seven-time finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction

The National Book Award for Fiction is one of five annual National Book Awards, which recognize outstanding literary work by United States citizens. Since 1987, the awards have been administered and presented by the National Book Foundation, bu ...

. He also was an expert lepidopterist

Lepidopterology ()) is a branch of entomology concerning the scientific study of moths and the two superfamilies of butterflies. Someone who studies in this field is a lepidopterist or, archaically, an aurelian.

Origins

Post-Renaissance, the r ...

and composer of chess problems. ''Time'' magazine wrote that Nabokov had "evolved a vivid English style which combines Joycean word play with a Proustian evocation of mood and setting".

Early life and education

Russia

Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, they refer to the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries betwe ...

) in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

to a wealthy and prominent family of the Russian nobility

The Russian nobility or ''dvoryanstvo'' () arose in the Middle Ages. In 1914, it consisted of approximately 1,900,000 members, out of a total population of 138,200,000. Up until the February Revolution of 1917, the Russian noble estates staffed ...

. His family traced its roots to the 14th-century Tatar

Tatar may refer to:

Peoples

* Tatars, an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar"

* Volga Tatars, a people from the Volga-Ural region of western Russia

* Crimean Tatars, a people from the Crimea peninsula by the B ...

prince Nabok Murza, who entered into the service of the Tsars, and from whom the family name is derived. His father was Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov

Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (; – 28 March 1922) was a Russian criminologist, journalist, and progressive statesman during the last years of the Russian Empire. He was the father of Russian-American author Vladimir Nabokov.

Early life ...

, a liberal lawyer, statesman, and journalist, and his mother was the heiress Yelena Ivanovna ''née'' Rukavishnikova, the granddaughter of a millionaire gold-mine owner. His father was a leader of the pre-Revolutionary liberal Constitutional Democratic Party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchy—among other policies� ...

, and wrote numerous books and articles about criminal law and politics. His cousins included the composer Nicolas Nabokov. His paternal grandfather, Dmitry Nabokov, was Russia's Justice Minister during the reign of Alexander II. His paternal grandmother was the Baltic German

Baltic Germans ( or , later ) are Germans, ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950), their resettlement in 1945 after the end ...

Baroness Maria von Korff. Through his father, he was a descendant of the composer Carl Heinrich Graun

Carl Heinrich Graun (7 May 1704 – 8 August 1759) was a German composer and tenor. Along with Johann Adolph Hasse, he is considered to be the most important German composer of Italian opera of his time.

Biography

Graun was born in Wahrenbrüc ...

.

Vladimir was the family's eldest and favorite child. He had four younger siblings: Sergey, Olga, Elena, and Kirill. Sergey was killed in a Nazi concentration camp in 1945 after publicly denouncing Hitler's regime. Writer Ayn Rand

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum; , 1905March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and philosopher. She is known for her fiction and for developing a philosophical system which s ...

recalled Olga (her close friend at Stoiunina Gymnasium) as a supporter of constitutional monarchy who first awakened Rand's interest in politics. Elena, who in later years became Vladimir's favorite sibling, published her correspondence with him in 1985. She was an important source for Nabokov's biographers.

Nabokov spent his childhood and youth in Saint Petersburg and at the country estate Vyra near Siverskaya, south of the city. His childhood, which he called "perfect" and "cosmopolitan", was remarkable in several ways. The family spoke Russian, English, and French in their household, and Nabokov was trilingual from an early age. He related that the first English book his mother read to him was ''Misunderstood'', by Florence Montgomery

Florence Montgomery (1843–1923) was an English novelist and children's writer. Her 1869 novel ''Misunderstood'' was enjoyed by Lewis Carroll and George du Maurier, and by Vladimir Nabokov as a child. Her writings are pious in tone and set in f ...

. Much to his patriotic father's disappointment, Nabokov could read and write in English before he could in Russian. In his memoir ''Speak, Memory

''Speak, Memory'' is a memoir by writer Vladimir Nabokov. The book includes individual essays published between 1936 and 1951 to create the first edition in 1951. Nabokov's revised and extended edition appeared in 1966.

Scope

The book is dedi ...

'', Nabokov recalls numerous details of his privileged childhood. His ability to recall his past in vivid detail was a boon to him during his permanent exile, providing a theme that runs from his first book, ''Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a female given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religion

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also called the Blesse ...

'', to later works such as '' Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle''. While the family was nominally Orthodox, it had little religious fervor. Vladimir was not forced to attend church after he lost interest.

In 1916, Nabokov inherited the estate Rozhdestveno, next to Vyra, from his uncle Vasily Ivanovich Rukavishnikov ("Uncle Ruka" in ''Speak, Memory

''Speak, Memory'' is a memoir by writer Vladimir Nabokov. The book includes individual essays published between 1936 and 1951 to create the first edition in 1951. Nabokov's revised and extended edition appeared in 1966.

Scope

The book is dedi ...

''). He lost it in the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

one year later; this was the only house he ever owned.

Nabokov's adolescence was the period in which he made his first serious literary endeavors. In 1916, he published his first book, ''Stikhi'' (''Poems''), a collection of 68 Russian poems. At the time he was attending Tenishev school in Saint Petersburg, where his literature teacher Vladimir Vasilievich Gippius had criticized his literary accomplishments. Some time after the publication of ''Stikhi'', Zinaida Gippius

Zinaida Nikolayevna Gippius (; – 9 September 1945), a Russian poet, playwright, novelist, editor and religious thinker, became one of the major figures in Russian symbolism.

She began writing at an early age, and by the time she met Dmitry ...

, renowned poet and first cousin of his teacher, told Nabokov's father at a social event, "Please tell your son that he will never be a writer."

After the 1917 February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

, Nabokov's father became a secretary of the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

in Saint Petersburg.

October Revolution

After theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, the family fled the city for Crimea, at first not expecting to be away for very long. They lived at a friend's estate and in September 1918 moved to Livadiya, at the time under the separatist Crimean Regional Government

The Crimean Regional Government ( ') refers to two successive short-lived regimes in the Crimean Peninsula during 1918 and 1919.

History

Following Russia's 1917 October Revolution, an ethnic Tatar government proclaimed the Crimean People's Rep ...

, in which Nabokov's father became a minister of justice.

University of Cambridge

After the withdrawal of theGerman Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

in November 1918 and the defeat of the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

in early 1919, the Nabokovs sought exile in western Europe, along with other Russian refugees. They settled briefly in England, where Nabokov gained admittance to the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, one of the world's most prestigious universities, where he attended Trinity College and studied zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

and later Slavic and Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

. His examination results on the first part of the Tripos

TRIPOS (''TRIvial Portable Operating System'') is a computer operating system. Development started in 1976 at the Computer Laboratory of Cambridge University and it was headed by Dr. Martin Richards. The first version appeared in January 1978 a ...

exam, taken at the end of his second year, were a starred first

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied, sometimes with significant var ...

. He took the second part of the exam in his fourth year just after his father's death, and feared he might fail it. But his exam was marked second-class. His final examination result also ranked second-class, and his BA was conferred in 1922. Nabokov later drew on his Cambridge experiences to write several works, including the novels '' Glory'' and '' The Real Life of Sebastian Knight''.

At Cambridge, one journalist wrote in 2014, "the coats-of-arms on the windows of his room protected him from the cold and from the melancholy over the recent loss of his country. It was in this city, in his moments of solitude, accompanied by ''King Lear'', ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', ''The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' or ''Ulysses'', that Nabokov made the firm decision to become a Russian writer."

Career

Berlin (1922–1937)

In 1920, Nabokov's family moved to Berlin, where his father set up the émigré newspaper ''Rul ("Rudder"). Nabokov followed them to Berlin two years later, after completing his studies at Cambridge. In March 1922, Russian monarchists Pyotr Shabelsky-Bork andSergey Taboritsky

Sergey Vladimirovich Taboritsky (; 12 August 1897 – 16 October 1980) was a Russian journalist, renowned for his nationalist, monarchist, and antisemitic positions. From 1936 to 1945, he was the deputy of the Bureau for the Russian Refugees in ...

shot and killed Nabokov's father in Berlin as he was shielding their target, Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the C ...

, a leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchy—among other policies� ...

-in-exile. Shortly after his father's death, Nabokov's mother and sister moved to Prague. Nabokov drew upon his father's death repeatedly in his fiction. On one interpretation of his novel ''Pale Fire

''Pale Fire'' is a 1962 novel by Vladimir Nabokov. The novel is presented as a 999-line poem titled "Pale Fire", written by the fictional poet John Shade, with a foreword, lengthy commentary and index written by Shade's neighbor and academic co ...

'', an assassin kills the poet John Shade when his target is a fugitive European monarch.

Nabokov stayed in Berlin, where he had become a recognised poet and writer in Russian within the émigré community; he published under the ''nom de plume'' V. Sirin (a reference to the fabulous bird of Russian folklore). To supplement his scant writing income, he taught languages and gave tennis and boxing lessons. Dieter E. Zimmer has written of Nabokov's 15 Berlin years, "he never became fond of Berlin, and at the end intensely disliked it. He lived within the lively Russian community of Berlin that was more or less self-sufficient, staying on after it had disintegrated because he had nowhere else to go to. He knew little German. He knew few Germans except for landladies, shopkeepers, and immigration officials at the police headquarters."

Marriage

In 1922, Nabokov became engaged to Svetlana Siewert, but she broke the engagement off early in 1923 when her parents worried whether he could provide for her. In May 1923, he met Véra Evseyevna Slonim, a Russian-Jewish woman, at a charity ball in Berlin.. They married in April 1925. Their only child,Dmitri

Dmitry (); Church Slavic form: Dimitry or Dimitri (); ancient Russian forms: D'mitriy or Dmitr ( or ) is a male given name common in Orthodox Christian culture, the Russian version of Demetrios (, ). The meaning of the name is "devoted to, de ...

, was born in 1934.

In the course of 1936, Véra lost her job because of the increasingly antisemitic environment; Sergey Taboritsky

Sergey Vladimirovich Taboritsky (; 12 August 1897 – 16 October 1980) was a Russian journalist, renowned for his nationalist, monarchist, and antisemitic positions. From 1936 to 1945, he was the deputy of the Bureau for the Russian Refugees in ...

was appointed deputy head of Germany's Russian-émigré bureau; and Nabokov began seeking a job in the English-speaking world.

France (1937–1940)

In 1937, Nabokov left Germany for France, where he had a short affair with Irina Guadanini, also a Russian émigrée. His family followed him to France, making en route their last visit toPrague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, then spent time in Cannes

Cannes (, ; , ; ) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a communes of France, commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions Internatio ...

, Menton

Menton (; in classical norm or in Mistralian norm, , ; ; or depending on the orthography) is a Commune in France, commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italia ...

, Cap d'Antibes, and Fréjus

Fréjus (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Var (department), Var Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region in Southeastern France.

It neighbours Saint-Raphaël, Var, Saint-Raphaël ...

, finally settling in Paris. This city also had a Russian émigré community.

In 1939, in Paris, Nabokov wrote the 55-page novella ''The Enchanter

''The Enchanter'' () is a novella written by Vladimir Nabokov in Paris in 1939. It was his last work of fiction written in Russian. Nabokov never published it during his lifetime. After his death, his son Dmitri translated the novella into Eng ...

'', his final work of Russian fiction. He later called it "the first little throb of ''Lolita''."

In May 1940, the Nabokovs fled the advancing German troops, reaching the United States via the SS ''Champlain''. Nabokov's brother Sergey did not leave France, and he died at the Neuengamme concentration camp

Neuengamme was a network of Nazi concentration camps in northern Germany that consisted of the main camp, Neuengamme, and List of subcamps of Neuengamme, more than 85 satellite camps. Established in 1938 near the village of Neuengamme, Hamburg, N ...

on 9 January 1945.

United States

New York City (1940–1941)

The Nabokovs settled inManhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

, and Vladimir began volunteer work as an entomologist

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

.

Wellesley College (1941–1948)

Nabokov joined the staff ofWellesley College

Wellesley College is a Private university, private Women's colleges in the United States, historically women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1870 by Henr ...

in 1941 as resident lecturer in comparative literature

Comparative literature studies is an academic field dealing with the study of literature and cultural expression across language, linguistic, national, geographic, and discipline, disciplinary boundaries. Comparative literature "performs a role ...

. The position, created specifically for him, provided an income and free time to write creatively and pursue his lepidoptery

Lepidopterology ()) is a branch of entomology concerning the scientific study of moths and the two superfamilies of butterflies. Someone who studies in this field is a lepidopterist or, archaically, an aurelian.

Origins

Post-Renaissance, the r ...

. Nabokov is remembered as the founder of Wellesley's Russian department. The Nabokovs resided in Wellesley, Massachusetts

Wellesley () is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. Wellesley is part of the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The population was 29,550 at the time of the 2020 census. Wellesley College, Babson College, and a campus of M ...

, during the 1941–42 academic year. In September 1942, they moved to nearby Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, where they lived until June 1948. Following a lecture tour through the United States, Nabokov returned to Wellesley for the 1944–45 academic year as a lecturer in Russian. In 1945, he became a naturalized citizen

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

of the United States. He served through the 1947–48 term as Wellesley's one-man Russian department, offering courses in Russian language and literature. His classes were popular, due as much to his unique teaching style as to the wartime interest in all things Russian. At the same time he was the de facto curator of lepidoptery at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

's Museum of Comparative Zoology

The Museum of Comparative Zoology (formally the Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology and often abbreviated to MCZ) is a zoology museum located on the grounds of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is one of three natural-history r ...

.

Cornell University (1948–1959)

After being encouraged byMorris Bishop

Morris Gilbert Bishop (April 15, 1893 – November 20, 1973) was an American scholar who wrote numerous books on Romance history, literature, and biography. His work also extended to North American exploration and beyond.

Orphaned at 12, he ...

, Nabokov left Wellesley in 1948 to teach Russian and European literature at Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

, where he taught until 1959. Among his students at Cornell was future U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

Justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; Bader; March 15, 1933 – September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until Death and state funeral of Ruth Bader ...

, who later identified Nabokov as a major influence on her development as a writer.

Nabokov wrote ''Lolita

''Lolita'' is a 1955 novel written by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov. The protagonist and narrator is a French literature professor who moves to New England and writes under the pseudonym Humbert Humbert. He details his obsession ...

'' while traveling on the butterfly-collection trips in the western U.S. that he undertook every summer. Véra acted as "secretary, typist, editor, proofreader, translator and bibliographer; his agent, business manager, legal counsel and chauffeur; his research assistant, teaching assistant and professorial understudy"; when Nabokov attempted to burn unfinished drafts of ''Lolita'', Véra stopped him. He called her the best-humored woman he had ever known.

In June 1953, Nabokov and his family went to Ashland, Oregon

Ashland is a city in Jackson County, Oregon, United States. It lies along Interstate 5 in Oregon, Interstate 5 approximately 16 miles (26 km) north of the California border and near the south end of the Rogue Valley. The city's population w ...

. There he finished ''Lolita'' and began writing the novel '' Pnin''. He roamed the nearby mountains looking for butterflies, and wrote a poem called "Lines Written in Oregon". On 1 October 1953, he and his family returned to Ithaca, where he later taught the young writer Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr. ( , ; born May 8, 1937) is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, Literary genre, genres and Theme (narrative), th ...

.

Montreux (1961–1977)

After the great financial success of ''Lolita'', Nabokov returned to Europe and devoted himself to writing. In 1961, he and Véra moved to the Montreux Palace Hotel inMontreux

Montreux (, ; ; ) is a Municipalities of Switzerland, Swiss municipality and List of towns in Switzerland, town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Swiss Alps, Alps. It belongs to the Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut (district), Riviera-Pays ...

, Switzerland, where he remained until the end of his life. From his sixth-floor quarters, he conducted his business and took tours to the Alps, Corsica, and Sicily to hunt butterflies.

Death

Nabokov died of bronchitis on 2 July 1977 in Montreux. His remains were cremated and buried at Clarens cemetery in Montreux. At the time of his death, he was working on a novel titled '' The Original of Laura''. Véra and Dmitri, who were entrusted with Nabokov'sliterary executor

The literary estate of a deceased author consists mainly of the copyright and other intellectual property rights of published works, including film rights, film, translation rights, original manuscripts of published work, unpublished or partially ...

ship, ignored Nabokov's request to burn the incomplete manuscript and published it in 2009.

Works

Critical reception and writing style

Nabokov is known as one of the leading prose stylists of the 20th century; his first writings were in Russian, but he achieved his greatest fame with the novels he wrote in English. As a trilingual (also writing in French, see '' Mademoiselle O'') master, he has been compared to

Nabokov is known as one of the leading prose stylists of the 20th century; his first writings were in Russian, but he achieved his greatest fame with the novels he wrote in English. As a trilingual (also writing in French, see '' Mademoiselle O'') master, he has been compared to Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

, but Nabokov disliked both the comparison and Conrad's work. He lamented to the critic Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson Jr. (May 8, 1895 – June 12, 1972) was an American writer, literary critic, and journalist. He is widely regarded as one of the most important literary critics of the 20th century. Wilson began his career as a journalist, writing ...

, "I am too old to change Conradically"—which John Updike

John Hoyer Updike (March 18, 1932 – January 27, 2009) was an American novelist, poet, short-story writer, art critic, and literary critic. One of only four writers to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction more than once (the others being Booth Tar ...

later called "itself a jest of genius". This lament came in 1941, when Nabokov had been an apprentice American for less than one year. Later, in a November 1950 letter to Wilson, Nabokov offers a solid, non-comic appraisal: "Conrad knew how to handle readymade English better than I; but I know better the other kind. He never sinks to the depths of my solecisms, but neither does he scale my verbal peaks." Nabokov translated many of his own early works into English, sometimes in collaboration with his son, Dmitri. His trilingual upbringing had a profound influence on his art.

Nabokov himself translated into Russian two books he originally wrote in English, ''Conclusive Evidence'' and ''Lolita''. The "translation" of ''Conclusive Evidence'' was made because Nabokov felt that the English version was imperfect. Writing the book, he noted that he needed to translate his own memories into English and to spend time explaining things that are well known in Russia; he decided to rewrite the book in his native language before making the final version, ''Speak, Memory

''Speak, Memory'' is a memoir by writer Vladimir Nabokov. The book includes individual essays published between 1936 and 1951 to create the first edition in 1951. Nabokov's revised and extended edition appeared in 1966.

Scope

The book is dedi ...

'' (Nabokov first wanted to name it "Speak, Mnemosyne

In Greek mythology and ancient Greek religion, Mnemosyne (; , ) is the goddess of memory and the mother of the nine Muses by her nephew Zeus. In the Greek tradition, Mnemosyne is one of the Titans, the twelve divine children of the earth-godde ...

"). Of translating ''Lolita'', Nabokov writes, "I imagined that in some distant future somebody might produce a Russian version of ''Lolita''. I trained my inner telescope upon that particular point in the distant future and I saw that every paragraph, pock-marked as it is with pitfalls, could lend itself to hideous mistranslation. In the hands of a harmful drudge, the Russian version of ''Lolita'' would be entirely degraded and botched by vulgar paraphrases or blunders. So I decided to translate it myself."

Nabokov was a proponent of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, and rejected concepts and ideologies that curtailed individual freedom and expression, such as totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public s ...

in its various forms, as well as Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

's psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

. '' Poshlost'', or as he transcribed it, ''poshlust'', is disdained and frequently mocked in his works.

Nabokov's creative processes involved writing sections of text on hundreds of index card

An index card (or record card in British English and system cards in Australian English) consists of card stock (heavy paper) cut to a standard size, used for recording and storing small amounts of discrete data. A collection of such cards ei ...

s, which he expanded into paragraphs and chapters and rearranged to form the structure of his novels, a process that many screenwriters later adopted.

Nabokov published under the pseudonym Vladimir Sirin in the 1920s to 1940s, occasionally to mask his identity from critics. He also makes cameo appearances in some of his novels, such as the character Vivian Darkbloom (an anagram

An anagram is a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase, typically using all the original letters exactly once. For example, the word ''anagram'' itself can be rearranged into the phrase "nag a ram"; which ...

of "Vladimir Nabokov"), who appears in both ''Lolita'' and ''Ada, or Ardor'', and the character Blavdak Vinomori (another anagram of Nabokov's name) in ''King, Queen, Knave''. Sirin is referenced as a different émigré author in his memoir and is also referenced in ''Pnin''.

Nabokov is noted for his complex plots, clever word play

Word play or wordplay (also: play-on-words) is a literary technique and a form of wit in which words used become the main subject of the work, primarily for the purpose of intended effect or amusement. Examples of word play include puns, ph ...

, daring metaphors, and prose style capable of both parody and intense lyricism. He gained both fame and notoriety with ''Lolita'' (1955), which recounts a grown man's consuming passion for a 12-year-old girl. This and his other novels, particularly ''Pale Fire

''Pale Fire'' is a 1962 novel by Vladimir Nabokov. The novel is presented as a 999-line poem titled "Pale Fire", written by the fictional poet John Shade, with a foreword, lengthy commentary and index written by Shade's neighbor and academic co ...

'' (1962), won him a place among the greatest novelists of the 20th century and multiple nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

.

His longest novel, which met with a mixed response, is '' Ada'' (1969). He devoted more time to the composition of it than to any other. Nabokov's fiction is characterized by linguistic playfulness. For example, his short story " The Vane Sisters" is famous in part for its acrostic

An acrostic is a poem or other word composition in which the ''first'' letter (or syllable, or word) of each new line (or paragraph, or other recurring feature in the text) spells out a word, message or the alphabet. The term comes from the Fre ...

final paragraph, in which the words' first letters spell a message from beyond the grave. Another of his short stories, "Signs and Symbols

"Signs and Symbols" is a short story by Vladimir Nabokov, written in English and first published, May 15, 1948 in ''The New Yorker'' and then in '' Nabokov's Dozen'' (1958: Doubleday & Company, Garden City, New York).

In ''The New Yorker'', the ...

", features a character suffering from an imaginary illness called "Referential Mania", in which the affected perceives a world of environmental objects exchanging coded messages.

Nabokov's stature as a literary critic is founded largely on his four-volume translation of and commentary on Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

's ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (, Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: Евгеній Онѣгинъ, романъ въ стихахъ, ) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. ''Onegin'' is considered a classic of ...

'' published in 1964. The commentary ends with an appendix titled ''Notes on Prosody

The book ''Notes on Prosody'' by author Vladimir Nabokov compares differences in Iamb (foot), iambic verse in the English language, English and Russian languages, and highlights the effect of relative word length in the two languages on rhythm. N ...

'', which has developed a reputation of its own. It stemmed from his observation that while Pushkin's iambic tetrameter

Iambic tetrameter is a meter (poetry), poetic meter in Ancient Greek poetry, ancient Greek and Latin poetry; as the name of ''a rhythm'', iambic tetrameter consists of four metra, each metron being of the form , x – u – , , consisting of a spo ...

s had been a part of Russian literature

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia, its Russian diaspora, émigrés, and to Russian language, Russian-language literature. Major contributors to Russian literature, as well as English for instance, are authors of different e ...

for a fairly short two centuries, they were clearly understood by the Russian prosodists. On the other hand, he viewed the much older English iambic tetrameters as muddled and poorly documented. In his own words:

Cornell University lectures

Nabokov's lectures at

Nabokov's lectures at Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

, as collected in ''Lectures on Literature'', reveal his controversial ideas concerning art. He firmly believed that novels should not aim to teach and that readers should not merely empathize with characters but that a 'higher' aesthetic enjoyment should be attained, partly by paying great attention to details of style and structure. He detested what he saw as 'general ideas' in novels, and so when teaching '' Ulysses'', for example, he would insist students keep an eye on where the characters were in Dublin (with the aid of a map) rather than teaching the complex Irish history that many critics see as being essential to an understanding of the novel. In 2010, ''Kitsch'' magazine, a student publication at Cornell, published a piece that focused on student reflections on his lectures and also explored Nabokov's long relationship with ''Playboy

''Playboy'' (stylized in all caps) is an American men's Lifestyle journalism, lifestyle and entertainment magazine, available both online and in print. It was founded in Chicago in 1953 by Hugh Hefner and his associates, funded in part by a $ ...

''. Nabokov also wanted his students to describe the details of the novels rather than a narrative of the story and was very strict when it came to grading. As Edward Jay Epstein

Edward Jay Epstein (December 6, 1935 – January 9, 2024) was an American investigative journalist and a political science professor at Harvard University, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ...

described his experience in Nabokov's classes, Nabokov made it clear from the first lectures that he had little interest in fraternizing with students, who would be known not by their name but by their seat number.

Influence

The Russian literary critic Yuly Aykhenvald was an early admirer of Nabokov, citing in particular his ability to imbue objects with life: "he saturates trivial things with life, sense and psychology and gives a mind to objects; his refined senses notice colorations and nuances, smells and sounds, and everything acquires an unexpected meaning and truth under his gaze and through his words." The critic James Wood argues that Nabokov's use of descriptive detail proved an "overpowering, and not always very fruitful, influence on two or three generations after him", including authors such as

The Russian literary critic Yuly Aykhenvald was an early admirer of Nabokov, citing in particular his ability to imbue objects with life: "he saturates trivial things with life, sense and psychology and gives a mind to objects; his refined senses notice colorations and nuances, smells and sounds, and everything acquires an unexpected meaning and truth under his gaze and through his words." The critic James Wood argues that Nabokov's use of descriptive detail proved an "overpowering, and not always very fruitful, influence on two or three generations after him", including authors such as Martin Amis

Sir Martin Louis Amis (25 August 1949 – 19 May 2023) was an English novelist, essayist, memoirist, screenwriter and critic. He is best known for his novels ''Money'' (1984) and '' London Fields'' (1989). He received the James Tait Black Mem ...

and John Updike

John Hoyer Updike (March 18, 1932 – January 27, 2009) was an American novelist, poet, short-story writer, art critic, and literary critic. One of only four writers to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction more than once (the others being Booth Tar ...

. While a student at Cornell in the 1950s, Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr. ( , ; born May 8, 1937) is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, Literary genre, genres and Theme (narrative), th ...

attended several of Nabokov's lectures. His debut novel '' V.'' resembles '' The Real Life of Sebastian Knight'' in plot, character, narration and style, and the title alludes directly to the narrator "V." in that novel. Pynchon also alluded to ''Lolita'' in his 1966 novel ''The Crying of Lot 49

''The Crying of Lot 49'' is a novel by the American author Thomas Pynchon. It was published by J. B. Lippincott & Co. on April27, 1966. The shortest of Pynchon's novels, the plot follows Oedipa Maas, a young Californian woman who begins to embr ...

'', in which Serge, countertenor in the band the Paranoids, sings:

Pynchon's prose style was influenced by Nabokov's preference for actualism over realism. Of the authors who came to prominence during Nabokov's life, John Banville

William John Banville (born 8 December 1945) is an Irish novelist, short story writer, Literary adaptation, adapter of dramas and screenwriter. Though he has been described as "the heir to Marcel Proust, Proust, via Vladimir Nabokov, Nabokov", ...

, Don DeLillo

Donald Richard DeLillo (born November 20, 1936) is an American novelist, short story writer, playwright, screenwriter, and essayist. His works have covered subjects as diverse as consumerism, nuclear war, the complexities of language, art, televi ...

, Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie ( ; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British and American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern wor ...

, and Edmund White

Edmund Valentine White III (January 13, 1940 – June 3, 2025) was an American novelist, memoirist, playwright, biographer, and essayist. A pioneering figure in LGBTQ and especially gay literature after the Stonewall riots, he wrote with ra ...

were all influenced by him. The novelist John Hawkes took inspiration from Nabokov and considered himself his follower. Nabokov's story "Signs and Symbols" was on the reading list for Hawkes's writing students at Brown University. "A writer who truly and greatly sustains us is Vladimir Nabokov," Hawkes said in a 1964 interview.

Several authors who came to prominence in the 1990s and 2000s have also cited Nabokov's work as a literary influence. Aleksandar Hemon

Aleksandar Hemon ( sr-Cyrl, Александар Xeмoн; born September 9, 1964) is a Bosnian- American author, essayist, critic, television writer, and screenwriter. He is best known for the novels '' Nowhere Man'' (2002) and '' The Lazarus P ...

has acknowledged the latter's impact on his writing. Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

-winning novelist Michael Chabon

Michael Chabon ( ;

born May 24, 1963) is an American novelist, screenwriter, columnist, and short story writer. Born in Washington, D.C., he spent a year studying at Carnegie Mellon University before transferring to the University of Pittsburgh, ...

listed ''Lolita'' and ''Pale Fire'' among the "books that, I thought, changed my life when I read them", and has said, "Nabokov's English combines aching lyricism with dispassionate precision in a way that seems to render every human emotion in all its intensity but never with an ounce of schmaltz or soggy language". T. Coraghessan Boyle has said that "Nabokov's playfulness and the ravishing beauty of his prose are ongoing influences" on his writing. Bilingual author and critic Maxim D. Shrayer, who came to the U.S. as a refugee from the USSR, described reading Nabokov in 1987 as "my culture shock": "I was reading Nabokov and waiting for America." ''Boston Globe'' book critic David Mehegan wrote that Shrayer's ''Waiting for America'' "is one of those memoirs, like Nabokov's ''Speak, Memory'', that is more about feeling than narrative." More recently, in connection with the publication of Shrayer's literary memoir ''Immigrant Baggage'', the critic and Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American filmmaker and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, Stanley Kubrick filmography, his films were nearly all adaptations of novels or sho ...

biographer David Mikics wrote, "Shrayer writes like Nabokov's long lost cousin."

Nabokov appears in W. G. Sebald's 1993 novel '' The Emigrants''.

A crater

A crater is a landform consisting of a hole or depression (geology), depression on a planetary surface, usually caused either by an object hitting the surface, or by geological activity on the planet. A crater has classically been described ...

on the planet Mercury was named after Nabokov in 2012.

Adaptations

The song cycle "Sing, Poetry" on the 2011 contemporary classical album '' Troika'' comprises settings of Russian and English versions of three of Nabokov's poems by such composers as Jay Greenberg,Michael Schelle

Michael Schelle (pronounced ''Shelley''; born January 22, 1950, in Philadelphia), is a composer of contemporary concert music. He is also a performer, conductor, author, and teacher.

Background

Schelle grew up in Bergen County, in northern New ...

and Lev Zhurbin.

Entomology

Nabokov's interest inentomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

was inspired by books by Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Sibylla Merian (2 April 164713 January 1717) was a German Entomology, entomologist, naturalist and scientific illustrator. She was one of the earliest European naturalists to document observations about insects directly. Merian was a desce ...

he found in the attic of his family's country home in Vyra. Throughout an extensive career of collecting, he never learned to drive a car, and depended on his wife to take him to collecting sites. During the 1940s, as a research fellow in zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

, he was responsible for organizing the butterfly collection of Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

's Museum of Comparative Zoology

The Museum of Comparative Zoology (formally the Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology and often abbreviated to MCZ) is a zoology museum located on the grounds of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is one of three natural-history r ...

. His writings in this area were highly technical. This, combined with his specialty in the relatively unspectacular tribe Polyommatini

Polyommatini is a tribe of lycaenid butterflies in the subfamily of Polyommatinae. These were extensively studied by Russian novelist and lepidopterist Vladimir Nabokov.

Genera

Genera in this tribe include:

* '' Actizera''

* ''Acytolepis''

* ...

of the family Lycaenidae

Lycaenidae is the second-largest family (biology), family of butterflies (behind Nymphalidae, brush-footed butterflies), with over 6,000 species worldwide, whose members are also called gossamer-winged butterflies. They constitute about 30% of ...

, has left this facet of his life little explored by most admirers of his literary works. He described the Karner blue. The genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

'' Nabokovia'' was named after him in honor of this work, as were a number of butterfly and moth species (e.g., many species in the genera '' Madeleinea'' and ''Pseudolucia

''Pseudolucia'' is a genus of butterflies in the family Lycaenidae. They are predominantly found in parts of South America, south of Brazil. In many of the southern and western regions, stretching from Chile to Uruguay, habitat loss and pollutio ...

'' bear epithets alluding to Nabokov or names from his novels). In 1967, Nabokov commented: "The pleasures and rewards of literary inspiration are nothing beside the rapture of discovering a new organ under the microscope or an undescribed species on a mountainside in Iran or Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

. It is not improbable that had there been no revolution in Russia, I would have devoted myself entirely to lepidopterology and never written any novels at all."

The Harvard Museum of Natural History

The Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH) is a natural history museum housed in the University Museum Building, located on the campus of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It features 16 galleries with 12,000 specimens drawn fr ...

, which now contains the Museum of Comparative Zoology

The Museum of Comparative Zoology (formally the Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology and often abbreviated to MCZ) is a zoology museum located on the grounds of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is one of three natural-history r ...

, still possesses Nabokov's "genitalia cabinet", where the author stored his collection of male blue butterfly genitalia. "Nabokov was a serious taxonomist," says museum staff writer Nancy Pick, author of ''The Rarest of the Rare: Stories Behind the Treasures at the Harvard Museum of Natural History''. "He actually did quite a good job at distinguishing species that you would not think were different—by looking at their genitalia under a microscope six hours a day, seven days a week, until his eyesight was permanently impaired."

Though professional lepidopterists did not take Nabokov's work seriously during his life, new genetic research supports Nabokov's hypothesis that a group of butterfly species, called the ''Polyommatus

''Polyommatus'' is a genus of butterfly, butterflies in the family Lycaenidae.

Its species are found in the Palearctic realm.

Taxonomy

Recent molecular studies have demonstrated that ''Cyaniris'', ''Lysandra (butterfly), Lysandra'', and ''Neoly ...

'' blues, came to the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

over the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

in five waves, eventually reaching Chile.

Politics and views

Russian politics

Nabokov was aclassical liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, eco ...

, in the tradition of his father, a liberal statesman who served in the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

following the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

of 1917 as a member of the Constitutional Democratic Party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchy—among other policies� ...

. In ''Speak, Memory'', Nabokov proudly recounted his father's campaigns against despotism

In political science, despotism () is a government, form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute Power (social and political), power. Normally, that entity is an individual, the despot (as in an autocracy), but societies whi ...

and staunch opposition to capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

. Nabokov was a self-proclaimed " White Russian", and was, from its inception, a strong opponent of the Soviet government that came to power following the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. It was led by Vladimir L ...

of October 1917. In a poem he wrote as a teenager in 1917, he described Lenin's Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s as "grey rag-tag people".

Throughout his life, Nabokov would remain committed to the classical liberal political philosophy of his father, and equally opposed Tsarist autocracy

Tsarist autocracy (), also called Tsarism, was an autocracy, a form of absolute monarchy in the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire. In it, the Tsar possessed in principle authority an ...

, communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, and fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

. Nabokov's father, Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, was one of the most outspoken defenders of Jewish rights in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, continuing a family tradition that had been led by his own father, Dmitry Nabokov, who as Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland fro ...

's justice minister had blocked the interior minister from passing antisemitic measures. That family strain continued in Vladimir Nabokov, who fiercely denounced antisemitism in his writings; in the 1930s, he was able to escape Hitler's Germany only with the help of Russian Jewish

The history of the Jews in Russia and areas historically connected with it goes back at least 1,500 years. Jews in Russia have historically constituted a large religious and ethnic diaspora; the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest po ...

émigrés who still had grateful memories of his family's defense of Jews in Tsarist times.

When asked in 1969 whether he would like to revisit the land he fled in 1918, now the Soviet Union, he replied: "There's nothing to look at. New tenement houses and old churches do not interest me. The hotels there are terrible. I detest the Soviet theater. Any palace in Italy is superior to the repainted abodes of the Tsars. The village huts in the forbidden hinterland are as dismally poor as ever, and the wretched peasant flogs his wretched cart horse with the same wretched zest. As to my special northern landscape and the haunts of my childhood—well, I would not wish to contaminate their images preserved in my mind."

American politics

In the 1940s, as an émigré in America, Nabokov stressed the connection between American and English liberal democracy and the aspirations of the short-lived Russian provisional government. In 1942, he declared: "Democracy is humanity at its best ... it is the natural condition of every man ever since the human mind became conscious not only of the world but of itself." During the 1960s, in both letters and interviews, he reveals a profound contempt for theNew Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

movements, calling the protesters "conformists" and "goofy hoodlums". In a 1967 interview, Nabokov said that he refused to associate with supporters of Bolshevism or Tsarist autocracy but that he had "friends among intellectual constitutional monarchists as well as among intellectual social revolutionaries". Nabokov supported the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

effort and voiced admiration for both Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

and Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. Racism against African-Americans appalled Nabokov, who touted Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

's multiracial background as an argument against segregation.

Views on women writers

Nabokov's wife Véra was his strongest supporter and assisted him throughout his life, but Nabokov admitted to a "prejudice" against women writers. He wrote to Edmund Wilson, who had been making suggestions for his lectures: "I dislikeJane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

, and am prejudiced, in fact against all women writers. They are in another class." But after rereading Austen's ''Mansfield Park

''Mansfield Park'' is the third published novel by the English author Jane Austen, first published in 1814 by Thomas Egerton (publisher), Thomas Egerton. A second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray (publishing house), John Murray, st ...

'' he changed his mind and taught it in his literature course; he also praised Mary McCarthy's work and called Marina Tsvetaeva

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva ( rus, Марина Ивановна Цветаева, p=mɐˈrʲinə ɪˈvanəvnə tsvʲɪˈta(j)ɪvə, links=yes; 31 August 1941) was a Russian poet. Her work is some of the most well-known in twentieth-century Russ ...

a "poet of genius" in ''Speak, Memory''. Although Véra worked as his personal translator and secretary, he made publicly known that his ideal translator would be male, and especially not a "Russian-born female". In the first chapter of '' Glory'' he attributes the protagonist's similar prejudice to the impressions made by children's writers like Lidiya Charski, and the short story "The Admiralty Spire" deplores the posturing, snobbery, antisemitism, and cutesiness he considered characteristic of Russian women authors.

Personal life

Synesthesia

Nabokov was a self-described synesthete, who at a young age equated the number five with the color red. Aspects of synesthesia can be found in several of his works. His wife also exhibited synesthesia; like her husband, her mind's eye associated colors with particular letters. They discovered that Dmitri shared the trait, and moreover that the colors he associated with some letters were in some cases blends of his parents' hues—"which is as ifgene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s were painting in aquarelle

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin 'water'), is a painting method"Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to the S ...

". Nabokov also wrote that his mother had synesthesia, and that she had different letter-color pairs.

For some synesthetes, letters are not simply ''associated with'' certain colors, they ''are themselves'' colored. Nabokov frequently endowed his protagonists with a similar gift. In '' Bend Sinister'', Krug comments on his perception of the word "loyalty" as like a golden fork lying out in the sun. In ''The Defense'', Nabokov briefly mentions that the main character's father, a writer, found he was unable to complete a novel that he planned to write, becoming lost in the fabricated storyline by "starting with colors". Many other subtle references are made in Nabokov's writing that can be traced back to his synesthesia. Many of his characters have a distinct "sensory appetite" reminiscent of synesthesia.

Nabokov described his synesthesia at length in his autobiography ''Speak, Memory

''Speak, Memory'' is a memoir by writer Vladimir Nabokov. The book includes individual essays published between 1936 and 1951 to create the first edition in 1951. Nabokov's revised and extended edition appeared in 1966.

Scope

The book is dedi ...

'':

Religion

Nabokov was a religiousagnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, the divine, or the supernatural is either unknowable in principle or unknown in fact. (page 56 in 1967 edition) It can also mean an apathy towards such religious belief and refer to ...

. He was very open about, and received criticism for, his indifference to organized mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

, to religion, and to any church.

Sleep

Nabokov was a notorious, lifelong insomniac who admitted unease at the prospect of sleep, once saying, "the night is always a giant". Later in life his insomnia was exacerbated by an enlarged prostate. Nabokov called sleep a "moronic fraternity", "mental torture", and a "nightly betrayal of reason, humanity, genius". Insomnia's impact on his work has been widely explored, and in 2017Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial ...

published a compilation of his dream diary entries, ''Insomniac Dreams: Experiments with Time by Vladimir Nabokov''.

Chess problems

Nabokov spent considerable time during his exile composingchess problem

A chess problem, also called a chess composition, is a puzzle created by the composer using chess pieces on a chessboard, which presents the solver with a particular task. For instance, a position may be given with the instruction that White is t ...

s, which he published in Germany's Russian émigré press, '' Poems and Problems'' (18 problems) and ''Speak, Memory

''Speak, Memory'' is a memoir by writer Vladimir Nabokov. The book includes individual essays published between 1936 and 1951 to create the first edition in 1951. Nabokov's revised and extended edition appeared in 1966.

Scope

The book is dedi ...

'' (one). He describes the process of composing and constructing in his memoir: "The strain on the mind is formidable; the element of time drops out of one's consciousness". To him, the "originality, invention, conciseness, harmony, complexity, and splendid insincerity" of creating a chess problem was similar to that in any other art.

List of works

;Main works written in Russian

* (1926) ''

;Main works written in Russian

* (1926) ''Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a female given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religion

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also called the Blesse ...

''

* (1928) ''King, Queen, Knave

''King, Queen, Knave'' is the second novel written by Vladimir Nabokov (under his pen name V. Sirin) while living in Berlin and sojourning at resorts in the Baltic. Written in the years 1927–8, it was published as ''Король, дама, ва ...

''

* (1930) ''The Luzhin Defense'' or ''The Defense

''The Defense'' (also known as ''The Luzhin Defense''; ) is the third novel written by Vladimir Nabokov after he had immigrated to Berlin. It was first published in Russian 1930 and later in English in 1964.

Publication

The novel appeared first ...

''

* (1930) '' The Eye''

* (1932) '' Glory''

* (1933) '' Laughter in the Dark''

* (1934) '' Despair''

* (1936) ''Invitation to a Beheading

''Invitation to a Beheading'' () is a novel by Russian American author Vladimir Nabokov. It was originally published in Russian from 1935 to 1936 as a serial in '' Sovremennye zapiski'', a Russian émigré magazine. In 1938, the work was publishe ...

''

* (1938) '' The Gift''

* (1939) ''The Enchanter

''The Enchanter'' () is a novella written by Vladimir Nabokov in Paris in 1939. It was his last work of fiction written in Russian. Nabokov never published it during his lifetime. After his death, his son Dmitri translated the novella into Eng ...

''

;Main works written in English

* (1941) '' The Real Life of Sebastian Knight''

* (1947) '' Bend Sinister''

* (1955) ''Lolita