Owenites on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Owenism is the

Owen's economic thought grew out of widespread poverty in Britain in the aftermath of the

Owen's economic thought grew out of widespread poverty in Britain in the aftermath of the

The Co-operator

" Although the paper was only published for two years between 1827 and 1829, it served to unify the movement. The next attempt to broaden the cooperative movement was the

Between 1829 and 1835, Owenite socialism was politicized through two organizations; the

Between 1829 and 1835, Owenite socialism was politicized through two organizations; the

Owenite Societies Archives

at the

Essays by Owen

at the Marxists Internet Archive {{Co-operatives , topics Eponymous political ideologies Social philosophy Utopian socialism

utopian socialist

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often d ...

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. S ...

of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted ...

and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative movement

The history of the cooperative movement concerns the origins and history of cooperatives across the world. Although cooperative arrangements, such as mutual insurance, and principles of cooperation existed long before, the cooperative movement bega ...

.Ronald George Garrett (1972), ''Co-operation and the Owenite socialist communities in Britain, 1825–45'', Manchester University Press ND, The Owenite movement undertook several experiments in the establishment of utopian communities organized according to communitarian and cooperative principles. One of the best known of these efforts, which were largely unsuccessful, was the project at New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, Posey County, Indiana. It lies north of Mount Vernon, Indiana, Mount Vernon, the county seat, and is part of th ...

, which started in 1825 and was abandoned by 1829. Owenism is also closely associated with the development of the British trade union movement, and with the spread of the Mechanics' Institute movement.

Economic thought

Owen's economic thought grew out of widespread poverty in Britain in the aftermath of the

Owen's economic thought grew out of widespread poverty in Britain in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

. His thought was rooted in seventeenth century English " moral economy" ideals of “fair exchange, just price, and the right to charity.” "Utopian socialist” economic thought such as Owen's was a reaction to the laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. A ...

impetus of Malthusian

Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. This event, c ...

Poor Law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of he ...

reform. Claeys notes that "Owen’s ‘Plan’ began as a grandiose but otherwise not exceptionally unusual workhouse scheme to place the unemployed poor in newly built rural communities." Owen’s “plan” was itself derivative of (and ultimately popularized by) a number of Irish and English trade unionists such as William Thompson and Thomas Hodgskin

Thomas Hodgskin (12 December 1787 – 21 August 1869) was an English socialist writer on political economy, critic of capitalism and defender of free trade and early trade unions. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the term ''socialist ...

, co-founder of the London Mechanics Institute. When this poverty led to revolt, as it did in Glasgow in April 1820, a “committee of gentlemen” from the area commissioned the cotton manufacturer and philanthropist, Robert Owen, to produce a “Report to the County of Lanark” in May 1820, which recommended a new form of pauper relief; the cooperative village. Owen's villages thus needed to be compared with the Dickensian " Houses of Industry" that were created after the passage of the 1834 Poor Law amendment act. Owen's report was to spark a widespread “socialist” movement that established co-operatives, labour exchanges, and experimental communities in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada. Owen was to disseminate his ideas in North America beginning in 1824. His ideas were most widely received in New York and Philadelphia, where he was greeted by nascent working men's parties.

Owen was no theoretician, and the Owenite movement drew on a broad range of thinkers such as William Thompson, John Gray, Abram Combe

Abram Combe (15 January 1785–11 August 1827) was a British utopian socialist, an associate of Robert Owen and a major figure in the early co-operative movement, leading one of the earliest Owenite communities, at Orbiston, Scotland.

Life Early ...

, Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh social reformer who immigrated to the United States in 1825, became a U.S. citizen, and was active in Indiana politics as member of the Democratic Party in the India ...

, George Mudie, John Francis Bray, Dr William King, and Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

. These men rooted their thought in Ricardian socialism

Ricardian socialism is a branch of classical economic thought based upon the work of the economist David Ricardo (1772–1823). The term is used to describe economists in the 1820s and 1830s who developed a theory of capitalist exploitation from ...

and the labour theory of value.

Utopian communities

United Kingdom

*New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and hou ...

founded originally by David Dale, passed on to a partnership that included Robert Owen, who became mill manager in 1800. In Owen's time approximately 2500 people worked at the mill, many from the poorhouses of Edinburgh and Glasgow. He improved conditions there notably, focusing in particular on children, for whom he provided the first infant school in 1817.The mills were a commercial success. When other partners were unhappy at the expense occurred by his welfare programs, Owen bought them out. New Lanark today is recognized by UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

and is one of Scotland's six world heritage sites.

* George Mudie, a printer, formed an Owenite community at Spa Fields

Spa Fields is a park and its surrounding area in the London Borough of Islington, bordering Finsbury and Clerkenwell. Historically it is known for the Spa Fields riots of 1816 and an Owenite community which existed there between 1821 and 1824. Th ...

, in the London Borough of Islington

The London Borough of Islington ( ) is a London borough in Inner London. Whilst the majority of the district is located in north London, the borough also includes a significant area to the south which forms part of central London. Islington has ...

between 1821 and 1824. Mudie published a weekly journal, the ''Economist'', which ran from 27 January 1821 to 9 March 1822. The printer Henry Hetherington was a member. Mudie moved to Orbiston after this community failed.

* Archibald James Hamilton, the radical laird of Dalzell and Orbiston, owned an estate 8 miles outside Glasgow. He was one of the gentlemen who commissioned Robert Owens’ “Report to the County of Lanark”. In 1821, he and several other Owenite sympathizers such as Abram Combe

Abram Combe (15 January 1785–11 August 1827) was a British utopian socialist, an associate of Robert Owen and a major figure in the early co-operative movement, leading one of the earliest Owenite communities, at Orbiston, Scotland.

Life Early ...

formed the Edinburgh Practical Society that operated a co-operative store, and a school. In addition, Hamilton provided his 290-acre estate, Orbiston, for the first Owenite co-operative community in the United Kingdom, in 1825. The community collapsed in 1827 on the death of its founder.

* Ralahine Community, County Clare, Ireland (1831–1833) was organized on the estate of John Vandeleur by Edward T. Craig. Unlike other Owenite communities, workers were paid “labour notes” which they could spend in the co-operative store. By this time, Owenism had moved on to its Labour Exchange phase. The experiment ended when Vandeleur lost his estate through gambling.

* Harmony Hall Community at Queenwood Farm, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

(1839–1845). This is the only other colony than New Harmony in Indiana founded by Robert Owen himself. In 1839 his Association of Classes of All Nations acquired five hundred acres at Queenwood farm.

United States

* New Harmony, Indiana (1825–27). Founded by Robert Owen himself. He purchased the community of New Harmony from the religious communists known as the Rappites. The influential Owenite newspaper, "The Free Enquirer" was published here. *Yellow Springs, Ohio

Yellow Springs is a village in Greene County, Ohio, United States. The population was 3,697 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Dayton Metropolitan Statistical Area. It is home to Antioch College.

History

The area of the village had long ...

on a site now occupied by Antioch College, Miami Township, Greene County (1825).

* Nashoba Commune, Tennessee (1825–28) was organized by Fanny Wright to educate and emancipate slaves. To ensure emancipation without financial loss to slaveholders, slaves would buy their freedom and then be transported to the independent settlements of Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean to its south and southwest. ...

and Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, an ...

.

* Franklin or Haverstraw Community, Haverstraw, Rockland County, New York (1826).

* Forestville Commonwealth, Lapham's Mills, Coxsackie, Greene County, New York (1826–1827). Also known as the "Coxsackie Community." Founded by Dr. Samuel Underhill, under the influence of Dr Cornelius Blatchly's "An Essay on Common Wealths" (1822). Saddled with debt, 27 members decided to join the Kendal community, leaving on 23 Oct. 1827.

* Kendal Community, Ohio, Massillon, Ohio (1825–9). Also known as "Friendly Association of Mutual Interests at Kendal."

* Valley Forge Community, Valley Forge, Chester County, PA (1826). Also known as "Friendly Association of Mutual Interests."

* Blue Spring Community, Van Buren Township, Monroe County, Indiana (1826)

* Promisewell Community, Munroe County, PA (1843). Also known as the Society of One-Mentians.

* Goose Pond Community, Pike County, PA (1843). An offshoot of Promisewell, built on the site of Fourierist phalanx "Social Reform Unity."

* Hunt's Colony, Spring Lake, Mukwonago Township, Waukesha County, Wisconsin (1843). Also known as the Colony of Equality. Founded by several English organizations.

Canada

* When Orbiston collapsed in 1827 on the death of its founder, most of the residents moved to Upper Canada, where they formed the short-lived Owenite community of Maxwell near Sarnia.Co-operative movement and labour exchange

Although the early emphasis in Owenism was on the formation of utopian communities, these communities were predicated upon co-operative labour, and frequently, co-operative sales. For example, the Edinburgh Practical Society created by the founders of Orbiston operated a co-operative store to raise the capital for the community.Abram Combe

Abram Combe (15 January 1785–11 August 1827) was a British utopian socialist, an associate of Robert Owen and a major figure in the early co-operative movement, leading one of the earliest Owenite communities, at Orbiston, Scotland.

Life Early ...

, the leader of that community, was to author the pamphlet ''The Sphere for Joint Stock Companies'' (1825), which made clear that Orbiston was not to be a self-subsistent commune, but a co-operative trading endeavor.

For the majority of Owenites who did not live in these utopian communities, the working-class Owenite tradition was composed of three overlapping institutions: "the cooperative store, the labour exchange and the trade union."

The cooperative ideas of Owen and Combe were further developed by the Brighton doctor, William King, publisher ofThe Co-operator

" Although the paper was only published for two years between 1827 and 1829, it served to unify the movement. The next attempt to broaden the cooperative movement was the

British Association for the Promotion of Co-operative Knowledge

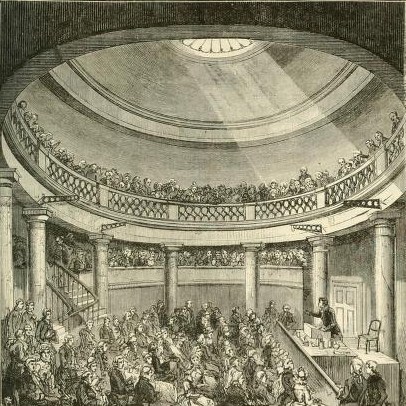

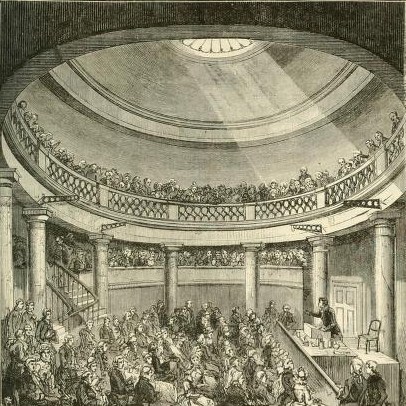

Henry Hetherington (June 1792 – 24 August 1849) was an English printer, bookseller, publisher and newspaper proprietor who campaigned for social justice, a free press, universal suffrage and religious freethought. Together with his close asso ...

(B.A.P.C.K.) founded in 1829. It was the successor to the London Cooperative Society, and served as a clearing house of information for Britain's 300 cooperatives. It provided pamphlets, lectures and "missionaries" for the movement. It held its quarterly meetings in the London Mechanics Institute, with frequent lectures from William Lovett

William Lovett (8 May 1800 – 8 August 1877) was a British activist and leader of the Chartist political movement. He was one of the leading London-based artisan radicals of his generation.

A proponent of the idea that political rights could ...

, and many other radical Owenites who would go on to lead the London Working Men's Association. B.A.P.C.K. rejected joint stock cooperative efforts as "systems of competition." Its aim was the establishment of an agricultural, manufacturing or trading community. They recognized that the success of cooperation depended upon parliamentary reform, and this proved the basis for working with the radical reformers who would go on to create the Chartist movement.

The National Equitable Labour Exchange was founded in London in 1832 and spread to several English cities, most notably Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

, before closing in 1834. Beginning from the Ricardian Socialist view that labour was the source of all value, the exchange issued "Labour Notes" similar to banknotes, denominated in hours. John Gray proposed a ''National Chamber of Commerce'' as a central bank issuing a ''labour currency''. A similar time-based currency would be created by an American Owenite, Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

, who founded the Cincinnati Time Store

The Cincinnati Time Store (1827-1830) was the first in a series of retail stores created by American individualist anarchist Josiah Warren to test his economic labor theory of value. The experimental store operated from May 18, 1827 until May 183 ...

. A short-lived Labour Exchange was also founded in 1836 in Kingston, Upper Canada.

Political and labour organization

Robert Owen was resolutely apolitical, and initially pursued a non-class based form of community organization. However, as the focus of the movement shifted from the formation of utopian communities to cooperatives, Owenites became active in labour organization in both the United Kingdom and the United States. In the United Kingdom, Owenites became further involved in electoral reform (now envisioned as part of a broaderReform Movement

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social system, social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more Radicalism (politics), radical socia ...

).

United Kingdom

Between 1829 and 1835, Owenite socialism was politicized through two organizations; the

Between 1829 and 1835, Owenite socialism was politicized through two organizations; the British Association for the Promotion of Co-operative Knowledge

Henry Hetherington (June 1792 – 24 August 1849) was an English printer, bookseller, publisher and newspaper proprietor who campaigned for social justice, a free press, universal suffrage and religious freethought. Together with his close asso ...

, and its successor, the National Union of the Working Classes (founded in 1831, and abandoned in 1835). The aim of B.A.P.C.K. was to promote cooperatives, but its members recognized that political reform was necessary if they were to achieve that end. They thus formed a "Political Union" which was the principal form of political activity in the period before the Great Reform Act of 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

. Political Unions organized petitioning campaigns meant to sway parliament. The B.A.P.C.K. leadership thus formed the National Union of the Working Classes (N.U.W.C.) to push for a combination of Owenism and radical democratic political reform.

Owen himself resisted the N.U.W.C.'s political efforts at reform, and by 1833, he was an acknowledged leader of the British trade union movement. In February 1834, he helped form Britain's first national labour organization, the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union

The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union of 1834 was an early attempt to form a national union confederation in the United Kingdom.

There had been several attempts to form national general unions in the 1820s, culminating with the National A ...

. The organisation began to break up in the summer of 1834Harrison, J.F.C. (1969) ''Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America'', Routledge, , p.212 and by November, it had ceased to function.

It was from this heady mix of working class trade unionism, co-operativism, and political radicalism in the disappointed wake of the 1832 Reform Bill and the 1834 New Poor Law, that a number of prominent Owenite leaders such as William Lovett

William Lovett (8 May 1800 – 8 August 1877) was a British activist and leader of the Chartist political movement. He was one of the leading London-based artisan radicals of his generation.

A proponent of the idea that political rights could ...

, John Cleave and Henry Hetherington helped form the London Working Men's Association in 1836. The London Working Men's Association led the Chartist movement demanding universal suffrage. Many have viewed Owenite socialism and Chartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, ...

as mutually hostile because of Owen's refusal to engage in politics. However, Chartists and Owenites were “many parts but one body” in this initial stage.

United States

Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh social reformer who immigrated to the United States in 1825, became a U.S. citizen, and was active in Indiana politics as member of the Democratic Party in the India ...

emigrated to the United States in 1825 to help his father run New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, Posey County, Indiana. It lies north of Mount Vernon, Indiana, Mount Vernon, the county seat, and is part of th ...

. After the community dissolved, Robert Dale Owen moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and became the co-editor of the ''Free Enquirer'', a socialistic and anti-Christian weekly, with Frances Wright

Frances Wright (September 6, 1795 – December 13, 1852), widely known as Fanny Wright, was a Scottish-born lecturer, writer, freethinker, feminist, utopian socialist, abolitionist, social reformer, and Epicurean philosopher, who became a ...

, the founder of the Nashoba community, from 1828 to 1832. They also founded a "Hall of Science" in New York like those being created by Owenites in the United Kingdom. From this base, Owen and Wright sought to influence the Working Men's Party

: ''For other organizations with a similar name, see Workingmen's Party (disambiguation).''

The Working Men's Party in New York was a political party founded in April 1829 in New York City. After a promising debut in the fall election of 1829, ...

.

The Working Men's Party emerged spontaneously out of strike action by journeymen in 1829 who protested having to work more than 10 hours a day. They appointed a Committee of Fifty to discuss organization, and they proposed running a ticket of journeymen in the legislative elections. At the same time, Owen and Wright were continuing their own efforts to organize New York City's working classes. The two groups uneasily merged, and were encouraged by their success in the elections. To support the movement, George Henry Evans began publishing the ''Working Man's Advocate''.

The new party quickly fell victim to factionalism over several controversial proposals. Owen's controversial contribution was a proposed "state guardianship plan" where children would be removed from their homes at the age of two and placed in government run schools, to protect them from the degeneracy of slum life and allow their optimum development through free schooling. By late 1830, the party was effectively dead.

Canada

Owenism was introduced toUpper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

(now Ontario) in 1835 by the Rev. Thaddeus Osgood, a Montreal-based evangelical minister. Osgood returned to London in 1829. Deep in debt, he was unable to return to Canada, and spent the succeeding five years preaching in London's workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

s and prisons. It was in this working class milieu that Osgood met and debated with Robert Owen. Although attracted by the “home colony” model of poverty relief, Osgood was offended by Owens’ anti-religious rhetoric. Drawing on Owenism, rather than Owen, Osgood proposed to found “Relief Unions” for the poor when he finally returned to Canada in 1835. Through Osgood's influence, Robert Owens’ ideas were widely debated in Toronto. Osgood's proposal elicited support from across Upper Canada in early 1836, and petitions for the Relief Union's incorporation were sent to the Assembly and Legislative Council. Significantly, Osgood's plan was proposed at the same time as the new Lt. Governor, Sir Francis Bond Head was arriving in Toronto. Bond Head was an Assistant Poor Law Administrator, and intent on imposing workhouses for the poor, not Owenite colonies.

Acknowledgements

Last paragraph of Chapter III in ''The Communist Manifesto'' Marx mentions that ″The Owenites in England, and the Fourierists in France, respectively, oppose the Chartists and Reformists."See also

*Cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-contro ...

* Owenstown

References

External links

Owenite Societies Archives

at the

International Institute of Social History

The International Institute of Social History (IISH/IISG) is one of the largest archives of labor and social history in the world. Located in Amsterdam, its one million volumes and 2,300 archival collections include the papers of major figu ...

Essays by Owen

at the Marxists Internet Archive {{Co-operatives , topics Eponymous political ideologies Social philosophy Utopian socialism