Owain Glyndŵr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Owain ap Gruffydd (), commonly known as Owain Glyndŵr or Glyn Dŵr (, anglicised as Owen Glendower), was a

Owain Glyndŵr was born in 1354 in the northeast Welsh Marches (near the border between Wales and England) to a family of ''Uchelwyr'' – nobles descended from the pre-conquest native Welsh royal dynasties – in traditional Welsh society. This group moved easily between Welsh and English societies and languages, occupying important offices for the

Owain Glyndŵr was born in 1354 in the northeast Welsh Marches (near the border between Wales and England) to a family of ''Uchelwyr'' – nobles descended from the pre-conquest native Welsh royal dynasties – in traditional Welsh society. This group moved easily between Welsh and English societies and languages, occupying important offices for the

Owain married Margaret Hanmer, also known by her

Owain married Margaret Hanmer, also known by her

These events led to Glyndŵr formally assuming his ancestral title of Prince of Powys on 16 September 1400 at his Glyndyfrdwy estate. With a small band of followers which included his eldest son, his brothers-in-law, and the

These events led to Glyndŵr formally assuming his ancestral title of Prince of Powys on 16 September 1400 at his Glyndyfrdwy estate. With a small band of followers which included his eldest son, his brothers-in-law, and the  In 1402, the English Parliament issued the

In 1402, the English Parliament issued the  In 1404, Glyndŵr's forces took Aberystwyth Castle and Harlech Castle, then continued to ravage the south by burning

In 1404, Glyndŵr's forces took Aberystwyth Castle and Harlech Castle, then continued to ravage the south by burning

During early 1405, the Welsh forces, who had until then won several easy victories, suffered a series of defeats. English forces landed in

During early 1405, the Welsh forces, who had until then won several easy victories, suffered a series of defeats. English forces landed in  Glyndŵr remained free, but he had lost his ancestral home and was a hunted prince. He continued the rebellion, particularly wanting to avenge his wife. In 1410 Owain led a suicide raid into rebel-controlled

Glyndŵr remained free, but he had lost his ancestral home and was a hunted prince. He continued the rebellion, particularly wanting to avenge his wife. In 1410 Owain led a suicide raid into rebel-controlled

File:Arms of Owain Glyndŵr.svg, Banner of Owain Glyndŵr.

File:Y Draig Aur Owain Glyndŵr.jpg, Gold dragon of Wales used by Glyndwr, based on his privy seal.

File:Arms of Owen Glyndwr 02949.jpg, Arms assigned Owain Glyndŵr in ''A Tour in Wales'' by

Cefn Caer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Glyndwr, Owain 14th-century births 1410s deaths 1410s missing person cases 14th-century Welsh lawyers 15th-century monarchs in Europe 15th-century Welsh military personnel * Owain Missing person cases in Wales Monarchs of Powys Welsh princes Year of birth uncertain Year of death uncertain

Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

leader, soldier and military commander who led a 15 year long Welsh War of Independence with the aim of ending English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

rule in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

during the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

. He was also an educated lawyer, he formed the first Welsh Parliament ( cy, Senedd Cymru), and was the last native-born Welshman to hold the title Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

.

Owain Glyndŵr was a direct descendant of several Welsh royal dynasties including the princes of Powys via the House of Mathrafal

The Royal House of Mathrafal began as a cadet branch of the Welsh Royal House of Dinefwr, taking their name from Mathrafal Castle, their principal seat and effective capital. They effectively replaced the House of Gwertherion, who had been ruling ...

through his father Gruffudd Fychan II

Gruffudd Fychan II was Lord of Glyndyfrdwy and Lord of Cynllaith Owain c.1330–1369. As such, he had a claim to be hereditary Prince of Powys Fadog.

Ancestry

The epithet 'Fychan' implies that his father was also called Gruffudd. However c ...

, hereditary Prince ( cy, Tywysog) of Powys Fadog. And through his mother, Elen ferch Tomas ap Llywelyn, he was also a descendant of the kings and princes of the Kingdom of Deheubarth as well as the royal House of Dinefwr, and the kings and princes of the Kingdom of Gwynedd

The Kingdom of Gwynedd (Medieval Latin: ; Middle Welsh: ) was a Welsh kingdom and a Roman Empire successor state that emerged in sub-Roman Britain in the 5th century during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.

Based in northwest Wales, ...

and their cadet branch

In history and heraldry, a cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets— realm, t ...

of the House of Aberffraw

The Royal House of Aberffraw was a cadet branch of the Kingdom of Gwynedd originating from the sons of Rhodri the Great in the 9th century. Establishing the Royal court ( cy, Llys) of the Aberffraw Commote would begin a new location from which ...

.

The rebellion began in 1400, when Owain Glyndŵr, a descendent of several Welsh royal dynasties, claimed his ancestral title of Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

, following a dispute with a neighbouring English lord. In 1404, after a series of successful castle sieges and several battlefield victories against the English, Owain gained control of the country and was officially crowned Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

in the presence of French, Spanish, Scottish and Breton envoys. He summoned a national parliament, where he announced plans to reintroduce the traditional Welsh laws of Hywel Dda, establish an independent Welsh church, and build two universities (Wrexham Glyndŵr University

, mottoeng = Confidence through Education

, logo = Wrexham Glyndŵr University Logo.svg

, image = Coat of arms of Wrexham Glyndŵr.svg

, image_size = 180px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, established = 1887, as Wrexham School of Scien ...

is named in Glyndŵr's honour). Owain also formed an alliance with King Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé) and later the Mad (french: le Fol or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychotic ...

, and in 1405 a French army landed in Wales to support the rebellion.

Under Owain Glyndŵr's leadership, an internationally recognized independent Welsh state was briefly established in 1404, it lasted for 5 years until February 1409, when the English forces had captured Owain's last remaining strongholds of Aberystwyth Castle and Harlech Castle, which effectively ended Owain's territorial rule in Wales. Glyndŵr ignored two offers of a pardon from the new King Henry V and refused to surrender, he retreated to the Welsh hills and mountains with his remaining forces, from where they continued to resist English rule utilising guerilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ...

tactics for several more years until Owain disappeared in 1415, when he was recorded to have died of natural causes by one of his supporters, Adam of Usk

Adam of Usk ( cy, Adda o Frynbuga, c. 1352–1430) was a Welsh priest, canonist, and late medieval historian and chronicler. His writings were hostile to King Richard II of England.

Patronage

Born at Usk in what is now Monmouthshire (Sir Fynwy), ...

.

The English named Glyndŵr a rebel, yet the Welsh created him a folk hero. As well as becoming a national hero, Glyndŵr has since been anointed as a legend in Welsh folklore. Despite the large bounty placed on him by the English crown, Glyndŵr was never betrayed or captured, and he acquired a mythical status along the likes of Cadwaladr, Cynon ap Clydno

Cynon ap Clydno or in some translations KynonIn her translation of ''The Mabinogion'', Guest uses the spelling Kynon, but in the notes to her translation she acknowledges the character as Cynon ap Clydno or Cynan was an Arthurian hero from Welsh m ...

and King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

as a folk hero awaiting the call to return and liberate his people, "Y Mab Darogan" (The Foretold Son). Additionally, Glyndŵr became a famous character in a play created by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, spelt in the work as " Owen Glendower"; Glyndŵr appears as a king in Shakespeare's play '' Henry IV, Part 1''.

Early life

Owain Glyndŵr was born in 1354 in the northeast Welsh Marches (near the border between Wales and England) to a family of ''Uchelwyr'' – nobles descended from the pre-conquest native Welsh royal dynasties – in traditional Welsh society. This group moved easily between Welsh and English societies and languages, occupying important offices for the

Owain Glyndŵr was born in 1354 in the northeast Welsh Marches (near the border between Wales and England) to a family of ''Uchelwyr'' – nobles descended from the pre-conquest native Welsh royal dynasties – in traditional Welsh society. This group moved easily between Welsh and English societies and languages, occupying important offices for the Marcher Lords

A Marcher lord () was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border (known as the Welsh Marches) between England and Wales.

A Marcher lord was the English equivalent of a margrave (in the Holy Roman Empire) or a marquis (in ...

while maintaining their position as Uchelwyr. His father, Gruffydd Fychan II, hereditary Tywysog of Powys Fadog and Lord of Glyndyfrdwy, died sometime before 1370, leaving Glyndŵr's mother Elen ferch Tomas ap Llywelyn of Deheubarth

Deheubarth (; lit. "Right-hand Part", thus "the South") was a regional name for the realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to Gwynedd (Latin: ''Venedotia''). It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under the House o ...

a widow and Owain a young man of 16 years at most. Through his mother, Glyndŵr was also a descendant of Llywelyn the Great

Llywelyn the Great ( cy, Llywelyn Fawr, ; full name Llywelyn mab Iorwerth; c. 117311 April 1240) was a King of Gwynedd in north Wales and eventually " Prince of the Welsh" (in 1228) and "Prince of Wales" (in 1240). By a combination of war and ...

of the Gwynedd royal House of Aberffraw

The Royal House of Aberffraw was a cadet branch of the Kingdom of Gwynedd originating from the sons of Rhodri the Great in the 9th century. Establishing the Royal court ( cy, Llys) of the Aberffraw Commote would begin a new location from which ...

.

The young Owain ap Gruffydd was possibly fostered at the home of David Hanmer

Sir David Hanmer, KS, SL (1332–1387) was a fourteenth century Anglo-Welsh Justice of the King's Bench from Hanmer, Wales,Arthur Herbert Dodd"HANMER family of Hanmer, Bettisfield, Fens and Halton, Flintshire, and Pentre-pant, Salop." ''Dictiona ...

, a rising lawyer shortly to be a justice of the King's Bench, or at the home of Richard FitzAlan, 3rd Earl of Arundel. Owain is then thought to have been sent to London to study law at the Inns of Court. He probably studied as a legal apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

in London, for a period of seven years. He was possibly in London during the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

of 1381. By 1384, he was living in Wales and married to Margaret Hanmer; their marriage took place 1383 in St Chad's Church, Holt, although they may have married at an earlier date in the late 1370s according to sources. They started a large family and Owain established himself as the squire

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Use of the term evolved over time. Initially, a squire served as a knight's apprentice. Later, a village leader or a lord of the manor might come to be known as ...

of Sycharth and Glyndyfrdwy.

Glyndŵr joined the king's military service in 1384 when he undertook garrison duty under the renowned Welshman Sir Gregory Sais, or Sir Degory Sais, on the English–Scottish border at Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census re ...

. His surname Sais, meaning "Englishman" in Welsh refers to his ability to speak English, not common in Wales at the time. In August 1385, he served King Richard II under the command of John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

, again in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. In 1386, he was called to give evidence at the High Court of Chivalry, the ''Scrope v Grosvenor

''Scrope v Grosvenor'' (1389) was an early intellectual property lawsuit, specifically regarding the law of arms. One of the earliest heraldic cases brought in England, the case resulted from two different knights in King Richard II's servic ...

'' trial at Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

on 3 September that year. In March 1387, Owain fought as a squire

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Use of the term evolved over time. Initially, a squire served as a knight's apprentice. Later, a village leader or a lord of the manor might come to be known as ...

to Richard FitzAlan, 4th Earl of Arundel

Richard Fitzalan, 4th Earl of Arundel, 9th Earl of Surrey, KG (1346 – 21 September 1397) was an English medieval nobleman and military commander.

Lineage

Born in 1346, he was the son of Richard Fitzalan, 3rd Earl of Arundel and Eleanor of ...

, in the English Channel at the defeat of a Franco-Spanish-Flemish fleet off the coast of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. Upon the death in late 1387 of his father-in-law, Sir David Hanmer, knighted earlier that same year by Richard II, Glyndŵr returned to Wales as executor of his estate. Glyndŵr served as a squire to Henry Bolingbroke (later Henry IV of England

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of F ...

), son of John of Gaunt, at the short, sharp Battle of Radcot Bridge in December 1387. From the year 1384 until 1388 he had been active in military service and had gained three full years of military experience in different theatres and had seen first-hand some key events and noteworthy people.

King Richard was distracted by a growing conflict with the Lords Appellant from this time on. Glyndŵr's opportunities were further limited by the death of Sais in 1390 and the sidelining of FitzAlan, and he probably returned to his stable Welsh estates, living there quietly for ten years during his forties. The bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise ...

Iolo Goch ("Red Iolo"), himself a Welsh lord, visited Glyndŵr in Sycharth in the 1390s and wrote a number of odes to Owain, praising Owain's liberality, and writing of Sycharth, "Rare was it there / to see a latch or a lock."

Siblings

The names and numbers of Owain Glyndŵr's siblings cannot be certainly known. The following are given byJacob Youde William Lloyd

Jacob Youde William Lloyd (1816–1887) was an English Anglican cleric, Catholic convert, antiquarian and genealogist. To 1857 his name was Jacob Youde William Hinde.

Life

He was the eldest son of Jacob William Hinde, of Ulverstone, Lancashire, a ...

:

* Brother Tudur, Lord of Gwyddelwern, born about 1362, died 11 March 1405 at a battle in Brecknockshire in the wars of his brother.

* Brother Gruffudd had a daughter and heiress, Eva.

* Sister Lowri, also spelt Lowry, married Robert Puleston of Emral.

* Sister Isabel married Adda ap Iorwerth Ddu of Llys Pengwern.

* Sister Morfudd married Sir Richard Croft of Croft Castle

Croft Castle is a country house in the village of Croft, Herefordshire, England. Owned by the Croft family since 1085, the castle and estate passed out of their hands in the 18th century, before being repurchased by the family in 1923. In 1957 ...

, in Herefordshire and, secondly, David ab Ednyfed Gam of Llys Pengwern.

* Sister Gwenllian.

Tudur, Isabel and Lowri are given as his siblings by the more cautious R. R. Davies. That Owain Glyndŵr had another brother Gruffudd is likely; that he possibly had a third, Maredudd, is suggested by one reference.

Marriage and issue

Owain married Margaret Hanmer, also known by her

Owain married Margaret Hanmer, also known by her Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

name Marred ferch Dafydd, daughter of Sir David Hanmer

Sir David Hanmer, KS, SL (1332–1387) was a fourteenth century Anglo-Welsh Justice of the King's Bench from Hanmer, Wales,Arthur Herbert Dodd"HANMER family of Hanmer, Bettisfield, Fens and Halton, Flintshire, and Pentre-pant, Salop." ''Dictiona ...

of Hanmer, early in his life.

Iolo Goch wrote of Margaret Hanmer :

Owain's daughter Alys had secretly married Sir John Scudamore, the King's appointed Sheriff of Herefordshire. Somehow he had weathered the rebellion and remained in office. It was rumoured that Owain finally retreated to their home at Kentchurch.

A grandchild of the Scudamore's was Sir John Donne of Kidwelly

Kidwelly ( cy, Cydweli) is a town and community in Carmarthenshire, southwest Wales, approximately northwest of the most populous town in the county, Llanelli. In the 2001 census the community of Kidwelly returned a population of 3,289, ...

, a successful Yorkist courtier, diplomat and soldier, who after 1485 made an accommodation with his fellow Welshman, Henry VII. Through the Donne family, many prominent English families are descended from Owain, including the House of de Vere, successive holders of the title Earl of Oxford, and the Cavendish family ( Dukes of Devonshire).

Noted children of Glyndŵr :

*Gruffudd Gruffudd or Gruffydd ( or , in either case) is a Welsh name, originating in Old Welsh as a given name and today used as both a given and surname. It is the origin of the Anglicised name '' Griffith[s]'', and was historically sometimes treat ...

, born about 1375, was captured by the English, confined in Nottingham Castle, and taken to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

in 1410. He died in prison of bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

about 1412.

*Madog

* Maredudd, whose date of birth is unknown, was still living in 1421 when he accepted a pardon.

*Thomas

*John

* Alys married Sir John Scudamore. She was the lady of Glyndyfrdwy and Cynllaith, and heiress of the Principalities of Powys, South Wales, and Gwynedd.

* Janet, who married Sir John de Croft of Croft Castle

Croft Castle is a country house in the village of Croft, Herefordshire, England. Owned by the Croft family since 1085, the castle and estate passed out of their hands in the 18th century, before being repurchased by the family in 1923. In 1957 ...

, in Herefordshire.

* Margaret, who married Sir Richard Monnington of Monnington, in Herefordshire.

Owain's sons were either taken prisoner or died in battle and had no issue. Owain had additional illegitimate children: David, Gwenllian, Ieuan, and Myfanwy.

Welsh Revolt

In the late 1390s, a series of events began to push Owain towards rebellion, in what was later to be called the Welsh Revolt, the Glyndŵr Rising or (within Wales) the Last War of Independence. His neighbour,Baron Grey de Ruthyn

Baron Grey of Ruthin (or Ruthyn) was a noble title created in the Peerage of England by writ of summons in 1324 for Sir Roger de Grey, a son of John, 2nd Baron Grey of Wilton, and has been in abeyance since 1963. Historically, this branch of the ...

, had seized control of some land, for which Glyndŵr appealed to the English Parliament. Owain's petition for redress was ignored. Later, in 1400, Lord Grey informed Glyndŵr too late of a royal command to levy feudal troops for Scottish border service, thus enabling him to call the Welshman a traitor in London court circles. Lord Grey had stature in the Royal court of King Henry IV. The English Courts refused to hear, or the case was delayed because Lord Grey prevented Owain's letter from reaching the King.

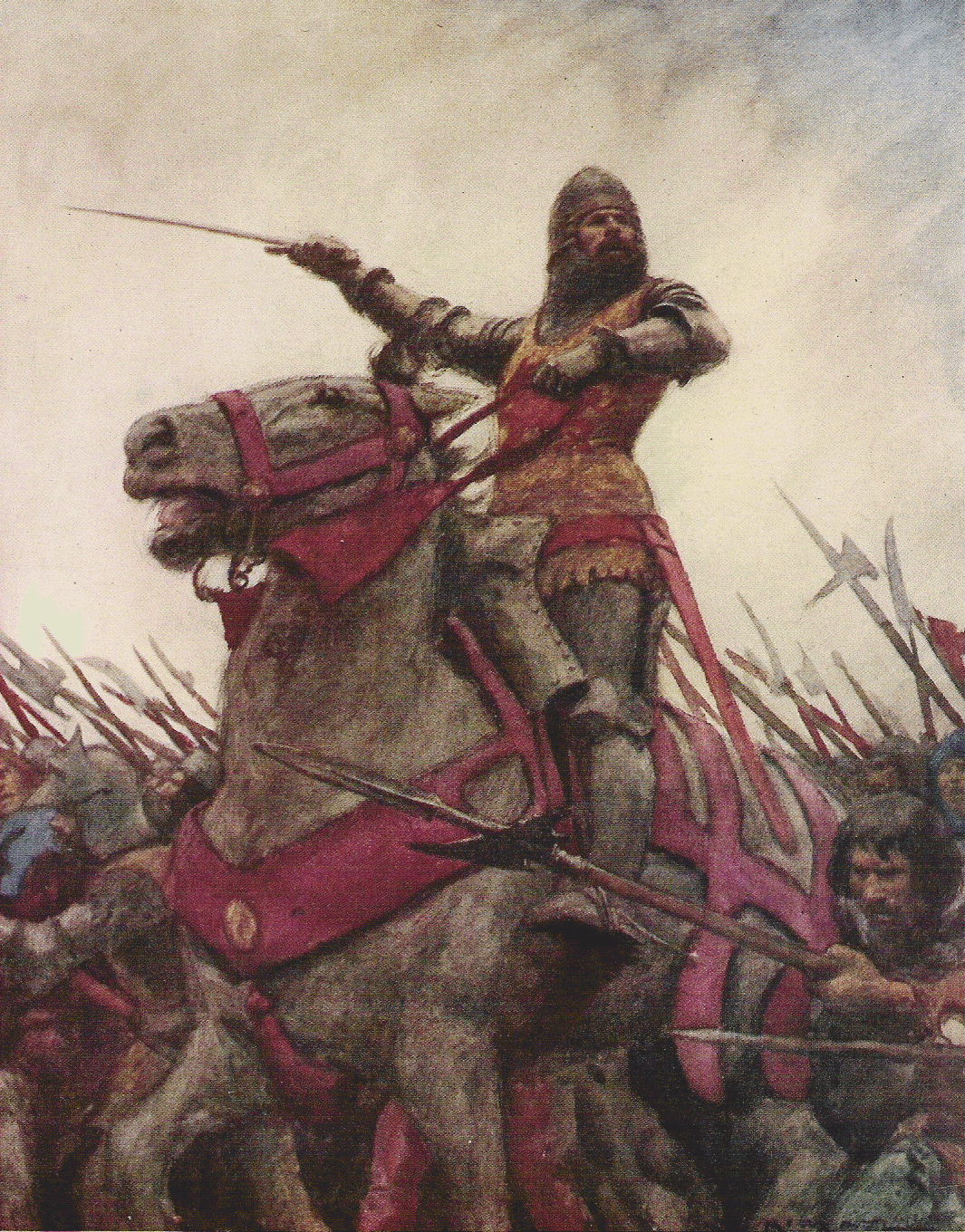

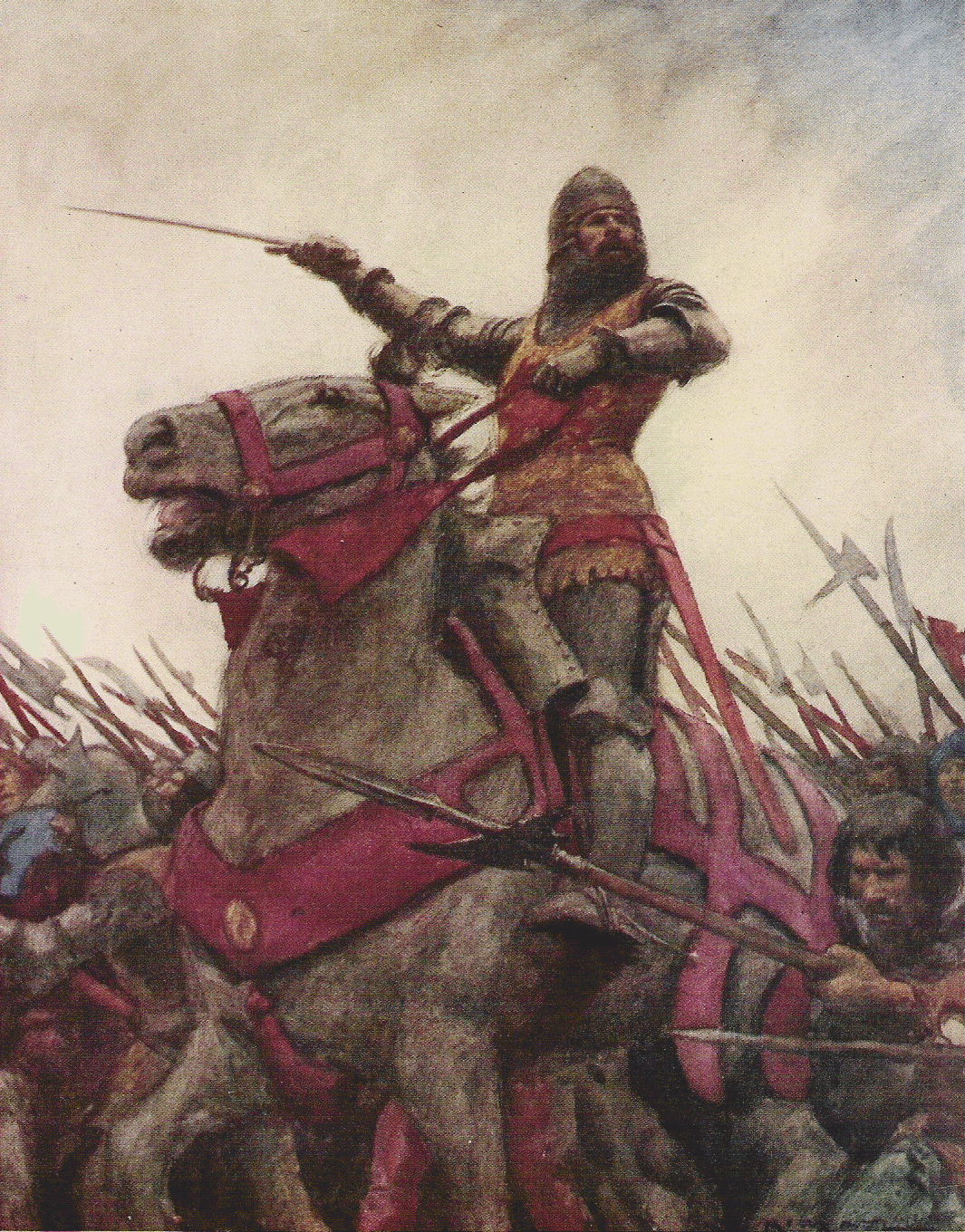

On 16 September 1400, Owain Glyndŵr instigated a 15-year Welsh Revolt against the rule of King Henry IV of England

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of ...

. With the use of guerilla tactics, the Welsh troops managed to inflict a series of defeats on the English forces and captured key castles across Wales, rapidly gaining control of most of the country. News of the rebellion's success spread internationally across Europe and Glyndwr began receiving naval support from Scotland and Brittany, He also received the support of King Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé) and later the Mad (french: le Fol or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychotic ...

who agreed to send French troops and supplies to aid the rebellion. In 1403 a Welsh army including a French contingent assimilated into forces mainly from Morgannwg and the Rhondda Valleys region commanded by Owain Glyndŵr, his senior general Rhys Gethin

Rhys Gethin (died in 1405) was a key figure in the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr. He was his standard bearer and a leading general. His name means "swarthy Rhys".

Little is known of his life. He had a brother, Hywel Coetmor, who also played a sign ...

and Cadwgan, Lord of Glyn Rhondda, defeated a large English invasion force reputedly led by King Henry IV himself at the Battle of Stalling Down in Glamorgan, South Wales. Medieval historian Iolo Morganwg wrote that while raiding English held territories in Wales, Glyndŵr and his rebels took from the powerful and rich and distributed the loot among the poor, hence why Glyndŵr is often also viewed as a Robin Hood figure.

Sources state that Glyndŵr was under threat because he had written an angry letter to Lord Grey, boasting that lands had come into his possession, and he had stolen some of Lord Grey's horses, and believing Lord Grey had threatened to "burn and slay" within his lands, he threatened retaliation in the same manner. Lord Grey then denied making the initial threat to burn and slay and replied that he would take the incriminating letter to Henry IV's council and that Glyndŵr would hang for the admission of theft and treason contained within the letter. The deposed king, Richard II, had support in Wales, and in January 1400 serious civil disorder broke out in the English border city of Chester after the public execution of an officer of Richard II. These events led to Glyndŵr formally assuming his ancestral title of Prince of Powys on 16 September 1400 at his Glyndyfrdwy estate. With a small band of followers which included his eldest son, his brothers-in-law, and the

These events led to Glyndŵr formally assuming his ancestral title of Prince of Powys on 16 September 1400 at his Glyndyfrdwy estate. With a small band of followers which included his eldest son, his brothers-in-law, and the Bishop of St Asaph

The Bishop of St Asaph heads the Church in Wales diocese of St Asaph.

The diocese covers the counties of Conwy and Flintshire, Wrexham county borough, the eastern part of Merioneth in Gwynedd and part of northern Powys. The Episcopal seat is loca ...

in the town of Corwen, possibly in the church of SS Mael & Sulien, he launched an assault on Lord Grey's territories. After a number of initial confrontations between King Henry IV and Owain's followers in September and October 1400, the revolt, a prequel to the War of the Roses ( Lancastrian and Tudor dispute) began to spread. Much of northern and central Wales went over to Glyndŵr. Henry IV appointed Henry Percy – the famous "Hotspur" – to bring the country to order. The King and English parliament on 10 March 1401 issued an amnesty which applied to all rebels with the exception of Owain and his cousins, Rhys ap Tudur and Gwilym ap Tudur, sons of Tudur ap Gronw (forefather of King Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beauf ...

). Both the Tudors were pardoned after their capture of Edward I's great castle at Conwy on 28 May 1401. In June, Glyndŵr scored his first major victory in the field at Mynydd Hyddgen on Pumlumon

Pumlumon (historically anglicised in various ways including ''Plynlimon,'' Plinlimon and Plinlimmon) is the highest point of the Cambrian Mountains in Wales (taking a restricted definition of the Cambrian Mountains, excluding Snowdonia, ...

. Retaliation by Henry IV on the Strata Florida Abbey followed by October. The rebel uprising had occupied all of North Wales

North Wales ( cy, Gogledd Cymru) is a regions of Wales, region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders Mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, ...

, labourers seized whatever weapons they could, farmers sold their cattle to buy arms, secret meetings were held everywhere, and bards "wandered about as messengers of sedition", castles fell into Glyndŵr's hands as he assumed the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

title. Henry IV of England

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of F ...

heard of a Welsh uprising at Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

, Henry's army wandered North Wales to Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

, and drove out Franciscan friars who favoured Richard II, all the while Glyndŵr who was in hiding had his estate forfeited to John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset. Glyndŵr had been offered a pardon on 10 March 1401 but rejected the plea. On 30 May Hotspur, having won a battle near 'Cadair Idris', left his command for the English army and began dealings with Glyndŵr. During this time in the spring of 1401, Glyndŵr appears in South Wales, and by Autumn the counties Gwynedd, Ceredigion (which temporarily submitted to England for a pardon) and Powys adhered to the rising against the English rule. Glyndŵr's attempts at stoking rebellion with help from the Scottish and Irish were quashed with the English showing no mercy and hanging some messengers. In 1402, the English Parliament issued the

In 1402, the English Parliament issued the Penal Laws against Wales

The Penal Laws against the Welsh ( cy, Deddfau Penyd) were a set of laws, passed by the Parliament of England in 1401 and 1402 that discriminated against the Welsh people as a response to the Welsh Revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, which began in 14 ...

, designed to establish English dominance in Wales, but actually pushed many Welshmen into the rebellion. In the same year, Glyndŵr captured his archenemy, Baron Grey de Ruthyn. He held him for almost a year until he received a substantial ransom from Henry. In June 1402, Glyndŵr defeated an English force led by Sir Edmund Mortimer near Pilleth (Battle of Bryn Glas

The Battle of Bryn Glas (also known as the Battle of Pilleth) was a battle between the Welsh and English on 22 June 1402, near the towns of Knighton and Presteigne in Powys, Wales. It was part of the Glyndŵr Rising of 1400-1415. It was an impor ...

), where Mortimer was captured. Glyndŵr offered to release Mortimer for a large ransom but, in sharp contrast to his attitude to de Grey, Henry IV refused to pay. Mortimer's nephew could be said to have had a greater claim to the English throne than Henry himself, so his speedy release was not an option. In response, Mortimer negotiated an alliance with Glyndŵr and married one of Glyndŵr's daughters. It is also in 1402 that mention of the French and Bretons

The Bretons (; br, Bretoned or ''Vretoned,'' ) are a Celtic ethnic group native to Brittany. They trace much of their heritage to groups of Brittonic speakers who emigrated from southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwall and Devon, ...

helping Owain was first heard. The French were certainly hoping to use Wales as they had used Scotland: as a base from which to fight the English.

Glyndŵr facing years on the run finally lost his estate in the spring of 1403, when Prince Henry as usual marched into Wales unopposed and burnt down his houses at Sycharth and Glyndyfrdwy, as well as the commote

A commote ( Welsh ''cwmwd'', sometimes spelt in older documents as ''cymwd'', plural ''cymydau'', less frequently ''cymydoedd'')''Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru'' (University of Wales Dictionary), p. 643 was a secular division of land in Medieval Wale ...

of Edeirnion and parts of Powys. Glyndŵr continued to besiege towns and burn down castles, for 10 days in July that year he toured the south and south-west Wales until all of the south joined arms in rebelling against English rule, these actions induced an internal rebellion against the King of England with the Percy's joining the rising. It is around this stage of Glyndŵr's life that Hywel Sele

Hywel Sele (died c. 1402) was a Welsh nobleman. A cousin of Owain Glyndŵr, Prince of Wales, he was a friend of Henry IV of England and opposed his cousin's 1400–1415 uprising. Sele was captured by Glyndŵr but is said to have accepted an invit ...

a cousin of the Welsh prince, attempted to assassinate Glyndŵr at the Nannau estate.

In 1403 the revolt became truly national in Wales. Royal officials reported that Welsh students at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

were leaving their studies to join Glyndŵr's. And also that Welsh labourers and craftsmen were abandoning their employers in England and returning to Wales. Owain could also draw on Welsh troops seasoned by the English campaigns in France and Scotland. Hundreds of Welsh archers and experienced men-at-arms left the English service to join the rebellion.

In 1404, Glyndŵr's forces took Aberystwyth Castle and Harlech Castle, then continued to ravage the south by burning

In 1404, Glyndŵr's forces took Aberystwyth Castle and Harlech Castle, then continued to ravage the south by burning Cardiff Castle

Cardiff Castle ( cy, Castell Caerdydd) is a medieval castle and Victorian Gothic revival mansion located in the city centre of Cardiff, Wales. The original motte and bailey castle was built in the late 11th century by Norman invaders on top ...

. Then a court was held at Harlech and Gruffydd Young was appointed as the Welsh Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

. There had been communication to Louis I, Duke of Orléans in Paris to try (unsuccessfully) to open the Welsh ports to French trade.

Senedd: Crowning as prince of Wales

By 1404 no less than four royal military expeditions into Wales had been repelled and Owain solidified his control of the nation. In 1404, he was officially crowned Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru) and held a Senedd (parliament) at Machynlleth where he outlined his national programme for an independent Wales, which included plans such as building two national universities (one in the south and one in the north), re-introducing the traditional Welsh laws of Hywel Dda, and establishing an independent Welsh church. There were envoys from other countries including France, Scotland and the Kingdom of León (in Spain). In the summer of 1405, four representatives from everycommote

A commote ( Welsh ''cwmwd'', sometimes spelt in older documents as ''cymwd'', plural ''cymydau'', less frequently ''cymydoedd'')''Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru'' (University of Wales Dictionary), p. 643 was a secular division of land in Medieval Wale ...

in Wales were sent to Harlech. Machynlleth may have been chosen due to its central location in Wales and the recently acquired possession of three nearby castles: Castell-y-Bere, Aberystwyth Castle and Harlech Castle. The current Parliament House () in Machynlleth is associated with the 1404 Senedd but the present building is more recent. Local tradition is that the stones used came from the original 1404 building.

Tripartite indenture and the year of the French

In February 1405, Glyndŵr negotiated the "Tripartite Indenture

The Tripartite Indenture was an agreement made in February 1405 among Owain Glyndŵr, Edmund Mortimer, and Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, agreeing to divide England and Wales up among them at the expense of Henry IV. Glyndŵr was to b ...

" with Edmund Mortimer and Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland. The Indenture agreed to divide England and Wales among the three of them. Wales would extend as far as the rivers Severn and Mersey, including most of Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

, Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

and Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouths ...

. The Mortimer Lords of March would take all of southern and western England and the Percys would take the north of England.

Although negotiations with the lords of Ireland were unsuccessful, Glyndŵr had reason to hope that the French and Bretons

The Bretons (; br, Bretoned or ''Vretoned,'' ) are a Celtic ethnic group native to Brittany. They trace much of their heritage to groups of Brittonic speakers who emigrated from southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwall and Devon, ...

might be more welcoming. He dispatched Gruffydd Yonge and his brother-in-law ( Margaret's brother), John Hanmer, to negotiate with the French. The result was a formal treaty that promised French aid to Glyndŵr and the Welsh. The immediate effect seems to have been that joint Welsh and Franco-Breton forces attacked and laid siege to Kidwelly Castle. The Welsh could also count on semi-official fraternal aid from their fellow Celts in the then independent Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

and Scotland. Scots and French privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s were operating around Wales throughout Owain's war. Scottish ships had raided English settlements on the Llŷn Peninsula in 1400 and 1401. In 1403, a Breton squadron defeated the English in the Channel and devastated Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the ...

, Guernsey and Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

, while the French made a landing on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

. By 1404, they were raiding the coast of England, with Welsh troops on board, setting fire to Dartmouth and devastating the coast of Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

.

1405 was the "Year of the French" in Wales. A formal treaty between Wales and France was negotiated. On the continent, the French pressed the English as the French army invaded English Plantagenet Aquitaine. Simultaneously, the French landed in force at Milford Haven in west Wales

West Wales ( cy, Gorllewin Cymru) is not clearly defined as a particular region of Wales. Some definitions of West Wales include only Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire, which historically comprised the Welsh principality of '' Dehe ...

, and attempted to capture Pembroke Castle before they were bought off. The combined forces of French and Welsh marched through Herefordshire and on into Worcestershire to Woodbury Hill

Woodbury Hill is a hill near the village of Great Witley, about south-west of Stourport-on-Severn in Worcestershire, England. It is the site of an Iron Age hillfort.

Description

The hill overlooks the River Teme to the south-west. The fort (a ...

. They met the English army just ten miles from Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

. The armies took up battle positions daily and viewed each other from a mile without any major action for eight days. Then, for reasons that have never become clear, the Welsh retreated, and so did the French shortly afterwards.

The Pennal Letter: the vision of an independent Wales

By 1405, most French forces had withdrawn after politics inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

shifted toward peace with the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantagen ...

continuing between England and France. On 31 March 1406 Glyndŵr wrote a letter to be sent to Charles VI King of France during a synod at the Welsh Church at Pennal, hence its name. Glyndŵr's letter requested maintained military support from the French to fend off the English in Wales. Glyndŵr suggested that in return, he would recognise Benedict XIII of Avignon as the Pope. The letter sets out the ambitions of Glyndŵr of an independent Wales with its own parliament, led by himself as Prince of Wales. These ambitions also included the return of the traditional law of Hywel Dda, rather than the enforced English law, establishment of an independent Welsh church as well as two universities, one in south Wales, and one in north Wales. Following this letter, senior churchmen and important members of society flocked to Glyndŵr's banner and English resistance was reduced to a few isolated castles, walled towns, and fortified manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals with ...

s.

Glyndŵr's Great Seal and a letter handwritten by him to the French in 1406 are in the Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Bibliothèque nationale de France (, 'National Library of France'; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites known respectively as ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national repository ...

in Paris. This letter is currently held in the Archives Nationales in Paris. Facsimile copies involving specialist ageing techniques and moulds of the famous Glyndwr seal were created by The National Library of Wales and were presented by the then heritage minister Alun Ffred Jones, to six Welsh institutions in 2009. The royal great seal from 1404 was given to Charles IV of France and contains images and Glyndŵr's title – la, Owynus Dei Gratia Princeps Walliae – 'Owain, by the grace of God, Prince of Wales'.

The rebellion falters

During early 1405, the Welsh forces, who had until then won several easy victories, suffered a series of defeats. English forces landed in

During early 1405, the Welsh forces, who had until then won several easy victories, suffered a series of defeats. English forces landed in Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

from Ireland and would over time push the Welsh back until the resistance in Anglesey formally ended toward the end of 1406.

Following the intervention of French forces, battling ensued for years, and in 1406 Prince Henry restored fines and redemption for Welsh soldiers to choose their own fate, prisoners were taken after the battle, and castles were restored to their original owners, this same year a son of Glyndŵr died in battle. By 1408 Glyndŵr had taken refuge in the North of Wales, having lost his ally from Northumberland.

Despite the initial success of the revolution, in 1407 the superior numbers, resources, and wealth that England had at its disposal eventually began to turn the tide of the war, and the much larger and better equipped English forces gradually began to overwhelm the Welsh. In times of war, the English changed their strategy. Rather than focusing on punitive expeditions as favoured by his father, the young Prince Henry adopted a strategy of economic blockade. Using the castles that remained in English control, he gradually began to retake Wales while cutting off trade and the supply of weapons. By 1407 this strategy was beginning to bear fruit, even though by this time Owain's rebel soldiers had achieved victories over the King's men as far as Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, where the English were in retreat. and by 1409 they had reconquered most of Wales. Later, then on 21 December 1411 the King of England issued pardons to all Welsh except their leader and Thomas of Trumpington (until 9 April 1413 from which Glyndŵr was no longer excepted). Edmund Mortimer died in the final battle, and Owain's wife Margaret along with two of his daughters (including Catrin) and three of Mortimer's granddaughters were imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

. They were all to die in the Tower in 1413 and were buried at St Swithin, London Stone

St Swithin, London Stone, was an Anglican Church in the City of London. It stood on the north side of Cannon Street, between Salters' Hall Court and St Swithin's Lane, which runs north from Cannon Street to King William Street and takes its name f ...

.

Glyndŵr fought on until he was cornered and under siege at Harlech Castle; but he managed to escape capture by disguising himself as an elderly man, sneaking out of the castle and slipping past the English military blockade in the darkness of the night. Glyndŵr retreated to the Welsh wilderness with a band of loyal supporters; he refused to surrender and continued the war with guerrilla tactics such as launching sporadic raids and ambushes throughout Wales and the English borderlands. In 1409, it was the turn of Harlech Castle to surrender.

Glyndŵr remained free, but he had lost his ancestral home and was a hunted prince. He continued the rebellion, particularly wanting to avenge his wife. In 1410 Owain led a suicide raid into rebel-controlled

Glyndŵr remained free, but he had lost his ancestral home and was a hunted prince. He continued the rebellion, particularly wanting to avenge his wife. In 1410 Owain led a suicide raid into rebel-controlled Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

, and in 1412 he carried out one of the final successful raiding parties with his most faithful soldiers and cut through the King's men; in an ambush in Brecon

Brecon (; cy, Aberhonddu; ), archaically known as Brecknock, is a market town in Powys, mid Wales. In 1841, it had a population of 5,701. The population in 2001 was 7,901, increasing to 8,250 at the 2011 census. Historically it was the c ...

, he captured, and later ransomed, a leading Welsh supporter of King Henry's, Dafydd Gam ( en, "Crooked David"). This was the last time that Owain was seen alive by his enemies, although it was claimed he took refuge with the Scudamore family. The last documented sighting of him was in 1412 when he ambushed the king's men in Brecon and captured and ransomed a leading supporter of King Henry's. In the autumn, Glyndŵr's Aberystwyth Castle surrendered while he was away fighting. But by then things were changing. Henry IV died in 1413 and his son King Henry V began to adopt a more conciliatory attitude to the Welsh. Royal pardons were offered to the major leaders of the revolt and other opponents of his father's regime. As late as 1414, there were rumours that the Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouths ...

-based Lollard

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catho ...

leader Sir John Oldcastle

Sir John Oldcastle (died 14 December 1417) was an English Lollard leader. Being a friend of Henry V, he long escaped prosecution for heresy. When convicted, he escaped from the Tower of London and then led a rebellion against the King. Eventual ...

was communicating with Owain, and reinforcements were sent to the major castles in the north and south.

Glyndŵr twice ignored offers of a pardon from the new king Henry V of England

Henry V (16 September 1386 – 31 August 1422), also called Henry of Monmouth, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1413 until his death in 1422. Despite his relatively short reign, Henry's outstanding military successes in the ...

, and despite the large rewards offered for his capture, Glyndŵr was never betrayed by the Welsh. His death was recorded by a former follower in the year 1415, at the age of approximately 56.

Disappearance

Nothing certain is known of Glyndŵr after 1412. Despite enormous rewards being offered, he was neither captured nor betrayed. He ignored royal pardons. Tradition has it that he died and was buried possibly in the church of Saints Mael and Sulien at Corwen close to his home, or possibly on his estate in Sycharth or on the estates of his daughters' husband:Kentchurch

Kentchurch is a small village and civil parish in Herefordshire, England. It is located some south-west of Hereford and north-east of Abergavenny, beside the River Monnow and adjoining the boundary between England and Wales. The village name ...

in south Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouths ...

or Monnington in west Herefordshire.

In his book ''The Mystery of Jack of Kent and the Fate of Owain Glyndŵr'', Alex Gibbon argues that the folk hero Jack of Kent, also known as Siôn Cent – the family chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intelligence ...

of the Scudamore family – was, in fact, Owain Glyndŵr himself. Gibbon points out a number of similarities between Siôn Cent and Glyndŵr (including physical appearance, age, education, and character) and claims that Owain spent his last years living with his daughter Alys, passing himself off as an ageing Franciscan friar

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

and family tutor. There are many folk tales of Glyndŵr donning disguises to gain an advantage over opponents during the rebellion.

Death

Adam of Usk

Adam of Usk ( cy, Adda o Frynbuga, c. 1352–1430) was a Welsh priest, canonist, and late medieval historian and chronicler. His writings were hostile to King Richard II of England.

Patronage

Born at Usk in what is now Monmouthshire (Sir Fynwy), ...

, a one-time supporter of Glyndŵr, made the following entry in his Chronicle in the year 1415: "After four years in hiding, from the king and the realm, Owain Glyndŵr died, and was buried by his followers in the darkness of night. His grave was discovered by his enemies, however, so he had to be re-buried, though it is impossible to discover where he was laid."

Thomas Pennant writes that Glyndwr died on 20 September 1415 at the age of 61 (which would place his birth at approximately 1354).

In 1875, the Rev. Francis Kilvert wrote in his diary that he saw the grave of "Owen Glendower" in the churchyard at Monnington " rd by the church porch and on the western side of it ... It is a flat stone of whitish-grey shaped like a rude obelisk figure, sunk deep into the ground in the middle of an oblong patch of earth from which the turf has been pared away, and, alas, smashed into several fragments."

In 2006, Adrien Jones, the president of the Owain Glyndŵr Society, said, "Four years ago we visited a direct descendant of Glyndŵr, a John Skidmore, at Kentchurch Court

Kentchurch Court is a Grade I listed stately home east from the village of Kentchurch in Herefordshire, England.

History

It is the family home of the Scudamore family. Family members included Sir John Scudamore, who acted as constable and ...

, near Abergavenny

Abergavenny (; cy, Y Fenni , archaically ''Abergafenni'' meaning "mouth of the River Gavenny") is a market town and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. Abergavenny is promoted as a ''Gateway to Wales''; it is approximately from the border wit ...

. He took us to Mornington Straddle, in Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouths ...

, where one of Glyndŵr's daughters, Alice, lived. Mr Skidmore told us that he (Glyndŵr) spent his last days there and eventually died there... It was a family secret for 600 years and even Mr Skidmore's mother, who died shortly before we visited, refused to reveal the secret. There's even a mound where he is believed to be buried at Mornington Straddle." Historian Gruffydd Aled Williams

Gruffydd Aled Williams FLSW (born 1943) is a scholar who specialises in Welsh medieval poetry and Renaissance literature. He was brought up in Dinmael, Denbighshire, and Glyndyfrdwy in the former county of Merioneth (now in Denbighshire). Educat ...

suggests in a 2017 monograph that the burial site is in the Kimbolton Chapel near Leominster, the present parish church of St James the Great which used to be the chapelry of Leominster Priory, based upon a number of manuscripts held in the National Archives. Although Kimbolton is an unexceptional and relatively unknown place outside of Herefordshire, it is closely connected to the Scudamore family. Given the existence of other links with Herefordshire, its place within the mystery of Owain Glyndŵr's last days cannot be discounted. , his final resting place remains uncertain.

There is a statue in Corwen, North Wales.

Legacy

Statues and memorial

During theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

unveiled a statue to Glyndŵr in Cardiff City Hall

City Hall ( cy, Neuadd y ddinas) is a civic building in Cathays Park, Cardiff, Wales, UK. It serves as Cardiff's centre of local government. It was built as part of the Cathays Park civic centre development and opened in October 1906. Built ...

.

A statue of Glyndŵr by the sculptor Simon van de Put was installed in The Square in Corwen in 1995, and in 2007 it was replaced with a larger equestrian statue by Colin Spofforth.

A monument was erected in Machynlleth in 2000, on the 600th anniversary of the beginning of the Glyndwr Rising. The plinth of the monument has an by the poet Dafydd Wyn Jones, which he has translated as:

Warfare

Glyndwr's guerilla was described byFidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

as the first effective guerilla leader of the last two millennia. It has even been suggested that Castro copied some of Glyndwr's methods in the Cuban Revolution. Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

is said to have been inspired by Glyndwr and Castro is also said to have kept books about Glyndwr.

Music and television

The song "Owain Glyndyr's War Song" was composed, sometime before 1870, by Elizabeth Grant with words by Felicia Hemans. Glyndŵr appears in James Hill's 1983 UK TV movie ''Owain Glendower, Prince of Wales''. In 2007 popular Welsh musicians theManic Street Preachers

Manic Street Preachers, also known simply as the Manics, are a Welsh Rock music, rock band formed in Blackwood, Caerphilly, Blackwood in 1986. The band consists of cousins James Dean Bradfield (lead vocals, lead guitar) and Sean Moore (musician ...

wrote a song entitled "1404" based on Owain Glyndŵr. The song can be found on the CD single for 'Autumnsong

"Autumnsong" is a song by Manic Street Preachers and was the third single taken from the album ''Send Away the Tigers''. It was released on 23 July 2007. It peaked and debuted at number #10 in the UK Singles Chart.

Background

As with all ''Send ...

'.

The BBC's '' Horrible Histories'', S5 E7 (2013), features a song about Glyndŵr, which is a parody of the Tom Jones

Tom Jones may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*Tom Jones (singer) (born 1940), Welsh singer

*Tom Jones (writer) (1928–2023), American librettist and lyricist

*''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'', a novel by Henry Fielding published in 1 ...

1967 hit song "Delilah".

Politics

In the late 19th century, the Cymru Fydd ( en, Young Wales) movement recreated Glyndŵr as the father of Welsh nationalism. The creation of theNational Assembly for Wales

The Senedd (; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, it makes laws for Wales, agrees certain taxes and scrutinises the Welsh Go ...

brought him back into the spotlight and in 2000 celebrations were held all over Wales to commemorate the 600th anniversary of Glyndŵr's revolt, including a historic reenactment at the Millennium National Eisteddfod of Wales, Llanelli 2000.

Crime

Previously, George Owen, in his book ''A Dialogue of the present Government of Wales'', written in 1594, commented on the topic of the "''Cruell lawes against Welshmen made by Henrie the ffourth''" in his attempts to quell the revolt. But it was not until the late 19th century that Glyndŵr's reputation was revived. Glyndŵr is now remembered as a national hero and numerous small groups have adopted his symbolism to advocate independence or nationalism for Wales. For example, during the 1980s, a group calling themselves " Meibion Glyndŵr" claimed responsibility for the burning of English holiday homes in Wales.Education

An annual award for achievement in the arts and literature, theGlyndŵr Award

The Glyndŵr Award ( Welsh: Gwobr Glyndŵr) is made for an outstanding contribution to the arts in Wales. It is given by the Machynlleth Tabernacle Trust to pre-eminent figures in music, art and literature in rotation. The award takes its name af ...

, is named after Glyndŵr.

In 2008, what is now Glyndŵr University was established in Wrexham

Wrexham ( ; cy, Wrecsam; ) is a city and the administrative centre of Wrexham County Borough in Wales. It is located between the Welsh mountains and the lower Dee Valley, near the border with Cheshire in England. Historically in the count ...

, Wales, originally established as the Wrexham School of Science and Art in 1887.

Glendower Residence, at the University of Cape Town

The University of Cape Town (UCT) ( af, Universiteit van Kaapstad, xh, Yunibesithi ya yaseKapa) is a public research university in Cape Town, South Africa. Established in 1829 as the South African College, it was granted full university statu ...

in South Africa, was named after Owain Glyndŵr. The residence was opened in 1993 having previously been the Glendower Hotel. The hall of residence houses 135 male students.

Sport

Glyndŵr's personal standard (the quartered arms of Powys and Deheubarth rampant) began to be seen all over Wales on commercial products, and also flags used atrugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In it ...

games and other sporting events.

RGC 1404 (Rygbi Gogledd Cymru/North Wales Rugby) rugby union team is named in honour of the year Owain Glyndŵr was crowned Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

.

Naming of vehicles

At least two ships and one locomotive have been named after Glyndŵr. * In 1808, theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

launched a 36-gun fifth-rate frigate, . She served in the Baltic Sea during the Gunboat War

The Gunboat War (, ; 1807–1814) was a naval conflict between Denmark–Norway and the British during the Napoleonic Wars. The war's name is derived from the Danish tactic of employing small gunboats against the materially superior Royal ...

where she participated in the seizure of Anholt Island, and then in the Channel. Between 1822 and 1824, she served in the West Africa Squadron

The West Africa Squadron, also known as the Preventative Squadron, was a squadron of the British Royal Navy whose goal was to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa. Formed in 1808 after the British Parliam ...

(or 'Preventative Squadron') chasing down slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

s, capturing at least two.

* Owen Glendower, an East Indiaman, a Blackwall frigate built-in 1839.

*In 1923, a 2-6-2

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, represents the wheel arrangement of two leading wheels, six coupled driving wheels and two trailing wheels. This arrangement is commonly called a Prairie.

Overview

The ...

T Vale of Rheidol locomotive was named after Glyndŵr. The locomotive is still operational and was one of a few used by British Rail

British Railways (BR), which from 1965 traded as British Rail, was a state-owned company that operated most of the overground rail transport in Great Britain from 1948 to 1997. It was formed from the nationalisation of the Big Four (British ra ...

until it was privatized

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

.

Literature

Tudor period

After Glyndŵr's death, there was little resistance to English rule. The Tudor dynasty saw Welshmen become more prominent in English society. In '' Henry IV, Part 1'',Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

portrays him as Owen Glendower (the name has since been adopted as the anglicized version of Owain Glyndŵr), wild and exotic; a man who claims to be able to "call spirits from the vasty deep", ruled by magic and tradition in sharp contrast to the more logical but highly emotional Hotspur. Shakespeare further notes Glyndŵr as being "not in the roll of common men" and "a worthy gentleman,/Exceedingly well read, and profited/ In strange concealments, valiant as a lion/And as wondrous affable and as bountiful/As mines of India." (''Henry IV, Part I'', 3.1). And his enemies describe him "that damn'd magician", which was in reference to having the weather on his side in battle.

Modern literature

After his death, Glyndŵr acquired mythical status as the hero awaiting a call to return and liberate his people.Thomas Pennant

Thomas Pennant (14 June OS 172616 December 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family estate, Downing Hall near Whitford, Flintshire, in Wales.

As a naturalist he had ...

, in his ''Tours in Wales'' (1778, 1781 and 1783), searched out and published many of the legends and places associated with the memory of Glyndŵr.

Glyndŵr has been featured in a number of works of modern fiction, including:

* John Cowper Powys: '' Owen Glendower'' (1941).

* Edith Pargeter: ''A Bloody Field by Shrewsbury'' (1972).

* Martha Rofheart: ''Glendower Country'' (1973).

* Rosemary Hawley Jarman

Rosemary Hawley Jarman (27 April 1935 – 17 March 2015) was an English novelist and writer of short stories. Her first novel in 1971 shed light on King Richard III of England.

Life

Jarman was born in Worcester. She was educated first at Saint M ...

: ''Crown in Candlelight'' (1978).

* Roger Zelazny: '' A Night in the Lonesome October'' (1993).

* Malcolm Pryce

Malcolm Pryce (born 1960) is a British author, mostly known for his ''noir'' detective novels.

Biography

Born in Shrewsbury, England, Pryce moved at the age of nine to Aberystwyth, where he later attended Penglais Comprehensive School before l ...

: ''A Dragon to Agincourt'' (2003).

* Rhiannon Ifans: ''Owain Glyndŵr: Prince of Wales'' (2003).

* Rowland Williams: ''Owen Glendower: A Dramatic Biography and Other Poems'' (2008).

* T. I. Adams: ''The Dragon Wakes: A Novel of Wales and Owain Glyndwr'' (2012).

* Maggie Stiefvater: The Raven Cycle

The Raven Cycle is a series of four contemporary fantasy novels written by American author Maggie Stiefvater. The first novel, ''The Raven Boys'', was published by Scholastic in 2012, and the final book, ''The Raven King'', was published on 26 ...

contemporary fantasy novels (2012–16).

* N. Gemini Sasson: ''Uneasy Lies the Crown: A Novel of Owain Glyndwr'' (2012).

Glyndŵr appeared briefly as a past Knight of the Word and a ghost who serves the Lady in Terry Brooks's '' Word/Void'' trilogy. In the books, he is John Ross's ancestor.

Glyndŵr appeared as an agent of the Light in Susan Cooper's novel ''Silver on the Tree'', part of '' The Dark is Rising Sequence''.

For a study of the various ways Glyndŵr has been portrayed in Welsh-language literature of the modern period, see E. Wyn James, ''Glyndŵr a Gobaith y Genedl: Agweddau ar y Portread o Owain Glyndŵr yn Llenyddiaeth y Cyfnod Modern'' ( en, Glyndŵr and the Hope of the Nation: Aspects of the Portrayal of Owain Glyndŵr in the Literature of the Modern Period).

Glyndŵr's name in public use

The Owain Glyndwr Hotel in Corwen is a historic inn. An earlier building had been a monastery and church dating from the age of Glyndŵr in the 14th century, although the current building mostly dates from the 18th century. The waymarked long distance footpath Glyndŵr's Way runs through Mid Wales near to his homelands.As a Welsh Icon

Following the death of Glyndŵr, he acquired mythical status as the hero awaiting a call to return and liberate his people in the classic Welsh mythical role "Y Mab Darogan" ( en, The Foretold Son). Glyndŵr came second toAneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party politician, noted for tenure as Minister of Health in Clement Attlee's government in which he spearheaded the creation of the British National Heal ...

in the 100 Welsh Heroes poll of 2003/4.

Stamps were issued with his likeness in 1974 and 2008, and streets, parks, and public squares were named after him throughout Wales.

There is a campaign to make 16 September, the date Glyndŵr raised his standard, a public holiday

A public holiday, national holiday, or legal holiday is a holiday generally established by law and is usually a non-working day during the year.

Sovereign nations and territories observe holidays based on events of significance to their history ...

in Wales, including by Dafydd Wigley in 2021. Many schools and organisations commemorate the day, and street parades such as (Festival of the flame) are held to celebrate it.

Banners and coat of arms of Glyndŵr

Thomas Pennant

Thomas Pennant (14 June OS 172616 December 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family estate, Downing Hall near Whitford, Flintshire, in Wales.

As a naturalist he had ...

(1726–1798) that chronicle the three journeys he made through Wales between 1773 and 1776.

File:Sant Tomos, St. Thomas, Glyndyfrdwy, Sir Ddinbych, Denbighshire, Wales 07.JPG, Owain Glyndŵr arms used as a sign for a hotel at Pale hall.

Lineage

Owain Glyndŵr's ancestry :See also

* Buildings associated with Owain Glyndŵr * Welsh heraldry * Welsh Seal *List of people who disappeared

Lists of people who disappeared include those whose current whereabouts are unknown, or whose deaths are unsubstantiated. Many people who disappear are eventually declared dead ''in absentia''. Some of these people were possibly subjected to enfo ...

References

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* – * * – * – *External links

* * * * *Cefn Caer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Glyndwr, Owain 14th-century births 1410s deaths 1410s missing person cases 14th-century Welsh lawyers 15th-century monarchs in Europe 15th-century Welsh military personnel * Owain Missing person cases in Wales Monarchs of Powys Welsh princes Year of birth uncertain Year of death uncertain