Oswald Mosley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

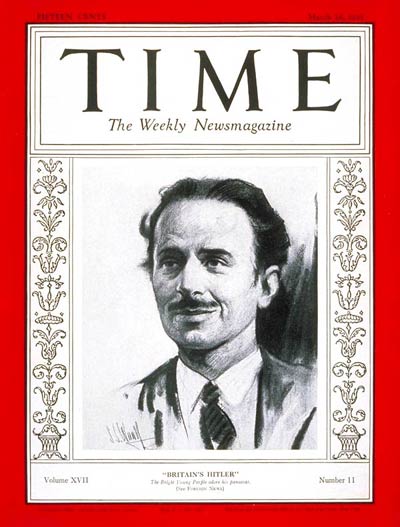

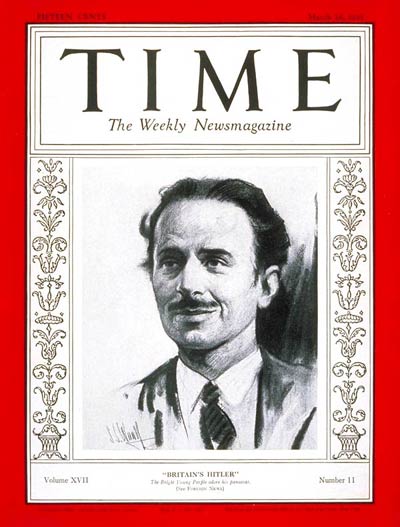

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980), was a British aristocrat and politician who rose to fame during the 1920s and 1930s when he, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, turned to

Mosley left college in 1912, briefly staying in

Mosley left college in 1912, briefly staying in

When the government fell in October, Mosley had to choose a new seat, as he believed that Harrow would not re-elect him as a Labour candidate. He therefore decided to oppose

When the government fell in October, Mosley had to choose a new seat, as he believed that Harrow would not re-elect him as a Labour candidate. He therefore decided to oppose

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley and six other Labour MPs (two of whom resigned after one day) founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the 1931 Ashton-under-Lyne by-election and subsequent by-elections, arguably had a

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley and six other Labour MPs (two of whom resigned after one day) founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the 1931 Ashton-under-Lyne by-election and subsequent by-elections, arguably had a

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's ''

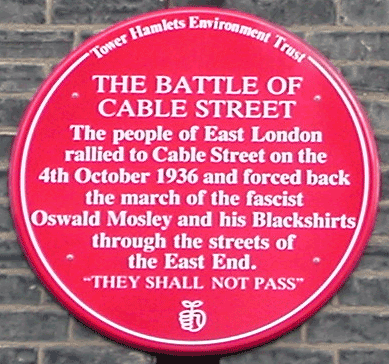

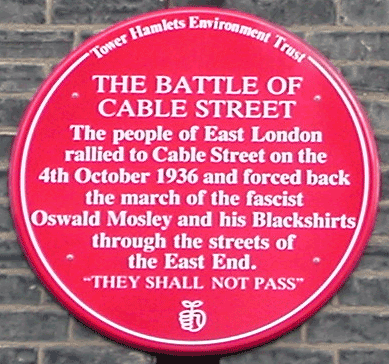

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's '' In October 1936, Mosley and the BUF tried to march through an East London area with a high proportion of Jewish residents. Violence, now called the Battle of Cable Street, resulted between protesters trying to block the march and police trying to force it through. Sir Philip Game, the

In October 1936, Mosley and the BUF tried to march through an East London area with a high proportion of Jewish residents. Violence, now called the Battle of Cable Street, resulted between protesters trying to block the march and police trying to force it through. Sir Philip Game, the

''Not The Nine O'Clock News'': "Baronet Oswald Ernald Mosley"

''Some of the Corpses are Amusing''.

* The BBC Cymru Wales, BBC Wales-produced 2010 revival of ''Upstairs Downstairs (2010 TV series), Upstairs Downstairs'', set in 1936, included a storyline involving Mosley, the BUF and the Battle of Cable Street.

* Mosley, played by Sam Claflin, is the primary antagonist in the fifth and sixth series of the BBC crime drama ''Peaky Blinders (TV series), Peaky Blinders''.

* Mosley was played by Jonathan McGuinness in the first series of the BBC war drama ''World on Fire (TV series), World on Fire''.

Friends of Oswald Mosley

at oswaldmosley.com, containing archives of his speeches and books * * * * * (last accessible, 23 October 2017) * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mosley, Oswald Oswald Mosley, 1896 births 1980 deaths Military personnel from the City of Westminster 16th The Queen's Lancers officers 20th-century English memoirists Anti-Marxism Antisemitism in England Baronets in the Baronetage of Great Britain British Army personnel of World War I British anti–World War II activists British anti-Zionists British Holocaust deniers British political party founders British white supremacists Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Deaths from Parkinson's disease in France English expatriates in France English British Union of Fascist politicians English prisoners and detainees Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Independent Labour Party National Administrative Committee members Independent members of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Mosley baronets Mosley family, Oswald Pan-European nationalism People detained under Defence Regulation 18B People educated at West Downs School People educated at Winchester College People from Burton upon Trent People from Mayfair People with Parkinson's disease Racism in the United Kingdom Royal Flying Corps officers UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 Union Movement politicians

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

. He was Member of Parliament (MP) for Harrow from 1918 to 1924 and for Smethwick

Smethwick () is an industrial town in the Sandwell district, in the county of the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It lies west of Birmingham city centre. Historically it was in Staffordshire and then Worcestershire before bei ...

from 1926 to 1931. He founded the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

(BUF) in 1932 and led it until its forced disbandment in 1940.

After military service during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Mosley became the youngest sitting member of Parliament, representing Harrow from 1918

The ceasefire that effectively ended the World War I, First World War took place on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of this year. Also in this year, the Spanish flu pandemic killed 50–100 million people wor ...

, first as a member of the Conservative Party, then an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

, and finally joining the Labour Party. At the 1924 general election he stood in Birmingham Ladywood

Birmingham Ladywood is a United Kingdom constituencies, constituency in the city of Birmingham that was created in 1918. The seat has been represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the Unit ...

against the future prime minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

, coming within 100 votes of defeating him. Mosley returned to Parliament as the Labour MP for Smethwick at a by-election in 1926 and served as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is a ministerial office in the Government of the United Kingdom. Excluding the prime minister, the chancellor is the highest ranking minister in the Cabinet Office, immediately after the prime minister ...

in the Labour government of 1929–1931. In 1928 he succeeded his father as the sixth Mosley baronet, a title in his family for over a century. Some considered Mosley a rising star and a possible future prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

. He resigned in 1930 over discord with the government's unemployment policies. He chose not to defend his Smethwick constituency at the 1931 general election, instead unsuccessfully standing in Stoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England. It has an estimated population of 259,965 as of 2022, making it the largest settlement in Staffordshire ...

.

Mosley's New Party became the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1932. As its leader he publicly espoused antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

and sought alliances with Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

and Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. Fascist violence under Mosley's leadership culminated in the Battle of Cable Street in 1936, during which anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

demonstrators including trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

ists, liberals, socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

s, communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

s, anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

s and British Jews

British Jews (often referred to collectively as British Jewry or Anglo-Jewry) are British citizens who are Jewish. The number of people who identified as Jews in the United Kingdom rose by just under 4% between 2001 and 2021.

History

The fir ...

prevented the BUF from marching through the East End of London. Mosley subsequently held a series of rallies around London, and the BUF increased its membership there.

In 1939 Mosley was implicated in a fascist conspiracy organised by the Right Club against the British government by Archibald Maule Ramsay, albeit all evidence indicates that he soon distanced himself from them, viewing the group and its aims as too extreme.

In May 1940, after the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Mosley was imprisoned and the BUF was made illegal. He was released in 1943 and, politically disgraced by his association with fascism, moved abroad in 1951, spending most of the remainder of his life in France and Ireland. He stood for Parliament during the post-war era but received relatively little support. During this period he was an advocate of pan-European nationalism

European nationalism (sometimes called pan-European nationalism) is a form of pan-nationalism based on a pan-European identity. It is considered minor since the National Party of Europe disintegrated in the 1970s.

It is distinct from Pro-Europ ...

, developing the Europe a Nation ideology, and was an early proponent of conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

concerning Holocaust-denial.

Early life

Childhood and education

Mosley was born on 16 November 1896 at 47 Hill Street,Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of Westminster, London, England, in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. It is between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane and one of the most expensive districts ...

, London. He was the eldest of the three sons of Sir Oswald Mosley, 5th Baronet (1873–1928), and Katharine Maud Edwards-Heathcote (1873–1948), daughter of Captain Justinian Edwards-Heathcote, of Apedale Hall, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

; they had been married the year before. He had two younger brothers: Edward Heathcote Mosley (1899–1980) and John Arthur Noel Mosley (1901–1973). His father was a third cousin to Claude Bowes-Lyon, 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, making Mosley a fourth cousin to Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was al ...

.

The progenitor, and earliest-attested ancestor, of the Mosley family was Ernald de Mosley ( 12th century), Lord of the Manor

Lord of the manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England and Norman England, referred to the landholder of a historical rural estate. The titles date to the English Feudalism, feudal (specifically English feudal barony, baronial) system. The ...

of Moseley, Staffordshire, during the reign of King John. Nicholas Mosley was a wealthy salesman in the 16th century, and was important in the development of Manchester, before eventually becoming Mayor of London

The mayor of London is the chief executive of the Greater London Authority. The role was created in 2000 after the Greater London devolution referendum in 1998, and was the first directly elected mayor in the United Kingdom.

The current ...

; the family took a violent part in the Peterloo Massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Eighteen people died and 400–700 were injured when the cavalry of the Yeomen charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who ...

. Two branches of the Mosley family existed – a significant cotton trading family who lived in Lancashire, and a farming family who lived in Rolleston; Oswald was descended from the former. The family were prominent landholders in Staffordshire and seated at Rolleston Hall, near Burton upon Trent

Burton upon Trent, also known as Burton-on-Trent or simply Burton, is a market town in the borough of East Staffordshire in the county of Staffordshire, England, close to the border with Derbyshire. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 censu ...

. Three baronetcies

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

were created, two of which are now extinct (see Mosley baronets for further history of the family); a barony was created for Tonman Mosley, brother of the 4th Baronet, but also became extinct. By the 19th century, reformers had taken control of the Manchester Court leet

The court leet was a historical court baron (a type of manorial court) of England and Wales and Ireland that exercised the "view of frankpledge" and its attendant police jurisdiction, which was normally restricted to the hundred courts.

Etymo ...

, which formerly belonged to the family, and the Mosleys had little influence by the latter half of the century. Oswald's grandfather Sir Oswald Mosley, 4th Baronet, was a campaigner against Jewish emancipation. Oswald noted in his autobiography '' My Life'' that he was glad to have come from an 'old English family'.

His mother wrote in her diary that his birth took 18 hours after he began to arrive at 6:00am, her own mother staying by her side for the whole duration. The family doctor, Sir John Williams, gave her chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane (often abbreviated as TCM), is an organochloride with the formula and a common solvent. It is a volatile, colorless, sweet-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to refrigerants and po ...

and the baby was delivered at 11:40pm. Her husband, who was addicted to both gambling and alcohol, wrote a large number of letters to relatives about the event, and celebrated at the Epsom Derby

The Derby Stakes, more commonly known as the Derby and sometimes referred to as the Epsom Derby, is a Group races, Group 1 flat Horse racing, horse race in England open to three-year-old Colt (horse), colts and Filly, fillies. It is run at Ep ...

; he was mostly an absent husband.

In childhood, Mosley moved from what he described as a "wayside house" to Rolleston Hall, which had been inherited in 1879 by the 4th Baronet. The Hall was a large building maintained by gardeners and servants. Biographer Stephen Dorril has suggested that the treatment of the workers at the mansion, who laboured with no possibility to become more successful, may have impressed itself on Mosley's worldview and such treatment came to be part of his fascism.

Mosley loved his mother, whom he felt protective towards; in the 1970s, he burned her diaries to avoid investigative authors depicting her negatively, using them as evidence, although he kept the entries for the first four years of his own life, and for his mother's birthday, 2 January. Likewise, she celebrated Mosley and developed his ego. His father – nicknamed "Waldie" – was an amateur boxer, a Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

and a womaniser. Mosley's father gained the image of a scoundrel, although Mosley did not find the description to be accurate. Nonetheless, "Waldie" acted aggressively towards his wife and child, which led to Mosley idolising his mother instead. In 1901, when Mosley was aged five and while his mother was pregnant with her third child, the couple split over his womanising – Edwards-Heathcote had discovered letters revealing that her husband was saying and gifting the same things to his other lovers as to her.

After Mosley's parents separated, he was raised by his mother, who went to live at Betton Hall near Market Drayton

Market Drayton is a market town and civil parish on the banks of the River Tern in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is close to the Cheshire and Staffordshire borders. It is located between the towns of Whitchurch, Shropshire, Wh ...

, and his paternal grandfather, Sir Oswald Mosley, 4th Baronet. His mother had a small alimony

Alimony, also called aliment (Scotland), maintenance (England, Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales, Canada, New Zealand), spousal support (U.S., Canada) and spouse maintenance (Australia), is a legal obligation on a person to provide ...

, and was impoverished by comparison to the rest of the family. Mosley rarely being able to see his father, his mother became more attached to him. His grandfather took the role of a male parental figure in Mosley's life; Likewise, his grandfather disliked his father, and saw Mosley as a substitute son; the 4th Baronet was seen as a masculine figure by Mosley, and developed his own masculine image based on his grandfather, alongside various pop-cultural ideas.

Mosley studied at West Downs School in Winchester from 1906 onward, eventually joined by Edward, where Oswald developed a reputation as a debater. He then joined Winchester College

Winchester College is an English Public school (United Kingdom), public school (a long-established fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) with some provision for day school, day attendees, in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It wa ...

in 1909 at the age of 12, a year early, and found school both hard and boring; he did not socialise. During this period he hunted extensively, shooting 50 partridges, 18 pheasants, 11 rabbits and 10 hares over the winter from 1909 to 1910, as well as fishing at Rolleston. He also became a boxer by age 15, winning a light-weight championship, and attempted to enter the Public Schools' boxing championship, but was forbade by his headmaster; Mosley then took up fencing instead. He was a fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

champion in his school days, winning titles in both foil

Foil may refer to:

Materials

* Foil (metal), a quite thin sheet of metal, usually manufactured with a rolling mill machine

* Metal leaf, a very thin sheet of decorative metal

* Aluminium foil, a type of wrapping for food

* Tin foil, metal foil ma ...

and sabre

A sabre or saber ( ) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the Early Modern warfare, early modern and Napoleonic period, Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such a ...

, and becoming the first boy to win both and the youngest to win either at the Public Schools' championship. He retained an enthusiasm for the sport throughout his life.

Military service

Mosley left college in 1912, briefly staying in

Mosley left college in 1912, briefly staying in Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port, port city in the Finistère department, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of a peninsula and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an impor ...

in summer 1913, where he competed in fencing. After returning to England, he became keen on entering the army, entering the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC) was a United Kingdom, British military academy for training infantry and cavalry Officer (armed forces), officers of the British Army, British and British Indian Army, Indian Armies. It was founded in 1801 at Gre ...

in January 1914. He considered his period at the military college to be ‘one of the happiest times of isentire life”, but was expelled in June for a "riotous act of retaliation" against a fellow student. John Masters made a claim that Mosley was thrown out of a window by other cadets; according to Dorril, he had actually slipped and fallen while recruiting for the retaliation against a group of cadets who had attacked him. He was sent away from the college that weekend.

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he was commissioned into the British cavalry unit the 16th The Queen's Lancers and fought in France on the Western Front. He transferred to the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

as a pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its Aircraft flight control system, directional flight controls. Some other aircrew, aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are al ...

and an air observer, but while demonstrating in front of his mother and sister he crashed, which left him with a permanent limp, as well as a reputation for being brave and somewhat reckless. He returned to the Lancers, but was invalided out with an injured leg. He spent the remainder of the war at desk jobs in the Ministry of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis o ...

and in the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

.

Marriage to Lady Cynthia Curzon

On 11 May 1920 he married Lady Cynthia "Cimmie" Curzon (1898–1933), second daughter ofGeorge Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

(1859–1925), Viceroy of India

The governor-general of India (1833 to 1950, from 1858 to 1947 the viceroy and governor-general of India, commonly shortened to viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom in their capacity as the Emperor of ...

1899–1905, Foreign Secretary 1919–1924, and Lord Curzon's first wife, the American mercantile heiress Mary Leiter.

Lord Curzon had to be persuaded that Mosley was a suitable husband, as he suspected Mosley was largely motivated by social advancement in Conservative Party politics and Cynthia's inheritance. The wedding took place in the Chapel Royal in St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, England. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster. Although no longer the principal residence ...

in London. The hundreds of guests included King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

and Queen Mary, as well as foreign royalty such as the Duke and Duchess of Brabant (later King Leopold III and Queen Astrid of Belgium).

During this marriage he began an extended affair with his wife's younger sister, Lady Alexandra Metcalfe, and a separate affair with their stepmother, Grace Curzon, Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston

Grace Elvina Curzon, Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston, GBE (née Hinds, formerly Duggan; 14 April 1879 – 29 June 1958), was an American-born British marchioness and the second wife of George Curzon, former Viceroy of India.

Early life

Curzo ...

, the American-born second wife and widow of Lord Curzon. He succeeded to the Mosley baronetcy of Ancoats upon his father's death in 1928.

Entering Westminster as a Conservative

Mosley was first encouraged to enter politics by F. E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead. By the end of the First World War Mosley, aged 21, had decided to go into politics as a member of Parliament, as he had no university education or practical experience because of the war. He was driven by, and in Parliament spoke of, a passionate conviction to avoid any future war, and this seemingly motivated his career. Uninterested in party labels, Mosley primarily identified himself as a representative of the "war generation" who would aim to create a "land fit for heroes." Largely because of his family background and war service, local Conservative and Liberal associations made appeals to Mosley in several constituencies. Mosley considered contesting the constituency ofStone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

in his home county of Staffordshire, but ultimately chose the Conservative stronghold of Harrow, for it was closer to London and, as Mosley claimed, a seat that he sought to win on his own merits, free from family connections. On 23 July 1918 Mosley competed with three other candidates for the Conservative nomination at the upcoming general election. Though his 15-minute speech "fell flat," Mosley won over the 43 delegates with the "lucid and trenchant manner" in which he answered their questions. Mosley's opponent in the parliamentary election was an independent, A. R. Chamberlayne, an elderly solicitor

A solicitor is a lawyer who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and enabled to p ...

who complained that the well-connected, wealthy Mosley was "a creature of the party machine" and too young to serve as a member of Parliament. Mosley retorted that many of Britain's greatest politicians entered Parliament between the ages of 19 to 25, such as Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a British British Whig Party, Whig politician and statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centurie ...

, William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman who served as the last prime minister of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1783 until the Acts of Union 1800, and then first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, p ...

, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

and Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903), known as Lord Salisbury, was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for ...

. Mosley chose red as his campaign colour rather than the traditional blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB color model, RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB color model, RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between Violet (color), violet and cyan on the optical spe ...

associated with conservatism. Mosley easily defeated Chamberlayne with a majority of nearly 11,000.

He was the youngest member of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

to take his seat, although Joseph Sweeney, a Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

member, and therefore an abstentionist, was seven months younger. He soon distinguished himself as an orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14 ...

and political player, one marked by confidence, and made a point of speaking in the Commons without notes.

Mosley was an early supporter of the economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

. Mosley's economic programme, which he coined "socialistic imperialism," advocated for improved industrial wages and hours, the nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

of electricity and transportation, slum-clearance, the protection of "essential industries" from "unfair competition," and higher government investment in education, child-welfare, and health services.

Crossing the floor

Mosley was at this time falling out with the Conservatives over their Irish policy, and condemned the operations of theBlack and Tans

The Black and Tans () were constables recruited into the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as reinforcements during the Irish War of Independence. Recruitment began in Great Britain in January 1920, and about 10,000 men enlisted during the conflic ...

against civilians during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

. He was secretary of the Peace with Ireland Council. As secretary of the council he proposed sending a commission to Ireland to examine on-the-spot reprisals by the Black and Tans. T. P. O'Connor, a prominent MP of the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

, later wrote to Mosley's wife Cynthia, "I regard him as the man who really began the break-up of the Black and Tan savagery." In mid-1920, Mosley issued a memorandum proposing that Britain's governance over Ireland should mirror the policy of the United States towards Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, in effect granting Ireland internal autonomy whilst retaining British oversight regarding defence and foreign policy matters. In November 1920 he questioned the Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British Dublin Castle administration, administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretar ...

, Sir Hamar Greenwood, in Parliament on the case of Eileen Quinn, a young pregnant mother who was shot and killed in County Galway

County Galway ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region, taking up the south of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. The county population was 276,451 at the 20 ...

by the Black and Tans.

In late 1920 he crossed the floor

In some parliamentary systems (e.g., in Canada and the United Kingdom), politicians are said to cross the floor if they formally change their political affiliation to a political party different from the one they were initially elected under. I ...

to sit as an independent MP on the opposition side of the House of Commons. Having built up a following in his constituency, he retained it against a Conservative challenge in the 1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic), Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éirean ...

and 1923 general elections.

According to Lady Mosley's autobiography,

Joining Labour

By now Mosley was drifting to thepolitical left

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social hierarchies. Left-wing politi ...

and gaining the attention of both the Liberals and Labour for his foreign policy polemics, which advocated for a strong League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

and isolationism

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

(i.e. Britain should only go to war if it or the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

were attacked). Mosley was growing increasingly attracted to the Labour Party, which had recently formed its first government (under Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

) after the 1923 general election. On 27 March 1924 Mosley applied for party membership. Shortly thereafter he joined the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party (UK), Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse work ...

(ILP). MacDonald, who believed that aristocratic members gave Labour an air of respectability, was congratulated by ''The Manchester Guardian'' on "the fine new recruit he has secured."

Unsuccessfully challenging Chamberlain

When the government fell in October, Mosley had to choose a new seat, as he believed that Harrow would not re-elect him as a Labour candidate. He therefore decided to oppose

When the government fell in October, Mosley had to choose a new seat, as he believed that Harrow would not re-elect him as a Labour candidate. He therefore decided to oppose Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

in Birmingham Ladywood

Birmingham Ladywood is a United Kingdom constituencies, constituency in the city of Birmingham that was created in 1918. The seat has been represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the Unit ...

. Mosley campaigned aggressively in Ladywood, and accused Chamberlain of being a "landlords' hireling" in reference to Chamberlain's controversial Rent Act of 1923. Chamberlain, outraged, demanded Mosley to retract the claim "as a gentleman". Mosley, whom Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

described as "a cad and a wrong 'un", refused to withdraw the allegation. Mosley was noted for bringing excitement and energy to the campaign. Leslie Hore-Belisha, then a Liberal politician who later became a senior Conservative, recorded his impressions of Mosley as a platform orator at this time:

Together, Oswald and Cynthia Mosley proved an alluring couple, and many members of the working class in Birmingham succumbed to their charm for, as the historian Martin Pugh described, "a link with powerful, wealthy and glamorous men and women appealed strongly to those who endured humdrum and deprived lives". It took several re-counts before Chamberlain was declared the winner by 77 votes. Mosley blamed poor weather for the result. His period outside Parliament was used to develop a new economic policy for the ILP, which eventually became known as the Birmingham Proposals; they continued to form the basis of Mosley's economics until the end of his political career.

Mosley was critical of Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

's policy as Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

. After Churchill returned Britain to the gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

, Mosley claimed that, "faced with the alternative of saying goodbye to the gold standard, and therefore to his own employment, and goodbye to other people's employment, Mr. Churchill characteristically selected the latter course."

India and Gandhi

Among his many travels, Mosley travelled toBritish India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

accompanied by Lady Cynthia in the winter of 1924, which he would later characterise as "a land of contrast, of ineffable beauty and of darkest sorrow, a jewel of the world, which challenges mankind to save it." His father-in-law's past as Viceroy of India

The governor-general of India (1833 to 1950, from 1858 to 1947 the viceroy and governor-general of India, commonly shortened to viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom in their capacity as the Emperor of ...

allowed for the acquaintance of various personalities along the journey. They travelled by ship and stopped briefly in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

in the Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt () was the legal form of the Egyptian state during the latter period of the Muhammad Ali dynasty's reign, from the United Kingdom's recognition of Egyptian independence in 1922 until the abolition of the monarchy of Eg ...

.

Having initially arrived in Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

(present-day Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

), the journey then continued through mainland India. They spent these initial days in the government house of Ceylon, followed by Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

and then Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

, where the governor at the time was Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton

Victor Alexander George Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton (9 August 1876 – 25 October 1947), styled Viscount Knebworth from 1880 to 1891, was a British politician and colonial administrator. He served as List of governors of Bengal Pres ...

. During this journey Mosley came in contact with many prominent activists, including Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 187611 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the inception of Pa ...

, Chittaranjan Das

Chittaranjan Das (5 November 1870 – 16 June 1925), popularly called ''Deshbandhu'' (friend of the country), was a Bengali freedom fighter, political activist and lawyer during the Indian Independence Movement and the political guru of Indi ...

and Motilal Nehru

Motilal Nehru (6 May 1861 – 6 February 1931) was an Indian lawyer, activist, and politician affiliated with the Indian National Congress. He served as the Congress President twice, from 1919 to 1920 and from 1928 to 1929. He was a patriarch ...

.

Mosley met Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

through Charles Freer Andrews

Charles Freer Andrews (12 February 1871 – 5 April 1940) was an Church of England, Anglican priest and Christian missionary, educator and social reformer, and an activist for Indian independence movement, Indian independence. He became a clos ...

, a clergyman and an intimate friend of the "Indian Saint", as Mosley described him. They met in Kadda, where Gandhi was quick to invite him to a private conference in which Gandhi was chairman. Mosley later called Gandhi a "sympathetic personality of subtle intelligence".

Return to Parliament

On 22 November 1926 the Labour-held seat of Smethwick fell vacant upon the resignation of John Davison, and Mosley was confident that this seat would return him to Westminster (having lost against Chamberlain in 1924). In his autobiography Mosley felt that the campaign was dominated by Conservative attacks on him for being too rich, including claims that he was covering up his wealth. In fact, during this campaign, the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

'' frequently attacked "Mr. Silver Spoon Mosley" for preaching socialism "in a twenty guineas Savile Row suit" whilst Lady Cynthia wore a "charming dress glittering with diamonds

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of electricity, and insol ...

." As the historian Robert Skidelsky

Robert Jacob Alexander Skidelsky, Baron Skidelsky, (born 25 April 1939) is a British economic historian. He is the author of a three-volume, award-winning biography of British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946). Skidelsky read histor ...

writes, "The papers were full of gossipy items about the wealthy socialist couple frolicking on the Riviera, spending thousands of pounds in renovating their 'mansion' and generally living a debauched aristocratic life." The recurring accusation against Mosley was that he was a "champagne socialist

Champagne socialist is a political term commonly used in the United Kingdom. It is a popular epithet that implies a degree of hypocrisy, and it is closely related to the concept of the liberal elite. The phrase is used to describe self-identifie ...

" who "never did a day's work in his life." Mosley, in response, told his Smethwick supporters, "While I am being abused by the Capitalist Press I know I am doing effective work for the Labour cause." At the by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, or a bypoll in India, is an election used to fill an office that has become vacant between general elections.

A vacancy may arise as a result of an incumben ...

's polling day (21 December), Mosley was victorious with a majority of 6,582 over the Conservative candidate, M. J. Pike.

In 1927 he mocked the British Fascists as "black-shirted buffoons, making a cheap imitation of ice-cream sellers". The ILP elected him to Labour's National Executive Committee.

Mosley and Cynthia were committed Fabians in the 1920s and at the start of the 1930s. Mosley appears in a list of names of Fabians from ''Fabian News'' and the ''Fabian Society Annual Report 1929–31''. He was Kingsway Hall

The Kingsway Hall in Holborn, London, was the base of the West London Mission (WLM) of the Methodist Church, and eventually became one of the most important recording venues for classical music and film music.

It was built in 1912 and demolish ...

lecturer in 1924 and Livingstone Hall lecturer in 1931.

Office

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

Mosley then made a bold bid for political advancement within the Labour Party. He was close toRamsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

and hoped for one of the Great Offices of State

The Great Offices of State are senior offices in the Government of the United Kingdom, UK government. They are the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Prime Minister, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Foreign Secretary (United Kingdom), For ...

, but when Labour won the 1929 general election he was appointed only to the post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is a ministerial office in the Government of the United Kingdom. Excluding the prime minister, the chancellor is the highest ranking minister in the Cabinet Office, immediately after the prime minister ...

, a position without portfolio. He was given responsibility for solving the unemployment problem, but found that his radical proposals were blocked either by Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

James Henry Thomas

James Henry Thomas (3 October 1874 – 21 January 1949) was a Welsh trade unionist and politician. He was involved in a political scandal involving budget leaks.

Early career and trade union activities

Thomas was born in Newport, Monmouth ...

or by the Cabinet.

Mosley Memorandum

Realising the economic uncertainty that was facing the nation because of the death of its domestic industry, Mosley put forward a scheme in the "Mosley Memorandum" that called for hightariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

s to protect British industries from international finance

International finance (also referred to as international monetary economics or international macroeconomics) is the branch of monetary economics, monetary and macroeconomics, macroeconomic interrelations between two or more countries. Internation ...

and transform the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

into an autarkic trading bloc, for state nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

of main industries, for higher school-leaving age

The school leaving age is the minimum age a person is legally allowed to cease attendance at an institute of compulsory secondary education. Most countries have their school leaving age set the same as their minimum full-time employment age, thus ...

s and pensions

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a "defined benefit plan", wher ...

to reduce the labour surplus, and for a programme of public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and procured by a government body for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, ...

to solve interwar poverty and unemployment. Furthermore, the memorandum laid out the foundations of the corporate state (not to be confused with corporatocracy

Corporatocracy or corpocracy is an economic, political and judicial system controlled or influenced by business corporations or corporate Interest group, interests.

The concept has been used in explanations of bank bailouts, excessive pay for ...

) which intended to combine businesses, workers and the government into one body as a way to "Obliterate class conflict and make the British economy

The United Kingdom has a highly developed social market economy. From 2017 to 2025 it has been the sixth-largest national economy in the world measured by nominal gross domestic product (GDP), tenth-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP), ...

healthy again".

Mosley published this memorandum because of his dissatisfaction with the laissez-faire attitudes held by both Labour and the Conservative party, and their passivity towards the ever-increasing globalisation of the world, and thus looked to a modern solution to fix a modern problem. But it was rejected by the Cabinet and by the Parliamentary Labour Party

The Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) is the parliamentary group of the Labour Party in the British House of Commons. The group comprises the Labour members of parliament as a collective body. Commentators on the British Constitution sometimes ...

, and in May 1930 Mosley resigned from his ministerial position. At the time, according to Lady Mosley's autobiography, the weekly Liberal-leaning paper ''The Nation and Athenaeum

''The Nation and Athenaeum'', or simply ''The Nation'', was a United Kingdom political weekly newspaper with a Liberal/ Labour viewpoint. It was formed in 1921 from the merger of the '' Athenaeum'', a literary magazine published in London since ...

'' wrote: "The resignation of Sir Oswald Mosley is an event of capital importance in domestic politics... We feel that Sir Oswald has acted rightly—as he has certainly acted courageously—in declining to share any longer in the responsibility for inertia." In October he attempted to persuade the Labour Party Conference

The Labour Party Conference is the annual conference of the British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party. It is formally the supreme decision-making body of the party and is traditionally held in the final week of September, during the party conferen ...

to accept the Memorandum, but was defeated again.

The Mosley Memorandum won the support of the economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

, who stated that "it was a very able document and illuminating". Keynes also wrote, "I like the spirit which informs the document. A scheme of national economic planning to achieve a right, or at least a better, balance of our industries between the old and the new, between agriculture and manufacture, between home development and foreign investment; and wide executive powers to carry out the details of such a scheme. That is what it amounts to. ... hemanifesto offers us a starting point for thought and action. ... It will shock—it must do so—the many good citizens of this country...who haveAccording to Lady Mosley's autobiography, thirty years later, in 1961,laissez-faire ''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...in their craniums, their consciences, and their bones ... But how anyone professing and calling himself a socialist can keep away from the manifesto is a more obscure matter."

Richard Crossman

Richard Howard Stafford Crossman (15 December 1907 – 5 April 1974) was a British Labour Party politician. A university classics lecturer by profession, he was elected a Member of Parliament in 1945 and became a significant figure among the ...

wrote: "this brilliant memorandum was a whole generation ahead of Labour thinking." As his book, ''The Greater Britain'', focused on the issues of free trade, the criticisms against globalisation that he formulated can be found in critiques of contemporary globalisation. He warns nations that buying cheaper goods from other nations may seem appealing but ultimately ravage domestic industry and lead to large unemployment, as seen in the 1930s. He argues that trying to "challenge the 50-year-old system of free trade ... exposes industry in the home market to the chaos of world conditions, such as price fluctuation, dumping, and the competition of sweated labour, which result in the lowering of wages and industrial decay."

In a newspaper feature, Mosley was described as "a strange blend of J.M. Keynes and Major Douglas of credit fame". From July 1930 he began to demand that government must be turned from a "talk-shop" into a "workshop."

In 1992 Prime Minister John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

, examined Mosley's ideas in order to find an unorthodox solution to the aftermath of the 1990–91 economic recession.

New Party

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley and six other Labour MPs (two of whom resigned after one day) founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the 1931 Ashton-under-Lyne by-election and subsequent by-elections, arguably had a

Dissatisfied with the Labour Party, Mosley and six other Labour MPs (two of whom resigned after one day) founded the New Party.

Its early parliamentary contests, in the 1931 Ashton-under-Lyne by-election and subsequent by-elections, arguably had a spoiler effect

In social choice theory and politics, a spoiler effect happens when a losing candidate affects the results of an election simply by participating. Voting rules that are not affected by spoilers are said to be spoilerproof.

The frequency and se ...

in splitting the left-wing vote and allowing Conservative candidates to win. Despite this, the organisation gained support among many Labour and Conservative politicians who agreed with his corporatist economic policy, and among these were Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, noted for spearheading the creation of the British National Health Service during his t ...

and the future prime minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

. Mosley's corporatism

Corporatism is an ideology and political system of interest representation and policymaking whereby Corporate group (sociology), corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, come toget ...

was complemented by Keynesianism

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomics, macroeconomic theories and Economic model, models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongl ...

, with Robert Skidelsky stating, "Keynesianism was his great contribution to fascism."

The New Party increasingly inclined to fascist policies, but Mosley was denied the opportunity to get his party established when during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

the 1931 general election was suddenly called. The party's candidates, including Mosley himself running in Stoke which had been held by his wife, lost the seats they held and won none. As the New Party gradually became more radical and authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

, many previous supporters defected from it. According to Lady Mosley's autobiography, shortly after the 1931 election Mosley was described by ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'':

When Sir Oswald Mosley sat down after hisFree Trade Hall The Free Trade Hall on Peter Street, Manchester, England, was constructed in 1853–56 on St Peter's Fields, the site of the Peterloo Massacre. It is now a Radisson Hotels, Radisson hotel. The hall was built to commemorate the repeal of the Corn ...speech inManchester Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...and the audience, stirred as an audience rarely is, rose and swept a storm of applause towards the platform—who could doubt that here was one of those root-and-branch men who have been thrown up from time to time in the religious, political and business story of England. First that gripping audience is arrested, then stirred and finally, as we have said, swept off its feet by a tornado ofperoration is the system used for the organization of arguments in the context of Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "organization" or "arrangement". It is the second of five canons of classical rhetoric (the first be ...yelled at the defiant high pitch of a tremendous voice.

Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British politician, writer, broadcaster and gardener. His wife was Vita Sackville-West.

Early life and education

Nicolson was born in Tehran, Persia, the youngest son of dipl ...

, editor of the New Party's newspaper, ''Action'', recorded in his diary that Mosley personally decided to pursue fascism and the formation of a "trained and disciplined force" on 21 September 1931, following a recent Communist-organised disturbance at a public meeting attended by 20,000 people in Glasgow Green

Glasgow Green is a park in the east end of Glasgow, Scotland, on the north bank of the River Clyde. Established in the 15th century, it is the oldest park in the city. It connects to the south via the St Andrew's Suspension Bridge.

History

In ...

. Approximately four weeks before the general election, Mosley was approached by Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

to ally with the newly-formed National Government coalition led by Baldwin and MacDonald, with Nicolson writing that "the Tories are anxious to get some of us in and are prepared to do a secret deal." Throughout early 1932 David Margesson, the chief whip

The Chief Whip is a political leader whose task is to enforce the whipping system, which aims to ensure that legislators who are members of a political party attend and vote on legislation as the party leadership prescribes.

United Kingdom

I ...

of the Conservatives, continually attempted to persuade Mosley to rejoin the party. Meanwhile, Mosley was also approached by right-wing " die hards" who opposed the National Government and Baldwin's "centrist" leadership of the Conservative Party. This group included Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, who " romisedto come out in his support" should Mosley contest a by-election, and Harold Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere, the owner of the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

'' and the ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily Tabloid journalism, tabloid newspaper. Founded in 1903, it is part of Mirror Group Newspapers (MGN), which is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the tit ...

''. In addition, Nicolson noted that Mosley was being courted by Joseph Kenworthy

Joseph Montague Kenworthy, 10th Baron Strabolgi (7 March 1886 – 8 October 1953), was a Liberal Party (UK), Liberal and then a Labour Party Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom.

Education and naval ...

to "lead the Labour Party." In the end, however, Mosley refused to return to the "machine" of the "old parties." Convinced that fascism was the necessary path for Britain, the New Party was dissolved in April 1932.

Fascism

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's ''

After his election failure in 1931, Mosley went on a study tour of the "new movements" of Italy's ''Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word , 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 192 ...

'' Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

and other fascists, and returned convinced, particularly by Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

's economic programme, that it was the way forward for Britain. He was determined to unite the existing fascist movements and created the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

(BUF) in 1932.

The British historian Matthew Worley argues that Mosley's adoption of fascism stemmed from three key factors. First, Mosley interpreted the Great Slump as proof that Britain's economy, which had historically favoured liberal capitalism, required a fundamental overhaul in order to survive the rise of cheap, global competition. Second, as a result of his experience as a Labour minister, Mosley grew to resent the apparent gridlock

Gridlock is a form of traffic congestion where continuous queues of vehicles block an entire network of intersecting streets, bringing traffic in all directions to a complete standstill. The term originates from a situation possible in a grid ...

inherent in parliamentary democracy (see criticism of democracy). Mosley believed that party politics, parliamentary debate, and the formalities of bill passage hindered effective action in addressing the pressing economic issues of the post-war world. Finally, Mosley became convinced that the Labour Party was not an effective vehicle for the promulgation of "the radical measures that he believed were necessary to prevent Britain’s decline." As Worley notes about Mosley, "Cast adrift from the political mainstream, he saw two alternative futures. One was the 'slow and almost imperceptible decline' of Britain to the ' level of a Spain'... nd the othera deepening sense of crisis opening the way for a 'constructive alternative' to take the place of both liberal capitalism and parliamentary democracy." Mosley believed that Britain was in danger of a Communist revolution

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism. Depending on the type of government, the term socialism can be used to indicate an intermediate stage between ...

, of which only fascism could effectively combat.

The BUF was protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

, strongly anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

ic to the point of advocating authoritarianism. He claimed that the Labour Party was pursuing policies of "international socialism", while fascism's aim was "national socialism". It claimed membership as high as 50,000, and had the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

'' and ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily Tabloid journalism, tabloid newspaper. Founded in 1903, it is part of Mirror Group Newspapers (MGN), which is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the tit ...

'' among its earliest supporters. The ''Mirror'' piece was a guest article by the ''Daily Mail'' owner Viscount Rothermere and an apparent one-off; despite these briefly warm words for the BUF, the paper was so vitriolic in its condemnation of European fascism

Fascist movements in Europe were the set of various fascist ideologies which were practiced by governments and political organizations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist move ...

that Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

added the paper's directors to a hit list in the event of a successful Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (), was Nazi Germany's code name for their planned invasion of the United Kingdom. It was to have taken place during the Battle of Britain, nine months after the start of the Second World ...

. The ''Mail'' continued to support the BUF until the Olympia rally in June 1934.

Mosley's supporters at this time included the novelist Henry Williamson, the military theorist J. F. C. Fuller

Major-General John Frederick Charles "Boney" Fuller (1 September 1878 – 10 February 1966) was a senior British Army officer, military historian, and strategist, known as an early theorist of modern armoured warfare, including categorisin ...

, and the future " Lord Haw Haw", William Joyce

William Brooke Joyce (24 April 1906 – 3 January 1946), nicknamed Lord Haw-Haw, was an American-born Fascism, fascist and Propaganda of Nazi Germany, Nazi propaganda broadcaster during the World War II, Second World War. After moving from ...

.

Mosley had found problems with disruption of New Party meetings, and instituted a corps of black-uniformed paramilitary stewards, the Fascist Defence Force, nicknamed "Blackshirts", like the Italian fascist

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

Voluntary Militia for National Security they were emulating. The party was frequently involved in violent confrontations and riots, particularly with communist and Jewish groups and especially in London. At a large Mosley rally at Olympia on 7 June 1934, his bodyguards' violence caused bad publicity. This and the Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (, ), also called the Röhm purge or Operation Hummingbird (), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Adolf Hitler, urged on by Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, ord ...

in Germany led to the loss of most of the BUF's mass support. Nevertheless, Mosley continued espousing antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

. At one of his New Party meetings in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area, and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest city in the East Midlands with a popula ...

in April 1935, he said, "For the first time I openly and publicly challenge the Jewish interests of this country, commanding commerce, commanding the Press, commanding the cinema, dominating the City of London, killing industry with their sweat-shops. These great interests are not intimidating, and will not intimidate, the Fascist movement of the modern age." The party was unable to fight the 1935 general election.

In October 1936, Mosley and the BUF tried to march through an East London area with a high proportion of Jewish residents. Violence, now called the Battle of Cable Street, resulted between protesters trying to block the march and police trying to force it through. Sir Philip Game, the