Operation Urgent Fury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

The

H-hour for the invasion was set for 05:00 on 25 October 1983. U.S. troops deployed for Grenada by helicopter from

H-hour for the invasion was set for 05:00 on 25 October 1983. U.S. troops deployed for Grenada by helicopter from

U.S. Special Operations Forces were deployed to Grenada beginning on 23 October, before the 25 October invasion. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team 6 and Air Force combat controllers were air-dropped at sea to perform a reconnaissance mission on Point Salines. The helicopter drop went wrong; four SEALs were lost at sea and their bodies never recovered, causing most people to suspect they had drowned. The four SEALs were Machinist Mate 1st Class Kenneth J. Butcher, Quartermaster 1st Class Kevin E. Lundberg, Hull Technician 1st Class Stephen L. Morris, and Senior Chief Engineman Robert R. Schamberger. In an interview conducted by Bill Salisbury and published on 4 October 1990, Kenneth Butcher's widow claimed that she had gone to Grenada hoping that her husband had survived. She said, "There was this fisherman who said he saw four guys in wetsuits come out of the water, and then two days later he saw four bodies being thrown into the water. So we would like to think they made it, 'cause there was a boat smashed up on the beach. We would like to think the four of them got in that boat, made it to shore, got someplace, and were captured. And they're, you know, gonna come back." The SEAL and Air Force survivors continued their mission, but their boats flooded while evading a patrol boat, causing the mission to be aborted. Another SEAL mission on 24 October was also unsuccessful, due to harsh weather, resulting in little intelligence being gathered in advance of the impending intervention.

U.S. Special Operations Forces were deployed to Grenada beginning on 23 October, before the 25 October invasion. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team 6 and Air Force combat controllers were air-dropped at sea to perform a reconnaissance mission on Point Salines. The helicopter drop went wrong; four SEALs were lost at sea and their bodies never recovered, causing most people to suspect they had drowned. The four SEALs were Machinist Mate 1st Class Kenneth J. Butcher, Quartermaster 1st Class Kevin E. Lundberg, Hull Technician 1st Class Stephen L. Morris, and Senior Chief Engineman Robert R. Schamberger. In an interview conducted by Bill Salisbury and published on 4 October 1990, Kenneth Butcher's widow claimed that she had gone to Grenada hoping that her husband had survived. She said, "There was this fisherman who said he saw four guys in wetsuits come out of the water, and then two days later he saw four bodies being thrown into the water. So we would like to think they made it, 'cause there was a boat smashed up on the beach. We would like to think the four of them got in that boat, made it to shore, got someplace, and were captured. And they're, you know, gonna come back." The SEAL and Air Force survivors continued their mission, but their boats flooded while evading a patrol boat, causing the mission to be aborted. Another SEAL mission on 24 October was also unsuccessful, due to harsh weather, resulting in little intelligence being gathered in advance of the impending intervention.

Alpha and Bravo companies of the 1st Battalion of the

Alpha and Bravo companies of the 1st Battalion of the

The last major special operation was a mission to rescue Governor-General Scoon from his mansion in Saint George, Grenada. The mission departed late at 05:30 on 25 October from Barbados, resulting in the Grenadian forces being already aware of the invasion and they guarded Scoon closely. The SEAL team entered the mansion without opposition, but

The last major special operation was a mission to rescue Governor-General Scoon from his mansion in Saint George, Grenada. The mission departed late at 05:30 on 25 October from Barbados, resulting in the Grenadian forces being already aware of the invasion and they guarded Scoon closely. The SEAL team entered the mansion without opposition, but

General Trobaugh of the 82nd Airborne Division had two goals on the second day: securing the perimeter around Point Salines Airport, and rescuing American students held in Grand Anse. The Army lacked undamaged helicopters after the losses on the first day and consequently had to delay the student rescue until they made contact with Marine forces.

General Trobaugh of the 82nd Airborne Division had two goals on the second day: securing the perimeter around Point Salines Airport, and rescuing American students held in Grand Anse. The Army lacked undamaged helicopters after the losses on the first day and consequently had to delay the student rescue until they made contact with Marine forces.

Early on the morning of 26 October, Cuban forces ambushed a patrol from the 2nd Battalion of the 325th Infantry Regiment near the village of Calliste. The American patrol suffered six wounded and two killed, including the commander of Company B, CPT Michael F. Ritz and squad leader SSG Gary L. Epps. Navy airstrikes and an artillery bombardment by 105mm howitzers targeting the main Cuban encampment eventually led to their surrender at 08:30. American forces pushed on to the village of Frequente, where they discovered a Cuban weapons cache reportedly sufficient to equip six battalions. Cuban forces ambushed a reconnaissance platoon mounted on gun-jeeps, but the jeeps returned fire, and a nearby infantry unit added mortar fire; the Cubans suffered four casualties with no American losses. Cuban resistance largely ended after these engagements.

Early on the morning of 26 October, Cuban forces ambushed a patrol from the 2nd Battalion of the 325th Infantry Regiment near the village of Calliste. The American patrol suffered six wounded and two killed, including the commander of Company B, CPT Michael F. Ritz and squad leader SSG Gary L. Epps. Navy airstrikes and an artillery bombardment by 105mm howitzers targeting the main Cuban encampment eventually led to their surrender at 08:30. American forces pushed on to the village of Frequente, where they discovered a Cuban weapons cache reportedly sufficient to equip six battalions. Cuban forces ambushed a reconnaissance platoon mounted on gun-jeeps, but the jeeps returned fire, and a nearby infantry unit added mortar fire; the Cubans suffered four casualties with no American losses. Cuban resistance largely ended after these engagements.

On the afternoon of 26 October, Rangers of the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment mounted Marine CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters to launch an air assault on the Grand Anse campus. The campus police offered light resistance before fleeing, wounding one Ranger, and one of the helicopters crashed on approach after its blade hit a palm tree. The Rangers evacuated the 233 American students by CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters, but the students informed them that there was a third campus with Americans at Prickly Bay. A squad of 11 Rangers was accidentally left behind; they departed on a rubber raft which was picked up by at 23:00.

On the afternoon of 26 October, Rangers of the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment mounted Marine CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters to launch an air assault on the Grand Anse campus. The campus police offered light resistance before fleeing, wounding one Ranger, and one of the helicopters crashed on approach after its blade hit a palm tree. The Rangers evacuated the 233 American students by CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters, but the students informed them that there was a third campus with Americans at Prickly Bay. A squad of 11 Rangers was accidentally left behind; they departed on a rubber raft which was picked up by at 23:00.

The Army had reports that PRA forces were amassing at the Calivigny Barracks, only five kilometers from the Point Salines airfield. They organized an air assault by the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment preceded by a preparatory bombardment by field howitzers (which mostly missed, their shells falling into the ocean), A-7s,

The Army had reports that PRA forces were amassing at the Calivigny Barracks, only five kilometers from the Point Salines airfield. They organized an air assault by the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment preceded by a preparatory bombardment by field howitzers (which mostly missed, their shells falling into the ocean), A-7s,

''

'' Medical students in Grenada, speaking to

Medical students in Grenada, speaking to

25 October is a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day, to commemorate the invasion.

25 October is a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day, to commemorate the invasion.

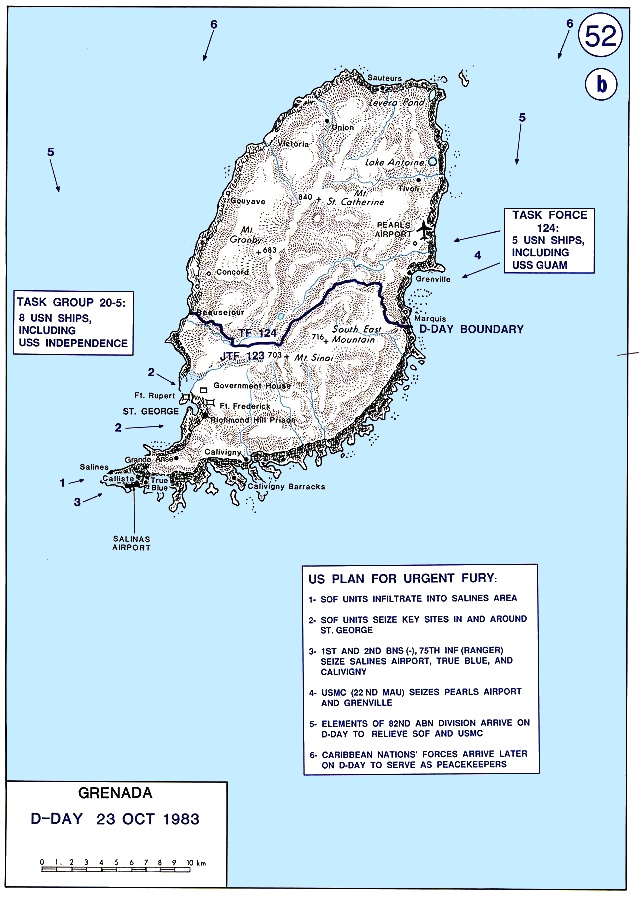

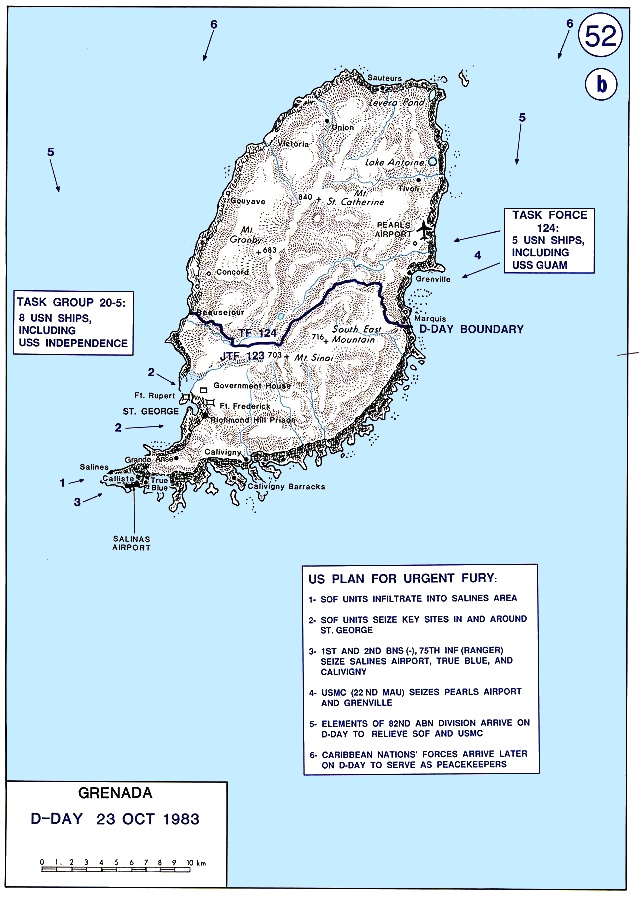

Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf, III, COMSECONDFLT, became Commander of Joint Task Force 120 (CJTF 120) and commanded units from the Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard from the MARG flagship USS ''Guam''. Rear Admiral Richard C. Berry (COMCRUDESGRU Eight) (Commander Task Group 20) supported the task force on the aircraft carrier USS ''Independence''. Commanding Officer USS Guam (Task Force 124) was assigned the mission of seizing Pearls Airport and the port of Grenville, and of neutralizing any opposing forces in the area. Simultaneously, Army Rangers in Task Force 123 would secure points at the southern end of the island, including the airfield under construction near Point Salines. The 82d Airborne Division (Task Force 121) were designated to follow and assume the security at Point Salines once it was seized by Task Force 123. Task Group 20.5, a carrier battle group built around USS ''Independence'', and Air Force elements would support the ground forces.

Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf, III, COMSECONDFLT, became Commander of Joint Task Force 120 (CJTF 120) and commanded units from the Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard from the MARG flagship USS ''Guam''. Rear Admiral Richard C. Berry (COMCRUDESGRU Eight) (Commander Task Group 20) supported the task force on the aircraft carrier USS ''Independence''. Commanding Officer USS Guam (Task Force 124) was assigned the mission of seizing Pearls Airport and the port of Grenville, and of neutralizing any opposing forces in the area. Simultaneously, Army Rangers in Task Force 123 would secure points at the southern end of the island, including the airfield under construction near Point Salines. The 82d Airborne Division (Task Force 121) were designated to follow and assume the security at Point Salines once it was seized by Task Force 123. Task Group 20.5, a carrier battle group built around USS ''Independence'', and Air Force elements would support the ground forces.

*

*

* 136th Tactical Airlift Wing, Texas Air National Guard – provided

* 136th Tactical Airlift Wing, Texas Air National Guard – provided

Grenada Documents, an Overview & Selection

DOD & State Dept, Sept 1984, 813 pages.

Grenada, A Preliminary Report

DOD & State

Joint Overview, Operation Urgent Fury

1 May 1985, 87 pages

Invasion of Grenada and Its Political Repercussions

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

��

Grenadian Revolution Archive

at marxists.org

The dream of a Black utopia

podcast from

''Grenada''

— a 1984 comic book about the invasion written by the CIA. {{Authority control 1983 in Grenada

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and a coalition

A coalition is formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political, military, or economic spaces.

Formation

According to ''A G ...

of Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

countries invaded the small island nation of Grenada

Grenada is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The southernmost of the Windward Islands, Grenada is directly south of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and about north of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and the So ...

, north of Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

, at dawn on 25 October 1983. Codenamed Operation Urgent Fury by the U.S. military, it resulted in military occupation within a few days. It was triggered by strife within the People's Revolutionary Government

The People's Revolutionary Government (PRG) was proclaimed on 13 March 1979 after the Marxist–Leninist New Jewel Movement overthrew the government of Grenada in a revolution, making Grenada the only socialist state within Commonwealth of Nati ...

, which led to the house arrest and execution of the previous leader and second Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of Grenada

Grenada is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The southernmost of the Windward Islands, Grenada is directly south of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and about north of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and the So ...

, Maurice Bishop

Maurice Rupert Bishop (29 May 1944 – 19 October 1983) was a Grenada, Grenadian revolutionary and the leader of the New Jewel Movement (NJM) – a Marxist–Leninist party that sought to prioritise socio-economic development, education and bla ...

, and to the establishment of the Revolutionary Military Council, with Hudson Austin

Hudson Austin (26 April 1938 – 24 September 2022) was a general in the People's Revolutionary Army of Grenada. After the killing of Maurice Bishop, he formed a military government with himself as chairman to rule Grenada.

History Early life ...

as chairman. Following the invasion there was an interim government appointed, and then general elections held in December 1984.

The invading force consisted of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

's 75th Ranger Regiment

The 75th Ranger Regiment, also known as the United States Army Rangers, Army Rangers, is the United States Army Special Operations Command's premier light infantry and direct-action raid force. The 75th Ranger Regiment is also part of Joint S ...

, the 82nd Airborne Division

The 82nd Airborne Division is an Airborne forces, airborne infantry division (military), division of the United States Army specializing in Paratrooper, parachute assault operations into hostile areasSof, Eric"82nd Airborne Division" ''Spec Ops ...

, and elements of the former Rapid Deployment Force

A rapid reaction force / rapid response force (RRF), quick reaction force / quick response force (QRF), immediate reaction force (IRF), rapid deployment force (RDF), or quick maneuver force (QMF) is a military or law enforcement unit capable of ...

, U.S. Marines, U.S. Army Delta Force, Navy SEAL

The United States Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) Teams, commonly known as Navy SEALs, are the United States Navy's primary special operations force and a component of the United States Naval Special Warfare Command. Among the SEALs' main funct ...

s, and a small group Air Force TACPs from the 21st TASS Shaw AFB ancillary forces, totaling 7,600 troops, together with Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

n forces and troops of the Regional Security System (RSS). The invaders quickly defeated Grenadian resistance after a low-altitude assault by the Rangers and 82nd Airborne at Point Salines Airport on the island's south end, and a Marine helicopter and amphibious landing at Pearls Airport on the north end. Austin's military government was deposed. An advisory council was designated by Sir Paul Scoon, Governor-General of Grenada

The governor-general of Grenada is the representative of the Grenadian monarch, currently King Charles III, in Grenada. The governor-general is appointed by the monarch on the recommendation of the prime minister of Grenada. The functions of t ...

, to administer the government until the 1984 elections.

The invasion date of 25 October is now a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in October and November in the United States, Canada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Germany. It is also observed in the Australian territory ...

, commemorating the freeing of several political prisoners who were subsequently elected to office. A truth and reconciliation commission

A truth commission, also known as a truth and reconciliation commission or truth and justice commission, is an official body tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by a government (or, depending on the circumstances, non-state ac ...

was launched in 2000 to re-examine some of the controversies of that tumultuous period in the 1980s; in particular, the commission made an unsuccessful attempt to locate the remains of Maurice Bishop's body, which had been disposed of at Austin's order and never found.

At the time, the invasion drew criticism from many countries. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

privately disapproved of the mission, in part because she was not consulted in advance and was given very short notice of the military operation, but she supported it in public. The United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

condemned it as "a flagrant violation of international law" on 2 November 1983, by a vote of 108 to 9.

The invasion exposed communication and coordination problems between the different branches of the U.S. military when operating together as a joint force. This triggered post-action investigations resulting in sweeping operational changes in the form of the Goldwater–Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act.

Background

In 1974, Sir Eric Gairy led Grenada to independence from theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, but his term in office was marred by civil unrest. Although his Grenada United Labour Party

The Grenada United Labour Party (GULP) is a political party in Grenada.

History

The party was founded by Eric Gairy in 1950. It contested the first elections held under universal suffrage in 1951, and won six of the eight seats. Nohlen, D (2005 ...

claimed victory in the general election of 1976, the opposition did not accept the result as legitimate. During his tenure, many Grenadians believed Gairy was personally responsible for the economic decline of the island and accused him of corruption. The civil unrest took the form of street violence between Gairy's private militia, the Mongoose Gang, and a militia organized by the communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

New Jewel Movement

The New Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education, and Liberation, or New JEWEL Movement (NJM), was a Marxist–Leninist vanguard party in the Caribbean island nation of Grenada that was led by Maurice Bishop.

Established in 1973, the NJM issued ...

(NJM) party.

On 13 March 1979, while Gairy was temporarily out of the country, Maurice Bishop

Maurice Rupert Bishop (29 May 1944 – 19 October 1983) was a Grenada, Grenadian revolutionary and the leader of the New Jewel Movement (NJM) – a Marxist–Leninist party that sought to prioritise socio-economic development, education and bla ...

and his NJM seized power in a nearly bloodless coup. He established the People's Revolutionary Government

The People's Revolutionary Government (PRG) was proclaimed on 13 March 1979 after the Marxist–Leninist New Jewel Movement overthrew the government of Grenada in a revolution, making Grenada the only socialist state within Commonwealth of Nati ...

, suspended the constitution, and detained several political prisoners. Bishop was a forceful speaker who introduced Marxist ideology to Grenadians while also appealing to Black Americans during the 1970s heyday of the Black Panther

A black panther is the Melanism, melanistic colour variant of the leopard (''Panthera pardus'') and the jaguar (''Panthera onca''). Black panthers of both species have excess black pigments, but their typical Rosette (zoology), rosettes are al ...

movement. After seizing power, Bishop attempted to implement the first Marxist-Leninist nation in the British Commonwealth. To lend itself an appearance of constitutional legitimacy, the new administration continued to recognize Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

as Queen of Grenada and Sir Paul Scoon as her viceregal representative.

Airport

The Bishop government began constructing the Point Salines International Airport with the help of theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, and other nations. The British government proposed the airport in 1954 when Grenada was still a British colony. Canadians

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

designed it, the British government underwrote it, and a London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

firm built it. The U.S. government accused Grenada of constructing facilities to aid a Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

- Cuban military buildup in the Caribbean. The accusation was based on the fact that the new airport's runway would be able to accommodate the largest Soviet aircraft, such as the An-12

The Antonov An-12 (Russian language, Russian: Антонов Ан-12; NATO reporting name: Cub) is a four-engined turboprop Cargo aircraft, transport aircraft designed in the Soviet Union. It is the military version of the Antonov An-10 and has ...

, An-22, and An-124. Such a facility, according to the U.S., would enhance the Soviet and Cuban transportation of weapons to Central American insurgents and expand Soviet regional influence. Bishop's government claimed that the airport was built to handle commercial aircraft carrying tourists, pointing out that such jets could not land at Pearls Airport with its runway on the island's north end, and that Pearls could not be expanded because its runway abutted a mountain on one side and the ocean on the other.

In 1983, Representative Ron Dellums

Ronald Vernie Dellums (November 24, 1935 – July 30, 2018) was an American politician who served as Mayor of Oakland from 2007 to 2011. He had previously served thirteen terms as a Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California ...

( D- CA) traveled to Grenada on a fact-finding mission, having been invited by Prime Minister Bishop. Dellums described his findings before Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

:

Based on my personal observations, discussion, and analysis of the new international airport under construction in Grenada, it is my conclusion that this project is specifically now and has always been for the purpose of economic development and is not for military use.... It is my thought that it is absurd, patronizing, and totally unwarranted for the United States government to charge that this airport poses a military threat to the United States' national security.In March 1983, President Reagan began issuing warnings about the danger to the United States and Caribbean nations if the Soviet-Cuban militarization of that region was allowed to proceed. He pointed to the excessively long airport runway being built and referenced intelligence reports showing increased Soviet interest in the island. He said the runway, along with the airport's numerous fuel storage tanks, were unnecessary for commercial flights and that the evidence suggested the airport would become a Cuban-Soviet forward military airbase. Meanwhile, an internal power struggle was brewing in Grenada over Bishop's leadership performance. In September 1983 at a Central Committee party meeting, he was pressured into sharing power with Deputy Prime Minister

Bernard Coard

Winston Bernard Coard (born 10 August 1944) is a Grenadian politician who served as Deputy Prime Minister in the People's Revolutionary Government (PRG) of the New Jewel Movement. In 1983, Coard launched a coup within the PRG and briefly too ...

. Bishop initially agreed to the joint leadership proposal, but later balked at the idea, which brought matters to a crisis.

October 1983

On the evening of 13 October 1983, the Coard faction of the Central Committee, in conjunction with the People’s Revolutionary Army, placed Prime Minister Bishop and several of his allies under house arrest. On 19 October, after Bishop's secret detention became widely known, he was freed by a large crowd of supporters, estimated between 15,000 and 30,000. He led the crowd to a relatively unguarded Fort Rupert (later renamed Fort George) which they soon occupied. At nearby Fort Frederick, Coard had gathered nine Central Committee members and sizable factions of the military. As one journalist writes, "What happened next, and on whose orders, is still a controversy." But a mass of troops in armored personnel carriers, under the supervision of Lt. Colonel Ewart Layne, departed Fort Frederick for Fort Rupert to, as Layne described it, "recapture the fort and restore order." After surrendering to the superior force, Bishop and seven leaders loyal to him were lined up against a wall in Fort Rupert's courtyard and executed by a firing squad. The army underHudson Austin

Hudson Austin (26 April 1938 – 24 September 2022) was a general in the People's Revolutionary Army of Grenada. After the killing of Maurice Bishop, he formed a military government with himself as chairman to rule Grenada.

History Early life ...

then stepped in and formed a military council to rule the country, and placed Sir Paul Scoon under house arrest in Government House. The army instituted a strict four-day curfew during which anyone seen on the streets would be shot on sight.

Within only a few days of these events in Grenada, the Reagan administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following his landslide victory over ...

mounted a U.S.-led military intervention

Interventionism, in international politics, is the interference of a state or group of states into the domestic affairs of another state for the purposes of coercing that state to do something or refrain from doing something. The intervention ca ...

following a formal appeal for help from the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS; French: ''Organisation des États de la Caraïbe orientale'', OECO) is an inter-governmental organisation dedicated to economic harmonisation and integration, protection of human and legal ...

, which had received a covert request for help from Paul Scoon (though he put off signing the official letter of invitation until 26 October). Among the key invasion planners were Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and his senior military assistant Colin Powell

Colin Luther Powell ( ; – ) was an Americans, American diplomat, and army officer who was the 65th United States secretary of state from 2001 to 2005. He was the first African-American to hold the office. He was the 15th National Security ...

. Regarding the speed with which the invasion commenced, it was said the U.S. had been conducting mock invasions of Grenada since 1981: "These exercises, part of Ocean Venture '81 and known as Operation Amber and the Amberdines, involved air and amphibious assaults on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques. According to the plans for these maneuvers, 'Amber' was considered a hypothetical island in the Eastern Caribbean which had engaged in anti-democratic revolutionary activities."

Reagan stated that he felt compelled to act due to "concerns over the 600 U.S. medical students on the island" and fears of a repeat of the Iran hostage crisis

The Iran hostage crisis () began on November 4, 1979, when 66 Americans, including diplomats and other civilian personnel, were taken hostage at the Embassy of the United States in Tehran, with 52 of them being held until January 20, 1981. Th ...

, which ended less than three years earlier. Future U.S. Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger, who was then serving as Reagan's Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs

The under secretary of state for political affairs is currently the fourth-ranking position in the United States Department of State, after the United States Secretary of State, secretary, the United States Deputy Secretary of State, deputy secre ...

, later admitted that the prime motivation for the intervention was to "get rid" of the coup leader Hudson Austin, and that the students were a pretext. Although the invasion occurred after the execution of Prime Minister Bishop, the remaining Grenadian ruling party members were still committed to Bishop's Marxist ideology. Reagan said he viewed these factors, alongside the party's growing connection to Fidel Castro, as a threat to democracy.

The

The Organization of Eastern Caribbean States

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS; French: ''Organisation des États de la Caraïbe orientale'', OECO) is an inter-governmental organisation dedicated to economic harmonisation and integration, protection of human and legal ...

(OECS), Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

, and Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

all appealed to the United States for assistance. For safety reasons, Paul Scoon had requested the invasion through secret diplomatic channels, using the reserve power

In a parliamentary or semi-presidential system of government, a reserve power, also known as discretionary power, is a power that may be exercised by the head of state (or their representative) without the approval of another branch or part of th ...

s vested in the Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, parti ...

. On 22 October 1983, the Deputy High Commissioner in Bridgetown

Bridgetown (UN/LOCODE: BB BGI) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Barbados. Formerly The Town of Saint Michael, the Greater Bridgetown area is located within the Parishes of Barbados, parish of Saint Michael, Barbados, Saint Mic ...

, Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

, visited Grenada and reported that Scoon was well and "did not request military intervention, either directly or indirectly". However, on the day after the invasion, Prime Minister of Dominica

The prime minister of Dominica is the head of government in the Commonwealth of Dominica. Nominally, the position was created on November 3, 1978, when Dominica gained independence from the United Kingdom. Hitherto, the position existed de facto ...

Eugenia Charles

Dame Mary Eugenia Charles (15 May 1919 – 6 September 2005) was a Dominican politician who was Prime Minister of Dominica from 21 July 1980 until 14 June 1995. The first female lawyer in Dominica, she was Dominica's first, and to date only, fem ...

stated the request had come from Scoon, through the OECS, and, in his 2003 autobiography, ''Survival for Service'', Scoon maintains he asked the visiting British diplomat to pass along "an oral request" for outside military intervention at this meeting.

On 25 October, the combined forces of the United States and the Regional Security System (RSS) based in Barbados invaded Grenada in an operation codenamed ''Operation Urgent Fury''. The United States insisted this was being done at the request of Barbados' Prime Minister Tom Adams and Dominica's Prime Minister Eugenia Charles. The invasion was sharply criticized by the governments in Canada, Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago, officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, is the southernmost island country in the Caribbean, comprising the main islands of Trinidad and Tobago, along with several List of islands of Trinidad and Tobago, smaller i ...

, and the United Kingdom. By a vote of 108 to 9, with 27 abstentions, the United Nations General Assembly condemned it as "a flagrant violation of international law."

First day of the invasion

H-hour for the invasion was set for 05:00 on 25 October 1983. U.S. troops deployed for Grenada by helicopter from

H-hour for the invasion was set for 05:00 on 25 October 1983. U.S. troops deployed for Grenada by helicopter from Grantley Adams International Airport

Grantley Adams International Airport (GAIA) is an international airport at Seawell, Christ Church, Barbados, Christ Church, Barbados, serving as the country's only port of entry by air.

The airport is the only designated port of entry for ...

on Barbados before daybreak. Nearly simultaneously, American paratroopers arrived directly by transport aircraft from bases in the eastern United States, and U.S. Marines were airlifted to the island from USS ''Guam'' offshore. It was the largest American military action since the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf III, Commander of the Second Fleet, was the overall commander of American forces, designated Joint Task Force 120, which included elements of each military service and multiple special operations units. Fighting continued for several days and the total number of American troops reached some 7,000 along with 300 troops from the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS or OEA; ; ; ) is an international organization founded on 30 April 1948 to promote cooperation among its member states within the Americas.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, the OAS is ...

, commanded by Brigadier Rudyard Lewis of Barbados.

The main objectives on the first day were for the 75th Ranger Regiment

The 75th Ranger Regiment, also known as the United States Army Rangers, Army Rangers, is the United States Army Special Operations Command's premier light infantry and direct-action raid force. The 75th Ranger Regiment is also part of Joint S ...

to capture Point Salines International Airport in order for the 82nd Airborne Division

The 82nd Airborne Division is an Airborne forces, airborne infantry division (military), division of the United States Army specializing in Paratrooper, parachute assault operations into hostile areasSof, Eric"82nd Airborne Division" ''Spec Ops ...

to land reinforcements on the island; the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment to capture Pearls Airport; and other forces to rescue the American students at the True Blue Campus of St. George's University

St. George's University is a private for-profit Medical school in the Caribbean, medical school and international university in Grenada, West Indies, offering degrees in medicine, veterinary medicine, public health, the health sciences, nursing ...

. In addition, a number of special operations missions were undertaken by Army Delta Force operatives and Navy SEALs to obtain intelligence and secure key individuals and equipment. Many of these missions were plagued by inadequate intelligence and planning; the American troops used tourist maps with military grids superimposed on them.

Defending forces

People's Revolutionary Army

The invading forces encountered about 1,500 Grenadian soldiers of the People's Revolutionary Army (PRA) manning defensive positions. The PRA troops were for the most part equipped with light weapons, mostly Kalashnikov-pattern automatic rifles of Sovietbloc

Bloc may refer to:

Government and politics

* Political bloc, a coalition of political parties

* Trade bloc, a type of intergovernmental agreement

* Voting bloc, a group of voters voting together

* Black bloc, a tactic used by protesters who wear ...

origin and semiautomatic Czech Vz. 52 carbines, along with smaller numbers of obsolete SKS carbines and PPSh-41

The PPSh-41 () is a selective-fire, open-bolt, blowback submachine gun that fires the 7.62×25mm Tokarev round. It was designed by Georgy Shpagin of the Soviet Union to be a cheaper and simplified alternative to the PPD-40.

The PPSh-41 saw ...

submachine guns. They had few heavy weapons and no modern air defense systems. The PRA was not regarded as a serious military threat by the U.S., which was more concerned by the possibility that Cuba would send a large expeditionary force to intervene on behalf of its erstwhile ally.

The PRA did possess eight BTR-60PB

The BTR-60 is the first vehicle in a series of Soviet eight-wheeled armoured personnel carriers (APCs). It was developed in the late 1950s as a replacement for the BTR-152 and was seen in public for the first time in 1961. BTR stands for ''bronet ...

armored personnel carriers and two BRDM-2

The BRDM-2 (''Boyevaya Razvedyvatelnaya Dozornaya Mashina'', Боевая Разведывательная Дозорная Машина, literally "Combat Reconnaissance/Patrol Vehicle") is an amphibious armoured scout car designed and developed ...

armored cars delivered as military aid from the Soviet Union in February 1981, but no tanks.''Grenada 1983'' by Lee E. Russell and M. Albert Mendez, 1985 Osprey Publishing Ltd., pp. 28–48.

Cuban forces in Grenada

The Cuban military presence in Grenada was more complex than initially evaluated by the U.S. Most of the Cuban civilian expatriates present were also military reservists.Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

described the Cuban construction crews in Grenada as "workers and soldiers at the same time", claiming the dual nature of their role was consistent with Cuba's "citizen soldier" tradition. At the time of the invasion, there were an estimated 784 Cuban nationals on the island. About 630 of the Cuban nationals listed their occupations as construction workers, another 64 as military personnel, and 18 as dependents. The remainder were medical staff or teachers.

Colonel Pedro Tortoló Comas was the highest-ranking Cuban military officer in Grenada in 1983, and he later stated that he issued small arms and ammunition to the construction workers for the purpose of self-defense during the invasion, which may have further blurred the line between their status as civilians and combatants. They were also expressly forbidden to surrender to U.S. military forces if approached. The regular Cuban military personnel on the island were serving as advisers to the PRA at the time. Cuban advisers and instructors deployed with overseas military missions were not confined to non-combat and technical support roles; if the units to which they were attached participated in an engagement, they were expected to fight alongside their foreign counterparts.

Bob Woodward

Robert Upshur Woodward (born March 26, 1943) is an American investigative journalist. He started working for ''The Washington Post'' as a reporter in 1971 and now holds the honorific title of associate editor though the Post no longer employs ...

wrote in ''Veil'' that captured "military advisors" from socialist countries, including Cuba, were actually accredited diplomats and their dependents. He claimed that none of them took any actual part in the fighting. The U.S. government asserted that most of the supposed Cuban civilian technicians on Grenada were in fact military personnel, including special forces and combat engineers. A summary of the Cuban presence in ''The Engineer'', the official periodical of the U.S. Army Engineer School

The United States Army Engineer School (USAES) is located at Fort Leonard Wood (military base), Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. It was founded as a School of Engineering by General Headquarters Orders, Valley Forge on 9 June 1778. The U.S. Army Engin ...

, noted that "resistance from these well-armed military and paramilitary forces belied claims that they were simply construction crews."

Navy SEAL reconnaissance missions

U.S. Special Operations Forces were deployed to Grenada beginning on 23 October, before the 25 October invasion. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team 6 and Air Force combat controllers were air-dropped at sea to perform a reconnaissance mission on Point Salines. The helicopter drop went wrong; four SEALs were lost at sea and their bodies never recovered, causing most people to suspect they had drowned. The four SEALs were Machinist Mate 1st Class Kenneth J. Butcher, Quartermaster 1st Class Kevin E. Lundberg, Hull Technician 1st Class Stephen L. Morris, and Senior Chief Engineman Robert R. Schamberger. In an interview conducted by Bill Salisbury and published on 4 October 1990, Kenneth Butcher's widow claimed that she had gone to Grenada hoping that her husband had survived. She said, "There was this fisherman who said he saw four guys in wetsuits come out of the water, and then two days later he saw four bodies being thrown into the water. So we would like to think they made it, 'cause there was a boat smashed up on the beach. We would like to think the four of them got in that boat, made it to shore, got someplace, and were captured. And they're, you know, gonna come back." The SEAL and Air Force survivors continued their mission, but their boats flooded while evading a patrol boat, causing the mission to be aborted. Another SEAL mission on 24 October was also unsuccessful, due to harsh weather, resulting in little intelligence being gathered in advance of the impending intervention.

U.S. Special Operations Forces were deployed to Grenada beginning on 23 October, before the 25 October invasion. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team 6 and Air Force combat controllers were air-dropped at sea to perform a reconnaissance mission on Point Salines. The helicopter drop went wrong; four SEALs were lost at sea and their bodies never recovered, causing most people to suspect they had drowned. The four SEALs were Machinist Mate 1st Class Kenneth J. Butcher, Quartermaster 1st Class Kevin E. Lundberg, Hull Technician 1st Class Stephen L. Morris, and Senior Chief Engineman Robert R. Schamberger. In an interview conducted by Bill Salisbury and published on 4 October 1990, Kenneth Butcher's widow claimed that she had gone to Grenada hoping that her husband had survived. She said, "There was this fisherman who said he saw four guys in wetsuits come out of the water, and then two days later he saw four bodies being thrown into the water. So we would like to think they made it, 'cause there was a boat smashed up on the beach. We would like to think the four of them got in that boat, made it to shore, got someplace, and were captured. And they're, you know, gonna come back." The SEAL and Air Force survivors continued their mission, but their boats flooded while evading a patrol boat, causing the mission to be aborted. Another SEAL mission on 24 October was also unsuccessful, due to harsh weather, resulting in little intelligence being gathered in advance of the impending intervention.

Air assault on Point Salines

Alpha and Bravo companies of the 1st Battalion of the

Alpha and Bravo companies of the 1st Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment

The 75th Ranger Regiment, also known as the United States Army Rangers, Army Rangers, is the United States Army Special Operations Command's premier light infantry and direct-action raid force. The 75th Ranger Regiment is also part of Joint S ...

embarked on C-130

The Lockheed C-130 Hercules is an American four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft designed and built by Lockheed Corporation, Lockheed (now Lockheed Martin). Capable of using unprepared runways for takeoffs and landings, the C-130 w ...

s at Hunter Army Airfield at midnight on 25 October to perform an air assault landing on Point Salines Airport, intending to land at the airport and then disembark. The Rangers had to switch abruptly to a parachute landing when they learned mid-flight that the runway was obstructed. The air drop began at 05:30 on 25 October in the face of moderate resistance from ZU-23

The ZU-23-2, also known as ZU-23, is a Soviet towed 23×152mm anti-aircraft twin-barreled autocannon. ZU stands for ''Zenitnaya Ustanovka'' (Russian: Зенитная Установка) – anti-aircraft mount. The GRAU index is 2A13.

Developm ...

anti-aircraft guns and several BTR-60 armored personnel carriers

An armoured personnel carrier (APC) is a broad type of armoured military vehicle designed to transport personnel and equipment in combat zones. Since World War I, APCs have become a very common piece of military equipment around the world.

Acc ...

(APCs), which were knocked out by M67 recoilless rifle fire. AC-130

The Lockheed AC-130 gunship is a heavily armed, long-endurance, attack aircraft, ground-attack variant of the C-130 Hercules transport, fixed-wing aircraft. It carries a wide array of ground-attack weapons that are integrated with sensors, nav ...

gunships provided support for the landing. Cuban construction vehicles were commandeered to help clear the airfield, and one even used to provide mobile cover for the Rangers as they moved to seize the heights surrounding the airfield.

The Rangers cleared the airstrip of obstructions by 10:00, and transport planes were able to land and unload additional reinforcements, including M151 Jeeps and members of the Caribbean Peace Force assigned to guard the perimeter and detainees. Starting at 14:00, units began landing at Point Salines from the 82nd Airborne Division

The 82nd Airborne Division is an Airborne forces, airborne infantry division (military), division of the United States Army specializing in Paratrooper, parachute assault operations into hostile areasSof, Eric"82nd Airborne Division" ''Spec Ops ...

under Edward Trobaugh

Edward L. Trobaugh (November 7, 1932 – May 20, 2024) was a United States Army Major General.

Early life and education

Trobaugh graduated from Kokomo High School in 1950.

Career

Trobaugh attended West Point graduating in 1955 and was commiss ...

, including battalions of the 325th Infantry Regiment. At 15:30, three BTR-60s of the Grenadian Army Motorized Company counter-attacked, but the Americans repelled them with recoilless rifles and an AC-130.

The Rangers fanned out and secured the surrounding area, negotiating the surrender of over 100 Cubans in an aviation hangar. However, a Jeep-mounted Ranger patrol became lost searching for True Blue Campus and was ambushed, with four killed. The Rangers eventually secured True Blue campus and its students, where they found only 140 students and were told that more were at another campus in Grand Anse, northeast of True Blue. In all, the Rangers lost five men on the first day, but succeeded in securing Point Salines and the surrounding area.

Capture of Pearls Airport

A platoon of Navy SEALs from SEAL Team 4 under Lieutenant Mike Walsh approached the beach near Pearls Airport around midnight on 25 October after evading patrol boats and overcoming stormy weather. They found that the beach was lightly defended but unsuitable for an amphibious landing. The 2nd Battalion of the 8th Marine Regiment then landed south of Pearls Airport using CH-46 Sea Knight and CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters at 05:30 on 25 October; they captured Pearls Airport, encountering only light resistance, including aDShK

The DShK M1938 (Cyrillic: ДШК, for ) is a Soviet heavy machine gun. The weapon may be vehicle mounted or used on a tripod or wheeled carriage as a heavy infantry machine gun. The DShK's name is derived from its original designer, Vasily Degtya ...

machine gun which a Marine AH-1 Cobra

The Bell AH-1 Cobra is a single-engined attack helicopter developed and manufactured by the American rotorcraft manufacturer Bell Helicopter. A member of the prolific Huey family, the AH-1 is also referred to as the HueyCobra or Snake.

The A ...

destroyed.

Raid on Radio Free Grenada

UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters delivered SEAL Team 6 operators in the early morning of 25 October to Radio Free Grenada with the purpose of using the radio station forpsychological operations

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), has been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations (MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and Min ...

. They captured the station unopposed and destroyed the radio transmitter. However, they were attacked by Grenadian forces in cars and an armored personnel carrier (APC), which forced the lightly-armed SEALs to cut open a fence and retreat into the ocean while receiving fire from the APC. The SEALs then reportedly swam to USS ''Caron''. They swam toward the open sea, and were picked up several hours later after being spotted by a reconnaissance plane.

Raids on Fort Rupert and Richmond Hill Prison

On 25 October,Delta Force

The 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment–Delta (1st SFOD-D), also known as Delta Force, Combat Applications Group (CAG), or within Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) as Task Force Green, is a Special operation forces, special operat ...

and C Company of the 75th Ranger Regiment

The 75th Ranger Regiment, also known as the United States Army Rangers, Army Rangers, is the United States Army Special Operations Command's premier light infantry and direct-action raid force. The 75th Ranger Regiment is also part of Joint S ...

embarked in UH-60

The Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk is a four-blade, twin-engine, medium-lift military utility helicopter manufactured by Sikorsky Aircraft. Sikorsky submitted a design for the United States Army's Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS) ...

and MH-6 Little Bird

The Boeing MH-6M Little Bird (nicknamed the Killer Egg) and its attack helicopter, attack variant, the AH-6, are light Helicopter, helicopters used for special operations in the United States Army. Originally based on a modified OH-6 Cayuse, OH ...

helicopters of Task Force 160 to capture Fort Rupert (now known as Fort George), where they believed the Revolutionary Council leaders lived, and Richmond Hill Prison, where political prisoners were being held. The raid on Richmond Hill Prison lacked vital intelligence, leaving the attackers unaware of the presence of several anti-aircraft guns and steep hilly terrain that left no room for helicopter landings. Anti-aircraft fire wounded passengers and crew and forced one UH-60 helicopter to crash land, causing another helicopter to land next to it to protect the survivors. One pilot was killed, and the Delta Force operators had to be relieved by a Navy Sea King helicopter. The raid on Fort Rupert, however, was successful in capturing several leaders of the People's Revolutionary Government.

Mission to rescue Governor-General Scoon

BTR-60

The BTR-60 is the first vehicle in a series of Soviet Union, Soviet eight-wheeled armoured personnel carriers (APCs). It was developed in the late 1950s as a replacement for the BTR-152 and was seen in public for the first time in 1961. BTR (vehi ...

armored personnel carriers counter-attacked and trapped the SEALs and governor inside. AC-130

The Lockheed AC-130 gunship is a heavily armed, long-endurance, attack aircraft, ground-attack variant of the C-130 Hercules transport, fixed-wing aircraft. It carries a wide array of ground-attack weapons that are integrated with sensors, nav ...

gunships, A-7 Corsair strike planes, and AH-1 Cobra

The Bell AH-1 Cobra is a single-engined attack helicopter developed and manufactured by the American rotorcraft manufacturer Bell Helicopter. A member of the prolific Huey family, the AH-1 is also referred to as the HueyCobra or Snake.

The A ...

attack helicopters were called in to support the besieged SEALs, but they remained trapped for the next 24 hours.

At 19:00 on 25 October, 250 marines from G Company of the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment landed at Grand Mal Bay equipped with amphibious assault vehicles and four M60 Patton tanks; they relieved the Navy SEALs the following morning, allowing Governor Scoon, his wife, and nine aides to be safely evacuated at 10:00 that day. The Marine tank crews continued advancing in the face of sporadic resistance, knocking out a BRDM-2 armored car. G Company subsequently defeated and overwhelmed the Grenadian defenders at Fort Frederick.

Airstrikes

Navy A-7 Corsairs and MarineAH-1 Cobra

The Bell AH-1 Cobra is a single-engined attack helicopter developed and manufactured by the American rotorcraft manufacturer Bell Helicopter. A member of the prolific Huey family, the AH-1 is also referred to as the HueyCobra or Snake.

The A ...

attack helicopters made airstrikes against Fort Rupert and Fort Frederick. An A-7 raid on Fort Frederick targeting anti-aircraft guns hit a nearby mental hospital, killing 18 civilians. Two Marine AH-1T Cobras and a UH-60 Blackhawk were shot down in a raid against Fort Frederick, resulting in five casualties.

Second day of the invasion

General Trobaugh of the 82nd Airborne Division had two goals on the second day: securing the perimeter around Point Salines Airport, and rescuing American students held in Grand Anse. The Army lacked undamaged helicopters after the losses on the first day and consequently had to delay the student rescue until they made contact with Marine forces.

General Trobaugh of the 82nd Airborne Division had two goals on the second day: securing the perimeter around Point Salines Airport, and rescuing American students held in Grand Anse. The Army lacked undamaged helicopters after the losses on the first day and consequently had to delay the student rescue until they made contact with Marine forces.

Morning ambushes

Early on the morning of 26 October, Cuban forces ambushed a patrol from the 2nd Battalion of the 325th Infantry Regiment near the village of Calliste. The American patrol suffered six wounded and two killed, including the commander of Company B, CPT Michael F. Ritz and squad leader SSG Gary L. Epps. Navy airstrikes and an artillery bombardment by 105mm howitzers targeting the main Cuban encampment eventually led to their surrender at 08:30. American forces pushed on to the village of Frequente, where they discovered a Cuban weapons cache reportedly sufficient to equip six battalions. Cuban forces ambushed a reconnaissance platoon mounted on gun-jeeps, but the jeeps returned fire, and a nearby infantry unit added mortar fire; the Cubans suffered four casualties with no American losses. Cuban resistance largely ended after these engagements.

Early on the morning of 26 October, Cuban forces ambushed a patrol from the 2nd Battalion of the 325th Infantry Regiment near the village of Calliste. The American patrol suffered six wounded and two killed, including the commander of Company B, CPT Michael F. Ritz and squad leader SSG Gary L. Epps. Navy airstrikes and an artillery bombardment by 105mm howitzers targeting the main Cuban encampment eventually led to their surrender at 08:30. American forces pushed on to the village of Frequente, where they discovered a Cuban weapons cache reportedly sufficient to equip six battalions. Cuban forces ambushed a reconnaissance platoon mounted on gun-jeeps, but the jeeps returned fire, and a nearby infantry unit added mortar fire; the Cubans suffered four casualties with no American losses. Cuban resistance largely ended after these engagements.

Rescue at Grand Anse

Third day of the invasion and after

By 27 October, organized resistance was rapidly diminishing, but the American forces did not yet realize this. The 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines continued advancing along the coast and capturing additional towns, meeting little resistance, although one patrol did encounter a singleBTR-60

The BTR-60 is the first vehicle in a series of Soviet Union, Soviet eight-wheeled armoured personnel carriers (APCs). It was developed in the late 1950s as a replacement for the BTR-152 and was seen in public for the first time in 1961. BTR (vehi ...

during the night, dispatching it with a M72 LAW

The M72 LAW (light anti-tank weapon, also referred to as the light anti-armor weapon or LAW as well as LAWS: light anti-armor weapons system) is a portable one-shot unguided anti-tank weapon.

In early 1963, the M72 LAW was adopted by the U.S. ...

. The 325th Infantry Regiment advanced toward the capital of Saint George, capturing Grand Anse and discovering 200 American students whom they had missed the first day. They continued to the town of Ruth Howard and Saint George, meeting only scattered resistance. An air-naval gunfire liaison team called in an A-7 airstrike and accidentally hit the command post of the 2nd Brigade, wounding 17 troops, one of whom died.

The Army had reports that PRA forces were amassing at the Calivigny Barracks, only five kilometers from the Point Salines airfield. They organized an air assault by the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment preceded by a preparatory bombardment by field howitzers (which mostly missed, their shells falling into the ocean), A-7s,

The Army had reports that PRA forces were amassing at the Calivigny Barracks, only five kilometers from the Point Salines airfield. They organized an air assault by the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment preceded by a preparatory bombardment by field howitzers (which mostly missed, their shells falling into the ocean), A-7s, AC-130

The Lockheed AC-130 gunship is a heavily armed, long-endurance, attack aircraft, ground-attack variant of the C-130 Hercules transport, fixed-wing aircraft. It carries a wide array of ground-attack weapons that are integrated with sensors, nav ...

s, and USS ''Caron''. However, the Blackhawk helicopters began dropping off troops near the barracks but they approached too fast. One of them crash landed and the two behind it collided with it, killing three and wounding four. The barracks were deserted.

In the following days, resistance ended entirely and the Army and Marines spread across the island, arresting PRA officials, seizing caches of weapons, and seeing to the repatriation of Cuban engineers. On 1 November, two companies from the 2/8 Marines made a combined sea and helicopter landing on the island of Carriacou

Carriacou ( ) is an island of the Grenadine Islands. It is a part of the nation of Grenada and is located in the south-eastern Caribbean Sea, northeast of the island of Grenada and the north coast of South America. The name is derived from the ...

northeast of Grenada. The 19 Grenadian soldiers defending the island surrendered without a fight. This was the last military action of the campaign.

Outcome

It was confirmed Scoon had been in contact withQueen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

ahead of the invasion; however, Queen Elizabeth's office denied knowledge of any request for military action and the Queen was "extremely upset" by the invasion of one of her realms. The only document signed by the Governor-General and asking for military assistance was dated after the invasion, which fueled speculation that the United States had used Scoon as an excuse for its incursion into Grenada.

Official U.S. sources state that some of the opponents were well-prepared and well-positioned and put up stubborn resistance, to the extent that the Americans called in two battalions of reinforcements on the evening of 26 October. The total naval and air superiority of the American forces had overwhelmed the defenders. Nearly 8,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines had participated in Operation Urgent Fury, along with 353 Caribbean allies from the Caribbean Peace Forces. The final U.S. report claims 19 killed and 116 wounded; the Cubans to have had 25 killed, 59 wounded and 638 "combatants" captured; the Grenadians to have suffered 45 killed and 358 wounded. At least 24 civilians were also killed, 18 of whom died in the accidental bombing of a Grenadian mental hospital. The U.S. troops also destroyed a significant amount of Grenada's military hardware, including six BTR-60

The BTR-60 is the first vehicle in a series of Soviet Union, Soviet eight-wheeled armoured personnel carriers (APCs). It was developed in the late 1950s as a replacement for the BTR-152 and was seen in public for the first time in 1961. BTR (vehi ...

APCs and a BRDM-2

The BRDM-2 (''Boyevaya Razvedyvatelnaya Dozornaya Mashina'', Боевая Разведывательная Дозорная Машина, literally "Combat Reconnaissance/Patrol Vehicle") is an amphibious armoured scout car designed and developed ...

armored car. A second BRDM-2

The BRDM-2 (''Boyevaya Razvedyvatelnaya Dozornaya Mashina'', Боевая Разведывательная Дозорная Машина, literally "Combat Reconnaissance/Patrol Vehicle") is an amphibious armoured scout car designed and developed ...

armored car was impounded and shipped back to Marine Corps Base Quantico

Marine Corps Base Quantico (commonly abbreviated MCB Quantico) is a United States Marine Corps installation located near Triangle, Virginia, covering nearly of southern Prince William County, Virginia, northern Stafford County, and southe ...

for inspection.

Legality of the invasion

The U.S. government defended its invasion of Grenada as an action to protect American citizens living on the island, including medical students, and asserted it had been carried out at the request of the Governor-General. Deputy Secretary of State Kenneth W. Dam said that action was necessary to "resolve" what Article 28 of the charter of theOrganization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS or OEA; ; ; ) is an international organization founded on 30 April 1948 to promote cooperation among its member states within the Americas.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, the OAS is ...

(O.A.S.) refers to as "a situation that might endanger the peace". He added that the OAS charter and the UN charter both "recognize the competence of regional security bodies in ensuring regional peace and stability", referring to the decision by the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS; French: ''Organisation des États de la Caraïbe orientale'', OECO) is an inter-governmental organisation dedicated to economic harmonisation and integration, protection of human and legal ...

to approve the invasion.

The UN Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

prohibits the use of force by member states except in cases of self-defense or when specifically authorized by the UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

. The UN Security Council had not authorized this invasion. Similarly, the United Nations General Assembly adopted General Assembly Resolution 38/7 by a vote of 108 to 9 with 27 abstentions, which "deeply deplores the armed intervention in Grenada, which constitutes a flagrant violation of international law". A similar resolution in the United Nations Security Council received widespread support but was vetoed by the United States.

Reaction in the United States

''

''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine described the invasion as having "broad popular support". A congressional study group concluded that the invasion had been justified, as most members felt that American students at the university near a contested runway could have been taken hostage as American diplomats in Iran had been four years previously. The group's report caused House Speaker Tip O'Neill

Thomas Phillip "Tip" O'Neill Jr. (December 9, 1912 – January 5, 1994) was an American Democratic Party politician from Massachusetts who served as the 47th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1977 to 1987, the third-l ...

to change his position on the issue from opposition to support.

However, some members of the study group dissented from its findings. Congressman Louis Stokes

Louis Stokes (February 23, 1925 – August 18, 2015) was an American attorney, civil rights pioneer and politician. He served 15 terms in the United States House of Representatives – representing the east side of Cleveland – and was the firs ...

(D- OH) stated: "Not a single American child nor single American national was in any way placed in danger or placed in a hostage situation prior to the invasion". The Congressional Black Caucus

The Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) is made up of Black members of the United States Congress. Representative Yvette Clarke from New York, the current chairperson, succeeded Steven Horsford from Nevada in 2025. Although most members belong ...

denounced the invasion, and seven Democratic congressmen introduced an unsuccessful resolution to impeach President Reagan, led by Ted Weiss (D- NY).

Medical students in Grenada, speaking to

Medical students in Grenada, speaking to Ted Koppel

Edward James Martin Koppel (born February 8, 1940) is an American broadcast Journalism, journalist, best known as the News presenter, anchor for ''Nightline'', from the program's inception in 1980 until 2005.

Before ''Nightline'', he spent 20 y ...

on the 25 October 1983 edition of his newscast ''Nightline

''Nightline'' (or ''ABC News Nightline'') is ABC News (United States), ABC News' Late night television in the United States, late-night television news program broadcast on American Broadcasting Company, ABC in the United States with a franchis ...

'', stated that they were safe and did not feel their lives were in peril. The next evening, medical students told Koppel how grateful they were for the Army Rangers and the invasion which probably saved their lives. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

officials had assured the students they would be able to complete their medical school education in the United States.

An anti-war march attended by over 50,000 people, including Burlington, Vermont

Burlington, officially the City of Burlington, is the List of municipalities in Vermont, most populous city in the U.S. state of Vermont and the county seat, seat of Chittenden County, Vermont, Chittenden County. It is located south of the Can ...

Mayor Bernie Sanders

Bernard Sanders (born September8, 1941) is an American politician and activist who is the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States Senate, United States senator from the state of Vermont. He is the longest-serving independ ...

, was held in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

The march received support from presidential candidate Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (Birth name#Maiden and married names, né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American Civil rights movements, civil rights activist, Politics of the United States, politician, and ordained Baptist minister. Beginning as a ...

.

International reaction

TheUnited Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

adopted General Assembly Resolution 38/7 on 2 November 1983 by a vote of 108 to 9 which "deeply deplores the armed intervention in Grenada, which constitutes a flagrant violation of international law and of the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of that State". It went on to deplore "the death of innocent civilians" and the "killing of the Prime Minister and other prominent Grenadians", and it called for an "immediate cessation of the armed intervention" and demanded, "that free elections be organized".

This was the first overthrow of a Communist government by armed means since the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The Soviet Union said that Grenada had been the object of United States threats, that the invasion violated international law, and that no small nation would find itself safe if the aggression were not rebuffed. The governments of some countries stated that the United States intervention was a return to the era of barbarism. The governments of other countries said the United States had violated several treaties and conventions to which it was a party. A similar resolution was discussed in the United Nations Security Council but it was ultimately vetoed by the United States.

President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

was asked if he was concerned by the lopsided 108–9 vote in the UN General Assembly. He said, "it didn't upset my breakfast at all".

Grenada is part of the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

and the intervention was opposed by several Commonwealth members including the United Kingdom, Trinidad and Tobago, and Canada. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

, a close ally of Reagan on other matters, personally opposed it. Reagan had forewarned her it might happen; she did not know for sure that it was coming until three hours before. Although she publicly supported the action, she sent the following message to Reagan at 12:30 on the morning of the invasion:

Her complaints were not heeded, and the invasion continued as planned. While the fighting was still going on, Reagan phoned Thatcher to apologize for any miscommunication between them, and their long-term friendly relationship endured.

Aftermath and legacy

The American and Caribbean governments quickly reaffirmed Governor-General Sir Paul Scoon as QueenElizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

's sole legitimate representative in Grenada, and hence the only lawful authority on the island. In accordance with Commonwealth constitutional practice, Scoon assumed power as interim head of government and formed an advisory council which named Nicholas Brathwaite as chairman, pending new elections. The New National Party won the elections in December 1984 and formed a government led by Prime Minister Herbert Blaize.

American forces remained in Grenada after combat operations finished in December as part of Operation Island Breeze. The remaining forces performed security missions and assisted members of the Caribbean Peacekeeping Force and the Royal Grenadian Police Force, including military police, special forces, and a specialized intelligence detachment.

In 1985, Queen Elizabeth II visited Grenada and personally presided over the State Opening of the Parliament of Grenada

The Parliament of Grenada is the bicameralism, bicameral legislative body of Grenada. It is composed of the Monarchy in Grenada, monarch and bicameralism, two chambers: the Senate (Grenada), Senate and the House of Representatives (Grenada), H ...

.

In 1986, seventeen political, military and civilian figures were convicted of crimes associated with the 19 October 1983 executions of Prime Minister Bishop and his supporters. The convicted group became known as the Grenada 17. In light of their lengthy imprisonment, Amnesty International