Operation Firedog on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War was a

"The Malayan Emergency: A long Cold War conflict seen through the eyes of the Chinese community in Malaya,"

November 11, 2021, '' The Forum (BBC World Service),'' (radio program) BBC, retrieved November 11, 2021 After establishing a series of jungle bases the MNLA began raiding British colonial police and military installations. Mines, plantations, and trains were attacked by the MNLA to gain independence for Malaya by bankrupting the British occupation. The British attempted to starve the MNLA using

The MNLA commonly employed guerrilla tactics, sabotaging installations, attacking rubber plantations and destroying transport and infrastructure. Support for the MNLA mainly came from around 500,000 of the 3.12 million

The MNLA commonly employed guerrilla tactics, sabotaging installations, attacking rubber plantations and destroying transport and infrastructure. Support for the MNLA mainly came from around 500,000 of the 3.12 million

During the first couple of years of the war, the British forces responded with a terror campaign characterised by high levels of state coercion against the civilian population. Police corruption and the British military's widespread destruction of farmland and burning of homes belonging to villagers rumoured to be helping communists, led to a sharp increase in civilians joining the communist forces.

On the military front, the security forces did not know how to fight an enemy moving freely in the jungle and enjoying support from the Chinese rural population. British planters and miners, who bore the brunt of the communist attacks, began to talk about government incompetence and being betrayed by Whitehall.

The initial government strategy was primarily to guard important economic targets, such as mines and plantation estates. Later, in April 1950, General Sir Harold Briggs, the British Army's Director of Operations, was appointed to Malaya. The central tenet of the Briggs Plan was that the best way to defeat an insurgency, such as the government was facing, was to cut the insurgents off from their supporters among the population. The Briggs Plan also recognised the inhospitable nature of the Malayan jungle. A major part of the strategy involved targeting the MNLA food supply, which Briggs recognised came from three main sources: camps within the Malayan jungle where land was cleared to provide food, aboriginal jungle dwellers who could supply the MNLA with food gathered within the jungle, and the MNLA supporters within the 'squatter' communities on the edge of the jungle.

During the first couple of years of the war, the British forces responded with a terror campaign characterised by high levels of state coercion against the civilian population. Police corruption and the British military's widespread destruction of farmland and burning of homes belonging to villagers rumoured to be helping communists, led to a sharp increase in civilians joining the communist forces.

On the military front, the security forces did not know how to fight an enemy moving freely in the jungle and enjoying support from the Chinese rural population. British planters and miners, who bore the brunt of the communist attacks, began to talk about government incompetence and being betrayed by Whitehall.

The initial government strategy was primarily to guard important economic targets, such as mines and plantation estates. Later, in April 1950, General Sir Harold Briggs, the British Army's Director of Operations, was appointed to Malaya. The central tenet of the Briggs Plan was that the best way to defeat an insurgency, such as the government was facing, was to cut the insurgents off from their supporters among the population. The Briggs Plan also recognised the inhospitable nature of the Malayan jungle. A major part of the strategy involved targeting the MNLA food supply, which Briggs recognised came from three main sources: camps within the Malayan jungle where land was cleared to provide food, aboriginal jungle dwellers who could supply the MNLA with food gathered within the jungle, and the MNLA supporters within the 'squatter' communities on the edge of the jungle.

The Briggs Plan was multifaceted but one aspect has become particularly well known: the forced relocation of some 500,000 rural Malayans, including 400,000 Chinese civilians, into internment camps called " new villages". These villages were surrounded by barbed wire, police posts, and floodlit areas, designed to stop the inmates from being able to contact communist MNLA guerrillas in the jungles.

At the start of the Emergency, the British had 13 infantry battalions in Malaya, including seven partly formed

The Briggs Plan was multifaceted but one aspect has become particularly well known: the forced relocation of some 500,000 rural Malayans, including 400,000 Chinese civilians, into internment camps called " new villages". These villages were surrounded by barbed wire, police posts, and floodlit areas, designed to stop the inmates from being able to contact communist MNLA guerrillas in the jungles.

At the start of the Emergency, the British had 13 infantry battalions in Malaya, including seven partly formed

At all levels of the Malayan government (national, state, and district levels), the military and civil authority was assumed by a committee of military, police and civilian administration officials. This allowed intelligence from all sources to be rapidly evaluated and disseminated and also allowed all anti-guerrilla measures to be co-ordinated.Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya, Director of Operations, Malaya, 1958, Chapter III: Own Forces

Each of the Malay states had a State War Executive Committee which included the State Chief Minister as chairman, the Chief Police Officer, the senior military commander, state home guard officer, state financial officer, state information officer, executive secretary, and up to six selected community leaders. The Police, Military, and Home Guard representatives and the Secretary formed the operations sub-committee responsible for the day-to-day direction of emergency operations. The operations subcommittees as a whole made joint decisions.

At all levels of the Malayan government (national, state, and district levels), the military and civil authority was assumed by a committee of military, police and civilian administration officials. This allowed intelligence from all sources to be rapidly evaluated and disseminated and also allowed all anti-guerrilla measures to be co-ordinated.Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya, Director of Operations, Malaya, 1958, Chapter III: Own Forces

Each of the Malay states had a State War Executive Committee which included the State Chief Minister as chairman, the Chief Police Officer, the senior military commander, state home guard officer, state financial officer, state information officer, executive secretary, and up to six selected community leaders. The Police, Military, and Home Guard representatives and the Secretary formed the operations sub-committee responsible for the day-to-day direction of emergency operations. The operations subcommittees as a whole made joint decisions.

The British Army soon realised that clumsy sweeps by large formations were unproductive. Instead, platoons or sections carried out patrols and laid ambushes, based on intelligence from various sources, including informers, surrendered MNLA personnel, aerial reconnaissance and so on. A typical operation was "Nassau", carried out in the

The British Army soon realised that clumsy sweeps by large formations were unproductive. Instead, platoons or sections carried out patrols and laid ambushes, based on intelligence from various sources, including informers, surrendered MNLA personnel, aerial reconnaissance and so on. A typical operation was "Nassau", carried out in the

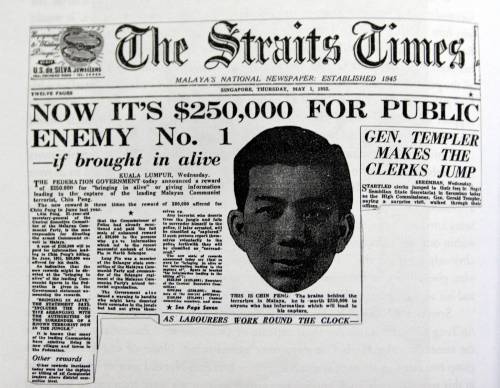

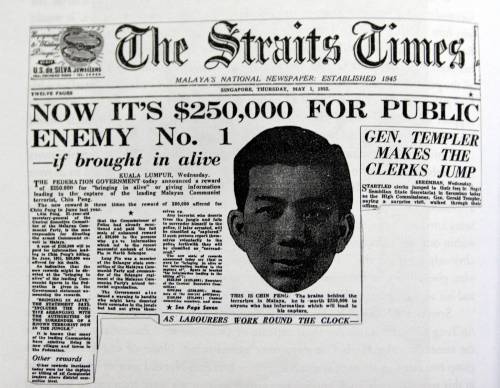

Realising that the tide of the war was turning against him, Chin Peng indicated that he would be ready to meet with British officials alongside senior Malayan politicians in 1955. The talks took place in the Government English School at Baling on 28 December. The MCP was represented by Chin Peng, the Secretary-General,

Realising that the tide of the war was turning against him, Chin Peng indicated that he would be ready to meet with British officials alongside senior Malayan politicians in 1955. The talks took place in the Government English School at Baling on 28 December. The MCP was represented by Chin Peng, the Secretary-General,

During the war British and Commonwealth forces hired

During the war British and Commonwealth forces hired

In 1952, April, the British communist newspaper the ''Daily Worker'' (today known as the ''Morning Star'') published a photograph of British

In 1952, April, the British communist newspaper the ''Daily Worker'' (today known as the ''Morning Star'') published a photograph of British

Lessons from Malaya

eHistory, Ohio State University. * Vietnam was less ethnically fragmentated than Malaya. During the Emergency, most MNLA members were ethnically Chinese and drew support from sections of the Chinese community. However, most of the more numerous indigenous Malays, many of whom were animated by anti-Chinese sentiments, remained loyal to the government and enlisted in high numbers into the security services. * Many Malayans had fought side by side with the British against the

The

The

"Zam: Chinese too fought against communists"

. ''The Star''. A number of films were set against the background of the Emergency, including: * '' The Planter's Wife'' (1952) * '' Windom's Way'' (1957) * ''

guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics ...

fought in British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ms, Tanah Melayu British) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. ...

between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the military forces of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

. The communists fought to win independence for Malaya from the British Empire and to establish a socialist economy, while the Commonwealth forces fought to combat communism and protect British economic and colonial interests.Siver, Christi L. "The other forgotten war: understanding atrocities during the Malayan Emergency." In APSA 2009 Toronto Meeting Paper. 2009., p.36 The conflict was called the "Anti–British National Liberation War" by the MNLA, but an "Emergency" by the British, as London-based insurers would not have paid out in instances of civil wars.

On 17 June 1948, Britain declared a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

in Malaya following attacks on plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

, which in turn were revenge attacks for the killing of left-wing activists. Leader of the Malayan Communist Party

The Malayan Communist Party (MCP), officially the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), was a Marxist–Leninist and anti-imperialist communist party which was active in British Malaya and later, the modern states of Malaysia and Singapore from ...

(MCP) Chin Peng and his allies fled into the jungles and formed the MNLA to wage a war for national liberation against British colonial rule. Many MNLA fighters were veterans of the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army

The Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) was a communist guerrilla army that resisted the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945. Composed mainly of ethnic Chinese guerrilla fighters, the MPAJA was the largest anti-Japanese re ...

(MPAJA), a communist guerrilla army previously trained, armed and funded by the British to fight against Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The communists gained support from a high number of civilians, mainly those from the Chinese community.Datar, Rajan (host), with author Sim Chi Yin; academic Show Ying Xin (Malaysia Institute, Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies an ...

); and academic Rachel Leow (University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

)"The Malayan Emergency: A long Cold War conflict seen through the eyes of the Chinese community in Malaya,"

November 11, 2021, '' The Forum (BBC World Service),'' (radio program) BBC, retrieved November 11, 2021 After establishing a series of jungle bases the MNLA began raiding British colonial police and military installations. Mines, plantations, and trains were attacked by the MNLA to gain independence for Malaya by bankrupting the British occupation. The British attempted to starve the MNLA using

scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

policies through food rationing, killing livestock, and aerial spraying of the herbicide Agent Orange

Agent Orange is a chemical herbicide and defoliant, one of the "tactical use" Rainbow Herbicides. It was used by the U.S. military as part of its herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War from 1961 to 1971. It ...

. British attempts to defeat the communists included extrajudicial killings

An extrajudicial killing (also known as extrajudicial execution or extralegal killing) is the deliberate killing of a person without the lawful authority granted by a judicial proceeding. It typically refers to government authorities, whethe ...

of unarmed villagers, in violation of the Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conv ...

. The most infamous example is the Batang Kali massacre

The Batang Kali massacre was the killing of 24 unarmed villagers by British troops of the Scots Guards on 12 December 1948 during the Malayan Emergency. The incident occurred during counter-insurgency operations against Malay and Chinese commun ...

, which the British press have referred to as "Britain's Mỹ Lai". The Briggs Plan forcibly relocated 400,000 to one million civilians into concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, which were referred to by the British as " New villages". Many Orang Asli

Orang Asli (''lit''. "first people", "native people", "original people", "aborigines people" or "aboriginal people" in Malay) are a heterogeneous indigenous population forming a national minority in Malaysia. They are the oldest inhabitants ...

indigenous communities were also targeted for internment because the British believed that they were supporting the communists. The communists' belief in class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

, and both ethnic and gender equality, inspired many women and indigenous people to join both the MNLA and its undercover supply network the Min Yuen

The Min Yuen ( zh, t=民運, p=mín yùn; ms, Gerakan rakyat) was the civilian branch of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), in resisting the British colonial occupation of Malaya dur ...

.

Although the emergency was declared over in 1960, communist leader Chin Peng renewed the insurgency against the Malaysian government in 1967. This second phase of the insurgency lasted until 1989.

Origins

Socioeconomic issues

At the end of World War II, the withdrawal of Japan left theBritish Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ms, Tanah Melayu British) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. ...

n economy disrupted with widespread unemployment, low wages, and high levels of food price inflation. The weak economy was a factor in the growth of trade union movements and caused a rise in communist party membership, with considerable labour unrest and a large number of strikes occurred between 1946 and 1948. Malayan communists organised a successful 24-hour general strike on 29 January 1946,Eric Stahl, "Doomed from the Start: A New Perspective on the Malayan Insurgency" (master's thesis, 2003) before organising 300 strikes in 1947. To combat rising trade union activity the British used police and soldiers as strikebreakers, and employers enacted mass dismissals, forced evictions of striking workers from their homes, legal harassement, and began cutting the wages of their workers. Colonial police responded to rising trade union activity through arrests, deportations, and beating striking workers to death. Responding to the attacks against trade unions, communist militants began assassinating strikebreakers, and attacking anti-union estates. These attacks were used by the colonial occupation as a pretence to conduct mass arrests of left-wing activists. On 12 June the British colonial occupation banned Malaya's largest trade union the PMFTU.

Malaya's rubber and tin resources were used by the British to pay war debts to the United States and to recover from the damage of the second world war. Malaysian rubber exports to the United States were of greater value than all domestic exports from Britain to America, causing Malaya to be viewed by the British as a vital asset. Britain had prepared for Malaya to become an independent state, but only by handing power to a government which would be subservient to Britain and allow British businesses to keep control of Malaya's natural resources.

The Sungai Siput incident

The first shots of the Malayan Emergency during the Sungai Siput incident, fired at 8:30 am on 16 June 1948, in the office of the Elphil Estate twenty miles east of the Sungai Siput town,Perak

Perak () is a state of Malaysia on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Perak has land borders with the Malaysian states of Kedah to the north, Penang to the northwest, Kelantan and Pahang to the east, and Selangor to the south. Thailand' ...

. Three European plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

managers, Arthur Walker, John Allison, and Ian Christian, were killed by three young Chinese men. Another attack was planned on a fourth European estate nearby, however this failed because the target's jeep broke down making him late for work. More gunmen were sent to kill him but left after failing to find him. The British enacted emergency measures into law in response to the Sungai Siput incident. Under these measures the colonial government outlawed the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and began mass arresting thousands of trade union and left-wing activists.

Formation of the MNLA

Although the Malayan communists had begun preparations for a guerrilla war against the British, the emergency measures and mass arrest of communists and left-wing activists took them by surprise. Led by Chin Peng the remaining Malayan communists retreated to rural areas and formed the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), although their name has commonly been mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA) or the Malayan People's Liberation Army (MPLA). The MNLA was partly a re-formation of theMalayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army

The Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) was a communist guerrilla army that resisted the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945. Composed mainly of ethnic Chinese guerrilla fighters, the MPAJA was the largest anti-Japanese re ...

(MPAJA), the MCP-led guerrilla force which had been the principal resistance in Malaya against the Japanese occupation of Malaya

The then British colony of Malaya was gradually occupied by the Japanese between 8 December 1941 and the Allied surrender at Singapore on 16 February 1942. The Japanese remained in occupation until their surrender to the Allies in 1945. The ...

. The British had secretly helped form the MPAJA in 1942 and trained them in the use of explosives, firearms and radios. Chin Peng was a veteran anti-fascist and trade unionist who had played an integral role in the MPAJA's resistance.

The MNLA began their war for Malayan independence by targeting the colonial resource

Resource refers to all the materials available in our environment which are technologically accessible, economically feasible and culturally sustainable and help us to satisfy our needs and wants. Resources can broadly be classified upon thei ...

extraction industries, namely the tin mines and rubber plantations which were the main sources of income for the British occupation of Malaya. The MNLA attacked these industries in the hopes of bankrupting the British and winning independence by making the colonial administration too expensive to maintain. The MNLA launched their first guerrilla attacks in the Gua Musang district.

Disbanded in December 1945, the MPAJA officially turned in its weapons to the British Military Administration, although many MPAJA soldiers secretly hid stockpiles of weapons in jungle hideouts. Members who agreed to disband were offered economic incentives. Around 4,000 members rejected these incentives and went underground.

Guerrilla war

The MNLA commonly employed guerrilla tactics, sabotaging installations, attacking rubber plantations and destroying transport and infrastructure. Support for the MNLA mainly came from around 500,000 of the 3.12 million

The MNLA commonly employed guerrilla tactics, sabotaging installations, attacking rubber plantations and destroying transport and infrastructure. Support for the MNLA mainly came from around 500,000 of the 3.12 million ethnic Chinese

The Chinese people or simply Chinese, are people or ethnic groups identified with China, usually through ethnicity, nationality, citizenship, or other affiliation.

Chinese people are known as Zhongguoren () or as Huaren () by speakers of s ...

then living in Malaya. There was a particular component of the Chinese community referred to as 'squatters', farmers living on the edge of the jungles where the MNLA were based. This allowed the MNLA to supply themselves with food, in particular, as well as providing a source of new recruits. The ethnic Malay

Malays ( ms, Orang Melayu, Jawi: أورڠ ملايو) are an Austronesian ethnic group native to eastern Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula and coastal Borneo, as well as the smaller islands that lie between these locations — areas that are col ...

population supported them in smaller numbers. The MNLA gained the support of the Chinese because the Chinese were denied the equal right to vote in elections, had no land rights to speak of, and were usually very poor. The MNLA's supply organisation was called the Min Yuen

The Min Yuen ( zh, t=民運, p=mín yùn; ms, Gerakan rakyat) was the civilian branch of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), in resisting the British colonial occupation of Malaya dur ...

(People’s Movement). It had a network of contacts within the general population. Besides supplying material, especially food, it was also important to the MNLA as a source of intelligence.

The MNLA's camps and hideouts were in the inaccessible tropical jungle and had limited infrastructure. Almost 90% of MNLA guerrillas were ethnic Chinese, though there were some Malays, Indonesians and Indians among its members. The MNLA was organised into regiments, although these had no fixed establishments and each included all communist forces operating in a particular region. The regiments had political sections, commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and E ...

s, instructors and secret service. In the camps, the soldiers attended lectures on Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and vario ...

, and produced political newsletters to be distributed to civilians.

In the early stages of the conflict, the guerrillas envisaged establishing control in "liberated areas" from which the government forces had been driven, but did not succeed in this. On 6 October 1951, the MNLA ambushed and killed the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney.

British response

During the first couple of years of the war, the British forces responded with a terror campaign characterised by high levels of state coercion against the civilian population. Police corruption and the British military's widespread destruction of farmland and burning of homes belonging to villagers rumoured to be helping communists, led to a sharp increase in civilians joining the communist forces.

On the military front, the security forces did not know how to fight an enemy moving freely in the jungle and enjoying support from the Chinese rural population. British planters and miners, who bore the brunt of the communist attacks, began to talk about government incompetence and being betrayed by Whitehall.

The initial government strategy was primarily to guard important economic targets, such as mines and plantation estates. Later, in April 1950, General Sir Harold Briggs, the British Army's Director of Operations, was appointed to Malaya. The central tenet of the Briggs Plan was that the best way to defeat an insurgency, such as the government was facing, was to cut the insurgents off from their supporters among the population. The Briggs Plan also recognised the inhospitable nature of the Malayan jungle. A major part of the strategy involved targeting the MNLA food supply, which Briggs recognised came from three main sources: camps within the Malayan jungle where land was cleared to provide food, aboriginal jungle dwellers who could supply the MNLA with food gathered within the jungle, and the MNLA supporters within the 'squatter' communities on the edge of the jungle.

During the first couple of years of the war, the British forces responded with a terror campaign characterised by high levels of state coercion against the civilian population. Police corruption and the British military's widespread destruction of farmland and burning of homes belonging to villagers rumoured to be helping communists, led to a sharp increase in civilians joining the communist forces.

On the military front, the security forces did not know how to fight an enemy moving freely in the jungle and enjoying support from the Chinese rural population. British planters and miners, who bore the brunt of the communist attacks, began to talk about government incompetence and being betrayed by Whitehall.

The initial government strategy was primarily to guard important economic targets, such as mines and plantation estates. Later, in April 1950, General Sir Harold Briggs, the British Army's Director of Operations, was appointed to Malaya. The central tenet of the Briggs Plan was that the best way to defeat an insurgency, such as the government was facing, was to cut the insurgents off from their supporters among the population. The Briggs Plan also recognised the inhospitable nature of the Malayan jungle. A major part of the strategy involved targeting the MNLA food supply, which Briggs recognised came from three main sources: camps within the Malayan jungle where land was cleared to provide food, aboriginal jungle dwellers who could supply the MNLA with food gathered within the jungle, and the MNLA supporters within the 'squatter' communities on the edge of the jungle.

The Briggs Plan was multifaceted but one aspect has become particularly well known: the forced relocation of some 500,000 rural Malayans, including 400,000 Chinese civilians, into internment camps called " new villages". These villages were surrounded by barbed wire, police posts, and floodlit areas, designed to stop the inmates from being able to contact communist MNLA guerrillas in the jungles.

At the start of the Emergency, the British had 13 infantry battalions in Malaya, including seven partly formed

The Briggs Plan was multifaceted but one aspect has become particularly well known: the forced relocation of some 500,000 rural Malayans, including 400,000 Chinese civilians, into internment camps called " new villages". These villages were surrounded by barbed wire, police posts, and floodlit areas, designed to stop the inmates from being able to contact communist MNLA guerrillas in the jungles.

At the start of the Emergency, the British had 13 infantry battalions in Malaya, including seven partly formed Gurkha

The Gurkhas or Gorkhas (), with endonym Gorkhali ), are soldiers native to the Indian subcontinent, Indian Subcontinent, chiefly residing within Nepal and some parts of Northeast India.

The Gurkha units are composed of Nepalis and Indian Go ...

battalions, three British battalions, two battalions of the Royal Malay Regiment

The Royal Malay Regiment ( ms, Rejimen Askar Melayu DiRaja; Jawi: ) is the premier unit of the Malaysian Army's two infantry regiments. At its largest, the Malay Regiment comprised 27 battalions. At present, three battalions are parachute trai ...

and a British Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

Regiment being used as infantry.Karl Hack, ''Defense & Decolonisation in South-East Asia'', p. 113. This force was too small to fight the insurgents effectively, and more infantry battalions were needed in Malaya. The British brought in soldiers from units such as the Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious warfare, amphibious light infantry and also one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighti ...

and King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from Britain's various possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions within ...

. Another element in the strategy was the re-formation of the Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-te ...

in 1950 as a specialised reconnaissance, raiding, and counter-insurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

unit.

The Permanent Secretary of Defence for Malaya, Sir Robert Grainger Ker Thompson, had served in the Chindits

The Chindits, officially as Long Range Penetration Groups, were special operations units of the British and Indian armies which saw action in 1943–1944 during the Burma Campaign of World War II.

The British Army Brigadier Orde Wingate form ...

in Burma during World War II. Thompson's in-depth experience of jungle warfare proved invaluable during this period as he was able to build effective civil-military relations and was one of the chief architects of the counter-insurgency plan in Malaya.

On 6 October 1951, the British High Commissioner in Malaya, Sir Henry Gurney, was assassinated during an MNLA ambush. General Gerald Templer was chosen to become the new High Commissioner in January 1952. During Templer's two-year command, "two-thirds of the guerrillas were wiped out and lost over half their strength, the incident rate fell from 500 to less than 100 per month and the civilian and security force casualties from 200 to less than 40." Orthodox historiography suggests that Templer changed the situation in the Emergency and his actions and policies were a major part of British success during his period in command. Revisionist historians have challenged this view and frequently support the ideas of Victor Purcell

Victor William Williams Saunders Purcell CMG (26 January 1896 – 2 January 1965) was a British colonial public servant, historian, poet, and Sinologist in Malaya (now Malaysia).

He was educated at Bancroft's School and joined the British Army ...

, a Sinologist who as early as 1954 claimed that Templer merely continued policies begun by his predecessors.

The MNLA was vastly outnumbered by the British forces and their Commonwealth and colonial allies in terms of regular full-time soldiers. Siding with the British occupation were a maximum of 40,000 British and other Commonwealth troops, 250,000 Home Guard members, and 66,000 police agents. Supporting the communists were 7,000+ communist guerrillas (1951 peak), an estimated 1,000,000 sympathisers, and an unknown number of civilian Min Yuen

The Min Yuen ( zh, t=民運, p=mín yùn; ms, Gerakan rakyat) was the civilian branch of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), in resisting the British colonial occupation of Malaya dur ...

supporters and Orang Asli

Orang Asli (''lit''. "first people", "native people", "original people", "aborigines people" or "aboriginal people" in Malay) are a heterogeneous indigenous population forming a national minority in Malaysia. They are the oldest inhabitants ...

sympathisers.

Control of anti-guerrilla operations

At all levels of the Malayan government (national, state, and district levels), the military and civil authority was assumed by a committee of military, police and civilian administration officials. This allowed intelligence from all sources to be rapidly evaluated and disseminated and also allowed all anti-guerrilla measures to be co-ordinated.Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya, Director of Operations, Malaya, 1958, Chapter III: Own Forces

Each of the Malay states had a State War Executive Committee which included the State Chief Minister as chairman, the Chief Police Officer, the senior military commander, state home guard officer, state financial officer, state information officer, executive secretary, and up to six selected community leaders. The Police, Military, and Home Guard representatives and the Secretary formed the operations sub-committee responsible for the day-to-day direction of emergency operations. The operations subcommittees as a whole made joint decisions.

At all levels of the Malayan government (national, state, and district levels), the military and civil authority was assumed by a committee of military, police and civilian administration officials. This allowed intelligence from all sources to be rapidly evaluated and disseminated and also allowed all anti-guerrilla measures to be co-ordinated.Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya, Director of Operations, Malaya, 1958, Chapter III: Own Forces

Each of the Malay states had a State War Executive Committee which included the State Chief Minister as chairman, the Chief Police Officer, the senior military commander, state home guard officer, state financial officer, state information officer, executive secretary, and up to six selected community leaders. The Police, Military, and Home Guard representatives and the Secretary formed the operations sub-committee responsible for the day-to-day direction of emergency operations. The operations subcommittees as a whole made joint decisions.

Nature of warfare

The British Army soon realised that clumsy sweeps by large formations were unproductive. Instead, platoons or sections carried out patrols and laid ambushes, based on intelligence from various sources, including informers, surrendered MNLA personnel, aerial reconnaissance and so on. A typical operation was "Nassau", carried out in the

The British Army soon realised that clumsy sweeps by large formations were unproductive. Instead, platoons or sections carried out patrols and laid ambushes, based on intelligence from various sources, including informers, surrendered MNLA personnel, aerial reconnaissance and so on. A typical operation was "Nassau", carried out in the Kuala Langat

The Kuala Langat District is a district of Selangor, Malaysia. It is situated in the southwestern part of Selangor. It covers an area of 858 square kilometres, and had a population of 307,787 at the 2020 Census (exclude foreign). It is bordered ...

swamp (excerpt from the Marine Corps School's ''The Guerrilla – and how to Fight Him''):

Insurgents had numerous advantages over British forces since they lived in closer proximity to villagers, they sometimes had relatives or close friends in the village, and they were not afraid to threaten violence or torture and murder village leaders as an example to the others, which forced them to assist them with food and information. British forces thus faced a dual threat: the insurgents and the silent network in villages who supported them. British troops often described the terror of jungle patrols. In addition to watching out for insurgent fighters, they had to navigate difficult terrain and avoid dangerous animals and insects. Many patrols would stay in the jungle for days, even weeks, without encountering the MNLA guerrillas. That strategy led to the infamous Batang Kali massacre

The Batang Kali massacre was the killing of 24 unarmed villagers by British troops of the Scots Guards on 12 December 1948 during the Malayan Emergency. The incident occurred during counter-insurgency operations against Malay and Chinese commun ...

in which 24 unarmed villagers were executed by British troops.

Commonwealth contribution

Commonwealth forces from Africa and the Pacific fought on the British side during the Malayan Emergency. These included troops from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Kenya,Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasala ...

, Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a r ...

and Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing colony, self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The reg ...

.

Australia and Pacific Commonwealth forces

Australian ground forces, specifically the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2 RAR), began fighting in Malaya in 1955. The battalion was later replaced by 3 RAR, which in turn was replaced by1 RAR

1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR) is a regular motorised infantry battalion of the Australian Army. 1 RAR was first formed as the 65th Australian Infantry Battalion of the 34th Brigade (Australia) on Balikpapan in 1945 and since ...

. The Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

contributed No. 1 Squadron (Avro Lincoln

The Avro Type 694 Lincoln is a British four-engined heavy bomber, which first flew on 9 June 1944. Developed from the Avro Lancaster, the first Lincoln variants were initially known as the Lancaster IV and V; these were renamed Lincoln I and I ...

bombers) and No. 38 Squadron (C-47

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota (RAF, RAAF, RCAF, RNZAF, and SAAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II and remained in ...

transports), operating out of Singapore, early in the conflict. In 1955, the RAAF extended Butterworth air base

RMAF Butterworth ( ms, TUDM Butterworth) is an active Air Force Station of the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) situated from Butterworth in Penang, Malaysia. It is currently home to the ''Headquarters Integrated Area Defence System'' (HQIADS ...

, from which Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

bombers of No. 2 Squadron (replacing No. 1 Squadron) and CAC Sabres of No. 78 Wing carried out ground attack missions against the guerrillas. The Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister o ...

destroyers and joined the force in June 1955. Between 1956 and 1960, the aircraft carriers and and destroyers , , , , , , , and were attached to the Commonwealth Strategic Reserve

The British Commonwealth Far East Strategic Reserve (commonly referred to as the ''Far East Strategic Reserve'' or the ''FESR'') was a joint military force of the British, Australian, and New Zealand armed forces. Created in the 1950s and based in ...

forces for three to nine months at a time. Several of the destroyers fired on communist positions in Johor

Johor (; ), also spelled as Johore, is a state of Malaysia in the south of the Malay Peninsula. Johor has land borders with the Malaysian states of Pahang to the north and Malacca and Negeri Sembilan to the northwest. Johor shares mariti ...

State.

New Zealand's first contribution came in 1949, when Douglas C-47 Dakotas of RNZAF No. 41 Squadron were attached to the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

's Far East Air Force. New Zealand became more directly involved in the conflict in 1955; from May, RNZAF de Havilland Vampire

The de Havilland Vampire is a British jet fighter which was developed and manufactured by the de Havilland Aircraft Company. It was the second jet fighter to be operated by the RAF, after the Gloster Meteor, and the first to be powered by ...

s and Venoms

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a st ...

began to fly strike missions. In November 1955 133 soldiers of what was to become the Special Air Service of New Zealand

The 1st New Zealand Special Air Service Regiment, abbreviated as 1 NZSAS Regt, was formed on 7 July 1955 and is the Special forces unit of the New Zealand Army, closely modelled on the British Special Air Service (SAS). It traces its origins to ...

arrived from Singapore, for training in-country with the British SAS, beginning operations by April 1956. The Royal New Zealand Air Force

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) ( mi, Te Tauaarangi o Aotearoa, "The Warriors of the Sky of New Zealand"; previously ', "War Party of the Blue") is the aerial service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed from New Zeal ...

continued to carry out strike missions with Venoms of No. 14 Squadron and later No. 75 Squadron English Electric Canberra

The English Electric Canberra is a British first-generation, jet-powered medium bomber. It was developed by English Electric during the mid- to late 1940s in response to a 1944 Air Ministry requirement for a successor to the wartime de Havil ...

s bombers, as well as supply-dropping operations in support of anti-guerrilla forces, using the Bristol Freighter

The Bristol Type 170 Freighter is a British twin-engine aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company as both a freighter and airliner. Its best known use was as an air ferry to carry cars and their passengers over relatively s ...

. A total of 1,300 New Zealanders served in the Malayan Emergency between 1948 and 1964, and fifteen lost their lives.

Fijian troops fought in the Malayan Emergency from 1952 to 1956, some 1,600 Fijian troops served. The first to arrive were the 1st Battalion, Fiji Infantry Regiment

The Fiji Infantry Regiment is the main combat element of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces. It is a light infantry regiment consisting of six battalions, of which three are regular army and three are Territorial Force. The regiment was formed w ...

. Twenty-five Fijian troops died in combat in Malaya. Friendships on and off the battlefield developed between the two nations; the first Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman

Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj ibni Almarhum Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah ( ms, تونكو عبد الرحمن ڤوترا الحاج ابن سلطان عبد الحميد حليم شاه, label= Jawi, script=arab, italic=unset; 8 Febru ...

, became a friend and mentor to Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau

Ratu Sir Edward Tuivanuavou Tugi Cakobau (21 December 1908 – 25 June 1973) was a Fijian chief, soldier, politician and cricketer. He was a member of the Fijian legislature from 1944 until his death, also serving as Minister for Commerce, Ind ...

, who was a commander of the Fijian Battalion, and who later went on to become the Deputy PM of Fiji and whose son Brigadier General Ratu Epeli was a future President of Fiji. The experience was captured in the documentary, ''Back to Batu Pahat''.

African Commonwealth forces

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing colony, self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The reg ...

and its successor, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation or CAF, was a colonial federation that consisted of three southern African territories: the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia and the B ...

, contributed two units to Malaya. Between 1951 and 1953, white Southern Rhodesian volunteers formed "C" Squadron of the Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-te ...

. The Rhodesian African Rifles, comprising black soldiers and warrant officer

Warrant officer (WO) is a rank or category of ranks in the armed forces of many countries. Depending on the country, service, or historical context, warrant officers are sometimes classified as the most junior of the commissioned ranks, the mo ...

s but led by white officers, served in Johor

Johor (; ), also spelled as Johore, is a state of Malaysia in the south of the Malay Peninsula. Johor has land borders with the Malaysian states of Pahang to the north and Malacca and Negeri Sembilan to the northwest. Johor shares mariti ...

e state for two years from 1956. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions of the King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from Britain's various possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions within ...

from Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasala ...

, Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesi ...

and Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

respectively also served there suffering 23 losses.

The October Resolution

Later, MNLA leader Chin Peng stated that the killing of Henry Gurney had little effect and that the communists were already altering their strategy, according to new guidelines enshrined in the so-called "October Resolutions". The October Resolutions, a response to the Briggs Plan, involved a change of tactics by the MNLA by reducing attacks on economic targets and civilian collaborators, redirecting their efforts towards political organisation and subversion, and bolstering the supply network from theMin Yuen

The Min Yuen ( zh, t=民運, p=mín yùn; ms, Gerakan rakyat) was the civilian branch of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), in resisting the British colonial occupation of Malaya dur ...

as well as jungle farming.

Amnesty declaration

On 8 September 1955, the Government of the Federation of Malaya issued a declaration of amnesty to the communists. The Government of Singapore issued an identical offer at the same time.Tunku Abdul Rahman

Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj ibni Almarhum Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah ( ms, تونكو عبد الرحمن ڤوترا الحاج ابن سلطان عبد الحميد حليم شاه, label= Jawi, script=arab, italic=unset; 8 Febru ...

, as Chief Minister, offered amnesty but rejected negotiations with the MNLA. The amnesty read that:

* Those of you who come in and surrender will not be prosecuted for any offence connected with the Emergency, which you have committed under Communist direction, either before this date or in ignorance of this declaration.

* You may surrender now and to whom you like including to members of the public.

* There will be no general "ceasefire" but the security forces will be on alert to help those who wish to accept this offer and for this purpose local "ceasefire" will be arranged.

* The Government will conduct investigations on those who surrender. Those who show that they are genuinely intent to be loyal to the Government of Malaya and to give up their Communist activities will be helped to regain their normal position in society and be reunited with their families. As regards the remainder, restrictions will have to be placed on their liberty but if any of them wish to go to China, their request will be given due consideration.Prof Madya Dr. Nik Anuar Nik Mahmud, Tunku Abdul Rahman and His Role in the Baling Talks

Following this amnesty declaration, an intensive publicity campaign was launched by the government. Alliance Ministers in the Federal Government travelled extensively up and down the country exhorting the people to call upon the communists to lay down their arms and take advantage of the amnesty. Despite the campaign, few Communist guerrillas chose to surrender. Some political activists criticised the amnesty for being too restrictive and for being a rewording of surrender terms which had already been in force for a long period. These critics advocated for direct negotiations with the communist guerrillas of the MNLA and MCP to work on a peace settlement. Leading officials of the Labour Party had, as part of the settlement, not excluded the possibility of recognition of the MCP as a political organisation. Within the Alliance itself, influential elements in both the MCA

MCA may refer to:

Astronomy

* Mars-crossing asteroid, an asteroid whose orbit crosses that of Mars

Aviation

* Minimum crossing altitude, a minimum obstacle crossing altitude for fixes on published airways

* Medium Combat Aircraft, a 5th gen ...

and UMNO

The United Malays National Organisation ( Malay: ; Jawi: ; abbreviated UMNO () or less commonly PEKEMBAR), is a nationalist right-wing political party in Malaysia. As the oldest continuous national political party within Malaysia (since its ...

were endeavouring to persuade the Chief Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, to hold negotiations with the MCP.

Baling talks and their consequences

Realising that the tide of the war was turning against him, Chin Peng indicated that he would be ready to meet with British officials alongside senior Malayan politicians in 1955. The talks took place in the Government English School at Baling on 28 December. The MCP was represented by Chin Peng, the Secretary-General,

Realising that the tide of the war was turning against him, Chin Peng indicated that he would be ready to meet with British officials alongside senior Malayan politicians in 1955. The talks took place in the Government English School at Baling on 28 December. The MCP was represented by Chin Peng, the Secretary-General, Rashid Maidin

Rashid Maidin (10 October 1917 – 1 September 2006), sometimes given as Rashid Mahideen, was a senior leader of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM).

Personal life

He was born in Kampung Gunung Mesah, Gopeng, Perak; coincidentally on the same ...

and Chen Tien

Chen Tien or Chen Tian () ( – 1990) was the head of the Central Propaganda Department of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM).

Political career

Chen was present during the Baling Talks, along with the CPM's secretary-general Chin Peng and se ...

, head of the MCP's Central Propaganda Department. On the other side were three elected national representatives, Tunku Abdul Rahman

Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj ibni Almarhum Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah ( ms, تونكو عبد الرحمن ڤوترا الحاج ابن سلطان عبد الحميد حليم شاه, label= Jawi, script=arab, italic=unset; 8 Febru ...

, Dato' Tan Cheng-Lock and David Saul Marshall

David Saul Marshall (12 March 1908 – 12 December 1995), born David Saul Mashal, was a Singaporean lawyer and politician who served as Chief Minister of Singapore from 1955 until his resignation in 1956, after his delegation to London regarding ...

, the Chief Minister of Singapore.

Chin Peng left the jungle to negotiate with the leader of the Federation, Tunku Abdul Rahman

Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj ibni Almarhum Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah ( ms, تونكو عبد الرحمن ڤوترا الحاج ابن سلطان عبد الحميد حليم شاه, label= Jawi, script=arab, italic=unset; 8 Febru ...

with the goal of ending the conflict. However, the British Intelligence Service was worried that the MCP would regain influence in society and the Malayan government representatives, led by Tunku Abdul Rahman, categorically dismissed Chin Peng's demands. As a result, the conflict heightened, and, in response, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

sent NZSAS soldiers, No. 14 Squadron RNZAF, No. 41 (Bristol Freighter) Squadron RNZAF and, later, No. 75 Squadron RNZAF

No. 75 Squadron RNZAF was an air combat squadron of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. It was formed from the RAF's World War II bomber squadron, No. 75 Squadron, which had been initially equipped by the New Zealand government and was largely man ...

; other Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

members also sent troops to aid the British.

Following the failure of the talks, Tunku decided to withdraw the amnesty on 8 February 1956, five months after it had been offered, stating that he would not be willing to meet the Communists again unless they indicated beforehand their intention to make "a complete surrender". Despite the failure of the Baling Talks, the MCP made various efforts to resume peace talks with the Malayan government, all without success. Meanwhile, discussions began in the new Emergency Operations Council to intensify the "People's War" against the guerillas. In July 1957, a few weeks before independence, the MCP made another attempt at peace talks, suggesting the following conditions for a negotiated peace:

* its members should be given privileges enjoyed by citizens

* a guarantee that political as well as armed members of the MCP would not be punished

The failure of the talks affected MCP policy. The strength of the MNLA and 'Min Yuen' declined to only 1830 members in August 1957. Those who remained faced exile, or death in the jungle. However, Tunku Abdul Rahman did not respond to the MCP's proposals. As Malaya declared its independence from the British under Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman on 31 August 1957, the insurrection lost its rationale as a war of colonial liberation.

The last serious resistance from MRLA guerrillas ended with a surrender in the Telok Anson

Teluk Intan is a town in Hilir Perak District, Perak, Malaysia. It is the district capital and largest town in Hilir Perak district and fourth largest town in the state of Perak with an estimated population of around 172,505, more than half of ...

marsh area in 1958. The remaining MRLA forces fled to the Thai border and further east. On 31 July 1960 the Malayan government declared the state of emergency over, and Chin Peng left south Thailand for Beijing where he was accommodated by the Chinese authorities in the International Liaison Bureau, where many other Southeast Asian Communist Party leaders were housed.

Agent Orange

During the Malayan Emergency, Britain became the first nation in history to use ofherbicides

Herbicides (, ), also commonly known as weedkillers, are substances used to control undesired plants, also known as weeds.EPA. February 201Pesticides Industry. Sales and Usage 2006 and 2007: Market Estimates. Summary in press releasMain page fo ...

and defoliants

A defoliant is any herbicidal chemical sprayed or dusted on plants to cause their leaves to fall off. Defoliants are widely used for the selective removal of weeds in managing croplands and lawns. Worldwide use of defoliants, along with the ...

as a military weapon. It was used to destroy bushes, food crops, and trees to deprive the insurgents of both food and cover, playing a role in Britain's food denial campaign during the early 1950s. A variety of herbicides were used to clear lines of communication and wipe out food crops as part of this strategy. One of the herbicides, Trioxone, was an even mixture of butyl esters of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D. This mixture was virtually identical to the later Agent Orange, though Trioxone likely had a heavier contamination of the health-damaging dioxin impurity.

In 1952, Trioxone and mixtures of the aforementioned herbicides, were sent along a number of key roads. From June to October 1952, 1,250 acres of roadside vegetation at possible ambush points were sprayed with defoliant, described as a policy of "national importance." The British reported that the use of herbicides and defoliants could be effectively replaced by removing vegetation by hand and the spraying was stopped. However, after that strategy failed, the use of herbicides and defoliants in effort to fight the insurgents was restarted under the command of British General Sir Gerald Templer in February 1953 as a means of destroying food crops grown by communist forces in jungle clearings. Helicopters

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attribu ...

and fixed-wing aircraft

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air flying machine, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using wings that generate lift caused by the aircraft's forward airspeed and the shape of the wings. Fixed-wing aircraft are dist ...

despatched sodium trichloroacetate

Sodium trichloroacetate is a chemical compound with a formula of CCl3CO2Na. It is used to increase sensitivity and precision during transcript mapping. It was previously used as an herbicide starting in the 1950s but regulators removed it from th ...

and Trioxone, along with pellets of chlorophenyl N,N-Dimethyl-1-naphthylamine onto crops such as sweet potatoes and maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

. Many Commonwealth personnel who handled and/or used Agent Orange during the conflict suffered from serious exposure to dioxin and Agent Orange. An estimated 10,000 civilians and insurgents in Malaya also suffered from the effects of the defoliant, but many historians think that the number is much larger since Agent Orange was used on a large scale in the Malayan conflict and, unlike the US, the British government limited information about its use to avoid negative world public opinion. The prolonged absence of vegetation caused by defoliation also resulted in major soil erosion

Soil erosion is the denudation or wearing away of the upper layer of soil. It is a form of soil degradation. This natural process is caused by the dynamic activity of erosive agents, that is, water, ice (glaciers), snow, air (wind), plants, a ...

to areas of Malaya.

After the Malayan Conflict ended in 1960, the US used the British precedent in deciding that the use of defoliants was a legally-accepted tactic of warfare. US Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the F ...

advised US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

John F. Kennedy that the precedent of using herbicide in warfare had been established by the British through their use of aircraft to spray herbicide and thus destroy enemy crops and thin the thick jungle of northern Malaya.

Casualties

During the conflict, security forces killed 6,710 MRLA guerrillas and captured 1,287, while 2,702 guerrillas surrendered during the conflict, and approximately 500 more did so at its conclusion. 1,345 Malayan troops and police were killed during the fighting, as well as 519 Commonwealth personnel. 2,478 civilians were killed, with another 810 recorded as missing.War crimes

Commonwealth

War crimes have been broadly defined by the Nuremberg Principles as "violations of the laws or customs of war," which includes massacres,bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

ings of civilian targets, terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

, mutilation

Mutilation or maiming (from the Latin: ''mutilus'') refers to Bodily harm, severe damage to the body that has a ruinous effect on an individual's quality of life. It can also refer to alterations that render something inferior, ugly, dysfunction ...

, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

, and the murder of detainees

Detention is the process whereby a state or private citizen lawfully holds a person by removing their freedom or liberty at that time. This can be due to (pending) criminal charges preferred against the individual pursuant to a prosecution or ...

and prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

. Additional common crimes include theft

Theft is the act of taking another person's property or services without that person's permission or consent with the intent to deprive the rightful owner of it. The word ''theft'' is also used as a synonym or informal shorthand term for som ...

, arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wate ...

, and the destruction of property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

not warranted by military necessity

Military necessity, along with distinction, and proportionality, are three important principles of international humanitarian law governing the legal use of force in an armed conflict.

Attacks

Military necessity is governed by several constra ...

.

Torture

During the Malayan conflict, there were instances during operations to find insurgents where British troops detained andtorture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

d villagers who were suspected of aiding the insurgents. Brian Lapping said that there was "some vicious conduct by the British forces, who routinely beat up Chinese squatters when they refused, or possibly were unable, to give information" about the insurgents. ''The'' ''Scotsman'' newspaper lauded these tactics as a good practice since "simple-minded peasants are told and come to believe that the communist leaders are invulnerable". Some civilians and detainees were also shot, either because they attempted to flee from and potentially aid insurgents or simply because they refused to give intelligence to British forces.

Widespread use of arbitrary detention, punitive actions against villages, and use of torture by the police, "created animosity" between Chinese squatters and British forces in Malaya and "were therefore counterproductive in generating the one resource critical in a counterinsurgency, good intelligence".

British troops were often unable to tell the difference between enemy combatant

Combatant is the legal status of an individual who has the right to engage in hostilities during an armed conflict. The legal definition of "combatant" is found at article 43(2) of Additional Protocol I (AP1) to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. It ...

s and civilian

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not " combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant ...

s while conducting military operations through the jungles, due to the fact that many Min Yuen wore civilian clothing and had support from sympathetic civilian populations.

Batang Kali Massacre

During theBatang Kali massacre

The Batang Kali massacre was the killing of 24 unarmed villagers by British troops of the Scots Guards on 12 December 1948 during the Malayan Emergency. The incident occurred during counter-insurgency operations against Malay and Chinese commun ...

, 24 unarmed civilians were executed by the Scots Guard

The Scots Guards (SG) is one of the five Foot Guards regiments of the British Army. Its origins are as the personal bodyguard of King Charles I of England and Scotland. Its lineage can be traced back to 1642, although it was only placed on the ...

s near a rubber plantation at Sungai Rimoh near Batang Kali

Batang Kali is a city and mukim in Hulu Selangor District, Selangor, Malaysia. The city is designated as a transit point to Genting Highlands, a renowned resort city. Originally just a small town gaining traction due to the development of Li ...

in Selangor

Selangor (; ), also known by its Arabic honorific Darul Ehsan, or "Abode of Sincerity", is one of the 13 Malaysian states. It is on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia and is bordered by Perak to the north, Pahang to the east, Negeri Sem ...

in December 1948. All the victims were male, ranging in age from young teenage boys to elderly men. Many of the victims' bodies were found to have been mutilated and their village of Batang Kali was burned to the ground. No weapons were found when the village was searched. The only survivor of the killings was a man named Chong Hong who was in his 20s at the time. He fainted and was presumed dead. Soon afterwards the British colonial government staged a coverup of British military abuses which served to obfuscate the exact details of the massacre.

The massacre later became the focus of decades of legal battles between the UK government and the families of the civilians executed by British troops. According to Christi Silver, Batang Kali was notable in that it was the only incident of mass killings by Commonwealth forces during the war, which Silver attributes to the unique subculture of the Scots Guards and poor enforcement of discipline by junior officers.

Internment camps

As part of the Briggs Plan devised by British General Sir Harold Briggs, 500,000 people (roughly ten percent of Malaya's population) were forced from their homes by British forces. Tens of thousands of homes were destroyed, and many people were imprisoned in BritishInternment Camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

s called " new villages". During the Malayan Emergency, 450 new villages were created. The policy aimed to inflict collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member of that group, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends and neighbors of the perpetrator. Because ind ...

on villages where people were thought to be support communism, and also to isolate civilians from guerrilla activity. Many of the forced evictions involved the destruction of existing settlements which went beyond the justification of military necessity

Military necessity, along with distinction, and proportionality, are three important principles of international humanitarian law governing the legal use of force in an armed conflict.

Attacks

Military necessity is governed by several constra ...

. This practice was prohibited by the Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conv ...

and customary international law

Customary international law is an aspect of international law involving the principle of custom. Along with general principles of law and treaties, custom is considered by the International Court of Justice, jurists, the United Nations, and its ...

, which stated that the destruction of property must not happen unless rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.

Collective punishment

A key British war measure was inflicting collective punishments on villages whose people were deemed to be aiding the insurgents. At Tanjong Malim

Tanjong Malim, or Tanjung Malim, is a town in Muallim District, Perak, Malaysia. It is approximately north of Kuala Lumpur and 120 km south of Ipoh via the North–South Expressway. It lies on the Perak-Selangor state border, with Sunga ...

in March 1952, Templer imposed a twenty-two-hour house curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

, banned everyone from leaving the village, closed the schools, stopped bus services, and reduced the rice rations for 20,000 people. The last measure prompted the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to write to the Colonial Office to note that the "chronically undernourished Malayan" might not be able to survive as a result. "This measure is bound to result in an increase, not only of sickness but also of deaths, particularly amongst the mothers and very young children". Some people were fined for leaving their homes to use external latrines. In another collective punishment, at Sengei Pelek the following month, measures included a house curfew, a reduction of 40 percent in the rice ration and the construction of a chain-link fence 22 yards outside the existing barbed wire fence around the town. Officials explained that the measures were being imposed upon the 4,000 villagers "for their continually supplying food" to the insurgents and "because they did not give information to the authorities".

Deportations

Over the course of the war, some 30,000 mostly ethnic Chinese were deported by the British authorities to mainland China.Iban headhunting and scalping

During the war British and Commonwealth forces hired

During the war British and Commonwealth forces hired Iban

IBAN or Iban or Ibán may refer to:

Banking

* International Bank Account Number

Ethnology

* Iban culture

* Iban language

* Iban people

Given name

Cycling

* Iban Iriondo (born 1984)

* Iban Mayo (born 1977)

* Iban Mayoz (born 1981)

Football

* ...