Opabinia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Opabinia regalis'' is an

Middle Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita and Merostomata

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 57: 145-228. The generic name is derived from Opabin pass between Mount Hungabee and Mount Biddle, southeast of Lake O'Hara, British Columbia,

File:20191108 Opabinia regalis.png, Restoration

File:20210222 Opabinia size.png, Size estimation

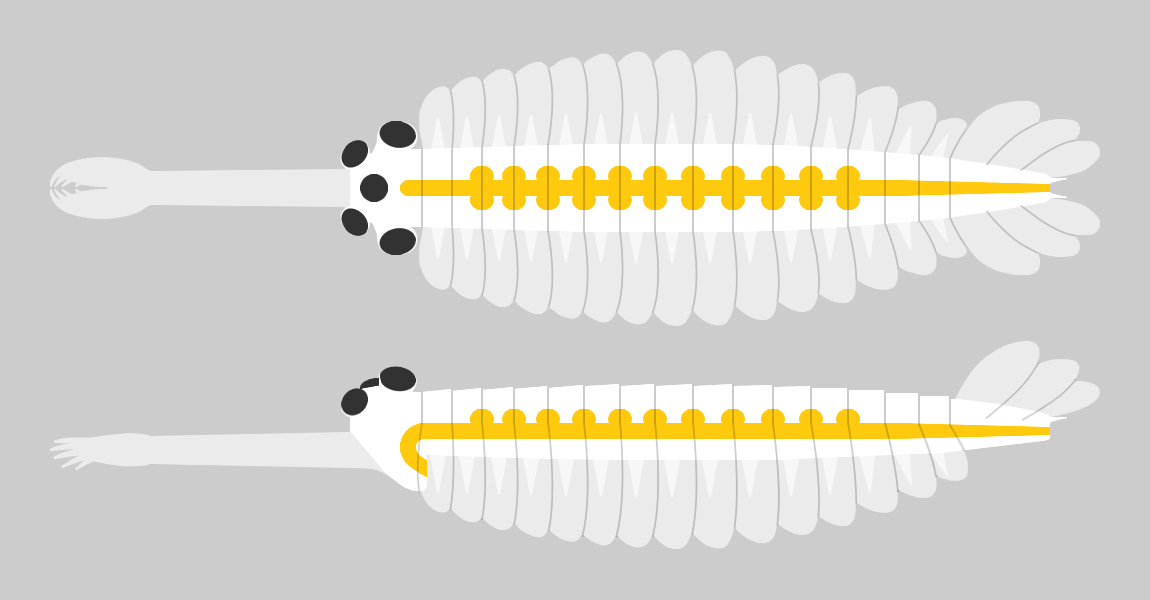

''Opabinia'' looked so strange that the audience at the first presentation of Whittington's analysis laughed. The length of ''Opabinia regalis'' from head (excluding proboscis) to tail end ranged between and . One of the most distinctive characters of ''Opabinia'' is the hollow

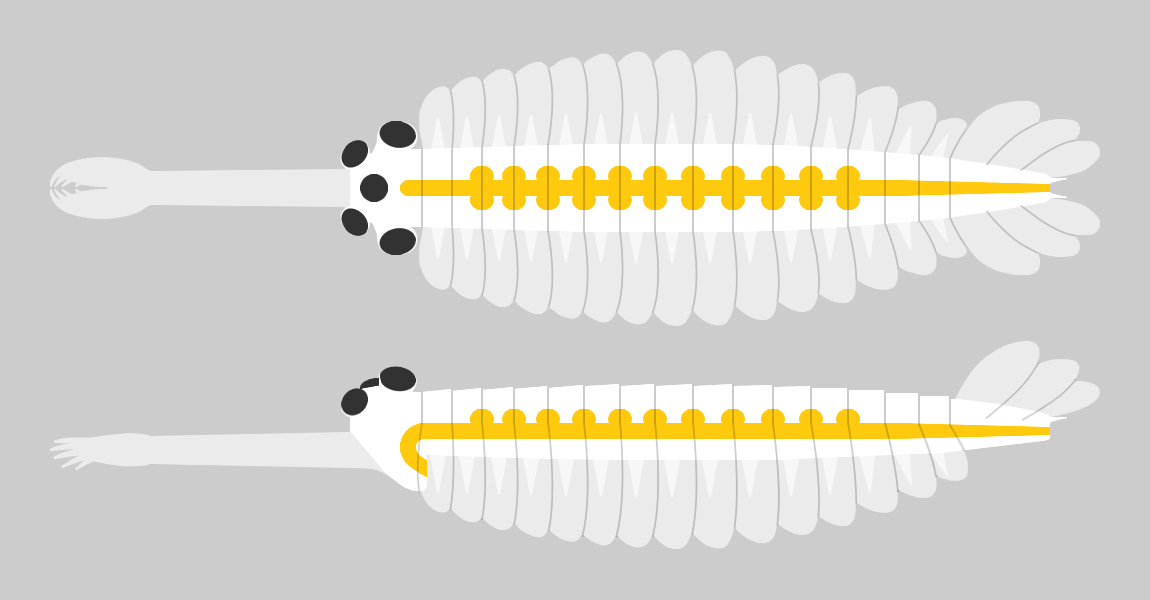

File:20210809 Opabinia regalis flap gill interpretation.png, Various interpretations on the flap and gill structures of ''Opabinia regalis''

A: Whittington (1975), B: Bergström (1986), C: Budd (1996), D: Zhang & Briggs (2007), E: Budd & Daley (2011) File:20210807 Opabinia regalis trunk cross section.png, ''Opabinia'' cross-section based on Budd and Daley (2011)

Whittington (1975) interpreted the gills as paired extensions attached dorsally to the bases of all but the first flaps on each side, and thought that these gills were flat underneath, had overlapping layers on top. Bergström (1986) revealed the "overlapping layers" were rows of individual blades, interpreted the flaps as part of dorsal coverings ( tergite) over the upper surface of the body, with blades attached underneath each of them. Budd (1996) thought the gill blades attached along the front edges on the dorsal side of all except the first flaps. He also found marks inside the flaps' front edges that he interpreted as internal channels connecting the gills to the interior of the body, much as Whittington interpreted the mark along the proboscis as an internal channel. Zhang and Briggs (2007) however, interpreted all flaps have posterior spacing where the gill blades attached. Budd and Daley (2011) reject the reconstruction by Zhang & Briggs, showing the flaps have complete posterior edges as in previous reconstructions. They mostly follow the reconstruction by Budd (1996) with modifications on some details (e.g. the first flap pair also have gills; the attachment point of gill blades located more posteriorly than previously thought). Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (

Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of  While this discussion about specific fossils such as ''Opabinia'' and ''Anomalocaris'' was going on in the late 20th century, the concept of stem groups was introduced to cover evolutionary "aunts" and "cousins". A

While this discussion about specific fossils such as ''Opabinia'' and ''Anomalocaris'' was going on in the late 20th century, the concept of stem groups was introduced to cover evolutionary "aunts" and "cousins". A

Smithsonian page on ''Opabinia'', with photo of Burgess Shale fossil

{{Taxonbar, from=Q50570 Dinocaridida Cambrian arthropods Burgess Shale fossils Taxa named by Charles Doolittle Walcott Fossil taxa described in 1912 Cambrian genus extinctions

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

, stem group marine arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

found in the Middle Cambrian

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek (di ...

Burgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fos ...

Lagerstätte

A Fossil-Lagerstätte (, from ''Lager'' 'storage, lair' '' Stätte'' 'place'; plural ''Lagerstätten'') is a sedimentary deposit that preserves an exceptionally high amount of palaeontological information. ''Konzentrat-Lagerstätten'' preserv ...

(505 million years ago) of British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

. ''Opabinia'' was a soft-bodied animal, measuring up to 7 cm in body length, and had a segmented trunk with flaps along its sides and a fan-shaped tail. The head showed unusual features: five eye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

s, a mouth under the head and facing backwards, and a clawed proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular arthropod mouthparts, mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a pr ...

that most likely passed food to its mouth. ''Opabinia'' lived on the seafloor, using the proboscis to seek out small, soft food. Free abstract at Fewer than twenty good specimens have been described; 3 specimens of ''Opabinia'' are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they constitute less than 0.1% of the community.

When the first thorough examination of ''Opabinia'' in 1975 revealed its unusual features, it was thought to be unrelated to any known phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

, or perhaps a relative of arthropod and annelid

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

ancestors. However, later studies since late 1990s consistently support its affinity as a member of basal arthropods, alongside the closely related radiodonts (''Anomalocaris

''Anomalocaris'' (from Ancient Greek , meaning "unlike", and , meaning "shrimp", with the intended meaning "unlike other shrimp") is an extinct genus of radiodont, an order of early-diverging stem-group marine arthropods.

It is best known fro ...

'' and relatives) and gilled lobopodians (''Kerygmachela

''Kerygmachela kierkegaardi'' is a Kerygmachelidae, kerygmachelid Lobopodia#Gilled lobopodians, gilled lobopodian from the Cambrian Stage 3 aged Sirius Passet Lagerstätte in northern Greenland. Its anatomy strongly suggests that it, along with i ...

'' and '' Pambdelurion'').

In the 1970s, there was an ongoing debate about whether multi-celled animals appeared suddenly during the Early Cambrian, in an event called the Cambrian explosion, or had arisen earlier but without leaving fossils. At first ''Opabinia'' was regarded as strong evidence for the "explosive" hypothesis. Later the discovery of a whole series of similar lobopodian animals, some with closer resemblances to arthropods, and the development of the idea of stem groups, suggested that the Early Cambrian was a time of relatively fast evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

, but one that could be understood without assuming any unique evolutionary processes.

History of discovery

In 1911, Charles Doolittle Walcott found in theBurgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fos ...

nine almost complete fossils of ''Opabinia regalis'' and a few of what he classified as ''Opabinia ? media'', and published a description of all of these in 1912.WALCOTT, C. D. 1912Middle Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita and Merostomata

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 57: 145-228. The generic name is derived from Opabin pass between Mount Hungabee and Mount Biddle, southeast of Lake O'Hara, British Columbia,

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. In 1966–1967, Harry B. Whittington found another good specimen, and in 1975 he published a detailed description based on very thorough dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of ...

of some specimens and photographs of these specimens lit from a variety of angles. Whittington's analysis did not cover ''Opabinia ? media''; Walcott's specimens of this species could not be identified in his collection. In 1960 Russian paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

s described specimens they found in the Norilsk

Norilsk ( rus, Нори́льск, p=nɐˈrʲilʲsk) is a closed city in Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, located south of the western Taymyr Peninsula, around 90 km east of the Yenisei, Yenisey River and 1,500 km north of Krasnoyarsk. Norilsk is 300 ...

region of Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and labelled ''Opabinia norilica'', but these fossils were poorly preserved, and Whittington did not feel they provided enough information to be classified as members of the genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

''Opabinia''.

Occurrence

All the recognized ''Opabinia'' specimens found so far come from the " Phyllopod bed" of the Burgess Shale, in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia. In 1997, Briggs and Nedin reported fromSouth Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

Emu Bay Shale

The Emu Bay Shale is a Formation (stratigraphy), geological formation in Emu Bay, South Australia, containing a major Konservat-Lagerstätte (fossil beds with soft tissue preservation). It is one of two in the world containing Redlichiidan trilob ...

a new specimen of '' Myoscolex'' that was much better preserved than previous specimens, leading them to conclude that it was a close relative of ''Opabinia''—although this interpretation was later questioned by Dzik, who instead concluded that ''Myoscolex'' was an annelid

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

worm.

Morphology

proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular arthropod mouthparts, mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a pr ...

, whose total length was about one-third that of the body, and projected down from under the head. The proboscis was striated like a vacuum cleaner

A vacuum cleaner, also known simply as a vacuum, is a device that uses suction, and often agitation, in order to remove dirt and other debris from carpets, hard floors, and other surfaces.

The dirt is collected into a dust bag or a plastic bin. ...

's hose and flexible, and it ended with a claw-like structure whose terminal edges bore 5 spines that projected inwards and forwards. The bilateral symmetry and lateral (instead of vertical as reconstructed by Whittington 1975) arrangement of the claw suggest it represents a pair of fused frontal appendages, comparable to those of radiodonts and gilled lobopodians. The head bore five stalked eyes: two near the front and fairly close to the middle of the head, pointing upwards and forwards; two larger eyes with longer stalks near the rear and outer edges of the head, pointing upwards and sideways; and a single eye between the larger pair of stalked eyes, pointing upwards. It has been assumed that the eyes were all compound, like other arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s' lateral eyes, but this reconstruction, which is not backed up by any evidence, is "somewhat fanciful". The mouth was under the head, behind the proboscis, and pointed ''backwards'', so that the digestive tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

formed a U-bend on its way towards the rear of the animal. The proboscis appears to have been sufficiently long and flexible to reach the mouth.

The main part of the body was typically about wide and had 15 segments, on each of which there were pairs of flaps (lobes) pointing downwards and outwards. The flaps overlapped so that the front of each was covered by the rear edge of the one ahead of it. The body ended with what looked like a single conical segment bearing three pairs of overlapping tail fan blades that pointed up and out, forming a tail like a V-shaped double fan.

Interpretations of other features of ''Opabinia'' fossils differ. Since the animals did not have mineralized armor nor even tough organic exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

s like those of other arthropods, their bodies were flattened as they were buried and fossilized, and smaller or internal features appear as markings within the outlines of the fossils.

A: Whittington (1975), B: Bergström (1986), C: Budd (1996), D: Zhang & Briggs (2007), E: Budd & Daley (2011) File:20210807 Opabinia regalis trunk cross section.png, ''Opabinia'' cross-section based on Budd and Daley (2011)

Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (

Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (diverticula

In medicine or biology, a diverticulum is an outpouching of a hollow (or a fluid-filled) structure in the body. Depending upon which layers of the structure are involved, diverticula are described as being either true or false.

In medicine, t ...

). Chen ''et al.'' (1994) interpreted them as contained within the lobes along the sides. Budd (1996) thought the "triangles" were too wide to fit within ''Opabinia''s slender body, and that cross-section

Cross section may refer to:

* Cross section (geometry)

** Cross-sectional views in architecture and engineering 3D

* Cross section (geology)

* Cross section (electronics)

* Radar cross section, measure of detectability

* Cross section (physics)

...

views showed they were attached separately from and lower than the lobes, and extended below the body. He later found specimens that appeared to preserve the legs' exterior cuticle. He therefore interpreted the "triangles" as short, fleshy, conical legs (lobopods). He also found small mineralized patches at the tips of some, and interpreted these as claws. Under this reconstruction, the gill-bearing flap and lobopod were homologized to the outer gill branch and inner leg branch of arthropod biramous

The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip, ...

limbs seen in '' Marrella'', trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinction, extinct marine arthropods that form the class (biology), class Trilobita. One of the earliest groups of arthropods to appear in the fossil record, trilobites were among the most succ ...

s, and crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s. Zhang and Briggs (2007) analyzed the chemical composition of the "triangles", and concluded that they had the same composition as the gut, and therefore agreed with Whittington that they were part of the digestive system. Instead they regarded ''Opabinia''s lobe+gill arrangement as an early form of the arthropod limbs before it split into a biramous structure. However, this similar chemical composition is not only associated with the digestive tract; Budd and Daley (2011) suggest that it represents mineralization forming within fluid-filled cavities within the body, which is consistent with hollow lobopods as seen in unequivocal lobopodian fossils. They also clarify that the gut diverticula of ''Opabinia'' are series of circular gut glands individualized from the "triangles". While they agreed on the absence of terminal claws, the presence of lobopods in ''Opabinia'' remain as a plausible interpretation.

Lifestyle

The way in which theBurgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fos ...

animals were buried, by a mudslide or a sediment-laden current that acted as a sandstorm, suggests they lived on the surface of the seafloor. ''Opabinia'' probably used its proboscis to search the sediment for food particles and pass them to its mouth. Since there is no sign of anything that might function as jaws, its food was presumably small and soft. The paired gut diverticula

In medicine or biology, a diverticulum is an outpouching of a hollow (or a fluid-filled) structure in the body. Depending upon which layers of the structure are involved, diverticula are described as being either true or false.

In medicine, t ...

may increase the efficiency of food digestion and intake of nutrition. Whittington (1975) believing that ''Opabinia'' had no legs, thought that it crawled on its lobes and that it could also have swum slowly by flapping the lobes, especially if it timed the movements to create a wave

In physics, mathematics, engineering, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance (change from List of types of equilibrium, equilibrium) of one or more quantities. ''Periodic waves'' oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium ...

with the metachronal movement of its lobes. On the other hand, he thought the body was not flexible enough to allow fish-like undulations of the whole body.

Classification

Considering how paleontologists' reconstructions of ''Opabinia'' differ, it is not surprising that the animal's classification was highly debated during the 20th century. Charles Doolittle Walcott, the original describer, considered it to be an anostracancrustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

in 1912. The idea was followed by G. Evelyn Hutchinson in 1930, providing the first reconstruction of ''Opabinia'' as an anostracan swimming upside down. Alberto Simonetta provided a new reconstruction of ''Opabinia'' in 1970 very different to those of Hutchinson's, with lots of arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

features (''e.g. ,'' dorsal exoskeleton and jointed limbs) which are reminiscent of '' Yohoia'' and '' Leanchoilia''. Leif Størmer, following earlier work by Percy Raymond, thought that ''Opabinia'' belonged to the so-called "trilobitoids" (trilobites

Trilobites (; meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. One of the earliest groups of arthropods to appear in the fossil record, trilobites were among the most successful of all early animals, ...

and similar taxa). After his thorough analysis Harry B. Whittington concluded that ''Opabinia'' was not arthropod in 1975, as he found no evidence for arthropodan jointed limbs, and that nothing like the flexible, probably fluid-filled, proboscis was known in arthropods. Although he left ''Opabinias classification above the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

level open, the annulated but not articulated body and the unusual lateral flaps with gills persuaded him that it may have been a representative of the ancestral stock from the origin of annelid

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

s and arthropods, two distinct animal phyla ( Lophotrochozoan and Ecdysozoan, respectively) which were still thought to be close relatives (united under Articulata) at that time.

In 1985, Derek Briggs

Derek Ernest Gilmor Briggs (born 10 January 1950) is an Irish palaeontologist and taphonomist based at Yale University. Briggs is one of three palaeontologists, along with Harry Blackmore Whittington and Simon Conway Morris, who were key in ...

and Whittington published a major redescription of ''Anomalocaris

''Anomalocaris'' (from Ancient Greek , meaning "unlike", and , meaning "shrimp", with the intended meaning "unlike other shrimp") is an extinct genus of radiodont, an order of early-diverging stem-group marine arthropods.

It is best known fro ...

'', also from the Burgess Shale. Soon after that, Swedish palaeontologist Jan Bergström, noting in 1986 the similarity of ''Anomalocaris'' and ''Opabinia'', suggested that the two animals were related, as they shared numerous features (''e.g.,'' lateral flaps, gill blades, stalked eyes, and specialized frontal appendages). He classified them as primitive arthropods, although he considered that arthropods are not a single phylum.

In 1996, Graham Budd found what he considered evidence of short, un-jointed legs in ''Opabinia''. His examination of the gilled lobopodian ''Kerygmachela

''Kerygmachela kierkegaardi'' is a Kerygmachelidae, kerygmachelid Lobopodia#Gilled lobopodians, gilled lobopodian from the Cambrian Stage 3 aged Sirius Passet Lagerstätte in northern Greenland. Its anatomy strongly suggests that it, along with i ...

'' from the Sirius Passet lagerstätte

A Fossil-Lagerstätte (, from ''Lager'' 'storage, lair' '' Stätte'' 'place'; plural ''Lagerstätten'') is a sedimentary deposit that preserves an exceptionally high amount of palaeontological information. ''Konzentrat-Lagerstätten'' preserv ...

, about and over 10M years older than the Burgess Shale, convinced him that this specimen had similar legs. He considered the legs of these two genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

very similar to those of the Burgess Shale lobopodian '' Aysheaia'' and the modern onychophora

Onychophora (from , , "claws"; and , , "to carry"), commonly known as velvet worms (for their velvety texture and somewhat wormlike appearance) or more ambiguously as peripatus (after the first described genus, ''Peripatus''), is a phylum of el ...

ns (velvet worms), which are regarded as the bearers of numerous ancestral traits shared by the ancestors of arthropods. After examining several sets of features shared by these and similar lobopodians he drew up a "broad-scale reconstruction of the arthropod stem-group", ''i.e.,'' of arthropods and what he considered to be their evolutionary basal members. One striking feature of this family tree is that modern tardigrade

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who called them . In 1776, th ...

s (water bears) may be ''Opabinia'evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

ary relatives. On the other hand, Hou ''et al.'' (1995, 2006) suggested ''Opabinia'' is a member of unusual cycloneuralian worms with convergent arthropod features.

Although Zhang and Briggs (2007) disagreed with Budd's diagnosis that ''Opabinia''s "triangles" were legs, the resemblance they saw between ''Opabinia''s lobe+gill arrangement and arthropods' biramous

The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip, ...

limbs led them to conclude that ''Opabinia'' was very closely related to arthropods. In fact they presented a family tree very similar to Budd's except that theirs did not mention tardigrades. Regardless of the different morphological interpretations, all major restudies since 1980s similarly concluded that the resemblance between ''Opabinia'' and arthropods (''e.g.,'' stalked eyes, dorsal segmentation, posterior mouth, fused appendages, gill-like limb branches) are taxonomically significant.

Since the 2010s, the suggested close relationship between ''Opabinia'' and tardigrades/cycloneuralians is no longer supported, while the affinity of ''Opabinia'' as a stem-group arthropod alongside Radiodonta

Radiodonta is an extinct Order (biology), order of stem-group arthropods that was successful worldwide during the Cambrian period. Radiodonts are distinguished by their distinctive frontal appendages, which are morphologically diverse and were u ...

(a clade that includes ''Anomalocaris

''Anomalocaris'' (from Ancient Greek , meaning "unlike", and , meaning "shrimp", with the intended meaning "unlike other shrimp") is an extinct genus of radiodont, an order of early-diverging stem-group marine arthropods.

It is best known fro ...

'' and its relatives) and gilled lobopodians is widely accepted, as consistently shown by multiple phylogenetic analyses, as well as new discoveries such as the presence of arthropod-like gut glands and the intermediate taxon '' Kylinxia''.

In 2022

The year began with another wave in the COVID-19 pandemic, with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant, Omicron spreading rapidly and becoming the dominant variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus worldwide. Tracking a decrease in cases and deaths, 2022 saw ...

, Paleontologists described a similar looking animal which was discovered in Cambrian-aged rocks of Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

. The fossil was named '' Utaurora comosa,'' and was found within the Wheeler Shale. The stem-arthropod was actually first described in 2008, but at the time it was originally considered a specimen of ''Anomalocaris.'' This discovery could suggest there were other animals that looked like ''Opabinia,'' and its family may have been more diverse.

Theoretical significance

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s. Preston Cloud argued in 1948 and 1968 that the process was "explosive", and in the early 1970s Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ...

developed their theory of punctuated equilibrium

In evolutionary biology, punctuated equilibrium (also called punctuated equilibria) is a Scientific theory, theory that proposes that once a species appears in the fossil record, the population will become stable, showing little evolution, evol ...

, which views evolution as long intervals of near-stasis "punctuated" by short periods of rapid change. On the other hand, around the same time Wyatt Durham and Martin Glaessner both argued that the animal kingdom had a long Proterozoic

The Proterozoic ( ) is the third of the four geologic eons of Earth's history, spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8 Mya, and is the longest eon of Earth's geologic time scale. It is preceded by the Archean and followed by the Phanerozo ...

history that was hidden by the lack of fossils. Whittington (1975) concluded that ''Opabinia'', and other taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

such as '' Marrella'' and '' Yohoia'', cannot be accommodated in modern groups. This was one of the primary reasons why Gould in his book on the Burgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fos ...

, '' Wonderful Life'', considered that Early Cambrian life was much more disparate and "experimental" than any later set of animals and that the Cambrian explosion was a truly dramatic event, possibly driven by unusual evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

ary mechanisms. He regarded ''Opabinia'' as so important to understanding this phenomenon that he wanted to call his book ''Homage to Opabinia''.

However, other discoveries and analyses soon followed, revealing similar-looking animals such as ''Anomalocaris

''Anomalocaris'' (from Ancient Greek , meaning "unlike", and , meaning "shrimp", with the intended meaning "unlike other shrimp") is an extinct genus of radiodont, an order of early-diverging stem-group marine arthropods.

It is best known fro ...

'' from the Burgess Shale and ''Kerygmachela

''Kerygmachela kierkegaardi'' is a Kerygmachelidae, kerygmachelid Lobopodia#Gilled lobopodians, gilled lobopodian from the Cambrian Stage 3 aged Sirius Passet Lagerstätte in northern Greenland. Its anatomy strongly suggests that it, along with i ...

'' from Sirius Passet. Another Burgess Shale animal, ''Aysheaia'', was considered very similar to modern Onychophora

Onychophora (from , , "claws"; and , , "to carry"), commonly known as velvet worms (for their velvety texture and somewhat wormlike appearance) or more ambiguously as peripatus (after the first described genus, ''Peripatus''), is a phylum of el ...

, which are regarded as close relatives of arthropods. Paleontologists defined a group called lobopodia

Lobopodians are members of the informal group Lobopodia (), or the formally erected phylum Lobopoda Cavalier-Smith (1998). They are panarthropods with stubby legs called lobopods, a term which may also be used as a common name of this group as ...

ns to include fossil panarthropods that are thought to be close relatives of onychophorans, tardigrades and arthropods but lack jointed limbs. This group was later widely accepted as a paraphyletic grade that led to the origin of extant panarthropod phyla.

crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor ...

is a group of closely related living animals plus their last common ancestor plus all its descendants. A stem group contains offshoots from members of the lineage earlier than the last common ancestor of the crown group; it is a ''relative'' concept, for example tardigrade

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who called them . In 1776, th ...

s are living animals that form a crown group in their own right, but Budd (1996) regarded them also as being a stem group relative to the arthropods. Viewing strange-looking organisms like ''Opabinia'' in this way makes it possible to see that, while the Cambrian explosion was unusual, it can be understood in terms of normal evolutionary processes.

See also

* * * Paleobiota of the Burgess ShaleReferences

Further reading

* *External links

*Smithsonian page on ''Opabinia'', with photo of Burgess Shale fossil

{{Taxonbar, from=Q50570 Dinocaridida Cambrian arthropods Burgess Shale fossils Taxa named by Charles Doolittle Walcott Fossil taxa described in 1912 Cambrian genus extinctions