Olof Palme on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sven Olof Joachim Palme (; ; 30 January 1927 – 28 February 1986) was a Swedish politician and statesman who served as

In 1953, Palme was recruited by social democratic prime minister Tage Erlander to work in his secretariat. From 1955 he was a board member of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League and lectured at the Youth League College

In 1953, Palme was recruited by social democratic prime minister Tage Erlander to work in his secretariat. From 1955 he was a board member of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League and lectured at the Youth League College

On the international scene, Palme was a widely recognised political figure because of his:

* harsh and emotional criticism of the United States over the

On the international scene, Palme was a widely recognised political figure because of his:

* harsh and emotional criticism of the United States over the

Political violence was little-known in Sweden at the time, and Olof Palme often went about without a bodyguard. Close to midnight on 28 February 1986, he was walking home from a cinema with his wife Lisbeth Palme in the central Stockholm street Sveavägen when he was shot in the back at close range. A second shot grazed Lisbeth's back.

He was pronounced dead on arrival at the Sabbatsberg Hospital at 00:06 CET. Lisbeth survived without serious injuries.

Deputy Prime Minister

Political violence was little-known in Sweden at the time, and Olof Palme often went about without a bodyguard. Close to midnight on 28 February 1986, he was walking home from a cinema with his wife Lisbeth Palme in the central Stockholm street Sveavägen when he was shot in the back at close range. A second shot grazed Lisbeth's back.

He was pronounced dead on arrival at the Sabbatsberg Hospital at 00:06 CET. Lisbeth survived without serious injuries.

Deputy Prime Minister

* List of Olof Palme memorials, for a list of memorials and places named after Olof Palme.

* List of streets named after Olof Palme

* Olof Palme International Center

* Olof Palme Prize

*

* List of Olof Palme memorials, for a list of memorials and places named after Olof Palme.

* List of streets named after Olof Palme

* Olof Palme International Center

* Olof Palme Prize

*

online

* Marklund, Carl. "American Mirrors and Swedish Self-Portraits: American Images of Sweden and Swedish Public Diplomacy in the USA from Olof Palme to Ingvar Carlsson,” in ''Histories of Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding in the Nordic and Baltic Countries,'' ed. Louis Clerc, Nikolas Glover and Paul Jordan (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 172–94. * Ruin, Olof. (1991). "Three Swedish Prime Ministers: Tage Erlander, Olof Palme and Ingvar Carlsson." ''West European Politics'' 14 (3): pp. 58–82. * Tawat, Mahama. "The birth of Sweden’s multicultural policy. The impact of Olof Palme and his ideas." ''International Journal of Cultural Policy'' 25.4 (2019): 471-485. * Vivekanandan, Bhagavathi. ''Global Visions of Olof Palme, Bruno Kreisky and Willy Brandt: International Peace and Security, Co-operation, and Development'' (Springer, 2016). * Walters, Peter. "The Legacy of Olof Palme: The Condition of the Swedish Model." ''Government and Opposition'' 22.1 (1987): 64-77. * Wilsford, David, ed. ''Political leaders of contemporary Western Europe: a biographical dictionary'' (Greenwood, 1995) pp. 352–61. ; In Swedish * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Olof Palme Archives

Olof Palme Memorial Fund

Olof Palme International Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Palme, Olof 1927 births 1986 deaths Stockholm University alumni Kenyon College alumni Prime Ministers of Sweden Leaders of the Swedish Social Democratic Party Politicians from Stockholm Members of the Riksdag from the Social Democrats Assassinated Swedish politicians Deaths by firearm in Sweden People murdered in Sweden Assassinated heads of government Swedish socialist feminists Swedish people of Finnish descent Swedish atheists Swedish anti-communists Swedish feminists Swedish people of Baltic German descent Swedish people of Dutch descent Recipients of the Order of the White Lion Recipients of the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo Male feminists Male murder victims Members of the Första kammaren Members of the Andra kammaren Olof Swedish social democrats 20th-century atheists Recipients of the Four Freedoms Award Swedish Ministers for Communications Swedish Ministers for Education

Prime Minister of Sweden

The prime minister ( sv, statsminister ; literally translating to "Minister of State") is the head of government of Sweden. The prime minister and their cabinet (the government) exercise executive authority in the Kingdom of Sweden and are su ...

from 1969 to 1976 and 1982 to 1986. Palme led the Swedish Social Democratic Party from 1969 until his assassination in 1986.

A longtime protégé of Prime Minister Tage Erlander, he became Prime Minister of Sweden

The prime minister ( sv, statsminister ; literally translating to "Minister of State") is the head of government of Sweden. The prime minister and their cabinet (the government) exercise executive authority in the Kingdom of Sweden and are su ...

in 1969, heading a Privy Council Government. He left office after failing to form a government after the 1976 general election, which ended 40 years of unbroken rule by the Social Democratic Party. While Leader of the Opposition, he served as special mediator of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

in the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Counci ...

, and was President of the Nordic Council in 1979. He faced a second defeat in 1979, but he returned as Prime Minister after electoral victories in 1982 and 1985, and served until his death.

Palme was a pivotal and polarizing figure domestically as well as in international politics

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such a ...

from the 1960s onward. He was steadfast in his non-alignment policy towards the superpowers, accompanied by support for numerous liberation movements following decolonization including, most controversially, economic and vocal support for a number of Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

governments. He was the first Western head of government to visit Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

after its revolution, giving a speech in Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

praising contemporary Cuban revolutionaries.

Frequently a critic of Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and American foreign policy, he expressed his resistance to imperialist ambitions and authoritarian regimes, including those of Francisco Franco of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Augusto Pinochet of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

, Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and 1 ...

of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, António de Oliveira Salazar

António de Oliveira Salazar (, , ; 28 April 1889 – 27 July 1970) was a Portuguese dictator who served as President of the Council of Ministers from 1932 to 1968. Having come to power under the ("National Dictatorship"), he reframed the re ...

of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, Gustáv Husák of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, and most notably John Vorster and P. W. Botha of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

, denouncing apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

as a "particularly gruesome system." His 1972 condemnation of American bombings in Hanoi, comparing the bombings to a number of historical crimes including the bombing of Guernica

On 26 April 1937, the Basque town of Guernica (''Gernika'' in Basque) was aerial bombed during the Spanish Civil War. It was carried out at the behest of Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist faction by its allies, the Nazi German Luftwaffe ...

, the massacres of Oradour-sur-glane, Babi Yar, Katyn, Lidice and Sharpeville

Sharpeville (also spelled Sharpville) is a township situated between two large industrial cities, Vanderbijlpark and Vereeniging, in southern Gauteng, South Africa. Sharpeville is one of the oldest of six townships in the Vaal Triangle. It was ...

and the extermination of Jews and other groups at Treblinka, resulted in a temporary freeze in Sweden–United States relations.

Palme's assassination on a Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

street on 28 February 1986 was the first murder of a national leader in Sweden since Gustav III

Gustav III (29 March 1792), also called ''Gustavus III'', was King of Sweden from 1771 until his assassination in 1792. He was the eldest son of Adolf Frederick of Sweden and Queen Louisa Ulrika of Prussia.

Gustav was a vocal opponent of what ...

in 1792, and had a great impact across Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

. Local convict and addict Christer Pettersson was originally convicted of the murder in district court but was unanimously acquitted by the Svea Court of Appeal. On 10 June 2020, Swedish prosecutors held a press conference to announce that there was "reasonable evidence" that Stig Engström had killed Palme. As Engström had committed suicide in 2000, the authorities announced that the investigation into Palme's death was to be closed. The 2020 conclusion has faced widespread criticism from lawyers, police officers and journalists, decrying the evidence as only circumstantial, and – by the prosecutors' own admission – too weak to ensure a trial had the suspect been alive.

Early life

Palme was born into an upper class, conservativeLutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

family in the Östermalm

Östermalm (; "Eastern city-borough") is a 2.56 km2 large district in central Stockholm, Sweden. With 71,802 inhabitants, it is one of the most populous districts in Stockholm. It is an extremely expensive area, having the highest housing ...

district of Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

. The progenitor of the Palme family

{{Infobox family

, name = The Palme Family

, image =

, crest =

, caption =

, ethnicity =

, region = Sweden

, early_forms =

, origin =

, members = Olof Palme, Prime Minister of S ...

was skipper Palme Lydert of Ystad of either Dutch or German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

ancestry. His sons adopted the surname Palme. Many of the early Palmes were vicars and judges in Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous with Skån ...

. One branch of the family, of which Olof Palme was part, and which became more affluent, relocated to Kalmar; that branch is related to several other prominent Swedish families such as the Kreugers, von Sydows and the Wallenbergs. His father, (1886–1934), was a businessman, son of (1854–1934) and Swedish-speaking Finnish Baroness (1861–1959). Through her, Olof Palme claimed ancestry from King Johan III of Sweden, his father King Gustav Vasa of Sweden and King Frederick I of Denmark and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

. His mother, Elisabeth von Knieriem (1890–1972),Olof Ruin: ''Olof Palme.'' In: David Wilsford: ''Political Leaders of Contemporary Western Europe: A Biographical Dictionary.'' Greenwood Press, Westport, CT 1995 of the Knieriem family who originated from Quedlinburg, descended from Baltic German burghers and clergy and had arrived in Sweden from Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

as a refugee in 1915. Elisabeth's great-great-great grandfather Johann Melchior von Knieriem (1758–1817) had been ennobled by the Emperor Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first King of Congress Poland from 1815, and the Grand Duke of Finland from 1809 to his death. He was the eldest son of Emperor Paul I and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg.

The son o ...

in 1814. The von Knieriem family does not count as members of any of the Baltic knighthoods. Palme's father died when he was seven years old. Despite his background, his political orientation came to be influenced by Social Democratic attitudes. His travels in the Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

, as well as the United States, where he saw deep economic inequality

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of ...

and racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

, helped to develop these views.

A sickly child, Olof Palme received his education from private tutors. Even as a child he gained knowledge of two foreign languages — German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

. He studied at Sigtunaskolan Humanistiska Läroverket, one of Sweden's few residential high schools, and passed the university entrance examination with high marks at the age of 17. He was called up into the Army in January 1945 and did his compulsory military service

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day ...

at Svea Artillery Regiment between 1945 and 1947, becoming in 1956 a reserve officer with the rank of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the Artillery. After he was discharged from military service in March 1947, he enrolled at Stockholm University

Stockholm University ( sv, Stockholms universitet) is a public research university in Stockholm, Sweden, founded as a college in 1878, with university status since 1960. With over 33,000 students at four different faculties: law, humanities, ...

.

On a scholarship, he studied at Kenyon College

Kenyon College is a private liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio. It was founded in 1824 by Philander Chase. Kenyon College is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission.

Kenyon has 1,708 undergraduates enrolled. Its 1,000-acre campus is s ...

, a small liberal arts school in central Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

from 1947 to 1948, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degree. Inspired by radical debate in the student community, he wrote a critical essay on Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

's ''The Road to Serfdom

''The Road to Serfdom'' (German: ''Der Weg zur Knechtschaft'') is a book written between 1940 and 1943 by Austrian-British economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek. Since its publication in 1944, ''The Road to Serfdom'' has been popular among ...

''. Palme wrote his senior honour thesis on the United Auto Workers

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, better known as the United Auto Workers (UAW), is an American Labor unions in the United States, labor union that represents workers in the Un ...

union, led at the time by Walter Reuther. After graduation, he traveled throughout the country and eventually ended up in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, where his hero Reuther agreed to an interview which lasted several hours. In later years, Palme regularly remarked during his many subsequent American visits, that the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

had made him a socialist, a remark that often has caused confusion. Within the context of his American experience, it was not that Palme was repelled by what he found in America, but rather that he was inspired by it.

After hitchhiking through the U.S. and Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, he returned to Sweden to study law at Stockholm University

Stockholm University ( sv, Stockholms universitet) is a public research university in Stockholm, Sweden, founded as a college in 1878, with university status since 1960. With over 33,000 students at four different faculties: law, humanities, ...

. In 1949 he became a member of the Swedish Social Democratic Party. During his time at university, Palme became involved in student politics, working with the Swedish National Union of Students

The Swedish National Union of Students ( sv, Sveriges Förenade Studentkårer, SFS), is an umbrella organisation of students' unions at higher education facilities in Sweden. The organisation was founded in 1921. It has around 47 affiliated studen ...

. In 1951, he became a member of the social democratic student association in Stockholm, although it is asserted he did not attend their political meetings at the time. The following year he was elected President of the Swedish National Union of Students. As a student politician he concentrated on international affairs and travelled across Europe.

Palme attributed his becoming a social democrat to three major influences:

* In 1947, he attended a debate on taxes between the Social Democrat Ernst Wigforss

Ernst Johannes Wigforss (24 January 1881–2 January 1977) was a Swedish politician and linguist (dialectologist), mostly known as a prominent member of the Social Democratic Workers' Party and Swedish Minister of Finance. Wigforss became o ...

, the conservative Jarl Hjalmarson

Jarl Harald Hjalmarson (15 June 1904 – 26 November 1993) was the leader of the conservative Swedish Rightist Party (''Högerpartiet''), today known as the Moderate Party, between 1950 and 1961.

Born in Helsingborg, he was considered as a mo ...

and the liberal Elon Andersson.

* The time he spent in the United States in the 1940s made him realise how wide the class divide was in America, and the extent of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

against black people

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in ...

.

* A trip to Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

, specifically India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

in 1953 had opened his eyes to the consequences of colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their reli ...

and imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic powe ...

.

Palme was an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

.

Political career

Bommersvik

Bommersvik is a Union college ( sv, italic=yes, Förbundskola from Förbund meaning ''union'' or ''association'' and skola meaning ''school'' or ''college'') built by the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League (SSU) and is situated outside the mun ...

. He also was a member of the Worker's Educational Association.

In 1957 he was elected as a member of parliament (Swedish: ''riksdagsledamot'') represented Jönköping

Jönköping (, ) is a city in southern Sweden with 112,766 inhabitants (2022). Jönköping is situated on the southern shore of Sweden's second largest lake, Vättern, in the province of Småland.

The city is the seat of Jönköping Municipa ...

County in the directly elected Second Chamber (''Andra kammaren'') of the Riksdag. In the early 1960s Palme became a member of the Agency for International Assistance (NIB) and was in charge of inquiries into assistance to the developing countries and educational aid. In 1963, he became a member of the Cabinet as minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet ...

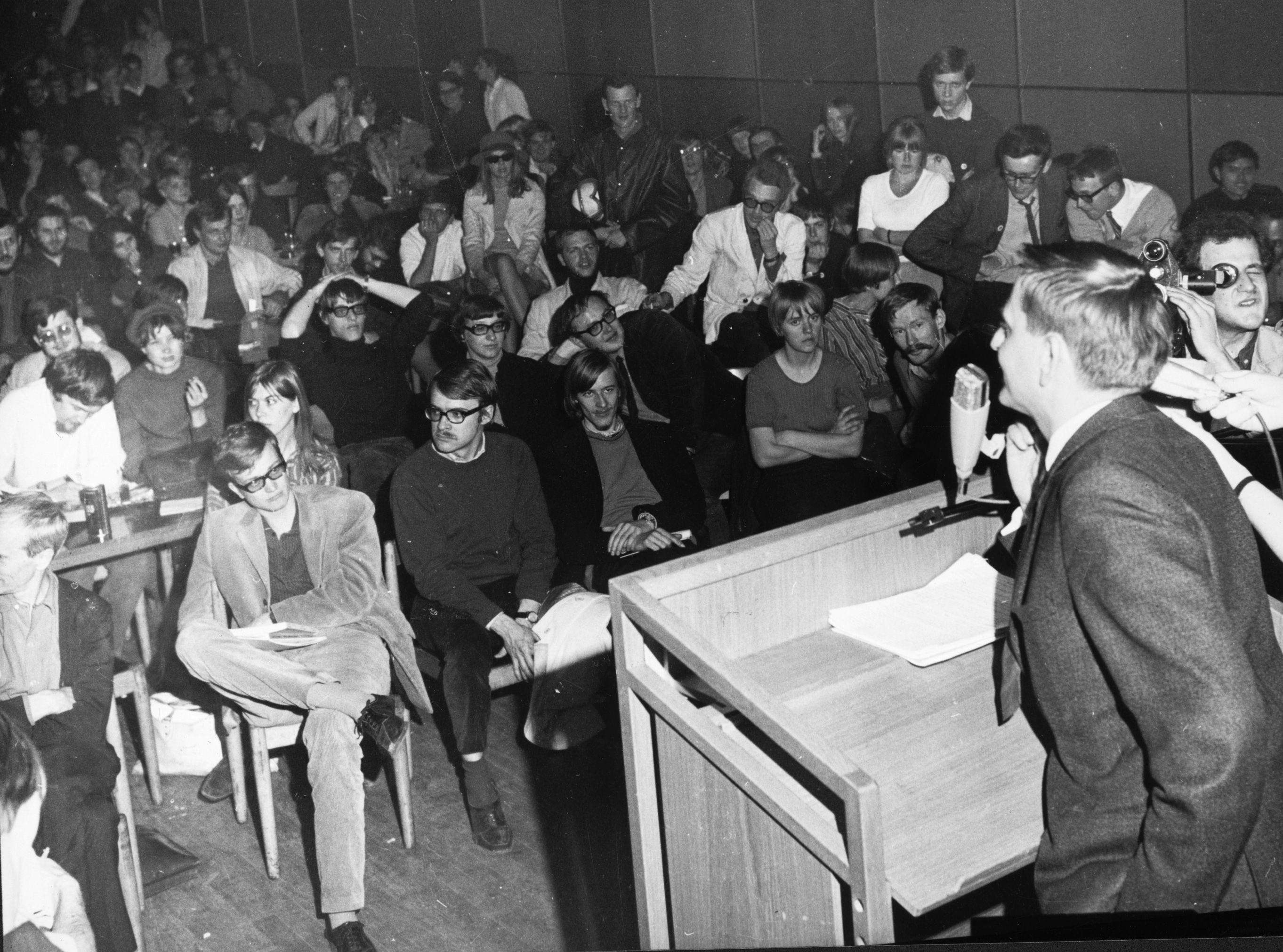

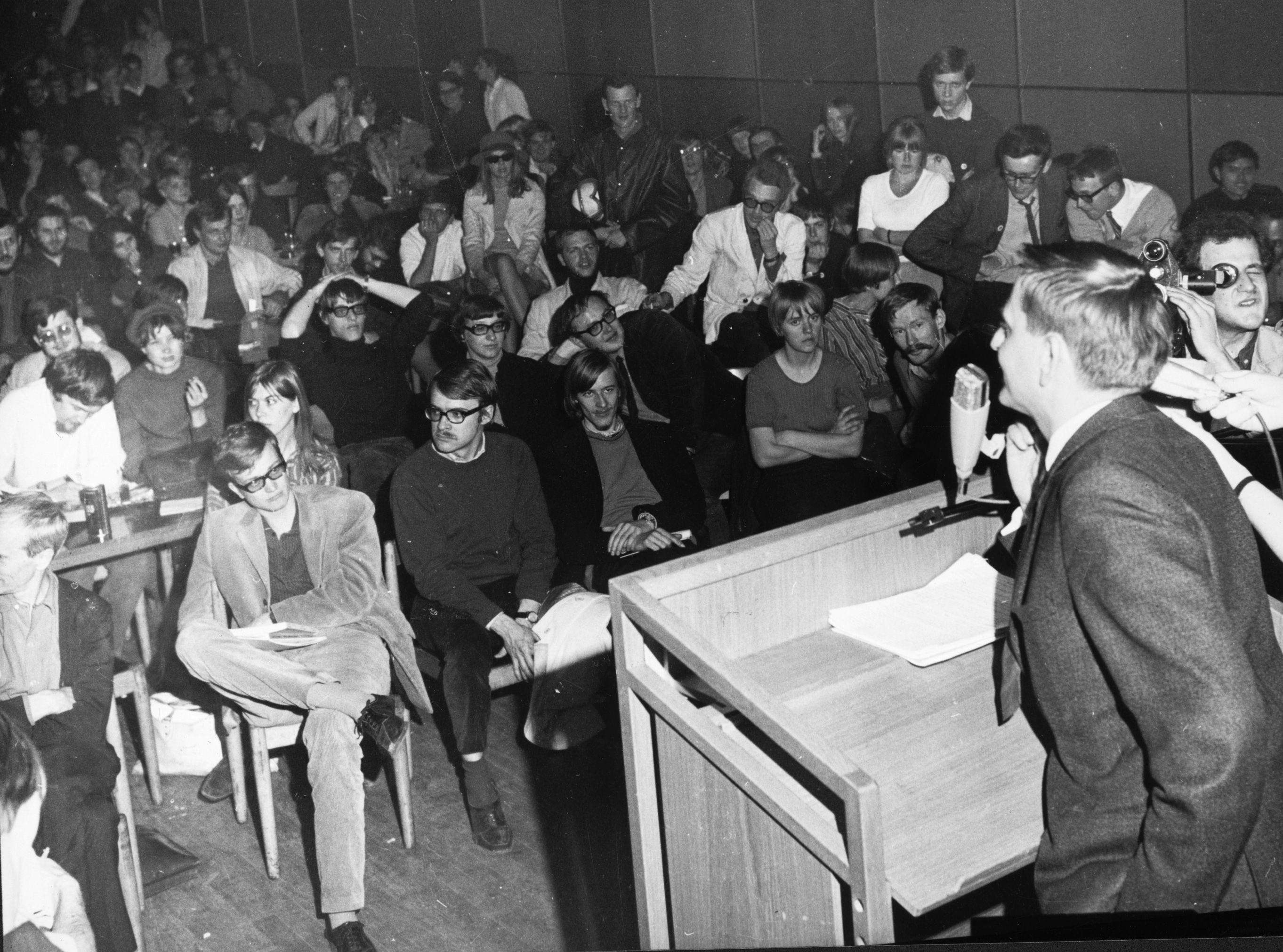

in the Cabinet Office, and retained his duties as a close political adviser to Prime Minister Tage Erlander. In 1965, he became Minister of Communications (Transport). One issue of special interest to him was the further development of radio and television, while ensuring their independence from commercial interests. In 1967 he became Minister of Education, and the following year, he was the target of strong criticism from left-wing students protesting against the government's plans for university reform. The protests culminated with the occupation of the Student Union Building in Stockholm; Palme came there and tried to comfort the students, urging them to use democratic methods for the pursuit of their cause. When party leader Tage Erlander stepped down in 1969, Palme was elected as the new leader by the Social Democratic party congress and succeeded Erlander as Prime Minister.

Palme was very popular among the left, but harshly detested by liberals and conservatives. This was due in part to his international activities, especially those directed against the US foreign policy, and in part to his aggressive and outspoken debating style.

Policies and views

As leader of a new generation of Swedish Social Democrats, Palme was often described as a "revolutionary reformist" and self-identified as a progressive. Domestically, his leftist views, especially the drive to expand labour union influence over business ownership, engendered a great deal of hostility from the organized business community. During the tenure of Palme, several major reforms in the Swedish constitution were carried out, such as orchestrating a switch frombicameralism

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single gr ...

to unicameralism

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

in 1971 and in 1975 replacing the 1809 Instrument of Government (at the time the oldest political constitution in the world after that of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

) with a new one officially establishing parliamentary democracy rather than ''de jure'' monarchic autocracy, abolishing the Cabinet meetings chaired by the King and stripping the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic ( constitutional monar ...

of all formal political powers.

His reforms on labour market included establishing a law which increased job security. In the Swedish 1973 general election, the Socialist-Communist and the Liberal-Conservative blocs got 175 places each in the Riksdag. The Palme cabinet continued to govern the country but several times they had to draw lots to decide on some issues, although most important issues were decided through concessional agreement. Tax rates also rose from being fairly low even by Western European standards to the highest levels in the Western world.

Under Palme's premiership tenure, matters concerned with child care

Child care, otherwise known as day care, is the care and supervision of a child or multiple children at a time, whose ages range from two weeks of age to 18 years. Although most parents spend a significant amount of time caring for their child(r ...

centers, social security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

, protection of the elderly, accident safety, and housing

Housing, or more generally, living spaces, refers to the construction and assigned usage of houses or buildings individually or collectively, for the purpose of shelter. Housing ensures that members of society have a place to live, whether ...

problems received special attention. Under Palme the public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

system in Sweden became efficient, with the infant mortality rate standing at 12 per 1,000 live births. An ambitious redistributive programme was carried out, with special help provided to the disabled, immigrants, the low paid, single-parent families, and the old.Socialists in the Recession: The Search for Solidarity by Giles Radice and Lisanne Radice The Swedish welfare state was significantly expanded from a position already one of the most far-reaching in the world during his time in office.Taxation, Wage Bargaining and Unemployment by Isabela Mares As noted by Isabela Mares, during the first half of the Seventies "the level of benefits provided by every subsystem of the welfare state improved significantly." Various policy changes increased the basic old-age pension replacement rate from 42% of the average wage in 1969 to 57%, while a health care reform carried out in 1974 integrated all health services and increased the minimum replacement rate from 64% to 90% of earnings. In 1974, supplementary unemployment assistance was established, providing benefits to those workers ineligible for existing benefits. In 1971, eligibility for invalidity pensions was extended with greater opportunities for employees over the age of 60. In 1974, universal dental insurance was introduced, and former maternity benefits were replaced by a parental allowance. In 1974, housing allowances for families with children were raised and these allowances were extended to other low-income groups.Growth to Limits: The Western European Welfare States Since World War II Volume 4 edited by Peter Flora Childcare centres were also expanded under Palme, and separate taxation of husband and wife introduced. Access to pensions for older workers in poor health was liberalised in 1970, and a disability pension was introduced for older unemployed workers in 1972.

The Palme cabinet was also active in the field of education, introducing such reforms as a system of loans and benefits for students, regional universities, and preschool for all children. Under a law of 1970, in the upper secondary school system "gymnasium," “fackskola" and vocational "yrkesskola" were integrated to form one school with 3 sectors (arts and social science, technical and natural sciences, economic and commercial). In 1975, a law was passed that established free admission to universities. A number of reforms were also carried out to enhance workers' rights. An employment protection Act of 1974 introduced rules regarding consultation with unions, notice periods, and grounds for dismissal, together with priority rules for dismissals and re-employment in case of redundancies. That same year, work-environment improvement grants were introduced and made available to modernising firms "conditional upon the presence of union-appointed 'safety stewards' to review the introduction of new technology with regard to the health and safety of workers." In 1976, an Act on co-determination at work was introduced that allowed unions to be consulted at various levels within companies before major changes were enforced that would affect employees, while management had to negotiate with labour for joint rights in all matters concerning organisation of work, hiring and firing, and key decisions affecting the workplace.

Palme's last government, elected during a time when Sweden's economy was in difficult shape, sought to pursue a "third way," designed to stimulate investment, production, and employment, having ruled out classical Keynesian policies as a result of the growing burden of foreign debt, together with the big balance of payments and budget deficits. This involved "equality of sacrifice," whereby wage restraint would be accompanied by increases in welfare provision and more progressive taxation. For instance, taxes on wealth, gifts, and inheritance were increased, while tax benefits to shareholders were either reduced or eliminated. In addition, various welfare cuts carried out before Olof's return to office were rescinded. The previous system of indexing pensions and other benefits was restored, the grant-in-aid scheme for municipal child care facilities was re-established, unemployment insurance was restored in full, and the so-called "no benefit days" for those drawing sickness benefits were cancelled. Increases were also made to both food subsidies and child allowances, while the employee investment funds (which represented a radical form of profit-sharing) were introduced.

In 1968, Palme was a driving force behind the release of the documentary '' Dom kallar oss mods'' ("They Call Us Misfits"). The controversial film, depicting two social outcasts, was scheduled to be released in an edited form but Palme thought the material was too socially important to be cut.

An outspoken supporter of gender equality, Palme sparked interest for women's rights issues by attending a World Women's Conference in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. He also made a feminist speech called "The Emancipation of Man" at a meeting of the Woman's National Democratic Club

The Woman's National Democratic Club (WNDC) is a membership organization based in Washington, D.C., Washington, DC, that offers programs, events, and activities that encourage political action and civic engagement.

The WNDC was founded in 1922 ...

on 8 June 1970; this speech was later published in 1972.

As a forerunner in green politics

Green politics, or ecopolitics, is a political ideology that aims to foster an ecologically sustainable society often, but not always, rooted in environmentalism, nonviolence, social justice and grassroots democracy. Wall 2010. p. 12-13. It be ...

, Palme was a firm believer in nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

as a necessary form of energy, at least for a transitional period to curb the influence of fossil fuel

A fossil fuel is a hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the remains of dead plants and animals that is extracted and burned as a fuel. The main fossil fuels are coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels ma ...

. His intervention in Sweden's 1980 referendum on the future of nuclear power is often pinpointed by opponents of nuclear power as saving it. As of 2011, nuclear power remains one of the most important sources of energy in Sweden, much attributed to Palme's actions.

SovietSwedish bilateral relations were tested during Palme's second span of time as prime minister in the 1980s, in particular, owing to reports of incursions by Soviet submarines into Swedish territorial waters.

On the international scene, Palme was a widely recognised political figure because of his:

* harsh and emotional criticism of the United States over the

On the international scene, Palme was a widely recognised political figure because of his:

* harsh and emotional criticism of the United States over the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

;

* vocal opposition to the crushing of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First ...

by the Soviet Union;

* criticism of European Communist regimes, including labeling the Husák regime as "The Cattle of Dictatorship" (Swedish: "Diktaturens kreatur") in 1975;

* campaigning against nuclear weapons proliferation;

* criticism of the Franco Regime

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spa ...

in Spain, calling the regime "goddamn murderers" (Swedish: "satans mördare"; see Swedish profanity) after its execution of ETA

Eta (uppercase , lowercase ; grc, ἦτα ''ē̂ta'' or ell, ήτα ''ita'' ) is the seventh letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the close front unrounded vowel . Originally denoting the voiceless glottal fricative in most dialects, ...

and FRAP militants in September 1975;

* opposition to apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

, branding it as "a particularly gruesome system", and support for economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they ...

against South Africa;

* support, both political and financial, for the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

(ANC), the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the POLISARIO Front;

* visiting Fidel Castro's Cuba in 1975, during which he denounced Fulgencio Batista's government and praised contemporary Cuban

Cuban may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Cuba, a country in the Caribbean

* Cubans, people from Cuba, or of Cuban descent

** Cuban exile, a person who left Cuba for political reasons, or a descendant thereof

* Cuban citizen, a pers ...

revolutionaries;

* strong criticism of the Pinochet regime in Chile;

* support, both political and financial, for the FMLN-FDR in El Salvador and the FSLN

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto C� ...

in Nicaragua; and,

* role as a mediator in the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Counci ...

.

All of this ensured that Palme had many opponents as well as many friends abroad.

On 21 February 1968, Palme (then Minister of Education) participated in a protest in Stockholm against U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam together with the North Vietnamese ambassador to the Soviet Union, Nguyễn Thọ Chân. The protest was organized by the Swedish Committee for Vietnam and Palme and Nguyen were both invited as speakers. As a result of this, the U.S. recalled its Ambassador from Sweden and Palme was fiercely criticised by the opposition for his participation in the protest.

On 23 December 1972, Palme (then Prime Minister) made a speech on Swedish national radio where he compared the ongoing U.S. bombings of Hanoi to historical atrocities, namely the bombing of Guernica

On 26 April 1937, the Basque town of Guernica (''Gernika'' in Basque) was aerial bombed during the Spanish Civil War. It was carried out at the behest of Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist faction by its allies, the Nazi German Luftwaffe ...

, the massacres of Oradour-sur-Glane, Babi Yar, Katyn, Lidice and Sharpeville

Sharpeville (also spelled Sharpville) is a township situated between two large industrial cities, Vanderbijlpark and Vereeniging, in southern Gauteng, South Africa. Sharpeville is one of the oldest of six townships in the Vaal Triangle. It was ...

, and the extermination of Jews and other groups at Treblinka. The US government called the comparison a "gross insult" and once again decided to freeze its diplomatic relations with Sweden (this time the freeze lasted for over a year).

In response to Palme's remarks in a meeting with the US ambassador to Sweden ahead of the Socialist International Meeting in Helsingør in January 1976, Henry Kissinger, then United States Secretary of State, asked the US ambassador to "convey my personal appreciation to Palme for his frank presentation".

Assassination

Political violence was little-known in Sweden at the time, and Olof Palme often went about without a bodyguard. Close to midnight on 28 February 1986, he was walking home from a cinema with his wife Lisbeth Palme in the central Stockholm street Sveavägen when he was shot in the back at close range. A second shot grazed Lisbeth's back.

He was pronounced dead on arrival at the Sabbatsberg Hospital at 00:06 CET. Lisbeth survived without serious injuries.

Deputy Prime Minister

Political violence was little-known in Sweden at the time, and Olof Palme often went about without a bodyguard. Close to midnight on 28 February 1986, he was walking home from a cinema with his wife Lisbeth Palme in the central Stockholm street Sveavägen when he was shot in the back at close range. A second shot grazed Lisbeth's back.

He was pronounced dead on arrival at the Sabbatsberg Hospital at 00:06 CET. Lisbeth survived without serious injuries.

Deputy Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson

Gösta Ingvar Carlsson (born 9 November 1934) is a Swedish politician who twice served as Prime Minister of Sweden, first from 1986 to 1991 and again from 1994 to 1996. He was leader of the Swedish Social Democratic Party from 1986 to 1996. H ...

immediately assumed the duties of Prime Minister, a post he retained until 1991 (and then again in 19941996). He also took over the leadership of the Social Democratic Party, which he held until 1996.

Two years later, Christer Pettersson (d. 2004), a murderer, small-time criminal and drug addict, was convicted of Palme's murder, but his conviction was overturned. Another suspect, Victor Gunnarsson, emigrated to the United States, where he was the victim of an unrelated murder in 1993. The assassination remained unsolved. A third and fourth suspect popularly referred to as " The Skandia Man" and '' GH'', after their working place at the Skandia

Skandia is a financial services corporation in Sweden.

History

Skandia started out as a Swedish insurance company in 1855. Today the brand operates in Europe, Latin America, and Asia. Skandia also operates an internet bank called Skan ...

building next to the crime scene, and police investigation number ("H" representing the eight letter, i.e. "Suspect Profile No. 8"), committed suicide in 2000 and 2008 respectively. Both fit the suspect profile vaguely, and owned firearms. GH was a long-time suspect partly because he had self-described financial motives, and owned the only registered .357 Magnum

The .357 Smith & Wesson Magnum, .357 S&W Magnum, .357 Magnum, or 9×33mmR as it is known in unofficial metric designation, is a smokeless powder cartridge with a bullet diameter. It was created by Elmer Keith, Phillip B. Sharpe, and Douglas B. ...

in the Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

vicinity not tested and ruled out by authorities, which as yet has not been recovered.

On 18 March 2020, Swedish investigators met in Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foothi ...

with members of South African intelligence agencies to discuss the case. The South Africans handed over their file from 1986 to their Swedish colleagues. Göran Björkdahl, a Swedish diplomat, had done independent research on Palme's assassination, leading to South Africa's apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

regime. Major General Chris Thirion, who headed the military intelligence of South Africa during the final years of apartheid rule, had told Björkdahl in 2015 that he believed South Africa was behind Palme's murder. Swedish investigators announced that they would reveal new information and close the case on 10 June 2020. Earlier remarks by lead investigator Krister Petersson that "there might not be a prosecution" have led commentators to believe that the suspect is dead.

On 10 June 2020, Swedish prosecutors stated publicly that they knew who had killed Palme and named Stig Engström, also known as "Skandia Man", as the assassin. Engström was one of about twenty people who had claimed to witness the assassination and was later identified as a potential suspect by Swedish writers Lars Larsson and Thomas Pettersson. Given that Engström had committed suicide in 2000, the authorities also announced that the investigation into Palme's death was to be closed.

Some politicians and journalists in Turkey relate the assassination of Palme to PKK since he was the first in Europe to designate PKK as terrorist organisation.

See also

* List of Olof Palme memorials, for a list of memorials and places named after Olof Palme.

* List of streets named after Olof Palme

* Olof Palme International Center

* Olof Palme Prize

*

* List of Olof Palme memorials, for a list of memorials and places named after Olof Palme.

* List of streets named after Olof Palme

* Olof Palme International Center

* Olof Palme Prize

* List of peace activists

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usually work wi ...

* Sweden bashing

* Anna Lindh

Ylva Anna Maria Lindh (19 June 1957 – 11 September 2003) was a Swedish Social Democratic politician and lawyer who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1998 until her death. She was also a Member of the Riksdag (member of parliament) ...

* Bernt Carlsson

* Folke Bernadotte

* Caleb J. Anderson

* IB affair

The IB affair ( sv, IB-affären) was the exposure of illegal surveillance operations by the IB secret Swedish intelligence agency within the Swedish Armed Forces. The two main purposes of the agency were to handle liaison with foreign intelli ...

, a political scandal involving Palme.

* Ebbe Carlsson affair

The Ebbe Carlsson affair ( sv, Ebbe Carlsson-affären) was a major political scandal in Sweden occurring during mid-1988. The affair came to public knowledge on 1 June 1988, when the evening newspaper ''Expressen'' revealed that Ebbe Carlsson, a j ...

, a political scandal concerning non-official inquiries into the murder.

Notes

Further reading

* Bondeson, Jan. ''Blood on the snow: The killing of Olof Palme'' (Cornell University Press, 2005). * Derfler, Leslie. ''The Fall and Rise of Political Leaders: Olof Palme, Olusegun Obasanjo, and Indira Gandhi'' (Springer, 2011). * Ekengren, Ann-Marie. (2011). "How Ideas Influence Decision-Making: Olof Palme and Swedish Foreign Policy, 1965–1975." ''Scandinavian Journal of History'' 36 (2): pp. 117–134. * Esaiasson, Peter, and Donald Granberg. (1996). "Attitudes towards a fallen leader: Evaluations of Olof Palme before and after the assassination." ''British Journal of Political Science''. 26#3 pp. 429–439. * Marklund, Carl. "From ‘False’ Neutrality to ‘True’ Socialism: Unofficial US ‘Sweden-bashing’ During the Later Palme Years, 1973–1986." ''Journal of Transnational American Studies'' 7.1 (2016): 1-18online

* Marklund, Carl. "American Mirrors and Swedish Self-Portraits: American Images of Sweden and Swedish Public Diplomacy in the USA from Olof Palme to Ingvar Carlsson,” in ''Histories of Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding in the Nordic and Baltic Countries,'' ed. Louis Clerc, Nikolas Glover and Paul Jordan (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 172–94. * Ruin, Olof. (1991). "Three Swedish Prime Ministers: Tage Erlander, Olof Palme and Ingvar Carlsson." ''West European Politics'' 14 (3): pp. 58–82. * Tawat, Mahama. "The birth of Sweden’s multicultural policy. The impact of Olof Palme and his ideas." ''International Journal of Cultural Policy'' 25.4 (2019): 471-485. * Vivekanandan, Bhagavathi. ''Global Visions of Olof Palme, Bruno Kreisky and Willy Brandt: International Peace and Security, Co-operation, and Development'' (Springer, 2016). * Walters, Peter. "The Legacy of Olof Palme: The Condition of the Swedish Model." ''Government and Opposition'' 22.1 (1987): 64-77. * Wilsford, David, ed. ''Political leaders of contemporary Western Europe: a biographical dictionary'' (Greenwood, 1995) pp. 352–61. ; In Swedish * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

Olof Palme Archives

Olof Palme Memorial Fund

Olof Palme International Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Palme, Olof 1927 births 1986 deaths Stockholm University alumni Kenyon College alumni Prime Ministers of Sweden Leaders of the Swedish Social Democratic Party Politicians from Stockholm Members of the Riksdag from the Social Democrats Assassinated Swedish politicians Deaths by firearm in Sweden People murdered in Sweden Assassinated heads of government Swedish socialist feminists Swedish people of Finnish descent Swedish atheists Swedish anti-communists Swedish feminists Swedish people of Baltic German descent Swedish people of Dutch descent Recipients of the Order of the White Lion Recipients of the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo Male feminists Male murder victims Members of the Första kammaren Members of the Andra kammaren Olof Swedish social democrats 20th-century atheists Recipients of the Four Freedoms Award Swedish Ministers for Communications Swedish Ministers for Education