Oklahoma Panhandle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Oklahoma Panhandle (formerly called No Man's Land, the Public Land Strip, the Neutral Strip, or Cimarron Territory) is a salient in the extreme northwestern region of the U.S. state of

The Panhandle, long and wide, is bordered by

The Panhandle, long and wide, is bordered by

What is now the Oklahoma Panhandle has been occupied for millennia. The Paleo-Indian people of the region were part of the Beaver River complex. A Paleo-Indian encampment, the Bull Creek site, dates back to approximately 8450 BCE, and the Badger Hole site dates to circa 8400 BCE.

Shortly before the arrival of European explorers, the Panhandle was home to Southern Plains villagers. From 1200 to 1500, the semi-sedentary Panhandle culture peoples, including the

What is now the Oklahoma Panhandle has been occupied for millennia. The Paleo-Indian people of the region were part of the Beaver River complex. A Paleo-Indian encampment, the Bull Creek site, dates back to approximately 8450 BCE, and the Badger Hole site dates to circa 8400 BCE.

Shortly before the arrival of European explorers, the Panhandle was home to Southern Plains villagers. From 1200 to 1500, the semi-sedentary Panhandle culture peoples, including the

/ref> The Cimarron Cutoff for the

Accessed April 13, 2013. In 1886,

, United States Census Bureau. (accessed September 3, 2013) The racial makeup of the region was 80.26%

Goins, Charles Robert and Danney Goble. "The Oklahoma Panhandle, 2000." In: ''Historical Atlas of Oklahoma''.

Available on Google Books.p. 206. Retrieved January 19. 2014.

Cimarron Territory

" ''Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 7:2 (June 1929) 168–169 (retrieved August 16, 2006).

Counties of the Oklahoma Panhandle

United States Census Bureau *Wardell, Morris L

''Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 1:1 (January 1921) 60–89 (retrieved August 16, 2006).

Cimarron Council of the Boy Scouts of AmericaOklahoma History Center: Education ProgramsEncyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Cimarron Territory

{{American panhandles Regions of Oklahoma Pre-statehood history of Oklahoma Geography of Beaver County, Oklahoma Geography of Cimarron County, Oklahoma Geography of Texas County, Oklahoma 1850 establishments in the United States 1890 disestablishments in the United States

Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New ...

, consisting of Cimarron County, Texas County and Beaver County, from west to east. As with other salients in the United States, its name comes from the similarity of its shape to the handle of a pan.

The three-county Oklahoma Panhandle region had a population of 28,751 at the 2010 U.S. Census, representing 0.77% of the state's population. This is a decrease in total population of 1.2%, a loss of 361 people, from the 2000 U.S. Census

The United States census of 2000, conducted by the Census Bureau, determined the resident population of the United States on April 1, 2000, to be 281,421,906, an increase of 13.2 percent over the 248,709,873 people enumerated during the 1990 cen ...

.

Geography

Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

and Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

at 37°N on the north, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

at 103°W on the west, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

at 36.5°N on the south, and the remainder of Oklahoma at 100°W on the east.

The largest town in the region is Guymon, which is the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US ...

of Texas County. Black Mesa, the highest point in Oklahoma at , is located in Cimarron County. The Panhandle occupies nearly all of the true High Plains High Plains refers to one of two distinct land regions:

* High Plains (United States), land region of the western Great Plains

*High Plains (Australia)

The High Plains of south-eastern Australia are a sub-region, or more strictly a string of adja ...

within Oklahoma, being the only part of the state lying west of the 100th meridian, which generally marks the westernmost extent of moist air from the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

. The North Canadian River is named Beaver River or Beaver Creek on its course through the Panhandle. Its land area is and comprises 8.28 percent of Oklahoma's land area. The area includes Beaver Dunes State Park

Beaver Dunes Park is in Beaver County, Oklahoma, near the city of Beaver. The park, located in the panhandle region of Oklahoma, offers dune buggy riding on of sand hills, fishing, hiking trails, a playground and two campgrounds. Hackberry B ...

with sand dunes along the Beaver River and Optima Lake, the home of the Optima National Wildlife Refuge

Located in the middle of the Oklahoma panhandle, the Optima National Wildlife Refuge is made up of grasslands and wooded bottomland on the Coldwater Creek arm of the Optima Lake project.

The 8,062-acre Optima Wildlife Management Area, an Oklaho ...

.

History

What is now the Oklahoma Panhandle has been occupied for millennia. The Paleo-Indian people of the region were part of the Beaver River complex. A Paleo-Indian encampment, the Bull Creek site, dates back to approximately 8450 BCE, and the Badger Hole site dates to circa 8400 BCE.

Shortly before the arrival of European explorers, the Panhandle was home to Southern Plains villagers. From 1200 to 1500, the semi-sedentary Panhandle culture peoples, including the

What is now the Oklahoma Panhandle has been occupied for millennia. The Paleo-Indian people of the region were part of the Beaver River complex. A Paleo-Indian encampment, the Bull Creek site, dates back to approximately 8450 BCE, and the Badger Hole site dates to circa 8400 BCE.

Shortly before the arrival of European explorers, the Panhandle was home to Southern Plains villagers. From 1200 to 1500, the semi-sedentary Panhandle culture peoples, including the Antelope Creek phase The Antelope Creek Phase was an American Indian culture in the Texas Panhandle and adjacent Oklahoma dating from AD 1200 to 1450. The two most important areas where the Antelope Creek people lived were in the Canadian River valley centered on presen ...

, lived in the region in large, stone-slab and plaster houses in villages or individual homesteads. As horticulturists, they farmed maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

and indigenous crops from the Eastern Agricultural Complex. Several Antelope Creek phase sites were founded near present-day Guymon, including the McGrath, Stamper and Two Sisters sites. The arrival of horses from Spain in the 16th century, allowed American Indian tribes

In the United States, an American Indian tribe, Native American tribe, Alaska Native village, tribal nation, or similar concept is any extant or historical clan, tribe, band, nation, or other group or community of Native Americans in the Unit ...

to increase their hunting ranges. These Southern Plains villagers became the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes.

The Western history of the Panhandle traces its origins as being part of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the A ...

. The Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and define ...

of 1819 between Spain and the United States set the western boundary of this portion of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

at the 100th meridian. With Mexican independence in 1821, these lands became part of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. With the formation of the Texas Republic, they became part of Texas. When Texas joined the U.S. in 1846, the strip became part of the United States.Gibson, Arrell M. ''Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries''. Retrieved May 11, 2013. Available on Google Book/ref> The Cimarron Cutoff for the

Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, ...

passed through the area soon after the trade route was established in 1826 between the Mexicans in Santa Fe and the Americans in St. Louis. The route was increasingly used during the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

. The cutoff passed several miles north of what are now Boise City, Oklahoma, and Clayton, New Mexico, before continuing toward Santa Fe.

When Texas sought to enter the Union in 1845 as a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, federal law in the United States, based on the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

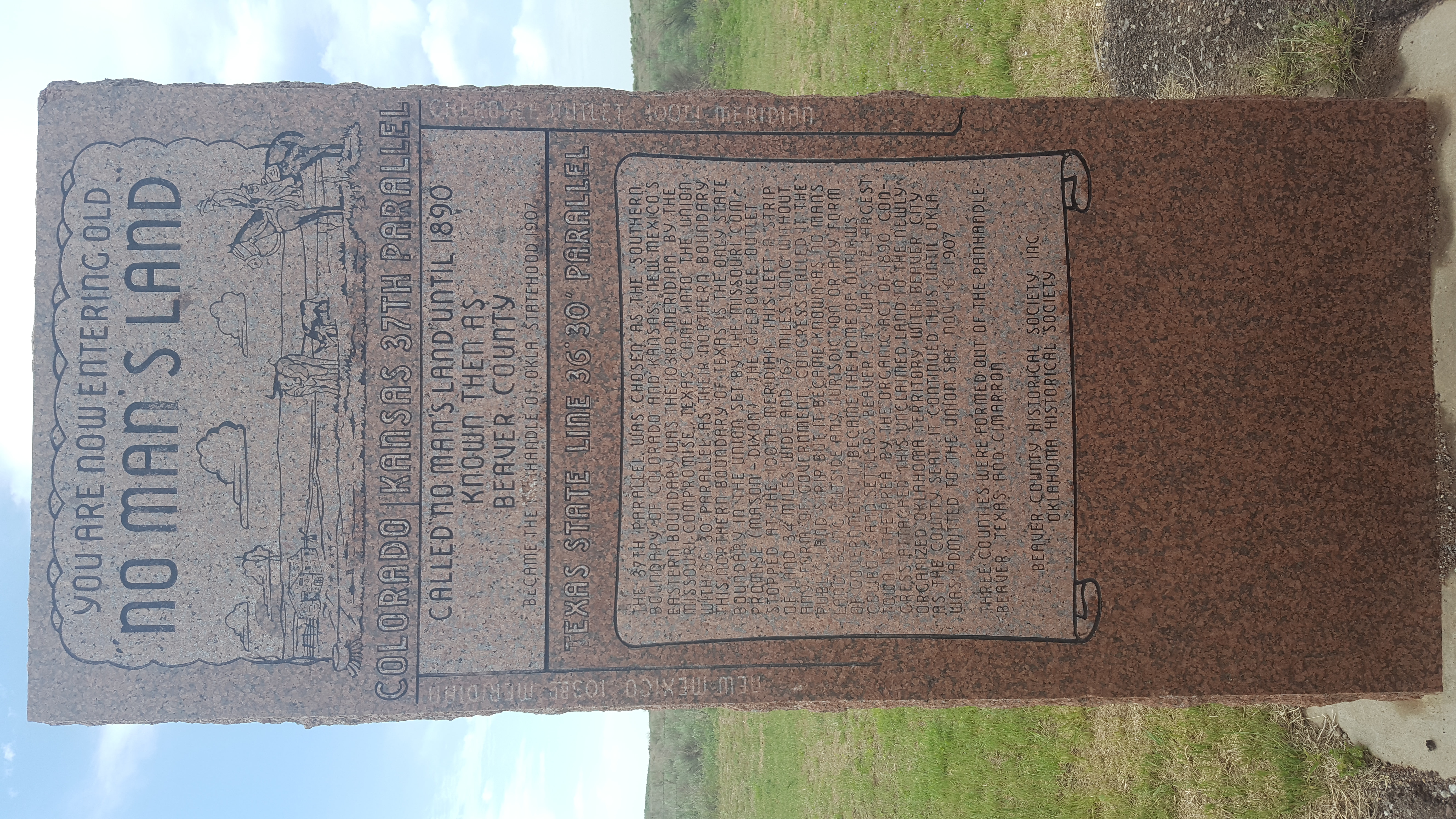

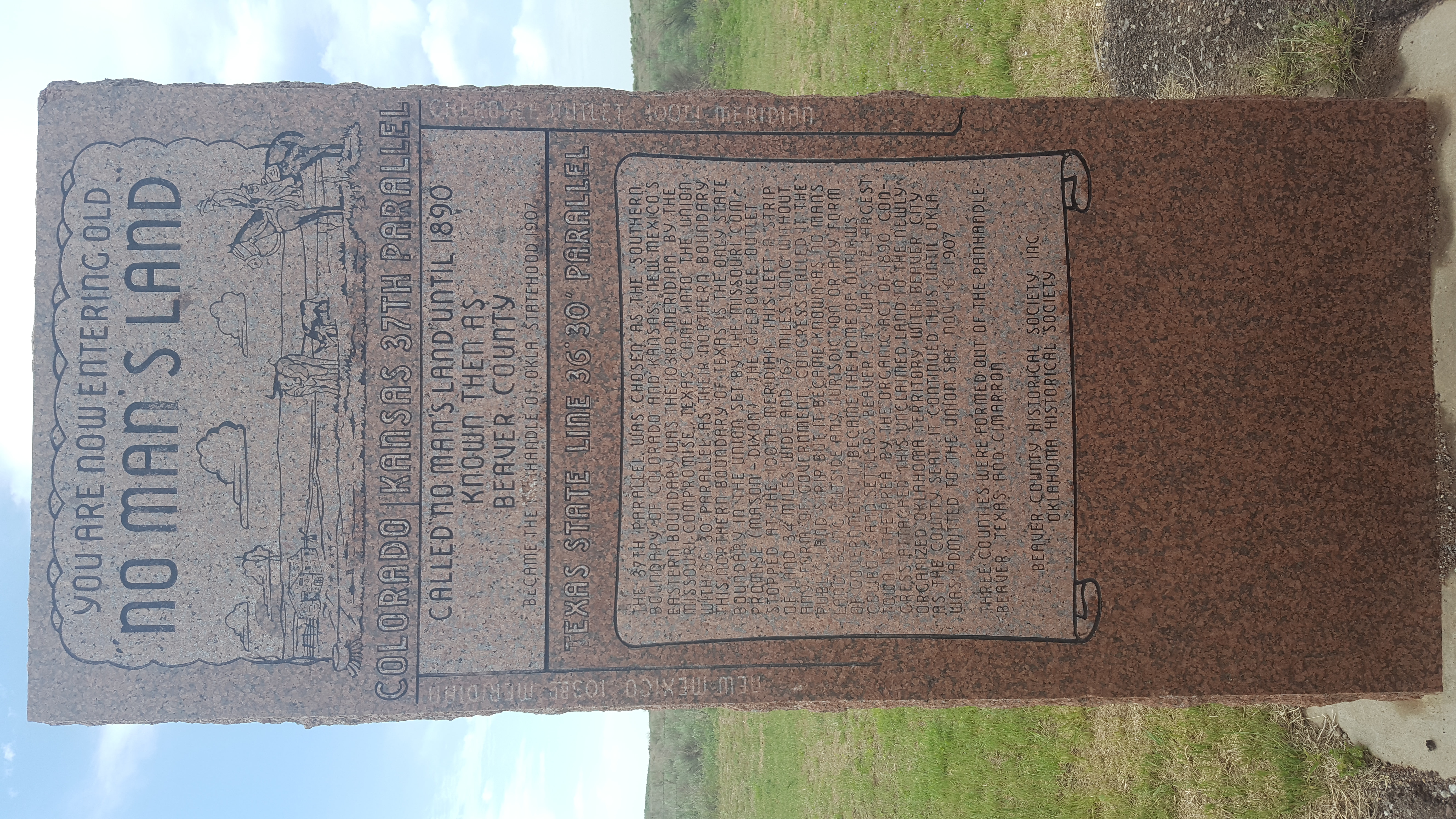

, prohibited slavery north of 36°30' parallel north. Under the Compromise of 1850, Texas surrendered its lands north of 36°30' latitude. The 170-mile strip of land, a "neutral strip", was left with no state or territorial ownership from 1850 until 1890. It was officially called the "Public Land Strip" and was commonly referred to as "No Man's Land."

The Compromise of 1850 also established the eastern boundary of New Mexico Territory at the 103rd meridian, thus setting the western boundary of the strip. The Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

of 1854 set the southern border of Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the free state of Kansas.

...

as the 37th parallel. This became the northern boundary of "No Man's Land." When Kansas joined the Union in 1861, the western part of Kansas Territory was assigned to the Colorado Territory

The Territory of Colorado was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 28, 1861, until August 1, 1876, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Colorado.

The territory was organized in the ...

but did not change the boundary of "No Man's Land."

Cimarron Territory

After theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, cattlemen moved into the area. Gradually they organized themselves into ranches and established their own rules for arranging their land and adjudicating their disputes. There was still confusion over the status of the strip, and some attempts were made to arrange rent with the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

s, despite the fact that the Cherokee Outlet ended at the 100th meridian. In 1885, the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that the strip was not part of the Cherokee Outlet.Sara Richter and Tom Lewis, "Cimarron Territory", ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. Accessed April 13, 2013. In 1886,

Interior Secretary

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natur ...

L. Q. C. Lamar declared the area to be public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable. Because those rights have expired ...

and subject to "squatter's rights

Adverse possession, sometimes colloquially described as "squatter's rights", is a legal principle in the Anglo-American common law under which a person who does not have legal title to a piece of property—usually land (real property)—may ...

".Wardell, p. 83.

The strip was not yet surveyed, and as that was one of the requirements of the Homestead Act of 1862

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of ...

, the land could not be officially settled. Settlers by the thousands flooded in to assert their "squatter's rights" anyway. They surveyed their own land and by September 1886 had organized a self-governing and self-policing jurisdiction, which they named the Cimarron Territory. Senator Daniel W. Voorhees

Daniel Wolsey Voorhees (September 26, 1827April 10, 1897) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senator from Indiana from 1877 to 1897. He was the leader of the Democratic Party and an anti-war Copperhead during th ...

of Indiana introduced a bill in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to attach the so-called territory to Kansas. It passed both the Senate and the House of Representatives but was not signed by President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

.

The organization of Cimarron Territory began soon after Secretary Lamar declared the area open to settlement by squatters. The settlers formed their own vigilance committee

A vigilance committee was a group formed of private citizens to administer law and order or exercise power through violence in places where they considered governmental structures or actions inadequate. A form of vigilantism and often a more stru ...

s, which organized a board charged with forming a territorial government. The board enacted a preliminary code of law and divided the strip into three districts. They also called for a general election to choose three members from each district to form a government.

The elected council met as planned, elected Owen G. Chase as president, and named a full cabinet. They also enacted further laws and divided the strip into five counties (Benton, Beaver, Palo Duro, Optima, and Sunset), three senatorial districts (with three members from each district), and seven delegate districts (with two members from each district). The members from these districts were to be the legislative body

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

for the proposed territory. Elections were held November 8, 1887, and the legislature met for the first time on December 5, 1887.

Chase went to Washington, D.C., to lobby for admission to Congress as the delegate from the new territory. He was not recognized by Congress. A group disputing the Chase organization met and elected and sent its own delegate to Washington. A bill was introduced to accept Chase but was never brought to a vote. Neither delegation was able to persuade Congress to accept the new territory. Another delegation went in 1888 but was also unsuccessful.

Settlement and assimilation

In 1889, the Unassigned Lands to the east of the territory were opened for settlement, and many of the residents went there. The remaining population was generously estimated by Chase at 10,000 after the opening. Ten years later, an actual count revealed a population of 2,548. The passage of the Organic Act in 1890 assigned ''Public Land Strip'' to the new Oklahoma Territory, and ended the short-lived Cimarron Territory aspirations. In 1891, the government completed the survey, and the remaining squatters were finally able to secure their homesteads under the Homestead Act. The new owners were then able to obtain mortgages against their property, enabling them to buy seed and equipment. Capital and new settlers came into the area, and the first railroad, the Rock Island, built a line through the county fromLiberal, Kansas

Liberal is the county seat of Seward County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 19,825. Liberal is home of Seward County Community College.

History

Early settler S. S. Rogers built the first hou ...

, to Dalhart, Texas. Agriculture began changing from subsistence farms to grain exporters.

''"''No Man's Land''"'' became Seventh County under the newly organized Oklahoma Territory and was soon renamed Beaver County. Beaver City became the county seat. When Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

were combined in 1907 as the state of Oklahoma, Beaver County was divided into Beaver, Texas, and Cimarron counties. The Oklahoma Panhandle had the highest population at its first census in 1910, 32,433 residents, compared to 28,729 in the 2020 census.

Dust Bowl

The Panhandle was severely affected by the drought of the 1930s. The drought began in 1932 and created massive dust storms. By 1935, the area was widely known as being part of the Dust Bowl. The dust storms were largely a result of poor farming techniques and the plowing up of the native grasses that had held the fine soil in place. Despite government efforts to implement conservation measures and change the basic farming methods of the region, the Dust Bowl persisted for nearly a decade. It contributed significantly to the length of theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

in the United States. Each of the three counties experienced a major loss of population during the 1930s.

The social impact of the dust bowl and the resulting emigration of tenant farmers from the Panhandle is the setting for the 1939 novel ''The Grapes of Wrath

''The Grapes of Wrath'' is an American realist novel written by John Steinbeck and published in 1939. The book won the National Book Award

and Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Priz ...

'' by Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

-winning author John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

.

Demographics

As of the 2010 census, there were a total of 28,751 people, 10,451 households, and 7,466 families in the three counties that comprise the Oklahoma Panhandle.U.S. Census website, United States Census Bureau. (accessed September 3, 2013) The racial makeup of the region was 80.26%

white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

(including persons of mixed race), 59.46% non-Hispanic white, 1.34% African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, 1.21% Native American, 1.18% Asian, 0.12% Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/ racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of O ...

, 15.53% from other races, and 2.78% from two or more races

2 (two) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 1 and preceding 3. It is the smallest and only even prime number. Because it forms the basis of a duality, it has religious and spiritual significance in many cultur ...

. Hispanic and Latino Americans

Hispanic and Latino Americans ( es, Estadounidenses hispanos y latinos; pt, Estadunidenses hispânicos e latinos) are Americans of Spaniards, Spanish and/or Latin Americans, Latin American ancestry. More broadly, these demographics include a ...

made up 35.85% of the population. The median income for a household in the region was $34,404, and the median income for a family was $40,006. Males had a median income of $27,444 versus $19,559 for females. The per capita income

Per capita income (PCI) or total income measures the average income earned per person in a given area (city, region, country, etc.) in a specified year. It is calculated by dividing the area's total income by its total population.

Per capita i ...

for the region was $16,447.

Cities and towns

Major communities

*Beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers a ...

(county seat of Beaver County)

* Boise City (county seat of Cimarron County)

* Goodwell (home to Oklahoma Panhandle State University

Oklahoma Panhandle State University (OPSU) is a public college in Goodwell, Oklahoma. OPSU is a baccalaureate degree-granting institution. General governance of the institution is provided by the Board of Regents of the Oklahoma Agricultural a ...

)

* Guymon (county seat of Texas County and largest city in the Oklahoma Panhandle)

* Hooker

* Texhoma

Other communities

* Adams *Balko

''Balko'' is a German prime time television series broadcast on the private TV channel RTL. It is a police detective story with comical twists featuring two inspectors of the Dortmund police, Balko (played by Jochen Horst until episode 48, the ...

*Felt

Felt is a textile material that is produced by matting, condensing and pressing fibers together. Felt can be made of natural fibers such as wool or animal fur, or from synthetic fibers such as petroleum-based acrylic or acrylonitrile or wood ...

* Forgan

*Gate

A gate or gateway is a point of entry to or from a space enclosed by walls. The word derived from old Norse "gat" meaning road or path; But other terms include ''yett and port''. The concept originally referred to the gap or hole in the wall ...

*Hardesty Hardesty may refer to:

Places United States

* Hardesty, Maryland, also known as Queen Anne

* Hardesty, Oklahoma

People

* Bob Hardesty (1931–2013), American educator

* Brandon Hardesty (born 1987), American comedic performer and actor

* Da ...

* Kenton

* Keyes

* Knowles

* Optima

* Turpin

* Tyrone

* Floris

Economy

The Panhandle is rather thinly populated (when compared to the rest of Oklahoma) making the labor force in this region very small. Farming and ranching operations occupy most of the economic activity in the region, with ranching dominating the drier western end. The region's higher educational needs are served byOklahoma Panhandle State University

Oklahoma Panhandle State University (OPSU) is a public college in Goodwell, Oklahoma. OPSU is a baccalaureate degree-granting institution. General governance of the institution is provided by the Board of Regents of the Oklahoma Agricultural a ...

in Goodwell, 10 miles southwest of Guymon.Available on Google Books.p. 206. Retrieved January 19. 2014.

Politics

The Oklahoma Panhandle is one of the most universally Republican areas of what has become one of the most Republican states in the nation. Beaver and Texas counties last supported a Democrat for president in 1948, while Cimarron County last supported a Democrat in 1976. In the 2020 U.S. presidential election, the three counties gave a weighted average of 85.1% of their votes toDonald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

and 13.2% to Joe Biden, with Trump carrying the state over Biden 65.4% to 32.3%.

In the 2006 Oklahoma gubernatorial election

The 2006 Oklahoma gubernatorial election was held on November 7, 2006. Incumbent Democratic Governor Brad Henry won re-election to a second term in a landslide, defeating Republican U.S. Representative Ernest Istook. Henry took 66.5% of the vo ...

, the Oklahoma Panhandle counties were the only three where the majority voted against the successfully reelected Democratic incumbent, Governor Brad Henry. In 2012, Democratic voters in the Panhandle voted for Randall Terry, an anti-abortion

Anti-abortion movements, also self-styled as pro-life or abolitionist movements, are involved in the abortion debate advocating against the practice of abortion and its legality. Many anti-abortion movements began as countermovements in respo ...

activist, over incumbent Democrat Barack Obama in the Democratic Presidential primary.

Points of interest

* Black Mesa State Park features a hiking trail to the top of Oklahoma's highest point. *Beaver Dunes State Park

Beaver Dunes Park is in Beaver County, Oklahoma, near the city of Beaver. The park, located in the panhandle region of Oklahoma, offers dune buggy riding on of sand hills, fishing, hiking trails, a playground and two campgrounds. Hackberry B ...

features massive sand dunes along the Beaver River – located just north of the town of Beaver.

* Optima Lake is home to the Optima National Wildlife Refuge

Located in the middle of the Oklahoma panhandle, the Optima National Wildlife Refuge is made up of grasslands and wooded bottomland on the Coldwater Creek arm of the Optima Lake project.

The 8,062-acre Optima Wildlife Management Area, an Oklaho ...

.

Notes

References

*Beck, T.E.Cimarron Territory

" ''Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 7:2 (June 1929) 168–169 (retrieved August 16, 2006).

Counties of the Oklahoma Panhandle

United States Census Bureau *Wardell, Morris L

''Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 1:1 (January 1921) 60–89 (retrieved August 16, 2006).

Further reading

*Christman, Harry E. (editor-original manuscript by Jim Herron). ''Fifty Years on the Owl Hoot Trail: The First Sheriff of No Man's Land, Oklahoma Territory''. Sage Books: Chicago, 1969. * Lowitt, Richard. ''American Outback: The Oklahoma Panhandle in the Twentieth Century'' (Texas Tech University Press, 2006) . xxii, 137 pp.External links

{{American panhandles Regions of Oklahoma Pre-statehood history of Oklahoma Geography of Beaver County, Oklahoma Geography of Cimarron County, Oklahoma Geography of Texas County, Oklahoma 1850 establishments in the United States 1890 disestablishments in the United States