Office of War Information on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a

The OWI's creation was not without controversy. The American public, and the

The OWI's creation was not without controversy. The American public, and the

In 1942 the OWI established the

In 1942 the OWI established the  In conjunction with the War Relocation Authority, the OWI produced a series of documentary films related to the internment of Japanese Americans. '' Japanese Relocation'' and several other films were designed to educate the general public on the internment, to counter the tide of

In conjunction with the War Relocation Authority, the OWI produced a series of documentary films related to the internment of Japanese Americans. '' Japanese Relocation'' and several other films were designed to educate the general public on the internment, to counter the tide of

this Google list

The OWI Bureau of Motion Pictures (BMP) worked with the

The details of OWI's involvement can be divided into operations in the European and Pacific Theaters.

The details of OWI's involvement can be divided into operations in the European and Pacific Theaters.

Congressional opposition to the domestic operations of the OWI resulted in increasingly curtailed funds. Congress accused the OWI as President Roosevelt's campaign agency, and pounced on any miscommunications and scandals as reason for disbandment. In 1943, the OWI's appropriations were cut out of the following year's budget and only restored with strict restrictions on OWI's domestic capabilities. Many overseas branch offices were closed, as well as the Motion Picture Bureau. By 1944 the OWI operated mostly in the foreign field, contributing to undermining enemy morale. The agency was abolished in 1945, and many of its foreign functions were transferred to the

Congressional opposition to the domestic operations of the OWI resulted in increasingly curtailed funds. Congress accused the OWI as President Roosevelt's campaign agency, and pounced on any miscommunications and scandals as reason for disbandment. In 1943, the OWI's appropriations were cut out of the following year's budget and only restored with strict restrictions on OWI's domestic capabilities. Many overseas branch offices were closed, as well as the Motion Picture Bureau. By 1944 the OWI operated mostly in the foreign field, contributing to undermining enemy morale. The agency was abolished in 1945, and many of its foreign functions were transferred to the

Finding aid to Armitage Watkins papers on the Office of War Information at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

OWI images at the Museum of the City of New York

(Library of Congress) * ttp://americanhistory.si.edu/victory/victory5.htm World War II OWI postersbr>World War Poster Collection

hosted by the University of North Texas Libraries

Digital Collections

* ttp://eisenhower.archives.gov/Research/Finding_Aids/S.html Papers of Paul Sturman, Foreign Language Division of OWI, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library {{DEFAULTSORT:United States Office Of War Information War Information United States government propaganda organizations Politics of World War II Agencies of the United States government during World War II Government agencies established in 1942 American propaganda during World War II 1942 establishments in the United States 1945 disestablishments in the United States Government agencies disestablished in 1945

United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

agency created during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The OWI operated from June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and other forms of media, the OWI was the connection between the battlefront and civilian communities. The office also established several overseas branches, which launched a large-scale information and propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

campaign abroad. From 1942 to 1945, the OWI revised or discarded any film scripts reviewed by them that portrayed the United States in a negative light, including anti-war material.

History

Origins

President Franklin D. Roosevelt promulgated the OWI on June 13, 1942, by Executive Order 9182. TheExecutive Order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

consolidated the functions of the Office of Facts and Figures (OFF, OWI's direct predecessor), the Office of Government Reports, and the Division of Information of the Office for Emergency Management. The Foreign Information Service, a division of the Office of the Coordinator of Information, became the core of the Overseas Branch of the OWI.Weinberg, p. 77

At the onset of World War II, the American public was in the dark regarding wartime information. One American observer noted: “It all seemed to boil down to three bitter complaints…first, that there was too much information; second, that there wasn’t enough of it; and third, that in any event it was confusing and inconsistent”. Further, the American public confessed a lack of understanding as to why the world was at war, and held great resentment against other Allied Nations. President Roosevelt established the OWI to both meet the demands for news and less confusion, as well as resolve American apathy towards the war.

The OWI's creation was not without controversy. The American public, and the

The OWI's creation was not without controversy. The American public, and the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

in particular, were wary of propaganda for several reasons. First, the press feared a centralized agency as the sole distributor of wartime information. Second, Congress feared an American propaganda machine that could resemble Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

’ operation in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Third, previous attempts at propaganda under the Committee on Public Information

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States under the Wilson administration created to influence public opinion to support the ...

/Creel Committee during WWI were viewed as a failure. And fourth, the American public favored an isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entan ...

or non-interventionist policy and were therefore hesitant to support a pro-war propaganda campaign targeting Americans.

But in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

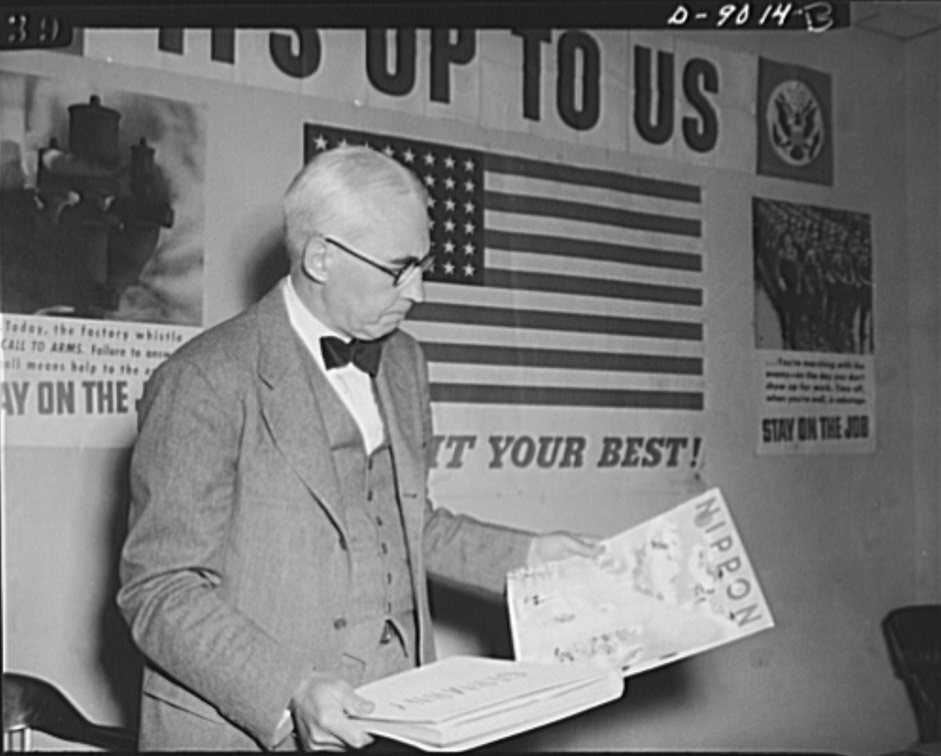

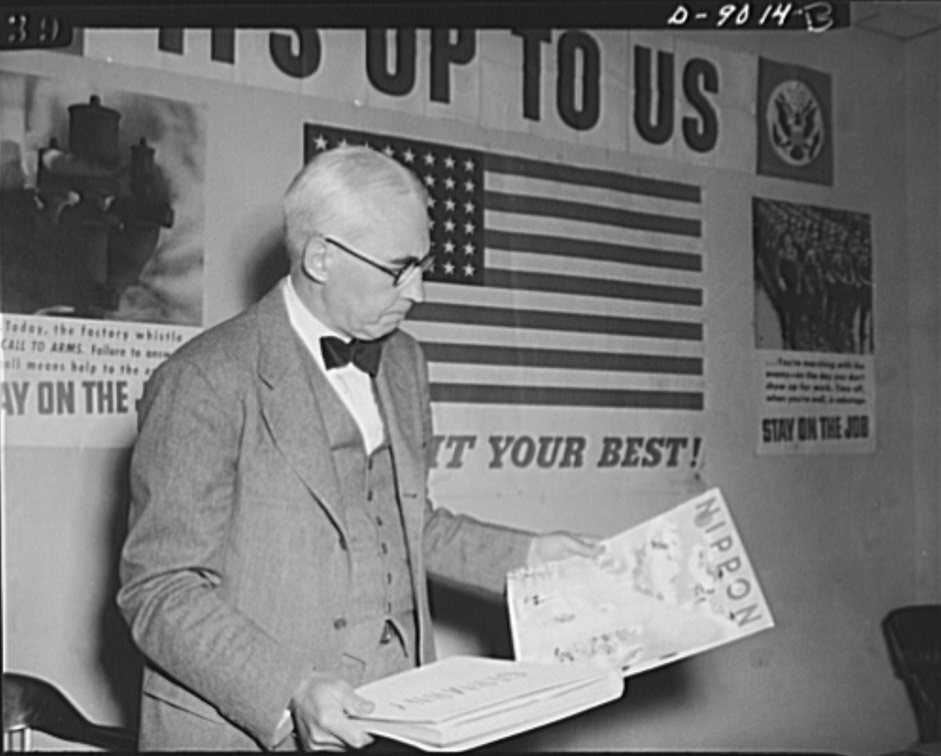

, the need for coordinated and properly disseminated wartime information from the military/administration to the public outweighed the fears associated with American propaganda. President Roosevelt entrusted the OWI to journalist and CBS newsman Elmer Davis

Elmer Holmes Davis (January 13, 1890 – May 18, 1958) was an American news reporter, author, the Director of the United States Office of War Information during World War II and a Peabody Award recipient.

Early life and career

Davis was born i ...

, with the mission to take “an active part in winning the war and in laying the foundations for a better postwar world”.

President Roosevelt ordered Davis to “formulate and carry out, through the use of press, radio, motion picture, and other facilities, information programs designed to facilitate the development of an informed and intelligent understanding, at home and abroad, of the status and progress of the war effort and of the war policies, activities, and aims of the Government”. The OWI's operations were thus divided between the Domestic and Overseas Branches.

Domestic operations

The OWI Domestic Radio Bureau produced series such as '' This is Our Enemy'' (spring 1942), which dealt with Germany, Japan, and Italy; ''Uncle Sam'', which dealt with domestic themes; and '' Hasten the Day'' (August 1943), which focussed on the Home Front, the NBC Blue Network's '' Chaplain Jim''. The radio producer Norman Corwin produced several series for the OWI, including '' An American in England'', '' An American in Russia'', and ''Passport for Adams

A passport is an official travel document issued by a government that contains a person's identity. A person with a passport can travel to and from foreign countries more easily and access consular assistance. A passport certifies the personal ...

'', which starred Robert Young, Ray Collins, Paul Stewart and Harry Davenport Harry Davenport may refer to:

* Harry Davenport (actor) (1866–1949), American film and stage actor

* Harry Davenport (footballer) (1900–1984), Australian footballer

* Harry J. Davenport (1902–1977), Democratic Party member of the U.S. House ...

.

In 1942 the OWI established the

In 1942 the OWI established the Voice of America

Voice of America (VOA or VoA) is the State media, state-owned news network and International broadcasting, international radio broadcaster of the United States, United States of America. It is the largest and oldest U.S.-funded international br ...

(VOA), which remains in service as the official government international broadcasting service of the United States. The VOA initially borrowed transmitters from the commercial networks. The programs OWI produced included those provided by the Labor Short Wave Bureau, whose material came from the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

and the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

.

In conjunction with the War Relocation Authority, the OWI produced a series of documentary films related to the internment of Japanese Americans. '' Japanese Relocation'' and several other films were designed to educate the general public on the internment, to counter the tide of

In conjunction with the War Relocation Authority, the OWI produced a series of documentary films related to the internment of Japanese Americans. '' Japanese Relocation'' and several other films were designed to educate the general public on the internment, to counter the tide of anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia and anti-Japanism) involves the hatred or fear of anything which is Japanese, be it its culture or its people. Its opposite is Japanophilia.

Overview

Anti-Japanese sentim ...

in the country, and to encourage Japanese-American internees to resettle outside camp or to enter military service. The OWI also worked with camp newspapers to disseminate information to internees.

During 1942 and 1943 the OWI boasted two photographic units whose photographers documented the country's mobilization during the early years of the war, concentrating on such topics as aircraft factories and women in the workforce

Since the industrial revolution, participation of women in the workforce outside the home has increased in industrialized nations, with particularly large growth seen in the 20th century. Largely seen as a boon for industrial society, women in ...

. In addition, the OWI produced a series of 267 newsreels in 16 mm film, ''The United Newsreel'' which were shown overseas and to US audiences. These newsreels incorporated U.S. military footage. For examples sethis Google list

The OWI Bureau of Motion Pictures (BMP) worked with the

Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

movie studios to produce films that advanced American war aims. According to Elmer Davis

Elmer Holmes Davis (January 13, 1890 – May 18, 1958) was an American news reporter, author, the Director of the United States Office of War Information during World War II and a Peabody Award recipient.

Early life and career

Davis was born i ...

, "The easiest way to inject a propaganda idea into most people’s minds is to let it go through the medium of an entertainment picture when they do not realize that they are being propagandized." Successful films depicted the Allied armed forces as valiant "Freedom fighters", and advocated for civilian participation, such as conserving fuel or donating food to troops.

By July 1942 OWI administrators realized that the best way to reach American audiences was to present war films in conjunction with feature films. OWI's presence in Hollywood deepened throughout World War II, and by 1943 every major Hollywood studio (except Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

) allowed the OWI to examine their film scripts. OWI evaluated whether each film would promote the honor of the Allies' mission.

Foreign operations

The Overseas Branch enjoyed greater success and less controversy than the Domestic Branch. Abroad, the OWI operated a Psychological Warfare Branch (PWB), which used propaganda to terrorize enemy forces in combat zones, in addition to informing civilian populations in Allied camps. Leaflet warfare gained popularity during World War II and was utilized in regions such as Northern Africa, Italy, Germany, the Philippines, and Japan. For example, in Japan, the OWI printed and dropped over 180 million leaflets, with about 98 million being dropped in the summer months of 1945. Leaflets dropped in Tunisia read: “You Are Surrounded” and “Drowning Is a Nasty Death”. Millions of leaflets dropped in Sicily read: “The time has come for you to decide whether Italians shall die forMussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until Fall of the Fascist re ...

and Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

or live for Italy and civilization”.

OWI also used newspapers and publicized magazines to further American war aims. Magazines distributed to foreign audiences, such as ''Victory'', intended to convey to foreign Allied civilians that American civilians were contributing to the war. ''Victory'' showcased America's manufacturing power, and sought to foster an appreciation for the American lifestyle.

Aside from the aforementioned publication and production styles of propaganda, the OWI also utilized unconventional propaganda vehicles known as "specialty items." Specific examples of these items include packets of seeds, matchbooks, soap paper, and sewing kits. The packets of seeds had an American flag and a message printed on the outside that identified the donor. Each matchbook was inscribed with the “Four Freedoms” on the inside cover. Soap paper was etched with the message: "From your friends the United Nations. Dip in wateruse like soap. WASH OFF THE NAZI DIRT." Sewing kit pincushions were shaped like a human rear end. On the reverse side lay a caricatured face of either Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

or Japanese General Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

.

The details of OWI's involvement can be divided into operations in the European and Pacific Theaters.

The details of OWI's involvement can be divided into operations in the European and Pacific Theaters.

European Theater

One of the most astounding of all OWI operations occurred in Luxembourg. Known as Operation Annie, the United States 12th Army Group ran a secret radio station from 2:00–6:30 am every morning from a house in Luxembourg pretending to be loyal Rhinelanders under Nazi occupation. They spoke of Nazi commanders hiding their desperate position from the German public, which caused dissent among Nazi supporters. Further, they led Nazi forces into an Allied trap, and then staged an Allied attack on the Annie Radio office to maintain their cover. On the Eastern front, the OWI struggled not to offend Polish and Soviet Allies. As the Soviets advanced from the East towards Germany, they swept through Poland without hesitation. However, Poles considered much of the land of the Eastern front as their own. The OWI struggled to present the news (including the pronunciation of town names or and discussion of county or national boundaries) without offending either party. Further, Poles and Soviets criticized the OWI for promoting the idealization of war, when their physical and human losses so heavily outweighed that of America's.Pacific Theater

The OWI was one of the most prolific sources of propaganda in “Free China.” They operated a sophisticated propaganda machine that sought to demoralize the Japanese army and create a portrait of US war aims that would appeal to the Chinese audience. OWI employed many Chinese, second-generation Japanese ( Nisei), Japanese POWs, Korean exiles, etc. to help gather and translate information, as well as transmit programs in multiple languages across the Pacific. OWI also created communication channels (logistical support) for intelligence and coded information. However, the OWI encountered public relations difficulties in China and India. In China, the OWI unsuccessfully attempted to stay removed from the Nationalist versus Communist conflict. However, the Roosevelt administration and OWI officials took issue with many aspects ofChiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

’s rule, and conversely, Chiang placed spies in the OWI. Also, the OWI struggled to paint a post-war image of China without offending Nationalist or Communist leaders. In India, the Americans and British agreed to win the war first, then deal with (de)colonization.Winkler, p. 83 The OWI feared that broadcasts advocating liberty from oppression would incite India rebellions and jeopardize cooperation with the British. But this approach angered Indians as well as the African-American lobby at home who recognized the hypocrisy in American policy.

Controversies at home

From 1942 to 1945, the OWI's Bureau of Motion Pictures reviewed 1,652 film scripts and revised or discarded any that portrayed the United States in a negative light, including material that made Americans seem "oblivious to the war or anti-war."Elmer Davis

Elmer Holmes Davis (January 13, 1890 – May 18, 1958) was an American news reporter, author, the Director of the United States Office of War Information during World War II and a Peabody Award recipient.

Early life and career

Davis was born i ...

, the head of the OWI, said that "The easiest way to inject a propaganda idea into most people's minds is to let it go through the medium of an entertainment picture when they do not realize they're being propagandized".

The OWI suffered from conflicting aims and poor management. For instance, Elmer Davis, who wanted to “see that the American people are truthfully informed,” clashed with the military that routinely withheld information for “public safety”. Further, OWI employees grew ever more dissatisfied with “what they regarded as a turn away from the fundamental, complex issues of the war in favor of manipulation and stylized exhortation”. On April 14, 1943, several OWI writers resigned from office and released a scathing statement to the press explaining how they no longer felt they could give an objective picture of the war because “high-pressure promoters who prefer slick salesmanship to honest information” dictated OWI decision-making. President Roosevelt's “wait-and-see” attitude and wavering public support for OWI damaged public opinion of the agency.

Congressional opposition to the domestic operations of the OWI resulted in increasingly curtailed funds. Congress accused the OWI as President Roosevelt's campaign agency, and pounced on any miscommunications and scandals as reason for disbandment. In 1943, the OWI's appropriations were cut out of the following year's budget and only restored with strict restrictions on OWI's domestic capabilities. Many overseas branch offices were closed, as well as the Motion Picture Bureau. By 1944 the OWI operated mostly in the foreign field, contributing to undermining enemy morale. The agency was abolished in 1945, and many of its foreign functions were transferred to the

Congressional opposition to the domestic operations of the OWI resulted in increasingly curtailed funds. Congress accused the OWI as President Roosevelt's campaign agency, and pounced on any miscommunications and scandals as reason for disbandment. In 1943, the OWI's appropriations were cut out of the following year's budget and only restored with strict restrictions on OWI's domestic capabilities. Many overseas branch offices were closed, as well as the Motion Picture Bureau. By 1944 the OWI operated mostly in the foreign field, contributing to undermining enemy morale. The agency was abolished in 1945, and many of its foreign functions were transferred to the Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

.

Some of the writers, producers, and actors of OWI programs admired the Soviet Union and were either loosely affiliated with or were members of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Rev ...

. The director of Pacific operations for the OWI, Owen Lattimore, who later accompanied U.S. Vice-President Henry Wallace on a mission to China and Mongolia in 1944, was later alleged to be a Soviet agent on the basis of testimony by a defector from the Soviet GRU, General Alexander Barmine

Alexander Grigoryevich Barmin (russian: Александр Григорьевич Бармин, ''Aleksandr Grigoryevich Barmin''; August 16, 1899 – December 25, 1987), most commonly Alexander Barmine, was an officer in the Soviet Army and dip ...

.

In his final report, Elmer Davis noted that he had fired 35 employees, because of past Communist associations, though the FBI files showed no formal allegiance to the CPUSA. After the war, as a broadcast journalist, Davis staunchly defended Owen Lattimore

Owen Lattimore (July 29, 1900 – May 31, 1989) was an American Orientalist and writer. He was an influential scholar of China and Central Asia, especially Mongolia. Although he never earned a college degree, in the 1930s he was editor of ''Pacif ...

and others from what he considered outrageous and false accusations of disloyalty from Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Workers Party of America, Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet Union, Soviet spy (1932–1938), defe ...

and others. Flora Wovschin, who worked for the OWI from September 1943 to February 1945, was later revealed in the Venona project intercepts to have been a Soviet spy.

Dissolution and legacy

The OWI was terminated, effective September 15, 1945, by Executive Order 9608 on August 31, 1945. President Truman cited the OWI for "outstanding contribution to victory", and saw no reason to continue funding the agency post-war. The international offices of the OWI were transferred to the State Department, and the United States Information Service and theOffice of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

/Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

assumed many of the information gathering, analyzing, and disseminating responsibilities.Johnson, p. 341

Despite its troubled existence, the OWI is widely considered to be influential in the Allied victory and mobilizing American support for the war domestically.

People

Among the many people who worked for the OWI wereEitaro Ishigaki

was an American artist.

Life

Eitaro Ishigaki was born in Taiji, Wakayama, Japan in 1893. At the age of sixteen he emigrated to America in to live with his father in Seattle. A year later, in 1910, they moved to California, and in 1912, Ishigaki ...

, Ayako Tanaka Ishigaki, Jay Bennett, Humphrey Cobb

Humphrey Cobb (September 5, 1899 – April 25, 1944) was an Italian-born, Canadian-American screenwriter and novelist. He is known for writing the novel ''Paths of Glory'' (1935), which was made into an acclaimed 1957 anti-war film ''Paths ...

, Alan Cranston

Alan MacGregor Cranston (June 19, 1914 – December 31, 2000) was an American politician and journalist who served as a United States Senator from California from 1969 to 1993, and as a President of the World Federalist Association from 1949 to ...

, Elmer Davis

Elmer Holmes Davis (January 13, 1890 – May 18, 1958) was an American news reporter, author, the Director of the United States Office of War Information during World War II and a Peabody Award recipient.

Early life and career

Davis was born i ...

, Gardner Cowles Jr.

Gardner "Mike" Cowles Jr. (1903–1985) was an American newspaper and magazine publisher. He was co-owner of the Cowles Media Company, whose assets included the ''Minneapolis Star'', the ''Minneapolis Tribune'', the ''Des Moines Register'', ''L ...

, Martin Ebon, Milton S. Eisenhower

Milton Stover Eisenhower (September 15, 1899 – May 2, 1985) was an American academic administrator. He served as president of three major American universities: Kansas State University, Pennsylvania State University, and Johns Hopkins Universit ...

, Ernestine Evans, John Fairbank, Lee Falk, Howard Fast, Ralph J. Gleason

Ralph Joseph Gleason (March 1, 1917 – June 3, 1975) was an American music critic and columnist. He contributed for many years to the ''San Francisco Chronicle'', was a founding editor of ''Rolling Stone'' magazine, and cofounder of the Monterey ...

, Alexander Hammid

Alexandr Hackenschmied, born Alexander Siegfried George Hackenschmied, known later as Alexander Hammid (17 December 1907, Linz – 26 July 2004, New York City) was a Czech-American photographer, film director, cinematographer and film edit ...

, Leo Hershfield

Leo Hershfield (1904–1979) was a prominent American illustrator, cartoonist and courtroom artist for NBC News. NBC referred to him as the "Dean of Courtroom Artists" since he was the first modern artist to sketch trials for TV news in the 1950s ...

, Jane Jacobs

Jane Jacobs (''née'' Butzner; 4 May 1916 – 25 April 2006) was an American-Canadian journalist, author, theorist, and activist who influenced urban studies, sociology, and economics. Her book ''The Death and Life of Great American Cities'' ...

, Lewis Wade Jones Lewis Wade Jones (March 13, 1910September 1979) was a sociologist and teacher.

He was born in Cuero, Texas, the son of Wade E. and Lucynthia McDade Jones. A member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity, he received his AB degree from Fisk University in ...

, David Karr

David Harold Karr, born David Katz (1918, Brooklyn, New York – 7 July 1979, Paris) was a controversial American journalist, businessman, Communist and NKVD agent.

Early life

Enthralled with the radical left, Karr began writing at a relativel ...

, Philip Keeney Philip Olin Keeney (1891–1962), and his wife, Mary Jane Keeney, were librarians who became part of the Silvermaster spy ring in the 1940s.Rosalee McReynolds, Louise S. Robbins: ''The Librarian Spies: Philip and Mary Jane Keeney and Cold War Espio ...

, Christina Krotkova, Owen Lattimore

Owen Lattimore (July 29, 1900 – May 31, 1989) was an American Orientalist and writer. He was an influential scholar of China and Central Asia, especially Mongolia. Although he never earned a college degree, in the 1930s he was editor of ''Pacif ...

, Murray Leinster, Paul Linebarger

Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger (July 11, 1913 – August 6, 1966), better known by his pen-name Cordwainer Smith, was an American author known for his science fiction works. Linebarger was a US Army officer, a noted East Asia scholar, and a ...

, Irving Lerner

Irving Lerner (March 7, 1909, New York City – December 25, 1976, Los Angeles) was an American filmmaker.

Biography

Before becoming a filmmaker, Lerner was a research editor for Columbia University's Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, getting h ...

, Edward P. Lilly (historian), Alan Lomax

Alan Lomax (; January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American ethnomusicologist, best known for his numerous field recordings of folk music of the 20th century. He was also a musician himself, as well as a folklorist, archivist, writer, s ...

, Archibald MacLeish, Reuben H. Markham, Lowell Mellett, Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Charles Olson, Gordon Parks, James Reston

James Barrett Reston (November 3, 1909 – December 6, 1995), nicknamed "Scotty", was an American journalist whose career spanned the mid-1930s to the early 1990s. He was associated for many years with ''The New York Times.''

Early lif ...

, Peter C. Rhodes, Robert Riskin, Arthur Rothstein, Waldo Salt, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Wilbur Schramm, Robert Sherwood, Dody Weston Thompson

Dody Weston Thompson (April 11, 1923 – October 14, 2012) was a 20th-century American photographer and chronicler of the history and craft of photography. She learned the art in 1947 and developed her own expression of “straight” or realistic ...

(researcher-writer), William Stephenson, George E. Taylor, Chester S. Williams, Flora Wovschin, and Karl Yoneda

Karl Gozo Yoneda ( ja, 米田 剛三, July 15, 1906 – May 8, 1999) was a Japanese American activist, union organizer, World War II veteran and author. He played a substantial role in the founding of the International Longshore and Warehouse ...

.

Filmography

*'' This is Our Enemy'' *'' Hasten the Day'' *'' An American in England'' *'' An American in Russia'' *'' Japanese Relocation'' (1942) *'' Chaplain Jim'' *''Passport for Adams

A passport is an official travel document issued by a government that contains a person's identity. A person with a passport can travel to and from foreign countries more easily and access consular assistance. A passport certifies the personal ...

''

See also

* Frank Shozo Baba *Committee on Public Information

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States under the Wilson administration created to influence public opinion to support the ...

Notes

This link is no longer working. Here is a new link to the same page: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-9182-establishing-the-office-war-informationReferences

*Allan Winkler, ''The Politics of Propaganda: The Office of War Information, 1942–1945'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978). *Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives." Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa/ *Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Color Photographs." Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsac/ *Howard Blue, ''Words at War: World War II Radio Drama and the Postwar Broadcast Industry Blacklist'' (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2002). *Jack L. Hammersmith, "The U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) and the Polish Question, 1943–1945" (The Polish Review 19, no. 1 (1974)). *Koppes, Clayton R. and Gregory D. Black. ''Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990). . *Matthew D. Johnson, "Propaganda and Sovereignty in Wartime China: Morale Operations and Psychological Warfare under the Office of War Information" (Modern Asian Studies 45, no. 2 (2011)). http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0026749X11000023 *Sydney Weinberg, "What to Tell America: The Writers' Quarrel in the Office of War Information" (The Journal of American History 55, no. 1 (1968)).Archives

*Finding aid to Armitage Watkins papers on the Office of War Information at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

External links

OWI images at the Museum of the City of New York

(Library of Congress) * ttp://americanhistory.si.edu/victory/victory5.htm World War II OWI postersbr>World War Poster Collection

hosted by the University of North Texas Libraries

Digital Collections

* ttp://eisenhower.archives.gov/Research/Finding_Aids/S.html Papers of Paul Sturman, Foreign Language Division of OWI, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library {{DEFAULTSORT:United States Office Of War Information War Information United States government propaganda organizations Politics of World War II Agencies of the United States government during World War II Government agencies established in 1942 American propaganda during World War II 1942 establishments in the United States 1945 disestablishments in the United States Government agencies disestablished in 1945