North Pole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the

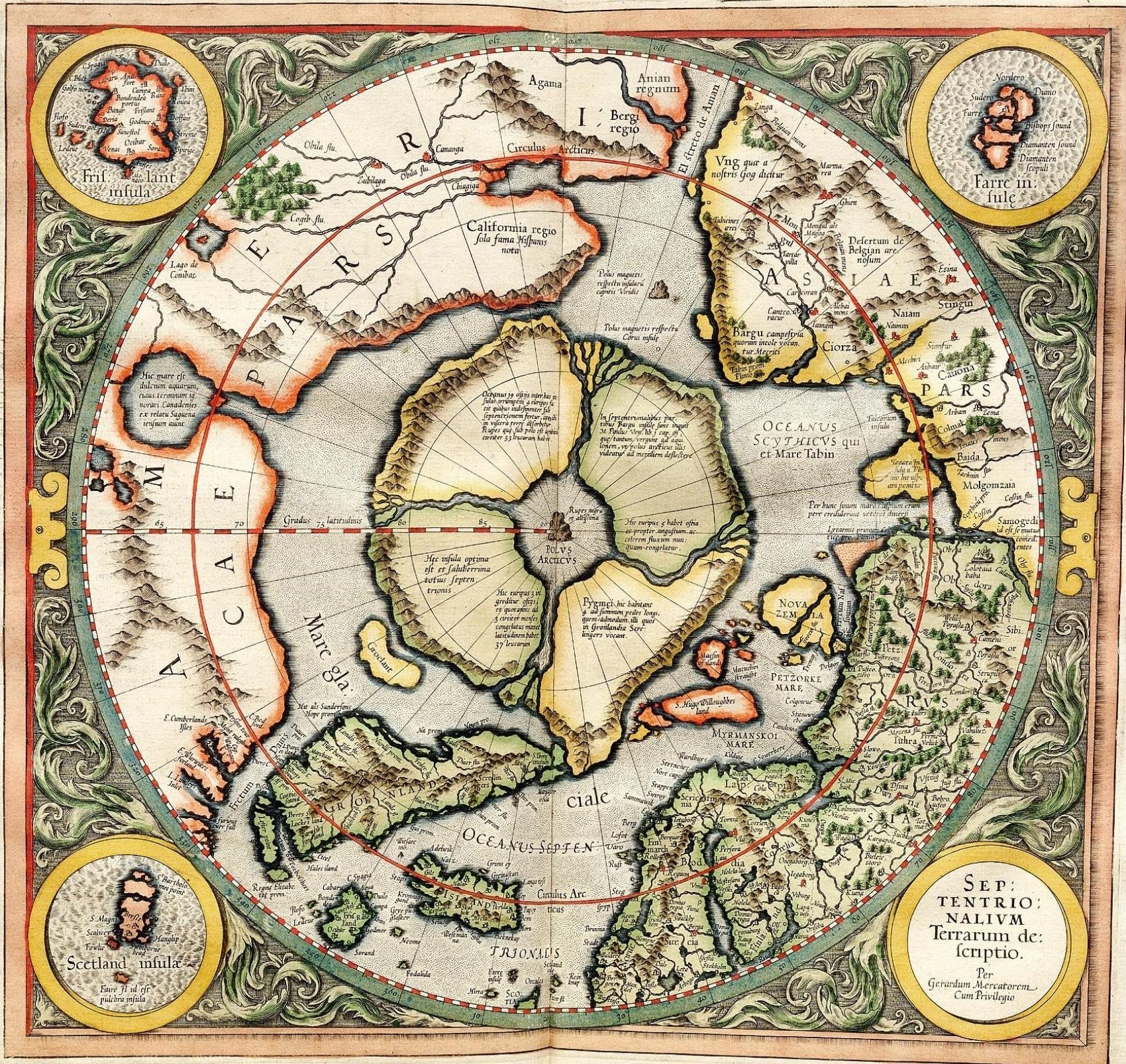

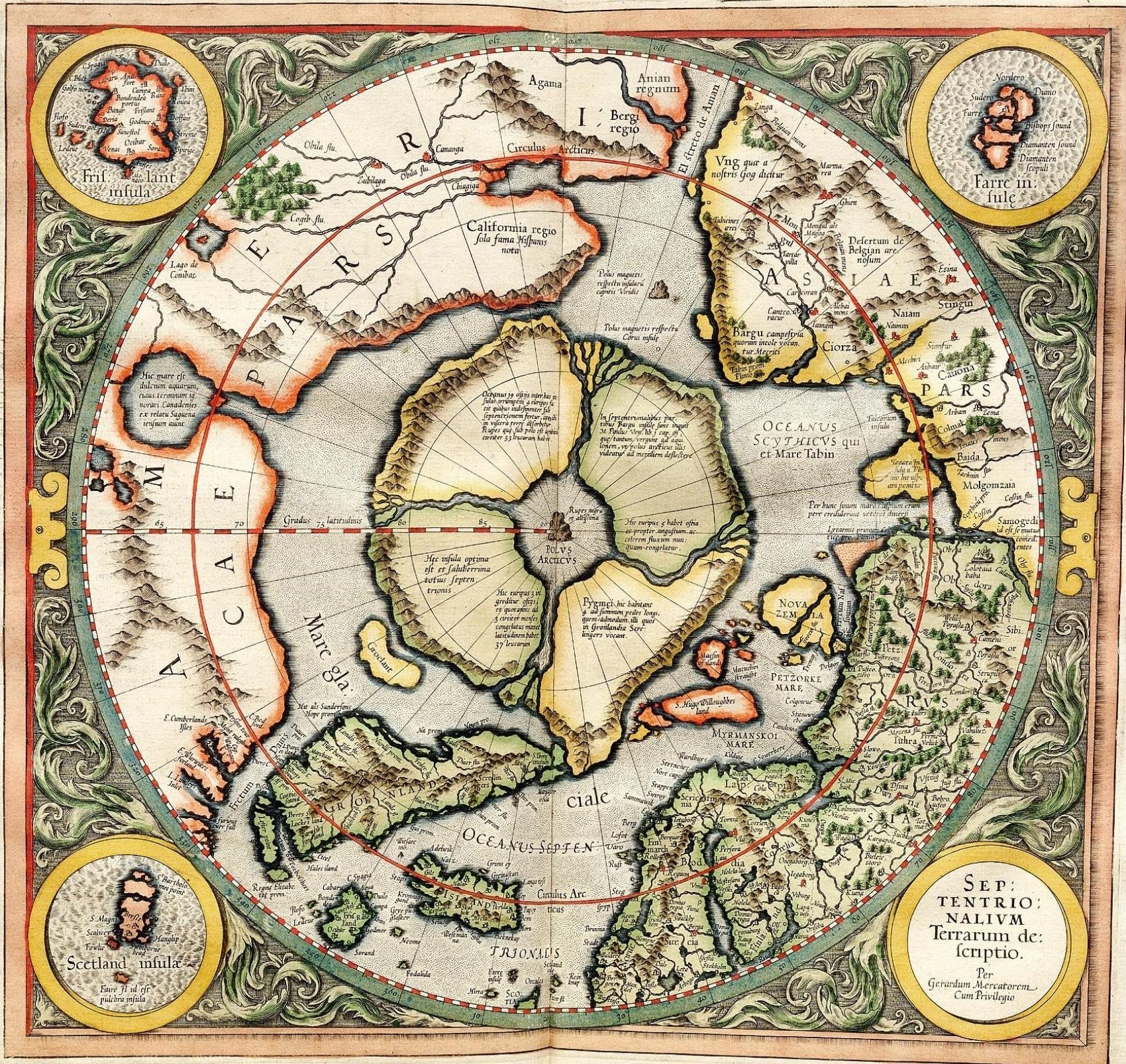

As early as the 16th century, many prominent people correctly believed that the North Pole was in a sea, which in the 19th century was called the

As early as the 16th century, many prominent people correctly believed that the North Pole was in a sea, which in the 19th century was called the  In April 1895, the Norwegian explorers

In April 1895, the Norwegian explorers

The U.S. explorer

The U.S. explorer  The distances and speeds that Peary claimed to have achieved once the last support party turned back seem incredible to many people, almost three times that which he had accomplished up to that point. Peary's account of a journey to the Pole and back while traveling along the direct line – the only strategy that is consistent with the time constraints that he was facing – is contradicted by Henson's account of tortuous detours to avoid

The distances and speeds that Peary claimed to have achieved once the last support party turned back seem incredible to many people, almost three times that which he had accomplished up to that point. Peary's account of a journey to the Pole and back while traveling along the direct line – the only strategy that is consistent with the time constraints that he was facing – is contradicted by Henson's account of tortuous detours to avoid

Sir Wally Herbert

''The Guardian''. Because of suggestions (later proven false) of Plaisted's use of air transport, some sources classify Herbert's expedition as the first confirmed to reach the North Pole over the ice surface by any means. In the 1980s Plaisted's pilots Weldy Phipps and Ken Lee signed affidavits asserting that no such airlift was provided. It is also said that Herbert was the first person to reach the On 17 August 1977 the Soviet nuclear-powered icebreaker '' Arktika'' completed the first surface vessel journey to the North Pole.

In 1982 Ranulph Fiennes and Charles R. Burton became the first people to cross the Arctic Ocean in a single season. They departed from Cape Crozier,

On 17 August 1977 the Soviet nuclear-powered icebreaker '' Arktika'' completed the first surface vessel journey to the North Pole.

In 1982 Ranulph Fiennes and Charles R. Burton became the first people to cross the Arctic Ocean in a single season. They departed from Cape Crozier,

On April 16, 1990, a German-Swiss expedition led by a team of the

On April 16, 1990, a German-Swiss expedition led by a team of the

On 2 August 2007 a Russian scientific expedition Arktika 2007 made the first ever manned descent to the ocean floor at the North Pole, to a depth of , as part of the research programme in support of Russia's 2001 extended continental shelf claim to a large swathe of the Arctic Ocean floor. The descent took place in two MIR submersibles and was led by Soviet and Russian polar explorer

On 2 August 2007 a Russian scientific expedition Arktika 2007 made the first ever manned descent to the ocean floor at the North Pole, to a depth of , as part of the research programme in support of Russia's 2001 extended continental shelf claim to a large swathe of the Arctic Ocean floor. The descent took place in two MIR submersibles and was led by Soviet and Russian polar explorer

, BBC News (2 August 2007). The expedition was the latest in a series of efforts intended to give Russia a dominant influence in the

On 1 March 2013 the Russian Marine Live-Ice Automobile Expedition (MLAE 2013) with Vasily Elagin as a leader, and a team of Afanasy Makovnev, Vladimir Obikhod, Alexey Shkrabkin, Andrey Vankov, Sergey Isayev and Nikolay Kozlov on two custom-built 6 x 6 low-pressure-tire ATVs—Yemelya-3 and Yemelya-4—started from Golomyanny Island (the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago) to the North Pole across drifting ice of the Arctic Ocean. The vehicles reached the Pole on 6 April and then continued to the Canadian coast. The coast was reached on 30 April 2013 (83°08N, 075°59W Ward Hunt Island), and on 5 May 2013 the expedition finished in Resolute Bay, NU. The way between the Russian borderland (Machtovyi Island of the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago, 80°15N, 097°27E) and the Canadian coast (Ward Hunt Island, 83°08N, 075°59W) took 55 days; it was ~2300 km across drifting ice and about 4000 km in total. The expedition was totally self-dependent and used no external supplies. The expedition was supported by the

On 1 March 2013 the Russian Marine Live-Ice Automobile Expedition (MLAE 2013) with Vasily Elagin as a leader, and a team of Afanasy Makovnev, Vladimir Obikhod, Alexey Shkrabkin, Andrey Vankov, Sergey Isayev and Nikolay Kozlov on two custom-built 6 x 6 low-pressure-tire ATVs—Yemelya-3 and Yemelya-4—started from Golomyanny Island (the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago) to the North Pole across drifting ice of the Arctic Ocean. The vehicles reached the Pole on 6 April and then continued to the Canadian coast. The coast was reached on 30 April 2013 (83°08N, 075°59W Ward Hunt Island), and on 5 May 2013 the expedition finished in Resolute Bay, NU. The way between the Russian borderland (Machtovyi Island of the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago, 80°15N, 097°27E) and the Canadian coast (Ward Hunt Island, 83°08N, 075°59W) took 55 days; it was ~2300 km across drifting ice and about 4000 km in total. The expedition was totally self-dependent and used no external supplies. The expedition was supported by the

. ''yemelya.ru''.

The North Pole is substantially warmer than the

The North Pole is substantially warmer than the

un.org (4 June 2007).), Russia (ratified in 1997), Canada (ratified in 2003) and Denmark (ratified in 2004) have all launched projects to base claims that certain areas of Arctic continental shelves should be subject to their sole sovereign exploitation. In 1907 Canada invoked the " sector principle" to claim sovereignty over a sector stretching from its coasts to the North Pole. This claim has not been relinquished, but was not consistently pressed until 2013.

Arctic Council

The Northern Forum

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1XMZTzELaE Video of the Nuclear Icebreaker Yamal visiting the North Pole in 2001

Polar Discovery: North Pole Observatory Expedition

{{Authority control Extreme points of Earth Northern Canada Navigation Polar regions of the Earth Geography of the Arctic Northern Hemisphere

Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Magnetic North Pole.

The North Pole is by definition the northernmost point on the Earth, lying antipodally to the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

. It defines geodetic latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

90° North, as well as the direction of true north

True north is the direction along Earth's surface towards the place where the imaginary rotational axis of the Earth intersects the surface of the Earth on its Northern Hemisphere, northern half, the True North Pole. True south is the direction ...

. At the North Pole all directions point south; all lines of longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

converge there, so its longitude can be defined as any degree value. No time zone has been assigned to the North Pole, so any time can be used as the local time. Along tight latitude circles, counterclockwise is east and clockwise is west. The North Pole is at the center of the Northern Hemisphere. The nearest land is usually said to be Kaffeklubben Island, off the northern coast of Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

about away, though some perhaps semi-permanent gravel banks lie slightly closer. The nearest permanently inhabited place is Alert on Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

, Canada, which is located from the Pole.

While the South Pole lies on a continental land mass

A landmass, or land mass, is a large region or area of land that is in one piece and not noticeably broken up by oceans. The term is often used to refer to lands surrounded by an ocean or sea, such as a continent or a large island. In the fiel ...

, the North Pole is located in the middle of the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

amid waters that are almost permanently covered with constantly shifting sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

. The sea depth at the North Pole has been measured at by the Russian Mir submersible in 2007

2007 was designated as the International Heliophysical Year and the International Polar Year.

Events

January

* January 1

**Bulgaria and Romania 2007 enlargement of the European Union, join the European Union, while Slovenia joins the Eur ...

and at by USS ''Nautilus'' in 1958. This makes it impractical to construct a permanent station at the North Pole ( unlike the South Pole). However, the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and later Russia, constructed a number of manned drifting stations on a generally annual basis since 1937, some of which have passed over or very close to the Pole. Since 2002, a group of Russians have also annually established a private base, Barneo, close to the Pole. This operates for a few weeks during early spring. Studies in the 2000s predicted that the North Pole may become seasonally ice-free because of Arctic ice shrinkage, with timescales varying from 2016 to the late 21st century or later.

Attempts to reach the North Pole began in the late 19th century, with the record for " Farthest North" being surpassed on numerous occasions. The first undisputed expedition to reach the North Pole was that of the airship '' Norge'', which overflew the area in 1926 with 16 men on board, including expedition leader Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

. Three prior expeditions – led by Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician and ethnographer, who is most known for allegedly being the first to reach the North Pole on April 21, 1908. A competing claim was made a year l ...

(1908, land), Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was long credited as being ...

(1909, land) and Richard E. Byrd (1926, aerial) – were once also accepted as having reached the Pole. However, in each case later analysis of expedition data has cast doubt upon the accuracy of their claims.

The first verified individuals to reach the North Pole on foot was in 1948 by a 24-man Soviet party, part of Aleksandr Kuznetsov's ''Sever-2'' expedition to the Arctic, who flew near to the Pole first before making the final trek to the Pole on foot. The first complete land expedition to reach the North Pole was in 1968 by Ralph Plaisted

Ralph Summers Plaisted (September 30, 1927 – September 8, 2008) was an American explorer who, with his three companions, Walt Pederson, Gerry Pitzl and Jean-Luc Bombardier, are regarded by most polar authorities to be the first to succeed in a s ...

, Walt Pederson, Gerry Pitzl and Jean-Luc Bombardier, using snowmobiles and with air support.

Precise definition

The Earth's axis of rotation – and hence the position of the North Pole – was commonly believed to be fixed (relative to the surface of the Earth) until, in the 18th century, the mathematicianLeonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( ; ; ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss polymath who was active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician, geographer, and engineer. He founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made influential ...

predicted that the axis might "wobble" slightly. Around the beginning of the 20th century astronomers noticed a small apparent "variation of latitude", as determined for a fixed point on Earth from the observation of stars. Part of this variation could be attributed to a wandering of the Pole across the Earth's surface, by a range of a few metres. The wandering has several periodic components and an irregular component. The component with a period of about 435 days is identified with the eight-month wandering predicted by Euler and is now called the Chandler wobble

The Chandler wobble or Chandler variation of latitude is a small deviation in the Earth's axis of rotation relative to the solid earth, which was discovered by and named after American astronomer Seth Carlo Chandler in 1891. It amounts to change ...

after its discoverer. The exact point of intersection of the Earth's axis and the Earth's surface, at any given moment, is called the "instantaneous pole", but because of the "wobble" this cannot be used as a definition of a fixed North Pole (or South Pole) when metre-scale precision is required.

It is desirable to tie the system of Earth coordinates (latitude, longitude, and elevations or orography) to fixed landforms. However, given plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

and isostasy

Isostasy (Greek wikt:ἴσος, ''ísos'' 'equal', wikt:στάσις, ''stásis'' 'standstill') or isostatic equilibrium is the state of gravity, gravitational mechanical equilibrium, equilibrium between Earth's crust (geology), crust (or lithosph ...

, there is no system in which all geographic features are fixed. Yet the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service

The International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), formerly the International Earth Rotation Service, is the body responsible for maintaining global time and reference frame standards, notably through its Earth Orientation P ...

and the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; , UAI) is an international non-governmental organization (INGO) with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach, education, and developmen ...

have defined a framework called the International Terrestrial Reference System

The International Terrestrial Reference System (ITRS) describes procedures for creating frame of reference, reference frames suitable for use with measurements on or near the Earth's surface. This is done in much the same way that a Standard (metr ...

.

Exploration

Pre-1900

As early as the 16th century, many prominent people correctly believed that the North Pole was in a sea, which in the 19th century was called the

As early as the 16th century, many prominent people correctly believed that the North Pole was in a sea, which in the 19th century was called the Polynya

A polynya () is an area of open water surrounded by sea ice. It is now used as a geographical term for an area of unfrozen seawater within otherwise contiguous pack ice or fast ice. It is a loanword from the Russian language, Russian (), whic ...

or Open Polar Sea. It was therefore hoped that passage could be found through ice floes at favorable times of the year. Several expeditions set out to find the way, generally with whaling ships, already commonly used in the cold northern latitudes.

One of the earliest expeditions to set out with the explicit intention of reaching the North Pole was that of British naval officer William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Passa ...

, who in 1827 reached latitude 82°45′ North. In 1871, the ''Polaris'' expedition, a U.S. attempt on the Pole led by Charles Francis Hall, ended in disaster. Another British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

attempt to get to the pole, part of the British Arctic Expedition

The British Arctic Expedition of 1875–1876, led by Sir George Nares, was sent by the Admiralty (United Kingdom), British Admiralty to attempt to reach the North Pole via Smith Sound on the west coast of Greenland.

Although the expedition fail ...

, by Commander Albert H. Markham reached a then-record 83°20'26" North in May 1876 before turning back. An 1879–1881 expedition commanded by U.S. Navy officer George W. De Long ended tragically when their ship, the , was crushed by ice. Over half the crew, including De Long, were lost.

In April 1895, the Norwegian explorers

In April 1895, the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and co-founded the ...

and Hjalmar Johansen struck out for the Pole on skis after leaving Nansen's icebound ship '' Fram''. The pair reached latitude 86°14′ North before they abandoned the attempt and turned southwards, eventually reaching Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land () is a Russian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It is inhabited only by military personnel. It constitutes the northernmost part of Arkhangelsk Oblast and consists of 192 islands, which cover an area of , stretching from east ...

.

In 1897, Swedish engineer Salomon August Andrée and two companions tried to reach the North Pole in the hydrogen balloon ''Örnen'' ("Eagle"), but came down north of Kvitøya, the northeasternmost part of the Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

archipelago. They trekked to Kvitøya but died there three months after their crash. In 1930 the remains of this expedition were found by the Norwegian Bratvaag Expedition.

The Italian explorer Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi and Captain Umberto Cagni of the Italian Royal Navy () sailed the converted whaler '' Stella Polare'' ("Pole Star") from Norway in 1899. On 11 March 1900, Cagni led a party over the ice and reached latitude 86° 34’ on 25 April, setting a new record by beating Nansen's result of 1895 by . Cagni barely managed to return to the camp, remaining there until 23 June. On 16 August, the ''Stella Polare'' left Rudolf Island heading south and the expedition returned to Norway.

1900–1940

The U.S. explorer

The U.S. explorer Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician and ethnographer, who is most known for allegedly being the first to reach the North Pole on April 21, 1908. A competing claim was made a year l ...

claimed to have reached the North Pole on 21 April 1908 with two Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

men, Ahwelah and Etukishook, but he was unable to produce convincing proof and his claim is not widely accepted.

The conquest of the North Pole was for many years credited to U.S. Navy engineer Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was long credited as being ...

, who claimed to have reached the Pole on 6 April 1909, accompanied by Matthew Henson and four Inuit men, Ootah, Seeglo, Egingwah, and Ooqueah. However, Peary's claim remains highly disputed and controversial. Those who accompanied Peary on the final stage of the journey were not trained in navigation, and thus could not independently confirm his navigational work, which some claim to have been particularly sloppy as he approached the Pole.

The distances and speeds that Peary claimed to have achieved once the last support party turned back seem incredible to many people, almost three times that which he had accomplished up to that point. Peary's account of a journey to the Pole and back while traveling along the direct line – the only strategy that is consistent with the time constraints that he was facing – is contradicted by Henson's account of tortuous detours to avoid

The distances and speeds that Peary claimed to have achieved once the last support party turned back seem incredible to many people, almost three times that which he had accomplished up to that point. Peary's account of a journey to the Pole and back while traveling along the direct line – the only strategy that is consistent with the time constraints that he was facing – is contradicted by Henson's account of tortuous detours to avoid pressure ridge

A pressure ridge is a topographic ridge produced by compression.

Depending on the affected material, "pressure ridge" may refer to:

* Pressure ridge (ice), between ice floes

* Pressure ridge (lava), in a lava flow

* Pressure ridge (seismic), ...

s and open leads.

The British explorer Wally Herbert, initially a supporter of Peary, researched Peary's records in 1989 and found that there were significant discrepancies in the explorer's navigational records. He concluded that Peary had not reached the Pole. Support for Peary came again in 2005, however, when British explorer Tom Avery and four companions recreated the outward portion of Peary's journey with replica wooden sleds and Canadian Eskimo Dog teams, reaching the North Pole in 36 days, 22 hours – nearly five hours faster than Peary. However, Avery's fastest 5-day march was , significantly short of the claimed by Peary. Avery writes on his web site that "The admiration and respect which I hold for Robert Peary, Matthew Henson and the four Inuit men who ventured North in 1909, has grown enormously since we set out from Cape Columbia

Cape Columbia is the northernmost point of land of Canada, located on Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut. It marks the westernmost coastal point of Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is the world's northernmost point of l ...

. Having now seen for myself how he travelled across the pack ice, I am more convinced than ever that Peary did indeed discover the North Pole."

The first claimed flight over the Pole was made on 9 May 1926 by U.S. naval officer Richard E. Byrd and pilot Floyd Bennett in a Fokker tri-motor aircraft. Although verified at the time by a committee of the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

, this claim has since been undermined by the 1996 revelation that Byrd's long-hidden diary's solar sextant

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects. The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of cel ...

data (which the NGS never checked) consistently contradict his June 1926 report's parallel data by over . The secret report's alleged en-route solar sextant data were inadvertently so impossibly overprecise that he excised all these alleged raw solar observations out of the version of the report finally sent to geographical societies five months later (while the original version was hidden for 70 years), a realization first published in 2000 by the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

after scrupulous refereeing.

The first consistent, verified, and scientifically convincing attainment of the Pole was on 12 May 1926, by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

and his U.S. sponsor Lincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth (May 12, 1880 – May 26, 1951) was an American polar explorer, engineer, surveyor, and author. He led the first Arctic and Antarctic air crossings.

Early life

Linn Ellsworth was born in Chicago, Illinois on May 12, 1880. His ...

from the airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

'' Norge''. ''Norge'', though Norwegian-owned, was designed and piloted by the Italian Umberto Nobile

Umberto Nobile (; 21 January 1885 – 30 July 1978) was an Italian aviator, aeronautical engineer and Arctic explorer.

Nobile was a developer and promoter of semi-rigid airships in the Aviation between the World Wars, years between the two Worl ...

. The flight started from Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

in Norway, and crossed the Arctic Ocean to Alaska. Nobile, with several scientists and crew from the ''Norge'', overflew the Pole a second time on 24 May 1928, in the airship ''Italia

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

''. The ''Italia'' crashed on its return from the Pole, with the loss of half the crew.

Another transpolar flight was accomplished in a Tupolev ANT-25

The Tupolev ANT-25 was a Soviet long-range experimental aircraft which was also tried as a bomber. First constructed in 1933, it was used by the Soviet Union for a number of record-breaking flights.

Development

The ANT-25 was designed as the r ...

airplane with a crew of Valery Chkalov

Valery Pavlovich Chkalov (; ; – 15 December 1938) was a test pilot awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union (1936).

Early life

Chkalov was born to a Russian family in 1904 in the upper Volga region, the town of Chkalovsk, Russia, Vasi ...

, Georgy Baydukov and Alexander Belyakov, who flew over the North Pole on 19 June 1937, during their direct flight from the Soviet Union to the USA without any stopover.

Ice station

In May 1937 the world's first North Pole ice station, North Pole-1, was established by Soviet scientists 20 kilometres (13 mi) from the North Pole after the ever first landing of four heavy and one light aircraft onto the ice at the North Pole. The expedition members — oceanographer Pyotr Shirshov, meteorologist Yevgeny Fyodorov, radio operator Ernst Krenkel, and the leader Ivan Papanin — conducted scientific research at the station for the next nine months. By 19 February 1938, when the group was picked up by the ice breakers '' Taimyr'' and ''Murman'', their station had drifted 2850 km to the eastern coast of Greenland.1940–2000

In May 1945 an RAF Lancaster of the ''Aries'' expedition became the firstCommonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

aircraft to overfly the North Geographic and North Magnetic Poles. The plane was piloted by David Cecil McKinley of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

. It carried an 11-man crew, with Kenneth C. Maclure of the Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; ) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environmental commands within the unified Can ...

in charge of all scientific observations. In 2006, Maclure was honoured with a spot in Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame.

Discounting Peary's disputed claim, the first men to set foot at the North Pole were a Soviet party including geophysicists Mikhail Ostrekin and Pavel Senko, oceanographers Mikhail Somov and Pavel Gordienko, and other scientists and flight crew (24 people in total) of Aleksandr Kuznetsov's ''Sever-2'' expedition (March–May 1948). It was organized by the Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route

The Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route (), also known as Glavsevmorput or GUSMP (), was a Soviet government organization in charge of the maritime Northern Sea Route, established in January 1932 and dissolved in 1964.

History

The organiz ...

. The party flew on three planes (pilots Ivan Cherevichnyy, Vitaly Maslennikov and Ilya Kotov) from Kotelny Island to the North Pole and landed there at 4:44pm (Moscow Time

Moscow Time (MSK; ) is the time zone for the city of Moscow, Russia, and most of western Russia, including Saint Petersburg. It is the second-westernmost of the eleven time zones of Russia, after the non-continguous Kaliningrad enclave. It h ...

, UTC+04:00) on 23 April 1948. They established a temporary camp and for the next two days conducted scientific observations. On 26 April the expedition flew back to the continent.

Next year, on 9 May 1949 two other Soviet scientists (Vitali Volovich and Andrei Medvedev) became the first people to parachute onto the North Pole. They jumped from a Douglas C-47 Skytrain

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota ( RAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II. During the war the C-47 was used for tro ...

, registered CCCP H-369.

On 3 May 1952, U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Joseph O. Fletcher and Lieutenant William Pershing Benedict, along with scientist Albert P. Crary, landed a modified Douglas C-47 Skytrain

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota ( RAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II. During the war the C-47 was used for tro ...

at the North Pole. Some Western sources considered this to be the first landing at the Pole until the Soviet landings became widely known.

The United States Navy submarine '' USS Nautilus'' (SSN-571) crossed the North Pole on 3 August 1958. On 17 March 1959 '' USS Skate'' (SSN-578) surfaced at the Pole, breaking through the ice above it, becoming the first naval vessel to do so.

The first confirmed surface conquest of the North Pole was accomplished by Ralph Plaisted

Ralph Summers Plaisted (September 30, 1927 – September 8, 2008) was an American explorer who, with his three companions, Walt Pederson, Gerry Pitzl and Jean-Luc Bombardier, are regarded by most polar authorities to be the first to succeed in a s ...

, Walt Pederson, Gerry Pitzl and Jean Luc Bombardier, who traveled over the ice by snowmobile

A snowmobile, also known as a snowmachine (chiefly Alaskan), motor sled (chiefly Canadian), motor sledge, skimobile, snow scooter, or simply a sled is a motorized vehicle designed for winter travel and recreation on snow.

Their engines normally ...

and arrived on 19 April 1968. The United States Air Force independently confirmed their position.

On 6 April 1969 Wally Herbert and companions Allan Gill, Roy Koerner and Kenneth Hedges of the British Trans-Arctic Expedition became the first men to reach the North Pole on foot (albeit with the aid of dog teams and airdrop

An airdrop is a type of airlift in which items including weapons, equipment, humanitarian aid or leaflets are delivered by military or civilian aircraft without their landing. Developed during World War II to resupply otherwise inaccessible tr ...

s). They continued on to complete the first surface crossing of the Arctic Ocean – and by its longest axis, Barrow, Alaska, to Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

– a feat that has never been repeated.Bob Headland (15 June 2007)Sir Wally Herbert

''The Guardian''. Because of suggestions (later proven false) of Plaisted's use of air transport, some sources classify Herbert's expedition as the first confirmed to reach the North Pole over the ice surface by any means. In the 1980s Plaisted's pilots Weldy Phipps and Ken Lee signed affidavits asserting that no such airlift was provided. It is also said that Herbert was the first person to reach the

pole of inaccessibility

In geography, a pole of inaccessibility is the farthest (or most difficult to reach) location in a given landmass, sea, or other topographical feature, starting from a given boundary, relative to a given criterion. A geographical criterion of i ...

.

On 17 August 1977 the Soviet nuclear-powered icebreaker '' Arktika'' completed the first surface vessel journey to the North Pole.

In 1982 Ranulph Fiennes and Charles R. Burton became the first people to cross the Arctic Ocean in a single season. They departed from Cape Crozier,

On 17 August 1977 the Soviet nuclear-powered icebreaker '' Arktika'' completed the first surface vessel journey to the North Pole.

In 1982 Ranulph Fiennes and Charles R. Burton became the first people to cross the Arctic Ocean in a single season. They departed from Cape Crozier, Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

, on 17 February 1982 and arrived at the geographic North Pole on 10 April 1982. They travelled on foot and snowmobile. From the Pole, they travelled towards Svalbard but, due to the unstable nature of the ice, ended their crossing at the ice edge after drifting south on an ice floe for 99 days. They were eventually able to walk to their expedition ship ''MV Benjamin Bowring'' and boarded it on 4 August 1982 at position 80:31N 00:59W. As a result of this journey, which formed a section of the three-year Transglobe Expedition 1979–1982, Fiennes and Burton became the first people to complete a circumnavigation of the world via both North and South Poles, by surface travel alone. This achievement remains unchallenged to this day. The expedition crew included a Jack Russell Terrier named Bothie who became the first dog to visit both poles.

In 1985 Sir Edmund Hillary (the first man to stand on the summit of Mount Everest) and Neil Armstrong

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut and aerospace engineering, aeronautical engineer who, in 1969, became the Apollo 11#Lunar surface operations, first person to walk on the Moon. He was al ...

(the first man to stand on the moon) landed at the North Pole in a small twin-engined ski plane. Hillary thus became the first man to stand at both poles and on the summit of Everest.

In 1986 Will Steger, with seven teammates, became the first to be confirmed as reaching the Pole by dogsled and without resupply.

USS ''Gurnard'' (SSN-662) operated in the Arctic Ocean under the polar ice cap from September to November 1984 in company with one of her sister ships, the attack submarine USS ''Pintado'' (SSN-672). On 12 November 1984 ''Gurnard'' and ''Pintado'' became the third pair of submarines to surface together at the North Pole. In March 1990, ''Gurnard'' deployed to the Arctic region during exercise Ice Ex '90 and completed only the fourth winter submerged transit of the Bering and Seas. ''Gurnard'' surfaced at the North Pole on 18 April, in the company of the USS ''Seahorse'' (SSN-669).

On 6 May 1986 USS ''Archerfish'' (SSN 678), USS ''Ray'' (SSN 653) and USS ''Hawkbill'' (SSN-666) surfaced at the North Pole, the first tri-submarine surfacing at the North Pole.

On 21 April 1987 Shinji Kazama of Japan became the first person to reach the North Pole on a motorcycle

A motorcycle (motorbike, bike; uni (if one-wheeled); trike (if three-wheeled); quad (if four-wheeled)) is a lightweight private 1-to-2 passenger personal motor vehicle Steering, steered by a Motorcycle handlebar, handlebar from a saddle-style ...

.

On 18 May 1987 USS ''Billfish'' (SSN 676), USS ''Sea Devil'' (SSN 664) and HMS ''Superb'' (S 109) surfaced at the North Pole, the first international surfacing at the North Pole.

In 1988 a team of 13 (9 Soviets, 4 Canadians) skied across the arctic from Siberia to northern Canada. One of the Canadians, Richard Weber, became the first person to reach the Pole from both sides of the Arctic Ocean.

On April 16, 1990, a German-Swiss expedition led by a team of the

On April 16, 1990, a German-Swiss expedition led by a team of the University of Giessen

University of Giessen, official name Justus Liebig University Giessen (), is a large public research university in Giessen, Hesse, Germany. It is one of the oldest institutions of higher education in the German-speaking world. It is named afte ...

reached the Geographic North Pole for studies on pollution of pack ice

Pack or packs may refer to:

Music

* Packs (band), a Canadian indie rock band

* ''Packs'' (album), by Your Old Droog

* ''Packs'', a Berner album

Places

* Pack, Styria, defunct Austrian municipality

* Pack, Missouri, United States (US)

* ...

, snow and air. Samples taken were analyzed in cooperation with the Geological Survey of Canada

The Geological Survey of Canada (GSC; , CGC) is a Canadian federal government agency responsible for performing geological surveys of the country developing Canada's natural resources and protecting the environment. A branch of the Earth Science ...

and the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research. Further stops for sample collections were on multi-year sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

at 86°N, at Cape Columbia

Cape Columbia is the northernmost point of land of Canada, located on Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut. It marks the westernmost coastal point of Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is the world's northernmost point of l ...

and Ward Hunt Island.

On 4 May 1990 Børge Ousland

Børge Ousland (born 31 May 1962) is a Norwegian polar explorer. He was the first person to cross Antarctica solo.

He started his career as a Norwegian Navy Special Forces Officer with Marinejegerkommandoen, and he also spent several years wor ...

and Erling Kagge became the first explorers ever to reach the North Pole unsupported, after a 58-day ski trek from Ellesmere Island in Canada, a distance of 800 km.

On 7 September 1991 the German research vessel ''Polarstern'' and the Swedish icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

''Oden'' reached the North Pole as the first conventional powered vessels. Both scientific parties and crew took oceanographic and geological samples and had a common tug of war

Tug of war (also known as tug o' war, tug war, rope war, rope pulling, or tugging war) is a sport in which two teams compete by pulling on opposite ends of a rope, with the goal of bringing the rope a certain distance in one direction against ...

and a football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

game on an ice floe. ''Polarstern'' again reached the pole exactly 10 years later, with the ''Healy''.

In 1998, 1999, and 2000, Lada Niva

The Lada Niva Legend, formerly called the Lada Niva, VAZ-2121, VAZ-2131, and Lada 4×4 (), is a series of four-wheel drive, small (hatchback), and compact (wagon and pickup) Off-road vehicle, off-road cars designed and produced by AvtoVAZ sinc ...

Marshs (special very large wheeled versions made by BRONTO, Lada/Vaz's experimental product division) were driven to the North Pole. The 1998 expedition was dropped by parachute and completed the track to the North Pole. The 2000 expedition departed from a Russian research base around 114 km from the Pole and claimed an average speed of 20–15 km/h in an average temperature of −30 °C.

21st century

Commercial airliner flights on the polar routes may pass within viewing distance of the North Pole. For example, a flight fromChicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

to Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

may come close as latitude 89° N, though because of prevailing winds return journeys go over the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

. In recent years journeys to the North Pole by air (landing by helicopter or on a runway prepared on the ice) or by icebreaker have become relatively routine, and are even available to small groups of tourists through adventure holiday companies. Parachute jumps have frequently been made onto the North Pole in recent years. The temporary seasonal Russian camp of Barneo has been established by air a short distance from the Pole annually since 2002, and caters for scientific researchers as well as tourist parties. Trips from the camp to the Pole itself may be arranged overland or by helicopter.

The first attempt at underwater

An underwater environment is a environment of, and immersed in, liquid water in a natural or artificial feature (called a Water, body of water), such as an ocean, sea, lake, pond, reservoir, river, canal, or aquifer. Some characteristics of the ...

exploration of the North Pole was made on 22 April 1998 by Russian firefighter and diver Andrei Rozhkov with the support of the Diving Club of Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

, but ended in fatality. The next attempted dive at the North Pole was organized the next year by the same diving club, and ended in success on 24 April 1999. The divers were Michael Wolff (Austria), Brett Cormick (UK), and Bob Wass (USA).

In 2005 the United States Navy submarine USS ''Charlotte'' (SSN-766) surfaced through of ice at the North Pole and spent 18 hours there.

In July 2007 British endurance swimmer Lewis Gordon Pugh completed a swim at the North Pole. His feat, undertaken to highlight the effects of global warming, took place in clear water that had opened up between the ice floes. His later attempt to paddle a kayak

]

A kayak is a small, narrow human-powered watercraft typically propelled by means of a long, double-bladed paddle. The word ''kayak'' originates from the Inuktitut word '' qajaq'' (). In British English, the kayak is also considered to be ...

to the North Pole in late 2008, following the erroneous prediction of clear water to the Pole, was stymied when his expedition found itself stuck in thick ice after only three days. The expedition was then abandoned.

By September 2007 the North Pole had been visited 66 times by different surface ships: 54 times by Soviet and Russian icebreakers, 4 times by Swedish ''Oden'', 3 times by German ''Polarstern'', 3 times by USCGC Healy (WAGB-20), USCGC ''Healy'' and USCGC ''Polar Sea'', and once by CCGS ''Louis S. St-Laurent'' and by Swedish '' Vidar Viking''.

2007 descent to the North Pole seabed

On 2 August 2007 a Russian scientific expedition Arktika 2007 made the first ever manned descent to the ocean floor at the North Pole, to a depth of , as part of the research programme in support of Russia's 2001 extended continental shelf claim to a large swathe of the Arctic Ocean floor. The descent took place in two MIR submersibles and was led by Soviet and Russian polar explorer

On 2 August 2007 a Russian scientific expedition Arktika 2007 made the first ever manned descent to the ocean floor at the North Pole, to a depth of , as part of the research programme in support of Russia's 2001 extended continental shelf claim to a large swathe of the Arctic Ocean floor. The descent took place in two MIR submersibles and was led by Soviet and Russian polar explorer Artur Chilingarov

Artur Nikolaevich Chilingarov (; 25 September 1939 – 1 June 2024) was an Armenian-Russian polar explorer, a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union in 1986 and the title of ...

. In a symbolic act of visitation, the Russian flag was placed on the ocean floor exactly at the Pole.Russia plants flag under N Pole, BBC News (2 August 2007). The expedition was the latest in a series of efforts intended to give Russia a dominant influence in the

Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

according to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

''.

MLAE 2009 Expedition

In 2009 the Russian Marine Live-Ice Automobile Expedition (MLAE-2009) with Vasily Elagin as a leader and a team of Afanasy Makovnev, Vladimir Obikhod, Alexey Shkrabkin, Sergey Larin, Alexey Ushakov and Nikolay Nikulshin reached the North Pole on two custom-built 6 x 6 low-pressure-tire ATVs. The vehicles, Yemelya-1 and Yemelya-2, were designed by Vasily Elagin, a Russian mountain climber, explorer and engineer. They reached the North Pole on 26 April 2009, 17:30 (Moscow time). The expedition was partly supported by Russian State Aviation. The Russian Book of Records recognized it as the first successful vehicle trip from land to the Geographical North Pole.MLAE 2013 Expedition

Russian Geographical Society

The Russian Geographical Society (), or RGO, is a learned society based in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It promotes geography, exploration and nature protection with research programs in fields including oceanography, ethnography, ecology and stati ...

."Diary of MLAE-2013". ''yemelya.ru''.

Time and day and night

The sun at the North Pole is continuously above the horizon during the summer and continuously below the horizon during the winter.Sunrise

Sunrise (or sunup) is the moment when the upper rim of the Sun appears on the horizon in the morning, at the start of the Sun path. The term can also refer to the entire process of the solar disk crossing the horizon.

Terminology

Although the S ...

is just before the March equinox

The March equinox or northward equinox is the equinox on the Earth when the subsolar point appears to leave the Southern Hemisphere and cross the celestial equator, heading northward as seen from Earth. The March equinox is known as the ver ...

(around 20 March); the Sun then takes three months to reach its highest point of near 23½° elevation at the summer solstice

A solstice is the time when the Sun reaches its most northerly or southerly sun path, excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around 20–22 June and 20–22 December. In many countries ...

(around 21 June), after which time it begins to sink, reaching sunset

Sunset (or sundown) is the disappearance of the Sun at the end of the Sun path, below the horizon of the Earth (or any other astronomical object in the Solar System) due to its Earth's rotation, rotation. As viewed from everywhere on Earth, it ...

just after the September equinox

The September equinox (or southward equinox) is the moment when the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator, heading southward. Because of differences between the calendar year and the tropical year, the September equinox may occur from ...

(around 23 September). When the Sun is visible in the polar sky, it appears to move in a horizontal circle above the horizon. This circle gradually rises from near the horizon just after the vernal equinox to its maximum elevation (in degrees) above the horizon at summer solstice and then sinks back toward the horizon before sinking below it at the autumnal equinox. Hence the North and South Poles experience the slowest rates of sunrise and sunset on Earth.

The twilight

Twilight is daylight illumination produced by diffuse sky radiation when the Sun is below the horizon as sunlight from the upper atmosphere is scattered in a way that illuminates both the Earth's lower atmosphere and also the Earth's surf ...

period that occurs before sunrise and after sunset has three different definitions:

* a civil twilight period of about two weeks;

* a nautical twilight period of about five weeks; and

* an astronomical twilight period of about seven weeks.

These effects are caused by a combination of the Earth's axial tilt

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and orbita ...

and its revolution around the Sun. The direction of the Earth's axial tilt, as well as its angle relative to the plane of the Earth's orbit around the Sun, remains very nearly constant over the course of a year (both change very slowly over long time periods). At northern midsummer the North Pole is facing towards the Sun to its maximum extent. As the year progresses and the Earth moves around the Sun, the North Pole gradually turns away from the Sun until at midwinter it is facing away from the Sun to its maximum extent. A similar sequence is observed at the South Pole, with a six-month time difference.

Since longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

is undefined at the north pole, the exact time is a matter of convention. Polar expeditions use whatever time is most convenient, such as Greenwich Mean Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the local mean time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, counted from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being ...

or the time zone of their origin.

Climate, sea ice at North Pole

The North Pole is substantially warmer than the

The North Pole is substantially warmer than the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

because it lies at sea level in the middle of an ocean (which acts as a reservoir of heat), rather than at altitude on a continental land mass. Despite being an ice cap, the northernmost weather station in Greenland has a tundra climate (Köppen ''ET'') due to the July and August mean temperatures peaking just above freezing.

Winter temperatures at the northernmost weather station in Greenland can range from about , averaging around , with the North Pole being slightly colder. However, a freak storm caused the temperature to reach for a time at a World Meteorological Organization

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation on atmospheric science, climatology, hydrology an ...

buoy, located at 87.45°N, on 30 December 2015. It was estimated that the temperature at the North Pole was between during the storm. Summer temperatures (June, July, and August) average around the freezing point (). The highest temperature yet recorded is , much warmer than the South Pole's record high of only . A similar spike in temperatures occurred on 15 November 2016 when temperatures hit freezing. Yet again, February 2018 featured a storm so powerful that temperatures at Cape Morris Jesup, the world's northernmost weather station in Greenland, reached and spent 24 straight hours above freezing. Meanwhile, the pole itself was estimated to reach a high temperature of . This same temperature of was also recorded at the Hollywood Burbank Airport

Hollywood Burbank Airport is a public airport northwest of downtown Burbank, in Los Angeles County, California, United States.. Federal Aviation Administration. effective November 9, 2017 The airport serves Burbank, Hollywood, and the norther ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

at the very same time.

The sea ice at the North Pole is typically around thick, although ice thickness, its spatial extent, and the fraction of open water within the ice pack can vary rapidly and profoundly in response to weather and climate. Studies have shown that the average ice thickness has decreased in recent years. It is likely that global warming

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes ...

has contributed to this, but it is not possible to attribute the recent abrupt decrease in thickness entirely to the observed warming in the Arctic. Reports have also predicted that within a few decades the Arctic Ocean will be entirely free of ice in the summer. This may have significant commercial implications; see "Territorial claims", below.

The retreat of the Arctic sea ice will accelerate global warming, as less ice cover reflects less solar radiation, and may have serious climate implications by contributing to Arctic cyclone generation.

Flora and fauna

Polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a large bear native to the Arctic and nearby areas. It is closely related to the brown bear, and the two species can Hybrid (biology), interbreed. The polar bear is the largest extant species of bear ...

s are believed to travel rarely beyond about 82° North, owing to the scarcity of food, though tracks have been seen in the vicinity of the North Pole, and a 2006 expedition reported sighting a polar bear just from the Pole. The ringed seal has also been seen at the Pole, and Arctic fox

The Arctic fox (''Vulpes lagopus''), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small species of fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Tundra#Arctic tundra, Arctic tundra biome. I ...

es have been observed less than away at 89°40′ N.

Birds seen at or very near the Pole include the snow bunting

The snow bunting (''Plectrophenax nivalis'') is a passerine bird in the family Calcariidae. It is an Arctic specialist, with a circumpolar Arctic breeding range throughout the northern hemisphere. There are small isolated populations on a few ...

, northern fulmar and black-legged kittiwake, though some bird sightings may be distorted by the tendency of birds to follow ships and expeditions.

Fish have been seen in the waters at the North Pole, but these are probably few in number. A member of the Russian team that descended to the North Pole seabed in August 2007 reported seeing no sea creatures living there. However, it was later reported that a sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

had been scooped up from the seabed mud by the Russian team and that video footage from the dive showed unidentified shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion – typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

s and amphipods

Amphipoda () is an order (biology), order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods () range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 10,700 amphip ...

.

Territorial claims to the North Pole and Arctic regions

Currently, underinternational law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

, no country owns the North Pole or the region of the Arctic Ocean surrounding it. The five surrounding Arctic countries, Russia, Canada, Norway, Denmark (via Greenland), and the United States, are limited to a exclusive economic zone

An exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is an area of the sea in which a sovereign state has exclusive rights regarding the exploration and use of marine natural resource, reso ...

off their coasts, and the area beyond that is administered by the International Seabed Authority.

Upon ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international treaty that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 169 sov ...

, a country has 10 years to make claims to an extended continental shelf beyond its 200-mile exclusive economic zone. If validated, such a claim gives the claimant state rights to what may be on or beneath the sea bottom within the claimed zone. Norway (ratified the convention in 1996Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, of the Agreement relating to the implementation of Part XI of the Convention and of the Agreement for the implementation of the provisions of the Convention relating to the conservation and management of straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocksun.org (4 June 2007).), Russia (ratified in 1997), Canada (ratified in 2003) and Denmark (ratified in 2004) have all launched projects to base claims that certain areas of Arctic continental shelves should be subject to their sole sovereign exploitation. In 1907 Canada invoked the " sector principle" to claim sovereignty over a sector stretching from its coasts to the North Pole. This claim has not been relinquished, but was not consistently pressed until 2013.

Cultural associations

In some children'sChristmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a Religion, religious and Culture, cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by coun ...

legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

s and Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

, the geographic North Pole is described as the location of Santa Claus

Santa Claus (also known as Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Father Christmas, Kris Kringle or Santa) is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring gifts during the late evening and overnight hours on Chris ...

' workshop and residence. Canada Post

Canada Post Corporation (, trading as Canada Post (), is a Canadian Crown corporation that functions as the primary postal operator in Canada.

Originally known as Royal Mail Canada (the operating name of the Post Office Department of the Can ...

has assigned postal code H0H 0H0 to the North Pole (referring to Santa's traditional exclamation of " Ho ho ho!").

This association reflects an age-old esoteric mythology of Hyperborea

In Greek mythology, the Hyperboreans (, ; ) were a mythical people who lived in the far northern part of the Ecumene, known world. Their name appears to derive from the Greek , "beyond Boreas (god), Boreas" (the God of the north wind). Some schol ...

that posits the North Pole, the otherworldly world-axis, as the abode of God and superhuman beings.

As Henry Corbin has documented, the North Pole plays a key part in the cultural worldview of Sufism

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

and Iranian mysticism. "The Orient sought by the mystic, the Orient that cannot be located on our maps, is in the direction of the north, beyond the north.".

In Mandaean cosmology

Mandaean cosmology is the Gnostic conception of the universe in the religion of Mandaeism.

Mandaean cosmology is strongly influenced by ancient near eastern cosmology broadly and Jewish, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, Manichaean and other Near ...

, the North Pole and Polaris

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinisation of names, Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an ...

are considered to be auspicious, since they are associated with the World of Light

In Mandaeism, the World of Light or Lightworld () is the primeval, transcendental world from which Tibil and the World of Darkness emerged.

Description

*The Great Life ('' Hayyi Rabbi'' or Supreme God/ Monad) is the ruler of the World of Ligh ...

. Mandaeans

Mandaeans (Mandaic language, Mandaic: ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡉࡀ) ( ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and ...

face north when praying, and temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

are also oriented towards the north. On the contrary, South is associated with the World of Darkness

''World of Darkness'' is a series of tabletop role-playing games, originally created by Mark Rein-Hagen for White Wolf Publishing. It began as an annual line of five games in 1991–1995, with ''Vampire: The Masquerade'', ''Werewolf: The Apocaly ...

.

Owing to its remoteness, the Pole is sometimes identified with a mysterious mountain of ancient Iranian

Iranian () may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Iran

** Iranian diaspora, Iranians living outside Iran

** Iranian architecture, architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia

** Iranian cuisine, cooking traditions and practic ...

tradition called Mount Qaf (Jabal Qaf), the "farthest point of the earth". According to certain authors, the Jabal Qaf of Muslim cosmology is a version of Rupes Nigra, a mountain whose ascent, like Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

's climbing of the Mountain of Purgatory, represents the pilgrim's progress through spiritual states. In Iranian theosophy, the heavenly Pole, the focal point of the spiritual ascent, acts as a magnet to draw beings to its "palaces ablaze with immaterial matter."

See also

* Arctic cooperation and politics *Arctic Council

The Arctic Council is a high-level intergovernmental forum that addresses issues faced by the Arctic governments and the indigenous people of the Arctic region. At present, eight countries exercise sovereignty over the lands within the Arctic ...

*Arctic ice pack

The Arctic ice pack is the sea ice cover of the Arctic Ocean and its vicinity. The Arctic ice pack undergoes a regular seasonal cycle in which ice melts in spring and summer, reaches a minimum around mid-September, then increases during fall a ...

*Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

*Biome

A biome () is a distinct geographical region with specific climate, vegetation, and animal life. It consists of a biological community that has formed in response to its physical environment and regional climate. In 1935, Tansley added the ...

*Celestial pole

The north and south celestial poles are the two points in the sky where Earth's axis of rotation, indefinitely extended, intersects the celestial sphere. The north and south celestial poles appear permanently directly overhead to observers at ...

* Ecliptic pole

* Inuit Circumpolar Council

* North Pole, Alaska

* North Pole, New York

*Polaris

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinisation of names, Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an ...

*Poles of astronomical bodies

The poles of astronomical bodies are determined based on their axis of rotation in relation to the celestial poles of the celestial sphere. Astronomical bodies include stars, planets, dwarf planets and small Solar System bodies such as comets a ...

*South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

*Willem Barentsz

Willem Barentsz (; – 20 June 1597), anglicized as William Barents or Barentz, was a Dutch Republic, Dutch navigator, cartographer, and Arctic explorer.

Barentsz went on three expeditions to the far north in search for a Northern Sea Route, N ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* * *External links

Arctic Council

The Northern Forum

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1XMZTzELaE Video of the Nuclear Icebreaker Yamal visiting the North Pole in 2001

Polar Discovery: North Pole Observatory Expedition

{{Authority control Extreme points of Earth Northern Canada Navigation Polar regions of the Earth Geography of the Arctic Northern Hemisphere