Noemvriana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Noemvriana'' ( el, Νοεμβριανά, "November Events") of , or the Greek Vespers, was a political dispute which led to an armed confrontation in

Greece emerged victorious after the 1912–1913

Greece emerged victorious after the 1912–1913

On 9 May 1916, the Chief of the General Staff of the Central Powers,

On 9 May 1916, the Chief of the General Staff of the Central Powers,

On 27 August 1916, during a demonstration in Athens, Venizelos explained his disagreements with the king's policies. Venizelos said that the king became a victim of his advisers, whose aims were to destroy the goals of the Goudi revolution. Additionally, Venizelos appealed to the king to pursue a policy of benevolence and true neutrality. Venizelos ended his speech by stating that "if this proposal does not lead to success then there are other means to protect the country from complete catastrophe". The king refused to accept any compromise including meeting with a committee sent by Venizelos.

Two days later, army officers loyal to Venizelos organized a military coup in Thessaloniki and proclaimed the "

On 27 August 1916, during a demonstration in Athens, Venizelos explained his disagreements with the king's policies. Venizelos said that the king became a victim of his advisers, whose aims were to destroy the goals of the Goudi revolution. Additionally, Venizelos appealed to the king to pursue a policy of benevolence and true neutrality. Venizelos ended his speech by stating that "if this proposal does not lead to success then there are other means to protect the country from complete catastrophe". The king refused to accept any compromise including meeting with a committee sent by Venizelos.

Two days later, army officers loyal to Venizelos organized a military coup in Thessaloniki and proclaimed the "

After the creation of the provisional government in Thessaloniki, negotiations between the Allies and king intensified. The Allies wanted further demobilization of the Greek army and the removal of military forces from Thessaly to insure the safety of their troops in Macedonia. The king wanted assurances that the Allies would not officially recognize or support Venizelos' provisional government and guarantees that Greece's integrity and neutrality would be respected.Leon, 1974, p. 422 After several unproductive negotiations, on 23 October the king suddenly agreed to some of the demands required by the Allies including the removal of the Greek army from

After the creation of the provisional government in Thessaloniki, negotiations between the Allies and king intensified. The Allies wanted further demobilization of the Greek army and the removal of military forces from Thessaly to insure the safety of their troops in Macedonia. The king wanted assurances that the Allies would not officially recognize or support Venizelos' provisional government and guarantees that Greece's integrity and neutrality would be respected.Leon, 1974, p. 422 After several unproductive negotiations, on 23 October the king suddenly agreed to some of the demands required by the Allies including the removal of the Greek army from

Diplomacy failed despite continuing pressure applied by the Allies against Athens. On 24 November, du Fournet presented a seven-day ultimatum demanding the immediate surrender of at least ten Greek mountain artillery batteries.Leon, 1974, p. 434 Du Fournet was instructed not to use force to take possession of the batteries. The admiral made a last effort to persuade the king to accept France's demands. He advised the king that he would land an Allied contingent, and occupy certain positions in Athens until all the demands were accepted by Greece. The king said that the citizens of Greece, as well as the army, were against disarmament, and only promised that the Greek forces would not attack the Allies.Leon, 1974, p. 435

Despite the gravity of the situation, both the royalist government and the Allies made no serious effort to reach a diplomatic solution. On 29 November, the royalist government rejected the proposal of the Allies and armed resistance was organized. By 30 November military units and royalist militia (the ''epistratoi'', "reservists") from surrounding areas had been recalled and gathered in and around Athens (in total over 20,000 men) and occupied strategic positions, with orders not to fire unless fired upon. The Allied commanders failed in their assessment of the situation, disregarding Greek national pride and determination, causing them to conclude that the Greeks were bluffing. The Allies thought that in the face of a superior force, Greeks would "bring the cannons on a plater" (surrender); a viewpoint that Du Fournet also shared.

Diplomacy failed despite continuing pressure applied by the Allies against Athens. On 24 November, du Fournet presented a seven-day ultimatum demanding the immediate surrender of at least ten Greek mountain artillery batteries.Leon, 1974, p. 434 Du Fournet was instructed not to use force to take possession of the batteries. The admiral made a last effort to persuade the king to accept France's demands. He advised the king that he would land an Allied contingent, and occupy certain positions in Athens until all the demands were accepted by Greece. The king said that the citizens of Greece, as well as the army, were against disarmament, and only promised that the Greek forces would not attack the Allies.Leon, 1974, p. 435

Despite the gravity of the situation, both the royalist government and the Allies made no serious effort to reach a diplomatic solution. On 29 November, the royalist government rejected the proposal of the Allies and armed resistance was organized. By 30 November military units and royalist militia (the ''epistratoi'', "reservists") from surrounding areas had been recalled and gathered in and around Athens (in total over 20,000 men) and occupied strategic positions, with orders not to fire unless fired upon. The Allied commanders failed in their assessment of the situation, disregarding Greek national pride and determination, causing them to conclude that the Greeks were bluffing. The Allies thought that in the face of a superior force, Greeks would "bring the cannons on a plater" (surrender); a viewpoint that Du Fournet also shared.

On early morning of the Allies landed a 3,000Abbot, 1922, p. 159-strong

On early morning of the Allies landed a 3,000Abbot, 1922, p. 159-strong

File:AnatemaDeVenizelos25121916--constantineigree00hibbuoft.png, "Anathema to traitor Venizelos" by the crowd in Athens, December 1916

File:Anathemavenizelos.jpg, Antivenizelist poster, December 1916

File:Venizelos returns to Athens, 27 June 1917.jpeg, The arrival of Venizelos to Athens, June 1917, after the departure of Constantine

File:Venizelos WWI 1918.jpg, Venizelos reviews a section of the Greek army on the

By the fall of 1918, the Greeks, with over 300,000 soldiers, were the single largest component of the Allied army on the Macedonian front. The Greek army gave the much needed advantage to the Allies that altered the balance between the two sides on the Macedonian front. On 14 September 1918, under the command of French General Franchet d'Esperey, a combined Greek, Serbian, French and British force launched a major offensive against the Bulgarian and

By the fall of 1918, the Greeks, with over 300,000 soldiers, were the single largest component of the Allied army on the Macedonian front. The Greek army gave the much needed advantage to the Allies that altered the balance between the two sides on the Macedonian front. On 14 September 1918, under the command of French General Franchet d'Esperey, a combined Greek, Serbian, French and British force launched a major offensive against the Bulgarian and

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

between the royal

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a ...

ist government of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and the forces of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

over the issue of Greece's neutrality during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

Friction existed between the two sides from the beginning of World War I. The unconditional surrender of the border fortress of Roupel in May 1916 to the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

' forces, mainly composed of Bulgarian troops, was the first event that led to the Noemvriana. The Allies feared the possibility of a secret pact between the Greek royalist government and the Central Powers. Such an alliance would endanger the Allied army in Macedonia bivouacking around Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

since the end of 1915. Intensive diplomatic negotiations between King Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

and Allied diplomats took place throughout the summer. The king wanted Greece to maintain her neutrality, a position that would favor the Central Powers plans in the Balkans while the Allies wanted demobilization of the Hellenic army and the surrender of war materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

equivalent to what was lost at Fort Roupel as a guarantee of Greece's neutrality. By the end of the summer of 1916, the failure of negotiations, along with the Bulgarian Army's advance in eastern Macedonia and the Greek government's orders for the Hellenic army not to offer resistance, led to a military coup by Venizelist

Venizelism ( el, Βενιζελισμός) was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid-1970s.

Main ideas

Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:

*Greek irredentism: ...

military officers in Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

with the support of the Allies. The former Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation move ...

, who from the very beginning supported the Allies, established a provisional government in northern Greece. He began forming an army to liberate areas lost to Bulgaria, but this effectively split Greece into two entities.

The inclusion of the Hellenic army along with Allied forces, as well as the division of Greece, sparked several anti-Allied demonstrations in Athens. In late October, a secret agreement was reached between the king and the Allied diplomats. The pressure from the military advisers forced the king to abandon this agreement. In an attempt to enforce their demands, the Allies landed a small contingent in Athens on . However, it met organized resistance and an armed confrontation took place until a compromise was reached at the end of the day. The day after the Allied contingent evacuated from Athens, a royalist mob began rioting throughout the city, targeting supporters of Venizelos. The rioting continued for three days, and the incident became known as the Noemvriana in Greece, which in the Old Style calendar occurred during the month of November. The incident drove a deep wedge between the Venizelists and the royalists, bringing closer what would become known as the National Schism

The National Schism ( el, Εθνικός Διχασμός, Ethnikós Dichasmós), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos regarding the forei ...

.

Following the Noemvriana, the Allies, determined to remove Constantine I, established a naval blockade to isolate areas which supported the king. After the resignation of the king on 15 June 1917, Greece unified under a new king, Alexander, Constantine I's son, and the leadership of Eleftherios Venizelos. It joined World War I on the side of the Allies. By 1918, the mobilized Hellenic Army provided the numerical superiority the Allies needed on the Macedonian front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers to aid Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, in the autumn of 191 ...

. The Allied army shortly thereafter defeated the Central Powers forces in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, followed by the liberation of Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

and the conclusion of World War I.

Background

Greece emerged victorious after the 1912–1913

Greece emerged victorious after the 1912–1913 Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and def ...

, with her territory almost doubled. The unstable international political climate of the early 20th century placed Greece in a difficult position. The ownership of the Greek occupied eastern Aegean islands was contested by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

which claimed them as their own. In the north, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, defeated in the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies ...

, was engineering revanchist strategies against Greece and Serbia. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

Fr ...

in Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

precipitated Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

's declaration of war against Serbia. This caused Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Austria-Hungary, and countries allied with Serbia (the Triple Entente) to declare war on each other, starting World War I.

Greece, like Bulgaria, initially maintained neutrality during the conflict. The Greek leadership was divided between the Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, who supported Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

on the side of the Allies and King Constantine who was educated in Germany and married to the Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

's sister. The king admired Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n militarism and was anticipating a quick German victory. The king wanted Greece to remain neutral in the conflict, a strategy favorable to Germany and the Central Powers.

In early 1915, Britain offered Greece "territorial concessions in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

" if it would participate in the upcoming Gallipoli Campaign. Venizelos supported this idea, while the king and his military advisers opposed it. Dismayed at the king's opposition, the prime minister resigned on 21 February 1915. A few months later, Venizelos' Liberal Party won the May elections, and formed a new government. When Bulgaria mobilized against Serbia in September 1915, Venizelos ordered a Greek counter-mobilization and asked the Anglo-French army to defend Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

and aid Serbia. The Allies, led by General Maurice Sarrail

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail (6 April 1856 – 23 March 1929) was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated t ...

, began landing on 22 September 1915 and entrenched around the city. The Greek parliament gave Venizelos a vote of confidence to help Serbia, yet the king unconstitutionally dismissed the prime minister along with the parliament. This unlawful order escalated the animosity between the king and Venizelos as well as their loyal followers. The Liberals boycotted the December elections.

Causes

Surrender of Fort Rupel

On 9 May 1916, the Chief of the General Staff of the Central Powers,

On 9 May 1916, the Chief of the General Staff of the Central Powers, Erich von Falkenhayn

General Erich Georg Sebastian Anton von Falkenhayn (11 September 1861 – 8 April 1922) was the second Chief of the German General Staff of the First World War from September 1914 until 29 August 1916. He was removed on 29 August 1916 after ...

informed Athens of the imminent advance of German-Bulgarian forces. In reply, Athens minimized the importance of General Sarrail's movements and requested Falkenhayn to change his strategy. On 23 May, Falkenhayn guaranteed that the territorial integrity of Greece and the rights of its citizens would be respected. On 26 May, despite an official protest by the Greek government, 25,000 Bulgarian soldiers led by German cavalry invaded Greece. The Greek forces at Fort Rupel surrendered. The German Supreme Command was concerned about Allied General Sarrail's movements and Falkenhayn was ordered to occupy strategic positions inside Greek territory, specifically Fort Rupel. Despite the assurances of Falkenhayn, Bulgarian soldiers immediately began to forcibly centralize the Greek population into large cities, namely Serres, Drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has b ...

and Kavala

Kavala ( el, Καβάλα, ''Kavála'' ) is a city in northern Greece, the principal seaport of eastern Macedonia and the capital of Kavala regional unit.

It is situated on the Bay of Kavala, across from the island of Thasos and on the Egnat ...

. German attempts to restrain Bulgarian territorial ambitions were partially successful, yet on 4 September, Kavala was occupied by the Bulgarian Army.

Reactions of Venizelos and the Allies

The surrender of Fort Rupel caused the Allies to believe that the German-Bulgarian advance was a result of a secret agreement between Athens and the Central Powers, as they were assured that no Bulgarian force would invade Greek territory. The Allies saw this as a violation of Greek neutrality and a disturbance in the balance of power in the Balkans. The Allied press, especially inFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, demanded swift military action against Greece to protect the Allied forces in Macedonia.Leon, 1974, p. 361 For Venizelos and his supporters, the surrender of Fort Rupel signaled the loss of Greek Macedonia. On 29 May, Venizelos proposed to Sir Francis Elliot (senior British diplomat in Athens) and Jean Guillemin (senior French diplomat in Athens) that he and General Panagiotis Danglis

Panagiotis Danglis ( el, Παναγιώτης Δαγκλής; – 9 March 1924) was a Greek Army general and politician. He is particularly notable for his invention of the Schneider-Danglis mountain gun, his service as chief of staff in the Balk ...

should establish a provisional government in Thessaloniki to mobilize the Greek army to repel the Bulgarians. Venizelos pledged that the army would not move against the king and the royal family. According to Elliot's report, Venizelos hoped that the "success of his action and pressure of the public opinion might at the last moment convert His Majesty". The proposal had French support. However it met with strong opposition from Britain, forcing Venizelos to abandon the plan.

On 9 June the Allies held a conference in London to examine the reasons behind the quick surrender of Fort Rupel and favored a complete demobilization of the Greek army and navy.Leon, 1974, p. 368 King Constantine anticipated the results of the conference and ordered a partial demobilization on 8 June. The tension between the royal government and the Allies continued since 'anti-Allied activities' in Athens were ignored by the Greek Government. On 12–13 June, a mob destroyed Venizelist newspapers: ''Nea Ellas'', ''Patris'', '' Ethnos'', and ''Estia

''Estia'' ( el, Ἑστία, , hearth) is a Greek national daily broadsheet newspaper published in Athens, Greece. It was founded in 1876 as a literary magazine and then in 1894 has been transformed into a newspaper, making it Greece's oldest dai ...

''. The mob proceeded to the British Embassy as police idly stood by without interfering. This incident gave France the political ammunition to persuade Britain that more extreme measures were needed. On 17 June, the London conference decided "that it was absolutely necessary to do something to bring the king of Greece and his Government to their senses".

Military coup of Thessaloniki

On 27 August 1916, during a demonstration in Athens, Venizelos explained his disagreements with the king's policies. Venizelos said that the king became a victim of his advisers, whose aims were to destroy the goals of the Goudi revolution. Additionally, Venizelos appealed to the king to pursue a policy of benevolence and true neutrality. Venizelos ended his speech by stating that "if this proposal does not lead to success then there are other means to protect the country from complete catastrophe". The king refused to accept any compromise including meeting with a committee sent by Venizelos.

Two days later, army officers loyal to Venizelos organized a military coup in Thessaloniki and proclaimed the "

On 27 August 1916, during a demonstration in Athens, Venizelos explained his disagreements with the king's policies. Venizelos said that the king became a victim of his advisers, whose aims were to destroy the goals of the Goudi revolution. Additionally, Venizelos appealed to the king to pursue a policy of benevolence and true neutrality. Venizelos ended his speech by stating that "if this proposal does not lead to success then there are other means to protect the country from complete catastrophe". The king refused to accept any compromise including meeting with a committee sent by Venizelos.

Two days later, army officers loyal to Venizelos organized a military coup in Thessaloniki and proclaimed the "Provisional Government of National Defence

The Provisional Government of National Defence (), also known as the State of Thessaloniki (Κράτος της Θεσσαλονίκης), was a parallel administration, set up in the city of Thessaloniki by former Prime Minister Eleftherios Ven ...

". Despite the support of the army, the provisional government was not officially recognized by Venizelos nor the Allied powers. Venizelos criticized this course of action, noting that without the support of the Allied army, the movement would fail immediately. This further polarized the population between the royalists (also known as ''anti-Venizelists''), and Venizelist

Venizelism ( el, Βενιζελισμός) was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid-1970s.

Main ideas

Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:

*Greek irredentism: ...

s. The newly founded separate "provisional state" included Northern Greece, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and the Aegean Islands.Clogg, 2002, p. 87 The "New Lands", won during the Balkan Wars, broadly supported Venizelos, while the "Old Greece" was mostly pro-royalist. Venizelos, Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis and General Panagiotis Danglis

Panagiotis Danglis ( el, Παναγιώτης Δαγκλής; – 9 March 1924) was a Greek Army general and politician. He is particularly notable for his invention of the Schneider-Danglis mountain gun, his service as chief of staff in the Balk ...

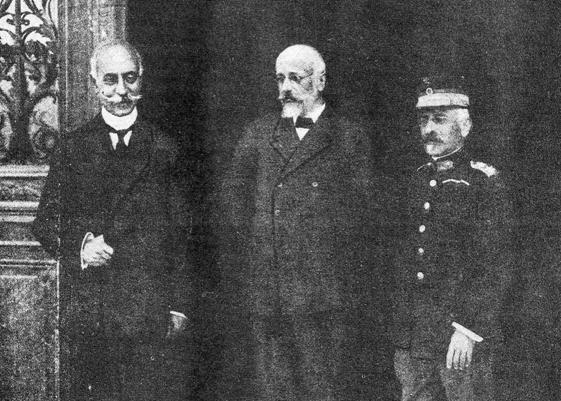

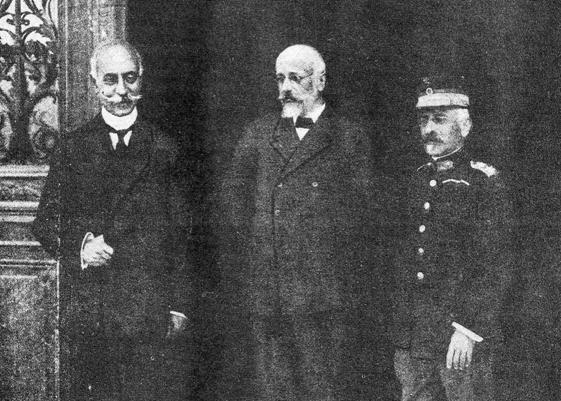

formed a triumvirate provisional government and on 9 October moved to Thessaloniki to assume command of the National Defense. They directed Greek participation in the Allied war effort in direct conflict with the royal wishes in Athens.Kitromilides, 2008, p. 124 According to a British diplomat:

From the very beginnings, Venizelos continued his appeals to the king to join forces to jointly liberate Macedonia.Leon, 1974, p. 417 Venizelos wrote:

Venizelos' moderation did not convince many citizens, even among his own followers. It was only after the end of 1916 and the "Noemvriana" that he pushed for a radical solution to end the stalemate.

Constantine–Bénazet agreement

After the creation of the provisional government in Thessaloniki, negotiations between the Allies and king intensified. The Allies wanted further demobilization of the Greek army and the removal of military forces from Thessaly to insure the safety of their troops in Macedonia. The king wanted assurances that the Allies would not officially recognize or support Venizelos' provisional government and guarantees that Greece's integrity and neutrality would be respected.Leon, 1974, p. 422 After several unproductive negotiations, on 23 October the king suddenly agreed to some of the demands required by the Allies including the removal of the Greek army from

After the creation of the provisional government in Thessaloniki, negotiations between the Allies and king intensified. The Allies wanted further demobilization of the Greek army and the removal of military forces from Thessaly to insure the safety of their troops in Macedonia. The king wanted assurances that the Allies would not officially recognize or support Venizelos' provisional government and guarantees that Greece's integrity and neutrality would be respected.Leon, 1974, p. 422 After several unproductive negotiations, on 23 October the king suddenly agreed to some of the demands required by the Allies including the removal of the Greek army from Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

. The king also volunteered war materiel and the Greek navy to assist them. In exchange, the king requested French Deputy Paul Bénazet to keep this agreement secret from the Central Powers.

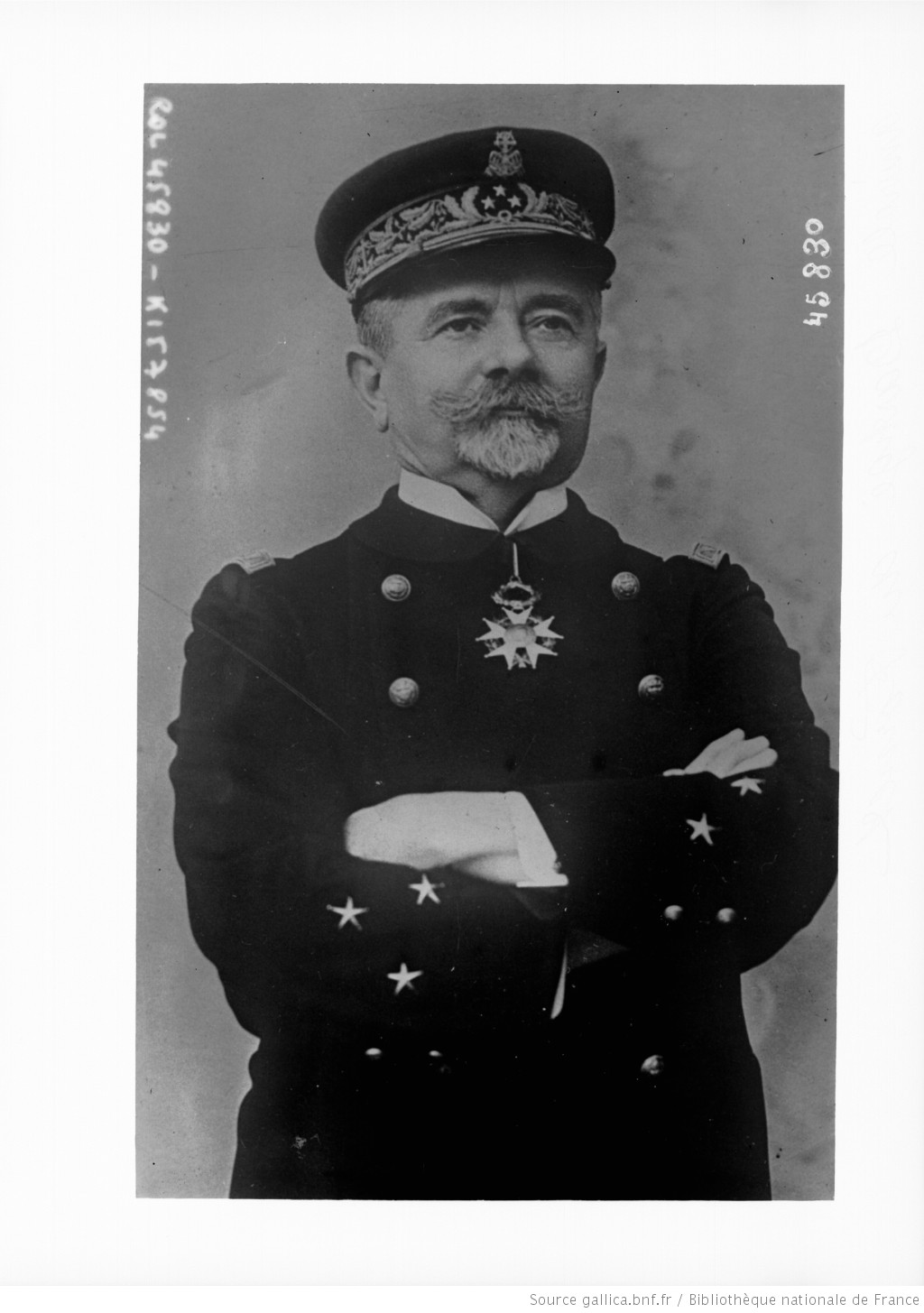

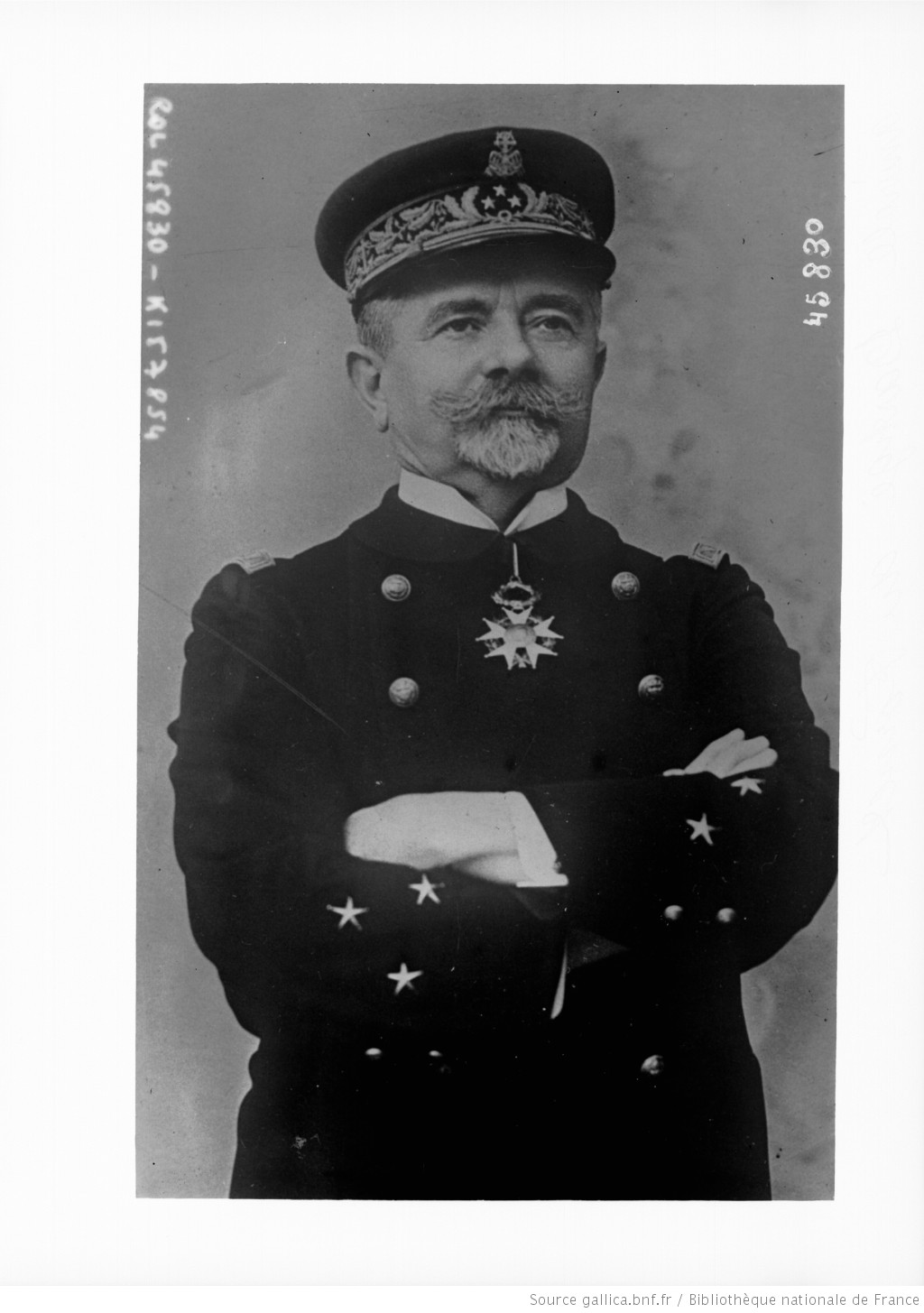

On 3 November, Vice-admiral du Fournet, commander-in-chief of the allied Mediterrean fleet, used the sinking of two Greek merchant ships by a German submarine, as well as the secret agreement, to demand the surrender of the docked Greek war ships and took command of the Salamis naval arsenal. The Greek government yielded, and on 7 November,Leon, 1974, p. 428 the partial disarmament of Greek warships began. The Allies towed away 30 lighter craft. Three weeks later the French took over the Salamis naval base completely, and began using Greek ships operated by French crews.

The Constantine–Bénazet agreement was short-lived due to Venizelos' military plans as well as pressure exerted by the military in Athens, led by the king, regarding the forced Greek disarmament.Leon, 1974, p. 424 The army of the Defence confronted against the royalist army at Katerini

Katerini ( el, Κατερίνη, ''Kateríni'', ) is a city and municipality in northern Greece, the capital city of Pieria regional unit in Central Macedonia, Greece. It lies on the Pierian plain, between Mt. Olympus and the Thermaikos Gulf, ...

(and by January 1917 had taken the control of Thessaly). This action at Katerini met with some disapproval among the Allied circles and among his own associates in Athens. Answering these criticisms Venizelos wrote to A. Diamandidis:

The Venizelist advance was not an attempt to undermine the king's pact with Bénazet, since it had been planned long before that. The failure of the secret agreement was caused by subversive activities within segments of the royalist government in Athens to paralyze and disrupt the Thessaloniki provisional government.

Last diplomatic efforts before the events

The seizure of Greek ships by the Allies, the Katerini incident and the Franco-British violations of Greece's territorial integrity offended the national honor of a segment of "Old Greece" and increased the king's popularity. The king refused to honor his secret agreement with Bénazet and soldiers who requested to fight against the Bulgarian occupation were charged with "desertion to the rebels". A growing movement amongst the low rank officers within the army, led by Ioannis Metaxas and Sofoklis Dousmanis, were determined to oppose disarmament and any assistance to the Allies. Diplomacy failed despite continuing pressure applied by the Allies against Athens. On 24 November, du Fournet presented a seven-day ultimatum demanding the immediate surrender of at least ten Greek mountain artillery batteries.Leon, 1974, p. 434 Du Fournet was instructed not to use force to take possession of the batteries. The admiral made a last effort to persuade the king to accept France's demands. He advised the king that he would land an Allied contingent, and occupy certain positions in Athens until all the demands were accepted by Greece. The king said that the citizens of Greece, as well as the army, were against disarmament, and only promised that the Greek forces would not attack the Allies.Leon, 1974, p. 435

Despite the gravity of the situation, both the royalist government and the Allies made no serious effort to reach a diplomatic solution. On 29 November, the royalist government rejected the proposal of the Allies and armed resistance was organized. By 30 November military units and royalist militia (the ''epistratoi'', "reservists") from surrounding areas had been recalled and gathered in and around Athens (in total over 20,000 men) and occupied strategic positions, with orders not to fire unless fired upon. The Allied commanders failed in their assessment of the situation, disregarding Greek national pride and determination, causing them to conclude that the Greeks were bluffing. The Allies thought that in the face of a superior force, Greeks would "bring the cannons on a plater" (surrender); a viewpoint that Du Fournet also shared.

Diplomacy failed despite continuing pressure applied by the Allies against Athens. On 24 November, du Fournet presented a seven-day ultimatum demanding the immediate surrender of at least ten Greek mountain artillery batteries.Leon, 1974, p. 434 Du Fournet was instructed not to use force to take possession of the batteries. The admiral made a last effort to persuade the king to accept France's demands. He advised the king that he would land an Allied contingent, and occupy certain positions in Athens until all the demands were accepted by Greece. The king said that the citizens of Greece, as well as the army, were against disarmament, and only promised that the Greek forces would not attack the Allies.Leon, 1974, p. 435

Despite the gravity of the situation, both the royalist government and the Allies made no serious effort to reach a diplomatic solution. On 29 November, the royalist government rejected the proposal of the Allies and armed resistance was organized. By 30 November military units and royalist militia (the ''epistratoi'', "reservists") from surrounding areas had been recalled and gathered in and around Athens (in total over 20,000 men) and occupied strategic positions, with orders not to fire unless fired upon. The Allied commanders failed in their assessment of the situation, disregarding Greek national pride and determination, causing them to conclude that the Greeks were bluffing. The Allies thought that in the face of a superior force, Greeks would "bring the cannons on a plater" (surrender); a viewpoint that Du Fournet also shared.

The Battle of Athens, 1916

On early morning of the Allies landed a 3,000Abbot, 1922, p. 159-strong

On early morning of the Allies landed a 3,000Abbot, 1922, p. 159-strong marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military ...

force in Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saro ...

, and headed towards Athens.Kitromilides, 2006, p. 125Markezinis, 1968, p. 175 When the Allied troops reached their designated positions, they found them already occupied by Greek troops. For more than two hours both sides stood facing each other. Some time in the morning, an unknown origin rifle shot was fired and the battle of Athens began. Each side blamed the other for firing first. Once the battle spread throughout the city, the king requested a ceasefire proposing a solution and reach a compromise. Du Fournet, with a small contingent of troops was unprepared to encounter organized Greek resistance, and was already short of supplies, so readily accepted the king's compromise. However, before an agreement was finalized, the battle resumed. The Greek battery from Arditos Hill fired a number of rounds at the entrance of Zappeion

The Zappeion ( el, Ζάππειον Μέγαρο, Záppeion Mégaro, ) is a large, palatial building next to the National Gardens of Athens in the heart of Athens, Greece. It is generally used for meetings and ceremonies, both official and priva ...

where the French admiral had established his headquarters. The Allied squadron from Phaliron responded by bombarding sections of the city, mostly around the Stadium

A stadium ( : stadiums or stadia) is a place or venue for (mostly) outdoor sports, concerts, or other events and consists of a field or stage either partly or completely surrounded by a tiered structure designed to allow spectators to stand o ...

and near the Palace. Discussions soon were resumed and a final compromise was reached. The king compromised to surrender just six artillery batteries camouflaged in the mountains instead of the ten that the Allied Admiral demanded.Leon, 1974, p. 436Abbot, 1922, p. 160 By late afternoon the battle was finished. The Allies had suffered 194 casualties, dead and wounded, and the Greeks lost 82, not counting civilians.Clogg, 2002, p. 89 By early morning of 2 December, all Allied forces had been evacuated.

The role of the Venizelists during the battle has been intensely contested by witnesses and historians. Vice admiral Louis Dartige du Fournet wrote that Venizelists supported the Allies and attacked passing Greek royalist army units. Venizelists participation was allegedly so extensive, that lead Admiral du Fourne wrote in his report that he had been involved in a civil war. The Venizelists continued fighting after the evacuation of the Allied marines until the next day, when they capitulated. The royalists claimed that large caches of weapons and ammunition were found in their strongholds packed in French military containers. Venizelists were led to prison surrounded by a furious mob and supposedly only the royal army escorts saved them from being murdered by the angry citizens.Abbot, 1922, p. 161 Other historians deny that the Venizelists collaborated with the Allied forces: Pavlos Karolidis

Pavlos Karolidis or Karolides ( el, Παύλος Καρολίδης, 1849 – 26 July 1930) was one of the most eminent Greek historians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Life

Karolidis was born in 1849 in the village of Androniki ( ...

, a contemporary royalist historian, argues that no Venizelist attacked their fellow citizens and the only weapons found during the raids on prominent Venizelists' houses were knives.Karolidis, 1925, VI, 248–249

The following days

The authorities, with the pretext of the events, claimed that the Venelizelists had staged an insurrection with the support of Allied troops and proceeded with the help of the Reservists to extensive arrests and reprisals against the city's Venizelists. The entire operation was led by two generals of the army; troops of the military district of Athens took orders from General K. Kallaris and the soldiers of the active defense were commanded by General A. Papoulas (later commander-in-chief of the Asia Minor expedition). The terror and destruction that followed soon went out of hand, making even the respectable conservative newspaper Politiki Epitheorisis ( el, Πολιτική Επιθεώρηση, Political Review) that at the beginning urged Greek "justice" to "smite mercifully the atrocious conspiracy" and to purge all followers of the "archconspirator of Salonika enizelos, in the end to urge "prudence".Leon, 1974, pp. 436–7 During the following three days houses and shops of Venizelists were ransacked and 35 people were murdered. Chester says that most of those who were murdered were refugees from Asia Minor. Many hundreds were imprisoned and kept in solitary confinement. Karolidis characterizes the imprisonment of certain prominent Venizelists, such asEmmanuel Benakis

Emmanouil Benakis ( el, Εμμανουήλ Μπενάκης; 1843 in Ermoupoli, Syros – June 20, 1929 in Kifisia) was a Greek merchant and politician, considered a national benefactor of Greece.

After studying in England, Benakis emigrat ...

(mayor of Athens), as a disgrace. Some authors argue that Benakis was not only arrested and imprisoned but also disrespected and ill-treated. Seligman describes that they were only released 45 days later after a strong demand contained within the Entente ultimatum, which was accepted on 16 January. Opposing reports also exist, e.g. Abbot asserts that during the evacuation of the Allied forces, many "criminals" and "collaborators" on the payrolls of different Allied spy agencies slipped out of Athens at night after allegedly "terrorizing the city for nearly a year". Due to his failure Vice-admiral Dartige du Fournet was relieved of his command.

Aftermath

In Greece, this incident became known as Noemvriana (November events), using the Old Style calendar, and marked the culmination of the National Schism.Political situation in Greece and Europe

On , Britain and France officially recognized Venizelos government as the only lawful government of Greece, effectively splitting the country. On , Venizelos' government officially declared war on the Central Powers. Mainwhile in Athens Constantine praised his generals. There were also in circulation various pro-royalist and religious brochures calling Venizelos "traitor" and "Senegalese goat". A royal warrant for the arrest of Venizelos was issued and theArchbishop of Athens

The Archbishopric of Athens ( el, Ιερά Αρχιεπισκοπή Αθηνών) is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. Its ...

, pressured by the royal house, anathematised the prime minister (in a special ceremony with the crowd throwing stones to an effigy of Venizelos).

In France, the premiership of Aristide Briand, a leading proponent of engaging with Constantine to bring about a reconciliation of the two Greek administrations, was threatened by the events in Athens, leading to the reorganization of the French government. In Britain, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

and foreign minister Sir Edward Grey resigned and were replaced by Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

and Arthur Balfour. The change in the British leadership proved to be particularly important for Greece, since Lloyd George was a known Hellenophile

Philhellenism ("the love of Greek culture") was an intellectual movement prominent mostly at the turn of the 19th century. It contributed to the sentiments that led Europeans such as Lord Byron and Charles Nicolas Fabvier to advocate for Greek ...

, an admirer of Venizelos and dedicated to resolving the Eastern Question.Clogg, 2002, p. 89

The fall of the Romanovs in Russia (who refused the French proposals for Constantine's removal from the throne), caused France and Great Britain to take more drastic measures against King Constantine. In June they decided to invoke their obligation as "protecting powers" and demanded the king's resignation. Charles Jonnart

Charles Célestin Auguste Jonnart (27 December 1857 – 30 December 1927) was a French politician.

Early years

Born into a bourgeois family in Fléchin, Pas-de-Calais, Charles Jonnart was educated at Saint-Omer, then in Paris. Interested in the ...

said to Constantine: "The Germans burned my native town, Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department, which forms part of the region of Hauts-de-France; before the reorganization of 2014 it was in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The historic centre of ...

. I will not hesitate to burn Athens". Constantine accepted and on 15 June 1917 went into exile. His son Alexander, who was considered to have Allies sympathies, became the new King of Greece instead of Constantine's elder son and crown prince, George.Land of InvasionTIME

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

, 4 November 1940 The king's exile was followed by the deportation of many prominent royalist officers and politicians considered pro-Germans, such as Ioannis Metaxas and Dimitrios Gounaris, to France and Italy.

The course of events paved the way for Venizelos to return to Athens on 29 May 1917. Greece, now unified, officially joined the war on the side of the Allies. The entire Greek army was mobilized (though tensions remained inside the army between supporters of the Constantine and supporters of Venizelos) and began to participate in military operations against the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

on the Macedonian front.

Macedonian front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers to aid Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, in the autumn of 191 ...

in 1918. He is accompanied by Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis (left) and General Maurice Sarrail

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail (6 April 1856 – 23 March 1929) was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated t ...

(right).

The Macedonian front

By the fall of 1918, the Greeks, with over 300,000 soldiers, were the single largest component of the Allied army on the Macedonian front. The Greek army gave the much needed advantage to the Allies that altered the balance between the two sides on the Macedonian front. On 14 September 1918, under the command of French General Franchet d'Esperey, a combined Greek, Serbian, French and British force launched a major offensive against the Bulgarian and

By the fall of 1918, the Greeks, with over 300,000 soldiers, were the single largest component of the Allied army on the Macedonian front. The Greek army gave the much needed advantage to the Allies that altered the balance between the two sides on the Macedonian front. On 14 September 1918, under the command of French General Franchet d'Esperey, a combined Greek, Serbian, French and British force launched a major offensive against the Bulgarian and German army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

. After the first serious battle (see battle of Skra) the Bulgarian Army gave up its defensive positions and began retreating towards their country. On 29 September, the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

with Bulgaria was signed by the Allied command. The Allied army pushed north and defeated the remaining German and Austrian forces. By October 1918 the Allied armies had recaptured all of Serbia and were preparing to invade Hungary. The offensive was halted because the Hungarian leadership offered to surrender in November 1918, marking the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire. This ended the First World War since Germany lacked forces to stop the Allies from invading Germany from the south. The participation of the Greek army at the Macedonian front was one of the decisive event of the war, earning Greece a seat at the Paris Peace Conference under Venizelos.Chester, 1921, pp. 312–3

See also

* The Great WarNotes

Footnotes

References

; Books * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ; Journals *External links

* {{Greece during World War I 1916 in Greece 1916 riots Constantine I of Greece Ioannis Metaxas Macedonian front Military history of Athens Military history of Greece during World War I Modern history of Athens Political riots Riots and civil disorder in Greece