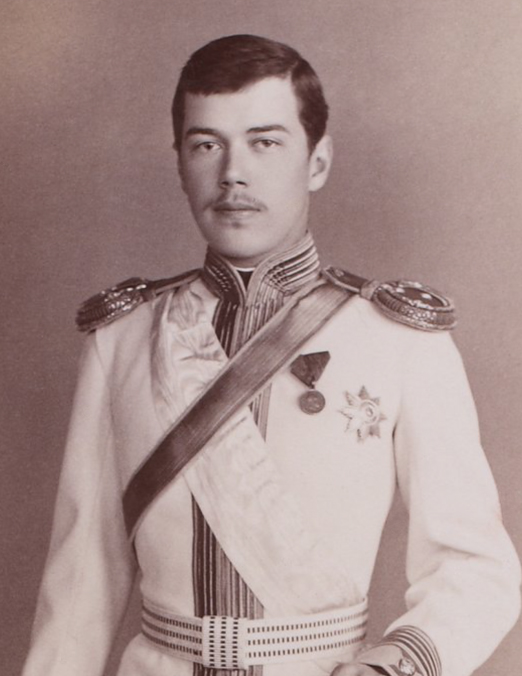

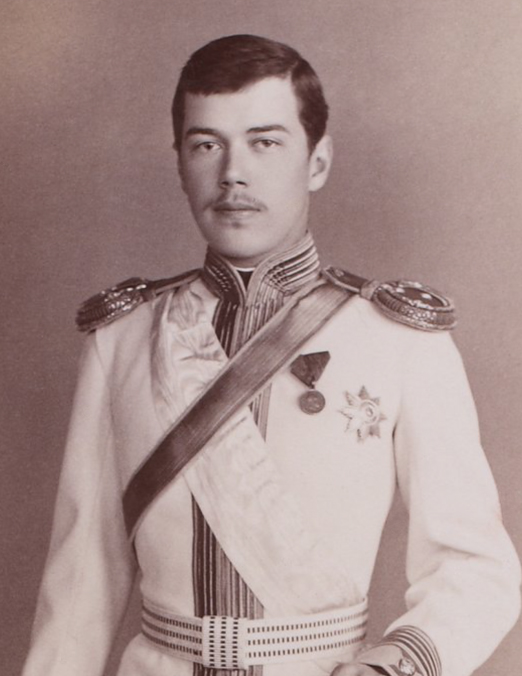

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in

pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the

Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last

Emperor of Russia,

King of Congress Poland and

Grand Duke of Finland, ruling from 1 November 1894 until

his abdication on 15 March 1917. During his reign, Nicholas gave support to the economic and political reforms promoted by his prime ministers,

Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

and

Pyotr Stolypin. He advocated modernization based on foreign loans and close ties with France, but resisted giving the new parliament (the

Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

) major roles.

Ultimately, progress was undermined by Nicholas's commitment to

autocratic rule,

strong aristocratic opposition and defeats sustained by the Russian military in the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

and

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

By March 1917, public support for Nicholas had collapsed and he was forced to abdicate the throne, thereby ending the

Romanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

's 304-year rule of Russia (1613–1917).

Nicholas signed the

Anglo-Russian Convention

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (russian: Англо-Русская Конвенция 1907 г., translit=Anglo-Russkaya Konventsiya 1907 g.), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ...

of 1907, which was designed to counter

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

's attempts to gain influence in the Middle East; it ended the

Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

of confrontation between Russia and the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. He aimed to strengthen the

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (french: Alliance Franco-Russe, russian: Франко-Русский Альянс, translit=Franko-Russkiy Al'yans), or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Russo-Français'', Русско-Французско� ...

and proposed the unsuccessful

Hague Convention of 1899 to promote disarmament and solve international disputes peacefully. Domestically, he was criticised for his government's repression of political opponents and his perceived fault or inaction during the

Khodynka Tragedy

The Khodynka Tragedy ( rus, Ходынская трагедия) was a crowd crush that occurred on , on Khodynka Field in Moscow, Russia. The crush happened during the festivities after the coronation of the last Emperor of Russia, Nicholas I ...

,

anti-Jewish pogroms,

Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

and the violent suppression of the

1905 Russian Revolution. His popularity was further damaged by the Russo-Japanese War, which saw the

Russian Baltic Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Baltic fleet.svg

, image_size = 150

, caption = Baltic Fleet Great ensign

, dates = 18 May 1703 – present

, country =

, allegiance = (1703–1721) (1721–1917) (1917–1922) (1922–1991)(1991–present)

...

annihilated at the

Battle of Tsushima, together with the loss of Russian influence over Manchuria and Korea and the

Japanese annexation of the south of Sakhalin Island.

During the

July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, which led to the outbreak of World War I (1914–1918). The crisis began on 28 June 1914, when Gavrilo Pri ...

, Nicholas supported

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

and approved the mobilization of the

Russian Army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �ВSukhoputnyye voyska V}), also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Force ...

on 30 July 1914. In response, Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August 1914 and its ally France on 3 August 1914, starting the

Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, later known as the First World War. The severe military losses led to a collapse of morale at the front and at home; a

general strike and a mutiny of the garrison in

Petrograd sparked the

February Revolution and the disintegration of the monarchy's authority. After abdicating for himself and his son, Nicholas and his family were imprisoned by the

Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

and exiled to Siberia. After the

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

took power in the

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, the family was held in

Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg ( ; rus, Екатеринбург, p=jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnˈburk), alternatively romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( rus, Свердло́вск, , svʲɪrˈdlofsk, 1924–1991), is a city and the administra ...

, where

they were executed on 17 July 1918.

In 1981, Nicholas, his wife, and their children were recognized as martyrs by the

Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, based in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. Their gravesite was discovered in 1979, but this was not acknowledged until 1989. After the fall of the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, the remains of the imperial family were exhumed, identified by DNA analysis, and re-interred with an elaborate state and church ceremony in St. Petersburg on 17 July 1998, exactly 80 years after their deaths. They were

canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

in 2000 by the Russian Orthodox Church as

passion bearer

In Eastern Christianity, a passion bearer ( rus, страстотéрпец, r=strastoterpets, p=strəstɐˈtʲɛrpʲɪts) is one of the various customary titles for saints used in commemoration at divine services when honouring their feast on ...

s. In the years following his death, Nicholas was reviled by

Soviet historians

This list of Russian historians includes the famous historians, as well as archaeologists, paleographers, genealogists and other representatives of auxiliary historical disciplines from the Russian Federation, the Soviet Union, the Russian Empire ...

and

state propaganda as a "callous tyrant" who "persecuted his own people while sending countless soldiers to their deaths in pointless conflicts".

Despite being viewed more positively in recent years, the majority view among historians is that Nicholas was a well-intentioned yet poor ruler who proved incapable of handling the challenges facing his nation.

[Ferro, Marc (1995) ''Nicholas II: Last of the Tsars''. New York: Oxford University Press, , p. 2]

Early life

Birth and family background

Grand Duke Nicholas was born on 1868, in the

Alexander Palace in

Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

south of

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, during the reign of his grandfather

Emperor Alexander II. He was the eldest child of then-

Tsesarevich

Tsesarevich (russian: Цесаревич, ) was the title of the heir apparent or presumptive in the Russian Empire. It either preceded or replaced the given name and patronymic.

Usage

It is often confused with " tsarevich", which is a di ...

Alexander Alexandrovich and his wife,

Tsesarevna Maria Feodorovna (née Princess Dagmar of Denmark). Grand Duke Nicholas' father was

heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

n throne as the second but eldest surviving son of Emperor Alexander II of Russia. His paternal grandparents were Emperor Alexander II and

Empress Maria Alexandrovna (née Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine). His maternal grandparents were

King Christian IX

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein ...

and

Queen Louise of Denmark.

The young grand duke was christened in the

Chapel of the Resurrection

The Chapel of the Resurrection is the centerpiece structure on the campus of Valparaiso University in Valparaiso, Indiana.

Primarily used to facilitate many Lutheranism, Lutheran campus worship services, the Chapel of the Resurrection also serve ...

of the

Catherine Palace

The Catherine Palace (russian: Екатерининский дворец, ) is a Rococo palace in Tsarskoye Selo (Pushkin), 30 km south of St. Petersburg, Russia. It was the summer residence of the Russian tsars. The Palace is part of the ...

at

Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

on 1868 by the

confessor

Confessor is a title used within Christianity in several ways.

Confessor of the Faith

Its oldest use is to indicate a saint who has suffered persecution and torture for the faith but not to the point of death.[protopresbyter

A ''protoiereus'' (from grc, πρωτοϊερεύς, "first priest", Modern Greek: πρωθιερέας) or protopriest in the Eastern Orthodox Church is a priest usually coordinating the activity of other subordinate priests in a bigger church. T ...]

Vasily Borisovich Bazhanov. His godparents were Emperor Alexander II (his paternal grandfather),

Queen Louise of Denmark (his maternal grandmother),

Crown Prince Frederick of Denmark (his maternal uncle), and

Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (his great great-aunt). The boy received the traditional

Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

name ''

Nicholas'' and was named in memory of his father’s older brother and mother’s first

fiancé

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

,

Tsesarevich

Tsesarevich (russian: Цесаревич, ) was the title of the heir apparent or presumptive in the Russian Empire. It either preceded or replaced the given name and patronymic.

Usage

It is often confused with " tsarevich", which is a di ...

Nicholas Alexandrovich of Russia, who had died young in 1865. Informally, he was known as "Nikki" throughout his life.

Nicholas was of primarily German and

Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

descent, his last ethnically Russian ancestor being

Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna of Russia

Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna of Russia (russian: А́нна Петро́вна; 27 January 1708 – 4 March 1728) was the eldest daughter of Emperor Peter I of Russia and his wife Empress Catherine I. Her younger sister, Empress Elizabeth, ...

(1708–1728), daughter of

Peter the Great. On the other hand, Nicholas was related to several monarchs in Europe. His mother's siblings included Kings

Frederick VIII of Denmark and

George I of Greece

George I ( Greek: Γεώργιος Α΄, ''Geórgios I''; 24 December 1845 – 18 March 1913) was King of Greece from 30 March 1863 until his assassination in 1913.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen, and seemed destined for ...

, as well as the United Kingdom's

Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 t ...

(consort of

King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

). Nicholas, his wife Alexandra, and

German emperor Wilhelm II were all first cousins of

King George V of the United Kingdom

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

. Nicholas was also a first cousin of both

King Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick VI ...

and

Queen Maud of Norway

Maud of Wales (Maud Charlotte Mary Victoria; 26 November 1869 – 20 November 1938) was the Queen of Norway as the wife of King Haakon VII. The youngest daughter of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom, she was known as P ...

, as well as

King Christian X of Denmark

Christian X ( da, Christian Carl Frederik Albert Alexander Vilhelm; 26 September 1870 – 20 April 1947) was King of Denmark from 1912 to his death in 1947, and the only King of Iceland as Kristján X, in the form of a personal union rathe ...

and

King Constantine I of Greece. Nicholas and Wilhelm II were in turn second cousins once-removed, as each descended from

King Frederick William III of Prussia

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

, as well as third cousins, as they were both great-great-grandsons of

Tsar Paul I of Russia

Paul I (russian: Па́вел I Петро́вич ; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1796 until his assassination. Officially, he was the only son of Peter III and Catherine the Great, although Catherine hinted that he was fathered by her l ...

. In addition to being second cousins through descent from

Louis II, Grand Duke of Hesse

Louis II (26 December 1777 – 16 June 1848) was Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine from 6 April 1830 until 5 March 1848, resigning during the German Revolution of 1848. He was the son of Louis I, Grand Duke of Hesse, and Princess Louise of ...

and his wife

Princess Wilhelmine of Baden

Princess Wilhelmine Louise of Baden (21 September 1788 – 27 January 1836), was by birth a Princess of Baden from the House of Zähringen and by marriage Grand Duchess consort of Hesse and by Rhine. Her descendants include the last emperor of Ru ...

, Nicholas and Alexandra were also third cousins once-removed, as they were both descendants of

King Frederick William II of Prussia.

Tsar Nicholas II was the first cousin once-removed of

Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich. To distinguish between them, the Grand Duke was often known within the imperial family as "Nikolasha" and "Nicholas the Tall", while the Tsar was "Nicholas the Short".

Childhood

Grand Duke Nicholas was to have five younger siblings:

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

(1869–1870),

George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

(1871–1899),

Xenia (1875–1960),

Michael (1878–1918) and

Olga (1882–1960). Nicholas often referred to his father nostalgically in letters after Alexander's death in 1894. He was also very close to his mother, as revealed in their published letters to each other.

In his childhood, Nicholas, his parents and siblings made annual visits to the Danish royal palaces of

Fredensborg

Fredensborg () is a railway town located in Fredensborg Municipality, North Zealand, some 30 kilometres north of Copenhagen, Denmark. It is most known for Fredensborg Palace, one of the official residences of the Danish Royal Family. As of 1 Janu ...

and

Bernstorff

Bernstorff is an old and distinguished German-Danish noble family of Mecklenburgian origin. Members of the family held the title of Count/Countess, granted to them on 14.12.1767 by King Christian VII of Denmark.

Notable members

* Andreas Got ...

to visit his grandparents, the king and queen. The visits also served as family reunions, as his mother's siblings would also come from the United Kingdom, Germany and Greece with their respective families. It was there in 1883, that he had a flirtation with one of his British first cousins,

Princess Victoria. In 1873, Nicholas also accompanied his parents and younger brother, two-year-old George, on a two-month, semi-official visit to the United Kingdom. In London, Nicholas and his family stayed at

Marlborough House

Marlborough House, a Grade I listed mansion in St James's, City of Westminster, London, is the headquarters of the Commonwealth of Nations and the seat of the Commonwealth Secretariat. It was built in 1711 for Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marl ...

, as guests of his "Uncle Bertie" and "Aunt Alix", the Prince and Princess of Wales, where he was spoiled by his uncle.

Tsesarevich

On 1 March 1881, following

the assassination of his grandfather, Tsar Alexander II, Nicholas became heir apparent upon his father's accession as Alexander III. Nicholas and his other family members bore witness to Alexander II's death, having been present at the

Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now ...

in Saint Petersburg, where he was brought after the attack. For security reasons, the new Tsar and his family relocated their primary residence to the

Gatchina Palace

The Great Gatchina Palace (russian: Большой Гатчинский дворец) is a palace in Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It was built from 1766 to 1781 by Antonio Rinaldi for Count Grigori Grigoryevich Orlov, who was a favouri ...

outside the city, only entering the capital for various ceremonial functions. On such occasions, Alexander III and his family occupied the nearby

Anichkov Palace

The Anichkov Palace, a former imperial palace in Saint Petersburg, stands at the intersection of Nevsky Avenue and the Fontanka River.

History 18th century

The palace, situated on the plot formerly owned by Antonio de Vieira (1682?-1745), ...

.

In 1884, Nicholas's coming-of-age ceremony was held at the Winter Palace, where he pledged his loyalty to his father. Later that year, Nicholas's uncle,

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia (''Сергей Александрович''; 11 May 1857 – 17 February 1905) was the fifth son and seventh child of Emperor of All Russia, Emperor Alexander II of Russia. He was an influential figure ...

, married

Princess Elizabeth, daughter of

Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse

English: Frederick William Louis Charles

, house = Hesse-Darmstadt

, father = Prince Charles of Hesse and by Rhine

, mother = Princess Elisabeth of Prussia

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Prinz-Carl-Palais, Darmstadt, Gra ...

and his late wife

Princess Alice of the United Kingdom

Princess Alice (Alice Maud Mary; 25 April 1843 – 14 December 1878) was Grand Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine from 13 June 1877 until her death in 1878 as the wife of Grand Duke Louis IV. She was the third child and second daughter of Queen ...

(who had died in 1878), and a granddaughter of

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

. At the wedding in St. Petersburg, the sixteen-year-old Tsesarevich met with and admired the bride's youngest surviving sister, twelve-year-old

Princess Alix. Those feelings of admiration blossomed into love following her visit to St. Petersburg five years later in 1889. Alix had feelings for him in turn. As a devout Lutheran, she was initially reluctant to convert to Russian Orthodoxy to marry Nicholas, but later relented.

In 1890 Nicholas, his younger brother George, and their cousin

Prince George of Greece

Prince George of Greece and Denmark ( el, Γεώργιος; 24 June 1869 – 25 November 1957) was the second son and child of George I of Greece and Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, and is remembered chiefly for having once saved the life of h ...

, set out on a

world tour, although Grand Duke George fell ill and was sent home partway through the trip. Nicholas visited Egypt, India, Singapore, and Siam (Thailand), receiving honors as a distinguished guest in each country. During his trip through Japan, Nicholas had a large

dragon tattooed on his right forearm by Japanese tattoo artist Hori Chyo. His cousin George V of the United Kingdom had also received a dragon tattoo from Hori in

Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

years before. It was during his visit to

Otsu, that

Tsuda Sanzō

was a Japanese policeman who in 1891 attempted to assassinate the Tsesarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich of Russia (later Emperor Nicholas II), in what became known as the Ōtsu incident. He was convicted for attempted murder and sentenced to life imp ...

, one of his escorting policemen, swung at the Tsesarevich's face with a sabre, an event known as the

Ōtsu incident. Nicholas was left with a 9 centimeter long scar on the right side of his forehead, but his wound was not life-threatening. The incident cut his trip short.

Returning overland to St. Petersburg, he was present at the ceremonies in

Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, c ...

commemorating the beginning of work on the

Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

. In 1893, Nicholas traveled to London on behalf of his parents to be present at the wedding of his cousin

the Duke of York to

Princess Mary of Teck

Mary of Teck (Victoria Mary Augusta Louise Olga Pauline Claudine Agnes; 26 May 186724 March 1953) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 6 May 1910 until 20 January 1936 as the wife of King-Empe ...

. Queen Victoria was struck by the physical resemblance between the two cousins, and their appearances confused some at the wedding. During this time, Nicholas had an affair with St. Petersburg ballerina

Mathilde Kschessinska

Mathilde-Marie Feliksovna Kschessinska ( pl, Matylda Maria Krzesińska, russian: Матильда Феликсовна Кшесинская; 6 December 1971; also known as Princess Romanovskaya-Krasinskaya after her marriage) was a Polish ...

.

Though Nicholas was heir-apparent to the throne, his father failed to prepare him for his future role as Tsar. He attended meetings of the

State Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of South Korea, headed by the President

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative auth ...

; however, as his father was only in his forties, it was expected that it would be many years before Nicholas succeeded to the throne.

Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

, Russia's finance minister, saw things differently and suggested to the Tsar that Nicholas be appointed to the Siberian Railway Committee.

[Pierre, Andre (1925) ''Journal Intime de Nicholas II'', Paris: Payot, p. 45] Alexander argued that Nicholas was not mature enough to take on serious responsibilities, having once stated "Nikki is a good boy, but he has a poet's soul...God help him!" Witte stated that if Nicholas was not introduced to state affairs, he would never be ready to understand them.

Alexander's assumptions that he would live a long life and had years to prepare Nicholas for becoming Tsar proved wrong, as by 1894, Alexander's health was failing.

Engagement and marriage

In April 1894, Nicholas joined his Uncle Sergei and Aunt Elizabeth on a journey to Coburg, Germany, for the wedding of Elizabeth's and Alix's brother,

Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse

, spouses =

, issue =

, house = Hesse-Darmstadt

, father = Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine

, mother = Princess Alice of the United Kingdom

, birth_date =

, birth_place = New Palace, Darmstadt, Gra ...

, to their mutual first cousin

Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , later Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna of Russia (25 November 1876 – 2 March 1936), was the third child and second daughter of Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and of Grand Duchess M ...

. Other guests included Queen Victoria, Kaiser Wilhelm II, the

Empress Frederick

Victoria, Princess Royal (Victoria Adelaide Mary Louisa; 21 November 1840 – 5 August 1901) was German Empress and Queen of Prussia as the wife of German Emperor Frederick III. She was the eldest child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdo ...

(Kaiser Wilhelm's mother and Queen Victoria's eldest daughter), Nicholas's uncle, the

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, and the bride's parents,

the Duke and

Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

This is a list of the Duchesses, Electresses and Queens of Saxony; the consorts of the Duke of Saxony and its successor states; including the Electorate of Saxony, the Kingdom of Saxony, the House of Ascania, Albertine, and the Ernestine duchies, ...

.

Once in Coburg Nicholas proposed to Alix, but she rejected his proposal, being reluctant to convert to Orthodoxy. But the Kaiser later informed her she had a duty to marry Nicholas and to convert, as her sister Elizabeth had done in 1892. Thus once she changed her mind, Nicholas and Alix became officially engaged on 20 April 1894. Nicholas's parents initially hesitated to give the engagement their blessing, as Alix had made poor impressions during her visits to Russia. They gave their consent only when they saw Tsar Alexander's health deteriorating.

That summer, Nicholas travelled to England to visit both Alix and the Queen. The visit coincided with the birth of

the Duke and

Duchess of York's first child, the future

King Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

. Along with being present at the christening, Nicholas and Alix were listed among the child's godparents. After several weeks in England, Nicholas returned home for the wedding of his sister, Xenia, to a cousin,

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich ("Sandro").

By that autumn, Alexander III lay dying. Upon learning that he would live only a fortnight, the Tsar had Nicholas summon Alix to the imperial palace at

Livadia. Alix arrived on 22 October; the Tsar insisted on receiving her in full uniform. From his deathbed, he told his son to heed the advice of Witte, his most capable minister. Ten days later, Alexander III died at the age of forty-nine, leaving twenty-six-year-old Nicholas as Emperor of Russia. That evening, Nicholas was consecrated by his father's priest as Tsar Nicholas II and, the following day, Alix was received into the Russian Orthodox Church, taking the name Alexandra Feodorovna with the title of

Grand Duchess

Grand duke (feminine: grand duchess) is a European hereditary title, used either by certain monarchs or by members of certain monarchs' families. In status, a grand duke traditionally ranks in order of precedence below an emperor, as an approxi ...

and the style of ''

Imperial Highness His/Her Imperial Highness (abbreviation HIH) is a style used by members of an imperial family to denote ''imperial'' – as opposed to ''royal'' – status to show that the holder in question is descended from an emperor rather than a king ( ...

''.

Nicholas may have felt unprepared for the duties of the crown, for he asked his cousin and brother-in-law, Grand Duke Alexander, "What is going to happen to me and all of Russia?" Though perhaps under-prepared and unskilled, Nicholas was not altogether untrained for his duties as Tsar. Nicholas chose to maintain the conservative policies favoured by his father throughout his reign. While Alexander III had concentrated on the formulation of general policy, Nicholas devoted much more attention to the details of administration.

Leaving Livadia on 7 November, Tsar Alexander's funeral procession—which included Nicholas's maternal aunt through marriage and paternal first cousin once removed

Queen Olga of Greece, and the

Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. T ...

and

Princess of Wales—arrived in Moscow. After lying in state in the Kremlin, the body of the Tsar was taken to St. Petersburg, where the funeral was held on 19 November.

Nicholas and Alix's wedding was originally scheduled for the spring of 1895, but it was moved forward at Nicholas's insistence. Staggering under the weight of his new office, he had no intention of allowing the one person who gave him confidence to leave his side. Instead,

Nicholas's wedding to Alix took place on 26 November 1894, which was the birthday of the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, and court mourning could be slightly relaxed. Alexandra wore the traditional dress of Romanov brides, and Nicholas a

hussar's uniform. Nicholas and Alexandra, each holding a lit candle, faced the palace priest and were married a few minutes before one in the afternoon.

Accession and reign

Coronation

Despite a visit to the United Kingdom in 1893, where he observed the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in debate and was seemingly impressed by the machinery of

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, Nicholas turned his back on any notion of giving away any power to elected representatives in Russia. Shortly after he came to the

throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the mona ...

, a deputation of peasants and workers from various towns' local assemblies (''

zemstvos'') came to the Winter Palace proposing court reforms, such as the adoption of a constitutional monarchy, and reform that would improve the political and economic life of the peasantry, in the

Tver Address.

Although the addresses they had sent in beforehand were couched in mild and loyal terms, Nicholas was angry and ignored advice from an Imperial Family Council by saying to them:

On 26 May 1896, Nicholas's formal

coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of ot ...

as Tsar was held in

Uspensky Cathedral located within the

Kremlin.

[ Warth, p. 26]

In a celebration on 27 May 1896, a large festival with food, free beer and souvenir cups was held in

Khodynka Field

Khodynka Field (russian: Ходынское поле, ''Khodynskoye pole'') is a large open space in the north-west of Moscow, at the beginning of the present day Leningradsky Prospect. It takes its name from the small Khodynka River which used ...

outside Moscow. Khodynka was chosen as the location as it was the only place near Moscow large enough to hold all of the Moscow citizens.

[ Massie (1967) p. 1017] Khodynka was primarily used as a military training ground and the field was uneven with trenches. Before the food and drink was handed out, rumours spread that there would not be enough for everyone. As a result, the crowd rushed to get their share and individuals were tripped and trampled upon, suffocating in the dirt of the field. Of the approximate 100,000 in attendance, it is estimated that 1,389 individuals died

and roughly 1,300 were injured.

The Khodynka Tragedy was seen as an ill omen and Nicholas found gaining popular trust difficult from the beginning of his reign. The French ambassador's gala was planned for that night. The Tsar wanted to stay in his chambers and pray for the lives lost, but his uncles believed that his absence at the ball would strain relations with France, particularly the 1894

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (french: Alliance Franco-Russe, russian: Франко-Русский Альянс, translit=Franko-Russkiy Al'yans), or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Russo-Français'', Русско-Французско� ...

. Thus Nicholas attended the party; as a result the mourning populace saw Nicholas as frivolous and uncaring.

During the autumn after the coronation, Nicholas and Alexandra made a tour of Europe. After making visits to the emperor and empress of Austria-Hungary, the Kaiser of Germany, and Nicholas's Danish grandparents and relatives, Nicholas and Alexandra took possession of their new yacht, the ''

Standart, ''which had been built in Denmark. From there, they made a journey to Scotland to spend some time with Queen Victoria at

Balmoral Castle. While Alexandra enjoyed her reunion with her grandmother, Nicholas complained in a letter to his mother about being forced to go shooting with his uncle, the Prince of Wales, in bad weather, and was suffering from a bad toothache.

The first years of his reign saw little more than continuation and development of the policy pursued by Alexander III. Nicholas allotted money for the

All-Russia exhibition of 1896. In 1897 restoration of

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

by Sergei Witte, Minister of Finance, completed the series of financial reforms, initiated fifteen years earlier. By 1902 the Trans-Siberian Railway was nearing completion; this helped the Russians trade in the Far East but the railway still required huge amounts of work.

Ecclesiastical affairs

Nicholas always believed God chose him to be the tsar and therefore the decisions of the tsar reflected the will of God and could not be disputed. He was convinced that the simple people of Russia understood this and loved him, as demonstrated by the display of affection he perceived when he made public appearances. His old-fashioned belief made for a very stubborn ruler who rejected constitutional limitations on his power. It put the tsar at variance with the emerging political consensus among the Russian elite. It was further belied by the subordinate position of the Church in the bureaucracy. The result was a new distrust between the tsar and the church hierarchy and between those hierarchs and the people. Thereby the tsar's base of support was conflicted.

In 1903, Nicholas threw himself into an ecclesiastical crisis regarding the

canonisation

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

of

Seraphim of Sarov

Seraphim of Sarov (russian: Серафим Саровский; – ), born Prókhor Isídorovich Moshnín (Mashnín) �ро́хор Иси́дорович Мошни́н (Машни́н) is one of the most renowned Russian saints and is venerate ...

. The previous year, it had been suggested that if he were canonised, the imperial couple would beget a son and heir to throne. While Alexandra demanded in July 1902 that Seraphim be canonised in less than a week, Nicholas demanded that he be canonised within a year. Despite a public outcry, the Church bowed to the intense imperial pressure, declaring Seraphim worthy of canonisation in January 1903. That summer, the imperial family travelled to Sarov for the canonisation.

Initiatives in foreign affairs

According to his biographer:

: His tolerance if not preference for charlatans and adventurers extended to grave matters of external policy, and his vacillating conduct and erratic decisions aroused misgivings and occasional alarm among his more conventional advisers. The foreign ministry itself was not a bastion of diplomatic expertise. Patronage and "connections" were the keys to appointment and promotion.

Emperor

Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

of Austria-Hungary paid a state visit in April 1897 that was a success. It produced a "gentlemen's agreement" to keep the status quo in the Balkans, and a somewhat similar commitment became applicable to Constantinople and the Straits. The result was years of peace that allowed for rapid economic growth.

Nicholas followed the policies of his father, strengthening the Franco-Russian Alliance and pursuing a policy of general European pacification, which culminated in the famous

Hague peace conference

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amo ...

. This conference, suggested and promoted by Nicholas II, was convened with the view of terminating the

arms race, and setting up machinery for the peaceful settlement of international disputes. The results of the conference were less than expected due to the mutual distrust existing between great powers. Nevertheless, the Hague conventions were among the first formal statements of the laws of war. Nicholas II became the hero of the dedicated disciples of peace. In 1901 he and the Russian diplomat

Friedrich Martens

Friedrich Fromhold Martens, or Friedrich Fromhold von Martens,, french: Frédéric Frommhold (de) Martens ( – ) was a diplomat and jurist in service of the Russian Empire who made important contributions to the science of international law. H ...

were nominated for the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

for the initiative to convene the Hague Peace Conference and contributing to its implementation. However historian Dan L. Morrill states that "most scholars" agree that the invitation was "conceived in fear, brought forth in deceit, and swaddled in humanitarian ideals...Not from humanitarianism, not from love for mankind."

Russo-Japanese War

A clash between Russia and the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

was almost inevitable by the turn of the 20th century. Russia had expanded in the Far East, and the growth of its settlement and territorial ambitions, as its southward path to the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

was frustrated, conflicted with Japan's own territorial ambitions on the Asian mainland. Nicholas pursued an aggressive foreign policy with regards to

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

and

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, and strongly supported the scheme for timber concessions in these areas as developed by the

Bezobrazov group.

[Kowner, '' Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War'', pp. 260–264.][Raymond A. Esthus, "Nicholas II and the Russo-Japanese War." ''The Russian Review'' 40.4 (1981): 396–411]

online

/ref>

Before the war in 1901, Nicholas told Prince Henry of Prussia "I do not want to seize Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

but under no circumstances can I allow Japan to become firmly established there. That will be a casus belli."

War began in February 1904 with a preemptive Japanese attack on the Russian fleet in Port Arthur, prior to a formal declaration of war.Dogger Bank incident

The Dogger Bank incident (also known as the North Sea Incident, the Russian Outrage or the Incident of Hull) occurred on the night of 21/22 October 1904, when the Baltic Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy mistook a British trawler fleet from ...

where the Baltic Fleet mistakenly fired on British fishing boats in the North Sea. The Baltic Fleet traversed the world to lift the blockade on Port Arthur, but after many misadventures on the way, was nearly annihilated by the Japanese in the Battle of the Tsushima Strait.St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, combat took place in east Asian ports with only the Trans-Siberian Railway for transport of supplies as well as troops both ways.Treaty of Portsmouth

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

.

Tsar's confidence in victory

Nicholas's stance on the war was so at variance with the obvious facts that many observers were baffled. He saw the war as an easy God-given victory that would raise Russian morale and patriotism. He ignored the financial repercussions of a long-distance war. Rotem Kowner argues that during his visit to Japan in 1891, where Nicholas was attacked by a Japanese policeman, he regarded the Japanese as small of stature, feminine, weak, and inferior. He ignored reports of the prowess of Japanese soldiers in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) and reports on the capabilities of the Japanese fleet, as well as negative reports on the lack of readiness of Russian forces.[Rotem Kowner, "Nicholas II and the Japanese body: Images and decision-making on the eve of the Russo-Japanese War." ''Psychohistory Review'' (1998) 26#3 pp 211–252]

online

Before the Japanese attack on Port Arthur, Nicholas held firm to the belief that there would be no war. Despite the onset of the war and the many defeats Russia suffered, Nicholas still believed in, and expected, a final victory, maintaining an image of the racial inferiority and military weakness of the Japanese. Throughout the war, the tsar demonstrated total confidence in Russia's ultimate triumph. His advisors never gave him a clear picture of Russia's weaknesses. Despite the continuous military disasters Nicholas believed victory was near at hand. Losing his navy at Tsushima finally persuaded him to agree to peace negotiations. Even then he insisted on the option of reopening hostilities if peace conditions were unfavorable. He forbade his chief negotiator Count Witte to agree to either indemnity payments or loss of territory. Nicholas remained adamantly opposed to any concessions. Peace was made, but Witte did so by disobeying the tsar and ceding southern Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh ...

to Japan.

Anti-Jewish pogroms of 1903–1906

The Kishinev newspaper ''Bessarabets'', which published anti-Semitic materials, received funds from Viacheslav Plehve, Minister of the Interior. These publications served to fuel the Kishinev pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . A second pogrom erupted in the city in Octob ...

(rioting). The government of Nicholas II formally condemned the rioting and dismissed the regional governor, with the perpetrators arrested and punished by the court. Leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church also condemned anti-Semitic pogroms. Appeals to the faithful condemning the pogroms were read publicly in all churches of Russia. In private Nicholas expressed his admiration for the mobs, viewing anti-Semitism as a useful tool for unifying the people behind the government; however in 1911, following the assassination of Pyotr Stolypin by the Jewish revolutionary Dmitry Bogrov

Dmitry Grigoriyevich Bogrov ( – ) () was the assassin of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin.

On Bogrow was sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on in the Kiev fortress Lyssa Hora.

Stolypin's widow had campaigned in vain to spare the ass ...

, he approved of government efforts to prevent anti-Semitic pogroms.

Bloody Sunday (1905)

A few days prior to Bloody Sunday (9 (22) January 1905), priest and labor leader Georgy Gapon

Georgy Apollonovich Gapon. ( –) was a Russian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox priest and a popular working-class leader before the 1905 Russian Revolution. After he was discovered to be a police informant, Gapon was murdered by members of the ...

informed the government of the forthcoming procession to the Winter Palace to hand a workers' petition to the Tsar. On Saturday, 8 (21) January, the ministers convened to consider the situation. There was never any thought that the Tsar, who had left the capital for Tsarskoye Selo on the advice of the ministers, would actually meet Gapon; the suggestion that some other member of the imperial family receive the petition was rejected.[ Massie (1967) p. 124]

Finally informed by the Prefect of Police that he lacked the men to pluck Gapon from among his followers and place him under arrest, the newly appointed Minister of the Interior, Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky, and his colleagues decided to bring additional troops to reinforce the city. That evening Nicholas wrote in his diary, "Troops have been brought from the outskirts to reinforce the garrison. Up to now the workers have been calm. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of their union is a kind of socialist priest named Gapon. Mirsky came this evening to present his report on the measures taken."[ Massie (1967) pp. 124–125]

The official number of victims was 92 dead and several hundred wounded. Gapon vanished and the other leaders of the march were seized. Expelled from the capital, they circulated through the empire, increasing the casualties. As bullets riddled their icons, their banners and their portraits of Nicholas, the people shrieked, "The Tsar will not help us!"Tsarism

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

."

1905 Revolution

Confronted with growing opposition and after consulting with Witte and Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky, the Tsar issued a reform

Confronted with growing opposition and after consulting with Witte and Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky, the Tsar issued a reform ukase

In Imperial Russia, a ukase () or ukaz (russian: указ ) was a proclamation of the tsar, government, or a religious leader ( patriarch) that had the force of law. " Edict" and "decree" are adequate translations using the terminology and concep ...

on 25 December 1904 with vague promises.

In hopes of cutting the rebellion short, many demonstrators were shot on Bloody Sunday (1905)

Bloody Sunday or Red Sunday ( rus, Крова́вое воскресе́нье, r=Krovávoe voskresénje, p=krɐˈvavəɪ vəskrʲɪˈsʲenʲjɪ) was the series of events on Sunday, in St Petersburg, Russia, when unarmed demonstrators, led by ...

as they tried to march to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov

Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov (transliterated at the time as Trepoff) (15 December 1850 – 15 September 1906) was Head of the Moscow police, Governor-General of St. Petersburg with extraordinary powers, and Assistant Interior Minister with full contr ...

was ordered to take drastic measures to stop the revolutionary activity. Grand Duke Sergei was killed in February by a revolutionary's bomb in Moscow as he left the Kremlin. On 3 March the Tsar condemned the revolutionaries. Meanwhile, Witte recommended that a manifesto be issued. Schemes of reform would be elaborated by Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (russian: Ива́н Лóггинович Горемы́кин, Iván Lógginovich Goremýkin) (8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Russia, prime minister of th ...

and a committee consisting of elected representatives of the zemstvos and municipal councils under the presidency of Witte. In June the battleship ''Potemkin'', part of the Black Sea Fleet, mutinied

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

.

Around August/September, after his diplomatic success on ending the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, Witte wrote to the Tsar stressing the urgent need for political reforms at home. The Tsar remained quite impassive and indulgent; he spent most of that autumn hunting. With the defeat of Russia by a non-Western power, the prestige and authority of the autocratic regime fell significantly. Tsar Nicholas II, taken by surprise by the events, reacted with anger and bewilderment. He wrote to his mother after months of disorder:

In October a railway strike developed into a general strike which paralysed the country. In a city without electricity, Witte told Nicholas II "that the country was at the verge of a cataclysmic revolution". The Tsar accepted the draft, hurriedly outlined by Aleksei D. Obolensky

{{For, the rural localities in Kaluga Oblast, Russia, Obolenskoye

The House of Obolensky (russian: Оболенский) is the name of a princely Russian family of the Rurik dynasty. The family of aristocrats mostly fled Russia in 1917 during the ...

. The ''Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias'' was forced to sign the October Manifesto agreeing to the establishment of the Imperial Duma, and to give up part of his unlimited autocracy. The freedom of religion clause outraged the Church because it allowed people to switch to evangelical Protestantism, which they denounced as heresy.

For the next six months, Witte was the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

. According to Harold Williams: "That government was almost paralyzed from the beginning." On 26 October (O.S.) the Tsar appointed Trepov Master of the Palace (without consulting Witte), and had daily contact with the Emperor; his influence at court was paramount. On 1 November 1905 (O.S.), Princess Milica of Montenegro

Princess Milica Petrović-Njegoš of Montenegro, also known as Grand Duchess Militza Nikolaevna of Russia, (14 July 1866 – 5 September 1951) was a Montenegrin princess. She was the daughter of King Nikola I Petrović-Njegoš of Montenegro ...

presented Grigori Rasputin to Tsar Nicholas and his wife (who by then had a hemophiliac son) at Peterhof Palace

The Peterhof Palace ( rus, Петерго́ф, Petergóf, p=pʲɪtʲɪrˈɡof,) (an emulation of early modern Dutch "Pieterhof", meaning "Pieter's Court"), is a series of palaces and gardens located in Petergof, Saint Petersburg, Russia, commi ...

.

Relationship with the Duma

Under pressure from the attempted 1905 Russian Revolution, on 5 August of that year Nicholas II issued a manifesto about the convocation of the State Duma, known as the Bulygin Duma, initially thought to be an advisory organ. In the October Manifesto, the Tsar pledged to introduce basic civil liberties, provide for broad participation in the State Duma, and endow the Duma with legislative and oversight powers. He was determined, however, to preserve his autocracy even in the context of reform. This was signalled in the text of the 1906 constitution. He was described as the supreme autocrat, and retained sweeping executive powers, also in church affairs. His cabinet ministers were not allowed to interfere with nor assist one another; they were responsible only to him.

Nicholas's relations with the Duma were poor. The

Under pressure from the attempted 1905 Russian Revolution, on 5 August of that year Nicholas II issued a manifesto about the convocation of the State Duma, known as the Bulygin Duma, initially thought to be an advisory organ. In the October Manifesto, the Tsar pledged to introduce basic civil liberties, provide for broad participation in the State Duma, and endow the Duma with legislative and oversight powers. He was determined, however, to preserve his autocracy even in the context of reform. This was signalled in the text of the 1906 constitution. He was described as the supreme autocrat, and retained sweeping executive powers, also in church affairs. His cabinet ministers were not allowed to interfere with nor assist one another; they were responsible only to him.

Nicholas's relations with the Duma were poor. The First Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four tim ...

, with a majority of Kadets, almost immediately came into conflict with him. Scarcely had the 524 members sat down at the Tauride Palace

Tauride Palace (russian: Таврический дворец, translit=Tavrichesky dvorets) is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride ...

when they formulated an 'Address to the Throne'. It demanded universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

, radical land reform, the release of all political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s and the dismissal of ministers appointed by the Tsar in favour of ministers acceptable to the Duma. Grand Duchess Olga, Nicholas's sister, later wrote:

Minister of the Court Count Vladimir Frederiks

Count Adolf Andreas Woldemar Freedericksz (russian: links=no, Владимир Борисович Фредерикс, Vladimir Borisovich Frederiks; 1 July 1927) was a Finno-Russian statesman who served as Imperial Household Minister between 189 ...

commented, "The Deputies, they give one the impression of a gang of criminals who are only waiting for the signal to throw themselves upon the ministers and cut their throats. I will never again set foot among those people."[ Massie (1967) p. 242] The Dowager Empress noticed "incomprehensible hatred."Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky

The Imperial Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky was an order of chivalry of the Russian Empire first awarded on by Empress Catherine I of Russia.

History

The introduction of the Imperial Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky was envisioned by Emperor ...

with diamonds (the last two words were written in the Emperor's own hand, followed by "I remain unalterably well-disposed to you and sincerely grateful, for ever more Nicholas.").

A second Duma met for the first time in February 1907. The leftist parties—including the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

and the Social Revolutionaries, who had boycotted the First Duma—had won 200 seats in the Second, more than a third of the membership. Again Nicholas waited impatiently to rid himself of the Duma. In two letters to his mother he let his bitterness flow:

A little while later he further wrote:

After the

After the Second Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four ti ...

resulted in similar problems, the new prime minister Pyotr Stolypin (whom Witte described as "reactionary") unilaterally dissolved it, and changed the electoral laws to allow for future Dumas to have a more conservative content, and to be dominated by the liberal-conservative Octobrist

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in la ...

Party of Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Гучко́в) (14 October 1862 – 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government. ...

. Stolypin, a skilful politician, had ambitious plans for reform. These included making loans available to the lower classes to enable them to buy land, with the intent of forming a farming class loyal to the crown. Nevertheless, when the Duma remained hostile, Stolypin had no qualms about invoking Article 87 of the Fundamental Laws, which empowered the Tsar to issue 'urgent and extraordinary' emergency decrees 'during the recess of the State Duma'. Stolypin's most famous legislative act, the change in peasant land tenure, was promulgated under Article 87.[ Massie (1967) p. 246] Nevertheless, Stolypin's plans were undercut by conservatives at court. Although the tsar at first supported him, he finally sided with the arch critics. Reactionaries such as Prince Vladimir Nikolayevich Orlov

Prince Vladimir Nikolayevich Orlov (Dec. 31, 1868-Aug. 29, 1927), part of the Orlov family, was one of Tsar Nicholas II's closest advisors, and between 1906 and 1915 headed the Tsar's military cabinet.

Biography

Orlov, who bore the nickname "Fa ...

never tired of telling the tsar that the very existence of the Duma was a blot on the autocracy. Stolypin, they whispered, was a traitor and secret revolutionary who was conniving with the Duma to steal the prerogatives assigned the Tsar by God. Witte also engaged in constant intrigue against Stolypin. Although Stolypin had had nothing to do with Witte's fall, Witte blamed him. Stolypin had unwittingly angered the Tsaritsa. He had ordered an investigation into Rasputin and presented it to the Tsar, who read it but did nothing. Stolypin, on his own authority, ordered Rasputin to leave St. Petersburg. Alexandra protested vehemently but Nicholas refused to overrule his Prime Minister,[ Massie (1967) p. 247.] who had more influence with the Emperor.

By the time of Stolypin's assassination in September 1911, Stolypin had grown weary of the burdens of office. For a man who preferred clear decisive action, working with a sovereign who believed in fatalism and mysticism was frustrating. As an example, Nicholas once returned a document unsigned with the note:

Alexandra, believing that Stolypin had severed the bonds that her son depended on for life, hated the Prime Minister.

Alexandra, believing that Stolypin had severed the bonds that her son depended on for life, hated the Prime Minister.Bernard Pares

Sir Bernard Pares KBE (1 March 1867 – 17 April 1949) was an English historian and diplomat. During the First World War, he was seconded to the Foreign Ministry in Petrograd, Russia, where he reported political events back to London, and worke ...

.First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

developed badly for Russia. By late 1916, Romanov family desperation reached the point that Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich

Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia (russian: Павел Александрович; 3 October 1860 – 28 January 1919) was the sixth son and youngest child of Emperor Alexander II of Russia by his first wife, Empress Maria Alexandrov ...

, younger brother of Alexander III and the Tsar's only surviving uncle, was deputed to beg Nicholas to grant a constitution and a government responsible to the Duma. Nicholas sternly and adamantly refused, reproaching his uncle for asking him to break his coronation oath to maintain autocratic power for his successors. In the Duma on 2 December 1916, Vladimir Purishkevich, a fervent patriot, monarchist and war worker, denounced the dark forces which surrounded the throne in a thunderous two-hour speech which was tumultuously applauded. "Revolution threatens," he warned, "and an obscure peasant shall govern Russia no longer!"

Tsarevich Alexei's illness and Rasputin

Further complicating domestic matters was the matter of the succession. Alexandra bore Nicholas four daughters, the Grand Duchess Olga in 1895, the Grand Duchess Tatiana in 1897, Grand Duchess Maria in 1899, and

Further complicating domestic matters was the matter of the succession. Alexandra bore Nicholas four daughters, the Grand Duchess Olga in 1895, the Grand Duchess Tatiana in 1897, Grand Duchess Maria in 1899, and Grand Duchess Anastasia

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

* Grand Mixer DXT, American turntablist

* Grand Puba (born 1966), American rapper

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma

* Grand, Vosges, village and co ...

in 1901, before their son Alexei was born on 12 August 1904. The young heir was afflicted with Hemophilia B

Haemophilia B, also spelled hemophilia B, is a blood clotting disorder causing easy bruising and bleeding due to an inherited mutation of the gene for factor IX, and resulting in a deficiency of factor IX. It is less common than factor VIII defi ...

, a hereditary disease that prevents blood from clotting properly, which at that time was untreatable and usually led to an untimely death. As a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, Alexandra carried the same gene mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitos ...

that afflicted several of the major European royal houses, such as Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

and Spain. Hemophilia, therefore, became known as " the royal disease". Through Alexandra, the disease had passed on to her son. As all of Nicholas and Alexandra's daughters were assassinated with their parents and brother in Yekaterinburg in 1918, it is not known whether any of them inherited the gene as carriers.

Before Rasputin's arrival, the tsarina and the tsar had consulted numerous mystics, charlatans, "holy fools", and miracle workers. The royal behavior was not some odd aberration, but a deliberate retreat from the secular social and economic forces of his time – an act of faith and vote of confidence in a spiritual past. They had set themselves up for the greatest spiritual advisor and manipulator in Russian history.

Because of the fragility of the autocracy at this time, Nicholas and Alexandra chose to keep secret Alexei's condition. Even within the household, many were unaware of the exact nature of the Tsarevich's illness. At first Alexandra turned to Russian doctors and medics to treat Alexei; however, their treatments generally failed, and Alexandra increasingly turned to mystics and holy men (or ''starets

A starets (russian: стáрец, p=ˈstarʲɪt͡s; fem. ) is an elder of an Eastern Orthodox monastery who functions as venerated adviser and teacher. ''Elders'' or ''spiritual fathers'' are charismatic spiritual leaders whose wisdom stems from Go ...

'' as they were called in Russian). One of these starets, an illiterate Siberian named Grigori Rasputin, gained amazing success. Rasputin's influence over Empress Alexandra, and consequently the Tsar himself, grew even stronger after 1912 when the Tsarevich nearly died from an injury. His bleeding grew steadily worse as doctors despaired, and priests administered the Last Sacrament. In desperation, Alexandra called upon Rasputin, to which he replied, "God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much." The hemorrhage stopped the very next day and the boy began to recover. Alexandra took this as a sign that Rasputin was a ''starets'' and that God was with him; for the rest of her life she would fervently defend him and turn her wrath against anyone who dared to question him.

European affairs

In 1907, to end longstanding controversies over central Asia, Russia and the United Kingdom signed the

In 1907, to end longstanding controversies over central Asia, Russia and the United Kingdom signed the Anglo-Russian Convention

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (russian: Англо-Русская Конвенция 1907 г., translit=Anglo-Russkaya Konventsiya 1907 g.), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ...

that resolved most of the problems generated for decades by The Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

. The UK had already entered into the Entente cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

with France in 1904, and the Anglo-Russian convention led to the formation of the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

. The following year, in May 1908, Nicholas and Alexandra's shared "Uncle Bertie" and "Aunt Alix", Britain's King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, made a state visit to Russia, being the first reigning British monarchs to do so. However, they did not set foot on Russian soil. Instead, they stayed aboard their yachts, meeting off the coast of modern-day Tallinn

Tallinn () is the most populous and capital city of Estonia. Situated on a bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, Tallinn has a population of 437,811 (as of 2022) and administratively lies in the Harju '' ...

. Later that year, Nicholas was taken off guard by the news that his foreign minister, Alexander Izvolsky

Count Alexander Petrovich Izvolsky or Iswolsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Петро́вич Изво́льский, , Moscow – 16 August 1919, Paris) was a Russian diplomat remembered as a major architect of Russia's alliance with Grea ...

, had entered into a secret agreement with the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister, Count Alois von Aehrenthal, agreeing that, in exchange for Russian naval access to the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

and the Bosporus Strait, Russia would not oppose the Austrian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

, a revision of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. When Austria-Hungary did annex this territory that October, it precipitated the diplomatic crisis. When Russia protested about the annexation, the Austrians threatened to leak secret communications between Izvolsky and Aehernthal, prompting Nicholas to complain in a letter to the Austrian emperor, Franz Joseph