Nicholas Ridley (martyr) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Summoned to answer to the Privy Council and archbishop—who were primarily concerned with Hooper's willingness to accept the royal supremacy, which was also part of the oath for newly ordained clergy—Hooper evidently made sufficient reassurances, as he was soon appointed to the

Summoned to answer to the Privy Council and archbishop—who were primarily concerned with Hooper's willingness to accept the royal supremacy, which was also part of the oath for newly ordained clergy—Hooper evidently made sufficient reassurances, as he was soon appointed to the

In a

In a

On 2 February 1553 Cranmer was ordered to appoint John Knox, a Scot, as vicar of All Hallows, Bread Street in London, placing him under the authority of Ridley. Knox returned to London in order to deliver a sermon before the king and the court during Lent, after which he refused to take his assigned post. That same year, Ridley pleaded with

On 2 February 1553 Cranmer was ordered to appoint John Knox, a Scot, as vicar of All Hallows, Bread Street in London, placing him under the authority of Ridley. Knox returned to London in order to deliver a sermon before the king and the court during Lent, after which he refused to take his assigned post. That same year, Ridley pleaded with

The sentence was carried out on 16 October 1555 in Oxford. Cranmer was taken to a tower to watch the proceedings. Ridley burned extremely slowly and suffered a great deal: his brother-in-law had put more tinder on the pyre in order to speed his death, but this only caused his lower parts to burn. Latimer is supposed to have said to Ridley, "Be of good comfort, and play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God's grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out." This was quoted in ''

The sentence was carried out on 16 October 1555 in Oxford. Cranmer was taken to a tower to watch the proceedings. Ridley burned extremely slowly and suffered a great deal: his brother-in-law had put more tinder on the pyre in order to speed his death, but this only caused his lower parts to burn. Latimer is supposed to have said to Ridley, "Be of good comfort, and play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God's grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out." This was quoted in '' In 1881, Ridley Hall in

In 1881, Ridley Hall in

Keeping the Faith

(

Nicholas Ridley ( – 16 October 1555) was an

's supremacy. Ridley was well versed on English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

(the only bishop called "Bishop of London and Westminster"). Ridley was one of the Oxford Martyrs burned at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

during the Marian Persecutions

Protestants were executed in England under heresy laws during the reigns of Henry VIII (1509–1547) and Mary I (1553–1558). Radical Christians also were executed, though in much smaller numbers, during the reigns of Edward VI (1547–155 ...

, for his teachings and his support of Lady Jane Grey. He is remembered with a commemoration

Commemoration may refer to:

*Commemoration (Anglicanism), a religious observance in Churches of the Anglican Communion

*Commemoration (liturgy)

In the Latin liturgical rites of the Catholic Church, a commemoration is the recital, within the Li ...

in the calendar of saints

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context d ...

(with Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer ( – 16 October 1555) was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, and Bishop of Worcester during the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555 under the Catholic Queen Mary I he was burned at the ...

) in some parts of the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

(Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

) on 16 October.

Early years and advancement (c.1500–50)

Ridley came from a prominent family inTynedale

__NOTOC__

Tynedale is an area and former local government district in south-west Northumberland, England. The district had a resident population of 58,808 according to the 2001 Census. Its main towns were Hexham, Haltwhistle and Prudhoe. Th ...

, Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

. He was the second son of Christopher Ridley, first cousin to Lancelot Ridley and grew up in Unthank Hall

Unthank Hall is a Grade II listed property now serving as commercial offices, situated on the southern bank of the River South Tyne east of Plenmeller, near Haltwhistle, Northumberland.

In the 16th century the manor was owned by the Ridley famil ...

from the old House of Unthank located on the site of an ancient watch tower or pele tower

Peel towers (also spelt pele) are small fortified keeps or tower houses, built along the English and Scottish borders in the Scottish Marches and North of England, mainly between the mid-14th century and about 1600. They were free-standing ...

. As a boy, Ridley was educated at the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle

(By Learning, You Will Lead)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Grammar SchoolIndependent day school

, religion =

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Geoffrey Stanford

, r_head_label =

, r_head =

, chair_label =

, cha ...

, and Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he proceeded to Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Th ...

in 1525.Biblical hermeneutics

Biblical hermeneutics is the study of the principles of interpretation concerning the books of the Bible. It is part of the broader field of hermeneutics, which involves the study of principles of interpretation, both theory and methodology, for ...

, and through his arguments the university came up with the following resolution: "That the Bishop of Rome had no more authority and jurisdiction derived to him from God, in this kingdom of England, than any other foreign bishop." He graduated B.D. in 1537 and was then appointed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry ...

, to serve as one of his chaplains. In April 1538, Cranmer made him vicar of Herne, in Kent.

In 1540–1, he was made one of the King's Chaplains, and was also presented with a prebendal stall

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

in Canterbury Cathedral. In 1540 he was made Master of Pembroke College and in 1541 was awarded the degree of Doctor of Divinity. In 1543 he was accused of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, but he was able to beat the charge. Cranmer had resolved to support the English Reformation by gradually replacing the old guard in his ecclesiastical province

An ecclesiastical province is one of the basic forms of jurisdiction in Christian Churches with traditional hierarchical structure, including Western Christianity and Eastern Christianity. In general, an ecclesiastical province consists of seve ...

with men who followed the new thinking. Ridley was made the Bishop of Rochester in 1547, and shortly after coming to office, directed that the altars in the churches of his diocese should be removed, and tables put in their place to celebrate the Lord's Supper

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

. In 1548 he helped Cranmer compile the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

and in 1549 he was one of the commissioners who investigated Bishops Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 – 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip.

Early life

Gardiner was ...

and Edmund Bonner. He concurred that they should be removed. John Ponet

John Ponet (c. 1514 – August 1556), sometimes spelled John Poynet, was an English Protestant churchman and controversial writer, the bishop of Winchester and Marian exile. He is now best known as a resistance theorist who made a sustained at ...

took Ridley's former position. Incumbent conservatives were uprooted and replaced with reformers.

When Ridley was appointed to the see of London by letters patent on 1 April 1550, he was called the "Bishop of London and Westminster" because the Diocese of London had just re-absorbed the dissolved Diocese of Westminster.

Vestments controversy (1550–3)

Ridley played a major part in thevestments controversy

The vestments controversy or vestarian controversy arose in the English Reformation, ostensibly concerning vestments or clerical dress. Initiated by John Hooper's rejection of clerical vestments in the Church of England under Edward VI as des ...

. John Hooper, having been exiled during King Henry's reign, returned to England in 1548 from the churches in Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich ...

that had been reformed by Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

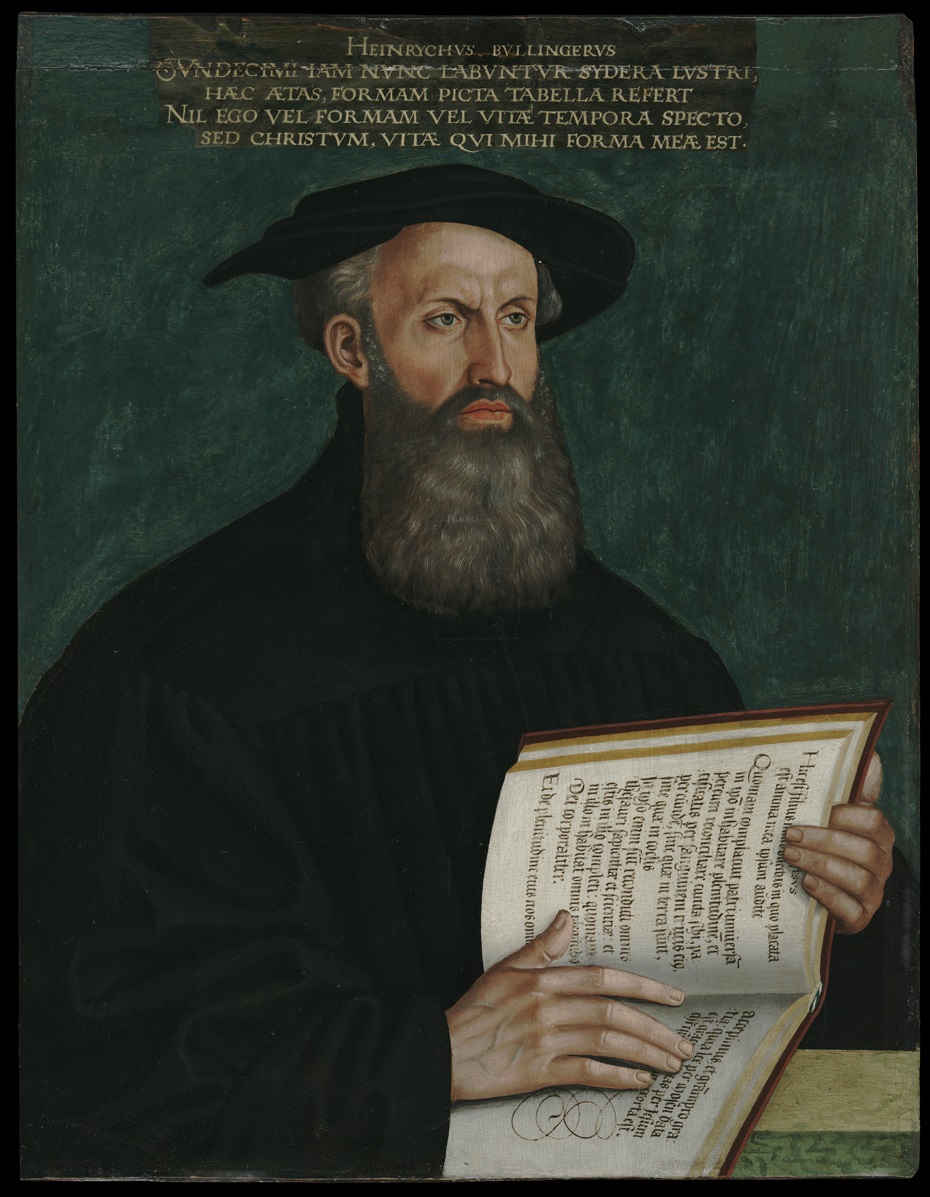

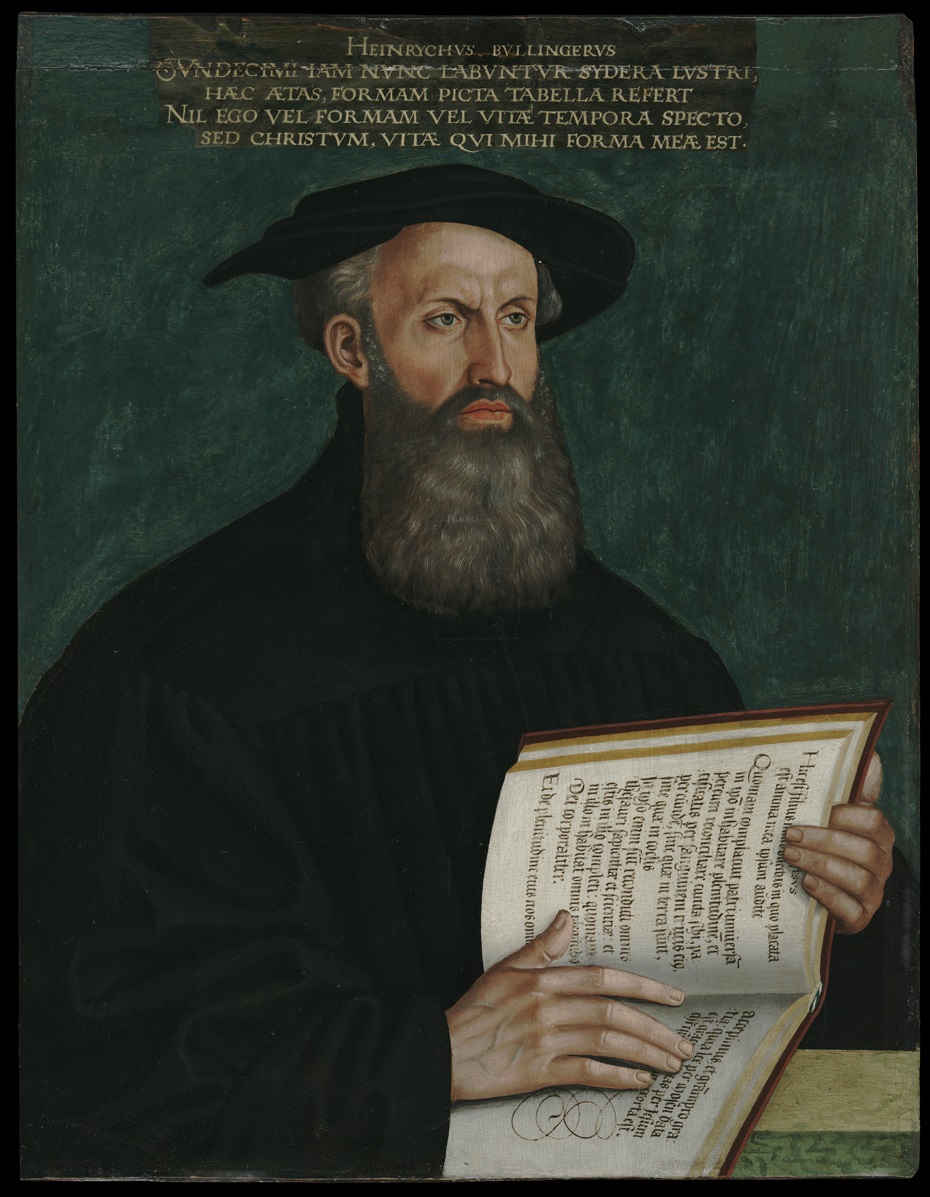

and Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss R ...

in a highly iconoclastic

Iconoclasm (from Ancient Greek, Greek: grc, wikt:εἰκών, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, wikt:κλάω, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, wikt:εἰκών, εἰκών + wi ...

fashion. When Hooper was invited to give a series of Lenten

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

sermons

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. E ...

before the king in February 1550, he spoke against Cranmer's 1549 ordinal whose oath mentioned "all saints" and required newly elected bishops and those attending the ordination ceremony to wear a cope

The cope (known in Latin as ''pluviale'' 'rain coat' or ''cappa'' 'cape') is a liturgical vestment, more precisely a long mantle or cloak, open in front and fastened at the breast with a band or clasp. It may be of any liturgical colour.

A c ...

and surplice. In Hooper's view, these requirements were vestiges of Judaism and Roman Catholicism, which had no biblical warrant for Christians since they were not used in the early Christian church.;

Summoned to answer to the Privy Council and archbishop—who were primarily concerned with Hooper's willingness to accept the royal supremacy, which was also part of the oath for newly ordained clergy—Hooper evidently made sufficient reassurances, as he was soon appointed to the

Summoned to answer to the Privy Council and archbishop—who were primarily concerned with Hooper's willingness to accept the royal supremacy, which was also part of the oath for newly ordained clergy—Hooper evidently made sufficient reassurances, as he was soon appointed to the bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

of Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

. Hooper declined the office, however, because of the required vestments and oath by the saints. The king accepted Hooper's position, but the Privy Council did not. Called before them on 15 May 1550, a compromise was reached. Vestments were to be considered a matter of adiaphora, or ''Res Indifferentes'' ("things indifferent", as opposed to an article of faith), and Hooper could be ordained without them at his discretion, but he must allow that others could wear them. Hooper passed confirmation of the new office again before the king and council on 20 July 1550 when the issue was raised again, and Cranmer was instructed that Hooper was not to be charged "with an oath burdensome to his conscience".

Cranmer assigned Ridley to perform the consecration, and Ridley refused to do anything but follow the form of the ordinal as it had been prescribed by Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

. Ridley, it seems likely, had some particular objection to Hooper. It has been suggested that Henrician exiles like Hooper, who had experienced some of the more radically reformed churches on the continent, were at odds with English clergy who had accepted and never left the established church. John Henry Primus also notes that on 24 July 1550, the day after receiving instructions for Hooper's unique consecration, the church of the Austin Friars in London had been granted to Jan Laski for use as a Stranger church

Strangers' church was a term used by English-speaking people for independent Protestant churches established in foreign lands or by foreigners in England during the Reformation. (The spelling stranger church is also found in texts of the period ...

. This was to be a designated place of worship for Continental Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

refugees, a church with forms and practices that had taken reforms much further than Ridley would have liked. This development—the use of a London church virtually outside Ridley's jurisdiction—was one that Hooper had had a hand in.

The Privy Council reiterated its position, and Ridley responded in person, agreeing that vestments are indifferent but making a compelling argument that the monarch may require indifferent things without exception. The council became divided in opinion, and the issue dragged on for months without resolution. Hooper now insisted that vestments were not indifferent, since they obscured the priesthood of Christ by encouraging hypocrisy and superstition. Warwick disagreed, emphasising that the king must be obeyed in things indifferent, and he pointed to St Paul's concessions to Jewish traditions in the early church. Finally, an acrimonious debate with Ridley went against Hooper. Ridley's position centred on maintaining order and authority; not the vestments themselves, Hooper's primary concern.

Hooper–Ridley debate

In a

In a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

letter dated 3 October 1550, Hooper laid out his argument ''contra usum vestium''. With Ridley's reply (in English), it marks the first written representation of a split in the English Reformation. Hooper's argument is that vestments should not be used as they are not indifferent, nor is their use supported by scripture, a point he takes as self-evident. He contends that church practices must either have express biblical support or be things indifferent, approval for which is implied by scripture. Furthermore, an indifferent thing, if used, causes no profit or loss. Ridley objected in his response, saying that indifferent things do have profitable effects, which is the only reason they are used. Failing to distinguish between conditions for indifferent things in general and the church's use of indifferent things, Hooper then all but excludes the possibility of anything being indifferent in the four conditions he sets:

:1) An indifferent thing has either an express justification in scripture or is implied by it, finding its origin and foundation in scripture.

Hooper cites Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

14:23 (whatever is not faith is sin), Romans 10:17 (faith comes from hearing the word of God), and Matthew 15:13 (everything not "planted" by God will be "rooted up") to argue that indifferent things must be done in faith, and since what cannot be proved from scripture is not of faith, indifferent things must be proved from scripture, which is both necessary and sufficient authority, as opposed to tradition. Hooper maintains that priestly garb distinguishing clergy from laity is not indicated by scripture; there is no mention of it in the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

as being in use in the early church, and the use of priestly clothing in the Old Testament is a Hebrew practice, a type or foreshadowing that finds its antitype in Christ, who abolishes the old order and recognises the spiritual equality, or priesthood, of all Christians. The historicity of these claims is further supported by Hooper with a reference to Polydore Vergil

Polydore Vergil or Virgil (Italian: ''Polidoro Virgili''; commonly Latinised as ''Polydorus Vergilius''; – 18 April 1555), widely known as Polydore Vergil of Urbino, was an Italian humanist scholar, historian, priest and diplomat, who spent ...

's ''De Inventoribus Rerum''.

In response, Ridley rejected Hooper's insistence on biblical origins and countered Hooper's interpretations of his chosen biblical texts. He points out that many non-controversial practices are not mentioned or implied in scripture. Ridley denies that early church practices are normative for the present situation, and he links such primitivist arguments with the Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

. Joking that Hooper's reference to Christ's nakedness on the cross is as insignificant as the clothing King Herod put Christ in and "a jolly argument" for the Adamites, Ridley does not dispute Hooper's main typological argument, but neither does he accept that vestments are necessarily or exclusively identified with Israel and the Roman church. On Hooper's point about the priesthood of all believers, Ridley says it does not follow from this doctrine that all Christians must wear the same clothes.

:2) An indifferent thing must be left to individual discretion; if required, it is no longer indifferent.

For Ridley, on matters of indifference, one must defer conscience to the authorities of the church, or else "thou showest thyself a disordered person, disobedient, as contemner of lawful authority, and a wounder of thy weak brother his conscience." For him, the debate was finally about legitimate authority, not the merits and demerits of vestments themselves. He contended that it is only accidental that the compulsory ceases to be indifferent; the degeneration of a practice into non-indifference can be corrected without throwing out the practice. Things are not, "because they have been abused, to be taken away, but to be reformed and amended, and so kept still."

:3) An indifferent thing's usefulness must be demonstrated and not introduced arbitrarily.

For this point, Hooper cites 1 Corinthians 14 and 2 Corinthians 13. As it contradicts the first point above, Primus contends that Hooper must now refer to indifferent things in the church and earlier meant indifferent things in general, in the abstract. Regardless, the apparent contradiction was seized by Ridley and undoubtedly hurt Hooper's case with the council.

:4) Indifferent things must be introduced into the church with apostolic and evangelical lenity, not violent tyranny.

In making such an inflammatory, risky statement (he later may have called his opponents "papists" in a part of his argument that is lost), Hooper may not have been suggesting England was tyrannical but that Rome was—and that England could become like Rome. Ridley warned Hooper of the implications of an attack on English ecclesiastical and civil authority and of the consequences of radical individual liberties, while also reminding him that it was Parliament that established the "Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

in the church of England".

In closing, Hooper asks that the dispute be resolved by church authorities without looking to civil authorities for support—although the monarch was the head of both the church and the state. This hint of a plea for a separation of church and state would later be elaborated by Thomas Cartwright, but for Hooper, although the word of God was the highest authority, the state could still impose upon men's consciences (such as requiring them not to be Roman Catholic) when it had a biblical warrant. Moreover, Hooper himself addressed the civil magistrates, suggesting that the clergy supporting vestments were a threat to the state, and he declared his willingness to be martyred for his cause. Ridley, by contrast, responds with humour, calling this "a magnifical promise set forth with a stout style". He invites Hooper to agree that vestments are indifferent, not to condemn them as sinful, and then he will ordain him even if he wears street clothes to the ceremony.

Outcome of the controversy

The weaknesses in Hooper's argument, Ridley's laconic and temperate rejoinder, and Ridley's offer of a compromise no doubt turned the council against Hooper's inflexible convictions when he did not accept it. Heinrich Bullinger, Pietro Martire Vermigli, and Martin Bucer, while agreeing with Hooper's views, ceased to support him for the pragmatic sake of unity and slower reform. Only Jan Laski remained a constant ally. Some time in mid-December 1550, Hooper was put under house arrest, during which time he wrote and published ''A godly Confession and protestation of the Christian faith''. Because of this publication, his persistent nonconformism, and violations of the terms of his house arrest, Hooper was placed in Thomas Cranmer's custody at Lambeth Palace for two weeks by the Privy Council on 13 January 1551. Hooper was then sent to Fleet Prison by the council, who made that decision on 27 January. On 15 February, Hooper submitted to consecration in vestments in a letter to Cranmer. He was consecrated Bishop of Gloucester on 8 March 1551, and shortly thereafter, preached before the king in vestments.Downfall (1553–5)

On 2 February 1553 Cranmer was ordered to appoint John Knox, a Scot, as vicar of All Hallows, Bread Street in London, placing him under the authority of Ridley. Knox returned to London in order to deliver a sermon before the king and the court during Lent, after which he refused to take his assigned post. That same year, Ridley pleaded with

On 2 February 1553 Cranmer was ordered to appoint John Knox, a Scot, as vicar of All Hallows, Bread Street in London, placing him under the authority of Ridley. Knox returned to London in order to deliver a sermon before the king and the court during Lent, after which he refused to take his assigned post. That same year, Ridley pleaded with Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

to give some of his empty palaces over to the city to house homeless women and children. One such foundation was Bridewell Royal Hospital

The Bridewell and Bethlehem Hospitals were two charitable foundations that were independently put into the charge of the City of London. They were brought under joint administration in 1557.

Bethlehem Hospital

The Bethlem Royal Hospital was found ...

, which is today known as King Edward's School, Witley

King Edward's Witley is an independent co-educational boarding and day school, founded in 1553 by King Edward VI and Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London and Westminster. The School is located in the village of Wormley (near Witley), Surrey, Engl ...

.

Edward VI became seriously ill from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

and in mid-June the councillors were told that he did not have long to live. They set to work to convince several judges to put on the throne Lady Jane Grey, Edward's cousin, instead of Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon and a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

. On 17 June 1553 the king made his will noting Jane would succeed him, contravening the Third Succession Act

The Third Succession Act of King Henry VIII's reign, passed by the Parliament of England in July 1543, returned his daughters Mary and Elizabeth to the line of the succession behind their half-brother Edward. Born in 1537, Edward was the son o ...

.

Ridley signed the letters patent giving the English throne to Lady Jane Grey. On 9 July 1553 he preached a sermon at St Paul's cross in which he affirmed that the princesses Mary and Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

were bastards. By mid-July, there were serious provincial revolts in Mary's favour and support for Jane in the council fell. As Mary was proclaimed queen, Ridley, Jane's father, the Duke of Suffolk

Duke of Suffolk is a title that has been created three times in the peerage of England.

The dukedom was first created for William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, William de la Pole, who had already been elevated to the ranks of earl and marquess ...

and others were imprisoned. Ridley was sent to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

.

Through February 1554 Jane and her leading supporters were executed. After that, there was time to deal with the religious leaders of the English Reformation and so on 8 March 1554 the Privy Council ordered Cranmer, Ridley, and Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer ( – 16 October 1555) was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, and Bishop of Worcester during the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555 under the Catholic Queen Mary I he was burned at the ...

to be transferred to Bocardo prison in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

to await trial for heresy. The trial of Latimer and Ridley started shortly after Cranmer's with John Jewel

John Jewel (''alias'' Jewell) (24 May 1522 – 23 September 1571) of Devon, England was Bishop of Salisbury from 1559 to 1571.

Life

He was the youngest son of John Jewel of Bowden in the parish of Berry Narbor in Devon, by his wife Alice Bel ...

acting as notary to Ridley. Their verdicts came almost immediately: they were to be burned at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

.

Death and legacy

The sentence was carried out on 16 October 1555 in Oxford. Cranmer was taken to a tower to watch the proceedings. Ridley burned extremely slowly and suffered a great deal: his brother-in-law had put more tinder on the pyre in order to speed his death, but this only caused his lower parts to burn. Latimer is supposed to have said to Ridley, "Be of good comfort, and play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God's grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out." This was quoted in ''

The sentence was carried out on 16 October 1555 in Oxford. Cranmer was taken to a tower to watch the proceedings. Ridley burned extremely slowly and suffered a great deal: his brother-in-law had put more tinder on the pyre in order to speed his death, but this only caused his lower parts to burn. Latimer is supposed to have said to Ridley, "Be of good comfort, and play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God's grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out." This was quoted in ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs

The ''Actes and Monuments'' (full title: ''Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church''), popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Protestant history and martyrology by Protestant Engli ...

''.

A metal cross in a cobbled patch of road in Broad Street, Oxford

Broad Street is a wide street in central Oxford, England, just north of the former city wall.

The street is known for its bookshops, including the original Blackwell's bookshop at number 50, located here due to the University of Oxford. Among res ...

, marks the site. Eventually Ridley and Latimer were seen as martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

s for their support of a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

independent from the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Along with Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry ...

, they are known as the Oxford Martyrs.

In the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, his death was commemorated by the Martyrs' Memorial

The Martyrs' Memorial is a stone monument positioned at the intersection of St Giles', Magdalen Street and Beaumont Street, to the west of Balliol College, Oxford, England. It commemorates the 16th-century Oxford Martyrs.

History

The monu ...

, located near the site of his execution. As well as being a monument to the English Reformation and the doctrines of the Protestant and Reformed doctrines, the memorial is a landmark of the 19th century, a monument stoutly resisted by John Keble

John Keble (25 April 1792 – 29 March 1866) was an English Anglican priest and poet who was one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement. Keble College, Oxford, was named after him.

Early life

Keble was born on 25 April 1792 in Fairford, Glouce ...

, John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

and others of the Tractarian Movement and Oxford Movement. Profoundly alarmed at the Romewardizing intrusions and efforts at realignment that the movement was attempting to bring into the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, Protestant and Reformed Anglican clergymen raised the funds for erecting the monument, with its highly anti-Roman Catholic inscription, a memorial to over three hundred years of history and reformation. As a result, the monument was built 300 years after the events it commemorates.

In 1881, Ridley Hall in

In 1881, Ridley Hall in Cambridge, England

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge became ...

, was founded in his memory for the training of Anglican priests. Ridley College, a private University-preparatory school

A college-preparatory school (usually shortened to preparatory school or prep school) is a type of secondary school. The term refers to public, private independent or parochial schools primarily designed to prepare students for higher educatio ...

located in St. Catharines, Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

, Canada, was founded in his honour in 1889. Also named after him is Ridley Melbourne, a theological college

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

in Australia, founded in 1910. There is a Church of England church dedicated to him in Welling, southeast London. The words spoken to Ridley by Latimer at their execution are used. Ridley and Latimer are remembered with a commemoration

Commemoration may refer to:

*Commemoration (Anglicanism), a religious observance in Churches of the Anglican Communion

*Commemoration (liturgy)

In the Latin liturgical rites of the Catholic Church, a commemoration is the recital, within the Li ...

in the Calendar of saints

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context d ...

in some parts of the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

on 16 October.

See also

*Saints in Anglicanism

The word ''saint'' derives from the Latin ''sanctus'', meaning holy, and has long been used in Christianity to refer to a person who was recognized as having lived a holy life and as being an exemplar and model for other Christians. Beginning i ...

Notes

References

*. * *. * *. *. *. *.External links

Keeping the Faith

(

BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

), documentary on his story by the historian Jane Ridley

Jane Ridley (born 15 May 1953) is an English historian, biographer, author and broadcaster, and Professor of Modern History at the University of Buckingham.

Ridley won the Duff Cooper Prize in 2002 for ''The Architect and his Wife'', a biograph ...

, a descendant.

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ridley, Nicholas

Bishops of London

Bishops of Rochester

English Anglican theologians

Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge

Christianity in Oxford

Executed people from Northumberland

People executed under Mary I of England

University of Paris alumni

People executed for heresy

Executed British people

People educated at the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle upon Tyne

16th-century Protestant martyrs

Christ's Hospital

Anglican saints

Canons of Westminster

16th-century English clergy

1500s births

1555 deaths

Year of birth uncertain

People executed by the Kingdom of England by burning

Masters of Pembroke College, Cambridge

Protestant martyrs of England

16th-century Anglican theologians

15th-century Anglican theologians