Nicholai Miklukho-Maklai on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

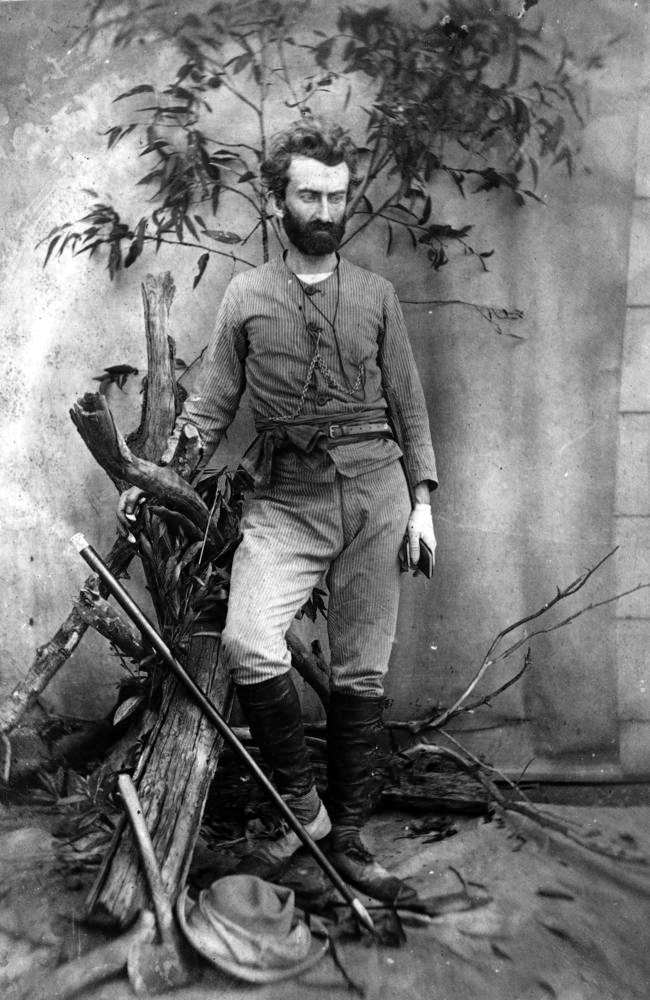

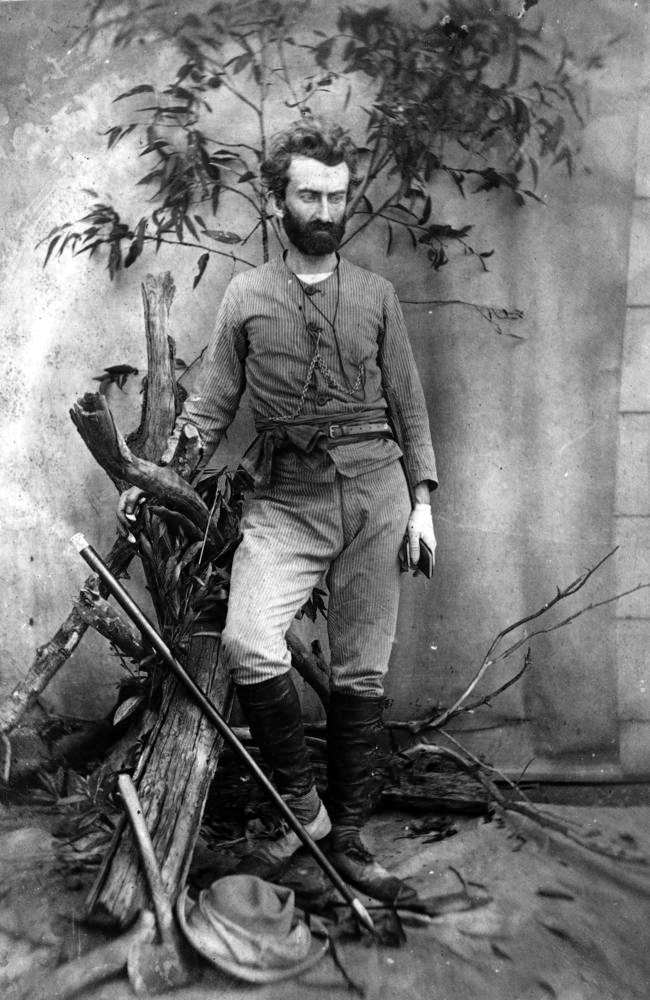

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay (russian: Никола́й Никола́евич Миклу́хо-Макла́й; 1846 – 1888) was a

''Australian Aboriginal Studies'', Vol. 1998, 1998 He became a prominent figure of nineteenth-century Australian science and became involved in significant issues of Australian and New Guinea history. Writing letters to Australian papers, Miklouho-Maclay expressed his opposition to the labour and slave trade ("

in the ''Journal of Polynesian Studies'', Volume 95, No. 4, 1986 p 537-542 While in Australia, he built the first biological

Film

His paternal grandparents were friends of Gogol's. About his origins, Miklouho-Maclay wrote:

In 1858 Nicholas enrolled into the third grade of a German Lutheran school at the Saint Anna Kirche in Saint Petersburg. During his studies at the Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium (1859–1863) along with his brother Sergei, he was arrested and kept for several days in the

In 1858 Nicholas enrolled into the third grade of a German Lutheran school at the Saint Anna Kirche in Saint Petersburg. During his studies at the Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium (1859–1863) along with his brother Sergei, he was arrested and kept for several days in the

Miklouho-Maclay left St Petersburg for Australia on the

Miklouho-Maclay left St Petersburg for Australia on the

February 2007 ver.1, p.3 and in the

Miklouho-Maclay street, Moscow

on Google Maps named in his honour. The district museum in Okulovka,

Partial view

on

Miklouho-Maclay’s Legacy in Russian-and English-Language Academic Research, 1992–2017.

Maclay Coast, Papua New Guinea

on Google Maps.

Paper in the ''Proceedings of the Linnean Society of NSW'' by N. Miklouho-Maclay

vol. 8, 1883

''Mikloucho-Maclay: New Guinea Diaries 1871—1883'', translated from the Russian with biographical and historical notes by C. L. Sentinella. Kristen Press, Madang, Papua New Guinea

{{DEFAULTSORT:Miklouho-Maclay, Nicholas 1846 births 1888 deaths People from Okulovsky District People from Borovichsky Uyezd Zaporozhian Cossack nobility People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent People from the Russian Empire of German descent Explorers from the Russian Empire Explorers of Asia Explorers of New Guinea Anthropologists from the Russian Empire Ethnologists from the Russian Empire Marine biologists from the Russian Empire Expatriates from the Russian Empire in Austria-Hungary Expatriates from the Russian Empire in Australia Deaths from brain tumor

Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

Imperial explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

. He worked as an ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropolog ...

, anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms an ...

and biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually specialize ...

who became famous as one of the earliest scientists to settle among and study indigenous people of New Guinea

The indigenous peoples of West Papua in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, commonly called Papuans, are Melanesians. There is genetic evidence for two major historical lineages in New Guinea and neighboring islands: a first wave from the Malay Arch ...

who had never seen a European.Webster, E. M. (1984). ''The Moon Man: A Biography of Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay''. University of California Press, Berkeley. 421 pages.

Miklouho-Maclay spent the major part of his life travelling and conducted scientific research in the Middle East, Australia, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

, Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, V ...

and Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

. Australia became his adopted country and Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

the hometown of his family.Wongar, B., Commentary and Translator's Note in Miklouho-Maclay, N. N. ''The New Guinea Diaries 1871-1183'', translated by B. Wonger, Dingo Books, Victoria, Australia Shnukal, A. (1998), 'N. N. Miklouho-Maclay in Torres Strait'''Australian Aboriginal Studies'', Vol. 1998, 1998 He became a prominent figure of nineteenth-century Australian science and became involved in significant issues of Australian and New Guinea history. Writing letters to Australian papers, Miklouho-Maclay expressed his opposition to the labour and slave trade ("

blackbirding

Blackbirding involves the coercion of people through deception or kidnapping to work as slaves or poorly paid labourers in countries distant from their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people in ...

") in Australia, New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

and the Pacific, as well as his opposition to the British and German colonial expansion in New Guinea.Peter Lawrence, review of the "Moon Man" by Webster, E.in the ''Journal of Polynesian Studies'', Volume 95, No. 4, 1986 p 537-542 While in Australia, he built the first biological

research station

Research stations are facilities where scientific investigation, collection, analysis and experimentation occurs. A research station is a facility that is built for the purpose of conducting scientific research. There are also many types of resea ...

in the Southern Hemisphere, was elected to the Linnean Society of New South Wales

The Linnean Society of New South Wales promotes ''the Cultivation and Study of the Science of Natural History in all its Branches'' and was founded in Sydney, New South Wales (Australia) in 1874 and incorporated in 1884.

History

The Society succe ...

, was instrumental in establishing the Australasian Biological Association, stayed at the elite Australian Club

The Australian Club is a private club founded in 1838 and located in Sydney at 165 Macquarie Street. Its membership is men-only and it is the oldest gentlemen's club in the southern hemisphere.

"The Club provides excellent dining facilities, ...

, became the intimate of the leading amateur scientist and political figure Sir William Macleay, and married Margaret-Emma Robertson, the daughter of the Premier of New South Wales

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster Parliamentary System, with a Parliament of New South Wales acting as the legislatur ...

. His three grandsons have all contributed to the public life of Australia.

One of the earliest followers of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, Miklouho-Maclay is also remembered today as a scholar who, on the basis of his comparative anatomical research, was one of the first anthropologists to refute the prevailing view that the different races of mankind belonged to different species.

Ancestry and early years

Miklouho-Maclay was born in a temporary workers' camp in Borovichi county (uyezd),Novgorod Governorate

Novgorod Governorate (Pre-reformed rus, Новгоро́дская губе́рнія, r=Novgorodskaya guberniya, p=ˈnofɡərətskəjə ɡʊˈbʲernʲɪjə, t=Government of Novgorod), was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Ru ...

(currently Okulovsky District

Okulovsky District (russian: Оку́ловский райо́н) is an administrativeLaw #559-OZ and municipalLaw #355-OZ district (raion), one of the twenty-one in Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is located in the center of the oblast and borders w ...

of Novgorod Oblast

Novgorod Oblast (russian: Новгоро́дская о́бласть, ''Novgorodskaya oblast'') is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is the city of Veliky Novgorod. Some of the oldest Russian cities, includin ...

) in Russia, a son of a civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

working on the construction of the Moscow-St. Petersburg Railway. Miklouho-Maclay was partly of Ukrainian Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

descent. His Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

father, Nikolai Ilyich Myklukha, was born in 1818, in Starodub

Starodub ( rus, links=no, Староду́б, p=stərɐˈdup, ''old oak'') is a town in Bryansk Oblast, Russia, on the Babinets River (the Dnieper basin), southwest of Bryansk. Population: 16,000 (1975).

History

Starodub has been known ...

, Chernigov Governorate

The Chernigov Governorate (russian: Черниговская губерния; translit.: ''Chernigovskaya guberniya''; ), also known as the Government of Chernigov, was a guberniya in the historical Left-bank Ukraine region of the Russian ...

, and descended from Stepan Myklukha, a Zaporozhian Cossack

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

who was awarded the title of noble of the Empire by Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

for his military exploits during the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 involved an unsuccessful attempt by the Ottoman Empire to regain lands lost to the Russian Empire in the course of the previous Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774). It took place concomitantly with the Austro ...

,Thomassen, E. S. (1882), ''A Biographical Sketch of Nicholas de Miklouho Maclay the Explorer'', Brisbane. Document held in the State Library of New South Wales

The State Library of New South Wales, part of which is known as the Mitchell Library, is a large heritage-listed special collections, reference and research library open to the public and is one of the oldest libraries in Australia. Establis ...

which included the capture of the Ochakov

Ochakiv, also known as Ochakov ( uk, Оча́ків, ; russian: Очаков; crh, Özü; ro, Oceacov and ''Vozia'', and Alektor ( in Greek), is a small city in Mykolaiv Raion, Mykolaiv Oblast (region) of southern Ukraine. It hosts the adminis ...

fortress. In fact, his Cossack lineage was extensive and also included the Otaman of Zaporizhian Host Okhrim Myklukha, who later became the prototype of Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

's main character Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (russian: «Тарас Бульба»; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons And ...

.'' Dubno Castle''. Dir. Olha Krainyk. Perf. Mykola Tomenko

Mykola Volodymyrovych Tomenko ( uk, Микола Володимирович Томенко) (born December 11, 1964) is a Ukrainian politician. He has been a member of Ukraine's parliament, the Verkhovna Rada from 2006 until 2016.

. TVi: Seven Wonders of Ukraine

The Seven Wonders of Ukraine ( uk, Сім чудес України ) are the seven historical and cultural monuments of Ukraine, which were chosen in the ''Seven Wonders of Ukraine'' contest held in July, 2007. This was the first public contest ...

, 2011Film

His paternal grandparents were friends of Gogol's. About his origins, Miklouho-Maclay wrote:

My ancestors came originally from theNicholas' father, Mykola Myklukha, graduated from the Nizhyn Lyceum (Ukraine Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ..., and were Zaporogg-cossacks of theDnieper } The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an .... After the annexation of the Ukraine, Stepan, one of the family, served assotnik Sotnik or sotnyk (, uk, сотник, bg, стотник) was a military rank among the Cossack '' starshyna'' (military officers), Strelets Troops (17th century) in Muscovy and Imperial Cossack cavalry (since 1826), the Ukrainian Insurgent A ...(a superior Cossack officer) under General Count Rumianzoff, and having distinguished himself at the storming of the Turkish fortress of Otshakoff, was by the order ofCatherine II , en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes , house = , father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst , mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp , birth_date = , birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...made a noble...

Nizhyn

Nizhyn ( uk, Ні́жин, Nizhyn, ) is a city located in Chernihiv Oblast of northern Ukraine along the Oster River. The city is located north-east of the national capital Kyiv. Nizhyn serves as the administrative center of Nizhyn Raion. It ...

), after which he walked all the way to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, where he enrolled in the Roadway Institute of Engineering Corps. He graduated from the institute in 1840 and became an engineer assigned to work on the construction of the Moscow–Saint Petersburg Railway. After becoming the first chief of the Moskovsky passenger railway station in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Myklukha moved his family there. He died in December 1857 from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

and was survived by his wife and five children. Before his death, Myklukha was fired from his job for sending 150 rubles to Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

.

Nicholas' mother, Ekaterina Semenovna, née Bekker, was of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Polish descent (her three brothers took part in the January Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

of 1863). After 1873, the Miklouho-Maclay family purchased and lived in a country estate in Malyn

Malyn ( uk, Ма́лин, Mályn) (sometimes spelled Malin) is a city in Zhytomyr Oblast (province) of Ukraine located about northwest of Kyiv. It served as the administrative center of Malyn Raion, now located in Korosten Raion. Population:

...

, northwest of Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

in the Polesia

Polesia, Polesie, or Polesye, uk, Полісся (Polissia), pl, Polesie, russian: Полесье (Polesye) is a natural and historical region that starts from the farthest edge of Central Europe and encompasses Eastern Europe, including East ...

region.

One of Nicholas' brothers, Sergei, became a judge in Malyn where he eventually died. Another brother, Mikhail, became a geologist. A third brother, Vladimir

Vladimir may refer to:

Names

* Vladimir (name) for the Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Macedonian, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak and Slovenian spellings of a Slavic name

* Uladzimir for the Belarusian version of the name

* Volodymyr for the Ukr ...

, was a captain of the Russian coast defense ship Admiral Ushakov and participated in the Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (Japanese:対馬沖海戦, Tsushimaoki''-Kaisen'', russian: Цусимское сражение, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known as the Battle of Tsushima Strait and the Naval Battle of Sea of Japan (Japanese: 日 ...

where he perished. Both Mikhail and Vladimir were members of the Russian revolutionary organization Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya ( rus, Наро́дная во́ля, p=nɐˈrodnəjə ˈvolʲə, t=People's Will) was a late 19th-century revolutionary political organization in the Russian Empire which conducted assassinations of government officials in an att ...

.

Nicholas was baptised on 21 July 1846 by priest Ioann Smirnov at the Shegrinskaya Church of Nikolaos the Wonderworker. His godfather was Nicholas Ridiger, a Borovichi landowner who was a veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign, the Second Polish War, the Army of Twenty nations, and the Patriotic War of 1812 was launched by Napoleon Bonaparte to force the Russian Empire back into the continental blo ...

and a participant in the Battle of Borodino

The Battle of Borodino (). took place near the village of Borodino on during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. The ' won the battle against the Imperial Russian Army but failed to gain a decisive victory and suffered tremendous losses. Napole ...

.

Education and studies

In 1858 Nicholas enrolled into the third grade of a German Lutheran school at the Saint Anna Kirche in Saint Petersburg. During his studies at the Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium (1859–1863) along with his brother Sergei, he was arrested and kept for several days in the

In 1858 Nicholas enrolled into the third grade of a German Lutheran school at the Saint Anna Kirche in Saint Petersburg. During his studies at the Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium (1859–1863) along with his brother Sergei, he was arrested and kept for several days in the Peter and Paul Fortress

The Peter and Paul Fortress is the original citadel of St. Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740 as a star fortress. Between the first half of the 1700s and early 1920 ...

for participating in student protests. The young students were saved by the Russian writer Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy

Count Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (russian: Граф Алексе́й Константи́нович Толсто́й; – ), often referred to as A. K. Tolstoy, was a Russian poet, novelist, and playwright. He is considered to be the most ...

who was a friend of Nicholas' father. In 1863, without finishing the gymnasium, Nicholas enrolled as a free listener at the St. Petersburg University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBU; russian: Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter t ...

but only spent two months there before being expelled in February 1864 and debarred from tertiary education in Imperial Russia for "breaking the rules

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Education

* Royal University of Law and Economics (RULE), a university in Cambodia

Human activity

* The exercise of political or personal control by someone with authority or power

* Business rule, a rule pert ...

". In March of the same year, with a forged passport, he moved abroad to complete his studies in German universities, which provided an opportunity to study and work with leading European scientists. He studied humanities at Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German: ') is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914, of which roughly a quarter consisted of students ...

, medicine at Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, and zoology at the University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The ...

, where he came under the influence of the great German scholar Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new s ...

, who had a profound influence on his future.

Miklouho-Maclay's brilliant student records attracted the attention of Haeckel, who made him his assistant as part of a field expedition to the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

in 1866. There, Miklouho-Maclay took an interest in sharks and sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throu ...

s and discovered a new sponge species, which he named '' Guancha blanca'', in tribute to the Guanches

The Guanches were the indigenous inhabitants of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean some west of Africa.

It is believed that they may have arrived on the archipelago some time in the first millennium BCE. The Guanches were the only nativ ...

, the original Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

inhabitants of the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

. He also became a close friend of the biologist Anton Dohrn

Felix Anton Dohrn FRS FRSE (29 December 1840 – 26 September 1909) was a prominent German Darwinist and the founder and first director of the first zoological research station in the world, the Stazione Zoologica in Naples, Italy. He worked ...

, with whom he helped conceive the idea of research station

Research stations are facilities where scientific investigation, collection, analysis and experimentation occurs. A research station is a facility that is built for the purpose of conducting scientific research. There are also many types of resea ...

s while staying with him at Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

, Italy.

Australia

Miklouho-Maclay left St Petersburg for Australia on the

Miklouho-Maclay left St Petersburg for Australia on the steam corvette

Steam frigates (including screw frigates) and the smaller steam corvettes, steam sloops, steam gunboats and steam schooners, were steam-powered warships that were not meant to stand in the line of battle. There were some exceptions like for exam ...

'' Vityaz''. He arrived in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

on 18 July 1878. A few days after arriving, he approached the Linnean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature colle ...

and offered to organise a zoological centre. In September 1878 his offer was approved. The centre, known as the ''Marine Biological Station'', was constructed by prominent Sydney architect, John Kirkpatrick. This facility, located in Watsons Bay

Watsons Bay is a harbourside, eastern suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Watsons Bay is located 11 km north-east of the Sydney central business district, in the local government area of the Municipality of Woollahra. ...

on the east side of Greater Sydney, was the first marine biological research institute in Australia. He married Margaret-Emma, widowed daughter of the Premier of New South Wales

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster Parliamentary System, with a Parliament of New South Wales acting as the legislatur ...

, John Robertson. His residence is in the Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

suburb of Birchgrove, ''Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

'' is now heritage-listed due to its association with him.

Anthropological work in New Guinea and the Pacific

Miklouho-Maclay lived in northeasternNew Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

for a two-year period in between 1871 and 1880, from which he also visited the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Malay Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula ( Malay: ''Semenanjung Tanah Melayu'') is a peninsula in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The ar ...

and Australia on a number of occasions. He returned to New Guinea again in 1883. Living amongst the native tribes, his comprehensive treatise on their way of life and customs was invaluable to later researchers.

Anthropological views

In scientific and anthropological circles during the 1850s and 1860s there was much discussion connected with the study ofhuman races

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

and the interpretation of racial peculiarities. There were some anthropologists, such as Samuel Morton

Samuel Jules "Nails" Morton (July 3, 1893 – May 13, 1923) was a soldier during World War I and later a high-ranking member of Dean O'Banion's Northside gang.

Biography

Early life

Born in New York City, Morton grew up in Chicago in the Jewi ...

, who tried to prove that not all human races were of equal worth, and that "white people

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

" were predestined by "natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

" to rule over the "coloured

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

" races.Turmarkin, D. "Miklouho-Maclay" in ''Rain'', the journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 51 (Aug., 1982), pp. 4-7

Some scientists, such as Ernst Haeckel, a teacher of the young Miklouho-Maclay, relegated what they regarded as culturally "backward" people like Papuans

The indigenous peoples of West Papua in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, commonly called Papuans, are Melanesians. There is genetic evidence for two major historical lineages in New Guinea and neighboring islands: a first wave from the Malay Arch ...

, Bushmen

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are members of various Khoe languages, Khoe, Tuu languages, Tuu, or Kxʼa languages, Kxʼa-speaking indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures that are the Indigenous peoples of Africa, first cultures of Sout ...

and others to the role of ' intermediate links' between Europeans and their animal ancestors. While adhering to Darwin's theory of evolution

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

, Miklouho-Maclay diverged from these concepts, and it was this question that led him to gather scientific facts and to study the dark-skinned inhabitants of New Guinea. On the basis of his comparative anatomical research, Miklouho-Maclay was one of the first anthropologists to refute polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

, the view that the different races of mankind belonged to different species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

.

Opposition to slavery

The humanist views of Miklouho-Maclay led him to campaign actively against theslave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and against blackbirding

Blackbirding involves the coercion of people through deception or kidnapping to work as slaves or poorly paid labourers in countries distant from their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people in ...

– carried on between the islands of Melanesia and plantations in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

, Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

, Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

and New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

. In November 1878 the Dutch government informed him that on his recommendations it was checking the slave traffic at Ternate

Ternate is a city in the Indonesian province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands. It was the ''de facto'' provincial capital of North Maluku before Sofifi on the nearby coast of Halmahera became the capital in 2010. It is off the ...

and Tidore

Tidore ( id, Kota Tidore Kepulauan, lit. "City of Tidore Islands") is a city, island, and archipelago in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, west of the larger island of Halmahera. Part of North Maluku Province, the city includes the island ...

. From 1879 onwards he wrote a number of letters to Australian papers, and corresponded with Sir Arthur Gordon, High Commissioner for the Western Pacific, on protecting the land rights

Land law is the form of law that deals with the rights to use, alienate, or exclude others from land. In many jurisdictions, these kinds of property are referred to as real estate or real property, as distinct from personal property. Land use a ...

of his friends on the Maclay Coast of north-eastern New Guinea, and on ending the traffic in arms and intoxicants in the South Pacific.

Ill health and death in Russia

In 1887 he left Australia, returned to St Petersburg to present his work to the ImperialRussian Geographical Society

The Russian Geographical Society (russian: Ру́сское географи́ческое о́бщество «РГО»), or RGO, is a learned society based in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It promotes geography, exploration and nature protection wi ...

and took his young family with him. Miklouho-Maclay was in poor health and, despite treatment from Sergei Botkin

Sergey Petrovich Botkin (russian: Серге́й Петро́вич Бо́ткин; 5 September 1832 – 12 December 1889) was a famous Russian clinician, therapist, and activist, one of the founders of modern Russian medical science and educati ...

, Miklouho-Maclay died of an undiagnosed brain tumour

A brain tumor occurs when abnormal cells form within the brain. There are two main types of tumors: malignant tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors. These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and second ...

at 41 in St Petersburg. He was buried in the Volkovo Cemetery

The Volkovo Cemetery (also Volkovskoe) (russian: Во́лковское кла́дбище or Во́лково кла́дбище) is one of the largest and oldest non- Orthodox cemeteries in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Until the early 20th century i ...

and left his skull to the St Petersburg Military and Medical Academy.

Post-death

Miklouho-Maclay's widow returned to Sydney with their children. Until 1917 the scientist's family received an imperial Russian pension. The money was first allocated by Alexander III and then byNicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pol ...

. One of his sons, Alexander, married a daughter of R. E. O'Connor. His travel journals were not published until 1923, and an annotated five-volume collection of his works was published in 1953.

Commemoration

Internationally and in Science

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay is commemorated in thescientific name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bo ...

of the New Guinea tree species ''Pouteria maclayana

''Pouteria maclayana'' is a tree in the family Sapotaceae. It grows up to tall with a trunk diameter of up to . The fruits are roundish, up to long. The tree is named for Russian explorer and biologist Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay. Its habitat is ...

'', in the banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", disting ...

species ''Musa maclayi

''Musa maclayi'' is a species of seeded banana native to Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. It is placed in section ''Callimusa'' (now including the former section ''Australimusa''). It is regarded as one of the progenitors of the Fe'i ba ...

'',Ploetz, R. ''et al'' "Banana and plantain—an overview with emphasis on Pacific island cultivars", Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry (www.traditionaltree.org)February 2007 ver.1, p.3 and in the

land snail

A land snail is any of the numerous species of snail that live on land, as opposed to the sea snails and freshwater snails. ''Land snail'' is the common name for terrestrial gastropod mollusks that have shells (those without shells are known ...

species ''Canefriula maclayiana'' which were some of the species he discovered. The weevil ''Rhinoscapha maclayi'' was first collected by Miklouho-Maclay and was then named after him by his friend William Macleay.

Other species named after Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay include: '' Colastomion maclayi'' (a wasp from New Guinea), and ''Dysmicoccus maclayi'' (a scale insect from New Guinea)

The asteroid 3196 Maklaj, discovered in 1978, was named in his honour.

Maklaj is the basis of the main character in the Esperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international communic ...

historical novel "Sed Nur Fragmento" by Trevor Steele.

Australia

The Marine Biological Station in Watson's Bay, built and used by Miklouho-Maclay, was commandeered by the Ministry of Defence in 1899 as abarracks

Barracks are usually a group of long buildings built to house military personnel or laborers. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word "barraca" ("soldier's tent"), but today barracks are u ...

for officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," f ...

s. In the 1980s the Miklouho-Maclay Society unsuccessfully lobbied for the centre to be made into a historical landmark in memory of Miklouho-Maclay's scientific work. Today, although owned by the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust

The Sydney Harbour Federation Trust ("Harbour Trust") is an Australian Government agency established in 2001 to preserve and rehabilitate a number of defence and other Commonwealth lands in and around Sydney Harbour. The Trust has been focused ...

, the building is used as a private residence and is only open to the public on special occasions.

The Miklouho-Maclay Society succeeded in naming a park in his honour in Snails Bay ( Birchgrove), not far from a house where he lived in Sydney for a time.

A bust of Miklouho-Maclay was unveiled in front of the Macleay Museum

The Macleay Museum at The University of Sydney, was a natural history museum located on the University's campus, in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The Museum was amalgamanted into Chau Chak Wing Museum, which opened in 2020.

The Macleay M ...

at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

to commemorate the 150th anniversary of his birth. The ''Macleay Miklouho-Maclay Fellowship'' is available from the University of Sydney each year.

Indonesia

A monument to Miklouho-Maclay was unveiled inJakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, on 3 March 2011.

Papua New Guinea

The term ''Maclay Coast'' has from time to time been used to refer the North-east coast ofPapua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

. Miklouho-Maclay began using the term, defining it as extending for 150 miles between Cape Croisilles

Cape Croisilles is a cape in Madang Province, Papua New Guinea. Cape Croisillesin Geonames.org (cc-by) post updated 2014-09-06; database downloaded 2015-06-22 The Croisilles languages are named after the cape.

See also

*Croisilles languages

T ...

and Cape King William, and 30–50 miles inland to the mountains of Mana-Boro-Boro ( Finisterre Mountains). However, this name is not in use today. The section of the coast from Cape Croisilles to Madang is referred to as part of the North Coast, the bay in which Madang is situated in called Astrolabe Bay

Astrolabe Bay is a large body of water off the south coast of Madang Province, Papua New Guinea, located at . It is a part of the Bismarck Sea and stretches from the Cape Iris in the south to the Cape Croisilles to the north. It was discovered ...

, while the coast from Astrolabe Bay

Astrolabe Bay is a large body of water off the south coast of Madang Province, Papua New Guinea, located at . It is a part of the Bismarck Sea and stretches from the Cape Iris in the south to the Cape Croisilles to the north. It was discovered ...

to Saidor

Saidor is a village located in Saidor ward of Rai Coast Rural LLG, Madang Province, on the north coast of Papua New Guinea.

It is also the administrative centre of the Rai Coast District of Madang Province in Papua New Guinea. The village was the ...

is the Rai Coast, which in turn gives its name to Rai Coast District

Rai Coast District is a district in the southeast of Madang Province in Papua New Guinea. It is one of the six districts that of the Madang Province. The District has four local level government (LLG) areas namely; Astrolabe Bay, Nahu Rawa, (Nanki ...

, an electorate returning an MP to the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea.

In Madang

Madang (old German name: ''Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen'') is the capital of Madang Province and is a town with a population of 27,420 (in 2005) on the north coast of Papua New Guinea. It was first settled by the Germans in the 19th century.

Histo ...

, Papua New Guinea – not far from where the explorer stayed in the 1870s – a street has been named after him.

In 2000 a monument was erected in New Guinea by Oleg Aliev. In 2013 a monument to celebrate the legacy of Miklouho-Maclay was erected near Bongu village in Madang Province, funded by "Valeria, Irma, and Valentina Sourin, Chief, Sir Peter Barter and volunteers from the Madang Resort and Friends of the Haus Tumbuna".

Russia

In Russia there is an Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology and a street in South-West Moscow (where thePeoples' Friendship University of Russia

The Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (russian: Российский университет дружбы народов), also known as RUDN University and, until 1992, Patrice Lumumba University in honor of the hero Patrice Lumumba, is a ...

is situated)on Google Maps

Novgorod Oblast

Novgorod Oblast (russian: Новгоро́дская о́бласть, ''Novgorodskaya oblast'') is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is the city of Veliky Novgorod. Some of the oldest Russian cities, includin ...

, is named after him.

A Khabarov class river passenger ship was named after him. Based at Khabarovsk

Khabarovsk ( rus, Хабaровск, a=Хабаровск.ogg, r=Habárovsk, p=xɐˈbarəfsk) is the largest city and the administrative centre of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia,Law #109 located from the China–Russia border, at the confluence of ...

, it was used on the Amur River

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeastern China (Inner Manchuria). The Amur proper is long ...

between the 1960s and 1990s.

Ukraine

A monument to Miklouho-Maclay is erected inMalyn

Malyn ( uk, Ма́лин, Mályn) (sometimes spelled Malin) is a city in Zhytomyr Oblast (province) of Ukraine located about northwest of Kyiv. It served as the administrative center of Malyn Raion, now located in Korosten Raion. Population:

...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, where his family owned a country estate. There is also a bust of him in Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

on the Crimean Peninsula.

Notes and references

General references

* Greenop, F. S. (1944) ''Who Travels Alone'', K.G. Murray Publishing Company, Sydney * Ogloblin, A. K. (1998) 'Commemorating N. N. Miklukho-Maclay (Recent Russian publications)', in ''Perspectives on the Bird's Head of Irian Jaya, Indonesia: Proceedings of the Conference'', pages.487–502. 1998.Partial view

on

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical ...

.

* Tutorsky, A. V., E. V. Govor, and Christopher Ballard.Miklouho-Maclay’s Legacy in Russian-and English-Language Academic Research, 1992–2017.

Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia

''Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia'' (russian: Археология, Этнография и Антропология Евразии) is a bilingual peer-reviewed academic journal covering anthropological and archaeological studie ...

47.2 (2019): 112-121.

External links

Maclay Coast, Papua New Guinea

on Google Maps.

Paper in the ''Proceedings of the Linnean Society of NSW'' by N. Miklouho-Maclay

vol. 8, 1883

''Mikloucho-Maclay: New Guinea Diaries 1871—1883'', translated from the Russian with biographical and historical notes by C. L. Sentinella. Kristen Press, Madang, Papua New Guinea

{{DEFAULTSORT:Miklouho-Maclay, Nicholas 1846 births 1888 deaths People from Okulovsky District People from Borovichsky Uyezd Zaporozhian Cossack nobility People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent People from the Russian Empire of German descent Explorers from the Russian Empire Explorers of Asia Explorers of New Guinea Anthropologists from the Russian Empire Ethnologists from the Russian Empire Marine biologists from the Russian Empire Expatriates from the Russian Empire in Austria-Hungary Expatriates from the Russian Empire in Australia Deaths from brain tumor