Niagara Movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black

, 1844-1944, by J. Clay Smith, Jr. (1885 – 1975), ''Men of mark; eminent, progressive and rising''

''Men of mark; eminent, progressive and rising''

by Rev. Wm. J. Simmons, Geo. R. Rewell & Co., Ohio, 1887, page 194. # George Frazier Miller (November 28, 1864 – May 9, 1943) — rector of St. Augustine's Episcopal Church, Brooklyn; socialist; civil rights activist # George Henry "G. H." Woodson (December 15, 1865 – July 7, 1933) — Criminal trial attorney, born to newly emancipated slaves; founder and president of both the Iowa Negro Bar Association in 1901 and — subsequent to being denied membership in the

The First Niagara Conference was originally scheduled for

The First Niagara Conference was originally scheduled for

On the subject of education, the authors declared that not only should it be free, but it should also be made compulsory. Higher education, they declared, should be governed independently of class or race, and they demanded action to be taken to improve "high school facilities." This they emphasized: "either the United States will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States." They demanded for judges to be selected independently of their race, and for convicted criminals, white or black, to be given equal punishments for their respective crimes.

In his address to the nation, W. E. B. Du Bois stated, "We are not more lawless than the white race; we remore often arrested, convicted and mobbed. We want justice, even for criminals and outlaws." He called for the abolition of the

On the subject of education, the authors declared that not only should it be free, but it should also be made compulsory. Higher education, they declared, should be governed independently of class or race, and they demanded action to be taken to improve "high school facilities." This they emphasized: "either the United States will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States." They demanded for judges to be selected independently of their race, and for convicted criminals, white or black, to be given equal punishments for their respective crimes.

In his address to the nation, W. E. B. Du Bois stated, "We are not more lawless than the white race; we remore often arrested, convicted and mobbed. We want justice, even for criminals and outlaws." He called for the abolition of the

The movement's second meeting, the first to be held on U.S. soil and arguably the movement's high point, took place at

The movement's second meeting, the first to be held on U.S. soil and arguably the movement's high point, took place at  The Movement, in conjunction with the Constitution League (which took Du Bois on as a director), began organizing legal challenges to segregationist laws in early 1907. For an organization with a limited budget, this was an expensive proposition: the single case they mounted challenging Virginia's railroad segregation law put the organization into debt.

Du Bois had sought to return to Harpers Ferry for the 1907 annual meeting, but Storer College refused to grant them permission, claiming the group's presence in 1906 had been followed by financial and political pressure from its supporters to distance itself from them. The 1907 meeting was held in Boston, with conflicting attendance reports. Du Bois claimed 800 attendees, while the Bookerite '' Washington Bee'' claimed only about 100 in attendance. The convention published an "Address to the World" in which it called on African-Americans not to vote for Republican Party candidates in the 1908 presidential election, citing President

The Movement, in conjunction with the Constitution League (which took Du Bois on as a director), began organizing legal challenges to segregationist laws in early 1907. For an organization with a limited budget, this was an expensive proposition: the single case they mounted challenging Virginia's railroad segregation law put the organization into debt.

Du Bois had sought to return to Harpers Ferry for the 1907 annual meeting, but Storer College refused to grant them permission, claiming the group's presence in 1906 had been followed by financial and political pressure from its supporters to distance itself from them. The 1907 meeting was held in Boston, with conflicting attendance reports. Du Bois claimed 800 attendees, while the Bookerite '' Washington Bee'' claimed only about 100 in attendance. The convention published an "Address to the World" in which it called on African-Americans not to vote for Republican Party candidates in the 1908 presidential election, citing President

online

* * * Jones, Angela. 2016. "Lessons from the Niagara movement: Prosopography and discursive protest." ''Sociological Focus'' 49.1 (2016): 63-8

online

* Jones, Angela. 2011. ''African American civil rights: Early activism and the Niagara Movement'' (ABC-CLIO, 2011)

details

* * * *

online

Niagara's Declaration of PrinciplesDu Bois Central. Special Collections and University Archives, W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts Amherst"The Early Black Experience", The Pan African Historical Museum (PAHMUSA)

{{Authority control Niagara Falls, Ontario NAACP African Americans' rights organizations Organizations established in 1905 Organizations disestablished in 1910 Progressive Era in the United States Civil rights organizations in the United States 1905 establishments in New York (state) Storer College

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. It was named for the "mighty current" of change the group wanted to effect and took Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Fall ...

as its symbol. The group did not meet in Niagara Falls, New York, but planned its first conference for nearby Buffalo (at the last minute, to avoid disruptions, moved across the Niagara River to Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada).

The Niagara Movement was organized to oppose racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and disenfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

. Its members felt "unmanly" the policy of accommodation and conciliation, without voting rights, promoted by Booker T. Washington.

Background

During the Reconstruction Era that followed theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, African Americans had an unprecedented level of civil freedom and civic participation. In the South, for the first time the former slaves could vote, hold public office, and contract for their labor. With the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s, their freedoms began to narrow. From 1890 to 1908, all the Southern states ratified new constitutions or laws that disenfranchised most blacks and significantly restricted their political and civil rights. All of them passed laws imposing legal racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in public facilities. These policies were entrenched after the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in 1896 ruled in ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'' that laws requiring "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

" facilities were constitutional. However, the separate facilities were often shabby, or they did not exist at all.

The most prominent African-American spokesman during the 1890s was Booker T. Washington, leader of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

's Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

. In an 1895 speech in Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

, Washington discussed what became known as the Atlanta Compromise. He believed that Southern African-Americans should not agitate for political rights (such as exercising the right to vote or having equal treatment

Equal opportunity is a state of fairness in which individuals are treated similarly, unhampered by artificial barriers, prejudices, or preferences, except when particular distinctions can be explicitly justified. The intent is that the important ...

under the law) as long as they were provided economic opportunities and basic rights of due process. He believed they needed to focus on education and work, to raise their race. Washington politically dominated the National Afro-American Council, the first nationwide African-American civil rights organization.

By the turn of the 20th century, other activists within the African-American community began demanding a challenge to racist government policies and higher goals for their people than those advocated by Washington. They believed that Washington was "accommodationist". Opponents included Northerner W. E. B. Du Bois, then a professor at Atlanta University, and William Monroe Trotter, a Boston activist who in 1901 founded the '' Boston Guardian'' newspaper as a platform for radical activism. In 1902 and 1903 groups of activists sought to gain a larger voice in the debate at the conventions of the National Afro-American Council, but they were marginalized because the conventions were dominated by Washington supporters (also known as Bookerites). Trotter in July 1903 orchestrated a confrontation with Washington in Boston, a stronghold of activism, that resulted in a minor melee and the arrest of Trotter and others; the event garnered national headlines.

In January 1904, Washington, with funding assistance from white philanthropist Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

, organized a meeting in New York to unite African American and civil rights spokesmen. Trotter was not invited, but Du Bois and a few other activists were. Du Bois was sympathetic to the activist cause and suspicious of Washington's motives; he noted that the number of activists invited was small relative to the number of Bookerites. The meeting laid the foundation for a committee to include both Washington and Du Bois, but it quickly fractured. Du Bois resigned in July 1905. By this time, both Du Bois and Trotter recognized the need for a well-organized anti-Washington activist group.

Founding

Along with Du Bois and Trotter, Fredrick McGhee of St. Paul, Minnesota, and Charles Edwin Bentley ofChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

had also recognized the need for a national activist group. The foursome organized a conference to be held July 11–13, 1905, in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

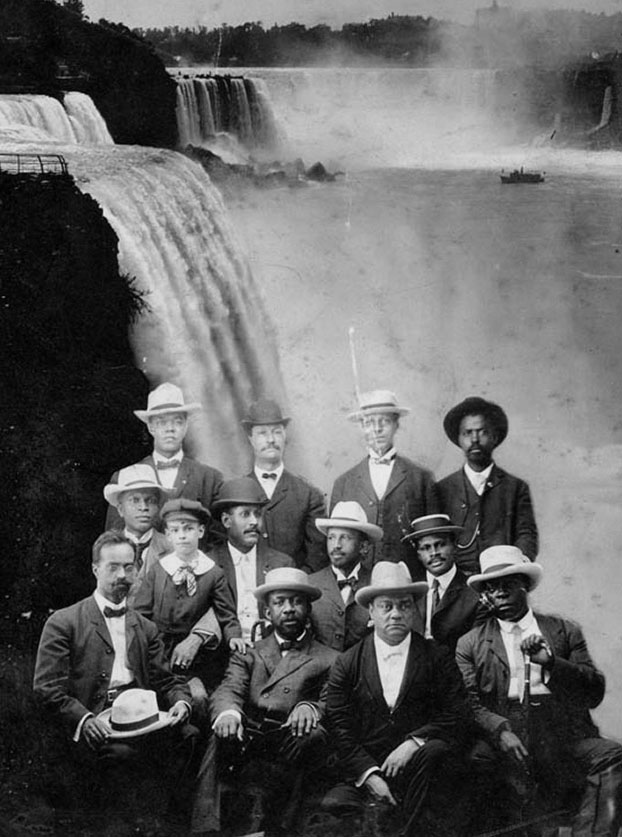

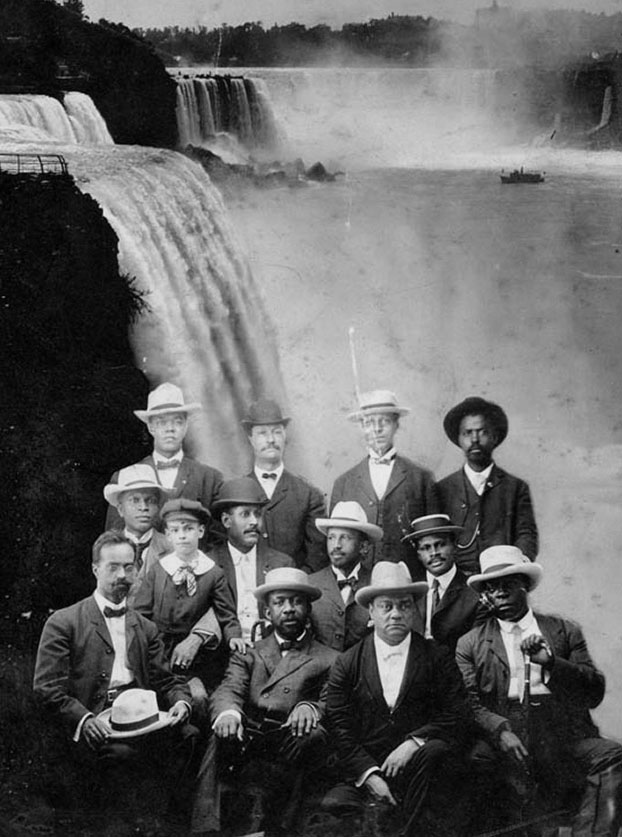

. 59 carefully selected anti-Bookerites were invited to attend; 29 showed up, including prominent community leaders and a notable number of lawyers. At the last minute, to avoid disruption, the meeting was moved to the Erie Beach Hotel in Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada, across the Niagara River from Buffalo.

The organization founded at this meeting chose Du Bois as its general secretary and Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

lawyer George H. Jackson as treasurer. It set up a number of committees to oversee progress on the organization's goals. State chapters would advance local agendas and disseminate information about the organization and its goals.Fox, p. 90. Its name was chosen to reflect the site of its first meeting and to be representative of a "mighty current" of change its leaders sought to bring about. 17 founders were each appointed as state secretary to individually represent 17 of the states of the union:

*Massachusetts – CG Morgan

*Georgia – John Hope

*Arkansas – FB Coffin

*Illinois – CE Bentley

*Kansas – B.S. Smith

*D.C. – L.M. Henshaw

*New York – G.F. Miller

*Virginia – J.L.R. Diggs

*Colorado – C.A. Franklin

*Pennsylvania – G.W. Mitchell

*Rhode Island – Byron Gunner

*New Jersey – T.A. Spraggins

*Maryland – G.R. Waller

*Iowa – G.H. Woodson

*Tennessee – Richard Hill

*Minnesota – F.L. McGhee

*West Virginia – J.R. Clifford

Founders

The 29 founders who traveled to the inaugural meeting of the Niagara Movement came from 14 states, and became known as "The Original Twenty-nine": # James Robert Lincoln Diggs – College president; pastor; ninth African American to receive a doctorate in the United States # Dr. Henry Lewis "H. L." Bailey (January 17, 1866 – July 16, 1933) – Teacher and medical doctor. # William Justin "W. Justin" Carter, Sr. (May 28, 1866 – March 23, 1947) – Pennsylvania lawyer; civil right activist; scholar; early NAACP member # William Henry "W. H." Scott (June 15, 1848 – June 27, 1910) – Born to slavery, soldier, teacher, bookseller, Baptist pastor, activist, founder of Massachusetts Racial Protective League and the National Independent Political League # Isaac F. "I.F." Bradley, Sr. (1862 – 1938) – Assistant county attorney,Wyandotte County

Wyandotte County (; county code WY) is a county in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the population was 169,245, making it Kansas's fourth-most populous county. Its county seat and most populous city is Kansas City, with which ...

; justice of the peace; judge; publisher and editor of ''The Wyandotte Echo

''The Wyandotte Echo'' is a legal newspaper for Kansas City, Kansas. The ''Wyandotte Echo'' is published every Wednesday. The newspaper is owned by and operated by M.R.P.P. Inc. The ''Wyandotte Echo'' is the official newspaper for the Wyandotte C ...

'' (1930 – 1938); father of Isaac F. Bradley, Jr., who was assistant attorney general for Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

(1937-39)''Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer'', 1844-1944, by J. Clay Smith, Jr. (1885 – 1975),

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

Press, 1999, page 519.

# Alonzo F. Herndon – Born to slavery; entrepreneur; one of the first African-American millionaires in the United States

# William Henry "W. H." Richards (January 15, 1856 – 1941) – Lawyer and law professor; secured funding from Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, with William Henry Harrison Hart

William Henry Harrison Hart (October 30, 1857 – January 6, 1934) was an List of African-American jurists, African American attorney and Professor of Criminal Law at Howard University from 1887 to 1922. He won an important legal case, ''Hart v. ...

, for first law school building at Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

; activist; alderman; mayor;''William H. Richards: A remarkable life of a remarkable man'', was a biography by Julia B. Nelson, published about 1900

# Brown Sylvester "B. S." Smith – Kansas City lawyer and City Councillor, activist. Born to parents who were born into slavery; orphaned young.

# Frederick L. McGhee

# William Monroe Trotter

# Garnett Russell "G.R." Waller (February 17, 1857 – March 7, 1941) – Shoemaker; pastor

# Harvey A. Thompson — H. A. Thompson (July 24, 1863 – ), Columbus, Ohio native; Fisk University, Le Moyne College

Le Moyne College is a private Jesuit college in DeWitt, New York.http://www.ongov.net/planning/haz/documents/Section9.7-TownofDeWitt.pdf It was founded by the Society of Jesus in 1946 and named after Jesuit missionary Simon Le Moyne. At its fo ...

and Meharry Medical College

Meharry Medical College is a Private university, private Historically black colleges and universities, historically black Medical school in the United States, medical school affiliated with the United Methodist Church and located in Nashville, Te ...

alumni; Ninth United States Cavalry (1883 – 1888); adjutant and first lieutenant of the Eighth Illinois (1894); Chicago political and business figure; clerkship at the central police station; married Frances Gowins

# William Henry Harrison Hart

William Henry Harrison Hart (October 30, 1857 – January 6, 1934) was an List of African-American jurists, African American attorney and Professor of Criminal Law at Howard University from 1887 to 1922. He won an important legal case, ''Hart v. ...

— Born to a white slave trader; jailed activist; secured funding from Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, with W. H. Richards, for first law school building at Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

; law professor; worked for United States Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States, where it serves as an executive department. The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and ...

, United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of com ...

; assistant librarian of Congress; first black lawyer appointed as special U.S. District Attorney for the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

# Lafayette M. Hershaw

# W. E. B. Du Bois – Co-founder of the NAACP

# Charles E. Bentley

# Clement G. Morgan

# Freeman H. M. Murray

# J. Max Barber ''Men of mark; eminent, progressive and rising''

''Men of mark; eminent, progressive and rising''by Rev. Wm. J. Simmons, Geo. R. Rewell & Co., Ohio, 1887, page 194. # George Frazier Miller (November 28, 1864 – May 9, 1943) — rector of St. Augustine's Episcopal Church, Brooklyn; socialist; civil rights activist # George Henry "G. H." Woodson (December 15, 1865 – July 7, 1933) — Criminal trial attorney, born to newly emancipated slaves; founder and president of both the Iowa Negro Bar Association in 1901 and — subsequent to being denied membership in the

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

(along with Gertrude Rush, S. Joe Brown, James B. Morris, and Charles P. Howard, Sr.) — the National Negro Bar Association, in 1925, which became the National Bar Association

The National Bar Association (NBA) was founded in 1925 and is the nation's oldest and largest national network of predominantly African-American attorneys and judges. It represents the interests of approximately 65,000 lawyers, judges, law profess ...

(NBA), of which he also served as president ''emeritus''; President Coolidge appointed Woodson chairman of the first all-Negro commission ever sent overseas, with a mandate to investigate the economic conditions of the Virgin Islands (illustrated report available from the U. S. department of labor archives)

# James S. Madden — Bookkeeper; activist; desegregationist; worked to establish the Chicago branch of the Niagara Movement with Charles E. Bentley; Provident Hospital trustee; assisted in the founding of the Equal Opportunity League

# Henry C. Smith – Musician, composer; civil rights activist; Ohio deputy oil inspector; co-founder and editor of ''The Cleveland Gazette

''The Cleveland Gazette'' was a weekly newspaper published in Cleveland, Ohio, from August 25, 1883, to May 20, 1945. It was an African-American newspaper owned and edited by Harry Clay Smith, initially with a group of partners. Circulation was es ...

''

# Emery T. "E.T." Morris (1849 - 1924) — Massachusetts deputy sealer of weights and measures; druggist; rail porter; stationary steam engineer; lay teacher who created extensive antislavery libraries in New England; founder of the Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

branch of the Movement

# Richard Hill (October 12, 1864 – ) – Native of Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and ...

; teacher and city schools supervisor; insurance and real estate entrepreneur; served as NM Secretary for Tennessee; father of civil rights activist and lawyer Richard Hill, Jr.

# Robert H. Bonner – Beverly, Massachusetts artist; Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

alumni; Colored Yale Quartette singer; lawyer; long associated the Trotter family

# Byron Gunner (July 4, 1857 – February 9, 1922) – Congregational minister; president of the National Equal Rights League; later a strong ally of William Monroe Trotter; Rhode Island Niagara Movement secretary; father of playwright Mary Frances Gunner

# Edwin Bush "E.B." Jourdain — Boston lawyer; hosted "the New Bedford Annex for Boston Radicals"; father of journalist, activist and first black alderman of Evanston, Illinois

Evanston ( ) is a city, suburb of Chicago. Located in Cook County, Illinois, United States, it is situated on the North Shore along Lake Michigan. Evanston is north of Downtown Chicago, bordered by Chicago to the south, Skokie to the west, ...

Edwin B. Jourdain, Jr.

# George W. Mitchell – Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

attorney; Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

Latin and Greek professor; Pennsylvania NM secretary; father of lawyer and real estate investor George Henry Mitchell

Inaugural meeting location

The First Niagara Conference was originally scheduled for

The First Niagara Conference was originally scheduled for Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, but because of threatened disruptions from partisans of the politically powerful Booker T. Washington fled at the last minute to the Erie Beach Hotel in Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada. Du Bois described the meeting as "secret". One Bookerite, Clifford Plummer, traveled to Buffalo to check up on the proceedings, looked around, and "happily" reported back that there was no conference.

To disguise this, it was said that they were refused accommodation in Buffalo. However, no evidence supports this. According to contemporary reports, Buffalo hotels complied with a statewide anti-discrimination law passed in 1895, and in a recent article it is called an "unlikely...legend".

Declaration of Principles

The attendees of the inaugural meeting drafted a "Declaration of Principles," primarily the work of Du Bois and Trotter. The group's philosophy contrasted with the conciliatory approach by Booker T. Washington, who proposed patience over militancy. The declaration defined the group's philosophy and demands: politically, socially and economically. It described the progress made by "Negro-Americans","particularly the increase of intelligence, the buy-in of property, the checking of crime, the uplift in home life, the advance in literature and art, and the demonstration of constructive and executive ability in the conduct of great religious, economic and educational institutions."It called for blacks to be granted manhood suffrage, for equal treatment for all American citizens alike. Very specifically, it demanded equal economic opportunities, in the rural districts of the South, where many blacks were trapped by

sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

in a kind of indentured servitude to whites. This resulted in "virtual slavery". The Niagara Movement wanted all African Americans in the South to have the ability to "earn a decent living".

On the subject of education, the authors declared that not only should it be free, but it should also be made compulsory. Higher education, they declared, should be governed independently of class or race, and they demanded action to be taken to improve "high school facilities." This they emphasized: "either the United States will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States." They demanded for judges to be selected independently of their race, and for convicted criminals, white or black, to be given equal punishments for their respective crimes.

In his address to the nation, W. E. B. Du Bois stated, "We are not more lawless than the white race; we remore often arrested, convicted and mobbed. We want justice, even for criminals and outlaws." He called for the abolition of the

On the subject of education, the authors declared that not only should it be free, but it should also be made compulsory. Higher education, they declared, should be governed independently of class or race, and they demanded action to be taken to improve "high school facilities." This they emphasized: "either the United States will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States." They demanded for judges to be selected independently of their race, and for convicted criminals, white or black, to be given equal punishments for their respective crimes.

In his address to the nation, W. E. B. Du Bois stated, "We are not more lawless than the white race; we remore often arrested, convicted and mobbed. We want justice, even for criminals and outlaws." He called for the abolition of the convict lease

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; f ...

system. Established after the Civil War before southern states built prisons, convicts were leased out to work as cheap laborers for "railway contractors, mining companies and those who farm large plantations." Southern states had passed laws targeting blacks and leasing them out to pay off fines or fees they could not manage. The system continued, earning money for local jurisdictions and the state from leasing out prisoners. There was little oversight, and many prisoners were abused and worked to death. Urging a return to the faith of "our fathers," the declaration appealed for every person to be considered equal and free.

The declaration also targeted the treatment blacks received from labor unions, often oppressed and not fully protected by their employers nor granted permanent employment. It validated the already announced affirmation that such protest against outright injustice would not cease until such discrimination did. Secondly, Du Bois and Trotter stated the irrationality of discriminating based on one's "physical peculiarities", whether it be place of birth or color of skin. Perhaps one's ignorance, or immorality, poverty or diseases are legitimate excuses, but not the matters over which individuals have no control. Near its end, the document condemns the Jim Crow laws, the rejection of blacks for enlistment in the Navy and by the military academies, the non-enforcement of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments protecting the rights of blacks, and the "unchristian" behaviors of churches that segregate and show prejudice to their black brothers. The Declaration thanked those who "stand for equality" and the advancement of this cause.

Opposition

Booker T. Washington and his supporters tried to discourage growth of this rival movement. Washington, Thomas Fortune, and Charles Anderson met after learning of the Movement's formation, and agreed to suppress news of it in the black press. They acquired supporters in Archibald Grimké and Kelly Miller, two moderates who had been friendly with Trotter, but had not been invited by Du Bois to the convention (Grimké was hired by Fortune's ''New York Age

''The New York Age'' was a weekly newspaper established in 1887. It was widely considered one of the most prominent African-American newspapers of its time.

''). The ''Age'' editorialized that the Movement was little more than an attempt to tear down the house that Washington had labored to set up. A Boston supporter of Washington convinced the printer of Trotter's ''Guardian'' to withdraw his services, but Trotter managed to continue printing anyway. Prominent white activists, including Francis Jackson Garrison and Oswald Garrison Villard (family of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

, a hero of Trotter), refused to attend Trotter-organized commemorations of their father's birth centennial. They chose a celebration organized by Bookerites.

Despite Washington's attempts at suppression, Du Bois reported at the end of 1905 that a number of black publications had published accounts of the Movement's activities, and it received further publicity as a consequence of Bookerite press attacks against it. Washington also attacked the Constitution League, a multi-racial civil rights group that was also opposed to his accommodationist policies. The Movement made common cause with this organization.

Activities

After the initial meeting, delegates returned to their home territories to establish local chapters. By mid-September 1905, they had established chapters in 21 states, and the organization had 170 members by year's end. Du Bois founded a magazine, ''The Moon'', in an attempt to establish an official mouthpiece for the organization. Due to lack of funding, it failed after a few months of publication. A second publication, ''The Horizon'', was started in 1907 and survived until 1910.Rudwick, p. 190.Rudwick, p. 198. The movement's second meeting, the first to be held on U.S. soil and arguably the movement's high point, took place at

The movement's second meeting, the first to be held on U.S. soil and arguably the movement's high point, took place at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. st ...

, the site of abolitionist John Brown's 1859 raid. The three-day gathering, from August 15 to 18, 1906, took place at the campus of Storer College

Storer College was a historically black college in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, that operated from 1867 to 1955. A national icon for Black Americans, in the town where the 'end of American slavery began', as Frederick Douglass famously put i ...

(now part of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, originally Harpers Ferry National Monument, is located at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers in and around Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The park includes the historic center of Harpers F ...

). Convention attendees discussed how to secure civil rights for African Americans, and the meeting was later described by Du Bois as "one of the greatest meetings that American Negroes ever held." Attendees walked from Storer College to the nearby Murphy Family farm, relocation site of the historic fort where John Brown's quest to end slavery reached its bloody climax. Once there, they removed their shoes and socks to honor the hallowed ground and participated in a ceremony of remembrance.

Several of the organization's chapters made substantive contributions to the advance of civil rights in 1906. The Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

chapter successfully lobbied against state legislation for the segregation of railroad cars, but was unable to stop the state from helping to fund the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

, a commemoration of the founding of racially motivated Jamestown, Virginia, in which Virginia sought to limit black admission. The Illinois chapter convinced Chicago theater critics to ignore a production of '' The Clansman''.

During the early months of 1906 friction began to develop between Du Bois and Trotter over the admission of women to the organization. Du Bois supported the idea, and Trotter opposed it, but eventually relented, and the matter was smoothed over during the 1906 meeting. Their division became more significant when Trotter split with longtime supporter and Movement member Clement Morgan over Massachusetts politics and control of the local Movement chapter, with Du Bois siding with the latter. When the Movement met in Boston in 1907 Du Bois not only admitted Grimké and Miller to the organization, he reappointed Morgan to a leading position in the organization. Further attempts to heal the rift failed, and Trotter then resigned from the Movement.

In 1906 there were several proposals floated in the black press that the Movement be merged with other organizations. None of these proposals got off the ground, with the only substance being a meeting between the Movement's Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

chapter and members of the Bookerite National Afro-American Council.

The Movement, in conjunction with the Constitution League (which took Du Bois on as a director), began organizing legal challenges to segregationist laws in early 1907. For an organization with a limited budget, this was an expensive proposition: the single case they mounted challenging Virginia's railroad segregation law put the organization into debt.

Du Bois had sought to return to Harpers Ferry for the 1907 annual meeting, but Storer College refused to grant them permission, claiming the group's presence in 1906 had been followed by financial and political pressure from its supporters to distance itself from them. The 1907 meeting was held in Boston, with conflicting attendance reports. Du Bois claimed 800 attendees, while the Bookerite '' Washington Bee'' claimed only about 100 in attendance. The convention published an "Address to the World" in which it called on African-Americans not to vote for Republican Party candidates in the 1908 presidential election, citing President

The Movement, in conjunction with the Constitution League (which took Du Bois on as a director), began organizing legal challenges to segregationist laws in early 1907. For an organization with a limited budget, this was an expensive proposition: the single case they mounted challenging Virginia's railroad segregation law put the organization into debt.

Du Bois had sought to return to Harpers Ferry for the 1907 annual meeting, but Storer College refused to grant them permission, claiming the group's presence in 1906 had been followed by financial and political pressure from its supporters to distance itself from them. The 1907 meeting was held in Boston, with conflicting attendance reports. Du Bois claimed 800 attendees, while the Bookerite '' Washington Bee'' claimed only about 100 in attendance. The convention published an "Address to the World" in which it called on African-Americans not to vote for Republican Party candidates in the 1908 presidential election, citing President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

's support for Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

.

End of the Movement

William Monroe Trotter's departure after the 1907 meeting had a serious negative impact on the organization, as did disagreements about which party to support in the 1908 election. Du Bois, with some reluctance, endorsed Democratic Party candidateWilliam Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

, but many African-Americans could not bring themselves to break from the Republicans, and William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

won the election, receiving significant African-American support. The 1908 annual meeting, held in Oberlin, Ohio

Oberlin is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States, 31 miles southwest of Cleveland. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin College, a liberal arts college and music conservatory with approximately 3,000 students.

The town is the birthplace of th ...

, was a much smaller affair, and exposed disunity and apathy within the group at both local and national levels. Du Bois invited Mary White Ovington, a settlement worker and socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

he had met in 1904, to address the organization. She was the only white woman to be so honored. By 1908, Washington and his supporters successfully made serious inroads with the press (both white and black), and the Oberlin meeting received almost no coverage. Believing the Movement to be "practically dead", Washington also prepared an obituary of the organization for the ''New York Age

''The New York Age'' was a weekly newspaper established in 1887. It was widely considered one of the most prominent African-American newspapers of its time.

'' to publish.

In 1909, chapter activities continued to dwindle, membership dropped, and the 1910 annual meeting (held at Sea Isle City, New Jersey

Sea Isle City is a city in Cape May County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is part of the Ocean City metropolitan statistical area. As of the 2020 United States census, the city's year-round population was 2,104, a decrease of 10 (−0.5 ...

) was a small affair that again received no significant press. It was the organization's last meeting.

Legacy

In the wake of the Springfield Race Riot of 1908, a major race riot in Springfield, Illinois, a number of prominent white civil rights activists called for a major conference on race relations. Held inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

in early 1909, the conference laid the foundation for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP), which was formally established in 1910. In 1911, Du Bois (who was appointed the NAACP's director of publications) recommended that the remaining membership of the Niagara Movement support the NAACP's activities. William Monroe Trotter attended the 1909 conference, but did not join the NAACP; he instead led other small activist civil rights organizations and continued to publish the ''Guardian'' until his death in 1934.

The Niagara Movement did not appear to be very popular with the majority of the African-American population, especially in the South. Booker T. Washington, at the height of the Movement's activities in 1905 and 1906, spoke to large and approving crowds across much of the country. The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot hurt Washington's popularity, giving the Niagarans fuel for their attacks on him. However, given that Washington and the Niagarans agreed on strategy (opposition to Jim Crow laws and support of equal protection and civil rights) but disagreed on tactics, a reconciliation between the factions began after Washington died in 1915.Norrell, p. 422. The NAACP went on to become the leading African-American civil rights organization of the 20th century.

See also

*Nadir of American race relations

The nadir of American race relations was the period in African American history and the history of the United States from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century when racism in the country, especially racism against ...

References

Further reading

* Capeci, Dominic J., and Jack C. Knight. 1999. "W.E.B. Du Bois's Southern Front: Georgia" Race Men" and the Niagara Movement, 1905-1907." ''Georgia Historical Quarterly'' 83.3 (1999): 479-50online

* * * Jones, Angela. 2016. "Lessons from the Niagara movement: Prosopography and discursive protest." ''Sociological Focus'' 49.1 (2016): 63-8

online

* Jones, Angela. 2011. ''African American civil rights: Early activism and the Niagara Movement'' (ABC-CLIO, 2011)

details

* * * *

Primary sources

* Du Bois, W. E. B. "Niagara movement speech." (1905).online

External links

Niagara's Declaration of Principles

{{Authority control Niagara Falls, Ontario NAACP African Americans' rights organizations Organizations established in 1905 Organizations disestablished in 1910 Progressive Era in the United States Civil rights organizations in the United States 1905 establishments in New York (state) Storer College