New Spanish Baroque on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

New Spanish Baroque, also known as Mexican Baroque, refers to

New Spanish Baroque, also known as Mexican Baroque, refers to

''The Virgin of Guadalupe, a painting by the colonial artist Juan Correa''

colonial-mexico.com He also made paintings of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Rome in 1669.

Some of Cristóbal de Villalpando's (c. 1649-1714) early work dates from 1675 with the high altar of the Franciscan convent of St. Martin of Tours in Huaquechula, where there are 17 of his paintings; but that is not necessarily the beginning of his career. It is likely that the painter was born in

Some of Cristóbal de Villalpando's (c. 1649-1714) early work dates from 1675 with the high altar of the Franciscan convent of St. Martin of Tours in Huaquechula, where there are 17 of his paintings; but that is not necessarily the beginning of his career. It is likely that the painter was born in

Gutierre de Cetina (1520 - 1557) was a Spanish poet of the Renaissance and the

Gutierre de Cetina (1520 - 1557) was a Spanish poet of the Renaissance and the

In the first months of 1607 he returned to New Spain. Two years later he obtained a bachelor's degree in

In the first months of 1607 he returned to New Spain. Two years later he obtained a bachelor's degree in

The heavy rains of 1691 flooded the fields and threatened to flood the city; the wheat crop was devastated by a disease. Sigüenza used a precursor of the microscope to discover that the cause of this disease in wheat was the Chiahuiztli, an insect like the flea. As a result of this disaster, the following year there was a severe shortage of food which caused large-scale rioting. Mobs looted Spaniards' shops and caused numerous fires in government buildings. Sigüenza managed to salvage the city library from the fire, avoiding a great loss. Sigüenza estimated that about ten thousand people took part in the riot. As the royal cosmographer of New Spain he drew hydrologic maps of the

The heavy rains of 1691 flooded the fields and threatened to flood the city; the wheat crop was devastated by a disease. Sigüenza used a precursor of the microscope to discover that the cause of this disease in wheat was the Chiahuiztli, an insect like the flea. As a result of this disaster, the following year there was a severe shortage of food which caused large-scale rioting. Mobs looted Spaniards' shops and caused numerous fires in government buildings. Sigüenza managed to salvage the city library from the fire, avoiding a great loss. Sigüenza estimated that about ten thousand people took part in the riot. As the royal cosmographer of New Spain he drew hydrologic maps of the

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651 - 1695), known as the "Tenth

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651 - 1695), known as the "Tenth

Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

art in the Viceroyalty of New Spain. During this period, artists of New Spain experimented with expressive, contrasting, and realistic creative approaches, making art that became highly popular in New Spanish society.

Among notable artworks are polychrome sculptures, which as well as the technical skill they display, reflect the expressiveness and the colour contrasts characteristic of New Spanish Baroque.

Two styles can be traced in the architecture of New Spain: the ''Salomónico'', developed from the mid-17th century, and the ''Estípite'', which began in the early 18th century.

A model of the Cathedral of Puebla represents the architectural magnificence of New Spain. A choir book and a harpsichord of the 18th century highlight the importance of music for the colonial society of the Baroque period in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

.

Painting

In the realm of painting, New Spanish baroque had great artists whose works are in museums such as the Museum of the Viceroyalty inTepotzotlán

Tepotzotlán () is a city and a municipality in the Mexico, Mexican state of Mexico. It is located northeast of Mexico City about a 45-minute drive along the Mexico City-Querétaro at marker number 41. In Aztec times, the area was the center o ...

, El Carmen Museum in San Ángel

San Ángel is a colonia or neighborhood of Mexico City, located in the southwest in Álvaro Obregón borough. Historically, it was a rural community, called Tenanitla in the pre-Hispanic period. Its current name is derived from the El Carmen mon ...

, Santa Mónica Museum in Puebla

Puebla ( en, colony, settlement), officially Free and Sovereign State of Puebla ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Puebla), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 217 municipalities and its cap ...

, and Metropolitan Cathedral in Mexico City.

Among the most distinguished artists were:

*Miguel Cabrera

José Miguel Cabrera Torres (born April 18, 1983), nicknamed "Miggy", is a Venezuelan professional baseball first baseman and designated hitter for the Detroit Tigers of Major League Baseball (MLB). Since his debut in 2003 he has been a two-t ...

*Juan Correa

Juan Correa (1646–1716) was a Mexican distinguished painter of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. His years of greatest activity were from 1671 to 1716. He was an Afro-Mexican, the son of a Mulatto or dark-skinned physician fr ...

*Cristóbal de Villalpando

Cristóbal de Villalpando (ca. 1649 – 20 August 1714) was a Baroque Criollo artist from New Spain, arts administrator and captain of the guard. He painted prolifically and produced many Baroque works now displayed in several Mexican cathedrals ...

* Simón Pereyns

Simón Pereyns

Simón Pereyns lived inAntwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

circa 1530 then Mexico circa 1600. He was a Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

painter and in 1558, he moved to Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

and then to Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, where he worked as a court artist.

In 1566, he went to New Spain, achieved fame with his paintings in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. Many works are attributed to him, but most of them have been lost; among those conserved are the ten tables of the altarpiece of Huejotzingo

Huejotzingo ( is a small city and municipality located just northwest of the city of Puebla, in central Mexico. The settlement's history dates back to the pre-Hispanic period, when it was a dominion, with its capital a short distance from where th ...

(1586), which revealed the influence of Dürer and his work on Saint Christopher

Saint Christopher ( el, Ἅγιος Χριστόφορος, ''Ágios Christóphoros'') is venerated by several Christian denominations as a martyr killed in the reign of the 3rd-century Roman emperor Decius (reigned 249–251) or alternatively ...

(1585).

Pereyns was put on trial on religious charges. His beliefs were inherited from his ancestors, specifically his father, who was a Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

. While he was in prison, he painted a picture called "Our Lady of Atonement", hoping to win a pardon. He was released and donated the painting to the Archbishop of Mexico

The Archdiocese of Mexico ( la, Archidioecesis Mexicanensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church that is situated in Mexico City, Mexico. It was erected as a diocese on 2 September 1530 and elevated to ...

, whose successors mounted it on the Altar del Perdón at the Metropolitan Cathedral.

Juan Correa

Juan Correa (1646-1716) was a Novohispanic painter active between 1676 and 1716. His painting covers topics both religious and secular. One of his best works is considered to be the "Assumption of the Virgin" in the Cathedral of Mexico City; several of his works depicting Our Lady of Guadalupe found their way to Spain.colonial-mexico.com He also made paintings of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Rome in 1669.

Cristóbal de Villalpando

Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

in 1649. Little is known about his childhood and adolescence, the earliest documented date being his wedding in 1669. He married María de Mendoza, with whom he had four children.

Undoubtedly, Villalpando was one of the foremost painters of Mexico City during the latter part of the 17th century, as evidenced by the collection of triumphal paintings that were commissioned by the council of the Cathedral of Mexico, for decorating the walls of the sacristy of the church. The canvases prepared for that commission were: The Triumph of the Catholic Church, The Triumph of St. Peter, St. Michael's victory (known as Woman of the Apocalypse) and the appearance of St. Michael on Mount Gargano. Unfortunately, due to structural faults in the vaults of the building, Villalpando was unable to complete the intended set of six paintings; they were completed by Juan Correa

Juan Correa (1646–1716) was a Mexican distinguished painter of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. His years of greatest activity were from 1671 to 1716. He was an Afro-Mexican, the son of a Mulatto or dark-skinned physician fr ...

.

Due to this hindrance to his work at Mexico City, Villalpando moved to Puebla de los Ángeles where he carried out similar work at the Cathedral there. He produced a well-known oil painting titled "Glorification of the Virgin", in the dome of the Chapel de Los Reyes located in the end wall of the church. It is also worth noting the amount of his work found in the church of the Profesa in Mexico City. His importance was recognized by the painters' guild, of which he became leader on several occasions. He reached old age with a great reputation, and he was recognized as an important stylistic influence on later generations. He is considered one of the last exponents of Baroque painting in New Spain: after his death New Spanish plastic art took a different path.

Miguel Cabrera

Miguel Cabrera (1695-1768) was an extraordinarily prolific artist, specialising in depictions of theVirgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

and other saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Orth ...

. He is regarded as the leading colourist of the 18th century.

His paintings were very much in demand: many requests for pictures came from convents, churches, palaces, and noble houses.

Writing and philosophy

A wide range of poets and writers fell within the New Spanish Baroque tradition.Gutierre de Cetina

Gutierre de Cetina (1520 - 1557) was a Spanish poet of the Renaissance and the

Gutierre de Cetina (1520 - 1557) was a Spanish poet of the Renaissance and the Spanish Golden Age

The Spanish Golden Age ( es, Siglo de Oro, links=no , "Golden Century") is a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain, coinciding with the political rise of the Spanish Empire under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and the Spanish Ha ...

. He was born in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

, Spain and died in the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Of a noble and wealthy family, he lived for a long time in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, where he was a soldier under the command of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. Spending much time in the court of the Prince of Ascoli, to whom he dedicated numerous poems, and also associated with Luis de Leyva and distinguished humanist and poet Diego Hurtado de Mendoza. He adopted the nickname "Vandalio" and composed a song in the Petrarchan style to a beautiful woman named Laura Gonzaga. To such a woman was dedicated the famous madrigal that has been included in all anthologies of poetry in the Spanish language:

In the same songbook there are many sonnets whose pattern was essentially the rendering of a loving thought ofEyes clear, calm, Since you are praised for your tender gaze, Why, when you look at me, do you look angry?

Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

or Ausiàs March

Ausiàs March (Catalan and ; 1400March 3, 1459) was a medieval Valencian poet and knight from Gandia, Valencia. He is considered one of the most important poets of the "Golden Century" (''Segle d'or'') of Catalan/Valencian literature.

Biog ...

in the quartets, and a further, more personal development in the tercets.

In 1554 Cetina returned to Spain and in 1556 went to Mexico; he had previously been there between 1546 and 1548, with his uncle Gonzalo Lopez, who had gone there as chief accountant. He fell in love again, with Leonor de Osma, and was mortally wounded in 1557 in Puebla de los Angeles by an envious rival, Hernando de Nava.

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón y Mendoza

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón y Mendoza (c.1581 - 1639) was born inTaxco

Taxco de Alarcón (; usually referred to as simply Taxco) is a small city and administrative center of Taxco de Alarcón Municipality located in the Mexican state of Guerrero. Taxco is located in the north-central part of the state, from the ci ...

. He was a Novohispanic

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the A ...

writer of the Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

who developed various forms of drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has b ...

. His works include the comedy "La Verdad Sospechosa" (Suspicious Truth), which is one of the most important works of Spanish American Baroque theater, comparable to the best pieces of Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio ( , ; 25 November 156227 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist. He was one of the key figures in the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque literature. His reputation in the world of Spanish literatur ...

or Tirso de Molina.

Little is known about the early life of Ruiz de Alarcón. It is known that his maternal grandfather was Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and his paternal grandfather was the son of a priest of La Mancha

La Mancha () is a natural and historical region located in the Spanish provinces of Albacete, Cuenca, Ciudad Real, and Toledo. La Mancha is an arid but fertile plateau (610 m or 2000 ft) that stretches from the mountains of Toledo to th ...

and a Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or s ...

slave. It is probable that he came from a family well connected with the Castilian nobility. He studied from 1596 to 1598 in the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico

The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico (in es, Real y Pontificia Universidad de México) was founded on 21 September 1551 by Royal Decree signed by Charles I of Spain, in Valladolid, Spain. It is generally considered the first university ...

. About 1600 he set off for the University of Salamanca

The University of Salamanca ( es, Universidad de Salamanca) is a Spanish higher education institution, located in the city of Salamanca, in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It was founded in 1218 by King Alfonso IX. It is t ...

, where he studied civil law and specialized in canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

.

While in Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

, Alarcón rose to prominence as the author of dramas and stories. In 1606 he went to Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

in order to practice commercial and canonical law. There, he met Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

, who was subsequently influenced by his works, including La cueva de Salamanca (The Cave of Salamanca) "La cueva de Salamanca" ("The Cave of Salamanca") is an entremés written by Miguel de Cervantes. It was originally published in 1615 in a collection called''Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses nuevos, nunca representados''

Plot summary

The head of the ...

and "El Semejante A Sí Mismo" (Like unto Himself).

In the first months of 1607 he returned to New Spain. Two years later he obtained a bachelor's degree in

In the first months of 1607 he returned to New Spain. Two years later he obtained a bachelor's degree in law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

and several times tried unsuccessfully to gain a university chair. His next move was to Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, where he began the most fruitful period of his literary output. His early works were "Las Paredes Oyen" (Walls Have Ears) and "Los Pechos Privilegiados" (The Privileged), both meeting with some success. He soon came to be recognised in literary circles in Madrid, but never established close relations with any of their members. Indeed, he earned the hostility of others. We know of many satirical quatrains and disguised allusions to Alarcón, who was always ridiculed for his physique - he was a hunchback - and his American origins. He, in turn, responded to the vast majority of personal attacks and never stopped writing.

It has been suggested that he may have collaborated with Tirso de Molina, one of the most famous writers of his time and the one who most influenced his works. There are no written evidence of such a collaboration, although it is thought that at least two of the comedies of Tirso, published in the second volume of his works (Madrid, 1635), were in fact written by or with the collaboration of Alarcón.

With the accession of Philip IV, in 1621, the theater achieved an important place in the royal court. Alarcón soon struck up a useful friendship with the son-in-law of the powerful Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares

Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, 1st Duke of Sanlúcar, 3rd Count of Olivares, GE, known as the Count-Duke of Olivares (taken by joining both his countship and subsequent dukedom) (6 January 1587 – 22 July 1645), was a Spanish royal favourit ...

, Ramiro Felipe de Guzmán, under whose patronage he grew better-known as a poet. Between 1622 and 1624 he wrote "La Amistad Castigada" (Punished Friendship) and "El dueño de las estrellas" (The Owner of the Stars) as well as the vast majority of his plays. From 1625 he served on the Council of the Indies

The Council of the Indies ( es, Consejo de las Indias), officially the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies ( es, Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias, link=no, ), was the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire for the Amer ...

, thanks to the intercession of his friend Ramiro Felipe de Guzmán.

During the first months of 1639, Alarcón's health began to deteriorate. He stopped attending the council's meetings and was replaced in his position as rapporteur. In August he dictated his will, making provision for all his debts and debtors. He died on August 4, 1639 and was buried in the parish of San Sebastián.

Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora

Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645 - 1700) was the youngest son of eight children and was related to the famous BaroqueCulteranismo

''Culteranismo'' is a stylistic movement of the Baroque period of Spanish history that is also commonly referred to as ''Gongorismo'' (after Luis de Góngora). It began in the late 16th century with the writing of Luis de Góngora and lasted throu ...

poet Luis de Góngora

Luis de Góngora y Argote (born Luis de Argote y Góngora; ; 11 July 1561 – 24 May 1627) was a Spanish Baroque lyric poet and a Catholic priest. Góngora and his lifelong rival, Francisco de Quevedo, are widely considered the most prominent ...

. His father was a tutor to the royal family in Spain; after he emigrated to the New World he joined the bureaucracy of the viceroyalty.

In 1662, Sigüenza entered the Jesuit college of Tepotzotlán

Tepotzotlán () is a city and a municipality in the Mexico, Mexican state of Mexico. It is located northeast of Mexico City about a 45-minute drive along the Mexico City-Querétaro at marker number 41. In Aztec times, the area was the center o ...

to begin his religious studies, which he continued in Puebla

Puebla ( en, colony, settlement), officially Free and Sovereign State of Puebla ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Puebla), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 217 municipalities and its cap ...

. In 1667 he was expelled from the order for indiscipline. He returned to Mexico City and entered the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico

The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico (in es, Real y Pontificia Universidad de México) was founded on 21 September 1551 by Royal Decree signed by Charles I of Spain, in Valladolid, Spain. It is generally considered the first university ...

. In 1672 he took the post of professor of mathematics and astrology, the position that Diego Rodríguez had occupied thirty years before. Sigüenza held this position for the next twenty years. In 1681, he wrote a book, "A Philosophical Manifesto", concerning comets

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ar ...

, in an attempt to calm the superstitious fears arising from this cosmic phenomenon. A Jesuit, Eusebio Kino

Eusebio Francisco Kino ( it, Eusebio Francesco Chini, es, Eusebio Francisco Kino; 10 August 1645 – 15 March 1711), often referred to as Father Kino, was a Tyrolean Jesuit, missionary, geographer, explorer, cartographer and astronomer bor ...

, strongly criticized this text from an Aristotelian and Thomistic point of view; but, far from being intimidated, Sigüenza responded by publishing his work "Libra astronómica y philosóphica" (1690). Here he rigorously justified his view of comets, referring to the most current scientific knowledge of his time; against the Thomism and Aristotelianism of Father Kino he quoted authors like Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

, Descartes, Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws o ...

and Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

.

Until recently it had been thought that another of his works, "Los infortunios de Alonso Ramírez" (1690), describing the adventures of a Puerto Rican named Alonso Ramírez, was a mere fiction invented by the famous Mexican intellectual. It has now been shown to be a historical account. ee_article_on_Siguenza_y_Gongora.html" ;"title="Siguenza_y_Gongora.html" ;"title="ee article on Siguenza y Gongora">ee article on Siguenza y Gongora">Siguenza_y_Gongora.html" ;"title="ee article on Siguenza y Gongora">ee article on Siguenza y Gongora

The heavy rains of 1691 flooded the fields and threatened to flood the city; the wheat crop was devastated by a disease. Sigüenza used a precursor of the microscope to discover that the cause of this disease in wheat was the Chiahuiztli, an insect like the flea. As a result of this disaster, the following year there was a severe shortage of food which caused large-scale rioting. Mobs looted Spaniards' shops and caused numerous fires in government buildings. Sigüenza managed to salvage the city library from the fire, avoiding a great loss. Sigüenza estimated that about ten thousand people took part in the riot. As the royal cosmographer of New Spain he drew hydrologic maps of the

The heavy rains of 1691 flooded the fields and threatened to flood the city; the wheat crop was devastated by a disease. Sigüenza used a precursor of the microscope to discover that the cause of this disease in wheat was the Chiahuiztli, an insect like the flea. As a result of this disaster, the following year there was a severe shortage of food which caused large-scale rioting. Mobs looted Spaniards' shops and caused numerous fires in government buildings. Sigüenza managed to salvage the city library from the fire, avoiding a great loss. Sigüenza estimated that about ten thousand people took part in the riot. As the royal cosmographer of New Spain he drew hydrologic maps of the Valley of Mexico

The Valley of Mexico ( es, Valle de México) is a highlands plateau in central Mexico roughly coterminous with present-day Mexico City and the eastern half of the State of Mexico. Surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, the Valley of Mexico w ...

. In 1693 he was sent by the viceroy as a companion of Andrés de Pez

Andrés de Pez y Malzarraga (1657 - May 7, 1723) was a Spanish Naval commander and founder of Pensacola, Florida.

Life and career

Andrés de Pez was born in Cádiz in 1657 into a naval tradition. His father and older brother were Spanish Naval c ...

in an exploration trip to the north of the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

and in particular the peninsula of Florida, where he drew maps of Pensacola Bay

Pensacola Bay is a bay located in the northwestern part of Florida, United States, known as the Florida Panhandle.

The bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, is located in Escambia County and Santa Rosa County, adjacent to the city of Pensacola ...

and the mouth of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

. This experience may have inspired him to write about marine adventure in the "Misfortunes of Alonso Ramirez".

In his later years he spent much time collecting material for a history of ancient Mexico. Unfortunately, his untimely death interrupted the work, which was not resumed until centuries later when criolla self-awareness had developed enough to be interested in the identity of their nation. Sigüenza had directed that upon his death, his valuable library with more than 518 books would be donated to a Jesuit school, and his body handed over to medical research in order to find a cure for the disease that caused his death.

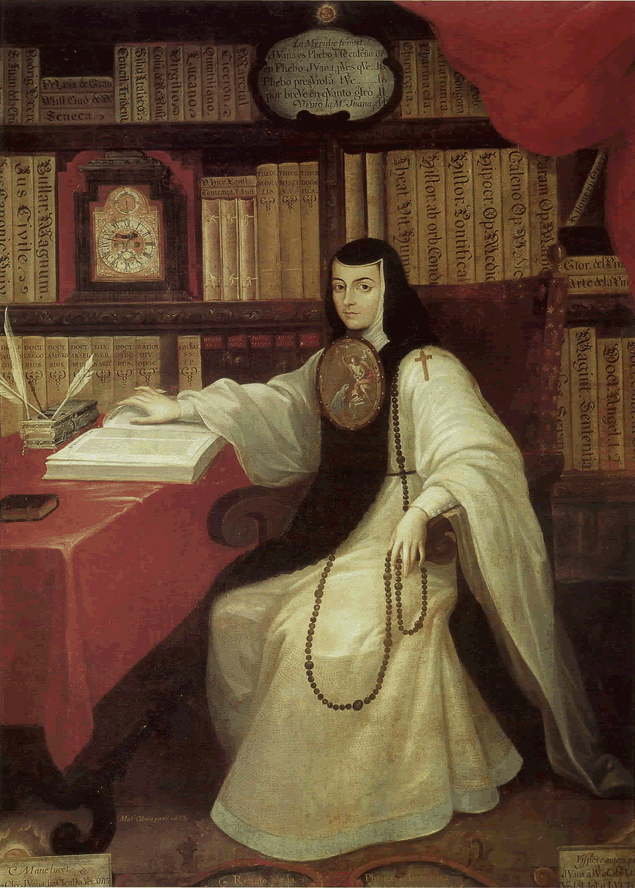

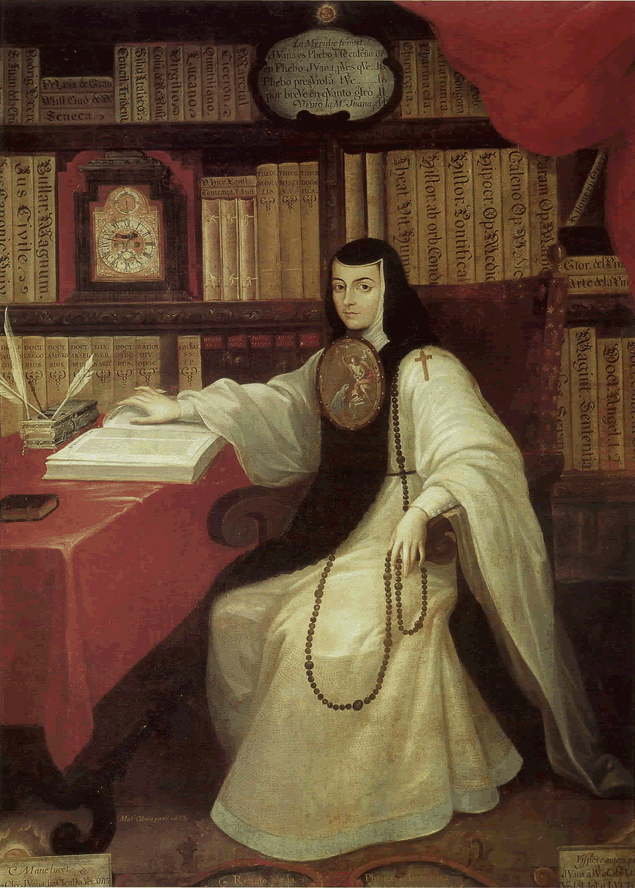

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651 - 1695), known as the "Tenth

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651 - 1695), known as the "Tenth Muse

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses ( grc, Μοῦσαι, Moûsai, el, Μούσες, Múses) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in ...

", was born on 12 November 1651 in San Miguel Nepantla and died in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

on April 17, 1695. She was one of the greatest writers during the Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

. Her passion for literature began in childhood, but as a woman, she could not get into university, so she started to write poetry, pieces of music, sonnets, ten-line stanzas and books. She first entered the Carmelite

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Ca ...

order, but decided to change to the Jerónimas in the Convento de San Jerónimo (Mexico City), which is now University of the Cloister of Sor Juana.

Her works included "Redondillas" and "Al que ingrato me deja" (To the one who ungratefully leaves me). She composed a poem which became a Christmas carol

A Christmas carol is a carol (a song or hymn) on the theme of Christmas, traditionally sung at Christmas itself or during the surrounding Christmas holiday season. The term noel has sometimes been used, especially for carols of French or ...

called "¡Ah de las mazmorras!" (Ah dungeons!). She was on the verge of condemnation by the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

, because at that time women were not thought fit to philosophize. There was presumed to be a lesbian

A lesbian is a Homosexuality, homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate n ...

relationship between Sor Juana and Viceroy María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga

María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, Marchioness of la Laguna, 11th Countess of Paredes (April 17, 1649 – September 4, 1721) was by birth member of the House of Gonzaga and Vicereine of New Spain by virtue of marriage.

Early life

She was ...

yet there was no certain evidence. It was also alleged that she was a feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, citing her accusations against men and her poems such as those mentioned above.

Sor Juana eventually retired from writing and poetry to devote herself to religious work. She became characterized by a famous phrase: "I, the worst of all." In 1695, an epidemic of plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

affected the capital of New Spain, including the Convento de San Jerónimo. Sor Juana helped care for the sick until she contracted the plague and died.

See also

* Baroque art in Mexico *Churrigueresque

Churrigueresque (; Spanish: ''Churrigueresco''), also but less commonly "Ultra Baroque", refers to a Spanish Baroque style of elaborate sculptural architectural ornament which emerged as a manner of stucco decoration in Spain in the late 17th ...

*Azulejo

''Azulejo'' (, ; from the Arabic ''al- zillīj'', ) is a form of Spanish and Portuguese painted tin-glazed ceramic tilework. ''Azulejos'' are found on the interior and exterior of churches, palaces, ordinary houses, schools, and nowadays, res ...

References

{{Spanish Colonial architecture Spanish art Spanish BaroqueNew Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the A ...

New Spain