National Party (South Africa) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The National Party ( af, Nasionale Party, NP), also known as the Nationalist Party, was a

The National Party was founded in

The National Party was founded in

There was some confusion about the republican ideal during the war years. The '' Herenigde Nasionale Party'', with Hertzog its leader, pushed the issue into the background. After Hertzog left the party, however, it became republican. In 1942 and 1944, Daniel François Malan introduced a motion in the House of Assembly in favour of the establishment of a republic, but this was defeated.

When the NP came to power in 1948 (making it the first all-Afrikaner cabinet since 1910), there were two uppermost priorities which it was determined to fulfill:

* Find a solution to the racial problem.

* Lead South Africa to independence and republican status.

Between 1948 and 1961, Prime Ministers

There was some confusion about the republican ideal during the war years. The '' Herenigde Nasionale Party'', with Hertzog its leader, pushed the issue into the background. After Hertzog left the party, however, it became republican. In 1942 and 1944, Daniel François Malan introduced a motion in the House of Assembly in favour of the establishment of a republic, but this was defeated.

When the NP came to power in 1948 (making it the first all-Afrikaner cabinet since 1910), there were two uppermost priorities which it was determined to fulfill:

* Find a solution to the racial problem.

* Lead South Africa to independence and republican status.

Between 1948 and 1961, Prime Ministers

Malan retired in 1954, at the age of eighty. The two succession contenders were J. G. Strijdom (Minister of Lands and Irrigation) and Havenga (Minister of Finance). Malan personally preferred the latter and, indeed, recommended him. Malan and Strijdom had clashed frequently over the years, particularly on the question of whether a republican South Africa should be inside or outside the Commonwealth.

Strijdom, however, had the support of Verwoerd and Ben Schoeman, and he was eventually voted in as Prime Minister. Strijdom was a passionate and outspoken Afrikaner and republican, and he wholeheartedly supported apartheid. He was completely intolerant towards non-Afrikaners and liberal ideas, utterly determined to maintain White rule, with zero compromise. Known as the "Lion of the North", Strijdom made few changes to his cabinet and pursued with vigour the policy of apartheid. By 1956, he successfully placed the Coloureds on a separate voters' roll, thus further weakening ties with the Commonwealth and gaining support for the NP.

He also took several other steps to make South Africa less dependent on Britain:

* In 1955, the South African parliament became recognised as the highest authority.

* In 1957, following a motion from Arthur Barlow MP, the flag of the Union of South Africa became the country's only flag; the Union Jack, alongside which the Union Flag had flown since 1928, was flown no longer, to be hoisted only on special occasions.

* Likewise, "

Malan retired in 1954, at the age of eighty. The two succession contenders were J. G. Strijdom (Minister of Lands and Irrigation) and Havenga (Minister of Finance). Malan personally preferred the latter and, indeed, recommended him. Malan and Strijdom had clashed frequently over the years, particularly on the question of whether a republican South Africa should be inside or outside the Commonwealth.

Strijdom, however, had the support of Verwoerd and Ben Schoeman, and he was eventually voted in as Prime Minister. Strijdom was a passionate and outspoken Afrikaner and republican, and he wholeheartedly supported apartheid. He was completely intolerant towards non-Afrikaners and liberal ideas, utterly determined to maintain White rule, with zero compromise. Known as the "Lion of the North", Strijdom made few changes to his cabinet and pursued with vigour the policy of apartheid. By 1956, he successfully placed the Coloureds on a separate voters' roll, thus further weakening ties with the Commonwealth and gaining support for the NP.

He also took several other steps to make South Africa less dependent on Britain:

* In 1955, the South African parliament became recognised as the highest authority.

* In 1957, following a motion from Arthur Barlow MP, the flag of the Union of South Africa became the country's only flag; the Union Jack, alongside which the Union Flag had flown since 1928, was flown no longer, to be hoisted only on special occasions.

* Likewise, "

Following the assassination of Verwoerd,

Following the assassination of Verwoerd,

In the midst of rising political instability, growing economic problems and diplomatic isolation, Botha resigned as NP leader, and subsequently as State President in 1989. He was replaced by

In the midst of rising political instability, growing economic problems and diplomatic isolation, Botha resigned as NP leader, and subsequently as State President in 1989. He was replaced by

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

founded in 1914 and disbanded in 1997. The party was an Afrikaner ethnic nationalist party that promoted Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Cast ...

interests in South Africa. However, in 1990 it became a South African civic nationalist party seeking to represent all South Africans. It first became the governing party of the country in 1924. It merged with its rival, the SAP, during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, and a splinter faction became the official opposition

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''t ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and returned to power and governed South Africa from 4 June 1948 until 9 May 1994.

Beginning in 1948 following the general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

, the party as the governing party of South Africa began implementing its policy of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

, known as apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

(the Afrikaans term for "separateness"). Although White-minority rule and racial segregation were already in existence in South Africa with non-Whites not having voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

and efforts made to encourage segregation, apartheid intensified the segregation with stern penalties for non-Whites entering into areas designated for Whites-only without having a pass to permit them to do so (known as the pass laws

In South Africa, pass laws were a form of internal passport system designed to segregate the population, manage urbanization and allocate migrant labor. Also known as the natives' law, pass laws severely limited the movements of not only blac ...

), interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different races or racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United States, Nazi Germany and apartheid-era South Africa as miscegenation. In 1 ...

and sexual relationships were illegal and punishable offences, and black people faced significant restrictions on property rights

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership) is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely and is typically h ...

. After South Africa was condemned by the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

for its policies of apartheid, the NP-led government had South Africa leave the Commonwealth, abandon its monarchy led by the British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

and become an independent republic.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the NP-led government faced internal unrest in South Africa and international pressure for accommodation of non-Whites in South Africa. It resulted in policies of granting concessions to the non-White population, while still retaining the apartheid system, such as the creation of Bantustan

A Bantustan (also known as Bantu homeland, black homeland, black state or simply homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa (n ...

s that were autonomous self-governing Black homelands (criticised for several of them being broken up into unconnected pieces and that they were still dominated by the White minority South African government), removing legal prohibitions on interracial marriage, and legalising non-White and multiracial political parties (however the outlawed though very popular African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

(ANC), was not legalised due to the government identifying it as a terrorist organisation). Those identified as Coloureds

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. Sou ...

and Indian South Africans

Indian South Africans are South Africans who descend from indentured labourers and free migrants who arrived from British India during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The majority live in and around the city of Durban, making it one of the ...

were granted separate legislatures in 1983 alongside the main legislature that represented Whites to provide them self-government while maintaining apartheid, but no such legislature was provided to the Black population as their self-government was to be provided through the Bantustans. The NP-led government began changing laws affected by the apartheid system that had come under heavy domestic and international condemnation such as removing the pass laws, granting Blacks full property rights that ended previous major restrictions on Black ownership of land, and the right to form trade unions. Following escalating economic sanctions over apartheid, negotiations between the NP-led government led by P. W. Botha and the outlawed ANC led by then-imprisoned Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

began in 1987 with Botha seeking to accommodate the ANC's demands and consider releasing Mandela and legalising the ANC on the condition that it would renounce use of political violence to attain its aims.

In the 1989 South African general election, the party under F. W. de Klerk's leadership declared that it intended to negotiate with the Black South African community for a political solution to accommodate Black South Africans. This resulted in De Klerk declaring in February 1990 the decision to transition South Africa out of apartheid, and permitted the release of Mandela from prison and ending South Africa's ban on the ANC and other anti-apartheid movements, and began negotiations with the ANC for a post-apartheid political system. In September 1990 the party opened up its membership to all racial groups and rebranded itself as no longer being an ethnic nationalist party only representing Afrikaners, but would henceforth be a civic nationalist and conservative party representing all South Africans. However, there was significant opposition among hardliner supporters of apartheid that resulted in De Klerk's government responding to them by holding a national referendum on Apartheid in 1992 for the White population alone that asked them if they supported the government's policy to end apartheid and establish elections open to all South Africans: a large majority voted in favour of the government's policy. In the 1994 elections it managed to expand its base to include many non-Whites, including significant support from Coloured and Indian South Africans. It participated in the Government of National Unity between 1994 and 1996. In an attempt to distance itself from its past, the party was renamed the New National Party in 1997. The attempt was largely unsuccessful and the new party was decided to merge with the ANC.

Founding and early history

Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein, ( ; , "fountain of flowers") also known as Bloem, is one of South Africa's three capital cities and the capital of the Free State province. It serves as the country's judicial capital, along with legislative capital Cape To ...

in 1914 by Afrikaner nationalists

Afrikaner nationalism ( af, Afrikanernasionalisme) is a nationalistic political ideology which created by Afrikaners residing in Southern Africa during the Victorian era. The ideology was developed in response to the significant events in Afri ...

soon after the establishment of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

. Its founding was rooted in disagreements among South African Party politicians, particularly Prime Minister Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer Wa ...

and his first Minister of Justice, J. B. M. Hertzog. After Hertzog began speaking out publicly against the Botha government's "one-stream" policy in 1912, Botha removed him from the cabinet. Hertzog and his followers in the Orange Free State province subsequently moved to establish the National Party to oppose the government by advocating a "two-stream" policy of equal rights for the English and Afrikaner communities. Afrikaner nationalists in the Transvaal and Cape provinces soon followed suit, so that three distinct provincial NP organisations were in existence in time for the 1915 general elections.

The NP first came to power in coalition with the Labour Party in 1924, with Hertzog as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

. In 1930 the Hertzog government worked to undermine the vote of Coloureds

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. Sou ...

(South Africans of mixed White and non-White ancestry) by granting the right to vote to White women, thus doubling White political power. In 1934, Hertzog agreed to merge his National Party with the rival South African Party of Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

to form the United Party. A hardline faction of Afrikaner nationalists led by Daniel François Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforce ...

refused to accept the merger and maintained a rump National Party called the ''Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party'' (Purified National Party

The Purified National Party ( af, Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party) was a break away from Hertzog's National Party which lasted from 1935 to 1948

In 1935 the main portion of the National Party, led by J. B. M. Hertzog, merged with the South African ...

). The Purified National Party used opposition to South African participation in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

to stir up anti-British feelings amongst Afrikaners. This led to a reunification of the Purified Nationalists with the faction that had merged with the South African Party; together they formed the '' Herenigde Nasionale Party'' (Reunited National Party), which went on to defeat Smuts' United Party in 1948 in coalition with the much smaller Afrikaner Party. In 1951, the two amalgamated to once again become known simply as the National Party.

Apartheid

Upon taking power after the 1948 general election, the NP began to implement a program of apartheid – the legal system of political, economic and social separation of the races intended to maintain and extend political and economic control of South Africa by the White minority. In 1959 the Bantu Self-Government Act established so-called Homelands (sometime pejoratively calledBantustans

A Bantustan (also known as Bantu homeland, black homeland, black state or simply homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa (now ...

) for ten different Black tribes. The ultimate goal of the NP was to move all Black South Africans into one of these homelands (although they might continue to work in South Africa as "guest workers"), leaving what was left of South Africa (about 87 percent of the land area) with what would then be a White majority, at least on paper. As the homelands were seen by the apartheid government as embryonic independent nations, all Black South Africans were registered as citizens of the homelands, not of the nation as a whole, and were expected to exercise their political rights only in the homelands. Accordingly, the three token parliamentary seats that had been reserved for White representatives of Black South Africans in the Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

were scrapped. The other three provinces – Transvaal Province

The Province of the Transvaal ( af, Provinsie van Transvaal), commonly referred to as the Transvaal (; ), was a province of South Africa from 1910 until 1994, when a new constitution subdivided it following the end of apartheid. The name "Trans ...

, the Orange Free State Province

The Province of the Orange Free State ( af, Provinsie Oranje-Vrystaat), commonly referred to as the Orange Free State ( af, Oranje-Vrystaat), Free State ( af, Vrystaat) or by its abbreviation OFS, was one of the four provinces of South Africa fro ...

, and Natal Province

The Province of Natal (), commonly called Natal, was a province of South Africa from May 1910 until May 1994. Its capital was Pietermaritzburg. During this period rural areas inhabited by the black African population of Natal were organized into ...

had never allowed any Black representation.

Coloureds

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. Sou ...

were removed from the Common Roll of Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

in 1953. Instead of voting for the same representatives as White South Africans, they could now vote only for four White representatives to speak for them. Later, in 1968, the Coloureds were disenfranchised altogether. In the place of the four parliamentary seats, a partially elected body was set up to advise the government in an amendment to the Separate Representation of Voters Act. This made the electorate entirely White, as Indian South Africans

Indian South Africans are South Africans who descend from indentured labourers and free migrants who arrived from British India during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The majority live in and around the city of Durban, making it one of the ...

had never had any representation.

In a move unrecognised by the rest of the world, the former German colony of South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

(now Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

), which South Africa had occupied in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, was effectively incorporated into South Africa as a League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

, with seven members elected to represent its White citizens in the Parliament of South Africa

The Parliament of the Republic of South Africa is South Africa's legislature; under the present Constitution of South Africa, the bicameral Parliament comprises a National Assembly and a National Council of Provinces. The current twenty-seve ...

. The White minority of South West Africa, predominantly Germans and Afrikaners, considered its interests akin to those of the Afrikaners in South Africa and therefore supported the National Party in subsequent elections.

These reforms all bolstered the NP politically, as they removed Black and Coloured influence – which was hostile to the NP – from the electoral process, and incorporated the pro-nationalist Whites of South-West Africa. The NP increased its parliamentary majority in almost every election between 1948 and 1977.

Numerous segregation laws had been passed before the NP took power in 1948. Among the most significant were the 'Natives Land Act, No 27 of 1913', and the 'Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923'. The former made it illegal for Blacks to purchase or lease land from Whites except in reserves, which restricted Black occupancy to less than eight percent of South Africa's land. The latter laid the foundations for residential segregation in urban areas. Apartheid laws passed by the NP after 1948 included the 'Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act', the 'Immorality Act', the 'Population Registration Act', and the 'Group Areas Act', which prohibited non-white males from being in certain areas of the country (especially at night) unless they were employed there.

From Dominion to republic

The NP was a strong advocate ofrepublicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

, a sentiment which was rooted in Boer history. Beginning in 1836, waves of Boers began to migrate north from the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

to live beyond the reach of the British colonial administration. Eventually, the migrating Boers founded three republics in southern Africa: the Natalia Republic

The Natalia Republic was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 after a Voortrekker victory against the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River. The area was previously named ''Natália'' by Portuguese sailors, due to its discovery on Christ ...

, the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

. British colonial expansion in the 19th century led to the annexation of the Natalia Republic

The Natalia Republic was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 after a Voortrekker victory against the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River. The area was previously named ''Natália'' by Portuguese sailors, due to its discovery on Christ ...

by Britain and the First and Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

s, which resulted in the South African Republic and the Orange Free State being annexed into the Empire as well.

Despite Britain's victory in the Second Boer War, Afrikaners continued to resist British control in southern Africa. In 1914, a group of anti-British Afrikaners led the Maritz rebellion against the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

; two years later, a NP congress called for South Africa to become a republic before changing its mind and deciding that it was too early. The ''Afrikaner Broederbond

The Afrikaner Broederbond (AB) or simply the Broederbond was an exclusively Afrikaner Calvinist and male secret society in South Africa dedicated to the advancement of the Afrikaner people. It was founded by H. J. Klopper, H. W. van der Merwe, ...

'', a secret organization founded in 1918 to support the interests of Afrikaners in South Africa, soon became a powerful force in the South African political scene. The Republican Bond was established in the 1930s, and other republican organisations such as the Purified National Party

The Purified National Party ( af, Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party) was a break away from Hertzog's National Party which lasted from 1935 to 1948

In 1935 the main portion of the National Party, led by J. B. M. Hertzog, merged with the South African ...

, the Voortrekkers, Noodhulpliga (First-Aid League) and the Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurverenigings (Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Organisations) also came into being. There was a popular outpouring of nationalist sentiment around the 1938 centenary of the Great Trek and the Battle of Blood River

The Battle of Blood River (16 December 1838) was fought on the bank of the Ncome River, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa between 464 Voortrekkers ("Pioneers"), led by Andries Pretorius, and an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Zulu. Es ...

. It was seen to signify the perpetuation of white South African culture, and anti-British and pro-republican feelings grew stronger.

It was obvious in political circles that the Union of South Africa was headed inexorably towards republicanism. Although it remained a Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

after unification in 1910, the country was granted increased amounts of self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

; indeed, it already had complete autonomy on certain issues. It was agreed in 1910 that domestic matters would be looked after by the South African government but that the country's external affairs would still remain British-controlled.

Hertzog's trip to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference was a definite (if failed) attempt to gain independence. In 1926, however, the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

was passed, affording every British dominion within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

equal rank and bestowing upon them their own right of direction of foreign issues. This resulted the following year in the institution of South Africa's first-ever Department of Foreign Affairs. 1931 saw a backtrack as the Statute of Westminster resolved that British Dominions could not have "total" control over their external concerns, but in 1934 the Status and Seals Acts were passed, granting the South African Parliament even greater power than the British government over the Union.

The extreme NP members of the 1930s were known collectively as the Republikeinse Bond. The following organisations, parties and events promoted the republican ideal in the 1930s:

* The Broederbond

The Afrikaner Broederbond (AB) or simply the Broederbond was an exclusively Afrikaner Calvinist and male secret society in South Africa dedicated to the advancement of the Afrikaner people. It was founded by H. J. Klopper, H. W. van der Merwe, ...

* The Purified National Party

The Purified National Party ( af, Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party) was a break away from Hertzog's National Party which lasted from 1935 to 1948

In 1935 the main portion of the National Party, led by J. B. M. Hertzog, merged with the South African ...

* The FAK

* The Voortrekkers and

* The 1938 Great Trek Centenary

* The

* The Ossewabrandwag

The ''Ossewabrandwag'' (OB) (, from af , ossewa , translation = ox-wagon and af , brandwag , translation = guard, picket, sentinel, sentry - ''Ox-wagon Sentinel'') was an anti-British and pro-German organisation in South Africa during Worl ...

* Pirow's (New Order)

* The adjustment to and the national flag

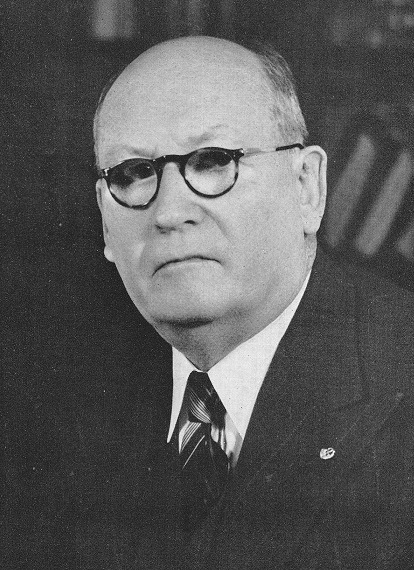

Daniel François Malan

There was some confusion about the republican ideal during the war years. The '' Herenigde Nasionale Party'', with Hertzog its leader, pushed the issue into the background. After Hertzog left the party, however, it became republican. In 1942 and 1944, Daniel François Malan introduced a motion in the House of Assembly in favour of the establishment of a republic, but this was defeated.

When the NP came to power in 1948 (making it the first all-Afrikaner cabinet since 1910), there were two uppermost priorities which it was determined to fulfill:

* Find a solution to the racial problem.

* Lead South Africa to independence and republican status.

Between 1948 and 1961, Prime Ministers

There was some confusion about the republican ideal during the war years. The '' Herenigde Nasionale Party'', with Hertzog its leader, pushed the issue into the background. After Hertzog left the party, however, it became republican. In 1942 and 1944, Daniel François Malan introduced a motion in the House of Assembly in favour of the establishment of a republic, but this was defeated.

When the NP came to power in 1948 (making it the first all-Afrikaner cabinet since 1910), there were two uppermost priorities which it was determined to fulfill:

* Find a solution to the racial problem.

* Lead South Africa to independence and republican status.

Between 1948 and 1961, Prime Ministers D. F. Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforce ...

, J. G. Strijdom and Hendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of '' Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

all worked very hard for the latter, implementing a battery of policies and changes in a bid to increase the country's autonomy. Divided loyalty, they felt, was holding South Africa back. They wanted to break the country's ties with the United Kingdom and establish a republic, and many South Africans grew confident that a republic was possible.

Unfortunately for its republicans, however, the NP was not in a strong parliamentary position. Although it held a majority (only five) of seats, a large number of these were in rural constituencies, which had far fewer voters than urban constituencies. Malan appealed to many rural voters due to his agricultural policy, meaning black workers relied on white farmers for work, fuelling his quest for a segregated nation. The United Party held a 100,000-vote lead. Consequently, the NP had to rely on the Afrikaner Party's support. It did not, therefore, have the groundswell of public support that it needed to win a referendum, and only when it had that majority on its side could a referendum be held on the republican matter. However, with a small seating majority and a total vote-tally minority, it was impossible for now for Malan and his ardently republican Nats to bring about a republic constitutionally. In the interim, the NP would have to consolidate itself and not antagonise the British.

Many English-speakers did not want to break their ties with the United Kingdom. However, in 1949, at the 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference

The 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference was the fourth meeting of the Heads of government of the Commonwealth of Nations. It was held in the United Kingdom in April 1949 and was hosted by that country's prime minister, Clement Attlee.

...

in London (with Malan in attendance), India requested that, in spite of its newly attained republican status, it remain a member of the British Commonwealth. When this was granted the following year by the London Declaration

The London Declaration was a declaration issued by the 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference on the issue of India's continued membership of the Commonwealth of Nations, an association of independent states formerly part of the British ...

, it roused a great deal of debate in South Africa between the pro-republican NP and the anti-republican UP (under Strauss). What it meant was that, even if South Africa did become a republic, it did not automatically have to sever all of its ties with the UK and the British Commonwealth. This gained the movement further support from the English-speaking populace, which was less worried about being isolated; and the republican ideal looked closer than ever to being fulfilled.

Although he could not yet make South Africa a republic, Malan could prepare the country for this eventuality. In his term of office, from 1948 to 1954, Malan took a number of steps to break ties with the UK:

* The South African Citizenship Act was passed in 1949. Before, South Africans had not been citizens but rather subjects of the British Crown, regardless of whether they were permanent residents or had only recently migrated. The 1949 Act established South African citizenship. Before, British citizens needed a mere two years in the country to qualify as South Africans; now, however, British immigrants were just like any other immigrant: they would have to register and remain in South Africa for five years to become citizens of the country. It was believed that this could well have an influence on a republican referendum. The Act ensured that the British immigrant population would not reduce the Afrikaner majority.

* In 1950, the right of appeal to the British Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

in London was terminated under the Privy Council Appeals Act. The Appellate Division of the Supreme Court in Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein, ( ; , "fountain of flowers") also known as Bloem, is one of South Africa's three capital cities and the capital of the Free State province. It serves as the country's judicial capital, along with legislative capital Cape To ...

was now South Africa's highest court.

* Malan was a crucial player in the move to get the word "British" taken away from "British Commonwealth". This change was taken as affirmation of the fact that all member countries were voluntary and equal members.

* In 1951, pro-republican Ernest George Jansen was assigned the post of Governor-General of South Africa

The governor-general of the Union of South Africa ( af, Goewerneur-generaal van Unie van Suid-Afrika, nl, Goeverneur-generaal van de Unie van Zuid-Afrika) was the highest state official in the Union of South Africa between 31 May 1910 and 31 ...

. This endorsed the idea of Afrikaner leadership.

* The title of the just-crowned Queen was modified in 1953 from "Elizabeth II, Queen of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the Seas" to "Elizabeth II, Queen of South Africa". This was meant to indicate that the South African upper house had bequeathed the title upon her.

The 1953 ballot votes saw the NP fortify its position considerably, winning comfortably but still falling well short of the clear majority it sought: it had 94 seats in parliament to the UP's 57 and the Labour Party's five.

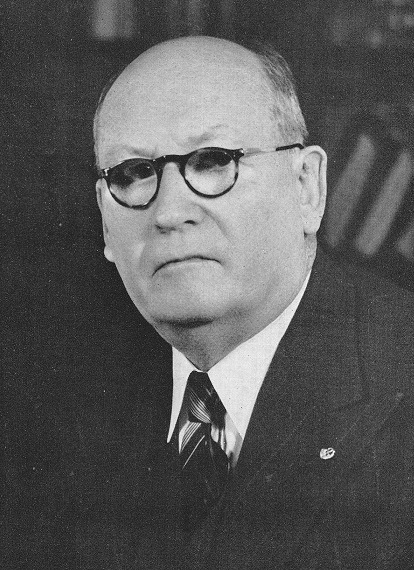

J. G. Strijdom

Malan retired in 1954, at the age of eighty. The two succession contenders were J. G. Strijdom (Minister of Lands and Irrigation) and Havenga (Minister of Finance). Malan personally preferred the latter and, indeed, recommended him. Malan and Strijdom had clashed frequently over the years, particularly on the question of whether a republican South Africa should be inside or outside the Commonwealth.

Strijdom, however, had the support of Verwoerd and Ben Schoeman, and he was eventually voted in as Prime Minister. Strijdom was a passionate and outspoken Afrikaner and republican, and he wholeheartedly supported apartheid. He was completely intolerant towards non-Afrikaners and liberal ideas, utterly determined to maintain White rule, with zero compromise. Known as the "Lion of the North", Strijdom made few changes to his cabinet and pursued with vigour the policy of apartheid. By 1956, he successfully placed the Coloureds on a separate voters' roll, thus further weakening ties with the Commonwealth and gaining support for the NP.

He also took several other steps to make South Africa less dependent on Britain:

* In 1955, the South African parliament became recognised as the highest authority.

* In 1957, following a motion from Arthur Barlow MP, the flag of the Union of South Africa became the country's only flag; the Union Jack, alongside which the Union Flag had flown since 1928, was flown no longer, to be hoisted only on special occasions.

* Likewise, "

Malan retired in 1954, at the age of eighty. The two succession contenders were J. G. Strijdom (Minister of Lands and Irrigation) and Havenga (Minister of Finance). Malan personally preferred the latter and, indeed, recommended him. Malan and Strijdom had clashed frequently over the years, particularly on the question of whether a republican South Africa should be inside or outside the Commonwealth.

Strijdom, however, had the support of Verwoerd and Ben Schoeman, and he was eventually voted in as Prime Minister. Strijdom was a passionate and outspoken Afrikaner and republican, and he wholeheartedly supported apartheid. He was completely intolerant towards non-Afrikaners and liberal ideas, utterly determined to maintain White rule, with zero compromise. Known as the "Lion of the North", Strijdom made few changes to his cabinet and pursued with vigour the policy of apartheid. By 1956, he successfully placed the Coloureds on a separate voters' roll, thus further weakening ties with the Commonwealth and gaining support for the NP.

He also took several other steps to make South Africa less dependent on Britain:

* In 1955, the South African parliament became recognised as the highest authority.

* In 1957, following a motion from Arthur Barlow MP, the flag of the Union of South Africa became the country's only flag; the Union Jack, alongside which the Union Flag had flown since 1928, was flown no longer, to be hoisted only on special occasions.

* Likewise, "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika

Die Stem van Suid-Afrika (, ), also known as "The Call of South Africa" or simply "Die Stem" (), is a former national anthem of South Africa. There are two versions of the song, one in English and the other in Afrikaans, which were in use earl ...

" (The Call of South Africa) became South Africa's only national anthem and was also translated into English to appease the relevant population. God Save the Queen

"God Save the King" is the national and/or royal anthem of the United Kingdom, most of the Commonwealth realms, their territories, and the British Crown Dependencies. The author of the tune is unknown and it may originate in plainchant, bu ...

would be sung only on occasions relating to the UK or the Commonwealth.

* In 1957, the maritime base in Simonstown was reassigned from the command of the British Royal Navy to that of the South African government. The British had occupied Simonstown since 1806.

* In 1958, " OHMS" was replaced by "Official" on all official documents.

* C. R. Swart

Charles Robberts Swart (5 December 1894 – 16 July 1982), nicknamed ''Blackie'', was a South African politician who served as the last governor-general of the Union of South Africa from 1959 to 1961 and the first state president of the Republi ...

, another staunch Afrikaner republican, became the new Governor-General.

Anti-republican South Africans recognised the shift and distancing from Britain, and the UP grew increasingly anxious, doing all that it could to persuade Parliament to retain Commonwealth links. Strijdom, however, declared that South Africa's participation (or otherwise) in the Commonwealth would be determined only by its best interests.

Hendrik Verwoerd

The question of apartheid dominated the 1958 election and the NP took 55% of the vote, thus winning a clear majority for the first time. When Strijdom died that same year, there was a tripartite succession contest between Swart, Dönges and Verwoerd. The latter, devoted to the cause of a republican South Africa, was the new Prime Minister. Verwoerd, a former Minister of Native Affairs, played a leading role in the institution of the apartheid system. Under his leadership, the NP solidified its control over South African apartheid-era politics. To gain support of the English-identified population of South Africa, Verwoerd appointed several English-speakers to his cabinet. He also cited the radical political movements elsewhere in the African continent as vindication of his belief that White and Black nationalism could not work within the same system. Verwoerd also presented the NP as the party best equipped to deal with the widely perceived threat of communism. By the end of his term (caused by his assassination), Verwoerd had solidified the NP's domination of South African politics. In the 1966 elections the party won 126 out of the 170 seats in Parliament. By 1960, however, much of the South African electorate were calling for withdrawal from the Commonwealth and the establishment of South Africa as a republic. It was decided that a republican referendum was to be held in October. International circumstances made the referendum a growing necessity. In the aftermath of theWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, former British colonies in Africa and Asia were gaining independence and publicising the ills of apartheid. Commonwealth members were determined to isolate South Africa.

There were numerous internal factors which had paved the way for and may be viewed as influences on the result:

* Harold Macmillan's " Winds of Change" speech, in which he declared that independence for Black Africans was an inevitability;

* Many Whites were unwilling to give up apartheid and realised that South Africa would have to go for it alone if it was to pursue its racial policies.

* The assertion that economic growth and a relaxation of racial tensions could be achieved only through a republic;

* The Sharpeville Massacre

The Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960 at the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa (today part of Gauteng). After demonstrating against pass laws, a crowd ...

;

* The attempted assassination of Verwoerd; and, most importantly,

* The 1960 census, which revealed that there were more Afrikaners in the country than English, thus almost guaranteeing the NP victory in a republican referendum.

The opposition accused Verwoerd of trying to break from the Commonwealth and the west, thus losing South Africa all of its trade preferences. The NP, however, launched a vigorously enthusiastic political campaign, with widely advertised public meetings. The opposition found it very difficult to fight for the preservation of British links.

There were numerous pro-republican arguments:

* It would link more closely the two European language groups.

* It would eliminate confusion about South Africa's constitutional position.

* The monarchy was essentially a British one, with no roots in South Africa.

* South Africans desired a home-grown Head of State.

* The Queen of South Africa, living abroad, inherited her title as the United Kingdom's monarch without the assistance or approval of South Africa.

* In a republic, the Head of State would not be another country's ruler but rather the elected representative of the nation, a unifying symbol.

* A republic symbolised a sovereign free and independent state.

* South Africa would be able to approach its internal problems more realistically, since they would be strictly "South African" problems to be solved by South Africans rather than foreign intervention.

* It would clear the misconception amongst many Blacks in South Africa that foreigners had the final say in their affairs.

There were also numerous arguments the establishment of a republic:

* It could lead to a forced withdrawal from the Commonwealth.

* With the entire world in a state of political unrest, bordering on turmoil, it was dangerous to change South Africa's political status.

* It could lead to isolation from allies.

* A republic would solve none of South Africa's problems; it would only make them worse, especially the racial problem, to which the Commonwealth was increasingly opposed.

* The NP had supposedly not given one good reason for the change.

* The ruling party already had twelve years to bring about national unity but had only driven the two White sects further apart.

* A republic could be established by a majority of just one vote. This did not entail unity nor, indeed, democracy.

* Countries did not generally change their form of government unless the present form was inefficient or unstable due to internal strife or hardship. Nothing like this had happened in (White) South Africa, where so many were so content.

On 5 October 1960, 90.5% of the White electorate turned out to vote on the issue. 850,458 (52%) voted in favour of a republic, while 775,878 were against it. The Cape, Orange Free State and Transvaal were all in favour; Natal, a mainly English-speaking province, was not. It was a narrow victory for the republicans. However, a considerable number of Afrikaners did vote against the measure. The few Blacks, Indians and Coloureds allowed to vote were decidedly against the measure.

English-speakers who voted for a republic had done so on condition that their cultural heritage be safeguarded. Many had associated a republic with the survival of the White South Africans. Macmillan's speech had illustrated that the British government was no longer prepared to stand by South Africa's racist policies. Nevertheless, the referendum was a significant victory for Afrikaner nationalism as British political and cultural influence waned in South Africa.

However, one question remained after the referendum: would South Africa become a republic outside the Commonwealth (the outcome favoured by the most Afrikaner nationalists)? Withdrawal from the Commonwealth would likely alienate English-speakers and damage relations with many other countries. Former British colonies such as India, Pakistan and Ghana were all republics within the Commonwealth, and Verwoerd announced that South Africa would follow suit "if possible".

In January 1961, Verwoerd's government brought forth legislation to transform the Union of South Africa into the Republic of South Africa. The constitution was finalised in April. It merged the authority of the British Crown and Governor-General into a new post, State President of South Africa

The State President of the Republic of South Africa ( af, Staatspresident) was the head of state of South Africa from 1961 to 1994. The office was established when the country became a republic on 31 May 1961, albeit, outside the Commonweal ...

. The State President would have rather little political power, serving more as the ceremonial head of state. The political power was to lie with the Prime Minister (head of government). The Republic of South Africa would also have its own monetary system, employing Rand and Cents.

In March 1961, Verwoerd visited the 1961 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference

The 1961 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference was the 11th Meeting of the Heads of Government of the Commonwealth of Nations. It was held in the United Kingdom in March 1961, and was hosted by that country's Prime Minister, Harold Macmilla ...

in London to discuss South Africa becoming a republic within the Commonwealth, presenting the Republic of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countr ...

's application for a renewal of its membership to the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth had earlier declined to predict how republican status would affect South Africa's membership, it did not want to be seen to be meddling in its members' domestic affairs. However, many of the Conference's affiliates (prominent among them the Afro-Asia group and Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker) attacked South Africa's racial policies and rebuffed Verwoerd's application; they would go to any lengths to expel South Africa from the Commonwealth. In the UK, numerous anti-apartheid movements were also campaigning for South Africa's exclusion. Some member countries warned that, unless South Africa was expelled, they would themselves pull out of the organisation. Verwoerd disregarded the censure, arguing that his Commonwealth cohorts had no right to question and criticise the domestic affairs of his country. On this issue, he even had the support of his parliamentary opposition.

Thus, on 15 March 1961, ostensibly to Britain an awkward decision and causing a split within the Commonwealth, but more likely to avoid further condemnation and embarrassment, Verwoerd withdrew his application and announced that South Africa would become a republic outside the Commonwealth. His decision was received with regret by the Prime Ministers of the UK, Australia and New Zealand, but was met with obvious approval from South Africa's critics. Verwoerd issued a statement the next day to the effect that the move would not affect South Africa's relationship with the United Kingdom. On his homecoming, he was met with a rapturous reception. Afrikaner nationalists were not at all deterred by the relinquishment of Commonwealth membership, for they regarded the Commonwealth as little more than the British Empire in disguise. They believed that South Africa and the United Kingdom had absolutely nothing in common, and even UP leader Sir De Villiers Graaff praised Verwoerd for his handling of the situation.

On 31 May 1961, South Africa became a republic. The date was a significant one in Afrikaner history, as it heralded the anniversary of a number of historical events, the 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging, which ended the Anglo-Boer War; South Africa's becoming a union in 1910; and the first hoisting of the Union flag in 1928. The Afrikaner republican dream had finally come to reality.

The significance of Commonwealth withdrawal turned out to be less than had been expected. It was not necessary for South Africa to amend its trading preferences, and Prime Minister Macmillan reciprocated Verwoerd's assurance that withdrawal would not alter trade between South Africa and the UK.

South Africa had now its first independent constitution, although the only real constitutional change was that the State President, in charge for seven years, would assume the now-vacant position of the Queen as Head of State. C. R. Swart

Charles Robberts Swart (5 December 1894 – 16 July 1982), nicknamed ''Blackie'', was a South African politician who served as the last governor-general of the Union of South Africa from 1959 to 1961 and the first state president of the Republi ...

, the State President elect, took the first republican oath as State President of South Africa

The State President of the Republic of South Africa ( af, Staatspresident) was the head of state of South Africa from 1961 to 1994. The office was established when the country became a republic on 31 May 1961, albeit, outside the Commonweal ...

before Chief Justice L.C. Steyn (DRC).

Although White inhabitants were generally happy with the republic, united in their support of Verwoerd, the Blacks defiantly rejected the move. Nelson Mandela and his National Action Council demonstrated from 29 to 31 May 1961. The republican issue would strongly intensify resistance to apartheid.

Support

The NP won a majority of parliamentary seats in all elections during the apartheid era. Its popular vote record was more mixed: While it won the popular vote with a comfortable margin in most general elections, the NP carried less than 50% of the electorate in 1948, 1953, 1961, and 1989. In 1977, the NP got its best-ever result in the elections with support of 64.8% of the White voters and 134 seats in parliament out of 165. After this the party's support declined as a proliferation of right wing parties siphoned off important segments of its traditional voter base. Throughout its reign, the party's support came mainly fromAfrikaners

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Cas ...

, but other White people were courted by and increasingly voted for the NP after 1960. By the 1980s however, in reaction to the "verligte" reforms of P. W. Botha, the majority of Afrikaners drifted to the Conservative Party of Andries Treurnicht

Andries Petrus Treurnicht (19 February 1921 – 22 April 1993) was a South African politician, Minister of Education during the Soweto Riots and for a short time leader of the National Party in Transvaal. In 1982 he founded and led the Conse ...

, who called for a return to the traditional policies of the NP. In the 1974 general elections for example 91% of Afrikaners voted for the NP; however, in the 1989 general elections, only 46% of Afrikaners cast their ballot for the National party.

Division and decline

Factional warfare: "''Verkramptes"'' and "''Verligtes"''

Following the assassination of Verwoerd,

Following the assassination of Verwoerd, John Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

took over as party leader and Prime Minister. From the 1960s onwards, the NP and the Afrikaner population in general was increasingly divided over the application of apartheid (the legal opposition being similarly divided over its response), leading to the emergence of the "''verkramptes''" and "''verligtes''". ''Verkramptes'' were members of the party's right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

who opposed any deviation from the rigid apartheid structure. ''Verligtes'' took a somewhat more moderate stance towards racial issues, primarily from a pragmatic standpoint over fears of international scrutiny should reforms fail to be made.

In addition to the question of apartheid, the two factions were divided over such issues as immigration, language, racially-mixed sporting teams, and engagement with Black African states. In 1969, members of the "''verkrampte''" faction including Albert Hertzog

Johannes Albertus Munnik Hertzog (; 4 July 1899, Bloemfontein – 5 November 1982, Pretoria) was an Afrikaner politician, cabinet minister, and founding leader of the Herstigte Nasionale Party. He was the son of J. B. M. (Barry) Hertzog, a form ...

and Jaap Marais

Jacob Albertus Marais (2 November 1922 – 8 August 2000) was an Afrikaner nationalist thinker, author, politician, Member of Parliament, and leader of the Herstigte Nasionale Party (HNP) from 1977 till his death in 2000. Marais is the longest ...

, formed the '' Herstigte Nasionale Party'', which claimed to be the true upholder of pure Verwoerdian apartheid ideology and continues to exist today. While it never had much electoral success, it attracted sufficient numbers to erode support for the government at crucial points, although not to the extent that the Conservative Party would do. Meanwhile, the ''verligtes'' began to gain some traction inside the party in response to growing international opposition to apartheid.

Perhaps a precursor to the split came around 1960 when Japie Basson, a moderate, was expelled for disagreements on racial questions and would form his own National Union Party, he would later join the United Party and Progressive Federal Party before rejoining the NP in the 1980s. Former Interior Minister Theo Gerdener formed the Democratic Party in 1973 to attempt its own verligte solution to racial questions.

National Party under Botha

Beginning in the early 1980s, under the leadership ofPieter Willem Botha

Pieter Willem Botha, (; 12 January 1916 – 31 October 2006), commonly known as P. W. and af, Die Groot Krokodil (The Big Crocodile), was a South African politician. He served as the last prime minister of South Africa from 1978 to 1984 an ...

, Prime Minister since 1978, the NP began to reform its policies. Botha legalised interracial marriages and multiracial political parties and relaxed the Group Areas Act

Group Areas Act was the title of three acts of the Parliament of South Africa enacted under the apartheid government of South Africa. The acts assigned racial groups to different residential and business sections in urban areas in a system o ...

. Botha also amended the constitution to grant a measure of political representation to Coloureds and Indians by creating separate parliamentary chambers in which they had control of their "own affairs". The amendments also replaced the parliamentary system with a presidential one. The powers of the Prime Minister were essentially merged with those of the State President

The State President of the Republic of South Africa ( af, Staatspresident) was the head of state of South Africa from 1961 to 1994. The office was established when the country became a republic on 31 May 1961, albeit, outside the Commonweal ...

, which was vested with sweeping executive powers. Although portraying the new system as a power-sharing agreement, Botha ensured that the real power remained in White hands, and in practice, in the hands of the NP. Whites had large majorities in the electoral college which chose the State President, as well as on the President's Council, which settled disputes between the three chambers and decided which combination of them could consider any piece of legislation. However, Botha and the NP refused to budge on the central issue of granting meaningful political rights to Black South Africans, who remained unrepresented even after the reforms. Most Black political organisations remained banned, and prominent Black leaders, including Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

, remained imprisoned.

While Botha's reforms did not even begin to meet the opposition's demands, they sufficiently alarmed a segment of his own party to engender a second split. In 1982, hardline NP members including Andries Treurnicht

Andries Petrus Treurnicht (19 February 1921 – 22 April 1993) was a South African politician, Minister of Education during the Soweto Riots and for a short time leader of the National Party in Transvaal. In 1982 he founded and led the Conse ...

and Ferdinand Hartzenberg formed the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, committed to reversing Botha's reforms, which by 1987 became the largest parliamentary opposition party. The party later merged into the Freedom Front, which today represents Afrikaner nationalism. On the other hand, some reformist NP members also left the party, such as Dennis Worrall and Wynand Malan

Wynand Malan (born 25 May 1943) is a liberal Afrikaner South African politician.

A lawyer, Malan entered politics in the 1977 South African election when he was elected to the South Africa's all white parliament as the National Party MP for ...

, who formed the Independent Party which later merged into the Democratic Party (a similar breakaway group existed for a time in the 1970s). The loss of NP support to both the DP and CP reflected the divisions among White voters over continued maintenance of apartheid.

National Party under de Klerk and final years of apartheid

In the midst of rising political instability, growing economic problems and diplomatic isolation, Botha resigned as NP leader, and subsequently as State President in 1989. He was replaced by

In the midst of rising political instability, growing economic problems and diplomatic isolation, Botha resigned as NP leader, and subsequently as State President in 1989. He was replaced by F. W. de Klerk

Frederik Willem de Klerk (, , 18 March 1936 – 11 November 2021) was a South African politician who served as state president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and as deputy president from 1994 to 1996 in the democratic government. As South ...

in this capacity. Although conservative by inclination, De Klerk had become the leader of an "enlightened" NP faction that realised the impracticality of maintaining apartheid forever. He decided that it would be better to negotiate while there was still time to reach a compromise, than to hold out until forced to negotiate on less favourable terms later. He persuaded the NP to enter into negotiations with representatives of the Black community. Late in 1989, the NP won the most bitterly contested election in decades, pledging to negotiate an end to the very apartheid system that it had established.

On 2 February 1990, the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

was legalised, and Nelson Mandela was released after twenty-seven years of imprisonment. In the same year, the NP opened its membership to all racial groups and moves began to repeal the racial legislation which had been the foundations of apartheid. A referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

in 1992 gave De Klerk plenipotentiary powers to negotiate with Mandela. Following the negotiations, a new interim constitution was drawn up, and non-racial democratic elections were held in 1994. These elections were won by the African National Congress. The NP remained in government, however, as a coalition partner to the ANC in the Government of National Unity until 30 June 1996, when it withdrew to become the official opposition.

Post-apartheid era

The NP won 20.39% of the vote and 82 seats in the National Assembly at the first multiracial election in 1994. This support extended well beyond the White community and into other minority groups. For instance, two-thirds ofIndian South Africans

Indian South Africans are South Africans who descend from indentured labourers and free migrants who arrived from British India during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The majority live in and around the city of Durban, making it one of the ...

voted for the NP. It became the official opposition in most provinces and also won a majority in the Western Cape, winning much of the White and Coloured vote. Its Coloured support also earned it a strong second place in the Northern Cape. The party was wracked by internal wranglings whilst it participated in the Government of National Unity, and finally withdrew from the government to become the official opposition in 1996. Despite this, it remained uncertain about its future direction, and was continually outperformed in parliament by the much smaller Democratic Party (DP), which provided a more forceful and principled opposition stance. In 1997, its voter base began to gradually shift to the DP. The NP renamed itself the New National Party towards the end of 1997, to distance itself from the apartheid past.

However, the NNP would quickly disappear from the political scene, faring poorly at both the 1999 and 2004 general elections. Going back and forth on whether to oppose or work with the ANC, the two finally formed an alliance in late-2001. After years of losing members and support to other parties, the NNP's collapse in its previous stronghold in the Western Cape at the 2004 general election proved to be the final straw; its federal council voted to dissolve the party on 9 April 2005, following a decision the previous year to merge with the ANC.

Re-establishment

On 5 August 2008 a new party using the name of "National Party South Africa" was formed and registered with theIndependent Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

. The new party had no formal connection with the now defunct New National Party. The relaunched National Party of 2008 pushes for a non-racial democratic South Africa based on federal principles and the legacy of F. W. de Klerk

Frederik Willem de Klerk (, , 18 March 1936 – 11 November 2021) was a South African politician who served as state president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and as deputy president from 1994 to 1996 in the democratic government. As South ...

.

List of presidents

Electoral history

State Presidential elections

House of Assembly elections

Senate elections

References

{{Authority control Apartheid in South Africa Politics and race Far-right politics in South Africa Fascism in South Africa Political parties established in 1914 Political parties disestablished in 1997 Civic nationalism Christian democratic parties in South Africa Anti-communist parties Conservative parties in South Africa Political parties of minorities Protestant political parties Republicanism in South Africa 20th century in South Africa Political history of South Africa White supremacy in South Africa Afrikaner nationalism Ethnic nationalism White nationalist parties