Ascalon or Ashkelon was an

ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

port city on the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

coast of the

southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a geographical region that corresponds approximately to present-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southern Syria and the Sinai Peninsula. As a strictly geographical descript ...

of high historical and archaeological significance. Its remains are located in the archaeological site of Tel Ashkelon, within the city limits of the modern

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

i city of

Ashkelon

Ashkelon ( ; , ; ) or Ashqelon, is a coastal city in the Southern District (Israel), Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv, and north of the border with the Gaza Strip.

The modern city i ...

. Traces of settlement exist from the

3rd millennium BCE, with evidence of city fortifications emerging in the

Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

. During the

Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, it was integrated into the

Egyptian Empire

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties. Through radioc ...

, before becoming one of the five cities of the

Philistine pentapolis following the migration of the

Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

. The city was later destroyed by the

Babylonians

Babylonia (; , ) was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as an Akkadian-populated but Amorite-ru ...

but was subsequently rebuilt.

Ascalon remained a major metropolis throughout the classical period, as a

Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

city persisting into the

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

period. Christianity began to spread in the city as early as the 4th century CE. During the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

it came under Islamic rule, before becoming a highly contested fortified foothold on the coast during the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

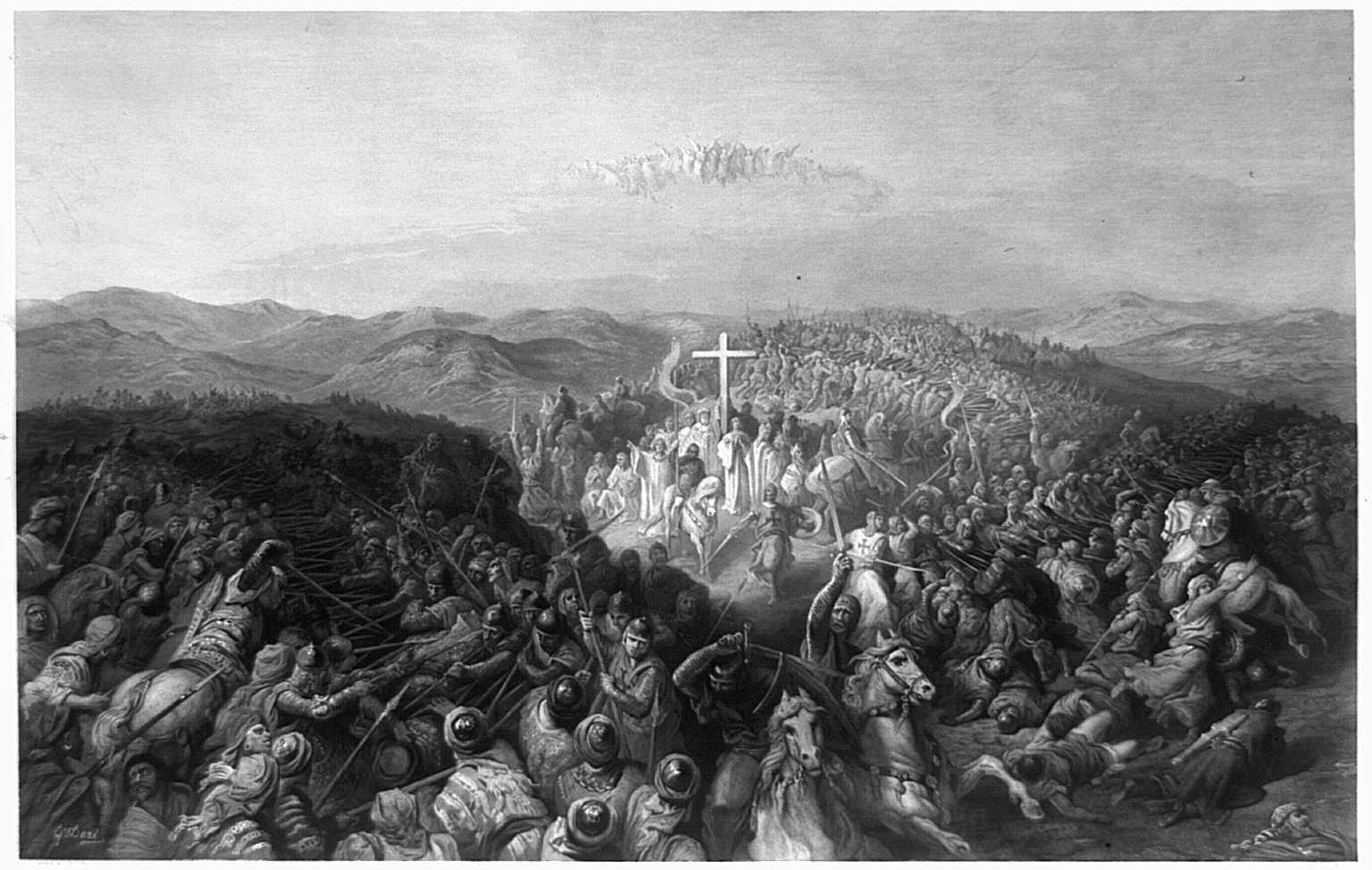

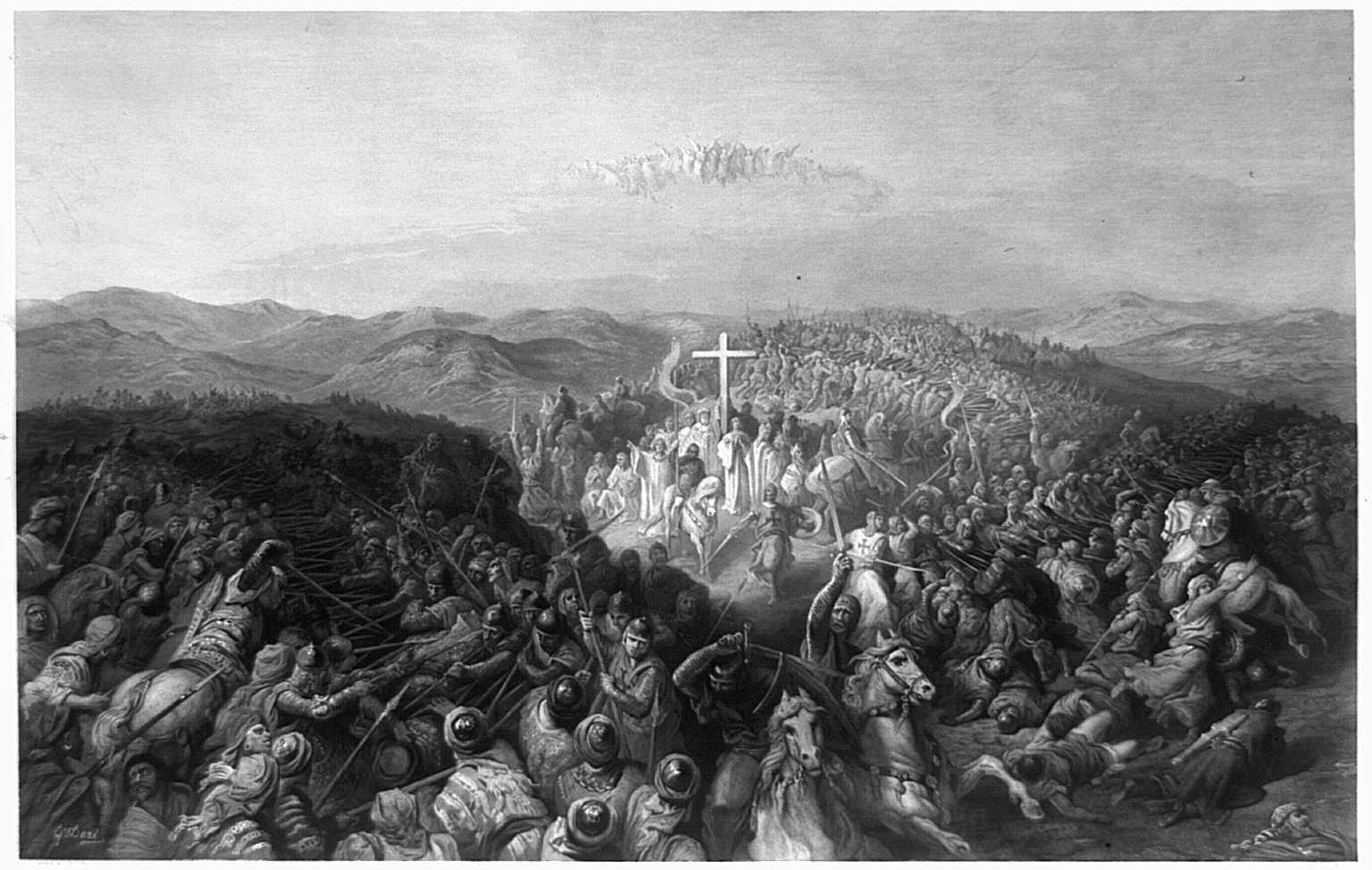

. Two significant Crusader battles took place in the city: the

Battle of Ascalon

The Battle of Ascalon took place on 12 August 1099 shortly after the capture of Jerusalem, and is often considered the last action of the First Crusade. The crusader army led by Godfrey of Bouillon defeated and drove off a Fatimid army.

The ...

in 1099, and the

Siege of Ascalon

The siege of Ascalon took place from 25 January to 22 August 1153, in the time period between the Second Crusade, Second and Third Crusades, and resulted in the capture of the Fatimid Egyptian fortress by the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Ascalon was an i ...

in 1153. The Mamluk sultan

Baybars

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari (; 1223/1228 – 1 July 1277), commonly known as Baibars or Baybars () and nicknamed Abu al-Futuh (, ), was the fourth Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria, of Turkic Kipchak origin, in the Ba ...

ordered the destruction (

slighting

Slighting is the deliberate damage of high-status buildings to reduce their value as military, administrative, or social structures. This destruction of property is sometimes extended to the contents of buildings and the surrounding landscape. It ...

) of the city fortifications and the harbour in 1270 to prevent any further military use, though structures such as the

Shrine of Husayn's Head survived. The nearby town of

al-Majdal was established in the same period. The village of

Al-Jura

Al-Jura () was a Palestinian village that was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, located immediately adjacent to the towns of Ashkelon and the ruins of ancient Ascalon. In 1945, the village had a population of approximately 2,420 mostl ...

existed adjacent to the deserted city until 1948.

Names

Ascalon has been known by many variations of the same basic name over the millennia. It is speculated that the name comes from the

Northwest Semitic

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic language, Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite l ...

and possibly

Canaanite root Ṯ-Q-L, meaning "to weigh", which is also the root of "

shekel

A shekel or sheqel (; , , plural , ) is an ancient Mesopotamian coin, usually of silver. A shekel was first a unit of weight—very roughly 11 grams (0.35 ozt)—and became currency in ancient Tyre, Carthage and Hasmonean Judea.

Name

The wo ...

".

The settlement is first mentioned in the

Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

Execration Texts

Execration texts, also referred to as proscription lists, are ancient Egyptian hieratic texts, listing enemies of the pharaoh, most often enemies of the Egyptian state or troublesome foreign neighbors. The texts were most often written upon stat ...

from the 18th-19th centuries BCE as .

[ In the Amarna letters ( 1350 BCE), there are seven letters to and from King Yidya of and the ]Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

. The Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah, is an inscription by Merneptah, a pharaoh in ancient Egypt who reigned from 1213 to 1203 BCE. Discovered by Flinders Petrie at Thebes, Egypt, Thebes in 1896, i ...

(c. 1208 BCE) of the 19th dynasty recounts the Pharaoh putting down a rebellion at .[ The settlement is then mentioned eleven times in the ]Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

. '' Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, emerged as the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

name for the city, persisting through the Roman period

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

and later Byzantine period

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

.

In the Early Islamic period

The historiography of early Islam is the secular scholarly literature on the early history of Islam during the 7th century, from Muhammad's first purported revelations in 610 until the disintegration of the Rashidun Caliphate in 661,

and arguab ...

, the Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

form became . The medieval Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding ...

called it Ascalon.

In modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew (, or ), also known as Israeli Hebrew or simply Hebrew, is the Standard language, standard form of the Hebrew language spoken today. It is the only surviving Canaanite language, as well as one of the List of languages by first w ...

it is known as . Today, Ascalon is a designated archaeological area known as Tel Ashkelon ("Mound

A mound is a wikt:heaped, heaped pile of soil, earth, gravel, sand, rock (geology), rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded ...

of Ascalon") and administered as Ashkelon National Park.

Geographical setting

Ascalon lies on the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

coast, 16 km. north of Gaza City

Gaza City, also called Gaza, is a city in the Gaza Strip, Palestine, and the capital of the Gaza Governorate. Located on the Mediterranean coast, southwest of Jerusalem, it was home to Port of Gaza, Palestine's only port. With a population of ...

and 14 km. south of Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

and Ashdod-Yam

Ashdod-Yam or Azotus Paralios (lit. Ashdod/Azotus-on-the-sea") is an archaeological site on the Mediterranean coast of Israel. It is located in the southern part of the modern city of Ashdod, and about 5 kilometres northwest of the ancient sit ...

. Around 15 million years ago

Million years ago, abbreviated as Mya, Myr (megayear) or Ma (megaannum), is a unit of time equal to (i.e. years), or approximately 31.6 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used w ...

, a river flowed from inland to the sea here. It was later covered by fossilized sandstone ridges (kurkar), formed by sand that was washed to the shores from the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

. The river became an underground water source, which was later exploited by Ascalon's residents for the constructions of wells. The oldest well found at Ascalon dates around 1000 BCE.

Prehistory

The remains of prehistoric activity and settlement at Ashkelon were revealed in salvage excavations prior to urban development in the Afridar and Marina neighborhoods of modern Ashkelon, some north of Tel Ashkelon. The fieldwork was conducted in the 1950s under the supervision of Jean Perrot and in 1997–1998 under the supervision of Yosef Garfinkel

Yosef Garfinkel (Hebrew: יוסף גרפינקל; born 1956) is an Israeli archaeologist and academic. He is a professor of Prehistoric Archaeology and of Archaeology of the Biblical Period at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Biography

Yosef G ...

.

The earliest traces of human activity include some 460 microlith

A microlith is a small Rock (geology), stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 60,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Austral ...

ic tools dated to the Epipalaeolithic

In archaeology, the Epipalaeolithic or Epipaleolithic (sometimes Epi-paleolithic etc.) is a period occurring between the Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic during the Stone Age. Mesolithic also falls between these two periods, and the two are someti ...

period ( 23,000 to 10,000 BCE). These come along wide evidence for hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

exploitation in the southern coastal plain in that time. This activity come to hiatus during the early periods of sedentation in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, and resumed only during the pre-pottery C phase of the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

( 7000–6400 BCE). Jean Perrot's excavation revealed eight dwelling pits, along with silo

A silo () is a structure for storing Bulk material handling, bulk materials.

Silos are commonly used for bulk storage of grain, coal, cement, carbon black, woodchips, food products and sawdust. Three types of silos are in widespread use toda ...

s and installations, while Garfinkel's excavations revealed numerous pits, hearth

A hearth () is the place in a home where a fire is or was traditionally kept for home heating and for cooking, usually constituted by a horizontal hearthstone and often enclosed to varying degrees by any combination of reredos (a low, partial ...

s and animal bones.

Early Bronze Age

During the Early Bronze Age I period (EB I, 3700–2900 BCE), human settlement thrived in Ashkelon. The central site was in Afridar, situated between two long and wide kurkar

Kurkar ( /) is the term used in Arabic and modern Hebrew for the rock type of which lithification, lithified sea sand dunes consist. The equivalent term used in Lebanon is ramleh.

History

Kurkar is the regional name for an aeolian quartz sands ...

ridges. This area had unique ecological conditions, offering an abundance of goundwater, fertile soils and varied flora and fauna. Two other settlements existed at Tel Ashkelon itself, and in the Barnea neighborhood of modern Ashkelon. The site of Afridar is one of the most extensive and most excavated settlements of the EB I period, with over two dozen dig sites, excavated by the Israel Antiquities Authority

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA, ; , before 1990, the Israel Department of Antiquities) is an independent Israeli governmental authority responsible for enforcing the 1978 Law of Antiquities. The IAA regulates excavation and conservatio ...

(IAA). The flourishment of EB I Ashkelon has also been linked to trade relations with Prehistoric Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt was the period of time starting at the first human settlement and ending at the First Dynasty of Egypt around 3100 BC.

At the end of prehistory, "Predynastic Egypt" is traditionally defined as the period ...

. The site of Afridar was abandoned at the start of the EB II period ( 2900 BCE). It was suggested that the cause for the abandonment was a climate change causing increased precipitation, which destroyed the ecological condition that had served the locals for centuries.

In the EB II–III (2900–2500 BCE), the site of Tel Ashkelon served as an important seaport for the trade route between the Old Kingdom of Egypt

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning –2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynasty ...

and Byblos

Byblos ( ; ), also known as Jebeil, Jbeil or Jubayl (, Lebanese Arabic, locally ), is an ancient city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. The area is believed to have been first settled between 8800 and 7000BC and continuously inhabited ...

. Excavations at the northern side of the mound revealed a mudbrick structure and numerous olive-oil jars.

Canaanite Ashkelon (1800–1170 BCE)

Middle Bronze Age

Ashkelon was resettled in the Middle Bronze Age on the background of country-wide urban renaissance, linked to the immigration of Amorites

The Amorites () were an ancient Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic-speaking Bronze Age people from the Levant. Initially appearing in Sumerian records c. 2500 BC, they expanded and ruled most of the Levant, Mesopotamia and parts of Eg ...

people from the north, as well as the revival of trade relations between Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (also known as The Period of Reunification) is the period in the history of ancient Egypt following a period of political division known as the First Intermediate Period of Egypt, First Intermediate Period. The Middl ...

and Byblos

Byblos ( ; ), also known as Jebeil, Jbeil or Jubayl (, Lebanese Arabic, locally ), is an ancient city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. The area is believed to have been first settled between 8800 and 7000BC and continuously inhabited ...

. It soon become the fortified center of a city-kingdom, as evidenced by both historical records and archaeology. Ashkelon first mention in historical records is in the Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

Execration Texts

Execration texts, also referred to as proscription lists, are ancient Egyptian hieratic texts, listing enemies of the pharaoh, most often enemies of the Egyptian state or troublesome foreign neighbors. The texts were most often written upon stat ...

from the time of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is a series of rulers reigning from 1991–1802 BC (190 years), at what is often considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI–XIV). The dynasty period ...

(20th–19th centuries BCE). These texts were written on red pots, which were broken as part of a cursing ritual against Egypt's enemies. Ashkelon appears three times under the name Asqanu (''ꜥIsqꜥnw),'' along with three of its rulers ''ḫꜥykm'' (or Khalu-Kim), ''ḫkṯnw'' and ''Isinw''.Northwest Semitic

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic language, Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite l ...

origin, are identified as Amorites

The Amorites () were an ancient Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic-speaking Bronze Age people from the Levant. Initially appearing in Sumerian records c. 2500 BC, they expanded and ruled most of the Levant, Mesopotamia and parts of Eg ...

. Scholars have suggested Ashkelon was one of many Levantine city-states established by Amorites in the early second millennium BCE.

The most distinctive feature of the site of Ashkelon is its fortifications, consisting of free-standing earthen ramparts which were erected as early as around 1800 BCE. In the excavations of the northern slope of the ramparts, archaeologists detected five phases of construction including city gates, moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch dug around a castle, fortification, building, or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. Moats can be dry or filled with water. In some places, moats evolved into more extensive water d ...

s, guard towers and in a later phase, a sanctuary right after the entrance to the city. The material culture and especially Egyptian-style pottery showed that Middle Bronze Ashkelon lasted until around 1560 BCE.

Late Bronze Age (Egyptian rule)

Early decades of Egyptian rule (15th century BCE)

Ashkelon came under the control of the New Kingdom of Egypt

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of History of ancient Egypt, ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth, ...

in the time of Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, (1479–1425 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He is regarded as one of the greatest warriors, military commanders, and milita ...

, following the Battle of Megiddo (1457 BCE). During the Late Bronze Age, its territory stretched across the coastal plain

A coastal plain (also coastal plains, coastal lowland, coastal lowlands) is an area of flat, low-lying land adjacent to a sea coast. A fall line commonly marks the border between a coastal plain and an upland area.

Formation

Coastal plains can f ...

, bordering Gaza to the south, Lachish

Lachish (; ; ) was an ancient Canaanite and later Israelite city in the Shephelah ("lowlands of Judea") region of Canaan on the south bank of the Lakhish River mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The current '' tell'' by that name, kn ...

and Gezer

Gezer, or Tel Gezer (), in – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. It is now an List of national parks ...

to the east and Gezer

Gezer, or Tel Gezer (), in – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. It is now an List of national parks ...

to the north.Amenhotep II

Amenhotep II (sometimes called Amenophis II and meaning "Amun is Satisfied") was the seventh pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. He inherited a vast kingdom from his father Thutmose III, and held it by means of a few military campaigns i ...

(1427–1401 BCE). It includes list compiled by an Egyptian official detailing rations of bread and beer, that were provided to envoys of noble chariot warriors (Maryannu

The Maryannu were a caste of chariot-mounted hereditary warrior nobility that existed in many of the societies of the Ancient Near East during the Bronze Age. ''Maryannu'' is a Hurrianized Indo-Aryan word, formed by adding the Hurrian suffix ''- ...

) from 12 Canaanite cities, including Ashkelon. It is believed that these envoys were securing the caravans that carried tribute to the Egyptian king, and that they served as his loyal ambassadors.

Amarna period (14th century BCE)

During the Amarna Period (mid-14th century BCE, mostly during the reign of Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton ( ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning 'Effective for the Aten'), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eig ...

), Ashkelon maintained its ties to Egypt. Over a dozen letters inscribed in clay that were found in the Amarna letters are linked to Ashkelon. A petrographic

Petrography is a branch of petrology that focuses on detailed descriptions of rocks. Someone who studies petrography is called a petrographer. The mineral content and the textural relationships within the rock are described in detail. The classi ...

analysis of the clay used in five letters sent by a ruler named Shubandu have supported the hypothesis that he ruled Ashkelon.Abdi-Heba

Abdi-Ḫeba (Abdi-Kheba, Abdi-Ḫepat, or Abdi-Ḫebat) was a local chieftain of History of Jerusalem, Jerusalem during the Amarna period (mid-1330s BC). Ancient Egypt, Egyptian documents have him deny he was a mayor (''ḫazānu'') and assert he ...

, the ruler of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, accuses Yidya, as well as the rulers of Lachish

Lachish (; ; ) was an ancient Canaanite and later Israelite city in the Shephelah ("lowlands of Judea") region of Canaan on the south bank of the Lakhish River mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The current '' tell'' by that name, kn ...

and Gezer

Gezer, or Tel Gezer (), in – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. It is now an List of national parks ...

of provisioning the ʿApiru

ʿApiru (, ), also known in the Akkadian version Ḫabiru (sometimes written Habiru, Ḫapiru or Hapiru; Akkadian: 𒄩𒁉𒊒, ''ḫa-bi-ru'' or ''*ʿaperu'') is a term used in 2nd-millennium BCE texts throughout the Fertile Crescent for a so ...

, who were adversaries of the Egyptian empire. In another letter, Yidya is asked to send glass ingots to Egypt.

Final years of Egyptian rule (late 13th century – 1170 BCE)

The Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah, is an inscription by Merneptah, a pharaoh in ancient Egypt who reigned from 1213 to 1203 BCE. Discovered by Flinders Petrie at Thebes, Egypt, Thebes in 1896, i ...

from 1208 BCE, commemorates the victory of Merneptah

Merneptah () or Merenptah (reigned July or August 1213–2 May 1203 BCE) was the fourth pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. According to contemporary historical records, he ruled Egypt for almost ten y ...

against the rebellious Ashkelon, Gezer

Gezer, or Tel Gezer (), in – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. It is now an List of national parks ...

, Yenoam and the Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

".

Philistine Ashkelon (1170–604 BCE)

The founding of Philistine

Philistines (; Septuagint, LXX: ; ) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that the Philist ...

Ashkelon, on top of the Egyptian-ruled Canaanite city, was dated by the site's excavators to 1170 BCE. Their earliest pottery, types of structures and inscriptions are similar to the early Greek urbanised centre at Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; ; or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines, Greece, Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos, Peloponnese, Argos; and sou ...

in mainland Greece

Greece is a country in Southeastern Europe, on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. It is bordered to the north by Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria; to the east by Turkey, and is surrounded to the east by the Aegean Sea, to the south by the Cret ...

, adding evidence to the conclusion that they were one of the "Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

" that upset cultures throughout the Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a loosely delimited region comprising the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean Sea, and well as the adjoining land—often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea. It includes the southern half of Turkey ...

at that time. In this period, the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

. '' Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

.[

The ]Onomasticon of Amenope

The Onomasticon of Amenope is an ancient Egyptian text from the late 20th Dynasty to 22nd Dynasty. It is a compilation belonging to a tradition that began in the Middle Kingdom, and which includes the ''Ramesseum Onomasticon'' dating from the end ...

, dated to the early 11th century BCE, mentioned Ashkelon along with Gaza and Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

as cities of the Philistines.[

In 2012, an Iron Age IIA Philistine cemetery was discovered outside the city. In 2013, 200 of the cemetery's estimated 1,200 graves were excavated. Seven were stone-built tombs. One ostracon and 18 jar handles were found to be inscribed with the ]Cypro-Minoan script

The Cypro-Minoan syllabary (CM), more commonly called the Cypro-Minoan Script, is an undeciphered syllabary used on the island of Cyprus and at its trading partners during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age (c. 1550–1050 BC). The term "Cy ...

. The ostracon was of local material and dated to 12th to 11th century BCE. Five of the jar handles were manufactured in coastal Lebanon, two in Cyprus, and one locally. Fifteen of the handles were found in an Iron I context and the rest in Late Bronze Age context.

Assyrian vassal and (734 – 620 BCE)

By 734 BCE, Ashkelon was captured by the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

, under the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III. Following the Assyrian campaign, Ashkelon, along with other southern Levantine kingdoms, paid tribute to Assyria, and thus became a vassal kingdom.Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, Tyre and Arab tribes in a revolt against Assyrian hegemony. The revolt failed and Mitinti I was killed and replaced by Rukibtu. The identity of Rukibtu is unknown. It has been conjectured that he was the son of Mitinti I. Otherwise it was suggested that he was a usurper, either one who was installed by the Assyrians, or one who usurped the throne on his own behalf, and secured his rule through accepting Assyrian subjugation. Either way, after Rukibu's ascension, Ashkelon resumed paying annual tributes to Assyria.Sidqa

Ṣidqa (Philistine language, Philistine: 𐤑𐤃𐤒𐤀 *''Ṣīdqāʾ''; Akkadian language, Akkadian: ) was a king of Ascalon in the 8th century BC. He, much like Hezekiah, king of the neighboring Kingdom of Judah, rebelled against the Assyria ...

usurped the throne, and joined the rebellion instigated by king Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; ), or Ezekias (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the thirteenth king of Kingdom of Judah, Judah according to the Hebrew Bible.Stephen L Harris, Harris, Stephen L., ''Understanding the Bible''. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "G ...

of Judah, along with other Levantine kings. Together, they deposed king Padi of Ekron

Ekron (Philistine: 𐤏𐤒𐤓𐤍 ''*ʿAqārān'', , ), in the Hellenistic period known as Accaron () was at first a Canaanite, and later more famously a Philistine city, one of the five cities of the Philistine Pentapolis, located in pr ...

who remained loyal to Assyria.Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

's was suppressed during his third campaign In 701 BCE, as described in the Taylor Prism. At that time, Ashkelon controlled several cities in the Yarkon River

The Yarkon River, also Yarqon River or Jarkon River (, ''Nahal HaYarkon''; , ''Nahr al-Auja''), is a river in central Israel. The source of the Yarkon ("Greenish" in Hebrew) is at Tel Afek (Antipatris), north of Petah Tikva. It flows west throu ...

basin (near modern Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( or , ; ), sometimes rendered as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and usually referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a popula ...

, including Beth Dagon, Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

, Beneberak

Benebarak ('Sons of Barak') (, ''Bnei Brak'') was a biblical city mentioned in the Book of Joshua. According to the biblical account it was allocated to the Tribe of Dan. Its archaeological site is Tel Bnei Brak.

History

The town of Beneberak ('' ...

and Azor

Azor () is a local council (Israel), local council in the Tel Aviv District of Israel, on the old Jaffa-Jerusalem road southeast of Tel Aviv. Established in 1948, Azor was granted local council status in 1951. In it had a population of , and ha ...

). These were seized and sacked during the Assyrian campaign. Sidqa himself was exiled with all of his family and was replaced Šarru-lu-dari Šarru-lu-dari (Akkadian language, Akkadian: ), meaning "May the king be everlasting") was a king of Ascalon during the reign of the Neo-Assyrian emperors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal. His father was named ''Rukibtu'', who ruled Ascalon ...

, the son of Rukibtu, who resumed paying tribute to Assyria. During most of the 7th century BCE, Ashkelon was ruled by Mitinti II, the son of Sidqa, who was a vassal to Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (, also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 681 to 669 BC. The third king of the S ...

and Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (, meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir")—or Osnappar ()—was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the th ...

.

Under Egypt and the Babylonian destruction ( 620–604 BCE)

Close connections between Ashkelon and Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

developed in the days of pharaoh Psamtik I

Wahibre Psamtik I (Ancient Egyptian: ) was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the Saite period, ruling from the city of Sais in the Nile delta between 664 and 610 BC. He was installed by Ashurbanipal of the Neo-Assyrian E ...

, after Egypt filled the power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has replac ...

due to the withdrawal of the Assyrian empire

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, an indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

** Post-im ...

from the West. This is demonstrated by the discovery of multiple Egyptian trade items, such as barrel-jars and tripod

A tripod is a portable three-legged frame or stand, used as a platform for supporting the weight and maintaining the stability of some other object. The three-legged (triangular stance) design provides good stability against gravitational loads ...

s made of Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

clay, a jewelry box made of abalone

Abalone ( or ; via Spanish , from Rumsen language, Rumsen ''aulón'') is a common name for any small to very large marine life, marine gastropod mollusc in the family (biology), family Haliotidae, which once contained six genera but now cont ...

shell together with a necklace of amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a perso ...

s. Egyptian cultic and votive

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally ...

items, statuettes

A figurine (a diminutive form of the word ''figure'') or statuette is a small, three-dimensional sculpture that represents a human, deity or animal, or, in practice, a pair or small group of them. Figurines have been made in many media, with cla ...

and offering tables were likewise discovered, demonstrating a religious influence as well. According to Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

(c.484–c.425 BCE), the city's temple of Aphrodite

Aphrodite (, ) is an Greek mythology, ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, procreation, and as her syncretism, syncretised Roman counterpart , desire, Sexual intercourse, sex, fertility, prosperity, and ...

(Derketo

Atargatis (known as Derceto by the Greeks) was the chief goddess of northern Syria in Classical antiquity. Primarily she was a fertility goddess, but, as the ''baalat'' ("mistress") of her city and people she was also responsible for their prot ...

) was the oldest of its kind, imitated even in Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, and he mentions that this temple was pillaged by marauding Scythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

during the time of their sway over the Medes

The Medes were an Iron Age Iranian peoples, Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media (region), Media between western Iran, western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, they occupied the m ...

(653–625 BCE).

By the end of the 7th century BCE, Ashkelon's population is estimated to have been 10,000–12,000. It had fortifications which integrated and developed the Canaanite ramparts, in addition to an estimated 50 protective towers. Industry included wine and olive oil production and export, and possibly textile weaving. Together with Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

, it is the site most abundant with Red-Slipped ware, both imported and locally made, which decreases greatly further inland.[Stager 1996, p. 67*] Imports further included amphora

An amphora (; ; English ) is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storage rooms and packages, tied together with rope and delivered by land ...

e, elegant bowls and cups, "Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

ware", and red and cream polished tableware

Tableware items are the dishware and utensils used for setting a table, serving food, and dining. The term includes cutlery, glassware, serving dishes, serving utensils, and other items used for practical as well as decorative purposes. The ...

from Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

, together with amphorae and decorated fine-ware from Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

, Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and the Greek islands

Greece has many islands, with estimates ranging from somewhere around 1,200 to 6,000, depending on the minimum size to take into account. The number of inhabited islands is variously cited as between 166 and 227.

The largest Greek island by ...

.Babylonian king

The king of Babylon (Akkadian language, Akkadian: , later also ) was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon and its kingdom, Babylonia, which existed as an independent realm from the 19th century BC to its fall in the 6th century BC. ...

Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II, also Nebuchadrezzar II, meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir", was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Often titled Nebuchadnezzar ...

. By the month of Kislev

Kislev or Chislev (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew, Standard ''Kīslev'' Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Kīslēw''), is the third month of the civil year and the ninth month of the ecclesiastical year on the Hebrew c ...

(November or December) 604 BCE, the city was burnt, destroyed and its king Aga' taken into exile.[ The destruction of Ashkelon is reported in the ]Babylonian Chronicles

The Babylonian Chronicles are a loosely-defined series of about 45 clay tablet, tablets recording major events in Babylonian history.

They represent one of the first steps in the development of ancient historiography. The Babylonian Chronicles a ...

and from a poem found in Oxyrhynchus

Oxyrhynchus ( ; , ; ; ), also known by its modern name Al-Bahnasa (), is a city in Middle Egypt located about 160 km south-southwest of Cairo in Minya Governorate. It is also an important archaeological site. Since the late 19th century, t ...

, Egypt, written by Greek poet Alcaeus whose brother, Antimenidas, served in the Babylonian army as a mercenary. As for the reason for Its destruction, it is noted by scholars that it came one year after the Assyrian-Egyptian defeat in the battle of Carchemish

The Battle of Carchemish was a battle fought around 605 BCE between the armies of Egypt, allied with the remnants of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, against the armies of Babylonia. The forces would clash at Carchemish, an important military crossing a ...

. Concern over the strong Egyptian influence on Ashkelon, and possibly its direct rule may be what brought Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II, also Nebuchadrezzar II, meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir", was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Often titled Nebuchadnezzar ...

to reduce Ashkelon to rubble, ahead of the failed Babylonian invasion of Egypt. With the Babylonian destruction, the Philistine era was over. After its destruction, Ashkelon remained desolate for seventy years, until the Persian period

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

.

Tyrian settlement under Persian rule ( 520–332 BCE)

Following the Babylonian destruction, Ashkelon was deserted for about 80 years. While there are few historical sources about Ashkelon after the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

took over, archaeological investigations reveal that it was rebuilt around 520–510 BCE (based on ceramic evidence). The Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

has probably visited Ashkelon as part of his voyage in the 440s BCE and described the city's residents as Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns. It was one of the first coastal sites to be established the by Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns, and in Ashkelon's case, by Tyre,Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax

The ''Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax'' is an ancient Greek periplus (περίπλους ''períplous'', 'circumnavigation') describing the sea route around the Mediterranean and Black Sea. It probably dates from the mid-4th century BC, specifically t ...

from the mid-4th century BCE. Many inscriptions in the Phoenician language were found across the site, including ostraca

An ostracon (Greek language, Greek: ''ostrakon'', plural ''ostraka'') is a piece of pottery, usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In an archaeology, archaeological or epigraphy, epigraphical context, ''ostraca'' refer ...

bearing Phoenician names from the late 6th to late 4th centuries BCE, and one East Greek vase with the Phoenician word for "cake" inscribed on it. The cult of the goddess Tanit

Tanit or Tinnit (Punic language, Punic: 𐤕𐤍𐤕 ''Tīnnīt'' (JStor)) was a chief deity of Ancient Carthage; she derives from a local Berber deity and the consort of Baal Hammon. As Ammon is a local Libyan deity, so is Tannit, who represents ...

was present at Ashkelon by that period. The city minted its own coins, with the abbreviation Aleph

Aleph (or alef or alif, transliterated ʾ) is the first Letter (alphabet), letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician alphabet, Phoenician ''ʾālep'' 𐤀, Hebrew alphabet, Hebrew ''ʾālef'' , Aramaic alphabet, Aramaic ''ʾālap'' � ...

-Nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service and contemplation, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 5 ...

referring to its name.mudbrick

Mudbrick or mud-brick, also known as unfired brick, is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of mud (containing loam, clay, sand and water) mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE.

From ...

superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

s. It had a city plan of streets with workshops and large warehouses by the shore. In these warehouses, many imported vessels and raw materials from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

and Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

were discovered. The origin of these imports is primarily Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

and the Greek regions of Attica

Attica (, ''Attikḗ'' (Ancient Greek) or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the entire Athens metropolitan area, which consists of the city of Athens, the capital city, capital of Greece and the core cit ...

, Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

and Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

, as well as Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

. Among those findings are luxury items such as aryballoi, black-figure

Black-figure pottery painting (also known as black-figure style or black-figure ceramic; ) is one of the styles of Ancient Greek vase painting, painting on pottery of ancient Greece, antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th a ...

and red-figure pottery

Red-figure pottery () is a style of Pottery of ancient Greece, ancient Greek pottery in which the background of the pottery is painted black while the figures and details are left in the natural red or orange color of the clay.

It developed in A ...

, Ionian cups, athenian owl cups and a figurine of the ancient Egyptian

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

god Osiris

Osiris (, from Egyptian ''wikt:wsjr, wsjr'') was the ancient Egyptian deities, god of fertility, agriculture, the Ancient Egyptian religion#Afterlife, afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was ...

, made of bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

. These were dated to the entire span of the period and attest to Ashkelon's role as a major sea port.Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n society and religion in that time.

Hellenistic period (332–37 BCE)

Conquest of Alexander and the Wars of the Diadochi (332–301 BCE)

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

in has captured the Levant in 332 BCE and reigned until 323 BCE. No known historical source describe what happened to Ascalon during that time. It was speculated that, following Alexander's seven month long siege and subsequent destruction Tyre, Ascalon's residents surrendered peacefully to his forces. This is further suggested by the Ascalon's absence from accounts of the two-month-long Siege of Gaza, its southern neighbor. The city's history in the final years of the 4th century BCE remains obscure. During this time, the region changed hands multiple times amid the conflict between Ptolemaic Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

*Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

*Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining t ...

and Antigonid kingdoms, as part of the Wars of the Diadochi

The Wars of the Diadochi (, Romanization of Greek, romanized: ', ''War of the Crown Princes'') or Wars of Alexander's Successors were a series of conflicts fought between the generals of Alexander the Great, known as the Diadochi, over who would ...

. These wars concluded with a Ptolemaic victory in the Levant in 301 BCE.

Ptolemaic rule (301–198 BCE)

Archaeological excavations have uncovered evidence evidence of violent destruction across the site, dated around 290 BCE. This period corresponds to the reign of Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

during which the Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

was consolidating its control over the Levant. Remains of collapsed and burnt structures were found, along with two hoards of silver coins discovered within the destruction layers, one of which appears to have been hastily buried by a resident shortly before the destruction.Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

and Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

, as one of the four prominent ports in the Southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a geographical region that corresponds approximately to present-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southern Syria and the Sinai Peninsula. As a strictly geographical descript ...

in the ''Letter of Aristeas'', dated to the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (, ''Ptolemaîos Philádelphos'', "Ptolemy, sibling-lover"; 309 – 28 January 246 BC) was the pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 284 to 246 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy I, the Macedonian Greek general of Alexander the G ...

(). Ascalon appears once in the ''Zenon Papyri'', the correspondence of Zenon of Kaunos, private secretary to Apollonius

Apollonius () is a masculine given name which may refer to:

People Ancient world Artists

* Apollonius of Athens (sculptor) (fl. 1st century BC)

* Apollonius of Tralles (fl. 2nd century BC), sculptor

* Apollonius (satyr sculptor)

* Apo ...

, the Ptolemaic finance minister, around 259 BCE. his limited mention suggests that Ascalon held a secondary status compared to other coastal cities, particularly Gaza, which is referenced numerous times. According to Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

( ''Antiquities of the Jews''), Ascalon's residents refused to pay taxes to Joseph ben Tobia a Jewish tax-farmer

Farming or tax-farming is a technique of financial management in which the management of a variable revenue stream is assigned by legal contract to a third party and the holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from the contra ...

appointed by Ptolemy III Euergetes

Ptolemy III Euergetes (, "Ptolemy the Euergetes, Benefactor"; c. 280 – November/December 222 BC) was the third pharaoh of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt from 246 to 222 BC. The Ptolemaic Kingdom reached the height of its military and economic ...

around 242 BCE, and even insulted him. In response, Joseph had twenty of the cirty's nobles, and seized their property as tribute to the king, likely intended as a warning to other cities.

During the Fourth Syrian War (219–217 BC), the Ptolemaic kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

fought the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great ...

under Antiochus III the Great

Antiochus III the Great (; , ; 3 July 187 BC) was the sixth ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 223 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the rest of West Asia towards the end of the 3rd century BC. Rising to th ...

, who sought to reclaim former lands. Ascalon was likely captured by the Seleucids during this conflict, along with Gaza, prior to the Battle of Raphia (217 BCE). That battle ended in a Ptolemaic victory and the restoration of lost territories, including Ascalon. In 202 BCE, Antiochus III launched another campaign into the region, capturing Gaza after a prolonged siege. Ascalon was probably taken without resistance. However it was briefly retaken in the winter of 201/200 BCE by the Ptolemaic general Scopas of Aetolia. His forces were later defeated by the Seleucids at the Battle of Panium

The Battle of Panium (also known as Paneion, , or Paneas, Πανειάς) was fought in 200 BC near Paneas (Caesarea Philippi) between Seleucid and Ptolemaic forces as part of the Fifth Syrian War. The Seleucids were led by Antiochus III t ...

(200 BCE) and the Seleucid control over the country was consolidated by 198 BCE.

Seleucid rule (198–103 BCE)

Following the transition of to Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, a ...

rule, the balance of power between Ascalon and Gaza shifted. Gaza lost its status as the principal port for trade caravans arriving from the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

and, by the 2nd century BCE, ceased minting its own coins. By 169/168 BCE, during the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ( 215 BC–November/December 164 BC) was king of the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC. Notable events during Antiochus' reign include his near-conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt, his persecution of the Jews of ...

(), Ascalon was one of 19 cities across the empire granted minting rights. Historians have proposed several reasons for this policy, including efforts to enlist key cities in the empire's postwar reconstruction or purely financial motives. The coins minted in Ascalon constitute a key body of evidence for reconstructing the city's political history during the late Hellenistic period.

An autonomous coin minted in 168/167 BCE provides the only direct evidence that Ascalon held ''polis'' status by that time. The coin features a portrait of the Greek goddess Tyche

Tyche (; Ancient Greek: Τύχη ''Túkhē'', 'Luck', , ; Roman mythology, Roman equivalent: Fortuna) was the presiding tutelary deity who governed the fortune and prosperity of a city, its destiny. In Classical Greek mythology, she is the dau ...

on one side, and the bow of a warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is used for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the navy branch of the armed forces of a nation, though they have also been operated by individuals, cooperatives and corporations. As well as b ...

with the inscriptions "of the Ascalonians" and "of the demos

Demos may refer to:

Computing

* DEMOS, a Soviet Unix-like operating system

* DEMOS (ISP), the first internet service provider in the USSR

* Demos Commander, an Orthodox File Manager for Unix-like systems

* Plural for Demo (computer programming ...

" on the other side. The exact timing of when cities received ''polis'' status remains debated among scholars. Some argue that such status was granted as early as the Ptolemaic rule. Gideon Fuks suggested that Seleucus IV Philopator

Seleucus IV Philopator ( Greek: Σέλευκος Φιλοπάτωρ, ''Séleukos philopátо̄r'', meaning "Seleucus the father-loving"; 218 – 3 September 175 BC), ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, reigned from 187 BC to 175 BC over a ...

() conferred ''polis'' rights to various cities as part of a decentralization policy intended to strengthen local control over rural hinterlands. He further argued that cities such as Ascalon paid substantial sums for these rights, providing much-needed revenue to the Seleucid state in the aftermath of prolonged warfare.

Political history during the Seleucid Dynastic wars

The political landscape of the region changed dramatically following the Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

(167–141 BCE), the establishment of the Hasmonean Kingdom

The Hasmonean dynasty (; ''Ḥašmōnāʾīm''; ) was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during the Hellenistic times of the Second Temple period (part of classical antiquity), from BC to 37 BC. Between and BC the dynasty rule ...

in Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, and the outbreak of the Seleucid Dynastic Wars

The Seleucid Dynastic Wars were a series of wars of succession that were fought between competing branches of the Seleucid royal household for control of the Seleucid Empire. Beginning as a by-product of several succession crises that arose fro ...

in 157 BCE. In 153 BCE, under pressure from Hasmonean leader Jonathan Apphus

Jonathan Apphus (Hebrew: ''Yōnāṯān ʾApfūs''; Ancient Greek: Ἰωνάθαν Ἀπφοῦς, ''Iōnáthan Apphoûs'') was one of the sons of Mattathias and the leader of the Hasmonean dynasty of Judea from 161 to 143 BCE.

Name

H J Wolf ...

, Ascalon supported the claim of Alexander Balas

Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas (), was the ruler of the Seleucid Empire from 150 BC to August 145 BC.

Picked from obscurity and supported by the neighboring Roman-allied Kingdom of Pergamon, Alexander landed in Phoenicia in 1 ...

against incumbent Seleucid king, Demetrius I Soter

Demetrius I Soter (, ''Dēmḗtrios ho Sōtḗr,'' "Demetrius the Saviour"; 185 – June 150 BC) reigned as king of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire from November 162 to June 150 BC. Demetrius grew up in Rome as a hostage, but returned to Greek S ...

. After Balas was killed in 145 BCE, Ascalon briefly supported Demetrius II Nicator

Demetrius II (, ''Dēmḗtrios B''; died 125 BC), called Nicator (, ''Nikátōr'', "Victor"), was one of the sons of Demetrius I Soter. His mother may have been Laodice V, as was the case with his brother Antiochus VII Sidetes. Demetrius ruled ...

, but Jonathan again compelled the city to recognize Antiochus VI Dionysus, the son of Balas. When Diodotus Tryphon

Diodotus Tryphon (, ''Diódotos Trýphōn''), nicknamed "The Magnificent" () was a Greek king of the Seleucid Empire. Initially an official under King Alexander I Balas, he led a revolt against Alexander's successor Demetrius II Nicator in 144 ...

seized power in 142 BCE, the Ascalon mint began issuing coins bearing his portrait. Antiochus VII Sidetes

Antiochus VII Euergetes (; 164/160 BC129 BC), nicknamed Sidetes () (from Side, a city in Asia Minor), also known as Antiochus the Pious, was ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire from July/August 138 to 129 BC. He was the last Seleucid king ...

later challenged Tryphon, becoming the sole ruler of the Seleucid Empire in 138 BCE. Often regarded as the last strong Seleucid monarch, Sidetes retained control over the Levantine coast, including Ascalon, while the Hasmoneans held Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

to the north.

Following Sidetes died in 128 BCE, the Seleucid Empire fell into renewed civil war. Around 126–123 BCE, Ascalon came under the control of Alexander II Zabinas

Alexander II Theos Epiphanes Nikephoros ( ''Aléxandros Theòs Epiphanḕs Nikēphóros'', surnamed Zabinas; 150 BC – 123 BC) was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, Seleucid monarch who reigned as the List of Syrian monarchs, ...

, a usurper backed by Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

to the south. His brief reign ended when the Ptolemaics shifted their support to his rival, Antiochus VIII Grypus, who defeated Zabinas in 123/122 BCE and took power. Grypus's mother Cleopatra Thea

Cleopatra I or Cleopatra Thea (, which means "Cleopatra the Goddess"; c. 164 – 121 BC), surnamed Eueteria ( ) was a ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire. She was queen consort of Syria from 150 to about 125 BC as the wife of three Kings o ...

, acted as both queen consort

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king, and usually shares her spouse's social Imperial, royal and noble ranks, rank and status. She holds the feminine equivalent of the king's monarchical titles and may be crowned and anointed, but hi ...

and as the ''de facto'' ruler. Coins minted in Ascalon from this period depict both her and Gryphus until her death in 121 BCE, when she was attempting to assassinate of her son. From 120 and 114 BCE, Ascalon's coinage featured only Gryphus portrait.

In 114/113 BCE, Gryphus' half-brother, Antiochus IX Cyzicenus, launched a campaign to seize the throne. He captured most of the Selecuid territory, including Ascalon, which minted coins in his name for two years,until 112/111 BCE. Historians suggest that both the

In 114/113 BCE, Gryphus' half-brother, Antiochus IX Cyzicenus, launched a campaign to seize the throne. He captured most of the Selecuid territory, including Ascalon, which minted coins in his name for two years,until 112/111 BCE. Historians suggest that both the Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

and Hasmonean dynasty

The Hasmonean dynasty (; ''Ḥašmōnāʾīm''; ) was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during the Hellenistic times of the Second Temple period (part of classical antiquity), from BC to 37 BC. Between and BC the dynasty rule ...

may have aided Gryphus in the retaking of Ascalon. Around this time, the city was granted the status of a "holy" and "inviolable" city, likely exempting it from certain taxes and granting it partial of full autonomy, including immunity from legal enforcement actions, except in cases of offenses against the Seleucid king.

Independent Ascalon (103–63 BCE)

By 103 BCE Ascalon began using its own calendar, formally marking its independence. The city remained neutral during the 103–102 BCE conflict involving Hasmonean Alexander Jannaeus

Alexander Jannaeus ( , English: "Alexander Jannaios", usually Latinised to "Alexander Jannaeus"; ''Yannaʾy''; born Jonathan ) was the second king of the Hasmonean dynasty, who ruled over an expanding kingdom of Judaea from 103 to 76 BCE. ...

(), the exiled Ptolemy IX Soter (Lathyrus) who invaded from Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, and the reigning Ptolemaic queen of Egypt, Cleopatra III. Ascalon is thought to have maintained amicable relations with both the Hasmoneans and Ptolemaic Egypt, a diplomatic stance that likely contributed to its continued autonomy. This is supported by the fact that, while Jannaeus conquered the southern coastal region and destroyed Gaza in 95/94 BCE, Ascalon remained untouched, making it the only independent Hellenistic coastal city south of Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

. It continued to maintain friendly relations with both powers for the next four decades until the conquest of Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

.

The Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

recounts a story about a significant case of an early witch-hunt

A witch hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or Incantation, incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the ...

, during the reign of the Hasmonean queen Salome Alexandra

Salome Alexandra, also ''Shlomtzion'', ''Shelamzion'' (; , ''Šəlōmṣīyyōn'', "peace of Zion"; 141–67 BC), was a regnant queen of Judaea, one of only three women in Jewish historical tradition to rule over the country, the other tw ...

. the court of Simeon ben Shetach

Simeon ben Shetach, or Shimon ben Shetach or Shatach (), ''circa'' 140-60 BCE, was a Pharisee scholar and Nasi of the Sanhedrin during the reigns of Alexander Jannæus (c. 103-76 BCE) and his successor, Queen Salome Alexandra (c. 76-67 BCE), wh ...

sentenced to death eighty women in Ascalon who had been charged with sorcery

Sorcery commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed to manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces

** Goetia, ''Goetia'', magic involving the evocation of spirits

** Witchcraft, the ...

.

Roman period (63 BCE – 4th century CE)

By 63 BCE, Roman general

By 63 BCE, Roman general Pompey