Mykola Kostomarov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mykola Ivanovych Kostomarov or Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Костома́ров, ; uk, Микола Іванович Костомаров, ; May 16, 1817, vil. Yurasovka,

In 1862, he was forced to resign from his post as chair of department of history of the

In 1862, he was forced to resign from his post as chair of department of history of the

Kostomarov was also a romantic author and

Kostomarov was also a romantic author and

online

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''On the role of

online

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Two Russian Nationalities'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Some thoughts on the Problem of Federalism in Old Rus' '' (); *Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Great Russian folksongs. Based on the new published materials'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, '' Ivan Susanin. Historical review'' (), in Russian, availabl

online

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''

online

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Southern Russia at the End of the 16th Century'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Northern Russians and their rools during the time of veche. History of Novgorod, Pskov and Vyatka'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''On the Russian history as reflected in geography and ethnography'' (), in Russian, availabl

Voronezh Governorate

Voronezh Governorate (russian: Воронежская губерния, ''Voronezhskaya guberniya''; uk, Воронізька губернія) was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Tsardom of Russia, the Russian Empire, and th ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

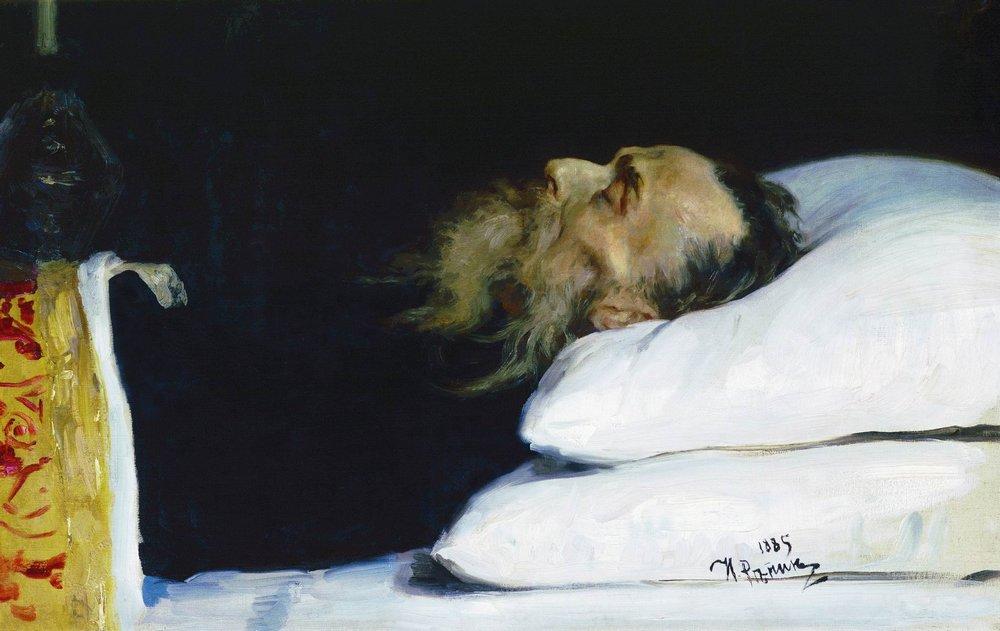

– April 19, 1885, Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

) was one of the most distinguished Russian and Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

historians, a Professor of Russian History at the St. Vladimir University of Kiev and later at the St. Petersburg University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBU; russian: Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter t ...

, an Active State Councillor of Russia, an author of many books, including his famous biography of the seventeenth century Hetman of Zaporozhian Cossacks Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynovii Mykhailovych Khmelnytskyi ( Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern ua, Богдан Зиновій Михайлович Хмельницький; 6 August 1657) was a Ukrainian military commander and ...

, the research on the Ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; Russian: атаман, uk, отаман) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military command ...

of Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (russian: Донские казаки, Donskie kazaki) or Donians (russian: донцы, dontsy) are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (russian: До ...

Stepan Razin and his fundamental 3-volume ''Russian History in Biographies of its main figures'' (russian: Русская история в жизнеописаниях её главнейших деятелей).

Kostomarov was also known as a main figure of the Ukrainian national revival society best known as the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

The Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius ( uk, Кирило-Мефодіївське братство, russian: Кирилло-Мефодиевское братство) was a short-lived secret political society that existed in Kiev (now Kyi ...

, which existed in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

from January 1846 to March 1847. Kostomarov was also a poet, ethnographer, pan-slavist

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rul ...

and promoter of the so-called Narodnik

The Narodniks (russian: народники, ) were a politically conscious movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, ...

s movement in the Russian Empire.

Historian

His father was a Russian landlord, Ivan Petrovich Kostomarov, and he belonged toRussian nobility

The Russian nobility (russian: дворянство ''dvoryanstvo'') originated in the 14th century. In 1914 it consisted of approximately 1,900,000 members (about 1.1% of the population) in the Russian Empire.

Up until the February Revolutio ...

. His distant family roots were in the Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

from the reign of Boris Godunov

Borís Fyodorovich Godunóv (; russian: Борис Фёдорович Годунов; 1552 ) ruled the Tsardom of Russia as ''de facto'' regent from c. 1585 to 1598 and then as the first non-Rurikid tsar from 1598 to 1605. After the end of his ...

. His mother Tatiana Petrovna Melnikova, was an ethnic Ukrainian peasant and one of his father's serfs; that is why Mykola Kostomarov ''de jure'' was a "serf" of his father. His father ended up marrying his mother, but he was born before this. His father wanted to adopt young Mykola, but he didn't get a chance before he was killed at the hands of his domestic serfs, in 1828, when Mykola was 11 years old. His father was known to be cruel to his serfs, and they reportedly stole his fathers money after they killed him.

Kostomarov was a specialist of East Slavic folklore. He put forward the idea that there are two types of ''Rus' people'', those of the Kievan background, among the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

Basin, which he called Southern Russians, and those of the Novgorodian background, which he called Northern Russians. Kostomarov observed Northern Russians as a political hegemon of the Russian state. As a historian, Kostomarov's writings reflected the romantic trends of his time. He was the first Russian historian who used of ethnography and folksong in history, and tried to discern the "spirit" of the people, including the so-called "national spirit", by this method (see about: russian: народность, narodnost'). On the basis of their folksongs and history, he said that the peoples of what he called ''Northern'' or '' Great Rus''' on one hand and ''Southern'' or '' Little Rus''' on the other (Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

and Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

, respectively) differed in character and formed two separate Russian nationalities. In his famous essay ''Two Russian Nationalities'' (russian: Две русские народности), a landmark in the history of Narodnik

The Narodniks (russian: народники, ) were a politically conscious movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, ...

s thought, he wrote what some consider to be the ideas of Russians inclined towards autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except per ...

, collectivism, and state-building, and Ukrainians inclined towards liberty, and individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

. The article of Kostomarov on the problem of the psychological diversity of Rus' people in the Russian Empire had an impact on the scientific research of the collective psychology in Eastern Europe.

In his various historical writings, Kostomarov was always very positive about Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

and Novgorod Republic

The Novgorod Republic was a medieval state that existed from the 12th to 15th centuries, stretching from the Gulf of Finland in the west to the northern Ural Mountains in the east, including the city of Novgorod and the Lake Ladoga regions of mod ...

, about what he considered to be the ''veche

Veche ( rus, вече, véče, ˈvʲet͡ɕe; pl, wiec; uk, ві́че, víče, ; be, ве́ча, viéča, ; cu, вѣще, věšte) was a popular assembly in medieval Slavic countries.

In Novgorod and in Pskov, where the veche acquired gr ...

'' system of popular assemblies (see especially his monography ''On the role of Novgorod the Great in the Russian history'' (russian: О значении Великого Новгорода в русской истории), and the later Zaporozhian Cossack brotherhood, which he thought in part was an heir to the democratic system as well. By contrast, he was critical of the old autocracy in the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Kostomarov gained some popular notoriety in his day by doubting the story of Ivan Susanin, a legendary martyr hero viewed as a saviour of the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I ...

(see: Ivan Susanin. Historical review russian: Иван Сусанин (Историческое исследование)). Kostomarov was interested in the history of the insurgent leaders in Russia. His detailed writing on the case of Stepan Razin, one of the most popular figures in the history of the Don Cossack Host

Don Cossacks (russian: Донские казаки, Donskie kazaki) or Donians (russian: донцы, dontsy) are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (russian: До� ...

, was particularly important for the political evolution of Narodniks.

Kostomarov vs. Pogodin

Kostomarov maintained a long-standing argument withMikhail Pogodin

Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin (russian: Михаи́л Петро́вич Пого́дин; , Moscow, Moscow) was a Russian Imperial historian and journalist who, jointly with Nikolay Ustryalov, dominated the national historiography between the death ...

regarding the linguistic and ethnographic origin of the word "Rus'". Kostomarov refused the fact that the name ''Rus' '' comes into Slavic area from Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

, while Pogodin claimed that the first Rus' people

The Rusʹ (Old East Slavic: Рѹсь; Belarusian, Russian, Rusyn, and Ukrainian: Русь; Old Norse: '' Garðar''; Greek: Ῥῶς, ''Rhos'') were a people in early medieval eastern Europe. The scholarly consensus holds that they were or ...

came from Roslagen

Roslagen is the name of the coastal areas of Uppland province in Sweden, which also constitutes the northern part of the Stockholm archipelago.

Historically, it was the name for all the coastal areas of the Baltic Sea, including the eastern p ...

in the area of present-day Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

. Pogodin connected the etnonym ''Rus' '' with Scandinavia with respect to the Trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks

The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks was a medieval trade route that connected Scandinavia, Kievan Rus' and the Eastern Roman Empire. The route allowed merchants along its length to establish a direct prosperous trade with the Empir ...

. On the contrary linked Kostomarov the etnonym Rus' with East Slavic oucumene. The argument between Kostomarov and Pogodin about the origin of ''Rus' '' had an influence on the building of two different historiographical schools in Russia: the so-called ″ normannists″ and ″anti-normannists″. Influenced by this argument between Pogodin and Kostomarov, which took place at the Moscow Imperial University, Prince Pyotr Vyazemsky

Prince Pyotr Andreyevich Vyazemsky ( rus, Пëтр Андре́евич Вя́земский, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐnˈdrʲejɪvʲɪt͡ɕ ˈvʲæzʲɪmskʲɪj; 23 July 1792 – 22 November 1878) was a Russian Imperial poet, a leading personality of ...

said: ″If we didn't know before which way we were going, now we don't know from where we are going as well″.

Religion

Kostomarov was a very religious man and a devout adherent of theRussian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

. He was critical of Catholic and Polish influences on the area of Ukraine and Belarus throughout the centuries, but, nevertheless, was considered as more open to Catholic culture than many of his Russian contemporaries, and later, the members of the Slavic Benevolent Societies.

Cultural politics

He was considered by many to be a leading intellectual of theNarodniks

The Narodniks (russian: народники, ) were a politically conscious movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, ...

. Mykola Kostomarov was important in the history of both Russian and Ukrainian culture. The question of whether he was more "Russian" or more "Ukrainian" first arose while he was still alive and is still a matter of some dispute. Kostomarov was active in cultural politics in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

being a proponent of a Pan-Slavic and federalized political system. He was a major personality in the Ukrainian national movement, a friend of the poet Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

, a defender of the Ukrainian language in literature and in the schools, and a proponent of a populist form of Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rule ...

, a popular movement in a certain part of the Russian intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

of his time. In the 1840s, he helped to found an illegal political organization called the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

The Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius ( uk, Кирило-Мефодіївське братство, russian: Кирилло-Мефодиевское братство) was a short-lived secret political society that existed in Kiev (now Kyi ...

in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

(for which he suffered arrest, imprisonment, and exile). After that he moved to Saratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901, ...

. From 1847 to 1854 Kostomarov, whose interest in the history of Little Russia and its literature made him suspected of separatist views, wrote nothing, having been banished to Saratov, and forbidden to teach or publish. But after this time his literary activity began again, and, besides separate works, the leading Russian reviews, such as ''Old and New Russia'', ''The Historical Messenger'', and ''The Messenger of Europe'', contained many contributions from his pen of the highest value.

In 1862, he was forced to resign from his post as chair of department of history of the

In 1862, he was forced to resign from his post as chair of department of history of the University of Saint Petersburg

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

, because he had sympathized with the revolutionary movement of liberals, progressives, and socialists.

After his arrests, he continued to promote the ideas of federalism and populism in Ukrainian and Russian historical thought. He had a profound influence on later Ukrainian historians such as Volodymyr Antonovych

Volodymyr Antonovych ( ukr, Володимир Боніфатійович Антонович, tr. ''Volodymyr Bonifatijovych Antonovych''; pl, Włodzimierz Antonowicz; russian: Влади́мир Бонифа́тьевич Антоно́вич, ...

and Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky ( uk, Михайло Сергійович Грушевський, Chełm, – Kislovodsk, 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figure ...

.

Writer

Kostomarov was also a romantic author and

Kostomarov was also a romantic author and poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or w ...

, a member of the Kharkov Romantic School. He published two poetry collections (''Ukrainian Ballads'' (1839) and ''The Branch'' (1840)), both collections containing historical poems mostly about Kievan Rus' and Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynovii Mykhailovych Khmelnytskyi ( Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern ua, Богдан Зиновій Михайлович Хмельницький; 6 August 1657) was a Ukrainian military commander and ...

. He also published a detailed analysis of the Great Russian folksongs. Kostomarov's poetry is known for including vocabulary and other elements of traditional elements and folk songs, which he collected and observed in his historical research with respect to the ethnography.

Kostomarov also wrote historical drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has b ...

s, however these had little influence on the development of the theater. He also wrote a prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the fo ...

in Russian (the novelette '' Kudeyar'', 1875), and a Russian mixed with Ukrainian peace (''Chernigovka'', 1881), but these also are considered insignificant.

Original works

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Russian History in Biographies of its main figures'' (), in Russian, availablonline

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''On the role of

Novgorod the Great

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ol ...

in the Russian history'' (), in Russian, availablonline

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Two Russian Nationalities'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Some thoughts on the Problem of Federalism in Old Rus' '' (); *Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Great Russian folksongs. Based on the new published materials'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, '' Ivan Susanin. Historical review'' (), in Russian, availabl

online

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''

Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (russian: Смутное время, ), or Smuta (russian: Смута), was a period of political crisis during the Tsardom of Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Fyodor I (Fyodor Ivanovich, the last of the Rurik dy ...

in the History of the Tsardom of Moscow'' (), in Russian, availablonline

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Southern Russia at the End of the 16th Century'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''Northern Russians and their rools during the time of veche. History of Novgorod, Pskov and Vyatka'' (), in Russian, availabl

*Nikolai Kostomarov, ''On the Russian history as reflected in geography and ethnography'' (), in Russian, availabl

Academic literature

* Natalia Fokina, ''N. I. Kostomarov. Ideia federalizma v polytycheskom tvorchestve'' (N. I. Kostomarov and the idea of federalism in his political legacy). Moscow University Press, 2007. In Russian. * Boris Litvak, ''Nikolai Kostomarov, historian and his time''. Jerusalem 2000. In Russian. * Raisa Kireeva, ''"He couldn't live without writing". Nikolai Kostomarov.'' Moscow 1996. In Russian. *''Fashioning Modern Ukraine: Selected Writings of Mykola Kostomarov, Volodymyr Antonovych, and Mykhailo Drahomanov'', ed. Serhiy Bilenky (Toronto-Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 2013). Contains a lengthy selection (134 pages) from his various writings including his two autobiographies and his important ideological tract "Two Rus Nationalities." *Dmytro Doroshenko

Dmytro Doroshenko ( uk, Дмитро Іванович Дорошенко, ''Dmytro Ivanovych Doroshenko'', russian: Дми́трий Ива́нович Дороше́нко; 8 April 1882 – 19 March 1951) was a prominent Ukrainian political figu ...

, "A Survey of Ukrainian Historiography," ''Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the US'', V-VI, 4 (1957),132-57.

*Thomas M. Prymak, ''Mykola Kostomarov: A Biography'' (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), .

*Thomas M. Prymak, "Kostomarov and Hrushevsky in Ukrainian History and Culture," ''Ukrainskyi istoryk'', vols. 43-44, nos. 1-2 (2006–07), 307-19. Comparison of Ukraine's two most prestigious historians. This article is in English.

Footnotes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kostomarov, Nikolay 1817 births 1885 deaths People from Voronezh Oblast People from Ostrogozhsky Uyezd Russian untitled nobility Russian Orthodox Christians from Russia Historians of Russia Historians from the Russian Empire Male writers from the Russian Empire Folklorists from the Russian Empire Mythopoeic writers Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius members Hromada (society) members 19th-century historians from the Russian Empire 19th-century male writers National University of Kharkiv alumni Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences