Mount Rushmore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mount Rushmore National Memorial is a national memorial centered on a colossal sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore (

(November 1, 2004). Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 13, 2006. The sculptor and tribal representatives settled on Mount Rushmore, which also has the advantage of facing southeast for maximum sun exposure. Doane Robinson wanted it to feature American West heroes, such as

Keystone Characters

. Retrieved October 3, 2006. The United States Board of Geographic Names officially recognized the name "Mount Rushmore" in June 1930.

The chief carver of the mountain was

The chief carver of the mountain was

"Timeline: Mount Rushmore" (2002). Retrieved March 20, 2006. In 1939, the face of Theodore Roosevelt was dedicated. The Sculptor's Studio – a display of unique plaster models and tools related to the sculpting – was built in 1939 under the direction of Borglum. Borglum died from an

. Tourism in South Dakota. Laura R. Ahmann. Retrieved March 19, 2006. Nick Clifford, the last remaining carver, died in November 2019 at age 98.

Exploring the contribution of National Parks to the entertainment industry's intellectual property

, in Linda J. Bilmes and John B. Loomis, ''Valuing U.S. National Parks and Programs: America's Best Investment'' (Routledge, 2020)

p. 95–98

However, Mount Rushmore also provides access to a surrounding environment of wilderness, which distinguishes it from the typical proximity of national monuments to urban centers like Washington, D.C., and New York City. In the 1950s and 1960s, local Lakota Sioux elder Benjamin Black Elk (son of medicine man

Borglum originally envisioned a grand Hall of Records where America's greatest historical documents and artifacts could be protected and shown to tourists. He managed to start the project, but cut only 70 feet (21 m) into the rock before work stopped in 1939 to focus on the faces. In 1998, an effort to complete Borglum's vision resulted in a repository being constructed inside the mouth of the cave housing 16 enamel panels that contained biographical and historical information about Mount Rushmore as well as the texts of the documents Borglum wanted to preserve there. The vault consists of a teakwood box (housing the 16 panels) inside of a titanium vault placed in the ground with a granite capstone. The text found on the 16 panels can be found

Borglum originally envisioned a grand Hall of Records where America's greatest historical documents and artifacts could be protected and shown to tourists. He managed to start the project, but cut only 70 feet (21 m) into the rock before work stopped in 1939 to focus on the faces. In 1998, an effort to complete Borglum's vision resulted in a repository being constructed inside the mouth of the cave housing 16 enamel panels that contained biographical and historical information about Mount Rushmore as well as the texts of the documents Borglum wanted to preserve there. The vault consists of a teakwood box (housing the 16 panels) inside of a titanium vault placed in the ground with a granite capstone. The text found on the 16 panels can be found

The flora and fauna of Mount Rushmore are similar to those of the rest of the Black Hills region of South Dakota. Birds including the

The flora and fauna of Mount Rushmore are similar to those of the rest of the Black Hills region of South Dakota. Birds including the

National Park Service. Coarse grained pegmatite

Mount Rushmore has been depicted in multiple films, comic books, and television series. Its functions vary from settings for action scenes to the site of hidden locations. Its most famous appearance is as the location of the final chase scene in the 1959 film ''

Mount Rushmore has been depicted in multiple films, comic books, and television series. Its functions vary from settings for action scenes to the site of hidden locations. Its most famous appearance is as the location of the final chase scene in the 1959 film ''

Review: Nebraska. Dir. Alexander Payne. Paramount Vantage, 2013

. ''Middle West Review'' Volume 1, Number 1, (University of Nebraska Press, Fall 2014), p. 154–55.

Les Visages de l'Amérique, les constructeurs d'une démocratie fédérale

'. Mare et Martin (). French study about the Four Presidents, Life, presidency, influence about American political evolution. (Archived link) * * * Larner, Jesse (2002). ''Mount Rushmore: An Icon Reconsidered''. New York: Nation Books. * Taliaferro, John (2002). ''Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore''. New York: PublicAffairs. . Puts the creation of the monument into a historical and cultural context. * ''The National Parks: Index 2001–2003''. Washington, D.C.:

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

: ''Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe'', or Six Grandfathers) in the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

near Keystone, South Dakota

Keystone is a town in the Black Hills region of Pennington County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 240 at the 2020 census. It had its origins in 1883 as a mining town, and has since transformed itself into a resort town, serving ...

, United States. Sculptor Gutzon Borglum

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American sculptor best known for his work on Mount Rushmore. He is also associated with various other public works of art across the U.S., including Stone Mountain in Georg ...

created the sculpture's design and oversaw the project's execution from 1927 to 1941 with the help of his son, Lincoln Borglum

James Lincoln de la Mothe Borglum (April 9, 1912 – January 27, 1986) was an American sculptor, photographer, author and engineer; he was best known for overseeing the completion of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial after the death of the ...

. The sculpture features the heads of four United States Presidents

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. The officeholder leads the executive branch of the federal government and ...

recommended by Borglum: George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

(1732–1799), Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

(1743–1826), Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

(1858–1919) and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

(1809–1865). The four presidents were chosen to represent the nation's birth, growth, development and preservation, respectively. The memorial park covers and the mountain itself has an elevation of above sea level.Mount Rushmore, South Dakota(November 1, 2004). Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 13, 2006. The sculptor and tribal representatives settled on Mount Rushmore, which also has the advantage of facing southeast for maximum sun exposure. Doane Robinson wanted it to feature American West heroes, such as

Lewis and Clark

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

, their expedition guide Sacagawea

Sacagawea ( or ; also spelled Sakakawea or Sacajawea; May – December 20, 1812 or April 9, 1884).e., present-day Gibbons Pass A week later, on July 13, Sacagawea advised Clark to cross into the Yellowstone River basin at what is now known a ...

, Oglala

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

Lakota chief Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

, Buffalo Bill Cody

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), known as "Buffalo Bill", was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in Le Claire, Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa), but he lived for several years in ...

, and Oglala Lakota chief Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by w ...

. Borglum believed that the sculpture should have broader appeal and chose the four presidents.

Peter Norbeck

Peter Norbeck (August 27, 1870December 20, 1936) was an American politician from South Dakota. After serving two terms as the ninth Governor of South Dakota, Norbeck was elected to three consecutive terms as a United States Senator. Norbeck was ...

, U.S. senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

from South Dakota, sponsored the project and secured federal funding. Construction began in 1927 and the presidents' faces were completed between 1934 and 1939. After Gutzon Borglum died in March 1941, his son Lincoln took over as leader of the construction project. Each president was originally to be depicted from head to waist, but lack of funding forced construction to end on October 31, 1941.

Sometimes referred to as the "Shrine of Democracy", Mount Rushmore attracts more than two million visitors annually.

History

Mount Rushmore was conceived with the intention of creating a site to lure tourists, representing "not only the wild grandeur of its local geography but also the triumph of western civilization over that geography through its anthropomorphic representation." Though for the latest occupants of the land at the time, the Lakota Sioux, as well as other tribes, the monument in their view "came to epitomize the loss of their sacred lands and the injustices they've suffered under the U.S. government." Under the Treaty of 1868, the U.S. government promised the territory, including the entirety of the Black Hills, to the Sioux "so long as the buffalo may range thereon in such numbers as to justify the chase." After the discovery of gold on the land, American settlers migrated to the area in the 1870s. The federal government then forced the Sioux to relinquish the Black Hills portion of their reservation. The four presidential faces were said to be carved into the granite with the intention of symbolizing "an accomplishment born, planned, and created in the minds and by the hands of Americans for Americans".Naming

Mount Rushmore is known to theLakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota: /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples in North America. The modern Sioux consist of two major divisions based on language divisions: the Dakota and ...

as "The Six Grandfathers" (Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe) or "Cougar Mountain" (Igmútȟaŋka Pahá); but American settlers knew it variously as Cougar Mountain, Sugarloaf Mountain, Slaughterhouse Mountain and Keystone Cliffs. As Six Grandfathers, the mountain was on the route that Lakota leader Black Elk

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk (December 1, 1863 – August 19, 1950), was a ''wičháša wakȟáŋ'' (" medicine man, holy man") and '' heyoka'' of the Oglala Lakota people. He was a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse and ...

took in a spiritual journey that culminated at Black Elk Peak

Black Elk Peak is the highest natural point in the U.S. state of South Dakota and the Midwestern United States. It lies in the Black Elk Wilderness area, in southern Pennington County, in the Black Hills National Forest. The peak lies west-sout ...

. Following a series of military campaigns from 1876 to 1878, the United States asserted control over the area, a claim that is still disputed on the basis of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Beginning with a prospecting expedition in 1885 with David Swanzey (husband of Carrie Ingalls

Caroline Celestia Ingalls Swanzey (; August 3, 1870 – June 2, 1946) was the third child of Charles and Caroline Ingalls, and was born in Montgomery County, Kansas. She was a younger sister of Laura Ingalls Wilder, who is known for her '' Litt ...

), and Bill Challis, wealthy investor Charles E. Rushmore began visiting the area regularly on prospecting and hunting trips. He repeatedly joked with colleagues about naming the mountain after himself.Keystone Area Historical SocietKeystone Characters

. Retrieved October 3, 2006. The United States Board of Geographic Names officially recognized the name "Mount Rushmore" in June 1930.

Concept, design and funding

Historian Doane Robinson conceived the idea for Mount Rushmore in 1923 to promote tourism in South Dakota. In 1924, Robinson persuaded sculptorGutzon Borglum

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American sculptor best known for his work on Mount Rushmore. He is also associated with various other public works of art across the U.S., including Stone Mountain in Georg ...

to travel to the Black Hills region to ensure the carving could be accomplished. The original plan was to make the carvings in granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

pillars known as the Needles. However, Borglum realized that the eroded Needles were too thin to support sculpting. He chose Mount Rushmore, a grander location, partly because it faced southeast and enjoyed maximum exposure to the sun.

Borglum said upon seeing Mount Rushmore, "America will march along that skyline."

Borglum had been involved in sculpting the Stone Mountain Memorial to Confederate leaders in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, but was in disagreement with the officials there.

U.S. Senator Peter Norbeck

Peter Norbeck (August 27, 1870December 20, 1936) was an American politician from South Dakota. After serving two terms as the ninth Governor of South Dakota, Norbeck was elected to three consecutive terms as a United States Senator. Norbeck was ...

and Congressman William Williamson of South Dakota introduced bills in early 1925 for permission to use federal land, which passed easily. South Dakota legislation had less support, only passing narrowly on its third attempt, which Governor Carl Gunderson

Carl Gunderson (June 20, 1864February 26, 1933)''Biographical Directory of the South Dakota Legislature, 1889–1989'' (1989), p. 400 was an American politician who served as the 11th Governor of South Dakota. Gunderson, a Republican from Mit ...

signed into law on March 5, 1925. Private funding came slowly and Borglum invited President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a Republican lawyer from New England who climbed up the ladder of Ma ...

to an August 1927 dedication ceremony, at which he promised federal funding. Congress passed the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Act, signed by Coolidge, which authorized up to $250,000 in matching funds. The 1929 presidential transition to Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

delayed funding until an initial federal match of $54,670.56 was acquired.

Carving started in 1927 and ended in 1941 with no fatalities.

Construction

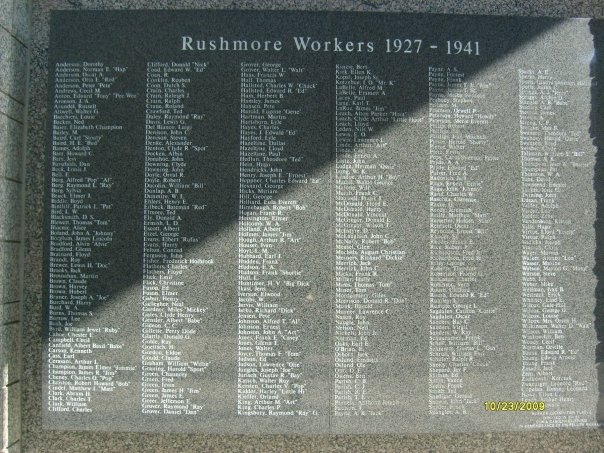

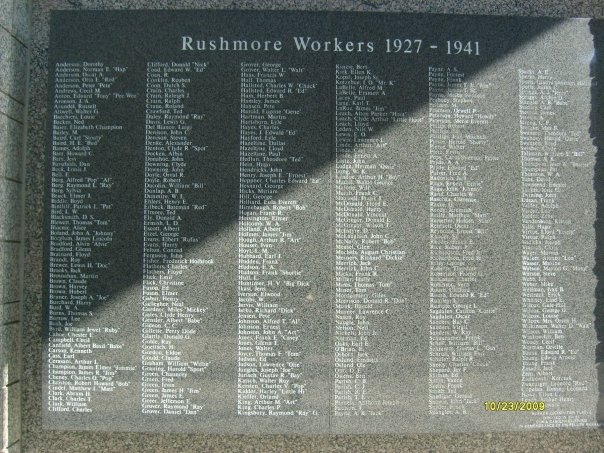

Between October 4, 1927, and October 31, 1941, Gutzon Borglum and 400 workers sculpted the colossal carvings ofUnited States Presidents

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. The officeholder leads the executive branch of the federal government and ...

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

to represent the first 150 years of American history. These presidents were selected by Borglum because of their role in preserving the Republic and expanding its territory. The carving of Mount Rushmore involved the use of dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

, followed by the process of "honeycombing", a process where workers drill holes close together, allowing small pieces to be removed by hand. In total, about of rock were blasted off the mountainside. The image of Thomas Jefferson was originally intended to appear in the area at Washington's right, but after the work there was begun, the rock was found to be unsuitable, so the work on the Jefferson figure was dynamited, and a new figure was sculpted to Washington's left.

The chief carver of the mountain was

The chief carver of the mountain was Luigi Del Bianco

Luigi Del Bianco (May 8, 1892 - January 20, 1969) was an Italian-American sculpture, sculptor, and chief carver of Mount Rushmore.

Early life and education

Bianco was born on a ship near Le Havre, France, on May 8, 1892, to Vincenzo and Osvalda ...

, an artisan and stonemason in Port Chester, New York

Port Chester is a village in the U.S. state of New York and the largest part of the town of Rye in Westchester County by population. At the 2010 U.S. census, the village of Port Chester had a population of 28,967 and was the fifth-most po ...

. Del Bianco emigrated to the U.S. from Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giuli ...

in Italy and was chosen to work on this project because of his understanding of sculptural language and ability to imbue emotion in the carved portraits.

In 1933, the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational properti ...

took Mount Rushmore under its jurisdiction. Julian Spotts helped with the project by improving its infrastructure. For example, he had the tram upgraded so it could reach the top of Mount Rushmore for the ease of workers. By July 4, 1934, Washington's face had been completed and was dedicated. The face of Thomas Jefferson was dedicated in 1936, and the face of Abraham Lincoln was dedicated on September 17, 1937. In 1937, a bill was introduced in Congress to add the head of civil-rights leader Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

, but a rider was passed on an appropriations bill requiring federal funds be used to finish only those heads that had already been started at that time.American Experience"Timeline: Mount Rushmore" (2002). Retrieved March 20, 2006. In 1939, the face of Theodore Roosevelt was dedicated. The Sculptor's Studio – a display of unique plaster models and tools related to the sculpting – was built in 1939 under the direction of Borglum. Borglum died from an

embolism

An embolism is the lodging of an embolus, a blockage-causing piece of material, inside a blood vessel. The embolus may be a blood clot (thrombus), a fat globule (fat embolism), a bubble of air or other gas ( gas embolism), amniotic fluid (am ...

in March 1941. His son, Lincoln Borglum

James Lincoln de la Mothe Borglum (April 9, 1912 – January 27, 1986) was an American sculptor, photographer, author and engineer; he was best known for overseeing the completion of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial after the death of the ...

, continued the project. Originally, it was planned that the figures would be carved from head to waist, but insufficient funding forced the carving to end. Borglum had also planned a massive panel in the shape of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

commemorating in eight-foot-tall gilded letters the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

, U.S. Constitution, Louisiana Purchase, and seven other territorial acquisitions from the Alaska purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

to the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the ter ...

. In total, the entire project cost US$989,992.32 (equivalent to $ in ).Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Tourism in South Dakota. Laura R. Ahmann. Retrieved March 19, 2006. Nick Clifford, the last remaining carver, died in November 2019 at age 98.

Visitor center

Harold Spitznagel and Cecil Doty designed the original visitor center, finished in 1957. These structures were part of theMission 66

Mission 66 was a United States National Park Service ten-year program that was intended to dramatically expand Park Service visitor services by 1966, in time for the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Park Service.

When the National P ...

effort to improve visitors' facilities at national parks and monuments across the country.

Ten years of redevelopment work culminated with the completion of extensive visitor facilities and sidewalks in 1998, such as a Visitor Center, the Lincoln Borglum Museum

The Lincoln Borglum Museum is located in the Mount Rushmore National Memorial near Keystone, South Dakota. It features two 125-seat theaters that show a 13-minute movie about Mount Rushmore. A view thought by many to be one of the best is located a ...

, and the Presidential Trail. Maintenance of the memorial requires mountain climbers to monitor and seal cracks annually. Due to budget constraints, the memorial is not regularly cleaned to remove lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.Alfred Kärcher

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*''Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interlu ...

, a German manufacturer of pressure washing

Pressure washing or power washing is the use of high-pressure water spray to remove loose paint, mold, grime, dust, mud, and dirt from surfaces and objects such as buildings, vehicles and concrete surfaces. The volume of a mechanical pressure w ...

and steam cleaning machines, conducted a free cleanup operation which lasted several weeks, using pressurized water at over .

On October 15, 1966, Mount Rushmore was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

. A 500-word essay giving the history of the United States by Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

student William Andrew Burkett was selected as the college-age group winner in a 1934 competition, and that essay was placed on the Entablature on a bronze plate in 1973. In 1991, President George H. W. Bush officially dedicated Mount Rushmore.

Proposals of adding additional faces

In 1937, when the sculpture was not yet complete, a bill in Congress supporting the addition of women's rights activistSusan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

failed. When the sculpture was completed in 1941, the sculptors said that the remaining rock was not suitable for additional carvings. This stance was shared by RESPEC, an engineering firm charged with monitoring the stability of the rock in 1989. However, proposals of additional sculptures have been made regardless. These include John F. Kennedy after his assassination in 1963, and Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

in 1985 and 1999 – the latter proposal receiving a debate in Congress at the time. Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

was asked about his own potential addition in 2008 and he joked that his ears were too large.

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

has on occasion expressed interest in his own addition to the mountain. During a 2017 rally in Ohio, he said "I'd ask whether or not you some day think I will be on Mount Rushmore. If I did it joking – totally joking, having fun – the fake news media will say, ‘He believes he should be on Mount Rushmore.’ So I won't say it.” By the 2018 account of South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem

Kristi Lynn Noem (; née Arnold; born November 30, 1971) is an American politician serving as the 33rd governor of South Dakota since 2019. A member of the Republican Party, she was the U.S. representative for from 2011 to 2019 and a member ...

, Trump described the potential addition as his "dream" in conversation. In August 2020 it was alleged that the previous year, White House aides working for President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

made contact with Noem the previous year about the process of adding additional presidents, including Trump, to the monument. Trump denied the accusation on his official Twitter account, saying he never "suggested it although, based on all of the many things accomplished during the first years, perhaps more than any other Presidency, sounds like a good idea to me!"

According to a survey of political science experts conducted by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' in 2018, Franklin D. Roosevelt was the most popular choice for addition to Mount Rushmore, regardless of party affiliation. In total, 66% of respondents would choose Roosevelt, followed by Barack Obama at 7% and Ronald Reagan at 5%. Among Democrats, Roosevelt was chosen by 75%, followed by Obama at 11%. Among Republicans, Roosevelt was chosen by 43%, followed by Reagan at 19%. Among Independents, Roosevelt was chosen by 57%, followed by both Reagan and Dwight D. Eisenhower at 11%.

Tourism

Tourism is South Dakota's second-largest industry, and Mount Rushmore is the state's top tourist attraction. 2,185,447 people visited the park in 2012. The popularity of the location, as with many other national monuments, derives from its immediate recognizability; "there are no substitutes for iconic resources such as theStatue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; French: ''La Liberté éclairant le monde'') is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, in the United States. The copper statue, ...

, the Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in ...

, or Mount Rushmore. These locations are one of a kind places".Thomas J. Liu, John B. Loomis, and Linda J. Bilmes,Exploring the contribution of National Parks to the entertainment industry's intellectual property

, in Linda J. Bilmes and John B. Loomis, ''Valuing U.S. National Parks and Programs: America's Best Investment'' (Routledge, 2020)

p. 95–98

However, Mount Rushmore also provides access to a surrounding environment of wilderness, which distinguishes it from the typical proximity of national monuments to urban centers like Washington, D.C., and New York City. In the 1950s and 1960s, local Lakota Sioux elder Benjamin Black Elk (son of medicine man

Black Elk

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk (December 1, 1863 – August 19, 1950), was a ''wičháša wakȟáŋ'' (" medicine man, holy man") and '' heyoka'' of the Oglala Lakota people. He was a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse and ...

, who had been present at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, No ...

) was known as the "Fifth Face of Mount Rushmore", posing for photographs with thousands of tourists daily in his native attire. The South Dakota State Historical Society

The South Dakota State Historical Society is South Dakota's official state historical society and operates statewide but is headquartered in Pierre, South Dakota at 900 Governors Drive. It is a part of the South Dakota Department of Education.

...

notes that he was one of the most photographed people in the world over that 20-year period.

Hall of Records

Borglum originally envisioned a grand Hall of Records where America's greatest historical documents and artifacts could be protected and shown to tourists. He managed to start the project, but cut only 70 feet (21 m) into the rock before work stopped in 1939 to focus on the faces. In 1998, an effort to complete Borglum's vision resulted in a repository being constructed inside the mouth of the cave housing 16 enamel panels that contained biographical and historical information about Mount Rushmore as well as the texts of the documents Borglum wanted to preserve there. The vault consists of a teakwood box (housing the 16 panels) inside of a titanium vault placed in the ground with a granite capstone. The text found on the 16 panels can be found

Borglum originally envisioned a grand Hall of Records where America's greatest historical documents and artifacts could be protected and shown to tourists. He managed to start the project, but cut only 70 feet (21 m) into the rock before work stopped in 1939 to focus on the faces. In 1998, an effort to complete Borglum's vision resulted in a repository being constructed inside the mouth of the cave housing 16 enamel panels that contained biographical and historical information about Mount Rushmore as well as the texts of the documents Borglum wanted to preserve there. The vault consists of a teakwood box (housing the 16 panels) inside of a titanium vault placed in the ground with a granite capstone. The text found on the 16 panels can be found below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

*Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

*Fred Below ( ...

.

Conservation

The ongoing conservation of the site is overseen by the National Park Service. Physical efforts to conserve the monument have included replacement of the sealant applied originally to cracks in the stone by Gutzon Borglum, which had proved ineffective at providing water resistance. The components of Borglum's sealant included linseed oil, granite dust, and white lead, but a modern silicone replacement for the cracks is now used, disguised with granite dust. In 1998, electronic monitoring devices were installed to track movement in the topology of the sculpture to an accuracy of three millimeters. The site was digitally recorded in 2009 using a terrestriallaser scanning

Laser scanning is the controlled deflection of laser beams, visible or invisible.

Scanned laser beams are used in some 3-D printers, in rapid prototyping, in machines for material processing, in laser engraving machines, in ophthalmological la ...

method as part of the international Scottish Ten project, providing a high-resolution record to aid the conservation of the site. This data was made publicly accessible online.

Ecology

The flora and fauna of Mount Rushmore are similar to those of the rest of the Black Hills region of South Dakota. Birds including the

The flora and fauna of Mount Rushmore are similar to those of the rest of the Black Hills region of South Dakota. Birds including the turkey vulture

The turkey vulture (''Cathartes aura'') is the most widespread of the New World vultures. One of three species in the genus '' Cathartes'' of the family Cathartidae, the turkey vulture ranges from southern Canada to the southernmost tip of So ...

, golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird ...

, bald eagle

The bald eagle (''Haliaeetus leucocephalus'') is a bird of prey found in North America. A sea eagle, it has two known subspecies and forms a species pair with the white-tailed eagle (''Haliaeetus albicilla''), which occupies the same niche as ...

, red-tailed hawk

The red-tailed hawk (''Buteo jamaicensis'') is a bird of prey that breeds throughout most of North America, from the interior of Alaska and northern Canada to as far south as Panama and the West Indies. It is one of the most common members wit ...

, swallow

The swallows, martins, and saw-wings, or Hirundinidae, are a family of passerine songbirds found around the world on all continents, including occasionally in Antarctica. Highly adapted to aerial feeding, they have a distinctive appearance. The ...

s and white-throated swift

The white-throated swift (''Aeronautes saxatalis'') is a swift of the family Apodidae native to western North America, south to cordilleran western Honduras.Ryan TP, Collins CT. 2000. White-throated Swift (''Aeronautes saxatalis''). Version 2. ...

s fly around Mount Rushmore, occasionally making nesting spots in the ledges of the mountain. Smaller birds, including songbirds, nuthatch

The nuthatches () constitute a genus, ''Sitta'', of small passerine birds belonging to the family Sittidae. Characterised by large heads, short tails, and powerful bills and feet, nuthatches advertise their territory using loud, simple songs. M ...

es, woodpecker

Woodpeckers are part of the bird family Picidae, which also includes the piculets, wrynecks, and sapsuckers. Members of this family are found worldwide, except for Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, Madagascar, and the extreme polar regions. ...

s and flycatchers inhabit the surrounding pine forests. Terrestrial mammals include the mouse, least chipmunk

The least chipmunk (''Neotamias minimus'') is the smallest species of chipmunk and the most widespread in North America.

Description

It is the smallest species of chipmunk, measuring about in total length with a weight of . The body is gray to ...

, red squirrel, skunk, porcupine, raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the common raccoon to distinguish it from other species, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest of the procyonid family, having a body length of , and a body weight of ...

, beaver, badger

Badgers are short-legged omnivores in the family Mustelidae (which also includes the otters, wolverines, martens, minks, polecats, weasels, and ferrets). Badgers are a polyphyletic rather than a natural taxonomic grouping, being united by ...

, coyote, bighorn sheep

The bighorn sheep (''Ovis canadensis'') is a species of sheep native to North America. It is named for its large horns. A pair of horns might weigh up to ; the sheep typically weigh up to . Recent genetic testing indicates three distinct subspec ...

, bobcat, elk, mule deer

The mule deer (''Odocoileus hemionus'') is a deer indigenous to western North America; it is named for its ears, which are large like those of the mule. Two subspecies of mule deer are grouped into the black-tailed deer.

Unlike the related whi ...

, yellow-bellied marmot, and American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison'') is a species of bison native to North America. Sometimes colloquially referred to as American buffalo or simply Bubalina, buffalo (a different clade of bovine), it is one of two extant species of bison, alongs ...

. The striped chorus frog, western chorus frog, and northern leopard frog

''Lithobates pipiens''Integrated Taxonomic Information System nternet2012''Lithobates pipiens'' pdated 2012 Sept; cited 2012 Dec 26Available from: www.itis.gov/ or ''Rana pipiens'', commonly known as the northern leopard frog, is a species of le ...

also inhabit the area, along with several species of snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

. Grizzly Bear Brook and Starling Basin Brook, the two streams in the memorial, support fish such as the longnose dace

The longnose dace (''Rhinichthys cataractae'') is a freshwater minnow native to North America. ''Rhinicthys'' means snout fish (reference to the long snout) and ''cataractae'' means of the cataract (first taken from Niagara Falls). Longnose dace ...

and the brook trout. Mountain goat

The mountain goat (''Oreamnos americanus''), also known as the Rocky Mountain goat, is a hoofed mammal endemic to mountainous areas of western North America. A subalpine to alpine species, it is a sure-footed climber commonly seen on cliffs an ...

s are not indigenous to the region. Those living near Mount Rushmore are descendants of a tribe that Canada gifted to Custer State Park in 1924, which later escaped.

At lower elevations, coniferous trees, mainly the ponderosa pine

''Pinus ponderosa'', commonly known as the ponderosa pine, bull pine, blackjack pine, western yellow-pine, or filipinus pine is a very large pine tree species of variable habitat native to mountainous regions of western North America. It is the ...

, surround most of the monument, providing shade from the sun. Other trees include the bur oak

''Quercus macrocarpa'', the bur oak or burr oak, is a species of oak tree native to eastern North America. It is in the white oak section, ''Quercus'' sect. ''Quercus'', and is also called mossycup oak, mossycup white oak, blue oak, or scrub o ...

, the Black Hills spruce, and the cottonwood. Nine species of shrubs grow near Mount Rushmore. There is also a wide variety of wildflowers, including especially the snapdragon

''Antirrhinum'' is a genus of plants commonly known as dragon flowers, snapdragons and dog flower because of the flowers' fancied resemblance to the face of a dragon that opens and closes its mouth when laterally squeezed. They are native to r ...

, sunflower, and violet. Towards higher elevations, plant life becomes sparser. However, only approximately five percent of the plant species found in the Black Hills are indigenous to the region.

The area receives about of precipitation on average per year, enough to support abundant animal and plant life. Trees and other plants help to control surface runoff. Dikes, seeps, and springs help to dam up water that is flowing downhill, providing watering spots for animals. In addition, stones like sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

and limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

help to hold groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath Earth's surface in rock and soil pore spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. About 30 percent of all readily available freshwater in the world is groundwater. A unit of rock or an unconsolidated ...

, creating aquifer

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing, permeable rock, rock fractures, or unconsolidated materials ( gravel, sand, or silt). Groundwater from aquifers can be extracted using a water well. Aquifers vary greatly in their characteris ...

s.

A 2016 investigation by the U.S. Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, and ...

found unusually high concentrations of perchlorate

A perchlorate is a chemical compound containing the perchlorate ion, . The majority of perchlorates are commercially produced salts. They are mainly used as oxidizers for pyrotechnic devices and to control static electricity in food packaging. Per ...

in the surface water and groundwater of the area. A sample collected from a stream had a maximum perchlorate concentration of 54 micrograms per liter, roughly 270 times higher than samples taken from locations outside the area. The report concluded the probable cause of the contamination was the aerial fireworks

Fireworks are a class of low explosive pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They are most commonly used in fireworks displays (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), combining a large number of devices ...

displays that had taken place on Independence Days from 1998 to 2009. The National Park Service also reported that at least 27 forest fires around Mount Rushmore in that same period (1998 to 2009) have been caused by fireworks displays.

A study of the fire scars present in tree ring

Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the scientific method of dating tree rings (also called growth rings) to the exact year they were formed. As well as dating them, this can give data for dendroclimatology, the study of climate and atmos ...

samples indicates that forest fires occur in the ponderosa forests surrounding Mount Rushmore around every 27 years. Large fires are not common. Most events have been ground fires that serve to clear forest debris. The area is a climax community

In scientific ecology, climax community or climatic climax community is a historic term for a community of plants, animals, and fungi which, through the process of ecological succession in the development of vegetation in an area over time, hav ...

. Recent pine beetle infestations have threatened the forest.

Geography

Geology

Mount Rushmore is largely composed ofgranite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

. The memorial is carved on the northwest margin of the Black Elk Peak

Black Elk Peak is the highest natural point in the U.S. state of South Dakota and the Midwestern United States. It lies in the Black Elk Wilderness area, in southern Pennington County, in the Black Hills National Forest. The peak lies west-sout ...

granite batholith in the Black Hills of South Dakota, so the geologic formations of the heart of the Black Hills region are also evident at Mount Rushmore. The batholith magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

intruded into the pre-existing mica schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

rocks during the Proterozoic, 1.6 billion years ago.Geologic ActivityNational Park Service. Coarse grained pegmatite

dikes

Dyke (UK) or dike (US) may refer to:

General uses

* Dyke (slang), a slang word meaning "lesbian"

* Dike (geology), a subvertical sheet-like intrusion of magma or sediment

* Dike (mythology), ''Dikē'', the Greek goddess of moral justice

* Dikes ...

are associated with the granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

intrusion of Black Elk Peak and are visibly lighter in color, thus explaining the light-colored streaks on the foreheads of the presidents.

The Black Hills granites were exposed to erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is dis ...

during the Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is prec ...

, but were later buried by sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

and other sediments during the Cambrian. Remaining buried throughout the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

, they were re-exposed again during the Laramide orogeny

The Laramide orogeny was a time period of mountain building in western North America, which started in the Late Cretaceous, 70 to 80 million years ago, and ended 35 to 55 million years ago. The exact duration and ages of beginning and end of the ...

around 70 million years ago. The Black Hills area was uplifted as an elongated geologic dome. Subsequent erosion stripped the granite of the overlying sediments and the softer adjacent schist. Some schist does remain and can be seen as the darker material just below the sculpture of Washington.

The tallest mountain in the region is Black Elk Peak

Black Elk Peak is the highest natural point in the U.S. state of South Dakota and the Midwestern United States. It lies in the Black Elk Wilderness area, in southern Pennington County, in the Black Hills National Forest. The peak lies west-sout ...

(). Borglum selected Mount Rushmore as the site for several reasons. The rock of the mountain is composed of smooth, fine-grained granite. The durable granite erodes only every 10,000 years, thus was more than sturdy enough to support the sculpture and its long-term exposure. The mountain's height of above sea level made it suitable, and because it faces the southeast, the workers also had the advantage of sunlight for most of the day.

It is not possible to add another president to the memorial, because the rock that surrounds the existing faces is not suitable for additional carving, and because if additional sculpting work were done, that might create instabilities in the existing carvings.

Soils

The Mount Rushmore area is underlain by well drained alfisol soils of very gravelly loam (Mocmount) to silt loam (Buska) texture, brown to dark grayish brown.Climate

Mount Rushmore has a dry-winterhumid continental climate

A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900, typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and freezing ...

(''Dwb'' in the Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

). It is inside a USDA Plant Hardiness Zone of 5a, meaning certain plant life in the area can withstand a low temperature of no less than .

The two wettest months of the year are May and June. Orographic lift

Orographic lift occurs when an air mass is forced from a low elevation to a higher elevation as it moves over rising terrain. As the air mass gains altitude it quickly cools down adiabatically, which can raise the relative humidity to 100% and cr ...

causes brief but strong afternoon thunderstorms during the summer.

In popular culture

Mount Rushmore has been depicted in multiple films, comic books, and television series. Its functions vary from settings for action scenes to the site of hidden locations. Its most famous appearance is as the location of the final chase scene in the 1959 film ''

Mount Rushmore has been depicted in multiple films, comic books, and television series. Its functions vary from settings for action scenes to the site of hidden locations. Its most famous appearance is as the location of the final chase scene in the 1959 film ''North by Northwest

''North by Northwest'' is a 1959 American spy thriller film, produced and directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint and James Mason. The screenplay was by Ernest Lehman, who wanted to write "the Hitchcock picture ...

.'' It is used as a secret base of operations by the protagonists in the 2004 film '' Team America: World Police'', and the secret underground city of Cíbola is located there in the 2007 film '' National Treasure: Book of Secrets''. In some films, the presidential faces are replaced with others; examples include the 1980 film ''Superman II

''Superman II'' is a 1980 superhero film directed by Richard Lester and written by Mario Puzo and David and Leslie Newman from a story by Puzo based on the DC Comics character Superman. It is the second installment in the ''Superman'' film se ...

'' and the 1996 film ''Mars Attacks!

''Mars Attacks!'' is a 1996 American science fiction comedy film directed by Tim Burton, who also co-produced it with Larry J. Franco. The screenplay by Jonathan Gems was based on the Topps trading card series of the same name. The film featu ...

'' where the villains add their faces to the monument, and the 2003 film ''Head of State

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

'' where the newly elected president's face is added. In works showing attacks on landmarks to signify the scope of a threat, Mount Rushmore is a common target; examples include the aforementioned facial replacements in ''Superman II'' and ''Mars Attacks!'' as well as natural disasters in works like the 2006 miniseries '' 10.5: Apocalypse'' and terrorist attacks as in the 1997 film ''The Peacekeeper

''The Peacekeeper'' is a 1997 action film directed by Frédéric Forestier, and starring Dolph Lundgren, Michael Sarrazin, Montel Williams, and Roy Scheider. The film follows U.S. Air Force Major Frank Cross, who is the only man who can prevent th ...

''. An atypical representation of the monument appears in the 2013 film ''Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

'', where instead of being treated with reverence it is criticized for being unfinished.Walter Metz,Review: Nebraska. Dir. Alexander Payne. Paramount Vantage, 2013

. ''Middle West Review'' Volume 1, Number 1, (University of Nebraska Press, Fall 2014), p. 154–55.

Controversies

TheTreaty of Fort Laramie (1868)

The Treaty of Fort Laramie (also the Sioux Treaty of 1868) is an agreement between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota and Arapaho Nation, following the failure of the first F ...

had granted the Black Hills to the Lakota people in perpetuity, but the United States took the area from the tribe after the Great Sioux War of 1876. Members of the American Indian Movement

The American Indian Movement (AIM) is a Native American grassroots movement which was founded in Minneapolis, Minnesota in July 1968, initially centered in urban areas in order to address systemic issues of poverty, discrimination, and police br ...

led an occupation of the monument in 1971, naming it "Mount Crazy Horse", and Lakota holy man John Fire Lame Deer

John Fire Lame Deer (in Lakota ''Tȟáȟča Hušté''; March 17, 1903 – December 14, 1976, also known as Lame Deer, John Fire and John (Fire) Lame Deer) was a Lakota holy man, member of the Heyoka society, grandson of the Miniconjou head man L ...

planted a prayer staff on top of the mountain. Lame Deer said that the staff formed a symbolic shroud over the presidents' faces "which shall remain dirty until the treaties concerning the Black Hills are fulfilled."Matthew Glass, "Producing Patriotic Inspiration at Mount Rushmore," ''Journal of the American Academy of Religion'', Vol. 62, No. 2. (Summer, 1994), pp. 265–283.

Construction on the Crazy Horse Memorial began in 1940 elsewhere in the Black Hills. Ostensibly to commemorate the Native American leader and as a response to Mount Rushmore, if completed it would be larger than Mount Rushmore. The Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation has rejected offers of federal funds. Its construction has the support of some Lakota chiefs, but it is the subject of controversy, even among Native American tribes.

The 1980 United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

decision ''United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians

''United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians'', 448 U.S. 371 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that: 1) the enactment by Congress of a law allowing the Sioux Nation to pursue a claim against the United States tha ...

'' ruled that the Sioux had not received just compensation for their land in the Black Hills, which includes Mount Rushmore. The court proposed $102 million as compensation for the loss of the Black Hills. This compensation was valued at $1.3 billion in 2011, and – with accumulated interest – nearly $2 billion in 2021. In 2020, Oglala Lakota Nation

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

citizen and Indigenous activist Nick Tilsen explained that his people would not accept a settlement, "because we won't settle for anything less than the full return of our lands as stipulated by the treaties our nations signed and agreed upon."

In 2004, Gerard Baker was appointed superintendent of the park, the first and so far only Native American in that role. Baker stated that he will open up more "avenues of interpretation", and that the four presidents are "only one avenue and only one focus."

On July 3, 2020, scores of activists demonstrated when President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

held a campaign rally at Mount Rushmore. The foremost message was that Indigenous people want their land back, pursuant to the ongoing dispute of the Black Hills land claim. Twenty people were arrested.

Legacy and commemoration

On August 11, 1952, the U.S. Post Office issued the Mount Rushmore Memorial 3-centcommemorative stamp

A commemorative stamp is a postage stamp, often issued on a significant date such as an anniversary, to honor or commemorate a place, event, person, or object. The ''subject'' of the commemorative stamp is usually spelled out in print, unlike defi ...

on the 25th anniversary of the dedication of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial. On January 2, 1974, a 26-cent airmail stamp depicting the monument was also issued. In 1991 the United States Mint released commemorative silver dollar, half-dollar, and five-dollar coins celebrating the 50th anniversary of the monument's dedication, and the sculpture was the main subject of the 2006 South Dakota state quarter.

In music, American composer Michael Daugherty's 2010 piece for chorus and orchestra, "Mount Rushmore," depicts each of the four presidents in separate movements. The piece sets texts by George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, William Billings

William Billings (October 7, 1746 – September 26, 1800) is regarded as the first American choral composer and leading member of the First New England School.

Life

William Billings was born in Boston, Massachusetts. At the age of 14, t ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, Maria Cosway

Maria Luisa Caterina Cecilia Cosway (ma-RYE-ah; née Hadfield; 11 June 1760 – 5 January 1838) was an Italian-English painter, musician, and educator. She worked in England, in France, and later in Italy, cultivating a large circle of friends a ...

, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

. By contrast, the song, "Little Snakes", by Protest The Hero, "addresses the violent colonial history involved in the sculpting of Mount Rushmore", critiquing the monument as a symbol of colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

, referencing the genocide of indigenous peoples

The genocide of indigenous peoples, colonial genocide, or settler genocide is elimination of entire communities of indigenous peoples as part of colonialism. Genocide of the native population is especially likely in cases of settler colonialis ...

and the ownership of slaves by George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

.

The Washington Nationals

The Washington Nationals are an American professional baseball team based in Washington, D.C.. They compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member of the National League (NL) East division. From 2005 to 2007, the team played in RFK Stadiu ...

baseball club uses large foam rubber

Foam rubber (also known as cellular rubber, sponge rubber, or expanded rubber) refers to rubber that has been manufactured with a foaming agent to create an air-filled matrix structure. Commercial foam rubbers are generally made of synthetic rub ...

depictions of the "Rushmore Four" in both their marketing campaigns and in a series of in-stadium promotions such as the Presidents Race.

See also

* List of colossal sculpture ''in situ'' *List of tallest statues

This list of tallest statues includes completed statues that are at least tall, which was the assumed height of the Colossus of Rhodes. The height values in this list are measured to the highest part of the human (or animal) figure, but exclude ...

* Crazy Horse Memorial, another large sculpture in the Black Hills

* Atatürk Mask, another large relief sculpture

References

Further reading

* * * Coutant, Arnaud (2014).Les Visages de l'Amérique, les constructeurs d'une démocratie fédérale

'. Mare et Martin (). French study about the Four Presidents, Life, presidency, influence about American political evolution. (Archived link) * * * Larner, Jesse (2002). ''Mount Rushmore: An Icon Reconsidered''. New York: Nation Books. * Taliaferro, John (2002). ''Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore''. New York: PublicAffairs. . Puts the creation of the monument into a historical and cultural context. * ''The National Parks: Index 2001–2003''. Washington, D.C.:

United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the ma ...

. .

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mount Rushmore National Memorials of the United States Black Hills Landforms of Pennington County, South Dakota Monuments and memorials in South Dakota National Park Service areas in South Dakota Outdoor sculptures in South Dakota Protected areas of Pennington County, South Dakota Rushmore Buildings and monuments honoring American presidents in the United States Granite sculptures in South Dakota Rock formations of South Dakota Symbols of South Dakota Monuments and memorials to Abraham Lincoln in the United States Monuments and memorials to George Washington in the United States Statues of Abraham Lincoln Statues of George Washington Cultural depictions of Abraham Lincoln Statues of Theodore Roosevelt Cultural depictions of Thomas Jefferson Great Sioux War of 1876 1941 sculptures Mountain monuments and memorials Monuments and memorials on the National Register of Historic Places in South Dakota Sculptures in South Dakota Sculptures by Gutzon Borglum Sculptures of presidents of the United States Colossal statues in the United States Statues of Thomas Jefferson Unfinished sculptures National Register of Historic Places in Pennington County, South Dakota